Introduction

Geriatric syndromes such as cognitive decline, bone

fragility, and mood disturbances often co-occur in older adults and

may share overlapping pathophysiological pathways (1-5).

For example, dementia, as typified by Alzheimer's disease (AD), and

bone fragility are common among the elderly, and the causal

relationship in their development has started to attract attention

(1-3,5).

In addition, cognitive impairment and bone fragility in the elderly

have been linked to mental health conditions such as apathy and

depression (2,6). Because these conditions are

associated with severe morbidity, long-term disability, mortality,

and significant socioeconomic impact, there is an urgent global

need to develop effective strategies to address them.

Despite extensive research over the past 30 years,

the development of fundamental treatments for geriatric diseases

remains elusive. Consequently, interest is growing in comprehensive

approaches to prevent geriatric diseases and extend healthy life

expectancy through lifestyle modification, including daily diet

(7,8). A variety of foods containing certain

naturally occurring ingredients have the potential to prevent

several diseases (9-11).

For the past decade, we have been investigating functional foods

that can be easily incorporated into the daily diet and may help

prevent or manage various geriatric diseases (12-15).

In this study, we focused on the functional properties of rice, a

staple food for more than half of the global population. Generally,

the rice consumed daily is white rice (WR) milled from brown rice

(BR). The bran layer on BR is rich in various nutrients, including

minerals, vitamins, and dietary fibers, and contains many

substances that are considered effective against geriatric

diseases, including γ-oryzanol, γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), and

ferulic acid (16-19).

However, from a consumer perspective, regular BR has many

drawbacks, such as a distinctive flavor and taste, hard texture,

and low water absorbency, which makes it difficult to cook and hard

to digest.

An ultrahigh hydrostatic pressure apparatus capable

of applying water pressure of up to 6,000 atm (600 MPa) was

recently developed (20,21). The ultra-high hydrostatic

pressurized brown rice (UBR) obtained by processing with this

equipment overcomes various drawbacks of BR. Compared with regular

BR, UBR has improved water absorption, making it easier to cook, a

less distinctive flavor, better texture, and is more easily

digested (20,21). In addition, the ultrahigh

hydrostatic pressure process confers an advantage in rice

preservation by reducing the number of bacteria in the BR (20,21).

We previously conducted a 24-month intervention trial of UBR intake

in elderly participants, which was associated with the preservation

or maintenance of cognitive function (22). A 12-month intake of UBR was

associated with the maintenance of bone health in the elderly

(23). Although previous findings

have suggested that UBR may contribute to maintaining cognitive

function and bone density, the interrelationship among these

domains and the effects of UBR on mental health remain unclear.

Therefore, we conducted a 12-month, randomized controlled trial to

evaluate the effects of UBR intake on cognitive function, apathy,

and bone health in older adults and to explore possible

correlations among these outcomes.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

This study was a 12-month, randomized controlled

trial conducted in community-dwelling older adults aged 65-85

years. The intervention was carried out between October 2015 and

March 2017 in Iinan Town, Shimane Prefecture, Japan. Although the

study was conducted prior to trial registration, it was

retrospectively registered in the UMIN Clinical Trials Registry

(registration no. UMIN000053587, date: February 9th, 2024) before

submission. The delay in registration occurred due to a lack of

awareness of prospective trial registration requirements at the

time of study initiation. We acknowledge this as a limitation and

affirm that all future clinical trials will be prospectively

registered in accordance with international standards. The study

was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Shimane University

School of Medicine (approval no. 1940-2504). The study adhered to

the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Prior to study participation, all volunteers provided written

informed consent. In this study, 54 healthy volunteers

participated, and underwent physical examinations including

anthropometry, medical interview by a physician and blood

biochemical tests. Volunteers completed a lifestyle questionnaire

covering medical and medication history. The following volunteers

were excluded from the study: volunteers with any medical

disorders, including cardiac, hepatic, renal, gastrointestinal,

respiratory disease, diabetes mellitus, neurological disorders, and

osteoporosis, metabolic, cancer, endocrine, or hematological

disorders; those eating BR daily; those consuming

medications/supplements to treat bone disorders or osteoporosis

and/or improve cognitive and mental function that could affect the

results of the study; those with allergies and hypersensitivity;

smokers. Of the 54 volunteers screened for eligibility, 44

participants (mean age, 73.1±5.6 years) were enrolled into the

study and assigned to either the WR-intake group (n=22) or the UBR

intake group (n=22) (Fig. 1).

Participants were diagnosed by a clinician to ensure they had no

neuropsychiatric or other disorders. No volunteers had participated

in any other clinical studies within the past year. Group

allocation was conducted by stratified random assignment, as

described previously (24,25). The randomization code lists were

prepared by an independent clinical research advisor and concealed

from the investigators, participants, outcome assessors, and data

analysts. All assessments and data analyses were performed in a

blinded manner, and group assignments were disclosed only after

completion of the study. Although participants were not informed

which intervention (UBR or WR) was considered active, the

noticeable differences in color, texture, and flavor between the

two made complete blinding of participants infeasible. Participants

in the WR-intake group received 200 g of WR daily for 12 months;

those in the UBR-intake group received 100 g of UBR and 100 g of WR

daily for 12 months. The rice intake was voluntary for the

participants. During the intervention period, participants were

advised to avoid other BR products and functional foods potentially

influencing cognitive or bone health. This request was made to

reduce confounding factors, and adherence was encouraged without

disrupting participants' usual lifestyle. Participants' adherence

to rice consumption was daily investigated using a

self-administered questionnaire.

Test foods

Both UBR and WR were supplied by NPO Satoyama

Commission (Iinan-cho). To prepare UBR, BR was exposed to water at

a hydrostatic pressure of 600 MPa for 5 s using a hydrostatic

pressurizer (21). UBR and WR were

both cultivated in Iinan-cho, Shimane, Japan, and produced from the

same variety of rice. The nutrient content of WR and UBR was

measured at Shimane Environment & Health Public Corporation and

Shimane Institute for Industrial Technology and is summarized in

Table I. Compared with WR, UBR was

richer in lipids and dietary fiber and has a higher content of

minerals, including magnesium (Mg), calcium (Ca), inorganic

phosphorus (Pi), and iron (Fe). In addition, UBR is rich in

vitamins B1, B6, and niacin, as well as

bioactive substances such as GABA, inositol, and ferulic acid

(Table I).

| Table INutrients content of WR and UBR. |

Table I

Nutrients content of WR and UBR.

| Nutrients | WR | UBR |

|---|

| Protein, g | 6.80 | 7.70 |

| Carbohydrate,

g | 75.30 | 76.60 |

| Dietary fiber,

g | 0.30 | 7.10 |

| Lipid, g | 1.30 | 3.00 |

| GABA, mg | 2.00 | 9.10 |

| Inositol, mg | ND | 202.00 |

| Ferulic acids,

mg | ND | 12-50 |

| Calcium, mg | 2.00 | 9.00 |

| Magnesium, mg | 20.00 | 110.00 |

| Phosphate, mg | 140.00 | 290.00 |

| Potassium, mg | 110.00 | 230.00 |

| Sodium, mg | 2.00 | 1.89 |

| Iron, mg | 0.50 | 2.10 |

| Zinc, mg | 4.00 | 1.80 |

| Vitamin B1, mg | 0.12 | 0.51 |

| Vitamin B2, mg | 0.03 | 0.04 |

| Vitamin B6, mg | 0.05 | 0.32 |

| Vitamin E, mg | 0.40 | ND |

| Niacin, mg | 1.40 | 7.46 |

Anthropometry

Height, waist circumference, and blood pressure were

measured by trained nurses. Body weight and body fat were measured

using a bioelectrical impedance analyzer (WB-150; TANITA Co.), as

described previously (26). After

these measurements, participants completed two self-administered

questionnaires: a general lifestyle questionnaire, which included

items on educational background and medical/medication history, and

a brief diet history questionnaire, as described previously

(22,26).

Blood biochemistry

At baseline and after 12 months of the intervention,

blood samples were drawn by nurses in the morning after confirming

whether participants had fasted. Serum was separated from whole

blood samples and stored at -80˚C until use. Serum biochemical

parameters were measured using an automated clinical chemistry

analyzer TBA-c16000 (TOSHIBA); serum HbA1c level was determined

with high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) using an

HLC-723G9 (TOSOH); and blood sugar was measured using the GA08III

automatic analyzer (A&T Co.), as described previously (7).

Safety assessment

Adverse events were monitored throughout the

12-month study period using structured monthly interviews and

questionnaires. Participants were asked about specific symptoms

including gastrointestinal issues (e.g., bloating, flatulence,

diarrhea), allergic reactions, appetite changes, and bowel habit

alterations. Any reported events were recorded and evaluated by the

study physician to determine their relationship to the

intervention.

