Introduction

Endothelial cell dysfunction serves as a key

foundation for the pathophysiology of atherosclerosis (AS). Normal

endothelial cells regulate the vascular tone, prevent thrombosis

and modulate inflammation, serving key roles in maintaining

vascular homeostasis and inhibiting AS (1). The initiation of AS involves

endothelial apoptosis, ferroptosis and autophagy, among other

programmed cell death mechanisms (2,3).

Ferroptosis, a previously identified form of cell death, is

distinct from apoptosis and autophagy and is characterized by

molecular changes such as glutathione (GSH) depletion or

GSH-peroxidase (GPX) inactivation, increased intracellular free

iron levels and enhanced reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation,

ultimately resulting in the accumulation of toxic lipid peroxides

within cells (4-9).

During ferroptosis, mitochondrial abnormalities such as

condensation or swelling, increased membrane density, decreased or

absent cristae and outer membrane rupture are commonly observed

(10). Previous studies have

indicated a close association between ferroptosis and various

cardiovascular diseases, including AS (11), acute myocardial infarction

(12), ischemia/reperfusion injury

(13), cardiomyopathy and heart

failure (14,15).

GPX4, one of the eight GPX proteins in mammals, is

considered to be the only enzyme within cells capable of directly

reducing phospholipid hydroperoxides. GPX4 converts lipid

hydroperoxides into lipid alcohols, and the inhibition of GPX4

synthesis leads to exacerbated lipid peroxidation and subsequent

ferroptosis (16,17). GSH serves as a key antioxidant in

the body and acts as a co-factor for GPX4, participating in the

reduction of lipid hydroperoxides (18). The depletion of GSH can result in

GPX4 inactivation and increased production of intracellular lipid

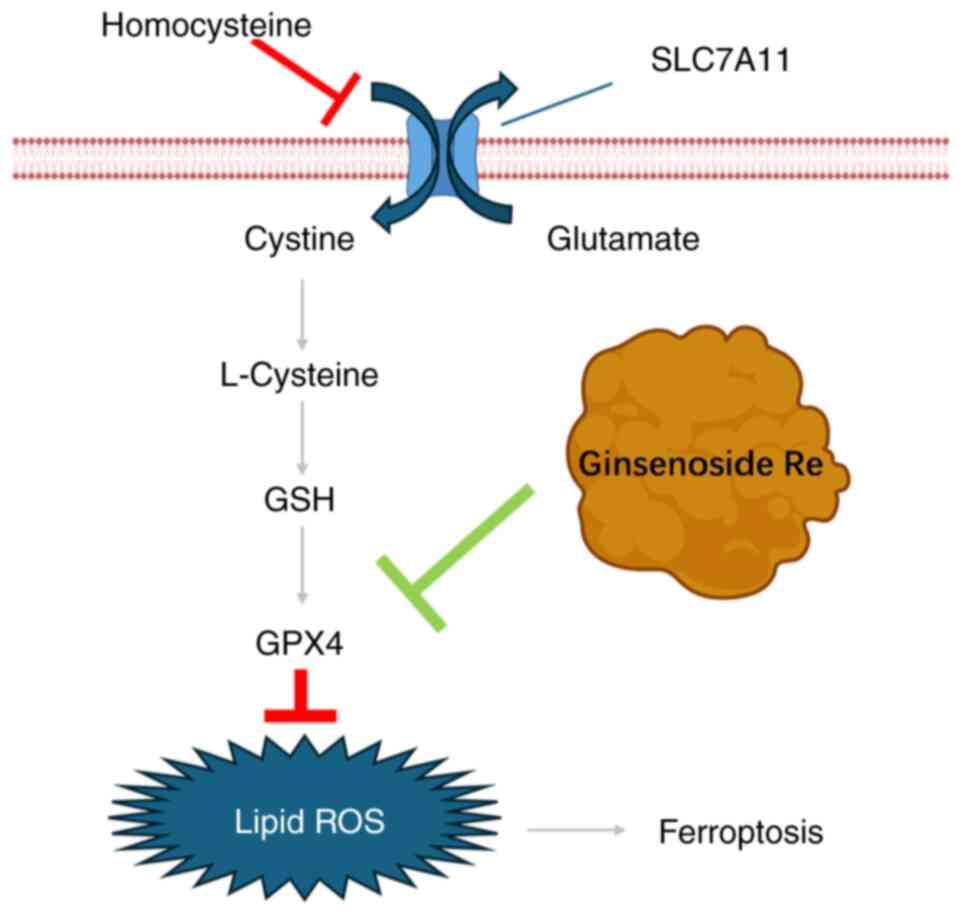

peroxides, ultimately triggering ferroptosis. Extracellular cystine

is transported into cells through solute carrier family 7 member 11

(SLC7A11) with intracellular glutamate, which is then converted to

the cysteine required for GSH synthesis. Inhibition of cystine

uptake leads to reduced GSH synthesis, resulting in the

accumulation of lipid peroxidation products and subsequent

ferroptosis (19).

Homocysteine (Hcy) is a sulfur-containing amino

acid, and high levels of homocysteine in the body can be attributed

to factors such as the deficiency of methionine, folic acid,

vitamin B12, B6 and B2 in the diet, and abnormal Hcy metabolic

pathways. High levels of Hcy can lead to AS, hypertension and

congestive heart failure, among other conditions (20,21).

Hcy weakens vascular repair function through mechanisms such as

oxidative stress, damage to the NO system and mitochondrial

destruction, leading to vascular injury (22). A previous study indicated that Hcy

can promote ferroptosis mediated by GPX4 methylation in nucleus

pulposus cells and that folic acid intervention can reduce

