Introduction

Airway inflammation is a central feature in the

pathogenesis of respiratory diseases such as asthma, chronic

obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), bronchitis, and allergic

rhinitis, all of which contribute significantly to global morbidity

(1). Allergic asthma and rhinitis

alone affect approximately 300 million people worldwide, with

projections suggesting an additional 100 million cases by 2030 due

to escalating environmental exposures (2). Among various environmental triggers,

particulate matter (PM)-originating from both anthropogenic sources

(e.g., vehicle exhaust, industrial emissions) and natural phenomena

(e.g., wildfires, dust storms)-has emerged as a potent inducer of

airway inflammation and systemic injury (3,4).

Upon inhalation, PM can disrupt pulmonary

homeostasis by promoting allergen-specific immunoglobulin

production, complement activation, and recruitment of inflammatory

cells such as neutrophils, eosinophils, mast cells, and macrophages

(5,6). These immune responses contribute to

disease-specific pathologies, including bronchoconstriction and

airway hyperresponsiveness in asthma, mucus hypersecretion in

chronic bronchitis, and histamine-mediated nasal symptoms in

allergic rhinitis (7-9).

Although inhaled corticosteroids, leukotriene modifiers,

antihistamines, and bronchodilators can attenuate these

inflammatory pathways. However, their long-term use is often

limited by side effects such as mucosal dryness, drowsiness, and

high cost. Moreover, these treatments do not address the underlying

oxidative stress and cytokine-mediated tissue damage (10,11).

Given these limitations, there is growing interest in

phytochemicals that offer targeted anti-inflammatory action with

improved safety and affordability.

Natural products have gained increasing attention as

accessible, non-toxic alternatives to conventional therapies while

often offering comparable efficacy (12). Notably, combinations of natural

compounds frequently exhibit enhanced pharmacological activities

compared to a single agent (13).

Among these, Petasites japonicus (butterbur), a perennial

herb in the Asteraceae family, has long been used in East Asia for

its antipyretic, antitussive, and wound-healing properties and for

treating migraines, allergies, bronchial asthma, and

gastrointestinal ulcers (14).

Recent studies have further demonstrated butterbur's anti-tumor,

anti-allergic, anti-inflammatory, neuroprotective, and

anti-asthmatic effects (15).

Propolis is a natural substance used by bees to protect their

hives. It is an extract of a mixture of tree resin, honey, pollen,

and their own enzymes. Propolis is known to have a variety of

pharmacological properties, including antioxidant,

anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, wound healing, and

immunomodulatory effects (16-18).

However, the therapeutic potential of a P.

japonicus-propolis (PJP) mixture remains unexplored, especially

in the setting of PM10-induced airway inflammation.

Thus, this study aimed to evaluate the efficacy of

PJP extract in a mouse model of airway inflammation exacerbated by

particulate matter exposure. We focused on its ability to modulate

the IL-33/ST2/NF-κB signaling pathway. IL-33, an alarmin cytokine

released during cellular stress or damage, can bind to the ST2

receptor to activate NF-κB signaling, thereby driving the

production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines that

recruit immune cells to the airway (19). Our previous in vitro studies

demonstrated that a 1:1 mixture of P. japonicus and propolis

exhibited synergistic anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects in

particulate matter-exposed cell models (20,21).

Based on these findings, we sought to investigate whether this

synergistic effect would be replicated in vivo. By targeting

this axis, PJP might offer a novel, natural strategy for mitigating

environmentally induced airway inflammation.

Materials and methods

Reagents

Ovalbumin (OVA, A5503), particulate matter 10

(PM10, MRMCZ110), aluminum hydroxide (239186),

dexamethasone (Dex, D4902) and decalcifying solution (HS-105) were

sourced from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). H&E staining

kit (ab245880) and periodic acid-Schiff (PAS, ab150680),

Picro-Sirius Red stain kit (ab150681) and rabbit-specific HRP/DAB

detection IHC kit (ab64261) were obtained from Abcam (Cambridge,

UK). Toluidine blue O (198161) was sourced from Sigma-Aldrich (St.

Louis, MO, USA). Mouse IgE ELISA Kit (EMIGHE) and anti-ST2 antibody

(PA5-28383) were acquired from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Rockford,

IL, USA). Anti-Ovalbumin IgG1 (mouse) ELISA Kit Cayman (500830)

(Ann Arbor, MI, USA) and, IL-4 ELISA kits (M4000B) were sourced

from R&D system (Minneapolis, MN, USA). Histamine ELISA kit

(ENZ-KIT140A) was obtained from Enzo life sciences (Farmingdale,

NY, USA)., Donkey anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (31458) was

obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Rockford, IL, USA). Goat

anti-Mouse IgG(H+L)-HRP (SA001) was sourced from GenDEPOT (Katy,

TX, USA)., IL-33 (88513) was obtained from Cell Signaling (Danvers,

MA, USA)., NF-κB (sc-8008), p-NF-κB (sc-136548), and β-actin

(sc-8432) were acquired from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX,

USA).

Preparation of P. japonicus propolis

extract

In this study, P. japonicus was sourced from

(Jinan-gun, South Korea) and propolis powder was obtained from

Unique Biotech Co., Ltd. (Iksan-si, South Korea). Identification

and authentication of the plant were conducted by Professor

Hong-Jun Kim (College of Oriental Medicine, Woosuk University,

Jeonbuk, South Korea). A voucher specimen (#2024-02-01) was placed

in the Department of Health Management, College of Medical Science,

Jeonju University. P. japonicus samples were ground using a

blender and then extracted with 15 times their volume of 70%

ethanol at 50˚C under reflux for 6 hours. The resulting extract was

filtered through a cartridge filter using a Rotavapor R-210 (BUCHI

Labortechnik AG, Flawil, Switzerland). The filtered extract was

then concentrated using a vacuum rotary evaporator and subsequently

lyophilized with a freeze dryer. The P. japonicus extract

was then mixed with the propolis powder (1:1). The prepared sample

(PJP) was stored at -20˚C to maintain its stability until use.

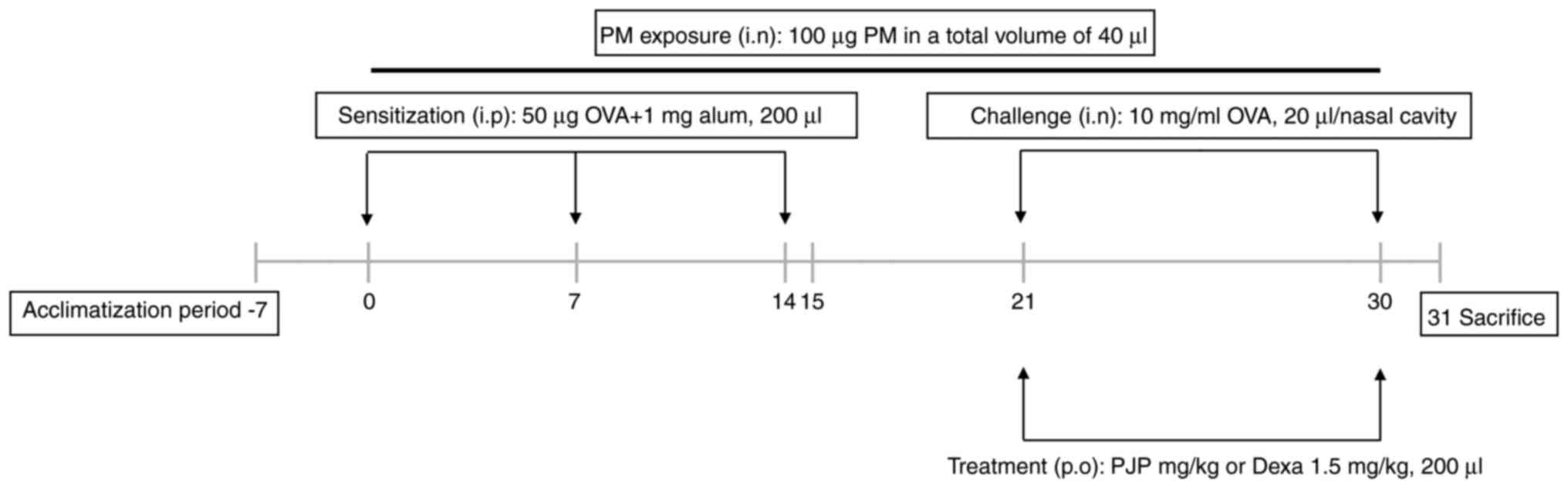

Animal studies and experimental

design

Animal studies were designed and conducted using

adult male BALB/c mice (6 weeks old, approximately 20 g) obtained

from Han-il Laboratory Animal Center (Wanju, South Korea). Mice

were housed under controlled environmental conditions (temperature:

22±2˚C, humidity: 50-60%, 12/12 h light/dark cycle) with ad libitum

access to a standard laboratory diet and water. The present study

was approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC)

of Jeonju University. The health status of each of the animals was

monitored daily. Humane experimental endpoints were established as

a 20% or greater loss of body weight, a decreased appetite for more

than two consecutive days, dyspnea, increased heart rate,

self-mutilation, jaundice, persistent diarrhea or vomiting, or a

decreased response to external stimuli. No animals reached these

endpoints, and no mortality or euthanasia occurred during the

study. Mice were acclimatized for one week before they were used

for experiments. The total duration of the animal experiment,

including the one-week acclimatization period and treatment

schedule, was 38 days. The sample size of six mice per group was

determined based on previous studies using

PM10/OVA-induced airway inflammation models (22), which commonly employ five to six

animals per group to detect biologically meaningful differences in

inflammatory markers with approximately 80% statistical power. This

number balances scientific rigor with ethical considerations

following the 3Rs principle (Reduction) to minimize animal use

while ensuring robust and reproducible results. While we

acknowledge that the limited sample size may affect statistical

power and generalizability, the current findings offer meaningful

preliminary insights. Future studies employing larger sample sizes

are planned to validate and expand upon these results. The

PM10/OVA-induced airway inflammation model used in this

study closely mimics key pathological features of human allergic

asthma, such as airway hyperresponsiveness, eosinophilic

inflammation, and mucus hypersecretion. After acclimation, mice

were randomly assigned to six groups, with each group consisting of

six mice. Group 1 (negative control group) was exposed to,

sensitized, treated, and challenged with saline. Group 2 (positive

control group) was exposed to 100 µg of PM10, sensitized

with 50 µg of OVA and 1 mg of alum and challenged with 10 mg/ml of

OVA, and treated with saline. Group 3 (PJP-50 group) was exposed to

100 µg of PM10, sensitized with 50 µg of OVA and 1 mg of

alum, challenged with 10 mg/ml of OVA, and treated with PJP at 50

mg/kg. Group 4 (PJP-100 group) was exposed to 100 µg of

PM10, sensitized with 50 µg of OVA and 1 mg of alum,

challenged with 10 mg/ml of OVA, and treated with PJP at 100 mg/kg.

Group 5 (PJP-200 group) was exposed to 100 µg of PM10,

sensitized with 50 µg of OVA and 1 mg of alum, challenged with 10

mg/ml of OVA, and treated with PJP at 200 mg/kg. Group 6

(dexamethasone group) was exposed to 100 µg of PM10,

sensitized with 50 µg of OVA and 1 mg of alum, challenged with 10

mg/ml of OVA, and treated with dexamethasone at 1.5 mg/kg. All test

compounds were administered via oral gavage. Groups 2-6 were

exposed to 100 µg PM10 in a total volume of 40 µl daily

via intranasal instillation and also sensitized on days 0, 7, and

14 with an intraperitoneal injection of 50 µg of OVA and 1 mg of

alum adjuvant solution. From day 15 to day 30, mice were treated

with either saline, 50-200 mg/kg PJP, or 1.5 mg/kg dexamethasone.

On days 21 and 30, all mice except those in the control group

received an intranasal challenge of 20 µl of OVA solution (10

mg/ml). On day 30, rubbing and sneezing were recorded for 15 min

for each mouse. Throughout the study, no noticeable adverse effects

related to PJP administration, such as body weight loss or reduced

appetite, were observed. Mice were sacrificed 24 h after the last

OVA challenge (day 31). Mice were deeply anesthetized with

inhalation of isoflurane at 2-6% for induction and maintained at

1-3% during sample collection. Euthanasia was performed by cervical

dislocation under deep anesthesia. Death was confirmed by the

absence of respiratory movement and heartbeat. Blood samples were

collected from their orbital venous plexus 24 h after the last OVA

challenge (day 31). Required mouse samples were then collected and

stored at -80˚C until use. A schematic of the experimental overview

is shown in Fig. 1.

Evaluation of nasal symptoms

After the final OVA challenge on day 30, each

mouse's behavior was recorded with a camera for 15 min to monitor

frequencies of nasal rubbing and sneezing. The scoring of sneezing

and nasal rubbing was performed by observers blinded to the

experimental groups to prevent bias.

Collection of serum, nasal lavage

fluid (NLF), and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF)

Serum, NLF, and BALF were collected using previously

established methods (23). At the

end of the experiment, mice were anesthetized with a 2-6%

isoflurane for induction and maintained at a 1-3% concentration.

Blood samples (600-800 µl per animal, collected once) were

collected from the orbital venous plexus. Subsequently, mice were

euthanized through cervical dislocation and, after confirming the

absence of respiratory and heartbeat, the trachea was opened, and 1

ml of sterile saline was injected into the nasal cavity using a

small tube to collect NLF. BALF was obtained by inserting an

18-gauge catheter into the partially exposed trachea and infusing 1

ml of saline, which was then gently aspirated. The collected fluid

was transferred to a microcentrifuge tube for centrifugation. The

supernatant obtained and serum were used for enzyme-linked

immunosorbent assays (ELISAs).

Histopathology

Nasal and lung tissues were collected immediately

after euthanasia on day 31. The tissues were carefully dissected

and rinsed with cold saline to remove blood prior to fixation.

Nasal and lung tissues were fixed in 10% formalin at 24±2˚C for

three days. Nasal tissues were then decalcified using a

decalcifying solution (HS-105) for histopathological examination.

After fixation, tissues were embedded in paraffin blocks and

sectioned at a thickness of 5 µm. The tissue sections were stained

with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), Sirius red, Toluidine blue

and periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) according to the manufacturer's

guidelines to analyze general morphology, goblet cell hyperplasia,

and mast cell infiltration. The severity of lung inflammation was

assessed using a five-point scoring system as previously described

(24): 0 for normal, 1 for a few

cells, 2 for a ring of cells one-cell-layer deep, 3 for a ring of

cells two-to four-cells deep, and 4 for a ring of cells deeper than

four-cells deep. Areas of PAS-positive regions were measured using

Fiji software.

Evaluation of immunoglobulin and

cytokines

Levels of OVA-specific IgE and OVA-specific IgG1 in

serum were quantified using commercial ELISA kits following the

manufacturer's instructions. Similarly, levels of IL-4 and

histamine in both NLF and BALF were measured using ELISA kits

according to the manufacturer's guidelines.

Immunohistochemistry

Nasal tissue samples were collected and fixed in 10%

formalin at 24±2˚C for three days. The nasal tissues were then

decalcified using a decalcifying solution for histopathological

examination. After fixation, the tissues were embedded in paraffin

blocks and sectioned at a thickness of 4.5 µm. These sections were

analyzed using a rabbit-specific HRP/DAB detection IHC kit.

