Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most prevalent

types of cancer worldwide, with a varying incidence from country to

country. In the United States of America, it is the third most

commonly diagnosed cancer in both men and women, while it is the

most diagnosed cancer among men and the third most diagnosed cancer

among women in Saudi Arabia, as of a 2018 report (1). The incidence of CRC is increasing in

Saudi Arabia, with a median detection age of 55 years in women and

60 years in men (2). Despite being

less common in Saudi Arabia compared with some other countries, CRC

is the leading cause of cancer mortality among men and top five in

women (3). This represents a

significant health concern. The Saudi Ministry of Health aims to

reduce the impact of CRC by introducing screening and diagnostic

programs. CRC may occur infrequently due to genetic cancer

syndromes or inflammatory bowel disorders. However, even if they

don't meet the criteria for hereditary CRC, ~20% of all cases of

this disorder are considered to have some degree of familial risk

(4).

Certain risk factors, such as diet, smoking and

obesity, are associated with some of the most common forms of

cancer, including breast, gynaecological, liver and CRCs (5,6).

Obesity is characterized by the accumulation of excess body fat,

which leads to a higher risk of metabolic syndrome. The global

obesity epidemic is a significant public health issue, and Saudi

Arabia is one of the countries with the highest obesity rates, at

24% (7). As obesity becomes more

prevalent, research into the link between excess weight and CRC has

become more prominent. Based on multiple studies, obese patients

with CRC tend to have shorter survival rates, as discussed

previously (8,9)

Insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia are

significant contributors to CRC (10,11).

Insulin resistance is a form of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes mellitus

(DM) is a general term that encompasses a wide range of metabolic

disorders, with chronic hyperglycaemia being the most common. Type

2 diabetes affects 18.3% of the population in Saudi Arabia

(12). Although various

epidemiological studies have shown that the prevalence of CRC is

higher among diabetic patients than non-diabetic individuals, some

studies, particularly those investigating the risk of CRC, have

considered type II diabetes as more prevalent and relevant

(13,14).

The liver plays a vital role in metabolism by

converting carbohydrates, fats, proteins and lipids into active

forms that circulate in the blood (15). Additionally, it functions to

detoxify harmful substances and produce essential enzymes for cell

growth and energy expenditure (16). Abnormalities in liver function can

result in various diseases including CRC (17) and cirrhosis (18). A recent UK biobank analysis

suggests that higher levels of alanine transaminase (ALT),

aspartate transferase (AST), total bilirubin (TBIL), γ-glutamyl

transferase (GGT), prothrombin time (PT) and albumin (ALB) may be

associated with lower risk for CRC (19). Studies have also found associations

between markers of liver function such as ALT bilirubin and albumin

with chronic illnesses including CRC as well as increased toxicity

among patients diagnosed with this type of cancer (19-21).

The purpose of the present study was to provide an

updated report on the rates of obesity and diabetes among CRC

patients in Saudi Arabia and to investigate how these conditions

were associated with the elevation of liver metabolite markers such

as ALT, AST, bilirubin, GGT, ALB and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH).

By doing so, the study aims to provide further evidence regarding

the role played by obesity and diabetes as widespread factors in

Saudi Arabia in the progression of CRC.

Patients and methods

Patient data

The present study was a retrospective chart review

that utilized medical records from the Saudi Ministry of National

Guards Hospital and Health Affairs, which is a tertiary hospital

located in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The study was approved by the King

Abdullah International Medical Research Center Institutional Review

Board (IRB), Ministry of National Guard-Health Affairs (approval

no. NRC22R/144/03). The IRB approved the waiver of informed consent

when using medical records since research involves no more than

minimal risk to the subjects.

The selection criteria included all medical records

of patients who were diagnosed with CRC between January 2015 and

December 2019 and met the inclusion criteria, which was a confirmed

CRC diagnosis. The present study employed a non-probability

consecutive sampling technique to select the patients, which means

all conveniently available populations were included. The

confounding variables were addressed through matching. The

assessment of each patient included their age, sex, body mass index

(BMI), complete blood cell count, haematocrit, haemoglobin,

platelet count, liver profile (TBIL, ALB, GGT, direct bilirubin,

AST, LDH, ALT and PT), kidney profile (creatinine, estimated

glomerular filtration rate) and diabetes status. Exclusion criteria

included patients with incomplete clinical records or missing

treatment information. The study included 147 women and 172 men.

The BMI was calculated according to standard scale: BMI ≥30 was

obese, ≥25 was overweight, ≥18.5 was normal and <18.5

kg/m2 was underweight as mentioned previously (22).

