Introduction

Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms

(GEP-NENs) are a heterogeneous group of tumours that originate from

neuroendocrine cells within the gastrointestinal tract and

pancreas, which possess hormone-secreting functions (1). Within the gastrointestinal tract,

these cells are responsible for the secretion of digestive hormones

such as gastrin, glucagon and secretin. In the pancreas, the

endocrine cell population includes islet cells (such as α-cells and

β-cells), which produce hormones, such as insulin and glucagon

(2). In the 5th Edition of the

World Health Organization (WHO) classification of digestive system

tumours published in 2019(3),

GEP-NENs were classified as well-differentiated neuroendocrine

tumours (NET) grade 1 (NET G1), NET grade 2 (NET G2) and poorly

differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC), with a high-grade

designation defined by a Ki-67 proliferation index of >20% and a

mitotic count of >20 per 2 mm2. This classification

system further stratified GEP-NENs into low-grade (LG) NENs,

including NET G1 and NET G2, and high-grade (HG) NENs, including

NET grade 3 (NET G3) and NEC. In the HG group, NET G3 (previously

referred to as ‘high-proliferative NET’) are classified as

well-differentiated neoplasms exhibiting morphological features

similar to LG NET, but with a Ki-67 proliferation index of >20%

(typically <55%). By contrast, NEC is characterised as a poorly

differentiated, high-grade malignancy composed of either small or

large cells, including small cell NEC (SCNEC) and large-cell NEC

(LCNEC).

Further subclassification of NET G3 or NEC with a

Ki-67 proliferation index of >20% may be necessary (4-6).

Notable differences in biological behaviour, treatment approaches

and prognosis have been observed between NET G3 subgroups with

Ki-67 index values of 20-55% and those with >55%. For instance,

the subgroup with a Ki-67 >55% is associated with significantly

shorter median overall survival time and typically requires

platinum-based chemotherapy, unlike the subgroup with a Ki-67 of

20-55%, which is managed with systemic non-platinum regimens

(5-8).

Despite the existence of well-defined criteria, HG-NENs exhibit

substantial heterogeneity owing to the distinct pathological and

molecular characteristics. These molecular differences, which are

explored in the following section, fundamentally underpin the

pathological distinction between well-differentiated NET G3 and

poorly differentiated NEC (9-11).

These histological subtypes vary considerably in epidemiology,

treatment strategies and clinical outcomes, reflecting their

diverse biological behaviours (3).

Advances in tumour immunology and molecular pathology have led to

the development of novel therapeutic approaches for HG-GEP NENs,

including molecular targeted therapies and immune checkpoint

inhibitors, such as programmed cell death protein 1 inhibitors

(12). However, the selection and

evaluation of appropriate treatment options require a comprehensive

assessment of multiple factors, such as tumour grade and stage,

cellular differentiation, primary tumour site, Ki-67 proliferation

index, molecular and immunohistochemical markers and NEC

subtype.

Advancements in molecular pathology have indicated

that HG-NENs have distinct molecular pathogenic mechanisms.

Whole-genome studies have identified at least four functional

pathways implicated in the molecular alterations of pancreatic NET:

DNA damage repair (involving genes such as MUTYH, CHEK2 and

BRCA2), chromatin remodelling (including ARID1A and

SMARCA4), telomere maintenance (notably DAXX and

ATRX genes) and the PI3K/mechanistic target of rapamycin

signalling pathway (involving EWSR fusion, PTEN and

HIF1/2) (10,11,13,14).

In rectal NET, recurrent mutations have been reported in genes such

as TP53, PTEN, CDKN2A, FBXW7 and

AKT1, with the mutational burden shown to increase with

tumour grade. However, the specific roles of the Ras/Raf/MAPK and

PI3K/AKT pathways in the pathogenesis of rectal NET remain unclear

(14-16).

Conversely, NEC exhibit entirely different molecular profiles from

GEP-NET. The most frequently altered genes in GEP-NEC include

TP53, RB1, KRAS, BRAF and APC.

In GEP-NET, RB1 mutations are absent (14,17,18).

While recurrent TP53 mutations have been identified in

certain subtypes, such as rectal NET, they remain uncommon across

the broader spectrum of GEP-NET; when present outside the rectum,

they are typically confined to a subset of NET G3(16).

CHEK1 is a crucial protein-coding gene in the

human genome (19). CHEK1

functions as a key regulatory factor involved in cell cycle

control, DNA damage repair and apoptosis inhibition (19-21);

this is essential for proper cell division and the maintenance of

genomic stability. The CHEK1-encoded protein belongs to the

protein kinase family and primarily monitors and facilitates DNA

damage repair within cells. CHEK1 has been implicated in

various malignancies (20-22),

including colorectal cancer (23),

multiple myeloma (24),

hepatocellular carcinoma (25),

lung adenocarcinoma (26) and lung

squamous cell carcinoma (27).

CHEK1 exhibits a dual role in tumour progression: While it

functions as a tumour suppressor in normal physiology by

safeguarding genomic integrity, it is paradoxically co-opted in the

neoplastic state to promote cell survival and induce therapy

resistance. Aberrant activation or overexpression of CHEK1

can suppress apoptosis and promote DNA repair, thereby enhancing

tumour cell survival and increasing resistance to therapeutic

interventions (19,20).

Over the years, CHEK1 has received

considerable attention in the field of tumour biology and the

development of therapeutic strategies, emerging as a potential

therapeutic target (21,22,28,29).

Several CHEK1-targeted inhibitors have been developed,

including SRA737(28), MK-8776

(VX-970) (29), LY2603618(21), AZD7762(30) and LY2606368(27). These inhibitors disrupt the tumour

cell cycle, thereby suppressing tumour cell proliferation, and have

been experimentally validated in various malignancies.

Specifically, LY2606368, AZD7762 and SRA737 have demonstrated

efficacy in preclinical models of gastrointestinal tumours,

including colorectal cancer, pancreatic cancer, GEP-NENs and small

cell lung cancer. Additionally, MK-8776 (VX-970), LY2603618 and

AZD7762 have demonstrated therapeutic potential in in vitro

and in vivo models of digestive system tumours (21,27-30).

The ability of CHEK1 inhibitors to effectively suppress

tumour cell growth and migration underscores their potential as

viable therapeutic agents.

Despite its well-established role in various

malignancies, the involvement of CHEK1 in HG-GEP NENs

remains largely uncharacterised. Previous studies have highlighted

the dual role of CHEK1 in tumourigenesis. The same

mechanism, CHEK1-mediated cell-cycle arrest, serves opposite

purposes. In normal cells it functions as a tumour-suppressive

process that preserves genomic integrity by permitting DNA repair,

whereas in cancer cells it is co-opted as a pro-survival mechanism

that enables tumour cells to withstand replication stress or

therapeutic pressure (19,21). Given the dual role of CHEK1

as a key regulatory protein downstream of MEK/ERK signalling

(31) and as a central effector of

the DNA-damage response (19), the

CHEK1 overexpression observed in NEC, an attribute

correlated with aggressive behaviour, supports its potential

utility as a molecular biomarker for subtyping HG-GEP NENs

(12).

