Introduction

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) refers to cardiac

acute ischemic syndrome, caused by thrombosis, resulting from the

rupture or erosion of unstable atheromatous plaques in the coronary

arteries (1). It is classified

into non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), STEMI

and unstable angina pectoris (UA) (1,2). In

clinical settings, UA and NSTEMI present with similar clinical

manifestations and electrocardiographic (ECG) features, such as

ST-segment depressions and T-wave inversion, and are thus together

considered as non-ST-segment-elevation (NSTE)-ACS (3). Both STEMI and NSTEMI are

characterized by myocardial injury or necrosis, typically indicated

by significantly elevated levels of cardiac biomarkers, such as

troponin I (TnI) and troponin T (TnT) (4,5).

Compared with patients with NSTEMI, patients with STEMI more

frequently exhibit complete occlusion of the culprit artery, a

higher incidence of transmural ischemia, a larger infarcted

myocardial area and worse short-term diagnosis compared with

patients with NSTEMI (2).

Globally, STEMI is the single most common cause of

sudden death (4,6). It accounts for 1.8 million deaths

annually (20% of all deaths) in Europe alone, with a decreasing

trend in its relative incidence and a concomitant rise in the

incidence of NSTE-ACS (4).

According to published data, the incidence of ACS varies by age and

sex. In individuals younger than 60 years, ACS occurs 3 to 4 times

more frequently in males than in females, whereas females

constitute the majority of patients over the age of 75(4). The risk of myocardial infarction (MI)

has been extensively studied and numerous factors, including

increased body-mass index, low-density lipoproteins, C-reactive

protein (CRP), diabetes, hypertension, smoking and hyperlipidemia

are regarded as being associated with increased susceptibility to

MI (7,8). Patients typically present with

symptoms such as chest pain, epigastric pain, radiating pain to the

neck or shoulder, and shortness of breath (6,9,10).

Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) has the highest mortality rate

within hours of onset, and early diagnosis and treatment initiation

are key interventions for patients with ACS (6). Notably, the 12-lead ECG and cardiac

troponins (cTn) are the primary diagnostic tools for AMI (6,11).

However, only 5% of patients who present with acute chest pain and

undergo ECG are diagnosed with STEMI (6). In addition, troponin is used to

evaluate NSTE-ACS in patients with chest pain without pre-hospital

ST-segment elevation. Most of these patients are found to have

negative troponin levels and are subsequently diagnosed with

unstable angina, indicating that troponin may not be an optimal

biomarker for NSTE-ACS (6,12).

In clinical practice, patients with suspected ACS

are often directly admitted to emergency departments (EDs). Yet,

the majority of these patients are not ultimately diagnosed with

ACS and could be managed at general care centers to avoid

unnecessary ED congestion, costs and time delays (5,13).

To solve this problem, numerous biomarkers, such as

high-sensitivity cTn (hs-cTn), N-terminal prohormone of brain

natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), hsCRP and D-dimer, have been

clinically applied for risk stratification based on major adverse

cardiac events (MACE), enabling appropriate treatment decisions and

timely, safe discharge (9-12).

In addition, numerous studies have evaluated the diagnostic and

prognostic value of emerging biomarkers, including soluble

suppression of tumorigenicity 2 protein (sST2), which is a

biomarker for cellular stress and injury (14-16),

hs-cTnT, a biomarker of MI (5,9,13)

and lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 (Lp-PLA2), a biomarker

of plaque inflammation (8,10,17),

in the classification and risk stratification of ACS. Elevated

serum levels of sST2 have been shown to independently predict

future heart failure, cardiovascular events and mortality (18), while increased hs-cTnT levels are

associated with a higher risk of MACE (9). Lp-PLA2 has demonstrated limited

utility as a standalone biomarker for cardiovascular events, but it

could offer additional prognostic information when assessed at a

time-point significantly distant from the acute coronary event

(8).

The diagnosis of STEMI and NSTE-ACS determines the

choice and timing of ACS treatment and management (17). However, the diagnostic, prognostic

and classificatory value of reported biomarkers in ACS remains

largely undetermined. Published studies reported inconsistent

results for various kinds of biomarkers in ACS classification. A

total of 11 biomarkers, such as ST2 protein and fibroblast growth

factor, have been reported to exhibit elevated concentrations in

STEMI and NSTEMI, respectively, and may effectively differentiate

between these two MI types. However, these findings lack clinical

reliability due to their reliance on registry data (2). Patients with NSTE-ACS with high sST2

levels had a ~3-fold higher risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD)

and heart failure (HF) compared to patients with STEMI within the

following year (15). The upper

reference limits, as well as age and sex-based thresholds for these

11 biomarkers and other biomarkers in ACS classification is still

uncertain (15,19). Therefore, assessing the performance

of these biomarkers for distinguishing STEMI and NSTEMI is most

important in the management of patients with ACS. Of them, the

hs-cTnT, sST2 and Lp-PLA2 biomarkers are most focused on in

clinical practice; therefore, the present study investigated the

role of these three emerging biomarkers in the classification of

ACS.