Western blotting

Lung tissues were homogenized, sonicated, and lysed

using radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer. Protein quantification

was performed using the Bradford method, with bovine serum albumin

as the standard. Protein samples (50 µg) were separated by 10%

sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and

transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. These membranes

were then blocked with freshly prepared 5% skim milk at 22±2˚C for

1 h. Each membrane was subsequently incubated overnight on an

orbital shaker with a primary antibody specific to the target

protein. After washing, the membranes were incubated with a

secondary antibody for approximately 2 h at 22±2˚C. Signals were

detected and visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence

detection system (Alliance version 15.11; UVITEC). Bands were

analyzed using Image J software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as mean ± standard error of

the mean (SEM) (n=6). The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess the

normality of the data, and the results indicated that the data did

not meet the assumption of normality. Therefore, non-parametric

statistical analyses were performed. Group comparisons were

conducted using the Kruskal-Wallis test, followed by Dunn's

multiple comparison test for post hoc analysis. Statistical

analyses were performed using SPSS version 26.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY,

USA), and a P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically

significant.

Results

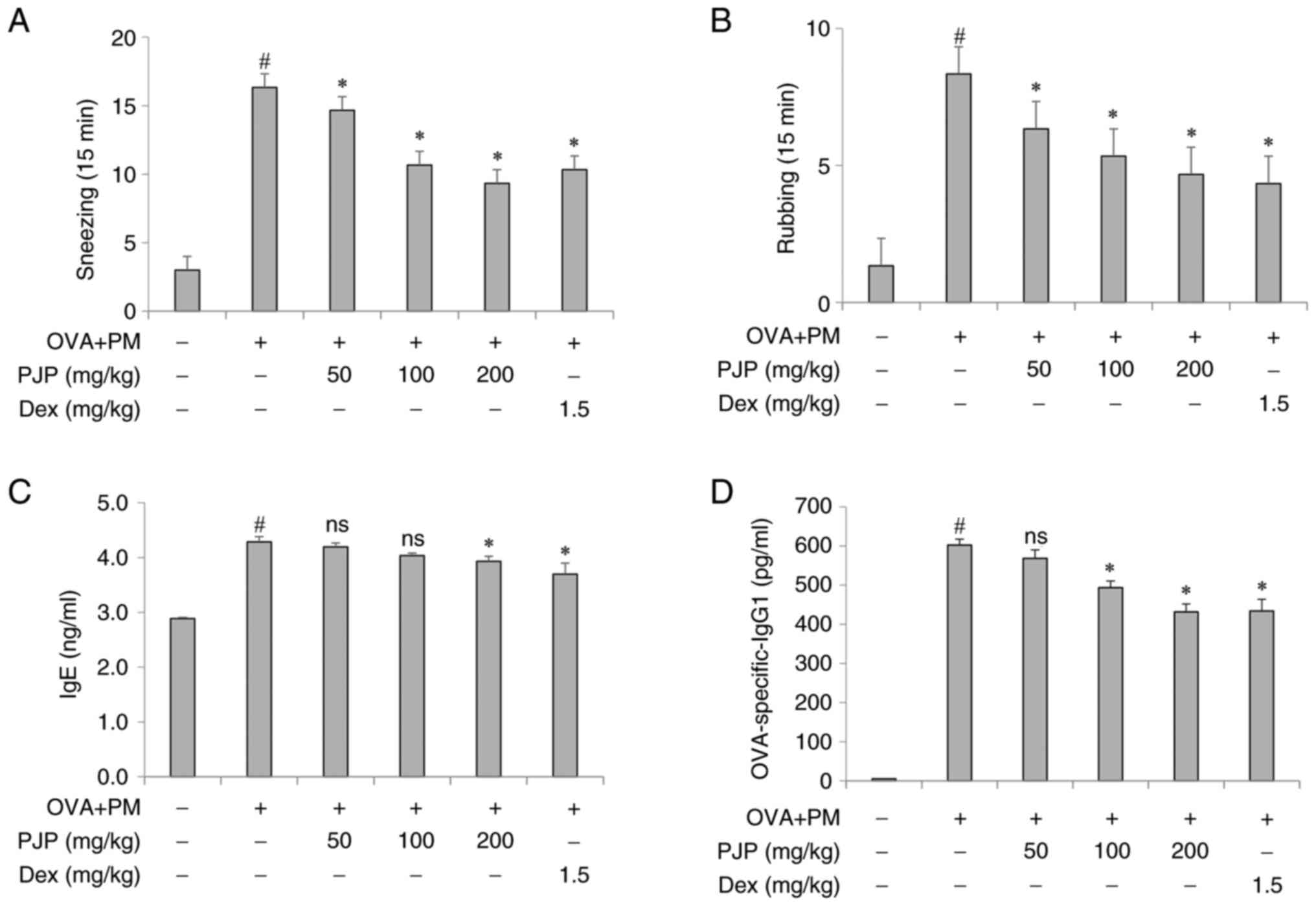

PJP reduces nasal symptoms of mice

with PM10/OVA-induced respiratory disease in mice

Exposure to PM10 and OVA throughout the

experimental period led to a significant increase in the frequency

of nasal rubbing and sneezing in mice of the positive control group

compared to the negative control group. However, treatment with PJP

at various doses resulted in a decrease in these symptoms. In

particular, mice administered PJP at 200 mg/kg exhibited

approximately a 42.9% reduction in sneezing and a 44.5% reduction

in nasal rubbing compared to the positive control group. These

effects were comparable to those observed in the

dexamethasone-treated group (1.5 mg/kg), with no significant

differences between the PJP 100 or 200 mg/kg groups and the

dexamethasone group (Fig. 2A and

B).

PJP reduces immunoglobulin levels in

serum of PM10/OVA-induced respiratory disease in

mice

Effects of PJP on immunoglobulin levels in mice with

respiratory disease were assessed. Exposure to PM10 and

OVA throughout the experimental period significantly increased

serum levels of OVA-specific IgE and IgG1 in the positive control

group compared to the negative control group. Administration of

various doses of PJP resulted in a decrease in these immunoglobulin

levels. In particular, mice administered 200 mg/kg of PJP showed

approximately 9.3 and 28.3% decrease in serum OVA-specific IgE and

IgG1 levels, respectively, compared to the positive control group.

There was no significant difference in these levels between mice

treated with PJP at 100 mg/kg or 200 mg/kg and those treated with

dexamethasone at 1.5 mg/kg (Fig.

2C and D).