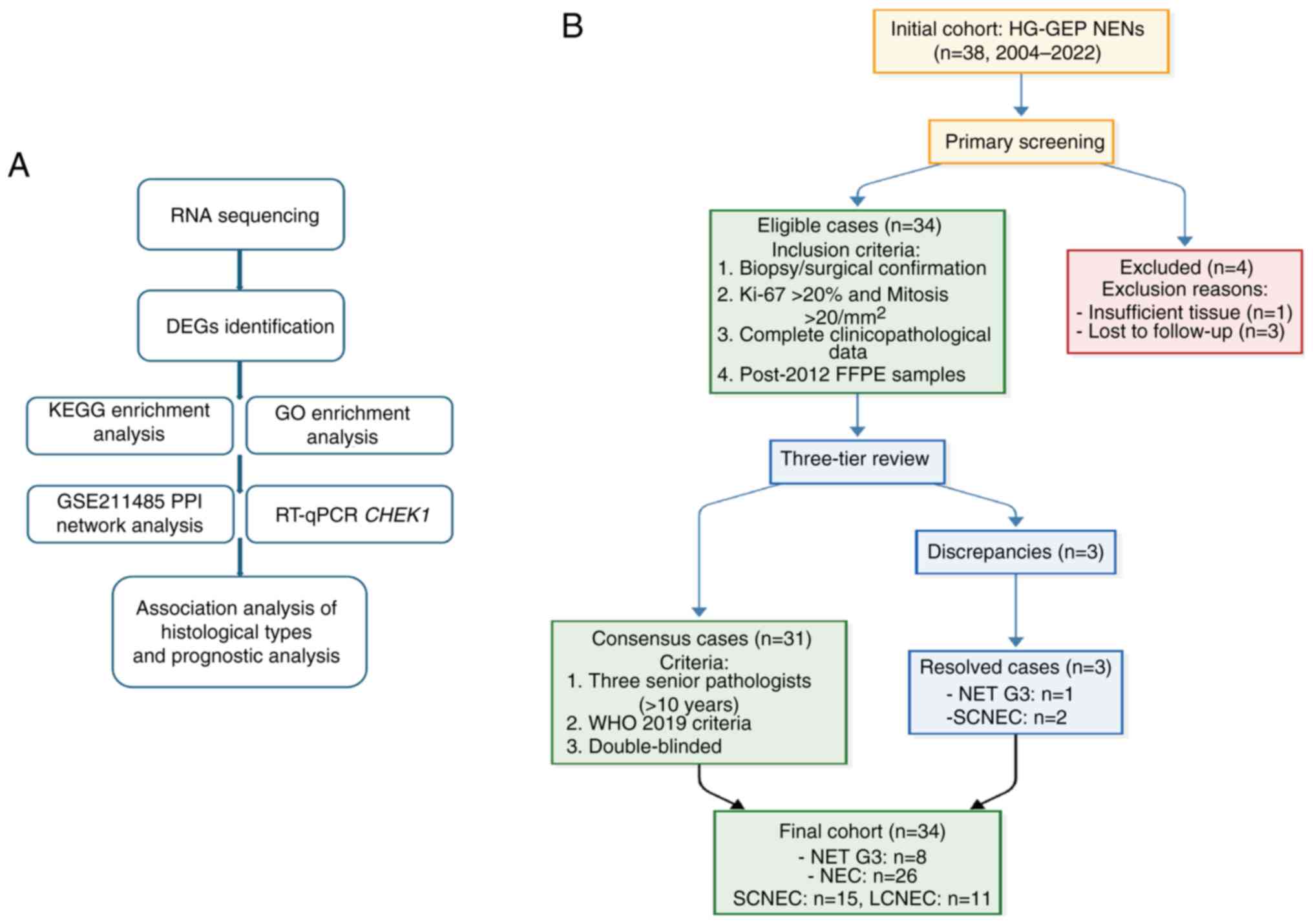

The present study aimed to elucidate the clinical

and biological significance of CHEK1 in HG-GEP NENs, using a

combination of public transcriptomic data [Gene Expression Omnibus

(GEO): GSE211485] and an institutional cohort of 38 patient-derived

formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue samples.

Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were initially identified

through transcriptomic analysis, followed by validation of

CHEK1 expression in tumour tissue samples. An overview of

the study workflow is illustrated in Fig. 1A. Furthermore, the potential role

of CHEK1 in the pathogenesis and progression of HG-GEP NENs

was explored through associations with histological subtypes and

clinicopathological parameters. The specific objectives of the

present study were to: i) Determine the differential expression of

CHEK1 among histologically distinct HG-GEP NENs subtypes;

ii) explore its potential contribution to tumour biology; iii)

assess its diagnostic and prognostic utility; and iv) provide a

rationale for the future development of CHEK1-targeted

therapeutic strategies in this rare but aggressive disease.

| Figure 1Workflow diagram and case selection

flowchart. (A) Workflow of the study. (B) Case inclusion and

screening flowchart. DEGs, differentially expressed genes; KEGG,

Kyoto Encyclopaedia of Genes and Genomes; GO, Gene Ontology; PPI,

protein-protein interaction; RT-qPCR, reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR; HG-GEP NENs, high-grade

gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms; FFPE,

formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded; NET G3, neuroendocrine tumour

grade 3; NEC, neuroendocrine carcinoma; SCNEC, small cell NEC;

LCNEC, large-cell NEC; WHO, World Health Organisation;

CHEK1, checkpoint kinase 1. |

Materials and methods

Patient selection

The present study consecutively enrolled 38 patients

with HG-GEP NENs who underwent diagnostic or therapeutic procedures

(biopsy, puncture, surgery and/or consultation) at Beijing Luhe

Hospital, Capital Medical University (Beijing, China) between

January 2004 and May 2022. Inclusion criteria were as follows: i)

Histopathologically confirmed HG-GEP NENs according to the WHO

Classification Of Tumours Of The Digestive System (5th Edition,

2019) (3); ii) availability of

complete clinical data with a follow-up duration of >1 year; and

iii) availability of FFPE tumour tissue samples obtained after 2012

for molecular analysis. Patients not meeting all these criteria

were excluded. The FFPE tissues obtained during routine clinical

practice throughout this period were utilized for analysis. The

cohort consisted of 9 patients with NET G3 (7 male patients and 2

female patients; median age, 66.0±12.4 years). In addition, the

cohort also consisted of 29 patients with NEC who were further

stratified into: i) LCNEC, 11 cases (5 male patients and 6 female

patients; median age, 65.0±12.1 years); and ii) SCNEC, 18 cases (10

male patients and 8 female patients; median age, 65.0±9.6 years).

The overall population included 22 male patients and 16 female

patients (age range, 43-86 years; median age, 65.0±10.6 years). All

patients were independently reviewed and classified by three senior

pathologists according to the diagnostic criteria of the WHO

classification of tumours of the digestive system (5th edition,

2019) (3). Any diagnostic

discrepancies were resolved through multitiered consensus

discussions (Fig. 1B).

Pathological grading was performed based on comprehensive

histopathological evaluation. Clinical follow-up data regarding

recurrence, metastasis and survival status were obtained through

telephone interviews, with the follow-up period extending from the

date of initial tumour diagnosis until patient death. Complete

follow-up data were available for 35 patients, while 3 cases were

lost to follow-up. A total of 23 deaths were documented. Ethics

approval was provided by the Institutional Review Board of Beijing

Luhe Hospital, Capital Medical University (approval no.

2024-LHKY-107-01).

Identification of DEGs

Soldevilla et al (32) conducted transcriptome analyses via

next-generation sequencing on a cohort comprising 84 tumour tissue

samples from NENs of pulmonary and GEP origin. The resulting gene

dataset (GSE211485) was made publicly available through the GEO

database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). In that study, 15

patients diagnosed with GEP NET-G1 and GEP NET-G2 were assigned to

the LG-GEP NENs group, whereas 2 patients diagnosed with GEP-NEC

were assigned to the HG-GEP NENs group. The present study analysed

this dataset and DEG expression was assessed using R Studio

(version 2023.12.1+402; Posit Software, PBC, Boston, MA, USA) and

DESeq2 (version 1.40.2; Bioconductor Project). In this DESeq2 model

where the HG-GEP NENs group served as the baseline, a negative

log2FC indicates lower expression in the LG-GEP NENs group relative

to the HG-GEP NENs group, signifying upregulation in the high-grade

tumours. Batch effects were corrected using variance stabilising

transformation. DEGs were identified based on dual screening

criteria to ensure result reliability: i) Absolute log2 fold change

(FC) >1 with a false discovery rate of <0.05; and ii) FC>2

or <0.5 with P<0.05.

Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto

Encyclopaedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analysis

GO and KEGG enrichment analyses of the identified

DEGs were performed using the R package ClusterProfiler. GO

enrichment analysis (http://geneontology.org/) was conducted across three

domains: Biological processes, cellular components and molecular

functions. KEGG enrichment analysis (https://www.genome.jp/kegg/) was performed to evaluate

five domains: Metabolic pathways, signalling pathways,

disease-related pathways, drug metabolism pathways and cellular

processes.

Protein-protein interaction (PPI)

network analysis

The identified DEGs were subjected to PPI network

analysis. Network visualisation was conducted using the Search Tool

for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins database (version

12.0; https://string-db.org). Hub genes were

identified using the CytoHubba plugin in Cytoscape (v3.10.1;

https://cytoscape.org).

Prognostic analysis

A comprehensive analysis was conducted using data

from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/), utilizing the

TCGA-COAD and TCGA-READ datasets. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis

was performed using the R package survival (version 3.5-7;

https://cran.r-project.org/package=survival), with

patients stratified into high- and low-expression groups based on

the median expression level. The diagnostic performance of these

genes was examined using receiver operating characteristic (ROC)

curve analysis with the R package pROC (version 1.18.4; https://cran.r-project.org/package=pROC). Based on

these prognostic and diagnostic analyses, CHEK1 was

identified as the key target gene with significant diagnostic and

prognostic value.

Figures derived from TCGA-COAD and TCGA-READ were

generated using the GEPIA2 online analysis platform (http://gepia2.cancer-pku.cn/).

RNA extraction and reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) detection

FFPE samples of patients diagnosed with HG-GEP NENs

after 2012 were selected for CHEK1 molecular detection. Four

samples from patients diagnosed prior to 2012 (three SCNEC and one

NET G3) were excluded from subsequent molecular analyses due to

insufficient RNA quality or quantity, resulting in 34 cases being

included in the RT-qPCR experiments. RNA was extracted from FFPE

tissue samples using the Nucleic Acid Extraction Reagent (Model:

FFPE RNA; cat. no. 8.02.0019; Xiamen Moyd Biotechnology Co., Ltd.,)

according to the manufacturer's protocol. Sections 5-10 µm in

thickness were placed in 1.5 ml DNase-/RNase-free centrifuge tubes.

To remove paraffin, 1 ml xylene was added to each tube, followed by

vortex mixing for 10 sec and incubation at 56˚C for 3 min. After a

second vortex mix, the samples were centrifuged at 13,000 x g for 2

min at 24˚C, and the supernatant was discarded. This step was

repeated if necessary to ensure complete deparaffinization.

Dehydration was then performed by adding 1 ml absolute ethanol,

vortexing and centrifuging at 13,000 x g for 2 min at 24˚C, after

which the supernatant was discarded. The pellets were air-dried at

56˚C until no ethanol residue remained. For RNA purification,

tissue lysis and digestion were initiated by adding 160 µl Buffer

RTL and 20 µl Proteinase K Solution to the pellets. The samples

were vortexed, briefly centrifuged at 13,000 x g for 10-15 sec at

24˚C and incubated at 56˚C for 30 min with agitation at 500 rpm,

followed by a second incubation at 80˚C for 30 min with agitation

at 500 rpm. After cooling to room temperature (~24˚C), on-site

prepared DNase I working mixture (30 µl per sample) was added to

digest genomic DNA, and the samples were incubated at 37˚C for 15

min. After centrifugation at 13,000 x g for 3 min at 24˚C, the

entire supernatant was transferred to a new tube. A total of 340 µl

Buffer RPB and 750 µl absolute ethanol was added, and the mixture

was vortexed. The solution was transferred to an RNA spin column

and centrifuged at 13,000 x g for 30 sec at 24˚C. The flow-through

was discarded. The remaining solution was loaded and centrifuged

again under the same conditions. The column was then washed

sequentially with 600 µl Wash Buffer A and 600 µl Wash Buffer B,

with centrifugation at 13,000 x g for 30 sec at 24˚C after each

wash. After a final centrifugation at 13,000 x g for 3 min at 24˚C

to dry the membrane, the RNA was eluted with 80-100 µl Buffer RTE

mixture by incubation at 56˚C for 2 min and centrifugation at

13,000 x g for 1 min at 24˚C. The purified RNA was dissolved in

RNase-free water, and its concentration and purity (A260/A280) were

determined using a SMA4000 spectrophotometer (Merinton Instrument,

Ltd.). cDNA was synthesized from the purified RNA using the

TransScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (TransGen Biotech Co., Ltd.)

according to the manufacturer's instructions. The reaction was

performed under the following thermocycling conditions: 25˚C for 10

min, 42˚C for 15 min and 85˚C for 5 sec, followed by hold at 4˚C.

For qPCR, each reaction contained 2 µl cDNA template, 10 µl SYBR

Green qPCR Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.), 0.4 µM of

each forward and reverse primer and RNase-free water up to a total

volume of 20 µl. The thermocycling conditions were as follows:

Initial denaturation at 95˚C for 3 min, followed by 40 cycles of

95˚C for 15 sec, 60˚C for 30 sec and 72˚C for 30 sec. Amplification

specificity was verified through melting curve analysis. A

no-template control was included in each run to monitor potential

contamination of the reaction. Target gene expression was

normalised to the reference gene (GAPDH) threshold value,

and the relative gene expression level was calculated using the

2-ΔΔCq method (33).

The primer sequences used for amplification of the

target gene CHEK1 and the reference gene GAPDH were

as follows: CHEK1 forward, 5'-GTGTCAGAGTCTCCCAGTGGAT-3' and

reverse, 5'-GTTCTGGCTGAGAACTGGAGTAC-3'; and GAPDH forward,

5'-GGTGGTCTCCTCTGACTTCAACA-3' and reverse,

5'-GTTGCTGTAGCCAAATTCGTTGT-3'.

Statistical analysis

Transcriptomic (TPM) and corresponding clinical data

were obtained from TCGA-COAD and TCGA-READ datasets, which were

used as representative cohorts of digestive system tumours. Samples

annotated as ‘solid tissue normal’ were included as adjacent

non-tumourous tissues. As the numbers of tumour and normal samples

were not identical, the comparison of CHEK1 expression

between tumour and adjacent normal tissues was performed using an

unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test. Statistical analyses were

performed using SPSS (version 29.0; IBM Corp.) and R Studio

(version 2023.12.1+402; Posit Software). Categorical variables are

presented as number (n) and percentage (%), while continuous

variables are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) or

median with interquartile range (IQR), as appropriate. For

categorical analysis, gene expression levels were dichotomized into

‘high’ and ‘low’ groups based on the median expression value of the

entire cohort. Descriptive statistics, including χ2 and

Fisher's exact tests were employed for data summarization and

clinicopathological associations. Comparisons of continuous

variables between two groups were performed using an unpaired

two-tailed Student's t-test. For CHEK1 quantitative analysis

in the present cohort, which did not meet the assumptions of

parametric tests, non-parametric tests were applied. Specifically,

the Mann-Whitney U test was used for two-group comparisons, and the

Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn's post hoc test was used for

comparisons across multiple groups. Survival assessment was

conducted using Kaplan-Meier analysis and log-rank tests, whereas

diagnostic performance was evaluated by ROC curve analysis. A post

hoc power analysis was performed based on the quantitative RT-qPCR

data of CHEK1 expression using the R pwr package (effect

size d=1.5), which demonstrated 65% statistical power. P<0.05

was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

Patients

A total of 38 patients with HG-GEP NENs were

included in the present study, comprising 9 patients (23.7%) with

NET G3 and 29 patients (76.3%) with NEC. The NEC group was further

subdivided into 11 patients (37.9% of NEC) with LCNEC and 18

patients (62.1% of NEC) with SCNEC. Complete follow-up data were

available for 35 patients (92.1%), whereas data for 2 patients

(5.3%) with NEC and 1 patient (2.6%) with NET G3 were unavailable.