ferroptosis-related indicators induced by Hcy (23). However, studies on Hcy-induced

endothelial cell ferroptosis are limited.

Ginsenoside Re, a dietary phytochemical (24), possesses advantages such as easy

accessibility, low cost, efficient and simple purification

techniques as well as low toxicity (25). Notably, ginsenoside Re exhibits

various pharmacological effects, including antidiabetic (26), neuroregulatory (27), anti-infective (28), cardioprotective (29) and antitumor activities (30) and can alleviate the cellular

oxidative stress response (31).

However, studies on whether ginsenoside Re can inhibit ferroptosis

are scarce. The present study aimed to establish a model of

Hcy-induced endothelial cell damage and to investigate whether

ginsenoside Re can suppress Hcy-induced endothelial cell

ferroptosis by upregulating the expression of GPX4, thus providing

a basis for the application of ginsenoside Re in anti-AS therapy

(Fig. 1).

Materials and methods

Cell culture

The EA.hy926 cell line was purchased (cat. no.

CL-0272; Procell®) and cultured in DMEM/F12 (cat. no.

11330032; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at 37˚C in a

humidified incubator with 5% CO2. All media contained

10% FBS (cat. no. LV-FBSCN500S; Ausgenex Pvt Ltd.), 100 U/ml

penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin (cat. no. C0222; Beyotime

Biotechnology).

Cell toxicity assay

The cytotoxic effect of Hcy (cat. no. H4628;

MilliporeSigma), ferroptosis inducers erastin (cat. no. HY-15763;

MedChemExpress) and ginsenoside Re (cat. no. SG8310; Beijing

Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) on EA.hy926 cells was

evaluated using an MTT assay at 37˚C. The cells were seeded at

1x105 cells per well in a 96-well plate and allowed to

adhere overnight. Subsequently, the cells were treated with

different concentrations of Hcy (0-5 mM), erastin (0-20 µM) and

ginsenoside Re (0-200 µM) in the culture medium for 48 h.

Afterwards, 50 ml MTT was added and the resulting formazan crystals

were dissolved in 150 µl DMSO. The absorbance was measured at 570

nm per well with a 96-well plate reader, and cell viability was

expressed as the percentage of untreated controls. Our previous

study demonstrated that exposure to Hcy (0-8 mM) resulted in a

progressive reduction in cell viability from 100 to 30% (32). Consequently, in the present study,

Hcy concentrations of 0-5 mM were selected.

Flow cytometry (FCM) to assess the

cellular levels of lipid ROS (Lip-ROS)

EA.hy926 cells were cultured overnight in a 6-well

culture plate (4x105 cells/well). After discarding the

culture medium from each well, cells were washed three times with

PBS. Subsequently, the cells were treated with Hcy and ginsenoside

Re and divided into the following four groups: The control group

(untreated), the Hcy (2 mM) group, the Hcy (2 mM) + ginsenoside Re

(12 µM) group and the Hcy (2 mM) + ginsenoside Re (24 µM) group.

