Introduction

Solid pseudopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas (SPN)

is a rare low-grade malignant tumor, accounting for ~0.2-2.7% of

all pancreatic neoplasms (1-3).

As morphological and pathological studies on SPN have advanced in

both domestic and international research settings, the lesion has

been referred to using several different names, including

pancreatic papillary-solid tumor, pancreatic papillary-cystic

tumor, pancreatic cystic-solid tumor and pancreatic cystic-solid

papillary acinar cell tumor (4-6).

In 1996, the World Health Organization (WHO) officially designated

SPN based on its characteristic solid pseudopapillary architecture

and classified it as a borderline malignant tumor with

indeterminate biological behavior (7). By 2010, the WHO further defined SPN

as a low-grade malignant neoplasm (8). SPN predominantly occurs in young

females and its clinical presentation is typically nonspecific.

Preoperative diagnosis primarily depends on imaging modalities such

as computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Complete surgical resection remains the treatment of choice. The

postoperative prognosis for SPN is generally favorable, with the

reported 5-year survival rate exceeding 95% (1).

Case report

The patient was a 20-year-old female with no

significant clinical symptoms. A mass in the pancreatic tail was

incidentally detected during a routine physical examination and the

patient was subsequently admitted to Xingtai People's Hospital

(Xingtai, China) in March 2025 for further evaluation and

management. The patient's laboratory findings, including complete

blood count, cytokine analysis, comprehensive biochemical assays,

neutrophil apolipoprotein measurement and thymidine kinase 1

testing, demonstrated no clinically significant abnormalities.

