Introduction

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) is

a well-established technique in pathology laboratories for the

identification of recurrent tumor-specific chromosomal

translocations and copy number variations, assisting in clinical

diagnosis and the selection of treatment strategies (1). FISH offers distinct advantages over

other molecular diagnostic methods. Unlike reverse

transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) or next-generation

sequencing (NGS), FISH utilizes fluorophore-coupled probes that

specifically bind to complementary sequences and provides detailed

intracellular localization of target genes, which is particularly

important when evaluating tissues with small tumor volumes or

tumors consisting of multiple mixed cells (2,3). For

gene rearrangement, a FISH break-apart probe is capable of

detecting all possible rearrangements involving a common breakpoint

region despite corresponding fusion partners or variants. By

contrast, the RT-PCR technique requires multiple pairs of primers

to identify certain known rearrangements, which is time-consuming

and relatively inefficient (4).

There are also limitations with FISH, which may

result in experimental failure or diagnostic errors. The lack of

standard interpretation guidelines for multiple FISH probes leads

to difficulties in explaining atypical, abnormal signal patterns,

such as isolated or unbalanced signals (5). Furthermore, it is necessary for

clinical laboratories to establish an analytical normal cutoff

value for individual probes, which may vary among different

institutions. Another challenge for FISH detection is the sample

quality, which is predominantly determined by the tissue processing

procedure and tissue component. Fixation time, storage,

decalcifying agents, and collagen and extracellular matrix

abundance may influence the intensity of FISH signals and therefore

hinder pathological diagnosis (4).

In clinical practice, one obstacle for FISH is that not all

pathology archives are desirable. Unsatisfactory paraffin blocks or

FFPE sections always lead to interpretation failure and

difficulties in clinical diagnosis. To solve this problem,

conventional FISH procedures urgently require to be improved.

Heat-induced antigen retrieval (HIAR) is an

effective method widely applied in immunohistochemistry to unmask

antigens in FFPE sections (6).

Prompted by this simple technique, the present study provided a

modified FISH protocol. In the pretreatment step, HIAR with either

citrate or Tris-EDTA buffer was applied to poor-quality FFPE

sections that failed in the conventional pathology workflow, and

the detection validity and signal intensity markedly improved. In

addition, evaluation data acquired from two HIAR-assisted FISH

methods were compared and the same interpretation results were

obtained. Overall, this protocol is sufficient for enhancing FISH

signals and produces reliable results.

Materials and methods

Tissue samples

Among 328 archived tumor tissues sent to the

National Cancer Center/National Clinical Research Center for

Cancer/Cancer Hospital and Shenzhen Hospital (Shenzhen, China) for

FISH detection from January 2020 to May 2021, seven FFPE sections

failed in conventional FISH experiments and HIAR-FISH was performed

for these samples to assess the efficacy of the modified protocol.

Furthermore, four adequately handled specimens were randomly

selected to evaluate whether HIAR would affect the original signal

pattern. The median age of the patients (9 male and 2 female) was

45 years. Our study cohort consisted of nine cases of soft tissue

sarcomas and two cases of microphthalmia family translocation renal

cell carcinoma. All samples were excision tissues and sectioned at

4-µm thickness for detection. Patient clinical and pathological

characteristics are summarized in Table I.

| Table IClinicopathological information of the

cases. |

Table I

Clinicopathological information of the

cases.

| Case no. | Sex | Age, years | Site | Specimen type | Diagnosis |

|---|

| 1 | M | 30 | Right shoulder | Excision | Clear cell

sarcoma |

| 2 | F | 34 | Left kidney | Excision | MiT family

translocation renal cell carcinoma |

| 3 | M | 56 | Right kidney | Excision | MiT family

translocation renal cell carcinoma |

| 4 | M | 27 | Left foot | Excision | Synovial sarcoma |

| 5 | M | 33 | Right thigh | Excision | Myxoid

liposarcoma |

| 6 | M | 45 | Right thigh | Excision | Myxoid

liposarcoma |

| 7 | M | 55 | Right thigh | Excision | Pleomorphic

liposarcoma |

| 8 | M | 44 | Chest wall | Excision | High-grade

fibrosarcoma |

| 9 | M | 54 | Retroperitoneal | Excision | Well-differentiated

liposarcoma |

| 10 | M | 48 | Left thigh | Excision | Low-grade fibromyxoid

sarcoma |

| 11 | F | 53 | Abdominal wall | Excision | Undifferentiated

small round cell sarcoma |

FISH protocol

FISH experiments were performed on the interphase

nuclei of 4-µm FFPE sections using commercial probe kits, including

synovial sarcoma translocation chromosome 18 (SS18), Ewing sarcoma

breakpoint region 1 gene (EWSR1), DNA damage inducible transcript 3

(DDIT3), transcription factor binding to IGHM enhancer 3 (TFE3) and

murine double minute-2 (MDM2). The detailed probe information is

listed in Table II, and all

probes were diluted 1:10 with LSI/WCP hybridization buffer (Abbott

Molecular, Inc.).

| Table IIInformation on the probes. |

Table II

Information on the probes.