Statistical analysis

The present study used Epi Info 7.2.5 software

(trademark of CDC, USA) for statistical analysis of the data, a

tool designed for epidemiological statistics in public health

practice. To assess significance, a one-tailed P-value and employed

Pearson's χ2 test was used. P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference. Significance

calculations were based on a confidence interval of 95%. In the

tables, (Row%) refers to row percentage which represents the

proportion or percentage of a specific row's value in relation to

the total of that row. Similarly, (Col%) refers to column

percentage which represents the proportion or percentage of a

specific column's value in relation to the total of that column.

The survival data was created by OncoLnc data portal (http://www.oncolnc.org/), which links survival data

from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) to mRNA, microRNA and long

non-coding RNA expression levels. The data was downloaded on July

1, 2023(23).

Results

Age groups and CRC prevalence

The present study reviewed 319 patients when

investigating the prevalence of CRC among different age groups

between January 2015 and December 2019 (Table I). The participants were divided

into four categories: i) Under 30 years; ii) 30-49 years; iii)

50-59 years; and iv) ≥60 years. Reviewing CRC frequencies showed

that there were only 3 individuals under the age of 30, while there

were 70 between the ages of 30 and 49 years, 115 between the ages

of 50 and 59 years, and 131 ≥60 years (Table I). The groups 50-59 years and ≥60

years had higher patient percentages, at 36.05 and 41.07%,

respectively. The other two groups of 30-49 years and <30 years

had less members, at 21.94 and 0.94%, respectively. The age range

for males was 24-95 years old, while that for females was 36-87

years old. The median age for the entire sample was 57 years, while

the median age was 58 years for men and 57 years for women.

Applying the null hypothesis revealed that age classification had

significant P-value (P<0.01) in comparison to the healthy

control (Table I).

| Table IPrevalence of colorectal cancer in

correlation with age. |

Table I

Prevalence of colorectal cancer in

correlation with age.

| Age in years | n (%) | One-tailed

P-value |

|---|

| <30 | 3 (0.94) | 0.0001 |

| 30-49 | 70 (21.94) | 0.0034 |

| 50-59 | 115 (36.05) | 0.0067 |

| ≥60 | 131 (41.07) | 0.0082 |

| Total | 319 (100.00) | - |

Sex

In order to gain a deeper understanding of the

prevalence of CRC, an analysis of sex contributions to the

incidence of CRC was conducted. The participants were divided into

two categories based on sex: Male and female. The findings showed a

sex disparity in the incidence rates of CRC across age

demographics. Specifically, among female patients, 55 (37.41%) were

≥60 years, 57 (38.78%) were 50-59 years, 35 (23.81%) were 30-49

years and 0 (0.0%) were <30 years. Meanwhile, among male

patients, 76 (44.19%) were ≥60, 58 (33.72%) were 50-59 years, 35

(20.35%) were 30-49 years and 3 (1.74%) were <30 years (Table II).

| Table IIInvestigating the prevalence of

colorectal cancer based on sex. |

Table II

Investigating the prevalence of

colorectal cancer based on sex.

| | Age in years | |

|---|

| Sex | <30 | 30-49 | 50-59 | ≥60` | Total |

|---|

| Female | 0 | 35 | 57 | 55 | 147 |

|

Row% | 0.00 | 23.81 | 38.78 | 37.41 | 100.00 |

|

Col% | 0.00 | 50.00 | 49.57 | 41.98 | 46.08 |

| Male | 3 | 35 | 58 | 76 | 172 |

|

Row% | 1.74 | 20.35 | 33.72 | 44.19 | 100.00 |

|

Col% | 100.00 | 50.00 | 50.43 | 58.02 | 53.92 |

| Total | 3 | 70 | 115 | 131 | 319 |

|

Row% | 0.94 | 21.94 | 36.05 | 41.07 | 100.00 |

|

Col% | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

This analysis revealed that males had a higher

percentage of CRC incidence compared with females in two age

groups: ≥60 and <30 years. Specifically, the incidence rate of

CRC among males was 16% higher for those ≥60 years and 100% for

those <30 years when compared with females of the same age

groups. These results may be of value in developing sex-specific

strategies for the prevention and treatment of CRC.

BMI

The results presented in Table III present the investigation into

the relationship between BMI measurements and their association

with CRC. Patients were classified into normal, underweight,

overweight or obese categories based on BMI. Frequency and

percentage data were obtained for each group by sex. The results

reveal that the majority of patients with CRC 185 (57.9%) are

overweight, which includes obese patients. Notably, participants

with a normal BMI had a higher occurrence rate of CRC 112 (35.11%)

compared with those with an underweight BMI category 22 (6.90%).