All groups were cocultured at 37˚C for 24 h. After 24 h of drug

treatment, cell staining was performed. First, the culture medium

was discarded from each well and 1 ml/well sterile PBS solution was

added to remove any residual drugs. Subsequently, the pre-prepared

BODIPY™ 581/591 C11 probe solution (cat. no. D3861;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was diluted to 10 µM and 2 ml

diluted probe solution was slowly added to each well of the 6-well

plate. The plate was covered with aluminum foil and incubated in a

37˚C cell culture incubator for 30 min.

After incubation, the probe solution was aspirated

and the cells were washed 2-3 times with sterile PBS. After

washing, 0.5 ml EDTA-free trypsin was added to digest the cells and

the plate was centrifuged at 415 x g at 37˚C for 5 min. After

centrifugation, the supernatant was removed and 1 ml PBS solution

was added to resuspend the cells. The resuspended cells were

centrifuged at 415 x g at 37˚C for 5 min to remove as much residual

trypsin digestion solution from the cell surface as possible. The

residual solution in the tube was then removed and an appropriate

amount of PBS buffer was added to resuspend the cells. The stained

cells were transferred to a FCM tube and labeled, with all

procedures conducted in the dark. Cell lipid peroxidation levels

were measured using FCM with the BD FACSCalibur™ flow

cytometer (BD Biosciences). A total of 10,000 gated events were

recorded for each sample and analysis was performed using the BD

FACSDiva™ software (version 8.0.1; BD Biosciences).

FCM to assess the intracellular levels

of ROS

Experimental grouping and cell culture methods were

performed as aforementioned. After 24 h of drug treatment, cell

staining was performed. First, the culture medium was removed from

each well and 1 ml/well sterile PBS solution was added to remove

any residual drugs. Subsequently, the pre-prepared

2',7'-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate probe solution (cat. no.

S0033S; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) was diluted to 10 µM

and 2 ml diluted probe solution was slowly added to each well of

the 6-well plate. The plate was covered with aluminum foil and

incubate in a 37˚C cell incubator for 30 min. Stained cells were

then transferred to FCM tubes and labeled, with all procedures

conducted in the dark. FCM was performed using the BD FACSCalibur

flow cytometer to measure cellular ROS levels. A total of 10,000

gated events were recorded for each sample and analysis was

performed using the BD FACSDiva™ software (version

8.0.1).

Fluorescence detection of the levels

of cellular Lip-ROS

After 24 h of drug treatment as aforementioned, cell

staining was conducted. The initial steps of cell staining were the

same as those for ROS detection. Subsequently, the cells were

stained with Antifade Mounting Medium with DAPI (cat. no. P0131;

Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). Images were captured using a

fluorescence microscope (x10 magnification; Olympus Corporation) in

the dark. Quantitative analysis was performed using ImageJ software

(version 1.54; National Institutes of Health).

Determination of intracellular total

iron ion content

EA.hy926 cells were cultured overnight in 6-well

plates (4x105 cells/well) and divided into four

treatment groups as aforementioned, namely the control group, the

Hcy (2 mM) group, the Hcy (2 mM) + ginsenoside Re (12 µM) group and

the Hcy (2 mM) + ginsenoside Re (24 µM) group, with each group

incubated for 24 h. After treatment, cells were collected and

washed twice with cold sterile PBS, followed by low-speed

centrifugation (37˚C, 415 x g, 5 min). PBS was then aspirated and

100-200 µl lysis buffer in the Total Iron Content Colorimetric

Assay Kit (cat. no. E1042; Applygen Technologies, Inc.) was added.

