Introduction

An unapproved prescription describes the provision

of a medicine without marketing authorization for human use,

whereas an off-label prescription describes the use of an

authorized drug outside of the recommended age group, indication,

dosage, route of administration or frequency of use (1). Pharmaceutical trials of medicines

that are not tested in children may result in off-label or

unapproved drug prescriptions provided to children (2). Despite legislative enforcement on

authorized drugs, approved pediatric formulations are ineffective

for the pharmaceutical industry (3). A function of the Mutual Recognition

Agreements signed by The European Union (EU) and third-country

authorities is to assess drug safety and efficacy of medicines

prior to public release (4).

However, testing of drug safety and efficacy in children raises

ethical concerns, and therefore, the number of pediatric clinical

trials is limited (5,6). This may lead to clinicians

prescribing drugs to children using data from adult clinical

trials, which could lead to increased numbers of unapproved and

off-label prescriptions provided to children (7). Off-label and unauthorized

prescriptions present significant risks to children (8). However, a previous study reported

that, within a 2-month period of observation, the prevalence of

off-label and unlicensed drug use was increased in both pediatric

intensive care units (PICUs) and neonatal intensive care units

(NICUs), compared with a study at the same location 16 years prior,

despite the anticipated impact of current regulatory efforts

(9).

As of early 1937, 353 patients were exposed to

Elixir sulfanilamide. Nearly one-third of them, 34 children and 71

adults, soon died of acute kidney failure (10). A total of 25 years later, use of

the over-the-counter sleeping pill thalidomide was reported to

induce teratogenesis in consumers in America, Australia and Europe

(11). Furthermore, in 1971,

diethylstilbestrol (a non-steroidal estrogen medication), 30 years

after its approval by the Food and Drug Administration, was

discontinued due to its association with breast cancer (12). These occurrences necessitated

stringent drug regulations to ensure efficacy of approved drugs and

safeguard the health of their users. The prescription of off-label

and unlicensed drugs to children may potentially be associated with

toxicity and adverse drug effects (13). A specific condition that may be

associated with the use of off-label and unlicensed drugs in

children is bipolar depression in depressive episodes. Currently

available antidepressants in children are unsatisfactory; for

example, a number of systematic reviews have indicated that

antidepressant methylphenidate and memantine have high non-response

rates and non-tolerance (14).

High non-response rates and non-tolerance in children are also

associated with second-generation antipsychotic drugs such as

amisulpride, clozapine, olanzapine and risperidone (15).

Differences in use of off-label and unauthorized

prescriptions between countries may be attributed to varying

stringency of drug regulatory authorities and pharmaceutical

spending budgets, which are associated with gross domestic product

(GDP) (16). The lack of

pediatric-specific medications may contribute to off-label and

unlicensed prescriptions. Multi-collaborative efforts involving

researchers, medical staff, industry regulators and policy makers

may be required to establish pediatric formulations in the future.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to estimate

the global pooled prevalence of off-label and unlicensed

prescriptions given to hospitalized children in NICUs, PICUs or

standard pediatric wards, using meta-analysis.

Materials and methods

Literature search strategy

The present systematic review adhered to the

preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses

(PRISMA) guidelines (17). A

comprehensive literature search was conducted on January 12, 2023

using the PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), Scopus (https://www.elsevier.com/zh-cn/products/scopus/search),

Web of Science (https://www.webofscience.com/wos) and Google Scholar

databases (https://scholar.google.com/) for articles published

between 1990 and 2023. Medical subject headings and key word

queries were used across all databases. The PubMed database was

searched using the key words, ‘off label use’ and ‘prevalence’, in

combination with ‘children’. The other databases used queries such

as ‘prevalence’, ‘off label drug use’ or ‘unlicensed drug use’,

alongside ‘children’, with the language preference set to English

and document type set to articles. Only observational studies that

reported prevalence of off-label or unlicensed prescribing in

hospitalized pediatric patients and published in English were

included. Reviews, duplicates and non-full text articles were

excluded.

Data extraction

Data search and extraction was conducted by two

independent researchers using EndNote (version X9; Clarivate Plc.).

The researchers independently selected the most relevant articles

using the titles and abstracts of articles. Full-text articles were

selected and assessed for eligibility. An independent third party

arbitrated discrepancies. Data were extracted from each article

using a standardized form with the following fields: Author, year,

country, mean age, prevalence of off-label and unlicensed drug use,

study design, sample size, study setting, total prescriptions,

prescription drugs, and off-label and unlicensed prescriptions.

Risk of bias and quality

assessment

The Joanna Briggs Institute critical assessment

checklist (18) was used to assess

the quality of included studies, which included the likelihood of

bias in design, implementation and analysis (Table SI). The checklist has nine

questions, answers to which are either yes, no, unclear or not

applicable. High quality studies achieve a minimum of 5 affirmative

responses.

Statistical analysis

The primary outcome of the present study was

prevalence of off-label and unlicensed prescriptions to children.

The following analyses were conducted: Pooled prevalence of

off-label prescriptions among i) ICU and ii) general pediatric ward

patients, and pooled prevalence of unlicensed prescriptions among

iii) ICU and iv) general pediatric ward patients. The prevalence of

off-label or unlicensed prescriptions was calculated by dividing

the number of off-label or unlicensed prescriptions by total number

of prescriptions. STATA (version 16; StataCorp LP) software was

used to calculate SE and CI values, and for forest map generation.

The random-effects model was used regardless of the outcome of the

heterogeneity analysis. I2>50% was considered to

indicate high heterogeneity. Subgroup analysis was conducted using

data from the International Monetary Fund on global GDP

distribution (16). Sensitivity

analysis was performed by the exclusion of individual studies one

at a time and those of insufficient quality were excluded. Egger's

test and funnel plots were used to evaluate publication bias. The

χ2 test was used for categorical data. P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