This emphasizes the significance of maintaining lower BMI even if

less than normal healthy weight levels when it comes to preventing

and managing this type of cancer effectively. These numbers failed

to confirm association statistically, as χ2=5.38 and

P=0.145.

| Table IIIAssociation between obesity (body

mass index) and sex of colorectal cancer. |

Table III

Association between obesity (body

mass index) and sex of colorectal cancer.

| | BMI status | |

|---|

| Sex | Normal | Obese | Overweight | Underweight | Total |

|---|

| Female, n (%) | 45 (30.61) | 55 (37.41) | 36 (24.49) | 11 (7.48) | 147 (100.00) |

| Male, n (%) | 67 (38.95) | 45 (26.16) | 49 (28.49) | 11 (6.40) | 172 (100.00) |

| Total, n (%) | 112 (35.11) | 100 (31.35) | 85 (26.65) | 22 (6.90) | 319 (100.00) |

Obesity and diabetes

The study investigated the link between

obesity-related complications and diabetes incidence in 319

participants with CRC. The results, presented in Table IV, showed that out of a total of

147 women and 172 men, only 63 female patients (42.86%) did not

have diabetes while the rest did; similarly, for males, only 59

(34.30%) did not have diabetes compared with 113 (65.70%) males who

did. Measurement of risk ratio, risk differences and odd ratio

turn-out to be 1.25, 8.55 and 1.44, respectively, at 95% confidence

interval. The positive risk and odd ratio in these findings

strongly suggest an association between CRC and diabetes among both

sexes (P=0.05). Although more research is required to determine

precisely how this connection occurs, these results indicate that

people with type II Diabetes are at greater risk for developing CRC

compared with those without it due to their condition caused by

excessive body weight which can lead them into a higher rate of

health problems associated with overweight or obese

individuals.

| Table IVAssociation between colorectal cancer

with diabetes among both male and female populations. |

Table IV

Association between colorectal cancer

with diabetes among both male and female populations.

| | Diabetes

(yes/no) | |

|---|

| Sex | No | Yes | Total |

|---|

| Female, n (%) | 63 (42.86) | 84 (57.14) | 147 (100.00) |

| Male, n (%) | 59 (34.30) | 113 (65.70) | 172 (100.00) |

| Total, n (%) | 122 (38.24) | 197 (61.76) | 319 (100.00) |

Obesity and liver disease

The present study examined liver metabolite

abnormalities in patients with CRC who were overweight or obese and

diabetic to investigate the association between excess weight,

diabetes and liver function markers. The objective was to establish

a possible link between these factors. The results revealed that

106 (33.23%) of obese patients with CRC had significantly elevated

levels of GGT enzyme (P=0.026; Table

V). However, most overweight or obese patients with CRC showed

normal levels of other indicators including ALT, LDH, AST, ALB and

TBIL (Table SI, Table SII, Table SIII, Table SIV and Table SV). Improving our understanding of

how obesity and diabetes affect the liver can be beneficial for

managing related health issues among CRC sufferers.

| Table VAssociation between high body mass

index and liver function metabolites in patients with colorectal

cancer. |

Table V

Association between high body mass

index and liver function metabolites in patients with colorectal

cancer.

| BMI vs. liver

GGT | n (%) |

|---|

| Abnormal liver

GGT | 106 (33.23) |

| Not overweight with

abnormal GGT | 135 (42.32) |

| Normal liver

GGT | 78 (24.45) |

| Total | 319 (100.00) |

Obesity and GGT

In 197 diabetic patients with CRC, the present study

examined a link between overweight/or obesity and GGT levels when

compared to 122 non-diabetic patients with CRC in Table VI. The subjects were split into

four groups based on their GGT and whether they had diabetes. The

first group was made up of 33 people (27.05%), all of whom had a

normal BMI and did not have diabetes. The second group was made up

of 45 individuals (22.84%) with diabetes and a normal BMI. The

third group had 38 patients (31.15%), none of whom had diabetes but

whose BMI was abnormally high. The fourth group was made up of 16

patients (13%), all of whom had diabetes and an abnormal BMI. The

result of this categorization (data not shown) show that there were

more people with diabetes in the normal BMI group 45 (57.69%) than

people without diabetes 33 (42.31%) in the normal group. In the

group of people with an abnormal BMI, there were more people with

diabetes 68 (64.15%) than people without diabetes 38 (35.85%)

(P=0.04; Table VI).

| Table VIAssociation between body mass index,

GGT levels and diabetic status in patients with colorectal

cancer. |

Table VI

Association between body mass index,

GGT levels and diabetic status in patients with colorectal

cancer.

