Introduction

Chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is a

common cause of liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)

(1,2). HCC is the third leading cause of

cancer-related death in Japan, and the annual risk of developing

HCC among HCV-infected patients with compensated cirrhosis is

reportedly 1.8–8.3% (3). The goal of

anti-HCV therapy is to successfully eradicate HCV to resolve liver

disease. Currently, interferon (IFN)-based therapies, usually in

combination with ribavirin (RBV), are commonly used to eradicate

HCV infection, but this combination therapy causes severe adverse

effects, such as hematological toxicity and depression (4–7);

therefore, direct-acting antiviral (DAA) agents are increasingly

used for the treatment of HCV infection (8). To date, the effects of IFN-free DAA

therapy on depressive symptoms has not been well-documented.

Therefore, the aims of the present study were to evaluate the

efficacy and tolerability of various IFN-free treatment regimens in

Japanese patients with HCV genotype-1 infection and to evaluate the

severity of depression symptoms using the Beck Depression

Inventory-II (BDI-II) questionnaire (9,10).

Materials and methods

Patients

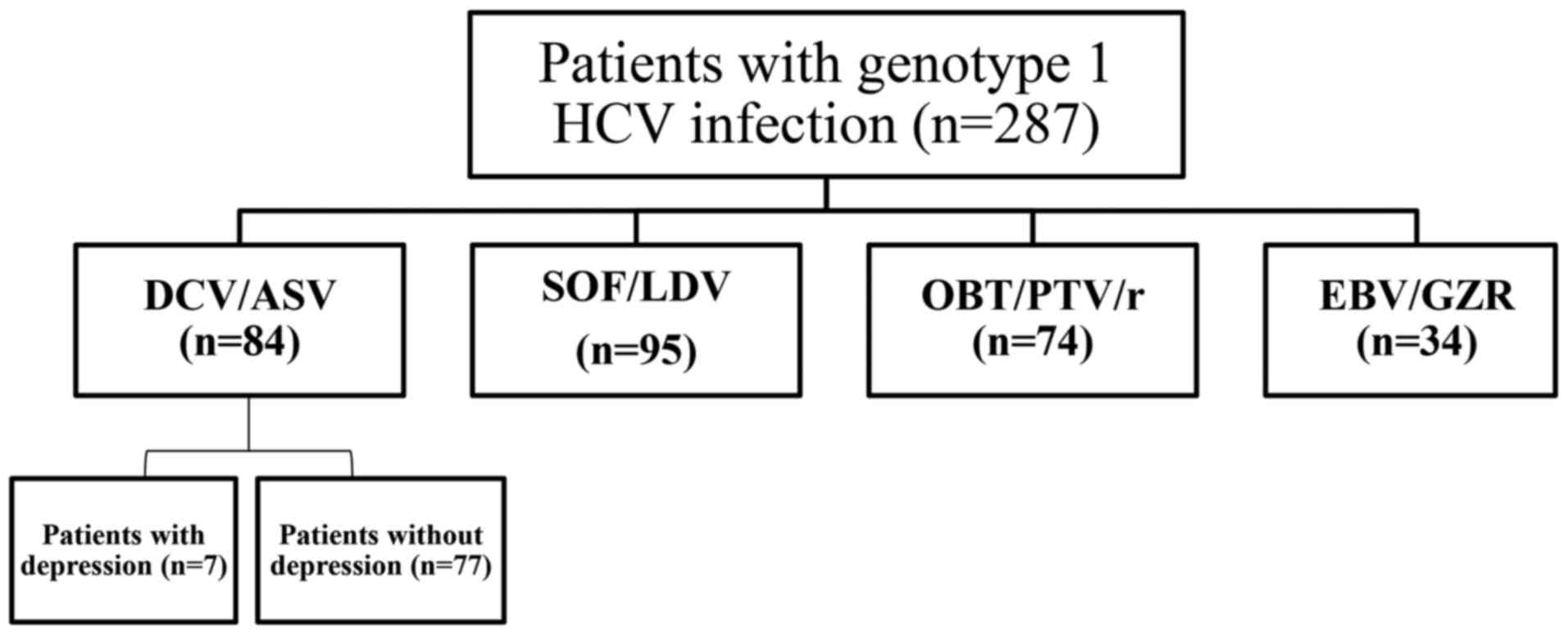

The study cohort consisted of 287 consecutive

patients with HCV genotype-1 infection who were treated at Nara

Medical University Hospital (Kashihara, Japan) from November 2013

to July 2015. The remaining 287 patients included 84 who were

treated for 24 weeks with daclatasvir/asunaprevir (DCV/ASV;

Bristol-Myers Squibb, Princeton, NJ, USA), 95 treated for 12 weeks

with sofosbuvir/ledipasvir (SOF/LDV; Gilead Sciences, Inc., Foster

City, CA, USA), 74 treated for 12 weeks with

ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir (OBV/PTV/r; AbbVie Inc., North

Chicago, IL, USA), and 34 treated for 12 weeks with

elbasvir/grazoprevir (EBV/GZR; MSD, Tokyo, Japan) (Fig. 1). The presence of NS5A

resistance-associated substitutions (RASs), which decrease the

sustained the sustained virological response (SVR) rate (11,12), was

assessed in all patients receiving DAAs prior to the start of

therapy by direct sequencing (13).

Exclusion criteria were coinfection with another virus, pregnancy,

history of clinical hepatic decompensation, or the use of

immunosuppressants. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics

Committee of Nara Medical University Hospital and conducted in

accordance with the tenets of the Tokyo revision of the Declaration

of Helsinki (1975).

BDI-II questionnaire

All patients enrolled in the study also completed

the BDI-II, which is a 21-question, self-reported, screening

instrument used to assess characteristic attitudes and symptoms of

depression. Each item is assigned a score of 0–3, with 3 indicating

the most severe symptoms. A cumulative score is determined by

adding the scores of the individual items. BDI-II scores were

determined using the guidelines set forth in the BDI-II manual

(14,15). In general, a score of <9 indicates

no or minimal depression, that of 10–18 indicates mild-to-moderate

depression, that of 19–29 indicates moderate-to-severe depression,

and that of >30 indicates severe depression. The clustering of

depressive symptoms was further examined using specific, somatic,

and cognitive-affective symptom dimensions described by Beck et

al (16).

Statistical analysis

BDI-II subscale scores were evaluated using one-way

analysis of variance followed by the Bonferroni multiple-comparison

test. Bivariate analyses of nominal parameters were performed using

the chi-squared test. A paired t-test was used to evaluate changes

in body mass index (BMI). Statistical analyses were performed using

GraphPad Prism version 6.04 software (GraphPad Software, Inc., La

Jolla, CA, USA). All tests were two-tailed and a probability

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

Baseline characteristics of patients

treated with IFN-free DAAs

Overall, 287 patients were enrolled in this study

(Table I). The study cohort

comprised 61.0% female patients, 81.5% patients with chronic

hepatitis, 98.3% with HCV genotype 1b, and 38.3% who received

previous IFN therapy, and the mean age was 66.3±23.2 years. NS5A

RASs were identified in 18.4% patients.

| Table I.Baseline characteristics of patients

treated with IFN-free DAA therapies (n=287). |

Table I.

