Introduction

PDRN, an abbreviation of polydeoxyribonucleotide,

denotes a family of DNA fragments with low molecular weights or

otherwise a mixture of polydisperse deoxyribonucleotide

heteropolymers with different chain lengths and diverse nucleotide

sequences. PDRNs, originally isolated from human placentas through

a proprietary extraction protocol, were found to exhibit

therapeutic roles against various diseases, particularly tissue

wounding (1,2). As a result of cost limitation and

ethical reason, its source was switched to the sperm cells of some

salmon fishes, Oncorhynchus mykiss (salmon trout) and

Oncorhynchus keta (chum salmon), which could provide

relatively pure genomic DNA with less impurities such as lipids,

peptides and proteins, and have been further extending to other

marine organisms, such as laver (3), sea cucumber sperm (4), and starfish (5). In recent years, PDRNs have been

prepared and characterized from botanic sources, including aloe

(6), ginseng (7) and roselle (8).

PDRNs possess different pharmacological properties

such as wound healing (9,10), anti-inflammatory (11,12),

skin whitening (13),

anti-apoptotic (14),

anti-ischemic (15),

anti-ulcerative (16),

anti-osteoporotic (16),

anti-allodynic (16),

anti-osteonecrotic (16), and bone

regenerative activities (16).

They were also identified to have protective effects against

cadmium-induced toxicity (17) and

carbon tetrachloride-induced acute liver injury (18). PDRN, lately prepared from sea

cucumber, was found to attenuate H2O2-induced

oxidative stress through multiple pathways, which suggests its

plausible application in the prevention and treatment of diverse

oxidative stress-induced diseases (4).

The two action mechanisms of PDRNs have been known

for last a few decades. The first one is that PDRN, acting as an

agonist, selectively stimulates adenosine A2A receptor, which leads

to the regulation of various pharmacological properties (19). PDRN was basically recognized to

have wound healing and anti-inflammatory properties through the

activation of adenosine A2A receptor (19). PDRN plays a mesenchymal stem

cell-based therapeutic role against osteoarthritis through the

activation of adenosine A2A receptor (20). PDRNs alleviate inflammatory

response by the inhibition of Janus kinase/signal transducer and

activator of transcription pathway via the mediation of adenosine

A2A receptor expression and by the inhibition of neuronal cell

death in the model of ischemia/reperfusion injury (19). A second relevant action mechanism

of PDRNs is that their pharmacological properties are mediated by

nucleotide salvage pathways. PDRNs are likely cleaved by cell

membrane enzymes, supply a source for purines and pyrimidines to

different tissues, and are then converted to deoxyribonucleotides

which incorporate into DNA, then activating the proliferation and

growth of various cells, including fibroblasts, preadipocytes,

osteoblasts and chondrocytes (21). The wound healing and

anti-inflammatory properties of PDRNs have been estimated to be

mediated by both the activation of adenosine A2A receptor and the

nucleotide salvage pathways (21).

Regardless of biological sources, the most current

protocols utilized for the preparation of PDRNs include high

temperature treatment, for the purpose of proteins removal, DNA

fragmentation and/or sterilization, which, however, can disrupt the

double-helical DNA conformation then forming the single-stranded

shapes. It is considered that the most of the final PDRN products

usually contain ssDNA forms at the different ratios between dsDNA

and ssDNA, depending on the detailed processes used. But it remains

to clarify whether of the two DNA forms, dsDNA and ssDNA forms, is

directly responsible for the pharmacological efficacies of

PDRNs.

In this work, by thermal denaturation, a commercial

PDRN, named PDRN, was transformed to PDRN-H with substantially

higher ssDNA forms. When skin in vitro beneficial properties

of PDRN and PDRN-H were comparatively analyzed, PDRN-H showed much

higher skin beneficial properties than PDRN, which was supposedly

based on the increased ssDNA proportion in PDRN-H. Collectively,

the ssDNA random coils of PDRNs, as an active player, are

responsible for their in vitro pharmacological

efficacies.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

Ethidium bromide (EtBr), ascorbic acid (AA), DPPH

(2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl), ABTS

[2,2'-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid)], ammonium

persulfate, sodium nitrite, NADH, nitroblue tetrazolium, phenazine

methosulfate, L-tyrosine, L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (L-DOPA),

mushroom tyrosinase type I, kojic acid (KA), Griess reagent,

porcine pancreatic elastase, collagenase type I,

N-succinyl-(L-Ala)3-p-nitroanilide

(STANA), epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), and

N-[3-(2-furyl) acryloyl]-Leu-Gly-Pro-Ala (FALGPA) were from

Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co.. QuantiFluor® dsDNA System

was obtained from Promega Corporation. A PDRN product, denoted as

PDRN throughout this work, was obtained from Mastelli s.r.l.

Officina Bio-Farmaceutica (Placentex, biological source/salmon

sperm). Additional chemicals used were purchased from global

commercial chemical companies.

Preparation of thermal-treated PDRN

(PDRN-H)

PDRN solution was subjected to 94˚C for 30 min,

appropriately diluted with phosphate-buffered saline, and kept on

ice-water bath. If necessary, the thermal-treated PDRN solution,

named PDRN-H, was frozen in the refrigerator.

Characterization of thermal-treated

PDRN solution (PDRN-H)

Whether PDRN-H contained increased ssDNA portions

than PDRN or not was determined through the comparisons of the

absorbance at 260 nm, dsDNA levels and EtBr-stained DNA portions

after agarose gel electrophoresis. The dsDNA levels in PDRN and

PDRN-H were quantified using QuantiFluor® dsDNA System.

EtBr-stained portions of PDRN and PDRN-H were compared through 2%

agarose electophoresis, EtBr staining and the image analysis with

ImageJ version 1.54h (NIH).

DPPH radical scavenging assay

The scavenging activities of PDRN and PDRN-H against

stable DPPH radical were determined as earlier described (22). In a whole volume of 250 µl, the

reaction mixture containing 120 µl of 1.8 mg/ml PDRN or PDRN-H and

130 µl of 0.1 mM DPPH was kept for 30 min at room temperature (RT)

under the darkness. Ascorbic acid (AA, 1 µg/ml) was employed as a

positive control. The absorbance at 517 nm was detected using a

microplate reader and the percent scavenging was calculated using

the formula, Percent Scavenging (%)=[(Control-Test)/Control]

x100.

ABTS radical scavenging activity

assay

The ABTS radical scavenging activities of PDRN and

PDRN-H were determined as previously described (23) with a slight modification. ABTS

radical cations (ABTS•+), generated by reacting ABTS

stock solution (0.07 mM) with 0.12 mM ammonium persulfate, were

kept standing for 16 h in the dark at RT before use. In a whole

volume of 300, 100 µl of 1.8 mg/ml PDRN or PDRN-H was mixed with

200 µl of ABTS•+ solution, and then the reaction mixture

was incubated for 15 min at RT under the darkness. AA (1 µg/ml) was

used as a positive control. The absorbance was measured at 745 nm

and the percent scavenging was calculated as described above.

Superoxide radical scavenging

assay

As previously described (24), the in vitro superoxide

radical scavenging activities of PDRN and PDRN-H were determined.

In a whole volume of 200, 20 µl of 1.2 mg/ml PDRN or PDRN-H was

mixed with 180 µl of 1 mM Tris buffer (pH 8.0) with 100 µM

nitroblue tetrazolium, 156 µM NADH, and 20 µM phenazine

methosulfate. The reaction mixture was stood for 5 min at RT. AA

(20 µg/ml) was used as a positive control. Absorbance at 560 nm was

measured at a microplate reader. The percent scavenging was

calculated as described above.

