Introduction

Chronic subdural hematomas (CSDHs) are neurological

events characterized by the gradual accumulation of blood and its

breakdown products in the subdural space between the dura mater and

the cerebral cortex. CSDHs are most commonly associated with minor

head trauma, which can rupture the bridging veins spanning the

subdural space that then drain into the dural venous sinuses

(1). CSDHs primarily affect the

elderly population and have become one of the most frequently

encountered neurosurgical disorders in clinical settings. Recent

epidemiological data indicate that the annual incidence of CSDH

ranges from 1 to 13.5 per 100,000 individuals in the general

population, with a marked increase observed with advancing age. In

individuals aged 65 years and older, the incidence rises to ~58.1

per 100,000 individuals per year (2). The incidence of CSDHs has steadily

increased over recent decades; for example, a temporal analysis

conducted in Finland from 1990 to 2015 reported a doubling in

annual incidence, from 8.2 to 17.6 per 100,000 individuals per

year, likely driven by population aging and the widespread use of

antithrombotic agents (3). These

epidemiological trends highlight the growing clinical burden of

CSDHs and the need for improved therapeutic strategies.

The pathophysiology of a CSDH is multifactorial,

involving a complex interplay of biological processes, among which

inflammation has a central role. Following the initial hemorrhagic

event, a persistent inflammatory cascade is triggered, which

facilitates immune cell infiltration, activation of the

fibrinolytic system and the formation of a vascularized outer

membrane encasing the hematoma. The neovasculature within this

membrane is typically immature and highly permeable, resulting in

recurrent microbleeding and the extravasation of plasma components.

This self-perpetuating cycle, often referred to as the ‘CSDH

cycle’, drives progressive hematoma expansion over time (2,3).

Considering the key roles of inflammation and

aberrant angiogenesis in CSDH progression, recent pharmacological

efforts have increasingly focused on targeting these pathways using

established anti-inflammatory and anti-angiogenic therapies

(4,5). Atorvastatin, a widely prescribed

3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase inhibitor primarily used

to treat hyperlipidemia and atherosclerosis, has demonstrated a

variety of biological effects beyond lipid-lowering (6). Notably, the anti-inflammatory and

angiogenesis-modulating properties of atorvastatin render it a

promising candidate for the management of CSDHs (7,8).

Preliminary clinical investigations have indicated that

atorvastatin may facilitate hematoma resolution and improve

neurological outcomes in patients with CSDHs (9-11).

These observations are further supported by animal studies showing

similar therapeutic benefits (12,13);

however, the precise molecular mechanisms by which atorvastatin

mediates its effects on CSDHs have not yet been fully

elucidated.

Network pharmacology offers an integrative framework

for investigating the complex pharmacodynamic profiles of

therapeutic agents by identifying their interactions with a number

of molecular targets (14). This

approach, which integrates computational modeling with systems

biology, enables the construction of comprehensive drug-target

networks and facilitates the discovery of novel mechanisms of

action as well as drug repurposing opportunities. In the present

study, network pharmacology analysis was combined with experimental

in vitro validation to investigate the potential molecular

mechanisms by which atorvastatin exerts therapeutic effects in the

treatment of CSDHs. Specifically, this study aimed to identify the

key molecular targets and signaling pathways through which

atorvastatin modulates inflammation in CSDHs, and to provide

mechanistic insights supporting its potential as a therapeutic

agent for this condition.

Materials and methods

Prediction of the therapeutic targets

of atorvastatin in CSDHs

Potential molecular targets of atorvastatin in CSDHs

were systematically retrieved from the ChEMBL (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/chembl/), NCBI PubChem Compound

(https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pccompound) and

SwissTargetPrediction (http://www.swisstargetprediction.ch/) databases using

the keyword ‘atorvastatin’. All identified targets were

standardized to the official gene symbols via the UniProt database

(https://www.uniprot.org/) and duplicate entries

were removed to generate a non-redundant gene list. Concurrently,

CSDH-related genes were obtained from the GeneCards database

(https://www.genecards.org/) using the

keyword ‘CSDH’ and from the DisGeNET database (https://www.disgenet.org/) using the term ‘subdural

hematoma’ and duplicates were similarly excluded to ensure

uniqueness. The intersection of the atorvastatin-associated and

CSDH-associated genes was determined using Venny 2.1 (https://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny/), and the

overlapping genes were defined as the putative therapeutic targets

of atorvastatin in CSDHs.

Enrichment analysis

Enrichment analysis of the identified target genes

was performed using R software (version 4.2.1; RStudio, Inc.). The

gene identifiers were converted to Entrez IDs using the

‘org.Hs.eg.db’ package (15). Gene

Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG)

pathway analyses were conducted using the ‘clusterProfiler,’

(16) ‘enrichplot,’ (17) ‘org.Hs.eg.db’ and ‘pathview’

(18) packages. P<0.05 and

Q<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference. Visualization of the enrichment results was performed

using the ‘ggplot2’ (19)

package.

Protein-protein interaction (PPI)

network construction

To investigate the functional interactions among the

candidate target proteins, a PPI network was constructed using the

STRING database (https://string-db.org/). The resulting network was

subsequently visualized using Cytoscape software (version 3.9.1;

Cytoscape Consortium) (20).

Molecular docking analysis

The 2D chemical structure of atorvastatin was

retrieved from the ChEMBL database (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/chembl/), whereas the 3D

structures of the target proteins were obtained from the RCSB

Protein Data Bank (https://www.rcsb.org/; accession numbers: 8QY5, 6WZM,

8H78, 6ESM and 4G8O). Molecular docking simulations were conducted

using AutoDockTools (version 1.5.7; Molecular Graphics Laboratory;

The Scripps Research Institute). The ligand-receptor binding

conformations and interactions were visualized using PyMOL software

(version 2.5.4; Schrödinger, Inc.).

Cell culture

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs; cat.

no. QS-H002; Keycell Biotechnology Co., Ltd.), authenticated via

short tandem repeat profiling by the manufacturer, were purchased

at passage 3 and cultured in endothelial cell-specific medium (cat.

no. QS-H002A; Keycell Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) supplemented with

10% fetal bovine serum (HyClone™; Cytiva). The cells were

maintained in a humidified incubator at 37˚C with 5% CO2

and all experiments were performed using cells between passages 5

and 8.