Serum monoamine levels

The concentrations of monoamines, i.e., epinephrine

(Epi), norepinephrine (NE), dopamine (DA), and serotonin (5-HT), in

the serum were measured using a previously described HPLC method

(22). Briefly, the serum was

pretreated with a clean EG column (EICOM). The HPLC equipment

consisted of an EICOM HTEC-500 (EICOM) equipped with a data

processor (EICOM EPC-500 PowerChrom) and an automatic injector

(EICOM M-514). Chromatographic separation was performed using an

EICOMPAK CA-5ODS column (2.1x150 mm ID) linked to a precolumn

(EICOM PREPAK PC-03-CA). PowerChrom software was used for data

collection and analysis (EICOM). The mobile phase consisted of 0.1

M phosphate buffer (pH 5.7) containing 700 mg/l sodium

1-octanesulfonate, 12% methanol, and 50 mg/l EDTA disodium salt.

The flow rate was set to 0.23 ml/min, and the applied potential was

+450 mV with respect to an Ag/AgCl reference electrode. The column

temperature was maintained at 25˚C.

Cognitive function and mental health

assessment

Cognitive function was assessed using the

Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (27), the Revised Hasegawa's Dementia

Scale (HDS-R) (28), the Frontal

Assessment Battery (FAB) (29),

and the Cognitive Assessment for Dementia, iPad version (CADi)

(30). The MMSE is a cognitive

function test consisting of 11 subitems. MMSE can be used to screen

cognitive impairment, estimate the severity of cognitive impairment

at a given point in time, track an individual's cognitive changes

over time, and document an individual's response to treatment

(27). A total MMSE score of 24 to

27 points is considered indicative of mild cognitive impairment

(MCI), while a score below 23 suggests possible dementia (27). The HDS-R is commonly used for

dementia screening in Japan and includes 9 items assessing

orientation, memory, attention, and verbal fluency (28). Generally, a score below 20 is

considered suggestive of dementia (28). The FAB, consisting of 6 subtests,

is a cognitive test that incorporates several clinical assessments

to screen for frontotemporal dementia, including S-word generation,

similarities, Luria's test, grasp reflex, and the Go-No-Go test

(29). The CADi consists of 10

items and is a useful tool for population screening for dementia

and is known to correlate significantly with MMSE scores (30). In CADi, the time spent performing a

task is also evaluated and used as an indicator of cognitive

processing ability (30).

Furthermore, mental condition, i.e., apathy and depression, was

assessed using the Japanese version of the Starkstein apathy scale

(31) and the Zung Self-Rating

Depression Scale (SDS) (32),

respectively. The Starkstein apathy scale is a subjective rating

scale with scores ranging from 0 to 42; higher scores indicate less

motivation and a greater apathy severity (31). The cutoff for the apathy scale is

16 points, and apathy is suspected in those who score 16 points or

higher. The SDS is also a self-rating scale, comprising responses

to 20 questions on a 4-point scale; a higher total score indicates

a tendency toward depression (32). These tests are commonly used in

clinical and interventional studies as they are relatively quick

and can easily assess an individual's cognitive and mental function

(12-15,22,25,26).

All assessments were conducted by trained clinicians.

Quantitative ultrasound measurements

of the calcaneum

To assess bone status, we used an ultrasonic bone

densitometer (Venus-α; Nihon Kohden, Tokyo, Japan) to perform

quantitative ultrasound (QUS) of the right calcaneus, as previously

described (23). The device uses a

combination of ultrasound pulse reflection and ultrasound pulse

transmission methods to measure the speed of sound (SOS) and the

bone width of the calcaneus and subsequently calculates the bone

area ratio (BAR). QUS offers a quick and noninvasive method for

evaluating bone health without the radiation exposure associated

with dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA). The BAR values

obtained with this device have been reported to correlate

significantly with bone mineral density (BMD) measurements by DXA

at the lumbar spine (r=0.77, P<0.01) and calcaneus (r=0.83,

P<0.01) (33). For each

participant, the BAR of the right calcaneus was measured at least

three times and converted to the percentage of the young adult mean

(%YAM), using reference data from Japanese adults aged 20-44, in

which 100% represents the average bone density for that age group.

%YAM is widely used in clinical practice in Japan as an index of

bone status and allows for standardized comparisons across

individuals (34,35).

Sample size power calculation

The sample size was calculated using PS: Power &

Sample Size Calculation Software Version 3.1.2 (Vanderbilt

University, Nashville, TN, USA). The primary outcomes were the

change in MMSE scores after 12 months of intervention. Based on

data from a previous randomized controlled trial involving a

similar population (15,22), a mean difference of 1.4 points

(SD=2.0) between groups was expected. Assuming two-sided α=0.05 and

90% power, a minimum of 20 participants per group was required

using an independent t-test. To account for an anticipated dropout

rate of 10%, we enrolled 22 participants per group.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM

SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 26.0 (IBM Corp.). A

per-protocol approach was adopted for efficacy analyses. Data were

first assessed for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test. All

variables met normality assumptions and are presented as mean ±

standard error of the mean (SEM). The primary outcomes were the

MMSE score and Starkstein apathy scale score at 12 months.

Secondary outcomes included other cognitive measures (CADi, HDS-R,

FAB), additional mental health indicators (SDS), and bone health

index (%YAM). To assess between-group differences at 12 months

while controlling for potential baseline imbalances, analysis of

covariance (ANCOVA) was employed. In the ANCOVA models, the

12-month score was entered as the dependent variable, group (UBR

vs. WR) as the fixed factor, and baseline score and age as

covariates. To examine time-by-group interaction effects across

baseline and 12 months, two-way repeated measures ANOVA were used.

When a significant interaction was found, post hoc comparisons were

performed using Tukey's test. Between-group comparisons of change

scores (Δ=12 months-baseline) were conducted using independent

samples t-tests as supplementary analyses. While change scores are

reported for descriptive purposes, interpretation of primary

effects was based on ANCOVA results. Effect sizes for between-group

comparisons were calculated using Cohen's d, with thresholds of

0.2, 0.5, and 0.8 representing small, medium, and large effects,

respectively. Partial correlation analyses were conducted to

explore the associations among cognitive, mental, and bone-related

outcomes at 12 months, adjusting for age and baseline scores. All

tests were two-tailed, and statistical significance was set at

P<0.05.

Results

Adherence

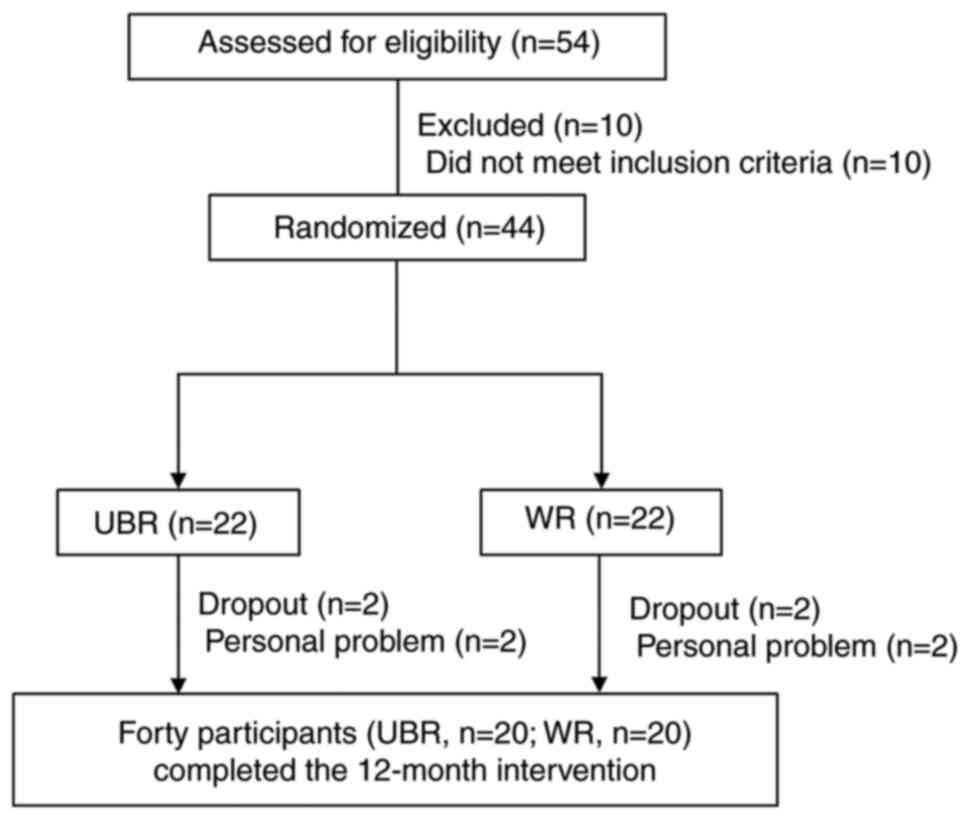

Fig. 1 shows a flow

diagram of this intervention study. During the 12-month

intervention, four subjects (two in the WR-intake group and two in

the UBR-intake group) retired for personal reasons (Fig. 1). Therefore, the 12-month

intervention trial was completed by twenty participants both in the

WR-intake group and UBR-intake group (Fig. 1). Participants demonstrated

excellent adherence to the intervention protocol for 12 months

(UBR: 95.5%, WR: 96.8%). Data from general questionnaires on

lifestyle habits and medical/medication history showed no

significant differences during 12 months of intervention (data not

shown). Adverse effects disturbing participants' daily lives such

as palpitation, anorexia, diarrhea, constipation, allergic

reactions, and irritated stomach were not observed in both groups.