Nitrite scavenging assay

The in vitro nitrite scavenging activities of

PDRN and PDRN-H were determined as previously described (25). In a whole volume of 150, 60 µl of

1.2 mg/ml PDRN or PDRN-H was mixed with 30 µl of 0.1 mM citrate

buffer (pH 3.0), 6 µl of 50 µg/ml sodium nitrite and 54 µl of

distilled water. The reaction mixture was stored for 60 min at

37˚C, and mixed with the equal volume of Griess reagent. After

incubation for 10 min, absorbance at 538 nm was measured at a

microplate reader. AA (20 µg/ml) was used as a positive control.

The percent scavenging was calculated as described above.

Tyrosinase inhibition activity

assay

As previously described (26), the inhibitory activities of PDRN

and PDRN-H on both L-tyrosine hydroxylase and L-DOPA oxidase

activities of tyrosinase were determined. For the measurement of

the hydroxylase activity, each reaction mixture (200 µl) contained

80 µl of 0.04 mM phosphate buffer (pH 6.8), 40 µl of 0.16 mg/ml

PDRN or PDRN-H, 40 µl of 0.5 mM L-tyrosine in 0.04 mM phosphate

buffer (pH 6.8), and 40 µl of 6 units/ml mushroom tyrosinase type

I, and was then stored for 10 min at 37˚C. The amount of L-DOPA

generated was quantitated by absorbance at 475 nm using a

microplate reader. Kojic acid (KA, 2 µg/ml) was employed a positive

control. For the L-DOPA oxidase activity, 0.5 mM L-DOPA was used,

instead of L-tyrosine, as a substrate, and dopaquinone generated

was quantified by absorbance at 450 nm. Kojic acid (KA, 10 µg/ml)

was used a positive control. The percent inhibition was calculated

using the formula, Percent Inhibition (%)=[(Control-Test)/Control]

x100.

Elastase inhibition activity

assay

Elastase inhibition activity was determined by

measuring an attenuation in elastase activity in the presence of

PDRN or PDRN-H. Elastase activity was quantified based upon the

generation of p-nitroaniline from STANA utilized as a

chromogenic substrate (27). The

reaction mixture consisting of 100 µl of 0.2 M Tris buffer (pH 8.0)

and 50 µl of 1.2 mg/ml PDRN or PDRN-H was pre-incubated with 100 µl

STANA (0.8 mM) for 20 min at 37˚C, and the enzymatic reaction was

started by adding 50 µl porcine pancreatic elastase (0.1 U/ml) in

0.2 M Tris buffer (pH 8.0). Absorbance at 410 nm was measured at a

microplate reader. EGCG (20 µg/ml) was used as a positive control,

and the percent inhibition was calculated as described above.

Collagenase inhibition activity

assay

Collagenase inhibition activities of PDRN and PDRN-H

were determined by measuring a diminishment in collagenase

activity, based on previously described spectrophotometric assay

(28) with a slight modification.

Clostridium histolyticum collagenase type I (1 mg/ml, 20 µl)

was allowed to react with 1.8 mg/ml PDRN or PDRN-H (20 µl) in a

96-well microtiter plate containing 20 µl of 50 mM Tris buffer (pH

7.4) with 0.36 mM CaCl2 for 20 min in the dark at 37˚C.

After the pre-incubation, 40 µl FALGPA (2.4 mM) was added to each

well and the mixture was further incubated for 30 min in the dark

at 37˚C. Absorbance at 335 nm was measured at a microplate reader.

EGCG (20 µg/ml) was used as a positive control, and the percent

inhibition was calculated as described above.

Statistical analysis

Experiments, in this work, were repeated at least

three times. The data were presented as mean ± SD. The differences

between experimental groups were analyzed using one-way ANOVA

subsequently with post hoc Tukey HSD test for multiple comparisons.

A P<0.05 was recognized to be statistically significant.

