Introduction

As the prevalence of kidney stone disease rises, a

number of patients will need a minimally invasive procedure to

remove kidney stones. In the 1970s, percutaneous nephrolithotomy

(PCNL) was introduced as a less invasive option for kidney stone

removal and it underwent additional development in the following

years (1). However, extracorporeal

shock wave lithotripsy was introduced in the early 1980s,

decreasing PCNL frequency. Recent years have seen a redefining of

the function of PCNL for treating urolithiasis, as clinical

experience with ESWL has highlighted its limits (1). Nowadays, PCNL is a ubiquitous

technique. In a recent survey by Jiang et al (2), ~80.5% of urologists in China practice

PCNL and 96.2% said they like to perform it. According to the

European Association of Urology, PCNL is recommended as the

first-line treatment for kidney stones >2 cm and/or staghorn

stones (3).

Technical advances have led to a significant

reduction in the morbidity and mortality of this surgical

technique. However, PCNL is not a risk-free intervention. According

to Sharma et al (4), the

rate of complications varies considerably, being between 3-83%. The

most common are bleeding, pneumothorax, hydro/hemothorax, urinary

fistula, pleural effusion and urosepsis. Although postoperative

fever can be encountered in ≤30% of patients who undergo PCNL,

urosepsis is diagnosed, according to Michel et al (5), in 0.9-4.7%. A number of authors have

studied the factors that could favor the appearance of sepsis

following PCNL, but the results are inconclusive. Postoperative

infection is a common complication that, if untreated, can result

in septic shock. According to Yang et al (6), the fatality rate for urinary septic

shock can range from 25-60%, advances rapidly and is challenging to

treat. There is currently no standard recommendation for the risk

factors connected to postoperative infection. Preoperative urine

culture positivity, stone bacterial culture positivity, stone

burden, female gender, elderly gender, diabetes mellitus and

urinary tract obstruction are the key factors that lead to

postoperative infection (6). The

purpose of the present study was to analyze the data from the

literature to date to help clinicians manage the risks of PCNL so

that they become minimal.

Materials and methods

The present study performed this meta-analysis using

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

(PRISMA) 2020 reporting guidelines (7). A systematic Medline (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and Embase

(https://www.embase.com/) databases search was

performed, using the following words: ‘PCNL’ [MeSH Terms] AND

[‘sepsis’ (All Fields) OR ‘PCNL’ (All Fields)] AND [‘septic shock’

(All Fields)] AND [‘urosepsis’ (MeSH Terms) OR ‘Systemic

inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS)’ (All Fields)].

Inclusion criteria

Due to the technological advances in endourology,

the present study searched articles published between 2012 and

2022. Non-English language articles and those for which the full

text was unavailable were excluded. The leading search, as well as

screening for eligibility of titles, abstracts and full-text

articles, was completed independently by two authors and any

discrepancies were solved by consensus.

The present study selected studies with a control

group (non-SIRS/sepsis) and analyzed elements that favored the

appearance of sepsis after urological maneuvers. These have been

patients' age, diabetes mellitus, preoperative pyuria, positive

preoperative urine culture, operative time-minutes, multitract and

body mass index (BMI).

Statistical analysis

Heterogeneity in PCNL's infectious complications

outcome rate was assessed using I2 statistics. Review

Manager (RevMan), Version 5.4.1, and The Cochrane Collaboration,

2020, (both Cochrane) were used to calculate the individual odds

ratios (OR), P-value and personal and pooled mean differences with

corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI). A P-value <0.05 has

been considered statistically significant. The mean difference was

used to compare the outcomes following PCNL from the infectious

complications point of view. While random-effect models are

considered less statistically powerful, they may produce more

logical estimates if absolute heterogeneity exists. Furthermore,

random-effects models may overestimate the extent of error

variance, whereas fixed-effects models may underestimate it. Due to

the heterogeneity of the included studies, a fixed effect size

would be very implausible. Therefore, a standard random effect

model was applied. Considering that all of the included studies

were observational, the risk of bias was assessed using the

Newcastle-Ottawa quality assessment scale.

