Introduction

Synovial hemangioma is a rare benign tumor that

occurs most frequently in the knee in children and young adults

(1-3).

There are four histological subtypes: venous, venous vascular

malformation, cavernous, and capillary hemangiomas (4). Since the clinical presentation and

radiological findings of synovial hemangiomas are nonspecific,

there is often a long period from the onset to the diagnosis. In

some cases, the diagnosis is made after osteoarthritis and

cartilage damage have already occurred (5). After the diagnosis, an open or

arthroscopic resection is performed in most cases, and good

postoperative outcomes have been reported (6). Because of the rarity of synovial

hemangiomas, most reports described a single clinical case, and

they highlighted the rarity of this tumor. In this report, we

describe a series of nine patients with synovial hemangiomas and

the results of our retrospective analysis of the correlation

between patients' pathological and radiological characteristics.

Moreover, the usefulness of diffusion-weighted image (DWI) in the

differentiation of synovial hemangioma from diffuse-type

tenosynovial giant cell tumor (D-TSGCT) (formerly named pigmented

villonodular synovitis) is also discussed.

Patients and methods

After obtaining institutional review board approval,

we identified the nine patients (five males and four females) who

were each diagnose with synovial hemangioma of a knee and treated

at Fukushima Medical University Hospital (Fukushima, Japan) or

Fukushima Red Cross Hospital (Fukushima, Japan) during the period

between January 1998 and December 2021. The patients' median age at

surgery was 22 years (range 1-43 yrs). We retrospectively reviewed

the patients' clinical presentations, radiological findings,

surgical procedures, postoperative courses, and pathological

findings.

Results

Clinical presentations and tumor

locations

Table I summarizes

the patients' clinical characteristics. All nine patients had

persistent knee pain. Three patients also had a swollen knee with

intra-articular hemorrhage. The duration of symptoms from their

onset to the patient's initial visit varied, ranging from 1 day to

10 years. One patient had multiple lesions (Patient #6). Among the

other eight cases, the synovial hemangioma was located in the

suprapatellar bursa in two patients (#2 and #4), in the subcapsular

fat body in four (Patients #1, #5, #7, and #9), and anterior to the

femoral condyle localized in two (Patients #3 and #8).

| Table IPatients' clinical

characteristics. |

Table I

Patients' clinical

characteristics.

| Patient no. | Age, years | Sex | Symptom | Intra-articular

hemorrhage | Symptom duration

(until first visit) | Affected side | Location |

|---|

| 1 | 1 | F | Pain, swelling | + | 3 months | Right | Infrapatella and

suprapatellar fat-pad |

| 2 | 11 | F | Pain | - | 3 months | Right | Suprapatellar

bursa |

| 3 | 14 | M | Pain | - | 1 month | Left | In front of the

medial condyle of femur |

| 4 | 17 | F | Pain | - | 0.5 months | Left | Suprapatellar

bursa |

| 5 | 22 | M | Pain, Swelling | + | 1 day | Right | Infra patella

fat-pad |

| 6 | 24 | M | Pain | - | 10 years | Left | Inter condylar fossa,

infra patellar fat-pad and posterolateral capsule |

| 7 | 28 | M | Pain | - | 1 year | Right | Suprapatella

fat-pad |

| 8 | 34 | F | Pain | - | 6 months | Left | In front of the

medial condyle of femur |

| 9 | 43 | M | Pain, swelling | + | 1 months | Left | Infrapatellar

fat-pad |

Radiological findings

On plain radiographs, intra-articular calcification

consistent with phleboliths was observed in two patients.

