Introduction

Ultrasound-guided intervention has many benefits.

The visually clear real-time pathway guarantees negligible

radiation hazard, secures procedural safety for aspiration, biopsy,

and ablation in the treatment of multiple organ diseases, enhances

multi-dimensional capability, provides convenience, decreases

procedure time, and minimizes cost (1,2). Also,

the pre-operative sampling of tumor mass is suggested to confirm

the presence of cancer and ascertain morphological subtype before

neo-adjuvant chemotherapy may lead to the potential diagnostic

misinterpretation of tumor cells and difficulties in detecting

residual tumor after neoadjuvant chemotherapy of bulky malignant

tissues (3).

Ultrasound-guided intervention has technically

evolved with clinical procedures conducted at the abdomen, thorax

and urogenital system (4).

Transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS)-guided biopsy is safe and effective

in the diagnosis of pelvic lesions (5–15).

TVUS-guided gun biopsy of the uterus and ovaries in

the office setting histologically confirmed 19 of the 22 (86.4%)

preliminary equivocal ultrasound diagnosis of adenomyosis,

leiomyoma and benign ovarian mass (5). The diagnostic accuracy of TVUS using

histopathology as a gold standard in identifying endometrial

hyperplasia among 263 perimenopausal women presenting with abnormal

uterine bleeding was found to be 75.6% (6).

TVUS has a high negative predictive value (99.1%)

for an endometrial thickness of 10.8 mm in the evaluation of 100

women with post-menopausal bleeding (7). The TVUS biopsy diagnosis of peritoneal

carcinomatosis and recurrent pelvic malignancy was validated in a

cohort of 50/54 (93%) women by comparison with the histopathologic

specimen or clinical course and outcome (8). TVUS-guided core needle biopsy

adequately obtained tumor samples from 200 women with

abdominopelvic or pelvic masses with 190 of 200 (95.0%) verified

before treatment (9). Of the 200, 97

(48.5%) were inoperable tumors, 13 (6.5%) were metastatic, 45

(22.5%) were recurrent and 45 (22.5%) were rare tumors (9). In 55 women with pelvic masses detected

on computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

before the biopsy, 46 (84%) of the pelvic samples from TVUS core

biopsy were confirmed to be either malignant or benign, and 5 (9%)

were inflammatory lesions showing an overall diagnostic accuracy of

51/55 (93%) (10). Of the 48 women

diagnosed by ultrasound alone as having adenomyosis, 37 (77%) were

histologically confirmed as having adenomyosis after TVUS-guided

biopsy (11). Samples obtained by

TVUS guided uterine core biopsy from 80 cases of pre-menopausal

women scheduled for hysterectomy proved to be useful in the

investigation of early pathogenesis of adenomyosis (12).

Transrectal ultrasound (TRUS)-guided core biopsy

confirmed recurrent carcinoma of the uterine cervix in 16/17 (94%)

of women with non-diagnostic vaginal cytology and transvaginal

punch biopsy (13). TRUS-guided

biopsy revealed recurrent pelvic malignancy in 5/8 (62%) in women

presenting with abdomino-pelvic and back pain (14). TRUS examination was assessed to have

high diagnostic power for polycystic ovary syndrome among 183

Korean women aged 21–32 years (15).

Of the 11 studies that reported safety and efficacy,

only one study reported vaginal bleeding, 10/55 (18%) and gross

hematuria, 2/55 (4%) as TVUS procedure-related complications

(10). There was no reported

complication with TRUS-guided biopsy in any of the reports.

This study aimed to determine the accuracy and

safety of transvaginal and transrectal core needle biopsy of pelvic

cavity masses under ultrasound guidance. The authors undertook this

study since there is scant literature on the histological findings

from biopsies taken directly from the pelvic cavity and from pelvic

floor lesions.

