Introduction

Neurodegenerative diseases can result in the gradual

loss of neuronal function or structure in the central nervous

system (CNS), and include Alzheimer's disease (AD) and motor neuron

disease (1). A pathological

feature of these diseases is the abnormal deposition of proteins,

such as amyloid β (Aβ) and tau, in the brain and spinal cord

(2). Various neurodegenerative

diseases display specific differences, but they all exhibit common

clinical features; namely, the progressive loss of cognitive

function, motor coordination deficits and various symptoms

resulting from the loss of specific neuronal groups (3). Neurodegenerative diseases affect

millions of individuals worldwide (4). The prevalence and mortality rates

have also shown a growing trend over time, and these diseases are

considered one of the main threats to personal and social

well-being (4). Oxidative stress

(OS) serves an important role in the pathogenesis of

neurodegenerative diseases (5,6). The

CNS is particularly susceptible to OS because of its high oxygen

utilization rate and large polyunsaturated fatty acid contents

(7). Therefore, the antioxidant

inhibition of OS is considered a therapeutic strategy for

neurodegenerative diseases due to its ability to neutralize

reactive oxygen species (ROS), which is of therapeutic relevance

for reducing the progression of OS.

Neurodegenerative diseases have become one of the

largest health problems worldwide, and there is still a shortage of

appropriate treatment methods (8).

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) displays multi-component and

multi-target characteristics, providing a promising method for

preventing neurodegenerative diseases (9). The compounds and extracts derived

from TCM, such as evodiamine from Tetradium ruticarpum and

ginsenoside compound K from Panax ginseng, have received

widespread attention due to their possible applications as

therapeutic agents for AD and Parkinson's disease (10). In clinical practice, TCM has been

extensively utilized for treating age-related conditions, including

memory loss and cognitive decline (11,12).

Furthermore, bioactive compounds in plants, such as genipin from

Gardenia jasminoides fruit extract, had been proven to

possess the ability to prevent and stop the progression of AD and

Parkinson's disease (8). They can

regulate crosstalk between pathways through multiple targets, thus

improving chronic inflammatory interactions and inhibiting OS

damage (13). The leaves, stems

and rhizomes of Epimedium, also known as barrenwort, can be

used as therapeutic drugs (14).

Pharmacological studies have shown that Epimedium can

markedly regulate and improve the human immune system, and the

chemicals in Epimedium have great potential as plant drugs

for guarding against and treating chronic diseases such as AD

(15,16). Notably, >260 compounds have been

extracted from Epimedium (16), and research has suggested that the

compound icariin possesses strong neuroprotective properties and

has the potential as a drug for preventing neurological disorders

such as AD (17). However, the

main bioactive chemicals and their specific mechanisms that exert

antioxidative, anti-aging and neuroprotective effects in

Epimedium still require further exploration.

The median effect concentration value of

Wushanicaritin in PC12 cells is 3.87 µM, making it a promising

neuroprotective agent (16). In

addition, Wushanicaritin has been shown to maintain mitochondrial

activity and the enzymatic antioxidant defense system,

demonstrating marked intercellular antioxidant and neuroprotective

effects (16). Epimedin C was used

as the indicator component in the quality control for assessing the

quality of Wushan Epimedium in the Chinese Pharmacopoeia

(2020 edition) (18). A previous

study confirmed that total flavonoids of Epimedium can

prevent dopaminergic neuron death and cellular neurotoxicity in

vivo and in vitro, exerting neuroprotective effects

(19). Epimedin C is a

triterpenoid component extracted from the water extract of

Epimedium, containing high levels of flavonol glycosides

(20). The chemical structure of

Epimedin C is similar to that of icariin, indicating that they may

have similar pharmacological effects (21). Moreover, Epimedin C has been

reported to exert anti-inflammatory properties (21), and to have potential therapeutic

efficacy in angiogenesis, antioxidant damage and the inhibition of

apoptosis (22). However, it is

currently unclear whether Epimedin C can reduce neuronal cell

apoptosis by inhibiting oxidative damage, thereby preventing and/or

treating neurodegenerative diseases such as AD.

The PC12 rat adrenal pheochromocytoma cell line is

often adopted as a model neuron-like cell line and applied to study

neurodegenerative diseases (23).

Exogenous H2O2 can trigger OS damage and

cause apoptosis of PC12 cells (24). Our previous research indicated that

Tiaogeng Decoction (TGD) may be a potential therapeutic agent for

the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases, as it is involved in

mediating the nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2)

and JNK pathways (25). Notably,

TGD comprises 10 TCMs, including Epimedium. A core component

of neuronal response to ROS is the activation of JNK (26); JNK belongs to the mitogen-activated

protein kinase (MAPK) family, and JNK phosphorylation is associated

with diverse apoptotic transcription factors (27). Nrf2 participates in maintaining

cellular redox homeostasis and regulating the inflammatory response

of the body, and Nrf2 activation has a cellular protective effect

on neurodegenerative diseases (28). Heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) serves as a

protective protein during the OS response (29). Nrf2/HO-1 pathway activation

accelerates the upregulation of antioxidant and cell protective

genes, thereby reducing OS and inflammatory damage (30). Ultra-high performance liquid

chromatography-quadrupole-Exactive Orbitrap high resolution mass

spectrometry (UHPLC-Q-Exactive Orbitrap HRMS) can be utilized to

rapidly identify complex compound mixtures in plants (31). The present study aimed to assess

the active ingredients of Epimedium using UHPLC-Q-Exactive

Orbitrap HRMS. In addition to mass spectrometry results, network

pharmacological analysis was performed to explore whether Epimedin

C mediated the JNK/Nrf2/HO-1 pathway, and prevented the

H2O2-related OS damage and apoptosis of PC12

cells. Moreover, the present study aimed to clarify the possible

effect of Epimedin C on managing neurodegenerative diseases.

Materials and methods

Identification of chemical components

in Epimedium by UHPLC-Q-Exactive Orbitrap HRMS

In our previous research, UHPLC-Q-Exactive Orbitrap

HRMS analysis was conducted on TGD (11). By comparing and analyzing the

chemical composition of each herb detected in the viscera and serum

of rats after oral administration of TGD, the effective chemical

components of each TCM that worked in the formula were explored.

Epimedium is an important component of TGD. A total of 250

mg Epimedium sample (Sichuan Neo-Green Pharmaceutical

Technology Development Co., Ltd.) was taken and placed in a 2ml

centrifuge tube. Thereafter, 20% methanol (4 ml) was added for

centrifugation (4˚C, 10,000 x g, 15 min). Subsequently, 200 µl

supernatant was taken as the experimental sample. Chromatographic

separation was implemented through a Waters ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18

column (2.1x100 mm, 1.7 µm; Waters Corporation) at a column

temperature of 40˚C. The mobile phase included two solvents; mobile

phase A consisted of methanol whereas mobile phase B comprised a

0.1% formic acid aqueous solution. Elution was completed according

to the following schedule: 4% A from 0 to 4.0 min, 4-12% A at

4.0-10.0 min, 12-70% A at 10.0-30.0 min, 70-95% A at 30.0-35.0 min,

95% A at 35.0-38.0 min, and 4% A at 42.0-45.0 min. The flow rate

was 0.3 ml/min and the injection volume was 2 µl. The resolution

was 70,000 full width at half maximum and the cumulative time was

300 msec. Data collection and analysis of the results of

UHPLC-Q-Exactive Orbitrap HRMS analysis (Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) were performed using Xcalibur 4.1 software (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.).

Network pharmacological analysis:

Target prediction of Epimedium for improving AD

Drug targets were retrieved using the key word

‘Epimedium’ in the TCM systems pharmacology (TCMSP)

(https://www.91tcmsp.com/), SwissTarget

(http://swisstargetprediction.ch/),

PharmMapper (http://lilab-ecust.cn/pharmmapper/) and HERB databases

(http://herb.ac.cn/), utilizing the criteria oral

bioavailability ≥30% and drug similarity ≥0.18. Subsequently, with

‘Alzheimer's disease’ being used as the key word, drug targets were

searched in the GeneCards (https://www.genecards.org/), DisGeNet (https://disgenet.com) and Online Mendelian Inheritance

In Man (OMIM) databases (https://www.omim.org/), and Venn diagrams (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/Venn/)

were used to screen and generate overlapping targets between

diseases and drugs. The ‘drug disease target’ was visualized with

Cytoscape 3.8.2 (https://cytoscape.org/download.html), while common

targets of drugs were imported in STRING database (https://string-db.org/) for protein-protein

interaction (PPI) analysis. In the PPI network, proteins were

denoted by nodes, whereas protein interactions were signified by

edges. Nodes of various colors and sizes represented diverse degree

values, and larger nodes and darker red colors declared greater

degree values and more important targets. Gene Ontology (GO) and

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analyses

were performed on the top 20 core targets in Metascape database

(https://metascape.org/gp/index.html).

Subsequently, the exported clustering network was sorted in

accordance with the P-value using R 4.1.2 (https://www.r-project.org/) and a bubble chart was

generated.

Chemicals and reagents

Epimedin C was supplied by Chengdu Biopurify

Phytochemicals Ltd. (CAS no. 110642-44-9), and its purity was

detected by HPLC-Diode Array Detection to be 95-99%. In addition,

17β-estradiol (17β-E2) was provided by Sigma-Aldrich;

Merck KGaA (cat. no. E2758). All samples were stored in the

laboratory at 4˚C for future use.

Modeling and intervention

PC12 cells were obtained from The Cell Bank of Type

Culture Collection of The Chinese Academy of Sciences and were

cultured in the Dulbecco's Modified Eagle medium (cat. no.

C11995500BT; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) with 10% FBS

(cat. no. 10099-141C; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) at 37˚C

and 5% CO2. The compound 17β-E2 can be

produced in the brain and it participates in regulating the

reproductive axis (32). In

addition, it can act on synaptic plasticity, and improve neural

pathways and neurodegenerative diseases (32-34).

Therefore, the present study used 17β-E2 in the positive

control group. PC12 cells were classified into the normal control,

H2O2 model, 17β-E2 and Epimedin C

(1, 5 and 10 µM) groups. A concentration of 150 µM

H2O2 (25)

(cat. no. 7722-84-1; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) was applied for 4 h

at 37˚C and 5% CO2 to induce OS within PC12 cells in the

model and treatment groups. A total of 24 h before

H2O2 treatment, Epimedin C (1, 5 and 10 µM)

was introduced into the TCM groups, whereas 17β-E2 (1

nM) was added into the positive control group for 24 h at 37˚C and

5% CO2. To determine whether the JNK pathway affected

Epimedin C-induced Nrf2 activation, PC12 cells from the model and

treatment groups were also treated with the JNK agonist anisomycin

(5 µM; cat. no. S7409; Selleck Chemicals). Following 4 h of

H2O2 treatment, the culture medium was

removed, and the cells were further incubated with anisomycin for

24 h at 37˚C and 5% CO2.

Cell viability and toxicity

assays

The cultured cells were digested, centrifuge at

1,200 x g for 5 min at 25˚C and counted. Subsequently, cells

(2x104/well) were seeded into a 96-well plate and were

cultured for 12 h under 37˚C, 5% CO2 and 90% humidity

conditions. The cells were then treated with different

concentrations of Epimedin C (0-160 µM) for 24 h at 37˚C and 5%

CO2. Subsequently, cell viability was assessed according

to the instructions of the Cell Counting Kit-8 (cat. no. GK3607;

Gen-View Scientific Inc.) and the optimal drug administration

concentration was screened. In addition, according to the

manufacturer's instructions, a lactate dehydrogenase (LDH)

detection kit (cat. no. C0016; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology)

was used to assess the cytotoxicity of Epimedin C at different

concentrations (0-160 µM) to evaluate their safety. Six replicates

were set for each sample and the absorbance was measured at 450 nm

for the CCK-8 assay and at 490 nm for the LDH assay using a

microplate reader (BioTek; Agilent Technologies, Inc.).