The cells were vigorously shaken or vortexed for 20-30 sec, then

lysis was conducted at 4˚C for 2 h, before centrifugation at 4˚C at

12,000 x g for 5 min to collect the supernatant for subsequent

determination of iron ion concentration and protein concentration

was measured using a BCA assay. Preparation of the standard

solution was then performed. A 3 mM standard solution was diluted

with the dilution solution provided in the Total Iron Content

Colorimetric Assay Kit to concentrations of 300, 150, 75, 37.5,

18.75, 9.38 and 4.69 µM. A mixture of reagent 2 and 4.5% potassium

permanganate solution was prepared in a 1:1 ratio to form solution

A. The blank control group, standard group and sample group were

set up and mixed with solution A before being incubated in a water

bath at 60˚C for 1 h. After the tubes cooled to room temperature,

the liquid remaining on the wall and cap of the tubes was

centrifuged at low speed (37˚C, 415 x g, 5 min) to the bottom of

the tubes. Subsequently, 30 µl iron ion detection reagent, included

in the aforementioned kit, was added and the mixture was incubated

at room temperature for 30 min. After centrifugation at 4˚C at

12,000 x g for 5 min, the supernatant was collected. Finally, 200

µl sample was added to each well of a 96-well plate and the

absorbance of the samples was measured at 550 nm using a microplate

reader. The relative iron ion levels were checked in the cells.

Determination of the intracellular GSH

concentration

The cells were ultrasonically crushed using PBS as

the homogenizing medium and then centrifuged to take the

supernatant for determination. A total of 0.1 ml cell supernatant

was removed, and then 0.1 ml reagent 1 (precipitating agent) was

added to the tube and thorough mixing was performed. The mixture

was centrifuged at 37˚C at 205 x g for 10 min and the supernatant

was collected for measurement. After the control group, Hcy group,

low-dose ginsenoside Re + Hcy group and high-dose ginsenoside Re +

Hcy group were treated with reagent 1, 100 µl reagent 2 (buffer

solution) and 25 µl reagent 3 (color developer) were added to the

supernatant, mixed and allowed to stand for 5 min. The absorbance

of the samples was measured at 405 nm using a microplate reader.

GSH standard solutions were prepared by diluting a GSH standard

stock solution to concentrations of 100, 50, 20, 10, 5 and 0 µM.

All reagents used were included in the GSH Assay Kit (cat. no.

A006-2-1; Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute). The GSH

content was analyzed based on the measured absorbance values using

a standard curve. Based on the absorbance measurement value, the

relative GSH level was checked in the cells.

Determination of the intracellular

malondialdehyde (MDA) content

To measure MDA content using an MDA kit (cat. no.

A003-4-1; Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute), 100 µl

anhydrous ethanol, standard solution and test samples were mixed

separately with 1,000 µl working solution to prepare control tubes,

standard tubes and sample tubes, respectively. After thorough

mixing, the tubes were heated in a water bath at >95˚C for 40

min. The solutions were then removed from the water bath and cooled

under running water, before being centrifuged at 37˚C at 268 x g

for 10 min. The optical density (OD) of the blank plate was

measured at 530 nm using a microplate reader. Subsequently, 0.25 ml

of each sample was transferred to a new 96-well plate and the OD

value of each well was measured using a microplate reader (the OD

value of the blank plate was subtracted from the sample OD value).

The results were normalized to the percentage of the control

group.

Molecular docking

Molecular docking evaluation of ginsenoside Re

combined with different proteins was performed. Briefly, the 3D

molecular structure of ginsenoside Re was retrieved from the

PubChem database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). In addition, the

X-ray crystal structures of the GPX4, SLC7A11 and acyl-CoA

synthetase long-chain family member 4 (ACSL4) proteins were

obtained from Protein Data Bank (http://www.rcsb.org/). For protein preparation, PyMOL

(https://github.com/schrodinger/pymol-open-source)

(version 2.5.2) was used to remove water molecules and heteroatoms

and the proteins were saved in ‘pdb format’. AutoDock (https://autodock.scripps.edu/download-autodock4/)

(version 4.2.6) and PyMOL software were used to perform docking

studies between ginsenoside Re and GPX4, SLC7A11 and ACSL4

proteins. The grid-box function of AutoDock Tools was used to

define specific pockets of active ingredients for protein-protein

interaction binding to proteins. Subsequently, molecular docking

analysis was performed using the command prompt and the results

were displayed using PyMOL. The default settings of the software

were used.

Western blotting

Cells were seeded on a 6-well plate at

2.5x105 cells/well and allowed to adhere overnight.

Subsequently, the cells were incubated with Hcy (2 mM), Hcy (2 mM)

+ ginsenoside Re (12 µM) or Hcy (2 mM) + ginsenoside Re (24 µM) for

24 h, after which, the medium in the 6-well plate was discarded.