Materials and methods

Subjects

We randomly obtained medical records of female

patients. A consecutive series of 40 patients with the diagnosis of

pelvic or pelvic floor masses between July 2015 and August 2017 at

the Department of Ultrasound of the First Affiliated Hospital of

Medical University of Anhui (Hefei, China) were considered eligible

and chosen for satisfying the inclusion criteria. Inclusion

criteria were as follows: i) Mass was detected by MRI or positron

emission tomography (PET)/CT one month prior to biopsy, ii) primary

origin was undetermined; iii) mass was visible by either

transvaginal or transrectal ultrasound technique, iv) mass was in

proximity, v) accessible to either TVUS- or TRUS-guided biopsy for

tissue sampling, and vi) histological confirmation is needed for

further patient management. Exclusion criteria were as follows: i)

No ultrasound-guided needle path, ii) poor coagulation function,

iii) severe infection, and iv) severe heart and lung

insufficiency.

Clinical laboratory indicators of patient status and

risk of complication were evaluated. The laboratory indicators were

complete blood count, prothrombin time, international normalized

ratio, activated partial thromboplastin time. We retrospectively

analyzed extracted clinicopathologic data.

Informed consent and ethics

approval

Before the procedure, patients were informed of the

risk of complications and potential damage to adjacent structures

along the path of the needle. Consent to proceed with the biopsy

was obtained before the procedure.

Before inclusion into the retrospective study,

patients or legally authorized representatives of subjects were

contacted. All the participants gave their informed consent for

inclusion and use of patient information. The protocol of the study

was approved by the Medical University of Anhui Institutional

Review Board. The IRB approval project identification code is

AF/SC-08/02.0. The study was conducted as per the Declaration of

Helsinki.

Instrument and biopsy procedure

None of the included patients had contraindications

for biopsy. Every biopsy was performed by one of two experienced

physicians (CG, LW) who had worked at least five years at the

interventional ultrasound department using US instrument (Logiq E9;

GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA). TVUS- and TRUS-guided biopsies

were performed in the lithotomy position with empty bladder after

sterilization of the vagina and anus (16). The procedure utilized a reusable

automatic biopsy gun (Bard Biopsy, Tempe, AZ, USA) compatible with

an 18 gauge 15 cm tru-cut needle. The needle was inserted parallel

to the transvaginal US probe and was directed to the lesion with an

attached needle guide.

Local anesthesia and conscious sedation were not

used. The biopsy needle with ultrasonic dynamic monitoring led the

passage avoiding bowel, blood vessels, and bladder. The

morphological characteristics of the mass, size, location,

relationship with the adjacent tissues, and proximity to the vagina

or rectum were observed before puncture. Upon reaching the lesion

edge and gaining a penetration depth of >2.0 cm with strong echo

lesions, biopsy specimens were drawn from different directions

(17). All the specimens obtained

were immediately placed on a sterile filter paper and fixed in 10%

formaldehyde solution (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA, Darmstadt,

Germany). Sections and slides from paraffin-embedded tissue blocks

as samples were stained with hematoxylin-eosin.

After the transvaginal procedures, three sterilized

cotton balls were immediately tucked into the biopsy sites for

hemostasis. Bleeding and other possible complications were checked

after the cotton balls were taken out after 30 min. Patients were

observed around 30 min to 1 h with frequent vital signs monitoring

in a dedicated area. Safety of the procedure was concluded if there

were no or minor complications. If without discomfort or

complications, patients were returned to the ward or sent home. The

procedure and diagnostic criteria of TRUS-guided biopsy were

similar to that of TVUS (18).

Radiologic, pathologic, and clinical

data analyses

All archived CT, MRI, and ultrasonography (US)

images from the picture archiving and communication system

(PathSpeed, GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI, USA) were re-evaluated.

Radiologists were aware of the history of the patient illness but

blinded to all other clinical information. Two radiologists

independently evaluated the pelvic lesions based on the: i) lesion

size, ii) lesion nature (e.g., solid or cystic) (19), and iii) lesion site. The biopsy core

number was counted from images, and the biopsy distance was

determined from the standard reports. The biopsy distance was

defined by the measured mean length of the biopsy needle seen on US

images. Disagreements of the evaluation of two radiologists were

resolved by consensus. If no agreement was reached, a third

evaluator was consulted for final consensus.

An experienced pathologist evaluated the histology

of the specimen. The pathologist was aware of the history of the

patient illness but blinded to all other clinical information

including the imaging results (20).