Induction of inflammation and

atorvastatin treatment

HUVECs were seeded into 6-well culture plates at a

density of 5x105 cells per well. The cells were treated

with 10 µg/l tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α; cat. no. 300-01A-10UG;

PeproTech Inc.; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at 37˚C for 24 h to

induce inflammation. To assess the effects of atorvastatin

dose-dependently, cells were assigned to five groups: Control group

(untreated), inflammation group (TNF-α treated only) and three

intervention groups co-treated with TNF-α and 2.5, 10.0 or 20.0

µmol/l atorvastatin (cat. no. S5715: Selleck Chemicals) at 37˚C for

24 h; both agents were added to the culture medium at the same time

to evaluate the direct protective effect of atorvastatin against

TNF-α-induced inflammation. Based on the results of the

dose-response experiments and previous studies (21,22),

10 µmol/l was selected to investigate the effect of atorvastatin on

the expression of inflammation-related genes in endothelial cell

models.

Quantification of inflammatory

cytokine levels by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

After 24 h of treatment, cell culture supernatants

were collected and centrifuged at 560 x g for 5 min at 4˚C. The

concentrations of interleukin (IL)-6, C-X-C motif chemokine ligand

8 (CXCL-8)/IL-8, intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) and

vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1) were measured using

ELISA kits (IL-6, cat. no. EH0201; CXCL-8, cat. no. EH0205; ICAM-1,

cat. no. EH0161; VCAM-1, cat. no. EH0326; Wuhan Fine Biotech Co.,

Ltd), in accordance with the manufacturers' instructions.

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from the HUVECs in each

group after 24 h of treatment using TRIzol™ reagent (cat. no.

15596-026; Ambion; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), then RT was

performed with the HiScript® II Q Select RT SuperMix kit (cat. no.

R233; Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd.) under the following conditions:

50˚C for 15 min, 85˚C for 5 sec and 4˚C for 10 min. qPCR was

conducted using the AceQ qPCR SYBR Green Master Mix (cat. no. Q111;

Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd.) on a ViiA™ 7 Real-Time PCR System

(Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The qPCR

cycling conditions were: 95˚C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of

95˚C for 10 sec and 60˚C for 60 sec. A melting curve was obtained

by 95˚C for 15 sec, 60˚C for 60 sec, and a gradual increase to 95˚C

with continuous fluorescence acquisition to verify amplification

specificity. Data were analyzed using QuantStudio™ Real-Time PCR

software (v1.6.1; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). All primers were

synthesized by Beijing Tsingke Biotech Co., Ltd. (Table I). Gene expression was normalized

to GAPDH and the relative changes in gene expression were

quantified using the 2-ΔΔCq method (23).

| Table IPrimers used for reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR. |

Table I

Primers used for reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR.

| Gene | Forward sequence

(5' to 3') | Reverse sequence

(5' to 3') | Size, bp |

|---|

| MMP-2 |

GTGTGAAGTATGGGAACGCC |

CCTGGAAGCGGAATGGAAAC | 231 |

| MMP-9 |

GCTACCACCTCGAACTTTGAC |

TCAGTGAAGCGGTACATAGGG | 161 |

| SERPINE-1 |

TGCCCTCACCAACATTCT |

TGCCACTCTCGTTCACCT | 54 |

| GAPDH |

TCAAGAAGGTGGTGAAGCAGG |

TCAAAGGTGGAGGAGTGGGT | 115 |

FITC-dextran permeability assay for

detecting endothelial cell barrier function

HUVECs were seeded into the upper chambers of

Transwell inserts (0.4 µm microporous PET membrane; BD Biosciences)

at a density of 5x104 cells per well. The cells were

cultured for 3-5 days until confluency was achieved, and a

continuous monolayer was formed. The same experimental grouping and

treatments as aforementioned were applied. After 24 h of

intervention, the medium in the upper chamber was removed and

replaced with 200 µl serum-free medium (cat. no. QS-H002A; Keycell

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) containing 1 g/l FITC-dextran (10 kDa;

cat. no. HY-128868; MedChemExpress). Simultaneously, 800 µl

serum-free medium was added to the lower chamber. The plates were

then incubated at 37˚C with 5% CO2 for 3 h. Following

incubation, 100 µl of the medium was collected from the lower

chamber and transferred to a 96-well plate for fluorescence

measurement. As a reference, 100 µl of the initial FITC-dextran

solution was used to determine the fluorescence intensity of the

upper chamber. The permeability rate (%) was calculated as follows:

(Fluorescence intensity of the lower chamber/initial fluorescence

intensity of the upper chamber) x100.

Matrigel tube formation assay

To evaluate the effect of atorvastatin on the

angiogenesis of endothelial cell models, a Matrigel tube formation

assay was performed. Experimental procedures were conducted as

previously described (24).

Briefly, HUVECs (5x105 cells/well) were seeded on

Matrigel, which had been thawed overnight at 4˚C and used to

precoat the culture plates at 37˚C for 1 h before cell seeding, and

were treated as aforementioned. Tube formation was visualized and

images were collected under an inverted light microscope (IX51;

Olympus Corporation).

Statistical analysis

The data are presented as the mean ± standard

deviation. Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS 25.0

software (IBM Corp.). Data were first assessed for normality and

homogeneity of variances using the Shapiro-Wilk test and Levene's

test, respectively. Then, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was

employed to compare the differences among groups, followed by the

least significant difference or Tukey's honestly significant

difference post hoc test for pairwise comparisons. The overall

P-values from ANOVA are reported in the text, whereas the

significance levels from pairwise comparisons are indicated in the

figures. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

Potential targets of atorvastatin in

the treatment of CSDHs

An initial list of 324 potential molecular targets

of atorvastatin was obtained without applying a specific confidence

score threshold, retaining only those with annotated gene symbols

and functional annotations. After standardization and

deduplication, 271 unique targets were retained. To identify the

genes associated with CSDHs, 125 genes were retrieved from

databases, resulting in 121 non-redundant CSDH-related genes.

Cross-referencing these genes with the atorvastatin targets

identified 19 overlapping genes through strict symbol matching via

Venny, which were defined as the candidate therapeutic targets of

atorvastatin in the context of CSDHs (Table II).

| Table IIPotential target genes of

atorvastatin in the treatment of chronic subdural hematoma. |

Table II

Potential target genes of

atorvastatin in the treatment of chronic subdural hematoma.