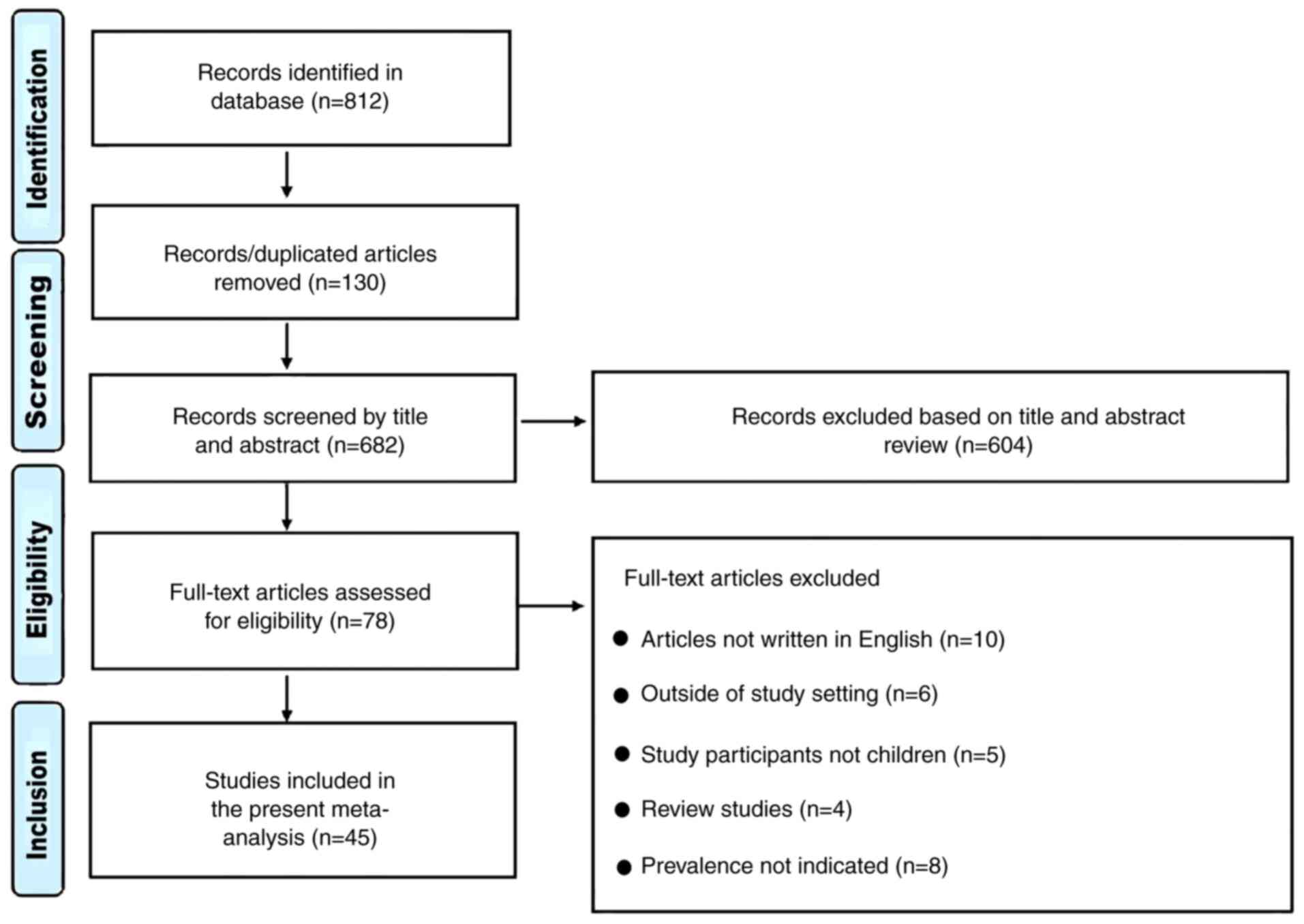

Literature search and screen

A total of 812 articles were examined, of which 130

duplicates were excluded (Fig. 1).

Subsequently, 604 articles were excluded following examination of

the title, full text and abstract, which left 78 studies. Further

exclusions included 10 studies that were not written in English, 8

that did not report on prevalence, 6 studies that were conducted

outside the NICU, PICU or general pediatric ward, 4 reviews and 5

studies that involved mixed participants (adults and children). A

total of 45 studies were included in the present study (9,10,19-61).

Study characteristics

The 45 articles included in the meta-analysis

included 26 prospective, 7 retrospective and 12 cross-sectional

studies (Table I). Patient sample

size varied from 40 to 13,426, with a range of 240-8,891

prescriptions issued. Of the 45 studies, 22 originated from Europe,

13 from Asia, three each from South America and Africa and 2 each

from North America and Australia. Off-label prevalence was reported

in all articles (10.0-87.0%), while 34 studies reported the

prevalence of unlicensed prescriptions (1.3-79.0%). In total, 34

(75.6%) studies reported prevalence of both off-label and

unlicensed medication prescriptions among participants. All studies

recruited participants from either the NICU, PICU or general ward,

with 23 studies conducted in general pediatric wards. The highest

prevalence of off-label drug use was reported in Estonia (87%),

followed by Ethiopia (75%). The lowest off-label prevalence was in

Italy (9%), followed by Zimbabwe (10%). The highest unlicensed drug

prevalence was reported in Indonesia (79.0%).

| Table ICharacteristics of included

studies. |

Table I

Characteristics of included

studies.

| | Prevalence, % | | Number | |

|---|

| First author,

year | Country of

residence | Patient age | Off-label | Unlicensed | Study design | No. of

patients | Study setting | Total

prescriptions | Off-label and

unlicensed | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Turner et

al, 1999 | UK | 1.0 ya | 35.3 | - | Prospective | 936 | PICU | 4,455 | 1,574 | (19) |

| Conroy et

al, 1999 | UK | 26.0-36.0 w | 54.7 | 9.9 | Prospective | 70 | NICU | 455 | 294 | (20) |

| Pandofini et

al, 2002 | Italy | 3.7 yb | 60.0 | - | Prospective | 1,461 | General ward | 4,255 | 2,547 | (21) |

| Barr et al,

2002 | Israel | <28.0 d | 59.0 | 16.0 | Prospective | 105 | NICU | 525 | 397 | (22) |

| Jong et al,

2002 | Netherlands | 16.7 ya | 43.0 | 28.0 | Prospective | 293 | General ward | 1,017 | 728 | (23) |

| Conroy et

al, 2003 | UK | - | 54.6 | - | Prospective | 51 | PICU | 1,574 | 859 | (24) |

| Jong et al,

2004 | UK | 8.7 yb | 20.3 | 16.8 | Retrospective | 13,426 | General ward | 5,253 | 1,947 | (25) |

| Neubert et

al, 2004 | Germany | <18.0 y | 26.4 | 1.3 | Prospective | 178 | General ward | 740 | 198 | (26) |

| Bajcetic et

al, 2005 | Belgrade | 4.0 h -18.0 y | 48.0 | 11.0 | Prospective | 544 | General ward | 2,037 | 1,202 | (27) |

| Di Paolo et

al, 2006 | Sweden | 3.0-14.0 y | 25.0 | 24.0 | Prospective | 60 | General ward | 483 | 236 | (28) |

| Kaisi et al,

2007 | Zimbabwe | 1.0-5.0 y | 10.0 | 31.0 | Prospective | 300 | General ward | 300 | 123 | (29) |

| Santos et

al, 2008 | Brazil | 2.0 yb | 39.6 | 55.0 | Prospective | 272 | General ward | 1,450 | 623 | (30) |

| Bavdekar et

al, 2009 | India | 3.6±3.7

yb | 70.6 | - | Prospective | 300 | PICU | 2,237 | 1,579 | (31) |

| Lass et al,

2011 | Estonia | <28.0 d | 87.0 | - | Prospective | 490 | NICU | 1,981 | 1,723 | (32) |

| Palčevski et

al, 2012 | Croatia | 6.8 mb | 13.3 | 11.9 |

Cross-sectional | 691 | General ward | 1,643 | 412 | (33) |

| Oguz et al,

2012 | Turkey | 32.5±4.7

wb | 33.5 | 28.8 | Prospective | 464 | NICU | 1,315 | 819 | (34) |

| Ballard et

al, 2013 | Australia | 2.6 yb | 36.0 | - | Retrospective | 300 | General ward | 887 | 283 | (35) |