Patients and methods

Patients

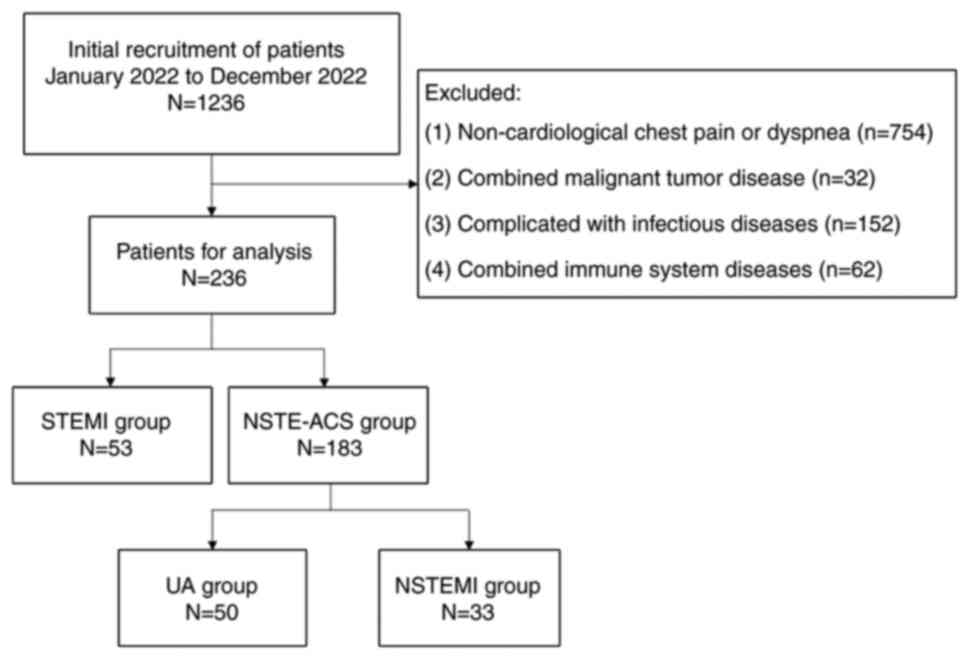

A total of 1,236 patients with suspected ACS

encountered at Nanjing First Hospital (Nanjing, China) between

January 2022 and December 2022 were enrolled in the present study.

Eligible patients were identified according to the following

inclusion and exclusion criteria. The inclusion criterion was

patients suspected of having ACS by clinical doctors based on their

clinical symptoms, such as chest pain and dyspnea. The exclusion

criteria were as follows: i) Non-cardiological chest pain or

dyspnea; ii) combined malignant tumor disease; iii) cases

complicated with infectious diseases; and iv) coexisting immune

system diseases. All coronary angiograms (CAG) were independently

reviewed by two cardiologists and a diagnosis of ACS was

established based on a combination of clinical symptoms, ECG

changes, cardiac biomarkers and CAG findings indicating significant

stenosis (≥50%) in one or more coronary arteries, following the

diagnostic criteria recommended by the European Society of

Cardiology guidelines (20-22).

This retrospective study was approved by the Institutional Review

Board of Nanjing First Hospital (approval no. KY20250714-KS-01),

which waived the requirement for individual patient consent.

Finally, a total of 183 patients (150 with UA and 33 with NSTEMI)

were diagnosed as having NSTE-ACS, and 53 patients were diagnosed

with STEMI. The patient inclusion flow-chart is shown in Fig. 1. Among the 263 patients included,

175 (74.15%) were male and 61 (25.85%) were female. The median age

was 59 years (range, 31-91 years).

Instruments and reagents

Heparin-anticoagulated peripheral blood and serum

samples were collected for hs-cTnT detection, which was detected

with an electrochemiluminescence analyzer (Cobas e411; Roche

Diagnostics) and non-anticoagulated samples were used to obtain

serum for the detection of sST2 and Lp-PLA2 via chemiluminescence

analyzers (CL2000; Beijing Leadman; and 411; Nanjing Norman,

respectively).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS

20.0 software (IBM Corp.). The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to

assess the normality of the measurement data. The measurement data

in accordance with the normal distribution were presented as the

mean ± standard deviation. Student's t-test was used to compare the

groups. Non-normally distributed measurement data were expressed as

the median (interquartile range) and the Mann-Whitney U-test was

used to analyze differences between groups. Enumeration data were

expressed as n (%) and the χ2 test was used for

intergroup comparison. Univariate logistic regression model was

conducted to evaluate the impact of individual factors on ACS

classification. The Hosmer-Lemeshow test was performed to evaluate

the fit of the regression model. Receiver operating characteristic

(ROC) curves were plotted to calculate the diagnostic value of

individual and combined biomarkers for ACS classification.

Furthermore, the DeLong test (23)

was applied to compare the AUCs of different biomarkers. A

two-sided P<0.05 was considered to indicate statistical

significance.

