Introduction

The aging of the Japanese population is currently

unprecedented (1). The percentage of

the population aged 65 years or older in 2017 was 27.3% according

to a report from the Japanese cabinet (2). The incidence of sarcoma increases

progressively with age (3), and the

number of sarcoma patients in Japan increases yearly according to

the Japanese Registry of Musculoskeletal Oncology (4).

At present, there are no established treatments for

elderly sarcoma patients, who are difficult to treat in the same

manner as their young counterparts because of potential

immunodeficiencies, underlying diseases, complications, and social

backgrounds. Moreover, studies addressing the management of elderly

sarcoma patients are few (4–10), with controversial results. Here we

present a retrospective study aimed at determining the best

treatment strategy for elderly sarcoma patients.

Materials and methods

Patients and treatments

The present retrospective study comprised 34

patients (21 men and 13 women) with malignant bone or soft tissue

tumors who underwent surgery in our department from September 2004

to March 2014 (Table I). The median

patient age was 72 years (range, 65–86 years); 11 patients were

65–69 years-old, 10 were 70–74 years-old, and 13 were ≥75

years-old. All patients provided written informed consent for this

retrospective study.

| Table I.Characteristics of the study

population. |

Table I.

Characteristics of the study

population.

| Factor | Patients, n (%) |

|---|

| Age (years) |

|

|

65–69 | 11 (32) |

|

70–74 | 7 (20) |

| ≥75 | 16 (48) |

| Sex |

|

| Male | 21 (62) |

|

Female | 13 (38) |

| Tumor site |

|

| Arms | 3 (9) |

| Legs | 28 (82) |

|

Trunk | 3 (9) |

| Tumor size (cm) |

|

|

<5 | 3 (9) |

| 5–10 | 12 (35) |

|

>10 | 19 (56) |

| Histological

type |

|

| Soft

tissue |

|

|

Liposarcoma | 19 (56) |

|

Atypical

lipomatous tumor/well differentiated | 3 (9) |

|

Dedifferentiated | 4 (12) |

|

Myxoid | 2 (6) |

|

Pleomorphic | 10 (29) |

|

Leiomyosarcoma | 9 (26) |

|

Undifferentiated

pleomorphic sarcoma | 3 (9) |

|

Synovial

sarcoma | 1 (3) |

| Bone |

|

|

Chondrosarcoma | 2 (6) |

| Histological

grade |

|

|

Total |

|

|

Low | 11 (32) |

|

High | 23 (68) |

| Bone

tumor |

|

|

Grade 1 | 0 (0) |

|

Grade 2 | 1 (3) |

|

Grade 3 | 1 (3) |

| Soft

tissue (FNCLCC grading system) |

|

|

Grade 1 | 11 (32) |

|

Grade 2 | 3 (9) |

|

Grade 3 | 18 (53) |

| Complications |

|

|

Diabetes mellitus | 5 |

|

Hypertension | 15 |

|

Dementia | 2 |

|

Hepatitis | 1 |

| Metastasis at

initial visit |

|

|

(−) | 31 |

|

(+) | 3 |

| Surgical

margin |

|

| R0 | 25 (74) |

| R1 | 7 (20) |

| R2 | 2 (6) |

|

Adequate | 25 (74) |

|

Inadequate | 7 (20) |

|

Intralegional | 2 (6) |

| Surgical time

(min) |

|

|

<60 | 4 (12) |

|

60–120 | 19 (56) |

|

>120 | 11 (32) |

| Blood loss

(cc) |

|

|

<100 | 20 (59) |

|

100–200 | 6 (17) |

|

>200–300 | 5 (15) |

|

>300–400 | 3 (9) |

|

>400 | 3 (9) |

| Adjuvant

radiotherapy | 30 (88) |

|

(−) | 4 (12) |

|

(+) |

|

| Adjuvant

chemotherapy |

|

|

(−) | 31 (91) |

|

(+) | 3 (9) |

| Follow-up period

(years) |

|

|

<5 | 11 (32) |

| ≥5 | 23 (68) |

| Oncological

result |

|

|

CDF | 24 (71) |

|

AWD | 3 (9) |

|

DOD | 7 (20) |

| Recurrence |

|

|

(−) | 20 (59) |

|

(+) | 10 (41) |

| ECOG-PS |

|

| 0 | 9 (26) |

| 1 | 21 (62) |

| 2 | 4 (12) |

| 3 | 0 (0) |

| 4 | 0 (0) |

| ASA-PS |

|

| I | 9 (26) |

| II | 23 (74) |

|

III | 0 (0) |

| IV | 0 (0) |

| V | 0 (0) |

| VI | 0 (0) |

The tumor sites were the legs (28 cases), arms (3

cases), and trunk (3 cases) (Table

I). The histological tumor types were liposarcoma (19 cases),

leiomyosarcoma (9 cases), undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma (3

cases), chondrosarcoma (2 cases), and synovial sarcoma (1 case).

Among the 19 liposarcoma cases, 3 were well differentiated, 4 were

dedifferentiated, 2 were myxoid, and 10 were pleomorphic (11).

