Introduction

Heart failure (HF) refers to a syndrome in which

venous reflux is normal and cardiac output is reduced due to

primary cardiac damage, which cannot meet the requirements of

tissue metabolism. Pulmonary circulation and/or systemic

circulation congestion and inadequate tissue perfusion are the

major characteristics of clinical HF; thus, it is also called

congestive HF and is the final stage of heart disease due to

various causes (1). With an aging

population, HF-associated morbidity and mortality have exhibited an

upward trend in the United States and globally (2). It has been indicated that certain

patients with HF still maintained a relatively normal left

ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), which is known as HF with

preserved ejection fraction (HFPEF) (3). Patients with HFPEF accounted for ~50%

of all cases of HF and their clinical prognosis is poor (4). Echocardiography is a non-invasive

examination method with simple operation, so it is widely adopted

in the clinic to assess heart function. However, HFPEF cannot

always be detected at the early stages, whilst early diagnosis is

important for saving the life of affected patients and easing the

disease burden. With the fast development in biomedical technology,

biomarker-based determination has received increasing attention.

Plasma pro-brain natriuretic peptide (BNP), a hormonal biologically

active substance secreted by left ventricular wall cells, is the

major serum marker to evaluate the severity of HF (5).

As a class of non-coding transcripts, long

non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) are >200 nt in length and regulate

gene expression at epigenetic, transcriptional and

post-transcriptional levels (6,7).

Aberrant expression levels of various lncRNAs in the serum have

recently been utilized as diagnostic biomarkers, e.g. for cardiac

diseases (8). For instance,

long-intergenic noncoding RNA predicting cardiac remodeling was

able to predict survival in patients with HF (9). HOX transcript antisense RNA is an

essential mediator of acute myocardial infarction (10). Antisense non-coding RNA in the INK4

locus is of important diagnostic value for in-stent restenosis

(11). The lncRNA taurine

upregulated gene 1 (TUG1) is a newly discovered lncRNA, which was

originally detected in mouse retinal cells treated with taurine-β

(12). However, the molecular

function of TUG1 in patients with HFPEF and hypertension has

remained elusive. In the present study, the role of circulating

TUG1 in the diagnosis of HFPEF in subjects with hypertension was

investigated.

Materials and methods

Participants and samples

Between January 2017 and January 2019, 80

aged/elderly hypertensive patients (Table I) with HFPEF were recruited as the

‘observation group’ at The First Affiliated Hospital of Jinzhou

Medical University (Jinzhou, China). Written informed consent was

provided by all study participants. The present study was approved

by the ethics committee of The First Affiliated Hospital of Jinzhou

Medical University. The diagnostic criteria for HFPEF were

according to the European Society of Cardiology guidelines for the

diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic HF from 2016(13): i) Signs or symptoms of HF; ii)

elevated levels of BNPs (BNP>35 pg/ml and/or NT-proBNP>125

pg/ml); iii) evidence of cardiac structural alterations (left

atrial volume index >34 ml/m2 or a left ventricular

mass index ≥115 g/m² for males and ≥95 g/m² for females) or

functional features of diastolic dysfunction [ratio of early

diastolic mitral flow velocity to early diastolic mitral ring

velocity (E/e') ≥13 and a mean E' septal and lateral wall <9

cm/sec]; iv) normal or slightly abnormal LVEF (>50%) and the

left ventricle was not enlarged; and v) left ventricular diastolic

dysfunction. The patients in the observation group were included if

they fulfilled the following criteria: i) Age, 60-75 years; ii)

systolic blood pressure >150 mmHg and normal diastolic blood

pressure; iii) conformed to the diagnostic criteria of HFPEF.