Results

Characteristics of patients

There was a significant difference in gender

distribution between STEMI (males/females=46:7) and NSTE-ACS

(males/females=129:54) cases (χ2=5.697, P=0.017), as

shown in Table I. However, no

significant difference was observed in age between the two groups

(STEMI: 63.60±12.90 years vs. NSTE-ACS: 65.25±11.39 years,

P=0.369). The levels of hs-cTnT [STEMI: median 1,641.00 ng/l

(interquartile range 288.15-4193.50 ng/l) vs. NSTE-ACS: median

17.08 ng/l (interquartile range 9.62-166.10 ng/l), P<0.001;

cut-off value 524 ng/l) and sST2 [STEMI: median 53.17 ng/ml

(interquartile range 28.47-154.87 ng/ml) vs. NSTE-ACS: median 16.92

ng/ml (interquartile range 12.50-25.01), P<0.001; cut-off value

29.27 ng/ml) were significantly higher in the STEMI group compared

to the NSTE-ACS group; however, no significant difference was found

in Lp-PLA2 levels between the two groups [STEMI: median 194.48

ng/ml (interquartile range 141.36-276.59 ng/ml) vs. NSTE-ACS:

median 184.26 ng/ml (interquartile range132.05-259.92), P=0.470],

as shown in Table I.

| Table IComparison of clinical data between

NSTE-ACS group and STEMI group. |

Table I

Comparison of clinical data between

NSTE-ACS group and STEMI group.

| Group | NSTE-ACS | STEMI |

t/χ2 | P-value |

|---|

| Sex

(male/female) | 129/54 | 46/7 | 5.697 | 0.017 |

| Age, years | 65.25±11.39 | 63.60±12.90 | 0.234 | 0.369 |

| hs-cTnT, ng/l | 17.08

(9.62-166.10) | 1641.00

(288.15-4193.50) | -7.989 | <0.001 |

| sST2, ng/ml | 16.92

(12.50-25.01) | 53.17

(28.47-154.87) | -7.369 | <0.001 |

| Lp-PLA2, ng/ml | 184.26

(132.05-259.92) | 194.48

(141.36-276.59) | -0.723 | 0.470 |

Predictive value of hs-cTnT and sST2

in patients with ACS

A univariate logistic regression analysis of the

factors influencing the likelihood that the patient had NSTE-ACS or

STEMI was conducted, with the presence or absence of STEMI as the

dependent variable, and gender, age, hs-cTnT, sST2 and Lp-PLA2 as

the independent variables. The results showed that hs-cTnT [odds

ratio (OR)=1.010, 95% CI: 1.007-1.014] and sST2 (OR=1.022, 95% CI:

1.011-1.033) were predictors of STEMI, as shown in Table II. The Hosmer-Lemeshow test was

performed to evaluate the fit of the regression model and the

result (χ2=11.158, P=0.193) showed no significant

difference between the predicted and observed values, suggesting

that the model fits the data well for classifying the two ACS

groups.

| Table IIResults of a univariate logistic

regression analysis of the factors associated with the risk of

ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction as opposed to

non-ST-segment-elevation acute coronary syndrome. |

Table II

Results of a univariate logistic

regression analysis of the factors associated with the risk of

ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction as opposed to

non-ST-segment-elevation acute coronary syndrome.