The median survival time for the entire cohort was 10.0 months

(IQR, 5.0-25.0 months). When stratified by histological subtype,

the median survival time was 25.0 months (IQR, 15.5-42.0 months)

for the NET G3 group and 10.0 months (IQR, 5.0-21.5 months) for the

NEC group. Analysis of clinicopathological data was conducted as

described in our previous study (34). Immunohistochemical markers CLU and

TP53 significantly impacted survival outcomes, with CLU serving as

an independent prognostic factor. The immunohistochemical profile

provided diagnostic value for NET G3 subtyping, while conventional

demographic factors showed no significant associations with

survival.

Identification of DEGs

Specimens from 17 patients were analysed from the

GSE211485 dataset, including 15 patients with LG-GEP NENs and 2

patients with HG-GEP NENs. The baseline clinical characteristics of

the patients are presented in Table

I. Using DESeq2 with the HG-GEP NENs group designated as the

baseline, a total of 18,591 genes were assessed. Comparative

analysis identified 6 of these genes that were significantly

upregulated in the HG-GEP NENs group compared with those in the

LG-GEP NENs group (Fig. 2A;

Table II). The complete list of

these upregulated DEGs is provided in Table II.

| Table IClinical characteristics of the

patients from the GSE211485 dataset. |

Table I

Clinical characteristics of the

patients from the GSE211485 dataset.

| Characteristic | LG-GEP NENs | HG-GEP NENs |

|---|

| Grade | GEP NET-G1 | GEP NET-G2 | GEP NEC |

|---|

| Patient number | 7 | 8 | 2 |

| Sex (male/female),

n | 5/2 | 2/6 | 2/0 |

| Primary tumour

site | | | |

| Small

intestine | 2 | 4 | 0 |

| Colon and

rectum | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Stomach | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Pancreas | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Appendix | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Survival

status | | | |

| Alive | 6 | 5 | 0 |

| Deceased | 1 | 3 | 2 |

| Table IISignificantly upregulated DEGs in

HG-GEP NENs compared with LG-GEP NENs. |

Table II

Significantly upregulated DEGs in

HG-GEP NENs compared with LG-GEP NENs.

| Gene ID | Adjusted

P-value | P-value | Log2 fold

change |

|---|

| CENPF | 0.0000298 |

1.25x10-9 | -2.1162718 |

| CHEK1 | 0.0015899 |

1.52x10-7 | -1.1901370 |

| RGPD3 | 0.0015899 |

2.00x10-7 | -1.6814988 |

| UBE2T | 0.0057300 |

9.60x10-7 | -1.6553494 |

| E2F7 | 0.0210587 |

4.41x10-6 | -1.0386288 |

| ITGB3BP | 0.0465996 |

1.10x10-5 | -1.3835926 |

GO and KEGG enrichment analysis of

DEGs

GO enrichment analysis demonstrated significant

enrichment of DEGs in biological processes related to ‘centromere

complex assembly’, ‘negative regulation of mitotic cell cycle’ and

‘negative regulation of mitotic cell cycle phase transition’;

cellular components related to ‘condensed chromosome’, ‘chromosomal

region’ and ‘kinetochore’; and molecular functions related to

‘protein C-terminus binding’, ‘dynein complex binding’, and

‘histone kinase activity’. KEGG enrichment analysis revealed

substantial enrichment in pathways associated with ‘Cell cycle’,

‘p53 signalling pathway’ and ‘Fanconi anemia pathway’ (Fig. 2B).

PPI network analysis of DEGs

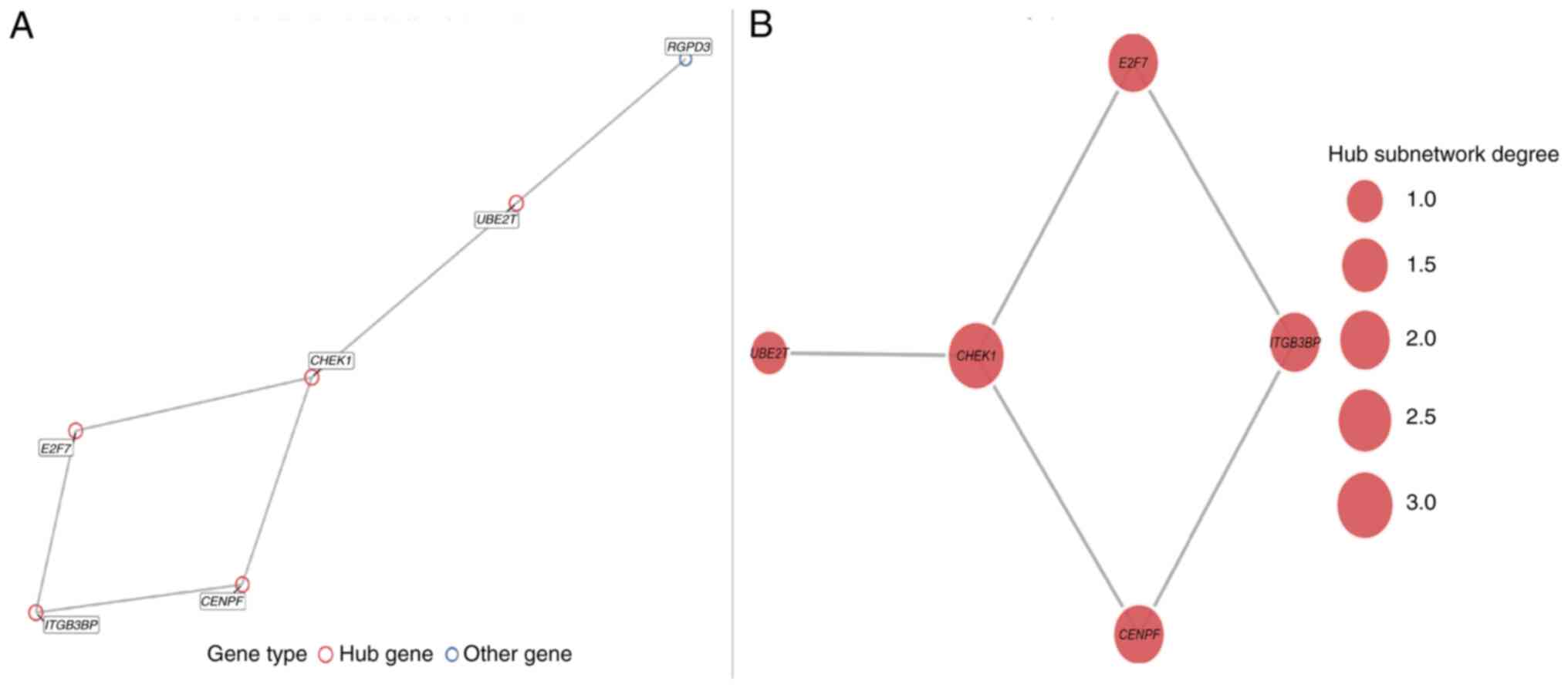

Among the six significantly upregulated DEGs, five

genes (CENPF, CHEK1, UBE2T, E2F7 and

ITGB3BP) formed a tightly interconnected hub module in the

PPI network constructed using the STRING database (Fig. 3A and B). The identification of these hub genes

reveals their functional involvement in cell cycle regulation and

DNA damage repair pathways. Furthermore, the convergence of their

upregulated expression and central network position highlights

their coordinated role in promoting genomic instability and

uncontrolled proliferation, which are key mechanisms underlying

HG-GEP NENs progression. Collectively, these findings support the

value of further investigating these hub genes as potential

therapeutic targets.