| | Diabetes

(yes/no) | |

|---|

| BMI vs. liver

GGT | No | Yes | Total |

|---|

| Abnormal, n

(%) | 38 (35.85) | 68 (64.15) | 106 (100.00) |

| NA, n (%) | 51 (37.78) | 84 (62.22) | 135 (100.00) |

| Normal, n (%) | 33 (42.31) | 45 (57.69) | 78 (100.00) |

| Total, n (%) | 122 (38.24) | 197 (61.76) | 319 (100.00) |

Diabetes and GGT

The present study subsequently evaluated patients

with CRC exhibiting GGT abnormalities and further classified these

patients based on their diabetic status, as shown in Table VII. Out of the total 183

patients, 44 (55.70%) of the women were diabetic and 35 (44.30%)

were non-diabetic. By contrast, 71 (68.27%) of the men were

diabetic and 33 (31.73%) were non-diabetic. Notably, the risk

ratio, risk differences and odds ratio increased to 1.39, 12.57 and

1.71, respectively. These changes were significant (P=0.05).

| Table VIIAssociation between abnormal GGT

levels and diabetic status then weighted by sex in patients with

colorectal cancer. |

Table VII

Association between abnormal GGT

levels and diabetic status then weighted by sex in patients with

colorectal cancer.

| | Diabetes

(yes/no) | |

|---|

| Sex | No | Yes | Total |

|---|

| Female, n (%) | 35 (44.30) | 44 (55.70) | 79 (100.00) |

| Male, n (%) | 33 (31.73) | 71 (68.27) | 104 (100.00) |

| Total, n (%) | 68 (37.16) | 115 (62.84) | 183 (100.00) |

GGT level in public database

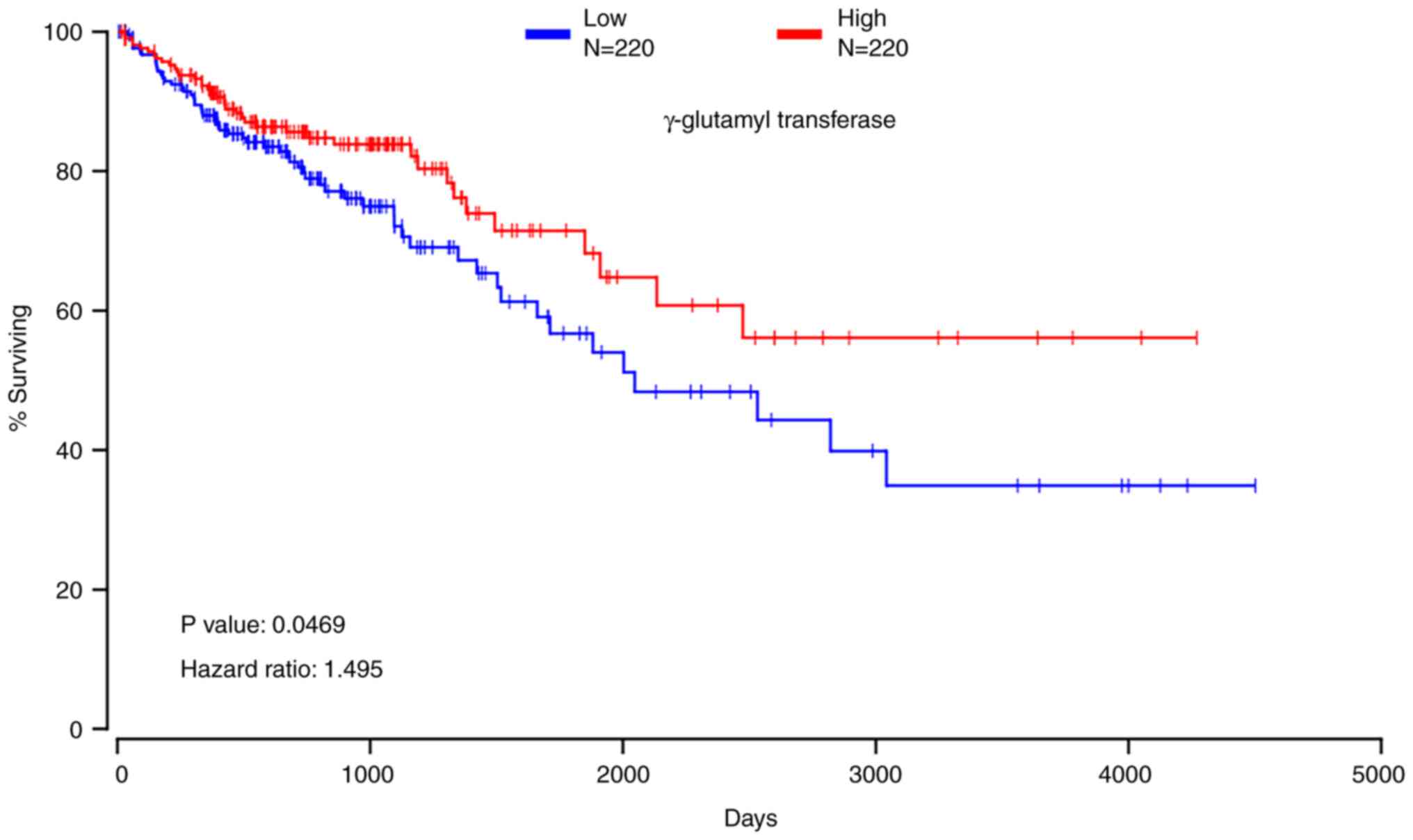

The present study analysed the levels of GGT6 in

colon adenocarcinoma, using TCGA database through Oncolnc tool. The

OncoLnc is a data portal that explore correlations between survival

data and gene expression from TCGA. Based on the data, the present

study reported a significant correlation (P=0.0469) between the

reduction in GGT6 and poor prognosis, as depicted in Fig. 1.

Discussion

CRC ranks as the third most prevalent type of cancer

worldwide and stands as the second leading cause of death from

cancer (1). Unhealthy lifestyle

habits, such as high BMI, smoking, alcohol consumption and poor

diet have been associated with CRC onset (13). Notably, several studies also link

hyperglycaemia to a higher incidence of CRC (24). Another study based on UK biobank

data highlights that liver enzymes play an essential role in CRC

progression (19). The present

research revealed that individuals diagnosed with CRC were more

likely to be diabetic or overweight. Furthermore, the present study

suggested that the GGT enzyme could serve as a valuable predictive

marker for detecting early-stage colon cancers.

A previous study conducted by The International

Agency for Research on Cancer stated that cancer incidence and

prevalence generally increase with age, particularly after the age

of 50(25). Additionally, it has

been established that there exists an association between sex and

CRC incidence, wherein men are at higher risk for developing CRC

compared with women. The same study revealed that ~23 out of every

100,000 men have this condition in comparison to only ~16 cases per

100,000 women (25). Most

participants in the present research were aged >50 years, which

further supports the link between patient age and CRC progression.

The finding also suggests sex differences play a role in

