Introduction

Postoperative cognitive dysfunction (POCD) is a

common postsurgical complication of the central nervous system.

POCD occurs at an early stage of postoperative care and increases

the rates of perioperative mortality (1). The pathogenesis and prevention of POCD

have been extensively studied. The mechanism underlying the

behavioral alterations following surgery in animal models may be

associated with the dysfunction of neurons and synapses (2–6). It has

been hypothesized that the production and aggregation of amyloid β

(Aβ), and the abnormal hyperphosphorylation and aggregation of tau

protein may be involved in the pathogenesis of POCD (7). Aβ may alter the mitochondrial

morphology and affect the steady state of calcium in the neurons

(8). The hyperphosphorylation and

aggregation of tau protein serves an important role in

neurodegeneration (9).

The neuroprotective effect of α-lipoic acid (ALA)

has been previously studied (10)

and it was demonstrated that ALA promotes the secretion of leptin

from adipocytes (11). A number of

studies reported that leptin induces a protective effect on the

cognitive function (12–15). Leptin regulates glucose and fat

metabolism, and the leptin receptor activates brain-derived

neurotrophic factor to regulate the synaptic plasticity and promote

neural differentiation (12,13). Furthermore, leptin reduces the

hyperphosphorylation of tau protein (14–16).

There are no effective treatment methods for

patients with POCD and the underlying mechanism of this conditions

remains to be elucidated. To the best of the authors' knowledge,

the current study is the first to investigate the effect of ALA on

POCD and the underlying mechanism of action. The present study

aimed to investigate the effect of ALA on POCD induced by

hepatectomy in wild type (WT) and leptin receptor-deficient (db/db)

mice. Protein expression levels of Cdk5, phosphorylated tau (p-tau)

and Aβ were determined by western blotting, and the ultrastructure

of hippocampal neurons and synapses was analyzed by transmission

electron microscopy.

Materials and methods

Experimental animals

A total of 60 WT C57BL/6 mice and 60 db/db C57BL/6

mice (all male; weight, 20–25 g; age, 14 weeks) were obtained from

Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd.

(Beijing, China). Mice were housed with a 12 h light/dark cycle at

a temperature of 24±1°C with access to food and water ad

libitum. ALA (60 mg/kg; Wyeth Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Suzhou,

China) or 1% dimethyl sulfoxide in corn oil (vehicle) was

administrated orally daily. At the end of the experiment, the

animals were euthanized by intraperitoneal administration of a

lethal dose of sodium pentobarbital (150 mg/kg). The present study

was approved by the Institution Animal Care and Use Committee of

Nanjing First Hospital (Nanjing, China).

Animal grouping

C57BL/6 WT and db/db mice were divided randomly into

three groups each, including the control, surgery and ALA + surgery

groups (20 mice/group). Control group mice received anesthesia

only, the surgery group received 70% hepatectomy surgery, and the

ALA + surgery group was intragastrically administrated 100 mg/kg

ALA once daily for 12 weeks (17),

and subsequently received 70% hepatectomy surgery. The control and

surgery groups received the same volume of vehicle intragastrically

(WT, 20 µl/mice; db/db, 30 µl/mice).

Hepatectomy surgery

Mice were anesthetized by an intraperitoneal

injection of 50 mg/kg sodium pentobarbital (1% in saline). Mice

were subsequently placed on a warming blanket and rectal

temperatures were monitored. A roll of gauze was placed under the

right scapula to provide adequate exposure of the liver. The

abdomen of the mice was shaved, sterilized and draped. A 1–1.5-cm

midline incision was made from the xiphoid inferiorly with micro

dissecting scissors. The upper abdomen was opened and the three

anterior lobes of the liver were isolated (~68% of the total liver

weight), including the right upper lobe, left upper lobe and left

lower lobe. Three knots were tied with moistened silk suture at the

base of the lobes near the inferior vena cava. The tied lobes were

subsequently cut immediately distal to the suture. The abdomen was

irrigated with 2 ml of sterile saline (37°C) to ensure the removal

of blood and to decrease contamination. Gentle pressure was applied

on the abdomen with sterile gauze to remove residual irrigation.

The wound was infiltrated with 0.25% bupivacaine to relieve pain.

The peritoneum and the skin were subsequently closed separately

with silk suture. The mice were placed under warming lights while

waking up from anesthesia, and subsequently housed individually

(18).

Morris water maze (MWM)

Cognitive function was assessed using a 5-day MWM

test as previously described (19).

A round tub was used for the MWM task and filled with water mixed

with nontoxic black paint to submerge a platform 1 cm below the

water surface (water temperature, 19–24°C). Visual distal cues were

located on the walls. During the first four days, mice were given

four trials/day using a random starting location. If mice did not

reach the platform within 60 sec, they were gently guided to the

hidden platform. The latency to reach the platform was recorded

from all sessions, and averaged to calculate the escape latency for

each day. On day 5, the platform was removed for probe testing.