The step detects the presence or absence of malignancy thereby

detecting or excluding the diagnosis (21). Possible complications based on the

patients' medical records were evaluated using the Clavien-Dindo

classification (22).

Results

Of the 40 female patients included in the study, 39

had TVUS, and 1 had TRUS-guided biopsy. The mean age was 54 years

(range, 46–69 years). All laboratory results were within the

acceptable normal range of coagulation parameters (Table I). There were no complications

identified.

| Table I.Normal values of coagulation in

patients undergoing TVUS- and TRUS-guided aspiration biopsy. |

Table I.

Normal values of coagulation in

patients undergoing TVUS- and TRUS-guided aspiration biopsy.

| Hematologic test | Normal range of

values (reference) | Cut-off |

|---|

| Activated partial

thromboplastin time | 28.0–42.0 | 45 |

| INR | 0.85–1.15 | 1.6 |

| Platelets,

109/l | 125–350 | 50 |

| Prothrombin time | 11.0–16.0 | 18 |

The median lesion size was 5.5 cm (range, 1–15 cm).

Thirty-four of the lesions were solid while six were cystic. The

mean distance of the biopsy was 2.4 cm (range, 1.4–5.6 cm). The

median number of biopsy cores obtained from each patient was 4.0

(range, 2–7 cores). The specimens (Table II) were obtained from pelvic cavity

and pelvic floor in 18 cases (45%), the vaginal stump in 6 cases

(15%), the cervix in 2 cases (5%) and the vaginal fornix in 13

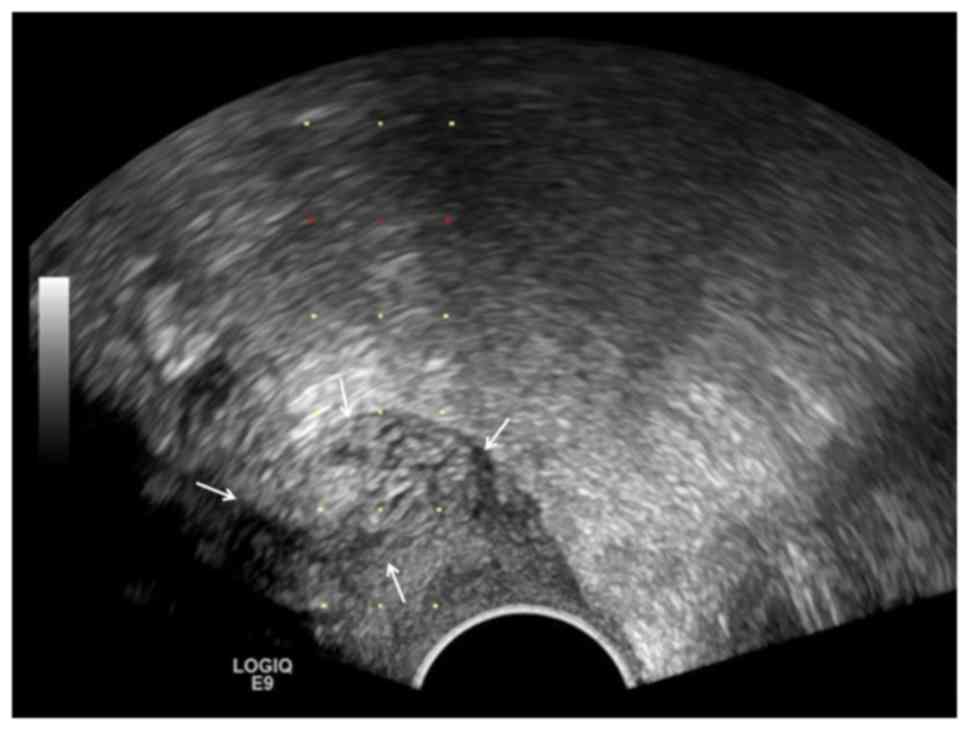

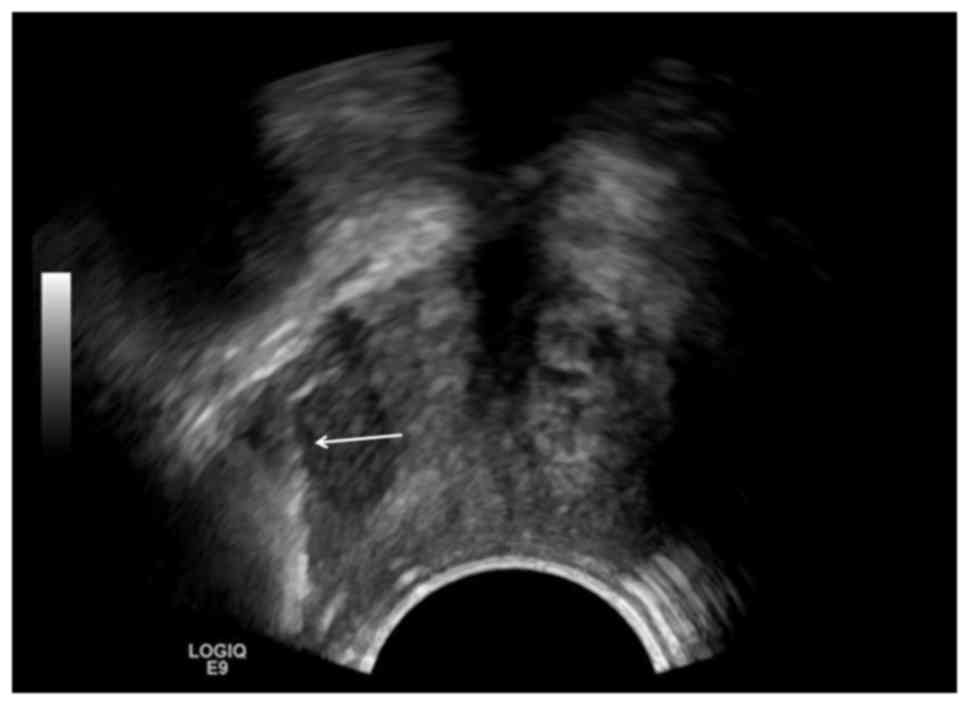

cases (32.5%). Representative cases are shown in Figs. 1–4.

| Table II.Malignancy proven lesions from

transvaginal ultrasound-guided aspiration biopsies. |

Table II.

Malignancy proven lesions from

transvaginal ultrasound-guided aspiration biopsies.