Patients were excluded under the following circumstances: i) LVEF

<50%; ii) chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, valvular heart

disease, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, restrictive cardiomyopathy,

pericardial disease or diabetes mellitus; iii) hematological and

neoplastic disorders or autoimmune diseases; iv) severe liver or

kidney dysfunction. Furthermore, 80 aged/elderly hypertensive

patients (age, 60-75 years; systolic blood pressure >150 mmHg;

not combined with any other diseases) were enrolled as a control

group. Furthermore, according to the New York Heart Association

(NYHA) cardiac function classification (14), the patients in the observation group

were divided into four groups with NYHA I-IV, respectively

(Table II). After overnight

fasting, 5 ml peripheral blood samples were collected from the

brachial vein of each patient. Whole blood was centrifuged at 1,500

x g for 5 min at room temperature and the supernatant was

immediately frozen and stored at -80˚C for further analysis.

| Table IClinical characteristics of patients

in the control and observation groups. |

Table I

Clinical characteristics of patients

in the control and observation groups.

| Variable | Control group

(n=80) | Observation group

(n=80) | P-value |

|---|

| Age (years) | 68.24±6.13 | 66.87±7.44 | 0.125 |

| Male sex (%) | 48 (60%) | 46 (57.5%) | 0.748 |

| BMI

(kg/m2) | 26.21±2.58 | 25.78±2.97 | 0.528 |

| Smoking (%) | 50 (62.5%) | 49 (61.25%) | 0.871 |

| History of

hypertension (years) | 10.11±2.81 | 11.36±1.44 | 0.215 |

| Blood glucose

(mmol/l) | 6.25±1.13 | 6.12±1.44 | 0.853 |

| Serum creatinine

(µmol/l) | 82.56±10.54 | 75.58±9.38 | 0.521 |

| Hyperlipemia (%) | 16 (25%) | 24 (30%) | 0.479 |

| NYHA | | | |

|

II | / | 34 | |

|

III | / | 26 | |

|

IV | / | 20 | |

| Table IIEchocardiographic indexes in the

control and observation groups. |

Table II

Echocardiographic indexes in the

control and observation groups.

| Variable | Control group

(n=80) | Observation group

(n=80) | P-value |

|---|

| LVEDD (mm) | 50.56±10.52 | 51.32±9.78 | 0.425 |

| LAD (mm) | 38.56±7.63 | 48.21±5.96 | 0.001 |

| LVEF (%) | 0.64±0.08 | 0.63±0.05 | 0.358 |

| LVPWT (mm) | 9.26±1.38 | 9.19±1.71 | 0.481 |

| IVS (mm) | 9.87±1.85 | 9.17±1.31 | 0.412 |

| E/A | 1.67±0.81 | 0.89±0.47 | 0.001 |

Measurement of NT-proBNP

The concentration of NT-proBNP in the serum of each

participant was determined using an ELISA kit (cat. no. DY3604-05;

R&D Systems, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's protocol. A

microplate reader was used to determine the absorbance at 450

nm.

Assessment of cardiac function

The patients were kept in a left lateral position

for echocardiography examinations. M-mode echocardiography was used

for the determination of the left ventricular end diastolic

diameter (LVEDD), left atrial diameter (LAD), left ventricular

posterior wall thickness and interventricular septal thickness

(LVPWT), interventricular septal thickness (IVS). Pulse Doppler

echocardiography was adopted to measure the ratio of the peak flow

velocity in the early diastolic phase to the peak flow velocity in

the late diastolic phase (E/A).

Reverse transcription-quantitative

(RT-q)PCR analysis

Total RNA in the serum of all paticipants was

isolated using TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) following the manufacturer's protocol.

Complementary DNA synthesis was performed using the TaqMan MicroRNA

RT kit (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Total

RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA at 37˚C for 2 h, at 95˚C for

15 min and then was cooled on ice. Real-time PCR was performed

using SYBR® Premix Ex Taq™ II (Takara Bio, Inc.). The

relative expression was analyzed using the 2-ΔΔCq method

(15) with normalization to GAPDH.