The BDHQ survey showed no significant difference in mean dietary

nutrient intake between the UBR-intake and WR-intake groups at 12

months (data not shown).

Body composition, blood pressure,

blood biochemistry, and serum monoamine levels

Table II shows the

values for body composition, blood pressure, blood biochemistry,

and serum monoamine levels of the participants at baseline and at

12 months after the intervention, as well as the changes during the

intervention period. At baseline, there were no significant

differences between the WR-intake and UBR intake groups in body

weight, height, fat mass, BMI, waist circumference, or blood

pressure (Table II). Similarly,

no significant differences were observed between the groups for

blood biochemical variables, aspartate transaminase (AST), alanine

transaminase (ALT), γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (γ-GTP), albumin

(ALB), total cholesterol (T-cho), triglyceride (TG), blood urea

nitrogen (BUN), creatinine (CRE), LDL-cholesterol (LDL-C),

HDL-cholesterol (HDL-C), blood sugar, or HbA1c levels at baseline

(Table II). After 12 months of

the intervention, the two groups did not differ in height, body

weight, body fat mass, BMI, waist circumference, or blood pressure

(Table II), and there were no

significant differences in blood biochemistry parameters, blood

sugar, or HbA1c. Furthermore, for each parameter, the change from

baseline to 12 months was not significantly different (Table II). Serum EPi, NE, DA, and 5-HT

levels did not differ between the groups at baseline, and long-term

UBR intake had no effect. From baseline to 12 months, D5-HT levels

were slightly increased in the UBR intake group, but the change was

not statistically significant (P=0.081, Table II).

| Table IIParticipants' characteristics and

anthropometric biochemical variables. |

Table II

Participants' characteristics and

anthropometric biochemical variables.

| | Baseline | Month 12 | Change amount

(Δ) | |

|---|

| Characteristic | WR | UBR | WR | UBR | WR | UBR | P-value |

|---|

| N | 22 | 22 | 20 | 20 | - | - | - |

| Sex

(male/female) | 10/12 | 10/12 | 8/12 | 10/10 | - | - | 0.532 |

| Age | 75.2±1.3 | 70.8±1.2 | 75.7±1.4 | 72.4±1.3 | - | - | 0.038 |

| Anthropometry | | | | | | | |

|

Height,

cm | 153.3±1.7 | 157.5±2.5 | 153.8±1.7 | 159.1±2.6 | 0.6±0.5 | 0.7±0.6 | 0.779 |

|

Body weight,

kg | 53.7±1.9 | 60.7±3.2 | 53.8±1.9 | 60.3±3.5 | 0.1±0.3 | -0.4±0.5 | 0.094 |

|

BMI,

kg/m2 | 22.8±0.6 | 23.9±0.7 | 22.6±0.5 | 23.8±0.7 | 1.7±3.9 | 4.7±4.6 | 0.924 |

|

Body fat,

% | 28.4±1.7 | 28.9±2.1 | 29.4±1.3 | 28.8±1.2 | 1.0±0.3 | 0.1±0.4 | 0.621 |

|

WC, cm | 86.1±1.7 | 87.1±2.1 | 83.8±1.9 | 86.3±2.4 | -2.4±0.9 | -0.8±0.6 | 0.421 |

| Blood pressure | | | | | | | |

|

SBP,

mmHg | 143.6±6.6 | 141.6±3.0 | 144.9±5.9 | 147.4±4.0 | 0.8±2.2 | 2.9±2.1 | 0.864 |

|

DPB,

mmHg | 76.4±3.6 | 78.7±2.1 | 78.6±3.2 | 82.2±2.3 | 1.1±0.2 | 2.0±0.2 | 0.119 |

| Biochemistry | | | | | | | |

|

AST,

IU/l | 24.9±1.4 | 27.2±0.9 | 26.4±1.7 | 27.9±1.5 | 1.5±1.4 | 0.7±1.0 | 0.779 |

|

ALT,

IU/l | 16.1±1.9 | 20.8±1.9 | 18.7±2.1 | 21.3±1.5 | 1.6±1.6 | 0.4±1.3 | 0.383 |

|

γ-GTP,

IU/l | 31.9±8.6 | 41.9±10.4 | 32.8±9.3 | 45.1±11.9 | 0.8±1.6 | 2.5±2.9 | 0.461 |

|

ALB,

g/dl | 4.1±0.1 | 4.1±0.1 | 4.2±0.1 | 4.2±0.1 | 0.1±0.1 | 0.1±0.0 | 0.620 |

|

T-cho,

mg/dl | 192.2±5.3 | 191.6±6.0 | 196.6±6.6 | 197.5±5.4 | 4.3±6.0 | 5.9±2.8 | 0.998 |

|

TG,

mg/dl | 125.3±8.6 | 121.3±14.2 | 129.1±10.5 | 144.1±19.8 | 4.5±11.0 | 23.6±15.2 | 0.758 |

|

BUN,

mg/dl | 17.0±1.0 | 15.4±0.5 | 15.6±1.1 | 15.0±0.6 | -1.3±0.8 | -0.3±0.6 | 0.289 |

|

BS,

mg/dl | 113.9±6.3 | 100.9±6.2 | 118.6±7.0 | 109.1±4.9 | 4.9±8.7 | 8.1±4.3 | 0.968 |

|

CRE,

mg/dl | 0.7±0.0 | 0.7±0.0 | 0.7±0.0 | 0.7±0.0 | 0.0±0.0 | 0.0±0.0 | 0.814 |

|

HDL-C,

mg/dl | 65.1±2.0 | 62.8±2.3 | 66.2±3.9 | 64.2±2.8 | 1.8±1.9 | 1.9±1.5 | 0.779 |

|

LDL-C,

mg/dl | 102.1±5.4 | 106.2±6.1 | 104.7±5.3 | 104.5±6.5 | 1.7±7.0 | -0.7±3.2 | 0.947 |

|

HbA1c,

% | 5.8±0.1 | 5.9±0.1 | 5.9±0.1 | 6.0±0.1 | 0.2±0.4 | 0.1±0.1 | 0.121 |

| Serum

monoamines | | | | | | | |

|

Epi,

ng/ml | 6.7±6.0 | 1.8±1.0 | 7.7±2.7 | 4.9±1.2 | 1.0±5.7 | 3.2±1.0 | 0.353 |

|

NE,

ng/ml | 45.9±6.9 | 55.5±4.2 | 102.8±6.8 | 112.6±5.4 | 67.0±10.3 | 56.9±4.9 | 0.752 |

|

DA,

ng/ml | 3.1±1.5 | 6.0±3.1 | 2.6±1.7 | 4.9±1.1 | 2.6±1.7 | 0.5±0.3 | 0.208 |

|

5-HT,

ng/ml | 10,470±986 | 11,313±1184 | 12,416±1274 | 14,448±810 | 1,690±631 | 3,305±650 | 0.087 |

Safety assessment

Adverse events were monitored monthly using

structured interviews. Participants were asked about common

symptoms potentially associated with dietary fiber intake, such as

bloating, diarrhea, and allergic reactions. No participants

reported any adverse symptoms during the 12-month study period.

These findings, together with the absence of unfavorable changes in

clinical parameters (e.g., liver enzymes, kidney function, blood

pressure), support the safety of long-term UBR intake.

Cognitive and mental health

assessments

MMSE, CADi, HSD-R, and FAB were used to assess

participants' cognitive function, and the results were summarized

in Table III. In this study, all

participants had MMSE scores of 24 or higher, Apathy scores of 16

or lower, and SDS scores of 40 or lower during the intervention

period, suggesting that they were not suffering from dementia,

apathy, or depression. At baseline, there were no significant

differences between the groups for all measures of cognitive

outcomes (Table III). At 12

months, MMSE and CADi total scores in the UBR-intake group were

higher than in the WR-intake group. A two-way ANOVA revealed a

significant group x time interaction for MMSE total scores,

F(1,78)=7.67, P=0.021. Although the mean change in MMSE from

baseline to 12 months was not statistically significant between the

groups (P=0.142), ANCOVA adjusting for baseline value and age

revealed that the 12-month MMSE score was significantly higher in

the UBR group than in the WR group [F(1,36)=4.21, P=0.046, Cohen's d=0.72].