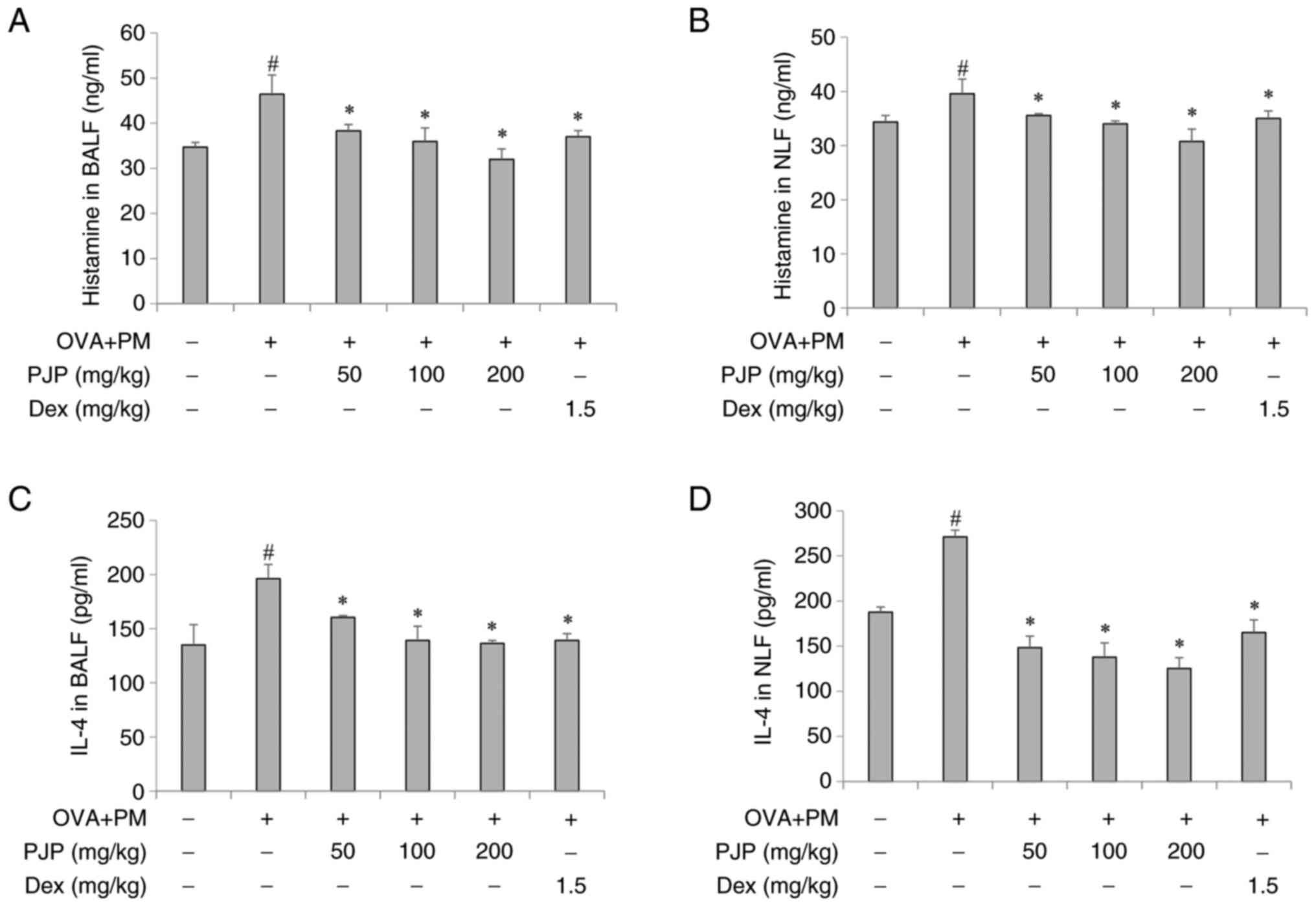

PJP reduces inflammatory mediators and

histamine release in BALF and NLF of PM10/OVA-induced

respiratory disease in mice

Effects of PJP on inflammatory mediators and

histamine release in BALF and NLF were investigated. Exposure to PM

and OVA throughout the experimental period significantly increased

levels of IL-4 and histamine in the BALF and NLF of the positive

control group compared to the negative control group. Treatment

with PJP at various doses resulted in a decrease in histamine

levels in both BALF and NLF, with significant reductions observed

at all doses. Interestingly, PJP at 200 mg/kg reduced histamine

release by approximately 31.3 and 22.4% in BALF and NLF, which was

more effective than the reduction achieved by dexamethasone at 1.5

mg/kg (Fig. 3A and B). In addition, PJP treatment

significantly decreased IL-4 secretion in both BALF and NLF. PJP at

200 mg/kg reduced IL-4 levels in BALF by approximately 30.4%

compared to the positive control group. Furthermore, in NLF, PJP at

200 mg/kg reduced IL-4 secretion by approximately 53.8% more than

the reduction observed with dexamethasone at 1.5 mg/kg (Fig. 3C and D).

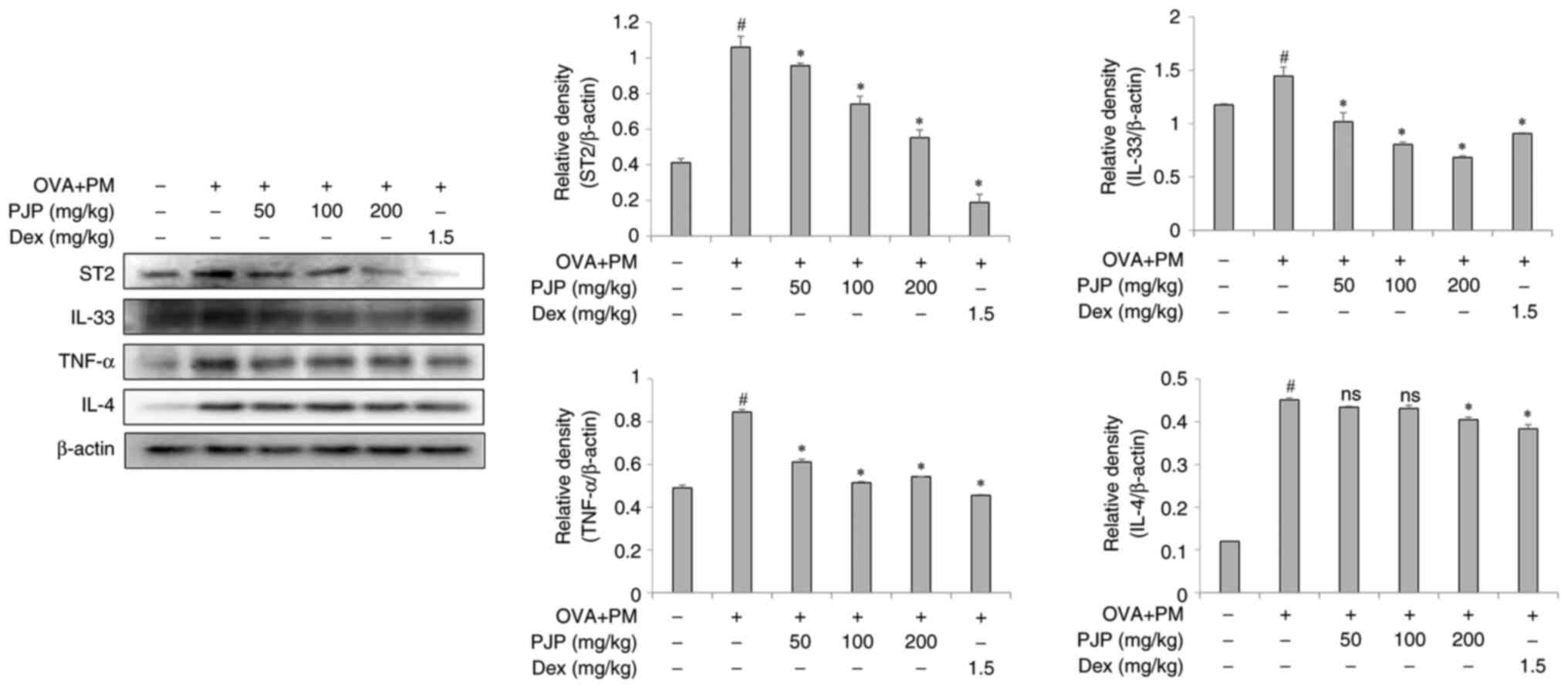

PJP reduces inflammatory mediators in

lung tissues of PM10/OVA-induced respiratory disease in

mice

Effects of PJP on inflammatory mediator expression

in lung tissues were examined. Exposure to PM10 and OVA

throughout the experimental period significantly increased the

expression of ST2, IL-33, TNF-α, and IL-4 in lung tissues of the

positive control group compared to the negative control group.

Treatment with various doses of PJP resulted in a reduction in the

expression of these mediators, with the greatest decreases observed

as follows: 52.8% for ST2, 45.7% for IL-33, 41.2% for TNF-α, and

11.1% for IL-4. These effects were comparable to those observed in

the dexamethasone-treated group (1.5 mg/kg) (Fig. 4).