Results

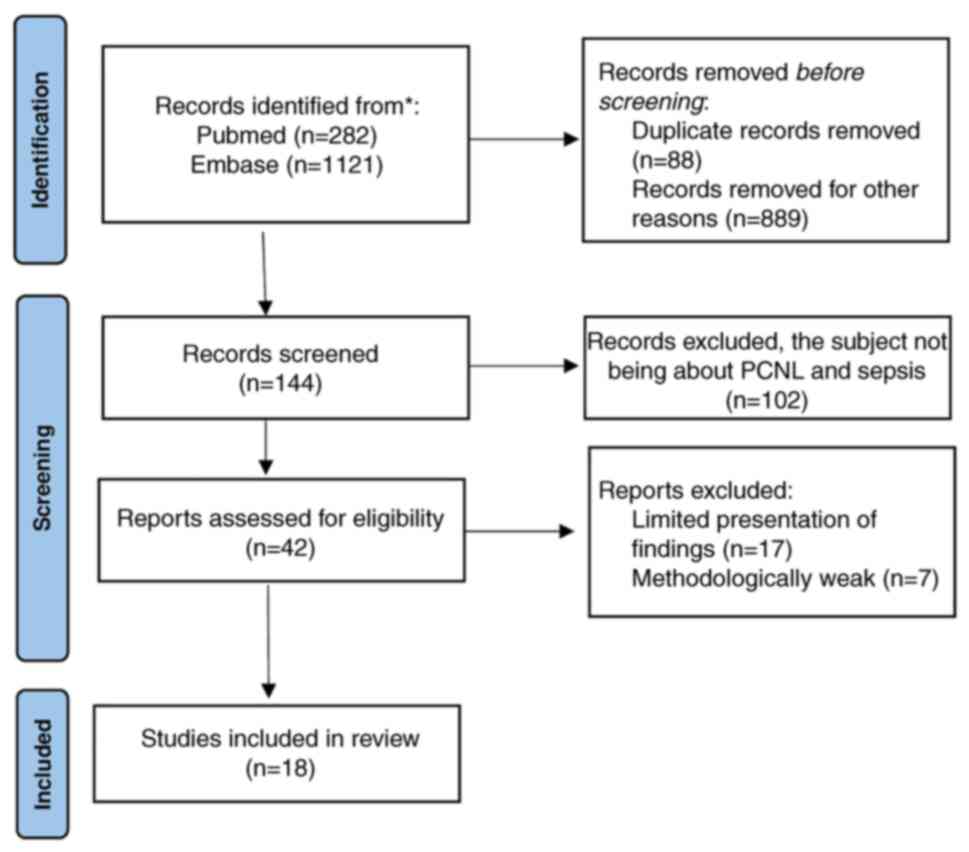

Of the 1,403 results of the search, only 18 articles

were selected. The flowchart of selection is shown in Fig. 1. The chosen studies, published

between 2014 and 2022, included a total of 7,507 patients on which

PCNL was performed. Details of the included studies are shown in

Table I.

| Table ICharacteristics of included

studies. |

Table I

Characteristics of included

studies.