ROS and malondialdehyde (MDA) level

measurements

The ROS assay kit (cat. no. S0033; Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology) was adopted to detect cellular ROS

levels. PBS was introduced to dilute DCFH-DA to 10 µmol/l. After

removing the culture medium, the diluted DCFH-DA at 10 µM was added

and the cells were incubated for 20 min at 37˚C. The cells were

then rinsed three times with PBS to thoroughly remove the DCFH-DA

that had not entered the cells. A microplate reader (BioTek;

Agilent Technologies, Inc.) was adopted for testing ROS levels. The

fluorescence was measured at an excitation wavelength of 485 nm and

an emission wavelength of 525 nm.

The lipid peroxidation level in PC12 cells was

evaluated using the MDA assay kit (cat. no. S0131S; Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology). PC12 cells (1x104/well)

were collected and lysed using RIPA lysis buffer (cat. no. P0013K;

Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). The cell lysate was then

centrifuged at 12,000 x g for 5 min at 4˚C to remove insoluble

debris. Finally, the absorbance of the resulting supernatant was

measured at 532 nm using a microplate reader. The MDA concentration

in the samples was calculated based on a standard curve prepared

concurrently.

Transmission electron microscopy

(TEM)

The PC12 cells were scraped and digested into a cell

suspension, and were immediately fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in

0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) for 24 h at 4˚C. Following primary

fixation, the cells were post-fixed in 1% OsO4 tetroxide

for 2 h at 4˚C, then dehydrated through a graded series of ethanol

(50, 70, 90 and 100%). The dehydrated cells were embedded in epoxy

resin. Ultrathin sections were cut using an ultramicrotome at a

thickness of 70-90 nm and collected on copper grids. The sections

were then stained with 1% uranyl acetate at room temperature for 10

min, and the samples were observed using a Talos L120C transmission

electron microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) operated at an

accelerating voltage of 80-120 kV. Digital images were acquired for

analysis.

TUNEL analysis

After intervention with different groups of drugs,

PC12 cells were immersed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at 4˚C,

after which the cells were rinsed three times with PBS and

permeabilized using 0.1% Triton X-100 for 3 min at 25˚C.

Subsequently, the TUNEL reaction solution (cat. no. C1170S;

Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) was added to the cells and

incubated for 1 h in the dark at 37˚C. The cells were then rinsed

with PBS and later subjected to nuclear counterstaining with DAPI

(cat. no. C1006; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) at room

temperature for 5 min. The number of TUNEL-positive cells from five

random regions in three individual samples was quantified using a

fluorescence microscope (Ti-E; Nikon Corporation), and

TUNEL-positive cell rate (%) was calculated as: TUNEL-positive cell

area/total cell area x100.

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry was applied for the quantitative

analysis of apoptosis and mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) in

PC12 cells, using the CytExpert software (version 2.5; Beckman

Coulter, Inc.) for analysis. The Annexin V-FITC/PI cell apoptosis

detection kit (cat. no. 556547; BD Biosciences) was utilized for

detecting cell apoptosis. Briefly, cells (2x105/well)

were harvested and resuspended in 400 µl binding buffer.

Thereafter, Annexin V-FITC and PI (5 µl each) were added and mixed,

and the cells were incubated in the dark for 15 min at room

temperature. Afterwards, flow cytometry (CytoFLEX SRT; Beckman

Coulter Inc.) was used to analyze early and late apoptotic cell

proportion.

The level of MMP can reflect the status of

apoptosis. Briefly, the cells (2x105/well) were cultured

in a 6-well plate and rinsed once with PBS, Subsequently, 1 ml JC-1

(cat. no. C2006; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) staining

solution was introduced, mixed sufficiently with the media and

incubated at 37˚C in an incubator for 20 min. Afterwards, the

supernatant was discarded, and the sample was rinsed twice with

JC-1 staining buffer (1X). An Altra flow cytometer (CytoFLEX SRT;

Beckman Coulter Inc.) was used to verify the changes in MMP in each

group of cells. The JC-1 aggregates (healthy mitochondria) were

detected in the PE channel (575 nm emission), while the JC-1

monomers (depolarized mitochondria) were detected in the FITC

channel (530 nm emission). The ratio of the geometric mean

fluorescence intensity (PE/FITC) was calculated to quantify the

MMP.

Western blotting (WB)

After treatment, PC12 cells were subjected to lysis

with RIPA buffer that contained 1% PMSF (cat. no. ST506; Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology). The BCA protein detection kit (cat.

no. P0011; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) was used to measure

protein concentration. Subsequently, PBS and 4X loading buffer were

added according to protein concentration, mixed evenly and boiled

at 95˚C for 10 min. Proteins (20 µg/lane) were separated by

SDS-PAGE on 10% gels and were then transferred to polyvinylidene

fluoride membranes (cat. no. ISEQ00010; Merck KGaA). After blocking

for 1 h at room temperature in 5% BSA (Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology), the membranes were subjected to primary antibody

incubation overnight at 4˚C using antibodies against: GAPDH

(1:1,000; cat. no. 5174; CST Biological Reagents Co., Ltd.), JNK

(1:1,000; cat. no. 9252; CST Biological Reagents Co., Ltd.),

phosphorylated (p)-JNK (1:1,000; cat. no. 4668; CST Biological

Reagents Co., Ltd.), HO-1 (1:1,000; cat. no. 43966; CST Biological

Reagents Co., Ltd.), Bcl-2 (1:1,000; cat. no. 2870; CST Biological

Reagents Co., Ltd.), Bax (1:1,000; cat. no. 14796; CST Biological

Reagents Co., Ltd) and Nrf2 (1:500; cat. no. ab137550; Abcam). The

next day, the membranes were washed six times with TBS-0.01% Tween

and were incubated with a HRP-conjugated Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L)

secondary antibody (1:10,000; cat. no. 33101ES60; Shanghai Yeasen

Biotechnology Co., Ltd) at room temperature for 1 h. After

incubation, the membranes were washed six times with TBST.

Subsequently, the membranes were visualized using Omni-ECL

(Epizyme; Ipsen Pharma). The gel imaging system (Chemiscope6300;

Clinx Science Instruments Co., Ltd.) was used for imaging and

semi-quantification was performed using ImageJ (version 1.6.0;

National Institutes of Health).

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± SD. Unpaired

Student's t-tests were used for pairwise comparisons between two

groups. For comparisons across more than two groups, the

homogeneity of variances was first assessed using Levene's test.

Following a significant Levene's test (P<0.05) which indicated

heterogeneity of variances, a Welch's ANOVA was conducted in place

of the standard one-way ANOVA. Post hoc comparisons against the

control or H2O2 group were then performed

using Dunnett's T3 test to account for the unequal variances. In

cases where Levene's test was not significant (P>0.05),

indicating homogenous variances, a standard one-way ANOVA was

performed, followed by Bonferroni's post hoc test for all

comparisons against the control or H2O2

group. GraphPad Prism version 9.3 (Dotmatics) was employed for data

analysis. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

Identification of active ingredients

and potential targets of Epimedium

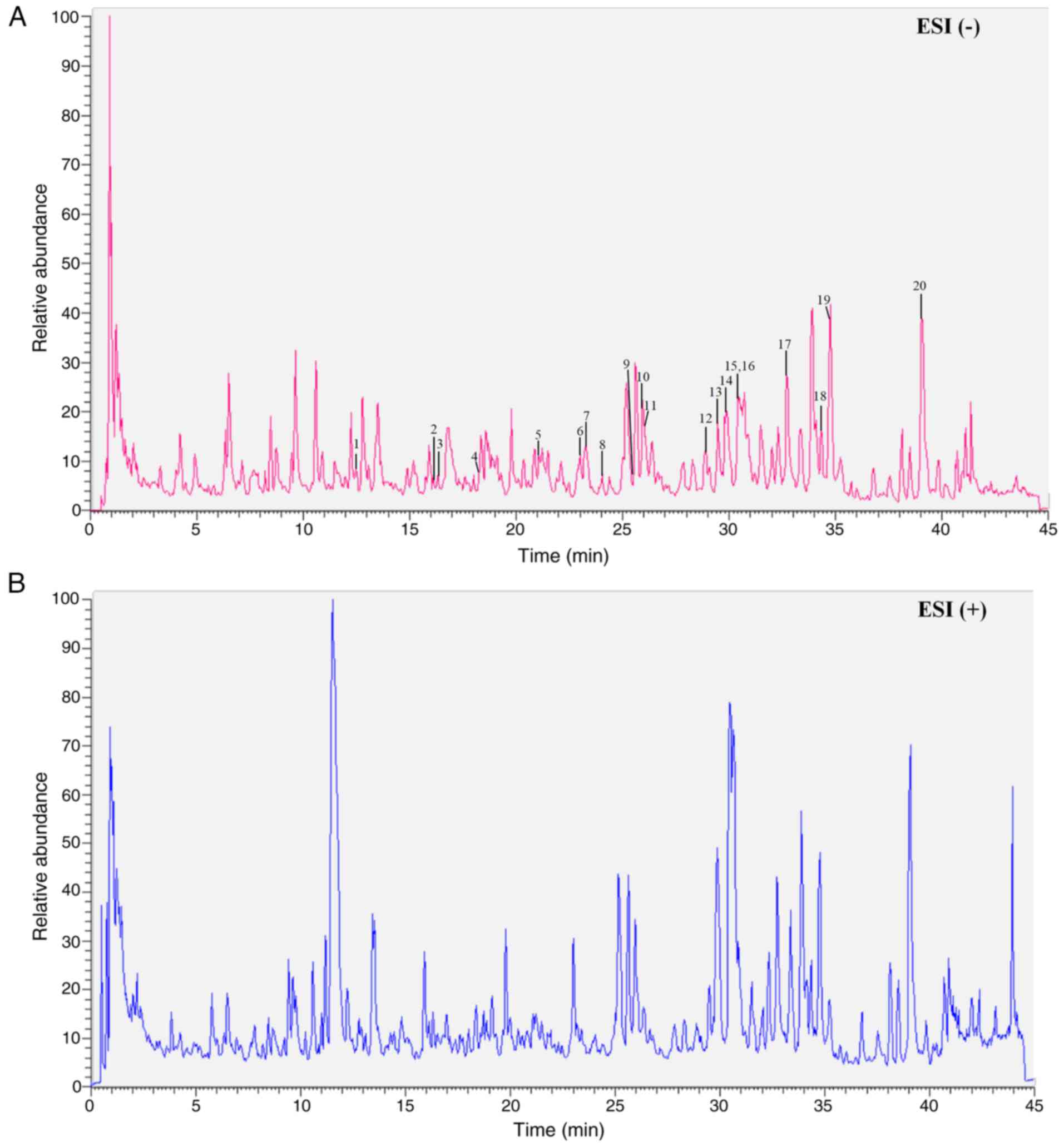

Comparing the active ingredients in TGD that can

enter the bloodstream, as identified by UHPLC-Q-Exactive Orbitrap

HRMS in our previous study (11),

a total of 20 active ingredients in Epimedium that could

enter the rat bloodstream and exert their effects were identified,

including Epimedin C, Epimidin B and others (Table I). The total ion chromatograms of

active ingredients within Epimedium compound are displayed

in Fig. 1.

| Table IIdentification of active ingredients

in Epimedium that can enter the bloodstream. |

Table I

Identification of active ingredients

in Epimedium that can enter the bloodstream.

