Introduction

Lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) is the most prevalent

subtype of lung cancer and according to statistics reported in

2024, LUAD continues to rank among the leading malignancies in both

incidence and mortality worldwide. In the United States, LUAD

accounted for ~45% of lung cancers in 2021, with an age-adjusted

incidence of ~22 per 100,000 population (1). For example, recent advances include

low-dose computed tomography screening that reduces lung-cancer

mortality, and precision therapies such as EGFR-targeted

osimertinib (with or without chemotherapy), RET inhibitors

(selpercatinib), KRAS p.G12C inhibitors (sotorasib), and immune

checkpoint blockade (pembrolizumab-based chemoimmunotherapy).

Despite notable progress in diagnostic and therapeutic strategies,

such as low-dose CT screening, EGFR-targeted therapy and immune

checkpoint inhibitors, the 5-year survival rate for LUAD remains

poor at ~15-20% (2,3). With the rapid development of

high-throughput sequencing and bioinformatics, researchers can now

systematically identify key molecular targets related to tumor

initiation and progression at the genomic level (4-6);

however, precise therapeutic targets for LUAD are still

lacking.

In addition to genetic and transcriptomic

characterization, advances in nanotechnology and biomolecular

engineering have introduced new opportunities for improving LUAD

diagnosis and treatment. For example, macrophage-mediated

sulfate-based nanomedicine has demonstrated enhanced drug delivery

efficacy within the tumor microenvironment of lung cancer (7), whilst nano-assisted radiotherapy

strategies have shown potential in increasing treatment precision

and efficacy in non-small cell lung cancer (8). Furthermore, self-assembled DNA-based

biosensors have enabled rapid and portable detection of circulating

tumor cells in lung cancer patient blood samples (n=46), achieving

100% specificity and 86.5% sensitivity, supporting early diagnosis

and disease monitoring in lung cancer (9). These technological innovations

underscore the need to explore molecular-level biomarkers that

could complement or integrate with such novel platforms to improve

clinical outcomes in LUAD.

The present study employed integrated bioinformatics

tools and machine learning algorithms and conducted in

silico validation using independent GEO (GSE31210 discovery;

GSE68465 validation) and TCGA-LUAD cohorts, as well as molecular

validation by reverse transcription-quantitative (RT-q) PCR on

paired LUAD and adjacent normal tissues (n=50) to identify and

validate potential therapeutic targets for LUAD, with the aim to

providing a foundation for future targeted treatment

strategies.

Materials and methods

Identification of differentially

expressed genes (DEGs)

A total of two LUAD-related datasets, GSE31210 and

GSE68465(10), were retrieved from

the GEO database (11), in which

the control samples comprised non-tumorous normal lung tissues

rather than patient-matched adjacent tissues (GSE31210: 20 normal,

226 LUAD; GSE68465: 19 normal, 443 LUAD); these datasets were

chosen for their large sample sizes, availability of normal

controls, and rich clinical annotation (including overall

survival), making them widely used benchmark cohorts for discovery

(GSE31210) and external validation (GSE68465). DEGs were identified

using the ‘limma’ R package (v3.60.6, Bioconductor), implemented in

R v4.4.1 (www.r-project.org/foundation/) (12), with screening criteria set as

|log2fold change|>1 and P<0.05. Volcano plots were

generated using the ‘EnhancedVolcano’ package for visualization

(13).

Weighted gene co-expression network

analysis (WGCNA)

WGCNA was performed on the GSE31210 dataset using

the ‘WGCNA’ R package (14),

because this dataset contains both tumor and normal samples with

comprehensive clinical annotation and a sufficiently large sample

size, making it suitable for constructing reliable co-expression

networks to identify key gene modules associated with LUAD. A

soft-thresholding power β=6 was chosen based on the scale-free

topology criterion (scale-free R²>0.85). The minimum module size

was set to 30 to ensure module robustness. The resulting sample

dendrogram and trait heatmap are presented in Fig. S1. Modules with a Pearson

correlation coefficient of r>0.92 and P<0.05 were considered

statistically significant, with correlations evaluated between

module eigengenes and clinical traits (such as tumor vs. normal

status, stage), measured from the sample annotation of the GSE31210

dataset.

Gene set enrichment analysis

(GSEA)

GSEA was performed using GSEA software (v4.3.2)

(15) on the entire set of DEGs,

whereas Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and

Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analyses were performed using the

‘clusterProfiler’ R package (v4.12.0; www.r-project.org/foundation/) (16,17)

on the same DEG set. GO analysis included biological process,

cellular components and molecular functions. KEGG analysis was used

to identify significantly enriched signaling pathways. P<0.05

and q<0.05 were considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Construction and analysis of the

protein-protein interaction (PPI) network

Identified DEGs were submitted to the STRING

database to construct a PPI network (18), with a confidence score threshold of

>0.9 (high confidence). Interaction data were imported into

Cytoscape (v3.10.0; https://cytoscape.org/) for visualization. Network

topology was analyzed using two centrality algorithms: Degree

Centrality and Betweenness Centrality (19).

Machine learning analysis

A total of two machine learning algorithms were

applied: Random Forest (RF) and Support Vector Machine-Recursive

Feature Elimination (SVM-RFE) (20,21).

RF analysis was performed using the ‘randomForest’ package

(v4.7-1.2) in R v4.4.1 (www.r-project.org/foundation/), and feature importance

was ranked accordingly according to the default feature importance

measures implemented in the ‘randomForest’ R package (Mean Decrease

Accuracy and Mean Decrease Gini, as recommended by the package

developers). SVM-RFE analysis was performed using the ‘e1071’

package (v1.7-14) in R v4.4.1 (www.r-project.org/foundation/) to further select

optimal features based on gene importance. A linear kernel was

applied with the default cost parameter (C=1), and feature ranking

was performed using 10-fold cross-validation. The gene subset

corresponding to the lowest cross-validated classification error

was selected as the optimal feature set. P<0.05 was considered

to indicate a statistically significant difference.

RT-qPCR

RT-qPCR (22) was

used to validate the expression levels of caveolin-1 (CAV1) and

cadherin 5 (CDH5) in tumor and adjacent normal tissues from 50

patients with LUAD, with adjacent tissues collected at least 5 mm

away from the tumor margin. All tissue specimens were collected

during surgical resection at Hebei Provincial Hospital of

Traditional Chinese Medicine (Shijiazhuang, China) between May 2021

and June 2023, immediately snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and

stored at -80˚C until RNA extraction. Among the patients, 28 were

male and 22 were female. Inclusion criteria were

histopathologically confirmed LUAD and availability of paired tumor

and adjacent normal tissues; exclusion criteria included prior

chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or other malignancies. The median age

was 63 years (range, 45-78 years). The study protocol was approved

by the Ethics Committee of Hebei Provincial Hospital of Traditional

Chinese Medicine (Shijiazhuang, China; approval no.

HBZY2023-KY-076-01) and followed the ethical principles of The

Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from

all participants.