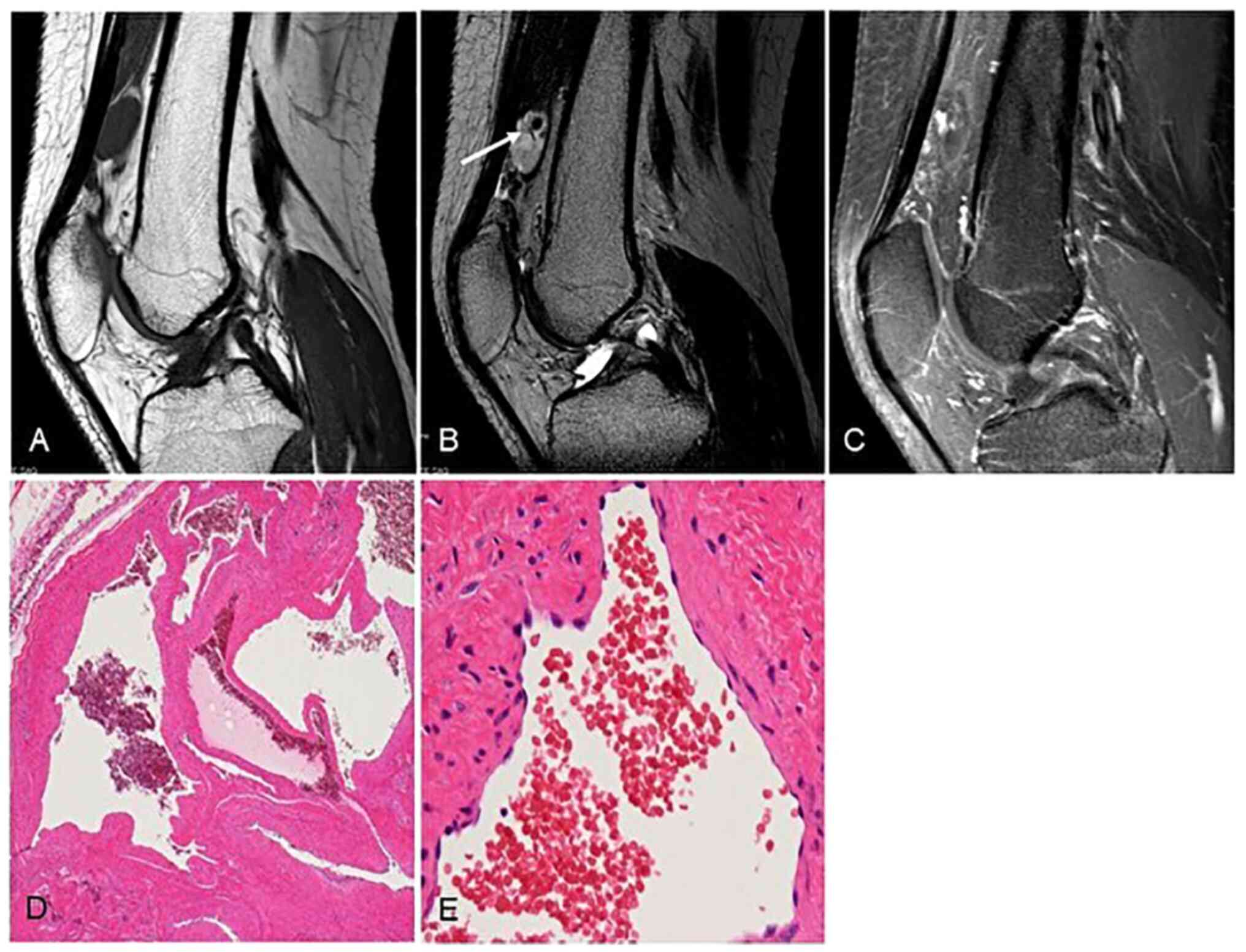

T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed low signal

intensity with and without small signal voids in six patients and

two patients, respectively, and high signal intensity without

signal voids in the other patient (Patient #7). In all nine

patients, T2-weighted imaging (WI) showed high signal intensity

containing small signal voids and intra-tumoral septum comparable

to joint fluid and fat. In the present cases, the synovial

hemangiomas showed a small honeycomb pattern with a thin septum and

a lobulated pattern. T2*-WI showed high intensity, containing low

intensity area that could be post-hemorrhagic changes. Gadolinium

enhancement was performed for four patients, with heterogeneous

staining of the tumor (Figs. 1 and

2). The maximum tumor diameter

ranged from 1.5 to 7.2 cm (Table

II). MRI findings of D-TSGCT show nodular and extensive

synovial proliferation, joint effusion, and bone erosion.

Hemosiderin deposition in the proliferative synovial tissue results

in point-like low signal on T1-weighted and T2-weighted images and

extensive low-signal changes within the proliferative synovium.

These may be differentiation from synovial hemangioma.