| Gene symbol | Gene name |

|---|

| MMP-9 | Matrix

metalloproteinase 9 |

| SERPINE-1 | Serpin family e

member 1 |

| MMP-2 | Matrix

metalloproteinase 2 |

| FGF-2 | Fibroblast growth

factor 2 |

| CXCL-10 | C-X-C motif

chemokine 10 |

| PLAT | Tissue-type

plasminogen activator |

| AKT-1 | AKT

serine/threonine kinase 1 |

| ANGPT-2 | Angiopoietin 2 |

| CCL-2 | C-C motif chemokine

ligand 2 |

| CD-36 | CD36 molecule |

| CRP | C-reactive

protein |

| CXCL-8/IL-8 | C-X-C motif

chemokine ligand 8/Interleukin 8 |

| EDN-1 | Endothelin 1 |

| F2 | Coagulation factor

II |

| F5 | Coagulation factor

V |

| IL-6 | Interleukin 6 |

| INS | Insulin |

| VWF | Von Willebrand

factor |

| F7 | Coagulation factor

VII |

Target gene enrichment analysis in the

treatment of CSDHs with atorvastatin

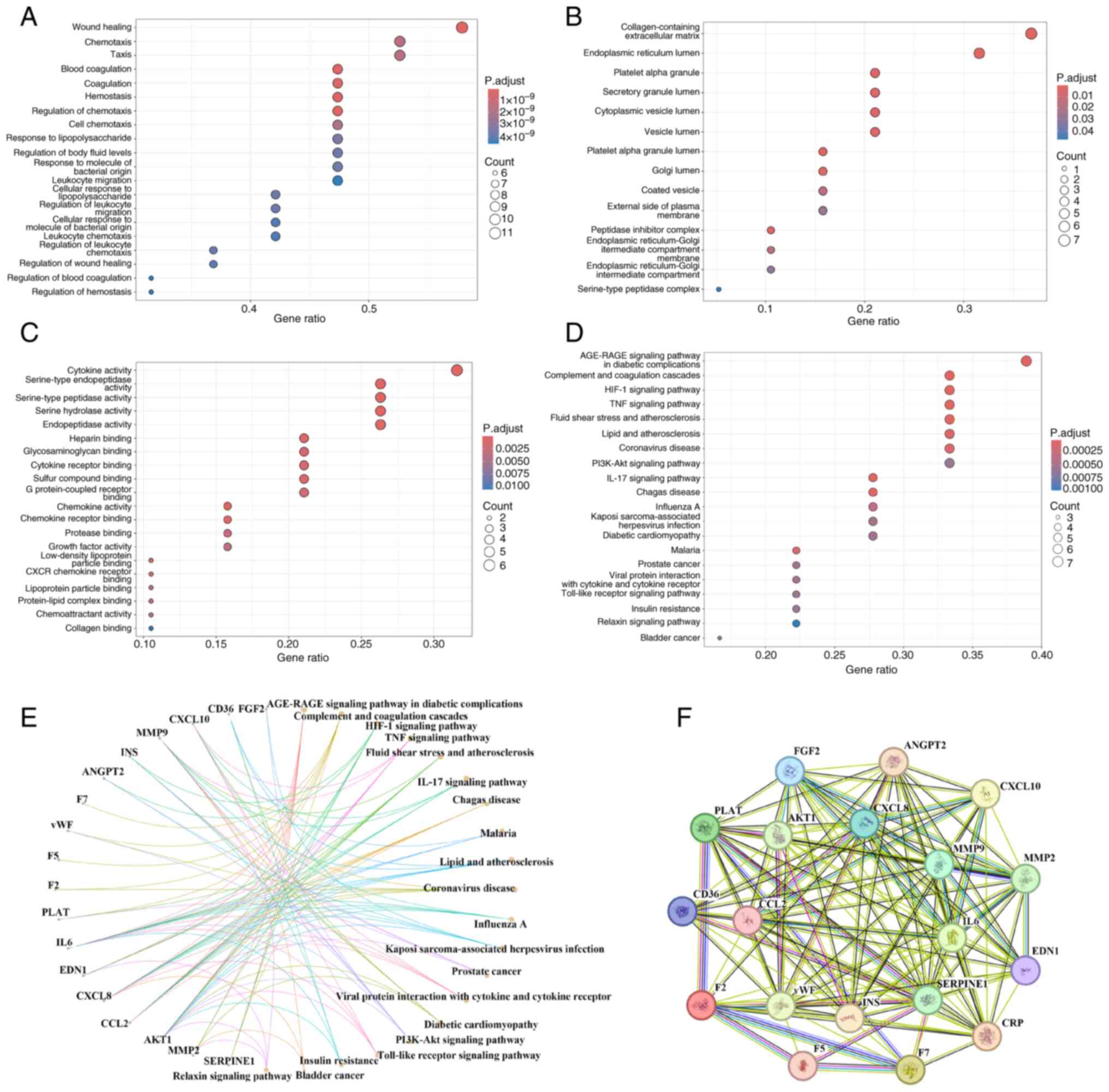

GO enrichment analysis of the 19 candidate genes

yielded 948 enriched terms, comprising 897 biological processes

(BPs), 15 cellular components (CCs) and 36 molecular functions

(MFs). The top 20 terms in each category are presented in Fig. 1A-C. These results suggest that

atorvastatin may exert therapeutic effects in CSDH management by

modulating BPs such as ‘Wound healing’, ‘Coagulation’,

‘Chemotaxis’, ‘Hemostasis’ and ‘Leukocyte migration’. The enriched

MFs included ‘Cytokine receptor binding’, ‘Cytokine activity’ and

‘Serine hydrolase activity’. The associated CCs included

‘Collagen-containing extracellular matrix’, ‘Peptidase inhibitor

complex’, ‘Secretory granule lumen’ and ‘cytoplasmic vesicle

lumen’.

KEGG pathway enrichment analysis revealed 62

pathways associated with the putative targets of atorvastatin in

treating CSDHs, with the top 20 pathways shown in Fig. 1D and E. These pathways are primarily involved

in the regulation of inflammation, coagulation and angiogenesis,

including the ‘HIF-1 signaling pathway’, ‘TNF signaling pathway’,

‘Complement and coagulation cascades’, ‘Toll-like receptor

signaling pathway’, ‘PI3K-Akt signaling pathway’ and ‘IL-17

signaling pathway’.