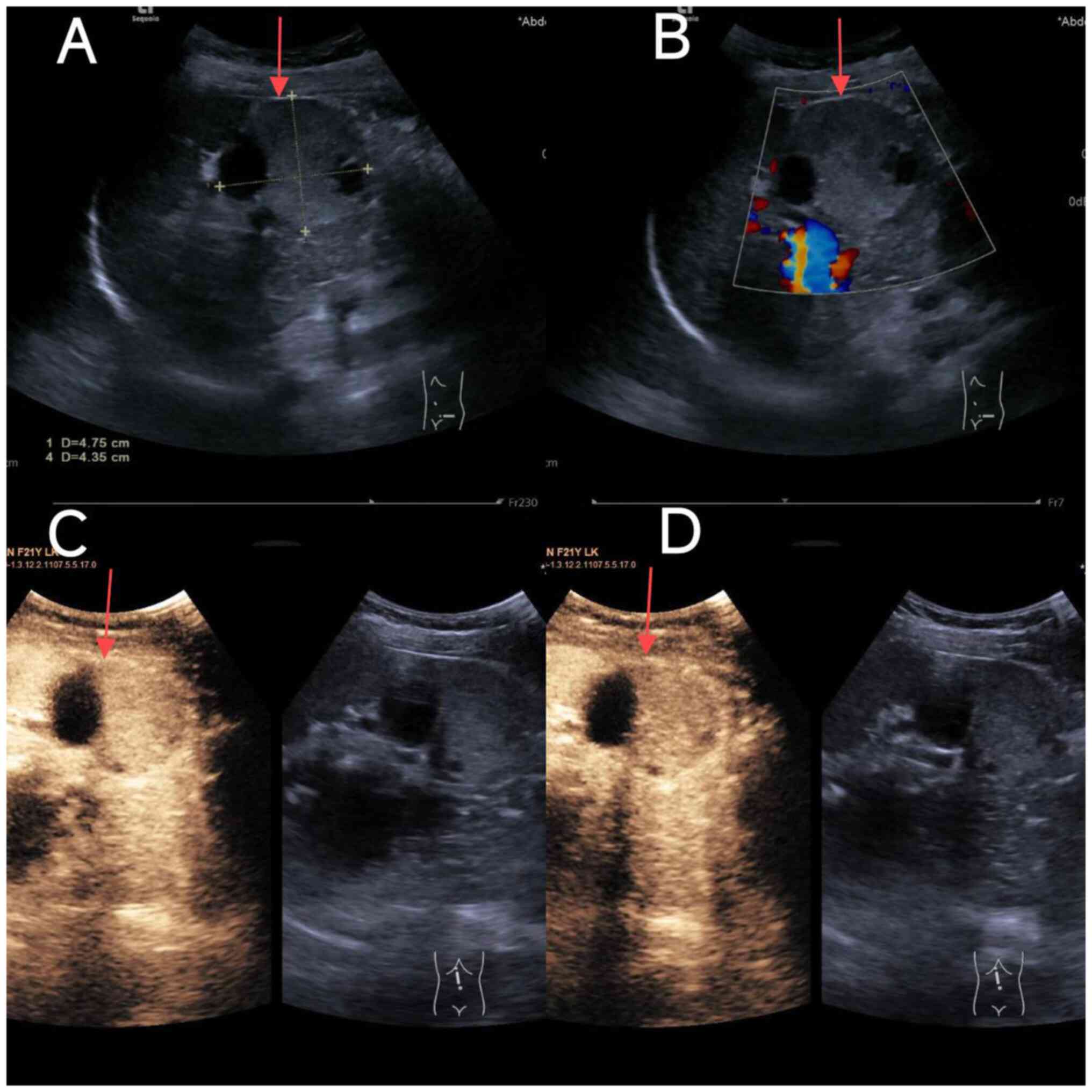

Conventional ultrasound demonstrated an irregularly shaped,

well-circumscribed cystic-solid lesion measuring ~48x44 mm in the

tail of the pancreas (Fig. 1A).

Color Doppler flow imaging revealed no detectable blood flow within

the lesion (Fig. 1B).

Contrast-enhanced ultrasound showed synchronous enhancement between

the lesion and the pancreas beginning at 10 sec, characterized by

heterogeneous moderate enhancement with visible non-enhancing

areas, followed by persistent hypo-enhancement (Fig. 1C and D). The ultrasound diagnosis indicated a

