Introduction

Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumours (IMT) are

distinctive intermediate-grade soft-tissue neoplasms belonging to

the group of inflammatory spindle cell lesions (1). The worldwide incidence of these

tumours is low at 0.04-0.7% (2)

and clinical data has shown that even though the local recurrence

rate after surgical excision is 25%, they fortunately rarely

metastasize (3). IMTs can occur in

any location, predominantly in the mesentery, retroperitoneum, and

pelvis, frequently remaining entirely asymptomatic until they

attain a size that leads to complications (4). IMTs involving the spleen, or the

pancreas can exert pressure on the surrounding anatomic forms;

splenic vein compression is a dire manifestation since it can lead

to a localized type of portal hypertension known as ‘left-sided.’

In this condition, collateral venous blood flow develops, resulting

in localized dilation of the submucosal venous reticulum of the

gastric fundus, which connects the short and posterior gastric

veins to the coronary veins, potentially leading to the development

of gastric varices, splenomegaly, and hypersplenism (5). These varices may lead to

life-threatening upper gastrointestinal bleeding presenting with

hematemesis and/or melena. Although IMTs have been described in

various sites, including the spleen (6-8)

and the pancreas (9,10), a synchronous occurrence in both

organs is exceptionally rare. Herein, we report the first case, to

our knowledge, of a patient with upper GI bleeding from isolated

gastric varices (IGV) and hypersplenism due to left-sided portal

hypertension caused by an IMT involving both the spleen and the

pancreas.

Case report

A 33-year-old male of urban origin, presented to the

emergency department following multiple episodes of melena. The

patient described abdominal cramping and urgency of defecation,

followed by the passage of black tarry stool. He denied any

associated concerning symptoms in the months prior to the current

presentation, including fatigue, weight loss, abdominal or joint

pain.

This patient reports a previous admission in a

different hospital (within the past six months) for

gastrointestinal bleeding and associated haemoglobin drop requiring

blood transfusions. During this prior hospitalization he underwent

multiple upper endoscopies that revealed isolated gastric varices

(IGV) type 1 located in the fundus that were actively bleeding.

Variceal bleeding was treated with endoscopic obturation using

tissue adhesive. The patient's melena ceased after the endoscopic

intervention and his haemoglobin remained within the normal range.

He was discharged with a referral to a specialized gastroenterology

centre if symptoms recurred. During the same admission, an

abdominal ultrasound examination revealed a 16.5 cm long

splenomegaly and a large intrasplenic cyst (6 cm). Based on

previous abdominal imaging, this was a known asymptomatic splenic

pseudocyst secondary to a car accident injury five years ago.

Notably, the patient was a non-smoker and reported alcohol

consumption of less than 15 units per week. He was not undergoing

any pharmacological treatment and had no significant medical

history, including systemic diseases or a relevant family

history.

On initial presentation at our hospital, the patient

was hemodynamically stable. The physical examination found

splenomegaly, with a spleen palpable 3 cm below the left costal

margin. His abdomen was soft and non-tender, but the digital rectal

exam confirmed black stool. Laboratory data on admission revealed

pancytopenia, with white blood cell count 1.8 k/mcl, haemoglobin

7.5 g/dl, mean corpuscular volume (MCV) 69 fl, and platelets 105

k/mcl. Prothrombin time and biochemistry profile, including liver

function tests, as well as bilirubin and albumin levels showed no

abnormalities. He was admitted to our clinic for monitoring and

further investigation.