Mice were allowed to swim freely for 60 sec. The number of

crossings over the platform that had served as the target on days

1–4 was recorded. The time spent in the quadrant where the target

platform was located was recorded. Data were collected and analyzed

using motion detection software (DigBehv-MM; Shanghai Jiliang

Software Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China).

Transmission electron microscopy

Mice were intraperitoneally injected with 1%

pentobarbital sodium (35 mg/kg) and then fixed on a foam plate. A

large U-shaped incision was cut into the chest to expose the heart.

The perfused needle was inserted into the apical part with 5 mm

depth and fixed by hemostatic clamp. Heparin saline was infused

until liver became pale, followed with 3% glutaraldehyde perfusion.

The brain was removed, and the hippocampus was isolated and

post-fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde solution for 2 h in 4°C, followed

by embedding in the epoxy resin for 12 h at 45°C. The embedded

tissues were cut into 50–70-nm-thick sections and mounted on 150

mesh copper grids. Following staining with uranyl acetate and lead

citrate for 12 h in 4°C, the specimens were observed under a

transmission electron microscope (HITACHI-7650; Hitachi, Ltd.,

Tokyo, Japan).

Western blotting

The hippocampal tissue was homogenized with Tris-HCl

(pH 7.4; 50 mM), 1% Triton X-100, 0.2% sodium deoxycholate, 0.2%SDS

and 1 mM EDTA (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Shanghai,

China), and centrifuged at 8,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C. The protein

concentration from each mouse was tested using the bicinchoninic

acid method. Protein (40 µg/lane) was separated by SDS-PAGE (12%

gel) and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane

(Hybond® ECL™; GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA).

Membranes were blocked with 5% milk and 0.1% Tween-20 in PBS for 1

h at room temperature. Membranes were then incubated with primary

antibodies against Cdk5 (cat. no. ab21249), tau (cat. no. ab80579),

β-actin (cat. no. ab8227; all 1:1,000), Aβ (cat. no. ab10148;

1:7,000; all Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) and p-tau (cat. no.

44-750G; 1:1,000; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA)

overnight at 4°C. After washing with tris buffered saline with

Tween-20 (TBST) three times, membranes were incubated with

anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (cat. no. ab6721; 1:2,000; Abcam)

for 2 h at room temperature. Between steps, blots were washed with

TBST. Immunodetection was performed using a LumiGLO

chemiluminescence kit (Amersham; GE Healthcare). Bands were

analyzed by Quantity One software (version 4.6.2; Bio-Rad

Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA).

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as the mean ± standard

deviation. Data were analyzed using SPSS software (version 17.0;

SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) or GraphPad Prism (version 5.0;

GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). Two-way analysis of

variance (ANOVA) was used to analyze the spatial memory data

obtained from the MWM test. The levels of protein and gene

expression were analyzed using one-way ANOVA. ANOVA analyses were

followed by the Bonferroni post-hoc test. P<0.05 was considered

to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

ALA rescues the impaired cognitive

function in WT but not db/db mice

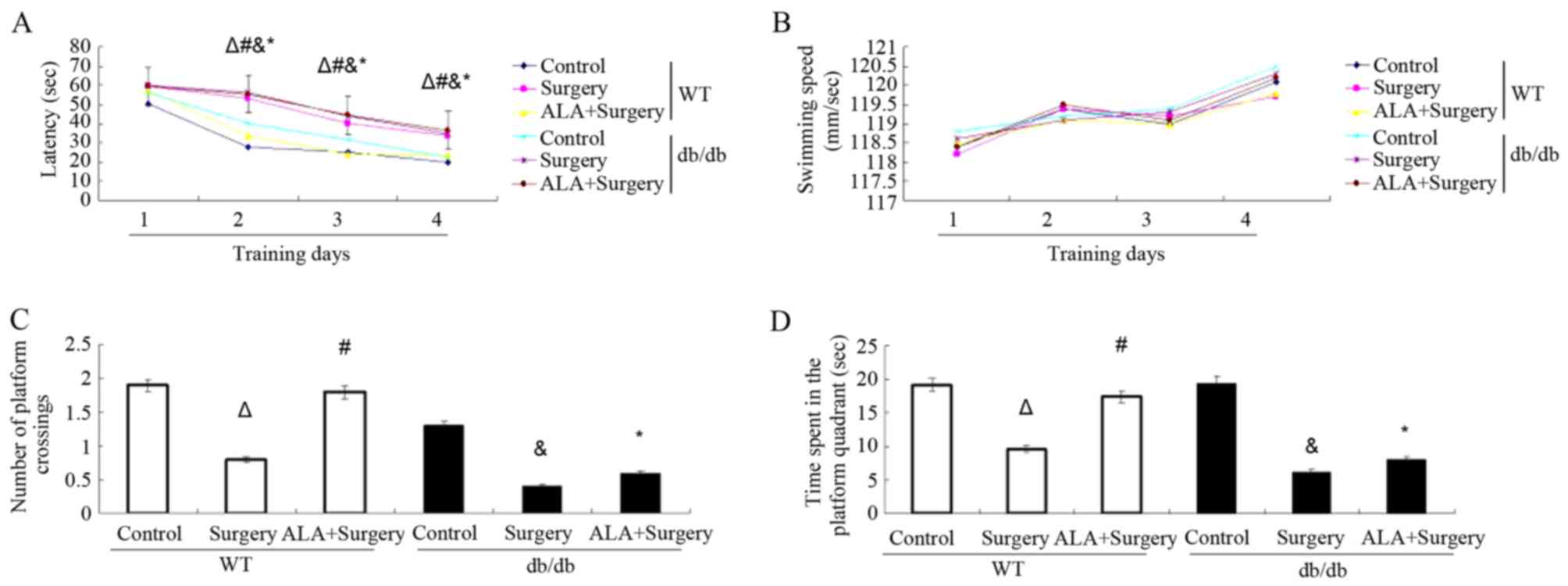

To study cognitive function, MWM was used to examine

spatial learning and memory in both WT and db/db mice with or

without treatment with ALA. Among the WT mice, the surgery group

(day 2, 53.0±5.3; day 3, 40.1±6.7; day 4, 33.8±4.1) exhibited

significantly longer latency to find the platform compared with the

control group (day 2, 27.7±3.7; day 3, 25.0±5.9; day 4, 19.9±3.9;

all P<0.01). Among the db/db mice, the surgery group (day 2,

56.3±2.1; day 3, 43.8±3.0; day 4, 35.0±1.5) exhibited significantly

longer latency to find the platform compared with the control group

(day 2, 40.3±6.9; day 3, 31.8±6.3; day 4, 22.3±3.9; P<0.01). The

db/db ALA + surgery group (day 2, 55.4±2.2; day 3, 44.5±4.8; day 4:

36.7±4.3) did not exhibit altered latency compared with the surgery

only group (P>0.05; Fig. 1A).

However, the db/db ALA + surgery group exhibited significantly

longer latency compared with the WT ALA + surgery group (P<0.01;

Fig. 1A). These results suggest that

hepatectomy surgery prolonged the escape latency during the MWM

test in both WT and db/db mice. Treatment with ALA alleviated the

effect induced by surgery in WT mice but not in db/db mice. The

swimming speed was recorded during the leaning sessions in the MWM

test. The results revealed that there were no differences in the

swimming speed among the control, surgery and ALA + surgery groups

in WT and db/db mice (Fig. 1B).

On probe testing day, WT mice in the surgery group

crossed the target quadrant fewer times (0.8±0.5 vs. 1.9±0.8;

P<0.01) and spent less time in the platform quadrant (9.6±7.7

vs. 19.2±6.3; P<0.01) compared with the control group. Treatment

with ALA increased the time spent in the platform quadrant

(17.4±8.0 vs. 9.6±7.7; P<0.05) and crossing number (1.8±0.6 vs.

0.8±0.5; P<0.05) in the target quadrant compared with the

surgery group. Among the db/db mice, the surgery group crossed the

target quadrant fewer times (0.4±0.3 vs. 1.3±0.9; P<0.01) and

spent less time in the platform quadrant (6.2±3.0 vs. 19.5±6.9;

P<0.01) compared with the control group. However, the crossing

number (0.6±0.4 vs. 0.4±0.3; P>0.05) and time spent in the

platform quadrant (8.0±5.4 vs. 6.2±3.0; P>0.05) remained

unaltered following administration of ALA compared with the surgery

group among the db/db mice (Fig. 1C and

D). The ALA + surgery group db/db mice spent less time in the

platform quadrant (8.0±3.1 vs. 17.4±8.0; P<0.01) and crossed the

platform fewer times (0.6±0.3 vs. 1.8±0.6; P<0.05) compared to

ALA + surgery group WT mice (P<0.01; Fig. 1C and D).