| Kieran et

al, 2014 | Ireland | 35.0 wb | 39.0 | 19.0 | Prospective | 110 | NICU | 900 | 522 | (36) |

| Silva et al,

2015 | Portugal | 36.1±4.0

wb | 27.9 | 4.4 |

Cross-sectional | 218 | NICU | 1,011 | 326 | (37) |

| Lee et al,

2013 | Malaysia | 2.0 yb | 34.1 | 27.3 | Prospective | 168 | PICU | 1,295 | 795 | (38) |

| Ribeiro et

al, 2013 | Portugal | 6.2±4.9

yb | 32.2 | - | Retrospective | 700 | General ward | 724 | 233 | (39) |

| Lindell-Osuagwu

et al, 2014 | Finland | 1.0-12.0 y | 51.0 | - | Prospective | 123 | NICU | 1,054 | 538 | (40) |

| Laforgia et

al, 2014 | Italy | 37.0 wb | 37.4 | 11.4 |

Cross-sectional | 126 | NICU | 483 | 236 | (41) |

| Langerová et

al, 2014 | Italy | 1.0-15.0

yb | 9.0 | 1.3 | Retrospective | 4,282 | General ward | 8,559 | 879 | (42) |

| Luedtke et

al, 2014 | USA | 3.0 w-15.0 y | 57 | - | Prospective | 40 | General ward | 240 | 136 | (43) |

| Riou et al,

2015 | France | 34.0 wb | 59.5 | 5.2 | Prospective | 910 | NICU | 8,891 | 5,752 | (44) |

| Joret-Descout et

al, 2015 | France | 5.1 yb | 36.5 | 3.2 |

Cross-sectional | 120 | General ward | 315 | 125 | (45) |

| Jobanputra et

al, 2015 | India | 6.3±1.7

wb | 41.3 | 21.0 | Prospective | 482 | PICU | 1,789 | 1,114 | (46) |

| Berdkan et

al, 2016 | Lebanon | 3.5 yb | 30.2 | 11.1 | Retrospective | 500 | PICU | 2,054 | 848 | (47) |

| Cuzzolin et

al, 2016 | Italy | 3.3 wb | 59.0 | 14.5 |

Cross-sectional | 220 | NICU | 720 | 529 | (48) |

| Corny et al,

2016 | Canada | 10.9 yb | 38.2 | 8.3 |

Cross-sectional | 308 | General ward | 2,145 | 997 | (49) |

| Ramadaniati et

al, 2017 | Indonesia | 2.0 yb | 50.8 | 15.1 | Retrospective | 67 | General ward | 1,553 | 1,023 | (50) |

| Tefera et

al, 2017 | Ethiopia | 4.5±4.3

yb | 75.8 | - | Prospective | 243 | General ward | 800 | 607 | (51) |

| Teigen et

al, 2017 | Norway | 0.0-17.0 y | 44.0 | 26.0 |

Cross-sectional | 179 | General ward | 930 | 650 | (52) |

| Nir-Neuman et

al, 2018 | Israel | 33.0-38.0 w | 64.8 | 5.9 | Prospective | 134 | NICU | 1,069 | 756 | (9) |

| Costa et al,

2018 | Brazil | 2.4±4.4

wb | 49.3 | 24.6 | Prospective | 220 | NICU | 17,421 | 12,869 | (53) |

| Mazhar et

al, 2018 | Saudi Arabia | 12.0 db | 29.7 | 12.9 | Prospective | 138 | NICU | 583 | 248 | (54) |

| Aamir et al,

2018 | Pakistan | 8.0±18.5

db | 52.1 | 33.4 | Prospective | 1,300 | General ward | 3,448 | 2,948 | (55) |

| Landwehr et

al, 2019 | Australia | 6.0±4.7

yb | 54.0 | 1.6 |

Cross-sectional | 190 | General ward | 1,160 | 644 | (10) |

| Dornelles et

al, 2019 | Brazil | 18.0 mb | 44.6 | 27.0 | Prospective | 157 | PICU | 1,328 | 951 | (56) |

| Kouti et al,

2019 | Iran | 34.0±4.4

wb | 38.1 | 1.9 |

Cross-sectional | 193 | NICU | 1,049 | 420 | (57) |

| Tukayo et

al, 2020 | Indonesia | 1.8 yb | 71.5 | 79.0 |

Cross-sectional | 200 | General ward | 1,961 | 1,557 | (58) |

| Gidey et al,

2020 | Ethiopia | 0.0-28.0 d | 67.6 | 23.6 |

Cross-sectional | 122 | NICU | 366 | 334 | (59) |

| García-López et

al, 2020 | Italy | 9.0 mb | 39.6 | 12.9 |

Cross-sectional | 85 | General ward | 1,198 | 630 | (60) |

| AlAzmi et

al, 2021 | Saudi Arabia | 4.0 yb | 39.4 | - | Retrospective | 326 | General ward | 865 | 341 | (61) |