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol®

reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), and RNA purity and

concentration were assessed using a NanoDrop 2000

spectrophotometer. High-quality RNA was reverse transcribed into

cDNA, and qPCR was performed using SYBR Green PCR Master Mix on a

QuantStudio 6 Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.). Relative gene expression was calculated using the

2-ΔΔCq method (22),

with GAPDH used as the internal control. Primers were designed and

validated using Primer-BLAST. The following primer sequences were

used: GAPDH forward, 5'-AATGGACAACTGGTCGTGGAC-3' and reverse,

5'-CCCTCCAGGGGATCTGTTTG-3'; CAV1 forward,

5'-GCAGAACCAGAAGGGACACAG-3' and reverse,

5'-CCAAAGAGGGCAGACAGCAAGC-3'; and CDH5 forward,

5'-AGGTGCTAACCCTGCCCAAC-3' and reverse,

5'-CGGAAGACCTTGCCCACATA-3'.

Receiver operating characteristic

(ROC) curve analysis

ROC curve analysis was performed using the ‘pROC’

package (v1.18.5) in R v4.4.1 (www.r-project.org/foundation/) (23). An area under the curve (AUC) of

>0.9 was considered to indicate notable diagnostic performance.

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq)

analysis

scRNA-seq data related to LUAD were obtained from

the Tumor Immune Single Cell Hub (TISCH) database (http://tisch.comp-genomics.org) (24). The expression levels of key genes

across different cell types were visualized using heatmaps and

feature plots, which were generated directly from the TISCH

database portal based on preprocessed single-cell RNA-seq data

provided by the database.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad

Prism 9.0 (Dotmatics). Differences between tumor and normal tissues

in The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and GEO datasets were assessed

using unpaired Student's t-test, while differences between matched

tumor and adjacent normal tissues in the clinical validation cohort

and paired comparisons within the TCGA cohort (Fig. 3D) were assessed using paired

Student's t-test. For comparisons among multiple subgroups, one-way

ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test was applied. Kaplan-Meier

