Introduction

Currently, rectal cancer ranks third among all

common malignant tumors worldwide and is primarily treated with

laparoscopic surgery. Anastomotic fistulas are a serious

postoperative complication of rectal cancer surgery, which

adversely affects patient recovery and prognosis (1). A key contributing factor to

anastomotic fistulas is insufficient blood supply to the

anastomotic site (2,3). However, reducing the incidence of

postoperative anastomotic fistulas in laparoscopic surgery for

rectal cancer remains challenging. At present, surgeons mainly rely

on subjective judgement when assessing intestinal blood supply

during laparoscopic surgery, such as whether the tissue around the

anastomosis appears reddish, if the small arteries are pulsating or

if there is bleeding at the incisal edge. This approach carries a

risk of error, which can lead to the occurrence of anastomotic

fistulas (4). This is particularly

critical in radical surgery for rectal cancer, wherein blood supply

to the proximal colon, following high ligation of the inferior

mesenteric artery, depends on the marginal artery arc. If blood

supply to the proximal colon is inaccurately assessed and

anastomosis is performed, postoperative anastomotic fistulas may

develop.

Indocyanine green (ICG) fluorescence imaging is a

simple and effective method for evaluating tissue perfusion during

laparoscopic surgery. It is safe and feasible, demonstrating

promising potential for clinical application (5,6). ICG

is a near-infrared contrast agent known for its biocompatibility

(7,8). When exposed to external light with

wavelengths ranging from 750 to 800 nm, ICG emits near-infrared

light at longer wavelengths. Due to the inherent property of ICG to

emit light within the near-infrared spectrum, it is typically

unaffected by potential spontaneous fluorescence arising from blood

components, such as hemoglobin and water. Leveraging on this

characteristic, the ICG molecular fluorescence imaging system

integrates fluorescence reception and imaging with fluorescence

excitation. It applies a computer image processing system that is

coupled to a highly sensitive near-infrared fluorescence camera and

a near-infrared excitation light source to produce ICG fluorescence

images. Upon administration into the human body, ICG undergoes

metabolism in the liver and is excreted in its intact molecular

form through the bile duct, ultimately being eliminated through the

feces. Notably, it does not participate in the enterohepatic

circulation and exhibits relatively rapid metabolic clearance. The

present study aimed to investigate the efficacy of ICG fluorescence

imaging by retrospectively analyzing its application in

laparoscopic radical resection for rectal cancer and examining the

clinical and pathological characteristics, surgical outcomes,

postoperative recovery and complications. The feasibility and

safety of ICG fluorescence imaging for assessing the blood supply

at the anastomotic site are discussed, providing

evidence-based support for its future application in

colorectal surgeries.

Patients and methods

Study participants

This is an opportunistic cohort study. The clinical

and pathological data of 12 patients with rectal cancer treated at

the Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery, the Second Affiliated

Hospital of Fujian Medical University (Quanzhou, China) between

January and May 2024 were retrospectively analyzed. The inclusion

criteria were preoperative colonoscopy and pathology confirming

rectal cancer, patients who underwent laparoscopic radical

resection of rectal cancer, with normal liver function prior to

surgery, no history of allergy to ICG and aged between 18 and 75

years. The exclusion criteria were preoperative liver dysfunction,

history of allergy to ICG or iodine, uncontrolled comorbidities and

incomplete clinical and pathological data. The present study was

approved by the Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital

of Fujian Medical University (approval no. 2021368).

Surgical procedures

Laparoscopic surgery was performed by following the

standard procedure for laparoscopic radical resection for rectal

cancer. After tumor resection, 25 mg ICG [Eisai (Liaoning)

Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.] was dissolved in 10 ml sterile water for

injection before anastomosis of the proximal and distal intestinal

segments. ICG was administered at 0.2 mg/kg through a peripheral or

central vein. The intraoperative laparoscopic procedure utilized

the OptoMedic fluorescence laparoscope system (Guangdong OptoMedic

Technologies, Inc.). The optimal timing for intraoperative blood

supply assessment occurs within 3-5 min following the injection of

ICG into the bloodstream. During this period, both the completeness

and intensity of fluorescence in the anastomosis and adjacent

intestinal wall are evaluated. Given that ICG has a half-life of

3-4 min, it is almost completely metabolized within 10-20 min

following injection into the bloodstream. Consequently, if

required, re-administration of ICG can be performed. However, it

was advisable that there be a minimum interval of ≥15 min between

successive administrations. The blood supply assessment system

devised by Sherwinter et al (9) was used in the fluorescence mode: A

score of ≥3 (uniform fluorescence distribution at the intestinal

transection or anastomotic site) indicated good blood supply, 2

(uneven fluorescence distribution) indicated poor blood supply and

1 (no fluorescence observed) indicated no blood supply. If

intraoperative evaluation revealed poor intestinal blood supply,

the resection range would then be extended appropriately to ensure

sufficient blood supply to the proximal and distal intestinal

segments at the anastomosis site. After anastomosis, the same dose

of ICG solution was injected under fluorescence mode to observe the

blood supply at the anastomotic site. In this study, ICG was

utilized intraoperatively, with all procedures monitored by life

support equipment and anesthesiologists. Due to the rapid

metabolism of ICG within the body, any acute adverse reactions,

such as allergies that may arise following its intraoperative use,

can be addressed promptly (10).