contributing towards the development of CRC as more males had this

disease compared with females.

Based on the present results, it appeared that

individuals aged ≥60 years had a significantly higher incidence

rate of CRC (41.07%), whereas those aged <30 years have an

incidence rate of only 0.94%. A two-tailed test conducted on the

data revealed a significant difference between the two groups, with

P=0.001. These results highlight the crucial role of age as a

predictive factor in preventing and treating CRC. Consequently,

there is a need to implement age-specific screening measures as a

critical preventive measure against this illness.

The analysis conducted on the incidence of CRC in

males and females shows that males may be at a higher risk of

developing this malignancy than females. The data suggested that,

despite advancements in cancer prevention and diagnosis, males

continue to have a higher incidence rate, indicating the urgency

for further research on colon cancer prevention. These findings

underscore the need for more focused and concerted efforts on colon

cancer prevention and research among males. Additionally, more

extensive research is required to better understand the underlying

mechanisms of this malignancy. Such understanding can help in

developing targeted and effective intervention strategies to curb

the rise in the incidence of CRC, especially among males, and

mitigate the burden of this disease on population health.

The connection between obesity and CRC is well

established, with the accumulation of visceral adipose tissue (VAT)

serving as a hallmark for this condition (26,27).

Lipoid tissues are responsible for secreting hormones such as

leptin, adiponectin and resistin, which can have an impact on

insulin resistance (28,29). The build-up of VAT in the body

creates a state of persistent low-grade systemic inflammation that

exacerbates insulin resistance (30,31).

The accumulation of VAT can cause persistent low-grade inflammation

that worsens insulin resistance and promotes tumour growth within

the microenvironment (32). The

measures used to determine obesity include both BMI and waist

circumference. The present study relied solely on BMI to evaluate

obesity, which provided further evidence for obesity being a

significant risk factor for CRC development as previously reported

(33).

Diabetes is associated with several types of cancer,

including colon, liver, pancreas, endometrial and breast cancer

(34). Both diabetes and obesity

lead to insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia in patients

triggering cell signalling pathways that cause tumorigenesis

(35). The insulin-like growth

factor 1 signalling pathway promotes cell proliferation while

inhibiting apoptosis in CRC cells (36). The present study showed a

prevalence of ≥60% for obesity and diabetes among patients with

CRC; hence it is imperative to manage these conditions to prevent

CRC.

In a recent UK biobank data analysis, it was found

that higher levels of ALT, AST, TBIL, GGT, PT and ALB are

associated with lower risk for CRC (19). Furthermore, previous studies have

indicated a correlation between liver function markers such as ALT,

bilirubin and ALB with chronic diseases, including CRC (19-21).