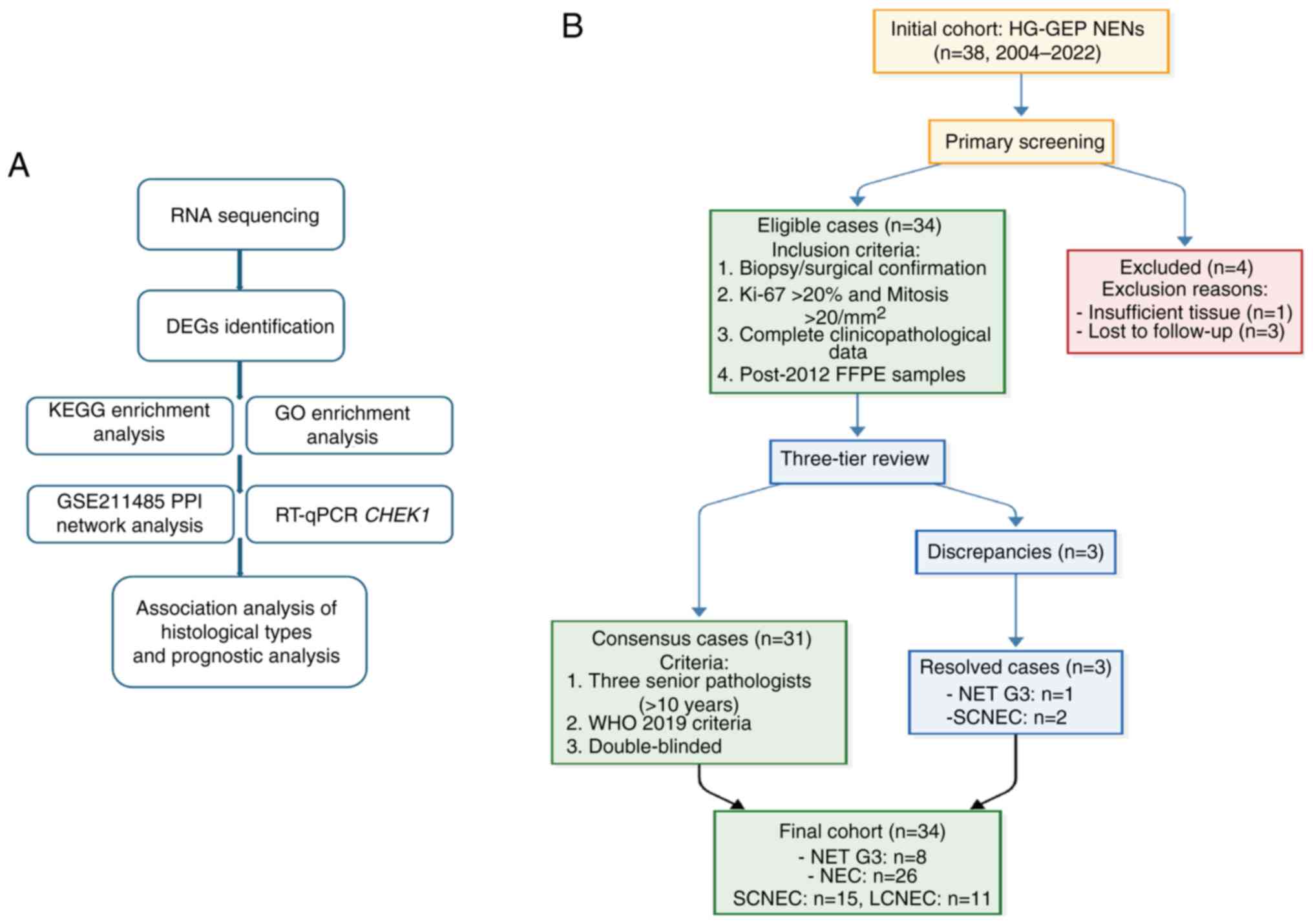

Analysis using TCGA database

Owing to the rarity of HG-GEP NENs, corresponding

tumour classifications were unavailable in TCGA. Therefore,

transcriptomic and clinical data from TCGA-COAD and TCGA-READ

projects were utilized as relevant proxies for digestive system

tumours. Survival analysis demonstrated that high expression of

CHEK1 was significantly associated with poorer overall

survival (Log-rank P<0.05; Fig.

4A-E). Concurrently, ROC curve analysis indicated that

CHEK1 expression possessed high diagnostic accuracy for

distinguishing tumour from normal tissues (AUC >0.85; Fig. 4F). CHEK1 was selected for

further analysis since it emerged as the most prognostically and

diagnostically significant gene among the five hub genes in these

validation analyses. Among these, CHEK1 was significantly

overexpressed in digestive system tumour tissues compared with that

in adjacent normal tissues based on TCGA-COAD and TCGA-READ

datasets (P<0.001, unpaired Student's t-test; Fig. 4G), suggesting that CHEK1 may

serve as a diagnostically and prognostically relevant target gene

in digestive system malignancies.

![Prognostic and diagnostic analysis of

the DEGs identified from the GSE211485 dataset. (A-E) Kaplan-Meier

survival curves showing the association between the expression

levels of the five identified DEGs (A) CHEK1, (B)

CENPF, (C) E2F7, (D) ITGB3BP and (E)

UBE2T, and overall survival in patients with digestive

system tumours. The HR and 95% CIs were calculated using the

log-rank test. (F) ROC curve showing the diagnostic performance of

CHEK1 expression for distinguishing tumour from normal

tissues. The AUC indicates diagnostic accuracy. (G) Expression of

CHEK1 [log2 (TPM +1)] in digestive system tumour tissues

compared with adjacent normal tissues. Statistical significance is

indicated as ***P<0.001. DEGs, differentially

expressed genes; CI, confidence interval; AUC, area under the

curve; HR, hazard ratio; CHEK1, checkpoint kinase 1; FPR,

false-positive rate; TPR, true-positive rate; TPM, transcripts per

million.](/article_images/etm/31/1/etm-31-01-13001-g03.jpg) | Figure 4Prognostic and diagnostic analysis of

the DEGs identified from the GSE211485 dataset. (A-E) Kaplan-Meier

survival curves showing the association between the expression

levels of the five identified DEGs (A) CHEK1, (B)

CENPF, (C) E2F7, (D) ITGB3BP and (E)