Baseline characteristics of patients

treated with IFN-free DAA therapies (n=287).

| Parameters | Value |

|---|

| Mean age, years

(SD) | 66.3 (23.2) |

| Sex (%) |

|

|

Male | 112 (39.0) |

|

Female | 175 (61.0) |

| Liver disease

(%) |

|

| Chronic

hepatitis | 234 (81.5) |

| Liver

cirrhosis | 53 (18.5) |

| Genotype (%) |

|

| Ia | 5 (1.7) |

| Ib | 282 (98.3) |

| Previous IFN

therapy (%) | 110 (38.3) |

| Y93/L31

resistance-associated variants (%) | 53 (18.4) |

| Mean serum HCV-RNA

level, log10 IU/ml (SD) | 5.6 (2.1) |

| Mean aspartate

transaminase, IU/l (SD) | 40 (17) |

| Mean alanine

aminotransferase, IU/l (SD) | 47 (24) |

| Mean platelet

count, 103/µl (SD) | 16 (6.2) |

| Mean albumin, g/dl

(SD) | 4.1 (1.7) |

| Mean total

bilirubin, mg/dl (SD) | 0.5 (0.1) |

| SSRI use (before

DAA therapy) (%) | 4 (1.4) |

| Antipsychotic use

(before DAA therapy) (%) | 10 (3.5) |

| Benzodiazepine use

(before DAA therapy) (%) | 2 (0.7) |

| Tricyclic or

Tetracyclic antidepressants (before DAA therapy) (%) | 5 (1.7) |

| No medication

(before DAA therapy) (%) | 273 (95.1) |

| SSRI use (after DAA

therapy) (%) | 4 (1.4) |

| Antipsychotic use

(after DAA therapy) (%) | 10 (3.5) |

| Benzodiazepine use

(after DAA therapy) (%) | 2 (0.7) |

| Tricyclic or

Tetracyclic antidepressants (after DAA therapy) (%) | 5 (1.7) |

| No medication

(after DAA therapy) (%) | 273 (95.1) |

The baseline characteristics of seven patients with

depression who received the 24-week DCV/ASV treatment regimen are

summarized in Table II. Among the

seven patients, six (85.7%) had chronic hepatitis, six (85.7%) had

HCV genotype 1b, none had RASs, and six (85.7%) were female.

| Table II.Baseline characteristics of

depressive patients with DCV/ASV therapy (n=7). |

Table II.

Baseline characteristics of

depressive patients with DCV/ASV therapy (n=7).

| Parameters | Value |

|---|

| Mean age, years

(SD) | 59.1 (23.2) |

| Sex (%) |

|

|

Male | 1 (14.3) |

|

Female | 6 (85.7) |

| Liver disease

(%) |

|

| Chronic

hepatitis | 6 (85.7) |

| Liver

cirrhosis | 1 (14.3) |

| Genotype (%) |

|

| Ib | 6 (85.7) |

| I | 1 (14.3) |

| Previous IFN

therapy (%) | 3 (42.9) |

| Y93/L31

resistance-associated variants (%) | 0 (0) |

| Mean serum HCV-RNA

level, log10 IU/ml (SD) | 5.7 (0.6) |

| Mean aspartate

transaminase, IU/l (SD) | 38.0 (21.0) |

| Mean alanine

aminotransferase, IU/l (SD) | 32.6 (29.2) |

| Mean platelet

count, 103/µl (SD) | 19.2 (5.1) |

| Mean albumin, g/dl

(SD) | 4.0 (1.8) |

| Mean total

bilirubin, mg/dl (SD) | 0.3 (0.2) |

| SSRI use (%) | 1 (14.3) |

| Antipsychotic use

(%) | 5 (71.4) |

| Benzodiazepine use

(%) | 1 (14.3) |

| Tricyclic or

Tetracyclic antidepressants (%) | 2 (28.6) |

| No medication

(%) | 2 (28.6) |

Baseline characteristics of patients

treated with IFN-free DAAs

Eighty four Japanese patients received 24 weeks of

DCV/ASV (SVR, 97%), 95 received 12 weeks of SOF/LDV, 74 received 12

weeks of OBT/PTV/r, and 34 received 12 weeks of EBV/GZR (Table III). Patients aged ≥65 years were

more often treated with EBV/GZR (85.2%, 29/34) than DCV/ASV (52.4%,

44/84), SOF/LDV (69.5%, 66/95), or OBT/PTV/r (62.2%, 46/74)

(P<0.01). Patients with cirrhosis were more commonly treated

with DCV/ASV [29.8% (25/84)] than SOF/LDV (18.9%. 18/95), OBT/PTV/r

(10.8%, 7/74), or EBV/GZR (8.8%, 3/34) (P<0.01). The NS5A

resistance-associated variant Y93H was not detected at baseline in

any patient treated with OBV/PTV/r. Patients with NS5A resistance

were more commonly treated with DCV/ASV (3.5%, 3/84) than SOF/LDV

(40.0%, 38/95) or EBV/GZR (35.3%, 12/34) (P<0.01). Patients who

received IFN-based therapy were more commonly treated with DCV/ASV

(61.9%, 52/84) than SOF/LDV (40.0%, 38/95), OBT/PTV/r (27.2%,

20/74), or EBV/GZR (35.3%, 12/34) (P<0.01). Among the four

treatment groups, the percentage of non-responders to IFN was

greatest among patients treated with ASV/DCV (P<0.01). Patients

with impaired renal function were more commonly treated with

EBV/GZR (23.5%, 8/34) than OBT/PTV/r (11%, 9/74), SOF/LDV (0%, 0),

or DCV/ASV (0%, 0) (P<0.01). There were no statistical

differences between the depression rates between the four

groups.

| Table III.Baseline demographics and disease

characteristics of the patients with HCV infection. |

Table III.

Baseline demographics and disease

characteristics of the patients with HCV infection.

| Characteristic | DCV/ASV (n=84) | SOF/LDV (n=95) | OBT/PTV/r

(n=74) | EBV/GZR (n=34) | P-value |

|---|

| Age (years) | 64±15.3 | 68±10.5 | 67±24.9 | 71±8.6 | n.s |

| Age ≥65 years | 44 (52.4) | 66 (69.5) | 46 (62.2) | 29 (85.2) | P<0.01 |

| Male | 42 (50.0) | 35 (36.8) | 21 (32.3) | 14 (41.2) | P<0.05 |

| Cirrhosis | 25 (29.8) | 18 (18.9) | 7 (10.8) | 3 (8.8) | P<0.01 |

| Genotype 1b | 79 (94.0) | 85 (89.5) | 63 (96.9) | 30 (88.2) | n.s |

| HCV-RNA

(log10 IU/ml) | 5.6±0.9 | 5.9±0.7 | 5.9±0.6 | 5.2±0.5 | n.s |

|

Resistance-associated variants | 3 (3.5) | 38 (40.0) | 0 (0.0) | 12 (35.3) | P<0.01 |