After the patient was stabilized with intravenous

fluid resuscitation and blood transfusion, an immediate endoscopy

was performed on this patient, who was rushed to our hospital for

upper gastrointestinal bleeding with normal liver function and

splenomegaly. Endoscopy revealed the presence of varices localized

in the gastric fundus. At that time, no active bleeding was found

and thus no intervention was required, with bleeding resolving on

its own. Transabdominal ultrasonography (US) with Doppler excluded

the presence of systemic portal hypertension and showed no

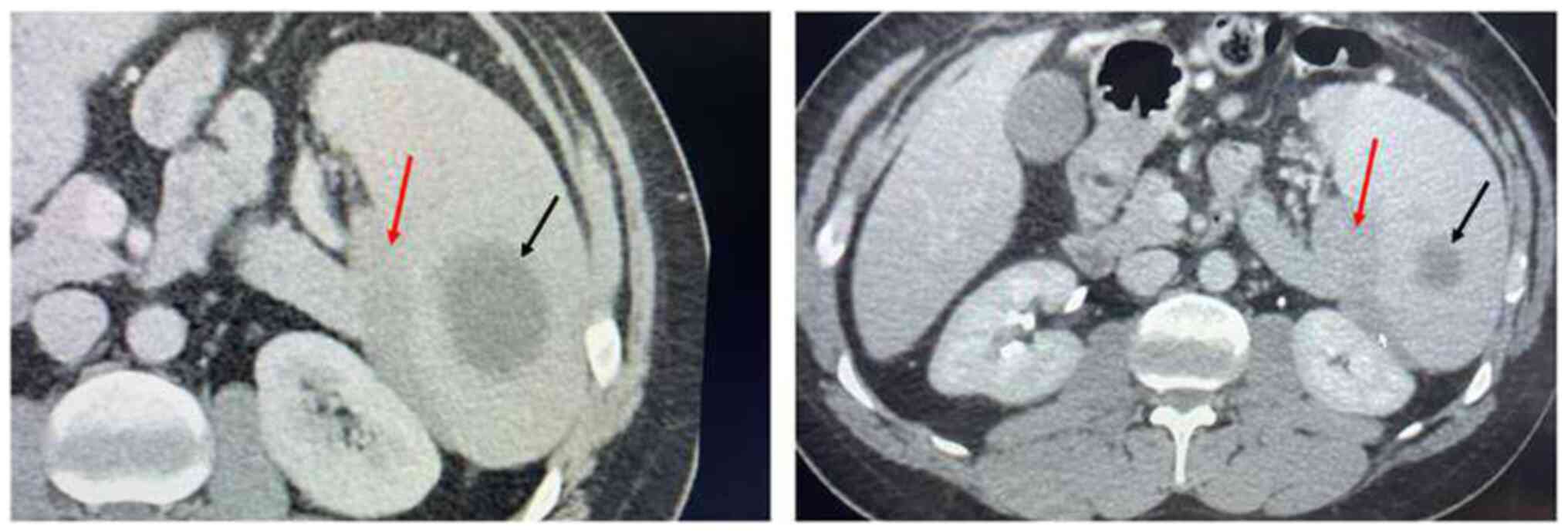

indications of liver cirrhosis. Abdominal computed tomography (CT)

confirmed the known splenomegaly (cephalocaudal diameter 16.5 cm)

and the 6 cm intrasplenic cyst, which remained unchanged in

comparison to previous imaging. Interestingly, a subcapsular

hypodense splenic mass of 7x2 cm was described, extending from the

portal of the spleen to its inferior pole, with a peripheral

localization, showing no contrast enhancement (Fig. 1). Of note, the mass compressed

externally the splenic vein, but neither portal, nor splenic vein

thrombosis were found. The above-mentioned radiological description

did not make it possible to evoke a conclusive diagnosis about the

nature of the mass. Therefore, a Positron Emission Tomography (PET)

scan was performed, in order to better differentiate this splenic

mass as benign or malignant. According to the PET/CT the lesion of

interest in the lower medial margin of the spleen displayed

moderate 18F-FDG uptake (SUVmax=4.3). These findings were

inconclusive for diagnosis.