survival analysis was performed using the Kaplan-Meier Plotter

database (http://kmplot.com/analysis/) based on

TCGA-LUAD data; patients were stratified into high- and

low-expression groups using the median expression value as the

cut-off, and statistical significance was evaluated using the

log-rank test. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

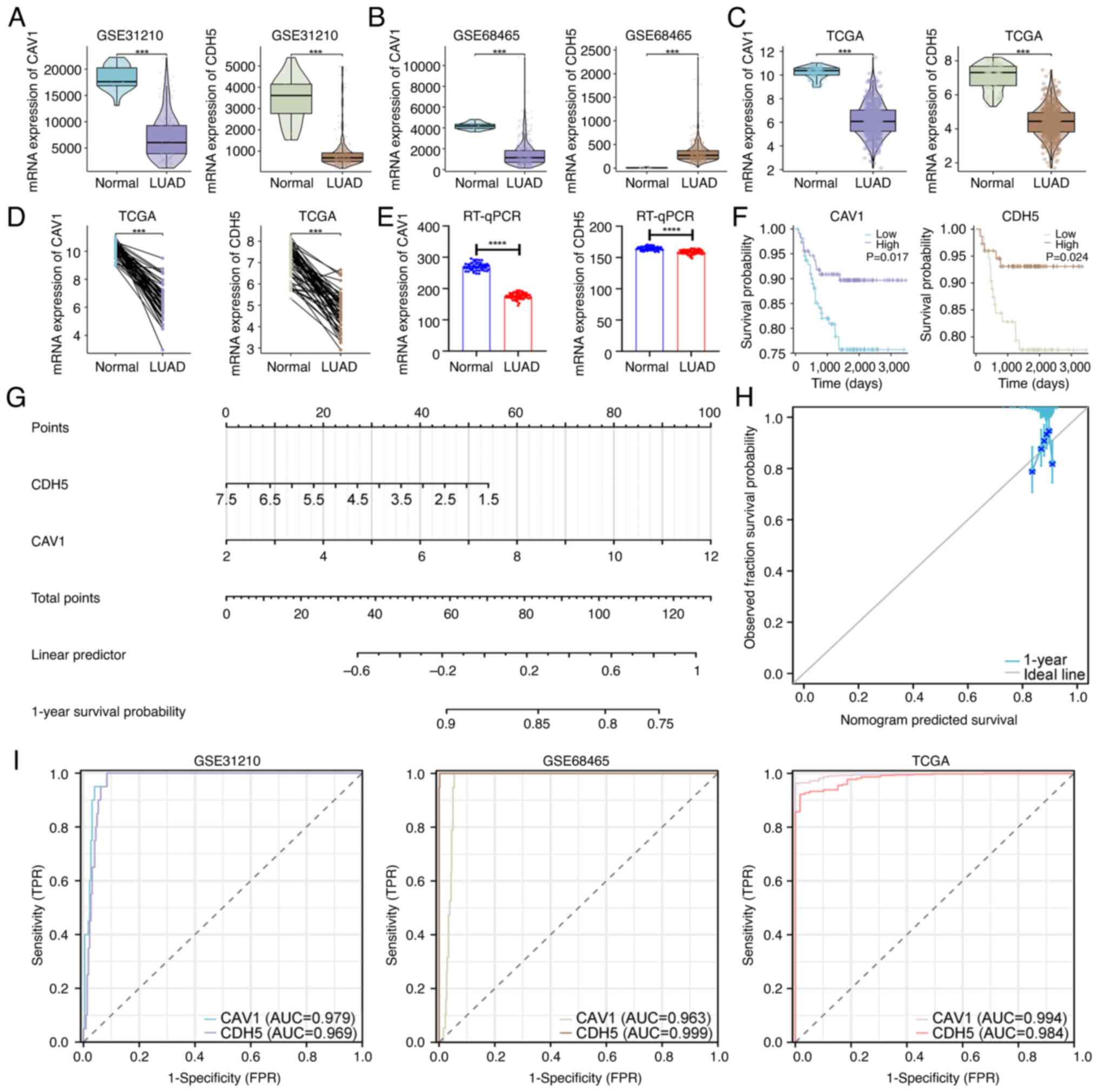

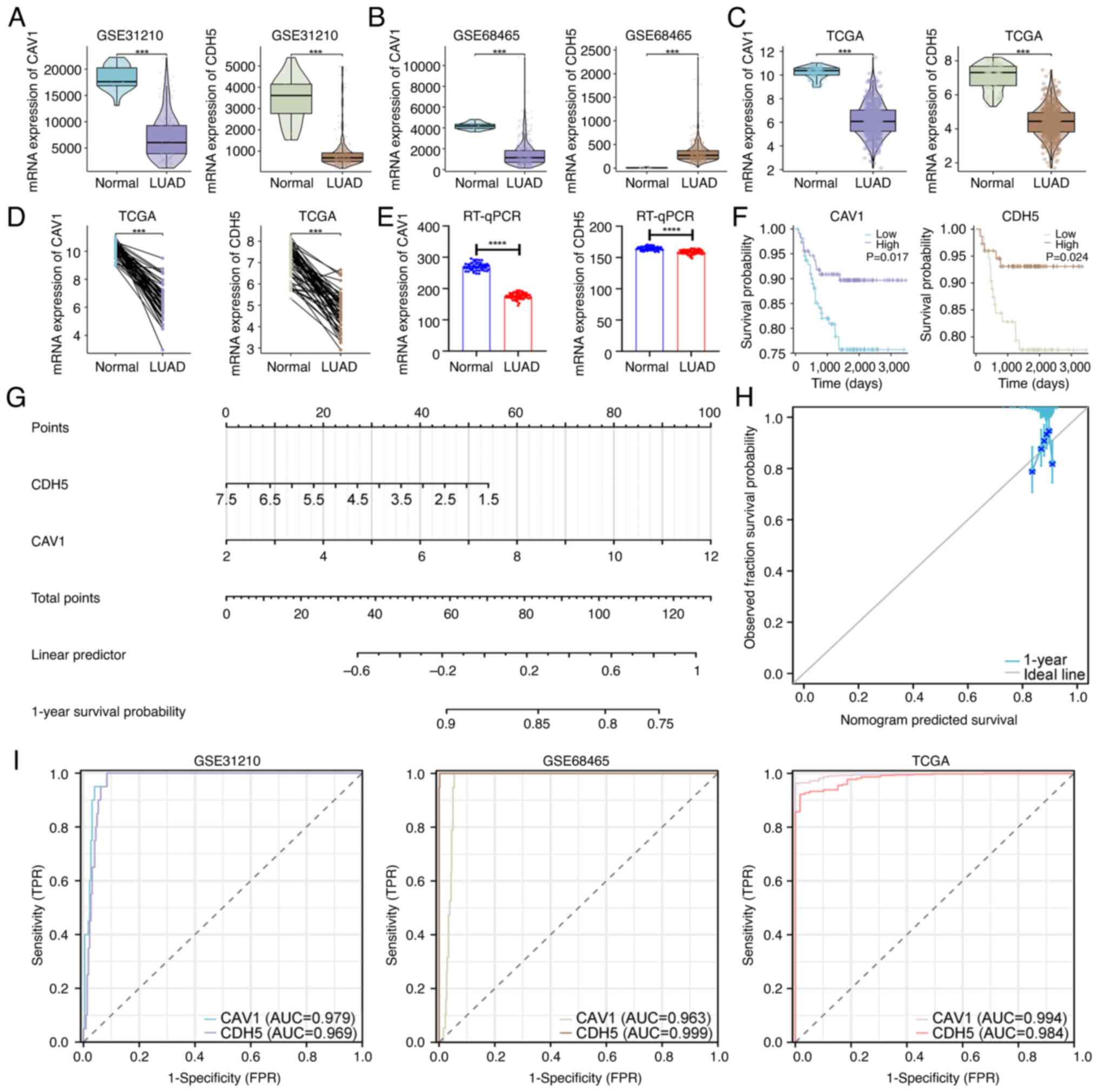

| Figure 3Expression and prognostic analysis of

key genes. Expression of CAV1 and CDH5 in the (A) GSE31210, (B)

GSE68465 and (C) TCGA datasets. (D) Paired expression analysis of

CAV1 and CDH5 in TCGA samples. (E) RT-qPCR validation in tissues

from patients with LUAD (n=50). (F) Kaplan-Meier survival curves

for CAV1 and CDH5, comparing patients with high expression and low

expression (grouped according to the median expression level).

P-values were calculated using the log-rank test. (G) Diagnostic

nomogram based on CAV1 and CDH5. (H) Calibration curve evaluating

nomogram accuracy. (I) Receiver operating characteristic curve

analysis in the GSE31210, GSE68465 and TCGA datasets.

***P<0.001 and ****P<0.0001. CAV1,

caveolin-1; CDH5, cadherin 5; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas;

RT-qPCR, reverse transcription-quantitative PCR; LUAD, lung

adenocarcinoma; AUC, area under the curve; TRP, true positive rate;