| Factor | β | P-value | OR | 95% CI |

|---|

| Sex

(male/female) | 0.242 | 0.675 | 1.273 | 0.412-3.937 |

| Agea | -0.038 | 0.050 | 0.963 | 0.928-1.000 |

|

hs-cTnTa | 0.001 | <0.001 | 1.010 | 1.007-1.014 |

| sST2a | 0.021 | <0.001 | 1.022 | 1.011-1.033 |

|

Lp-PLA2a | -0.002 | 0.312 | 0.998 | 0.995-1.002 |

Diagnostic value of hs-cTnT and sST2

in patients with ACS

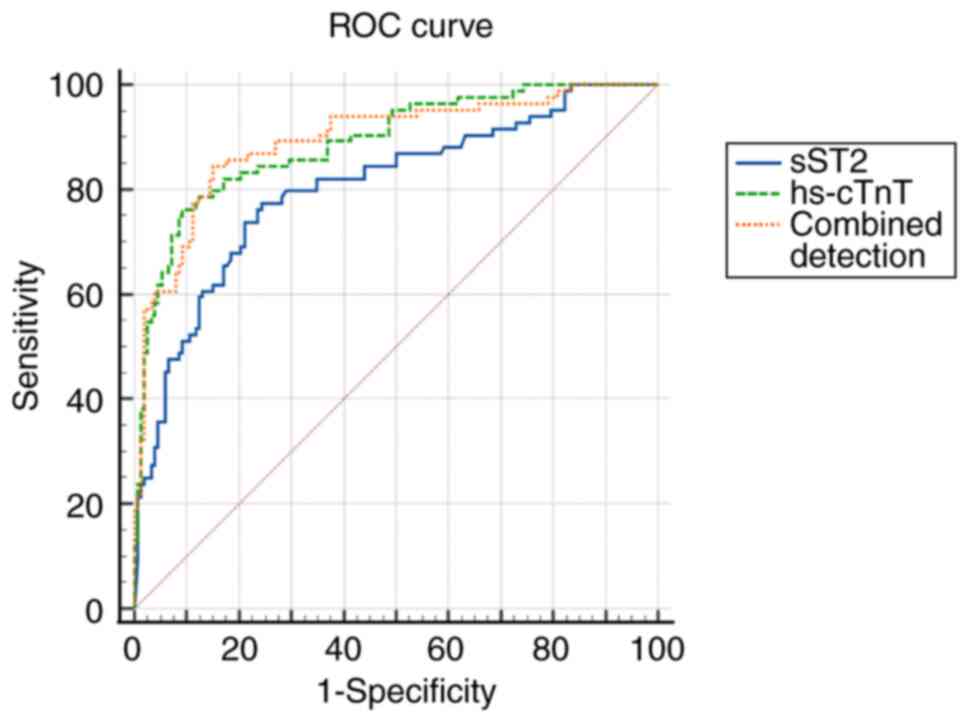

To further assess the diagnostic value of hs-cTnT

and sST2 in distinguishing STEMI from NSTE-ACS, the predictive

values for hs-cTnT and sST2 alone and in combination for

classification of the two ACS groups were assessed, and the results

revealed that hs-cTnT (AUC=0.861, cut-off value=524 ng/l, 95% CI:

0.810-0.902; specificity: 88.52%; sensitivity: 71.70%), sST2

(AUC=0.833, cut-off value=29.27 ng/ml, 95% CI: 0.779-0.878;

specificity: 83.06%, sensitivity: 75.47%) and their combination

(AUC=0.863, 95% CI: 0.812-0.904; specificity: 91.80%, sensitivity:

71.70%) could serve as diagnostic biomarkers for STEMI, as shown in

Table III and Fig. 2. Additionally, the diagnostic

efficacy of hs-cTnT (AUC=0.861, P=0.0017) and the combination of

hs-cTnT and sST2 (AUC=0.863, P<0.005) was higher than that of

sST2 alone (AUC=0.833).

| Table IIIDiagnostic value of combined

detection of hs-cTnT and sST2 to distinguish ST-segment elevation

myocardial infarction from non-ST-segment-elevation acute coronary

syndrome. |

Table III

Diagnostic value of combined

detection of hs-cTnT and sST2 to distinguish ST-segment elevation

myocardial infarction from non-ST-segment-elevation acute coronary

syndrome.

| Variable | Cut-off value | Youden index | Sensitivity, % | Specificity, % | AUC | 95% CI | AUC P |

|---|

| hs-cTnT | 524 ng/l | 0.6022 | 71.70 | 88.52 | 0.861 | 0.810-0.902 | 0.0017 |

| sST2 | 29.27 ng/ml | 0.5853 | 75.47 | 83.06 | 0.833 | 0.779-0.878 | - |

| Combined

detection | - | 0.6350 | 71.70 | 91.80 | 0.863 | 0.812-0.904 | <0.005 |

Discussion

The present retrospective study indicated that both

sST2 and hs-cTnT demonstrated significant utility in

differentiating between STEMI and NSTE-ACS, while Lp-PLA2 was not a

valuable biomarker for the classification of the two types of MI.

We observed that the circulating levels of hs-cTnT were 96-fold

higher in STEMI than that in NSTE-ACS, providing a cut-off value of

524 ng/l to discriminate between the types of MIs. Moreover, the

serum levels of sST2 were 3-fold higher in STEMI than in NSTE-ACS,

and it could accurately classify the two types of ACS with a

cut-off value of 29.27 ng/ml. Of note, hs-cTnT and its combination

with sST2 outperformed sST2 alone in terms of diagnostic efficiency

in patients with ACS and combined detection of the two markers did

not improve the biomarkers' ability to distinguish between the two

types of ACS as compared to hs-cTnT alone.

Over decades of standardized cardiovascular disease

prevention in developed countries, the incidence of STEMI has

decreased significantly, while China has shown a rapid growth trend

(24,25). Similar to the present findings,

numerous studies have reported higher cases of STEMI in males

(63-67%) than in females (30-37%) (26,27).

This difference may be due to risk factors such as smoking,

diabetes, dyslipidemia, abdominal obesity and hypertension, which

are more prevalent in males (28).

In addition, estrogen hormone in females offers a temporary

premenopausal vascular protection, delaying the onset and severity

of atherosclerosis in women contrary to men, though this protection

declines post-menopause, allowing for the later onset of ACS events

in women. In contrast to the present results, NSTE-ACS has been

reported to be predominantly higher in females (29,30),

likely due to a higher incidence of diffuse coronary artery

disease, microvascular dysfunction and older age at ACS

presentation, factors less frequently associated with STEMI's

characteristic vessel occlusion (31). These sex-based epidemiological

patterns underscore the necessity of gender-tailored strategies for

ACS prevention, diagnosis and management.