Sensitivity analyses using a simple comparison without covariates

(P=0.034) and an alternative ANCOVA adjusting for age and sex

(P=0.040) confirmed these results (Table SI). The absolute difference of 1.4

points, while statistically significant, was below the commonly

cited in Minimal Clinically Important Difference (MCID) of 2-3

points, suggesting cognitive preservation rather than true

improvement. Subitem analysis of the MMSE revealed no significant

between-group difference in the change in ‘Recall 3 words’, a

measure of recent memory (P=0.098, Table III). Regarding CADi, significant

group x time interactions were observed for total score

[F(1,78)=5.59, P=0.048] and execution time [F(1,78)=16.46,

P=0.014]. At 12 months, CADi total score increased (P=0.038) and

execution time decreased (P=0.008) in the UBR group compared to WR

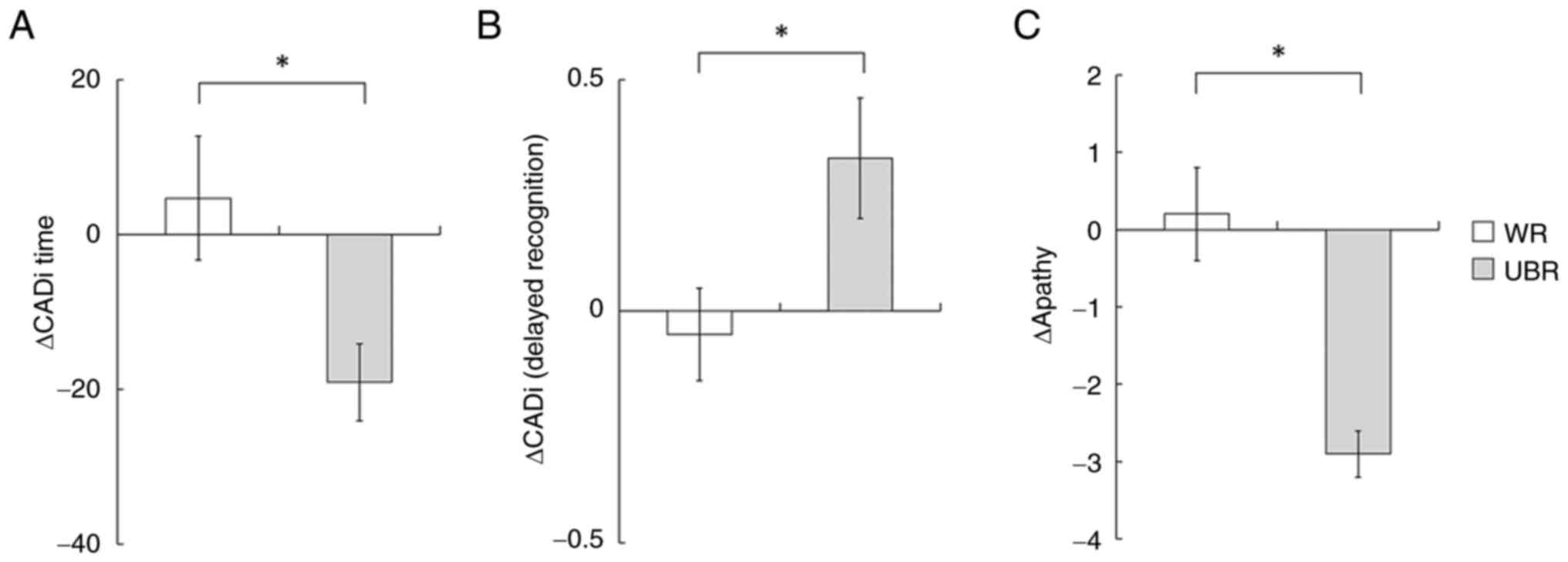

(Table III). The change in

execution time (ΔCADi time) was significantly greater in the UBR

group (Fig. 2A, P=0.026), and

subitem analysis revealed a significant difference in ‘Delayed

Recognition’ (Fig. 2B, P=0.027).

For apathy, ANCOVA adjusting for baseline score and age showed a

significantly lower 12-month score in the UBR group [F(1,36)=7.92, P=0.008; Cohen's d=0.89]. A

two-way ANOVA also revealed a significant group x time interaction

[F(1,78)=11.13, P=0.007], and Δapathy scores were significantly

lower in the UBR group compared to the control (Fig. 2C, P=0.015), suggesting a potential

benefit of UBR intake on motivational state. SDS values showed a

non-significant trend toward reduction in the UBR group at 12

months (P=0.142), and between-group differences in change scores

were not significant (P=0.294). HDS-R and FAB scores showed no

significant differences. Sensitivity analyses for apathy and CADi

confirmed consistent results across models (P=0.010-0.012 for

apathy; P<0.05 for CADi), with moderate to large effect sizes

(apathy: d=0.89; CADi: d=0.75-1.02). For HDS-R, FAB, and SDS,

exploratory sensitivity analyses revealed small to moderate effect

sizes (e.g., HDS-R: d=0.38) despite non-significant P-values

(Table SII).

| Table IIICognitive and mental health

assessments. |

Table III

Cognitive and mental health

assessments.

| | Baseline | Month 12 | Change amount

(Δ) | |

|---|

| Assessment | WR | UBR | WR | UBR | WR | UBR | P-value |

|---|

| MMSE | 28.2±0.2 | 28.5±0.1 | 27.4±0.2 |

28.7±0.2a | -0.6±0.4 | 0.2±0.3 | 0.142 |

| ‘Recall 3

Words’ | 2.5±0.1 | 2.4±0.2 | 2.4±0.1 | 2.6±0.1 | -0.1±0.1 | 0.2±0.1 | 0.098 |

| CADi total | 7.6±0.3 | 8.0±0.3 | 7.9±0.3 |

8.8±0.2a | 0.3±0.3 | 0.6±0.2 | 0.439 |

| ‘Delayed

Recognition’ | 0.63±0.1 | 0.61±0.1 | 0.60±0.1 | 0.91±0.1 | -0.05±0.2 | 0.31±0.2 | 0.024 |

| CADi time | 141.0±8.2 | 127.6±10.3 | 151.7±11.2 |

108.6±6.7b | 4.7±8.0 | -19.1±5.0 | 0.026 |

| ‘Delayed

Recognition’ | 18.6±2.3 | 16.7±1.3 | 18.3±2.3 |

12.2±1.2a | 0.0±1.2 | -4.0±1.2 | 0.016 |

| FAB | 14.7±0.3 | 15.2±0.5 | 15.1±0.4 | 15.6±0.4 | 0.5±0.3 | 0.4±0.3 | 0.775 |

| HDS-R | 27.7±0.5 | 28.9±0.2 | 27.5±0.5 | 28.9±0.4 | -0.2±0.4 | 0.0±0.1 | 0.581 |

| Apathy | 11.1±1.0 | 9.8±1.2 | 11.3±1.2 |

6.6±1.0b,c | 0.2±0.6 | -2.9±0.3 | 0.015 |

| SDS | 33.6±1.5 | 32.8±1.6 | 32.5±1.4 | 29.0±1.6 | -1.0±1.3 | -3.6±1.1 | 0.294 |

Assessment of bone status using

quantitative ultrasound

Table IV presents

the values of SOS and %YAM at baseline and after the 12-month

intervention, along with the corresponding changes over time. At

baseline, no significant differences were observed between the UBR

and WR groups in SOS or %YAM. After 12 months, both SOS and %YAM

values were higher in the UBR group compared to the WR group. A

two-way ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of group for both

SOS [F(1,78)=4.22, P=0.046] and %YAM [F(1,78)=4.64, P=0.043],

indicating that participants in the UBR group maintained

significantly greater bone status than those in the WR group. No

significant group x time interaction effects were found for either

SOS or %YAM (P>0.05). Post hoc comparisons showed that the %YAM

at 12 months was significantly higher in the UBR group compared to

the WR group (P=0.032). Similarly, SOS was significantly greater in

the UBR group at 12 months (P<0.05). No significant difference

in calcaneal bone width was detected between groups (data not

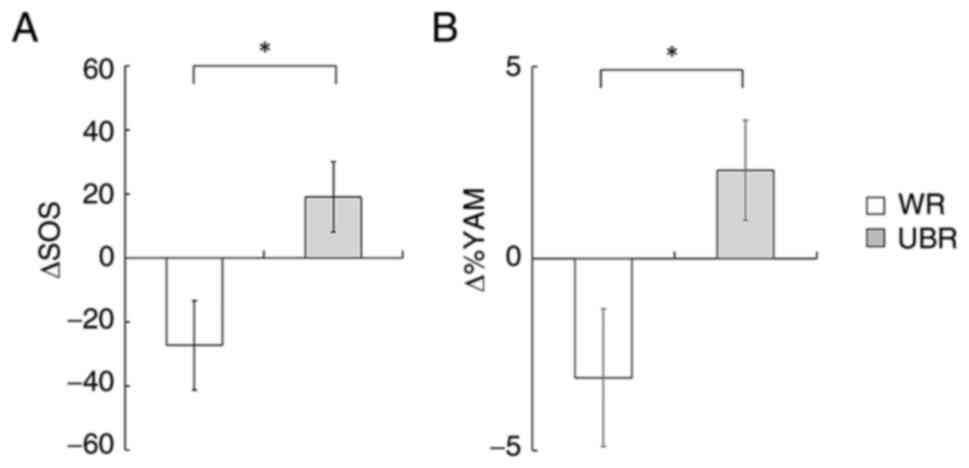

shown). Fig. 3 illustrates the

changes in SOS (ΔSOS) and %YAM (Δ%YAM) from baseline to 12 months.