FRP, false positive rate. |

Results

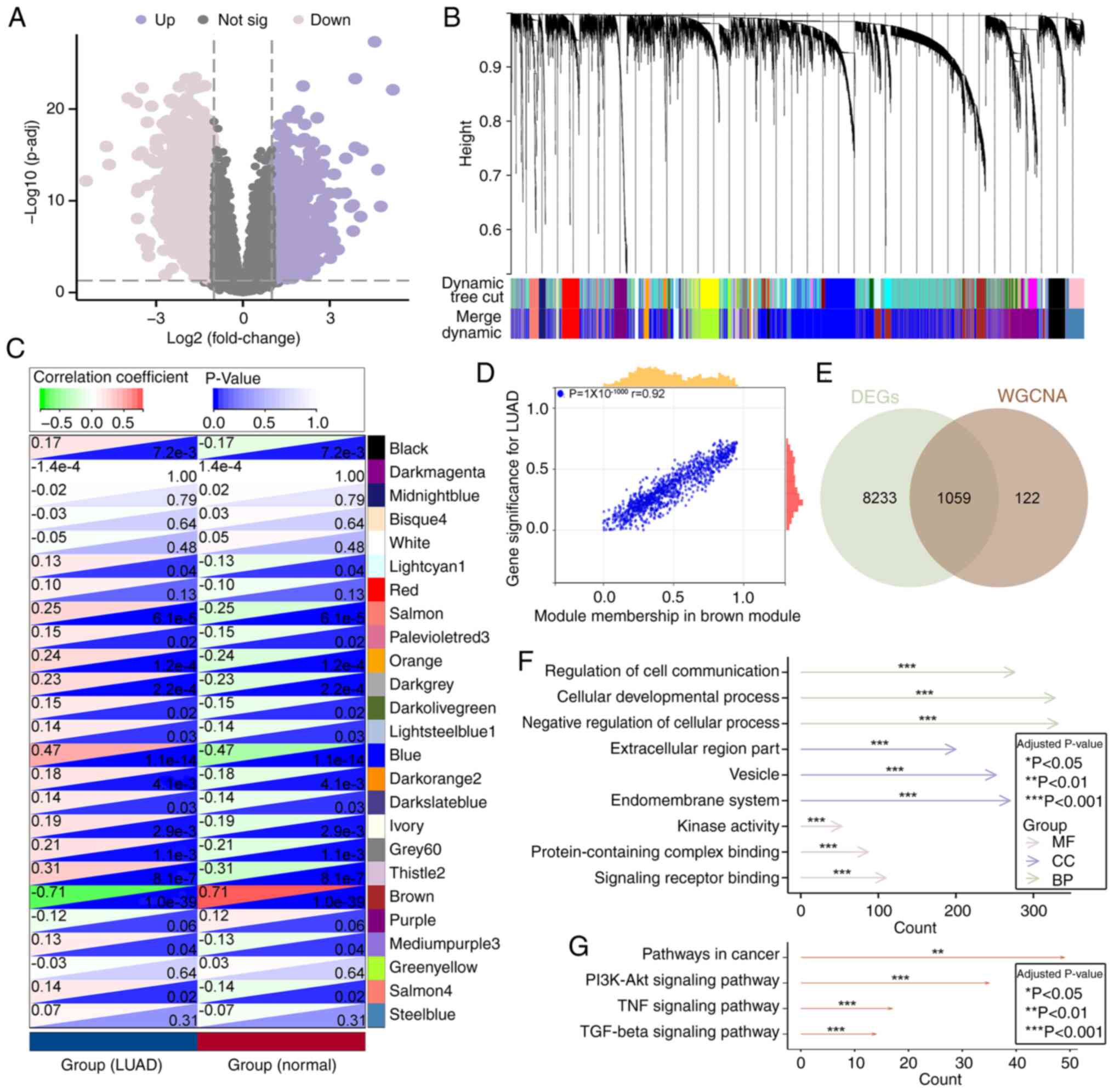

Identification of overlapping genes

between DEGs and key WGCNA modules

Based on the GSE31210 dataset, a total of 9,292 DEGs

were identified, including 5,399 upregulated and 3,893

downregulated genes in LUAD tumor tissues compared with controls,

as this dataset contains both tumor and non-tumor lung tissues with

comprehensive clinical annotation, making it suitable for DEG

identification. A volcano plot was generated to visualize these

DEGs (Fig. 1A). To further

identify key genes, a WGCNA was performed using the same dataset,

resulting in the identification of 25 co-expression modules

(Fig. 1B).

Correlation analysis between these modules and LUAD

phenotypes revealed that 17 modules were significantly associated

with LUAD, among which the brown module showed the strongest

correlation (Fig. 1C). This

suggested that this module may serve a critical role in the

pathogenesis and progression of LUAD. Further scatter plot analysis

of module membership and gene significance demonstrated a strong

positive correlation within the brown module (Pearson's r=0.92,

P=1x10-1,000), indicating its relevance as a key module

(Fig. 1D).

Subsequently, a Venn diagram was used to identify

overlapping genes between DEGs and those in the key module

identified by WGCNA, resulting in 1,059 common genes (Fig. 1E). GO and KEGG enrichment analyses

were then performed on these overlapping genes. GO analysis

revealed enrichment in signaling-related molecular functions such

as ‘signaling receptor binding’, ‘kinase activity’ and

‘protein-containing complex binding’, cellular components such as

‘vesicle’, ‘endomembrane system’ and ‘extracellular region part’,

as well as biological processes such as ‘regulation of cell

communication’, ‘cellular developmental process’ and ‘negative

regulation of cellular process’ (Fig.

1F). KEGG analysis revealed significant enrichment in ‘TGF-β

signaling pathway’, ‘TNF signaling pathway’, ‘PI3K-Akt signaling

pathway’ and ‘pathways in cancer’, suggesting that these genes may

serve regulatory roles in LUAD initiation and progression (Fig. 1G).

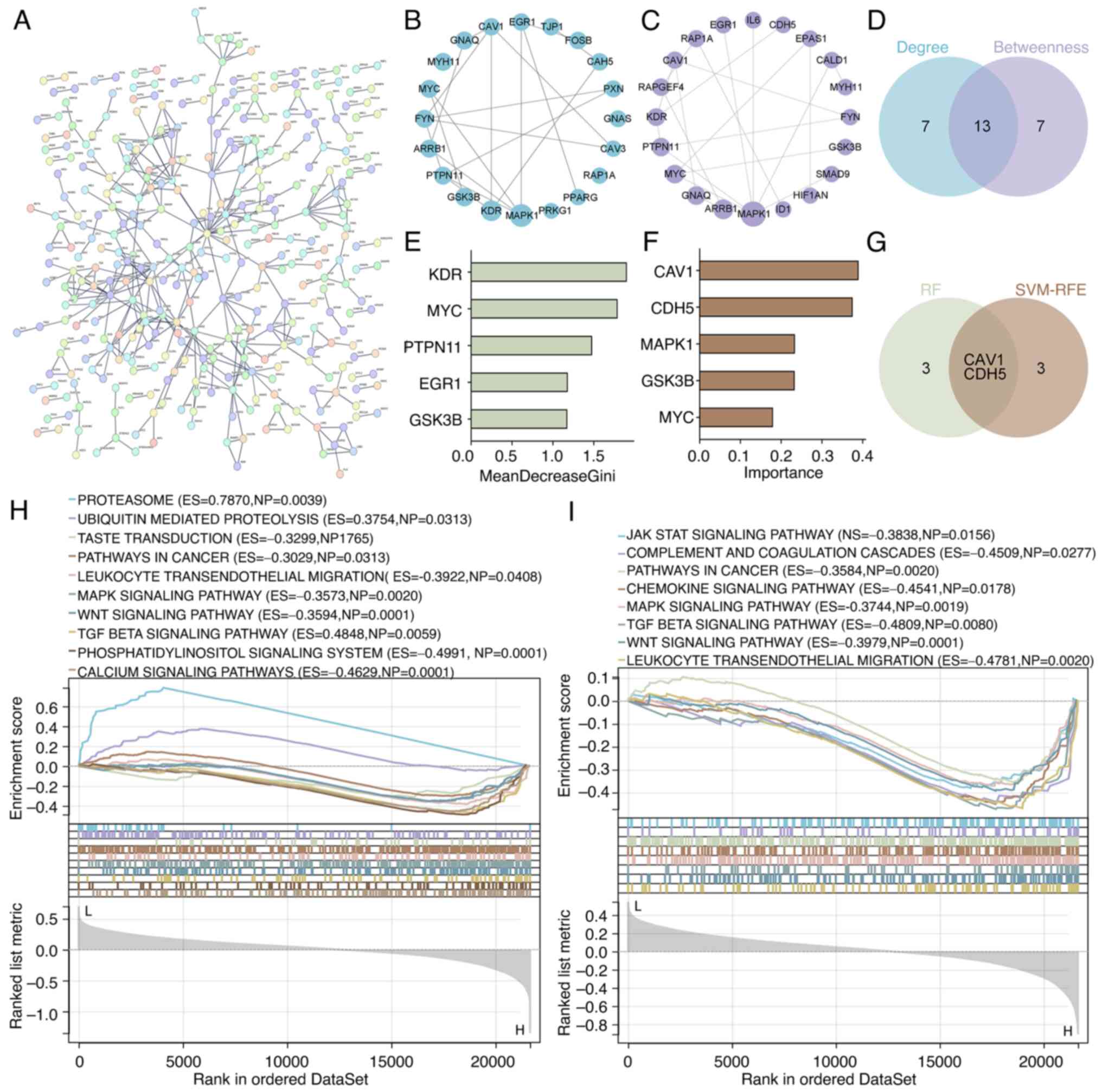

Identification of key LUAD genes based

on PPI network and machine learning

A PPI network was constructed using the 1,059

overlapping genes (Fig. 2A).