Outcome measures

The following parameters were recorded: i) General

characteristics, namely sex, age, body mass index (BMI), maximum

tumor diameter, distance from tumour to anal verge and

postoperative tumour-nodes-metastasis (TNM) staging; ii) surgical

parameters, namely initial imaging time after ICG injection,

duration of imaging, duration of operation, intraoperative blood

loss and length of resected bowel; and iii) (3) postoperative recovery, specifically

time to first postoperative flatus, time to first intake of liquid

food, postoperative length of hospital stay and occurrence of

postoperative complications. The time of the first postoperative

flatus is primarily related to the recovery of intestinal function

following surgery. The time to first intake of liquid food is

typically two days after the first postoperative flatus. The

standardized discharge criteria for rectal cancer surgery include

the following: Absence of fever for >48 h, restoration of

intestinal function, no infection at the incision site and

independent ambulation. Therefore, these indicators are not

influenced by factors other than the utilization of fluorescence

imaging. All patients were monitored for a period of 1 year

following their discharge. After the surgery, it is recommended

that blood routine tests, biochemical analyses, CEA and CA19-9

levels, as well as other relevant indicators are re-evaluated every

three months. Additionally, chest and abdominal CT scans should be

conducted every six months, while a colonoscopy is advised to take

place one year post-operation.

Statistical analysis

The aforementioned indicators were statistically

analyzed using the Excel software 16.0 (Microsoft Corp.), employing

descriptive statistical methods. For measurement data, the median

(with range) was utilized for representation. By contrast, for

categorical data, the frequency of cases was reported.

Results

General characteristics

The 12 patients included 10 male and 2 female

patients, with a median age of 61 years (range, 53-74 years). The

BMI was 22.5 kg/m² (range, 18.0-31.2 kg/m²), the median maximum

tumour diameter was 3.9 cm (range: 1.7-6.5 cm) and the distance

from the tumour to the anal verge was 8.5 cm (range, 7.0-13.0 cm).

Postoperative TNM staging revealed that one patient was in stage I,

three patients were in stage II and eight were in stage III

(Table I). The table contains the

data for each individual patient.

| Table IGeneral patient characteristics. |

Table I

General patient characteristics.