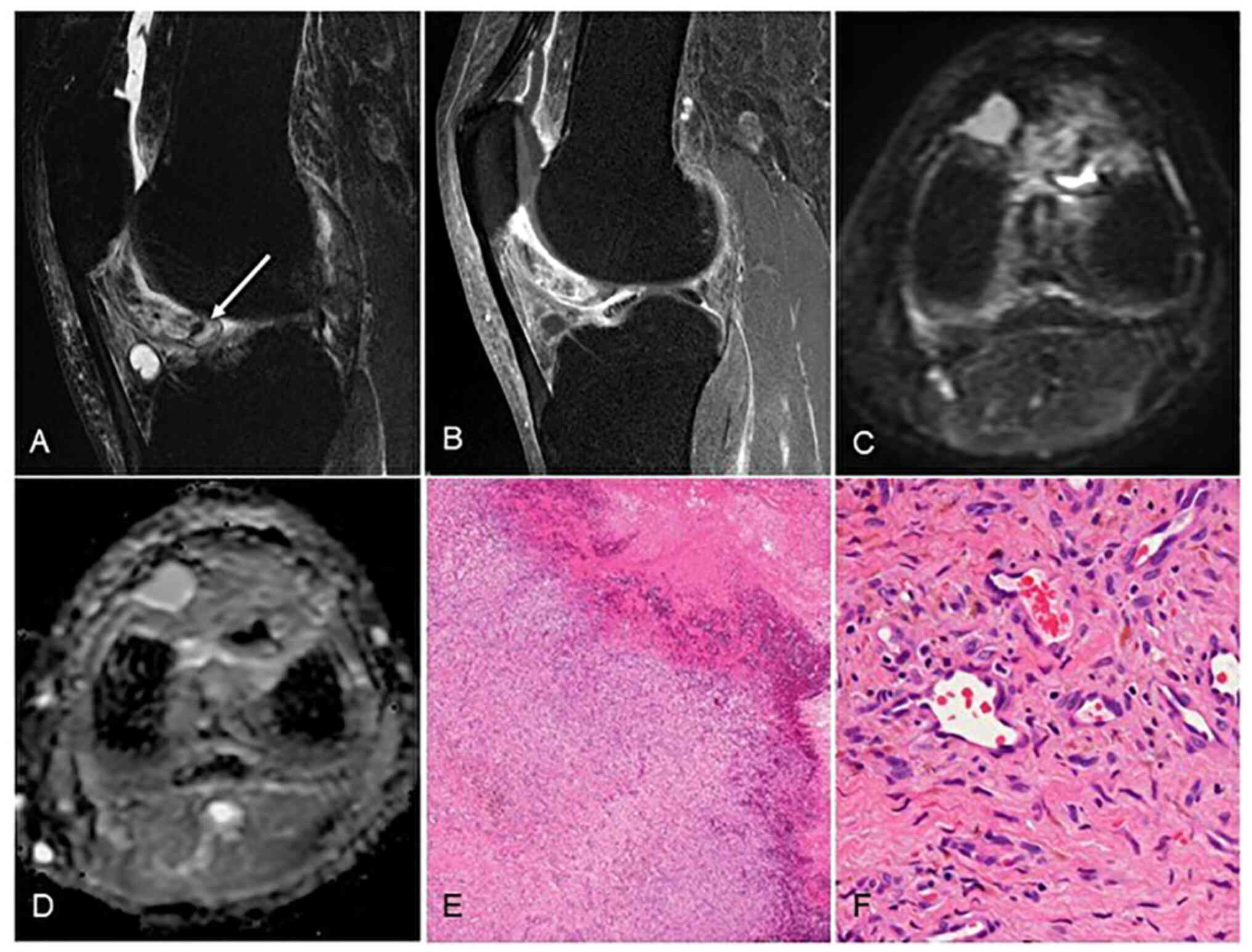

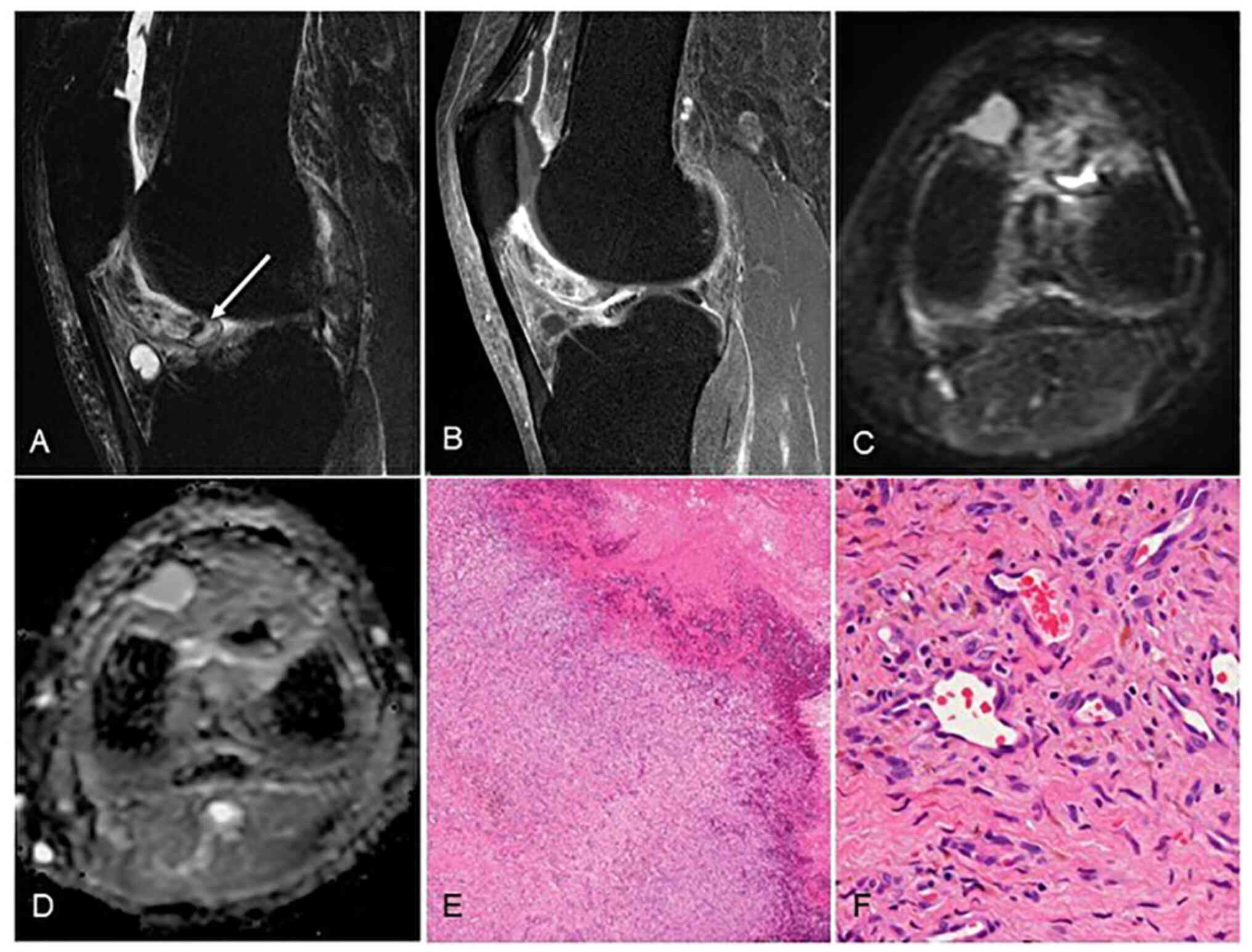

| Figure 2Capillary hemangioma (patient #9). (A)

On magnetic resonance imaging, T2-weighed fat-suppression imaging

showed high signal intensity containing small signal void (arrow).