| Prior IFN-based

therapy | 52 (61.9) | 38 (40.0) | 20 (27.2) | 12 (35.3) | P<0.01 |

| Intolerable | 5 (9.6) | 8 (21.1) | 4 (20.0) | 4 (33.3) | n.s |

|

Breakthrough/relapse | 12 (23.1) | 18 (47.3) | 8 (40.0) | 4 (33.3) | n.s |

| Non-response | 35 (67.3) | 12 (31.6) | 8 (40.0) | 6 (50.0) | P<0.01 |

| eGFR >30

ml/min/1.73 m2 or hemodialysis | 0 | 0 | 9 (11.0) | 8 (23.5) | P<0.01 |

| Depression | 7 (8.3) | 5 (5.2) | 5 (6.8) | 2 (5.9) | n.s |

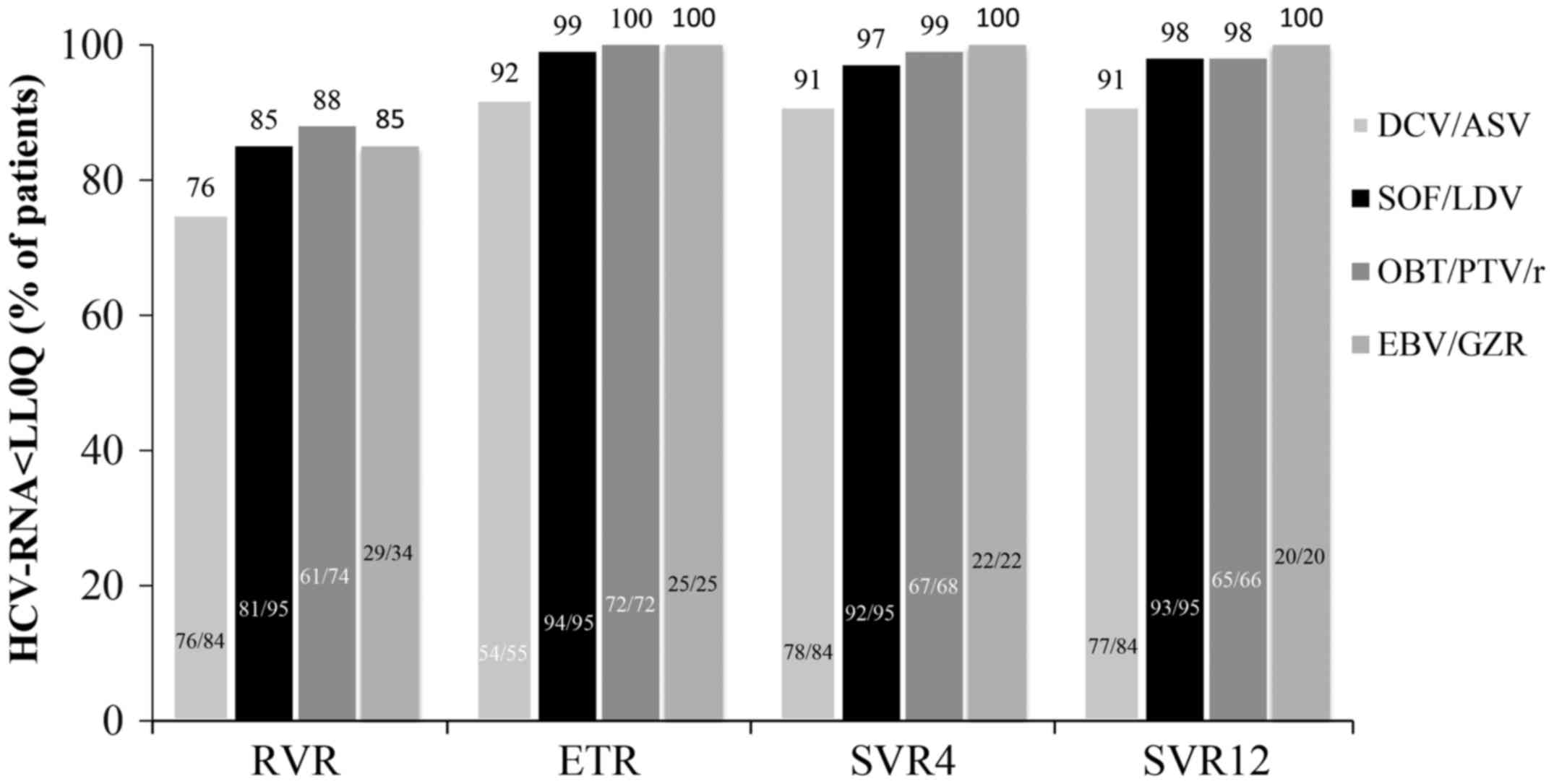

Viral suppression after initiation of

IFN-free therapy, end of treatment response, and SVR

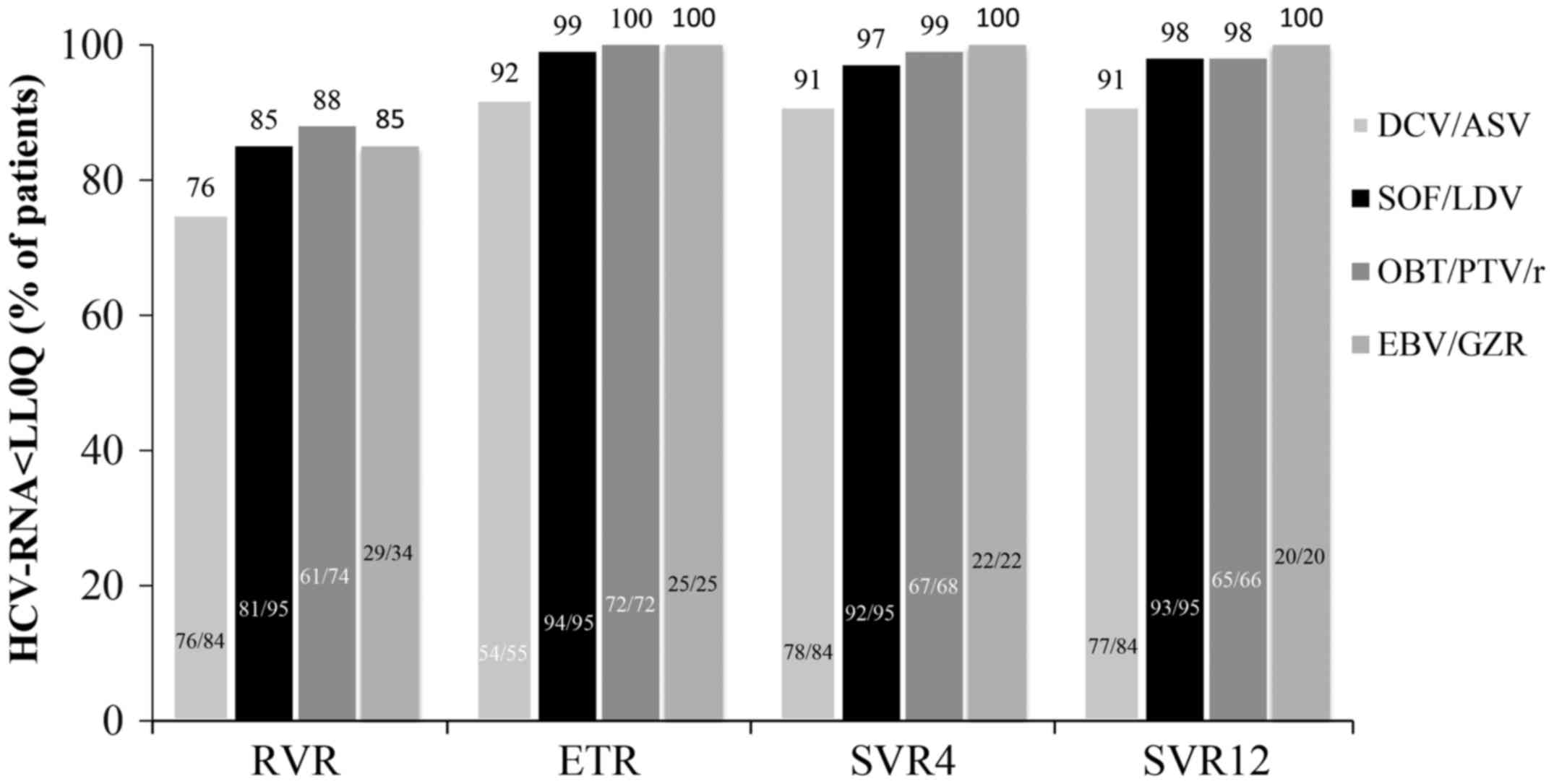

Fig. 2 shows the

percentages of patients in the four groups who achieved viral

suppression based on the duration after the start of therapy, while

treatment was still ongoing, at week 4 (rapid virological response,

RVR), at week 12 (end of treatment, ETR), and at 4 and 12 weeks

after the end of treatment (SVR4 and SVR12). The RVR, ETR, SVR4,

and SVR12 rates were 76% (64/84), 92% (54/55), 93% (78/84), and 92%

(77/84), respectively, in patients treated with DCV/ASV; 85%

(81/95), 99% (94/95), 97% (92/95), and 98% (93/95) for those

treated with SOF/LDV; 88% (65/74), 100% (72/72), 99% (67/68), and

98% (65/66) for those treated with OBV/PTV/r; and 85% (29/34), 100%

(25/25), 100% (22/22), and 100% (20/20) for those treated with

EBV/GZR. No significant differences were observed in the RVR, ETR,

SVR4, and, SVR12 rates among the four groups.

| Figure 2.The proportion of HCV-infected

patients exhibiting viral suppression in response to DAA treatment.

Therapies consisted of DCV/ASV, SOF/LDV, OBV/PTV/r, and EBV/GZR.

The cumulative proportions of patients in the four different groups

who achieved viral suppression at 4 weeks after the start of

treatment, during treatment ongoing, at the ETR, and at 4 and 12

weeks after the end of treatment (SVR4 and SVR12) were shown.

Patient numbers are also shown in the bar graph. No significant

differences were observed in the RVR, ETR, SVR4, and SVR12 rates

among the four groups. ETR, end of treatment; HCV, hepatitis C

virus; DCV/ASV, daclatasvir/asunaprevir; SOF/LDV,

sofosbuvir/ledipasvir; OBT/PTV/r,

ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir; EBV/GZR, elbasvir/grazoprevir;