| Patient | Age (years) | MRI and PET/CT

findings at sites | Pathomorphological

findings | Diagnosis |

|---|

| 1 | 84 | Pelvic cystic, solid

mass | Grayish white, poorly

differentiated cancer | Ovarian cancer |

| 2 | 67 | Vaginal stump

hypoechoic | Low-grade

adenocarcinoma | Ovarian cancer |

| 3 | 60 | Bottom of the pelvic

floor | Grayish white, poorly

differentiated adenocarcinoma | Ovarian cancer |

| 4 | 52 | Low echo above the

vaginal stump | Grayish white, poorly

differentiated squamous cell carcinoma | Cervical cancer |

| 5 | 46 | Cervical anterior lip

hypoechoic | Medium-differentiated

adenocarcinoma, metastatic carcinoma of the upper digestive source

may be large | Metastatic

adenocarcinoma, upper gastrointestinal |

| 6 | 68 | Pelvic floor

cervix | Gray-white, poorly

differentiated urothelial carcinoma may be large | Cervical cancer |

| 7 | 46 | Low echo above the

vaginal stump | Gray-white, poorly

differentiated cancer, combined with a history of breast cancer

metastasis may be large | Metastatic poorly

differentiated, breast |

| 8 | 54 | Right ovarian | Grayish white,

spindle cell lesion, solid lesion | Ovarian cancer no

excluding sex stromal tumor |

| 9 | 47 | Low echo of the left

uterus | 3 grayish white,

high-grade serous carcinoma, source of female reproductive

system | Ovarian cancer |

| 10 | 62 | Hypoechoic lesion on

the left side of the posterior vagina | 3 grayish white,

ovarian serous carcinoma metastasis | Ovarian cancer |

| 11 | 46 | Cervical anterior and

posterior lip hypoechoic, cervix 1, cervix 2, anterior vaginal

wall | High-grade squamous

intraepithelial neoplasia CIN3, suspicious microinvasive, chronic

inflammation of vaginal lesions | Cervical cancer |

| 12a | 47 | Cervical, ovary | 1 anterior lip of the

cervix, smooth muscle; 1 posterior lip of the cervix,

adenocarcinoma; 2 ovarian cancer, adenocarcinoma; | Straight B junction

tumor ovarian metastasis |

| 14 | 50 | Hypoepitic lesions

above the vagina | Grayish white 3,

leiomyoma | Uterine fibroids |

| 15 | 67 | Vaginal stump cystic,

solid mass | Poorly differentiated

cancer | Ovarian cancer |

| 16 | 60 | Right ovarian giant

cystic | Medium differentiated

adenocarcinoma | Metastatic non-small

cell lung cancer, adenocarcinoma |

| 17 | 47 | Vaginal stump | Poorly differentiated

cancer | Ovarian cancer |

| 18 | 52 | Pelvic mass | Poorly differentiated

cancer | Ovarian cancer |

| 19 | 62 | Cervical

hypoechoic | Squamous cell

carcinoma | Cervical cancer |

| 20 | 61 | Double ovarian solid

mass | Metastatic poorly

differentiated adenocarcinoma | Metastatic non-small

cell lung cancer, adenocarcinoma |

| 21 | 56 | Vaginal stump | Poorly differentiated

cancer | Cervical cancer |

| 22 | 61 | Vaginal wall

stump | Poorly differentiated

cancer | Cervical cancer |

| 23 | 48 | Left attachment

pocket solid mass | Serous carcinoma | Ovarian cancer |

| 24 | 71 | Vaginal stump | Endometriosis | Endometriosis |

| 25 | 45 | Left ovary

hypoechoic | Spindle cell

tumor | Sex cord stromal

tumor |

| 26 | 52 | Low echo of the

anterior wall of the vagina | Leiomyoma | Vaginal

leiomyoma |

| 27 | 43 | Pelvic cystic mixed

echo | Serous

carcinoma | Ovarian cancer |

| 28a | 54 | Left genital

hypoechoic lesion | Adenoid cystic

carcinoma | Ovarian cancer |

| 29 | 67 | Vaginal stump | Adenocarcinoma | Endometrial

cancer |

| 30 | 56 | Left ovarian solid

part and posterior lip lesion | Poorly

differentiated cancer | Ovarian cancer |

| 31 | 52 | Posterior wall of

the lower vagina | Leiomyoma | Uterine

fibroids |

| 32 | 64 | Above the vaginal

stump | Endometrial stromal

sarcoma | Uterine cancer |

| 33 | 70 | Cervical

hypoechoic | Inflammatory | Inflammatory cells,

cervix |

| 34 | 59 | Uterine rectal

fossa lesion | Serous

carcinoma | Ovarian cancer |

| 35 | 42 | Left echo low echo

nodule | Metastatic

cancer | Endometrial

cancer |

| 36 | 53 | Uterine rectal

fossa lesion | Serous

carcinoma | Ovarian cancer |

| 37 | 46 | Subcutaneous

hypoechoic | Adenoid cystic

carcinoma infiltration | Vaginal cancer |

| 38 | 42 | Pelvic mass | Low-grade

adenocarcinoma | Cervical

cancer |

| 39 | 41 | Vaginal stump | Squamous cell

carcinoma | Cervical

cancer |

| 40 | 54 | Uterine rectal

fossa | Left ovarian

granuloma | Ovarian cancer |

All the specimens were adequate for histologic

evaluation and diagnosis with 72% (28/39) being identified as

primary and 13% (5/39) as metastatic malignancy. There was one

diagnosed case of rectal cancer with a post-operative specimen from

the posterior wall of the anal canal obtained by TRUS-guided biopsy

(2.5%).

Discussion

A retrospective analysis was performed in our center

to determine whether TVUS- and TRUS-guided aspiration biopsy allows

the detection of a malignant pathology in the pelvic/pelvic floor.