Topological analysis in Cytoscape using the Degree Centrality and

Betweenness Centrality algorithms identified the top 20 hub genes

(Fig. 2B and C, respectively). The intersection of

these two analyses yielded 13 shared hub genes (Fig. 2D).

Subsequently, two machine learning approaches, RF

and SVM-RFE, were employed to further refine key gene selection.

The RF algorithm identified the top five genes based on feature

importance scores (Fig. 2E),

whereas SVM-RFE selected another top five genes through iterative

optimization (Fig. 2F). A Venn

diagram analysis of both methods identified two overlapping

candidate genes: CAV1 and CDH5 (Fig.

2G).

Furthermore, GSEA indicated that both CAV1 and CDH5

were significantly enriched in signaling pathways such as MAPK, Wnt

and TGF-β, suggesting their involvement in LUAD development,

progression and modulation of the tumor immune microenvironment

(Fig. 2H and I).

Expression analysis and prognostic

model construction of key genes

To explore the roles of CAV1 and CDH5 in LUAD, their

expression levels were analyzed in the GSE31210 dataset. Both genes

were significantly downregulated in LUAD tissues compared with

those in normal tissues (Fig. 3A).

Moreover, consistent downregulation trends were observed in the

GSE68465 and TCGA datasets for CAV1 (Fig. 3B and C). Although CDH5 expression was

upregulated in the LUAD tissues in the GSE68465 dataset, it was

downregulated in the TCGA cohort. To further investigate whether

tumor stage contributes to this inter-dataset discrepancy, a

subgroup analysis was performed using the GSE68465 dataset,

stratifying patients by N stage (N0, N1 and N2). As shown in

Fig. S2, CDH5 expression was

significantly higher in N0-stage samples compared with that in N1

(P<0.001) and a significant difference was also observed between

N1 and N2 (P<0.05). This stage-associated decline supports a

biological trend of progressive CDH5 downregulation during LUAD

advancement.

Pairwise analyses in the TCGA dataset demonstrated

significantly lower expression of CAV1 and CDH5 in LUAD tissues

compared with available adjacent normal lung tissues, eliminating

potential interference from inter-individual biological variation

(Fig. 3D). Similarly, RT-qPCR

results from 50 LUAD samples demonstrated significantly decreased

expression levels of CAV1 and CDH5 in tumor tissues compared with

those in matched adjacent normal tissues (P<0.0001; Fig. 3E). Notably, although the difference

in CDH5 expression between tumor and control tissues was relatively

small in magnitude, it remained statistically significant. This

expanded validation supports the reliability and reproducibility of

the bioinformatics-driven identification of these genes.

Furthermore, Kaplan-Meier survival analysis revealed

that high expression of CAV1 and CDH5 was significantly associated

with improved overall survival, suggesting that CAV1 and CDH5 have

potential tumor suppressor functions (Fig. 3F). A diagnostic nomogram model

based on the expression of CAV1 and CDH5 was then constructed

(Fig. 3G), with calibration curves

indicating strong agreement between predicted and actual outcomes,

as the calibration curves closely overlapped with the ideal 45˚

reference line (Fig. 3H). In

addition, ROC curve analysis demonstrated notable diagnostic

performance for CAV1 (AUC=0.979) and CDH5 (AUC=0.969) in GSE31210,

and this was validated in both GSE68465 and TCGA datasets (Fig. 3I), supporting the potential of CAV1

and CDH5 as diagnostic biomarkers for LUAD.