| Probe | Type | Chromosome

location | Manufacturer | Lot no. |

|---|

| SS18 | Break-apart | 18q11.2 | Abbott Molecular,

Inc. | 30-608250/R3 |

| EWSR1 | Break-apart | 22q12 | Abbott Molecular,

Inc. | 30-608248/R4 |

| DDIT3 | Break-apart | 12q13 | Abbott Molecular,

Inc. | 30-608246/R3 |

| TFE3 | Break-apart | Xp11.23 | ZytoVision | Z-2109 |

| MDM2/CEP12 | Amplification | 12q15 | Abbott Molecular,

Inc. | 30-608268/R2 |

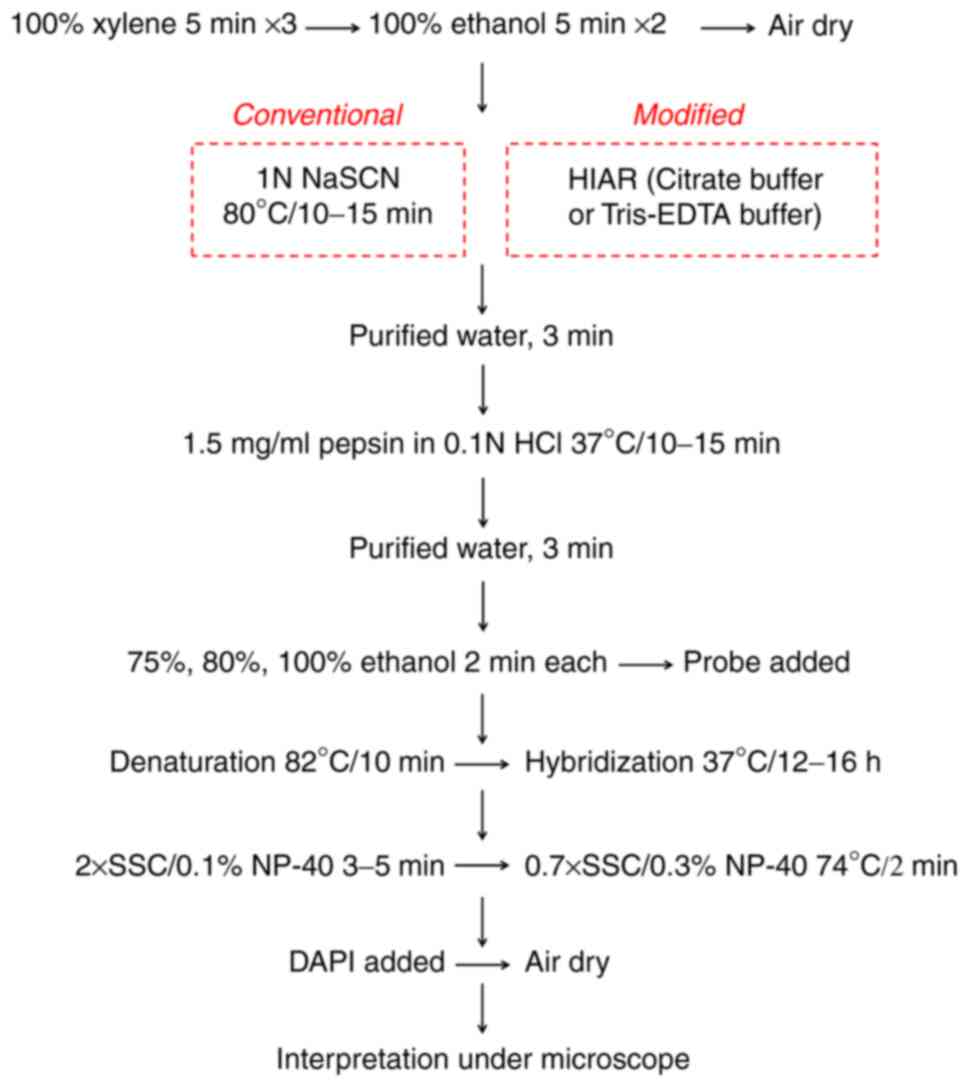

Conventional FISH was performed using a Vysis

paraffin pretreatment IV & post hybridization wash buffer kit

(Abbott Molecular, Inc.) following the manufacturer's protocol, as

illustrated in Fig. 1. In brief,

the FFPE slides were dewaxed in 100% xylene, dehydrated in 100%

ethanol and dried in air. For tissue pretreatment, the slides were

immersed in pretreatment solution containing 1 N sodium thiocyanate

(NaSCN) at 80˚C for 10-15 min and then soaked in purified water for

3 min. Subsequently, the excess water along the edges of the slides

was removed with a paper towel, followed by enzymatic digestion

using pepsin buffer (1.5 mg/ml) for 10-15 min at 37˚C. The slides

were then immersed in purified water for 3 min at room temperature.

After ethanol gradient dehydration, diluted probes were applied to

the target tissue areas and the slides were processed with the

ThermoBrite Denaturation/Hybridization System (Abbott Molecular,

Inc.) using the following program: 10 min at 82˚C and 12-16 h at

37˚C. The next day, the slides were rapidly washed with 2X saline

sodium citrate buffer (SSC)/0.1% nonidet P (NP)-40 at ambient

temperature for 3-5 min and 0.7X SSC/0.3% NP-40 at 74˚C for 2 min.