The primer sequences used for qPCR were shown as follows: TUG1

forward, 5'-TAGCAGTTCCCCAATCCTTG-3' and reverse,

5'-CACAAATTCCCATCATTCCC-3' and GAPDH forward,

5'-GGGAGCCAAAAGGGTCAT-3' and reverse,

5'-GTGGTTTGAGGGCTCTTACTCCTT-3'. The qPCR thermocycling conditions

used were as follows: Initial denaturation at 95˚C for 10 min,

followed by denaturation at 94˚C for 15 sec, annealing at 59˚C for

30 sec and extension at 70˚C for 30 sec, for 40 cycles.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS

software (version no. 21.0; IBM Corp.). All measurement data were

expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. Differences were

calculated using Student's t-test or one-way ANOVA followed by

Tukey's post hoc test. The correlation analysis was performed using

Spearman's correlation method. The diagnostic efficacy of the

plasma indexes was determined using receiver operating

characteristics (ROC) curve analyses. P<0.05 was considered to

indicate statistical significance.

Results

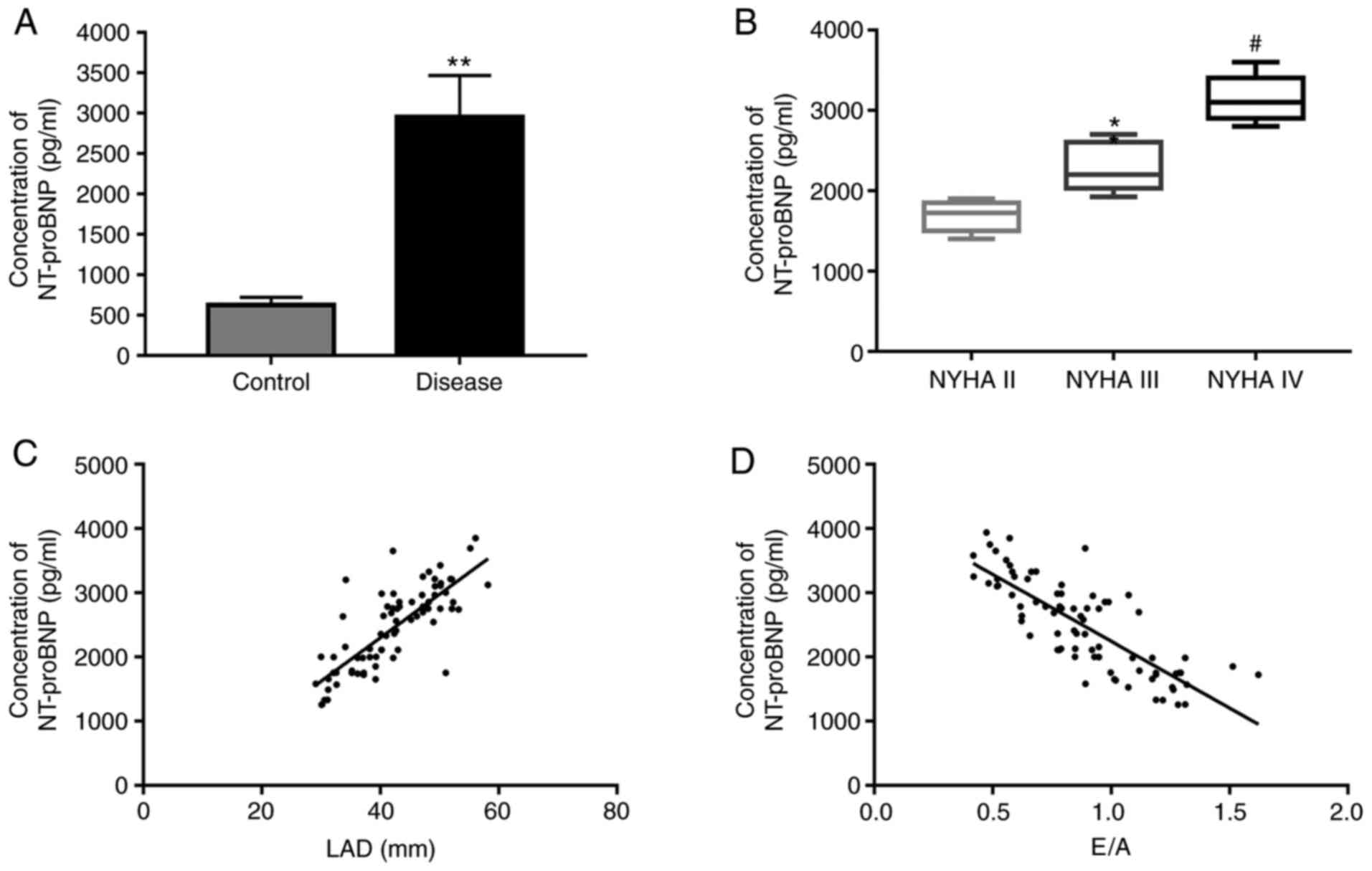

NT-proBNP concentration is increased

in serum of hypertensive patients with HFPEF

The general demographic and clinicopathological data

of all patients are listed in Table

I. There were no significant differences in clinical materials

of these two groups including age, gender and some risk factors

(P>0.05). First, the NT-proBNP concentration in the serum of

patients was measured using ELISA. The results demonstrated that

the NT-proBNP concentration was significantly upregulated in the

observation group as compared with that in the control group

(Fig. 1A). Furthermore, the

NT-proBNP concentration was significantly increased with the

severity degree of HF (Fig. 1B).

Spearman's rank correlation analysis demonstrated that the

NT-proBNP concentration was positively correlated with the LAD and

negatively correlated with the E/A (Fig. 1C and D, respectively).