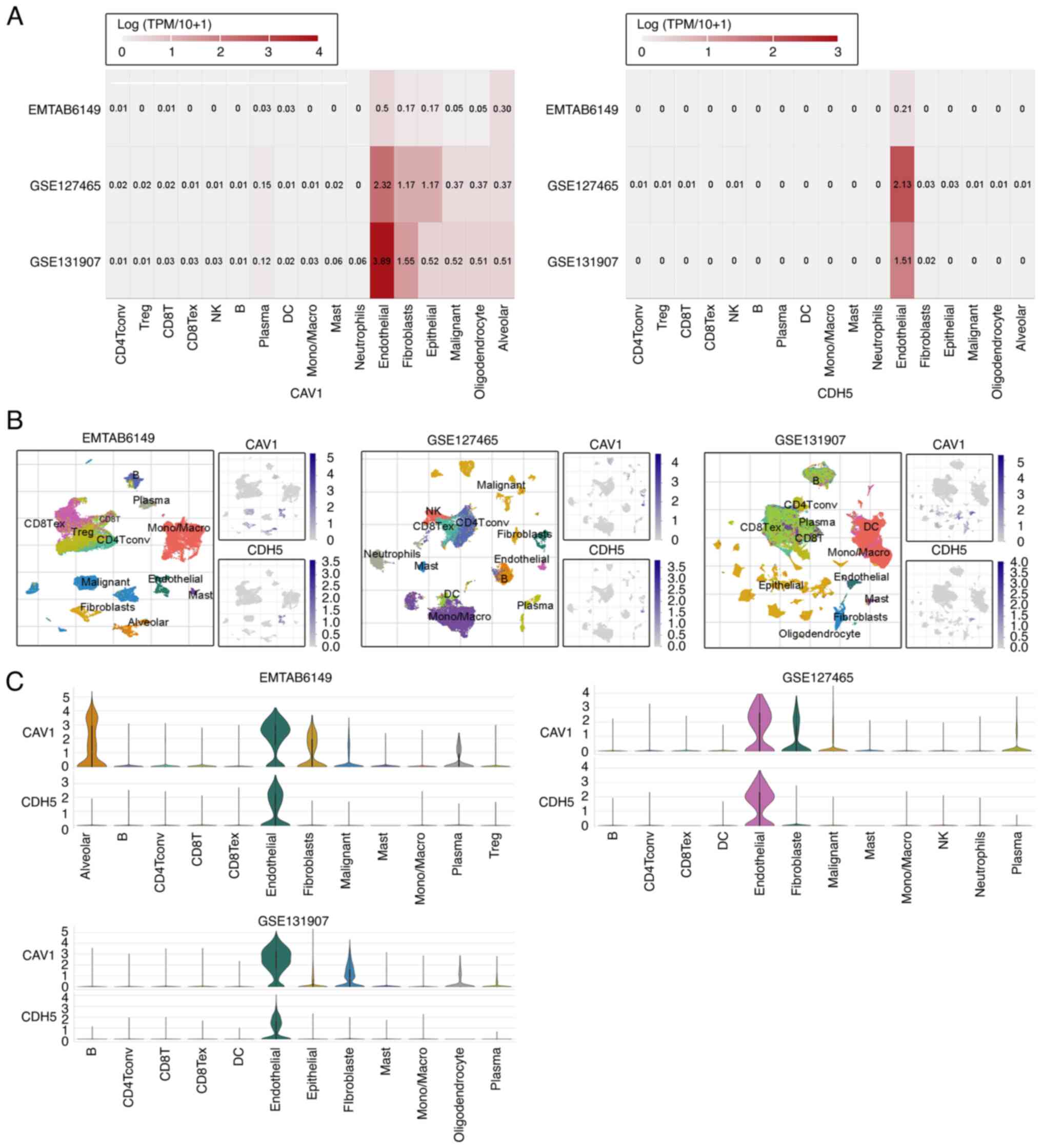

Expression features of key genes in

single-cell transcriptomics

To precisely characterize the cell-type-specific

expression and potential functions of CAV1 and CDH5, three

LUAD-related scRNA-seq datasets (EMTAB6149, GSE127465 and

GSE131907) from the TISCH database were analyzed: EMTAB6149

includes ~20,000 cells in total from the primary LUAD tissues of 4

patients; GSE127465 comprises ~14,000 cells in total from

surgically resected LUAD tumors and adjacent tissues from 7

patients; and GSE131907 includes ~208,506 cells in total derived

from 11 patients with LUAD. These datasets represent a diverse

range of LUAD microenvironments and provide robust resolution of

immune and stromal cell populations. Both genes were revealed to be

highly expressed in endothelial cells (Fig. 4A), suggesting potential roles in

tumor-associated angiogenesis, vascular barrier maintenance or

microenvironment regulation. To visualize their spatial expression

across immune cell subpopulations, t-distributed stochastic

neighbor embedding plots were generated for CAV1 and CDH5, which

showed that both genes were predominantly expressed in endothelial

cell clusters, with lower expression observed in other immune cell

subtypes (Fig. 4B). Additionally,

violin plots were used to quantify expression levels across major

cell types, revealing marked heterogeneity in gene expression

patterns, with CAV1 and CDH5 showing higher expression in

endothelial cells but minimal expression in most immune cell

subsets, indicating substantial variability across cell populations

(Fig. 4C). These findings not only

corroborate the high expression observed in heatmaps, particularly

in endothelial cells, but also highlight the complexity of gene

regulation in the tumor microenvironment, providing a theoretical

basis for further functional studies.

Discussion

LUAD exhibits notable heterogeneity in terms of its

molecular characteristics, cellular composition, and clinical

behavior, posing ongoing challenges for both diagnosis and targeted

therapy (25). The present study

systematically identified key genes participating in LUAD, namely

CAV1 and CDH5, through integrated differential expression analysis

across multiple GEO and TCGA datasets, WGCNA, PPI network topology

screening and dual machine learning algorithms. The expression

profiles and potential functions of these genes in LUAD were then

further explored.

CAV1 is a scaffolding protein involved in membrane

signal integration, cytoskeletal remodeling and tumor-suppressive

signal transduction, and has been implicated in LUAD proliferation,

migration and mechanisms of drug resistance (26). CDH5 (coding for VE-cadherin) is an

endothelial cell-specific adhesion molecule that maintains vascular

integrity and participates in tumor angiogenesis and immune evasion

(27). In the context of LUAD

progression, the downregulation of CAV1 and CDH5 may actively

contribute to tumor aggressiveness through multiple mechanisms.

CAV1, a structural component of caveolae, is known to regulate

membrane-associated signaling and actin cytoskeleton dynamics

(28). Its loss has been

associated with the activation of the MAPK/ERK and Wnt/β-catenin

pathways, both of which are implicated in promoting

epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), increased motility and the

metastatic capacity of LUAD cells (29). CAV1 downregulation also facilitates

invadopodia formation, enabling extracellular matrix degradation

and local invasion (30).

Furthermore, loss of CDH5 expression has been associated with

enhanced invasiveness in several cancers, including breast, gastric

and colorectal cancers, as demonstrated in a recent pan-cancer

analysis (31). In the present

study, survival analysis demonstrated that high expression of both

CAV1 and CDH5 was significantly associated with improved overall

survival, suggesting the tumor-suppressive roles of these genes in

LUAD.

CDH5/VE-cadherin serves a critical role in

maintaining endothelial junctional integrity (32), and reduced CDH5 expression in LUAD

may disrupt the vascular endothelial barrier, thereby increasing

vascular permeability and promoting tumor cell intravasation into

the bloodstream. This mechanism supports distant metastasis and has

been associated with enhanced extravasation and colonization at

secondary sites (33).

Furthermore, loss of CDH5 expression may impair immune surveillance

by altering leukocyte transmigration, thereby contributing to the

formation of an immune-privileged tumor niche, characterized by

reduced immune cell infiltration and evasion from host immune

responses (34). These effects

highlight the functional importance of CAV1 and CDH5 beyond their

diagnostic value, further supporting their role as potential

therapeutic targets in LUAD. Additionally, a diagnostic nomogram

model constructed based on these two genes exhibited strong

predictive accuracy. ROC analysis across multiple independent

datasets also demonstrated robust diagnostic potential of CAV1 and

CDH5, supporting their reliability as candidate molecular

biomarkers for LUAD. While CDH5 expression was found to be

upregulated in the GSE68265 dataset, this trend was not replicated

in other independent datasets. To explore whether clinical staging

may account for this discrepancy, a subgroup analysis stratified by

N stage was performed using the GSE68465 cohort. The results

demonstrated a significant stepwise decline in CDH5 expression from

N0 to N2 stages, supporting a stage-dependent downregulation

pattern. This finding aligns with the trends observed in the TCGA

dataset and the RT-qPCR validation cohort conducted in the present

study. Taken together, these data suggest that CDH5 downregulation

is a consistent feature in LUAD progression, and that isolated

inter-dataset variability may be attributable to sample

composition, stromal content or platform-specific differences.

These observations underscore the importance of integrating

stratified analysis in biomarker evaluation to mitigate confounding

effects and enhance biological interpretability.

In terms of underlying mechanisms, GSEA revealed

that CAV1 and CDH5 were significantly enriched in key signaling

pathways, including MAPK, Wnt and TGF-β. These pathways are known

to be involved in cell proliferation, migration, metastasis and

immune regulation in LUAD (35-37).

CAV1 generally acts as an inhibitor of the MAPK/ERK and

Wnt/β-catenin pathways, while loss of CDH5 function disrupts

endothelial junctions and facilitates pro-tumorigenic signaling,

thereby highlighting their tumor-suppressive roles. Notably, the

activation of MAPK and Wnt signaling has been reported to promote

tumor cell growth and maintain cancer stemness (38), whereas the TGF-β pathway in LUAD

has shown stage-dependent effects, exhibiting tumor-suppressive

roles in early stages but promoting EMT and metastasis in later

stages (39).