Concurrently, our management focused on identifying

other causative conditions of cytopenias. Characteristically, low

ferritin levels were identified due to recent blood loss, whereas

no B12 or folic acid deficiency was detected. Iron was repleted

with intravenous ferric carboxymaltose. The peripheral blood smear

revealed no morphological abnormalities. Bone marrow biopsy and

myelogram were performed to investigate the emerging pancytopenia,

revealing a cellular bone marrow without evidence of

infiltration/replacement or failure. In order to eliminate

autoimmune destruction, screening tests for autoantibodies,

including antinuclear Ab, anti-Ro/SS-A Ab, anti-La/SS-B Ab,

anti-cardiolipin Ab, myeloperoxidase-anti-neutrophil-cytoplasmic Ab

(MPO-ANCA) and proteiase-3-ANCA, were carried out, which gave

negative results. We also excluded preceding infections such as

those of brucellosis, tuberculosis, Epstein-Barr virus,

cytomegalovirus, parvovirus, human immunodeficiency virus,

varicella zoster virus, hepatitis B and C viruses. Next, chronic

myeloproliferative disorders were excluded, with negative BCR-ABL,

JAK2 V617F, CARL and MPL W515 mutations. Finally, thrombophilia

screening test results, including lupus anticoagulant, aPl, aCL and

anti-β2-GPI IgM/IgG isotypes, Protein C and S, along with Factor V

Leiden mutation and prothrombin G20210A mutation, were all

negative. Since all the aforementioned conditions were ruled out,

the diagnosis of pancytopenia attributed to hypersplenism due to

left-sided portal hypertension, possibly as a result of the mass

compressing and causing partial occlusion of the splenic vein, was

taken into consideration.

Our patient was stable until his condition

deteriorated with sudden onset haematochezia and subsequent

development of hypovolemic shock. He received three units of packed

red blood cells (pRBC), tranexamic acid, and was started on

intravenous infusion of omeprazole and crystalloids. An emergency

upper GI endoscopy was performed, but due to the large amount of

bleeding and poor endoscopic field of vision, haemostasis was not

achieved. The patient was considered too unstable to proceed with

additional imaging evaluation. Consequently, he underwent an urgent

laparotomy, where a 6cm mass was found on the inferior pole of the

spleen, infiltrating and exceeding the splenic capsule.

Unexpectedly, a similar 7.5 cm scleroelastic solid mass was

discovered, originating from the pancreatic tail. Given the

involvement of both the spleen and pancreas, a splenectomy and

distal pancreatectomy were performed. The splenic artery and vein

were carefully isolated, ligated, and divided to minimize blood

loss. The spleen was then mobilized by dissecting the short gastric

vessels and separating adhesions from the surrounding structures.

The organ, along with the infiltrating mass, was excised en bloc.

For the pancreatic resection, the tail of the pancreas was

mobilized by incising the peritoneal attachments along the splenic

hilum. The lesion was sharply dissected, and a partial distal

pancreatectomy was performed, ensuring a negative resection margin.

A closed-suction drain was placed near the pancreatic stump to

monitor postoperative fluid collection. Both resected specimens

were immediately sent for histopathological examination. The

abdominal cavity was irrigated with warm saline, and the incision

was closed in layers. The procedure was completed without

intraoperative complications.