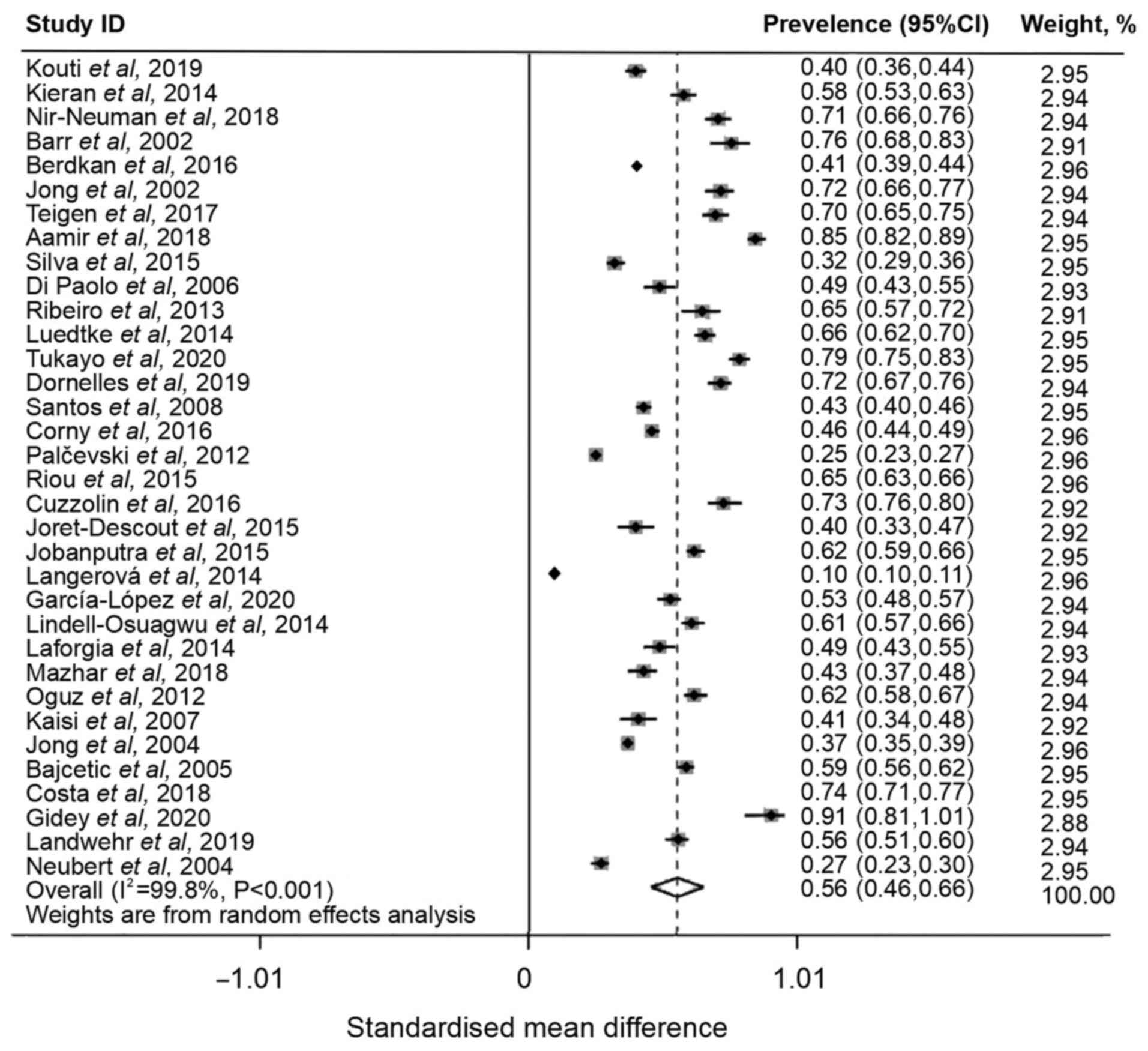

Overall pooled prevalence of off-label

and unlicensed drug use

A total of 45 articles were included in the

meta-analysis, which involved 60,997 off-label and unlicensed drugs

prescribed to patients in the NICU, PICU or general wards. Due to

the number of study designs used, a random-effect meta-analysis

model was used to assess total number of prescriptions, and

off-label and unlicensed prescriptions issue. The global prevalence

of off-label and unlicensed prescriptions among pediatric or

neonatal patients was 56% (95% CI, 0.46-0.66), with high

heterogeneity (I2=99.8%; Fig. 2). As significant heterogeneity was

observed, sensitivity analysis was performed. Sensitivity analysis

indicated that the pooled prevalence remained notably stable upon

exclusion of each study (Fig.

S1). Sensitivity analysis was performed to assess the impact of

excluding studies that had a small sample size of prescriptions.

Following the exclusion of 12 studies that had <1,000

prescriptions, the overall combined prevalence decreased to 55% and

demonstrated high heterogeneity (I2=99.4%; Figs. S2 and S3). The exclusion of articles with a

small sample size did not significantly alter the global prevalence

of off-label and unlicensed drug prescriptions to children. The

high heterogeneity of included studies may be due to methodological

differences of study designs. The exclusion of studies with a high

risk of bias did not significantly alter the prevalence rates of

off-label and unlicensed drug prescriptions (Fig. S1, Fig. S2 and Fig. S3) to children, as calculated from

the sensitivity analysis .