| Number | RT, min | Precursor ion | Measured mass,

Da | Calculated mass,

Da | Error, ppm | Formula | Identification |

|---|

| 1 | 12.24 | (M-H)- | 337.09348 | 337.09179 | 1.793 |

C16H18O8 |

3-O-p-coumaroylquinic acid |

| 2 | 16.09 | (M-H)- | 479.08377 | 479.08201 | 0.987 |

C21H20O13 | Isoyangmei bark

glycoside |

| 3 | 16.45 | (M-H)- | 447.09393 | 447.09218 | 1.235 |

C21H20O11 | Trifolin |

| 4 | 18.38 | (M-H)- | 464.09064 | 463.08710 | 6.321 |

C21H20O12 | Hyperin |

| 5 | 21.34 | (M-H)- | 576.17704 | 577.15518 | 0.163 |

C27H30O14 | Kaempferitrin |

| 6 | 22.94 | (M-H)- | 465.23335 | 465.21190 | -1.173 |

C24H34O9 |

(4-(β-D-glucopyranosyloxy)-2,6-bis(3-methyl-2-buten-1-yl)phenyl)(hydroxy)acetic

acid |

| 7 | 23.39 | (M-H)- | 677.2199 | 677.20761 | 2.394 |

C32H38O16 | Hexandraside E |

| 8 | 24.03 | (M-H)- | 678.21332 | 678.20761 | 0.032 |

C32H38O16 | Epimedium B |

| 9 | 25.6 | (M-H)- | 661.21472 | 661.21269 | 1.960 |

C32H38O15 | Epimedium A |

| 10 | 25.95 | (M-H)- | 807.27338 | 807.27060 | 0.166 |

C38H48O19 | Epimidin B |

| 11 | 26.06 | (M-H)- | 691.22565 | 691.22326 | 2.223 |

C33H40O16 |

Anhydroicaritin-3,7-di-O-glucoside |

| 12 | 28.95 | (M-H)- | 515.15625 | 515.15478 | 0.237 |

C26H28O11 | Epimedin C |

| 13 | 29.55 | (M-H)- | 675.23077 | 675.22834 | 2.342 |

C33H40O15 | Baohuoside VII |

| 14 | 29.94 | (M-H)- | 645.22003 | 645.21778 | 2.636 |

C32H38O14 | Sagittatoside

B |

| 15 | 30.47 | (M-H)- | 529.17163 | 529.17043 | 0.287 |

C27H30O11 | Baohuoside C |

| 16 | 30.47 | (M-H)- | 721.23596 | 721.23382 | 3.895 |

C34H42O17 | Icariin |

| 17 | 32.88 | (M-H)- | 529.17194 | 529.17043 | 0.060 |

C27H30O11 | Icariin I |

| 18 | 34.36 | (M-H)- | 631.20447 | 631.20213 | 0.132 |

C31H36O14 | Icariin F |

| 19 | 34.71 | (M-H)- | 499.16156 | 499.15987 | 0.454 |

C26H28O10 | Icariside |

| 20 | 39.09 | (M-H)- | 513.18706 | 513.17552 | -0.338 |

C27H30O10 | Baohuoside I |

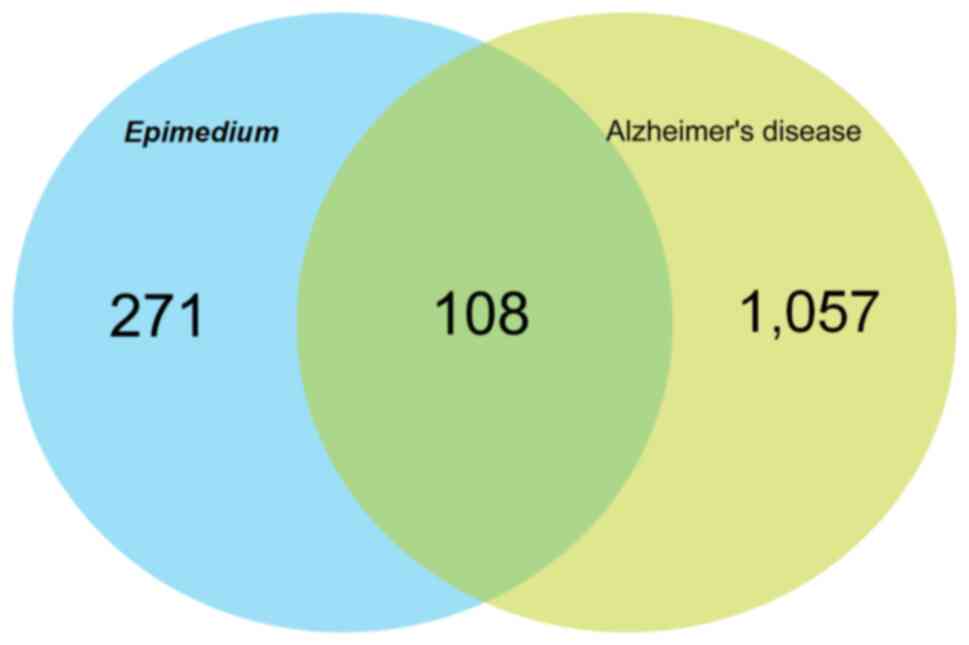

To compensate for the lack of recent updates in drug

databases, which may result in incomplete inclusion of components,

network pharmacological analysis (using AD as an example) was

conducted in conjunction with MS. Using ‘Epimedium’ as the

key word, and oral bioavailability ≥30% and drug similarity ≥0.18

as the screening criteria in TCMSP, SwissTarget, PharmMapper and

HERB databases, a total of 23 components of Epimedium were

obtained, and 379 drug targets were retrieved. Using ‘Alzheimer's

disease’ as the key word, a total of 1,165 drug targets were

obtained from the GeneCards, DisGeNet and OMIM databases after

deduplication. Based on the Venn diagram, 108 common targets of

Epimedium and AD were identified (Fig. 2).

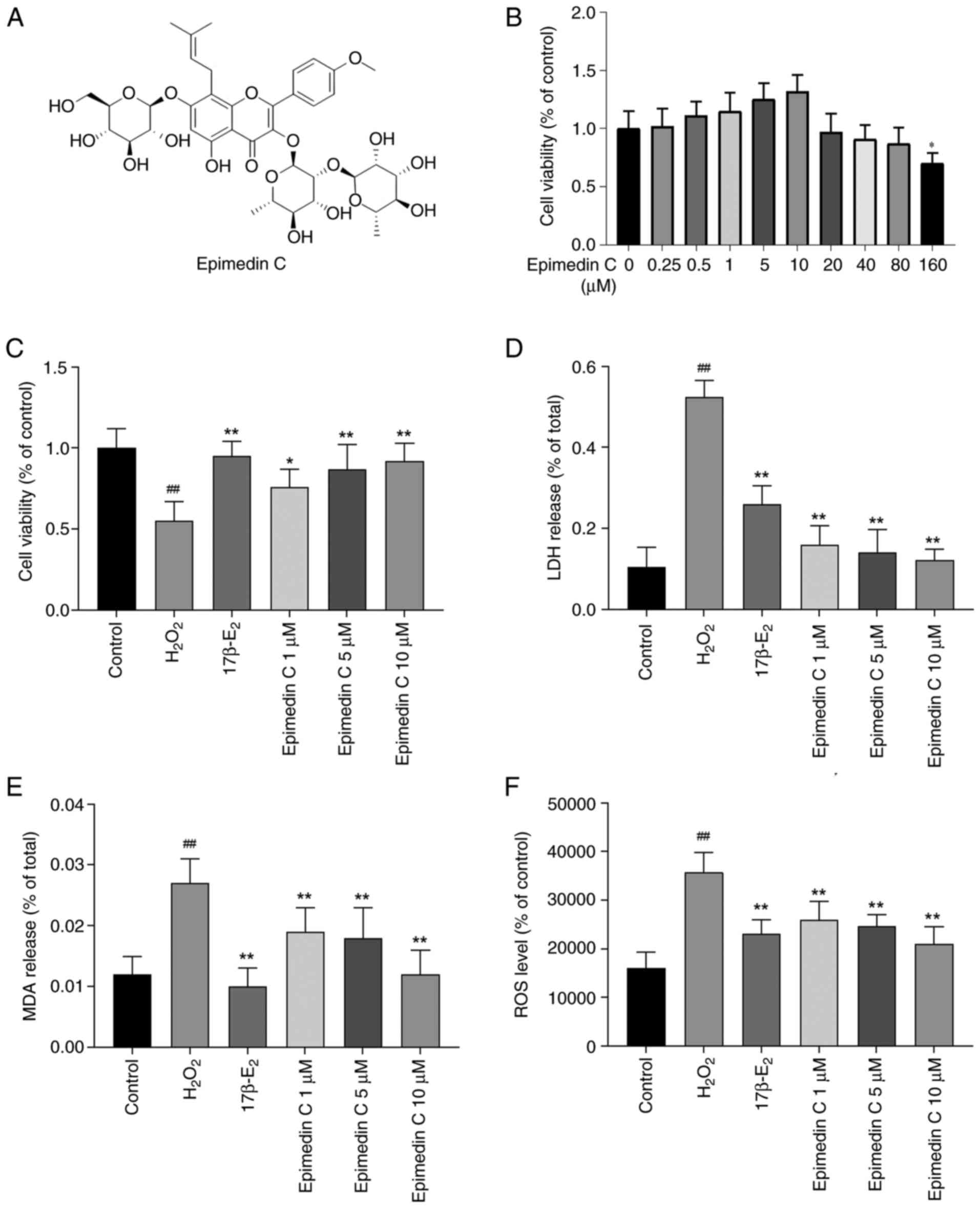

Preventive effect of Epimedin C on

H2O2-induced oxidative damage in PC12

cells

H2O2 stimulation can cause OS

damage, leading to apoptosis or necrosis in PC12 cells (35,36).

Except for the control group, all the other groups of PC12 cells

were exposed to 150 µM H2O2 treatment for 4 h

for modeling OS (25). Before

treatment with H2O2, these cells were

pretreated with 0-160 µM Epimedin C (Fig. 3A) for 24 h to evaluate the

protective effects of Epimedin C on PC12 cells and to identify its

optimal concentration range for improving OS status (Fig. 3B). The results showed that 0-80 µM

Epimedin C pretreatment in PC12 cells did not have an effect on the

viability of PC12 cells compared with the control. Among these

concentrations, Epimedin C at concentrations of 1, 5 and 10 µM had

an improved cell survival rate than other concentrations; however,

this was not statistically significant. Therefore, the

concentrations of 1, 5 and 10 µM were used for subsequent

experiments. Relative to the OS model group, after 24 h of

intervention with 17β-E2 and Epimedin C, the viability of PC12

cells was significantly improved (Fig.

3C). Among them, the cell survival rate significantly rose in a

dose-dependent manner in response to pretreatment with 1, 5 and 10

µM Epimedin C. LDH analysis was applied to detect the toxicity of

different treatments on PC12 cells in each group; according to the

results, relative to the control group, the

H2O2-induced group showed a significant

increase in LDH release (Fig. 3D).

Alternatively, the cells pretreated with Epimedin C and

17β-E2 displayed a significant decrease in LDH secretion

and cytotoxicity compared with those in the

H2O2-induced group. These comprehensive

results indicated that intervention with 10 µM Epimedin C had the

best therapeutic efficacy in PC12 cell survival and the least toxic

side effects.

MDA and ROS levels

MDA and ROS are involved in producing OS free

radicals and are key indicators for measuring oxidative and

antioxidant capacity (37,38). The results of the present study

revealed that relative to the control group, MDA and ROS contents

in PC12 cells induced by H2O2 were

significantly increased (Fig. 3E

and F). In cells that had been

pretreated with 17β-E2 or 1, 5 and 10 µM Epimedin C, the MDA and

ROS contents were reduced to varying degrees compared with those in

the H2O2 group, indicating that Epimedin C is

beneficial for alleviating the OS status of PC12 cells. Notably, 10

µM Epimedin C was the most effective concentration.