The classification systems of the French Federation

of Comprehensive Cancer Centers (12) and Lee et al (13) were used for histological grading of

soft tissue and bone sarcomas, respectively. Twenty-three sarcomas

were categorized as high-grade and 11 as low-grade (Table I). Eleven soft tumor sarcomas were

grade 1; 3 were grade 2; and 18 were grade 3. One chondrosarcoma

was grade 2 and the other was grade 3. The complications were

diabetes mellitus (5 cases), hypertension (15 cases), dementia (2

cases), and hepatitis (1 case). Three patients had metastatic

lesions at their first visit.

Treatments included surgery with adequate margins

(25 cases), surgery with inadequate margins and radiotherapy (4

cases), surgery with inadequate margins and chemotherapy (3 cases),

and intralesional resection (2 cases). The postoperative

observation period ranged from 7 to 112 months (average, 49

months).

Surgery aimed to obtain adequate surgical margins in

all cases. Using previously described methods, surgical margins

were classified as adequate, inadequate, or intralesional (14) and R0, R1, or R2 (15). R1 and R2 margins are those in which

residual tumor is detectable microscopically and macroscopically,

respectively. R0 margins are tumor-free (15). The margins were inadequate in cases

where the tumors were intensive. These tumors were treated via

marginal resection because aggressive surgery may have impaired

performance status. Twenty-five (74%) cases were R0, 7 (20%) were

R1, and 2 (6%) were R2 (Table I).

The mean surgical time was 114.7 min (range, 50–465 min), with 23

(68%) surgeries requiring <120 min. The mean amount of blood

loss was 160.7 cc (range, 10–1501 cc); most patients (31, 91%) lost

<300 cc.

The indication for radiotherapy was a high risk of

recurrence after surgery with inadequate margins. Two patients with

dedifferentiated liposarcoma, 1 patient with leiomyosarcoma, and 1

patient with pleomorphic liposarcoma received postoperative

radiotherapy. A total dose of 60 Gy (2 Gy/day, 5 days/week) was

applied to the operative field.

Systemic chemotherapy was administered to patients

<70 years-old with preoperative metastasis or a locally

intensive tumor [Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance

Status (ECOG-PS) score, 0–1]. Three patients with chondrosarcoma,

synovial sarcoma, and dedifferentiated liposarcoma, respectively,

received chemotherapy. In accordance with the Neoadjuvant

Chemotherapy for Osteosarcoma protocol in Japan (95 J, 80% dose)

(16), the preoperative regimen for

chondrosarcoma consisted of 8 g/m2 high-dose

methotrexate, 80 mg/m2 cisplatin, and 48

mg/m2 adriamycin; the postoperative regimen, which was

administered to 1 patient owing to a poor response, was the same

with the addition of 14 mg/m2 ifosfamide (16). The preoperative and postoperative

(the dedifferentiated liposarcoma only) regimen for the soft tissue

sarcomas consisted of 1–3 cycles of 60–75 mg/m2

doxorubicin, 4–5 mg/m2 ifosfamide, and lenograstim (100

µg) every 3 weeks (17). Toxic

effects were assessed using the National Cancer Institute common

toxicity criteria (version 1) (17).

Statistical analysis

The 5-year survival rate was determined using the

Kaplan-Meier method, and differences were assessed using the

log-rank test, and P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference. Statistical analysis was

performed with Stat Mate (Atms, Tokyo, Japan) software for Windows,

version 4.01. Recurrence rates, metastasis, ECOG-PS (18), and ASA-PS (19) were also examined. We compared the

outcomes in all cases to determine the best treatment strategy for

elderly sarcoma patients.