The study shows detection in almost all suspicious clinical cases

by MRI or PET/CT consistent with a more than 90% adequacy and

accuracy of other studies (8–10). An

experienced pathologist provided the expertise that has optimized

the use of aspiration biopsy.

TVUS- or TRUS-guided aspiration biopsy has several

advantages. The biopsy is technically easy and does need

anesthesia. Either of the two techniques can be used as a

first-line investigation in the evaluation of women with pelvic or

pelvic floor masses (6,9). The biopsy can be supplemented with

procedures such as laparoscopy for lesions involving ovary and

cervix as experienced in the hospital. In addition to the

traditional benefits of ultrasound-guided biopsy (1,2), seeding

by malignant cells seems low risk (9). Also, it is not known whether the risk

of infection is high with the transrectal or transvaginal

approaches. Antibiotic prophylaxis is well-established in

transrectal biopsy of the prostate (23). However, whether infection and

subsequent antibiotic prophylaxis are necessary for TVUS-guided

biopsy remains to be observed.

The present study has several limitations. As a

retrospective analysis using medical chart reviews, data inputted

from medical records were not sufficient to determine diagnostic

performance. Analysis to provide valid and reliable diagnostic

performances (sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value,

negative predictive value, accuracy) requires the identification of

a set of variables to provide the best prediction. Missing data

precluded the detection of increasing diagnostic certainty from

imaging to histopathology. Detection or exclusion of malignancy

using test-result based sampling or case-referent sampling is ideal

(21).

Second, the diagnostic test is almost always not

applied in isolation but in combination (21). Interacting variables (relevant

clinical variables, tumor markers, CT/MRI, clinical stage of

cancer) increase sample size and may not be easy to be obtained. To

conduct this kind of study, we may have to collaborate with other

hospital centers. Finally, there were case scenarios in the

management of cancer patients that were not encountered but are

potentially significant: i) A previously diagnosed benign tumor

turning out to be malignant, ii) distinguishing either a recurrence

or post-treatment fibrosis, iii) whether TRUS complements TVUS, and

iv) follow-up stage of cancer management.

Despite the limitations, the validity of the

pathomorphologic findings and final diagnosis were not compromised

because the pathologist was blinded to all other clinical

information including the imaging results.

Ultrasound-guided transvaginal or transurethral

biopsy seems to be a reliable and safe procedure for

histopathological evaluation of the pelvic cavity and pelvic mass

lesions. Prospective studies of adequate sample size are needed to

evaluate the usefulness of the procedures across various clinical

case scenarios.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Scientific

Foundation Committee of China (No. 81801723) and the Clinical

Research Support Foundation of the Chinese PLA General Hospital

(No. 2017FC-CXYY-3005).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current

study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

CG. participated in the analysis and interpretation

of data, and drafted the manuscript. XL made substantial

contributions to the conception and design of the study. CG, LW and

CZ carried out the study and collected the data. XL contributed to

revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual

content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

This retrospective medical record review was

approved by the Institutional Review Board/Clinical Medical

Research Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui

Medical University (Approval no: AF/SC-08/02.0)

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Copelan A, Scola D, Roy A and Nghiem HV:

The myriad advantages of ultrasonography in image-guided

interventions. Ultrasound Q. 32:247–257. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Park BK: Ultrasound-guided genitourinary

interventions: Principles and techniques. Ultrasonography.

36:336–348. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

McCluggage WG, Lyness RW, Atkinson RJ,

Dobbs SP, Harley I, McClelland HR and Price JH: Morphological

effects of chemotherapy on ovarian carcinoma. J Clin Pathol.

55:27–31. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Dietrich CF and Numberg E: A Practical

Guide and Atlas. Intervention Ultrasound. 1st. Thieme; Stuttgart,

Germany: pp. 4042014

|

|

5

|

Walker J and Jones K: Transvaginal

ultrasound guided biopsies in the diagnosis of pelvic lesions.

Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. 12:241–244. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Nazim F, Hayat Z, Hannan A, Ikram U and

Nazim K: Role of transvaginal ultrasound in identifying endometrial

hyperplasia. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 25:100–102.