Results

The increase of ssDNA portion in

PDRN-H

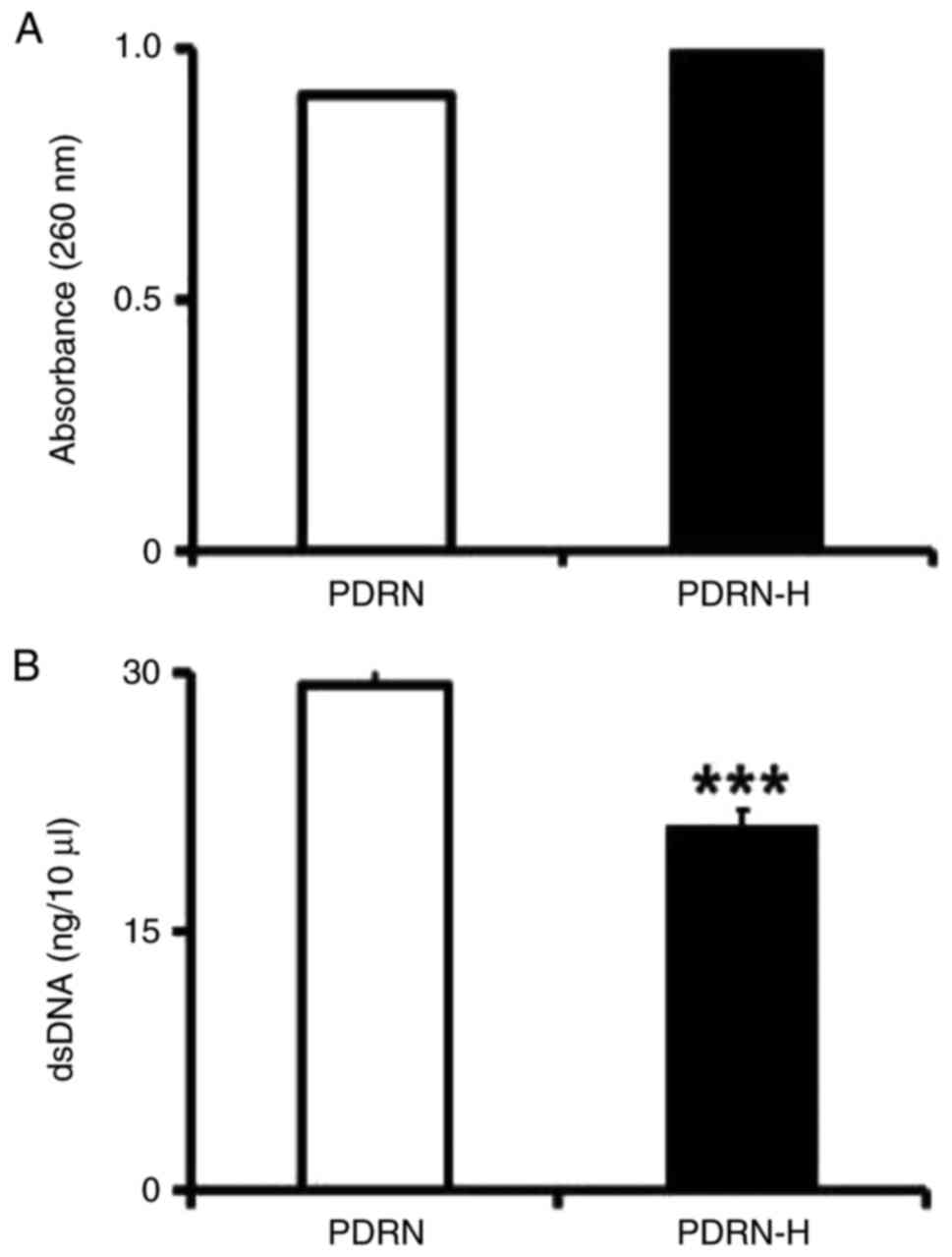

The UV light absorbances of PDRN and PDRN-H at 260

nm, shown in Fig. 1A, indicated

that PDRN-H exerted ~10% higher absorbance than PDRN. If PDRN was

presumed to be full of dsDNA, the treatment was thought to induce

~26.3% denaturation, since the complete denaturation of dsDNA

causes ~38% increase in absorbance at 260 nm. However, since

commercial PDRNs are believed to already have certain degrees of

ssDNA portions due to their manufacturing protocols, the percentage

of new thermal denaturation from the dsDNA portion might be

>26.3%. As shown in Fig. 1B,

dsDNA content was reduced to 71.6% in PDRN-H, compared to that of

PDRN, suggesting that ~28.4% of the existing dsDNA in PDRN would be

transformed to ssDNA in PDRN-H.

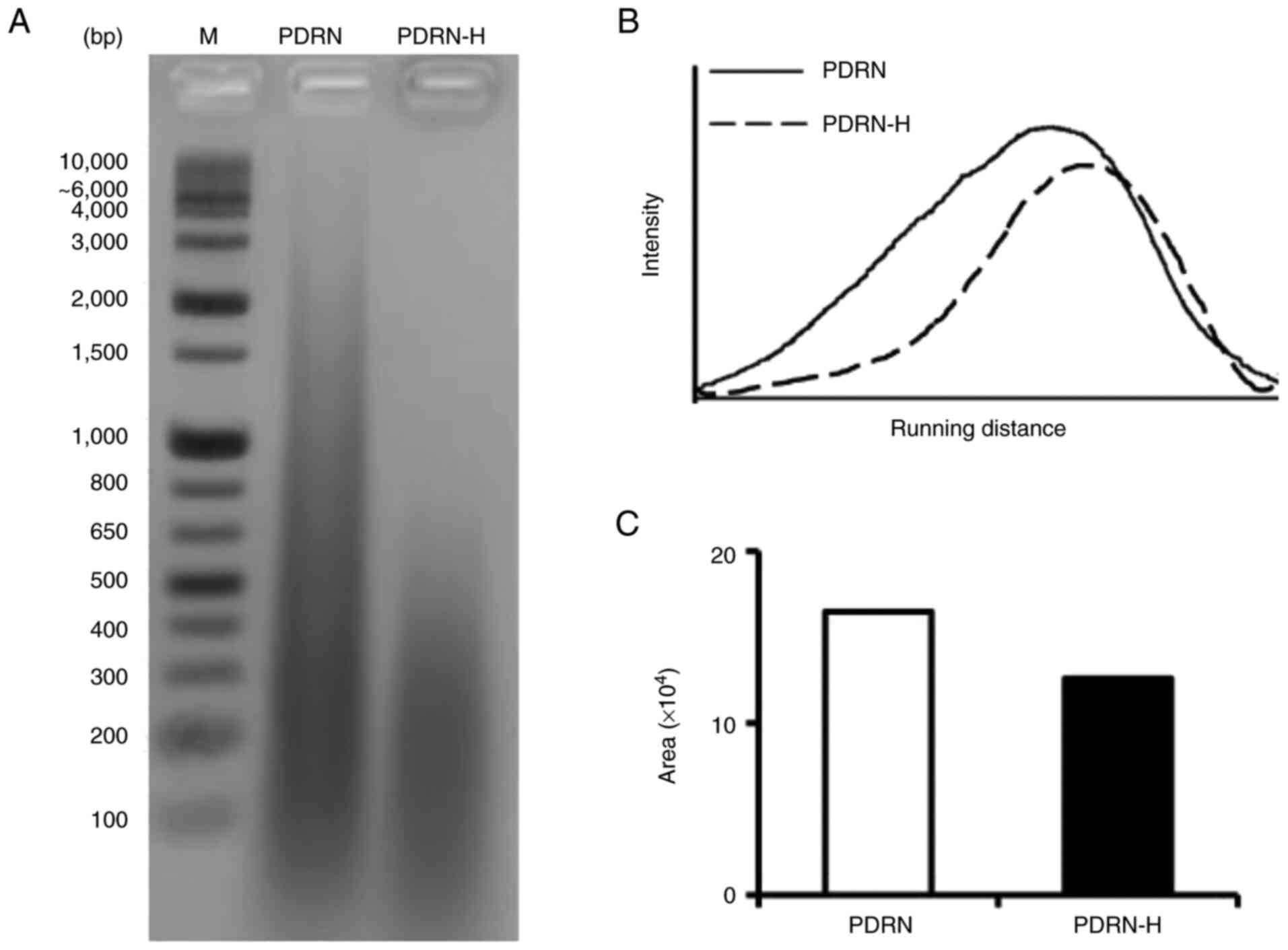

The transformation of dsDNA to ssDNA due to the

thermal denaturation was further examined by EtBr staining after

agarose gel electrophoresis. As shown in Fig. 2A, the EtBr-stained area of PDRN-H

became smaller and migrated faster than that of PDRN, suggesting

the increased portion of ssDNA in PDRN-H. Using ImageJ software,

the intensity profiles as a function of gel distance were drawn as

shown in Fig. 2B. When profile

areas of the lanes of PDRN and PDRN-H were calculated by

comparative densitometric quantification, the profile area of the

PDRN-H lane appeared to be 76.4% of that of the PDRN lane (Fig. 2C). This diminishment in PDRN-H

proposes that 24.6% of dsDNA in PDRN were transformed to ssDNA in

PDRN-H, which was not sufficiently stained with EtBr. Based upon

the mean of the three estimated values, the about 26.4% of the

existing dsDNA in PDRN was determined to denature to ssDNA in

PDRN-H.

Total antioxidant capacity

ROS, regarded as chemically reactive chemical

species containing oxygen, present in the body are mostly of

endogenous origin, and can also be produced in response to external

stimuli, such as ionizing radiation, UV light, pollution, alcohol

and tobacco consumption, toxic agents, and drugs (29). Although ROS play essential

biological roles, such as cell survival, proliferation, growth,

signaling and differentiation and immune response, oxidative stress

is induced from an imbalance between production and elimination of

ROS in cells and tissues. Oxidative stress is closely linked with

many disorders, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease,

cancer, atherosclerosis, Alzheimer's disease, inflammatory

diseases, and others (30).

Scavenging activities against free radicals have been thought as an

antioxidant strategy in the prevention of oxidative stress-related

disorders.