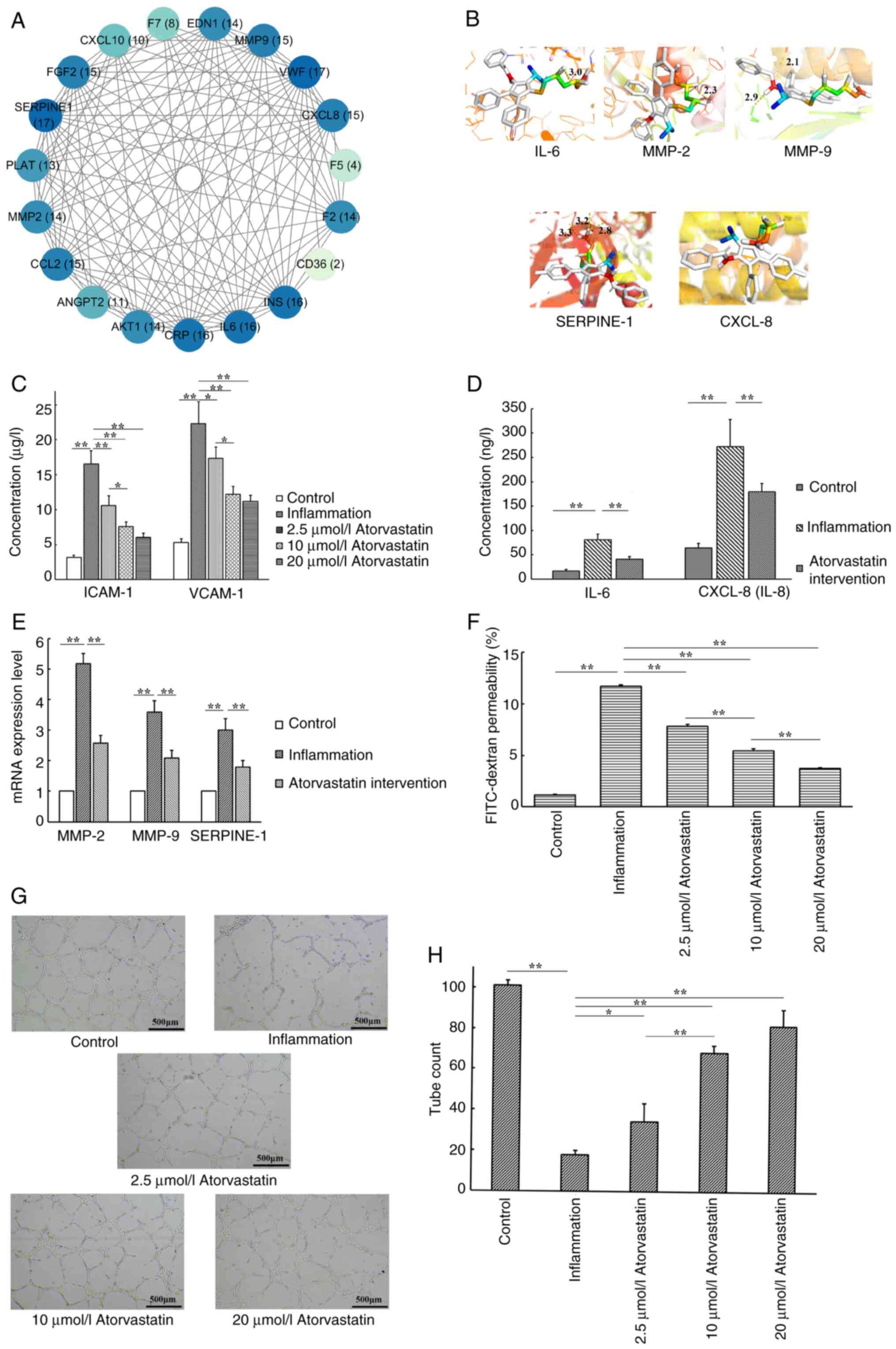

PPI network analysis

A PPI network was constructed using the STRING

database (Fig. 1F). Node degree

centrality was assessed to identify the highly connected hub genes

(Fig. 2A), with darker colors

representing nodes of higher degree (greater connectivity). Based

on both the topological importance and functional relevance, five

core targets [matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2, MMP-9, IL-6,

CXCL-8/IL-8 and serpin family E member 1 (SERPINE-1)] were selected

for further validation through molecular docking and in

vitro experiments. Other network metrics such as betweenness

and closeness centrality were also calculated, although they were

not used as primary selection criteria. These parameters reflect

the extent to which a node acts as a bridge or is close to other

nodes in the network, respectively, and were included to provide a

more comprehensive topological characterization. However, node

degree centrality was prioritized since it more directly represents

the number of connections a protein has, which is commonly regarded

as a reliable indicator of functional importance in biological

networks.

Molecular docking

Results of the molecular docking simulations

indicated that atorvastatin had strong binding affinities with all

five core target proteins, with binding energies ≤-5.0 kcal/mol.

This threshold value indicates strong ligand-receptor interactions

(25), with binding energies

<-7.0 kcal/mol suggesting a particularly high affinity (26). Furthermore, compared with the

binding energies of these target proteins with other known ligands

(27-31),

atorvastatin also exhibited a moderate to strong binding affinity

(Table III). Visualization of

the molecular docking results (Fig.

2B) revealed stable binding conformations characterized by key

hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions (Table SI). These results provide

mechanistic insights into the potential modulation of these targets

by atorvastatin.

| Table IIIBinding energies of potential target

gene proteins with atorvastatin and other known ligands. |

Table III

Binding energies of potential target

gene proteins with atorvastatin and other known ligands.

| Target | Binding energy with

Atorvastatin, kcal/mol | Binding energy with

other ligands, kcal/mol |

|---|

| IL-6 | -8.1 | -5.9-5.8 |

| MMP-2 | -6.0 | -8.2-5.7 |

| MMP-9 | -8.0 | -8.1-5.9 |

| SERPINE-1 | -6.7 | -8.2-5.3 |

| CXCL-8/IL-8 | -6.1 | -8.7-4.4 |

Atorvastatin reduces the inflammatory

response in an endothelial cell inflammation model

As shown in Fig.

2C, stimulation with TNF-α significantly increased the

secretion of the inflammatory biomarkers, ICAM-1 and VCAM-1, in the

HUVEC culture supernatants compared with the control group.

Treatment with atorvastatin at 2.5, 10.0 and 20.0 µmol/l

significantly reduced the ICAM-1 (F=60.544; P<0.001) and VCAM-1

(F=41.848; P<0.001) levels in a dose-dependent manner, compared

with the inflammation group. However, no statistically significant

difference was observed between the 10 and 20 µmol/l atorvastatin

treatment groups (P>0.05).

Inhibitory effects of atorvastatin on

TNF-α-induced inflammatory cytokine secretion and gene

expression

As shown in Fig. 2D

and E, TNF-α significantly

increased the secretion of IL-6 and CXCL-8 in the HUVEC culture

supernatants and significantly upregulated the mRNA expression of

MMP-2, MMP-9 and SERPINE-1 in HUVECs. Treatment with 10 µmol/l

atorvastatin significantly reduced the TNF-α-induced IL-6

(F=64.526; P<0.001) and CXCL-8 (F=37.779; P<0.001) secretion

levels and significantly downregulated the mRNA expression of MMP-2

(F=264.413; P<0.001), MMP-9 (F=86.675; P<0.001) and SERPINE-1

(F=71.180; P<0.001).

Atorvastatin attenuates

inflammation-induced endothelial barrier dysfunction

As shown in Fig.