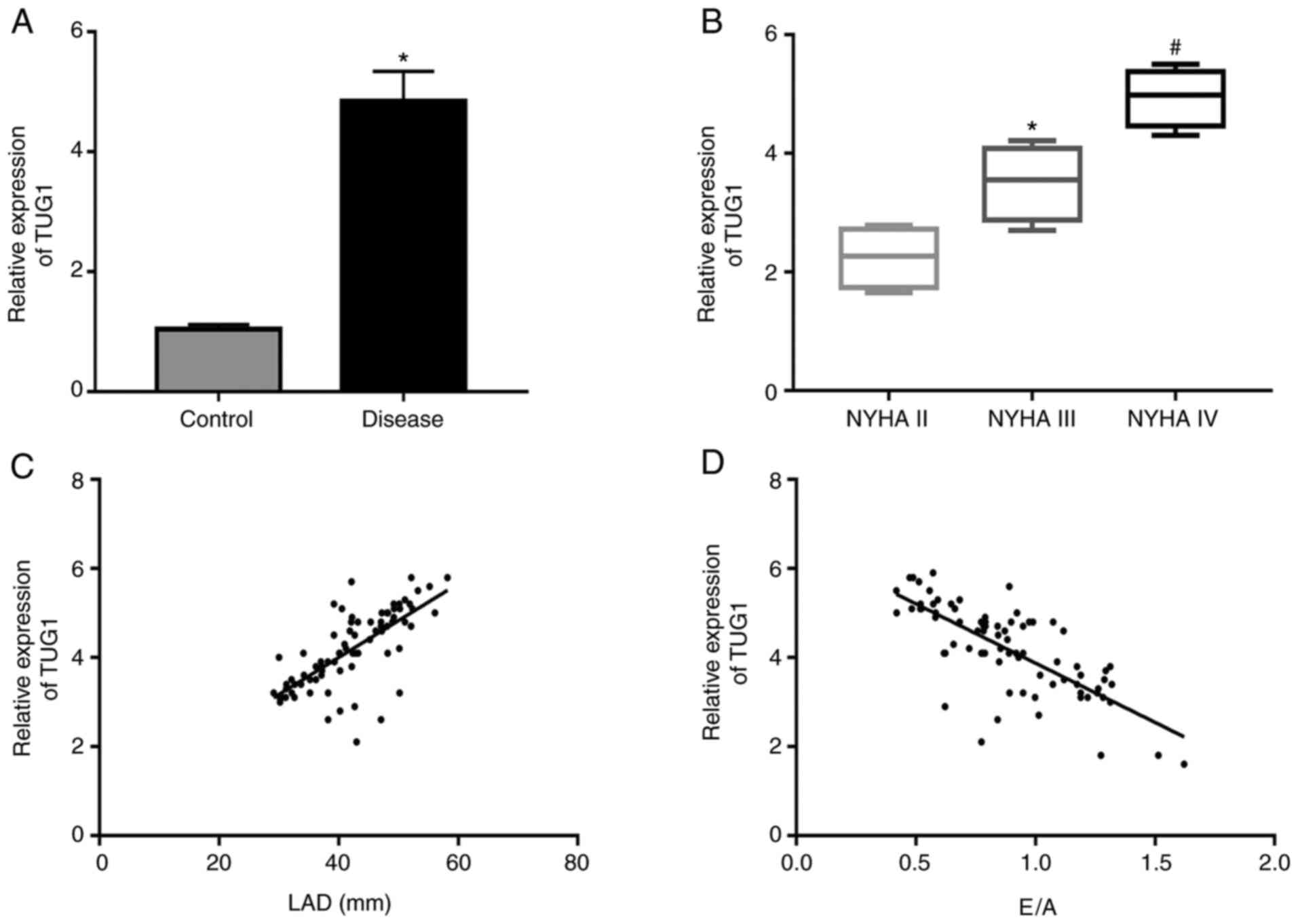

Serum TUG1 is elevated in hypertensive

patients with HFPEF

The levels of TUG1 in the serum of patients were

then assessed using RT-qPCR. The levels of TUG1 were significantly

enhanced in the observation group in comparison with those in the

control group (Fig. 2A).

Furthermore, TUG1 expression levels were significantly augmented

with the increase in the severity degree of HF (Fig. 2B). Spearman's correlation analysis

demonstrated that TUG1 was positively correlated with the LAD and

negatively correlated with the E/A (Fig. 2C and D, respectively).