cystic-solid mass in the pancreatic tail, likely benign and of

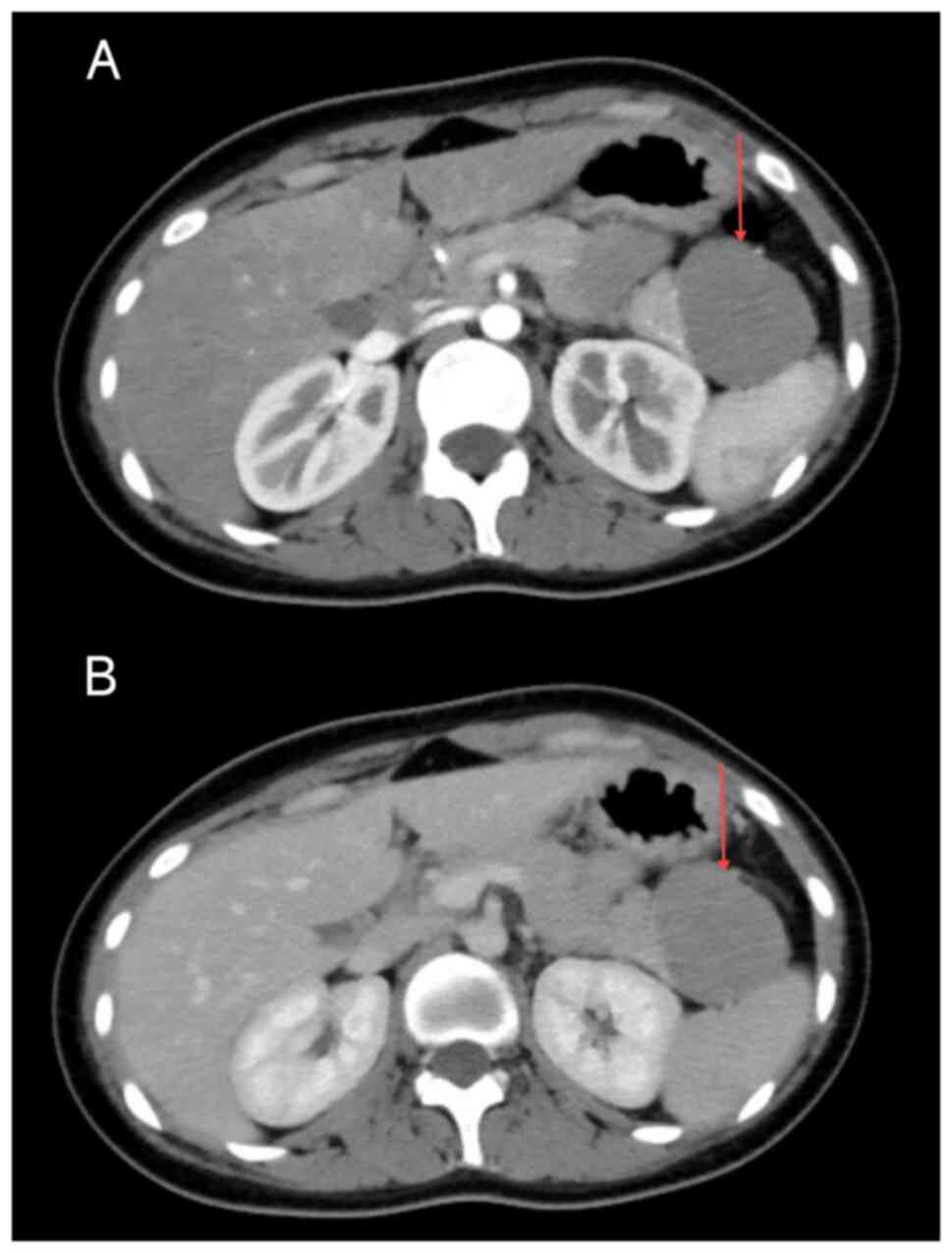

pancreatic origin, with SPN not entirely excluded. Enhanced CT scan

revealed an irregular mass measuring ~49x42 mm in the pancreatic

tail, showing CT attenuation values of 28-55 HU in the arterial

phase (Fig. 2A) and 36-68 HU in

the venous phase (Fig. 2B). The

lesion exhibited gradual mild enhancement, with visible

calcifications and internal septations, as well as an intact

capsule and well-defined margins. Radiological diagnosis suggested

a space-occupying lesion in the pancreatic tail, with SPN being a

probable diagnosis. Given the definitive diagnosis and absence of

comorbid conditions, tumor marker testing was not performed.