RVR, rapid virological response; SVR, sustained virological

response. |

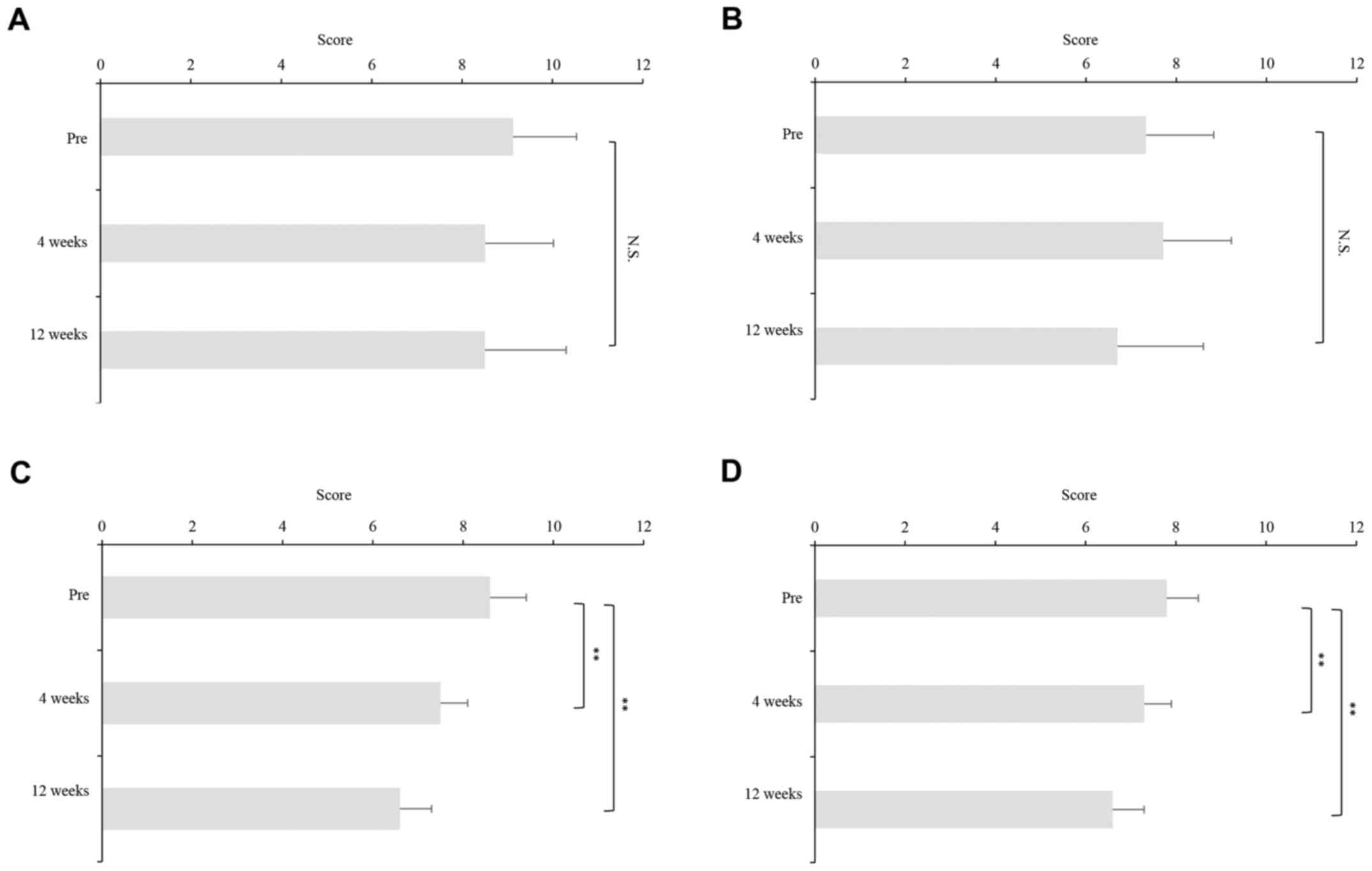

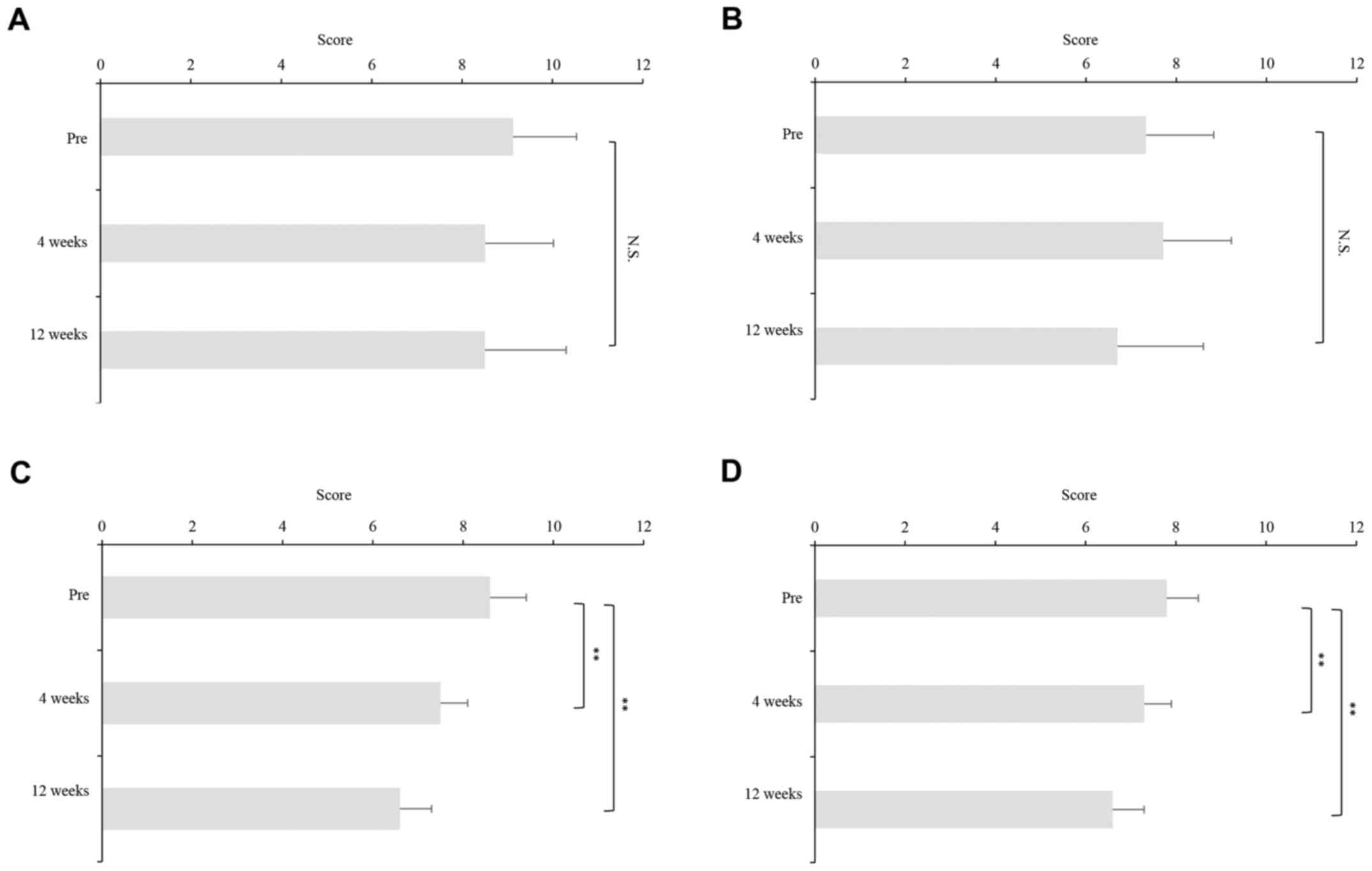

Change in depressive symptoms in

patients treated with IFN-free DAA therapies

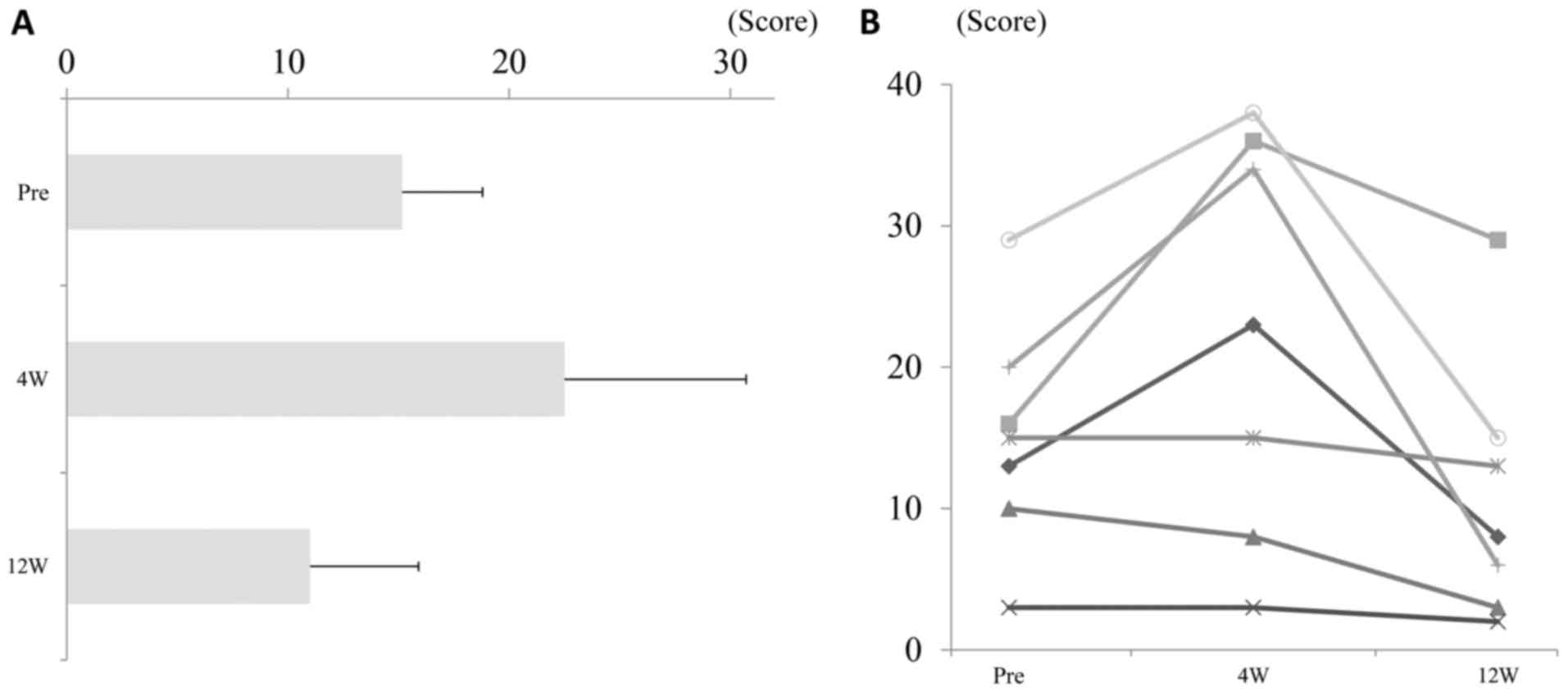

In seven patients with depression who received a

24-week DCV/ASV treatment regimen, the BDI-II scores had increased

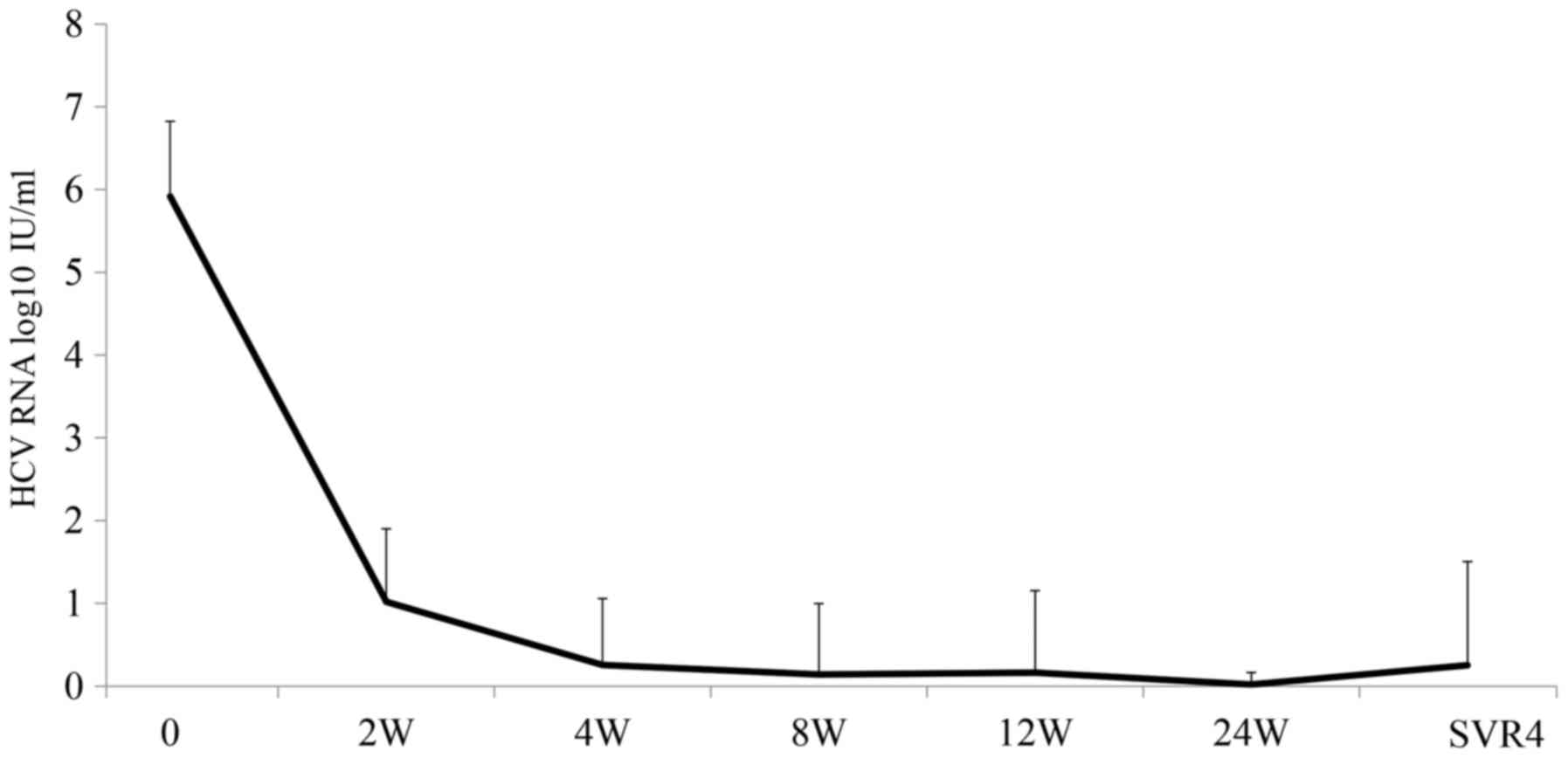

at week 4, as compared to baseline and at week 12 (Fig. 3) in spite of the rapid decline of

serum HCV levels after intiation of DCV/ASV therapy (Fig. 4). The patients treated with DCV/ASV,

OBT/PTV/r, SOF/LDV, and EBR/GZR were divided according to their

median BDI-II scores at baseline into BDI-II relatively high group

and BDI-II relatively low group to examine the effects of DAA

therapies on BDI-II scores (Fig. 5).

The BDI-II scores had decreased, but not significantly, at weeks 4

and 12, as compared to pretreatment values among patients treated

with DCV/ASV in both BDI-II relatively high and low groups