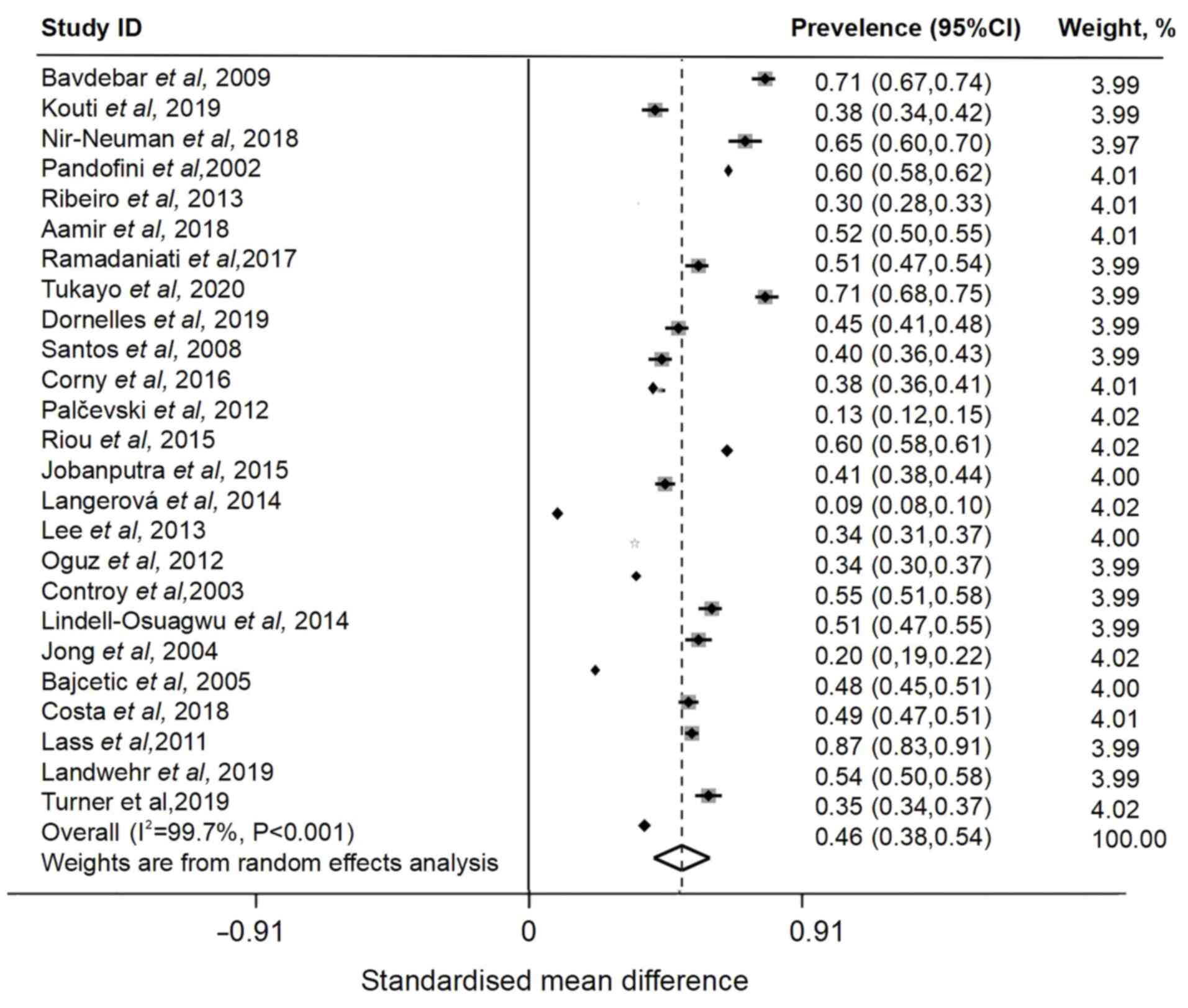

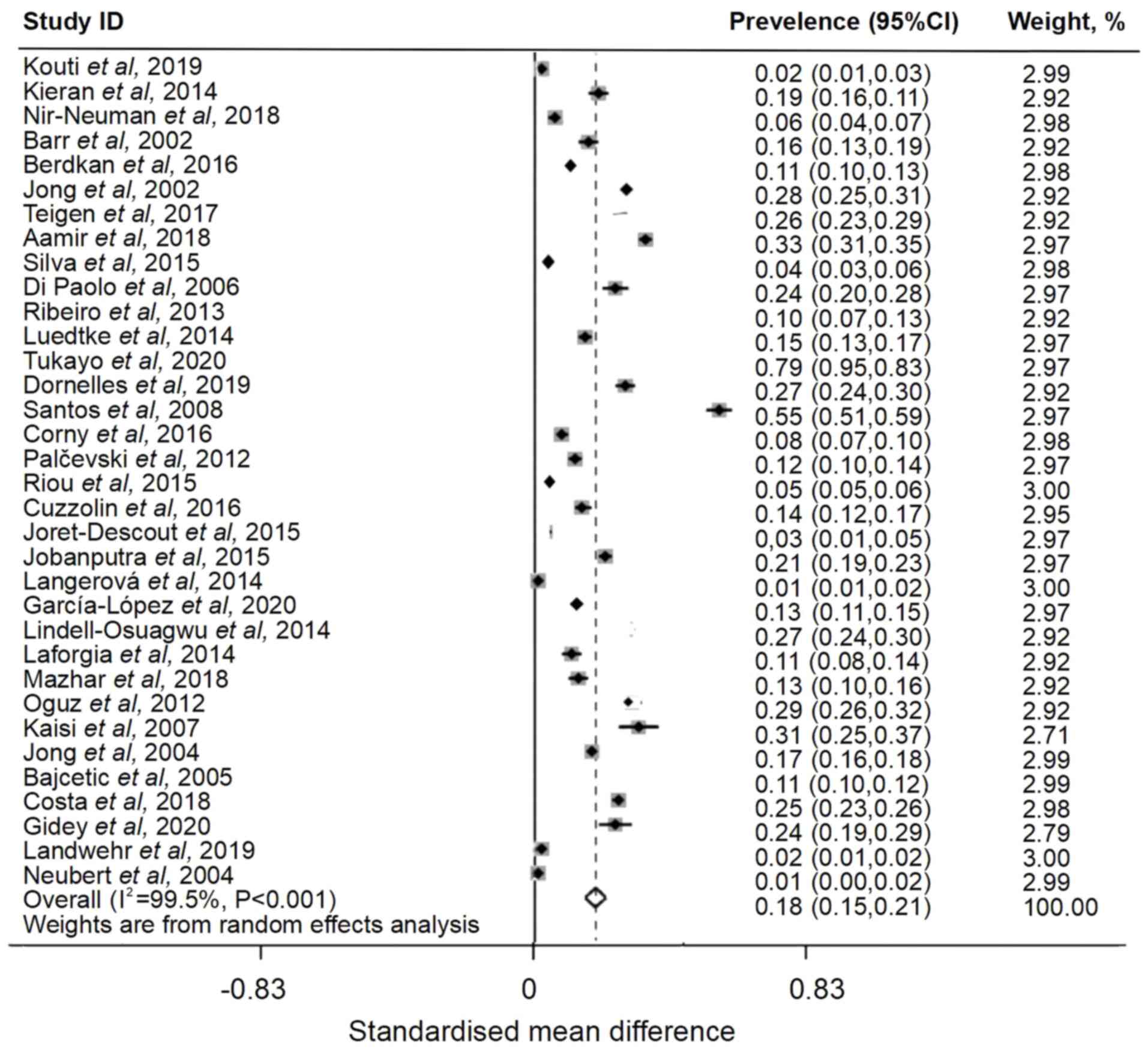

Overall pooled prevalence of off-label

or unlicensed drug use among pediatric patients

The prevalence of off-label prescriptions given to

admitted pediatric patients was 46% (95% CI, 0.38-0.54), which was

decreased compared with overall prevalence and had high

heterogeneity (I2=99.7%) (Fig. 3). Of 45 included articles, 34

reported unlicensed drug usage in hospitalized children. A total of

10,126 prescriptions were unlicensed in the included articles. The

global pooled prevalence rate was 18% (I2=99.5%; 95% CI,

0.15-0.21; Fig. 4).

Subgroup analysis of prevalence of

off-label and unlicensed drug use according to the continent of

study

The subgroup analysis determined the combined

prevalence of off-label and unlicensed drugs used on each

continent. Africa had the highest prevalence rate at 66% (95% CI,

0.17-1.15), followed by Asia at 65% (95% CI, 0.52-0.78), South

America at 63% (95% CI, 0.42-0.84), North America at 56% (95% CI,

0.36-0.76), Australia at 56% (95% CI, 0.51-0.60) and Europe at 49%

(95% CI, 0.36-0.62) (Table

SII).

Subgroup analysis showed that Australia had the

highest prevalence of off-label drug use among pediatric patients

at 54% (95% CI, 0.50-0.58), followed by Asia at 52% (95% CI,

0.42-0.63), South America at 45% (95% CI, 0.39-0.50), Europe at 42%

(95% CI, 0.29-0.55) and North America at 38% (95% CI, 0.36-0.41)

(Table SII). The prevalence of

unlicensed medication prescriptions among pediatric patients in

South America was the highest at 36% (95% CI, 0.20-0.51), followed

by Africa at 27% (95% CI, 0.20-0.34), Asia at 25% (95% CI,

0.16-0.34), Europe at 12% (95% CI, 0.09-0.15), North America at 8%

(95% CI, 0.06-0.09) and Australia at 2% (95% CI, 0.02-0.03)

(Table SII).

Publication bias

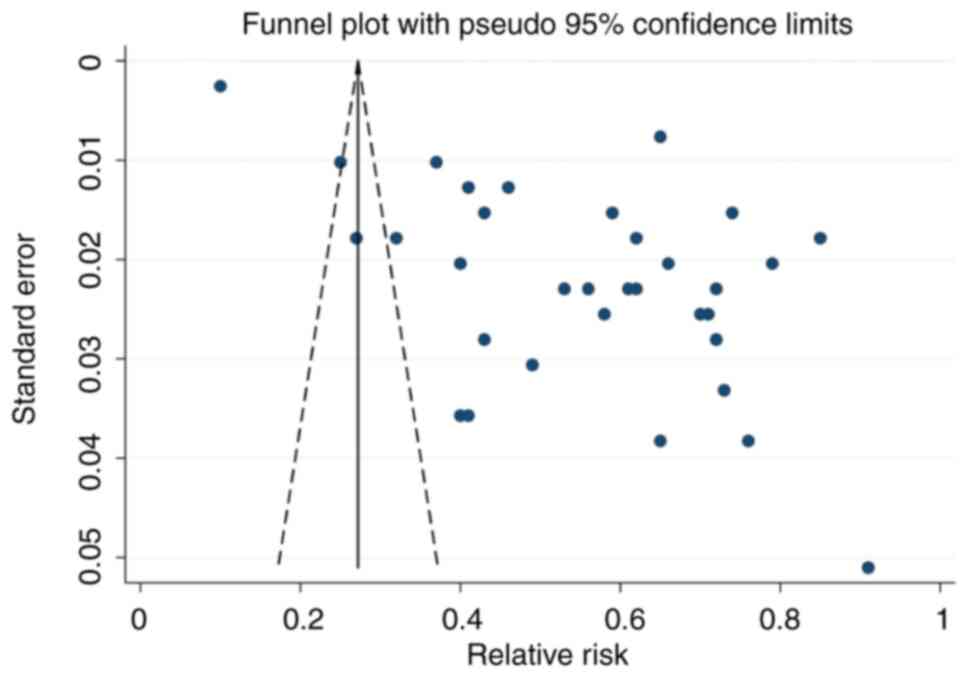

Funnel plot analysis indicated notable publication

bias based on the asymmetric shape of the funnel (Fig. 5). The range of effect sizes for

most studies was between 0.40 and 0.80, with a low standard error.