Further analysis of single-cell transcriptomic data

revealed that CAV1 and CDH5 are predominantly expressed in

endothelial cells, suggesting the hypothesis that they may be

involved in maintaining endothelial function (40), regulating tumor-associated

angiogenesis and contributing to the formation of the immune

barrier. A recent study has reported that dysfunction of tumor

endothelial cells is associated with abnormal vascularization,

immune escape and distant metastasis, which is consistent with the

findings of the present study (41). Although these processes were not

directly investigated in the present study, such associations can

be hypothesized based on the enriched terms and pathways identified

in the bioinformatics analysis, which are consistent with the

findings of the previous report. Whilst this endothelial-specific

expression pattern suggests a possible involvement in angiogenic

regulation, this inference is based on gene localization and prior

biological evidence rather than direct functional association. In

the current study, the proportion of endothelial subclusters

expressing CAV1 or CDH5 were not quantified, and associations with

angiogenesis-related signatures or histological vessel density were

not assessed. Therefore, future studies integrating these analyses

will be necessary to confirm the functional roles of these genes in

LUAD-associated angiogenesis.

From a clinical standpoint, the incorporation of

CAV1 and CDH5 into diagnostic workflows may hold promising

translational potential. Given their consistent differential

expression between LUAD and normal tissues, both genes could be

evaluated using immunohistochemistry on formalin-fixed

paraffin-embedded lung biopsy specimens, allowing pathologists to

assess protein levels directly in tumor samples. Alternatively,

emerging liquid biopsy techniques, such as detection of circulating

tumor RNA or protein in plasma, could potentially enable the

non-invasive, dynamic monitoring of these biomarkers during disease

progression or treatment response. Although CAV1 and CDH5 are

cytoskeleton-associated proteins and are unlikely to be secreted

directly, their dysregulation may still be detected indirectly

through circulating tumor RNA or extracellular vesicles. A study

demonstrated the feasibility of liquid biopsy for monitoring

molecular alterations in patients with LUAD (42). Although further validation is

necessary, particularly at the protein and clinical implementation

level, the findings of the present study provide a rationale for

the future development of CAV1 and CDH5 as clinically useful

biomarkers in LUAD diagnosis and patient management.

Furthermore, whilst the nomogram and ROC analyses in

the present study demonstrated notable diagnostic performance for

CAV1 and CDH5, these results were derived from datasets with

limited clinical covariates and without multivariate survival

adjustment. In particular, the Kaplan-Meier survival curves were

based on univariate analysis and did not account for potential

confounders, such as tumor stage, patient age or treatment

modalities. Similarly, although multiple datasets were used for

validation, the high AUC values may partially reflect

dataset-specific characteristics or overfitting. Therefore, future

studies incorporating multivariate Cox regression analysis, larger

prospective cohorts and bootstrap or external validation frameworks

will be necessary to confirm the independent clinical utility of

these biomarkers.

In addition, whilst the expression levels of CAV1

and CDH5 were validated at the mRNA level in an expanded clinical

cohort, there was a lack of protein-level validation and

histological confirmation of cell-type specificity within LUAD

tissues. Future studies involving immunohistochemical staining and

spatial transcriptomic profiling will be required to fully

elucidate the functional roles and cellular localization of CAV1

and CDH5.

In summary, CAV1 and CDH5 appear to have notable

biological roles in LUAD and may serve as promising targets for

diagnosis and therapy. A limitation of the present study is that it

focused on bioinformatics integration and clinical validation and

did not include in vitro or in vivo functional

experiments. However, the consistent expression patterns of CAV1

and CDH5 across multiple datasets and RT-qPCR analysis support

their tumor-suppressive potential. Mechanistic validation, such as

gene knockdown or overexpression studies in LUAD models, should be

performed in future research to further elucidate the functional

roles and therapeutic implications of these genes.

In conclusion, the present study systematically

identified CAV1 and CDH5 as potential key tumor-suppressor genes in

LUAD. Both genes were significantly downregulated in tumor tissues

and associated with a favorable patient prognosis. The diagnostic

model based on their expression demonstrated a notable predictive

performance. Moreover, single-cell transcriptomic analysis

highlighted the specific expression of CAV1 and CDH5 in endothelial

cells, suggesting their potential involvement in the regulation of

the tumor microenvironment. These findings provide a theoretical

basis and novel molecular targets for the diagnosis and targeted

treatment of LUAD.

Supplementary Material

Sample clustering dendrogram and

phenotype heatmap for the GSE31210 dataset. Hierarchical clustering

was performed using average linkage and Euclidean distance. The

lower color bar represents clinical phenotype classification

(purple, LUAD; blue, normal tissue). The dendrogram and heatmap

confirm consistency between sample grouping and phenotype labels

and indicate no obvious outliers. This visualization supports the

reliability of subsequent module-trait correlation analyses. LUAD,

lung adenocarcinoma.

CDH5 mRNA expression in patients with

lung adenocarcinoma from the GSE68465 dataset, stratified by lymph

node metastasis status (N stage). CDH5 expression was significantly

higher in N0-stage samples compared with that in N1 (P<0.001)

and a significant difference was also observed between N1 and N2

(P<0.05). *P<0.05 and ***P<0.001.

CDH5, cadherin 5.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present study was funded by the Research Project of

the Hebei Provincial Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine

(grant nos. 2020103 and 2022065).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

LZ conceived and designed the study, developed the

methodology and drafted the manuscript. YW contributed to software

implementation, validation and project administration. YuL

performed formal analysis, participated in data acquisition and

interpretation and contributed to securing funding. YaL conducted

experimental investigation and provided essential resources

(clinical samples and reagents). LW curated the data, performed

statistical analysis and visualization. CW contributed to the study

conception and manuscript writing, reviewing and editing. LZ and CW

confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and

approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of

Hebei Provincial Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine (approval

no. HBZY2023-KY-076-01). Written informed consent was obtained from

all participants.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Siegel RL, Giaquinto AN and Jemal A:

Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:12–49.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

He T, Li J, Wang P and Zhang Z: Artificial

intelligence predictive system of individual survival rate for lung

adenocarcinoma. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 20:2352–2359.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Lin JJ, Cardarella S, Lydon CA, Dahlberg

SE, Jackman DM, Jänne PA and Johnson BE: Five-year survival in

EGFR-mutant metastatic lung adenocarcinoma treated with EGFR-TKIs.

J Thorac Oncol. 11:556–565. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Sogbe M, Aliseda D, Sangro P, de la

Torre-Aláez M, Sangro B and Argemi J: Prognostic value of

circulating tumor DNA in different cancer types detected by

ultra-low-pass whole-genome sequencing: A systematic review and

patient-level survival data meta-analysis. Carcinogenesis.

16(bgae073)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Leong IUS, Cabrera CP, Cipriani V, Ross

PJ, Turner RM, Stuckey A, Sanghvi S, Pasko D, Moutsianas L, Odhams

CA, et al: Large-scale pharmacogenomics analysis of patients with

cancer within the 100,000 genomes project combining whole-genome

sequencing and medical records to inform clinical practice. J Clin

Oncol. 43:682–693. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Larsson L, Corbett C, Kalmambetova G,

Utpatel C, Ahmedov S, Antonenka U, Iskakova A, Kadyrov A, Kohl TA,

Barilar V, et al: Whole-genome sequencing drug susceptibility

testing is associated with positive MDR-TB treatment response. Int

J Tuberc Lung Dis. 28:494–499. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Liu C, Chen Y, Xu X, Yin M, Zhang H and Su

W: Utilizing macrophages missile for sulfate-based nanomedicine

delivery in lung cancer therapy. Research (Wash D C).