To better understand the impact of the GGT enzyme in CRC, the

current study examined the levels of GGT6 in colon adenocarcinoma

from TCGA database. The findings showed a significant association

(P=0.0469) between the downregulation of GGT6 and poor prognosis.

The present study in Saudi Arabia supports previous reports that

suggest using abnormal liver enzymes as markers in patients with

CRC. The present study revealed that obese individuals had elevated

levels of GGT, which confirmed and complemented previous research

(37-39).

Additionally, the current study revealed that diabetic individuals

with CRC also had high levels of GGT, indicating its potential use

as an indicator marker for overweight or diabetic patients with

CRC.

The present study revealed a low familial prevalence

of CRC with only 0.62% (1 patient) of participants reporting a

family history. This may suggest a lower genetic predisposition in

our sample, or possibly underreporting. However, in line with the

majority of CRC cases being sporadic, 49.69% (80 patients) of the

study participants had no family history of the disease,

emphasizing the significance of lifestyle factors and acquired

genetic mutations in CRC development.

The management strategies for GGT involve several

aspects. Monitoring GGT levels can help assess liver function and

detect any liver damage or disease. Additionally, GGT levels can be

used as a biomarker to evaluate the effectiveness of treatment and

predict outcomes in patients with CRC with hepatic metastases

(40). In the clinical management

of CRC, patient-reported outcomes (PROs) play a crucial role.

Self-reported symptoms, including those related to liver function,

can guide the management of patients with CRC. Incorporating PROs

into clinical trials and routine practice helps assess treatment

efficacy and measure health-related quality of life (41).

It is important to note that GGT is not a direct

treatment target in CRC management. Instead, it serves as an

indicator of liver function and can provide valuable information

for healthcare providers in monitoring and managing patients with

CRC. The specific management strategies for GGT in CRC may vary

depending on individual patient characteristics and the overall

treatment plan. Therefore, it is essential for healthcare providers

to interpret GGT test results in conjunction with other clinical

information and tailor management strategies accordingly.

In summary, the current study highlighted the

critical role of obesity and diabetes as major risk factors for the

development of CRC in Saudi Arabia and potentially across the Arab

States of the Gulf region. It is important to recognize the

limitations of generalizing these findings to other populations.

Conducting additional research with larger and more diverse cohorts

would be valuable in confirming the observed associations and

examining potential variations across populations. These conditions

harm the colonic epithelium, leading to an increase in tumour

formation that can metastasize and result in cancer-related deaths

if left untreated. Additionally, we recommend further research to

investigate the mechanisms connecting obesity, diabetes and CRC

development, which would contribute to the existing knowledge in

the field. Moreover, the present research draws attention to the

growing incidence of CRC and proposes the need for preventive

measures to curb its rise. Our research provides valuable insights

into CRC prevalence, associated factors and the potential link

between CRC and liver function enzymes in Saudi Arabia. This

enhances our understanding of this significant health issue.

Supplementary Material

Level of LDH in circulation of

overweight (high BMI) patients.

Level of ALB in circulation of

overweight (high BMI) patients.

Level of ALT in circulation of

overweight (high BMI) patients.

Level of AST in circulation of

overweight (high BMI) patients.

Level of TBIL in circulation for

overweight (high BMI) patients.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Suliman Alghnam,

Chairman of Data Management, from King Abdullah International

Medical Research Center (Riyadh, Saudi Arabia) for facilitating

data collection. TCGA database and OncoLnc were utilized for data

analysis and description in this manuscript (23).

Funding

Funding: This research was funded by King Abdullah International

Medical Research Center (grant no. NRC22R/144/03).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

AMAlm, RHA, NFB and HHA collected data and organized

it. GA, JAA, AMAlj and BMA analysed data. GA validated the data.

BMA and GA supervised the project and wrote manuscript. BMA

obtained resources. GA and BMA confirm the authenticity of all the

raw data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The Institutional Review Board of The Ministry of

National Guard-Health Affairs approved this project (approval no.

NRC22R/144/03).

Patient consent for publication

This work involves searching and analysing a

hospital database, and the Institutional Review Board has waived

the requirement for patient consent since no patients' identifiable

information will be disclosed, and all data were coded and

delinked.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Rawla P, Sunkara T and Barsouk A:

Epidemiology of colorectal cancer: Incidence, mortality, survival,

and risk factors. Prz Gastroenterol. 14:89–103. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Registry SC: Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Saudi

Health council national health information center Saudi cancer

registry. Saudi Health Council https://shc.gov.sa/Arabic/NCC/Activities/AnnualReports/2018.pdf2018.

|

|

3

|

Aleanizy FS, Alqahtani FY, Alanazi MS,

Mohamed RAEH, Alrfaei BM, Alshehri MM, AlQahtani H, Shamlan G,

Al-Maflehi N, Alrasheed MM and Alrashed A: Clinical characteristics

and risk factors of patients with severe COVID-19 in Riyadh, Saudi

Arabia: A retrospective study. J Infect Public Health.