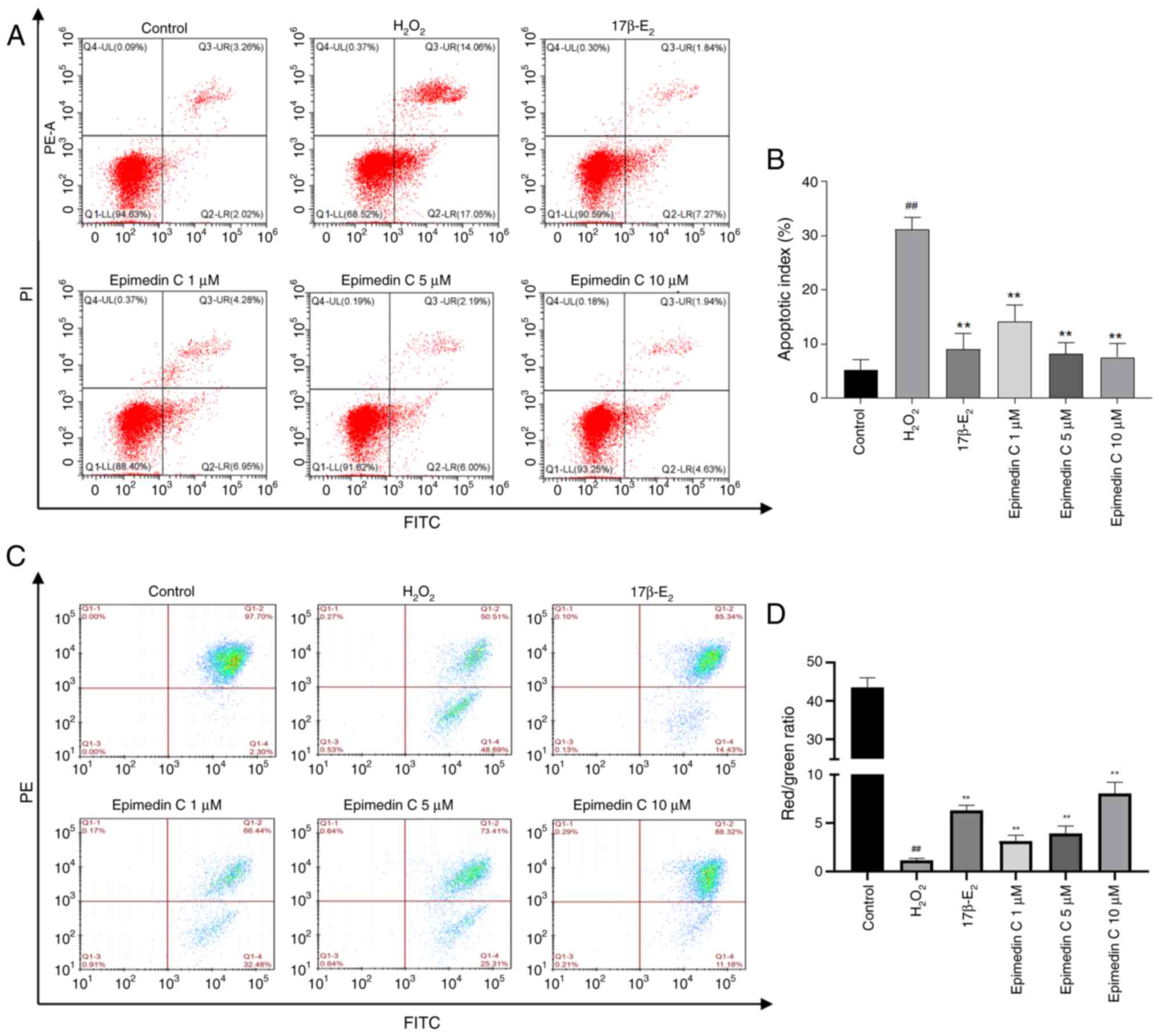

Epimedin C can inhibit the

H2O2-mediated apoptosis of PC12 cells

OS can induce cell apoptosis associated with

increased ROS production and decreased MMP levels (39). Therefore, the cells were stained

with Annexin V-FITC and PI, and the apoptosis rate was measured

using flow cytometry (Fig. 4A and

B). The present results showed

that, after treatment with 150 µM H2O2 for 4

h, the PC12 cell apoptosis rate was significantly increased. By

contrast, intervention with Epimedin C resulted in a decline in

apoptosis rate compared with that in the H2O2

group, suggesting that Epimedin C can inhibit cell apoptosis.

A reduction in MMP represents a hallmark event

during early cell apoptosis, which is evident by the transition of

JC-1 from red fluorescence to green fluorescence (40). To further evaluate the apoptosis

status of each group of cells, the MMP loss within

H2O2-treated PC12 cells was observed through

JC-1 staining. As shown in Fig. 4C

and D, the MMP of

H2O2-treated PC12 cells was decreased,

whereas pretreatment with Epimedin C (1, 5 and 10 µM) resulted in a

dose-dependent improvement in MMP, with varying degrees of

upregulation.

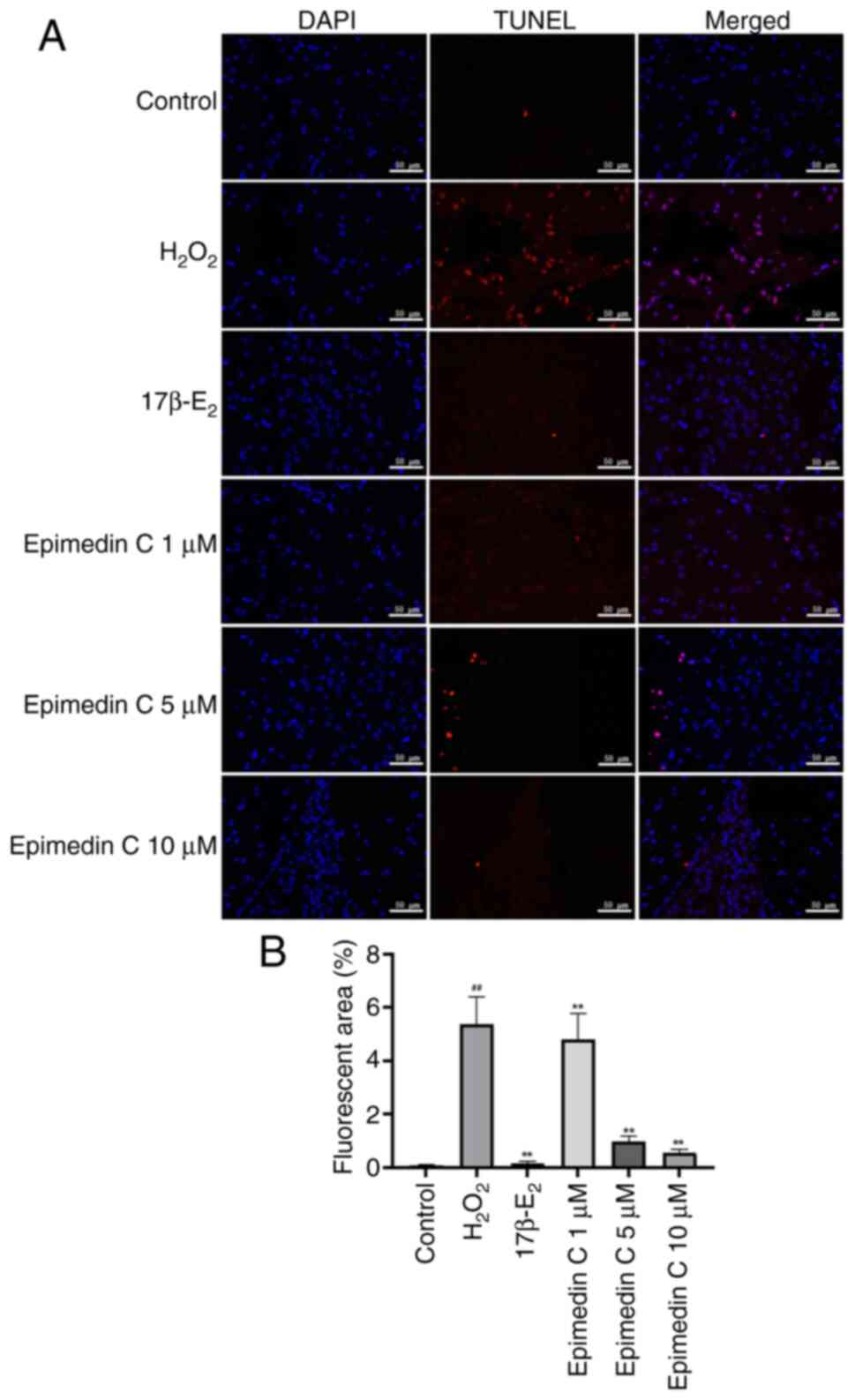

TUNEL staining can be conducted to detect apoptotic

cells with large amounts of DNA degradation during the late stage

of apoptosis (41). Therefore,

TUNEL staining was performed on each group of cells in the current

study (Fig. 5A). The results of

the TUNEL assay revealed that relative to the control group,

following H2O2 induction modeling, the

apoptosis of PC12 cells in the model group (level of red

fluorescence) was significantly increased (Fig. 5B). Relative to the model group,

after drug intervention, the apoptosis rates of PC12 cells in the

17β-E2 and Epimedin C groups were significantly

improved. The degree of apoptosis was ameliorated to varying

degrees in response to different concentrations of Epimedin C, with

the largest improvement observed in the 10 µM Epimedin C group.

Ultrastructural changes of PC12

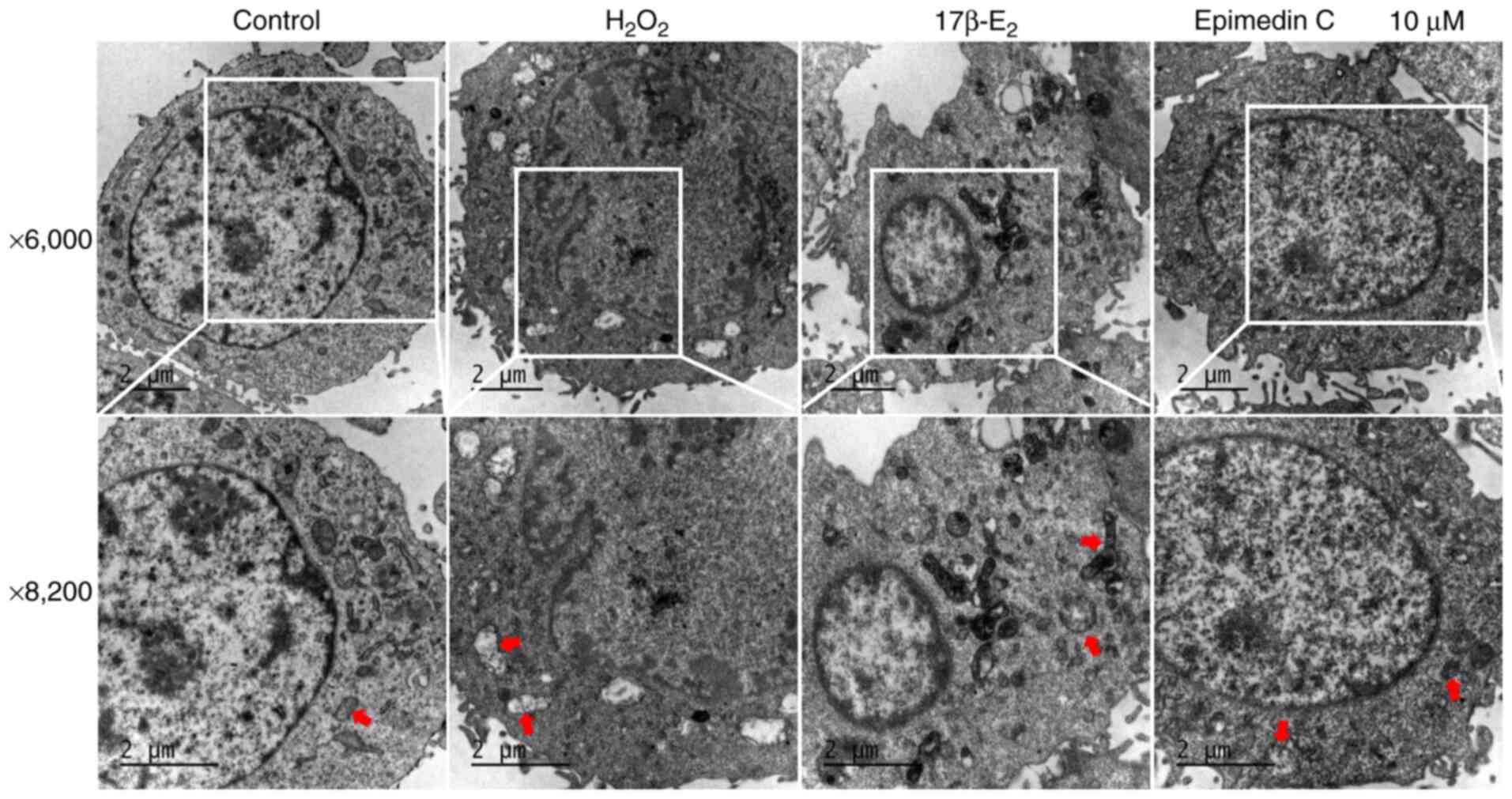

cells

Within the present study ultrastructural changes of

PC12 cells in each group was observed using TEM (Fig. 6). Under physiological conditions,

the mitochondria are present with prominent cristae and intact

membranes (42). The control group

cells had clear nuclear membranes and uniform chromatin. After

H2O2 induction, marked mitochondrial damage

was observed in PC12 cells, evident as mitochondrial membrane

rupture and chromatin condensation, accompanied by vacuolization.