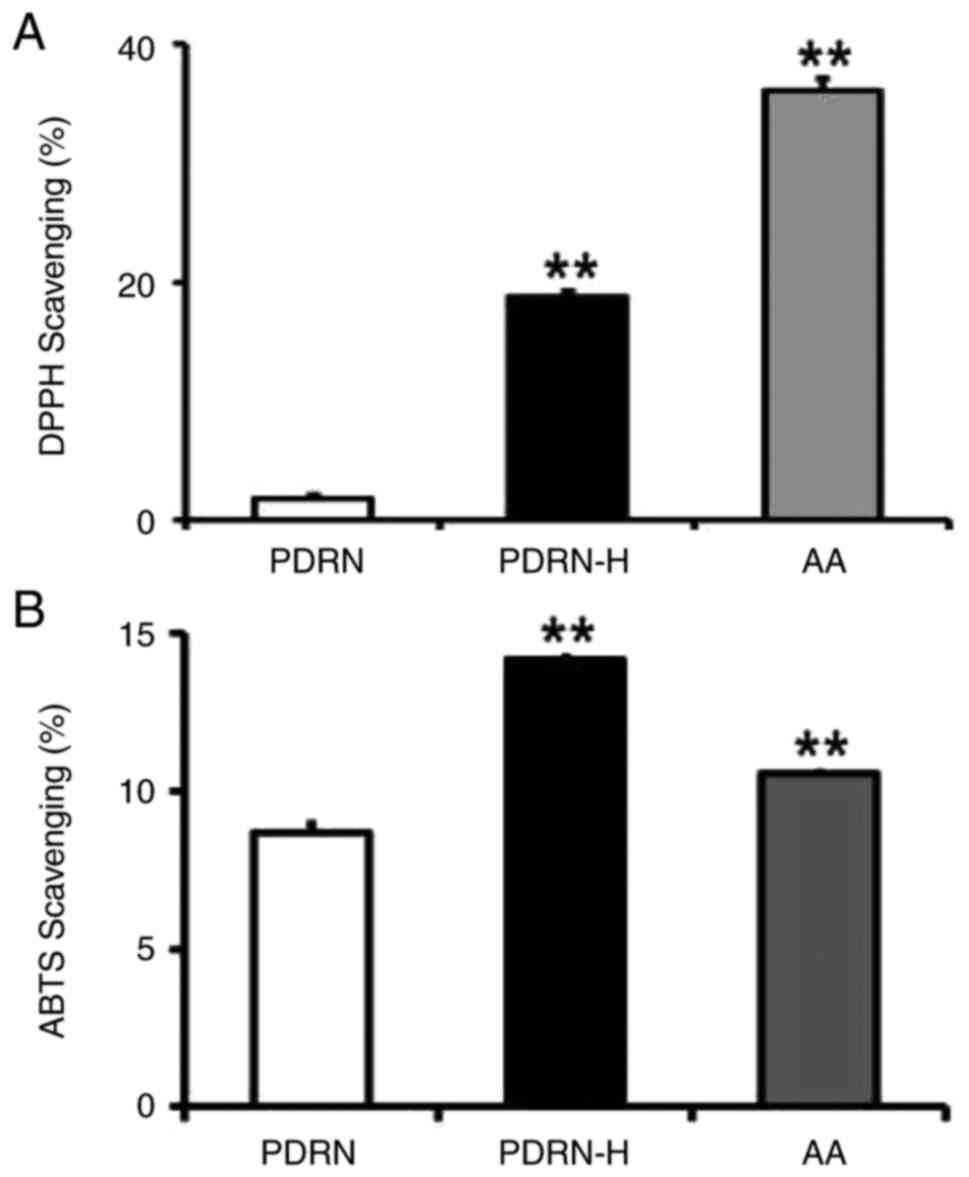

Total antioxidant activities of PDRN and PDRN-H were

evaluated using DPPH and ABTS scavenging assays. As shown in

Fig. 3A, PDRN and PDRN-H exhibited

1.8 and 18.8% scavenging activities in DPPH scavenging assay,

respectively. In ABTS scavenging assay, PDRN and PDRN-H gave rise

to 8.7 and 14.2% scavenging activities, respectively (Fig. 3B). The results show that PDRN-H

contains 10.4- and 1.6-fold higher scavenging activities over PDRN

in DPPH and ABTS scavenging assays, respectively. AA, used as a

positive control, exhibited 36.1 and 10.6% scavenging activities in

DPPH (Fig. 3A) and ABTS (Fig. 3B) scavenging assays, respectively.

In brief, PDRN-H possesses significantly higher total antioxidant

activities than PDRN, due to the increased ssDNA random coils.

Superoxide scavenging activity

Superoxide radical anion

(O2•−) is a primary ROS which is the first

species formed in the enzymatic respiratory chain by the reduction

of oxygen by the transfer of an electron. It is converted to

hydrogen peroxide by superoxide dismutase and further to hydroxyl

radical. Although its cellular level is in vivo controlled

by superoxide dismutase and superoxide reductase, their

insufficiency becomes responsible for oxidative stress in organisms

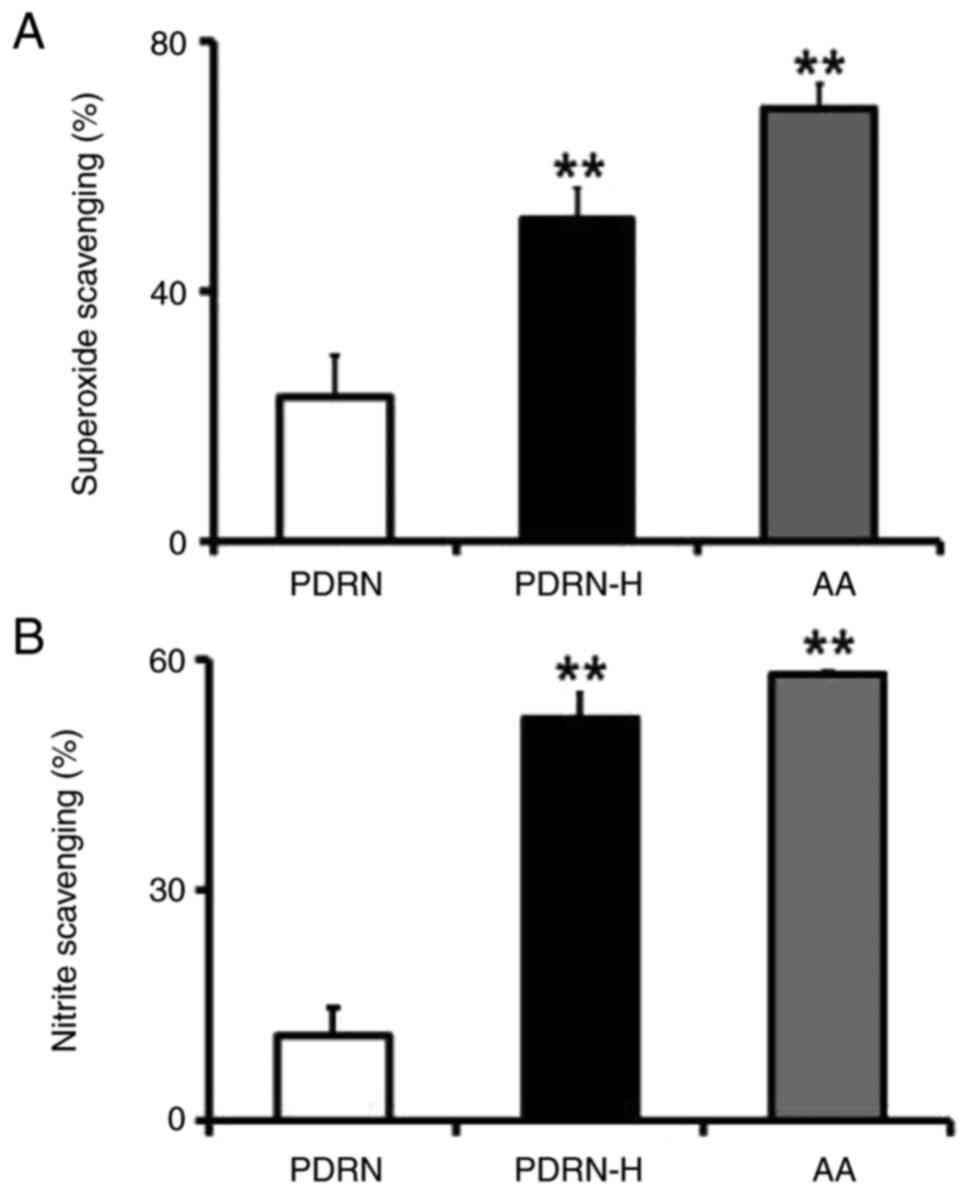

(29). In the scavenging assay

against superoxide radical, PDRN and PDRN-H displayed 23.0 and

51.5% scavenging activities, respectively (Fig. 4A). It suggests that PDRN-H has

2.2-fold higher scavenging activity over PDRN, which is based upon

the enhanced ssDNA portion of PDRN-H. AA, used as a positive

control, showed 69.2% scavenging activity in superoxide scavenging

assay (Fig. 4A).