Results

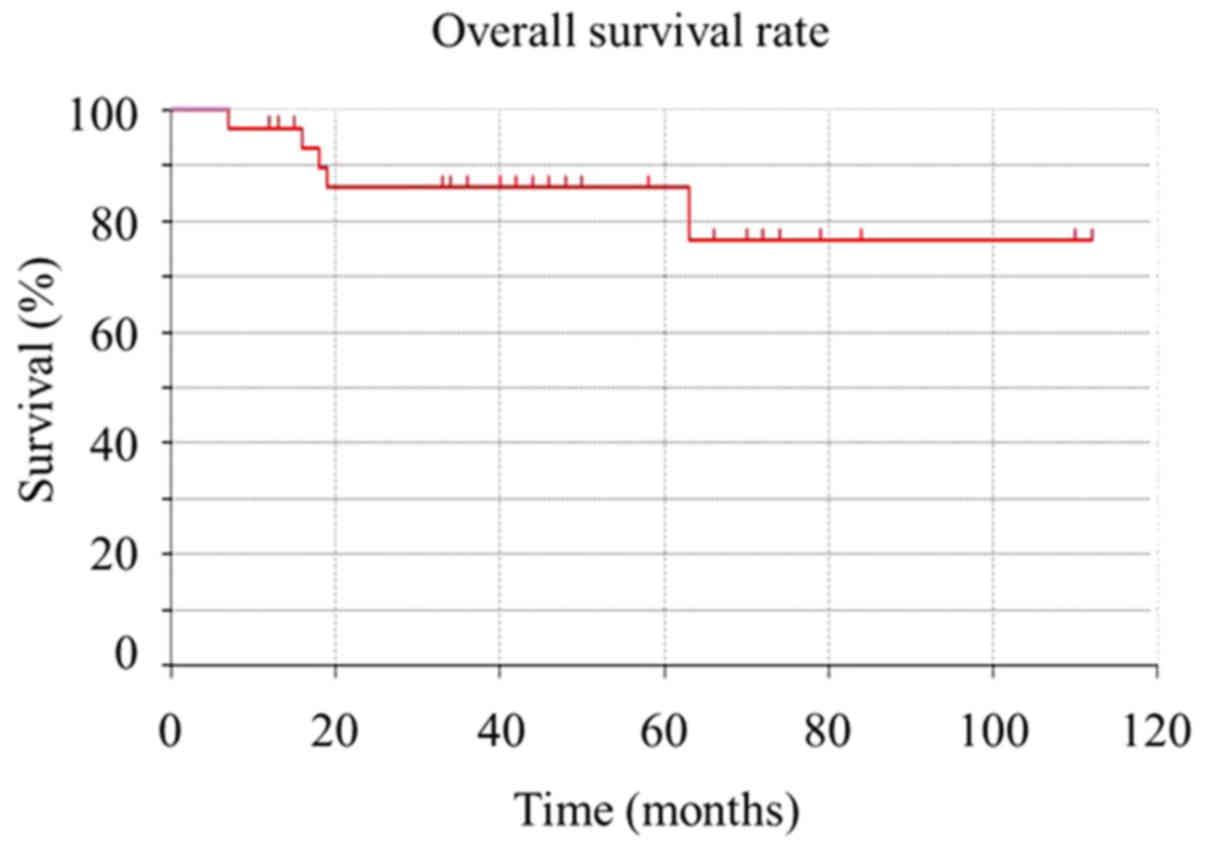

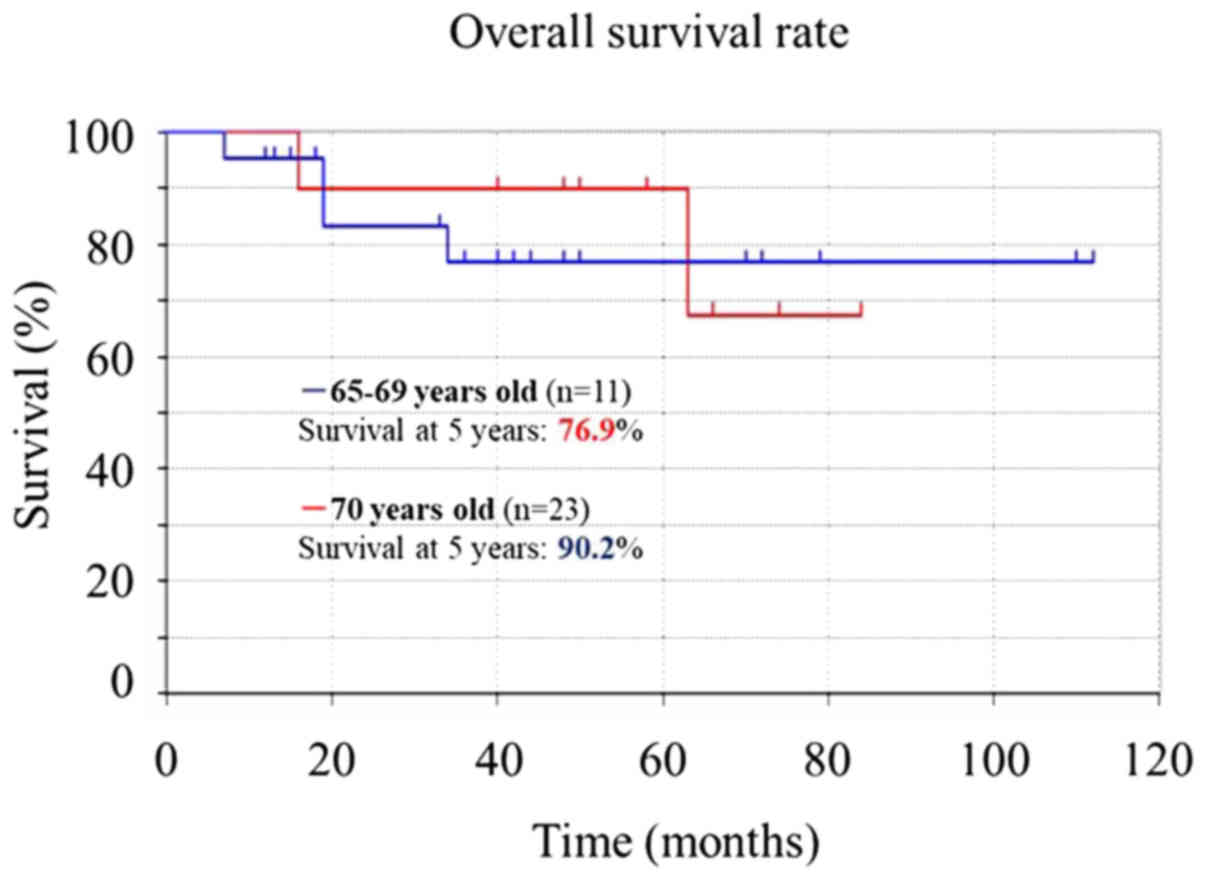

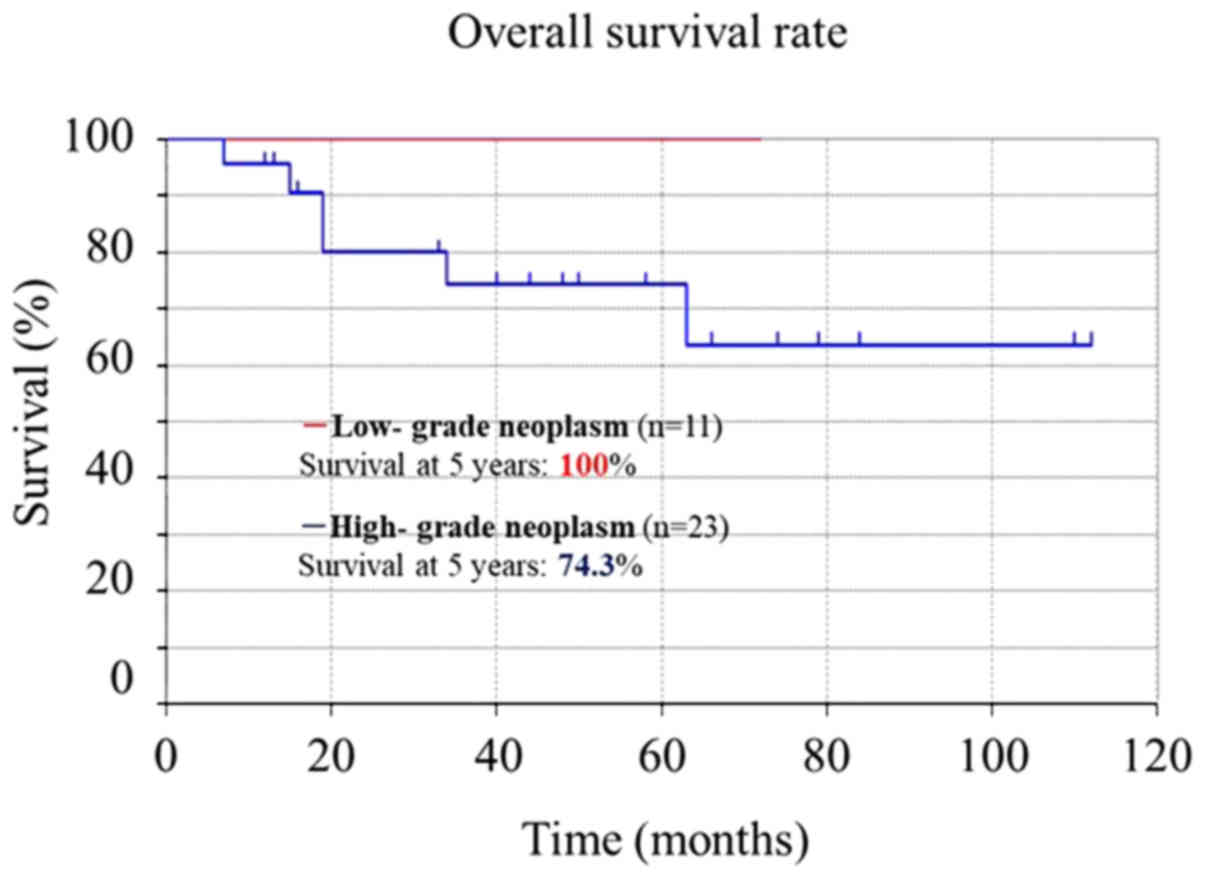

The 5-year overall survival rate for the patients in

this study was 86.02% (Fig. 1). It

did not differ significantly in patients 65–69 (76.9%) vs. ≥70

(90.2%) years-old (P=0.65) (Fig. 2),

but was significantly higher in those with low-grade (100%) vs.

high-grade (74.3%) neoplasms (P<0.001) (Fig. 3).