As aforementioned, 10 µM Epimedin C had the largest effect on

improving H2O2-mediated OS damage to PC12

cells. Accordingly, TEM was performed on PC12 cells treated with 10

µM Epimedin C to detect ultrastructural changes. The results

indicated that treatment with 10 µM Epimedin C could inhibit

mitochondrial damage and alleviate mitochondrial swelling in PC12

cells, indicating that 10 µM Epimedin C can improve oxidative

damage and inhibit cell apoptosis.

Roles of Epimedin C in activating the

JNK/Nrf2/HO-1 pathway within H2O2-mediated

PC12 cells

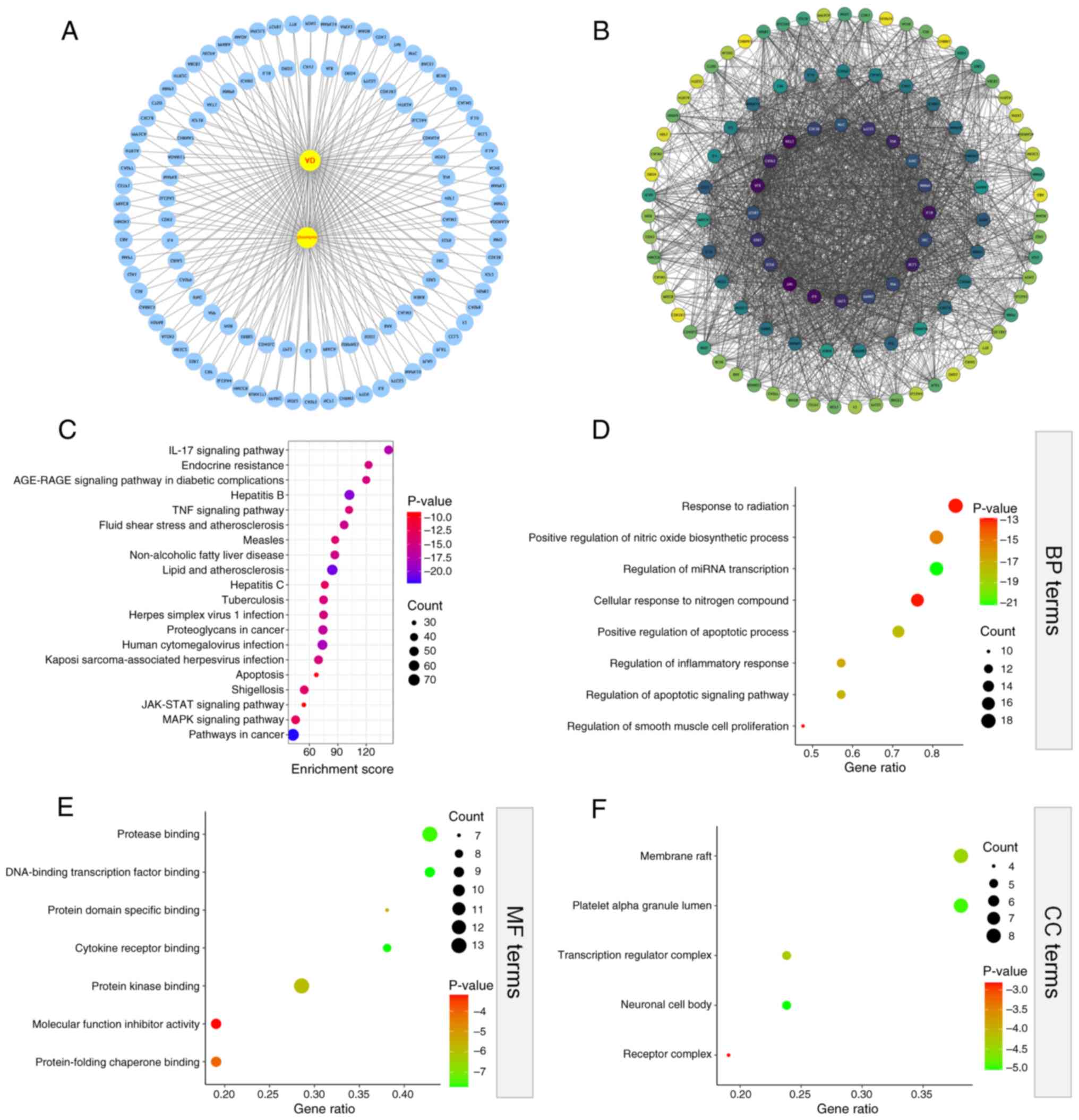

The ‘drug-disease-target’ network was visualized

with Cytoscape 3.8.2 software, and common targets between drugs

(Epimedium) and diseases (AD) were imported in STRING

database for PPI analysis. The PPI results included 110 nodes and

2,102 edges (Fig. 7A and B). Thereafter, the top 20 core genes of

Epimedium for treating AD were screened using R language (R

4.1.2), including BCL2, APP, JUN, CASP3, ESR1, IL1B and TNF. The

top 20 core targets underwent GO analysis in Metascape database. As

a result, the shared targets were involved in various GO biological

processes (Fig. 7D), including

‘positive regulation of apoptotic process’, ‘regulation of

apoptotic signaling pathway’, ‘regulation of inflammatory response’

and ‘cellular response to nitrogen compound’. Moreover, the GO

molecular functional results (Fig.

7E) showed that the shared targets involved in ‘DNA-binding

transcription factor binding’, ‘cytokine receptor binding’,

‘protease binding’ and ‘protein kinase binding’. While GO cellular

component results (Fig. 7F)

indicated that the shared targets were closely related to ‘platelet

alpha granule lumen’, ‘neuronal cell body’, ‘transcription

regulator complex’ and ‘receptor complex’. Additionally, as

revealed by KEGG enrichment analysis, the shared targets were

enriched in pathways such as ‘MAPK signaling pathway’, ‘endocrine

resistance’, cell clearance and ‘apoptosis’ (Fig. 7C).

JNK belongs to the MAPK family and has a crucial

effect on cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, immune

response and embryonic development (43). From the network pharmacological

analysis, KEGG enrichment analysis showed that the pathway through

which Epimedium improves AD was significantly enriched with

the ‘MAPK signaling pathway’. In addition, the PPI network revealed

that the top 20 core targets included APP, JUN and BCL2. Notably,

JUN (also known as C-JUN) is involved in the JNK pathway (44), and activated JUN promotes the

expression of various pro-apoptotic proteins (45). The Nrf2 pathway is an important

regulatory factor for cellular antioxidant response (46), which is involved in triggering the

expression of antioxidant and cell protective genes, and enhancing

cellular antioxidant capacity (47); therefore, activation of Nrf2 can

reduce neuronal damage caused by OS and inflammation (48). The free Nrf2 then transfers to the

nucleus and binds to antioxidant-related elements, leading to the

expression of various antioxidant and detoxifying genes, such as

HO-1(49). Research has shown that

MAPKs are closely interrelated with Nrf2 nuclear translocation in

eliminating OS (50).

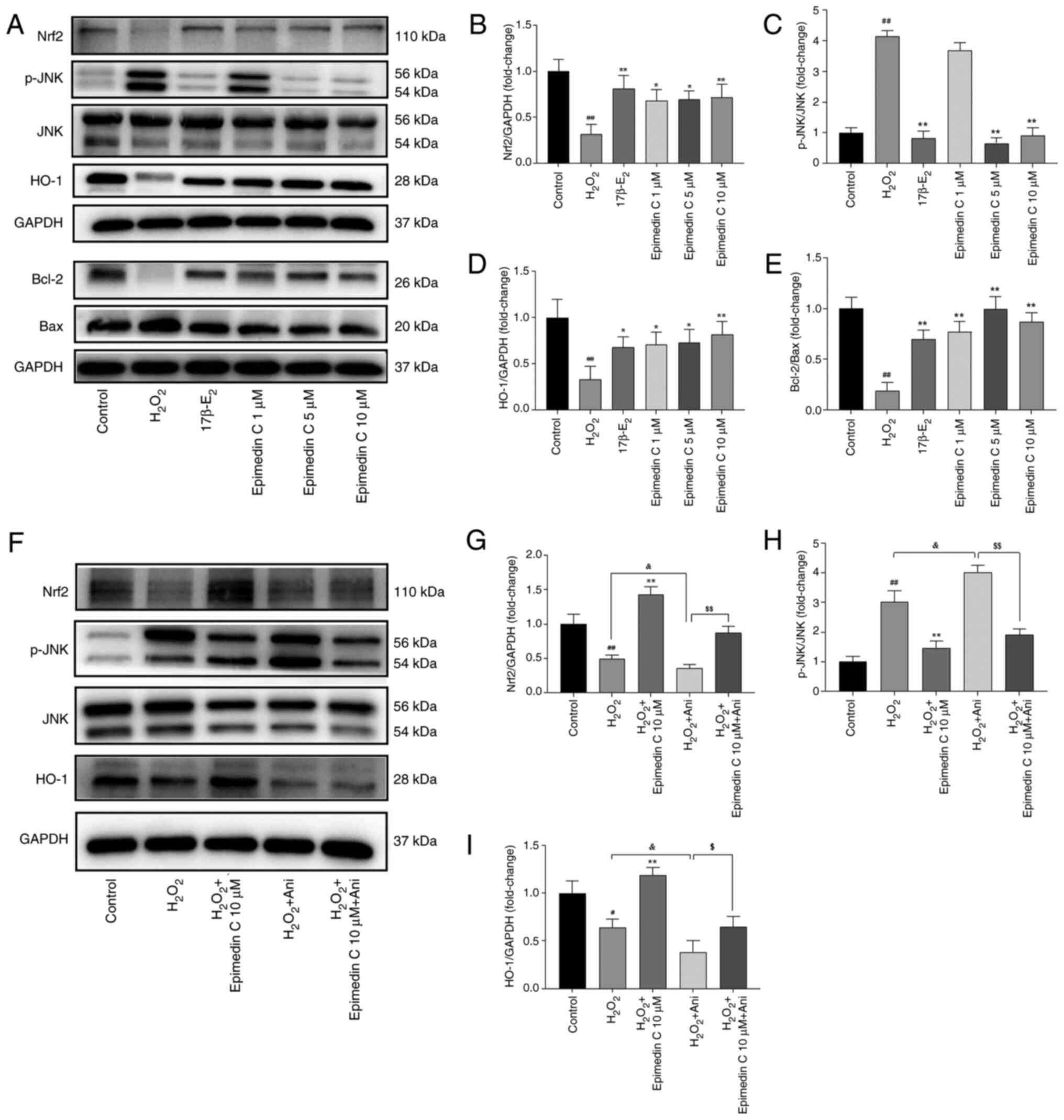

Therefore, to study the neuroprotective role

mediated by Epimedin C, WB was conducted for verifying p-JNK, Nrf2

and HO-1 protein levels. Relative to the control group,

H2O2 increased p-JNK levels but decreased

Nrf2 levels, whereas Epimedin C downregulated p-JNK expression, and

upregulated Nrf2 and HO-1 levels induced by

H2O2 (Fig.