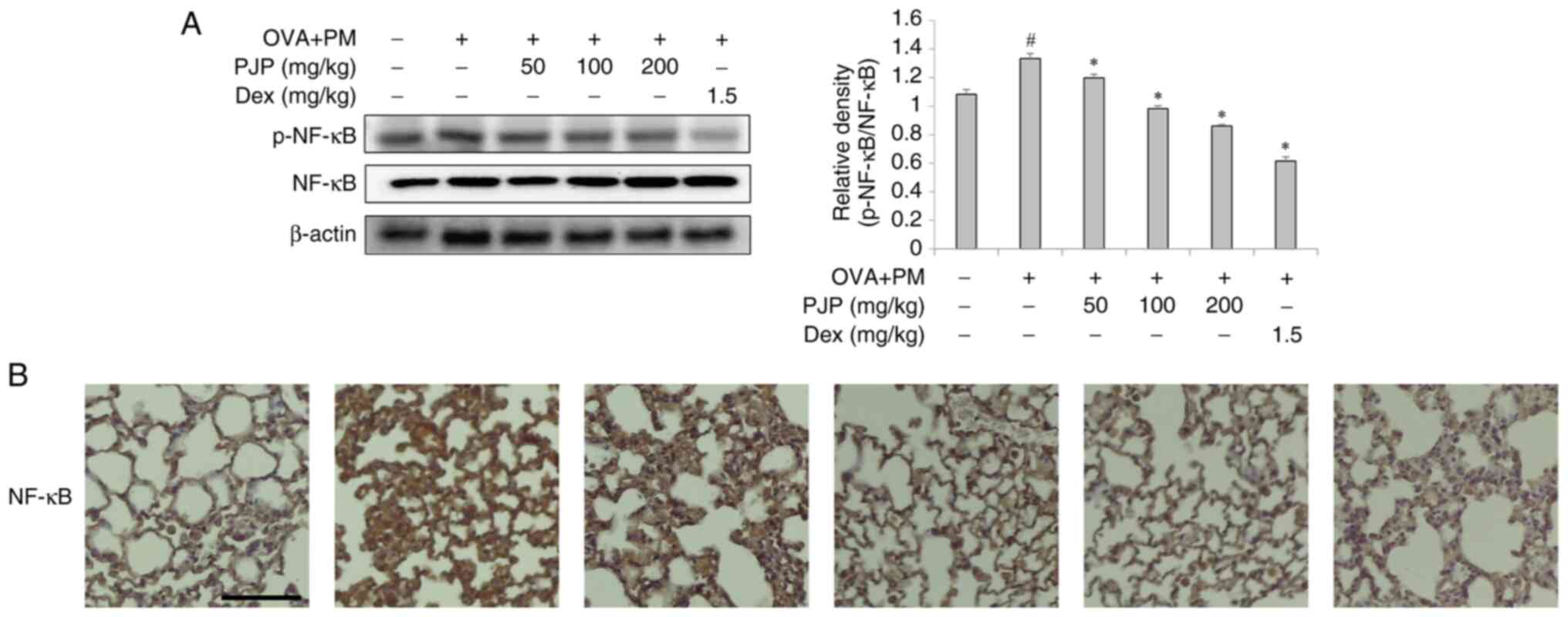

Effect of PJP on NF-κB signaling

pathway in lung tissues

Effects of PJP on activation of the MAPK/NF-κB

signaling pathway were analyzed. Both western blot and IHC analysis

of NF-κB phosphorylation in lung tissues revealed a significant

increase in p-NF-κB expression in the positive control group

compared to the negative control group. Treatment with various

doses of PJP decreased p-NF-κB expression compared to the positive

control group. Notably, PJP at 200 mg/kg reduced p-NF-κB expression

by approximately 35.3%. In addition, a significant difference was

observed between the PJP-treated group and the

dexamethasone-treated group (Fig.

5A and B).

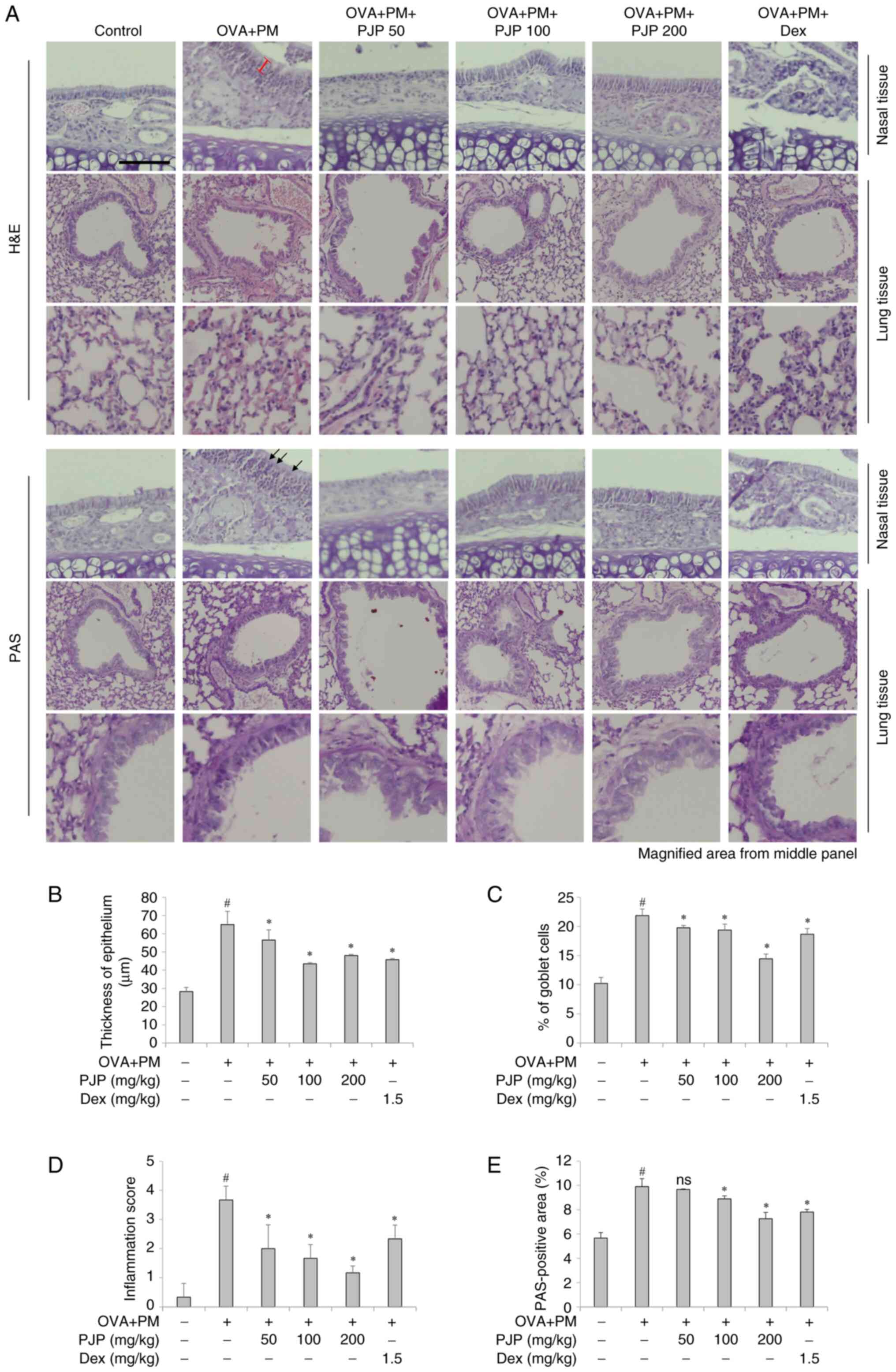

PJP ameliorates lung and nasal

histology in PM10/OVA-induced respiratory disease in

mice

Effects of PJP on the morphology and histology of

lung and nasal tissues were investigated. H&E staining revealed

that exposure to PM10 and OVA throughout the

experimental period significantly increased nasal mucosal thickness

in the positive control group compared to the negative control

group. Treatment with various doses of PJP resulted in a reduction

in epithelial thickness. Mice administered PJP exhibited a

significant decrease in epithelial thickness compared to the

positive control group. Notably, treatment with PJP at 100 mg/kg

reduced epithelial thickness by approximately 32.9%, and this

effect was not significantly different from that observed in the

dexamethasone-treated group (Fig.