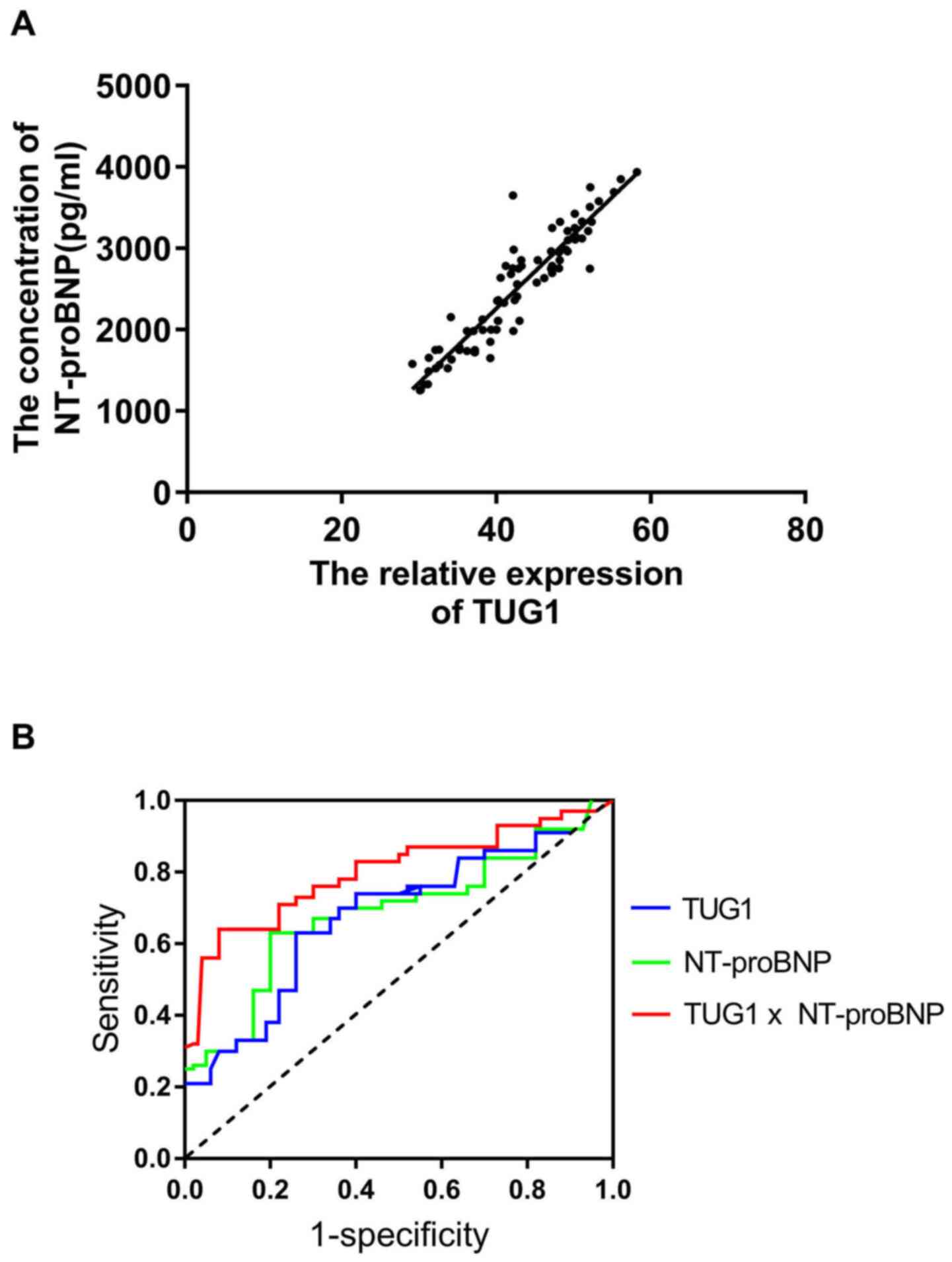

TUG1 and NT-proBNP are useful

diagnostic biomarkers for HFPEF in a hypertensive population

A positive correlation between the serum levels of

TUG1 and NT-proBNP was confirmed (Fig.

3A). ROC curve analysis suggested that TUG1 and NT-proBNP are

useful biomarkers for the diagnosis of HFPEF among subjects with

hypertension, with area under the curve (AUC) values of 0.73 (95%

CI, 0.67-0.79; cut-off value, 0.43) and 0.76 (95% CI: 0.71-0.85;

cut-off value, 0.45). In addition, the combination of the two

parameters slightly improved the diagnostic power, with an AUC of

0.83 (95% CI, 0.74-0.89; cut-off value, 0.48).

| Figure 3TUG1 and NT-proBNP may be useful

biomarkers for the diagnosis of HFPEF in a hypertensive population.

(A) A positive correlation was confirmed between the serum levels

of TUG1 and NT-proBNP in hypertensive patients with hypertension

and with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (r=0.823,

P<0.05). (B) Receiver operating characteristic curves for

evaluating the ability of TUG1, NT-proBNP and their combination to

identify patients with heart failure with preserved ejection

fraction in a hypertensive population. TUG1 had an AUC value of

0.73 (95% CI, 0.67-0.79; cut-off value, 0.43), NT-proBNP had an AUC

value of 0.76 (95% CI, 0.71-0.85; cut-off value, 0.45) and the

combination of the two parameters had an AUC value of 0.83 (95% CI,

0.74-0.89; cut-off value, 0.48). HFPEF, heart failure with

preserved ejection fraction; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-brain