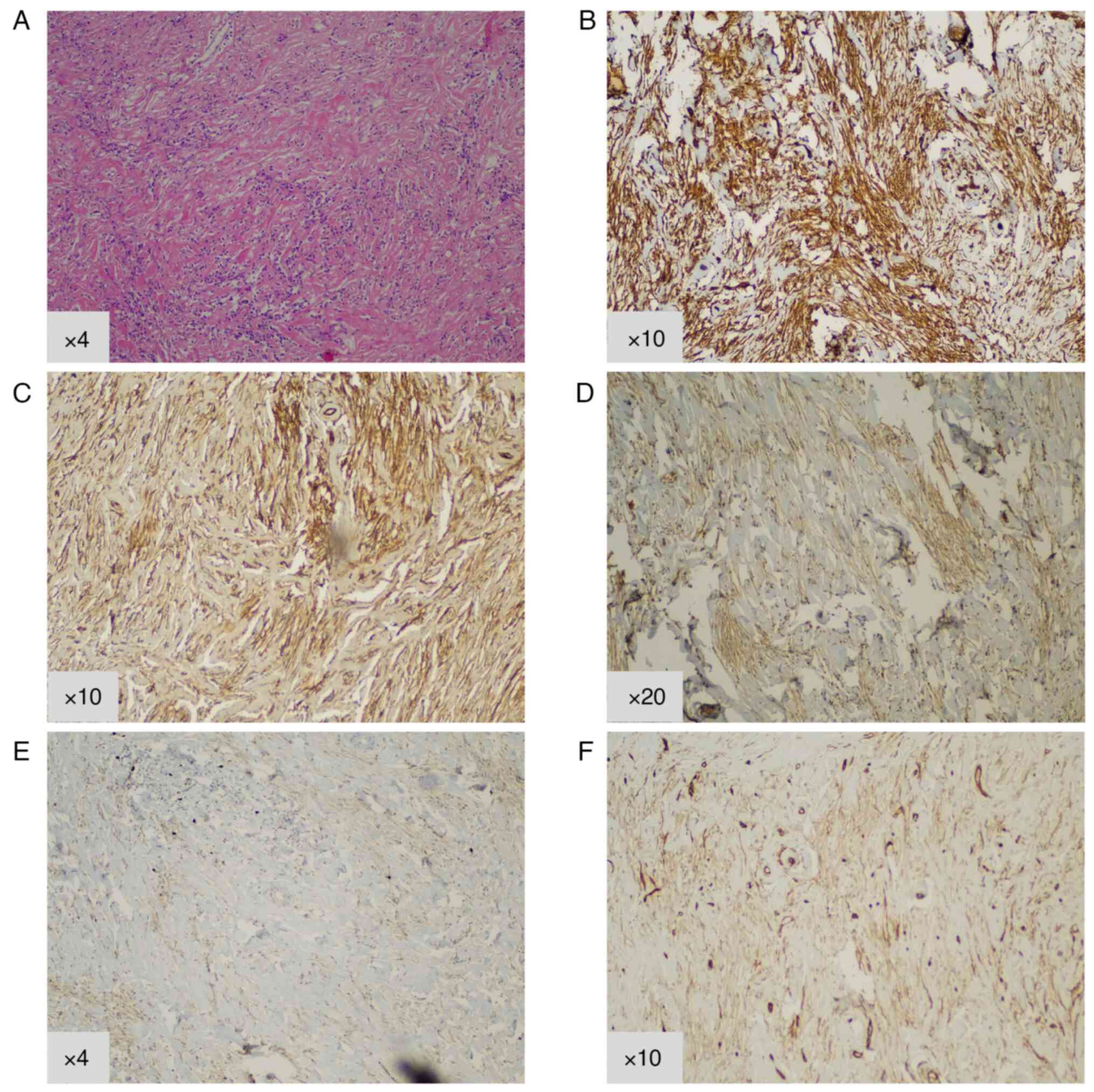

The diagnosis was consistent with inflammatory

myofibroblastic tumour, which is a rare mesenchymal tumour of

intermediate malignant potential. The microscopic examination

revealed the proliferation of spindle-shaped myofibroblasts,

showing swirling and fusiform growth patterns and inflammatory

lymphocytic infiltration (Fig. 2).

The immunohistochemical analysis was performed by manual

immunostaining procedures as per Ventana's protocol. According to

the histologic description, neither overt cytologic atypia nor

mitotic activity were observed, with a low Ki67 marker for

proliferation of <1%. Immunohistological staining was positive

for vimentin (1:300 dilution with PBS; Dako, Carpinteria, CA, USA)

and smooth muscle actin (SMA) (1:150 dilution with PBS; Cell Marque

Corp, Rocklin, CA, USA), displayed weaker expression of Desmin

(1:100 dilution with PBS; Zeta Corp., Sierra Madre, CA, USA) and

CD34 (1/100 dilution with PBS; Deer Park, IL, USA), whereas stains

were negative for S100, AE1/3, CK8/18, CD99, ALK and C-KIT.

Complete resection with R0 margins was achieved.

Over the following days, the patient did not

experience episodes of melena, his haemoglobin remained stable, and

stool colour returned to normal. Notably, a gastroscopy was

performed two months post-operatively that confirmed the resolution

of the gastric varices, and follow-up blood tests showed that

pancytopenia had also resolved. The patient was assessed by medical

oncology; close follow-up was recommended, and no adjuvant therapy

was suggested since complete surgical resection was achieved.

Written informed consent for publication was obtained from the

patient, ensuring ethical compliance and patient acknowledgment of

case reporting.

Discussion

IMTs are tumours of myofibroblast origin which,

despite the presence of an inflammatory immunohistochemical

background and an apparently benign morphological pattern, have

shown malignant potential (11).

IMTs are exceptionally rare, affecting only 150-200 people annually

in the United States (12). They

have been described in patients of all ages, although occurrence is

more frequent in children and young adults (13). Concerning the site and clinical

presentation, IMTs can be found in a variety of body sites and

organs, including the lung, mediastinum, head and neck, liver,

retroperitoneum, and abdominopelvic region, causing a wide array of

manifestations (1,4,14).

They are known for their resistance to standard chemotherapy and

radiation. As a result, surgical removal, when possible, remains

the primary treatment approach.