Hepatectomy increases Cdk5, p-tau and

Aβ protein levels in both WT and db/db mice, and this effect is

reversed following treatment with ALA among WT mice but not db/db

mice

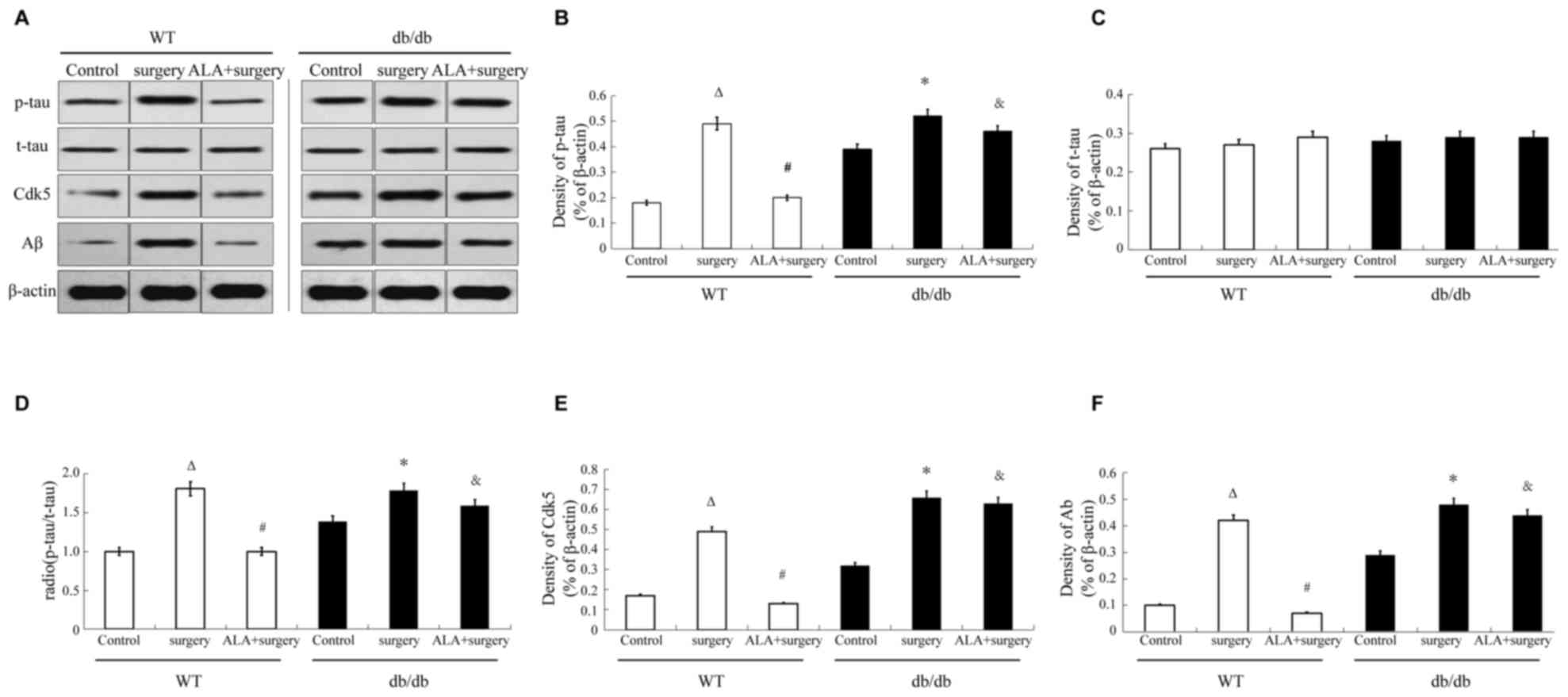

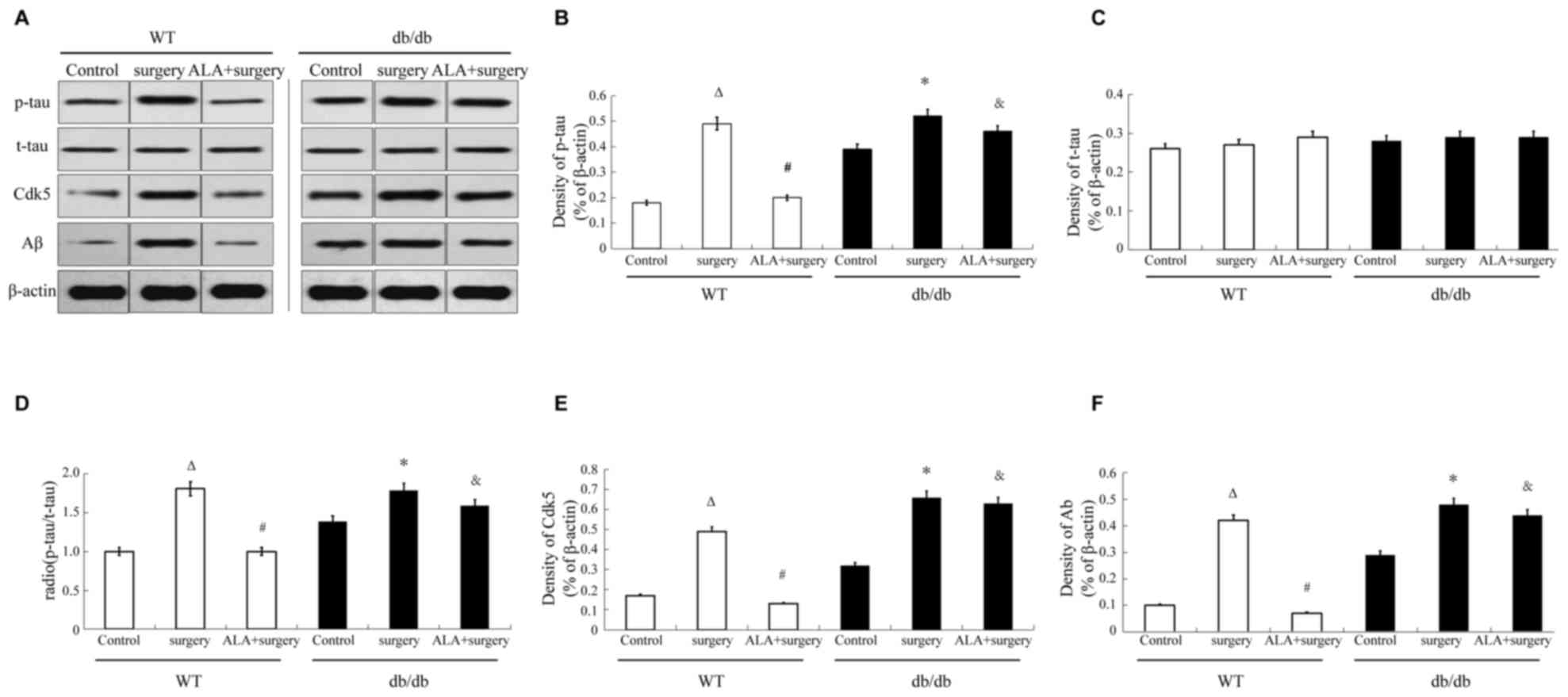

Western blotting was used to assess the expression

levels of cognitive function-associated proteins Cdk5 and Aβ and

the phosphorylation levels of tau. Among the WT mice, surgery

significantly increased the protein expression of Cdk5 and Aβ and

the p/total (t) tau ratio in the hippocampus compared with the

control group (P<0.01). Administration pf ALA following surgery

significantly reduced the protein expression of Cdk5 and Aβ, and

the p/t tau ratio in the hippocampus compared with the surgery

group (P<0.05; Fig. 2).

| Figure 2.Effects of ALA on surgery-induced

alterations in Cdk5 and Aβ protein expression levels and p/t tau

ratio in the hippocampus. (A) Representative images of western

blotting for the analysis of p-tau, t-tau, Cdk5, Aβ and β-actin

protein expression. (B) Quantitative analysis of p-tau protein

expression relative to β-actin. (C) Quantitative analysis of t-tau

protein expression relative to β-actin. (D) Quantitative analysis

of p-tau to t-tau protein expression ratio. (E) Quantitative

analysis of Cdk5 protein expression relative to β-actin. (F)

Quantitative analysis of Aβ protein expression relative to β-actin.

Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (n=5/group).

∆P<0.01 compared with the WT control group;

#P<0.05 compared with the surgery group; *P<0.01

compared with the db/db control group; &P<0.01

compared with the WT ALA + surgery group. ALA, α-lipoic acid; WT,

wild type; db/db, leptin receptor-deficient mice; p,

phosphorylated; t, total; Cdk5, cyclin-dependent kinase 5; Aβ,

amyloid β. |

Among the db/db mice, surgery significantly

increased the protein expression of Cdk5 and Aβ and the p/total (t)

tau ratio in the hippocampus compared with the control group

(P<0.01). However, treatment with ALA did not alter the protein

expression of Cdk5 and Aβ or the p/t tau ratio compared with the

surgery group. The db/db ALA + surgery group mice exhibited

significantly increased expression of Cdk5 and Aβ, and p/t tau

ratio in the hippocampus compared with the WT ALA + surgery group

in mice (P<0.01; Fig. 2).