14:1133–1138. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Jasperson KW, Tuohy TM, Neklason DW and

Burt RW: Hereditary and familial colon cancer. Gastroenterology.

138:2044–2058. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Sawicki T, Ruszkowska M, Danielewicz A,

Niedźwiedzka E, Arłukowicz T and Przybyłowicz KE: A review of

colorectal cancer in terms of epidemiology, risk factors,

development, symptoms and diagnosis. Cancers (Basel).

13(2025)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Balwan WK and Kour S: Lifestyle diseases:

The link between modern lifestyle and threat to public health.

Saudi J Med Pharm Sci. 7:179–184. 2021.

|

|

7

|

Althumiri NA, Basyouni MH, AlMousa N,

AlJuwaysim MF, Almubark RA, BinDhim NF, Alkhamaali Z and Alqahtani

SA: Obesity in Saudi Arabia in 2020: Prevalence, distribution, and

its current association with various health conditions. Healthcare

(Basel). 11(311)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Cavagnari MAV, Silva TD, Pereira MAH,

Sauer LJ, Shigueoka D, Saad SS, Barão K, Ribeiro CCD and Forones

NM: Impact of genetic mutations and nutritional status on the

survival of patients with colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer.

19(644)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Capece D, D'Andrea D, Begalli F, Goracci

L, Tornatore L, Alexander JL, Di Veroli A, Leow SC, Vaiyapuri TS,

Ellis JK, et al: Enhanced triacylglycerol catabolism by

carboxylesterase 1 promotes aggressive colorectal carcinoma. J Clin

Invest. 131(e137845)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Liu T, Zhang Q, Wang Y, Ma X, Zhang Q,

Song M, Cao L and Shi H: Association between the TyG index and

TG/HDL-C ratio as insulin resistance markers and the risk of

colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer. 22(1007)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Màrmol JM, Carlsson M, Raun SH, Grand MK,

Sørensen J, Lehrskov LL, Richter EA, Norgaard O and Sylow L:

Insulin resistance in patients with cancer: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. Acta Oncol. 62:364–371. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Gosadi IM: Lifestyle counseling for

patients with type 2 diabetes in the Southwest of Saudi Arabia: An

example of healthcare delivery inequality between different

healthcare settings. J Multidiscip Healthc. 14:1977–1986.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Yu J, Feng Q, Kim JH and Zhu Y: Combined

Effect of healthy lifestyle factors and risks of colorectal

adenoma, colorectal cancer, and colorectal cancer mortality:

Systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Oncol.

12(827019)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Krämer HU, Schöttker B, Raum E and Brenner

H: Type 2 diabetes mellitus and colorectal cancer: Meta-analysis on

sex-specific differences. Eur J Cancer. 48:1269–1282.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Rui L: Energy metabolism in the liver.

Compr Physiol. 4:177–197. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Casas-Grajales S and Muriel P:

Antioxidants in liver health. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther.

6:59–72. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Jiang H, Dong L, Gong F, Gu Y, Zhang H,

Fan D and Sun Z: Inflammatory genes are novel prognostic biomarkers

for colorectal cancer. Int J Mol Med. 42:368–380. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Alrfaei BM, Almutairi AO, Aljohani AA,

Alammar H, Asiri A, Bokhari Y, Aljaser FS, Abudawood M and Halwani

M: Electrolytes play a role in detecting cisplatin-induced kidney

complications and may even prevent them-retrospective analysis.

Medicina (Kaunas). 59(890)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

He MM, Fang Z, Hang D, Wang F,

Polychronidis G, Wang L, Lo CH, Wang K, Zhong R, Knudsen MD, et al:

Circulating liver function markers and colorectal cancer risk: A

prospective cohort study in the UK Biobank. Int J Cancer.

148:1867–1878. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Khoei NS, Jenab M, Murphy N, Banbury BL,

Carreras-Torres R, Viallon V, Kühn T, Bueno-de-Mesquita B,

Aleksandrova K, Cross AJ, et al: Circulating bilirubin levels and

risk of colorectal cancer: Serological and Mendelian randomization

analyses. BMC Med. 18(229)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Lv L, Sun X, Liu B, Song J, Wu DJH, Gao Y,

Li A, Hu X, Mao Y and Ye D: Genetically predicted serum albumin and

risk of colorectal cancer: A bidirectional mendelian randomization

study. Clin Epidemiol. 14:771–778. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Alqahtani FY, Aleanizy FS, Mohamed RAEH,

l-Maflehi N, Alrfaei BM, Almangour TA, Alkhudair N, Bawazeer G,

Shamlan G and Alanazi MS: Association between obesity and COVID-19

disease severity in Saudi Population. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes.