Precooled PBS was then added to rinse the cells twice. A prepared

protein lysis solution RIPA (cat. no. P0038; Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology) + PMSF (cat. no. ST507; Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology) (RIPA:PMSF, 100:1) was added to lyse the cells for

30 min at 4˚C (shaking the 6-well plate every 10 min), the cells

were quickly collected with a cell scraper and centrifuged using a

high-speed refrigerated centrifuge at 950 x g for 15 min at 4˚C.

The supernatant was aspirated and a BCA protein assay kit was used

to determine the total protein concentration. Subsequently, western

blotting of the lysates was performed. Equal amounts of protein (20

µg per lane) were electrophoresed on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels

and transferred onto 0.45 µm PVDF membranes. The membranes were

then blocked with 5% skimmed milk for 1 h at room temperature,

followed by an overnight incubation with the primary antibody at

4˚C. The primary antibodies used included anti-GPX4 (1;2,000; cat.

no. ab125066; Abcam), anti- SLC7A11 (1;2,000; cat. no. ab300667;

Abcam), anti-ACSL4 (1;2,000; cat. no. ab155282; Abcam) and

anti-GAPDH (1:2,000; cat. no. ab8245; Abcam). Following washes with

TBST buffer (0.05% Tween-20), the membranes were incubated with

horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (1;5,000;

cat. no. XD345904; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at 37˚C for 60

min. The immunoreactive bands were then detected using an Odyssey

CLX imaging system (LI-COR, Inc.), and Image Studio™

software (LI-COR, Inc.) was used to measure the OD of the

bands.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as the mean ± SD of at least