2F, TNF-α stimulation markedly impaired the integrity of the

endothelial barrier, resulting in a significant increase in

FITC-dextran permeability from 1.14±0.08% in the control group to

11.68±0.13% in the inflammation group. Atorvastatin treatment

effectively restored barrier function in a dose-dependent manner,

reducing permeability to 7.83±0.17, 5.44±0.20 and 3.71±0.06% at

2.5, 10.0 and 20.0 µmol/l, respectively (F=2490.788; P<0.001).

These results further support the hypothesis that atorvastatin has

a protective effect on endothelial barrier integrity under

inflammatory conditions.

Atorvastatin protects endothelial

angiogenesis from inflammation-induced inhibition

As shown in Fig. 2G

and H, TNF-α stimulation

significantly impaired tube formation in HUVECs compared with the

control group. Co-treatment with atorvastatin at 2.5, 10.0 and 20.0

µmol/l significantly preserved angiogenic capacity in a

dose-dependent manner, attenuating the inflammation-induced

inhibition (F=99.859; P<0.001). However, no statistically

significant difference was observed between the 10 and 20 µmol/l

atorvastatin treatment groups (P>0.05).

Discussion

The pathophysiological mechanisms underlying the

onset and progression of CSDHs have been increasingly clarified in

recent decades. It is now accepted that the initial hemorrhage

originates from ruptured bridging veins, often triggered by minor

head trauma (particularly in elderly individuals with cerebral

atrophy) or by low intracranial pressure and neurosurgical

interventions (2,32). In the early phase following

hemorrhage, inflammatory cells (including neutrophils, lymphocytes,

macrophages and eosinophils) are recruited to the subdural space to

initiate tissue repair (2,3). However, these immune cells also

release inflammatory mediators and pro-angiogenic factors that

contribute to the formation of the hematoma capsule and to the

development of the neovascularization within it. The resulting

vasculature is typically immature and highly permeable, allowing

plasma leakage into the hematoma cavity and sustaining a cycle of

inflammation and hematoma enlargement, a process often referred to

as the ‘CSDH cycle’ (2,3). In addition to inflammation and

angiogenesis, the dysregulation of coagulation and fibrinolysis is

also involved in the pathogenesis of CSDHs. Enhanced fibrinolytic

activity may lead to persistent microhemorrhage and progressive

hematoma enlargement (33,34). Accordingly, fibrinolytic biomarkers

such as tissue-type plasminogen activator (tPA) have been proposed

as potential predictors of CSDH recurrence (35).

In the present study, the overlapping genes

identified in the network pharmacology analysis of the treatment of

CSDHs with atorvastatin were notably enriched in BPs related to

inflammation such as ‘Hemostasis’ and ‘Leukocyte migration’, as

well as key pathways such as the ‘TNF signaling pathway’, ‘IL-17

signaling pathway’ and ‘HIF-1 signaling pathway’. These results

provide support for the hypothesis that atorvastatin may interrupt

multiple pathogenic associations in the CSDH cycle. In the present

study, GO enrichment analysis revealed that the

atorvastatin-associated genes were significantly enriched in

biological processes related to these key mechanisms. Among the top

10 enriched processes, ‘Wound healing’ reflected an association to

angiogenesis and inflammation (36), ‘Blood coagulation’ and ‘Hemostasis’

were associated with coagulation-fibrinolysis balance (37) and terms such as ‘Leukocyte

chemotaxis,’ ‘Leukocyte migration’ and ‘Cell chemotaxis’ were

indicative of inflammatory regulation (38). Based on the subsequent PPI network

analysis performed in the present study and supporting literature

(1-3),

five key genes (IL-6, CXCL-8, MMP-2, MMP-9 and SERPINE-1) were

identified as central regulators of inflammation, angiogenesis and

coagulation/fibrinolysis in the treatment of CSDHs with

atorvastatin. These genes were selected for further mechanistic

investigation to elucidate the molecular basis of the therapeutic

effects of atorvastatin. IL-6 and CXCL-8 (also known as IL-8) are

pro-inflammatory cytokines predominantly secreted by fibroblasts,

endothelial cells and various immune cells such as monocytes,

macrophages, neutrophils and T lymphocytes (39). IL-6 mediates acute-phase

inflammatory responses, immune cell differentiation, thrombopoiesis

and leukocyte recruitment (40),

whereas CXCL-8 has a key role in immune cell chemotaxis and

promotes angiogenesis by stimulating endothelial cell proliferation

and tube formation (41). Elevated

levels of both cytokines have been detected in the hematoma fluid

from patients with CSDHs, particularly those with recurrent

hematomas (42). MMP-2 and MMP-9

are involved in the degradation of extracellular matrix (ECM)

components and are functionally linked to both inflammation and

angiogenesis, and aberrant upregulation of these enzymes

contributes to neovascular instability and increases the risk of

recurrent hemorrhage in CSDHs (43). Additionally, MMP-2 and MMP-9

participate in inflammatory signaling cascades by modulating the

activity of cytokines and their receptors (44). Elevated levels of both enzymes have

been observed in the hematoma fluid from patients with CSDHs

(45). SERPINE-1, also known as

plasminogen activator inhibitor-1, is a serine protease inhibitor

predominantly expressed by endothelial cells; it regulates

fibrinolysis by inhibiting tissue-type and urokinase-type

plasminogen activators and has been implicated in multiple

pathological processes, including inflammation, oxidative stress,

fibrosis and macrophage migration (46).

In the present study, molecular docking simulations

demonstrated that atorvastatin stably bound to the protein

structures encoded by the five identified target genes. Consistent

with these predictions, in vitro experiments revealed that

atorvastatin treatment significantly reduced the secretion of

ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 in TNF-α-stimulated HUVECs. These adhesion

molecules are well-established biomarkers of endothelial

inflammation (47), and their

downregulation indicates effective suppression of TNF-α-mediated

inflammatory responses. Additionally, atorvastatin significantly

decreased the secretion of IL-6 and CXCL-8 and the mRNA expression

of MMP-2 and MMP-9, supporting the mechanistic insights derived

from both the network pharmacology and docking analyses. Therefore,

the reduction in IL-6/CXCL-8 secretion and MMP-2/MMP-9 expression

in HUVECs, coupled with the improvement in endothelial barrier

integrity, may help limit microvascular leakage and inflammatory

cell infiltration in hematoma membranes. These effects could, in

turn, contribute to stabilization of neovessels and reduced

re-bleeding, ultimately facilitating hematoma resolution in

vivo; these mechanisms will be validated in animal models of

CSDH in future studies. It is noteworthy that fibrinolysis may

exert bidirectional effects in the pathogenesis and progression of

CSDHs; in the pathophysiological setting of CSDHs, excessive

fibrinolysis may accelerate ECM breakdown, potentially triggering

pro-MMP activation and compromising vascular stability, thereby

increasing the risk of microvascular leakage or re-bleeding

(33,34). Paradoxically, hyperfibrinolysis

could also promote hematoma resolution by facilitating clot

degradation and reducing postoperative hematoma recurrence

(48). Therefore, as an important

regulator of fibrinolysis, it is necessary to avoid overly

simplistic conclusions regarding the regulation of SERPINE-1 in

CSDHs. Future work should employ time-course analyses of

fibrinolytic markers (such as tPA, plasmin activity and D-dimer),

ECM degradation products, MMP/tissue inhibitors of

metalloproteinase activity profiles and fibrosis markers (such as

collagen I/III, α-smooth muscle actin and fibronectin) in both

in vitro co-culture systems and in vivo CSDH models.