Our patient presented to the emergency department

with ongoing melena; there have been other cases where patients

harbouring IMTs presented with upper gastrointestinal bleeding, but

their tumours were located in different anatomical locations, such

as the oesophagus (15), the

stomach (16), the duodenum

(17), or even the liver via the

formation of oesophageal varices (18). There have also been IMTs in adults

originating in the pancreas, the majority of them in the head of

the organ, causing obstructive jaundice (19,20),

or even stenosis of the descending duodenum (21). Occurrence in the pancreatic tail,

as observed in our case, is rather unusual, as shown in a recent

review reporting a total of 26 adult cases of pancreatic IMT in the

literature (22). In this series,

none of the patients presented had a synchronous splenic tumour,

making our case the first one. Usually, splenic IMTs in adults are

incidental findings (23-25),

although they may present with pain in the left upper abdomen

(6,7,26,27),

left-sided abdominal distension (28), weight loss, malaise, and fever

(7,27). Another finding is splenomegaly, and

some patients can present with anaemia and signs of hypersplenism

(29), as witnessed in our

patient.

Particularly in our case, the tumour originating

from the pancreas and the spleen apparently obstructed the splenic

vein, leading to left gastric vein dilation and localized

splenoportal hypertension, also known as left-sided portal

hypertension. This occlusion causes the venous drainage of the

spleen to occur via low-pressure collaterals that include the short

and posterior gastric veins to the coronary veins, and the

gastroepiploic veins to the superior mesenteric vein (5). This leads to the formation of

isolated gastric varices (IGV) located in the fundus of the

stomach, commonly termed as type 1 (IGV1) (30). IGVs type 1 are usually attributed

to splenic or pancreatic disease that blocks the splenic venous

flow either by thrombus formation or by neighbouring mass effect,

with splenomegaly and gastrointestinal bleeding being two common

clinical features (31). In our

case, the external compression of the splenic vein by the

inflammatory myofibroblastic tutor demonstrates how even a partial

splenic vein occlusion can alter venous drainage patterns, despite

normal Doppler ultrasound findings. This obstruction can contribute

to variceal formation in the short gastric and left gastroepiploic

veins, with anatomical variations in the portal system and

collateral vessel branching potentially influencing this diversity.

The precise cause of our patient's splenomegaly remains unclear,

but it may stem from increased congestion in the splenic veins and

heightened arterial inflow through the splenic arteries (31). The precise cause of splenomegaly

remains unclear, but it might be associated with heightened

congestion in the splenic veins and increased blood flow and

pressure through the splenic arteries (31). Although splenectomy is the

preferred approach for managing cases with variceal bleeding

complications, there is a lack of agreement in the literature

regarding the treatment of asymptomatic patients.

Due to the tumour-related complications, complete

surgical resection is also the recommended treatment for localized

IMTs, since it ensures a favourable prognosis for most patients

(3). Diagnostic splenic biopsies

are not routinely recommended due to potentially high risk of

haemorrhage and poor specificity (32). Therefore, the final diagnosis of

this intricate entity characterized by myofibroblastic

differentiation is usually based on pathologic findings obtained

after surgery, due to its nonspecific symptoms and imaging

findings. Characteristically, radiological tests, including

ultrasound and CT imaging, are not considered pathognomonic for

IMTs, but can help narrow down the differential diagnosis (33). Even PET/CT findings cannot provide

a definitive diagnosis, besides indicating the biological behaviour

of the tumour cells or detecting distant metastases. In fact, IMTs

have shown high variability of FDG uptake in PET-CTs, with the

SUVmax ranging from 3.3 to 20.8, depending on tumour composition

and the level of inflammatory activity (33). In our patient, low Ki67 expression

of <1% and lack of mitotic activity could correlate with the

failure of the PET-CT to detect the pancreatic mass and the low

FDG-uptake of the splenic tumour, possibly suggesting a benign and

non-inflammatory tendency.

The immunohistochemical profile of the present case

revealed the presence of a myofibroblastic cell type, scattered

among inflammatory cells, mostly lymphocytes. Our patient's tumour

exhibited positive expression of SMA, desmin and cytokeratin after

staining, as do the majority of IMT cases (21,34).