three independent experiments, and the data were analyzed with

GraphPad Prism (version 5.0; GraphPad; Dotmatics). For comparisons

involving three or more groups, a one-way ANOVA was conducted,

followed by Tukey's post-hoc test to assess significance. P<0.05

was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

Hcy may induce ferroptosis in EA.hy926

endothelial cells

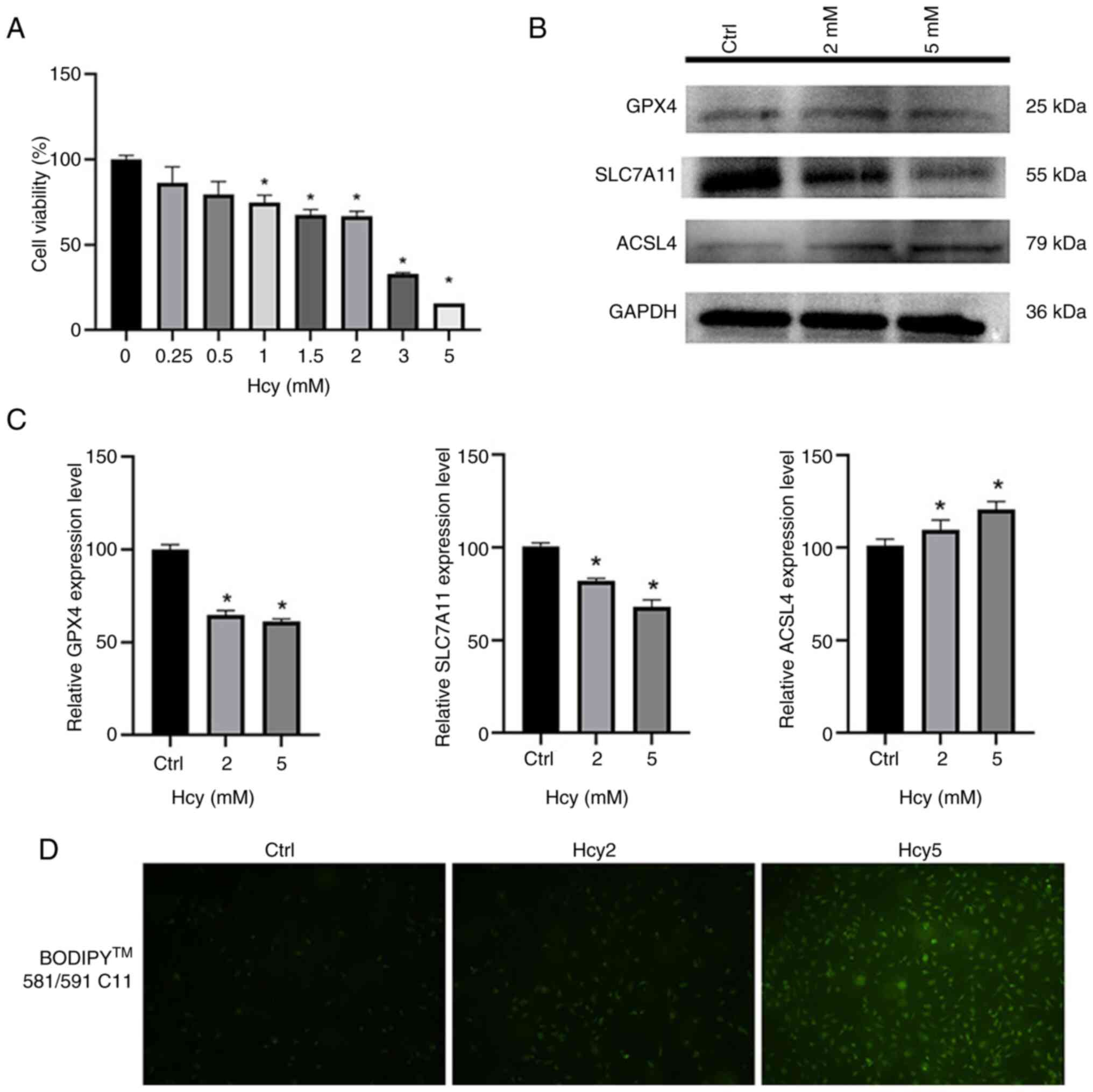

EA.hy926 cells were seeded into a 96-well plate and

treated with different concentrations of Hcy for 24 h. Results

indicated a gradual decrease in cell viability with increasing

concentrations of Hcy (Fig. 2A).

Subsequently, HCY were selected with a cell viability close to the

IC50 at a concentration of 2 mmol (cell viability, 60%)

and the lowest cell viability at 5 mmol (cell viability, 20%) for

the subsequent western blotting experiment. Western blotting was

conducted on cells treated with 2 or 5 mM Hcy for 24 h to detect

expression of the ferroptosis-related proteins GPX4, SLC7A11 and

ACSL4 (Fig. 2B) (32). Results demonstrated that the

expression levels of GPX4 and SLC7A11 decreased with increasing Hcy

concentration, while the expression levels of ACSL4 increased with

increasing Hcy concentration, potentially indicating an increase in

ferroptosis in EA.hy926 cells in response to increasing Hcy

concentration (Fig. 2C).

Furthermore, EA.hy926 cells treated with 2 or 5 mM Hcy for 24 h

were stained with the diluted BODIPY 581/591 C11 probe for lipid

peroxidation detection through inverted fluorescence microscopy

(Fig. 2D). With increasing Hcy

concentration, the intensity of green fluorescence within the cell

markedly increased, further suggesting that Hcy induces ferroptosis

in EA.hy926 cells.