| Patient no. | Sex | Age, years | BMI,

kg/m2 | Max tumour diameter,

cm | Distance from the

tumour to the anal verge, cm | Postoperative TNM

stage |

|---|

| 1 | Male | 74 | 21.484 | 5.5 | 8 | II |

| 2 | Male | 61 | 21.971 | 5 | 7 | III |

| 3 | Male | 73 | 17.959 | 6.5 | 7 | II |

| 4 | Male | 56 | 19.355 | 4.5 | 8 | III |

| 5 | Female | 53 | 24.877 | 3.6 | 10 | III |

| 6 | Male | 59 | 25.712 | 2.1 | 10 | II |

| 7 | Male | 55 | 23.437 | 5.5 | 8 | III |

| 8 | Male | 66 | 21.358 | 2.7 | 10 | I |

| 9 | Male | 55 | 28.72 | 3.3 | 8 | III |

| 10 | Male | 73 | 31.221 | 3 | 13 | III |

| 11 | Male | 67 | 20.55 | 4.2 | 9 | III |

| 12 | Male | 61 | 22.985 | 1.7 | 10 | III |

Surgical outcomes

The patients completed the surgery and showed no

allergic reactions during the procedure. None of the patients

underwent prophylactic ileostomy. Before anastomosis, the patients

were assessed visually and intestinal blood supply was deemed

sufficient. In two patients, conventional laparoscopy showed good

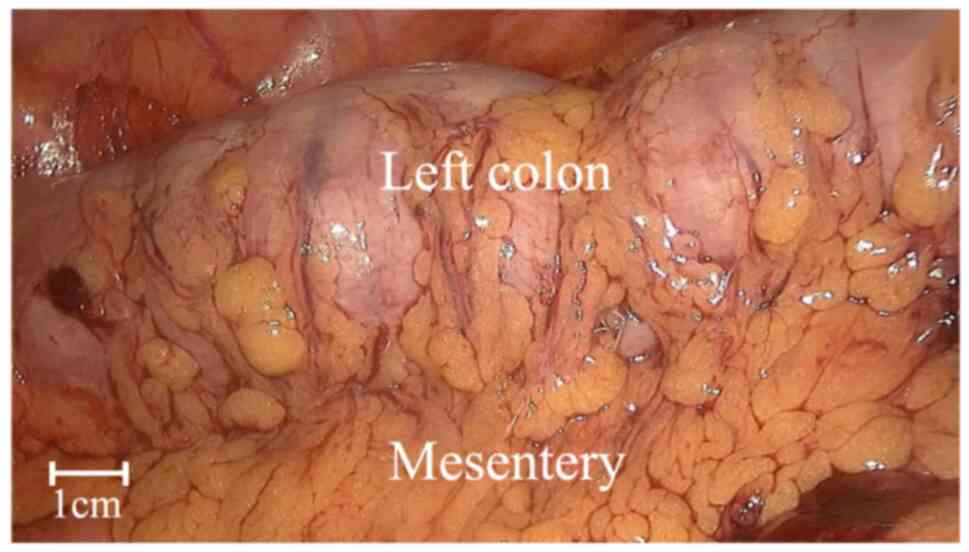

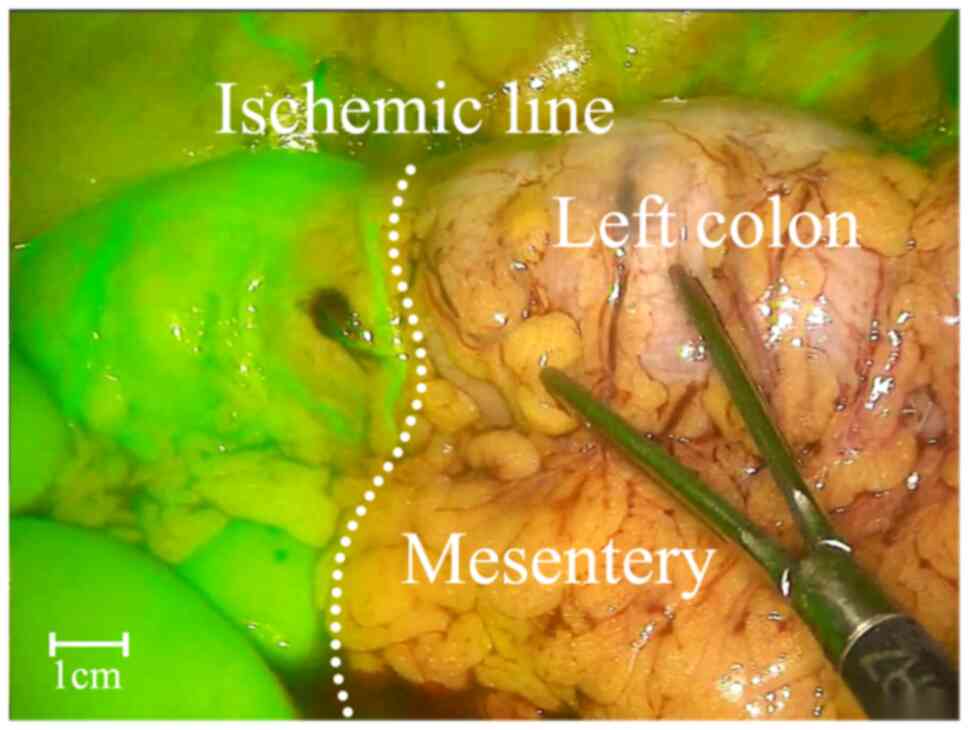

blood supply to the intestines before anastomosis (Fig. 1). However, ICG fluorescence imaging

demonstrated poor blood supply in the proximal intestinal segment,

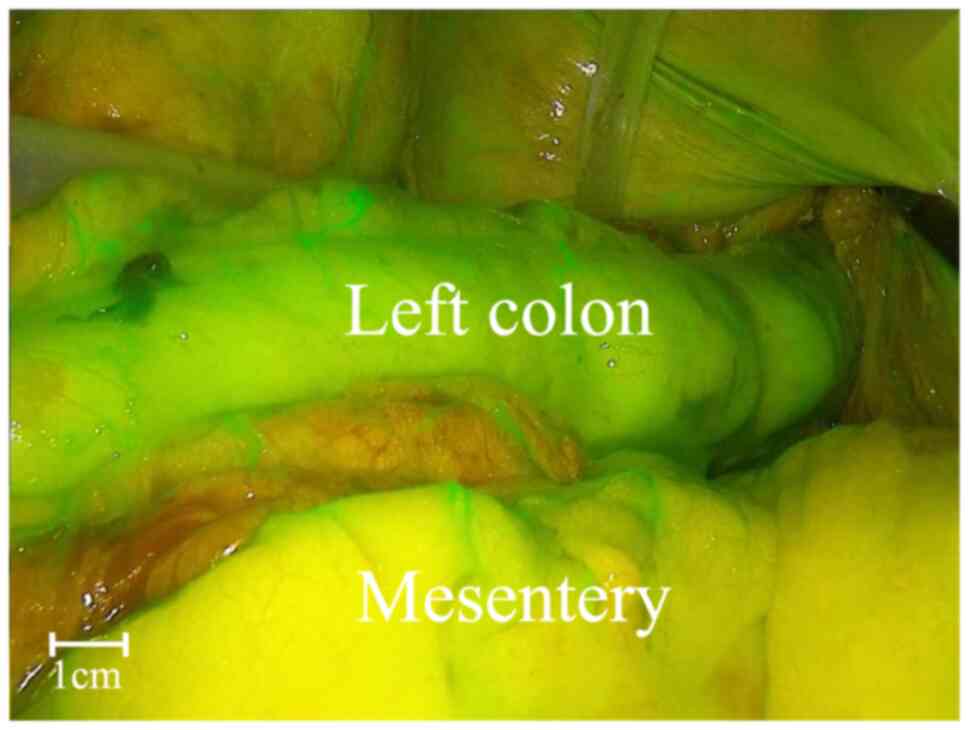

necessitating extended resection (Sherwinter score, 1; Fig. 2). After resection, repeat