Such integrative approaches will enable a more precise

understanding of whether the effects of atorvastatin on SERPINE-1

confer a benefit or risk in the context of CSDH management.

Notably, in the present study, atorvastatin was

demonstrated to significantly improve endothelial barrier integrity

under inflammatory conditions as evidenced by the reduced

FITC-dextran permeability, a key pathological feature implicated in

CSDH progression (2,3). This improvement was accompanied by a

concentration-dependent decrease in both cytokine secretion and

permeability, underscoring the therapeutic window and potency of

atorvastatin in mitigating endothelial dysfunction. Moreover, the

present study demonstrated that TNF-α suppressed tube formation in

HUVECs, supporting the notion that inflammatory cytokines impair

normal angiogenesis and contribute to the formation of fragile,

leaky vessels in CSDH (2,3). Atorvastatin alleviated this

inhibitory effect, which may be attributed to its anti-inflammatory

and endothelial-protective properties. A previous study has

demonstrated that atorvastatin reduces CSDH in animal models by

promoting angiogenesis (49).

Collectively, these in vitro findings support the hypothesis

that atorvastatin may exert therapeutic benefits in CSDH not only

through inflammation suppression but also by improving the quality

of angiogenesis within the hematoma capsule.

Taken together, the findings of the present study

suggest that atorvastatin may interrupt the self-sustaining CSDH

cycle by inhibiting inflammatory signaling, modulating fibrinolytic

and angiogenic processes, suppressing the formation of immature

leaky vessels, limiting immune cell infiltration and preserving

endothelial function. These combined effects may facilitate

hematoma liquefaction and enhance spontaneous resorption. Despite

these promising results, it is important to recognize that the

pathogenesis of CSDHs is multifaceted and that the regulatory

effects of atorvastatin likely extend beyond the five core targets

identified in the present study. Therefore, the proposed mechanism

should be viewed as a partial representation of the therapeutic

actions of atorvastatin. In the present study, KEGG pathway

enrichment analysis further indicated that multiple classical

inflammatory and angiogenic signaling pathways may be implicated in

the mode of action of atorvastatin, including the ‘HIF-1 signaling

pathway’, ‘TNF signaling pathway’, ‘IL-17 signaling pathway’,

‘Toll-like receptor signaling pathway’ and the ‘PI3K-Akt signaling

pathway’. Furthermore, clinical evidence has identified diabetes

mellitus and atherosclerosis as notable risk factors for both the

onset and recurrence of CSDH (50,51).

Consistently, the KEGG analysis in the present study revealed the

enrichment of pathways related to these metabolic and vascular

disorders, such as ‘AGE-RAGE signaling pathway in diabetic

complications’, ‘Fluid shear stress and atherosclerosis’ and

‘Diabetic cardiomyopathy’, providing potential avenues for

exploring the broader mechanistic effects of atorvastatin in CSDHs.

Additionally, several pathways associated with infectious diseases

and malignancies were also enriched. Prior studies have reported

associations between CSDH recurrence and underlying malignancy

(52) or chronic infection

(53). These findings suggest that

the systemic health status of patients may influence disease

progression and that statins may offer a benefit in patient

subgroups with these comorbidities. The roles of these

comorbidities in CSDH pathophysiology, as well as their potential

modulation by atorvastatin, warrant further investigation. Although

atorvastatin is primarily used to regulate lipid metabolism

(6), the results of the enrichment

analysis in the present study did not clearly indicate a potential

role of lipid metabolism regulation in its treatment of CSDH.

Therefore, the in vitro endothelial inflammation model

established in the present study does not involve lipid metabolism,

and the observed molecular effects are more likely attributable to

the pleiotropic effects of atorvastatin rather than its

lipid-lowering properties. Nonetheless, it must be acknowledged

that in vivo, lipid regulation may synergistically

contribute to endothelial protection (54). In future studies, control compounds

with lipid-lowering effects but minimal pleiotropic activity will

be used to help delineate the relative contributions of each

mechanism.

Despite the promising findings of the present study,

several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the study relied

solely on in vitro experiments using HUVECs as a model for

endothelial inflammation; although this approach provides

mechanistic insights, it may not fully replicate the

cerebrovascular endothelial environment of CSDHs, nor simulate

interactions with macrophages and fibroblasts. Second, the key

inflammatory regulatory signaling pathways of statins, such as the

NF-κB pathway, have not been directly evaluated. Third, the network

pharmacology analysis was based on existing public databases, which

may not cover all relevant molecular interactions or reflect

tissue-specific gene expression profiles. In terms of target gene

selection, while the method employed in the present study provides

clear traceability, it may underestimate the extent of functional

overlap. The selection of five core target genes, while supported

by the established PPI network and functional relevance, may

overlook other key targets involved in CSDH progression. Moreover,

the present study did not examine the long-term treatment outcomes

of atorvastatin. Finally, the lack of in vivo validation,

such as animal model experiments, limits the translational

applicability of the current findings. Future studies should

incorporate in vivo CSDH models for validation of the core

molecular targets, integrate proteomic and transcriptomic analyses

to delineate the downstream signaling networks and assess the

dose-response relationships and pharmacokinetic profiles of

atorvastatin in animal models. In addition, broader target

selection and verification such as scoring-based or

relevance-weighted intersections, along with the incorporation of

clinical data, will be essential to more comprehensively elucidate

the therapeutic mechanisms of atorvastatin on CSDHs. The next phase

of research will also focus on p65 nuclear translocation assays and

phosphorylated p65 expression by western blotting to investigate

whether the anti-inflammatory effects of atorvastatin are mediated,

at least in part, through NF-κB inhibition. Meanwhile,

pathway-specific verifications, including HIF-1α and IL-17 protein

levels, will also be prioritized in future mechanistic studies.