| Author, year | Factor studied | Number of

patients | Analyzed

outcome | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Amier et al,

2022 | B,D,E,F | 171 | Sepsis | (8) |

| Chen et al,

2019 | A,B,C,D,E,F | 802 | Sepsis | (9) |

| Chhetri et

al, 2018 | A,C,D,E,F | 97 | Sepsis | (10) |

| He et al,

2018 | A,B,C,D,E,G | 1,030 | SIRS | (11) |

| Koras et al,

2015 | A,D,E,F,G | 303 | SIRS | (12) |

| Kumar et al,

2021 | B,D,E,F | 320 | SIRS | (13) |

| Liu et al,

2020 | A,B,D,E,F | 303 | SIRS | (14) |

| Liu et al,

2021 | A,C,D,F,G | 241 | Sepsis | (15) |

| Lorenzo Soriano

et al, 2019 | A,B,D,E,F,G | 203 | SIRS | (16) |

| Rashid and

Fakhulddin, 2016 | A,D,E, | 60 | Sepsis | (17) |

| Tabei et al,

2016 | A,B,C,D,E,F,G | 370 | SIRS | (18) |

| Tang et al,

2021 | A,B,C,D,E,F,G | 758 | SIRS + Sepsis | (19) |

| Teh and Tham,

2021 | B,C,D,F | 425 | Sepsis | (20) |

| Wang et al,

2020 | A,D,E,F,G | 843 | Sepsis | (21) |

| Wei et al,

2015 | A,B,E,F,G | 411 | SIRS | (22) |

| Xu et al,

2022 | A,B,C,D,E,F,G | 220 | SIRS | (23) |

| Yang et al,

2017 | A,B,E | 164 | SIRS | (24) |

| Zhu et al,

2020 | A,B,C,D,E,F,G | 786 | Sepsis | (25) |

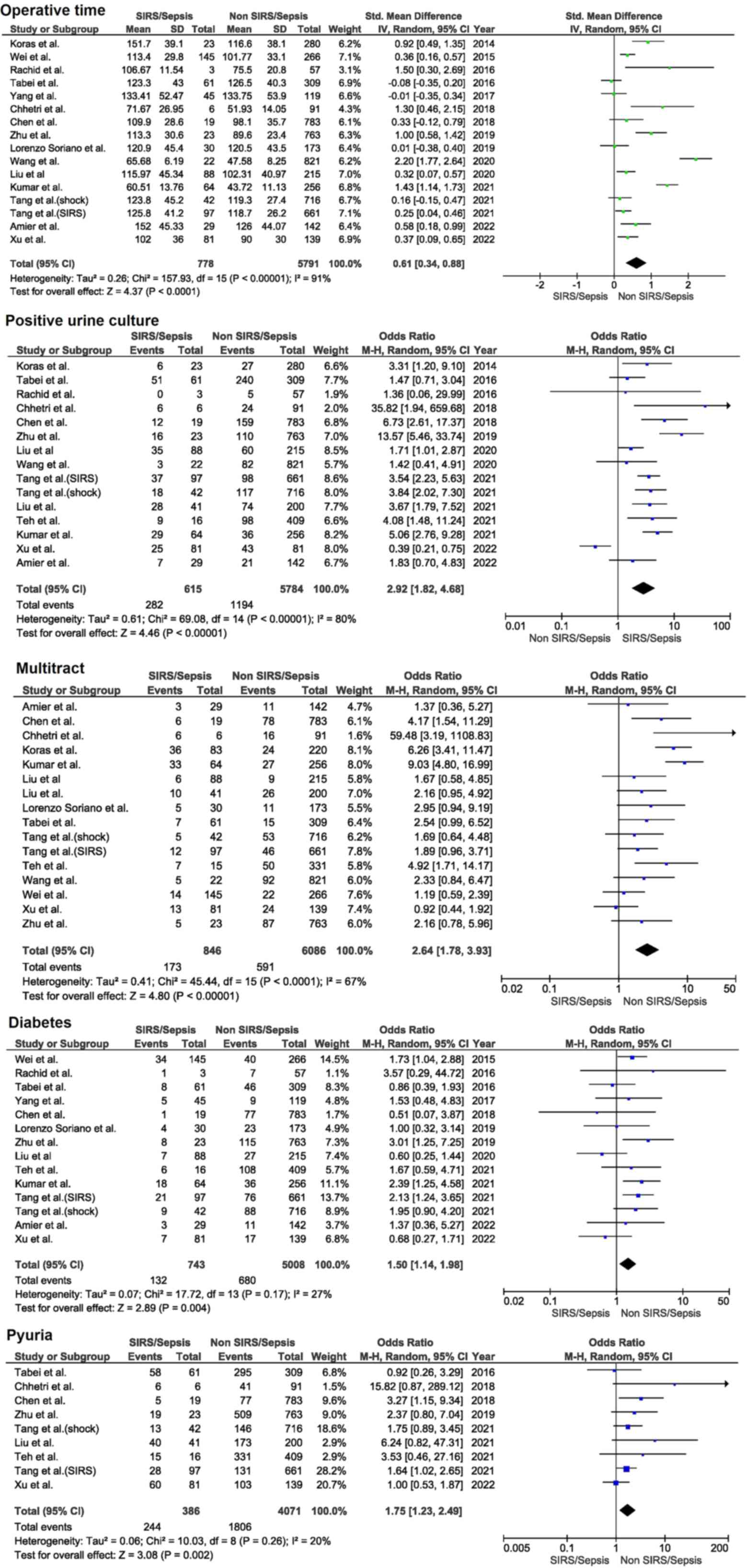

All authors applied antibiotic prophylaxis to all

patients and in some cases, the infection was treated

preoperatively in those with positive urine cultures. According to

the analysis of the present study, the operative time has been

significantly longer in patients who developed SIRS/sepsis

post-operatively (P=0.0001) with the highest heterogeneity

(I2=91%) compared with other factors. Patients with a

positive preoperative urine culture have a significantly higher

risk of developing SIRS/sepsis following PCNL (P=0.00001), OD=2.92

(1.82, 4.68) and there is also a high degree of heterogeneity

(I2=80%). Performing a multi-tract PCNL also increases

the incidence of postoperative SIRS/sepsis (P=0.00001), OD=2.64

(1.78, 3.93) and the heterogeneity was a little smaller

(I2=67%). Diabetes mellitus (P=0.004), OD=1.50 (1.14,

1.98), I2=27% and preoperative pyuria (P=0.002), OD=1.75

[1.23, 2.49], I2=20%, as shown in Fig. 2, were other factors that

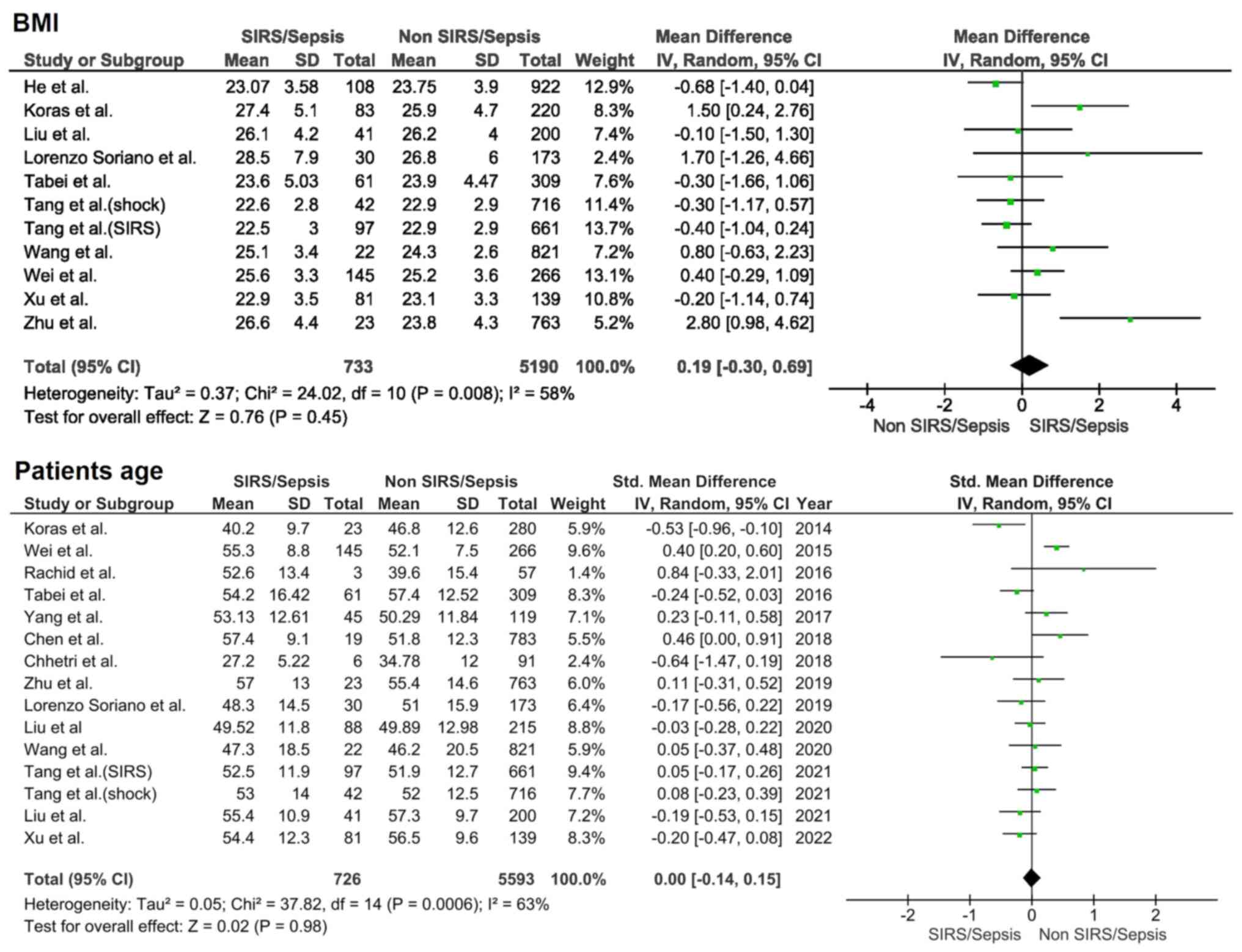

significantly influenced postoperative evolution. However, BMI and

patient's age did not influence the outcome; P=0.45,

I2=58% and P=0.98, I2=63%, as shown in

Fig. 3.