fluorescence imaging displayed good blood supply. Following

anastomosis, the same dose of ICG was injected and fluorescence

imaging confirmed adequate blood supply to the anastomosis site

(Sherwinter score, ≥3; Fig. 3).

Representative images are presented in the figures. In the

remaining patients, ICG fluorescence imaging before and after

anastomosis showed good blood supply (Sherwinter score ≥3), meaning

no extended resections were performed. The initial imaging time

after ICG injection for all patients was 44 sec (range, 31-69 sec),

the duration of imaging was 4 min (range, 3-6 min) and the duration

of the operation was 146 min (range: 112-193 min). The median

volume of intraoperative blood loss was 26.5 ml (range: 21.0-39.0

ml) and the length of resected bowel was 18 cm (range, 9.0-25.5 cm)

(Table II). The table contains

the data for each individual patient.

| Table IIGeneral characteristics. |

Table II

General characteristics.

| Patient no. | Initial imaging

time after indocyanine green injection | Duration of

imaging, min | Duration of

operation, min | Intraoperative

blood loss, ml | Length of resected

bowel, cm |

|---|

| 1 | Male | 74 | 21.484 | 5.5 | 8 |

| 2 | Male | 61 | 21.971 | 5 | 7 |

| 3 | Male | 73 | 17.959 | 6.5 | 7 |

| 4 | Male | 56 | 19.355 | 4.5 | 8 |

| 5 | Female | 53 | 24.877 | 3.6 | 10 |

| 6 | Male | 59 | 25.712 | 2.1 | 10 |

| 7 | Male | 55 | 23.437 | 5.5 | 8 |

| 8 | Male | 66 | 21.358 | 2.7 | 10 |

| 9 | Male | 55 | 28.72 | 3.3 | 8 |

| 10 | Male | 73 | 31.221 | 3 | 13 |

| 11 | Male | 67 | 20.55 | 4.2 | 9 |

| 12 | Male | 61 | 22.985 | 1.7 | 10 |

Postoperative recovery

The time to first postoperative flatus was 2 days

(range, 1-3 days), the time to first intake of liquid food was 4

days (range, 3-5 days) and the postoperative length of hospital

stay was 8 days (range, 7-9 days). No postoperative complications,

such as anastomotic bleeding, anastomotic fistulas,

intra-abdominal bleeding, intra-abdominal infection

or intestinal obstruction, could be observed in all patients. The

aforementioned data are provided in Table III. The table contains the data

for each individual patient. No instances of tumour recurrence,

metastasis or long-term complications, such as intestinal

obstruction or anastomotic stricture, were observed in any of the

patients 1 year following the surgery.

| Table IIIPostoperative recovery. |

Table III

Postoperative recovery.

| Patient no. | Time to first

postoperative flatus, days | Time to first

intake of liquid food, days | Postoperative

length of hospital stay, days | Occurrence of

postoperative complications |

|---|

| 1 | 3 | 5 | 9 | None |

| 2 | 1 | 3 | 7 | None |

| 3 | 1 | 3 | 7 | None |

| 4 | 2 | 4 | 8 | None |

| 5 | 2 | 4 | 8 | None |

| 6 | 2 | 4 | 8 | None |

| 7 | 1 | 3 | 7 | None |

| 8 | 2 | 4 | 8 | None |

| 9 | 1 | 3 | 7 | None |

| 10 | 1 | 3 | 7 | None |

| 11 | 2 | 4 | 8 | None |

| 12 | 2 | 4 | 8 | None |

Discussion

Anastomotic fistulas are a severe complication

following rectal cancer surgery, which leads to prolonged hospital

stays, increased costs and higher mortality rates, adversely

affecting short- and long-term outcomes of patients

(11-13).

Despite advances in neoadjuvant therapy and the implementation of

total mesorectal excision, as well as the development of

laparoscopic surgical instruments and improvements in surgical

techniques, the incidence of anastomotic fistula in colorectal

cancer surgery has not significantly decreased (14). Anastomotic fistulas can be caused

by various factors and are highly dependent on anastomotic blood

supply. Following inferior mesenteric artery ligation at its root

during radical resection of rectal carcinoma, the blood supply to

the residual distal intestine depends on the middle and inferior

rectal arteries (15). Blood

supply to the proximal colon is provided by the middle colic

artery, marginal arterial arcades or Riolan's arch (16,17).