Nitrite scavenging activity

Although nitric oxide (NO) displays an

anti-inflammatory activity under normal physiological situations,

it also acts as a key mediator in the induction of

inflammation based upon its inappropriate or excessive production

in diverse cells (31). Low-level

constitutive generation of NO is involved in in the maintenance of

barrier function, whereas NO synthetase activity, stimulated by

skin wounding or UV light, results in high-level NO through complex

reactions among diverse skin cells, and causes serious cutaneous

diseases such as atopic dermatitis and psoriasis (32). The generated NO undergoes the

oxidative breakdown metabolism to nitrite, a stable NO storage

form, and nitrite is reversely recycled to NO through

nitrate-nitrite-NO axis under inflamed skin conditions, such as UV

exposure and other inflammation-related diseases (33). Accordingly, anti-inflammatory

capacities of certain substances have been widely evaluated using

in vitro nitrite scavenging activity assay.

When the nitrite scavenging activities of PDRN and

PDRN-H were analyzed using the in vitro assay, they brought

about 11.1 and 52.3% scavenging activities, respectively (Fig. 4B). The result indicates that PDRN-H

has 4.7-fold higher scavenging activity on nitrite than PDRN. This

increment is thought to arise from the enhanced ssDNA random coils

in PDRN-H. Accordingly, PDRN-H was presumed to have significantly

higher anti-inflammatory property over PDRN. AA, used as a positive

control, showed 58.1% scavenging activity in nitrite scavenging

assay (Fig. 4B).

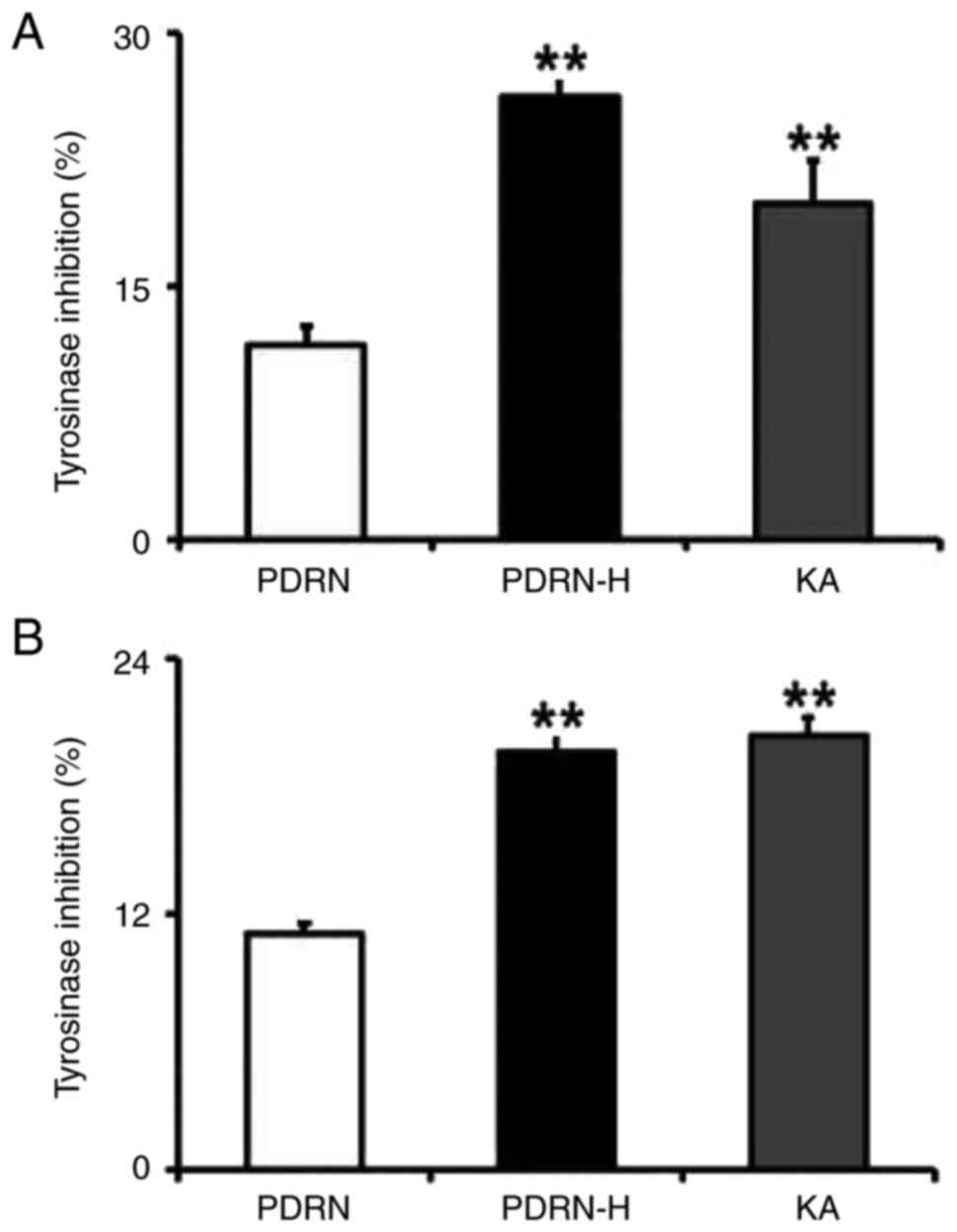

Tyrosinase inhibition activity

Although melanin protects the skin against the

harmful effects of UV irradiation, DNA damage and oxidative stress,

its overproduction leads to severe physical and psychological

distress, including skin darkening and aging, requiring the

approaches to preserve skin homeostasis (34). Tyrosinase, a copper-containing

rate-limiting enzyme located in the membrane of melanocytes,

catalyzes the rate limiting reactions of melanin synthesis: the

hydroxylation of L-tyrosine to 3,4-dihydroxy-L-phenylalanine

(L-DOPA) and the oxidation of L-DOPA to o-dopaquinone. The

inhibition of tyrosinase activity diminishes melanin synthesis,

then whitening the skin.

The inhibition activities of both PDRN and PDRN-H

were analyzed separately on the tyrosine hydroxylase and L-DOPA

oxidase activities of tyrosinase (Fig.