(B) Gadolinium enhancement showed heterogeneous staining of the

tumor. (C) DWI showed low-signal intensity in the tumor and (D)

high apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) value of 2,184/mm2/sec.

Microscopic findings show small vascular lumen, which was less

likely to form thrombus or phleboliths, and this tumor was

difficult to diagnose without microscopic confirmation: (E)

low-power field (magnification, x20), H-E staining; (F) high-power

field, (magnification, x200), H-E staining. H-E, hematoxylin and

eosin. |

| Table IIRadiological characteristics of the

tumor. |

Table II

Radiological characteristics of the

tumor.

| Patient no. | Size, cm | Plain

radiography | T1-weighted

image | T2*-weighted

image | Gadolinium-

enhanced, T1- weighted fat- suppression image | DWI

ADC-mapping |

|---|

| 1 | 3.7x2.4x1.9 | Phlebolith | Low intensity | High intensity,

containing low intensity area of hemorrhage | - | - |

| 2 | 3.0x2.8x1.5 | Normal | Low intensity,

containing small signal voids | - | - | - |

| 3 | 7.2x4.1x0.9 | Cortical erosion,

phlebolith | Low intensity,

containing small signal voids | - | Heterogeneous

enhancement | - |

| 4 | 3.1x2.1x1.1 | Normal | Low intensity | - | Heterogeneous

enhancement | - |

| 5 | 1.5x0.8 | Normal | Low intensity,

containing small signal voids | - | - | - |

| 6 |

Diffuse/multiple | Normal | Low intensity,

containing small signal voids | - | - | - |

| 7 | 3.8x3.3x1.1 | Normal | High intensity,

containing small signal voids | - | Heterogeneous

enhancement | - |

| 8 | 4x3.5x1.1 | Normal | Low intensity,

containing small signal voids | - | - | - |

| 9 | 4.7x5.9x2.9 | Normal | Low intensity,

containing small signal voids | High intensity,

containing low intensity area of hemorrhage | Heterogeneous

enhancement | ADC value 2184 |

Surgical procedures and postoperative

courses

The surgery was performed without a preoperative

biopsy in all nine patients. The duration from the patient's

initial visit to the surgery ranged from 1 to 9 months. Open

resection (n=2 patients), arthroscopic resection (n=3), and

conversion to open resection after arthroscopy (n=4) were

performed. In one of the two patients who underwent an open

resection (Patient #6) and in one of the patients who underwent

arthroscopic resection (Patient #4), additional resections for

local recurrence were performed.

The average postoperative follow-up period from the

final surgery was 17.2 months, with the longest follow-up period

being 60 months. After the final surgery, none of the patients

developed postoperative recurrence, and their knee pain had

disappeared at the final follow-up (Table III).

| Table IIISurgical procedure, pathological

diagnoses and oncological prognosis. |

Table III

Surgical procedure, pathological

diagnoses and oncological prognosis.

| Patient no. | Duration from

initial visit to surgery, months | Procedure | Pathological

sub-type | Follow-up period,

months | Prognosis |

|---|

| 1 | 45 | Open resection

after arthroscopy | Cavernous

hemangioma | 11 | NED |

| 2 | 5 | Arthroscopic

resection | Capillary

hemangioma | 12 | NED |

| 3 | 9 | Open resection | Cavernous

hemangioma | 1 | NED |

| 4 | 2 | 1st surgery:

Arthroscopic resection 2nd surgery: Open resection | Venous

hemangioma | 9 | NEDa |

| 5 | 3 | Arthroscopic

resection | Capillary

hemangioma | 6 | NED |

| 6 | 1 | 1st surgery: Open

resection 2nd surgery: Arthroscopic resection | Venous

hemangioma | 41 | NEDa |

| 7 | 3 | Open resection

after arthroscopy | Cavernous

hemangioma | 13 | NED |

| 8 | 7 | Open resection | Venous

hemangioma | 2 | NED |

| 9 | 2 | Open resection

after arthroscopy | Capillary

hemangioma | 60 | NED |

Pathological findings

Based on the pathological findings of surgical

specimens, the diagnoses were venous hemangioma (Fig. 1), capillary hemangioma (Fig. 2), cavernous hemangioma (Fig. 3), in three patients each. Venous

hemangiomas have thickened vascular smooth muscle and a dilated

vascular lumen. Because of slow blood flow, they are prone to

forming thrombi and phleboliths. Capillary hemangiomas have a small

vascular lumen and are less likely to form thrombus or phleboliths.

Microscopy should be used for diagnosis. In cavernous hemangiomas

unlike the venous hemangiomas, vascular smooth muscle is absent.