Hepatectomy impairs cellular structure

of the hippocampus of WT and db/db mice, and this effect is

reversed following treatment with ALA among WT mice but not db/db

mice

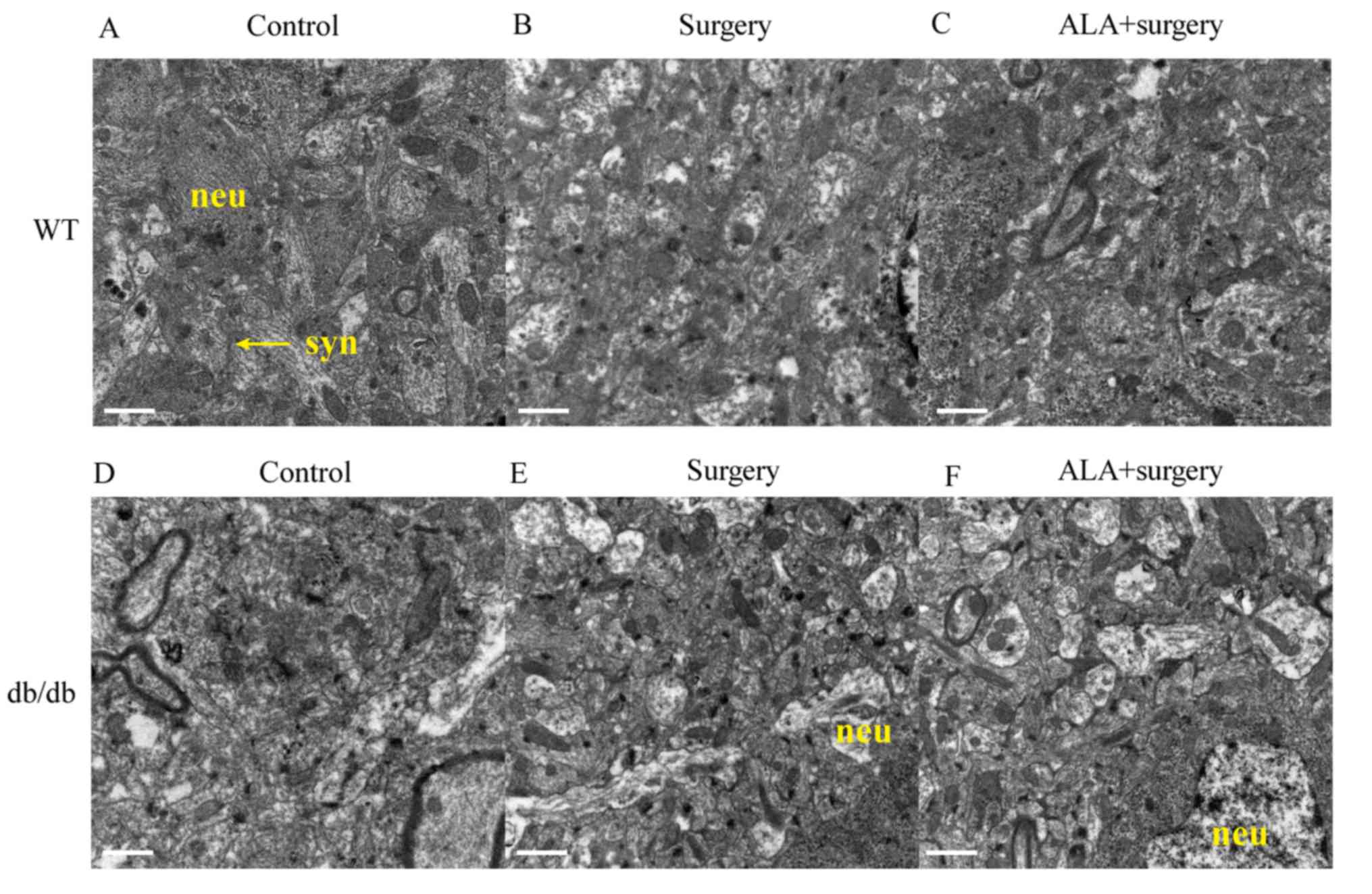

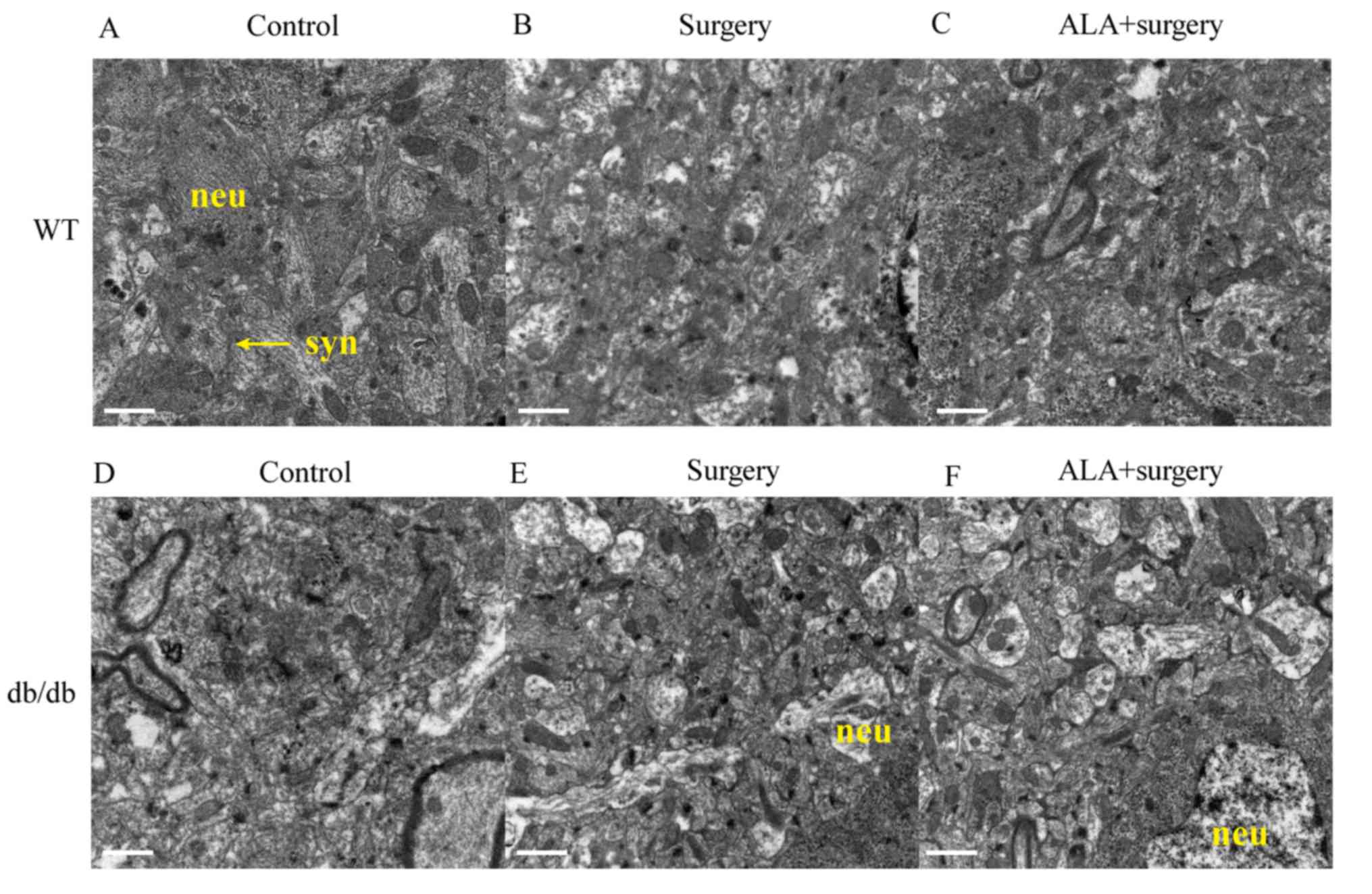

The ultrastructure of the CA3 hippocampal region was

analyzed using transmission electron microscopy (Fig. 3). The images revealed that among the

WT mice, surgery (Fig. 3B) impaired

the ultrastructure of hippocampal neurons, which exhibited

pyknosis, shrinkage of nuclear membrane, broadened perinuclear

space and reduced synaptic density. Administration of ALA after

surgery (Fig. 3C) improved the

neuronal structure in the hippocampus, which appeared similar to

the control group (Fig. 3A),

exhibiting a smooth nuclear membrane and normal synaptic density

and structure.

| Figure 3.Ultrastructure of neurons and synapses

in the hippocampus. The ultrastructure images from electron

microscopy presenting the results for (A) WT control group, (B) WT

surgery group, (C) WT ALA + surgery group, (D) db/db control group,

(E) db/db surgery group, (F) db/db ALA+surgery group. Scale bar=1

µm. Neu, neuron; syn, synapse; ALA, α-lipoic acid; WT, wild type;

db/db, leptin receptor-deficient mice. |

Among the db/db mice, surgery (Fig. 3E) impaired the ultrastructure of

hippocampal neurons and synapses compared with the control group.

However, treatment with ALA + surgery (Fig. 3F) did not repair the neuronal

structure in the hippocampus, which was different compared with the

normal structure of the control group (Fig. 3D).

Discussion

A previous study reported that ALA can increase the

level of leptin in serum through the regulation of Cdk5. Cdk5

serves an important role in neuron differentiation and synaptic

