Introduction

Persistent and progressive liver injury results in

the inability of the liver to regenerate and leads to liver

fibrosis (1). Liver fibrosis is a

wound healing response that is closely associated with hepatic

stellate cells (HSCs) and Kupffer cells (2). The activation and accumulation of a

large number of HSCs is a pivotal step in the formation and

progression of liver fibrosis (3).

Initiation and perpetuation are two stages that constitute the

activation of HSCs (4). Persistent

activation of HSCs can contribute to cellular events, including

extracellular matrix degradation and cytokine release, which result

in the production and accumulation of fibrotic extracellular matrix

components, including α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) and collagen

type I α1 (COL1A1) (5).

Additionally, HSCs can synthesize and secrete TIMP metallopeptidase

inhibitor 1 (TIMP1), which is a powerful inhibitor of enzymes that

degrade matrix molecules and serves a critical role in fibrosis

(6). Overall, liver fibrosis has

become an obstacle in clinical trials or during treatment of

patients with chronic liver diseases (7). Therefore, there is an urgent need to

identify novel and effective treatment strategies for this

disease.

Interleukin (IL)-22 was originally identified as an

IL-10-related T cell-derived inducible factor (8). IL-22 is an actively secreted protein

of 146 amino acids, which belongs to the IL-10 family of cytokines

(9,10). Despite the differences noted in

primary sequences among IL-10 members, they share a common gene

structure containing six helices (11). IL-22 expression is downregulated in

the serum of mice and in diabetic nephropathy patients (12). By binding to the IL-22 receptor

subunit α-1 (IL-22RA1) and IL-10R2, IL-22 exerts protective effects

on hepatocytes (13). It has been

shown that the binding of IL-22 to IL-22RA1 can induce senescence

of HSCs and ameliorate liver fibrosis (14). However, the activation of several

signaling pathways, such as STAT3, SOCS3, p53 and Notch, induced by

IL-22 inhibits the progression of liver damage (15).

Oxidative stress serves a crucial role in inducing

HSC activation and fibrogenic potential (16). Superoxide dismutase (SOD), one of

the most important protective enzymes, provides the first

antioxidant defense system in various organs and tissues, including

the liver (17). Glutathione (GSH)

is a key reactive oxygen species scavenger to protect liver cells

from oxidative stress (18). SOD

and GSH serve an important role in the antioxidant defense system,

while malondialdehyde (MDA) is considered to be the main marker of

lipid peroxidation in tissues (19). Inflammation serves a critical role

in the progression of liver injury and fibrosis. NOD-like receptor

protein 3 (NLRP3) is a well-established inflammasome that consists

of apoptosis-associated speck-like protein and the effector

molecule pro-caspase-1(20). Recent

studies have confirmed the role of NLRP3 in a variety of liver

diseases, such as alcoholic and non-alcoholic fatty liver diseases

and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (21,22).

Inhibition of the NLRP3 inflammasome can alleviate renal injury and

fibrosis (23). NLRP3 is aberrantly

activated in vivo and in vitro following exposure to

aristolochic acid, and inhibition of NLRP3 ameliorates renal

fibrosis and renal failure (24).

However, whether IL-22 ameliorates liver fibrosis by directly

inhibiting the activation of NLRP3 has not been previously

investigated.

In the present study, the role of IL-22 was

investigated in transforming growth factor β (TGF-β)-induced HSCs.

Whether IL-22 exerted its effects on liver fibrosis via the

regulation of NLRP3 inflammasome signaling was also explored. The

current study may guide the future exploration of the pathogenesis

of liver fibrosis.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and treatment

HSCs were purchased from the American Type Culture

Collection and Nigericin (cat. no. N7143) was purchased from

Sigma-Aldrich (Merck KGaA). HSCs were cultured in DMEM supplemented

with 10% FBS (both Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), 100 U/ml

penicillin and 100 mg/ml streptomycin in a PBS buffer (R&D

Systems, Inc.) at 37˚C in an incubator with 95% air/5%

CO2. The cells were treated with 5 ng/ml TGF-β

(Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) at 37˚C for 24 h and subsequently

cultured in the presence of 250, 500, 750 and 1,000 pg/ml IL-22

(Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) for 48 h at 37˚C (25,26).

Finally, the cells were treated with Nigericin (40 µM) for 30 min

at 37˚C to activate NLRP3 for subsequent experiments (27).

Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay

The CCK-8 assay was conducted for the determination

of cell viability. Briefly, HSCs (3x104 cells/well) were

inoculated into a 96-well plate at 37˚C. At 48 h after IL-22

treatment, 10 µl CCK-8 reagent (Dojindo Molecular Technologies,

Inc.) was added to each well and incubated for 3 h. The absorbance

at 450 nm was read using a microplate reader (Bio-Rad Laboratories,

Inc.). Three replicates were conducted for each sample.

Apoptosis assay

Apoptosis was evaluated via flow cytometry. HSCs

were collected and then re-suspended in 1X binding buffer to a

concentration of 1x104 cells/well. An Annexin V-FITC

Staining Cell Apoptosis Detection kit (Nanjing KeyGen Biotech Co.,

Ltd.) was employed to determine apoptosis in accordance with the

manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, cells were stained with Annexin

V-FITC and PI, and incubated in the dark for 15 min at 37˚C. Cell

apoptosis of each sample was assessed by flow cytometry (BD Accuri™

C6; BD Biosciences). Apoptosis was analyzed using FlowJo software

(version 7.6.3; FlowJo LLC).

Detection of oxidative stress

The contents of MDA and GSH, as well as the activity

of SOD, were respectively detected using the MDA assay kit (cat.

no. A003-4-1), GSH assay kit (cat. no. A006-2-1) and SOD assay kit

(cat. no. A001-3-2; all from Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering

Institute) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions.