6A and B). Additionally,

goblet cell hyperplasia was more pronounced in mice exposed to

PM10 and OVA compared to the negative control group.

However, the number of goblet cells was significantly reduced in

mice treated with PJP or dexamethasone compared to the positive

control group. In particular, PJP 200 mg/kg resulted in an

approximate 34.2% reduction in goblet cell numbers (Fig. 6C). Inflammatory cell infiltration

in lung tissues was also evaluated using H&E and PAS staining.

The inflammatory score was significantly higher in the

PM10/OVA-induced respiratory disease groups compared to

the control group. PJP supplementation significantly reduced the

inflammatory score compared to the positive control group.

Treatment with PJP at all doses significantly decreased the

inflammatory scores compared to the positive control group, with

the PJP 200 mg/kg showing an approximately 67.6% reduction in

inflammatory scores compared to the positive control group.

Notably, the anti-inflammatory effect observed in the PJP 200 mg/kg

group was greater than that observed in the dexamethasone-treated

group (Fig. 6D). Similarly, the

PAS-positive area was significantly higher in the

PM10/OVA-induced respiratory disease groups compared to

the negative control groups. PJP administration reduced the

PAS-positive area, indicating a decrease in mucus accumulation in

the airways. In particular, PJP at 200 mg/kg reduced the

PAS-positive area by approximately 26.3% compared to the positive

control group, demonstrating a comparable effect to dexamethasone

at 1.5 mg/kg (Fig. 6E).

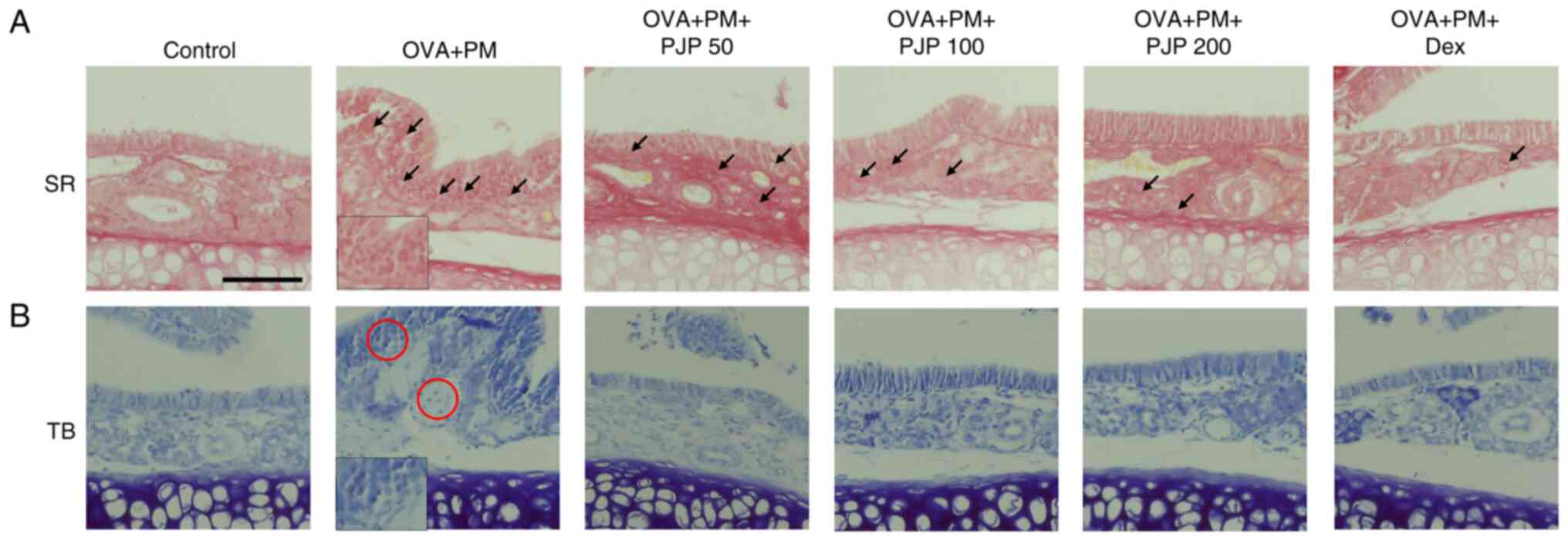

PJP reduces eosinophil and mast cell

infiltration in nasal tissues of PM10/OVA-induced

respiratory disease in mice

Effects of PJP on eosinophil and mast cell

infiltration in nasal tissues were investigated. Exposure to

PM10 and OVA throughout the experimental period

significantly increased eosinophil and mast cell infiltration in

nasal tissues of the positive control group compared to the

negative control group. This was demonstrated by Toluidine blue

staining of mast cells and Sirius red staining of eosinophils.

Treatment with PJP at various doses resulted in decreased

eosinophil and mast cell infiltration, with results similar to

those of the dexamethasone-treated group (Fig. 7A and B).

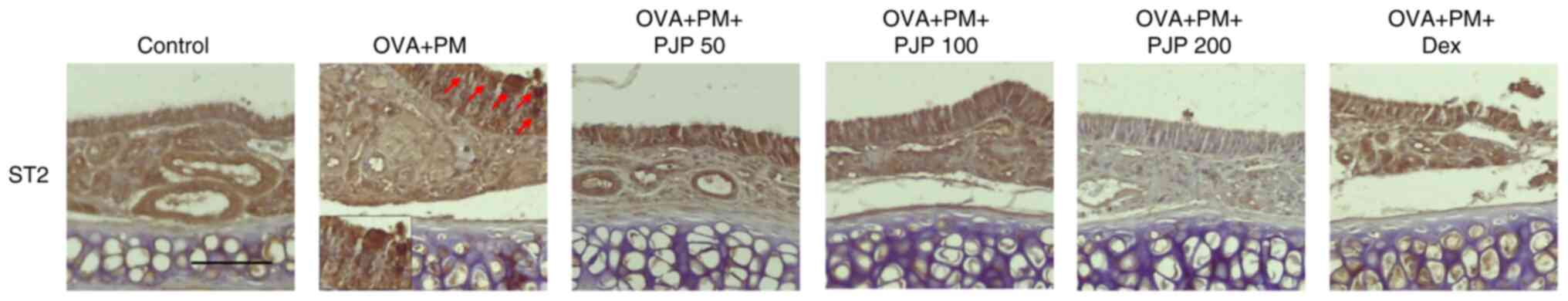

PJP reduces ST2 in nasal tissues of

PM10/OVA-induced respiratory disease in mice

ST2 expression in nasal tissues was evaluated using

IHC staining. Exposure to PM10 and OVA significantly

increased ST2 expression in nasal tissues of the positive control

group compared to the negative control group. Treatment with

various doses of PJP reduced ST2 expression, such, effects of PJP

were comparable to or more pronounced than those of dexamethasone

(Fig. 8).

Discussion

This study explored the effects of PM10

and OVA exposure on airway inflammation in a murine model of

allergic rhinitis and asthma, and evaluated the therapeutic

potential of PJP. Our findings demonstrated that PJP effectively

alleviated nasal symptoms, reduced immunoglobulin levels,

suppressed inflammatory mediators, and modulated key signaling

pathways involved in airway inflammation.