plasticity by phosphorylating cytoskeleton proteins and signaling

pathway molecules (16). Cdk5 is a

serine/threonine protein kinase that forms complexes with p35 or

p39 and is essential for neural development and function (20). Downregulation of CDK5 has been

demonstrated to mitigate hippocampal degeneration and cognitive

dysfunction (16).

The effects of ALA on the cognitive function

following hepatectomy and the possible underlying mechanism were

studied using db/db and WT mice. The results revelated that surgery

impaired postoperative cognitive function, increased the

hippocampal expression of Cdk5 and Aβ proteins and the

phosphorylation of tau, and damaged the structure of hippocampal

neurons and synapses in both WT and db/db mice. ALA rescued the

cognitive function of WT mice after surgery, as revealed by the

results of the MWM learning and test.

In addition, analysis of protein expression in the

hippocampus revealed that treatment with ALA decreased the elevated

protein expression levels of Cdk5 and Aβ and the p/t tau ratio in

WT mice subjected to surgery. However, this effect was not observed

among the db/db mice. The ultrastructure of neurons and synapses in

the hippocampus was observed in mice following surgery and

treatment with ALA. Hepatectomy markedly damaged the structure of

neurons and synapses in both WT and db/db mice. However, treatment

with ALA repaired the structure of neurons and synapses in WT mice,

but not the db/db mice. These results suggested that the

improvement in cognitive function following administration of ALA

may be associated with reduced protein expression levels of Cdk5

and Aβ, and the phosphorylation level of tau. Furthermore,

treatment with ALA enabled maintenance of the normal structure of

hippocampal neurons and synapses.