If the marginal arterial arcades remain intact, the blood supply to

the descending colon is typically sufficient. It has been reported

that anastomotic fistulas may occur when blood flow is <70% of

normal levels, although the exact percentage required for reliable

intestinal healing remains elusive (18). Compared with postoperative

prevention and management, intraoperative real-time

evaluation of anastomotic perfusion is considered to be a more

reliable approach for preventing anastomotic fistulas (19). At present, intraoperative

assessment of blood supply to the anastomosis greatly relies on the

experience of the surgeon, which involves observing the degree of

intestinal peristalsis, colour, mesenteric fat appendage and

mesenteric arterial pulsation. In addition, surgeons may check for

active bleeding by cutting the marginal vessels or fat appendages.

However, this method is prone to errors. Previous reports revealed

that the sensitivity of subjective assessment is only 61.3%, with a

specificity of 88.5% (4). In obese

patients, wherein blood vessels are buried deep in the fat tissue

or in cases where the colon does not exhibit clear ischaemic

boundaries within a short time, it is challenging to accurately

evaluate blood supply (20).

Therefore, in rectal cancer surgery, accurately assessing blood

supply to the intestinal segments and anastomosis intraoperatively

whilst promptly modifying the surgical approach in cases of poor

blood supply may help reduce or prevent the occurrence of

anastomotic fistulas.

ICG fluorescence imaging is a simple and effective

method for real-time intraoperative visualisation. It is

primarily used clinically for tumor localisation, lymph node

tracing and tissue perfusion monitoring, for which it has been

proven to be safe and feasible (21). ICG is a non-radioactive

near-infrared imaging agent, meaning that no protective

measures are required during surgery (22). Considering that stained tissues are

not observable under visible light, ICG does not affect the

surgical field, prolong operative time or increase complexity

(23). In addition, ICG is a

cost-effective imaging agent. Despite all these advantages,

the use of ICG fluorescence imaging requires specialized

laparoscopic equipment, which may limit its widespread application.

After entering the bloodstream and reaching the target tissue, ICG

can be excited using lasers or light in the near-infrared

wavelength, emitting fluorescence within 1 min in regions with good

perfusion (24). This fluorescence

is then observed using a laparoscopic fluorescence imaging system.

During surgery, the Sherwinter scoring system can be used to

semi-quantitatively assess intestinal perfusion. In 2010,

Kudszus et al (25) were

the first to apply ICG fluorescence imaging in evaluating

anastomotic perfusion during colorectal cancer surgery, where the

results were positive. In another study by Ris et al

(26), ICG fluorescence imaging

was used in 30 patients during colorectal resection and

reconstruction, with successful imaging in 29 patients.

Specifically, ~35 sec after ICG injection, fluorescence appeared,

but no anastomotic fistula was observed postoperatively. A

meta-analysis by Blanco-Colino and

Espin-Basany (27), which

included 1,302 patients, concluded that the use of ICG

significantly reduced postoperative anastomotic fistula incidence

(ICG group vs. non-ICG group, 1.1 vs. 6.1%; P=0.02). In another

2020 Japanese multi-center retrospective study involving 422

patients with rectal cancer, where ICG fluorescence imaging was

used intraoperatively, surgical decisions were altered in 5.7%

patients owing to ICG imaging findings. This resulted in a ~6%

reduction in the rate of postoperative anastomotic fistulas, a

decrease in the reoperation rate and shortened hospital stays

(6).

Therefore, ICG fluorescence imaging is efficient and

precise in evaluating intestinal blood supply. This technique

eliminates the need for repeated intraoperative assessments,

significantly reducing operative time and accurately delineating

the resection margins, thereby minimising anastomotic complications

caused by poor perfusion. The core cost-effectiveness of ICG

fluorescence imaging is primarily attributed to its ability to

reduce complication risks. The single-use cost associated with ICG

is significantly lower compared with the expenses incurred from

treating postoperative complications (28). Traditional staining agents, such as

methylene blue and nano-carbon, exhibit various disadvantages,

including local adhesion issues, suboptimal visualization and even

the potential for abdominal cavity infections (29). Consequently, in comparison to

conventional staining techniques, ICG offers enhanced advantages in

terms of real-time performance, safety and accuracy in assessing

microcirculation. As a result, it has emerged as one of the most

cost-effective dynamic assessment tools for evaluating blood

perfusion. In the present study, two cases were observed in whom,

despite the proximal intestinal blood supply appearing normal under

white light, clear ischemia was determined under fluorescence

imaging. The accurate assessment provided by ICG fluorescence

imaging enabled the intraoperative resection of ischemic bowel

segments, preventing postoperative anastomotic ischemia and

fistulas. The ischemia in these two cases may have been due to poor

rotation of the descending colon, resulting in mesocolon thickening

and sigmoid colon adhesions. During surgery, mesocolon trimming may

have damaged the marginal artery, where ligating the inferior

mesenteric artery without preserving the left colic artery possibly

worsened the blood supply to the proximal colon. No obvious signs

of ischemia were detected during surgery. Without intraoperative

ICG fluorescence imaging, postoperative anastomotic fistulas due to

ischaemia may have occurred. If fluorescence intensity diminishes

during surgery, additional ICG can be administered intravenously to

enhance imaging quality. Although the present study did not include

a control group, the conclusions drawn are consistent with findings

from other studies, all of which suggest that ICG fluorescence

imaging can effectively assess the blood supply of anastomoses,

thereby reducing the incidence of postoperative anastomotic leakage

(30-32).