Non-randomized study

quality evaluation is an essential key part of a comprehensive

meta-analysis of non-randomized research. Poor research might have

a negative effect on the estimation of the overall effect. As the

present meta-analysis included non-randomized studies, the

Newcastle-Ottawa scale was used to assess the risk of bias. The

Newcastle-Ottawa scale consists of eight criteria divided into

three categories: Selection, comparability and outcome and

exposure. Several answer alternatives are offered for each issue. A

star system is employed to provide a semi-quantitative evaluation

of study quality, the only exception being the comparability item,

which permits the allocation of two stars, with the highest quality

papers receiving a maximum of one star for each item. The risk of

bias total score, assessed by the Newcastle-Ottawa scale, varied

between five and eight, the mean risk of bias being 6.16, resulting

in an average level of study quality, as seen in Table II.

| Table IINewcastle-Ottawa scale of included

studies. |

Table II

Newcastle-Ottawa scale of included

studies.

| Author, year | Selection | Comparability | Exposure | Total score | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Amier et al,

2022 | **** | | *** | 7 | (8) |

| Chen et al,

2019 | *** | * | ** | 6 | (9) |

| Chhetri et

al, 2018 | ** | * | *** | 6 | (10) |

| He et al,

2018 | **** | | ** | 6 | (11) |

| Koras et al,

2015 | *** | * | * | 5 | (12) |

| Kumar et al,

2021 | *** | | ** | 5 | (13) |

| Liu et al,

2020 | *** | * | ** | 6 | (14) |

| Liu et al,

2021 | *** | * | * | 5 | (15) |

| Lorenzo Soriano

et al, 2019 | *** | * | *** | 7 | (16) |

| Rashid and

Fakhulddin, 2016 | **** | | ** | 6 | (17) |

| Tabei et al,

2016 | *** | * | ** | 6 | (18) |

| Tang et al,

2021 | *** | | *** | 6 | (19) |

| Teh and Tham,

2021 | *** | * | **** | 8 | (20) |

| Wang et al,

2020 | **** | * | ** | 7 | (21) |

| Wei et al,

2015 | *** | * | *** | 7 | (22) |

| Xu et al,

2022 | *** | | ** | 5 | (23) |

| Yang et al,

2017 | *** | * | *** | 7 | (24) |

| Zhu et al,

2020 | **** | | *** | 7 | (25) |

Discussions

PCNL is an increasingly widespread intervention that

increases the incidence of complications. According to Ghani et

al (26), sepsis following

PCNL rose from 1.2% in 1999 to 2.4% in 2009 in the United States.

Although not very common, postoperative urosepsis can be a

life-threatening complication of PCNL.

Aging brings changes that can influence patients'

immunity. A low-grade inflammatory condition characterizes elderly

patients. According to Aiello et al (27), this situation is responsible for

increased oxidative stressors and pro-inflammatory cytokines.

Furthermore, in these patients, a decrease in peripheral naive T

and B cells is found (28).

According to Bajaj et al (28), neutrophils are involved in the

immune response to bacterial aggression. They present an alteration

of neutrophil extracellular traps, one of the mechanisms involved

in the fight against pathogens. In addition, there is a reduction

in phagocytosis and a lowered intracellular killing activity

(28). In an animal model, an

impairment of the migration of neutrophils was observed, despite a

high level of chemokines (29).

Other authors have suggested that age-related alteration of

hormonal status could be responsible. According to Hao et al

(30), lower estrogen levels in

women predispose them to infections, adding other factors such as

poor perineal hygiene and menopause, making the incidence of

urosepsis double in women. Understanding the surgical risk of PCNL

in elderly patients is necessary, given the rise in life expectancy

and the number of elderly individuals undergoing surgery. The

results from the present study showed that, when conducted by a

skilled surgeon and with compensated comorbidities, PCNL can be

reasonably safe and efficiently performed on elderly patients.

A positive bladder urine culture before surgery will

lead to better antibiotic prophylaxis, although a complete

obstruction of the collecting system can lead to a sterile bladder

urine culture. For this reason, some authors suggested that the

renal pelvis urine culture could be more reliable for making

preoperative prophylaxis. In a cohort of 138 patients, Dogan et

al (31) noted that 10.1% of

patients with previous sterile bladder urine cultures had positive

renal pelvis urine cultures. Also, in a group of 122 patients,

Walton-Diaz et al (32),

bladder urine cultures were negative in all patients who developed

infectious complications following PCNL. Of these, 57.1% had

positive renal pelvis urine culture. For this reason, the authors

recommend pelvic urine culture, especially in high-risk patients,

because bladder urine culture is a poor predictor of the infectious

complications outcome. However, the analysis results of the present

study told a different story.

On the other hand, to get the renal pelvis urine

culture, placing a needle in the collecting system is necessary.

After obtaining the urine, the urologist can perform the

intervention simultaneously or place a drainage tube until the

result is available after ~48 h. The presence of a nephrostomy tube

before PCNL is a debatable factor. In a cohort of 217 patients,

Aghdas et al (33) noticed

a higher incidence of postoperative fever in those who had a

nephrostomy placed preoperatively. However, according to Benson

et al (34), it has a

protective role. There is no clear explanation for this situation.

Although the tube will drain the infected urine, it would act as a

foreign body, and the fast colonization of any urinary stent is

well known. According to Verma et al (35), 43% of bladder catheters will be

colonized after only five days and 20% will be with biofilm-forming

bacteria.

A complex relationship exists between elevated BMI,

kidney stones and urinary tract infections (UTIs). We are

witnessing a concomitant increase in the prevalence of kidney stone

disease and obesity. According to Poore et al (36), obesity in adults increased by 27.5%

from 1980 to 2013. In women with an elevated BMI, there is a

1.30-fold increased risk for kidney stone development compared with

those with a normal BMI. The explanation may be that obesity is

associated with metabolic changes that favor stone formation.