The regression-based Egger's test was significant (P=0.017), which

indicated heterogeneity and publication bias (Fig. S4). Non-parametric trim-and-fill

analysis identified and corrected funnel plot asymmetries in

studies reporting off-label and unlicensed prescribing. Despite a

degree of publication bias, the results of the present study could

still be considered robust.

Discussion

As available standardized pediatric prescription

data are limited, off-label and unlicensed medications are

frequently prescribed to pediatric patients. The prescription of

off-label and unlicensed drugs has been escalating among children

recently, and current regulations for the use of prescription

medications are considered ineffective in the pharmaceutical

industry (62). The present study

aimed to assess the global prevalence of off-label and unlicensed

drug prescriptions given to hospitalized children through

meta-analysis. All prescriptions in the included studies originated

from data obtained from patients that were admitted to the NICU,

PICU or general ward. Of 45 studies, 34 reported the prevalence of

prescriptions of both off-label and unlicensed medication given to

children. The overall global prevalence of off-label and unlicensed

medications among patients in the PICU or NICU was 56%. The highest

prevalence was in Asia (62%), followed by South America (53%) and

Europe (29.9%).

Following the exclusion of studies following

sensitivity analysis, the combined prevalence of off-label and

unlicensed medication use was 55% compared with an overall global

prevalence of 56% in all included studies. A previous meta-analysis

of 6 studies reported that off-label prescriptions constituted

93.5% of all medications prescribed (63); however, the incidence of unlicensed

medications was only 3.9%. A large proportion of medications were

prescribed to children <2 years of age in the aforementioned

meta-analysis (63). The present

study demonstrated that the prevalence of off-label prescriptions

given to admitted pediatric patients was 46% and that of unlicensed

prescriptions was 18%. A previous study demonstrated that the

frequency of off-label medication use to children was 14.5-35%,

although no meta-analysis or statistical analysis was performed

(64). Differences between the

aforementioned study and the present study may be attributed to

different sample sizes and examination of antipsychotic drugs

specifically in the previous study, whereas the present study

examined all types of prescribed drug. Differences could also be

attributed to differences in drug regulatory standards and

pharmaceutical budgets between different countries (13,14).

Subgroup analysis according to continent of study indicated the

overall pooled prevalence of off-label and unlicensed drugs used

Africa had the highest prevalence rate at 66%, followed by Asia at

65%, South America at 63%, North America at 56%, Australia at 56%

and Europe at 49%. As high heterogeneity was demonstrated across

the studies in the present meta-analysis, further studies on the

prevalence of off-label and unlicensed prescriptions to

hospitalized children are necessary.

A standardized definition of off-label and

unlicensed medications may be required to accurately assess their

frequency of use, risk factors and impact. Further prospective

clinical studies should evaluate the efficacy and safety of these

medications in the pediatric population. The prescription of

off-label and unlicensed drugs in pediatric primary healthcare

necessitates further investigation of their use by regulatory

agencies and the pharmaceutical industry. The elimination of the

prescription of off-label and unlicensed drugs may potentially

increase drug safety in children. In the future, clinicians could

report suspected adverse drug reactions, such as unipolar

depression, to relevant authorities to increase drug safety in

children.

The prescription of off-label and unlicensed drugs

may expose children to drug toxicity and adverse drug effects, due

to the pressure on clinicians to treat critically ill neonatal

patients. In addition to empirical treatment methods (the doctor's

treatment experience in the course of use), implementation of

enhanced safe drug usage is imperative. Collaborative engagement

between the pharmaceutical industry, clinical academics, healthcare

professionals, parents and national regulatory bodies is key to

prevent children from becoming 'therapeutic orphans'. To decrease

the risk of drug misuse in the pediatric population, pharmacists

should review medication charts. This, as well as drug labeling

(including patient and physician instructions), is an effective

method to avoid drug misuse (65).

Strict supervision of drug administration can also avoid adverse

drug reactions. To develop pediatric formulations,

multi-collaborative efforts of researchers, medical staff, industry

regulators and policymakers are required. Further evidence to

support the safety and efficacy of off-label drug prescriptions to

children and communication with legal guardians about proposed

treatment is essential in the future.

The present meta-analysis analyzed studies that

reported on the prevalence of off-label and unlicensed

prescriptions among pediatric patients, and had varying study

sample sizes, durations and designs. Different countries may

require distinct licensing information and drug package-leaflet

data. Additionally, only 2 studies each originated from North

America and Australia, which limited the scope of the present

study; therefore further research on this topic in North America

and Australia is warranted. These limitations potentially

contributed to the heterogeneity observed in the present analysis.

To address this high heterogeneity, the present study investigated

the source of heterogeneity, conducted sensitivity analysis and

used the random-effects model. In addition, PRISMA was used to

minimize reporting bias. To the best of our knowledge, the present

study is the first to report the pooled prevalence of off-label and

unlicensed prescriptions in hospitalized pediatric patients.

In conclusion, the present meta-analysis

demonstrated that the prevalence of off-label and unlicensed

prescriptions among pediatric patients was substantial and varied

across geographical regions. The differences between studies may be

attributed to methodological discrepancies and differences in

licensing and drug leaflet information across countries; therefore,

it could be recommended that drug authorities standardize pediatric

prescription practices in future.

Supplementary Material

Sensitivity analysis indicating that

the pooled prevalence remains notably stable upon exclusion of each

study.

Sensitivity analysis to assess the

impact of excluding studies that had a small sample size of

prescriptions.

Forest plot of prevalence of off-label

and unlicensed prescriptions in a pediatric population after

excluding studies that had a small sample size of

prescriptions.

Regression-based Egger's test

examining off-label and unlicensed prescriptions.

Quality assessment of included

articles using the Joanna Briggs Institute critical assessment

checklist.

Subgroup analysis by study design and

continent.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported by the Research Project

on Traditional Chinese Medicine in Heilongjiang Province (grant no.

ZHY2022-080).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

XY, JG and LY curated and analyzed the data. YT and

OB conceived the study and revised the manuscript. OB wrote, edited

and reviewed the manuscript. YT and OB confirm the authenticity of

all the raw data All authors have read and approved the final

version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Moulis F, Durrieu G and Lapeyre-Mestre M:

Off-label and unlicensed drug use in children population. Therapie.