After air-drying in the dark, the tissues were counterstained using

DAPI to visualize nuclei. FISH signals were viewed with suitable

filter sets under a fluorescence microscope (magnification, x600;

Leica Microsystems GmbH) and the images were captured using a

Bioview Allegro Plus System (Abbott Molecular, Inc.) with the same

parameter settings.

HIAR in FISH

HIAR was applied for slides exhibiting

unsatisfactory signals in conventional FISH (Fig. 1). In the present study, two AR

solutions of different pH values were used: Citrate buffer (pH=6.0)

and Tris-EDTA buffer (pH=9.0). In detail, AR solution was added

into a pressure cooker on a hotplate. The lid of the cooker was

simply rested on top at this point. After boiling, slides were

rapidly immersed in AR solution and the cooker lid was secured.

Once the cooker reached the full pressure, conditions were

maintained for 2 min. Subsequently, the pressure cooker was placed

in an empty sink and the pressure valve was carefully released.

Once depressurized, the lid was removed and slides were cooled at

room temperature for 60 min.

FISH signal enumeration

For each case, the slide adequacy was evaluated

according to three criteria: i) The background should be dark and

relatively free of fluorescence particles; ii) the fluorescence

signals under both channels should appear unequivocal, bright and

easily identified; and iii) the nuclei morphology should be intact

and distinguishable. Only slides with these features were

interpreted.

A minimum of 50 non-overlapping nuclei were counted

for each case independently by two pathologists (16 and 2 years of

experience, respectively) in a blinded manner. For break-apart

probes targeting EWSR1, DDIT3, SS18 and TFE3, the typical

rearrangement pattern was 1F/1G/1O (1 fusion, 1 green, 1 orange)

and the cell was considered positive when at least one set of green

and orange signals were separated at ≥2 signal diameters apart.

Cells without rearrangement exhibited fused or adjacent (distance

<2 signal diameters) green and orange signals. The cutoff value

for each break-apart probe was 15% in our laboratory, which was

established as recommended by the American College of Medical

Genetics guidelines (1,7). For the MDM2/CEP12 probe,

amplification was considered to have occurred in cells with an MDM2

(orange)/CEP12 (green) ratio ≥2.0.

Statistical analysis

To quantify the hybridization efficiency of

different FISH protocols, three captured views of individual

samples were randomly selected and quantification of i) the total

cell number, ii) number of cells with clear fluorescence signals

(either green or orange), and iii) number of cells conforming to

interpretation criteria above was performed. The percentage of

cells is presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean. All

analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software 5.0 (GraphPad

Software, Inc.).