According to Taylor et al (37), urinary pH is more acidic in

patients with greater BMI and urinary oxalate, sodium, uric acid

and phosphate concentrations are higher. Similar findings were also

reported by Ekeruo et al (38); the authors noticed that

hyperoxaluria, hypercalciuria and hyperuricosuria are more commonly

found in obese stone formers compared with a non-obese cohort.

Although the present study analyzed the impact of BMI on infectious

complications following PCNL, according to Poore et al

(36), it seems that visceral

obesity is the more predictive of kidney stone risk. However, it is

more difficult to quantify because it requires imaging studies. In

the present study, the BMI did not influence the infectious

outcomes of PCNL, although some authors link obesity to a higher

chance of developing UTI. In a cohort of 95,598 subjects, Semins

et al (39) noticed that

males with a BMI between 30.0-34.9 have a higher chance of

developing UTI compared with patients with a BMI>50 (OR 1.59 vs.

2.35). A higher BMI does not influence PCNL outcome, not from the

infection's point of view but overall. According to Ortiz et

al (40), there is no

significant difference in the stone-free rate, postoperative

complication incidence, hemoglobin loss, or hospital stay.

Diabetes mellitus, obesity and arterial hypertension

are essential elements of metabolic syndrome. Urinary abnormalities

indicate a definite association between metabolic syndrome and

kidney stones. According to Domingos et al (41), these patients have excessively

acidic urine, high urinary calcium and oxalate levels and low

urinary citrate. As in the case of patients with elevated BMI,

there is a link between diabetes and UTI. According to Chiu et

al (42), a UTI in a diabetic

patient is 10 times more likely to progress to pyelonephritis.

According to Murtha et al (43), one explanation is that the immunity

to bacteria in the urinary tract is insulin-dependent. The authors

proved in an animal model that insulin resistance leads to a

suppression of urinary antimicrobial peptides suggesting that

urinary sugar is not the essential element behind UTIs in these

patients. In addition, elevated blood sugar influences resistance

to UTIs. In diabetic patients, some immune alterations have been

observed, such as an elevation in CD4+CD28null T-lymphocytes count,

lower levels of serum complement factor 4 concentration and plasma

zinc levels and also significantly lower PMNs chemotaxis (44,45).

The results of the present study show that diabetes is a

predisposing factor for postoperative infections. Considering that

PCNL is an elective operation, it is assuming that the patient's

blood sugar was within normal limits at the time of the

intervention. However, an unbalanced history of diabetes may

contribute to the unfavorable evolution. Future studies would help

identify the relationship between hemoglobin A1c and SIRS/sepsis

following PCNL.

In patients with staghorn stones, surgical

management can be complex. Performing multiple tracts, PCNL can

increase the rate of complications and the period of

hospitalization. In a cohort of 27 patients where multiple tract

PCNL was performed, Liang et al (46) obtained a stone-free rate within

three sessions in 88.9% of cases. The authors did not report

significant blood loss, while postoperative fever was encountered

in only 22.22% of cases. A group of 65 patients evaluated by Rashid

et al (47), who underwent

multiple tract PCNL, had a significant decrease in hemoglobin

level, while serum creatinine remained relatively unchanged. In

their cohort, 11% had a postoperative fever, while only 3%

presented an infection that required additional antibiotics. In a

much larger cohort of 773 patients with staghorn calculi in which

PCNL was performed, of which 514 with multiple tracts, Desai et

al (48) reported

postoperative fever in up to 28.2% of patients.

Given the risk of infectious complications, a

logical strategy would be to use antibiotic prophylaxis. However,

it remains a debatable topic related to the categories of patients

who would benefit the most and the treatment regimen, a single

preoperative dose or treatment for several days. In a meta-analysis

by Yu et al (1), which

included 13 studies with a total of 1,549 patients, the results

indicated that for those receiving prophylactic treatment for a few

days compared with those receiving a single dose, the symptoms of

sepsis were significantly lower as well as positive cultures in the

renal pelvis. Moreover, according to Xu et al (23), optimal antibiotic prophylaxis in

those with preoperative positive urine cultures should last at

least seven days. Schnabel et al (49) compared 98 patients who received

antibiotics one day preoperatively with 76 patients who did not

receive prophylaxis. The authors found no significant differences

in fever, grade 1-3 complications, or hospitalization. The authors

considered that antibiotic prophylaxis might not be necessary in

selected cases, such as those with negative urine culture,

non-staghorn stones and no history of urinary tract infections.

Some authors have tried to evaluate the role of the urine dipstick

test before the PCNL. In a group of 806 patients, Xu et al

(50) reported that positive urine

dipstick infection prior to surgery strongly predicted SIRS.

Paradoxically, extensive preoperative antibiotic use was linked to

a greater risk of SIRS.

According to European Association of Urology

recommendations, 2022 edition, the probability of infection during

PCNL is high and antibiotic prophylaxis has been demonstrated to

minimize the risk for infectious complications significantly with a

single dosage being adequate (51). Antibiotic prophylaxis should be

given even with a negative urine culture, according to American

Urological Association Guidelines, which are regarded as a clinical

principle (52). In this part, the

American Urological Association panel makes the case that there is

insufficient evidence to suggest giving patients with a negative

urine culture one week of preventive antibiotics. In a recent

survey that included over 3,000 Chinese urologists, Zhang et

al (53) reported that

antibiotic prophylaxis for 1-3 days before surgery was most often

used regardless of whether the urine culture was positive or

negative (54.5 vs. 65.5%). Cephalosporins are the most used

antibiotic type, followed by quinolones. Considering that urine

cultures are not specific for the colonization status, He et

al (54) compared two types of

antibiotic regimens with the presence of white blood cells (WBC)

and nitrites in urine. The authors showed that one 1.5 g dose of

cefuroxime before PCNL compared with 3-day treatment statistically

lowered the incidence of SIRS in patients with positive nitrites in

urine but did not influence the outcome in patients with absent

nitrites in urine. In the cohort studied by Xu et al

(23), the urine culture result

was unavailable before the procedure in some patients. In these

cases, they received an empirical antibiotic prophylaxis 30 before

the surgery and postoperatively, the antibiotic therapy was

adjusted after obtaining the result. The authors evaluated the

effects of antibiotic prophylaxis schemes. Although a more extended

antibiotic prophylaxis was significantly associated with a better

outcome, the administration of sensitive antibiotics did not prove

a significant advantage over non-sensitive antibiotics.