73:135–149. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

van Riet-Nales DA, Schobben AF, Egberts TC

and Rademaker CM: Effects of the pharmaceutical technologic aspects

of oral pediatric drugs on patient-related outcomes: A systematic

literature review. Clin Ther. 32:924–938. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Chen J, Luo X, Qiu H, Mackey V, Sun L and

Ouyang X: Drug discovery and drug marketing with the critical roles

of modern administration. Am J Transl Res. 10:4302–4312.

2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Thompson G, Barker CI, Folgori L, Bielicki

JA, Bradley JS, Lutsar I and Sharland M: Global shortage of

neonatal and paediatric antibiotic trials: Rapid review. BMJ Open.

7(e016293)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Joseph PD, Craig JC and Caldwell PHY:

Clinical trials in children. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 79:357–369.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Gore R, Chugh PK, Tripathi CD, Lhamo Y and

Gautam S: Pediatric off-label and unlicensed drug use and its

implications. Curr Clin Pharmacol. 12:18–25. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Paine MF: Therapeutic disasters that

hastened safety testing of new drugs. Clin Pharmacol Ther.

101:430–434. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Leandro JA: ‘Risk-free rest and sleep:’

Jornal do Médico (Portugal) and the thalidomide disaster,

1960-1962. Hist Cienc Saude Manguinhos. 27:15–32. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar : (In Portuguese,

English).

|

|

9

|

Nir-Neuman H, Abu-Kishk I, Toledano M,

Heyman E, Ziv-Baran T and Berkovitch M: Unlicensed and off-label

medication use in pediatric and neonatal intensive care units: No

change over a decade. Adv Ther. 35:1122–1132. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Landwehr C, Richardson J, Bint L, Parsons

R, Sunderland B and Czarniak P: Cross-sectional survey of off-label

and unlicensed prescribing for inpatients at a paediatric teaching

hospital in Western Australia. PLoS One.

14(e0210237)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Kleeblatt J, Betzler F, Kilarski LL,

Bschor T and Köhler S: Efficacy of off-label augmentation in

unipolar depression: A systematic review of the evidence. Eur

Neuropsychopharmacol. 27:423–441. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Shaikh M and Gandjour A: Pharmaceutical

expenditure and gross domestic product: Evidence of simultaneous

effects using a two-step instrumental variables strategy. Health

Econ. 28:101–122. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Mori AT, Meena E and Kaale EA: Economic

cost of substandard and falsified human medicines and cosmetics

with banned ingredients in Tanzania from 2005 to 2015: A

retrospective review of data from the regulatory authority. BMJ

Open. 8(e021825)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Moreira M and Sarraguça M: How can oral

paediatric formulations be improved? A challenge for the XXI

century. Int J Pharm. 590(119905)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Leucht S, Corves C, Arbter D, Engel RR, Li

C and Davis JM: Second-generation versus first-generation

antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia: A meta-analysis. Lancet.

373:31–41. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

International Monetary Fund: Real GDP

growth. [Internet]. International Monetary Fund, Geneva, 2020.

https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/NGDP_RPCH@WEO/OEMDC/ADVEC/WEOWORLD.

Accessed August 7, 2020.

|

|

17

|

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron

I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan

SE, et al: The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for

reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 372(n71)2021.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Barker TH, Stone JC, Sears K, Klugar M,

Tufanaru C, Leonardi-Bee J, Aromataris E and Munn Z: The revised

JBI critical appraisal tool for the assessment of risk of bias for

randomized controlled trials. JBI Evid Synth. 21:494–506.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Turner S, Nunn AJ, Fielding K and Choonara

I: Adverse drug reactions to unlicensed and off-label drugs on

paediatric wards: A prospective study. Acta Paediatr. 88:965–968.

1999.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Conroy S, McIntyre J and Choonara I:

Unlicensed and off label drug use in neonates. Arch Dis Child Fetal

Neonatal Ed. 80:F142–F144. 1999.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Pandofini C, Impicciatore P, Provasi D,

Rocchi F, Campi R and Bonati M: Italian Paediatric Off-label

Collaborative Group. Off-label use of drugs in Italy: A

prospective, observational and multicentre study. Acta Paediatr.

91:339–347. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Barr J, Brenner-Zada G, Heiman E, Pareth

G, Bulkowstein M, Greenberg R and Berkovitch M: Unlicensed and

off-label medication use in a neonatal intensive care unit: A

prospective study. Am J Perinatol. 19:67–72. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Jong GW, van der Linden PD, Bakker EM, van

der Lely N, Eland IA, Stricker BH and van den Anker JN: Unlicensed

and off-label drug use in a paediatric ward of a general hospital

in the Netherlands. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 58:293–297.

2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Conroy S, Newman C and Gudka S: Unlicensed

and off label drug use in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia and other

malignancies in children. Ann Oncol. 14:42–47. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Jong GW, Eland IA, Sturkenboom MC, van den

Anker JN and Strickerf BH: Unlicensed and off-label prescription of

respiratory drugs to children. Eur Respir J. 23:310–313.

2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Neubert A, Dormann H, Weiss J, Egger T,

Criegee-Rieck M, Rascher W, Brune K and Hinz B: The impact of

unlicensed and off-label drug use on adverse drug reactions in

paediatric patients. Drug Saf. 27:1059–1067. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Bajcetic M, Jelisavcic M, Mitrovic J,

Divac N, Simeunovic S, Samardzic R and Gorodischer R: Off label and

unlicensed drugs use in paediatric cardiology. Eur J Clin

Pharmacol. 61:775–779. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Di Paolo ER, Stoetter H, Cotting J, Frey

P, Gehri M, Beck-Popovic M, Tolsa JF, Fanconi S and Pannatier A:

Unlicensed and off-label drug use in a Swiss paediatric university

hospital. Swiss Med Wkly. 136:218–222. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Kaisi T, Maponga CC, Gavaza P and

Pazvakavambwa IE: An assessment of the extent of use of off-license

and unlicensed drugs on children at Parirenyatwa Hospital in

Harare, Zimbabwe. East Cent Afr J Pharm Sci. 9:3–7. 2007.

|

|

30

|

Santos DB, Clavenna A, Bonati M and Coelho

HL: Off-label and unlicensed drug utilization in hospitalized

children in Fortaleza, Brazil. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 64:1111–1118.

2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Bavdekar SB, Sadawarte PA, Gogtay NJ, Jain

SS and Jadhav S: Off-label drug use in a pediatric intensive care

unit. Indian J Pediatr. 76:1113–1118. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Lass J, Käär R, Jõgi K, Varendi H,

Metsvaht T and Lutsar I: Drug utilisation pattern and off-label use

of medicines in Estonian neonatal units. Eur J Clin Pharmacol.