8A-D). Furthermore, it was observed that compared with in the

H2O2 model group, Epimedin C decreased Bax

expression while increasing Bcl-2 expression (Fig. 8A and E).

To confirm that Epimedin C mediated protection via

the JNK pathway, the present study used a JNK agonist (anisomycin)

for supplementary validation. The results revealed that p-JNK was

activated and significantly upregulated in PC12 cells co-cultured

with JNK agonist (Fig. 8F and

H). By contrast, after treatment

with Epimedin C and anisomycin, p-JNK expression decreased compared

with following treatment with anisomycin alone, whereas Nrf2 and

HO-1 levels were significantly increased (Fig. 8F-I).

Discussion

With the aging population, neurodegenerative

diseases are receiving increasing attention from the fields of

science and medicine (51).

According to statistics, in 2016, 5.4 million Americans suffered

from AD (52), and based on

further data published in 2021, it is estimated that >12 million

Americans may develop neurodegenerative diseases over the next 30

years (52). Neurodegenerative

diseases are the main chronic progressive diseases that affect

individual physical health (53),

which exhibit the typical features of gradual selective neuronal

system loss (54). OS can damage

the blood-brain barrier (BBB), and as a result, neurotoxic

substances can enter the brain and ultimately result in the

accumulation of ROS (55).

Upregulation of ROS levels has been confirmed to be a common major

feature within the brains of patients with neurodegenerative

disease (56), with excessive

production of ROS causing ATP loss, decreased MMP and increased

apoptosis (57). TCM has been used

for treating neurodegenerative diseases for thousands of years

(58), and according to a number

of modern pharmacological studies, prescriptions, herbs, bioactive

ingredients and monomeric compounds of TCM are effective at

treating neurodegenerative diseases (59-61).

Epimedium is a TCM that is mainly applied in

treating Parkinson's disease and AD (62). Research has confirmed that

Epimedium has a protective effect on neurodegenerative

diseases such as AD (19), and the

active ingredients of Epimedium are flavonoids, which

regulate various biological effects in vitro and in

vivo, such as angiogenesis, antioxidant damage and inhibition

of apoptosis (22,63). According to relevant research,

icariin possesses antioxidant and immunomodulatory effects, and can

regulate neuroendocrine function (64). It has been determined that 100 g/l

Epimedin C is found to yield ~34.24 g/l icariin within 8 h

(65). Compared with icariin,

Epimedin C has a lower cost and comparable efficacy (21,65),

and is an effective antioxidant. At present, to the best of our

knowledge, no studies have yet been performed on Epimedin C and its

specific mechanism in preventing and/or treating neurodegenerative

diseases, including AD.

There is evidence to suggest that in AD, a vicious

cycle revolves around the production of Aβ, Aβ aggregation, plaque

formation, microglia/immune response, inflammation and ROS

production. In this cycle, ROS serves a central role and

H2O2 is considered an important second

messenger of ROS (66). The

excessive production of H2O2 can lead to OS

and inflammation in the brain of patients with AD (67); therefore, it is considered that

H2O2 can simulate the disease manifestations

of AD-related oxidative damage, and some studies have confirmed

this (68,69). The present study confirmed that

Epimedin C intervention enhanced cell viability and survival rate,

improved OS damage caused by H2O2 exposure

and reduced the H2O2-mediated LDH leakage in

PC12 cells. In the body, oxygen free radicals can be generated via

both enzymatic and non-enzymatic systems, and the antioxidant

defense system balances their levels; notably, if the biochemical

balance between oxidants and antioxidants is disrupted, OS will

occur (70). The increase in ROS

content can disrupt the basic structures of proteins, nucleic acids

and lipids, resulting in structural damage and functional changes,

ultimately resulting in cell apoptosis (71). MDA is the final product of the

oxidative decomposition of lipid peroxides, and its content can be

measured to identify the degree of lipid peroxidation on the cell

membrane (72). Therefore, the

activities of superoxide dismutase and MDA are considered to be

indicative of the degree of OS. The experimental results of the

present study indicated that Epimedin C effectively reduced ROS

accumulation mediated by H2O2 within PC12

cells and lowered the levels of MDA after

H2O2 treatment, demonstrating its ability to

resist OS. In addition, flow cytometry, TUNEL staining and MMP

results all showed that PC12 cells underwent significant apoptosis

after H2O2 induction, and Epimedin C

intervention had an inhibitory effect on cell apoptosis, with the

best effect observed in respones to 10 µM. Under TEM, the PC12 cell

ultrastructure also confirmed this: The mitochondrial membrane of

PC12 cells was ruptured and chromatin was condensed, showing

vacuolization and apoptosis after H2O2

intervention. However, mitochondrial damage was notably reduced

after intervention with 10 µM Epimedin C. Therefore, it was

hypothesized that Epimedin C has potential therapeutic effects on

preventing and improving neurodegenerative diseases.

To seek the key targets and potential mechanisms of

Epimedin C in improving neurodegenerative diseases, the present

study first identified the active ingredients of Epimedium

through UHPLC-Q-Exactive Orbitrap HRMS analysis and conducted

network pharmacological analysis using AD as an example. A total of

108 shared targets were screened, and the top 20 core targets

included APP, JUN and BCL2. From GO and KEGG analyses, the

potential mechanism of Epimedium in improving AD was

significantly enriched in ‘neuronal cell body’, ‘regulation of

apoptotic signaling pathway’ and ‘MAPK signaling pathway’. MAPKs

are conserved signaling proteins responsible for regulating

numerous eukaryotic processes (73), and members of the MAPK family,

including ERK1/2, JNK/SAPK, p38 and ERK5. are known to participate

in neuron growth, differentiation and survival (74). JNK has an important effect on

different diseases such as AD and Parkinson's disease caused by

inflammation and OS (75), and

research has confirmed that JNK pathway activation can exacerbate

OS, leading to neurotoxic effects (76). Nrf2 is considered the main

regulator of redox balance, which has a crucial role in cellular

defense against OS (77,78). Research has shown that Nrf2/HO-1

expression is directly influenced by the JNK pathway, and

activation of Nrf2/HO-1 signaling is crucial for reducing oxidative

damage (79). Notably, our

previous studies (80,81) have focused on validating the

mechanism of action of the JNK pathway in response to TGD,

particularly linking the JNK pathway to

neuroprotection/neurodegeneration and OS response. One of these

previous studies (25) confirmed

that TGD can provide neuroprotective effects on

H2O2-mediated oxidative damage and apoptosis

of PC12 cells through the Nrf2 and JNK pathways. Epimedium

is the main drug component of TGD, and the aforementioned results

offer a biological background and scientific foundation for the

present study. Therefore, the present study focused on the JNK

pathway to verify whether Epimedin C exerted neuroprotective

effects through this pathway.

TGD has also been validated to improve premature

menopause-associated cognitive dysfunction by increasing estrogen

levels (11). In addition, other

in vitro and in vivo studies have supported the

neuroprotective effects of estrogen and its effects on

neurotransmitter systems related to cognition (25,80-82).

When treating neurological diseases, the efficacy of oral TCM is

determined by the ability of the components to reach target organs

via the BBB (80). It is important

to comprehensively understand serum pharmacokinetics of oral TCM to

elucidate the absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion of

such active ingredients (83).

According to research, active ingredients in TCM, such as

Epimedium, can potentially improve BBB function, elevate

cerebral blood flow and avoid cognitive impairment through

suppressing the activation of astrocytes and microglia, protecting

the myelin function of oligodendrocytes and reducing neuronal

apoptosis (84). Furthermore,

there is evidence suggesting that icariin exerts neuroprotection

through crossing the BBB and regulating pathways (85). In our previous study,

UHPLC-Q-Exactive Orbitrap HRMS was used to identify the components

absorbed by mouse brain tissue after oral administration of TGD, in

order to clarify the specific components that exert their effects

on the brain. The results showed that icariin C could penetrate the

BBB and exert therapeutic effects on the brain (11). A previous study reported that

Epimedin C can be converted into icariin in vivo and

gradually hydrolyzed into metabolic small molecules such as icariin

C to exert its effects (86). Wong

et al (87) explored the

pharmacokinetics of isoprenoid flavonoids after ingestion of

standardized Epimedium extract and assessed their

relationship with serum estrogenic kinetics. The results of this

previous study revealed the potential estrogenic effects of

Epimedium extract and suggested that isoprenoid flavonoids

might be used to treat menopause and other diseases requiring

estrogenic effects. Epimedin C has been confirmed to be a mature

plant extract with estrogen-like activity (88). Estradiol has been proven to have

neuroprotective effects on excitatory neurotoxicity, OS and

apoptosis (89-91).

Therefore, similar to previous studies, the present study used

17β-E2 as a positive control drug and compared its

efficacy with Epimedin C.

In the present study, WB results showed that

relative to the control group, the JNK pathway was significantly

activated following H2O2 exposure, and Nrf2

and HO-1 levels were significantly reduced. However, after Epimedin

C intervention, p-JNK expression evidently decreased, whereas Nrf2

and HO-1 levels increased. At the same time, Epimedin C decreased

the levels of Bax and upregulated Bcl-2 levels, indicating that

Epimedin C may alleviate OS damage and inhibit the apoptosis of

PC12 cells through suppressing JNK pathway phosphorylation and

activating Nrf2/HO-1. To further confirm this, the JNK agonist

anisomycin was employed in the present study to further activate

the JNK pathway and observe the improvement results after Epimedin

C intervention. The results signified that compared with in the

control and H2O2 groups, JNK was activated

and markedly upregulated in PC12 cells co-cultured with JNK agonist

(H2O2 + anisomycin group). After treatment

with Epimedin C (H2O2 + anisomycin + Epimedin

C group), p-JNK expression was decreased, and Nrf2 and HO-1 levels

were increased, which further confirmed the present hypothesis.

Notably, according to the network pharmacological analysis

performed in the current study, Epimedin C has the characteristics

of targeting multiple molecules and complex signal transduction. In

this exploration, only the inhibitory effect of Epimedin C on JNK

pathway phosphorylation was investigated, which may activate

Nrf2/HO-1 and suppress the OS-induced apoptosis of PC12 cells.

However, whether Epimedin C has other preventive mechanisms against

neurodegenerative diseases still needs to be explored. According to

a previous cell experiment, the medicinal components of Epimedin C

can be effectively utilized and also converted into icariin

(21). Notably, the difference in

solubility between Epimedin C and icariin results in a higher

Epimedin C initial concentration (9.72 mg/l) than icariin at the

same dose (7.86 mg/l), and the residual concentration of Epimedin C

in cells is also higher than that of icariin (21). At present, there is still a lack of

research on the absorption of Epimedin C in the human body after

ingestion of Epimedium. Therefore, it is crucial to optimize

and explore the optimal drug concentration in cells, and drug

absorption into target cells is a prerequisite for the subsequent

therapeutic effects (92).

According to the results of the present study, Epimedin C at 160 µM

exerted neurotoxicity: Considering that Epimedium contains

~5 µM/g Epimedin C (93), it is

speculated the human dosage of Epimedium should not exceed

32 g. A limitation of the present study is that only in

vitro PC12 cell experiments were conducted. Due to the

complexity and heterogeneity of human pathology, translating these

findings into human therapies requires careful and robust

validation through in-depth molecular research and comprehensive

clinical trials (91). Future

research will further conduct relevant clinical trials, focusing on

the pharmacological mechanisms of Epimedin C in preventing

neurodegenerative diseases in vivo and in vitro,

aiming to offer a reliable scientific foundation for applying

Epimedin C to exert neuroprotective effects and prevent

neurodegenerative diseases.