Reverse transcription-quantitative

polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was isolated from cells using

TRIzol® reagent (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA). cDNA was

synthesized using a Sensiscript RT kit (Qiagen GmbH) following

manufacturer's recommendations. According to the manufacturer's

recommendations, PCR assays were conducted using

SYBR-Green® Realtime PCR Master Mix and Premix Ex Taq

(Takara Bio., Inc.) on ViiA™ 7 Real-Time PCR System (Applied

Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The following

thermocycling conditions were used: 5 min at 95˚C, followed by 35

cycles at 95˚C for 15 sec, 40 sec at 55˚C and 72˚C for 1 min.

Relative quantification of gene expression was performed using the

2−ΔΔCq method (28). The

relative gene expression levels were normalized to those of GAPDH.

Three independent experiments were conducted for each target gene.

The sequences of the gene-specific primers used in the present

study were as follows: α-SMA forward, 5'-TCCAGAGTC

CAGCACAATACCAG-3' and reverse, 5'-AATGACCCAGAT TATGTTTGAGACC-3';

COL1A1 forward, 5'-TCAGGGGCG AAGGCAACAGT-3' and reverse,

5'-TTGGGATGGAGG GAGTTTACACGA-3'; TIMP1 forward, 5'-ACCACCTTA

TACCAGCGTTATGA-3' and reverse, 5'-GGTGTAGACGAA CCGGATGTC-3'; GAPDH

forward, 5'-CTCACCGGATGC ACCAATGTT-3' and reverse,

5'-CGCGTTGCTCACAAT GTTCAT-3'.

Western blot analysis

HSCs were lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation (RIPA)

lysis buffer (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) and the

concentrations of the proteins were measured using a BCA protein

assay (Shanghai Yeasen Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). Proteins (40

µg/lane) were separated via 10% SDS-PAGE and were transferred to

PVDF membranes, which were then blocked with 5% skimmed milk for 1

h at room temperature. Subsequently, the membranes were incubated

at 4˚C overnight with primary antibodies (all 1:1,000) against

NLRP3 (cat. no. 15101S), IL-1β (cat. no. 12703S), caspase-1 (cat.

no. 3866T), α-SMA (cat. no. 19245T), COL1A1 (cat. no. 72026T),

TIMP1 (cat. no. 8946S) and GAPDH (cat. no. 5174T; all from Cell

Signaling Technology, Inc.). The membranes were washed three times

with TBS-0.2% Tween 20 before incubation with goat anti-rabbit

HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (1:3,000; cat. no. 7074S; Cell

Signaling Technology, Inc.) for 1 h at room temperature. The

expression levels of the targeted proteins were determined using a

Bio-Rad ChemiDoc MP imaging system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.).

The bands were detected using an enhanced chemiluminescence reagent

(EMD Millipore). The grayscale values of the membranes were

semi-quantified using ImageJ software (version 1.52r; National

Institutes of Health). GAPDH was used as an internal control.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism version 6.0

(GraphPad Software, Inc.). Data were expressed as the mean ± SD.

All experiments were performed three times. Comparisons between two

groups were conducted by unpaired Student's t-test, while

comparisons among multiple groups were performed by one-way ANOVA

followed by Turkey's post-hoc test. P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