UBE2T, and overall survival in patients with digestive

system tumours. The HR and 95% CIs were calculated using the

log-rank test. (F) ROC curve showing the diagnostic performance of

CHEK1 expression for distinguishing tumour from normal

tissues. The AUC indicates diagnostic accuracy. (G) Expression of

CHEK1 [log2 (TPM +1)] in digestive system tumour tissues

compared with adjacent normal tissues. Statistical significance is

indicated as ***P<0.001. DEGs, differentially

expressed genes; CI, confidence interval; AUC, area under the

curve; HR, hazard ratio; CHEK1, checkpoint kinase 1; FPR,

false-positive rate; TPR, true-positive rate; TPM, transcripts per

million. |

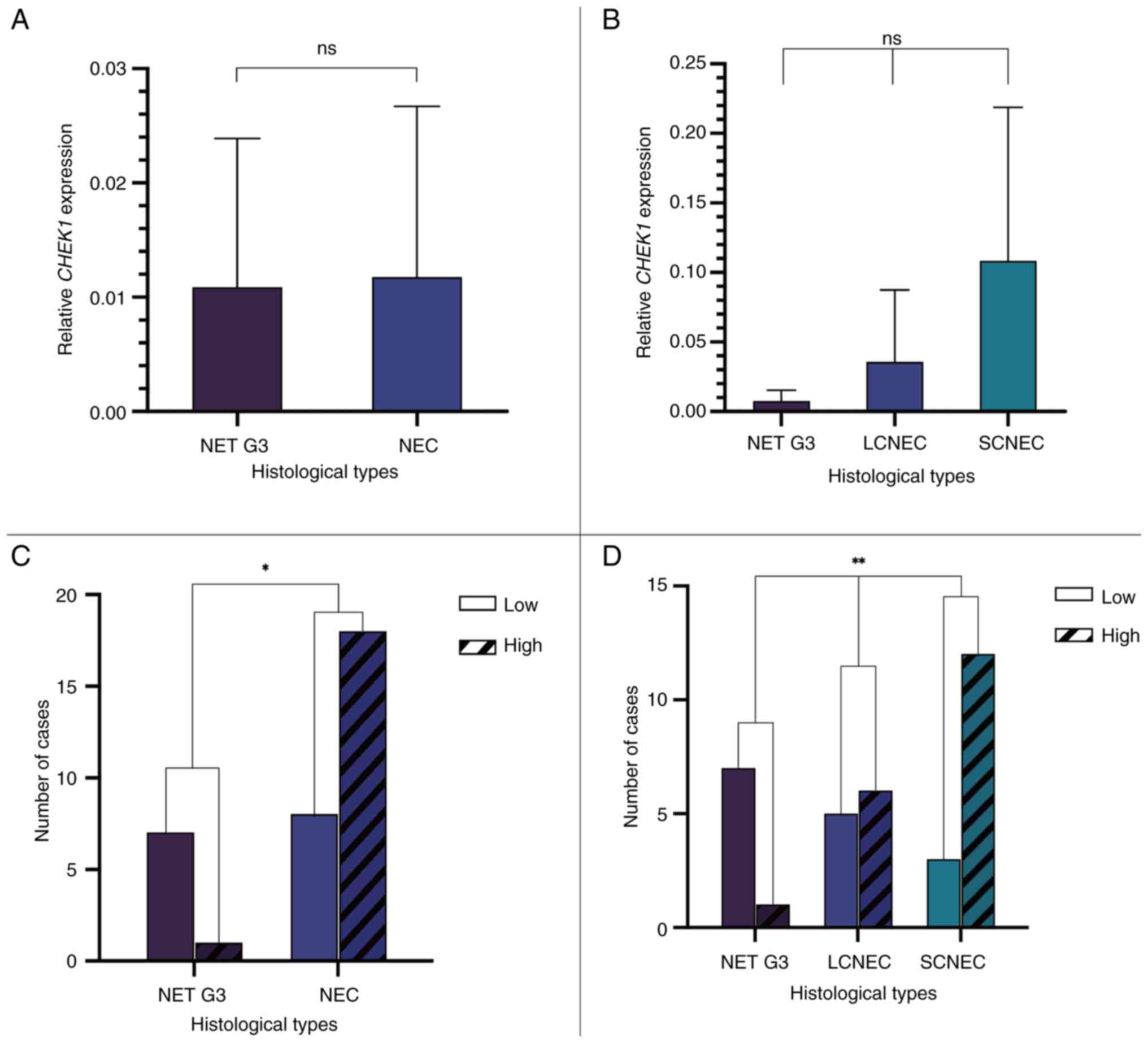

RT-qPCR detection of CHEK1 expression

in HG-GEP NENs

A total of 34 patients with HG-GEP NENs recruited in

the present study were included in the RT-qPCR analysis, excluding

3 patients with SCNEC and 1 patient with NET G3 diagnosed prior to

2012. Patients were classified into high- and low-CHEK1

expression groups based on the median expression level for

categorical analyses. RT-qPCR analysis revealed that CHEK1

expression was lower in the NET G3 group (n=8) compared with that

in the NEC group (n=26), although the difference was not

statistically significant (P=0.075; Fig. 5A). Further analysis among the NET

G3 (n=8), LCNEC (n=11) and SCNEC (n=15) subgroups revealed no

significant differences (P>0.05 for all pairwise comparisons;

Fig. 5B). Analysis between

histological subtypes indicated a significant difference between

the NET G3 and NEC groups (P=0.0113; Fig. 5C), with a higher proportion of

patients exhibiting high CHEK1 expression in the NEC group.

Further intergroup analysis demonstrated that the proportion of

patients exhibiting elevated CHEK1 expression was

significantly higher in the SCNEC subgroup compared with that in

the NET G3 and LCNEC groups (P=0.0075; Fig. 5D).

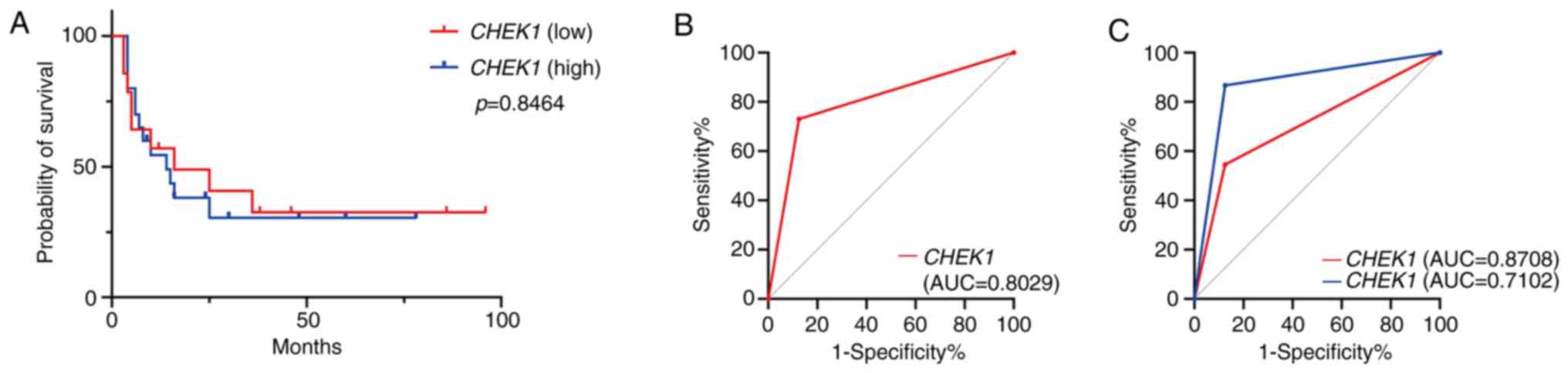

Prognostic and diagnostic analysis of

CHEK1 expression

The median survival time was 14 months in the

CHEK1 high-expression group and 16 months in the

low-expression group. The Kaplan-Meier survival analysis

demonstrated no significant difference in overall survival between

the high- and low-expression groups (P=0.8464, Fig. 6A). ROC curve analysis demonstrated

that high CHEK1 expression influenced the diagnostic

performance of NEC (AUC=0.8029; Fig.

6B). Further analysis, stratifying NEC cases into LCNEC and

SCNEC subtypes, revealed that high CHEK1 expression

contributed to the diagnosis of LCNEC and SCNEC, with a more

pronounced effect observed for SCNEC (AUC=0.8708) compared with

LCNEC (AUC=0.7102) (Fig. 6C and

Table III).

| Table IIIDiagnostic performance of

CHEK1 expression in high-grade gastroenteropancreatic

neuroendocrine neoplasms. |

Table III

Diagnostic performance of

CHEK1 expression in high-grade gastroenteropancreatic

neuroendocrine neoplasms.

| Pathological

category | AUC | Diagnostic

efficacy |

|---|

| NEC (overall) | 0.8029 | Moderate diagnostic

value |

| SCNEC | 0.8708 | Good diagnostic

value |

| LCNEC | 0.7102 | Limited diagnostic

value |

Discussion

The 2019 WHO Classification (5th Edition) introduced

revised diagnostic criteria for HG-GEP NENs (3,5),

defining them by a Ki-67 proliferation index of >20% and >20

mitoses per 2 mm². This revision underscores the dependence on

histopathological morphology for precisely distinguishing NET G3

from NEC, a process susceptible to interobserver variability. The

present study addresses this challenge by identifying a distinct

molecular signature in HG-GEP NENs, characterized by the

upregulation of cell cycle and DNA damage repair pathways.

Critically, significant overexpression of CHEK1 in NEC,

particularly the SCNEC subtype, was demonstrated. This finding

provides a molecular association for their aggressive clinical

behaviours, aligning with established literature that associates

NEC with poorer survival and platinum-based chemotherapy regimens,

in contrast to NET G3 (7,10,35,36).

Thus, the present findings not only validate the existing

pathological distinction but also provide a molecular pathological

basis for the divergent clinical phenotypes and treatment

responses, potentially informing future targeted therapeutic

strategies.