Concerning the molecular changes in IMT, anaplastic lymphoma kinase

(ALK) gene rearrangements leading to uncontrolled cell

proliferation via constitutive tyrosine kinase activation are

extremely common (4,34,35).

Immunohistochemical ALK positivity reliably correlates with ALK

rearrangement, being present in 50 to 60% of IMT cases (36). The ALK gene fuses with

various partner genes, such as TPM3, TPM4, CLTC, and others,

through chromosomal translocations, resulting in the formation of

fusion proteins (1). These ALK

fusion proteins possess constitutive kinase activity, driving

tumorigenesis by activating downstream signalling pathways that

promote cell proliferation and survival (1). However, in patients over the age of

25, ALK positivity is less frequent (26). This was the case with our

33-year-old patient, in whom the tumour was immunohistochemically

negative for ALK expression. The absence of this oncogenic driver

alteration could be a possible indication of the low potential for

malignant transformation (4).

Still, it is difficult to extract safe conclusions since a clear

connection between the histological characteristics of IMT and its

clinical behaviour has not been established (3). Notably, molecular cytogenetic

analysis or next generation sequencing was not performed in our

patient's tumour sample to definitively exclude ALK gene

rearrangements in the inflammatory myofibroblastic tumour cells

(1). Identification of distinct

molecular changes is crucial in cases of recurrent, metastatic, or

unresectable IMT, as revisiting molecular testing upon disease

progression can help determine eligibility for targeted therapies,

which may influence treatment decisions and prognosis for patients

with ALK mutated IMTs. Specifically, tyrosine kinase inhibitors

that disrupt mutant signalling pathways, such as crizotinib, have

demonstrated efficacy in locally advanced or metastatic

ALK-positive IMTs, exhibiting high overall response rates in case

reports and Phase 1b/2 studies (37-39).

Based on data from two multicentre, single-arm, open-label

studies-including 14 paediatric cases from clinical trial

NCT00939770(40) and seven adult

cases from trial NCT01121588(38)-crizotinib was approved in July 2022

for the treatment of adult and paediatric patients with

unresectable, recurrent, or refractory ALK-positive IMT. Overall,

long-term follow-up is essential due to the uncertain and

unpredictable course of some cases harbouring this rare soft-tissue

tumour.

In conclusion, mesenchymal neoplasms represent a

diagnostic challenge with diverse clinical presentations. The

current case was a rare incidence of IGV1 bleeding and

hypersplenism, induced by IMT-associated splenic vein stenosis. Our

patient responded well to surgical resection; however, his rapid

deterioration that required urgent surgery highlights the

importance of early recognition of this rare tumour. In this

context, thorough recording of symptoms and presentation of case

reports will eventually contribute towards the refinement of

diagnostic criteria and, consequently, of therapeutic options for

IMT.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study are included

in the figures and/or tables of this article.

Authors' contributions

EZ, AP and MK drafted the manuscript and made

substantial contributions to the conception of the case report, as

well as to the collection of patient data. IT, AM, MP, AA and CGZ

significantly contributed to data analysis and interpretation,

offering domain-specific expertise. GK was responsible for the

immunohistochemical analysis and pathological evaluation of tissue

samples. EM, MAD and FZ supervised the progress of the study,

contributed to its design, and critically reviewed the manuscript.

FZ and EM confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors

participated in drafting or critically revising the manuscript for

important intellectual content, approved the final version for

publication, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the

work, ensuring the accuracy and integrity of the study are

appropriately addressed. All authors have read and approved the

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Written informed consent for publication was

obtained from the patient.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Siemion K, Reszec-Gielazyn J, Kisluk J,

Roszkowiak L, Zak J and Korzynska A: What do we know about

inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors?-A systematic review. Adv Med

Sci. 67:129–138. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Panagiotopoulos N, Patrini D, Gvinianidze

L, Woo WL, Borg E and Lawrence D: Inflammatory myofibroblastic

tumour of the lung: A reactive lesion or a true neoplasm? J Thorac

Dis. 7:908–911. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Sbaraglia M, Bellan E and Dei Tos AP: The

2020 WHO classification of soft tissue tumours: News and

perspectives. Pathologica. 113:70–84. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Coffin CM, Hornick JL and Fletcher CD:

Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor: Comparison of

clinicopathologic, histologic, and immunohistochemical features

including ALK expression in atypical and aggressive cases. Am J

Surg Pathol. 31:509–520. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Butler JR, Eckert GJ, Zyromski NJ,

Leonardi MJ, Lillemoe KD and Howard TJ: Natural history of

pancreatitis-induced splenic vein thrombosis: A systematic review

and meta-analysis of its incidence and rate of gastrointestinal

bleeding. HPB (Oxford). 13:839–845. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Lv ML, Zhong JQ and Feng H: Inflammatory

myofibroblastic tumor of spleen: A case report. Asian J Surg.