The size of the intra-tumoral vascular lumen differs depending on

the subtype of hemangioma.

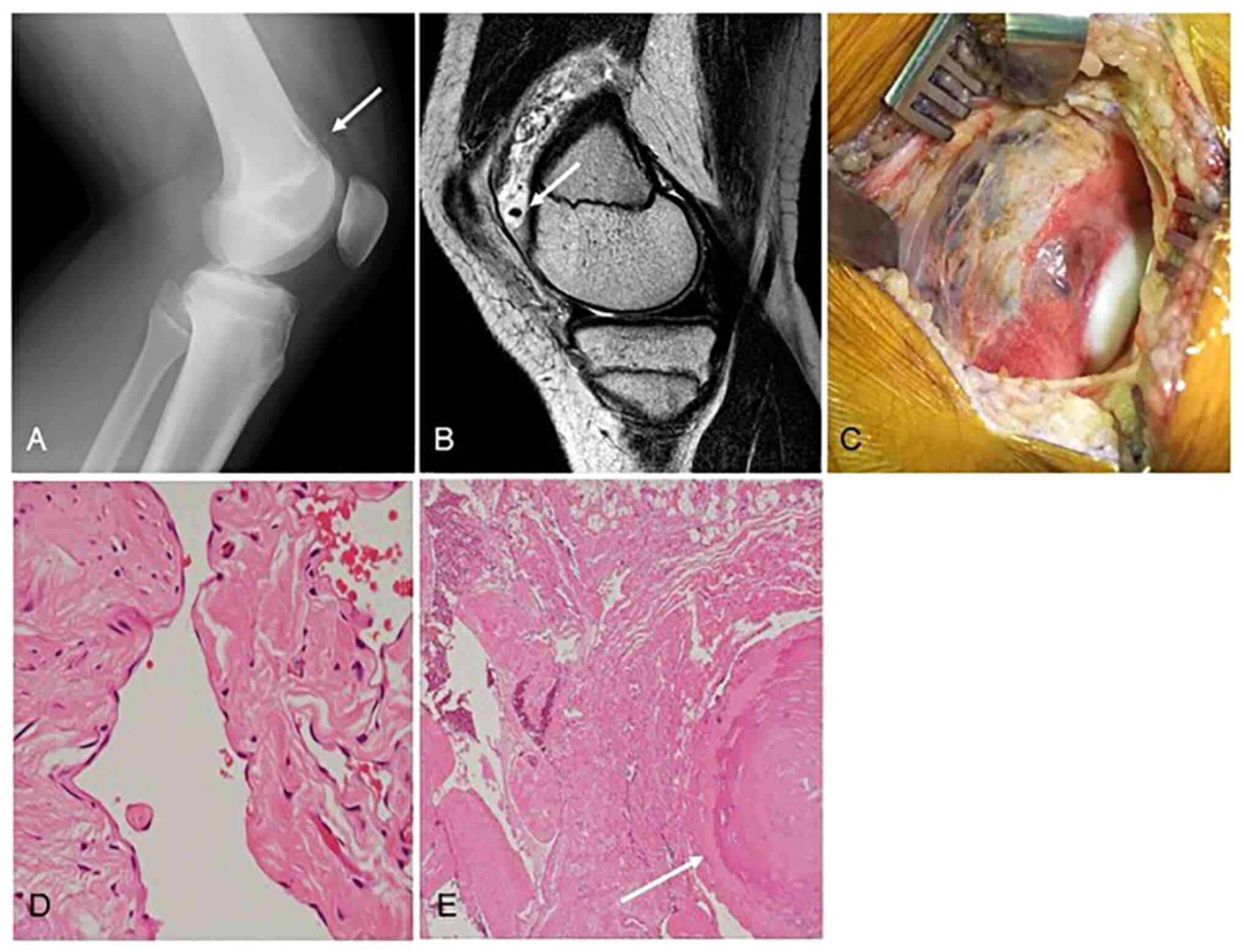

Representative case (Patient #3)

A 14-year-old boy presented with a 1-month history

of continuous left knee pain. Plain radiographs of his left knee

joint showed an intra-articular calcification consistent with

phlebolith (Fig. 3A). MRI revealed

a mass with high signal intensity containing a small signal void on

T2-WI (sagittal plane) (Fig. 3B).

From the radiological findings, we initially diagnosed a synovial

hemangioma of the knee. Since the patient's left knee pain did not

improve, we decided to perform the surgical resection 9 months

after the initial visit. Because of the size of the tumor, open

resection was selected. Intraoperative gross findings showed a dark

red tumor covered by the synovium on the surface of lateral condyle

of the femur (Fig. 3C), and the

tumor was completely resected. The microscopic findings of the

surgical specimen showed expanded blood lumens lacking vascular

smooth muscle (Fig. 3D). The

formation of thromboses and phleboliths caused by slow blood flow

was easily identified (Fig. 3E).

The tumor was diagnosed as a cavernous SH. At 1 month after the

operation, the patient's symptom had completely resolved.