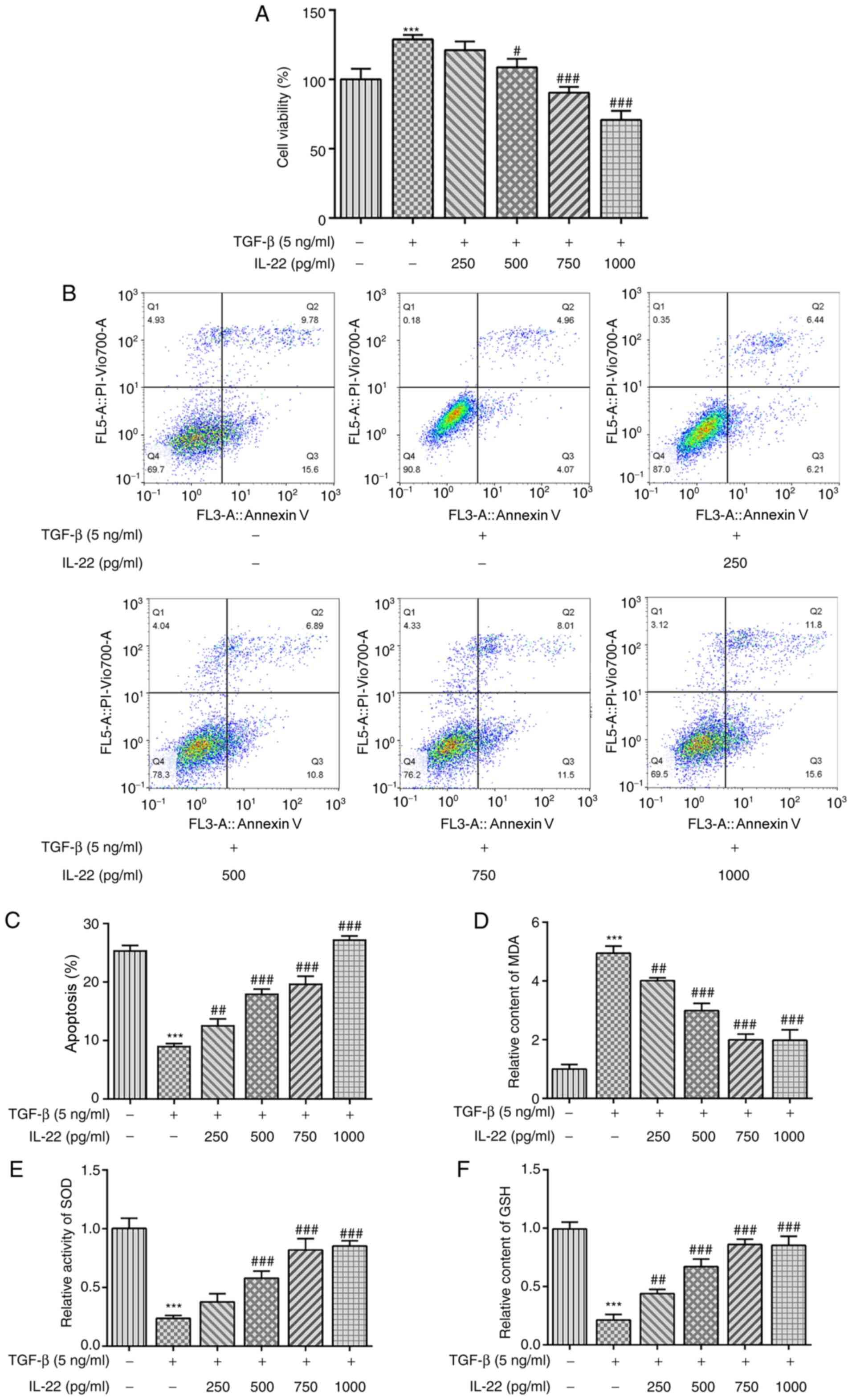

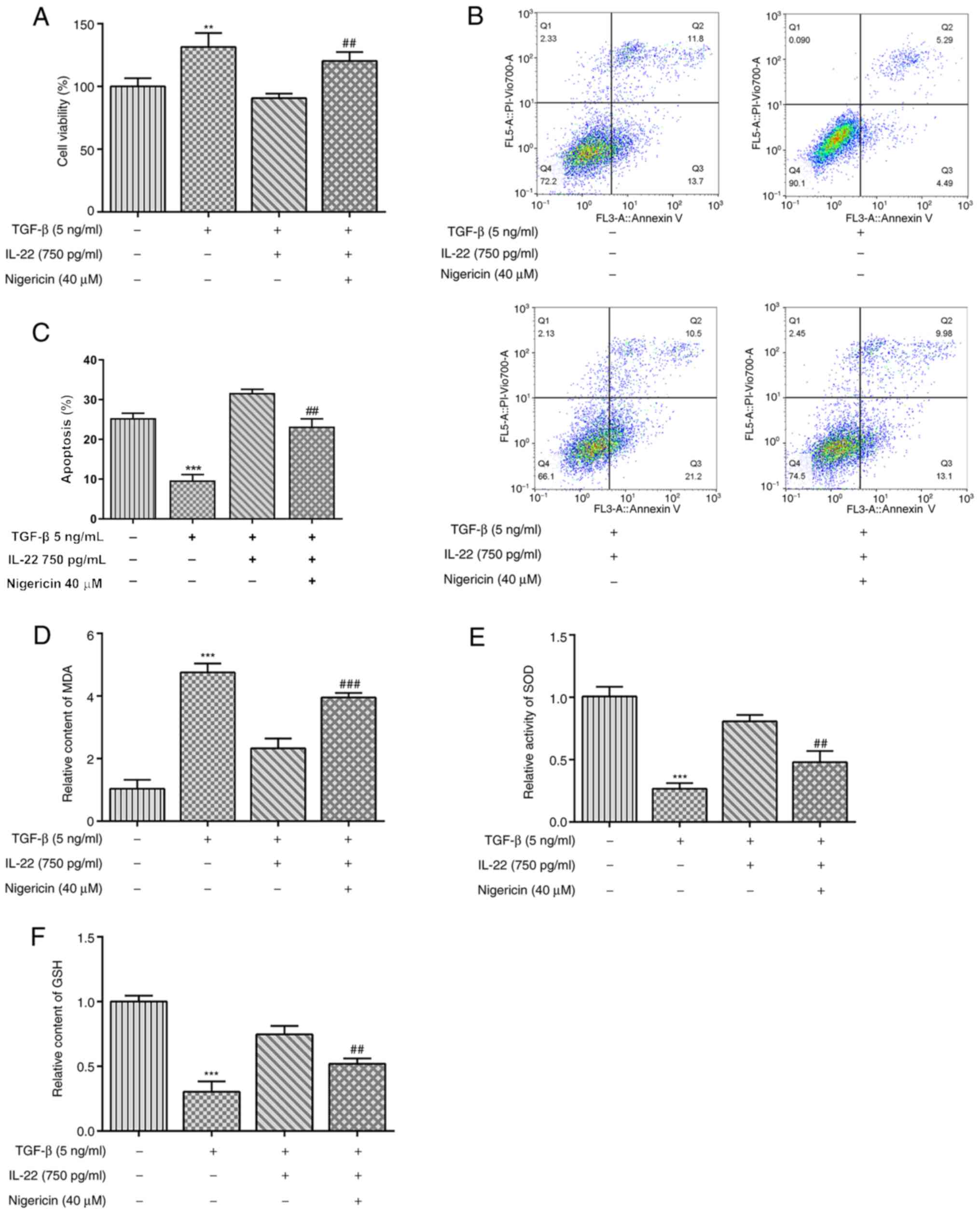

IL-22 attenuates HSC viability and

oxidative stress activated by TGF-β

Following incubation of HSCs with TGF-β, their

viability was significantly increased, while concomitant IL-22

treatment led to significant decreases in HSC viability in a

dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1A). As

shown in Fig. 1B and C, TGF-β treatment significantly inhibited

the apoptosis of HSCs compared with the untreated group. By

contrast, IL-22 significantly increased TGF-β-induced apoptosis in

a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1B

and C). Subsequently, factors

associated with oxidative stress were measured using commercially

available kits. As shown in Fig.

1D, TGF-β stimulation caused a significant increase in the

relative content of MDA, whereas increasing concentrations of IL-22

led to a gradual decrease in MDA levels. Conversely, the levels of

SOD and GSH were significantly inhibited following TGF-β treatment,

whereas IL-22 restored their levels in a dose-dependent manner

(Fig. 1E and F). Overall, these findings revealed that

IL-22 inhibited viability and oxidative stress in HSCs induced by

TGF-β.