Various guidelines and expert consensus affirm the

diagnostic and therapeutic value of myocardial markers, including

creatine kinase isoenzyme and myoglobin (CK-MB), cTnT, cTnI,

heart-type fatty acid binding protein, myosin binding protein C and

NT-proBNP, in ACS pathophysiology and guiding risk stratification

(5,14,32).

Despite the critical need to accurately and safely rule out STEMI

in patients with NSTE-ACS, the discriminative value of these

biomarkers is still unclear. The present study focused on

evaluating hs-cTnT, sST2 and Lp-PLA2 for ACS classification. The

results indicated that both hs-cTnT and sST2, individually and in

combination, effectively predicted STEMI, whereas Lp-PLA2 showed no

utility in ACS classification.

Stimulation expression gene 2 (ST2), a member of the

interleukin (IL)-1 receptor family, interacts specifically with and

IL-33 (15,16,18).

It exists mainly in 2 isoforms: ST2 and ST2L, which is divided into

transmembrane forms, and sST2 (14,18).

sST2 is a marker of stress and injury of cardiomyocytes (14,15),

whose high expression in serum has been reported to independently

predict HF, CVD events and death in both STEMI and NSTE-ACS

(14,16,18).

Numerous studies suggest that sST2, as a marker reflecting

myocardial fibrosis, inflammation and oxidative stress, is helpful

for risk stratification and prognostic evaluation of patients with

HF (33,34). For the application of sST2 in the

diagnosis of ACS, the present study established that the biomarker

had 3-fold higher expression in STEMI than NSTE-ACS, which is

similar to the findings reported by Hjort et al (2). This higher level of sST2 in STEMI is

attributed to the greater degree of myocardial damage and

dysfunction compared to NSTE-ACS (2,15).

However, Hjort et al (2)'s

conclusions were based on registry data and non-quantitative assays

with no absolute concentration measurements, limiting direct

comparison with the clinically applied cut-offs. Importantly, the

present study was conducted using clinical patient's results taken

from the hospital's database, enabling for sST2 clinical comparison

and STEMI prediction with a cut-off value of 29.27 ng/ml

(sensitivity: 75.47%, specificity: 83.06%).

cTnI and -T are proteins that are implicated in

actin-myosin interaction, produced and released by cardiomyocytes

due to stress or necrosis (35);

their elevated levels in peripheral blood indicate cardiomyocyte

damage (12,36) and are reported to be more sensitive

and specific markers of cardiomyocyte injury than CK, its CK-MB and

myoglobin, which was once considered the gold standard for

myocardial injury (19). However,

conventional cTn assays have the drawback of delayed elevation and

require serial sampling over 6-9 h, limiting their sensitivity at

AMI presentation (19,25). hs-cTn assays were developed to

detect low cTn concentrations at or below concentrations

corresponding to the 99th percentile value of a normal reference

population to enable the diagnosis of an ongoing myocardial injury

in stable patients and even seemingly healthy populations (19). Giannitsis et al (7) also found that the evaluation of

hs-cTnT was a more accurate approach for troponin detection in

patients with NSTE-ACS than the conventional cTnT or -I assay. In

the present study, a 96-fold higher median value of hs-cTnT in

STEMI than in NSTE-ACS was observed, which can be associated with

the higher incidence of transmural ischemia and a larger area of

infarction in STEMI that increase cardiomyocyte stress, producing

more hs-cTnT in response than in patients with NSTE-ACS (2,35,37).

hs-cTnT, when used alone and in combination with sST2 showed higher

potential to discriminate STEMI compared with sST2 alone. Although

the combined model yielded a numerically higher AUC than hs-cTnT

alone (0.863 vs. 0.861), DeLong's test showed no statistically

significant difference (P=0.849). The estimated ΔAUC (0.002)

indicates that any incremental discrimination, if present, is

likely very small. Detecting such a modest effect generally

requires substantially larger sample sizes and event counts than

those yielded in the present study. Accordingly, the current

analysis may be underpowered and the absence of statistical

significance should not be overinterpreted as evidence of no

effect. Future work with larger cohorts and/or external validation

is warranted to clarify whether the addition of variables to

hs-cTnT provides statistically and clinically meaningful

improvement.

Lp-PLA2 is a biomarker of plaque inflammation whose

circulating levels are associated with changes in coronary plaque

volume (10,17). It has been shown that there is a

link between Lp-PLA2 levels and the severity of coronary artery

disease (38). Zhao et al

(39) concluded that a higher

serum Lp-PLA2 activity level is associated with a more severe

degree of coronary artery disease. Similarly, a study by Möckel

et al (12) revealed that

Lp-PLA2 is an effective independent marker for risk stratification,

which proved to be superior to CRP and the Thrombolysis in

Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) risk score (12). Lp-PLA2 was reportedly higher in

NSTE-ACS than STEMI (40), but its

sensitivity and specificity in differentiating between the two ACS

subtypes was relatively low (41).