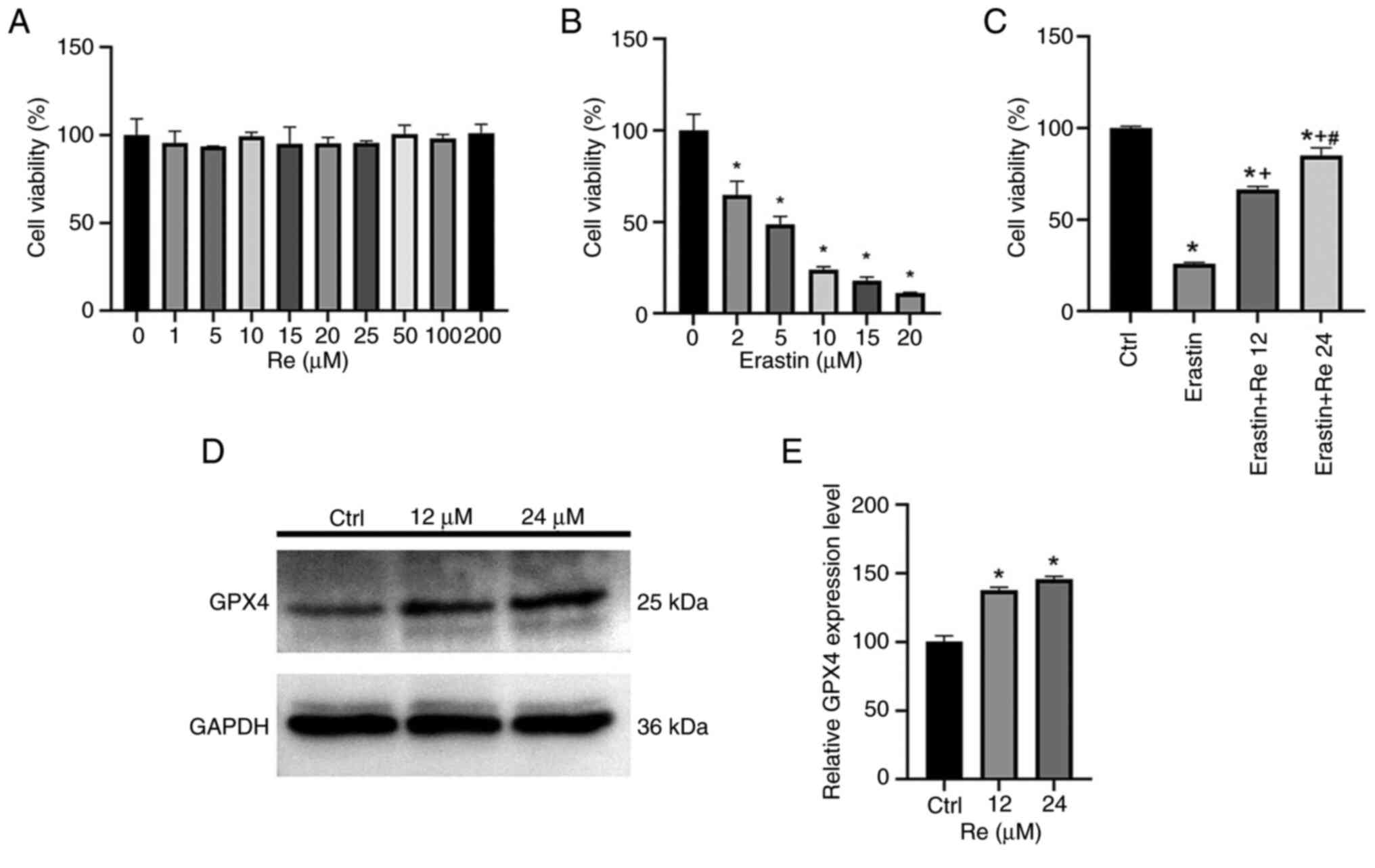

Ginsenoside Re may mitigate

erastin-induced ferroptosis in endothelial cells

To validate the impact of ginsenoside Re on cell

viability, different concentrations of ginsenoside Re were applied

to EA.hy926 cells for 24 h (Fig.

3A). Results indicated that ginsenoside Re had no significant

effect on EA.hy926 cell viability. Erastin, an activator of

ferroptosis, was used at various concentrations to treat EA.hy926

cells for 24 h, resulting in decreased cell viability with

increasing concentrations of erastin (Fig. 3B). Erastin at a drug concentration

of 5 µM with a cell viability of 50% was selected for subsequent

experiments. For the convenience of concentration calculation,

cells were treated with 12 µM or 24 µM of ginsenoside Re (Fig. 3C), with increasing concentrations

of ginsenoside Re notably improving cell viability. These findings

suggested that ginsenoside Re alleviated erastin-induced

endothelial cell ferroptosis in a dose-dependent manner. After

treatment with 12 or 24 µM ginsenoside Re for 24 h, western

blotting was performed (Fig. 3D

and E) and the results showed that

the expression level of GPX4 increased after the addition of

ginsenoside Re.