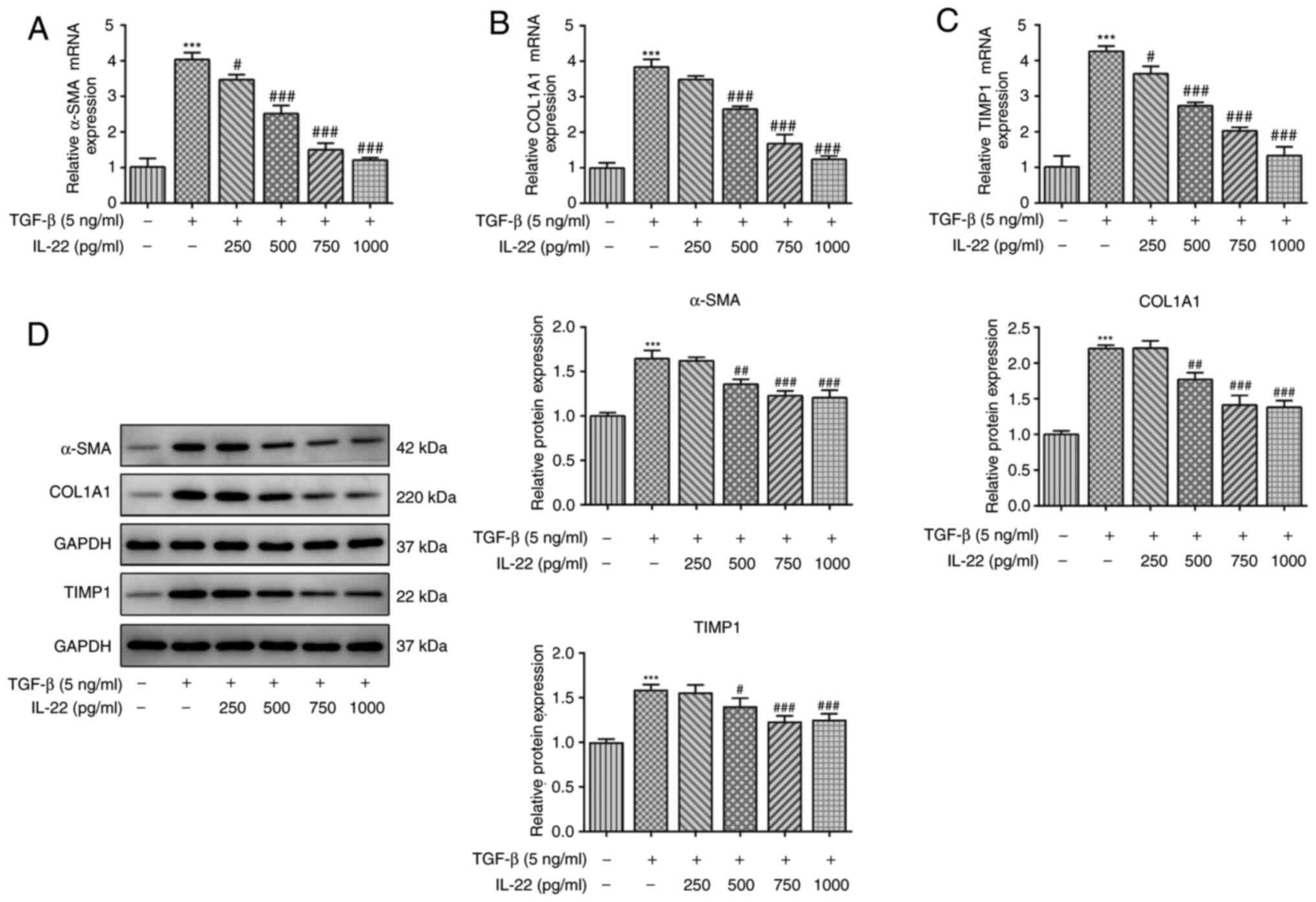

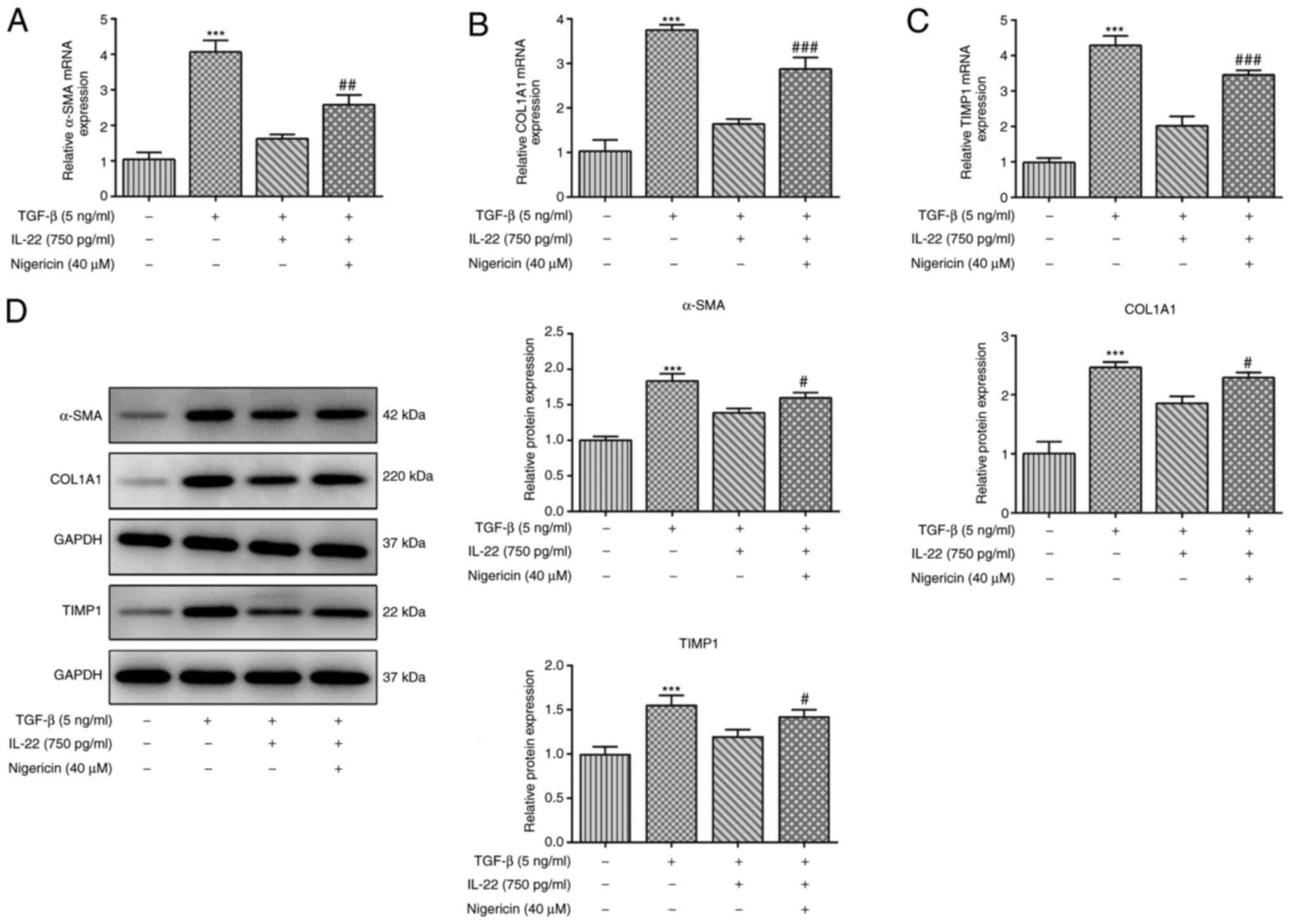

IL-22 alleviates fibrosis of HSCs

activated by TGF-β

Subsequently, the ability of IL-22 to inhibit HSC

fibrosis activated by TGF-β was assessed. To confirm this

hypothesis, RT-qPCR and western blot analyses were conducted to

assess the expression levels of fibrosis-associated genes. TGF-β

activation in HSCs significantly enhanced the mRNA and protein

expression levels of α-SMA, COL1A1 and TIMP1 compared with the

levels in untreated HSCs (Fig.

2A-D). In addition, IL-22 treatment of HSCs activated by TGF-β

caused a downregulation in the expression levels of the

aforementioned fibrosis-associated factors (Fig. 2A-D). Therefore, the results

indicated that IL-22 suppressed HSC fibrosis activated by

TGF-β.

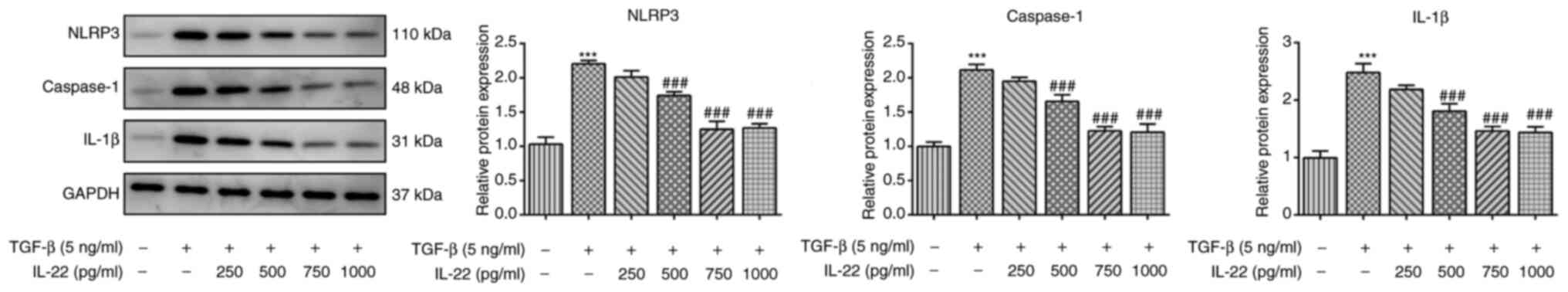

IL-22 inhibits NLRP3 inflammasome

signaling in TGF-β-induced HSCs

Subsequently, the expression levels of key proteins

involved in the NLRP3 inflammasome signaling pathway were detected

by western blot analysis in TGF-β-induced HSCs in order to confirm

whether IL-22 could alleviate inflammation of TGF-β-induced HSCs.

It was observed that TGF-β caused a significant increase in the

expression levels of NLRP3, caspase-1 and IL-1β, and this effect

was reversed by IL-22 (Fig. 3).

Therefore, the results suggested that IL-22 inhibited inflammation

of TGF-β-induced HSCs. Treatment of the cells with 500, 750 and

1,000 ng/ml IL-22 resulted in a significant decrease of the

expression levels of the inflammatory factors. Therefore, IL-22 was

used at a concentration of 750 ng/ml in subsequent experiments.