(Fig. 5A and B). BDI-II scores

declined significantly from baseline to week 12 among patients

treated with SOF/LDV and EBR/GZR in both BDI-II relatively high and

low groups and OBT/PTV/r in BDI-II relatively high group (Fig. 5C-G). However, BDI-II scores had

decreased significantly from baseline to week 4, but not week 12,

in BDI-II relatively low group (Fig.

5H).

| Figure 5.Change in BDI-II scores during DAA

therapies. The patients treated with DCV/ASV, OBT/PTV/r, SOF/LDV,

and EBR/GZR were divided according to their median BDI-II scores at

baseline into BDI-II relatively high group and BDI-II relatively

low group to examine the effects of DAA therapies on BDI-II scores.

The BDI-II scores had decreased, but not significantly, at weeks 4

and 12 as compared to pretreatment values among patients treated

with DCV/ASV in both BDI-II relatively (A) high and (B) low groups.

BDI-II scores declined significantly from baseline to week 12 among

patients treated with SOF/LDV in both BDI-II relatively (C) high

and (D) low groups, EBR/GZR in BDI-II (E) high and (F) groups, and

(G) OBT/PTV/r in BDI-II relatively high group. (H) However, BDI-II

scores had decreased significantly from baseline to week 4, but not

week 12, in BDI-II relatively low group. Asterisks indicate

statistically significant differences between indicated

experimental groups. (*P<0.05, **P<0.01) N.S, not

significant; DAA, direct acting antiviral; DCV/ASV,

daclatasvir/asunaprevir; SOF/LDV, sofosbuvir/ledipasvir; OBT/PTV/r,

ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir; EBV/GZR, elbasvir/grazoprevir;

BDI, Beck Depression Inventory. |

Change in psychotropic medication use

in patients treated with IFN-free DAAs

Among the seven patients with depression treated

with DCV/ASV, one (14.3%) received selective serotonin reuptake

inhibitors (SSRI), five (71.4%) received antipsychotic medication,

one (14.3%) received benzodiazepine, two (28.6%) received tricyclic

or tetracyclic antidepressants, and two (28.6%) received no

treatment (Table II). There was no

difference in psychotropic medication use before and after DAA

therapy (Table I).