From the data of the present study, between

2017-2021, of the 463 cases in which PCNL was performed, 5.18%

(n=24) developed postoperative sepsis/SIRS. Of these, 54.2% (n=13)

were men and 45.8% (n=11) were women. The stone-free rate was 75%

and the overall stone-free rate was 69.11%. The bladder

preoperative urine culture was positive in 58.33% (n=14) of

patients compared with 25.20% in the non-sepsis group. Also, the

preoperative presence of urinary stents was noted more frequently

in the sepsis/SIRS group (62.5% vs. 17.71%). The majority (93.33%)

had JJ ureteral stents. In all cases, developing sepsis/SIRS

symptoms led to a change in the postoperative antibiotic regimen

(55).

The present meta-analysis has some limitations:

First, the studies are somewhat heterogenous; the authors came from

different continents, the number of patients varied from 60 to

1,030 and renal pelvic urine culture was not available in all

cases. Also, the dilatation technique, balloon compared with

telescopic/serial dilation, was not known in all studies. Another

drawback of the meta-analysis is the need to evaluate the type of

kidney stones according to the various scoring systems. Only one of

the included studies reported that a higher STONE (Stone size,

Tract length, Obstruction, Number of involved calices and Essence

or stone density) score correlates significantly with sepsis/SIRS

(19). From the present study

authors' experience with the Guy stone score, it was also found

that patients with the highest grade (IV) have significantly more

preoperative positive urine culture and complications according to

the Clavien scale and the lowest stone-free rate (56).

Despite this, the present meta-analysis has some

strong points. All patients in the included studies underwent the

same type of intervention. The outcomes are well defined, SIRS

respectively sepsis, or quantified such as WBC, preoperative urine

culture, or BMI. Thus, some elements are easy to compare, such as

the operative time, which depends on several factors. According to

Akman et al (56), some of

these factors are the previous presence of hydronephrosis, stone

characteristics and surgeon experience, which could not be

evaluated in the present analysis. Further studies should evaluate

supplemental sepsis indicators such as C-reactive protein,

hemoglobin A1c or procalcitonin. Also, the type of PCNL technique

(standard or miniPCNL) could be an influencing factor considering

as, according to Jiao et al (57), there is no difference regarding

postoperative fever between standard compared with miniPCNL.

However, the operative time was significantly shorter in patients

in which minPCNL and, according to the data of the present

analysis, a longer operative time favors the development of

SIRS/sepsis.

The present analysis showed that diabetes mellitus,

multitract PCNL, pyuria, operative time and positive urine culture

are factors that, if not controlled, favor the appearance of SIRS

or urosepsis. In some high-risk patients, such as those with

diabetes, a history of urinary tract infections, or positive urine

cultures, antibiotic prophylaxis should be mandatory and performed

for at least one week before surgery.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article, as

no data sets were generated or analyzed during the current

study.

Authors' contributions

DP and CP were responsible for conceiving the study

and DP was responsible for the methodology, formal analysis and

software. Validation was performed by DP, CP and SG and

investigation by GR and SG. Data curation was by SG, GR and VJ. DP,

GR and SG wrote the original draft of the manuscript, which was

reviewed and edited by VJ and CP. CP and VJ were responsible for

visualization and supervision. Data authentication is not

applicable. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Yu J, Guo B, Yu J, Chen T, Han X, Niu Q,

Xu S, Guo Z, Shi Q, Peng X, et al: Antibiotic prophylaxis in

perioperative period of percutaneous nephrolithotomy: A systematic

review and meta-analysis of comparative studies. World J Urol.

38:1685–1700. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Jiang Y and Zhang J, Kang N, Niu Y, Li Z,

Yu C and Zhang J: Current Trends in percutaneous nephrolithotomy in

China: A spot survey. Risk Manag Health Policy. 14:2507–2515.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Türk C, Petřík A, Sarica K, Seitz C,

Skolarikos A, Straub M and Knoll T: EAU guidelines on

interventional treatment for urolithiasis. Eur Urol. 69:475–482.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Sharma K, Sankhwar SN, Goel A, Singh V,

Sharma P and Garg Y: Factors predicting infectious complications

following percutaneous nephrolithotomy. Urol Ann. 8:434–438.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Michel MS, Trojan L and Rassweiler JJ:

Complications in percutaneous nephrolithotomy. Eur Urol.

51:899–906. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Yang Z, Lin D, Hong Y, Hu M, Cai W, Pan H,

Li Q, Lin J and Ye L: The effect of preoperative urine culture and

bacterial species on infection after percutaneous nephrolithotomy

for patients with upper urinary tract stones. Sci Rep.

12(4833)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron

I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan

SE, et al: The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for

reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 372(n71)2021.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Amier Y, Zhang Y, Zhang J, Yao W, Wang S,

Wei C and Yu X: Analysis of preoperative risk factors for

postoperative urosepsis after mini-percutaneous nephrolithotomy in

patients with large kidney stones. J Endourol. 36:292–297.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Chen D, Jiang C, Liang X, Zhong F, Huang

J, Lin Y, Zhao Z, Duan X, Zeng G and Wu W: Early and rapid

prediction of postoperative infections following percutaneous

nephrolithotomy in patients with complex kidney stones. BJU Int.