Discussion

Synovial hemangioma has accounted for 0.07% of all

soft tissue tumors and 0.78% of resected hemangiomas (7). Although it can occur in a variety of

joints, the most common location is the knee (1). Synovial hemangioma occurs most

frequently in children and young adults (1-3),

with male predominance. Since there is no specific clinical

presentation, there is often a long period between the onset and

the diagnosis (8). The most common

symptom is long-term persistent knee pain; other symptoms include a

limited range of motion, joint swelling, and nontraumatic

intra-articular hematoma. However, except in phases of

exacerbation, the presence of a synovial hemangioma does not limit

activities of daily living, and patients with this benign tumor

rarely visit a medical facility.

The clinical findings of synovial hemangioma are

similar to those of D-TSGCT and hemophilic arthropathy. Both may

cause sudden and non-traumatic intra-articular hemorrhage, and a

delayed diagnosis can thus lead to osteoarthritis and joint

function disuse (9). There are two

case reports of synovial hemangioma in which >40 years passed

from the onset of the disease until the final diagnosis (10,11).

In another report, a 67-year-old patient was diagnosed with a

synovial hemangioma after experiencing severe osteoarthritis; the

patient finally underwent a total knee arthroplasty (12). As a characteristic physical

examination finding, cutaneous hemangiomas have been reported to be

present in approx. 40% of patients with synovial hemangiomas in the

knee (1), but in the present

series there were no coexisting cutaneous lesions. A reported

average duration from the onset of symptoms until the diagnosis of

synovial hemangioma was 4.5 years (13). We were able to diagnose the disease

earlier, with an average duration of 4.18 months from onset to

diagnosis. When clinicians are diagnosing knee pain and/or

intra-articular hemorrhage in young patients, the possibility of

synovial hemangioma should be considered. Synovial hemangiomas are

expected to have good surgical outcomes with resection, but if left

undiagnosed for a long period of time, they can lead to

osteoarthritis and functional disability of the knee. Preoperative

imaging and intraoperative arthroscopic findings should confirm the

extent of the tumor and if adequate resection is possible,

arthroscopic resection should be used. If the tumor is difficult to

resect due to its location or size, the approach should be switched

to open. The present patient series includes a 1-year-old patient,

and surgery is recommended as soon as the diagnosis and

perioperative management are possible.

Plain radiography is usually the first radiological

examination conducted in patients who are suspected to have knee

pain and/or intra-articular hemorrhage. Plain radiography of a

synovial hemangioma typically shows no abnormality, but periosteal

reactions, osteolysis, osteopenia, intra-articular phleboliths,

osteoarthritis, or soft tissue swelling may be observed (1,2,14-18).

In the present patient series, we identified cortical erosion in

one case and intra-articular phleboliths in two cases, but these

findings were not specific for synovial hemangioma and could not be

used as diagnostic evidence. As in other soft tissue tumors, MRI

thus plays a more important role than plain radiography.

Compared to muscle tissue, an MRI evaluation of a

synovial hemangioma reveals low to iso-intensity on T1-WI and high

intensity on T2-WI, but no characteristic findings are seen on

fat-suppression imaging (19,20).

In the present patients, the synovial hemangiomas showed a small

honeycomb pattern with a thin septum and a lobulated pattern. Small

signal voids were also observed within the tumor in all nine

patients. Contrast-enhanced MRI was performed in four cases, and

gadolinium contrast showed heterogeneous enhancement only of the

septum and tumor margins, indicating a cystic-like structure. In

addition, a fibrous septum separated the tortuous vascular

component, which has been reported as one of the specific findings

of synovial hemangioma (21,22).

The size of the intra-tumoral vascular lumen differs

depending on the subtype of hemangioma. In a larger vascular lumen,

the blood flow becomes slower, and the contrast will be partial. It

was reported that large venous synovial hemangiomas showed high

signal intensity on T1-WI due to slow blood flow (20). Since synovial hemangiomas are

blood-rich tumors and are usually heterogeneously enhanced on

gadolinium contrast, the use of which helps distinguish these

tumors from cystic synovial hyperplasia (23), intra-articular hematoma, and joint

effusion (5,9,24,25).

However, it has been claimed that synovial hemangioma was correctly

diagnosed preoperatively in only 22% of cases (9,14).

The usefulness of contrast MRI had been supported for confirming

the localization and the extension of this tumor and detecting

local recurrence in the postoperative follow-up (5).

The pathological diagnosis of synovial hemangioma is

classified into the venous, arteriovenous, cavernous, and capillary

subtypes (4). Venous synovial

hemangiomas have thick vascular smooth muscle and a dilated

vascular lumen. Cavernous synovial hemangiomas also have a dilated

lumen, but unlike the venous subtype, they are differentiated by

the absence of smooth muscle in the vessel wall. In both of these

subtypes, the dilated lumen slows the blood flow and increases the

formation of a thrombus and/or phleboliths compared to the

capillary subtype, which has a smaller lumen. In the present

patient series, the presence of phleboliths was confirmed by plain

radiography and MRI in only two cases, both of which were the

cavernous subtype (Fig. 2). On the

other hand, capillary subtypes do not form a thrombus or

phleboliths, because of their narrow lumen. It is thus difficult to

diagnose capillary subtypes as hemangiomas without microscopic

confirmation.