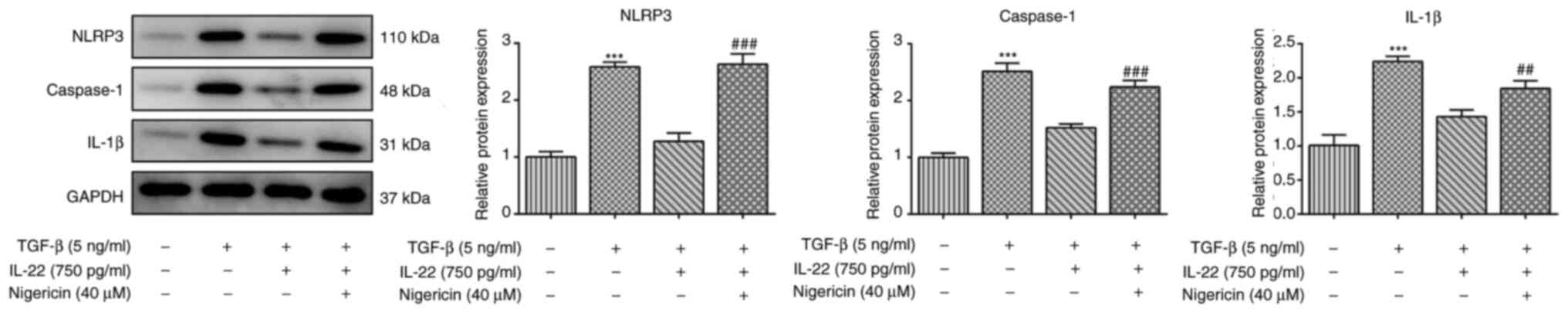

Nigericin reverses the inhibitory

effects of IL-22 on oxidative stress and fibrosis in HSCs

stimulated by TGF-β

To further investigate the exact mechanism by which

IL-22 exerts its cytoprotective effects, the NLRP3 activator

Nigericin was used to treat HSCs. TGF-β significantly upregulated

the protein expression levels of NLRP3, caspase-1 and IL-1β, and

this effect was reversed by co-treatment with TGF-β and IL-22

(Fig. 4). However, the addition of

Nigericin in HSCs co-treated with TGF-β and IL-22 significantly

increased the expression levels of NLRP3, caspase-1 and IL-1β

compared with HSCs treated with TGF-β and IL-22 (Fig. 4). Similarly, CCK-8 and flow

cytometry assays indicated that Nigericin treatment reversed the

inhibition of IL-22 on cell viability and apoptosis of

TGF-β-induced HSCs (Fig. 5A-C). In

addition, the levels of the oxidative stress indices measured in

the present study were significantly reversed following Nigericin

treatment in TGF-β- and IL-22-induced HSCs compared with TGF-β and

IL-22 treatment (Fig. 5D-F).

Moreover, the results from the RT-qPCR and western blot analyses

suggested that the IL-22-induced decreases in the mRNA and protein

expression levels of α-SMA, COL1A and TIMP1 in TGF-β-induced HSCs

were significantly reversed by Nigericin (Fig. 6A-D). The present results indicated

that Nigericin reversed the inhibitory effects of IL-22 on the

induction of oxidative stress and fibrosis in HSCs stimulated by

TGF-β.

Discussion

HSCs are a type of non-parenchymal cells that are

important members in the occurrence and development of liver

fibrosis and cirrhosis (29). The

exposure of HSCs to TGF-β transforms their still state into an

activated cell form, where HSCs transdifferentiate into

proliferative myofibroblasts with pro-fibrogenic transcriptional

and secretory properties that are vital for the development of

liver fibrosis and collagen deposition (30,31).

Therefore, the present study used HSCs activated by TGF-β for the

simulation of liver fibrosis in vitro.

IL-22 is a factor that protects liver tissues from

the development of various chronic diseases, such as nonalcoholic

steatohepatitis, liver fibrosis and hepatocellular carcinoma

(15,32). IL-22 can promote liver repair and

tissue regeneration by stimulating the proliferation and survival

of hepatocytes (33). A previous

study has suggested that IL-22 exerts inhibitory effects on liver

fibrosis and that the attenuation of HSC activation and inhibition

of inflammatory factors by IL-22 can restrict liver fibrogenesis

(34). Overexpression of IL-22

protects mice from liver injury and liver apoptosis and necrosis

stimulated by various factors (35). In the present study, IL-22 inhibited

the proliferation of HSCs and the development of liver fibrosis

in vitro, which was consistent with the aforementioned

studies. Immune response and inflammation in the liver are

contributors of hepatocyte injury and activation of HSCs (29). The induction of oxidative stress and

inflammation activated by TGF-β in HSCs was attenuated by IL-22 in

the present study.

NLRP3 is an intracellular multi-protein complex, and

its activation, which occurs by various types of stimuli, such as

endogenous danger signals and environmental irritants, can lead to

host defense against microbial infections, activation of caspase-1

and further induction of maturation and secretion of IL-1β and

IL-18. This process initiates inflammation (36,37).

Inhibition or inactivation of the NLRP3 inflammasome is suggested

to enhance lipid metabolism and decrease the levels of

inflammation, pyroptosis and the infiltration of immune cells into

plaques, thereby alleviating inflammatory responses (38-40).

An increased number of studies have reported that the inflammasome

and its downstream effectors can trigger liver fibrosis (41-43).

The activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome leads to liver

inflammation, hepatocyte pyroptosis and liver tissue fibrosis in

mice, while pharmacological inhibition of NLRP3 decreases

hepatocyte injury and liver inflammation (42,44).

Moreover, activation of the NLRP3 signaling pathway triggers the

activation of HSCs, which is of great importance for the initiation

and development of liver fibrosis (45,46). A

previous study focused on the potential drug therapies of liver

fibrosis and revealed that the suppression of NLRP3 by oridonin

could effectively alleviate this process (47). The selective inhibitor of NLRP3,

MCC950, can markedly inhibit liver injury in mice induced by bile

duct ligation (41). In the present

study, the NLRP3 activator Nigericin was used to confirm the

specific role of NLRP3 in liver fibrosis. The addition of Nigericin

markedly reversed the inhibitory effect of IL-22 on liver fibrosis

of TGF-β-induced HSCs, which indirectly demonstrated that

inhibition of the NLRP3 inflammasome may be an effective and

potential therapeutic strategy used in the treatment of liver

injury and fibrosis.

In conclusion, the current data indicated that IL-22

may serve an important role in inhibiting liver fibrosis by

inactivation of NLRP3 inflammasome signaling, which may provide

further insight on the underlying mechanism by which IL-22 exerts

protective effects on liver fibrosis. However, in vivo experiments

were not performed and the effects of IL-22-knockdown on NLRP3

inflammasome signaling were not investigated in the present study.