Results

HIAR markedly promotes FISH efficiency

in detecting fluorescence signals

In conventional FISH experiments using commercial

pretreatment kits, all seven pathology samples failed to meet the

interpretation standard because the density ratio of signal to

background was low in either the orange or green channel, making it

impossible to identify signal patterns. To obtain satisfactory

results, HIAR was introduced to replace the pretreatment step. Of

the seven samples, five were processed with both citrate buffer and

Tris-EDTA buffer, while the remaining two samples were only treated

with Tris-EDTA buffer due to the lack of FFPE slides provided by

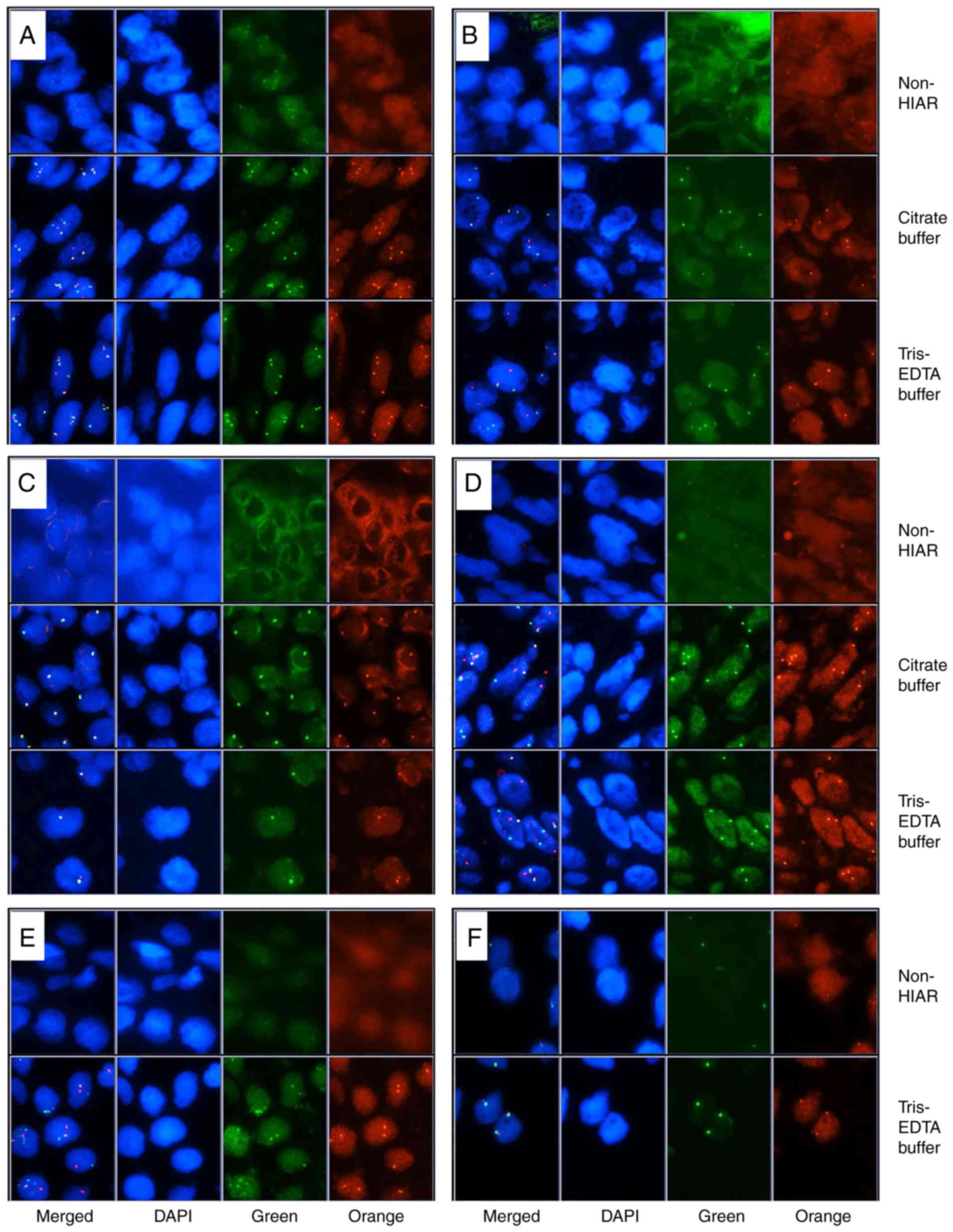

external medical centers. As illustrated in Fig. 2A-F, FISH analysis was successfully

performed on six of the slides, which yielded clear and bright

fluorescence signals in both the orange and green channels with

intact cell nucleus morphology. The other sample hybridized with

DDIT3 only exhibited a marginal improvement after HIAR using either

HIAR buffer (data not shown). To directly illustrate the enhanced

hybridization efficiency after antigen retrieval, the ratio of

cells satisfying the aforementioned interpretation criteria were

quantified as indicated, as well as cells exhibiting fluorescence

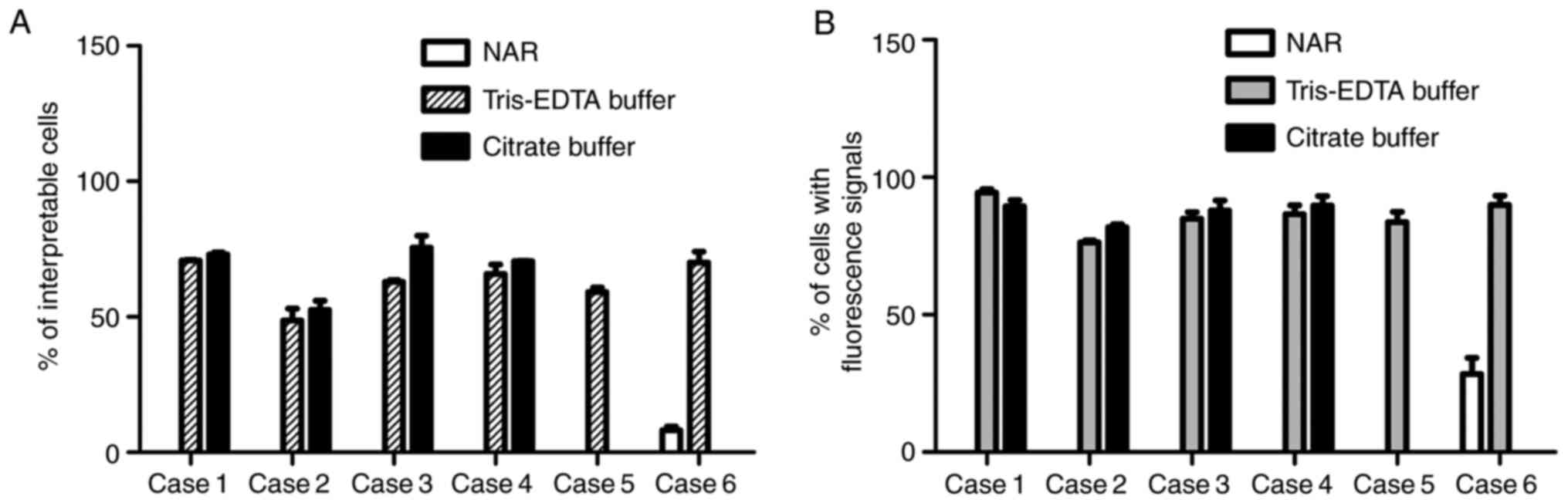

signals, either orange or green. As depicted in Fig. 3A, only case 6 contained several

interpretable cells (<10%) after the conventional FISH

experiment, but the retrieval treatment with either Tris-EDTA or

citrate buffer significantly increased the ratio of non-overlapped

cells clearly exhibiting both green and orange signals

(P<0.001). Furthermore, the signal retrieval effect of the two

buffers was compared and no significant difference was observed in

cases 1-4. Similar results were obtained after calculating the

percentage of cells exhibiting either a green or an orange signal

(Fig. 3B). These data indicated an

encouraging effect of HIAR in facilitating probe binding and

fluorescence signal restoration for poor-quality FFPE slides.