Inflammatory and nutritional biomarkers serve as

critical indicators for assessing the prognosis of patients with

colorectal cancer. Preoperative malnutrition and systemic

inflammatory status significantly impair the tissue repair capacity

and immune defence mechanisms of these patients, thereby elevating

the risk of poor anastomotic tissue healing post-surgery, which in

turn increases the incidence of anastomotic fistula (33). Once an anastomotic fistula occurs,

it triggers a severe local and systemic inflammatory response that

exacerbates catabolism and nutritional depletion within the body,

creating a vicious cycle that severely compromises both short-term

recovery and long-term oncological outcomes for patients (34). Consequently, close monitoring of

these inflammatory and nutritional biomarkers during the

perioperative period is invaluable for predicting the risk of

anastomotic fistula formation in addition to evaluating overall

prognosis. Shu et al (35)

previously indicated that low serum Ca2+ levels on the

first postoperative day are an independent risk factor affecting

overall survival and progression-free survival in patients with

colorectal cancer. Additionally, Li et al (36) previously identified that the

comprehensive immune-inflammation index can serve as a reliable

biomarker for prognostication in non-metastatic colorectal cancer

cases. The predictive scoring model developed from this index can

effectively forecast survival duration following surgery in

patients with non-metastatic colorectal cancer whilst aiding

clinical decision-making. Similar studies have further corroborated

the utility of both the comprehensive immune-inflammation index and

albumin-globulin ratio as dependable indicators for predicting

overall survival among patients with colorectal cancer. Notably,

elevated comprehensive immunoinflammatory indices coupled with a

reduced albumin-globulin ratio was found to be associated with

poorer prognostic outcomes (37).

A previous report has proposed a novel prognostic model, which

integrates the (neutrophils x platelets)/(lymphocytes x hemoglobin)

ratio along with the absolute monocyte count. This model

demonstrated superior predictive accuracy compared with that of

individual markers and exhibited high predictive performance for

1-, 3- and 5-year survival rates (38). Zhang et al (39) discovered that by assessing

preoperative serum nutritional biomarkers, such as the Onodera

Prognostic Nutritional Index and inflammatory indicators (such as

the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and platelet-to-lymphocyte

ratio), it was possible to effectively predict the risk of

anastomotic fistula in patients undergoing rectal cancer surgery.

Furthermore, the intraoperative application of ICG fluorescence

imaging technology allowed for the real-time assessment of

intestinal blood perfusion. This technique has been shown to reduce

the incidence of anastomotic fistulas, thereby minimizing this

serious complication and preventing subsequent inflammatory storms

and nutritional status deterioration triggered by such events.

Consequently, this approach significantly enhanced postoperative

recovery processes and improved long-term survival outcomes for

patients.

The present study has several limitations. The

inclusion of only 12 patients resulted in a limited sample size and

the potential biases were not sufficiently controlled for, which

somewhat reduced the statistical power. In addition, the present

study presented a single-group case series and did not include

comparisons with traditional intraoperative blood supply

assessments, making it challenging to fully demonstrate the

advantages of ICG technology. The postoperative follow-up period

was relatively short, preventing an evaluation of long-term

complications, where it remains unclear whether the short-term

benefits observed in the present study can be translated into

long-term outcomes. Therefore, supplementary follow-up is necessary

in subsequent stages. Future research will need to focus on

increasing the sample size, extending the follow-up duration,

establishing a randomized control group and initiating prospective

multi-center studies to clearly define endpoints and control for

various confounding factors or potential biases, thereby further

validating the findings of the present study.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that

ICG fluorescence imaging is safe, reliable and convenient for

evaluating intraoperative blood flow during laparoscopic surgery

for rectal cancer. This technique allowed the real-time

assessment of blood supply, reducing the risk of postoperative

anastomotic fistulas.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: This study was supported by the Fujian Provincial

Health and Youth Research Project (grant no. 2022QNA066) and the

Quanzhou Science and Technology Plan Project (grant no.

2021N034S).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study are included

in the figures and/or tables of this article.

Authors' contributions

CYW contributed to conceptualization, data curation,

funding acquisition, investigation, methodology and

writing-original draft. QMH contributed to data curation, funding

acquisition, methodology, software and writing-original draft

preparation. KY contributed to methodology and writing-review and

editing. CHX contributed to conceptualization, supervision and

writing-review and editing. All authors read and approved the final

manuscript. All authors checked and confirmed the authenticity of

the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of

the Second Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University.