In conclusion the present study revealed the

neuroprotective mechanism of Epimedin C. To the best of our

knowledge, the current findings are the first to indicate that

Epimedin C can mediate the JNK/Nrf2/HO-1 pathway, providing

protection from H2O2-mediated OS and

apoptosis in PC12 cells. These findings suggest that Epimedin C may

become a candidate drug for preventing neurodegenerative diseases.

In the future, further exploration of the potential preventive

mechanisms of Epimedin C in neurodegenerative diseases is needed to

provide more reliable and direct scientific evidence.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: This work was supported by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant nos. 82174427 and 82305290).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

CC and XLL were involved in writing the original

draft, and reviewing and editing the manuscript. CC was also

responsible for data curation, software application and data

analysis. XLL conceptualized and supervised the project. CC, XLL,

and GYL performed the experiments. GYL was responsible for data

analysis and software application. LWX was responsible for

conceptualization, project administration and funding acquisition.

GYL and LWX ultimately reviewed and edited the manuscript. CC, XLL,

GYL and LWX confirm the authenticity of all the raw data, and read

and approved the final manuscript. All authors agree to be

accountable for all aspects of work ensuring integrity and

accuracy.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Li R, Robinson M, Ding X, Geetha T,

Al-Nakkash L, Broderick TL and Babu JR: Genistein: A focus on

several neurodegenerative diseases. J Food Biochem.

46(e14155)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Bell SM, Burgess T, Lee J, Blackburn DJ,

Allen SP and Mortiboys H: Peripheral glycolysis in

neurodegenerative diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 21(8924)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Kovacs GG: Molecular pathology of

neurodegenerative diseases: Principles and practice. J Clin Pathol.

72:725–735. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Varela L and Garcia-Rendueles MER:

Oncogenic pathways in neurodegenerative diseases. Int J Mol Sci.

23(3223)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Orfali R, Alwatban AZ, Orfali RS, Lau L,

Chea N, Alotaibi AM, Nam YW and Zhang M: Oxidative stress and ion

channels in neurodegenerative diseases. Front Physiol.

15(1320086)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Chang KH, Cheng ML, Chiang MC and Chen CM:

Lipophilic antioxidants in neurodegenerative diseases. Clin Chim

Acta. 485:79–87. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Finkel T and Holbrook NJ: Oxidants,

oxidative stress and the biology of ageing. Nature. 408:239–247.

2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Li Y, Li L and Hölscher C: Therapeutic

potential of genipin in central neurodegenerative diseases. CNS

Drugs. 30:889–897. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Chen Q, Chen G and Wang Q: Application of

network pharmacology in the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases

with traditional Chinese medicine. Planta Med. 91:226–237.

2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Wang SF, Wu MY, Cai CZ, Li M and Lu JH:

Autophagy modulators from traditional Chinese medicine: Mechanisms

and therapeutic potentials for cancer and neurodegenerative

diseases. J Ethnopharmacol. 194:861–876. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Li XL, Lin ZH, Chen SR, Ni S, Lin GY, Wang

W, Lin JY, Zhao Q, Cong C and Xu LW: Tiaogeng decoction improves

mild cognitive impairment in menopausal APP/PS1 mice through the

ERs/NF-κ b/AQP1 signaling pathway. Phytomedicine.

138(156391)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Yang X, Chen J, Huang W, Zhang Y, Yan X,

Zhou Z and Wang Y: Synthesis of icariin in tobacco leaf by

overexpression of a glucosyltransferase gene from Epimedium

sagittatum. Ind Crop Prod. 156(112841)2020.

|

|

13

|

Li J, Yu Y, Zhang Y, Zhou Y, Ding S, Dong

S, Jin S and Li Q: Flavonoids derived from Chinese Medicine:

Potential neuroprotective agents. Am J Chin Med. 52:1613–1640.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Zhou M, Zheng W, Sun X, Yuan M, Zhang J,

Chen X, Yu K, Guo B and Ma B: Comparative analysis of chemical

components in different parts of Epimedium Herb. J Pharm Biomed

Anal. 198(113984)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Zhang HF, Yang XH, Zhao LD and Wang Y:

Ultrasonic-assisted extraction of epimedin C from fresh leaves of

Epimedium and extraction mechanism. Innovative Food Science &

Emerging Technologies. 54-60:1466–8564. 2009.

|

|

16

|

Luo D, Shi D and Wen L: From epimedium to

neuroprotection: Exploring the potential of wushanicaritin. Foods.

13(1493)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Li XA, Ho YS, Chen L and Hsiao WL: The

protective effects of icariin against the homocysteine-induced

neurotoxicity in the primary embryonic cultures of rat cortical

neurons. Molecules. 21(1557)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Chinese Pharmacopoeia Commission:

Pharmacopoeia of the People's Republic of China. Vol 1. China

Medical Science Press, Beijing, 2020.

|

|

19

|

Wu L, Du ZR, Xu AL, Yan Z, Xiao HH, Wong

MS, Yao XS and Chen WF: Neuroprotective effects of total flavonoid

fraction of the Epimedium koreanum Nakai extract on dopaminergic

neurons: In vivo and in vitro. Biomed Pharmacother. 91:656–663.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Zhang HF, Yang TS, Li ZZ and Wang Y:

Simultaneous extraction of epimedin A, B, C and icariin from Herba

Epimedii by ultrasonic technique. Ultrason Sonochem. 15:376–385.

2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Huang X, Wang X, Zhang Y, Shen L, Wang N,

Xiong X, Zhang L, Cai X and Shou D: Absorption and utilisation of

epimedin C and icariin from Epimedii herba, and the regulatory

mechanism via the BMP2/Runx2 signalling pathway. Biomed

Pharmacother. 118(109345)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Wei DH, Deng JL, Shi RZ, Ma L, Shen JM,

Hoffman R, Hu YH, Wang H and Gao JL: Epimedin C protects

H2O2-induced peroxidation injury by enhancing the function of

endothelial progenitor HUVEC populations. Biol Pharm Bull.

42:1491–1499. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Ohnuma K, Hayashi Y, Furue M, Kaneko K and

Asashima M: Serum-free culture conditions for serial subculture of

undifferentiated PC12 cells. J Neurosci Methods. 151:250–261.

2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Cheng B, Lu H, Bai B and Chen J:

d-β-Hydroxybutyrate inhibited the apoptosis of PC12 cells induced

by H2O2 via inhibiting oxidative stress. Neurochem Int. 62:620–625.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Gao X, Li S, Liu X, Cong C, Zhao L, Liu H

and Xu L: Neuroprotective effects of Tiaogeng decoction against

H2O2-induced oxidative injury and apoptosis in PC12 cells via Nrf2

and JNK signaling pathways. J Ethnopharmacol.

279(114379)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Zhao Y, Kuca K, Wu W, Wang X, Nepovimova

E, Musilek K and Wu Q: Hypothesis: JNK signaling is a therapeutic

target of neurodegenerative diseases. Alzheimers Dement.

18:152–158. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Cho H and Hah JM: A perspective on the

development of c-Jun N-terminal Kinase inhibitors as therapeutics

for Alzheimer's disease: Investigating structure through docking

studies. Biomedicines. 9(1431)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Osama A, Zhang J, Yao J, Yao X and Fang J:

Nrf2: A dark horse in Alzheimer's disease treatment. Ageing Res

Rev. 64(101206)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Wang M, Tong K, Chen Z and Wen Z:

Mechanisms of 15-Epi-LXA4-Mediated HO-1 in cytoprotection following

inflammatory injury. J Surg Res. 281:245–255. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Atabaki MM, Ghotbeddin Z, Rahimi K and

Tabandeh MR: The potential of alphapinene as a therapeutic agent

for maternal hypoxia-induced cognitive impairments: A study on HO-1

and Nrf2 gene expression in rats. Metab Brain Dis.

40(112)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Li J, Kuang G, Chen X and Zeng R:

Identification of chemical composition of leaves and flowers from

paeonia rockii by UHPLC-Q-exactive orbitrap HRMS. Molecules.

21(947)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Lozan E, Shinkaruk S, Al Abed SA, Lamothe

V, Potier M, Marighetto A, Schmitter JM, Bennetau-Pelissero C and

Buré C: Derivatization-free LC-MS/MS method for estrogen

quantification in mouse brain highlights a local metabolic

regulation after oral versus subcutaneous administration. Anal

Bioanal Chem. 409:5279–5289. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Guglielmotto M, Reineri S, Iannello A,

Ferrero G, Vanzan L, Miano V, Ricci L, Tamagno E, De Bortoli M and

Cutrupi S: E2 regulates epigenetic signature on neuroglobin

enhancer-promoter in neuronal cells. Front Cell Neurosci.

10(147)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Singh P and Paramanik V: Neuromodulating

roles of estrogen and phytoestrogens in cognitive therapeutics

through epigenetic modifications during aging. Front Aging

Neurosci. 14(945076)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Lin J, Wu J, Xu Y, Zhao Y and Ye S:

RhFGF21 protected PC12 cells against mitochondrial apoptosis

triggered by H2O2 via the AKT-mediated ROS signaling pathway. Exp

Cell Res. 445(114417)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Li Y, Long J, Li L, Yu Z, Liang Y, Hou B,

Xiang L and Niu X: Pioglitazone protects PC12 cells against

oxidative stress injury: An in vitro study of its antiapoptotic

effects via the PPARγ pathway. Exp Ther Med. 26(522)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Cheng Y, Huang X, Tang Y, Li J, Tan Y and

Yuan Q: Effects of evodiamine on ROS/TXNIP/NLRP3 pathway against

gouty arthritis. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol.

397:1015–1023. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Abedi A, Ghobadi H, Sharghi A, Iranpour S,

Fazlzadeh M and Aslani MR: Effect of saffron supplementation on

oxidative stress markers (MDA, TAC, TOS, GPx, SOD, and

pro-oxidant/antioxidant balance): An updated systematic review and

meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Front Med

(Lausanne). 10(1071514)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Satoh T, Enokido Y, Aoshima H, Uchiyama Y

and Hatanaka H: Changes in mitochondrial membrane potential during

oxidative stress-induced apoptosis in PC12 cells. J Neurosci Res.

50:413–420. 1997.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Perelman A, Wachtel C, Cohen M, Haupt S,

Shapiro H and Tzur A: JC-1: Alternative excitation wavelengths

facilitate mitochondrial membrane potential cytometry. Cell Death

Dis. 3(e430)2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Kyrylkova K, Kyryachenko S, Leid M and

Kioussi C: Detection of apoptosis by TUNEL assay. Methods Mol Biol.

887:41–47. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Protasoni M and Zeviani M: mitochondrial

structure and bioenergetics in normal and disease conditions. Int J

Mol Sci. 22(586)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Wang G, Zhao Z, Ren B, Yu W, Zhang X, Liu

J, Wang L, Si D and Yang M: Exenatide exerts a neuroprotective

effect against diabetic cognitive impairment in rats by inhibiting

apoptosis: Role of the JNK/c-JUN signaling pathway. Mol Med Rep.

25(111)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Kong R, Shi J, Xie K, Wu H, Wang X, Zhang

Y and Wang Y: A study of JUN's promoter region and its regulators

in chickens. Genes (Basel). 15(1351)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Huang HM and Liu JC: c-Jun blocks cell

differentiation but not growth inhibition or apoptosis of chronic

myelogenous leukemia cells induced by STI571 and by histone

deacetylase inhibitors. J Cell Physiol. 218:568–574.