PM is a well-known exacerbating factor in

respiratory diseases, including asthma and allergic rhinitis

(3,25). PM exposure leads to increased

production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and recruitment of immune

cells such as mast cells, eosinophils, and macrophages, which

contribute to airway hyperresponsiveness and remodeling (26). Our PM10/OVA mouse model

successfully recapitulated these features, including enhanced nasal

rubbing, sneezing, epithelial thickening, goblet cell hyperplasia,

and elevated serum IgE and IgG1 levels, consistent with previous

reports using similar models (27,28).

The observed reduction of nasal symptoms and

immunoglobulin levels by PJP aligns with studies showing that

natural plant extracts and propolis components can modulate

allergic inflammation by regulating IgE-mediated responses and

immune cell activation (29,30).

Notably, PJP administration significantly decreased serum

OVA-specific IgG1 and IgE, which are critical in mast cell

sensitization and histamine release, thereby directly linking the

observed symptom relief to underlying immunomodulatory effects.

Furthermore, our results showed that PJP treatment

reduced levels of IL-4 and histamine in both BALF and NLF. IL-4 is

a central cytokine in Th2-mediated allergic responses that promotes

IgE class switching and mast cell recruitment (31,32).

The suppression of IL-4 and histamine release suggests that PJP

modulates the Th2 immune axis, a mechanism corroborated by previous

studies where propolis extracts inhibited Th2 cytokines and

associated inflammation (33).

Importantly, PJP's inhibitory effect on histamine release was more

pronounced than that of dexamethasone, highlighting its potent

anti-allergic properties.

In addition to Th2 cytokines, TNF-α and the

IL-33/ST2 axis are critical mediators of airway inflammation. TNF-α

amplifies allergic inflammation by enhancing Th2 cell migration and

cytokine production (34,35). The IL-33/ST2 pathway activates

downstream ERK1/2 signaling, leading to inflammatory gene

expression and recruitment of innate lymphoid cells (19,36).

PJP's ability to significantly downregulate TNF-α, IL-33, and ST2

expression underscores its broad-spectrum anti-inflammatory

potential, targeting multiple pathways implicated in allergic

airway disease pathogenesis.

The suppression of NF-κB phosphorylation in lung

tissues by PJP provides further insight into its mechanism of

action. NF-κB is a master regulator of inflammatory gene

transcription, and its activation is a hallmark of PM-induced

airway inflammation (37). By

inhibiting NF-κB activation, PJP may prevent the transcription of

pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, thereby reducing immune

cell recruitment and inflammation. This molecular mechanism is

consistent with reports that P. japonicus and propolis

components can modulate NF-κB signaling in various inflammatory

models (38,39).

Histologically, PJP improved airway remodeling, as

evidenced by reduced epithelial thickness, goblet cell hyperplasia,

and inflammatory cell infiltration. These morphological

improvements are critical because chronic airway remodeling

contributes to disease severity and resistance to conventional

therapies (40). The notable

reduction in eosinophil and mast cell infiltration in nasal tissues

further validates PJP's anti-inflammatory efficacy.

In addition, to clarify whether the observed

cytokine-inhibitory effects are attributable solely to Petasites

japonicus, propolis, or their combination, our previous in

vitro studies using NCI-H292 lung epithelial cells and RAW264.7

macrophages demonstrated that the PJP mixture significantly

suppressed inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α), restored

antioxidant enzyme levels (SOD, catalase, glutathione), and

inhibited NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways under PM stimulation

(20,21). These findings suggest that both

Petasites japonicus and propolis individually exert

anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects, but their combination

enhances these actions through potential synergistic mechanisms.

Although the current in vivo study did not include groups

treated with individual extracts, our prior in vitro data

support the hypothesis that each component contributes to the

overall efficacy of PJP. Future studies should include single

extract control groups to further delineate the individual and

combined effects of each component in vivo.

Despite these promising results, there are

limitations to consider. The study used an acute animal model, and

the long-term effects and safety profile of PJP remain to be

established. Moreover, the exact bioactive compounds responsible

for these therapeutic effects require further identification and

characterization. Future studies should also explore the

pharmacokinetics and potential synergistic effects of PJP

constituents, as well as validate these findings in clinical

trials. Additionally, the PJP used in this study lacked

standardization and quantification of key active compounds such as

petasin, flavonoids, and CAPE, which may affect reproducibility.

Although our previous in vitro studies confirmed

anti-inflammatory effects of each component, the present in

vivo study did not include propolis-only or P.

japonicus-only groups, limiting the ability to distinguish

their individual effects in vivo. Furthermore, while we

focused on NF-κB signaling, additional analysis of pathways such as

MAPK and ERK1/2 is needed to fully elucidate the therapeutic

mechanisms. Future studies will address these limitations.

In summary, our study demonstrates that PJP

mitigates PM10/OVA-induced airway inflammation through

modulation of immunoglobulin production, suppression of Th2

cytokines, inhibition of NF-κB signaling, and reduction of

inflammatory cell infiltration and airway remodeling. These

findings support the potential of PJP as a natural therapeutic

agent for allergic respiratory diseases exacerbated by air

pollution. Further research is warranted to fully elucidate its

mechanisms and clinical applicability.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: This work was supported by the Technology Development

Program (grant no. S3403654) funded by the Ministry of SMEs and

Startups (MSS, Korea).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

JHP and JYS made major contributions to the study

design and manuscript writing, and made substantial contributions

to the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data. DNC

contributed to data interpretation, manuscript review, editing,

drafting and validation. MYK contributed to methodology development

and data visualization, and assisted with data analysis. YKH

provided essential resources, performed formal data analysis and

contributed to data interpretation. GSS contributed to data

visualization, assisted in data interpretation and performed

validation. BOC contributed to supervision, project administration

and study conceptualization. SIJ contributed to supervision,

project administration, study conceptualization and funding

acquisition. JHP and SIJ confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data. All authors have read and approved the final version of the

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by Jeonju University

Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (approval no.

jjIACUC-20230602-2022-0505-A1; Jeonju, South Korea).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

JHP, MYK and YKH are affiliated with Unique Biotech

Co., Ltd., which provided the propolis powder used in the present

study. The other authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Jeffery PK and Haahtela T: Allergic

rhinitis and asthma: Inflammation in a one-airway condition. BMC

Pulm Med. 6 (Suppl 1)(S5)2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Dharmage SC, Perret JL and Custovic A:

Epidemiology of asthma in children and adults. Front Pediatr.

7(246)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Ramli NA, Md Yusof NFF, Shith S and Suroto

A: Chemical and biological compositions associated with ambient

respirable particulate matter: A review. Water Air Soil Pollut.

231(120)2020.

|

|

4

|

Bauer RN, Diaz-Sanchez D and Jaspers I:

Effects of air pollutants on innate immunity: The role of Toll-like

receptors and nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like

receptors. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 129:14–26. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Cao TBT, Quoc QL, Jang JH and Park HS:

Immune cell-mediated autoimmune responses in severe asthma. Yonsei

Med J. 65:194–201. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Karagiannis SN, Karagiannis P, Josephs DH,

Saul L, Gilbert AE, Upton N and Gould HJ: Immunoglobulin E and

allergy: Antibodies in immune inflammation and treatment. Microbiol

Spectr. 1:2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Galli SJ, Tsai M and Piliponsky AM: The

development of allergic inflammation. Nature. 454:445–454.

2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Yamauchi K and Ogasawara M: The role of

histamine in the pathophysiology of asthma and the clinical

efficacy of antihistamines in asthma therapy. Int J Mol Sci.