Because of its retrospective nature, the requirement of informed

patient consent was waived.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Zimmermann MS, Wellner U, Laubert T,

Ellebrecht DB, Bruch HP, Keck T, Schlöricke E and Benecke CR:

Influence of anastomotic leak after elective colorectal cancer

resection on survival and local recurrence: A propensity score

analysis. Dis Colon Rectum. 62:286–293. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Nordholm-Carstensen A, Rolff HC and Krarup

PM: Differential impact of anastomotic leak in patients with stage

IV colonic or rectal cancer: A nationwide cohort study. Dis Colon

Rectum. 60:497–507. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Walz J, Burnett AL, Costello AJ, Eastham

JA, Graefen M, Guillonneau B, Menon M, Montorsi F, Myers RP, Rocco

B and Villers A: A critical analysis of the current knowledge of

surgical anatomy related to optimization of cancer control and

preservation of continence and erection in candidates for radical

prostatectomy. Eur Urol. 57:179–192. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Karliczek A, Harlaar NJ, Zeebregts CJ,

Wiggers T, Baas PC and van Dam GM: Surgeons lack predictive

accuracy for anastomotic leakage in gastrointestinal surgery. Int J

Colorectal Dis. 24:569–576. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Hamabe A, Ogino T, Tanida T, Noura S,

Morita S and Dono K: Indocyanine green fluorescence-guided

laparoscopic surgery, with omental appendices as fluorescent

markers for colorectal cancer resection: A pilot study. Surg

Endosc. 33:669–678. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Watanabe J, Ishibe A, Suwa Y, Suwa H, Ota

M, Kunisaki C and Endo I: Indocyanine green fluorescence imaging to

reduce the risk of anastomotic leakage in laparoscopic low anterior

resection for rectal cancer: A propensity score-matched cohort

study. Surg Endosc. 34:202–208. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Swamy MMM, Murai Y, Monde K, Tsuboi S and

Jin T: Shortwave-infrared fluorescent molecular imaging probes

based on π-conjugation extended indocyanine green. Bioconjug Chem.

32:1541–1547. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Gao C, Deng ZJ, Peng D, Jin YS, Ma Y, Li

YY, Zhu YK, Xi JZ, Tian J, Dai ZF, et al: Near-infrared dye-loaded

magnetic nanoparticles as photoacoustic contrast agent for enhanced

tumor imaging. Cancer Biol Med. 13:349–359. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Sherwinter DA, Gallagher J and Donkar T:

Intra-operative transanal near infrared imaging of colorectal

anastomotic perfusion: A feasibility study. Colorectal Dis.

15:91–96. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Megaritis D, Echevarria C and Vogiatzis I:

Respiratory and locomotor muscle blood flow measurements using

near-infrared spectroscopy and indocyanine green dye in health and

disease. Chron Respir Dis. 21(14799731241246802)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Shen Z, An Y, Shi Y, Yin M, Xie Q, Gao Z,

Jiang K, Wang S and Ye Y: The aortic calcification index is a risk

factor associated with anastomotic leakage after anterior resection

of rectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 21:1397–1404. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Ramphal W, Boeding JRE, Gobardhan PD,

Rutten HJT, de Winter LJMB, Crolla RMPH and Schreinemakers JMJ:

Oncologic outcome and recurrence rate following anastomotic leakage

after curative resection for colorectal cancer. Surg Oncol.

27:730–736. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Damen N, Spilsbury K, Levitt M, Makin G,

Salama P, Tan P, Penter C and Platell C: Anastomotic leaks in

colorectal surgery. ANZ J Surg. 84:763–768. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Paun BC, Cassie S, MacLean AR, Dixon E and

Buie WD: Postoperative complications following surgery for rectal

cancer. Ann Surg. 251:807–818. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Boxall TA, Smart PJ and Griffiths JD: The

blood-supply of the distal segment of the rectum in anterior

resection. BrJ Surg. 50:399–404. 1963.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Michels NA, Siddharth P, Komblith PL and

Parke WW: The variant blood supply to the descending colon,

rectosigmoid and rectum basedon 400 dissections. its importance in

regional resections: A review of medical literature. Dis Colon

Rectum. 8:251–278. 1965.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Nano M, Dal Corso H, Ferronato M, Solej M,

Hornung JP and Dei Poli M: Ligation of the inferior mesenteric

artery in the surgery of rectal cancer: Anatomical considerations.

Dig Surg. 21:123–127. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Shogan BD, Carlisle EM, Alverdy JC and

Umanskiy K: Do we really know why colorectal anastomoses leak? J

Gastrointest Surg. 17:1698–1707. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Huh YJ, Lee HJ, Kim TH, Choi YS, Park JH,

Son YG, Suh YS, Kong SH and Yang HK: Efficacy of assessing

intraoperative bowel perfusion with near-infrared camera in

laparoscopic gastric cancer surgery. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech

A. 29:476–483. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Spencer M, Unal R, Zhu B, Rasouli N,

McGehee RE Jr, Peterson CA and Kern PA: Adipose tissue

extracellular matrix and vascular abnormalities in obesity and

insulin resistance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 96:E1990–E1998.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Xi S, Zheng X and Wang X, Jiang B, Shen Z,

Wang G, Jiang Y, Fang X, Qian D, Muhammad DI and Wang X: Initial

application of fluorescence imaging for intraoperative localization

of small neuroendocrine tumors in the pancreas: Case report and

review of the literature. J Gastrointest Cancer.