An important differential diagnosis for synovial

hemangioma is D-TSGCT. Because of these two tumors' similarity in

age of onset and clinical presentation, D-TSGCT can be difficult to

distinguish in clinical practice. We noted that all nine of the

present patients' cases showed high signal intensity on T2-WI,

similar to circumferential fatty tissue and joint fluid. D-TSGCTs

usually show low-signal changes on T2-WI due to hemosiderin

deposition (26), whereas synovial

hemangiomas show high-signal changes on T2-WI (23,27,28).

This radiological difference in MRI between D-TSGCT and synovial

hemangioma is thought to be useful. However, T2-WI shows various

signal changes according to the presence of intra-articular

hemorrhage or fatty degeneration, leading to potential diagnostic

difficulty for synovial hemangioma on MRI.

In the present series, diffusion-weighted imaging

(DWI) was performed in one of the capillary subtype cases. The DWI

showed low signal intensity in the tumor and the high apparent

diffusion coefficient (ADC) value of 2,184/mm2/sec,

excluding the area with high signal intensity that was thought to

be post-hemorrhage changes (Fig.

3). Our review of eight cases of D-TSGCT of the knee that were

treated at our institute between 2006 and 2021 revealed that the

MRI findings revealed high signal intensity in DWI and the low mean

ADC value of 770/mm2/sec. Usually, in the case of a

solid or malignant tumor, cell proliferation causes an increase in

intracellular structures and a narrowing of the stroma, which

restricts the movement of water molecules, resulting in a low ADC

value. D-TSGCT is a synovial tumor with a high proliferation of

tumor cells and restricted movement of water molecules. Conversely,

synovial hemangioma is an angioproliferative disease in the

subsynovial layer, and thus the movement of water molecules in the

lumen and stroma is not as restricted as in D-TSGCT, and its ADC

may be higher than that in D-TSGCT. The present case series raises

the possibility that DWI and ADC values may be important

differentiators between synovial hemangioma and D-TSGCT. On the

other hand, the importance of enhanced MRI in diagnosing synovial

hemangioma was not observed in this series.

Despite their similar clinical findings, synovial

hemangiomas and D-TSGCT have different postoperative outcomes.

Although two of the nine patients in our present series had

postoperative recurrence because of an uncomplete resection,

synovial hemangiomas have been reported to have a postoperative

recurrence rate of 3.4% and a symptom persistence rate of 11.4%

(29). From our experience both

careful preoperative radiological examination and intraoperative

attention may reduce the risk of recurrence. D-TSGCT has a high

recurrence rate of 25-46% (30-32),

even when open resection is performed. When D-TSGCT is strongly

suspected from the MRI findings, surgeons should anticipate

circumferential invasion and perform a more aggressive resection of

the tumor. During the surgery, the identification of the

differences in gross findings between synovial hemangioma and

D-TSGCT is also useful in the final decision regarding the

aggressiveness of resection.

A limitation of the present study is that the

imaging conditions used for the MRI examinations were not

standardized, and DWI and ADC values were measured in only one

case. When we encounter patients with intra-articular tumors

including synovial hemangioma and D-TSGCT in the future, we will

obtain MRI findings under uniform conditions for the purpose of

increasing the number of cases for an additional review.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: This work was partially supported by JSPS KAKENHI

(grant no. JP21K09304).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current

study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

TS and MH participated in the design of study,

interpreted clinical data and drafted the manuscript. YK and HY

participated in the design of the clinical part of this study and

provided clinical data. OH analyzed and contributed to the

interpretation of the radiological findings. SY analyzed and

contributed to the interpretation of the pathological findings. SK

participated in the design of study and supervised the project. MH

and SK confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors

read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

This retrospective chart review study involving

human participants was in accordance with the ethical standards of

the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964

Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical

standards. This study was approved by the Ethical Review Committee

of Fukushima Medical University (approval no. 2022-36).

Patient consent for publication

This study is retrospective study. Patients were not

required to give informed consent to the study because the analysis

used anonymous clinical data that were obtained after each patient

agreed to treatment by written consent. We applied Opt-out method

to obtain consent on this study. The Opt-out was approved by the

Ethical Review Committee of Fukushima Medical University.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Moon NF: Synovial hemangioma of the knee

joint. A review of previously reported cases and inclusion of two

new cases. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 90:183–190. 1973.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Dalmonte P, Granata C, Fulcheri E,

Vercellino N, Gregorio S and Magnano G: Intra-articular venous

malformations of the knee. J Pediatr Orthop. 32:394–398.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Abe T, Tomatsu T and Tazaki K: Synovial

hemangioma of the knee in young children. J Pediatr Orthop B.

11:293–297. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Devaney K, Vinh TN and Sweet DE: Synovial

hemangioma: A report of 20 cases with differential diagnostic

considerations. Hum Pathol. 24:737–745. 1993.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Muramatsu K, Iwanaga R and Sakai T:

Synovial hemangioma of the knee joint in pediatrics: Our case

series and review of literature. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol.

29:1291–1296. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Cotton A, Flipo RM, Herbaux B, Gougeon F,

Lecomte-Houcke M and Chastanet P: Synovial haemangioma of the knee:

A frequently misdiagnosed lesion. Skeletal Radiol. 24:257–261.