Both ΔSOS (P=0.035) and Δ%YAM (P=0.034) were significantly greater

in the UBR group compared to the WR group, further supporting a

potential benefit of UBR intake on bone health in older adults.

| Table IVBone health assessment using

quantitative ultrasound measurements. |

Table IV

Bone health assessment using

quantitative ultrasound measurements.

| | Baseline | Month 12 | Change amount

(Δ) | |

|---|

| Measurement | WR | UBR | WR | UBR | WR | UBR | P-value |

|---|

| SOS, m/sec | 1,799.5±14.3 | 1,830.8±20.5 | 1,774.5±16.7 |

1,855.1±22.9a | -27.3±14.1 | 19.7±11.6 | 0.035 |

| %YAM | 85.6±2.4 | 88.6±2.4 | 82.4±2.0 |

91.5±2.7a | -3.1±1.8 | 2.3±1.3 | 0.034 |

Correlation analysis

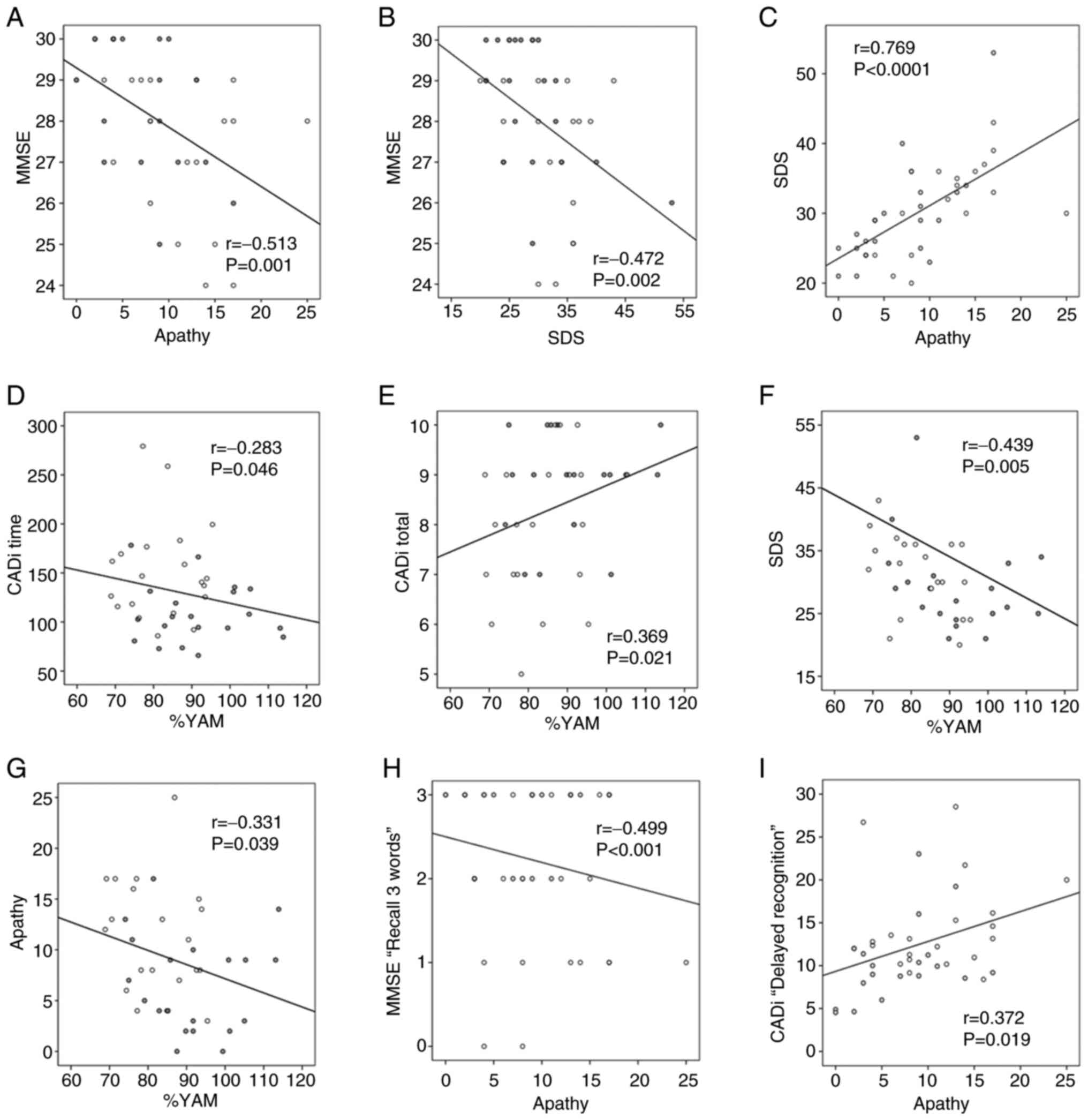

Partial correlation analyses adjusting for age and

baseline values revealed significant associations between cognitive

and mental health indicators. After 12 months of intervention, MMSE

score had significant negative correlations with the apathy score

(Fig. 4A, r=-0.513, P=0.001) and

SDS (Fig. 4B, r=-0.472, P=0.002).

A strong positive correlation was observed between apathy and

depression levels (Fig. 4C,

r=0.769, P<0.0001). Moreover, %YAM had a significant negative

correlation with CADi time (Fig.

4D, r=-0.283, P=0.046) and a positive correlation with CADi

total (Fig. 4E, r=0.369, P=0.021).

The %YAM had significant negative correlations with SDS (Fig. 4F, r=-0.439, P=0.005) and apathy

score (Fig. 4G, r=-0.331, P=0.039)

after 12 months of intervention. The apathy score showed a

significant negative correlation with MMSE subitem ‘Recall 3 words’

(Fig. 4H, r=-0.499, P<0.001),

and a significant positive correlation with CADi time subitem

‘Delayed Recognition’ (Fig. 4I,

r=0.372, P=0.019). A full matrix of partial correlation

coefficients is presented in Table

SIII.

Discussion

This study investigated the effects of daily UBR

consumption over a 12-month period on cognitive performance, mental

health, and bone status in community-dwelling older adults. The

results indicated that MMSE scores at 12 months were significantly

higher in the UBR group compared to the WR group, although the

change from baseline was not statistically significant. In

contrast, UBR intake was associated with the preservation of CADi

total scores and a slower execution time, suggesting a potential

benefit in cognitive processing speed and memory-related tasks.

Additionally, apathy scores significantly decreased in the UBR

group over the intervention period, while no significant changes

were observed in depression scores (SDS). Importantly, CADi and

apathy scores were significantly correlated with bone health

indices (%YAM), highlighting a potential interplay between

cognitive-motivational function and bone density. Although causal

relationships cannot be inferred from the present analyses, the

observed partial correlations between cognitive/apathy scores and

%YAM may indicate a potential association among cognitive,

motivational, and skeletal health in older adults. These findings

warrant further investigation in studies with longitudinal

mediation models. No serious adverse events were reported, and UBR

consumption did not result in notable changes in hepatic or renal

markers, body composition, or metabolic parameters, suggesting that

the intervention was well tolerated and safe for long-term

intake.

Cognitive impairment and fragility fractures mainly

affect the elderly population and significantly increase the

prevalence and incidence of dementia and osteoporosis. Because of

the severe morbidity, long-term disability, and mortality

associated with these conditions, as well as their socioeconomic

impact, there is an urgent global need to develop strategies to

prevent these diseases (5).

Although the causal relationship between dementia and bone

fragility is still under debate, several clinical and

epidemiological reports have shown that patients with dementia,

including AD, exhibit lower BMD, higher susceptibility to falls,

and an increased propensity for fracture compared with their

healthy counterparts (5,36). Retrospective and prospective

studies consistently highlight cognitive decline as a risk factor

for bone fracture, with both sexes experiencing dementia and

osteoporosis as the most common condition (5,37-39).

In a longitudinal study (the Rotterdam Study), Xiao et al.

(3) found that individuals with

lower BMD were more likely to develop dementia later in life,

suggesting that bone fragility may be a risk factor for dementia.

The relationship between dementia and osteoporosis in treatment can

be seen with raloxifene, an osteoporosis drug shown to reduce the

risk of vertebral fractures (40).

The analysis of cognitive function in postmenopausal women,

raloxifene was found to reduce the risk of dementia, especially in

women with MCI (40,41). Furthermore, a systematic review

also showed that raloxifene reduced the risk of MCI and lowered the

risk of AD (42). Thus,

ingredients that improve bone density may also have beneficial

effects on cognition. Although a causal relationship cannot be

established, the observed associations suggest that UBR intake may

contribute to the preservation of both cognitive and bone health.