15:1527–1535. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Anaya J: OncoLnc: linking TCGA survival

data to mRNAs, miRNAs, and lncRNAs. PeerJ Computer Science.

2(e67)2016.

|

|

24

|

González N, Prieto I, Del Puerto-Nevado L,

Portal-Nuñez S, Ardura JA, Corton M, Fernández-Fernández B,

Aguilera O, Gomez-Guerrero C, Mas S, et al: 2017 update on the

relationship between diabetes and colorectal cancer: Epidemiology,

potential molecular mechanisms and therapeutic implications.

Oncotarget. 8:18456–18485. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

International Agency for Research on

Cancer: Globocan 2018: Cancer Fact Sheets-Colorectal Cancer.

https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/cancers/10_8_9-Colorectum-fact-sheet.pdf.

Accessed, March 20, 2023.

|

|

26

|

Bardou M, Barkun AN and Martel M: Obesity

and colorectal cancer. Gut. 62:933–947. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Chaplin A, Rodriguez RM, Segura-Sampedro

JJ, Ochogavía-Seguí A, Romaguera D and Barceló-Coblijn G: Insights

behind the relationship between colorectal cancer and obesity: Is

visceral adipose tissue the missing link? Int J Mol Sci.

23(13128)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Stern JH, Rutkowski JM and Scherer PE:

Adiponectin, leptin, and fatty acids in the maintenance of

metabolic homeostasis through adipose tissue crosstalk. Cell Metab.

23:770–784. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Zieba D, Biernat W and Barć J: Roles of

leptin and resistin in metabolism, reproduction, and leptin

resistance. Domest Anim Endocrinol. 73(106472)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Bullon-Vela V, Abete I, Tur JA, Konieczna

J, Romaguera D, Pintó X, Corbella E, Martínez-González MA,

Sayón-Orea C, Toledo E, et al: Relationship of visceral adipose

tissue with surrogate insulin resistance and liver markers in

individuals with metabolic syndrome chronic complications. Ther Adv

Endocrinol Metab. 11(2042018820958298)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Zatterale F, Longo M, Naderi J, Raciti GA,

Desiderio A, Miele C and Beguinot F: Chronic adipose tissue

inflammation linking obesity to insulin resistance and type 2

diabetes. Front Physiol. 10(1607)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Lee JY, Lee HS, Lee DC, Chu SH, Jeon JY,

Kim NK and Lee JW: Visceral fat accumulation is associated with

colorectal cancer in postmenopausal women. PLoS One.

9(e110587)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Lauria MW, Moreira LM, Machado-Coelho GL,

Neto RM, Soares MM and Ramos AV: Ability of body mass index to

predict abnormal waist circumference: Receiving operating

characteristics analysis. Diabetol Metab Syndr.

5(74)2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Giovannucci E, Harlan DM, Archer MC,

Bergenstal RM, Gapstur SM, Habel LA, Pollak M, Regensteiner JG and

Yee D: Diabetes and cancer: A consensus report. Diabetes Care.

33:1674–1685. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Wondmkun YT: Obesity, insulin resistance,

and type 2 diabetes: Associations and therapeutic implications.

Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 13:3611–3616. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Kasprzak A: Insulin-like growth factor 1

(IGF-1) signaling in glucose metabolism in colorectal cancer. Int J

Mol Sci. 22(6434)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Liu C, Shao M, Lu L, Zhao C, Qiu L and Liu

Z: Obesity, insulin resistance and their interaction on liver

enzymes. PLoS one. 16(e0249299)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Verrijken A, Francque S, Mertens I,

Talloen M, Peiffer F and Van Gaal L: Visceral adipose tissue and

inflammation correlate with elevated liver tests in a cohort of

overweight and obese patients. Int J Obes. 34:899–907.

2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Ali N, Sumon AH, Fariha KA, Asaduzzaman M,

Kathak RR, Molla NH, Mou AD, Barman Z, Hasan M, Miah R and Islam F:

Assessment of the relationship of serum liver enzymes activity with

general and abdominal obesity in an urban Bangladeshi population.

Sci Rep. 11(6640)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Brennan PN, Dillon JF and Tapper EB:

Gamma-Glutamyl transferase (γ-GT)-an old dog with new tricks? Liver

Int. 42:9–15. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Xiao B, Peng J, Tang J, Deng Y, Zhao Y, Wu

X, Ding P, Lin J and Pan Z: Serum Gamma Glutamyl transferase is a

predictor of recurrence after R0 hepatectomy for patients with

colorectal cancer liver metastases. Ther Adv Med Oncol.

12(1758835920947971)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|