2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Menon S and Sreekumari I: Role of

transvaginal ultrasound in the assessment of endometrial pathology

in patients with post-menopausal bleeding. Int J Reprod Contracept

Obstet Gynecol. 6:1376–1380. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Dadayal G, Weston M, Young A, Graham JL,

Mehta K, Wilkinson N and Spencer JA: Transvaginal ultrasound

(TVUS)-guided biopsy is safe and effective in diagnosing peritoneal

carcinomatosis and recurrent pelvic malignancy. Clin Radiol.

71:1184–1192. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Lin SY, Xiong YH, Yun M, Liu LZ, Zheng W,

Lin X, Pei XQ and Li AH: Transvaginal ultrasound-guided core needle

biopsy of pelvic masses. J Ultrasound Med. 37:453–461. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Park JJ, Kim CK and Park BK:

Ultrasound-guided transvaginal core biopsy of pelvic masses:

Feasibility, safety, and short-term follow-up. AJR Am J Roentgenol.

206:877–882. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Elkattan E, Omran E and Al Inany H: The

accuracy of transvaginal ultrasound and uterine artery Doppler in

the prediction of adenomyosis. Middle East Fertil Soc J. 15:73–78.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Tellum T, Qvigstad E, Skovholt EK and

Lieng M: In vivo adenomyosis tissue sampling using a transvaginal

ultrasound-guided core biopsy technique for research purposes:

Safety, feasibility, and effectiveness. J Minim Invasive Gynecol.

Feb 8–2019.(Epub ahead of print). View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Roy D, Kulkarni A, Kulkarni S, Thakur MH,

Maheshwari A and Tongaonkar HB: Transrectal ultrasound-guided

biopsy of recurrent cervical carcinoma. Br J Radiol. 81:902–906.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Giede C, Toi A, Chapman W and Rosen B: The

use of transrectal ultrasound to biopsy pelvic masses in women.

Gynecol Oncol. 95:552–556. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Lee DE, Park SY, Lee SR, Jeong K and Chung

HW: Diagnostic usefulness of transrectal ultrasound compared with

transvaginal ultrasound assessment in young Korean women with

polycystic ovary syndrome. J Menopausal Med. 21:149–154. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Plett SK, Poder L, Brooks RA and Morgan

TA: Transvaginal ultrasound-guided biopsy of deep pelvic masses:

How we do it. J Ultrasound Med. 35:1113–1122. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Zikan M, Fischerova D, Pinkavova I, Dundr

P and Cibula D: Ultrasound-guided tru-cut biopsy of abdominal and

pelvic tumors in gynecology. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 36:767–772.

2010. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Alborzi S, Rasekhi A, Shomali Z, Madadi G,

Alborzi M, Kazemi M and Hosseini Nohandani A: Diagnostic accuracy

of magnetic resonance imaging, transvaginal, and transrectal

ultrasonography in deep infiltrating endometriosis. Medicine

(Baltimore). 97:e95362018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Fischerova D: Ultrasound scanning of the

pelvis and abdomen for staging of gynecological tumors: A review.

Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 38:246–266. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

de Groot JA, Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB,

Rutjes AW, Dendukuri N, Janssen KJ and Moons KG: Verification

problems in diagnostic accuracy studies: Consequences and

solutions. BMJ 343 (aug02 3). d47702011.

|

|

21

|

Knottnerus JA, van Weel C and W Muris J:

Evaluation of diagnostic procedures. Evidence base of clinical

diagnosis. 324:(2nd). Knottnerus JA: BMJ Books. (London). 477–480.

2002.

|

|

22

|

Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML,

Vauthey JN, Dindo D, Schulick RD, de Santibañes E, Pekolj J,

Slankamenac K, Bassi C, et al: The Clavien-Dindo classification of

surgical complications: Five-year experience. Ann Surg.

250:187–196. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Noreikaite J, Jones P, Fitzpatrick J,

Amitharaj R, Pietropaolo A, Vasdev N, Chadwick D, Somani BK and Rai

BP: Fosfomycin vs. quinolone-based antibiotic prophylaxis for

transrectal ultrasound-guided biopsy of the prostate: A systematic

review and meta-analysis. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis.

21:153–160. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|