123:1041–1047. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Chhetri RK, Baral S and Thapa N:

Prediction of infectious complications after percutaneous

nephrolithotomy. J Soc Surg Nepal. 21:12–18. 2018.

|

|

11

|

He Z, Tang F, Lei H, Chen Y and Zeng G:

Risk factors for systemic inflammatory response syndrome after

percutaneous nephrolithotomy. Prog Urol. 28:582–587.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Koras O, Bozkurt IH, Yonguc T, Degirmenci

T, Arslan B, Gunlusoy B, Aydogdu O and Minareci S: Risk factors for

postoperative infectious complications following percutaneous

nephrolithotomy: A prospective clinical study. Urolithiasis.

43:55–60. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Kumar GC, Devraj R, Sagar V, Chandraiah R,

Prasad D and Ch R: Factors determining postoperative infectious

complications of percutaneous nephrolithotomy: Experience from a

single center. Int J Health Clin Res. 4:127–130. 2021.

|

|

14

|

Liu J, Zhou C, Gao W, Huang H, Jiang X and

Zhang D: Does preoperative urine culture still play a role in

predicting post-PCNL SIRS? A retrospective cohort study.

Urolithiasis. 48:251–256. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Liu J, Yang Q, Lan J, Hong Y, Huang X and

Yang B: Risk factors and prediction model of urosepsis in patients

with diabetes after percutaneous nephrolithotomy. BMC Urol.

21(74)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Lorenzo Soriano L, Ordaz Jurado DG, Pérez

Ardavín J, Budía Alba A, Bahílo Mateu P, Trassierra Villa M and

López Acón D: Predictive factors of infectious complications in the

postoperative of percutaneous nephrolithotomy. Actas Urol Esp (Engl

Ed). 43:131–136. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Rashid AO and Fakhulddin SS: Risk factors

for fever and sepsis after percutaneous nephrolithotomy. Asian J

Urol. 3:82–87. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Tabei T, Ito H, Usui K, Kuroda S, Kawahara

T, Terao H, Fujikawa A, Makiyama K, Yao M and Matsuzaki J: Risk

factors of systemic inflammation response syndrome after endoscopic

combined intrarenal surgery in the modified Valdivia position. Int

J Urol. 23:687–692. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Tang Y, Zhang C, Mo C, Gui C, Luo J and Wu

R: Predictive model for systemic infection after percutaneous

nephrolithotomy and related factors analysis. Front Surg.

8(696463)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Teh KY and Tham TM: Predictors of

post-percutaneous nephrolithotomy sepsis: The Northern Malaysian

experience. Urol Ann. 13:156–162. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Wang S, Yuan P, Peng E, Xia D, Xu H, Wang

S, Ye Z and Chen Z: Risk factors for urosepsis after minimally

invasive percutaneous nephrolithotomy in patients with preoperative

urinary tract infection. Biomed Res Int.

2020(1354672)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Wei W, Leng J, Shao H and Wang W:

Diabetes, a risk factor for both infectious and major complications

after percutaneous nephrolithotomy. Int J Clin Exp Med.

8:16620–16626. 2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Xu P, Zhang S, Zhang Y, Zeng T, Chen D and

Wu W, Tiselius HG, Li S, Huang J, Zeng G and Wu W: Preoperative

antibiotic therapy exceeding 7 days can minimize infectious

complications after percutaneous nephrolithotomy in patients with

positive urine culture. World J Urol. 40:193–199. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Yang T, Liu S, Hu J, Wang L and Jiang H:

The evaluation of risk factors for postoperative infectious

complications after percutaneous nephrolithotomy. Biomed Res Int.

2017(4832051)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Zhu Z, Cui Y, Zeng H, Li Y, Zeng F, Li Y,

Chen Z and Hequn C: The evaluation of early predictive factors for

urosepsis in patients with negative preoperative urine culture

following mini-percutaneous nephrolithotomy. World J Urol.

38:2629–2636. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Ghani KR, Sammon JD, Bhojani N,

Karakiewicz PI, Sun M, Sukumar S, Littleton R, Peabody JO, Menon M

and Trinh QD: Trends in percutaneous nephrolithotomy use and

outcomes in the United States. J Urol. 190:558–564. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Aiello A, Farzaneh F, Candore G, Caruso C,

Davinelli S, Gambino CM, Ligotti ME, Zareian N and Accardi G:

Immunosenescence and its hallmarks: how to oppose aging

strategically? A review of potential options for therapeutic

intervention. Front Immunol. 10(2247)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Bajaj V, Gadi N, Spihlman AP, Wu SC, Choi

CH and Moulton VR: Aging, immunity, and COVID-19: How age

influences the host immune response to coronavirus infections?

Front Physiol. 11(571416)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Zhou YY and Sun BW: Recent advances in

neutrophil chemotaxis abnormalities during sepsis. Chin J

Traumatol. 25:317–324. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Hao Z, Wang J, Wang Q, Luan G and Qian B:

Preoperative risk factors associated with urosepsis following

percutaneous nephrolithotomy: A meta-analys. Int J Clin Exp Med.

12:9616–9628. 2019.

|

|

31

|

Dogan HS, Guliyev F, Cetinkaya YS,

Sofikerim M, Ozden E and Sahin A: Importance of microbiological

evaluation in management of infectious complications following

percutaneous nephrolithotomy. Int Urol Nephrol. 39:737–742.

2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Walton-Diaz A, Vinay JI, Barahona J, Daels

P, González M, Hidalgo JP, Palma C, Díaz P, Domenech A, Valenzuela

R and Marchant F: Concordance of renal stone culture: PMUC, RPUC,

RSC and post-PCNL sepsis-a non-randomized prospective observation

cohort study. Int Urol Nephrol. 49:31–35. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Aghdas FS, Akhavizadegan H, Aryanpoor A,

Inanloo H and Karbakhsh M: Fever after percutaneous

nephrolithotomy: Contributing factors. Surg Infect (Larchmt).