2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Chen F, Xiao M, Hu S and Wang M:

Keap1-Nrf2 pathway: A key mechanism in the occurrence and

development of cancer. Front Oncol. 14(1381467)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Galan-Cobo A, Sitthideatphaiboon P, Qu X,

Poteete A, Pisegna MA, Tong P, Chen PH, Boroughs LK, Rodriguez MLM,

Zhang W, et al: LKB1 and KEAP1/NRF2 pathways cooperatively promote

metabolic reprogramming with enhanced glutamine dependence in

KRAS-mutant lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 79:3251–3267.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Buendia I, Michalska P, Navarro E, Gameiro

I, Egea J and León R: Nrf2-ARE pathway: An emerging target against

oxidative stress and neuroinflammation in neurodegenerative

diseases. Pharmacol Ther. 157:84–104. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Xiao Q, Piao R, Wang H, Li C and Song L:

Orientin-mediated Nrf2/HO-1 signal alleviates H2O2-induced

oxidative damage via induction of JNK and PI3K/AKT activation. Int

J Biol Macromol. 118 (Pt A):747–755. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Feng L, Wu Y, Wang J, Han Y, Huang J and

Xu H: Neuroprotective effects of a novel tetrapeptide SGGY from

Walnut against H2O2-Stimulated oxidative stress in SH-SY5Y cells:

Possible involved JNK, p38 and Nrf2 signaling pathways. Foods.

12(1490)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Kuntić M, Hahad O, Münzel T and Daiber A:

Crosstalk between oxidative stress and inflammation caused by noise

and air pollution-implications for neurodegenerative diseases.

Antioxidants (Basel). 13(266)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Downs BW, Kushner S, Bagchi M, Blum K,

Badgaiyan RD, Chakraborty S and Bagchi D: Etiology of

neuroinflammatory pathologies in neurodegenerative diseases: A

treatise. Curr Psychopharmacol. 10:123–137. 2021.

|

|

53

|

Li Y, Zhang W, Zhang Q, Li Y, Xin C, Tu R

and Yan H: Oxidative stress of mitophagy in neurodegenerative

diseases: Mechanism and potential therapeutic targets. Arch Biochem

Biophys. 764(110283)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Pardillo-Díaz R, Pérez-García P, Castro C,

Nunez-Abades P and Carrascal L: Oxidative stress as a potential

mechanism underlying membrane hyperexcitability in

neurodegenerative diseases. Antioxidants (Basel).

11(1511)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Kim S, Jung UJ and Kim SR: Role of

oxidative stress in blood-brain barrier disruption and

neurodegenerative diseases. Antioxidants (Basel).

13(1462)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Tarozzi A: Oxidative stress in

neurodegenerative diseases: From preclinical studies to clinical

applications. J Clin Med. 9(1223)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Shams Ul Hassan S, Ishaq M, Zhang WD and

Jin HZ: An overview of the mechanisms of marine Fungi-derived

anti-inflammatory and anti-tumor agents and their novel role in

drug targeting. Curr Pharm Des. 27:2605–2614. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Cai Z, Liu M, Zeng L, Zhao K, Wang C, Sun

T, Li Z and Liu R: Role of traditional Chinese medicine in

ameliorating mitochondrial dysfunction via non-coding RNA

signaling: Implication in the treatment of neurodegenerative

diseases. Front Pharmacol. 14(1123188)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Mohd Sairazi NS and Sirajudeen KNS:

Natural products and their bioactive compounds: Neuroprotective

potentials against neurodegenerative diseases. Evid Based

Complement Alternat Med. 2020(6565396)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Chen L, Liu Y and Xie J: The beneficial

pharmacological effects of Uncaria rhynchophylla in

neurodegenerative diseases: Focus on alkaloids. Front Pharmacol.

15(1436481)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Wang ZY, Liu J, Zhu Z, Su CF,

Sreenivasmurthy SG, Iyaswamy A, Lu JH, Chen G, Song JX and Li M:

Traditional Chinese medicine compounds regulate autophagy for

treating neurodegenerative disease: A mechanism review. Biomed

Pharmacother. 133(110968)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Chen XL, Li SX, Ge T, Zhang DD, Wang HF,

Wang W, Li YZ and Song XM: Epimedium Linn: A comprehensive review

of phytochemistry, pharmacology, clinical applications and quality

control. Chem Biodivers. 21(e202400846)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Li C, Li Q, Mei Q and Lu T:

Pharmacological effects and pharmacokinetic properties of icariin,

the major bioactive component in Herba Epimedii. Life Sci.

126:57–68. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Zong N, Li F, Deng Y, Shi J, Jin F and

Gong Q: Icariin, a major constituent from Epimedium brevicornum,

attenuates ibotenic acid-induced excitotoxicity in rat hippocampus.

Behav Brain Res. 313:111–119. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Liu F, Wei B, Cheng L, Zhao Y, Liu X, Yuan

Q and Liang H: Co-Immobilizing two glycosidases based on

cross-linked enzyme aggregates to enhance enzymatic properties for

achieving high titer Icaritin biosynthesis. J Agric Food Chem.

70:11631–11642. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Yang J, Yang J, Liang SH, Xu Y, Moore A

and Ran C: Imaging hydrogen peroxide in Alzheimer's disease via

cascade signal amplification. Sci Rep. 6(35613)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

67

|

Gharai PK, Khan J, Mallesh R, Garg S, Saha

A and Ghosh S and Ghosh S: Vanillin benzothiazole derivative

reduces cellular reactive oxygen species and detects amyloid

fibrillar aggregates in Alzheimer's disease brain. ACS Chem

Neurosci. 14:773–786. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

68

|

Sajjad N, Wani A, Sharma A, Ali R, Hassan

S, Hamid R, Habib H and Ganai BA: Artemisia amygdalina Upregulates

Nrf2 and protects neurons against oxidative stress in Alzheimer

disease. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 39:387–399. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

69

|

Zakharova IO, Sokolova TV, Furaev VV,

Rychkova MP and Avrova NF: (Effects of oxidative stress inducers,

neurotoxins, and ganglioside GM1 on Na+, K+-ATPase in PC12 and

brain synaptosomes). Zh Evol Biokhim Fiziol. 43:148–154.

2007.PubMed/NCBI(In Russian).

|

|

70

|

Demirci-Çekiç S, Özkan G, Avan AN, Uzunboy

S, Çapanoğlu E and Apak R: Biomarkers of oxidative stress and

antioxidant defense. J Pharm Biomed Anal.

209(114477)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

71

|

Pisoschi AM and Pop A: The role of

antioxidants in the chemistry of oxidative stress: A review. Eur J

Med Chem. 97:55–74. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

72

|

Zhang R, Guo X, Zhang Y and Tian C:

Influence of modified atmosphere treatment on post-harvest reactive

oxygen metabolism of pomegranate peels. Nat Prod Res. 34:740–744.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

73

|

González-Rubio G, Sellers-Moya Á, Martín H

and Molina M: A walk-through MAPK structure and functionality with

the 30-year-old yeast MAPK Slt2. Int Microbiol. 24:531–543.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

74

|

Miloso M, Scuteri A, Foudah D and Tredici

G: MAPKs as mediators of cell fate determination: An approach to

neurodegenerative diseases. Curr Med Chem. 15:538–548.

2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

75

|

Du J, Wang G, Luo H, Liu N and Xie J:

JNK-IN-8 treatment alleviates lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung

injury via suppression of inflammation and oxidative stress

regulated by JNK/NF-κB signaling. Mol Med Rep. 23(150)2021.

|

|

76

|

Li R, Yang W, Yan X, Zhou X, Song X, Liu

C, Zhang Y and Li J: Folic acid mitigates the developmental and

neurotoxic effects of bisphenol A in zebrafish by inhibiting the

oxidative stress/JNK signaling pathway. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf.

288(117363)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

77

|

Shakya A, McKee NW, Dodson M, Chapman E

and Zhang DD: Anti-ferroptotic effects of Nrf2: Beyond the

antioxidant response. Mol Cells. 46:165–175. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

78

|

Hallis SP, Kim JM and Kwak MK: Emerging

role of NRF2 signaling in cancer stem cell phenotype. Mol Cells.

46:153–164. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

79

|

Huang SY, Chang SF, Chau SF and Chiu SC:

The protective effect of hispidin against hydrogen peroxide-induced

oxidative stress in ARPE-19 cells via Nrf2 signaling pathway.

Biomolecules. 9(380)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

80

|

Li S, Cong C, Liu Y, Liu X, Liu H, Zhao L,

Gao X, Gui W and Xu L: Tiao Geng decoction inhibits tributyltin

chloride-induced GT1-7 neuronal apoptosis through ASK1/MKK7/JNK

signaling pathway. J Ethnopharmacol. 269(113669)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

81

|

Li S, Cong C, Liu Y, Liu X, Kluwe L, Shan

X, Liu H, Gao M, Zhao L, Gao X and Xu L: Tiao Geng decoction for

treating menopausal syndrome exhibits anti-aging effects likely via

suppressing ASK1/MKK7/JNK mediated apoptosis in ovariectomized

rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 261(113061)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

82

|

Ryan J, Scali J, Carriere I, Ritchie K and

Ancelin ML: Hormonal treatment, mild cognitive impairment and

Alzheimer's disease. Int Psychogeriatr. 20:47–56. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

83

|

Li C, Jia WW, Yang JL, Cheng C and Olaleye

OE: Multi-compound and drug-combination pharmacokinetic research on

Chinese herbal medicines. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 43:3080–3095.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

84

|

Chen L, Zhen Y, Wang X, Wang J and Zhu G:

Neurovascular glial unit: A target of phytotherapy for cognitive

impairments. Phytomedicine. 119(155009)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

85

|

Sharma S, Mehan S, Khan Z, Tiwari A, Kumar

A, Gupta GD, Narula AS and Kalfin R: Exploring the neuroprotective

potential of icariin through modulation of neural pathways in the

treatment of neurological diseases. Curr Mol Med: Sep 26, 2024

(Epub ahead of print).

|

|

86

|

Zhang Y, Wang Y, Zhang X, Liu Y, Li J and

Wang J: Metabolic profiling of epimedin C in Rats: In vivo and in

vitro studies. Front. Pharmacol. 9(456)2018.

|

|

87

|

Wong SP, Shen P, Lee L, Li J and Yong EL:

Pharmacokinetics of prenylflavonoids and correlations with the

dynamics of estrogen action in sera following ingestion of a

standardized Epimedium extract. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 50:216–223.

2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

88

|

Xie L, Zhao S, Zhang X, Huang W, Qiao L,

Zhan D, Ma C, Gong W, Dang H and Lu H: Wenshenyang recipe treats

infertility through hormonal regulation and inflammatory responses

revealed by transcriptome analysis and network pharmacology. Front

Pharmacol. 13(917544)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

89

|

Hara Y, Waters EM, McEwen BS and Morrison

JH: estrogen effects on cognitive and synaptic health over the

lifecourse. Physiol Rev. 95:785–807. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

90

|

Uddin MS, Rahman MM, Jakaria M, Rahman MS,

Hossain MS, Islam A, Ahmed M, Mathew B, Omar UM, Barreto GE and

Ashraf GM: Estrogen signaling in Alzheimer's disease: Molecular

Insights and therapeutic targets for Alzheimer's dementia. Mol

Neurobiol. 57:2654–2670. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

91

|

Dubal DB, Zhu H, Yu J, Rau SW, Shughrue

PJ, Merchenthaler I, Kindy MS and Wise PM: Estrogen receptor alpha,

not beta, is a critical link in estradiol-mediated protection

against brain injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 98:1952–1957.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

92

|

Li B, Lima MRM, Nie Y, Xu L, Liu X, Yuan

H, Chen C, Dias AC and Zhang X: HPLC-DAD fingerprints combined with

multivariate analysis of epimedii folium from major producing areas

in eastern Asia: Effect of geographical origin and species. Front

Pharmacol. 12(761551)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

93

|

Lee D, Jeong HC, Kim SY, Chung JY, Cho SH,

Kim KA, Cho JH, Ko BS, Cha IJ, Chung CG, et al: A comparison study

of pathological features and drug efficacy between Drosophila

models of C9orf72 ALS/FTD. Mol Cells. 47(100005)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|