Macroscopically, NET G3 typically presents as solid

nodules with a protruding or polypoid appearance, moderate firmness

and grey-white or grey-yellow cut surface with well-defined borders

relative to the surrounding tissues. Conversely, NEC often exhibit

irregular ulcers or cauliflower-like protrusions, frequently

accompanied by haemorrhage or necrosis. NEC are fragile, prone to

fragmentation and are poorly demarcated from the adjacent tissues.

When located in the colorectal region, such tumours commonly

exhibit circumferential growth, leading to luminal narrowing and

obstruction. Microscopically, NET G3 resemble well-differentiated

NENs, characterised by organoid architectures or growth patterns

such as trabecular, ribbon-like or glandular arrangements.

Alternatively, NEC are defined by diffuse, sheet-like proliferation

with pronounced cellular atypia, poor differentiation and frequent

necrosis (3). In the present

study, tumour specimens were reclassified in accordance with the

latest WHO classification standards following a review by at least

three senior pathologists.

The differential expression of specific

immunohistochemical and molecular markers, such as somatostatin

receptor 2A (SSTR2A), p53, Rb (36,37)

and clusterin, may aid in distinguishing HG-GEP NENs (38). However, the identification of novel

molecular biomarkers remains essential for improving differential

diagnostic accuracy. This is particularly important given that, due

to the rarity of these neoplasms, most available data have been

obtained from patients with NEC, with NET G3 being even less

common. Furthermore, sequencing data within existing databases

remain limited.

In the present study, CHEK1 was identified as

a novel complementary diagnostic marker in accordance with the WHO

2019 criteria, demonstrating concordance with established

immunohistochemical markers (such as SSTR2A and p53) and

KRAS/BRAF mutational profiles (34). However, two critical limitations

warrant consideration. First, the transcriptomic dataset included

only two HG cases, thereby limiting the representativeness of the

sample. Second, due to the unavailability of HG-GEP NENs data in

TCGA, broader digestive system tumour datasets were utilised for

validation, which may have affected the specificity of the

findings.

Given the rarity of HG-GEP NENs and the limitations

of existing databases, several research priorities are proposed: i)

The establishment of multicentre collaborative networks to ensure

the inclusion of ≥20 cases per subtype (NET G3/LCNEC/SCNEC); ii)

the implementation of standardised diagnostic and research

protocols; and iii) the execution of integrated multi-omics

analyses on HG-GEP NEN samples. Furthermore, validation at the

protein level (such as through immunohistochemical analysis of

CHEK1 in HG-GEP NEN tissues) and functional assays using

HG-GEP NEN-derived cell lines will be essential to elucidate the

mechanistic role of CHEK1 in cell cycle dysregulation. These

comprehensive approaches will facilitate definitive validation of

the diagnostic utility of CHEK1 and deepen the understanding

of its biological function in these neoplasms, thereby contributing

to the development of more precise molecular classification

systems.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated the

diagnostic value of CHEK1, thereby providing valuable

insights and guidance for future clinical pathology research and

practice. The findings suggest that CHEK1 may serve as a

novel molecular biomarker for the differential diagnosis of HG-GEP

NENs. However, the small sample size represents a significant

limitation of the present study, potentially restricting the

immediate applicability of the findings to clinical practice. To

fully elucidate the underlying molecular pathogenic mechanisms of

the identified genes, further biological investigations are

required. Moreover, large-scale clinicopathological studies are

necessary before these findings can be translated into clinical

practice.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported by the Beijing Tongzhou

District Science and Technology Committee Project Fund (grant no.

KJ2024CX027).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

NL contributed to the study conceptualization, data

curation, formal data analysis, experimental investigation,

methodology development, validation of the results and writing of

the original draft. YH contributed to the study conceptualization,

project administration, funding acquisition, and reviewing and

editing of the manuscript. JA performed experimental investigations

and validated the experimental results. NL and YH confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors have read and

approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the

ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved

by the Institutional Review Board of Beijing Luhe Hospital, Capital

Medical University (approval no. 2024-LHKY-107-01). The requirement

for written informed consent was waived by the same ethics

committee due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Pavel M, Öberg K, Falconi M, Krenning EP,

Sundin A and Perren A: ESMO Guidelines Committee: Electronic

address: clinicalguidelines@esmo.org. Gastroenteropancreatic

neuroendocrine neoplasms: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for

diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 31:844–860.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Gribble FM and Reimann F: Function and

mechanisms of enteroendocrine cells and gut hormones in metabolism.

Nat Rev Endocrinol. 15:226–237. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Nagtegaal ID, Odze RD, Klimstra D, Paradis

V, Rugge M, Schirmacher P, Washington KM, Carneiro F and Cree IA:

WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. The 2019 WHO

classification of tumours of the digestive system. Histopathology.

76:182–188. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Busico A, Maisonneuve P, Prinzi N,

Pusceddu S, Centonze G, Garzone G, Pellegrinelli A, Giacomelli L,

Mangogna A, Paolino C, et al: Gastroenteropancreatic high-grade

neuroendocrine neoplasms: Histology and molecular analysis, two

sides of the same coin. Neuroendocrinology. 110:616–629.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Milione M, Maisonneuve P, Pellegrinelli A,

Grillo F, Albarello L, Spaggiari P, Vanoli A, Tagliabue G, Pisa E,

Messerini L, et al: Ki67 proliferative index of the neuroendocrine

component drives MANEC prognosis. Endocr Relat Cancer. 25:583–593.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Tang LH, Untch BR, Reidy DL, O'Reilly E,

Dhall D, Jih L, Basturk O, Allen PJ and Klimstra DS:

Well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumors with a morphologically

apparent high-grade component: A pathway distinct from poorly

differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas. Clin Cancer Res.

22:1011–1017. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Sorbye H, Kong G and Grozinsky-Glasberg S:

PRRT in high-grade gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms

(WHO G3). Endocr Relat Cancer. 27:R67–R77. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Pellat A and Coriat R: Well differentiated

grade 3 neuroendocrine tumors of the digestive tract: A narrative

review. J Clin Med. 9(1677)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Venizelos A, Elvebakken H, Perren A,

Nikolaienko O, Deng W, Lothe IMB, Couvelard A, Hjortland GO,

Sundlöv A, Svensson J, et al: The molecular characteristics of

high-grade gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms. Endocr

Relat Cancer. 29:1–14. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Scarpa A, Chang DK, Nones K, Corbo V,

Patch AM, Bailey P, Lawlor RT, Johns AL, Miller DK, Mafficini A, et

al: Whole-genome landscape of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours.

Nature. 543:65–71. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Mafficini A and Scarpa A: Genetics and

epigenetics of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms.

Endocr Relat Cancer. 26:R249–R266. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Jin XF, Spöttl G, Maurer J, Nölting S and

Auernhammer CJ: Antitumoral activity of the MEK inhibitor

trametinib (TMT212) alone and in combination with the CDK4/6

inhibitor ribociclib (LEE011) in neuroendocrine tumor cells in

vitro. Cancers (Basel). 13(1485)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Wang ZJ, An K, Li R, Shen W, Bao MD, Tao

JH, Chen JN, Mei SW, Shen HY, Ma YB, et al: Analysis of 72 patients

with colorectal high-grade neuroendocrine neoplasms from three

chinese hospitals. World J Gastroenterol. 25:5197–5209.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Uccella S, La Rosa S, Metovic J, Marchiori

D, Scoazec JY, Volante M, Mete O and Papotti M: Genomics of

high-grade neuroendocrine neoplasms: Well-differentiated

neuroendocrine tumor with high-grade features (G3 NET) and

neuroendocrine carcinomas (NEC) of various anatomic sites. Endocr

Pathol. 32:192–210. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Mitsuhashi K, Yamamoto I, Kurihara H,

Kanno S, Ito M, Igarashi H, Ishigami K, Sukawa Y, Tachibana M,

Takahashi H, et al: Analysis of the molecular features of rectal

carcinoid tumors to identify new biomarkers that predict biological

malignancy. Oncotarget. 6:22114–22125. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Park HY, Kwon MJ, Kang HS, Kim YJ, Kim NY,