7:367–371. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Benson AD, Juliano TM and Miller NL:

Infectious outcomes of nephrostomy drainage before percutaneous

nephrolithotomy compared to concurrent access. J Urol. 192:770–774.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Verma A, Bhani D, Tomar V, Bachhiwal R and

Yadav S: Differences in bacterial colonization and biofilm

formation property of uropathogens between the two most commonly

used indwelling urinary catheters. J Clin Diagn Res. 10:PC01–PC03.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Poore W, Boyd CJ, Singh NP, Wood K, Gower

B and Assimos DG: Obesity and its impact on kidney stone formation.

Rev Urol. 22:17–23. 2020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Taylor EN, Stampfer MJ and Curhan GC:

Obesity, weight gain, and the risk of kidney stones. JAMA.

293:455–462. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Ekeruo WO, Tan YH, Young MD, Dahm P,

Maloney ME, Mathias BJ, Albala DM and Preminger GM: Metabolic risk

factors and the impact of medical therapy on the management of

nephrolithiasis in obese patients. J Urol. 172:159–163.

2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Semins MJ, Shore AD, Makary MA, Weiner J

and Matlaga BR: The impact of obesity on urinary tract infection

risk. Urology. 79:266–269. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Torrecilla Ortiz C, Meza Martínez AI,

Vicens Morton AJ, Vila Reyes H, Colom Feixas S, Suarez Novo JF and

Franco Miranda E: Obesity in percutaneous nephrolithotomy. Is body

mass index really important? Urology. 84:538–543. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Domingos F and Serra A: Metabolic

syndrome: A multifaceted risk factor for kidney stones. Scand J

Urol. 48:414–419. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Chiu PF, Huang CH, Liou HH, Wu CL, Wang SC

and Chang CC: Long-term renal outcomes of episodic urinary tract

infection in diabetic patients. J Diabetes Complications. 27:41–43.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Murtha MJ, Eichler T, Bender K, Metheny J,

Li B, Schwaderer AL, Mosquera C, James C, Schwartz L, Becknell B

and Spencer JD: Insulin receptor signaling regulates renal

collecting duct and intercalated cell antibacterial defenses. J

Clin Invest. 128:5634–5646. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Giubilato S, Liuzzo G, Brugaletta S,

Pitocco D, Graziani F, Smaldone C, Montone RA, Pazzano V, Pedicino

D, Biasucci LM, et al: Expansion of CD4+CD28null T-lymphocytes in

diabetic patients: exploring new pathogenetic mechanisms of

increased cardiovascular risk in diabetes mellitus. Eur Heart J.

32:1214–1226. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Geerlings SE and Hoepelman AI: Immune

dysfunction in patients with diabetes mellitus (DM). FEMS Immunol

Med Microbiol. 26:259–265. 1999.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Liang T, Zhao C, Wu G, Tang B, Luo X, Lu

S, Dong Y and Yang H: Multi-tract percutaneous nephrolithotomy

combined with EMS lithotripsy for bilateral complex renal stones:

Our experience. BMC Urol. 17(15)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Rashid AO, Mahmood SN, Amin AK, Bapir R

and Buchholz N: Multitract percutaneous nephrolithotomy in the

management of staghorn stones. Afr J Urol. 26(74)2020.

|

|

48

|

Desai M, Jain P, Ganpule A, Sabnis R,

Patel S and Shrivastav P: Developments in technique and technology:

The effect on the results of percutaneous nephrolithotomy for

staghorn calculi. BJU Int. 104:542–548. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Schnabel MJ, Rosenhammer B, Steckermeier

M, Fritsche HM, Burger M and Spachmann PJ: Miniaturized

percutaneous nephrolithotomy without antibiotic prophylaxis: A

single institution experience. Int Urol Nephrol. 53:1551–1556.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Xu P, Zhang S, Zhang Y, Zeng T, Chen D and

Wu W, Tiselius HG, Li S, Huang J, Zeng G and Wu W: Enhanced

antibiotic treatment based on positive urine dipstick infection

test before percutaneous nephrolithotomy did not prevent

postoperative infection in patients with negative urine culture. J

Endourol. 35:1743–1749. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

European Association of Urology (EAU):

Guideline on urolithiasis. EAU, Arnhem, 2022. https://uroweb.org/guidelines/urolithiasis. Accessed

December 20, 2022.

|

|

52

|

Pearle MS, Goldfarb DS, Assimos DG, Curhan

G, Denu-Ciocca CJ, Matlaga BR, Monga M, Penniston KL, Preminger GM,

Turk TM, et al: Medical management of kidney stones: AUA guideline.

J Urol. 192:316–324. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Zhang S, Li G, Qiao L, Lai D, He Z, An L,

Xu P, Tiselius HG, Zeng G, Zheng J and Wu W: The antibiotic

strategies during percutaneous nephrolithotomy in China revealed

the gap between the reality and the urological guidelines. BMC

Urol. 22(136)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

He C, Chen H, Li Y, Zeng F, Cui Y and Chen

Z: Antibiotic administration for negative midstream urine culture

patients before percutaneous nephrolithotomy. Urolithiasis.

49:505–512. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Puia D, Radavoi GD, Proca TM, Puia A,

Jinga V and Pricop C: Urinary tract infections in complicated

kidney stones: Can they be correlated with Guy's stone score? J Pak

Med Assoc. 72:1721–1725. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Akman T, Binbay M, Akcay M, Tekinarslan E,

Kezer C, Ozgor F, Seyrek M and Muslumanoglu AY: Variables that

influence operative time during percutaneous nephrolithotomy: An

analysis of 1897 cases. J Endourol. 25:1269–1273. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Jiao B, Luo Z, Huang T, Zhang G and Yu J:

A systematic review and meta-analysis of minimally invasive vs

standard percutaneous nephrolithotomy in the surgical management of

renal stones. Exp Ther Med. 21(213)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|