Consistent interpretation results

obtained with two HIAR-FISH methods

After assessing the signal quality of HIAR-FISH, two

experienced pathologists interpreted the FISH slides separately to

compare the results from the two assays. The detailed counting

results and final diagnosis are listed in Table III. For slides 1-4, stable

results were obtained from two HIAR-FISH experiments, suggesting

that these two AR solutions significantly amplified fluorescence

intensity without influencing signal patterns. In addition, the

interpretation results for all six samples provided by the two

pathologists had high consistency.

| Table IIIFluorescence in situ

hybridization interpretation results of poor-quality FFPE

sections. |

Table III

Fluorescence in situ

hybridization interpretation results of poor-quality FFPE

sections.

| Case/probe | HIER buffer | Pathologist 1 | Pathologist 2 |

|---|

| 1/EWSR1 | Tris-EDTA buffer | Positive | Positive |

| | | (1G/1O/1-3F, 30%;

3-4F, 52%; other, 18%) | (1G/1O/1-3F, 22%;

3-4F, 52%; other, 26%) |

| | Citrate buffer | Positive | Positive |

| | | (1G/1O/1-3F, 28%;

3-4F, 44%; other, 28%) | (1G/1O/1-3F, 30%;

3-4F, 40%; other, 30%) |

| 2/TFE3 | Tris-EDTA buffer | Positive | Positive |

| | | (1G/1O/1F, 72%; 2F,

12%; other, 16%) | (1G/1O/1F, 64%; 1-2F,

8%; other, 28%) |

| | Citrate buffer | Positive | Positive |

| | | (1G/1O/1F, 62%,

1G/1O, 20%; 1-2F, 8%; other, 10%) | (1G/1O/1F, 52%,

1G/1O, 1-2F, 12%; other, 24%) |

| 3/TFE3 | Tris-EDTA

buffer | Negative | Negative |

| | | (1F, 82%; 2F,

18%) | (1F, 86%; 2F,

14%) |

| | Citrate buffer | Negative | Negative |

| | | (1F, 78%; 2F,

22%) | (1F, 82%; 2F,

18%) |

| 4/SS18 | Tris-EDTA

buffer | Positive | Positive |

| | | (1G/1O/1F, 24%;

atypical break-apart patterns, 60%; 1-2F, 16%) | (1G/1O/1F, 20%;

atypical break-apart patterns, 60%; 1-2F, 20%) |

| | Citrate buffer | Positive | Positive |

| | | (1G/1O/1F, 20%;

atypical break-apart patterns, 58% 1-2F, 22%) | (1G/1O/1F, 20%;

atypical break-apart patterns, 58%; 1-2F, 22%) |

| 5/DDIT3 | Tris-EDTA

buffer | Positive | Positive |

| | | (1G/1O/1F, 48%; 2F,

30%; other, 22%) | (1G/1O/1F, 44%;

1-2F, 36%; other, 20%) |

| | Citrate buffer | N/A | N/A |

| 6/MDM2 | Tris-EDTA

buffer | Negative | Negative |

| | | (MDM2/cell,

1.6a; CEP12/cell,

1.7b; MDM2/CEP12,

0.94c) | (MDM2/cell, 1.66;