natriuretic peptide; TUG1, taurine upregulated 1; AUC, area under

the curve. |

Discussion

HFPEF is caused by decreased cardiac smooth muscle

relaxation during the process of left ventricular diastole. When

HFPEF occurs, the myocardial compliance is impaired and the

diastolic capacity of the ventricular muscle is weakened, resulting

in decreased filling function of the left ventricle during the

diastolic period and decreased output per stroke, which then leads

to an increase of the filling pressure at the end of the diastolic

period of the left ventricle, finally inducing HF (16). HFPEF has numerous causes and the

most common etiology is hypertension in the elderly (17). By determining the two-dimensional

ultrasonic diagnostic index, the size of each atrioventricular

cavity of the heart may be rapidly measured, which is helpful for

the diagnosis of HFPEF. Blood flow Doppler and tissue Doppler are

sensitive for the measurement of mitral valve diastole, systolic

blood flow velocity and mitral annulus root movement velocity

(18). In the present study, it was

observed that the LAD was significantly thicker in hypertensive

patients with HFPEF compared with that in the control group of

patients with hypertension. Furthermore, the E/A was markedly

decreased in these patients. NT-proBNP is a precursor of BNP, which

is mainly synthesized and secreted by ventricular myocytes. It may

reflect the functions of left ventricular systole and remodeling

and is of important diagnostic value for HF (19). The present results suggested that

the concentration of NT-proBNP was significantly elevated in

hypertensive patients with HFPEF compared with that in the control

group of patients with hypertension. The NYHA classification is the

basis for the classification of the severity of clinical HF and the

major criterion for judging the severity of the disease in the

clinic (20). The present results

indicated that NT-proBNP levels were increased with the severity

degree of HF. Furthermore, Spearman's correlation analysis

demonstrated the NT-proBNP concentration was positively correlated

with the LAD and negatively correlated with the E/A. These data

suggested that NT-proBNP may be used as one of the hematological

diagnostic indexes for hypertensive patients with HFPEF.

As a novel lncRNA, TUG1 has been reported to

participate in the development of cardiac diseases, including

cardiac hypertrophy (21), ischemic

myocardial injury (22) and

atherosclerosis (23). Therefore,

in the present study, the role of TUG1 in HF was investigated and

it was determined that the serum levels of TUG1 in hypertensive

patients with HFPEF were significantly higher than those in

hypertensive controls. In addition, TUG1 levels were positively

correlated with the LAD and negatively correlated with the E/A. A

positive correlation was confirmed between the serum levels of TUG1

and NT-proBNP. Furthermore, ROC curve analysis revealed that the

plasma levels of TUG1 and NT-proBNP are useful biomarkers for the

diagnosis of HFPEF among hypertensive subjects and the combination

of these two indexes slightly improved the diagnostic power.

In conclusion, the present study indicated that the

NT-proBNP concentration and TUG1 expression levels were increased

in the serum of hypertensive patients with HFPEF. Furthermore, TUG1

and NT-proBNP were determined to be useful plasma biomarkers for

the diagnosis of HFPEF among hypertensive subjects.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the present

study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

RJ and BL performed the experiments. SZ designed

experiments analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. RJ and SZ

can authenticate the raw data. All authors read and approved the

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Written informed consent was provided by all study

participants. The present study was approved by the ethics

committee of The First Affiliated Hospital of Jinzhou Medical

University (Jinzhou, China).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Savarese G and Lund LH: Global public

health burden of heart failure. Card Fail Rev. 3:7–11.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Benjamin EJ, Muntner P, Alonso A,

Bittencourt MS, Callaway CW, Carson AP, Chamberlain AM, Chang AR,

Cheng S, Das SR, et al: Heart disease and stroke statistics-2019

update: A report from the american heart association. Circulation.