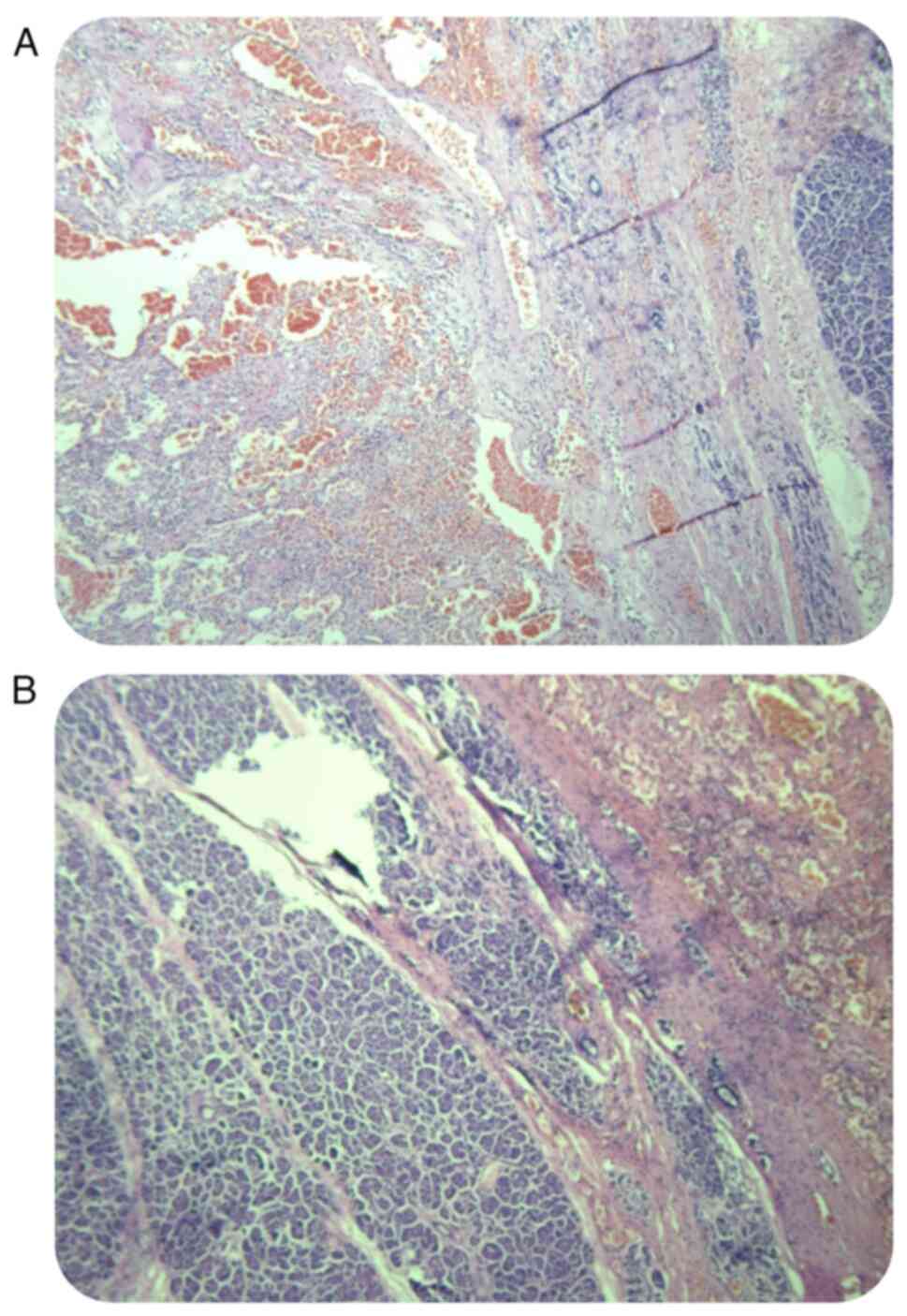

Following complete surgical resection, histopathological analyses

confirmed the diagnosis of SPN with focal cystic degeneration and

hemorrhage (Fig. 3A and B). H&E staining was performed as

follows: The tumor tissues were fixed in 10% formalin for >24 h

at 25˚C (Beijing BioDee Biotechnology Co., Ltd.), followed by

gradient alcohol dehydration and embedding in paraffin.

Subsequently, 3-µm thick sections were prepared and stained with

H&E. The ICD-10 classification code for this disease is

D37.700x003(7). According to the

ICD-10 classification system, borderline tumors are assigned codes

within the range D37 to D48. Within this range, codes D37 to D44

are used for tumors categorized as ‘uncertain malignant potential’

(dynamic undetermined), whereas codes D45 to D48 are assigned to

tumors classified as ‘unspecified behavior’ (dynamic unknown). The

specific ICD-10 code for borderline pancreatic tumors is D37.7,

which is classified under the category ‘tumors of other digestive

organs, uncertain malignant potential or unspecified behavior’. The

patient completed the initial follow-up examination within one

month following surgery, with clinical observations confirming

satisfactory wound healing and the restoration of normal

gastrointestinal function. Subsequent follow-up evaluations should

be performed at regular intervals of 3 to 6 months. Postoperative

follow-up demonstrated no abnormal abdominal masses or symptoms and

enhanced CT imaging revealed no radiological evidence of tumor

recurrence or metastasis. It is essential to closely monitor the

patient's psychological condition and provide timely psychological

counseling and support to alleviate negative emotions, such as

anxiety and depression. Simultaneously, the patient should be

encouraged to maintain a positive and optimistic outlook in order

to strengthen their confidence in the recovery process.

Discussion

SPN is a rare low-grade malignant tumor

characterized by solid and pseudopapillary architectural features

(4). Since its initial description

by Frantz (9) in 1959, the

understanding of SPN has progressively advanced. In recent years,

with advancements in imaging modalities such as CT and MRI, along

with improvements in clinical diagnostic and therapeutic

capabilities, the reported incidence of SPN has increased (10). The histogenesis and underlying

pathogenetic mechanisms of SPN remain incompletely understood.

Kosmahl et al (11)

proposed that SPN originates from primordial cells of the

reproductive ridge and ovarian anlagen, which may integrate with

the developing pancreatic primordium during embryogenesis. This

hypothesis aligns with the clinical observation that SPN

predominantly affects young females (2). Current evidence suggests that SPN

development is associated with mutations in exon 3 of the β-catenin

gene and reduced E-cadherin-mediated signal transduction within the

Wnt signaling pathway (12,13).

Furthermore, emerging studies indicate potential involvement of

other molecular pathways, including the Notch and Hedgehog

signaling pathways, in the pathogenesis of SPN (14,15).

A study conducted by Law et al (16) enrolled a total of 2,744 patients

diagnosed with SPN. The findings indicated that the mean age of the

patient cohort was 28.5 years, with females comprising as high as

87.8% of the study population. Although SPN can arise in any region

of the pancreas, it most frequently occurs in the pancreatic body

and tail. Yu et al (17)

reported a mean tumor diameter of 7.87 cm, with 54.8% of cases

located in the body and tail of the pancreas, while Song et

al (18) observed a mean tumor

size of 6.4 cm, with 60.4% of tumors arising in the same anatomical

region.

SPN lacks specific clinical manifestations.

Approximately one-third of patients are asymptomatic and may be

identified incidentally during routine physical examinations

(6). The most frequently observed

clinical presentations include abdominal pain and discomfort, while

other common symptoms comprise nausea, vomiting, back pain and the

detection of palpable abdominal masses. Laboratory findings in

patients with SPN typically fall within normal ranges and the

majority of tumor markers yield negative results (19,20).

Although tumor markers demonstrate limited diagnostic specificity

for SPN, they serve a valuable role in differential diagnosis,

particularly in distinguishing SPN from malignancies such as

pancreatic cancer.