5). As shown in Fig. 5A, PDRN

and PDRN-H exhibited 11.5 and 26.2% inhibition activities on the

tyrosine hydroxylase activity, implying the 2.2-fold increased

inhibition activity of PDRN-H. In the L-DOPA oxidase inhibition

assay (Fig. 5B), they gave rise to

11.0 and 19.6% inhibition activity, respectively. This results in

the 1.8-fold higher inhibition activity of PDRN-H. Kojic acid (KA),

used as a positive control, displayed 19.8 and 20.4% inhibition

activities on the tyrosine hydroxylase (Fig. 5A) and the L-DOPA oxidase (Fig. 5B) activities of tyrosinase,

respectively. Collectively, PDRN-H has the significantly increased

inhibition activities against both tyrosine hydroxylase and L-DOPA

oxidase activities of tyrosinase and is subsequently estimated to

have much improved whitening activity.

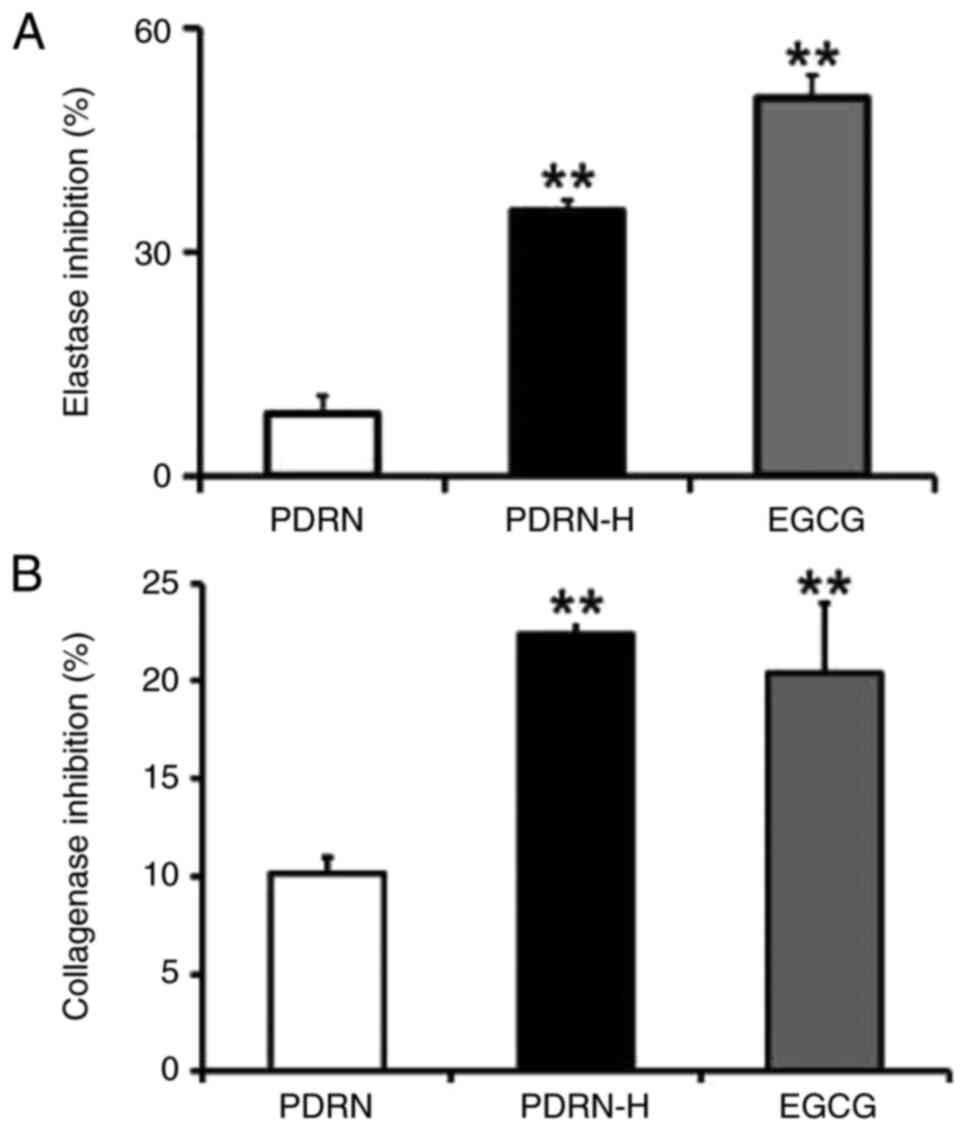

Elastase and collagenase inhibition

activities

Elastin and collagen, produced by fibroblasts, are

predominantly rich components in skin dermis extracellular matrix

(ECM). Breakdown and disorganization of elastin and collagen, two

main ECM proteins, bring about major characteristics of skin aging,

such as wrinkles, sagging, pigmentation and skin thinning, due to

the enhanced activation of elastase and collagenases (27). If the substances of certain origin

inhibit elastase and collagenase activities, they are presumed to

delay skin aging.

The inhibition activities of both PDRN and PDRN-H

were evaluated on elastase and collagenase activities. As shown in

Fig. 6A, PDRN and PDRN-H showed

9.0 and 35.1% inhibition activities against elastase activity,

respectively. As shown in Fig. 6B,

PDRN and PDRN-H showed 10.2 and 22.4% inhibition activities against

collagenase activity, respectively. From the results, PDRN-H was

found to have the 3.9- and 2.2-fold higher inhibition activities

against elastase and collagenase activities over PDRN,

respectively. EGCG, used as a positive control, displayed 50.5 and

20.4% inhibition activities on the elastase (Fig. 6A) and collagenase (Fig. 6B) activities, respectively. Based

upon the increased level of ssDNA portion in PDRN-H, it retains

significantly high inhibition activities against the two wrinkling

enzymes, which further suggests its strong skin anti-aging

properties.

Discussion

PDRNs have been proved to possess skin beneficial

properties using various experimental techniques. PDRN exhibits

antioxidant activities which suppress oxidative stress in skin

cells (35). It directly inhibits

mushroom and cellular tyrosinase activities, then lowering the

cellular melanin content in the melanocytes, and has attenuating

ability on the gene expression of tyrosinase-related protein 1,

another enzyme involved in the synthesis of melanin (35). It inhibits in vitro elastase

activity and suppresses matrix metalloproteinase-1 gene expression

in human skin fibroblast cells (35). In human dermal fibroblasts under

ultraviolet-B radiation, PDRN was identified to bring about the

attenuation of cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers, the enhancement of

DNA repair and the activation of p53 protein, suggesting its

protective effect against UV-induced DNA damage (36,37).

It has a treatment effect against psoriasis associated with chronic

inflammation, which is linked to its dual mode of action (38). Taken together, PDRNs retain

potential roles in preserving healthy skin homeostasis and

protecting against skin photoaging.

When thermal denaturation was carried out to augment

the ssDNA content in a commercial PDRN, the thermal-denatured PDRN

(PDRN-H) was determined to have the significantly enhanced ssDNA

content, as a result of the denaturation from about 26.4% of the

existing dsDNA in the non-thermal PDRN. When several skin in

vitro pharmacological properties of PDRN-H and PDRN were

comparatively measured, PDRN-H was found to have considerably

higher activities than PDRN, within the increasing range of 1.6- to

10.3-fold (Table I). This finding

strongly assures that the ssDNA random coils, markedly enriched in

PDRN-H, but not the dsDNA helical forms, relatively rich in the

non-thermal PDRN, are actually responsible for the pharmacological

activities tested. This work also demonstrates that non-thermal

PDRN contains the tested activities to a certain degree. It could

be thought that PDRN itself contains some degree of the ssDNA

portions which are presumed to be formed during the preparation

processes. The notion that ssDNA random coil acts as an active and

functional player of PDRNs is assisted indirectly by defibrotide

which is a polydisperse mixture of single-stranded

oligodeoxyribonucleotides prepared by controlled depolymerization

of purified porcine intestinal mucosa genomic DNA (39). Defibrotide was originally begun to

use to cure veno-occlusive disease, and has been found to contain

plasmin activating, anti-atherosclerotic, anti-inflammatory,

anti-ischemic and anti-thrombotic properties (39,40).