Treatment with ALA did not improve the cognitive

function of db/db mice following hepatectomy, which may suggest

that the leptin signaling pathway may be a potential target of ALA.

ALA may regulate the expression of leptin or regulate the biding to

leptin receptor to alter the expression levels of Cdk5 and Aβ, and

the phosphorylation level of tau to maintain the normal structure

of hippocampal neurons and synapses. Future studies should

investigate the effect of ALA on the leptin signaling pathway and

cognitive function in WT mice with hepatectomy.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The current study was supported by grants from the

National Natural Science Foundation (grant no. 81873954) and the

Medicine Development Project of Nanjing Scientific Committee (grant

no. YKK15089).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are

available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

YZ, HGB conceived the study design. YZ and YLL

performed the experiments. YNS, JWZ and YNQ participated in the

data analysis and interpretation.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Krenk L and Rasmussen LS: Postoperative

delirium and postoperative cognitive dysfunction in the

elderly-what are the differences? Minerva Anestesiol. 77:742–749.

2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Hovens IB, Schoemaker RG, van der Zee EA,

Absalom AR, Heineman E and van Leeuwen BL: Postoperative cognitive

dysfunction: Involvement of neuroinflammation and neuronal

functioning. Brain Behav Immun. 38:202–210. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Mézière A, Paillaud E and Plaud B:

Anesthesia in the elderly. Presse Med. 42:197–201. 2013.(In

French). View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Miyoshi E, Wietzikoski EC, Bortolanza M,

Boschen SL, Canteras NS, Izquierdo I and Da Cunha C: Both the

dorsal hippocampus and the dorsolateral striatum are needed for rat

navigation in the Morris water maze. Behav Brain Res. 226:171–178.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Sawamura S: Postoperative care of the

elderly. Nihon Rinsho. 71:1060–1064. 2013.(In Japanese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Wuri G, Wang DX, Zhou Y and Zhu SN:

Effects of surgical stress on long-term memory function in mice of

different ages. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 55:474–485. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Xie Z and Tanzi RE: Alzheimer's disease

and post-operative cognitive dysfunction. Exp Gerontol. 41:346–359.

2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Hovens IB, Schoemaker RG, van der Zee EA,

Heineman E, Nyakas C and van Leeuwen BL: Surgery-induced behavioral

changes in aged rats. Exp Gerontol. 48:1204–1211. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Gustafson DR: Adiposity and cognitive

decline: Underlying mechanisms. J Alzheimers Dis. 30 Suppl

2:S97–S112. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Deng C, Sun Z, Tong G, Yi W, Ma L, Zhao B,

Cheng L, Zhang J, Cao F and Yi D: α-Lipoic acid reduces infarct

size and preserves cardiac function in rat myocardial

ischemia/reperfusion injury through activation of PI3K/Akt/Nrf2

pathway. PLoS One. 8:e583712013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Kandeil MA, Amin KA, Hassanin KA, Ali KM

and Mohammed ET: Role of lipoic acid on insulin resistance and

leptin inexperimentally diabetic rats. J Diabetes Complications.

25:31–38. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Gupta A: Leptin as a neuroprotective agent

in glaucoma. Med Hypotheses. 81:797–802. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Folch J, Pedrós I, Patraca I, Sureda F,

Junyent F, Beas-Zarate C, Verdaguer E, Pallàs M, Auladell C and

Camins A: Neuroprotective and anti-ageing role of leptin. J Mol

Endocrinol. 49:R149–R156. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Irving AJ and Harvey J: Leptin regulation

of hippocampal synaptic function in health and disease. Philos

Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 369:201301552014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Sánchez JC, Ospina JP and González MI:

Association between leptin and delirium in elderly inpatients.

Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 9:659–666. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Shukla V, Skuntz S and Pant HC:

Deregulated Cdk5 activity is involved in inducing Alzheimer's

disease. Arch Med Res. 43:655–662. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Chen WL, Kang CH, Wang SG and Lee HM:

α-Lipoic acid regulates lipid metabolism through induction of

sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) and activation of AMP-activated protein kinase.

Diabetologia. 55:1824–1835. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Higgins GM and Anderson RM: Experimental

pathology of the liver. I. Restoration of the liver of the white

rat following partial surgical removal. Arch Pathol. 12:186–202.

1931.

|

|

19

|

Ku S, Yan F, Wang Y, Sun Y, Yang N and Ye

L: The blood-brain barrier penetration and distribution of

PEGylated fluorescein-doped magnetic silica nanoparticles in rat

brain. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 394:871–876. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Wilkaniec A, Gąssowska-Dobrowolska M,

Strawski M, Adamczyk A and Czapski GA: Inhibition of

cyclin-dependent kinase 5 affects early neuroinflammatory

signalling in murine model of amyloid beta toxicity. J

Neuroinflammation. 15:12018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|