Furthermore, future studies will incorporate direct assessments of

ECM remodeling, such as collagen degradation assays, gelatin

zymography and immunofluorescent staining for ECM components, to

confirm whether the downregulation of MMP-2 and MMP-9 contributes

to the preservation of ECM integrity.

In conclusion, the present study identified key

molecular targets and signaling pathways potentially involved in

the therapeutic effects of atorvastatin on CSDHs. The results from

the integrated network pharmacology analysis and in vitro

experimental validation suggest that atorvastatin may exert its

effects by modulating inflammation, angiogenesis and fibrinolysis.

These findings provide a mechanistic foundation and valuable

reference for future preclinical and clinical studies aimed at

elucidating the therapeutic potential of atorvastatin in managing

CSDHs.

Supplementary Material

Key hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic

interactions between atorvastatin and potential target gene

proteins predicted by molecular docking.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported by grant from Key

Research and Development Plan of Shaanxi Province, China (grant no.

2024SF-YBXM-047).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

CL conceived and designed the study. JY performed

the in vitro experiments. XW conducted the bioinformatics

analyses. CL and JY contributed primarily to manuscript drafting

and confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors

reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Use of artificial intelligence tools

During the preparation of this work, AI tools were

used to improve the readability and language of the manuscript, and

subsequently, the authors revised and edited the content produced

by the AI tools as necessary, taking full responsibility for the

ultimate content of the present manuscript.

References

|

1

|

Nouri A, Gondar R, Schaller K and Meling

T: Chronic subdural hematoma (cSDH): A review of the current state

of the art. Brain Spine. 1(100300)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Zhong D, Cheng H, Xian Z, Ren Y, Li H, Ou

X and Liu P: Advances in pathogenic mechanisms, diagnostic methods,

surgical and non-surgical treatment, and potential recurrence

factors of Chronic Subdural Hematoma: A review. Clin Neurol

Neurosurg. 242(108323)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Feghali J, Yang W and Huang J: Updates in

chronic subdural hematoma: Epidemiology, etiology, pathogenesis,

treatment, and outcome. World Neurosurg. 141:339–345.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Liu T, Zhao Z, Liu M, An S, Nie M, Liu X,

Qian Y, Tian Y, Zhang J and Jiang R: The pharmacological landscape

of chronic subdural hematoma: A systematic review and network

meta-analysis of randomized and non-randomized controlled studies.

Burns Trauma. 12(tkae034)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Verma Y, Abdelghaffar M, Verma O, Gajjar

A, Ghozy S and Kallmes DF: Bevacizumab: The future of chronic

subdural hematoma. Interv Neuroradiol: November 21, 2024 (Epub

ahead of print).

|

|

6

|

Morofuji Y, Nakagawa S, Ujifuku K,

Fujimoto T, Otsuka K, Niwa M and Tsutsumi K: Beyond lipid-lowering:

Effects of statins on cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases

and cancer. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 15(151)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Araujo FA, Rocha MA, Mendes JB and Andrade

SP: Atorvastatin inhibits inflammatory angiogenesis in mice through

down regulation of VEGF, TNF-alpha and TGF-beta1. Biomed

Pharmacother. 64:29–34. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Kim SK, Choe JY, Kim JW, Park KY and Kim

B: Anti-Inflammatory effect of atorvastatin and rosuvastatin on

monosodium urate-induced inflammation through IL-37/Smad3-complex

activation in an in vitro study using THP-1 macrophages.

Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 17(883)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Chan DY, Chan DT, Sun TF, Ng SC, Wong GK

and Poon WS: The use of atorvastatin for chronic subdural

haematoma: A retrospective cohort comparison study. Br J Neurosurg.

31:72–77. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Jiang R, Zhao S, Wang R, Feng H, Zhang J,

Li X, Mao Y, Yuan X, Fei Z, Zhao Y, et al: Safety and efficacy of

atorvastatin for chronic subdural hematoma in chinese patients: A

randomized ClinicalTrial. JAMA Neurol. 75:1338–1346.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Monteiro GA, Queiroz TS, Goncalves OR,

Cavalcante-Neto JF, Batista S, Rabelo NN, Welling LC, Figueiredo

EG, Leal PRL and Solla DJF: Efficacy and safety of atorvastatin for

chronic subdural hematoma: An updated systematic review and

meta-analysis. World Neurosurg. 188:177–184. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Quan W, Zhang Z, Li P, Tian Q, Huang J,

Qian Y, Gao C, Su W, Wang Z, Zhang J, et al: Role of regulatory T

cells in atorvastatin induced absorption of chronic subdural

hematoma in rats. Aging Dis. 10:992–1002. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Yang L, Li N, Yang L, Wang D, Qiang S and

Zhao Z: Atorvastatin-induced absorption of chronic subdural

hematoma is partially attributed to the polarization of

macrophages. J Mol Neurosci. 72:565–573. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Liang C, Zhang B, Li R, Guo S and Fan X:

Network pharmacology -based study on the mechanism of traditional

Chinese medicine in the treatment of glioblastoma multiforme. BMC

Complement Med Ther. 23(342)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Carlson M: Genome wide annotation for

Human. Bioconductor, 2022. https://bioconductor.org/packages/org.Hs.eg.db.

|

|

16

|

Yu G, Wang LG, Han Y and He QY:

ClusterProfiler: An R package for comparing biological themes among

gene clusters. OMICS. 16:284–287. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Yu G: enrichplot: Visualization of

Functional Enrichment Result. Bioconductor, 2022. https://bioconductor.org/packages/enrichplot.

|

|

18

|

Luo W and Brouwer C: Pathview: An

R/Bioconductor package for pathway-based data integration and

visualization. Bioinformatics. 29:1830–1831. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Wickham H: ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for

Data Analysis. 1st Edition. Springer, New York, NY, 2009.

|

|

20

|

Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, Baliga NS,

Wang JT, Ramage D, Amin N, Schwikowski B and Ideker T: Cytoscape: A

software environment for integrated models of biomolecular

interaction networks. Genome Res. 13:2498–2504. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Bao XM, Wu CF and Lu GP: Atorvastatin

attenuates homocysteine-induced apoptosis in human umbilical vein

endothelial cells via inhibiting NADPH oxidase-related oxidative

stress-triggered p38MAPK signaling. Acta Pharmacol Sin.

30:1392–1398. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Li D, Chen H, Romeo F, Sawamura T, Saldeen

T and Mehta JL: Statins modulate oxidized low-density

lipoprotein-mediated adhesion molecule expression in human coronary

artery endothelial cells: Role of LOX-1. J Pharmacol Exp Ther.