The pharmacological properties of defibrotide, chemically as

single-stranded oligodeoxyribonucleotides, have been naturally

attributed by the ssDNA forms. However, diverse PDRNs and

PDRN-based products, in the absence of the detailed information on

the proportions of dsDNA and ssDNA, have been utilized for the

purposes of academic research and medical and industrial

application. In the advanced research, the various types of

next-phase works, such as the validation in cellular in

vitro models (for example, keratinocytes, skin fibroblasts,

etc.), large-scale preparation of PDRNs in ssDNA forms,

optimization of size and composition of single-stranded PDRNs,

elucidation of mechanistic mechanism, application to animal and

human skin, and so on, can be accomplished.

| Table IA summary on the thermal-induced

enhancements in in vitro skin beneficial properties of a

commercial PDRN product. |

Table I

A summary on the thermal-induced

enhancements in in vitro skin beneficial properties of a

commercial PDRN product.

| Beneficial

properties | Enhancement

(PDRN-H/PDRN)a |

|---|

| Antioxidant

properties | |

|

DPPH

scavenging activity | 10.3 |

|

ABTS

scavenging activity | 1.6 |

|

Superoxide

scavenging activity | 2.2 |

| Anti-inflammatory

properties | |

|

Nitrite

scavenging activity | 4.7 |

| Skin whitening

properties | |

|

Tyrosinase

inhibition activityb | 2.3 |

|

Tyrosinase

inhibition activityc | 1.8 |

| Antiwrinkle

properties | |

|

Elastase

inhibition activity | 3.9 |

|

Collagenase

inhibition activity | 2.2 |

The insight, obtained from the non-celled in

vitro assays used, strongly implies that the ssDNA forms of

PDRNs, without metabolic alteration, can interact with their

reacting molecules, such as protein molecules, such as tyrosinase,

elastase and collagenase, and small molecules such as DPPH and ABTS

radicals, superoxide radical ion and nitrite ion. That is, the

primary hydrolytic metabolites of PDRNs inside and/or outside

cells, such as deoxyribonucleotides, deoxyribonucleosides and free

bases, are not directly involved in their skin in vitro

properties. Direct contact between the ssDNA forms of PDRNs and

corresponding protein molecules can be more convinced by binding

studies, such as molecular docking and modified mobility shift

assay.

Based on this work, it is thought that the ssDNA

form, but not the dsDNA form, of PDRN acts as an active player in

performing its various pharmacological properties, including skin

in vitro properties. Also based on the use of the non-celled

in vitro assays, it is presumed that the skin in

vitro properties of PDRNs are displayed in a manner which is

independent on adenosine A2A receptor activation and nucleotide

salvage pathway, the two current mechanisms of PDRNs. Through the

coming studies, it can be decided whether the functional role of

the ssDNA forms of PDRNs is linked with their known mechanisms or

not. Considering that the free bases of PDRNs are necessarily

required for their action as an agonist of adenosine A2A receptor,

the ssDNA forms of PDRNs, based upon the fact that ssDNA only

retains unpaired, exposed bases, are thought to be much more

adequate than the dsDNA forms.

In conclusion, the ssDNA forms of PDRNs act as an

active and functional player in the performance of their in

vitro pharmacological properties, including skin in

vitro beneficial properties. Non-celled in vitro assay

system used implies that PDRNs are effective without metabolic

alteration and that their ssDNA random coils make a direct contact

with the appropriate reacting molecules. It seems that the in

vitro pharmacological properties of PDRNs are not mediated

through adenosine A2A receptor activation and nucleotide salvage

pathways. This is the novel finding on the functional action

mechanism of PDRNs, which greatly influence their academic research

and production. In the future, PDRNs in single-stranded DNA forms

but not double-stranded DNA forms are expected to be more desirable

in the generation of PDRNs and PDRN-based products for cosmetic and

pharmaceutical uses.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

HL and CL conceptualized this study. HL, KK and CL

designed the experiments of this study. YH, HB and HK performed the

experiments. HK analyzed the data. KK and CL wrote the manuscript.

All authors have read and approved the final version of manuscript.

HK and CL confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Tonello G, Daglio M, Zaccarelli N,

Sottofattori E, Mazzei M and Balbi A: Characterization and

quantitation of the active polynucleotide fraction (PDRN) from

human placenta, a tissue repair stimulating agent. J Pharm Biomed

Anal. 14:1555–1560. 1996.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Pan SY, Chan MKS, Wong MBF, Klokol D and

Chernykh V: Placental therapy: An insight to their biological and

therapeutic properties. J Med Ther. 1:1–6. 2017.

|

|

3

|

Kim TH, Heo SY, Han JS and Jung WK:

Anti-inflammatory effect of polydeoxyribonucleotides (PDRN)

extracted from red alga (Porphyra sp.) (Ps-PDRN) in RAW 264.7

macrophages stimulated with Escherichia coli

lipopolysaccharides: A comparative study with commercial PDRN. Cell

Biochem Funct. 41:889–897. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Shu Z, Ji Y, Liu F, Jing Y, Jiao C, Li Y,

Zhao Y, Wang G and Zhang J: Proteomics analysis of the protective

effect of polydeoxyribonucleotide extracted from sea cucumber

(Apostichopus japonicus) sperm in a hydrogen

peroxide-induced RAW264.7 cell injury model. Mar Drugs.

22(325)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Kim TH, Kim SC, Park WS, Choi IW, Kim HW,

Kang HW, Kim YM and Jung WK: PCL/gelatin nanofibers incorporated

with starfish polydeoxyribonucleotides for potential wound healing

applications. Mater Des. 229(111912)2023.

|

|

6

|

Kim M, Kim WJ, Lee HK, Kwon YS and Choi

YM: Efficacy in vitro antioxidation and in vivo skin barrier

recovery of composition containing mineral-cation-phyto DNA

extracted from Aloe vera adventitious root. Asian J Beauty

Cosmetol. 21:231–246. 2023.

|

|

7

|

Lee KS, Lee S, Wang H, Lee G, Kim S, Ryu

YH, Chang NH and Kang YW: Analysis of skin regeneration and

barrier-improvement efficacy of polydeoxyribonucleotide isolated

from Panax ginseng (C.A. Mey.) adventitious root. Molecules.

28(7240)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Kim E, Choi S, Kim SY, Jang SJ, Lee S, Kim

H, Jang JH, Seo HH, Lee JH, Choi SS and Moh SH: Wound healing

effect of polydeoxyribonucleotide derived from Hibiscus

sabdariffa callus via Nrf2 signaling in human keratinocytes.

Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 728(150335)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Shin J, Park G, Lee J and Bae H: The

effect of polydeoxyribonucleotide on chronic non-healing wound of

an amputee: A case report. Ann Rehabil Med. 42:630–633.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Yun J, Park S, Park HY and Lee KA:

Efficacy of polydeoxyribonucleotide in promoting the healing of

diabetic wounds in a murine model of streptozotocin-induced

diabetes: A pilot experiment. Int J Mol Sci.