Therefore, further experiments should be performed in future

studies to confirm the present conclusions.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current

study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

ZX and YW searched the literature, designed the

experiments and performed the experiments. NL analyzed, interpreted

the data and wrote the manuscript. ZX revised the manuscript. ZX

and YW confirmed the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors

read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Seki E and Brenner DA: Recent advancement

of molecular mechanisms of liver fibrosis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat

Sci. 22:512–518. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Matsuda M and Seki E: The liver fibrosis

niche: Novel insights into the interplay between fibrosis-composing

mesenchymal cells, immune cells, endothelial cells, and

extracellular matrix. Food Chem Toxicol. 143(111556)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Zhang CY, Yuan WG, He P, Lei JH and Wang

CX: Liver fibrosis and hepatic stellate cells: Etiology,

pathological hallmarks and therapeutic targets. World J

Gastroenterol. 22:10512–10522. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Friedman SL: Mechanisms of disease:

Mechanisms of hepatic fibrosis and therapeutic implications. Nat

Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1:98–105. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Wu S, Liu L, Yang S, Kuang G, Yin X, Wang

Y, Xu F, Xiong L, Zhang M, Wan J, et al: Paeonol alleviates

CCl4-induced liver fibrosis through suppression of hepatic stellate

cells activation via inhibiting the TGF-β/Smad3 signaling.

Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 41:438–445. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Kumar P, Smith T, Rahman K, Thorn NE and

Anania FA: Adiponectin agonist ADP355 attenuates CCl4-induced liver

fibrosis in mice. PLoS One. 9(e110405)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Schuppan D: Liver fibrosis: Common

mechanisms and antifibrotic therapies. Clin Res Hepatol

Gastroenterol. 39 (Suppl 1):S51–S59. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Kunkl M, Amormino C, Frascolla S, Sambucci

M, De Bardi M, Caristi S, Arcieri S, Battistini L and Tuosto L:

CD28 autonomous signaling orchestrates IL-22 expression and

IL-22-regulated epithelial barrier functions in human T

lymphocytes. Front Immunol. 11(590964)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Xie MH, Aggarwal S, Ho WH, Foster J, Zhang

Z, Stinson J, Wood WI, Goddard AD and Gurney AL: Interleukin

(IL)-22, a novel human cytokine that signals through the interferon

receptor-related proteins CRF2-4 and IL-22R. J Biol Chem.

275:31335–31339. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Nagem RA, Colau D, Dumoutier L, Renauld

JC, Ogata C and Polikarpov I: Crystal structure of recombinant

human interleukin-22. Structure. 10:1051–1062. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Wolk K, Witte E, Witte K, Warszawska K and

Sabat R: Biology of interleukin-22. Semin Immunopathol. 32:17–31.

2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Wang S, Li Y, Fan J, Zhang X, Luan J, Bian

Q, Ding T, Wang Y, Wang Z, Song P, et al: Interleukin-22

ameliorated renal injury and fibrosis in diabetic nephropathy

through inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Cell Death

Dis. 8(e2937)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Xing WW, Zou MJ, Liu S, Xu T, Gao J, Wang

JX and Xu DG: Hepatoprotective effects of IL-22 on fulminant

hepatic failure induced by d-galactosamine and lipopolysaccharide

in mice. Cytokine. 56:174–179. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Kim DK, Jo A, Lim HS, Kim JY, Eun KM, Oh

J, Kim JK, Cho SH and Kim DW: Enhanced type 2 immune reactions by

increased IL-22/IL-22Ra1 signaling in chronic rhinosinusitis with

nasal polyps. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 12:980–993.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Wu Y, Min J, Ge C, Shu J, Tian D, Yuan Y

and Zhou D: Interleukin-22 in liver injury, inflammation and

cancer. Int J Biol Sci. 16:2405–2413. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Que R, Shen Y, Ren J, Tao Z, Zhu X and Li

Y: Estrogen receptor β dependent effects of saikosaponin d on the

suppression of oxidative stress induced rat hepatic stellate cell

activation. Int J Mol Med. 41:1357–1364. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Pan X, Shao Y, Wang F, Cai Z, Liu S, Xi J,

He R, Zhao Y and Zhuang R: Protective effect of apigenin magnesium

complex on H2O2-induced oxidative stress and

inflammatory responses in rat hepatic stellate cells. Pharm Biol.

58:553–560. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Novo E, Busletta C, Bonzo LV, Povero D,

Paternostro C, Mareschi K, Ferrero I, David E, Bertolani C,

Caligiuri A, et al: Intracellular reactive oxygen species are

required for directional migration of resident and bone

marrow-derived hepatic pro-fibrogenic cells. J Hepatol. 54:964–974.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Li C, Meng M, Guo MZ, Wang MY, Ju AN and

Wang CL: The polysaccharides from Grifola frondosa attenuate

CCl4-induced hepatic fibrosis in rats via the TGF-beta/Smad

signaling pathway. RSC Advances. 9:33684–33692. 2019.

|

|

20

|

Ting JP, Lovering RC, Alnemri ES, Bertin

J, Boss JM, Davis BK, Flavell RA, Girardin SE, Godzik A, Harton JA,

et al: The NLR gene family: A standard nomenclature. Immunity.

28:285–287. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Wu X, Dong L, Lin X and Li J: Relevance of

the NLRP3 inflammasome in the pathogenesis of chronic liver

disease. Front Immunol. 8(1728)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Feng D, Mukhopadhyay P, Qiu J and Wang H:

Inflammation in liver diseases. Mediators Inflamm.

2018(3927134)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Wang S, Li Y, Fan J, Zhang X, Luan J, Bian

Q, Ding T, Wang Y, Wang Z, Song P, et al: Interleukin-22

ameliorated renal injury and fibrosis in diabetic nephropathy

through inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Cell Death

Dis. 8(e2937)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Wang S, Fan J, Mei X, Luan J, Li Y, Zhang

X, Chen W, Wang Y, Meng G and Ju D: Interleukin-22 attenuated renal

tubular injury in aristolochic acid nephropathy via suppressing

activation of NLRP3 inflammasome. Front Immunol.