Given the lack of specificity in laboratory tests

for SPN, imaging modalities such as CT, MRI and ultrasound play a

crucial role in its diagnosis (11). With continuous advancements in

imaging technologies, the accuracy of the preoperative diagnosis of

SPN has significantly improved. CT remains the most widely utilized

imaging method for the preoperative evaluation of SPN, typically

revealing a well-defined, heterogeneous cystic-solid mass that may

be associated with hemorrhage or calcification (6,21). A

limitation of the present study is the absence of MRI evaluation.

Compared to CT, MRI offers superior soft-tissue contrast, enabling

more precise visualization of the tumor's relationship with

adjacent bile ducts and pancreatic ducts, which is of considerable

importance for surgical planning (22). Pancreatic duct dilation is uncommon

in SPN (17). Endoscopic

ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) serves as a

valuable technique for obtaining histological confirmation prior to

surgery. Studies have demonstrated that EUS-FNA achieves a

preoperative diagnostic accuracy exceeding 80% for SPN (23). Nevertheless, due to its invasive

nature and potential complications, including bleeding, infection

and tumor seeding along the needle tract, its clinical application

remains limited. A nationwide study based on Japanese SPN cases

indicated that fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography may

provide additional diagnostic value for small-diameter tumors

(<2 cm) (24). SPN can be

differentiated from pancreatic cancer, pancreatic cystadenoma,

intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN), and pancreatic

pseudocyst based on patient age at onset and CT imaging findings.

Pancreatic cancer typically presents as a hypodense lesion during

the contrast-enhanced phase of CT imaging, with poorly defined

margins relative to adjacent normal pancreatic parenchyma, and is

commonly associated with hepatic and lymph node metastases.

Mucinous cystadenoma is characterized by multilocular cystic

structures with low attenuation, frequently accompanied by

eggshell-like peripheral calcifications, which constitute a

hallmark radiological feature. Serous cystadenoma typically appears

as unilocular or multilocular cystic lesions with fluid-equivalent

density on CT scans, featuring a pathognomonic central stellate

scar and calcification. IPMN of the pancreas manifests as a

low-attenuation mass, often associated with pancreatic ductal

dilatation. Pancreatic pseudocysts are usually depicted as

well-circumscribed, homogeneously attenuated, round or ovoid

lesions on CT imaging, with enhancement limited to the cyst wall

during the contrast-enhanced phase (25).

Surgical resection remains the primary and preferred

treatment modality for SPN (26).

The selection of the surgical approach should be based on tumor

size, anatomical location and intraoperative rapid pathological

evaluation of frozen sections. Several studies have indicated that

surgical resection should still be considered even in cases with

preoperative evidence of local organ invasion or distant metastasis

(27-29).

Emerging evidence suggests that gemcitabine-based chemotherapy

regimens may offer a clinical benefit in patients with metastatic

or unresectable SPN (30,31). The patient of the present study

underwent radiotherapy or chemotherapy. Considering the limited

evidence regarding the application of radiotherapy or chemotherapy

in the treatment of SPN, which is primarily derived from case

reports, the effectiveness of these therapeutic modalities in

managing SPN remains to be fully elucidated and corroborated. The

definitive diagnosis of SPN primarily depends on histopathological

and immunohistochemical analyses. The characteristic pathological

features of SPN include the presence of solid, pseudopapillary and

cystic components, with tumor cells arranged around fibrovascular

cores in a pseudopapillary configuration. Currently, no specific

immunophenotypic profile is unique to SPN; however, several markers

demonstrate consistent expression patterns. In most studies, high

expression levels of β-catenin, progesterone receptor (PR),

synaptophysin (Syn), α-1-antichymotrypsin (AACT), vimentin (Vim)

and CD56 have been observed, whereas chromogranin A (CgA) typically

shows low or negative expression (32,33).

The overexpression of β-catenin aligns with the molecular mechanism

involving mutations in the β-catenin gene and its role in SPN

pathogenesis via the WNT signaling pathway (34). As an immunophenotype associated

with sex hormones, the high expression of PR suggests a potential

involvement of hormonal factors in the development of SPN (35,36).

Wang et al (37) reported

that loss of PR expression was significantly associated with poorer

recurrence-free survival and disease-specific survival.

Immunohistochemical profiling enables differentiation of SPN from

pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and neuroendocrine tumors. Markers

such as β-catenin, lymphoid enhancer-binding factor 1 (LEF-1) and

transcription factor E3 (TFE3) have demonstrated utility in

distinguishing SPN from these mimics (34,38).

Several studies recommend the use of combined immunophenotypic

panels to enhance diagnostic accuracy for SPN (38,39).