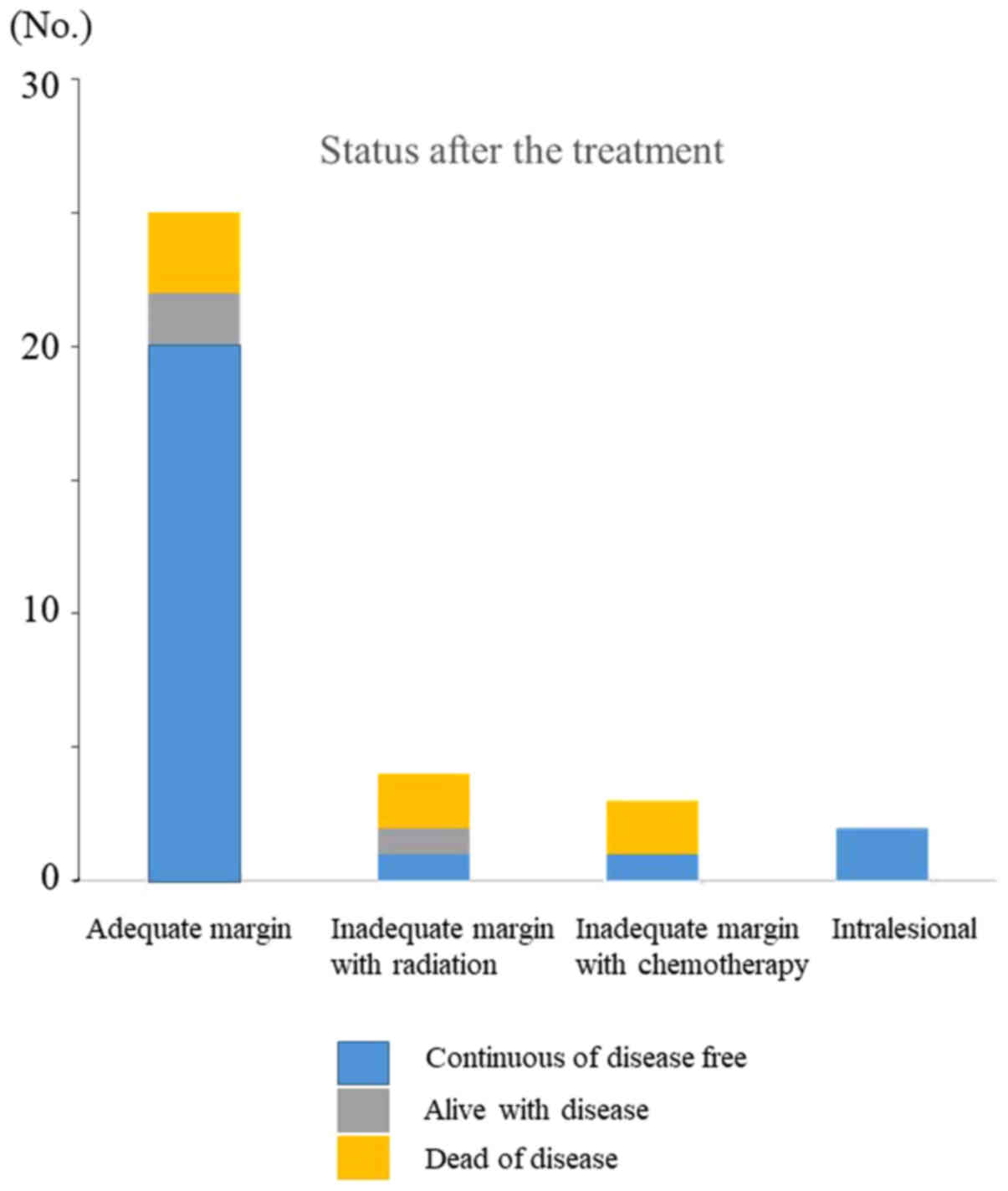

Tumor status was classified as continuously

disease-free (CDF) in 24 cases, alive with disease (AWD) in 3

cases, and dead of disease (DOD) in 7 cases (Table I). Tumor status according to

treatment was as follows: i) Surgery with adequate surgical

margins: CDF, 20 cases; AWD, 2 cases; and DOD, 3 cases; ii) surgery

with inadequate margins and radiotherapy: CDF, 1 case; AWD, 1 case

and DOD, 2 cases; iii) surgery with inadequate margins and

chemotherapy: CDF, 1 case and DOD, 2 cases; and iv) surgery with

intralesional margins: CDF, 2 cases (Fig. 4). After these treatments, tumors

recurred in 4/25 cases (16%), 3/4 cases (75%), 2/3 cases (67%), and

1/2 cases (50%), respectively. The recurrence rate was

significantly lower in cases with adequate margins (4/25, 16%) than

in cases with inadequate margins (6/9, 67%) (odds ratio, 0.24;

Fisher's exact test). Seven of the 10 recurrences were localized,

whereas 3 metastasized to the lung. The mean time before recurrence

was 10.3 months (range, 3–21 months). All metastatic lesions

present at the initial visit were also present after surgery, with

1 increasing in size.

Adverse events due to radiotherapy included

lymphedema, which occurred in 2 patients 6–12 months after the

therapy. Hematological and biological grade 0–2 adverse events were

observed during chemotherapy (Table

II).

| Table II.Chemotherapy-associated

toxicities. |

Table II.