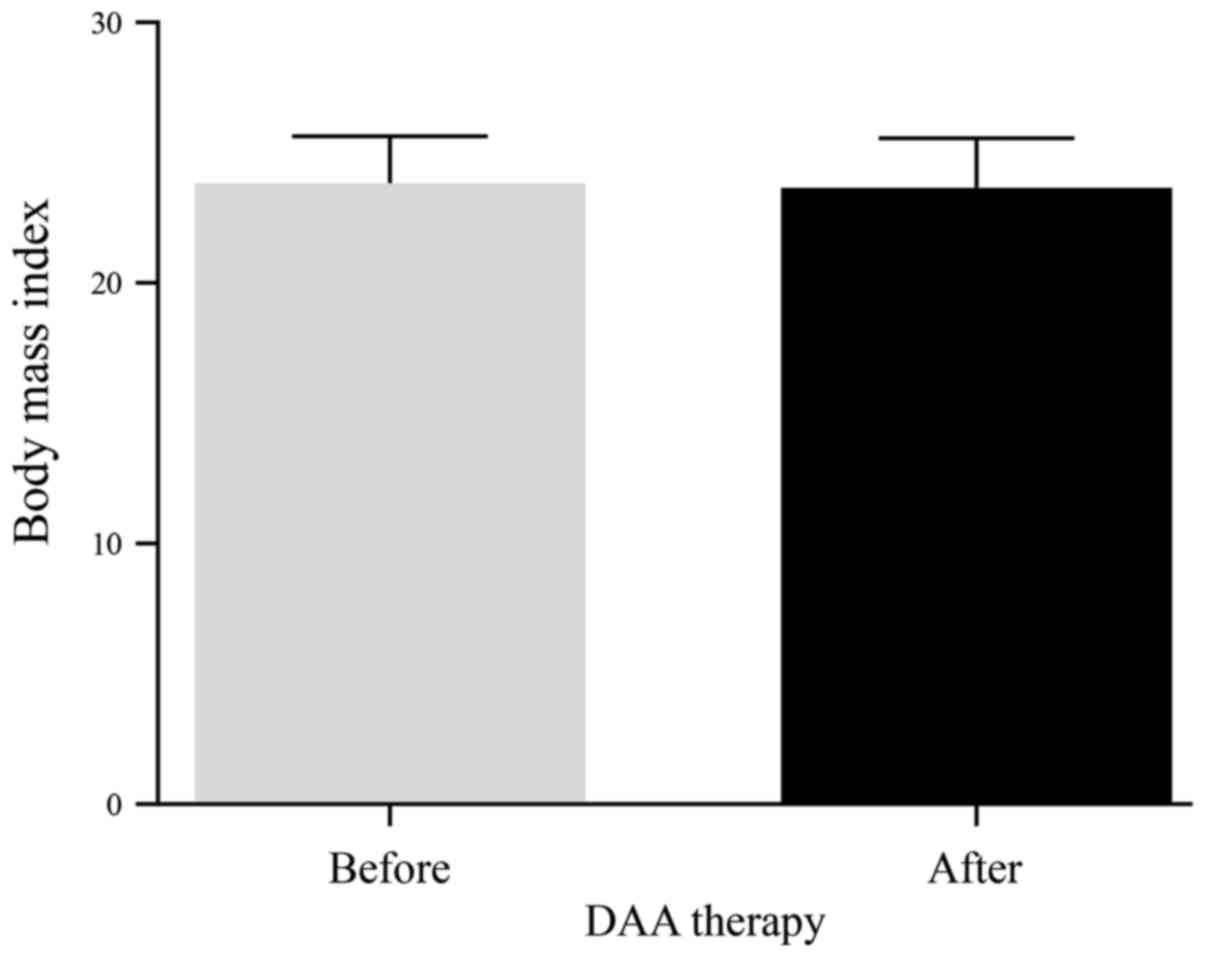

Change in BMI in patients treated with

IFN-free DAAs

There was no significant change in the BMI in

patients after DAA therapy (Fig.

6).

Discussion

The results of the present study clearly show that

various 12-week IFN-free treatment regimens were highly effective

and tolerable in patients with HCV genotype-1 infection. The

percentages of patients aged ≥65 years with cirrhosis who received

IFN-based therapy and non-responders to IFN-based therapy were

highest in those who received 24 weeks of DCV/ASV, probably because

DCV/ASV is the first IFN-free regimen for the treatment of HCV

infection. Chronic HCV infection has a profound negative impact on

mental health disorders, including depression (17–20). To

the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to evaluate the

effects of different IFN-free DAA regimens on the psychometric

properties of the BDI-II in Japanese patients with HCV genotype-1

infection. In the present study, the BDI-II scores decreased from

baseline to the end of the 12-week DAA therapies. Younossi et

al (5,7,21–23) have

reported that 12 weeks of SOF/LDV therapy improve the

health-related quality of life during treatment. Consistent with

the findings of the present study, the use of SOF/LDV regimen has

been reportedly associated with improved BDI-II scores both during

and after treatment (24). In

contrast, in the present study, patients with depression treated

with DCV/ASV for 24 weeks had higher BDI-II scores at week 4, but

lower scores at week 12 than at pretreatment in spite of the rapid

decline of serum HCV levels. Ichikawa et al (25) demonstrated that 24-week DAA treatment

eliminated HCV-RNA and improved psychologic distress. Furthermore,

the results of a recent study demonstrated that 24-week DAA

treatment with DCV plus ASV did not affect mental component scores

at either 12 or 24 weeks after treatment initiation (26). The discrepancy in tolerability of

24-week DAA treatment may be explained in part by the fact that

clinical profiles of patients differ between studies. The 24-week

DAA treatment would have temporary negative effects by leading to

the development of anxiety over a long term therapy but would have

also provided positive effects in the long term by yielding

clinical benefits following HCV eradication. These findings

reinforce the notion that the 12-week regimen was effective and

safe for patients with HCV genotype-1 infection, including those

with depression. Nevertheless, there were several limitations to

this study, including the small number of depressed patients with

HCV infection and the relatively short follow-up period, which

prevented evaluation of the effect on post treatment BDI-II

scores.

Collectively, all four DAA regimens achieved similar

high efficacy in Japanese patients with HCV genotype-1 infection.

The 24-week DAA treatment had temporary negative impact on the

mental health in patients with HCV infection. The BDI-II scores had

significantly decreased following a 12-week regimen of SOF/LDV or

EBR/GZR. Meanwhile, the tolerability was superior with the 12-week

DAA regimes and allowed more patients to reach SVR sooner and with

fewer side effects.

Acknowledegements

The authors acknowledge the support of AbbVie GK and

Bristol-Myers Squibb Company (New York City, NY, USA) for the

support of sequencing analysis of NS5A from patients with HCV

genotype 1b.

Funding

No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

Raw data were generated at Nara Medical University

Hospital. Derived data supporting the findings of the present study

are available from the corresponding author on request.

Authors' contributions

KT, RN, KM, TA, MK, HK, NS, KKa, HT, YS, KS, YF, YT,

SSat, SSai, KN, MF, KKi, TK, TO, DK, AM, TM, YO and JY performed

data analysis. All statistical analyses in this current study were

supervised by TM. HY and TN made substantial contributions to

conception and design and analysis and interpretation of data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Written informed consent for the use of resected

tissue was obtained from all patients and the study protocol was

approved by the Ethics Committee of Nara Medical University.