MDM2/CEP12, 1.0) |

| | Citrate buffer | N/A | N/A |

HIAR does not affect the signal of

adequately handled samples

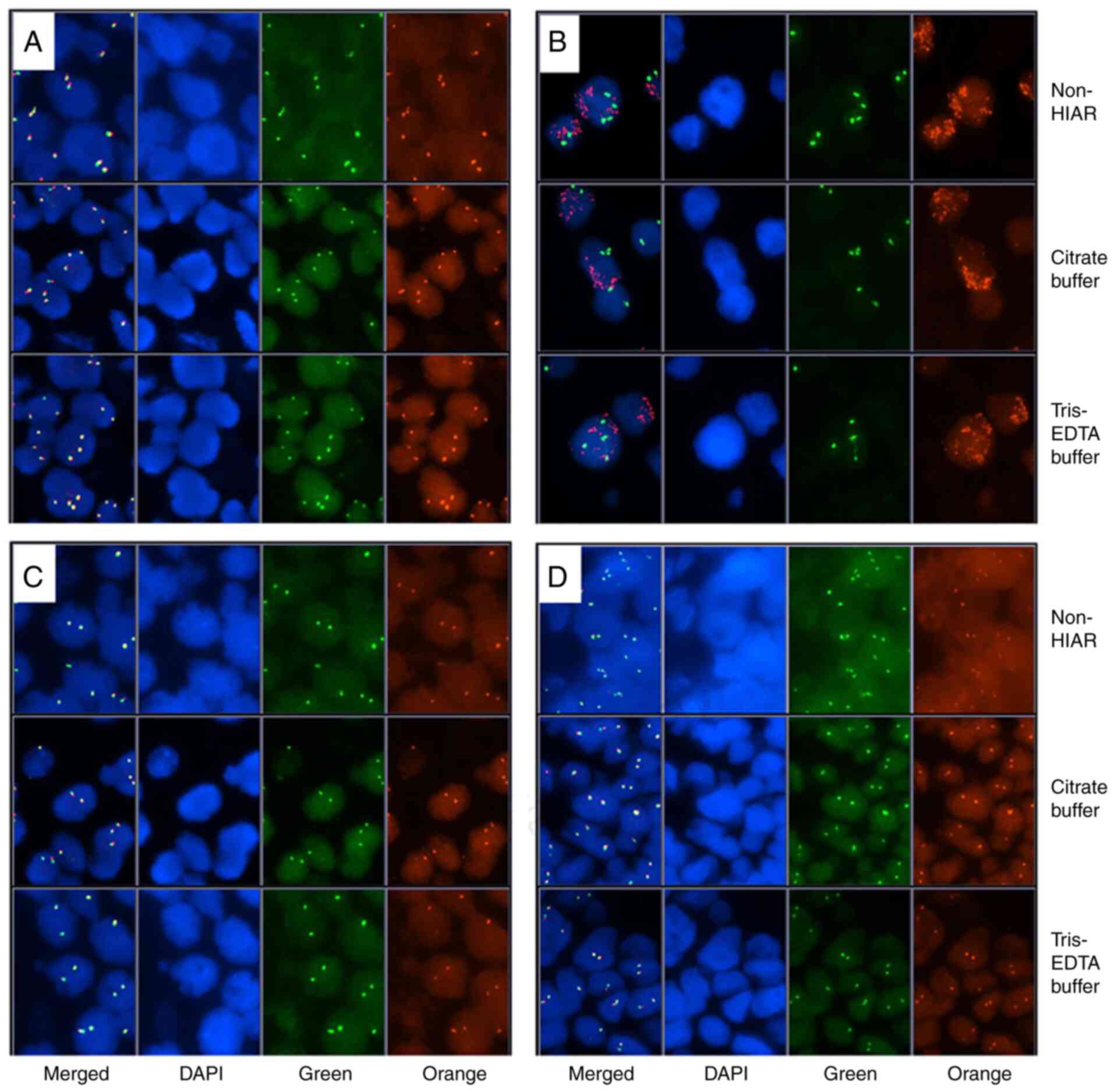

To evaluate the effect of HIAR on well-handled

samples, 4 specimens exhibiting adequate signals after conventional

FISH were randomly selected and HIAR was applied to them. First,

the signal intensity of these slides was compared and no

significant difference was observed between conventional and

HIAR-FISH using either citrate or Tris-EDTA buffer (Fig. 4A-D). The two pathologists then

interpreted the FISH slides and similar results were obtained after

introducing HIAR (Table IV).

These data indicated that HIAR did not influence the results of

FISH in adequately handled samples.

| Table IVFluorescence in situ

hybridization interpretation results of adequately handled

samples. |

Table IV

Fluorescence in situ

hybridization interpretation results of adequately handled

samples.

| Case/probe | HIER buffer | Pathologist 1 | Pathologist 2 |

|---|

| 8/SS18 | Tris-EDTA

buffer | Negative | Negative |

| | | (2F, 78%; 3F, 8%;

other, 14%) | (2F, 80%; 3F, 10%;

other, 10%) |

| | Citrate buffer | Negative | Negative |

| | | (2F, 80%; 3F, 8%;

other, 12%) | (2F, 76%; 3F, 12%;

other, 12%) |

| 9/MDM2 | Tris-EDTA

buffer | Positive | Positive |

| | | (MDM2/cell,

21.8a; CEP12/cell,

2.2b; MDM2/CEP12,

9.91c) | (MDM2/cell, 23.3;

CEP12/cell, 2.4; MDM2/CEP12, 9.71) |

| | Citrate buffer | Positive | Positive |

| | | (MDM2/cell, 22.6;

CEP12/cell, 2.5; MDM2/CEP12, 9.04) | (MDM2/cell, 22.9;

CEP12/cell, 1.9; MDM2/CEP12, 12.05) |

| 10/DDIT3 | Tris-EDTA

buffer | Negative | Negative |

| | | (2F, 64%; 3F,

10%;1F, 10%; other, 16%) | (2F, 68%; 3F, 10%;

1F, 12%; other, 10%) |

| | Citrate buffer | Negative | Negative |

| | | (2F, 55%; 3F, 16%;

1F, 12%; other, 17%) | (2F, 63%; 3F, 12%;

1F, 8%; other, 17%) |

| 11/EWSR1 | Tris-EDTA

buffer | Negative | Negative |

| | | (2F, 80%; 1F, 12%;

1G/1O/1F, 2%; other, 6%) | (2F, 75%; 1F, 14%;

1G/1O/1F, 3%; other, 8%) |

| | Citrate buffer | Negative | Negative |

| | | (2F, 79%; 1F, 8%;

1G/1O/1F, 3%; other, 10%) | (2F, 78%; 1F, 15%;

1G/1O/1F, 2%; other, 5%) |

Discussion

Over the decades, precise genome testing has

achieved rapid progress, demonstrating great value in definitive

and differential diagnoses as well as guidance for therapy for

multiple tumor types. FISH is a useful pathological tool for

detecting chromosome rearrangement, amplification, gain or deletion

and polysomy (8). In the present

study, five specific DNA probes extensively used in pathological

diagnosis were applied, including EWSR1, TFE3, SS18, DDIT3 and

MDM2. Chromosomal rearrangement involving the EWSR1 (22q12)

prevalently occurs in Ewing sarcoma, and EWSR1 mostly fuses with

FLI1 (11q24) and ERG (21q22) (9).