56(23)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Sosnowska-Sienkiewicz P, Kowalewski G,

Garnier H, Wojtylko A, Murawski M, Szczygieł M, Al-Ameri M,

Czauderna P, Godzinski J, Kalicinski P and Mankowski P: Practical

guidelines for the use of indocyanine green in different branches

of pediatric surgery: A polish nationwide multi-center

retrospective cohort study. Health Sci Rep.

8(e70586)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Satoyoshi T, Okita K, Ishii M, Hamabe A,

Usui A, Akizuki E, Okuya K, Nishidate T, Yamano H, Nakase H and

Takemasa I: Timing of indocyanine green injection prior to

laparoscopic colorectal surgery for tumor localization: A

prospective case series. Surg Endosc. 35:763–769. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Martínek L, Pazdírek F, Hoch J and Kocián

P: Intra-operative fluorescence angiography of colorectal

anastomotic perfusion: A technical aspects. Rozhl Chir. 97:167–171.

2018.PubMed/NCBI(In Czech).

|

|

25

|

Kudszus S, Roesel C, Schachtrupp A and

Höer JJ: Intraoperative laser fluorescence angiography in

colorectal surgery: A noninvasive analysis to reduce the rate of

anastomotic leakage. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 395:1025–1030.

2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Ris F, Hompes R, Cunningham C, Lindsey I,

Guy R, Jones O, George B, Cahill RA and Mortensen NJ:

Near-infrared(NIR) perfusion angiography in minimally invasive

colorectal surgery. Surg Endosc. 28:2221–2226. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Blanco-Colino R and Espin-Basany E:

Intraoperative use of ICG fluorescence imaging to reduce the risk

of anastomotic leakage in colorectal surgery: A systematic review

and meta-analysis. Tech Coloproctol. 22:15–23. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Brackney CK, Pestana IA, Hoffler HL and

Blazek CD: Assessment of flap viability for complex transmetatarsal

amputation using indocyanine green fluorescent angiography: A case

study. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 112:20–198. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Lee YN, Moon JH and Choi HJ: Role of

image-enhanced endoscopy in pancreatobiliary diseases. Clin Endosc.

51:541–546. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

De Nardi P, Elmore U, Maggi G, Maggiore R,

Boni L, Cassinotti E, Fumagalli U, Gardani M, De Pascale S, Parise

P, et al: Intraoperative angiography with indocyanine green to

assess anastomosis perfusion in patients undergoing laparoscopic

colorectal resection: Results of a multicenter randomized

controlled trial. Surg Endosc. 34:53–60. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Jafari MD, Wexner SD, Martz JE, McLemore

EC, Margolin DA, Sherwinter DA, Lee SW, Senagore AJ, Phelan MJ and

Stamos MJ: Perfusion assessment in laparoscopic left-sided/anterior

resection (PILLAR II): A multi-institutional study. J Am Coll Surg.

220:82–92.e1. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Chan DKH, Lee SKF and Ang JJ: Indocyanine

green fluorescence angiography decreases the risk of colorectal

anastomotic leakage: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Surgery.

168:1128–1137. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Shi J, Wu Z, Li Z and Ji J: Roles of

macrophage subtypes in bowel anastomotic healing and anastomotic

leakage. J Immunol Res. 2018(6827237)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Foppa C, Ng SC, Montorsi M and Spinelli A:

Anastomotic leak in colorectal cancer patients: New insights and

perspectives. Eur J Surg Oncol. 46:943–954. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Shu Y, Li KJ, Sulayman S, Zhang ZY,

Ababaike S, Wang K, Zeng XY, Chen Y and Zhao ZL: Predictive value

of serum calcium ion level in patients with colorectal cancer: A

retrospective cohort study. World J Gastrointest Surg.

17(102638)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Li K, Zeng X, Zhang Z, Wang K, Pan Y, Wu

Z, Chen Y and Zhao Z: Pan-immune-inflammatory values predict

survival in patients after radical surgery for non-metastatic

colorectal cancer: A retrospective study. Oncol Lett.

29(197)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Li K, Chen Y, Zhang Z, Wang K, Sulayman S,

Zeng X, Ababaike S, Guan J and Zhao Z: Preoperative

pan-immuno-inflammatory values and albumin-to-globulin ratio

predict the prognosis of stage I-III colorectal cancer. Sci Rep.

15(11517)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Wang K, Li K, Zhang Z, Zeng X, Sulayman S,

Ababaike S, Wu Z, Pan Y, Chu J, Guan J, et al: Prognostic value of

combined NP and LHb index with absolute monocyte count in

colorectal cancer patients. Sci Rep. 15(8902)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Zhang ZY, Li KJ, Zeng XY, Wang K, Sulayman

S, Chen Y and Zhao ZL: Early prediction of anastomotic leakage

after rectal cancer surgery: Onodera prognostic nutritional index

combined with inflammation-related biomarkers. World J Gastrointest

Surg. 17(102862)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|