24(1932)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Picciolo G, Mannino F, Irrera N, Altavilla

D, Minutoli L, Vaccaro M, Arcoraci V, Squadrito V, Picciolo G,

Squadrito F and Pallio G: PDRN, a natural bioactive compound,

blunts inflammation and positively reprograms healing genes in an

‘in vitro’ model of oral mucositis. Biomed Pharmacother.

138(111538)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Hwang L, Jin JJ, Ko IG, Kim S, Cho YA,

Sung JS, Choi CW and Chang BS: Polydeoxyribonucleotide attenuates

airway inflammation through A2AR signaling pathway in PM10-exposed

mice. Int Neurourol J. 25 (Suppl 1):S19–S26. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Noh TK, Chung BY, Kim SY, Lee MH, Kim MJ,

Youn CS, Lee MW and Chang SE: Novel anti-melanogenesis properties

of polydeoxyribonucleotide, a popular wound healing booster. Int J

Mol Sci. 17(1448)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Ko IG, Jin JJ, Hwang L, Kim SH, Kim CJ,

Han JH, Lee S, Kim HI, Shin HP and Jeon JW: Polydeoxyribonucleotide

exerts protective effect against CCl4-induced acute

liver injury through inactivation of NF-κB/MAPK signaling pathway

in mice. Int J Mol Sci. 21(7894)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Kim SE, Ko IG, Jin JJ, Hwang L, Kim CJ,

Kim SH, Han JH and Jeon JW: Polydeoxyribonucleotide exerts

therapeutic effect by increasing VEGF and inhibiting inflammatory

cytokines in ischemic colitis rats. Biomed Res Int.

2020(2169083)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Khan A, Wang G, Zhou F, Gong L, Zhang J,

Qi L and Cui H: Polydeoxyribonucleotide: A promising skin

anti-aging agent. Chin J Plast Reconstr Surg. 4:187–193. 2022.

|

|

17

|

Marini HR, Puzzolo D, Micali A, Adamo EB,

Irrera N, Pisani A, Pallio G, Trichilo V, Malta C, Bitto A, et al:

Neuroprotective effects of polydeoxyribonucleotide in a murine

model of cadmium toxicity. Oxid Med Cell Longev.

2018(4285694)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Lee S, Won KY and Joo S: Protective effect

of polydeoxyribonucleotide against CCl4-induced acute

liver injury in mice. Int Neurourol J. 24 (Suppl 2):S88–S95.

2020.

|

|

19

|

Jo S, Baek A, Cho Y, Kim SH, Baek D, Hwang

J, Cho SR and Kim HJ: Therapeutic effects of

polydeoxyribonucleotide in an in vitro neuronal model of

ischemia/reperfusion injury. Sci Rep. 13(6004)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Baek A, Baek D, Kim SH, Kim J, Notario GR,

Lee DW, Kim HJ and Cho SR: Polydeoxyribonucleotide ameliorates

IL-1β-induced impairment of chondrogenic differentiation in human

bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Sci Rep.

14(26076)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Galeano M, Pallio G, Irrera N, Mannino F,

Bitto A, Altavilla D, Vaccaro M, Squadrito G, Arcoraci V, Colonna

MR, et al: Polydeoxyribonucleotide: A promising biological platform

to accelerate impaired skin wound healing. Pharmaceuticals (Basel).

14(1103)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Jung HJ, Cho YW, Lim HW, Choi H, Ji DJ and

Lim CJ: Anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, anti-angiogenic and skin

whitening activities of Phryma leptostachya var. asiatica

Hara extract. Biomol Ther (Seoul). 21:72–78. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Thring TSA, Hili P and Naughton DP:

Anti-collagenase, anti-elastase and anti-oxidant activities of

extracts from 21 plants. BMC Complement Altern Med.

9(27)2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Mandal S, Hazra B, Sarkar R, Biswas S and

Mandal N: Assessment of the antioxidant and reactive oxygen species

scavenging activity of methanolic extract of Caesalpinia

crista leaf. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med.

2011(173768)2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Gharibzahedi SMT, Razavi SH and Mousavi M:

Characterizing the natural

canthaxanthin/2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin inclusion complex.

Carbohydr Polym. 10:1147–1153. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Masuda T, Yamashita D, Takeda Y and

Yonemori S: Screening for tyrosinase inhibitors among extracts of

seashore plants and identification of potent inhibitors from

Garcinia subelliptica. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem.

69:197–201. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Wittenauer J, Mäckle S, Sußmann D,

Schweiggert-Weisz U and Carle R: Inhibitory effects of polyphenols

from grape pomace extract on collagenase and elastase activity.

Fitoterapia. 101:179–187. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Chattuwatthana T and Okello E:

Anti-collagenase, anti-elastase and antioxidant activities of

Pueraria candollei var. mirifica root extract and

Coccinia grandis fruit juice extract: An in vitro study. Eur

J Med Plants. 5:318–327. 2015.

|

|

29

|

Andrés CMC, Pérez de la Lastra JM, Andrés

Juan C, Plou FJ and Pérez-Lebeña E: Superoxide anion chemistry-its

role at the core of the innate immunity. Int J Mol Sci.

24(1841)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Forman HJ and Zhang H: Targeting oxidative

stress in disease: Promise and limitations of antioxidant therapy.

Nat Rev Drug Discov. 20:689–709. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Sharma JN, Al-Omran A and Parvathy SS:

Role of nitric oxide in inflammatory diseases.

Inflammopharmacology. 15:252–259. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Akdeniz N, Aktaş A, Erdem T, Akyüz M and

Özdemir S: Nitric oxide levels in atopic dermatitis. The Pain

Clinic. 16:401–405. 2004.

|

|

33

|

Suschek CV, Feibel D, von Kohout M and

Opländer C: Enhancement of nitric oxide bioavailability by

modulation of cutaneous nitric oxide stores. Biomedicines.

10(2124)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Masum MN, Yamauchi K and Mitsunaga T:

Tyrosinase inhibitors from natural and synthetic sources as

skin-lightening agents. Rev Agric Sci. 7:41–58. 2019.

|

|

35

|

Kim YJ, Kim MJ, Kweon DK, Lim ST and Lee

SJ: Polydeoxyribonucleotide activates mitochondrial biogenesis but

reduces MMP-1 activity and melanin biosynthesis in cultured skin

cells. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 191:540–554. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Squadrito F, Bitto A, Irrera N, Pizzino G,

Pallio G, Minutoli L and Altavilla D: Pharmacological activity and

clinical use of PDRN. Front Pharmacol. 8(224)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Belletti S, Uggeri J, Gatti R, Govoni P

and Guizzardi S: Polydeoxyribonucleotide promotes cyclobutane

pyrimidine dimer repair in UVB-exposed dermal fibroblasts.

Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 23:242–249. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Irrera N, Bitto A, Vaccaro M, Mannino F,

Squadrito V, Pallio G, Arcoraci V, Minutoli L, Ieni A, Lentini M,

et al: PDRN, a bioactive natural compound, ameliorates

imiquimod-induced psoriasis through NF-κB pathway inhibition and

Wnt/β-catenin signaling modulation. Int J Mol Sci.

21(1215)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Echart CL, Graziadio B, Somaini S, Ferro

LI, Richardson PG, Fareed J and Iacobelli M: The fibrinolytic

mechanism of defibrotide: Effect of defibrotide on plasmin

activity. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 20:627–634. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Baker DE and Demaris K: Defibrotide. Hosp

Pharm. 51:847–854. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|