Kim et al (39)

demonstrated that a panel consisting of β-catenin, LEF-1 and TFE3

achieved a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 91.9% in

differentiating SPN from pancreatic cancer and neuroendocrine

tumors. Ki-67 serves as a proliferation marker reflecting tumor

cell growth activity. Given that SPN is a low-grade malignant tumor

with an indolent biological behavior, Ki-67 expression is generally

low. Yang et al (40)

indicated that a Ki-67 labeling index ≥4% was associated with

adverse postoperative outcomes in patients with SPN.

Given the low-grade malignant potential of SPN and

its generally favorable prognosis, definitive conclusions regarding

risk factors for benign vs. malignant behavior, recurrence or

metastasis remain elusive. Several studies have investigated the

association between tumor size and malignant potential. Kang et

al (41) reported that a tumor

diameter >5 cm may indicate malignant transformation in SPN. By

contrast, De Robertis et al (42) observed no significant association

between tumor size and malignancy grade. Additionally, the presence

of an incomplete tumor capsule and calcification has been linked to

poorer clinical outcomes in patients with SPN (43,44).

Patients diagnosed with SPN generally demonstrate a

favorable prognosis following surgical resection. A study by Liu

et al (45) followed 243

patients with SPN for an average of almost four years and their

five-year survival rate was even higher at 98.4%. Even if SPN

recurred or spread after the first surgery, numerous individuals

still survived for a long time if they had another operation.

In summary, SPN is a low-grade malignant tumor of

the pancreas that predominantly affects young women between the

ages of 20 and 30 years. It is most frequently located in the

pancreatic body or tail. Due to its indolent clinical course, SPN

often presents without specific symptoms and is commonly detected

incidentally during routine physical examinations. When symptoms

occur, they may include nonspecific abdominal discomfort such as

pain or distension. Laboratory findings are typically unremarkable,

with minimal abnormalities observed in routine blood tests.

Preoperative diagnosis primarily depends on imaging modalities,

particularly contrast-enhanced CT, while definitive diagnosis

relies on histopathological evaluation combined with

immunohistochemical profiling. Accumulating evidence suggests that

an incomplete tumor capsule serves as an independent prognostic

indicator for more aggressive biological behavior in SPN. Complete

surgical resection remains the cornerstone of treatment, offering

favorable long-term outcomes in the majority of cases. Notably,

even in instances of preoperative metastasis or postoperative

recurrence, aggressive surgical intervention can still yield

prolonged survival. Postoperatively, regular follow-up is strongly

recommended for all patients with SPN, particularly those with

high-risk features, to enable early detection and timely management

of potential recurrences or metastases.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

DJ conceived and designed the study. LZ analyzed and

summarized the data and wrote the manuscript. KL, LZ and DJ

collected the laboratory examination data and images of the case.

LZ critically revised the manuscript. KL and LZ confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and approved the

final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the

principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patient consent for publication

The patient involved in the present study was

subjected to standard clinical practice and provided written

informed consent for the publication of medical data and

images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Papavramidis T and Papavramidis S: Solid

pseudopapillary tumors of the pancreas: Review of 718 patients

reported in English literature. J Am Coll Surg. 200:965–972.

2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Wu J, Mao Y, Jiang Y, Song Y, Yu P, Sun S

and Li S: Sex differences in solid pseudopapillary neoplasm of the

pancreas: A population-based study. Cancer Med. 9:6030–6041.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Elta GH, Enestvedt BK, Sauer BG and Lennon

AM: ACG clinical guideline: Diagnosis and management of pancreatic

cysts. Am J Gastroenterol. 113:464–479. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

La Rosa S and Bongiovanni M: Pancreatic

solid pseudopapillary neoplasm: Key pathologic and genetic

features. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 144:829–837. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Boor PJ and Swanson MR: Papillary-cystic

neoplasm of the pancreas. Am J Surg Pathol. 3:69–76.

1979.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Schlosnagle DC and Campbell WG Jr: The

papillary and solid neoplasm of the pancreas:a report of two cases

with electron microscopy,one containing neurosecretory granules.

Cancer. 47:2603–2610. 1981.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Klöppel G, Solcia E, Sobin LH, Longnecker

DS and Capella C (eds): Histological typing of tumours of the

exocrine pancreas. 2nd edition. Springer Berlin, Heidelberg,

1996.

|

|

8

|

Nagtegaal ID, Odze RD, Klimstra D, Paradis

V, Rugge M, Schirmacher P, Washington KM, Carneiro F and Cree IA:

WHO classification of tumours editorial board. The 2019 WHO

classification of tumours of the digestive system. Histopathology.