20(1733)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Costanzo G, Costanzo GAML, Del Moro L,

Nappi E, Pelaia C, Puggioni F, Canonica GW, Heffler E and Paoletti

G: Mast cells in upper and lower airway diseases: Sentinels in the

front line. Int J Mol Sci. 24(9771)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Wise SK, Lin SY, Toskala E, Orlandi RR,

Akdis CA, Alt JA, Azar A, Baroody FM, Bachert C, Canonica GW, et

al: International consensus statement on allergy and rhinology:

Allergic rhinitis. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 8:108–352.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Pascual RM and Peters SP: The irreversible

component of persistent asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol.

124:883–892. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Dzobo K: The role of natural products as

sources of therapeutic agents for innovative drug discovery. In:

Comprehensive Pharmacology. Kenakin T (ed). Elsevier, pp408-422,

2022.

|

|

13

|

Yang WJ, Li DP, Li JK, Li MH, Chen YL and

Zhang PZ: Synergistic antioxidant activities of eight traditional

Chinese herb pairs. Biol Pharm Bull. 32:1021–1026. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Hiemori-Kondo M: Antioxidant compounds of

Petasites japonicus and their preventive effects in chronic

diseases: A review. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 67:10–18. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Kim EJ, Jung JI, Jeon YE and Lee HS:

Aqueous extract of Petasites japonicus leaves promotes

osteoblast differentiation via up-regulation of Runx2 and Osterix

in MC3T3-E1 cells. Nutr Res Pract. 15:579–590. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Acito M, Varfaj I, Brighenti V, Cengiz EC,

Rondini T, Fatigoni C, Russo C, Pietrella D, Pellati F, Bartolini

D, et al: A novel black poplar propolis extract with promising

health-promoting properties: Focus on its chemical composition,

antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-genotoxic activities. Food

Funct. 15:4983–4999. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Bhatti N, Hajam YA, Mushtaq S, Kaur L,

Kumar R and Rai S: A review on dynamic pharmacological potency and

multifaceted biological activities of propolis. Discov Sustain.

5(185)2024.

|

|

18

|

Valverde TM, Soares BNGDS, Nascimento AMD,

Andrade ÂL, Sousa LRD, Vieira PMA, Santos VR, Seibert JB, Almeida

TCS, Rodrigues CF, et al: Anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial,

antioxidant and photoprotective investigation of red propolis

extract as sunscreen formulation in polawax cream. Int J Mol Sci.

24(5112)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Griesenauer B and Paczesny S: The

ST2/IL-33 axis in immune cells during inflammatory diseases. Front

Immunol. 8(475)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Kang ES, Jeong SY, Cho BO, Shin JY, Kim

MY, Hur YK and Jang SI: Propolis and Petasites japonicus

leaf extract mixture attenuates PM2.5-induced inflammation in

NCI-H292 lung epithelial cells. Korean J Food Sci Technol.

56:458–464. 2024.

|

|

21

|

Kang ES, Shin JY, Jeong SY, Cho BO, Kim

MY, Hur YK and Jang SI: Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effect of

Petasites japonicus leaf and propolis extract mixture in

RAW264.7 cells exposed to PM2.5. Korean J Food Sci Technol.

56:556–563. 2024.

|

|

22

|

Han H, Oh EY, Lee JH, Park JW and Park HJ:

Effects of particulate matter 10 inhalation on lung tissue RNA

expression in a murine model. Tuberc Respir Dis (Seoul). 84:55–66.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Hofmann Bowman MA, Heydemann A, Gawdzik J,

Shilling RA and Camoretti-Mercado B: Transgenic expression of human

S100A12 induces structural airway abnormalities and limited lung

inflammation in a mouse model of allergic inflammation. Clin Exp

Allergy. 41:878–889. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Tighe RM, Birukova A, Yaeger MJ, Reece SW

and Gowdy KM: Euthanasia-and lavage-mediated effects on

bronchoalveolar measures of lung injury and inflammation. Am J

Respir Cell Mol Biol. 59:257–266. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Tiotiu AI, Novakova P, Nedeva D,

Chong-Neto HJ, Novakova S, Steiropoulos P and Kowal K: Impact of

air pollution on asthma outcomes. Int J Environ Res Public Health.

17(6212)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Liu K, Hua S and Song L: PM2.5 exposure

and asthma development: The key role of oxidative stress. Oxid Med

Cell Longev. 2022(3618806)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Pang L, Yu P, Liu X, Fan Y, Shi Y and Zou

S: Fine particulate matter induces airway inflammation by

disturbing the balance between Th1/Th2 and regulation of GATA3 and

Runx3 expression in BALB/c mice. Mol Med Rep.

23(378)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Marín-Palma D, Tabares-Guevara JH, Taborda

N, Rugeles MT and Hernandez JC: Coarse particulate matter (PM10)

induce an inflammatory response through the NLRP3 activation. J

Inflamm Lond Engl. 21(15)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Igarashi G, Segawa T, Akiyama N, Nishino

T, Ito T, Tachimoto H and Urashima M: Efficacy of Brazilian

propolis supplementation for Japanese lactating women for atopic

sensitization and nonspecific symptoms in their offspring: A

randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Evid Based

Complement Alternat Med. 2019(8647205)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Azman S, Sekar M, Bonam SR, Gan SH,

Wahidin S, Lum PT and Dhadde SB: Traditional medicinal plants

conferring protection against ovalbumin-induced asthma in

experimental animals: A review. J Asthma Allergy. 14:641–662.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Bao K and Reinhardt RL: The differential

expression of IL-4 and IL-13 and its impact on type-2 immunity.

Cytokine. 75:25–37. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Haas H, Falcone FH, Holland MJ, Schramm G,

Haisch K, Gibbs BF, Bufe A and Schlaak M: Early interleukin-4: Its

role in the switch towards a Th2 response and IgE-mediated allergy.

Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 119:86–94. 1999.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Missima F, Pagliarone AC, Orsatti CL,

Araújo JP Jr and Sforcin JM: The effect of propolis on Th1/Th2

cytokine expression and production by melanoma-bearing mice

submitted to stress. Phytother Res. 24:1501–1507. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Iwasaki M, Saito K, Takemura M, Sekikawa

K, Fujii H, Yamada Y, Wada H, Mizuta K, Seishima M and Ito Y:

TNF-alpha contributes to the development of allergic rhinitis in

mice. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 112:134–140. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Jang DI, Lee AH, Shin HY, Song HR, Park

JH, Kang TB, Lee SR and Yang SH: The role of tumor necrosis factor

Alpha (TNF-α) in autoimmune disease and current TNF-α inhibitors in

therapeutics. Int J Mol Sci. 22(2719)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Ding W, Zou GL, Zhang W, Lai XN, Chen HW

and Xiong LX: Interleukin-33: Its emerging role in allergic

diseases. Molecules. 23(1665)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Wang J, Huang J, Wang L, Chen C, Yang D,

Jin M, Bai C and Song Y: Urban particulate matter triggers lung

inflammation via the ROS-MAPK-NF-κB signaling pathway. J Thorac

Dis. 9:4398–4412. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Eo H, Lee S, Kim SH, Ju IG, Huh E, Lim J,

Park S and Oh MS: Petasites japonicus leaf extract inhibits

Alzheimer's-like pathology through suppression of

neuroinflammation. Food Funct. 13:10811–10822. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Búfalo MC, Ferreira I, Costa G, Francisco

V, Liberal J, Cruz MT, Lopes MC, Batista MT and Sforcin JM:

Propolis and its constituent caffeic acid suppress LPS-stimulated

pro-inflammatory response by blocking NF-κB and MAPK activation in

macrophages. J Ethnopharmacol. 149:84–92. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Hough KP, Curtiss ML, Blain TJ, Liu RM,

Trevor J, Deshane JS and Thannickal VJ: Airway remodeling in

asthma. Front Med (Lausanne). 7(191)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|