7(0448)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Zhao L, Li M, Shen C and Luo Y, Hou X, Qi

Y, Huang Z, Li W, Gao L, Wu M and Luo Y: Nano-assisted radiotherapy

strategies: New opportunities for treatment of non-small cell lung

cancer. Research (Wash D C). 7(0429)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Wang Y, Shen C, Wu C, Zhan Z, Qu R, Xie Y

and Chen P: Self-assembled DNA machine and selective complexation

recognition enable rapid homogeneous portable quantification of

lung cancer CTCs. Research (Wash D C). 7(0352)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Zhao Z, Zhao D, Xia J, Wang Y and Wang B:

Immunoscore predicts survival in early-stage lung adenocarcinoma

patients. Front Oncol. 10(691)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Barrett T, Wilhite SE, Ledoux P,

Evangelista C, Kim IF, Tomashevsky M, Marshall KA, Phillippy KH,

Sherman PM, Holko M, et al: NCBI GEO: Archive for functional

genomics data sets-update. Nucleic Acids Res. 41 (Database

Issue):D991–D995. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, Hu Y, Law CW,

Shi W and Smyth GK: limma powers differential expression analyses

for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res.

43(e47)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Li W: Volcano plots in analyzing

differential expressions with mRNA microarrays. J Bioinform Comput

Biol. 10(1231003)2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Langfelder P and Horvath S: WGCNA: An R

package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC

Bioinformatics. 9(559)2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK,

Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, Paulovich A, Pomeroy SL, Golub

TR, Lander ES and Mesirov JP: Gene set enrichment analysis: A

knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression

profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 102:15545–15550. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein

D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT,

et al: Gene ontology: Tool for the unification of biology. The gene

ontology consortium. Nat Genet. 25:25–29. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Kanehisa M and Goto S: KEGG: Kyoto

encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:27–30.

2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Stelzl U, Worm U, Lalowski M, Haenig C,

Brembeck FH, Goehler H, Stroedicke M, Zenkner M, Schoenherr A,

Koeppen S, et al: A human protein-protein interaction network: A

resource for annotating the proteome. Cell. 122:957–968.

2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Chin CH, Chen SH, Wu HH, Ho CW, Ko MT and

Lin CY: cytoHubba: Identifying hub objects and sub-networks from

complex interactome. BMC Syst Biol. 8 (Suppl 4)(S11)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Breiman L: Random forests. Mach Learn.

45:5–32. 2001.

|

|

21

|

Cortes C and Vapnik V: Support-vector

networks. Mach Learn. 20:273–297. 1995.

|

|

22

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Sedgwick P: How to read a receiver

operating characteristic curve. BMJ. 350(h2464)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

González-Silva L, Quevedo L and Varela I:

Tumor Functional heterogeneity unraveled by scRNA-seq technologies.

Trends Cancer. 6:13–19. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Li X, Lu F, Cao M, Yao Y, Guo J, Zeng G

and Qian J: The pro-tumor activity of INTS7 on lung adenocarcinoma

via inhibiting immune infiltration and activating p38MAPK pathway.

Sci Rep. 14(25636)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Kim YJ, Kim JH, Kim O, Ahn EJ, Oh SJ,

Akanda MR, Oh IJ, Jung S, Kim KK, Lee JH, et al: Caveolin-1

enhances brain metastasis of non-small cell lung cancer,

potentially in association with the epithelial-mesenchymal

transition marker SNAIL. Cancer Cell Int. 19(171)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Kakogiannos N, Ferrari L, Giampietro C,

Scalise AA, Maderna C, Ravà M, Taddei A, Lampugnani MG, Pisati F,

Malinverno M, et al: JAM-A acts via C/EBP-α to promote claudin-5

expression and enhance endothelial barrier function. Circ Res.

127:1056–1073. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Parton RG and del Pozo MA: Caveolae as

plasma membrane sensors, protectors and organizers. Nat Rev Mol

Cell Biol. 14:98–112. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Chen D and Che G: Value of caveolin-1 in

cancer progression and prognosis: Emphasis on cancer-associated

fibroblasts, human cancer cells and mechanism of caveolin-1

expression (Review). Oncol Lett. 8:1409–1421. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Yamaguchi H, Takeo Y, Yoshida S, Kouchi Z,

Nakamura Y and Fukami K: Lipid rafts and caveolin-1 are required

for invadopodia formation and extracellular matrix degradation by

human breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 69:8594–8602.

2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Li Y, Wu Q, Lv J and Gu J: A comprehensive

pan-cancer analysis of CDH5 in immunological response. Front

Immunol. 14(1239875)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Dejana E, Orsenigo F and Lampugnani MG:

The role of adherens junctions and VE-cadherin in the control of

vascular permeability. J Cell Sci. 121:2115–2122. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Strilic B and Offermanns S: Intravascular

survival and extravasation of tumor cells. Cancer Cell. 32:282–293.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Vestweber D: VE-cadherin: The major

endothelial adhesion molecule controlling cellular junctions and

blood vessel formation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 28:223–232.

2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Sun Y, Liu JQ, Chen WJ, Tang WF, Zhou YL,

Liu BJ, Wei Y and Dong JC: Astragaloside III inhibits MAPK-mediated

M2 tumor-associated macrophages to suppress the progression of lung

cancer cells via Akt/mTOR signaling pathway. Int Immunopharmacol.

154(114546)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Huang F, Xue F, Wang Q, Huang Y, Wan Z,

Cao X and Zhong L: Transcription factor-target gene regulatory

network analysis in human lung adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Dis.

15:6996–7012. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Zhang J, Yin Y, Wang B, Chen J, Yang H, Li

T and Chen Y: Discovery of novel small molecules targeting TGF-β

signaling for the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer. Eur J

Med Chem. 289(117442)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Guardavaccaro D and Clevers H:

Wnt/β-catenin and MAPK signaling: Allies and enemies in different

battlefields. Sci Signal. 5(pe15)2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Derynck R, Turley SJ and Akhurst RJ: TGFβ

biology in cancer progression and immunotherapy. Nat Rev Clin

Oncol. 18:9–34. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Zhao Y, Li J, Ting KK, Chen J, Coleman P,

Liu K, Wan L, Moller T, Vadas MA and Gamble JR: The

VE-cadherin/β-catenin signalling axis regulates immune cell

infiltration into tumours. Cancer Lett. 496:1–15. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Zheng F, Chen Z, Jia W and Zhao R:

Editorial: Community series in the role of angiogenesis and immune

response in tumor microenvironment of solid tumor, volume III.

Front Immunol. 15(1495465)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Wan JCM, Massie C, Garcia-Corbacho J,

Mouliere F, Brenton JD, Caldas C, Pacey S, Baird R and Rosenfeld N:

Liquid biopsies come of age: Towards implementation of circulating

tumour DNA. Nat Rev Cancer. 17:223–238. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|