10(2277)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Chen E, Cen Y, Lu D, Luo W and Jiang H:

IL-22 inactivates hepatic stellate cells via downregulation of the

TGF-β1/Notch signaling pathway. Mol Med Rep. 17:5449–5453.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Mu M, Zuo S, Wu RM, Deng KS, Lu S, Zhu JJ,

Zou GL, Yang J, Cheng ML and Zhao XK: Ferulic acid attenuates liver

fibrosis and hepatic stellate cell activation via inhibition of

TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway. Drug Des Devel Ther. 12:4107–4115.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Martine P, Chevriaux A, Derangère V,

Apetoh L, Garrido C, Ghiringhelli F and Rébé C: HSP70 is a negative

regulator of NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Cell Death Dis.

10(256)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 25:402–408.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Aslamazova EB, Stroganova EV and

Dzhinanian VL: Pathogenesis of liver cirrhosis. Ter Arkh. 47:30–34.

1975.PubMed/NCBI(In Russian).

|

|

30

|

Lakner AM, Steuerwald NM, Walling TL,

Ghosh S, Li T, McKillop IH, Russo MW, Bonkovsky HL and Schrum LW:

Inhibitory effects of microRNA 19b in hepatic stellate

cell-mediated fibrogenesis. Hepatology. 56:300–310. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Friedman SL: Hepatic stellate cells:

Protean, multifunctional, and enigmatic cells of the liver. Physiol

Rev. 88:125–172. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Hwang S, He Y, Xiang X, Seo W, Kim SJ, Ma

J, Ren T, Park SH, Zhou Z, Feng D, et al: Interleukin-22

ameliorates neutrophil-driven nonalcoholic steatohepatitis through

multiple targets. Hepatology. 72:412–429. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Zenewicz LA, Yancopoulos GD, Valenzuela

DM, Murphy AJ, Karow M and Flavell RA: Interleukin-22 but not

interleukin-17 provides protection to hepatocytes during acute

liver inflammation. Immunity. 27:647–659. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Lu DH, Guo XY, Qin SY, Luo W, Huang XL,

Chen M, Wang JX, Ma SJ, Yang XW and Jiang HX: Interleukin-22

ameliorates liver fibrogenesis by attenuating hepatic stellate cell

activation and downregulating the levels of inflammatory cytokines.

World J Gastroenterol. 21:1531–1545. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Xu K, Sun J, Chen S and Li Y, Peng X, Li M

and Li Y: Hydrodynamic delivery of IL-38 gene alleviates

obesity-induced inflammation and insulin resistance. Biochem

Biophys Res Commun. 508:198–202. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Vandanmagsar B, Youm YH, Ravussin A,

Galgani JE, Stadler K, Mynatt RL, Ravussin E, Stephens JM and Dixit

VD: The NLRP3 inflammasome instigates obesity-induced inflammation

and insulin resistance. Nat Med. 17:179–188. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Swanson KV, Deng M and Ting JPY: The NLRP3

inflammasome: Molecular activation and regulation to therapeutics.

Nat Rev Immunol. 19:477–489. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Duewell P, Kono H, Rayner KJ, Sirois CM,

Vladimer G, Bauernfeind FG, Abela GS, Franchi L, Nuñez G, Schnurr

M, et al: NLRP3 inflammasomes are required for atherogenesis and

activated by cholesterol crystals. Nature. 464:1357–1361.

2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Wang R, Wang Y, Mu N, Lou X, Li W, Chen Y,

Fan D and Tan H: Activation of NLRP3 inflammasomes contributes to

hyperhomocysteinemia-aggravated inflammation and atherosclerosis in

apoE-deficient mice. Lab Invest. 97:922–934. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Abderrazak A, Couchie D, Mahmood DF,

Elhage R, Vindis C, Laffargue M, Matéo V, Büchele B, Ayala MR, El

Gaafary M, et al: Anti-inflammatory and antiatherogenic effects of

the NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitor arglabin in ApoE2.Ki mice fed a

high-fat diet. Circulation. 131:1061–1070. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Qu J, Yuan Z, Wang G, Wang X and Li K: The

selective NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitor MCC950 alleviates

cholestatic liver injury and fibrosis in mice. Int Immunopharmacol.

70:147–155. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Wree A, Eguchi A, McGeough MD, Pena CA,

Johnson CD, Canbay A, Hoffman HM and Feldstein AE: NLRP3

inflammasome activation results in hepatocyte pyroptosis, liver

inflammation, and fibrosis in mice. Hepatology. 59:898–910.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Wu X, Zhang F, Xiong X, Lu C, Lian N, Lu Y

and Zheng S: Tetramethylpyrazine reduces inflammation in liver

fibrosis and inhibits inflammatory cytokine expression in hepatic

stellate cells by modulating NLRP3 inflammasome pathway. IUBMB

Life. 67:312–321. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Mridha AR, Wree A, Robertson AAB, Yeh MM,

Johnson CD, Van Rooyen DM, Haczeyni F, Teoh NC, Savard C, Ioannou

GN, et al: NLRP3 inflammasome blockade reduces liver inflammation

and fibrosis in experimental NASH in mice. J Hepatol. 66:1037–1046.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Watanabe A, Sohail MA, Gomes DA, Hashmi A,

Nagata J, Sutterwala FS, Mahmood S, Jhandier MN, Shi Y, Flavell RA,

et al: Inflammasome-mediated regulation of hepatic stellate cells.

Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 296:G1248–G1257.

2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Inzaugarat ME, Johnson CD, Holtmann TM,

McGeough MD, Trautwein C, Papouchado BG, Schwabe R, Hoffman HM,

Wree A and Feldstein AE: NLR family pyrin domain-containing 3

inflammasome activation in hepatic stellate cells induces liver

fibrosis in mice. Hepatology. 69:845–859. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Liu D, Qin H, Yang B, Du B and Yun X:

Oridonin ameliorates carbon tetrachloride-induced liver fibrosis in

mice through inhibition of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Drug Dev Res.

81:526–533. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|