Similarly, in the present study, there was no significant

difference in Lp-PLA2 serum levels between STEMI and NSTE-ACS,

showing low discriminative power. These findings indicate that

Lp-LPA2 is only a biomarker of atherosclerotic burden and chronic

vascular inflammation rather than acute plaque rupture or

myocardial injury, which are critical in distinguishing between

STEMI and NSTE-ACS (40,41); hence, it is not an applicable

marker in ACS classification.

To the best of our knowledge, the present study is

the first retrospective cohort study demonstrating the potential of

hs-cTnT and sST2 to discriminate between STEMI and NSTE-ACS, both

independently and in combination. However, despite these remarkable

findings, the present study has certain limitations. As a

single-center retrospective study, it may be subject to inherent

biases and limited external validity. No adjustments were made for

sociodemographic factors, clinical characteristics or medication

use, which may affect the absolute diagnostic power. Notably, this

study focused solely on the etiologic classification of ACS and the

findings were independent of disease severity. Although NSTE-ACS is

clinically diagnosed, the severity of individual cases may vary

depending on baseline health conditions. Hence, treatment

strategies should be tailored according to risk stratification,

which can be guided by established risk scoring systems, such as

the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events risk score and the

TIMI risk score (42,43). In addition, a larger sample size or

an external validation cohort would be required to confirm whether

the observed modest incremental value is statistically significant.

Therefore, multicenter studies with larger sample sizes may be

recommended to validate the present findings, with or without

adjustments for potential confounding factors.

In conclusion, the present findings indicate that

cardiac biomarkers, including hs-cTnT and sST2, either individually

or in combination, can effectively distinguish patients with STEMI

from those with NSTE-ACS.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: This work was supported by the Jiangsu Provincial

Medical Key Discipline Cultivation Unit (grant no. JSDW202239) and

Nanjing Medical Key Laboratory of Laboratory Diagnostics.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

YW was responsible for software, data collection and

writing the manuscript. NL participated in data curation and

manuscript writing. CS contributed to data collection and

manuscript writing. BH participated in conception, design, and

critical review of the manuscript. YPM performed formal analysis

and acquired funding. HP designed the study and revised the

manuscript. HP and YPM confirmed the authenticity of the raw data.

All authors have read and approved the final version of the

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The Ethics Committee of Nanjing First Hospital

(Nanjing, China) approved this study (approval no.

KY20250714-KS-01).

Patient consent for publication

As this was a retrospective study, patient consent

for inclusion was waived.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Rubini Gimenez M, Thiele H and Pöss J:

Management of acute coronary syndrome without ST-segment elevation.

Herz. 47:381–392. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar : (In German).

|

|

2

|

Hjort M, Eggers KM, Lindhagen L, Baron T,

Erlinge D, Jernberg T, Marko-Varga G, Rezeli M, Spaak J and Lindahl

B: Differences in biomarker concentrations and predictions of

long-term outcome in patients with ST-elevation and

non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Clin Biochem. 98:17–23.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Braunwald E and Morrow DA: Unstable

angina: Is it time for a requiem? Circulation. 127:2452–2457.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, Antunes MJ,

Bucciarelli-Ducci C, Bueno H, Caforio ALP, Crea F, Goudevenos JA,

Halvorsen S, et al: 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute

myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment

elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute myocardial

infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the

European society of cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 39:119–177.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Sandeman D, Syed MBJ, Kimenai DM, Lee KK,

Anand A, Joshi SS, Dinnel L, Wenham PR, Campbell K, Jarvie M, et

al: Implementation of an early rule-out pathway for myocardial

infarction using a high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T assay. Open

Heart. 8(e001769)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Ishak M, Ali D, Fokkert MJ, Slingerland

RJ, Dikkeschei B, Tolsma RT, Lichtveld RA, Bruins W, Boomars R,

Bruheim K, et al: Fast assessment and management of chest pain

without ST-elevation in the pre-hospital gateway: rationale and

design. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 4:129–136.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Giannitsis E, Garfias-Veitl T, Slagman A,

Searle J, Müller C, Blankenberg S, von Haehling S, Katus HA, Hamm

CW, Huber K, et al: Biomarkers-in-cardiology 8

RE-VISITED-consistent safety of early discharge with a dual marker

strategy combining a normal hs-cTnT with a normal copeptin in

low-to-intermediate risk patients with suspected acute coronary

syndrome-A secondary analysis of the randomized

biomarkers-in-cardiology 8 trial. Cells. 11(211)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

O'Donoghue M, Morrow DA, Sabatine MS,

Murphy SA, McCabe CH, Cannon CP and Braunwald E:

Lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 and its association with

cardiovascular outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndromes

in the PROVE IT-TIMI 22 (PRavastatin Or atorVastatin evaluation and

infection therapy-thrombolysis in myocardial infarction) trial.