However, further research is needed to fully understand the complex

relationship between cognitive impairment, BMD decline, and the

mechanism of action of UBR.

Typically, even healthy older adults without MCI or

dementia experience various changes in cognitive abilities as they

age, one of which is decline in recent memory (43). In this study, CADi analysis showed

that UBR intake was associated with an increase in total scores and

a significant reduction in execution time. Furthermore, the CADi

subitem analysis shows a significant increase in ‘Delayed

Recognition’ in the UBR group compared to the WR group. A trend

toward improvement with UBR-intake was also observed in changes in

the MMSE subitem ‘Recall 3 words’ (recent memory scale). These

findings suggest that UBR intake may support recent memory in older

individuals. It is also of interest that UBR intake was associated

with a significant reduction in apathy scores in the elderly;

moreover, these results were significantly correlated with

cognitive abilities and %YAM. In the elderly, several brain areas

(including the prefrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex,

temporal lobe and hippocampus) atrophy with age, leading to MCI and

the subsequent onset of AD, the most common form of

neurodegenerative disease (44).

The earliest pathogenesis of AD is the accumulation of β-amyloid

(Aβ) plaques in the brain, which begin to form more than 20 years

before onset of the disease (44).

Aβ deposition and corticolimbic dysfunction have also been shown to

be positively correlated with the development of apathy and

depression (45,46). In addition, apathy and depression

have been linked with frailty and lower BMD, suggesting that a

comprehensive approach is required to combat dementia (47,48).

In a preclinical study, Okuda et al. reported that chronic

administration of UBR in a mouse model of AD

(senescence-accelerated mouse prone-8) suppressed Aβ accumulation

in the brain and improved cognitive function (49). Therefore, the observed preservation

of cognitive function and reduction in apathy in the UBR intake

group may, at least in part, be associated with the potential role

of UBR in attenuating amyloid burden.

The molecular mechanisms through which UBR may

contribute to cognitive, motivational, and bone-related benefits

remain unclear; however, several bioactive components in UBR are

hypothesized to play a role in these effects. For example, UBR is

richer in minerals (e.g., Ca, Mg, Pi, and Fe) than WR (Table I). Mineral deficiencies can affect

memory function and are a likely cause of age-related cognitive

impairment and mental illness (50-55).

Deficiencies in nutrients also pose serious problems for bone

health in the elderly (56). In

addition, UBR is richer in lipids and dietary fiber than WR and

contains bioactive substances such as ferulic acid, GABA and

g-Oryzanol (Table I). Ferulic acid

has been reported to induce an increase in blood estradiol and

alkaline phosphatase activity in castrated female rats,

consequently preventing a decrease in BMD (54). Ferulic acid has also been reported

to have beneficial effects in dementia and depression and to

inhibit Ab aggregation, oxidative stress and inflammatory responses

(19,55). GABA, a major inhibitory

neurotransmitter, is known for its neuroprotective properties and

potential to preserve cognitive function (17,57-59).

g-Oryzanol has been shown to exert neuroprotective effects by

reducing oxidative stress and neuroinflammation, thereby supporting

cognitive function, and may also contribute to bone health by

inhibiting osteoclast differentiation and reducing bone resorption

through its anti-inflammatory properties (60,61).

Together, these components could synergistically contribute to

preserving cognitive function, reducing apathy via neurotransmitter

modulation, and supporting bone quality through anti-inflammatory

and antioxidant mechanisms. In addition, B vitamins, which are

abundant in UBR (Table I), are

known to be closely involved in the formation of collagen

crosslinks in bone, and a high correlation has been reported

between insufficient vitamin B6 intake and decreased bone density

(62,63). Recently, elevated serum

homocysteine levels due to vitamin B6 deficiency have been shown to

have a negative impact on bone metabolism and result in an

increased fracture risk (64,65).

Increased homocysteine levels due to a deficiency of B vitamins

increase the risk of dementia and other related diseases (66). Various functional components in

UBR, along with their potential synergistic interactions, may help

prevent cognitive decline and bone loss. These findings underscore

the need for further mechanistic research to clarify the biological

pathways involved.

The benefits of regular intake of BR for human

physiology and disease prevention have been well studied (10,67,68).

However, continuous intake of regular BR is often difficult for

various reasons, and in some cases, it has been associated with

health concerns such as digestive malabsorption (69). In this study, long-term consumption

of UBR showed no difference between the two groups in terms of

changes in liver function, renal function, lipid metabolism, and

carbohydrate metabolism before and after intervention (Table II). Furthermore, participant

adherence was high, and no physical complaints related to chronic

intake were reported during the intervention period. These results

demonstrate that the long-term consumption of UBR does not

interfere with daily life in the elderly individuals and that UBR

is a sustainable and safe staple food. Given its low cost, wide

availability, and ease of daily consumption, UBR may serve as a

feasible dietary approach for older adults. Compared to

pharmaceutical interventions, UBR may offer a more accessible and

sustainable strategy for maintaining cognitive and bone health,

particularly in community-dwelling populations.

Despite the encouraging findings, this study has

several limitations. First, the relatively small sample size may

have limited the power to detect subtle effects and increases the

risk of type II error. For example, the MMSE difference, while

statistically significant, did not exceed the established MCID (2-3

points), suggesting limited clinical relevance. Similarly, some

secondary outcomes showed non-significant results despite small to

moderate effect sizes. These findings should be interpreted

cautiously, and future studies with larger samples are needed to

validate these effects. Second, the trial was retrospectively

registered, which we acknowledge as a limitation. Future studies

should ensure prospective registration to enhance transparency,

reduce reporting bias, and strengthen the credibility of the

findings. Third, the assessment of bone health relied solely on

calcaneal QUS, using %YAM as the endpoint. While %YAM is widely

used in Japan for screening purposes, it is not a direct measure of

BMD and lacks internationally standardized diagnostic thresholds.

Unlike DXA, which is the gold standard for diagnosing osteoporosis,

QUS primarily reflects bone quality and structural integrity.

Furthermore, the QUS device used in this study did not generate

validated T-scores, which are essential for classification based on

WHO criteria. As such, clinical interpretation of bone status and

risk based solely on %YAM should be approached with caution. This

limitation underscores the need for future studies to incorporate

DXA or QUS devices that provide validated T-scores to allow for

more clinically meaningful assessment of bone health. Fourth,

although the sample size limited stratified analysis, the effects

of UBR intake may vary according to baseline characteristics such

as age, sex, physical activity, vitamin D exposure, and dietary

patterns. These potential effect modifiers should be considered in

future studies with larger and more diverse populations. Fifth,

although complete participant blinding was not feasible due to

perceptible differences between UBR and WR, all outcome assessments

and data analyses were conducted by staff who were blinded to group

allocation, minimizing assessment bias. Finally, the lack of

mechanistic investigation limits our ability to draw conclusions

about the underlying biological effects of UBR.

In conclusion, daily intake of UBR over 12 months

was associated with preservation of cognitive function, reduced

apathy, and maintenance of bone-related parameters in older adults,

without adverse effects. While causality cannot be established,

these findings support the potential of UBR as a functional staple

food to help mitigate age-related declines in cognition and bone

health. Further large-scale, mechanistically informed studies are

needed to confirm and expand upon these observations.

Supplementary Material

Sensitivity analyses of between-group

differences in MMSE endpoint under alternative models.

Exploratory sensitivity analyses and

corresponding effect sizes for secondary outcomes at 12 months

Partial correlation coefficients

between cognitive, emotional and bone-related outcomes at 12

months.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: This work was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid for

Scientific Research (C) from the Ministry of Education Culture,

Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (grant no. 26500008).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Author's contributions

MH contributed to the conceptualization, design of

the study and was responsible for project administration, including

ethical approvals and coordination among research sites. KM, SY, YK

and MH contributed to formal analysis, data interpretation, and

data curation. KM, SY, YK and MH were involved in clinical

assessments. KM and MH contributed to the development of the study

methodology, including the design of outcome measures and

statistical analysis plans. SY, OS, KY, HKis and MH provided

essential experimental equipment and resources required for the

conduct of the study. HN, TM, and HKin managed rice processing and

the provision of test food. TM, HKin and MH coordinated participant

recruitment. KM, YK, HN, TM, HKin and MH contributed to data

acquisition through participant support and intervention

management. TM, HKin, KY and MH contributed to the design and

interpretation of nutritional analysis. KM wrote the first draft of

the manuscript and performed data visualization. SY, OS, HKis and

MH contributed to the interpretation of results and critical review

of the manuscript. MH secured the research funding. SY, OS, KY,

HKis and MH supervised the study. KM, YK and MH confirmed the

authenticity of all raw data. All authors read and approved the

final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of

the Shimane University School of Medicine (approval no. 1940-2504).

All procedures were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of

Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all

participants prior to their inclusion in the study.