76:182–188. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Frantz VK: Tumors of the Pancreas. Armed

Forces Institute of Pathology, Washington, DC, pp32-33, 1959.

|

|

10

|

Jena SS, Ray S, Das SAP, Mehta NN, Yadav A

and Nundy S: Rare pseudopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas:

A10-year experience. Surg Res Pract. 2021(7377991)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Kosmahl M, Seada LS, Jänig U, Harms D and

Klöppel G: Solid-pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas: Its origin

revisited. Virchows Arch. 436:473–480. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Ghio M and Vijay A: Molecular alterations

in solid pseudopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas: The achilles

heel in conquering pancreati tumorigenesis. Pancreas. 50:1343–1347.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Cavard C, Audebourg A, Letourneur F,

Audard V, Beuvon F, Cagnard N, Radenen B, Varlet P, Vacher-Lavenu

MC, Perret C and Terris B: Gene expression profiling provides

insights into the pathways involved in solid pseudopapillary

neoplasm of the pancreas. J Pathol. 218:201–209. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Wils LJ and Bijlsma MF: Epigenetic

regulation of the Hedgehog and Wnt pathways in cancer. Crit Rev

Oncol Hematol. 121:23–44. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Park M, Kim M, Hwang D, Park M, Kim WK,

Kim SK, Shin J, Park ES, Kang CM, Paik YK and Kim H:

Characterization of gene expression and activated signaling

pathways in solid-pseudopapillary neoplasm of pancreas. Mod Pathol.

27:580–593. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Law JK, Ahmed A, Singh VK, Akshintala VS,

Olson MT, Raman SP, Ali SZ, Fishman EK, Kamel I, Canto MI, et al: A

systematic review of solid-pseudopapillary neoplasms: Are these

rare lesions? Pancreas. 43:331–337. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Yu PF, Hu ZH, Wang XB, Guo JM, Cheng XD,

Zhang YL and Xu Q: Solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas: A

review of 553 cases in Chinese literature. World J Gastroenterol.

16:1209–1214. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Song H, Dong M, Zhou J, Sheng W, Zhong B

and Gao W: Solid pseudopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas:

Clinicopathologic feature, risk factors of malignancy, and survival

analysis of 53 cases from a single center. Biomed Res Int.

2017(5465261)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Yao J and Song H: A review of

clinicopathological characteristics and treatment of solid

pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas with 2450 cases in Chinese

population. Biomed Res Int. 2020(2829647)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Yang F, Wu W, Wang X, Zhang Q, Bao Y, Zhou

Z, Jin C, Ji Y, Windsor JA, Lou W and Fu D: Grading solid

pseudopapillary tumors of the pancreas:the fudan prognostic index.

Ann Surg Oncol. 28:550–559. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Yu CC, Tseng JH, Yeh CN, Hwang TL and Jan

YY: Clinicopathological study of solid and pseudopapillary tumor of

pancreas:emphasis on magnetic resonance imaging findings. World J

Gastroenterol. 13:1811–1815. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

El Nakeeb A, Abdel Wahab M, Elkashef WF,

Azer M and Kandil T: Solid pseudopapillary tumour of the pancreas:

Incidence,prognosis and outcome of surgery (single center

experience). Int J Surg. 11:447–457. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Kumar NAN, Bhandare MS, Chaudhari V, Sasi

SP and Shrikhande SV: Analysis of 50 cases of solid pseudopapillary

tumor of pancreas: Aggressive surgical resection provides excellent

outcomes. Eur J Surg Oncol. 45:187–191. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Law JK, Stoita A, Wever W, Gleeson FC,

Dries AM, Blackford A, Kiswani V, Shin EJ, Khashab MA, Canto MI, et

al: Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration improves

the pre-operative diagnostic yield of solid pseudopapillary

neoplasm of the pancreas: An international multicenter case series

(with video). Surg Endosc. 28:2592–2598. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Scott J, Martin I, Redhead D, Hammond P

and Garden OJ: Mucinous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas: Imaging

features and diagnostic difficulties. Clin Radiol. 55:187–192.