Circulation. 113:1745–1752. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Inoue K, Chieh JTW, Yeh LC, Chiang SJ,

Phrommintikul A, Suwanasom P, Kasim S, Ahmad B, Idrose AM, Salleh

FM, et al: An international, stepped wedge, cluster-randomized

trial investigating the 0/1-h algorithm in suspected acute coronary

syndrome in Asia: The rational of the DROP-Asian ACS study. Trials.

23(986)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Möckel M, Danne O, Müller R, Vollert JO,

Müller C, Lueders C, Störk T, Frei U, Koenig W, Dietz R and Jaffe

AS: Development of an optimized multimarker strategy for early risk

assessment of patients with acute coronary syndromes. Clin Chim

Acta. 393:103–109. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Morawiec B, Kawecki D, Przywara-Chowaniec

B, Opara M, Muzyk P, Ho L, Tat LC, Gabrysiak A, Muller O and

Nowalany-Kozielska E: Copeptin as a prognostic marker in acute

chest pain and suspected acute coronary syndrome. Dis Markers.

2018(6597387)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Möckel M, Müller R, Vollert J, Müller C,

Danne O, Gareis R, Störk T, Dietz R and Koenig W:

Lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 for early risk

stratification in patients with suspected acute coronary syndrome:

A multi-marker approach: The North Wuerttemberg and Berlin

infarction study-II (NOBIS-II). Clin Res Cardiol. 96:604–612.

2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

van Cauteren YJM, Smulders MW, Theunissen

RALJ, Gerretsen SC, Adriaans BP, Bijvoet GP, Mingels AMA, van Kuijk

SMJ, Schalla S, Crijns HJGM, et al: Cardiovascular magnetic

resonance accurately detects obstructive coronary artery disease in

suspected non-ST elevation myocardial infarction: A sub-analysis of

the CARMENTA trial. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 23(40)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Dhillon OS, Narayan HK, Khan SQ, Kelly D,

Quinn PA, Squire IB, Davies JE and Ng LL: Pre-discharge risk

stratification in unselected STEMI: is there a role for ST2 or its

natural ligand IL-33 when compared with contemporary risk markers?

Int J Cardiol. 167:2182–2188. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Kohli P, Bonaca MP, Kakkar R, Kudinova AY,

Scirica BM, Sabatine MS, Murphy SA, Braunwald E, Lee RT and Morrow

DA: Role of ST2 in non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome in the

MERLIN-TIMI 36 trial. Clin Chem. 58:257–266. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Sabatine MS, Morrow DA, Higgins LJ,

MacGillivray C, Guo W, Bode C, Rifai N, Cannon CP, Gerszten RE and

Lee RT: Complementary roles for biomarkers of biomechanical strain

ST2 and N-terminal prohormone B-type natriuretic peptide in

patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Circulation.

117:1936–1944. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Dohi T, Miyauchi K, Okazaki S, Yokoyama T,

Ohkawa R, Nakamura K, Yanagisawa N, Tsuboi S, Ogita M, Yokoyama K,

et al: Decreased circulating lipoprotein-associated phospholipase

A2 levels are associated with coronary plaque regression in

patients with acute coronary syndrome. Atherosclerosis.

219:907–912. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Januzzi JL Jr: ST2 as a cardiovascular

risk biomarker: From the bench to the bedside. J Cardiovasc Transl

Res. 6:493–500. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Wang J, Tan GJ, Han LN, Bai YY, He M and

Liu HB: Novel biomarkers for cardiovascular risk prediction. J

Geriatr Cardiol. 14:135–150. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, Gardner RS,

Baumbach A, Böhm M, Burri H, Butler J, Čelutkienė J, Chioncel O, et

al: 2021 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute

and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 42:3599–3726.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Visseren FLJ, Mach F, Smulders YM,

Carballo D, Koskinas KC, Bäck M, Benetos A, Biffi A, Boavida JM,

Capodanno D, et al: 2021 ESC guidelines on cardiovascular disease

prevention in clinical practice: Developed by the Task Force for

cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice with

representatives of the European society of cardiology and 12

medical societies with the special contribution of the European

association of preventive cardiology (EAPC). Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl

Ed). 75(429)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Lapostolle F, Loyeau A, Bataille S, Boche

T, Le Bail G, Weisslinger L, Juliard JM and Lambert Y: New European

society of cardiology guidelines for the management of patients

with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: Effect on physician's

compliance and patient's outcome. Eur J Emerg Med. 26:380–381.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

DeLong ER, DeLong DM and Clarke-Pearson

DL: Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver

operating characteristic curves: A nonparametric approach.

Biometrics. 44:837–845. 1988.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Du X, Patel A, Anderson CS, Dong J and Ma

C: Epidemiology of cardiovascular disease in China and

opportunities for improvement: JACC international. J Am Coll

Cardiol. 73:3135–3147. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Dalal JJ, Ponde CK, Pinto B, Srinivas CN,

Thomas J, Modi SK, Mehta S, Shetty S, Manimarane and Desai

B: Time to shift from contemporary to high-sensitivity cardiac

troponin in diagnosis of acute coronary syndromes. Indian Heart J.