Patient consent for publication

All participants provided written informed consent

for participation in the study and for the publication of

anonymized data.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Authors' information

ORCID: Kentaro Matsuzaki, 0000-0002-5942-8840; Shozo

Yano, 0000-0002-9210-2949; Hiroko Kishi, 0000-0003-2896-7355;

Michio Hashimoto, 0000-0002-3726-4347.

References

|

1

|

Loskutova N, Honea RA, Vidoni ED, Brooks

WM and Burns JM: Bone density and brain atrophy in early

Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 18:777–785. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Mehta K, Thandavan SP, Mohebbi M, Pasco

JA, Williams LJ, Walder K, Ng BL and Gupta VB: Depression and bone

loss as risk factors for cognitive decline: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. 76(101575)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Xiao T, Ghatan S, Mooldijk SS, Trajanoska

K, Oei L, Gomez MM, Ikram MK, Rivadeneira F and Ikram MA:

Association of bone mineral density and dementia: The Rotterdam

study. Neurology. 100:e2125–e2133. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Filler J, Georgakis MK and Dichgans M:

Risk factors for cognitive impairment and dementia after stroke: A

systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Healthy Longev.

5:e31–e44. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Ruggiero C, Baroni M, Xenos D, Parretti L,

Macchione IG, Bubba V, Laudisio A, Pedone C, Ferracci M, Magierski

R, et al: Dementia, osteoporosis and fragility fractures: Intricate

epidemiological relationships, plausible biological connections,

and twisted clinical practices. Ageing Res Rev.

93(102130)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Mehta K, Mohebbi M, Pasco JA, Williams LJ,

Walder K, Ng BL and Gupta VB: Impact of mood disorder history and

bone health on cognitive function among men without dementia. J

Alzheimers Dis. 96:381–393. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Ichinose T, Kato M, Matsuzaki K, Tanabe Y,

Tachibana N, Morikawa M, Kato S, Ohata S, Ohno M, Wakatsuki H, et

al: Beneficial effects of docosahexaenoic Acid-enriched milk

beverage intake on cognitive function in healthy elderly Japanese:

A 12-month randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J

Funct Foods. 74(104195)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Lisco G, Disoteo OE, De Tullio A, De

Geronimo V, Giagulli VA, Monzani F, Jirillo E, Cozzi R,

Guastamacchia E, De Pergola G and Triggiani V: Sarcopenia and

diabetes: A detrimental liaison of advancing age. Nutrients.

16(63)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Hashimoto M, Hossain S, Al Mamun A,

Matsuzaki K and Arai H: Docosahexaenoic acid: One molecule diverse

functions. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 37:579–597. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Hashimoto M, Hossain S, Matsuzaki K, Shido

O and Yoshino K: The journey from white rice to ultra-high

hydrostatic pressurized brown rice: An excellent endeavor for ideal

nutrition from staple food. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 62:1502–1520.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Matsuzaki K, Nakajima A, Guo Y and Ohizumi

Y: A narrative review of the effects of citrus peels and extracts

on human brain health and metabolism. Nutrients.

14(1847)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Hashimoto M, Yamashita K, Kato S, Tamai T,

Tanabe Y, Mitarai M, Matsumoto I and Ohno M: Beneficial effects of

daily dietary omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation on

age-related cognitive decline in elderly Japanese with very mild

dementia: A 2-year randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled

trial. J Aging Res Clin Pract. 1:193–201. 2012.

|

|

13

|

Hashimoto M, Matsuzaki K, Maruyama K,

Hossain S, Sumiyoshi E, Wakatsuki H, Kato S, Ohno M, Tanabe Y,

Kuroda Y, et al: Perilla seed oil in combination with

nobiletin-rich ponkan powder enhances cognitive function in healthy

elderly Japanese individuals: A possible supplement for brain

health in the elderly. Food Funct. 13:2768–2781. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Hashimoto M, Matsuzaki K, Maruyama K,

Sumiyoshi E, Hossain S, Wakatsuki H, Kato S, Ohno M, Tanabe Y,

Kuroda Y, et al: Perilla frutescens seed oil combined with Anredera

cordifolia leaf powder attenuates age-related cognitive decline by

reducing serum triglyceride and glucose levels in healthy elderly

Japanese individuals: A possible supplement for brain health. Food

Funct. 13:7226–7239. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Ichinose T, Matsuzaki K, Kato M, Tanabe Y,

Tachibana N, Morikawa M, Kato S, Ohata S, Ohno M, Wakatsuki H, et

al: Intake of docosahexaenoic Acid-enriched milk beverage prevents

Age-related cognitive decline and decreases serum bone resorption

marker levels. J Oleo Sci. 70:1829–1838. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Kaup RM, Khayyal MT and Verspohl EJ:

Antidiabetic effects of a standardized Egyptian rice bran extract.

Phytother Res. 27:264–271. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Savage K, Firth J, Stough C and Sarris J:

GABA-modulating phytomedicines for anxiety: A systematic review of

preclinical and clinical evidence. Phytother Res. 32:3–18.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Kokumai T, Ito J, Kobayashi E, Shimizu N,

Hashimoto H, Eitsuka T, Miyazawa T and Nakagawa K: Comparison of

blood profiles of γ-oryzanol and ferulic acid in rats after oral

intake of γ-oryzanol. Nutrients. 11(1174)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Jalali A, Firouzabadi N and Zarshenas MM:

Pharmacogenetic-based management of depression: Role of traditional

Persian medicine. Phytother Res. 35:5031–5052. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Hayashi R: High pressure in bioscience and

biotechnology: pure science encompassed in pursuit of value.

Biochim Biophys Acta. 1595:397–399. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Yoshino K and Inoue T: Ultra high pressure

and food processing technology. J Highly Water Pressurized Food

Eng. 1:5–14. 2016.

|

|

22

|

Kuroda Y, Matsuzaki K, Wakatsuki H, Shido

O, Harauma A, Moriguchi T, Sugimoto H, Yamaguchi S, Yoshino K and

Hashimoto M: Influence of ultra-High hydrostatic pressurizing brown

rice on cognitive functions and mental health of elderly Japanese

individuals: A 2-year randomized and controlled trial. J Nutr Sci

Vitaminol (Tokyo). 65 (Suppl 1):S80–S87. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Matsuzaki K, Yano S, Sumiyoshi E, Shido O,

Katsube T, Tabata M, Okuda M, Sugimoto H, Yoshino K and Hashimoto

M: Long-term ultra-high hydrostatic pressurized brown rice intake

prevents bone mineral density decline in elderly Japanese

individuals. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo). 65 (Suppl 1):S88–S92.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Sumiyoshi E, Matsuzaki K, Sugimoto N,

Tanabe Y, Hara T, Katakura M, Miyamoto M, Mishima S and Shido O:

Sub-chronic consumption of dark chocolate enhances cognitive

function and releases nerve growth factors: A parallel-group

randomized trial. Nutrients. 11(2800)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Hashimoto M, Matsuzaki K, Hossain S, Ito

T, Wakatsuki H, Tanabe Y, Ohno M, Kato S, Yamashita K and Shido O:

Perilla Seed oil enhances cognitive function and mental health in

healthy elderly Japanese individuals by enhancing the biological

antioxidant potential. Foods. 10(1130)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Hashimoto M, Matsuzaki K, Kato S, Hossain

S, Ohno M and Shido O: Twelve-month studies on perilla oil intake

in Japanese adults-possible supplement for mental health. Foods.

9(530)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Folstein MF, Folstein SE and McHugh PR:

‘Mini-mental state’. A practical method for grading the cognitive

state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 12:189–198.

1975.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Imai Y and Hasegawa K: The revised

Hasegawa's dementia scale (HDS-R)-evaluation of its usefulness as a

screening test for dementia. J.H.K.C Psych. 4:2–24. 1994.

|

|

29

|

Dubois B, Slachevsky A, Litvan I and

Pillon B: The FAB: A frontal assessment battery at bedside.

Neurology. 55:1621–1626. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Onoda K, Hamano T, Nabika Y, Aoyama A,

Takayoshi H, Nakagawa T, Ishihara M, Mitaki S, Yamaguchi T, Oguro

H, et al: Validation of a new mass screening tool for cognitive

impairment: Cognitive Assessment for Dementia, iPad version. Clin

Interv Aging. 8:353–360. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Okada K, Kobayashi S, Aoki K, Suyama N and

Yamaguchi S: Assessment of motivational loss in poststroke patients

using the Japanese version of Starkstein's Apathy Scale. Jpn J

Stroke. 20:318–327. 1998.

|

|

32

|

Zung WWK: A Self-rating depression scale.