139:e556–e528. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J,

Casey DE Jr, Drazner MH, Fonarow GC, Geraci SA, Horwich T, Januzzi

JL, et al: 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart

failure: A report of the American college of cardiology

foundation/American heart association task force on practice

guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 62:e147–e239. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Owan TE, Hodge DO, Herges RM, Jacobsen SJ,

Roger VL and Redfield MM: Trends in prevalence and outcome of heart

failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med.

355:251–259. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Paul B, Soon KH, Dunne J and De Pasquale

CG: Diagnostic and prognostic significance of plasma

N-terminal-pro-brain natriuretic peptide in decompensated heart

failure with preserved ejection fraction. Heart Lung Circ.

17:497–501. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Geisler S and Coller J: RNA in unexpected

places: Long non-coding RNA functions in diverse cellular contexts.

Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 14:699–712. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Mattick JS and Rinn JL: Discovery and

annotation of long noncoding RNAs. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 22:5–7.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Shi Q and Yang X: Circulating MicroRNA and

long noncoding RNA as biomarkers of cardiovascular diseases. J Cell

Physiol. 231:751–755. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Kumarswamy R, Bauters C, Volkmann I, Maury

F, Fetisch J, Holzmann A, Lemesle G, de Groote P, Pinet F and Thum

T: Circulating long noncoding RNA, LIPCAR, predicts survival in

patients with heart failure. Circ Res. 114:1569–1575.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Gao L, Liu Y, Guo S, Yao R, Wu L, Xiao L,

Wang Z, Liu Y and Zhang Y: Circulating long noncoding RNA HOTAIR is

an essential mediator of acute myocardial infarction. Cell Physiol

Biochem. 44:1497–1508. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Wang F, Su X, Liu C, Wu M and Li B:

Prognostic value of plasma long noncoding RNA ANRIL for in-stent

restenosis. Med Sci Monit. 23:4733–4739. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Young TL, Matsuda T and Cepko CL: The

noncoding RNA taurine upregulated gene 1 is required for

differentiation of the murine retina. Curr Biol. 15:501–512.

2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, Bueno H,

Cleland JGF, Coats AJS, Falk V, González-Juanatey JR, Harjola VP,

Jankowska EA, et al: 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and

treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for

the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of

the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)developed with the special

contribution of the heart failure association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur

Heart J. 37:2129–2200. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Elasfar A: Correlation between plasma

N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide levels and changes in New

York Heart Association functional class, left atrial size, left

ventricular size and function after mitral and/or aortic valve

replacement. Ann Saudi Med. 32:469–472. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Bhargava S, Ali A, Manocha A, Kankra M,

Das S and Srivastava LM: Homocysteine in occlusive vascular

disease: A risk marker or risk factor. Indian J Biochem Biophys.

49:414–420. 2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Di Palo KE and Barone NJ: Hypertension and

heart failure: Prevention, targets, and treatment. Heart Fail Clin.

16:99–106. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Fitzgibbons TP, Meyer TE and Aurigemma GP:

Mortality in diastolic heart failure: An update. Cardiol Rev.

17:51–55. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Negi SI, Jeong EM, Shukrullah I, Raicu M

and Dudley SC Jr: Association of low plasma adiponectin with early

diastolic dysfunction. Congest Heart Fail. 18:187–191.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Poss J, Link A and Bohm M: Acute and

chronic heart failure in light of the new ESC guidelines. Herz.

38:812–820. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar : (In German).

|

|

21

|

Zou X, Wang J, Tang L and Wen Q: LncRNA

TUG1 contributes to cardiac hypertrophy via regulating miR-29b-3p.

In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 55:482–490. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Su Q, Liu Y, Lv XW, Dai RX, Yang XH and

Kong BH: LncRNA TUG1 mediates ischemic myocardial injury by

targeting miR-132-3p/HDAC3 axis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol.

318:H332–H344. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Li FP, Lin DQ and Gao LY: LncRNA TUG1

promotes proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cell and

atherosclerosis through regulating miRNA-21/PTEN axis. Eur Rev Med

Pharmacol Sci. 22:7439–7447. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|