Kim MJ, Min KW, Choi KC, Nam ES, Cho SJ, et al: Targeted

next-generation sequencing of well-differentiated rectal, gastric,

and appendiceal neuroendocrine tumors to identify potential

targets. Hum Pathol. 87:83–94. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Hijioka S, Hosoda W, Matsuo K, Ueno M,

Furukawa M, Yoshitomi H, Kobayashi N, Ikeda M, Ito T, Nakamori S,

et al: Rb loss and KRAS mutation are predictors of the response to

platinum-based chemotherapy in pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasm

with grade 3: A japanese multicenter pancreatic NEN-G3 study. Clin

Cancer Res. 23:4625–4632. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Sorbye H, Baudin E and Perren A: The

problem of high-grade gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine

neoplasms. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 47:683–698.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Patil M, Pabla N and Dong Z: Checkpoint

kinase 1 in DNA damage response and cell cycle regulation. Cell Mol

Life Sci. 70:4009–4021. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Qiu Z, Oleinick NL and Zhang J: ATR/CHK1

inhibitors and cancer therapy. Radiother Oncol. 126:450–464.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Hubackova S, Davidova E, Boukalova S,

Kovarova J, Bajzikova M, Coelho A, Terp MG, Ditzel HJ, Rohlena J

and Neuzil J: Replication and ribosomal stress induced by targeting

pyrimidine synthesis and cellular checkpoints suppress

p53-deficient tumors. Cell Death Dis. 11(110)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Jaaks P, Coker EA, Vis DJ, Edwards O,

Carpenter EF, Leto SM, Dwane L, Sassi F, Lightfoot H, Barthorpe S,

et al: Effective drug combinations in breast colon and pancreatic

cancer cells. Nature. 603:166–173. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Pang YY, Chen ZY, Zeng DT, Li DM, Li Q,

Huang WY, Li B, Luo JY, Chi BT, Huang Q, et al: Checkpoint kinase 1

in colorectal cancer: Upregulation of expression and promotion of

cell proliferation. World J Clin Oncol. 16(101725)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Gu C, Wang W, Tang X, Xu T, Zhang Y, Guo

M, Wei R, Wang Y, Jurczyszyn A, Janz S, et al: CHEK1 and

circCHEK1_246aa evoke chromosomal instability and induce bone

lesion formation in multiple myeloma. Mol Cancer.

20(84)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Sun J, Zhu Z, Li W, Shen M, Cao C, Sun Q,

Guo Z, Liu L and Wu D: UBE2T-regulated H2AX monoubiquitination

induces hepatocellular carcinoma radioresistance by facilitating

CHK1 activation. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 39(222)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Zuo W, Zhang W, Xu F, Zhou J and Bai W:

Long non-coding RNA LINC00485 acts as a microRNA-195 sponge to

regulate the chemotherapy sensitivity of lung adenocarcinoma cells

to cisplatin by regulating CHEK1. Cancer Cell Int.

19(240)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Sen T, Tong P, Stewart CA, Cristea S,

Valliani A, Shames DS, Redwood AB, Fan YH, Li L, Glisson BS, et al:

CHK1 inhibition in small-cell lung cancer produces single-agent

activity in biomarker-defined disease subsets and combination

activity with cisplatin or olaparib. Cancer Res. 77:3870–3884.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Booth L, Roberts J, Poklepovic A and Dent

P: The CHK1 inhibitor SRA737 synergizes with PARP1 inhibitors to

kill carcinoma cells. Cancer Biol Ther. 19:786–796. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Cui Q, Cai CY, Wang JQ, Zhang S, Gupta P,

Ji N, Yang Y, Dong X, Yang DH and Chen ZS: Chk1 inhibitor MK-8776

restores the sensitivity of chemotherapeutics in P-glycoprotein

overexpressing cancer cells. Int J Mol Sci. 20(4095)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Landau HJ, McNeely SC, Nair JS, Comenzo

RL, Asai T, Friedman H, Jhanwar SC, Nimer SD and Schwartz GK: The

checkpoint kinase inhibitor AZD7762 potentiates

chemotherapy-induced apoptosis of p53-mutated multiple myeloma

cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 11:1781–1788. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Dai Y, Rahmani M, Pei XY, Khanna P, Han

SI, Mitchell C, Dent P and Grant S: Farnesyltransferase inhibitors

interact synergistically with the Chk1 inhibitor UCN-01 to induce

apoptosis in human leukemia cells through interruption of both Akt

and MEK/ERK pathways and activation of SEK1/JNK. Blood.

105:1706–1716. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Soldevilla B, Lens-Pardo A,

Espinosa-Olarte P, Carretero-Puche C, Molina-Pinelo S, Robles C,

Benavent M, Gomez-Izquierdo L, Fierro-Fernández M, Morales-Burgo P,

et al: MicroRNA signature and integrative omics analyses define

prognostic clusters and key pathways driving prognosis in patients

with neuroendocrine neoplasms. Mol Oncol. 17:582–597.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Li N, Hu Y, Wu L and An J:

Clinicopathological correlations in 38 cases of

gastroenteropancreatic high-grade neuroendocrine neoplasms. Front

Oncol. 14(1399079)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Rosery V, Reis H, Savvatakis K, Kowall B,

Stuschke M, Paul A, Dechêne A, Yang J, Zhao B, Borgers A, et al:

Antitumor immune response is associated with favorable survival in

GEP-NEN G3. Endocr Relat Cancer. 28:683–693. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Konukiewitz B, Schlitter AM, Jesinghaus M,

Pfister D, Steiger K, Segler A, Agaimy A, Sipos B, Zamboni G,

Weichert W, et al: Somatostatin receptor expression related to TP53

and RB1 alterations in pancreatic and extrapancreatic

neuroendocrine neoplasms with a Ki67-index above 20. Mod Pathol.

30:587–598. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Bellizzi AM: Immunohistochemistry in the

diagnosis and classification of neuroendocrine neoplasms: What can

brown do for you? Hum Pathol. 96:8–33. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Czeczok TW, Stashek KM, Maxwell JE,

O'Dorisio TM, Howe JR, Hornick JL and Bellizzi AM: Clusterin in

neuroendocrine epithelial neoplasms: Absence of expression in a

well-differentiated tumor suggests a jejunoileal origin. Appl

Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 26:94–100. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

![Overall analysis of the DEGs. (A)

Volcano plot of the DEGs. Red and blue dots represent significantly

upregulated and downregulated genes, respectively (adjusted P-value

<0.05 and |log2FC|>1). (B) GO and KEGG enrichment

analysis of the DEGs. Bar plots show the top significantly enriched

terms. The x-axis represents the enrichment significance

[-Log10(adjusted P-value)], and numbers in parentheses

indicate gene counts for each term. DEGs, differentially expressed

genes; BP, biological processes; CC, cellular component; MF,

molecular function; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and

Genomes.](/article_images/etm/31/1/etm-31-01-13001-g01.jpg)

![Prognostic and diagnostic analysis of

the DEGs identified from the GSE211485 dataset. (A-E) Kaplan-Meier

survival curves showing the association between the expression

levels of the five identified DEGs (A) CHEK1, (B)

CENPF, (C) E2F7, (D) ITGB3BP and (E)

UBE2T, and overall survival in patients with digestive

system tumours. The HR and 95% CIs were calculated using the

log-rank test. (F) ROC curve showing the diagnostic performance of

CHEK1 expression for distinguishing tumour from normal

tissues. The AUC indicates diagnostic accuracy. (G) Expression of

CHEK1 [log2 (TPM +1)] in digestive system tumour tissues

compared with adjacent normal tissues. Statistical significance is

indicated as ***P<0.001. DEGs, differentially

expressed genes; CI, confidence interval; AUC, area under the

curve; HR, hazard ratio; CHEK1, checkpoint kinase 1; FPR,

false-positive rate; TPR, true-positive rate; TPM, transcripts per

million.](/article_images/etm/31/1/etm-31-01-13001-g03.jpg)