Chromosomal translocation of TFE3 (Xp11.2) is an important

characteristic of alveolar soft part sarcoma and microphthalmia

transcription factor family translocation renal cell carcinoma

(4,10). Recurrent DDIT3 (12q13)

rearrangement is commonly regarded as a diagnostic marker for

myxoid liposarcoma with high specificity and sensitivity (11). SS18 (18q11) rearrangement occurs in

90% of synovial sarcomas but has not yet been detected in other

sarcomas (12). MDM2 gene

amplification is an important index for classifying atypical

lipomatous tumor/well-differentiated liposarcoma and the

amplification level may influence tumor dedifferentiation and

progression (13,14).

In laboratory practice, successful FISH detection

first requires appropriate sample handling, including fixation,

embedding and preservation. Poorly processed FFPE sections

frequently fail with regard to signal observation and clinical

diagnosis. During tissue fixation, formaldehyde produces inter- and

intra-molecular crosslinks in proteins and nucleic acids. Methylene

bridges are assumed to be the major structure of those crosslinks

and are stable between molecules (15). Inappropriate fixation procedures,

such as over-fixation, lead to excessive formation of methylene

bridges and a large proportion of nucleic acids may be trapped in

protein-protein crosslinks, hampering probe binding to targeted DNA

sequences (16). Several

troubleshooting tips have been proposed to solve this problem. One

recommended method is adjusting the pretreatment and/or digestion

time. Conventionally, NaSCN and pepsin are used as pretreatment and

digestion reagents, respectively, to cleave crosslinks and increase

tissue permeability. In the present study, slides were routinely

immersed in NaSCN at 80˚C for 10-15 min and subsequently, tissues

were digested with pepsin at 37˚C for 10-15 min. To obtain clear

fluorescence signals in the present study, the pretreatment and

digestion time was first prolonged in increments of 3-5 min.

However, extending the pretreatment time resulted in only minor

signal intensity enhancement and long-term (20-25 min) soaking in

NaSCN solution always resulted in swollen nuclei, which were

difficult to distinguish due to nucleus overlap, particularly in

dense connective tissues. Similarly, limited improvement was

observed after increasing the duration of digestion. By contrast,

excessive digestion led to morphological degradation of nuclei and

other strategies were required to be sought to resolve this

issue.

Several studies have used a microwave oven during

the DNA-DNA hybridization process. In a previous study,

intermittent microwave irradiation at 42˚C with a 3-sec

irradiation/2-sec stop cycle for 1 h, followed by overnight

incubation at 42˚C was employed (17). According to their report, among

paraffin blocks yielding no signal in regular FISH, >95%

produced acceptable signals following this modified protocol and

scanning electron microscopy revealed a looser nuclear matrix in

samples exposed to microwave radiation, suggesting a possible

mechanism underlying the enhanced probe binding activity (17). In addition, Weise et al

(18) compared several different

microwave settings during probe hybridization and recommended a

treatment of 4-5 times of microwave exposure within 30 min at 600

W. Soriani et al (19)

applied the rapid FISH approach by Weise et al (18) to detect chromosome

t(15;17)(q24;q21) in acute promyelocytic leukemia and obtained

appreciable results.

Prompted by the marked effect of microwave-produced

heat in signal retrieval during DNA hybridization, HIAR may be

proposed for increasing cell permeability and therefore enhancing

specific probe binding ability. It is now generally accepted that

the removal of intra-molecular crosslinks depends on the total

amount of heat energy applied during the retrieval process instead

of the heating device utilized (20). Heating undermines the gel-like

structure formed by crosslinks in proteins and nucleic acids,

facilitating probe penetration into nuclei and subsequent DNA

binding (21). Unlike intermittent

microwave irradiation, requiring multiple manual operations and

careful temperature monitoring, the present method is relatively

easy to follow since HIAR is already widely utilized in

immunohistochemistry.

The present study has potential limitations. Up to

now, only seven samples for which conventional FISH failed were

collected and modified FISH was performed on them. Furthermore, due

to the limited number of FFPE slides that were provided for each

patient, only one necessary probe was applied to each specimen to

guarantee the pathological diagnosis and comparison of signal

retrieval efficiency between HIAR- and microwave-assisted FISH was

not possible. For cases exhibiting atypical signal patterns, gene

rearrangement cannot be validated using other methods, such as

RT-PCR or NGS, as no extra sections were available for further

assessment. These limitations may be addressed in future research

after establishing a larger cohort. However, the current data are

encouraging for the use of HIAR in FISH to enhance signal

intensity, particularly for challenging specimens in clinical

practice.