2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Kurihara K, Hanada K, Serikawa M, Ishii Y,

Tsuboi T, Kawamura R, Sekitou T, Nakamura S, Mori T, Hirano T, et

al: Investigation of fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission

tomography for the diagnosis of solid pseudopapillary neoplasm of

the pancreas: A study associated with a national survey of solid

pseudopapillary neoplasms. Pancreas. 48:1312–1320. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

European Study Group on Cystic Tumours of

the Pancreas. European evidence-based guidelines on pancreatic

cystic neoplasms. Gut. 67:789–804. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Kang CM, Choi SH, Kim SC, Lee WJ, Choi DW

and Kim SW: Korean Pancreatic Surgery Club. Predicting recurrence

of pancreatic solid pseudopapillary tumors after surgical

resection:a multicenter analysis in Korea. Ann Surg. 260:348–355.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Martin RC, Klimstar DS, Brennan MF and

Conlon KC: Solid-pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas:a surgical

enigma? Ann Surg Oncol. 9:35–40. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Prasad TV, Madhusudhan KS, Srivastava DN,

Dash NR and Gupta AK: Transarterial chemoembolization for liver

metastases from solid pseudopapillary epithelial neoplasm of

pancreas: A case report. World J Radiol. 7:61–65. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Maffuz A, Bustamante Fde T, Silva JA and

Torres-Vargas S: Preoperative gemcitabine for unresectable, solid

pseudopapillary tumour of the pancreas. Lancet Oncol. 6:185–186.

2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Serra S and Chetty R: Revision 2: An

immunohistochemical approach and evaluation of solid

pseudopapillary tumour of the pancreas. J Clin Pathol.

61:1153–1159. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Lubezky N, Papoulas M, Lessing Y, Gitstein

G, Brazowski E, Nachmany I, Lahat G, Goykhman Y, Ben-Yehuda A,

Nakache R and Klausner JM: Solid pseudopapillary neoplasm of the

pancreas: Management and long-term outcome. Eur J Surg Oncol.

43:1056–1060. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Din NU, Rahim S, Abdul-Ghafa J, Ahmed A

and Ahmad Z: Clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of

29 cases of solid-pseudopapillary neoplasms of the pancreas in

patients under 20 years of age along with detailed review of

literature. Diagn Pathol. 15(139)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Naar L, Spanomichou DA, Mastoraki A,

Smyrniotis V and Arkadopoulos N: Solid pseudopapillary neoplasms of

the pancreas:A surgical and genetic enigma. World J Surg.

41:1871–1881. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Tang LH, Aydin H, Brennan MF and Klimstra

DS: Clinically aggressive solid pseudopapillary tumors of the

pancreas:a report of two cases with components of undifferentiated

carcinoma and a comparative clinicopathologic analysis of 34

conventional cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 29:512–519. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Wang F, Meng Z, Li S, Zhang Y and Wu H:

Prognostic value of progesterone receptor in solid pseudopapillary

neoplasm of the pancreas:evaluation of a pooled case series. BMC

Gastroenterol. 18(187)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Harrison G, Hemmerich A, Guy C, Perkinson

K, Fleming D, McCall S, Cardona D and Zhang X: Overexpression of

SOX11 and TFE3 in solid-pseudopapillary neoplasms of the pancreas.

Am J Clin Pathol. 149:67–75. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Kim EK, Jang M, Park M and Kim H: LEF1,

TFE3, and AR are putative diagnostic markers of solid

pseudopapillary neoplasms. Oncotarget. 8:93404–93413.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Yang F, Yu X, Bao Y, Du Z, Jin C and Fu D:

Prognostic value of Ki-67 in solid pseudopapillary tumor ofthe

pancreas:Huashan experience and systematic review of the literatur.

Surgery. 159:1023–1031. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Kang CM, Kim KS, Choi JS, Kim H, Lee WJ

and Kim BR: Solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas suggesting

malignant potential. Pancreas. 32:276–280. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

De Robertis R, Marchegiani G, Catania M,

Ambrosetti MC, Capelli P, Salvia R and D'Onofrio M: Solid

pseudopapillary neoplasms of the pancreas:Clinicopathologic and

radiologic features according to size. AJR Am J Roentgenol.

213:1073–1080. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Chung YE, Kim MJ, Choi JY, Lim JS, Hong

HS, Kim YC, Cho HJ, Kim KA and Choi SY: Differentiation of benign

and malignant solid pseudopapillary neoplasms of the pancreas. J

Comput Assist Tomogr. 33:689–694. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Kim HH, Yun SK, Kim JC, Park EK, Seoung

JS, Hur YH, Koh YS, Cho CK, Shin SS, Kweon SS, et al: Clinical

features and surgical outcome of solid pseudopapillary tumor of the

pancreas: 30 consecutive clinical cases. Hepatogastroenterology.

58:1002–1008. 2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Liu M, Liu J, Hu Q, Liu W, Zhang Z, Sun Q,

Qin Y, Yu X, Ji S and Xu X: Management of solid pseudopapillary

neoplasms of pancreas:A single center experience of 243 consecutive

patients. Pancreatology. 19:681–685. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|