45:2111–2112. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Bettach H, Alami B, Boubbou M, Chbani L,

Maâroufi M and Lamrani MA: Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of

the spleen: A case report. Radiol Case Rep. 16:3117–3119.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Wang B, Xu X and Li YC: Inflammatory

myofibroblastic tumor of the spleen: A case report and review of

the literature. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 12:1795–1800.

2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Wreesmann V, Van Eijck CH, Naus DC, Van

Velthuysen ML, Jeekel J and Mooi WJ: Inflammatory pseudotumour

(inflammatory myofibroblastic tumour) of the pancreas: A report of

six cases associated with obliterative phlebitis. Histopathology.

38:105–110. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Chen ZT, Lin YX, Li MX, Zhang T, Wan DL

and Lin SZ: Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the pancreatic

neck: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases.

9:6418–6427. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Biselli R, Boldrini R, Ferlini C, Boglino

C, Inserra A and Bosman C: Myofibroblastic Tumours: Neoplasias with

divergent behaviour. Ultrastructural and flow cytometric analysis.

Pathol Res Pract. 195:619–632. 1999.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Walsh EM, Xing D, Lippitt MH, Fader AN,

Wethington SL, Meyer CF and Gaillard SL: Molecular tumor board

guides successful treatment of a rare, locally aggressive, uterine

mesenchymal neoplasm. JCO Precis Oncol.

5(PO.20.00189)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

McDermott M: Inflammatory myofibroblastic

tumour. Semin Diagn Pathol: August 31, 2016 (Epub ahead of

print).

|

|

14

|

Meis JM and Enzinger FM: Inflammatory

fibrosarcoma of the mesentery and retroperitoneum. A tumor closely

simulating inflammatory pseudotumor. Am J Surg Pathol.

15:1146–1156. 1991.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Jayarajah U, Bulathsinghala RP, Handagala

DMS and Samarasekera DN: Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the

esophagus presenting with hematemesis and melaena: A case report

and review of literature. Clin Case Rep. 6:82–85. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Shi H, Wei L, Sun L and Guo A: Primary

gastric inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor: A clinicopathologic and

immunohistochemical study of 5 cases. Pathol Res Pract.

206:287–291. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

González MG, Vela D, Álvarez M and Caramés

J: Inflammatory myofibroblastic duodenal tumor: A rare cause of

massive intestinal bleeding. Cancer Biomark. 16:555–557.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Shang J, Wang YY, Dang Y, Zhang XJ, Song Y

and Ruan LT: An inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor in the

transplanted liver displaying quick wash-in and wash-out on

contrast-enhanced ultrasound: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore).

96(e9024)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Jang EJ, Kim KW, Kang SH, Pak MG and Han

SH: Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors arising from pancreas head

and peri-splenic area mimicking a malignancy. Ann Hepatobiliary

Pancreat Surg. 25:287–292. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Lim K, Cho J, Pak MG and Kwon H:

Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the pancreas: A case report

and literature review. Taehan Yongsang Uihakhoe Chi. 81:1497–1503.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Ding D, Bu X and Tian F: Inflammatory

myofibroblastic tumor in the head of the pancreas with anorexia and

vomiting in a 69-year-old man: A case report. Oncol Lett.

12:1546–1550. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

A G H, Kumar S, Singla S and Kurian N:

Aggressive inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of distal pancreas: A

diagnostic and surgical challenge. Cureus.

14(e22820)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Gašljević G and Lamovec J: Malignant

lymphoma of the stomach in association with inflammatory

myofibroblastic tumor of the spleen. A case report. Pathol Res

Pract. 199:745–749. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Ugalde P, García Bernardo C, Granero P,

Miyar A, González C, González-Pinto I, Barneo L and Vazquez L:

Inflammatory pseudotumor of spleen: A case report. Int J Surg Case

Rep. 7C:145–148. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Ma ZH, Tian XF, Ma J and Zhao YF:

Inflammatory pseudotumor of the spleen: A case report and review of

published cases. Oncol Lett. 5:1955–1957. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Koechlin L, Zettl A, Koeberle D, von Flüe

M and Bolli M: Metastatic inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the

spleen: A case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Surg.