1995.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Price NJ and Cundy PJ: Synovial hemangioma

of the knee. J Pediatr Orthop. 17:74–77. 1997.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Derzsi Z, Gurzu S, Jung I, László I, Golea

M, Nagy Ö and Pop TS: Arteriovenous synovial hemangioma of the

popliteal fossa diagnosed in an adolescent with history of

unilateral congenital clubfoot: Case report and a

single-institution retrospective review. Rom J Morphol Embryol.

56:549–552. 2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Lopez-Oliva CL, Wang EH and Cañal JP:

Synovial haemangioma of the knee: An under recognised condition.

Int Orthop. 39:2037–2040. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Holzapfel BM, Geitner U, Diebold J, Glaser

C, Jansson V and Dürr HR: Synovial hemangioma of the knee joint

with cystic invasion of the femur: A case report and review of the

literature. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 129:143–148. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Tohma Y, Mii Y and Tanaka Y: Undiagnosed

synovial hemangioma of the knee: A case report. J Med Case Rep.

13(231)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Suh JT, Cheon SJ and Choi SJ: Synovial

hemangioma of the knee. Arthroscopy. 19:E27–E30. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

De Gori M, Galasso O and Gasparini G:

Synovial hemangioma and osteoarthritis of the knee: A case report.

Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 48:607–610. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Akgün I, Kesmezacar H, Oğüt T and

Dervişoğlu S: Intra-articular hemangioma of the knee. Arthroscopy.

19(E17)2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Ramseier LE and Exner GU: Arthropathy of

the knee joint caused by synovial hemangioma. J Pediatr Orthop.

24:83–86. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Maeyama A, Saeki K, Hamasaki M, Kato Y and

Naito M: Deformation of the patellofemoral joint caused by synovial

hemangioma: A case report. J Pediatr Orthop B. 23:346–349.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Pinar H, Bozkurt M, Baktiroglu L and

Karaoğlan O: Intra-articular hemangioma of the knee with meniscal

and bony attachment. Arthroscopy. 13:507–510. 1997.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Watanabe S, Takahashi T, Fujibuchi T,

Komori H, Kamada K, Nose M and Yamamoto H: Synovial hemangioma of

the knee joint in a 3-year-old girl. J Pediatr Orthop B.

19:515–520. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Llauger J, Monill JM, Palmer J and Clotet

M: Synovial hemangioma of the knee: MRI findings in two cases.

Skeletal Radiol. 24:579–581. 1995.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Hospach T, Langendörfer M, Kalle TV,

Tewald F, Wirth T and Dannecker GE: Mimicry of lyme arthritis by

synovial hemangioma. Rheumatol Int. 31:1639–1643. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Larbi A, Viala P, Cyteval C, Snene F,

Greffier J, Faruch M and Beregi JP: Imaging of tumors and

tumor-like lesions of the knee. Diagn Interv Imaging. 97:767–777.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Narváez JA, Narváez J, Aguilera C, De Lama

E and Portabella F: MR imaging of synovial tumors and tumor-like

lesions. Eur Radiol. 11:2549–2560. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Barakat MJ, Hirehal K, Hopkins JR and

Gosal HS: Synovial hemangioma of the knee. J Knee Surg. 20:296–298.

2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

De Filippo M, Rovani C, Sudberry JJ, Rossi

F, Pogliacomi F and Zompatori M: Magnetic resonance imaging

comparison of intra-articular cavernous synovial hemangioma and

cystic synovial hyperplasia of the knee. Acta Radiol. 47:581–584.

2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Greenspan A, Azouz EM, Matthews J II and

Décarie JC: Synovial hemangioma: Imaging features in eight

histologically proven cases, review of the literature, and

differential diagnosis. Skeletal Radiol. 24:583–590.

1995.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Sanghi AK, Ly JQ, McDermott J and Sorge

DG: Synovial hemangioma of the knee: A case report. Radiol Case

Rep. 2:33–36. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Mandelbaum BR, Grant TT, Hartzman S,

Reicher MA, Flannigan B, Bassett LW, Mirra J and Finerman GA: The

use of MRI to assist in diagnosis of pigmented villonodular

synovitis of the knee joint. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 231:135–139.

1988.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Greenspan A, McGahan JP, Vogelsang P and

Szabo RM: Imaging strategies in the evaluation of soft-tissue

hemangiomas of the extremities: Correlation of the findings of

plain radiography, angiography, CT, MRI, and ultrasonography in 12

histologically proven cases. Skeletal Radiol. 21:11–18.

1992.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Staals EL, Ferrari S, Donati DM and

Palmerini E: Diffuse-type tenosynovial giant cell tumour: Current

treatment concepts and future perspectives. Eur J Cancer. 63:34–40.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Schwartz HS, Unni KK and Pritchard DJ:

Pigmented villonodular synovitis. A retrospective review of

affected large joints. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 247:243–255.

1989.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Johansson JE, Ajjoub S, Coughlin LP, Wener

JA and Cruess RL: Pigmented villonodular synovitis of joints. Clin

Orthop Relat Res. 163:159–166. 1982.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Byers PD, Cotton RE, Deacon OW, Lowy M,

Newman PH, Sissons HA and Thomson AD: The diagnosis and treatment

of pigmented villonodular synovitis. J Bone Joint Surg Br.

50:290–305. 1968.PubMed/NCBI

|