Patient consent for publication

All study participants or their legal guardians

provided written informed consent prior to study enrollment.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of

interest.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

HCV

|

hepatitis C virus

|

|

HCC

|

hepatocellular carcinoma

|

|

IFN

|

interferon

|

|

DAAs

|

direct-acting antivirals

|

|

DCV/ASV

|

daclatasvir/asunaprevir

|

|

SOF/LDV

|

sofosbuvir/ledipasvir

|

|

OBV/PTV/r

|

ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir

|

|

EBR/GZR

|

elbasvir/grazoprevir

|

|

BDI-II

|

Beck Depression Inventory-II

|

|

RBV

|

ribavirin

|

|

RVR

|

rapid virological response

|

|

ETR

|

end of treatment

|

|

SVR

|

sustained virologic response

|

References

|

1

|

Toshikuni N, Arisawa T and Tsutsumi M:

Hepatitis C-related liver cirrhosis-strategies for the prevention

of hepatic decompensation, hepatocarcinogenesis and mortality.

World J Gastroenterol. 20:2876–2887. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Sievert W, Altraif I, Razavi HA, Abdo A,

Ahmed EA, Alomair A, Amarapurkar D, Chen CH, Dou X, El Khayat H, et

al: A systematic review of hepatitis C virus epidemiology in Asia,

Australia and Egypt. Liver Int. 31 Suppl 2:S61–S80. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Alazawi W, Cunningham M, Dearden J and

Foster GR: Systematic review: Outcome of compensated cirrhosis due

to chronic hepatitis C infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther.

32:344–355. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Younossi Z and Henry L: Systematic review:

Patient-reported outcomes in chronic hepatitis C-the impact of

liver disease and new treatment regimens. Aliment Pharmacol Ther.

41:497–520. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Henry L, Nader F

and Hunt S: An in-depth analysis of patient-reported outcomes in

patients with chronic hepatitis c treated with different anti-viral

regimens. Am J Gastroenterol. 111:808–816. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Nader F, Lam B

and Hunt S: The patient's journey with chronic hepatitis C from

interferon plus ribavirin to interferon- and ribavirin-free

regimens: A study of health-related quality of life. Aliment

Pharmacol Ther. 42:286–295. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Younossi Z, Stepanova M, Omata M, Mizokami

M, Walters M and Hunt S: Health utilities using SF-6D scores in

Japanese patients with chronic hepatitis C treated with

sofosbuvir-based regimens in clinical trials. Health Qual Life

Outcomes. 15:252017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Spengler U: Direct antiviral agents

(DAAs)-A new age in the treatment of hepatitis C virus infection.

Pharmacol Ther. 183:118–126. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Patterson AL, Morasco BJ, Fuller BE,

Indest DW, Loftis JM and Hauser P: Screening for depression in

patients with hepatitis C using the Beck Depression Inventory-II:

Do somatic symptoms compromise validity? Gen Hosp Psychiatry.

33:354–362. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Huang SL, Hsieh CL, Wu RM and Lu WS:

Test-retest reliability and minimal detectable change of the Beck

Depression Inventory and the Taiwan geriatric depression scale in

patients with parkinson's disease. PLoS One. 12:e01848232017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Pawlotsky JM: Hepatitis C virus resistance

to direct-acting antiviral drugs in interferon-free regimens.

Gastroenterology. 151:70–86. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Zeuzem S, Mizokami M, Pianko S, Mangia A,

Han KH, Martin R, Svarovskaia E, Dvory-Sobol H, Doehle B, Hedskog

C, et al: NS5A resistance-associated substitutions in patients with

genotype 1 hepatitis C virus: Prevalence and effect on treatment

outcome. J Hepatol. 66:910–918. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Uchida Y, Kouyama J, Naiki K and Mochida

S: A novel simple assay system to quantify the percent HCV-RNA

levels of NS5A Y93H mutant strains and Y93 wild-type strains

relative to the total HCV-RNA levels to determine the indication

for antiviral therapy with NS5A inhibitors. PLoS One.

9:e1126472014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Steer RA, Ball R, Ranieri WF and Beck AT:

Dimensions of the Beck Depression Inventory-II in clinically

depressed outpatients. J Clin Psychol. 55:117–128. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Hayden MJ, Dixon JB, Dixon ME and O'Brien

PE: Confirmatory factor analysis of the Beck Depression Inventory

in obese individuals seeking surgery. Obes Surg. 20:432–439. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J and

Erbaugh J: An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen

Psychiatry. 4:561–571. 1961. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Dbouk N, Arguedas MR and Sheikh A:

Assessment of the PHQ-9 as a screening tool for depression in

patients with chronic hepatitis C. Dig Dis Sci. 53:1100–1106. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Armstrong AR, Herrmann SE, Chassany O,

Lalanne C, Da Silva MH, Galano E, Carrieri PM, Estellon V, Sogni P

and Duracinsky M: The International development of PROQOL-HCV: An

instrument to assess the health-related quality of life of patients

treated for Hepatitis C virus. BMC Infect Dis. 16:4432016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Younossi Z, Park H, Henry L, Adeyemi A and

Stepanova M: Extrahepatic manifestations of hepatitis C: A

meta-analysis of prevalence, quality of life and economic burden.

Gastroenterology. 150:1599–1608. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Sockalingam S, Blank D, Banga CA, Mason K,

Dodd Z and Powis J: A novel program for treating patients with

trimorbidity: Hepatitis C, serious mental illness and active

substance use. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 25:1377–1384. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Afdhal N,

Kowdley KV, Zeuzem S, Henry L, Hunt SL and Marcellin P: Improvement

of health-related quality of life and work productivity in chronic

hepatitis C patients with early and advanced fibrosis treated with

ledipasvir and sofosbuvir. J Hepatol. 63:337–345. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Omata M,

Mizokami M, Walters M and Hunt S: Quality of life of Japanese

patients with chronic hepatitis C treated with ledipasvir and

sofosbuvir. Medicine (Baltimore). 95:e42432016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Chan HL, Lee MH,

Yu Ml, Dan YY, Choi MS and Henry L: Patient-reported outcomes in

asian patients with chronic hepatitis C treated with ledipasvir and

sofosbuvir. Medicine (Baltimore). 95:e27022016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Tang LS, Masur J, Sims Z, Nelson A,

Osinusi A, Kohli A, Kattakuzhy S, Polis M and Kottilil S: Safe and

effective sofosbuvir-based therapy in patients with mental health

disease on hepatitis C virus treatment. World J Hepatol.

8:1318–1326. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Ichikawa T, Miyaaki H, Miuma S, Taura N,

Motoyoshi Y, Akahoshi H, Nakamura S, Nakamura J, Takahashi Y, Honda

T, et al: Hepatitis C virus-related symptoms, but not quality of

life, were improved by treatment with direct-acting antivirals.

Hepatol Res. 48:E232–E239. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Kawakubo M, Eguchi Y, Okada M, Iwane S,

Oeda S, Otsuka T, Nakashita S, Araki N and Koga A: Chronic

hepatitis c treatment with daclatasvir plus asunaprevir does not

lead to a decreased quality of life. Intern Med. 2018.doi:

10.2169/internalmedicine.0091-17. View Article : Google Scholar

|