In summary, HIAR, which has been applied routinely

in our laboratory for tumor tissues yielding weak or no signal

after a standard FISH workflow, is a reliable tool in clinical FISH

detection with high performance in augmenting fluorescence

signals.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant no. 82002829) and the Sanming Project of

Medicine in Shenzhen (grant no. SZSM201812076).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current

study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

QY, CZ, WH and LL conceived the study. QY and CZ

conducted the experiments and interpreted the results. QY performed

the literature search, analyzed the data and drafted the

manuscript. WH and LL revised the work for important intellectual

content. WH and LL confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Medical Ethics

Committee of the National Cancer Center/National Clinical Research

Center for Cancer/Cancer Hospital & Shenzhen Hospital, Chinese

Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College

(Shenzhen, China; approval no. 2019-39-2). Written informed consent

was obtained from each patient included in this study.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Gu J, Smith JL and Dowling PK:

Fluorescence in situ hybridization probe validation for clinical

use. Methods Mol Biol. 1541:101–118. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Tanas MR, Rubin BP, Tubbs RR, Billings SD,

Downs-Kelly E and Goldblum JR: Utilization of fluorescence in situ

hybridization in the diagnosis of 230 mesenchymal neoplasms: An

institutional experience. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 134:1797–1803.

2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Sirvent N, Coindre JM, Maire G, Hostein I,

Keslair F, Guillou L, Ranchere-Vince D, Terrier P and Pedeutour F:

Detection of MDM2-CDK4 amplification by fluorescence in situ

hybridization in 200 paraffin-embedded tumor samples: Utility in

diagnosing adipocytic lesions and comparison with

immunohistochemistry and real-time PCR. Am J Surg Pathol.

31:1476–1489. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Vargas AC, Selinger C, Satgunaseelan L,

Cooper WA, Gupta R, Stalley P, Brown W, Soper J, Schatz J, Boyle R,

et al: FISH analysis of selected soft tissue tumors: Diagnostic

experience in a tertiary center. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 15:38–47.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Papp G, Mihály D and Sápi Z: Unusual

signal patterns of break-apart FISH probes used in the diagnosis of

soft tissue sarcomas. Pathol Oncol Res. 23:863–871. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Magaki S, Hojat SA, Wei B, So A and Yong

WH: An introduction to the performance of immunohistochemistry.

Methods Mol Biol. 1897:289–298. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Mascarello JT, Hirsch B, Kearney HM,

Ketterling RP, Olson SB, Quigley DI, Rao KW, Tepperberg JH,

Tsuchiya KD and Wiktor AE: Working Group of the American College of

Medical Genetics Laboratory Quality Assurance Committee. Section E9

of the American college of medical genetics technical standards and

guidelines: Fluorescence in situ hybridization. Genet Med.

13:667–675. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Bertram S and Schildhaus HU: Fluorescence

in situ hybridization for the diagnosis of soft-tissue and bone

tumors. Pathologe. 41:589–605. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar : (In German).

|

|

9

|

Grünewald TGP, Cidre-Aranaz F, Surdez D,

Tomazou EM, de Álava E, Kovsar H, Sorensen PH, Delattre O and

Dirksen U: Ewing sarcoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 4(5)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Wyvekens N, Rechsteiner M, Fritz C, Wagner

U, Tchinda J, Wenzel C, Kuithan F, Horn LC and Moch H: Histological

and molecular characterization of TFEB-rearranged renal cell

carcinomas. Virchows Arch. 474:625–631. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Cheng L, Zhang S, Wang L, MacLennan GT and

Davidson DD: Fluorescence in situ hybridization in surgical

pathology: principles and applications. J Pathol Clin Res. 3:73–99.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Stacchiotti S and Van Tine BA: Synovial

sarcoma: Current concepts and future perspectives. J Clin Oncol.

36:180–187. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Ware PL, Snow AN, Gvalani M, Pettenati MJ

and Qasem SA: MDM2 copy numbers in well-differentiated and

dedifferentiated liposarcoma: Characterizing progression to

high-grade tumors. Am J Clin Pathol. 141:334–341. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Miura Y, Keira Y, Ogino J, Nakanishi K,

Noguchi H, Inoue T and Hasegawa T: Detection of specific genetic

abnormalities by fluorescence in situ hybridization in soft tissue

tumors. Pathol Int. 62:16–27. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Shi SR, Shi Y, Taylor CR and Gu J: New

dimensions of antigen retrieval technique: 28 Years of development,

practice, and expansion. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol.

27:715–721. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Yamashita S and Katsumata O: Heat-induced

antigen retrieval in immunohistochemistry: Mechanisms and

applications. Methods Mol Biol. 1560:147–161. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Sugimura H: Detection of chromosome

changes in pathology archives: An application of microwave-assisted

fluorescence in situ hybridization to human carcinogenesis studies.

Carcinogenesis. 29:681–687. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Weise A, Liehr T, Claussen U and Halbhuber

KJ: Increased efficiency of fluorescence in situ hybridization

(FISH) using the microwave. J Histochem Cytochem. 53:1301–1303.

2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Soriani S, Mura C, Panico AR, Scarpa AM,

Recchimuzzo P, Dadati R, Farioli R, De Canal G, Mura MA and Cesana

C: Rapid detection of t(15;17)(q24;q21) in acute promyelocytic

leukaemia by microwave-assisted fluorescence in situ hybridization.

Hematol Oncol. 35:94–100. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Yamashita S: Heat-induced antigen

retrieval: Mechanisms and application to histochemistry. Prog

Histochem Cytochem. 41:141–200. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Stumptner C, Pabst D, Loibner M, Viertler

C and Zatloukal K: The impact of crosslinking and non-crosslinking

fixatives on antigen retrieval and immunohistochemistry. N

Biotechnol. 52:69–83. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|