Arch Gen Psychiatry. 12:63–70. 1965.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Yamazaki K, Kushida K, Ohmura A, Sano M

and Inoue T: Ultrasound bone densitometry of the os calcis in

Japanese women. Osteoporosis Int. 4:220–225. 1994.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Soen S, Fukunaga M, Sugimoto T, Sone T,

Fujiwara S, Endo N, Gorai I, Shiraki M, Hagino H, Hosoi T, et al:

Diagnostic criteria for primary osteoporosis: Year 2012 revision. J

Bone Miner Metab. 31:247–257. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Matsuzaki K, Hossain S, Wakatsuki H,

Tanabe Y, Ohno M, Kato S, Shido O and Hashimoto M: Perilla seed oil

improves bone health by inhibiting bone resorption in healthy

Japanese adults: A 12-month, randomized, double-blind,

placebo-controlled trial. Phytother Res. 37:2230–2241.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Zhao Y, Shen L and Ji HF: Alzheimer's

disease and risk of hip fracture: A meta-analysis study. Sci World

J. 2012:1–5. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Baker NL, Cook MN, Arrighi HM and Bullock

R: Hip fracture risk and subsequent mortality among Alzheimer's

disease patients in the United Kingdom, 1988-2007. Age Ageing.

40:49–54. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Lai SW, Chen YL, Lin CL and Liao KF:

Alzheimer's disease correlates with greater risk of hip fracture in

older people: A cohort in Taiwan. J Am Geriatr Soc. 61:1231–1232.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Wang HK, Hung CM, Lin SH, Tai YC, Lu K,

Liliang PC, Lin CW, Lee YC, Fang PH, Chang LC and Li YC: Increased

risk of hip fractures in patients with dementia: A nationwide

population-based study. BMC Neurol. 14(175)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Yaffe K, Krueger K, Cummings SR, Blackwell

T, Henderson VW, Sarkar S, Ensrud K and Grady D: Effect of

raloxifene on prevention of dementia and cognitive impairment in

older women: The Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation (MORE)

randomized trial. Am J Psychiatry. 162:683–690. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Jacobsen DE, Melis RJF, Verhaar HJJ and

Olde Rikkert MGM: Raloxifene and tibolone in elderly women: A

randomized, double-blind, double-dummy, placebo-controlled trial. J

Am Med Dir Assoc. 13:189.e1–e7. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Yang ZD, Yu J and Zhang Q: Effects of

raloxifene on cognition, mental health, sleep and sexual function

in menopausal women: A systematic review of randomized controlled

trials. Maturitas. 75:341–348. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Golomb J, de Leon MJ, Kluger A, George AE,

Tarshish C and Ferris SH: Hippocampal atrophy in normal aging. An

association with recent memory impairment. Arch Neurol. 50:967–973.

1993.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Jack CR Jr, Knopman DS, Jagust WJ,

Petersen RC, Weiner MW, Aisen PS, Shaw LM, Vemuri P, Wiste HJ,

Weigand SD, et al: Tracking pathophysiological processes in

Alzheimer's disease: An updated hypothetical model of dynamic

biomarkers. Lancet Neurol. 12:207–216. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Mori T, Shimada H, Shinotoh H, Hirano S,

Eguchi Y, Yamada M, Fukuhara R, Tanimukai S, Zhang MR, Kuwabara S,

et al: Apathy correlates with prefrontal amyloid β deposition in

Alzheimer's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 85:449–455.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Moriguchi S, Takahata K, Shimada H, Kubota

M, Kitamura S, Kimura Y, Tagai K, Tarumi R, Tabuchi H, Meyer JH, et

al: Excess tau PET ligand retention in elderly patients with major

depressive disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 26:5856–5863. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Parrotta I, Maltais M, Rolland Y,

Spampinato DA, Robert P, de Souto Barreto P and Vellas B: MAPT/DSA

group. The association between apathy and frailty in older adults:

A new investigation using data from the Mapt study. Aging Ment

Health. 24:1985–1989. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Voorend CGN, van Buren M, Berkhout-Byrne

NC, Kerckhoffs APM, van Oevelen M, Gussekloo J, Richard E, Bos WJW

and Mooijaart SP: Apathy symptoms, physical and cognitive function,

health-related quality of life, and mortality in older patients

with CKD: A longitudinal observational study. Am J Kidney Dis.

83:162–172.e1. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Okuda M, Fujita Y, Katsube T, Tabata H,

Yoshino K, Hashimoto M and Sugimoto H: Highly water pressurized

brown rice improves cognitive dysfunction in senescence-accelerated

mouse prone 8 and reduces amyloid beta in the brain. BMC Complement

Altern Med. 18(110)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Morris MC, Schneider JA and Tangney CC:

Thoughts on B-vitamins and dementia. J Alzheimers Dis. 9:429–433.

2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Gil Martínez V, Avedillo Salas A and

Santander Ballestín S: Vitamin supplementation and dementia: A

systematic review. Nutrients. 14(1033)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Fekete M, Lehoczki A, Tarantini S,

Fazekas-Pongor V, Csípő T, Csizmadia Z and Varga JT: Improving

cognitive function with nutritional supplements in aging: A

comprehensive narrative review of clinical studies investigating

the effects of vitamins, minerals, antioxidants, and other dietary

supplements. Nutrients. 15(5116)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Dai Z and Koh WP: B-vitamins and bone

health-a review of the current evidence. Nutrients. 7:3322–3346.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Sassa S, Kikuchi T, Shinoda H, Suzuki S,

Kudo H and Sakamoto S: Preventive effect of ferulic acid on bone

loss in ovariectomized rats. In Vivo. 17:277–280. 2003.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Di Giacomo S, Percaccio E, Gullì M, Romano

A, Vitalone A, Mazzanti G, Gaetani S and Di Sotto A: Recent

advances in the neuroprotective properties of ferulic acid in

Alzheimer's disease: A narrative review. Nutrients.

14(3709)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Fujii K, Kajiwara T and Kurosu H: Effect

of vitamin B6 deficiency on the crosslink formation of collagen.

FEBS Lett. 97:193–195. 1979.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Murari G, Liang DR, Ali A, Chan F,

Mulder-Heijstra M, Verhoeff NPLG, Herrmann N, Chen JJ and Mah L:

Prefrontal GABA levels correlate with memory in older adults at

high risk for Alzheimer's disease. Cereb Cortex Commun.

1(tgaa022)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Inotsuka R, Uchimura K, Yamatsu A, Kim M

and Katakura Y: γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA) activates neuronal cells

by inducing the secretion of exosomes from intestinal cells. Food

Funct. 11:9285–9290. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Meng N, Pan P, Hu S, Miao C, Hu Y, Wang F,

Zhang J and An L: The molecular mechanism of γ-aminobutyric acid

against AD: the role of CEBPα/circAPLP2/miR-671-5p in regulating

CNTN1/2 expression. Food Funct. 14:2082–2095. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Rungratanawanich W, Cenini G, Mastinu A,

Sylvester M, Wilkening A, Abate G, Bonini SA, Aria F, Marziano M,

Maccarinelli G, et al: γ-Oryzanol improves cognitive function and

modulates hippocampal proteome in mice. Nutrients.

11(753)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Muhammad SI, Maznah I, Mahmud R, Zuki AB

and Imam MU: Upregulation of genes related to bone formation by

γ-amino butyric acid and γ-oryzanol in germinated brown rice is via

the activation of GABAB-receptors and reduction of serum IL-6 in

rats. Clin Interv Aging. 8:1259–1271. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Welan R: Effect of vitamin B6 on

osteoporosis fracture. J Bone Metab. 30:141–147. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

van Meurs JBJ, Dhonukshe-Rutten RAM,

Pluijm SMF, van der Klift M, de Jonge R, Lindemans J, de Groot

LCPGM, Hofman A, Witteman JCM, van Leeuwen JPTM, et al:

Homocysteine levels and the risk of osteoporotic fracture. N Engl J

Med. 350:2033–2041. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Fratoni V and Brandi ML: B vitamins,

homocysteine and bone health. Nutrients. 7:2176–2192.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Seshadri S, Beiser A, Selhub J, Jacques

PF, Rosenberg IH, D'Agostino RB, Wilson PWF and Wolf PA: Plasma

homocysteine as a risk factor for dementia and Alzheimer's disease.

N Engl J Med. 346:476–483. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Tanaka K, Ao M and Kuwabara A:

Insufficiency of B vitamins with its possible clinical

implications. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 67:19–25. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

67

|

Itoh M, Nishibori N, Sagara T, Horie Y,

Motojima A and Morita K: Extract of fermented brown rice induces

apoptosis of human colorectal tumor cells by activating

mitochondrial pathway. Phytother Res. 26:1661–1666. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

68

|

Praengam K, Sahasakul Y, Kupradinun P,

Sakarin S, Sanitchua W, Rungsipipat A, Rattanapinyopituk K,

Angkasekwinai P, Changsri K, Mhuantong W, et al: Brown rice and

retrograded brown rice alleviate inflammatory response in dextran

sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis mice. Food Funct. 8:4630–4643.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

69

|

Saleh ASM, Wang P, Wang N, Yang L and Xiao

Z: Brown rice versus white rice: nutritional quality, potential

health benefits, development of food products, and preservation

technologies. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 18:1070–1096.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|