Chemotherapy-associated

toxicities.

|

| Grade |

|---|

|

|

|

|---|

| Toxicity | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|

| Hematological,

n |

|

Hemoglobin | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| White

blood cells | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

|

Neutrophils | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

Platelets | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Biochemical, n |

|

AST | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

ALT | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

Creatinine | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

Bilirubin | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Clinical, n |

|

Nausea | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

Vomiting | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

Diarrhea | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

Alopecia | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

Mucositis | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

Infection | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

Fever | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

Neurological | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

Cardiac | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

The preoperative ECOG-PS scores were 0 in 9 cases, 1

in 21 cases, and 2 in 4 cases (Table

I). They were unchanged after treatment. The preoperative

ASA-PS scores were also I in 9 cases, and II in 23 cases (Table I).

Discussion

In general, almost all sarcoma patients are 40–60

years-old (3,12). However, the number of patients at the

upper end of this range is increasing (12). In the present study, the outcome for

sarcoma patients aged 65 years or older was almost always

favorable. Most patients in the study received surgery with

adequate margins (25/34), and such treatment may be necessary for a

good outcome.

In our study, the 5-year overall survival rate for

elderly patients with primary malignant bone or soft tissue tumors

was 86.02%, which is higher than previously reported rates

(35.0–83.0%, Table III) (4–10). This

may reflect our more frequent achievement of adequate margins

(73.5% of cases) (6,8–10) and

much lower ECOG-PS and ASA-PS scores (6,9,10).

| Table III.Previous studies of elderly patients

with bone and soft tissue tumors. |

Table III.

Previous studies of elderly patients

with bone and soft tissue tumors.

| Author, year | Age (years) | No. of

patients | Surgical

margins | Prognostic

factors | 5-year survival

rate (%) | Follow-up, mean

(range) | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Osaka et al,

2003 | ≥65 | 25 | Wide (76%),

marginal | Age, grade | 79.6 | 91.6 months (4–180

months) | (5) |

|

|

|

| (16%),

intralesional (8%) |

|

|

|

|

| Boden, 2006 | ≥80 | 50 | Clear (76%) | Not identified | 46.0 | 22 months (12–3210

days) | (7) |

| Lahat et al,

2009 | ≥65 | 295 | Negative (63.1%),

positive (27.7%) | Age, tumor size,

grade | 63.0 | 65 months (1–162

months) | (6) |

| Torigoe et al,

2010 | ≥70 | 14 | Wide and

amputation | Bone tumor,

grade | 35.0 | 37 months (2–137

days) | (4) |

|

|

|

| (85.7%), marginal

(14.3%) |

|

|

|

|

| Kozawa et al,

2014 | ≥65 | 78 | Wide (71.8%),

marginal | Not identified | 72.0 | 38 months (1.4–160

days) | (8) |

|

|

|

| (11.5%),

intralesional (3.8%) |

|

|

|

|

| Yoneda et al,

2014 | ≥70 | 158 | Adequate wide

(66.5%), inadequate wide (33.5%) | Male sex,

grade | 83.0 | 38 months (12–186

months) | (9) |

| Iwai et al,

2015 | ≥65 | 90 | Wide (65.5%),

marginal | ASA-PS, grade | 77.5 | 44.8 months (1–163

months) | (10) |

|

|

|

| (18.9%),

intralesional (3.3%) |

|

|

|

|

| Present case | ≥65 | 34 | Adequate wide

(73.5%), inadequate wide (20.6%), intralesional (5.9%) | Not identified | 86.0 | 49 months (7–112

months) | – |

The tumor subtypes in our study are similar to those

in a previous study of all age groups (20), as are the tumor sites (mainly in the

limbs, with a minority in the head, neck, and trunk) (21). When age-matched cohorts are compared,

the percentage of high-grade tumors is higher in our study (68%)

than a previous study (32%) (22).

Although 68% of our cases had complications preoperatively, all

cases were amenable to surgical treatment, with no reductions in

both ECOG-PS and ASA-PS scores or worsening of complications

postoperatively.

Previously, it had been reported that 5-year

survival rates for elderly sarcoma patients ranged from 35.0–83.0%

(4–10), with various studies suggesting that

5-year survival rates were worse in older than in younger patients

(5,6). One study, for example, reported 5-year

survival rates of 46 and 63% for older and younger patients,

respectively (22). In the present

study, the 5-year survival rate for elderly sarcoma patients was

86.02%, which is better than previously reported rates for older

patients (70%) (23) and is like

that for younger patients (89.59%) (24). These findings suggest that age itself

may not affect survival of sarcoma patients.

As shown here and in previous studies, elderly

patients with high-grade sarcomas have a poorer prognosis than

those with low-grade sarcomas (4,5,10). Hence, the histological grade of the

sarcoma appears to affect the prognosis of elderly patients. Others

reported a local recurrence rate of 9% at the 20-month follow-up in

elderly sarcoma patients (9), as

well as a local recurrence rate of 22% at the 22-month follow-up in

sarcoma patients 80 years or older (7). Therefore, the recurrence rate may be

somewhat worse in older (22%) than younger sarcoma patients (9%)

(7,9).