302:601–605. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: . Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Liang C, Wei T, Zhang T and Niu C:

Adipose-derived stem cell-mediated alphastatin targeting delivery

system inhibits angiogenesis and tumor growth in glioma. Mol Med

Rep. 28(215)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Shityakov S and Förster C: In silico

predictive model to determine vector-mediated transport properties

for the blood-brain barrier choline transporter. Adv Appl Bioinform

Chem. 7:23–36. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Hsin KY, Ghosh S and Kitano H: Combining

machine learning systems and multiple docking simulation packages

to improve docking prediction reliability for network pharmacology.

PLoS One. 8(e83922)2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Xiong L, Chen Q and Liu H: Network

pharmacology and molecular docking identified IL-6 as a critical

target of Qing Yan He Ji against COVID-19. Medicine (Baltimore).

103(e40720)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Ahmad A, Sayed A, Ginnebaugh KR, Sharma V,

Suri A, Saraph A, Padhye S and Sarkar FH: Molecular docking and

inhibition of matrix metalloproteinase-2 by novel

difluorinatedbenzylidene curcumin analog. Am J Transl Res.

7:298–308. 2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Kumar NK, Geervani VS, Kumar RSM, Singh S,

Abhishek M and Manimozhi M: Data-driven dentistry: Computational

revelations redefining pulp capping. J Conserv Dent Endod.

27:649–653. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Dos Santos RV, Barrionuevo MVF, Vieira

MRF, Mazoni I and Tasic L: Plasminogen activator inhibitors in

thrombosis: Structural analysis and potential natural inhibitors.

ACS Omega. 10:27348–27362. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Madej M, Halama A, Chrobak E and Gola JM:

Time-dependent impact of betulin and its derivatives on IL-8

expression in colorectal cancer cells with molecular docking

studies. Int J Mol Sci. 26(6186)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Weigel R, Schilling L and Krauss JK: The

pathophysiology of chronic subdural hematoma revisited: Emphasis on

aging processes as key factor. Geroscience. 44:1353–1371.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Jensen TSR, Olsen MH, Lelkaitis G, Kjaer

A, Binderup T and Fugleholm K: Urokinase plasminogen activator

receptor: An important focal player in chronic subdural hematoma?

Inflammation. 47:1015–1027. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Tamura R, Sato M, Yoshida K and Toda M:

History and current progress of chronic subdural hematoma. J Neurol

Sci. 429(118066)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Katano H, Kamiya K, Mase M, Tanikawa M and

Yamada K: Tissue plasminogen activator in chronic subdural

hematomas as a predictor of recurrence. J Neurosurg. 104:79–84.

2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Shi Z, Yao C, Shui Y, Li S and Yan H:

Research progress on the mechanism of angiogenesis in wound repair

and regeneration. Front Physiol. 14(1284981)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Costantini TW, Kornblith LZ, Pritts T and

Coimbra R: The intersection of coagulation activation and

inflammation after injury: What you need to know. J Trauma Acute

Care Surg. 96:347–356. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Cambier S, Gouwy M and Proost P: The

chemokines CXCL8 and CXCL12: molecular and functional properties,

role in disease and efforts towards pharmacological intervention.

Cell Mol Immunol. 20:217–251. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Adumitrachioaiei H, Sasaran MO and

Marginean CO: The diagnostic and prognostic role of interleukin 6

and interleukin 8 in childhood acute gastroenteritis-a review of

the literature. Int J Mol Sci. 25(7655)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Schumertl T, Lokau J, Rose-John S and

Garbers C: Function and proteolytic generation of the soluble

interleukin-6 receptor in health and disease. Biochim Biophys Acta

Mol Cell Res. 1869(119143)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Matsushima K, Yang D and Oppenheim JJ:

Interleukin-8: An evolving chemokine. Cytokine.

153(155828)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Hong HJ, Kim YJ, Yi HJ, Ko Y, Oh SJ and

Kim JM: Role of angiogenic growth factors and inflammatory cytokine

on recurrence of chronic subdural hematoma. Surg Neurol.

71:161–165; discussion 165-166. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Mustafa S, Koran S and AlOmair L: Insights

into the role of matrix metalloproteinases in cancer and its

various therapeutic aspects: A review. Front Mol Biosci.

9(896099)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Muneer PMA, Pfister BJ, Haorah J and

Chandra N: Role of matrix metalloproteinases in the pathogenesis of

traumatic brain injury. Mol Neurobiol. 53:6106–6123.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Hua C, Zhao G, Feng Y, Yuan H, Song H and

Bie L: Role of matrix metalloproteinase-2, matrix

metalloproteinase-9, and vascular endothelial growth factor in the

development of chronic subdural hematoma. J Neurotrauma. 33:65–70.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Kwak SY, Park S, Kim H, Lee SJ, Jang WS,

Kim MJ, Lee S, Jang WI, Kim AR, Kim EH, et al: Atorvastatin

inhibits endothelial PAI-1-mediated monocyte migration and

alleviates radiation-induced enteropathy. Int J Mol Sci.

22(1828)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Hou X and Pei F: Estradiol inhibits

cytokine-induced expression of VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 in cultured human

endothelial cells via AMPK/PPARalpha activation. Cell Biochem

Biophys. 72:709–717. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

O YM, Tsang SL and Leung GK:

Fibrinolytic-facilitated chronic subdural hematoma drainage-A

systematic review. World Neurosurg. 150:e408–e419. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Wang D, Li T, Wei H, Wang Y, Yang G, Tian

Y, Zhao Z, Wang L, Yu S, Zhang Y, et al: Atorvastatin enhances

angiogenesis to reduce subdural hematoma in a rat model. J Neurol

Sci. 362:91–99. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Chen M, Da L, Zhang Q, Liu J, Tang J and

Zha Z: Development of a predictive model for assessing the risk

factors associated with recurrence following surgical treatment of

chronic subdural hematoma. Front Surg. 11(1429128)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Jensen TSR, Thiesson EM, Fugleholm K,

Wohlfahrt J and Munch TN: Inflammatory risk factors for chronic

subdural hematoma in a nationwide cohort. J Inflamm Res.

17:8261–8270. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Hori YS, Aoi M, Oda K and Fukuhara T:

Presence of a malignant tumor as a novel predictive factor for

repeated recurrences of chronic subdural hematoma. World Neurosurg.

105:714–719. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Dubinski D, Won SY, Trnovec S, Gounko K,

Baumgarten P, Warnke P, Cantre D, Behmanesh B, Bernstock JD,

Freiman TM, et al: Recurrence of chronic subdural hematoma due to

low-grade infection. Front Neurol. 13(1012255)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Hermida N and Balligand JL: Low-density

lipoprotein-cholesterol-induced endothelial dysfunction and

oxidative stress: The role of statins. Antioxid Redox Signal.

20:1216–1237. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|