68:851–855. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Duraes AR, Bitar YS, Freitas ACT, Filho

IM, Freitas BC and Fernandez AM: Gender differences in ST-elevation

myocardial infarction (STEMI) time delays: Experience of a public

health service in Salvador-Brazil. Am J Cardiovasc Dis. 7:102–107.

2017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Kuehnemund L, Koeppe J, Feld J, Wiederhold

A, Illner J, Makowski L, Gerß J, Reinecke H and Freisinger E:

Gender differences in acute myocardial infarction-A nationwide

German real-life analysis from 2014 to 2017. Clin Cardiol.

44:890–898. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Akbar H and Mountfort S: Acute ST-segment

elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). In: StatPearls. StatPearls

Publishing LLC. Treasure Island, FL, 2025.

|

|

29

|

Al-Assadi MY, Aljaber NN, Al-Habeet A, Al

Nono O and Al-Motarreb A: Sex-related differences in acute coronary

syndrome: Insights from an observational study in a Yemeni cohort.

Front Cardiovasc Med. 12(1481917)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Soeiro AM, Silva PGMBE, Roque EAC, Bossa

AS, Biselli B, Leal TCAT, Soeiro MCFA, Pitta FG, Serrano CV Jr and

Oliveira MT Jr: Prognostic differences between men and women with

acute coronary syndrome. Data from a Brazilian registry. Arq Bras

Cardiol. 111:648–653. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Sári C, Heesch CM, Kovács AJ and Andréka

P: Sex-related differences in care and prognosis in acute coronary

syndrome. Prev Med Rep. 55(103131)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Kavsak PA, Shortt C, Ma J, Clayton N,

Sherbino J, Hill SA, McQueen M, Mehta SR, Devereaux PJ and Worster

A: A laboratory score at presentation to rule-out serious cardiac

outcomes or death in patients presenting with symptoms suggestive

of acute coronary syndrome. Clin Chim Acta. 469:69–74.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Aimo A, Januzzi JL Jr, Bayes-Genis A,

Vergaro G, Sciarrone P, Passino C and Emdin M: Clinical and

prognostic significance of sST2 in heart failure: JACC review topic

of the week. J Am Coll Cardiol. 74:2193–2203. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Sanada S, Hakuno D, Higgins LJ, Schreiter

ER, McKenzie AN and Lee RT: IL-33 and ST2 comprise a critical

biomechanically induced and cardioprotective signaling system. J

Clin Invest. 117:1538–1549. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Stătescu C, Anghel L, Tudurachi BS, Leonte

A, Benchea LC and Sascău RA: From classic to modern prognostic

biomarkers in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Int J Mol

Sci. 23(9168)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Badimon L, Romero JC, Cubedo J and

Borrell-Pagès M: Circulating biomarkers. Thromb Res. 130 (Suppl

1):S12–S15. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Smulders MW, Kietselaer BLJH, Wildberger

JE, Dagnelie PC, Brunner-La Rocca HP, Mingels AMA, van Cauteren

YJM, Theunissen RALJ, Post MJ, Schalla S, et al: Initial

imaging-guided strategy versus routine care in patients with

non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol.

74:2466–2477. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Zhang H, Gao Y, Wu D and Zhang D: The

relationship of lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 activity

with the seriousness of coronary artery disease. BMC Cardiovasc

Disord. 20(296)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Zhao SQ, Chang H and Zhang L: Correlation

between the level of lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2

activity in serum, the degree of coronary artery ste-nosis and

major adverse cardiovascular events in patients with coronary heart

disease. Chin J Lab Diagn. 1:1621–1624. 2021.

|

|

40

|

Verdoia M, Rolla R, Gioscia R, Rognoni A

and De Luca G: Novara Atherosclerosis Study Group (NAS).

Lipoprotein associated-phospholipase A2 in STEMI vs NSTE-ACS

patients: a marker of cardiovascular atherosclerotic risk rather

than thrombosis. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 56:37–44. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Chung H, Kwon HM, Kim JY, Yoon YW, Rhee J,

Choi EY, Min PK, Hong BK, Rim SJ, Yoon JH, et al:

Lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 is related to

plaque stability and is a potential biomarker for acute coronary

syndrome. Yonsei Med J. 55:1507–1515. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Gale CP, Stocken DD, Aktaa S, Reynolds C,

Gilberts R, Brieger D, Carruthers K, Chew DP, Goodman SG, Fernandez

C, et al: Effectiveness of GRACE risk score in patients admitted to

hospital with non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome (UKGRIS):

Parallel group cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ.

381(e073843)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Neumann FJ and Sousa-Uva M: ‘Ten

commandments’ for the 2018 ESC/EACTS guidelines on myocardial

revascularization. Eur Heart J. 40:79–80. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|