Achieving adequate surgical margins is an important

component in sarcoma treatment for elderly patients, as shown both

here and by others (5,6,9). The

surgical resection protocol is very similar for older and younger

sarcoma patients, whereas the use of adjuvant radiotherapy may

differ. As a general policy, our unit recommends radiotherapy for

all patients with large high-grade tumors or intermediate- or

high-grade tumors of any size where the wide margin is not clear.

However, when dealing with very elderly patients, additional

considerations are warranted. A previous report suggests that

outpatient radiotherapy is too burdensome for elderly sarcoma

patients (7). In the present study,

we administered radiotherapy to 4 elderly sarcoma patients as an

in-hospital treatment. Although their physical status did not

decline, the efficacy of this treatment could not be confirmed.

According to the European Society for Medical

Oncology Guidelines (25), adjuvant

chemotherapy may delay or reduce the incidence of distant and local

recurrence in high-risk sarcoma patients. In elderly patients with

high-grade malignant bone tumors, the use of chemotherapy is

controversial. Adriamycin and ifosfamide are the main chemotherapy

drugs for sarcoma (26). Since

systemic chemotherapy may impair cardiac and renal function in

elderly sarcoma patients (27,28), it

should be limited to those patients without health problems. None

of the 3 patients in our study who received chemotherapy appeared

to benefit from the therapy. Chemotherapy did not worsen physical

function in the others. Regardless of whether it is low-dose (80%)

or high-dose, chemotherapy should be carefully administered to

patients selected on the basis of age and ECOG-PS.

Patient status is mainly evaluated by determining

ECOG-PS and ASA-PS scores (18,19).

ECOG-PS is based on the patient's daily activities (18), whereas ASA-PS is based on the

patient's medical condition (mainly the presence or absence of

systemic diseases) (19). Both

systems were useful for avoiding excessive treatment of the elderly

sarcoma patients in our study. ASA-PS is a potential prognostic

factor for elderly sarcoma patients (10). Whether ECOG-PS is also predictive is

not known and should be addressed in the future. We were unable to

do so in the present study, since we did not review the patients

with poor ECOG-PS scores (≥3). Studies focusing on elderly sarcoma

patients with poor ECOG-PS or ASA-PS (≥3) scores are needed.

Our study has some limitations. First, there was

potential selection bias since not all elderly patients are good

candidates for surgery. Second, the number of patients in our study

was low. The low number did not, however, preclude statistical

analysis of the data. Third, our study included only 2 cases of

malignant bone tumors. Fourth, we included well-differentiated

liposarcomas, which are currently classified as intermediate tumors

by the World Health Organization (29). However, at the time their treatment

(2004–2012), they were classified as malignant tumors.

Our results suggest that surgery with adequate

margins improves the prognosis of sarcoma patients 65 years-old.

However, further study is required to clarify the indications for

chemotherapy and radiotherapy in the elderly.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the present

study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

KH, SN, YH, NO, HT, SI and MA performed the study,

and collated, analyzed and interpreted the data. KH, SN, and MA

wrote the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All patients provided written informed consent for

this retrospective study.

Patient consent for publication

All patients provided written informed consent for

the publication of this retrospective study.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

ASA-PS

|

Anesthesiologists-Physical Status

|

|

ECOG-PS

|

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

Performance Status

|

References

|

1

|

Montgomery W, Ueda K, Jorgensen M, Stathis

S, Cheng Y and Nakamura T: Epidemiology, associated burden, and

current clinical practice for the diagnosis and management of

Alzheimer's disease in Japan. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 10:13–28.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Cabinet office, Government of Japan: Wite

paper on aged society. http://www8.cao.go.jp/kourei/whitepaper/w-2017/zenbun/29pdf_index.htmlSeptember

4–2018

|

|

3

|

Balducci L and Erchler WB: Cancer and

aging: A nexus at several levels. Nat Rev Cancer. 5:655–662. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Torigoe T, Terakado A, Suehara Y, Kurosawa

H, Yazawa Y and Takagi T: Bone versus soft-tissue sarcomas in the

elderly. J Orthop Surg. 18:58–62. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Osaka S, Sugita H, Osaka E, Yoshida Y and

Ryu J: Surgical management of malignant soft tissue tumours in

patients aged 65 years or older. J Orthop Surg. 11:28–33. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Lahat G, Dhuka AR, Lahat S, Lazar AJ,

Lewis VO, Lin PP, Feig B, Cormier JN, Hunt KK, Pisters PW, et al:

Complete soft tissue sarcoma resection is a viable treatment option

for select elderly patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 16:2579–2586. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Boden RA, Clark MA, Neuhaus SJ, A'hern JR,

Thomas JM and Hayes AJ: Surgical management of soft tissue sarcoma

in patients over 80 years. Eur J Surg Oncol. 32:1154–1158. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Kozawa E, Sugiura H, Tsukushi S, Urakawa

H, Arai E, Futamura N, Nakashima H, Yamada Y, Ishiguro N and

Nishida Y: Multiple primary malignancies in elderly patients with

high-grade soft tissue sarcoma. Int J Clin Oncol. 19:384–390. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Yoneda Y, Kunisada T, Naka N, Nishida Y,

Kawai A, Morii T, Takeda K, Hasei J, Yamakawa Y and Ozaki T:

Japanese Musculoskeletal Oncology Group: Favorable outcome after

complete resection in elderly soft tissue sarcoma patients:

Japanese musculoskeletal oncology group study. Eur J Surg Oncol.