2016(8593242)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Yan J, Peng C, Yang W, Wu C, Ding J, Shi T

and Li H: Inflammatory pseudotumour of the spleen: Report of 2

cases and literature review. Can J Surg. 51:75–76. 2008.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Chen WC, Jiang ZY, Zhou F, Wu ZR, Jiang

GX, Zhang BY and Cao LP: A large inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor

involving both stomach and spleen: A case report and review of the

literature. Oncol Lett. 9:811–815. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Moriyama S, Inayoshi A and Kurano R:

Inflammatory pseudotumor of the spleen: Report of a case. Surg

Today. 30:942–946. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Luo X, Nie L, Wang Z, Tsauo J, Tang C and

Li X: Transjugular endovascular recanalization of splenic vein in

patients with regional portal hypertension complicated by

gastrointestinal bleeding. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 37:108–113.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Köklü S, Yüksel O, Arhan M, Çoban Ş, Başar

Ö, Yolcu ÖF, Uçar E, Ibiş M, Ertuǧrul I and Şahin B: Report of 24

left-sided portal hypertension cases: A single-center prospective

cohort study. Dig Dis Sci. 50:976–982. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Alimoglu O and Cevikbas U: Inflammatory

Pseudotumor of the Spleen: Report of a case. Surg Today.

33:960–964. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Dong A, Wang Y, Dong H, Gong J, Cheng C,

Zuo C and Lu J: Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor: FDG PET/CT

findings with pathologic correlation. Clin Nucl Med. 39:113–121.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Coffin CM, Watterson J, Priest JR and

Dehner LP: Extrapulmonary inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor

(inflammatory pseudotumor). A clinicopathologic and

immunohistochemical study of 84 cases. Am J Surg Pathol.

19:859–872. 1995.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Sukov WR, Cheville JC, Carlson AW, Shearer

BM, Piatigorsky EJ, Grogg KL, Sebo TJ, Sinnwell JP and Ketterling

RP: Utility of ALK-1 protein expression and ALK rearrangements in

distinguishing inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor from malignant

spindle cell lesions of the urinary bladder. Mod Pathol.

20:592–603. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Cook JR, Dehner LP, Collins MH, Ma Z,

Morris SW, Coffin CM and Hill DA: Anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK)

expression in the inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor: A comparative

immunohistochemical study. Am J Surg Pathol. 25:1364–1371.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Butrynski JE, D'Adamo DR, Hornick JL, Dal

Cin P, Antonescu CR, Jhanwar SC, Ladanyi M, Capelletti M, Rodig SJ,

Ramaiya N, et al: Crizotinib in ALK-Rearranged inflammatory

myofibroblastic tumor. N Engl J Med. 363:1727–1733. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Gambacorti-Passerini C, Orlov S, Zhang L,

Braiteh F, Huang H, Esaki T, Horibe K, Ahn JS, Beck JT, Edenfield

WJ, et al: Long-term effects of crizotinib in ALK-positive tumors

(Excluding NSCLC): A phase 1b open-label study. Am J Hematol.

93:607–614. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Schöffski P, Sufliarsky J, Gelderblom H,

Blay JY, Strauss SJ, Stacchiotti S, Rutkowski P, Lindner LH, Leahy

MG, Italiano A, et al: Crizotinib in patients with advanced,

inoperable inflammatory myofibroblastic tumours with and without

anaplastic lymphoma kinase gene alterations (European Organisation

for Research and Treatment of Cancer 90101 CREATE): A multicentre,

single-drug, prospective, non-randomised phase 2 trial. Lancet

Respir Med. 6:431–441. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Foster JH, Voss SD, Hall DC, Minard CG,

Balis FM, Wilner K, Berg SL, Fox E, Adamson PC, Blaney SM, et al:

Activity of crizotinib in patients with ALK-Aberrant

relapsed/refractory neuroblastoma: A children's oncology group

study (ADVL0912). Clin Cancer Res. 27:3543–3548. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|