67:1263–1271. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Palčevski G, Skočibušić N and

Vlahović-Palčevski V: Unlicensed and off-label drug use in

hospitalized children in Croatia: A cross-sectional survey. Eur J

Clin Pharmacol. 68:1073–1077. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Oguz SS, Kanmaz HG and Dilmen U: Off-label

and unlicensed drug use in neonatal intensive care units in Turkey:

The old-inn study. Int J Clin Pharm. 34:136–141. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Ballard CD, Peterson GM, Thompson AJ and

Beggs SA: Off-label use of medicines in paediatric inpatients at an

Australian teaching hospital. J Paediatr Child Health. 49:38–42.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Kieran EA, O'Callaghan N and O'Donnell CP:

Unlicensed and off-label drug use in an Irish neonatal intensive

care unit: A prospective cohort study. Acta Paediatr.

103:e139–e142. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Silva J, Flor-de-Lima F, Soares H and

Guimarães H: Off-label and unlicensed drug use in neonatology:

Reality in a Portuguese University Hospital. Acta Med Port.

28:297–306. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Lee JL, Redzuan AM and Shah NM: Unlicensed

and off-label use of medicines in children admitted to the

intensive care units of a hospital in Malaysia. Int J Clin Pharm.

35:1025–1029. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Ribeiro M, Jorge A and Macedo AF:

Off-label drug prescribing in a Portuguese paediatric emergency

unit. Int J Clin Pharm. 35:30–36. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Lindell-Osuagwu L, Hakkarainen M, Sepponen

K, Vainio K, Naaranlahti T and Kokki H: Prescribing for off-label

use and unauthorized medicines in three paediatric wards in

Finland, the status before and after the European Union Paediatric

regulation. J Clin Pharm Ther. 39:144–153. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Laforgia N, Nuccio MM, Schettini F,

Dell'Aera M, Gasbarro AR, Dell'Erba A and Solarino B: Off-label and

unlicensed drug use among neonatal intensive care units in Southern

Italy. Pediatr Int. 56:57–59. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Langerová P, Vrtal J and Urbánek K:

Incidence of unlicensed and off-label prescription in children.

Ital J Pediatr. 40(12)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Luedtke KE and Buck ML: Evaluation of

off-label prescribing at a children's rehabilitation center. J

Pediatr Pharmacol Ther. 19:296–301. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Riou S, Plaisant F, Boulch DM, Kassai B,

Claris O and Nguyen KA: Unlicensed and off-label drug use: A

prospective study in French NICU. Acta Paediatr. 104:e228–e231.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Joret-Descout P, Prot-Labarthe S, Brion F,

Bataille J, Hartmann JF and Bourdon O: Off-label and unlicensed

utilisation of medicines in a French paediatric hospital. Int J

Clin Pharm. 37:1222–1227. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Jobanputra N, Save SU and Bavdekar SB:

Off-label and unlicensed drug use in children admitted to pediatric

intensive care units (PICU). Int J Risk Saf Med. 27:113–121.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Berdkan S, Rabbaa L, Hajj A, Eid B,

Jabbour H, El Osta NE, Karam L and Khabbaz LR: Comparative

assessment of off-label and unlicensed drug prescriptions in

children: FDA versus ANSM guidelines. Clin Ther. 38:1833–1844.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Cuzzolin L and Agostino R: Off-label and

unlicensed drug treatments in neonatal intensive care units: An

Italian multicentre study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 72:117–123.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Corny J, Bailey B, Lebel D and Bussières

JF: Unlicensed and off-label drug use in paediatrics in a

mother-child tertiary care hospital. Paediatr Child Health.

21:83–87. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Ramadaniati HU, Tambunan T, Khairani S and

Adisty HS: Off-label and unlicensed prescribing in pediatric

inpatients with nephrotic syndrome in a major teaching hospital: An

Indonesian context. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 10:355–359. 2017.

|

|

51

|

Tefera YG, Gebresillassie BM, Mekuria AB,

Abebe TB, Erku DA, Seid N and Beshir HB: Off-label drug use in

hospitalized children: A prospective observational study at Gondar

University Referral Hospital, Northwestern Ethiopia. Pharmacol Res

Perspect. 5(e00304)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Teigen A, Wang S, Truong BT and Bjerknes

K: Off-label and unlicensed medicines to hospitalised children in

Norway. J Pharm Pharmacol. 69:432–438. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Costa HTML, Costa TX, Martins RR and

Oliveira AG: Use of off-label and unlicensed medicines in neonatal

intensive care. PLoS One. 13(e0204427)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Mazhar F, Akram S, Haider N, Hadi MA and

Sultana J: Off-label and unlicensed drug use in hospitalized

newborns in a Saudi tertiary care hospital: A cohort study. Int J

Clin Pharm. 40:700–703. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Aamir M, Khan JA, Shakeel F, Shareef R and

Shah N: Drug utilization in neonatal setting of Pakistan: Focus on

unlicensed and off label drug prescribing. BMC Pediatr.

18(242)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Dornelles AD, Calegari LH, de Souza L,

Ebone P, Tonelli TS and Carvalho CG: The unlicensed and off-label

prescription of medications in general paediatric ward: An

observational study. Curr Pediatr Rev. 15:62–66. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Kouti L, Aletayeb M, Aletayeb SMH, Hardani

AK and Eslami K: Pattern and extent of off-label and unlicensed

drug use in neonatal intensive care units in Iran. BMC Pediatr.

19(3)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Tukayo BLA, Sunderland B, Parsons R and

Czarniak P: High prevalence of off-label and unlicensed paediatric

prescribing in a hospital in Indonesia during the period Aug.-Oct.

2014. PLoS One. 15(e0227687)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Gidey MT, Gebretsadkan YG, Tsadik AG,

Welie AG and Assefa BT: Off-label and unlicensed drug use in Ayder

comprehensive specialized hospital neonatal intensive care unit.

Ital J Pediatr. 46(41)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

García-López I, Vendrell MCM, Romero IM,

de Noriega I, González JB and Martino-Alba R: Off-label and

unlicensed drugs in pediatric palliative care: A prospective

observational study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 60:923–932.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

AlAzmi A, Alasmari Z, Yousef C, Alenazi A,

AlOtaibi M, AlSaedi H, AlShaikh A, AlObathani A, Ahmed O,

Goronfolah L and Alahmari M: Off-Label drug use in pediatric

out-patient care: A multi-center observational study. Hosp Pharm.

56:690–696. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Tsukamoto K, Carroll KA, Onishi T,

Matsumaru N, Brasseur D and Nakamura H: Improvement of pediatric

drug development: Regulatory and practical frameworks. Clin Ther.

38:574–581. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Shakeel S, Iffat W, Nesar S, Zaidi H and

Jamshed S: Exploratory findings of prescribing unlicensed and

off-label medicines among children and neonates. Integr Pharm Res

Pract. 9:33–39. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Andrade SRA, Santos PANM, Andrade PHS and

da Silva WB: Unlicensed and off-label prescription of drugs to

children in primary health care: A systematic review. J Evid Based

Med. 13:292–300. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Turner S, Gill A, Nunn T, Hewitt B and

Choonara I: Use of ‘off-label’ and unlicensed drugs in paediatric

intensive care unit. Lancet. 347:549–550. 1996.PubMed/NCBI

|