40:49–54. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Iwai T, Hoshi M, Takada J, Oebisu N, Aono

M, Takami M, Ieguchi M and Nakamura H: Prognostic factors for

elderly patients with primary malignant bone and soft tissue

tumors. Oncol Lett. 10:1799–1804. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Fletcher CD; Unni KK and Mertens F: World

Health Organization Classification of Tumors. Pathology and

Genetics of Tumors of Soft Tissue and Bone. Rydholm A, Singer S,

Sundaram M and Coinche JM: IARC Press; Lyon: pp. 12–18. 2002,

PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Weiss SW and Goldblum JR: Enzinger and

Weiss's Soft Tissue Tumors. Folpe AL: 4th. Mosby, St; Louis, MO:

pp. 1–10. 2001

|

|

13

|

Lee FY, Mankin HJ, Fondren G, Gebhardt MC,

Springfield DS, Rosenberg AE and Jennings LC: Chondrosarcoma of

bone: An assessment of outcome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 81:326–338.

1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Kawaguchi N, Ahmed AR, Matsumoto S, Manabe

J and Matsushita Y: The concept of curative margin in surgery for

bone and soft tissue sarcoma. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 419:165–172.

2004. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Gundle KR, Kafchinski L, Gupta S, Griffin

AM, Dickson BC, Chung PW, Catton CN, O'Sullivan B, Wunder JS and

Ferguson PC: Analysis of margin classification systems for

assessing the risk of local recurrence after soft tissue sarcoma

resection. J Clin Oncol. 36:704–709. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Iwamoto Y, Tanaka K, Isu K, Kawai A,

Tatezaki S, Ishii T, Kushida K, Beppu Y, Usui M, Tateishi A, et al:

Multiinstitutional phase II study of neoadjuvant chemotherapy for

osteosarcoma (NECO study) in Japan: NECO-93J and NECO-95J. J Orthop

Sci. 14:397–404. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Woll PJ, Reichardt P, Le Cesne A, Bonvalot

S, Azzarelli A, Hoekstra HJ, Leahy M, Van Coevorden F, Verweij J,

Hogendoorn PC, et al: Adjuvant chemotherapy with doxorubicin,

ifosfamide, and lenograstim for resected soft-tissue sarcoma (EORTC

62931): A multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol.

13:1045–1054. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, Horton J,

Davis TE, McFadden ET and Carbone PP: Toxicity and response

criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin

Oncol. 5:649–655. 1982. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Hosking MP, Warner MA, Lobdell CM, Offord

KP and Melton LJ III: Outcomes of surgery in patients 90 years of

age and older. JAMA. 261:1909–1915. 1989. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Pitcher ME, Fish S and Thomas JM:

Management of soft tissue sarcoma. Br J Surg. 81:1136–1139. 1994.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Clark MA, Fisher C, Judson I and Thomas

JM: Soft-tissue sarcomas in adults. N Engl J Med. 353:701–711.

2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Ramanathan RC, A'Hern R, Fisher C and

Thomas JM: Prognostic index for extremity soft tissue sarcoma with

isolated local recurrence. Ann Surg Oncol. 8:278–289. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Harrison DJ, Geller DS, Gill JD, Lewis VO

and Gorlicl R: Current and future therapeutic approaches for

osteosarcoma. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 18:39–50. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Hager S, Makowiec F, Henne K, Hopt UT and

Wittel UA: Significant benefits in survival by the use of surgery

combined with radiotherapy for retroperitoneal soft tissue sarcoma.

Radiat Oncol. 12:292017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

ESMO/European Sarcoma Network Working

Group: Soft tissue, visceral sarcomas: ESMO clinical practice

guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 23

Suppl 7:vii92–vii99. 2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Linch M, Miah AB, Thway K, Judson IR and

Benson C: Systemic treatment of soft-tissue sarcoma-gold standard

and novel therapies. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 11:187–202. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Farry JK, Flombaum CD and Latcha S: Long

term renal toxicity of ifosfamide in adult patients-5 year data.

Eur J Cancer. 48:1326–1331. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Matushansky I, Dela Cruz F, Insel BJ,

Hershman DL and Neugut AI: Chemotherapy use in elderly patients

with soft tissue sarcoma: A population-based study. Cancer Invest.

31:83–91. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Fletcher CD, Bridge JA, Hogendoom PC and

Mertens F: WHO Classification of Tumors of Soft Tissue and Bone.

Mertens F (eds). 4th edition. IARC Publications, France,. 5:33–38.

2013.

|