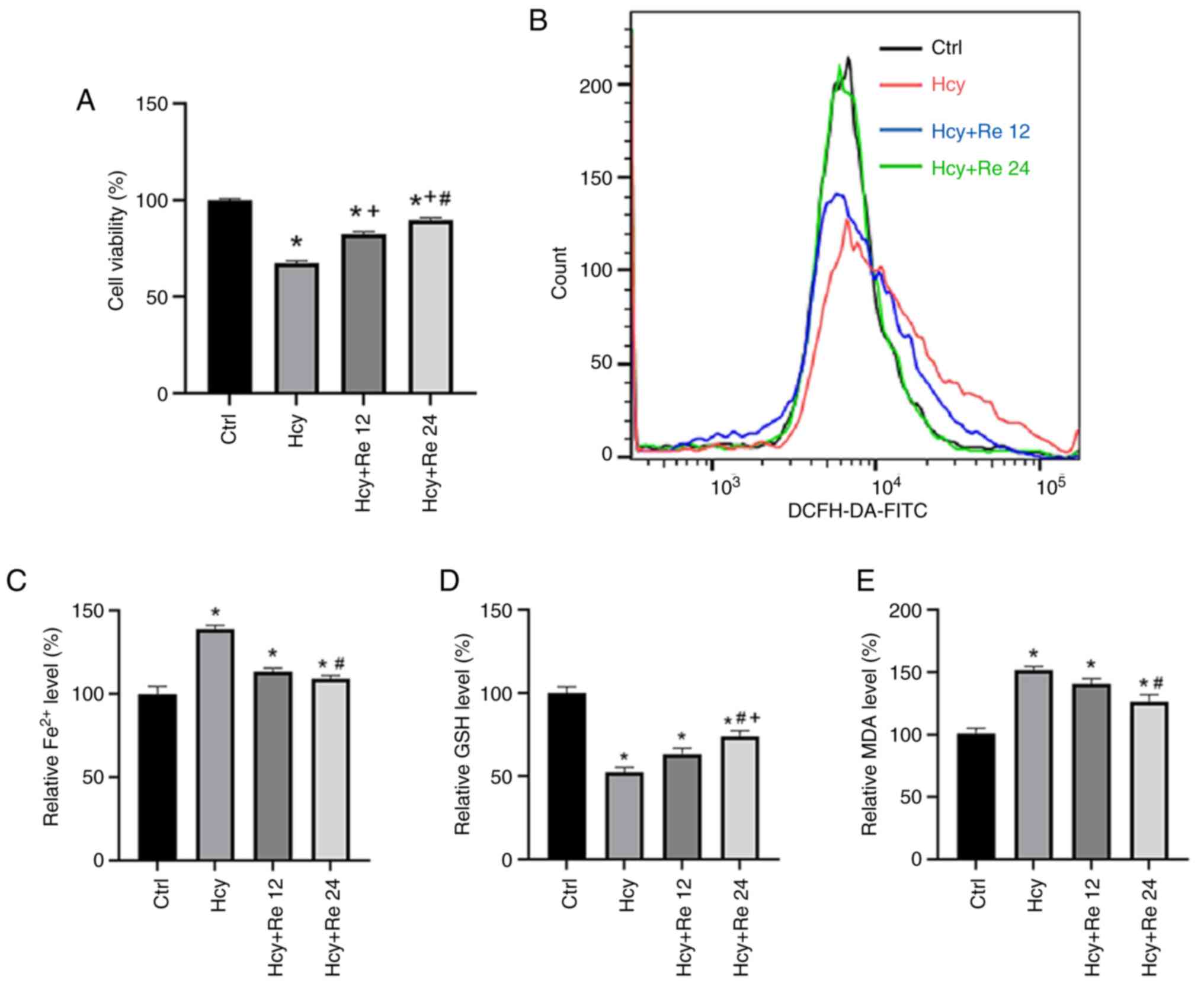

Ginsenoside Re may alleviate

Hcy-induced endothelial cell ferroptosis

To validate the impact of ginsenoside Re on the cell

damage caused by Hcy, EA.hy926 cells were treated with 2 mM Hcy and

with 12 or 24 µM ginsenoside Re. Results demonstrated that the

addition of ginsenoside Re could mitigate the cell damage caused by

Hcy, as the reduction in cell viability caused by Hcy was reversed

with increasing concentrations of ginsenoside Re (Fig. 4A). Intracellular ROS levels were

measured using FCM, which revealed an increase in ROS levels in the

Hcy-treated groups. Ginsenoside Re markedly reduced the increase in

ROS concentration induced by Hcy (Fig.

4B). Using a microplate reader, intracellular iron ion, GSH and

MDA levels were measured. Results revealed that Hcy could increase

the levels of Fe2+ and MDA, while decreasing GSH levels

in cells compared with those in the control group. By contrast,

ginsenoside Re decreased the levels of Fe2+ and MDA,

while increasing GSH levels compared with those in Hcy-treated

cells (Fig. 4C-E). These findings

suggested that ginsenoside Re alleviates Hcy-induced endothelial

cell ferroptosis.

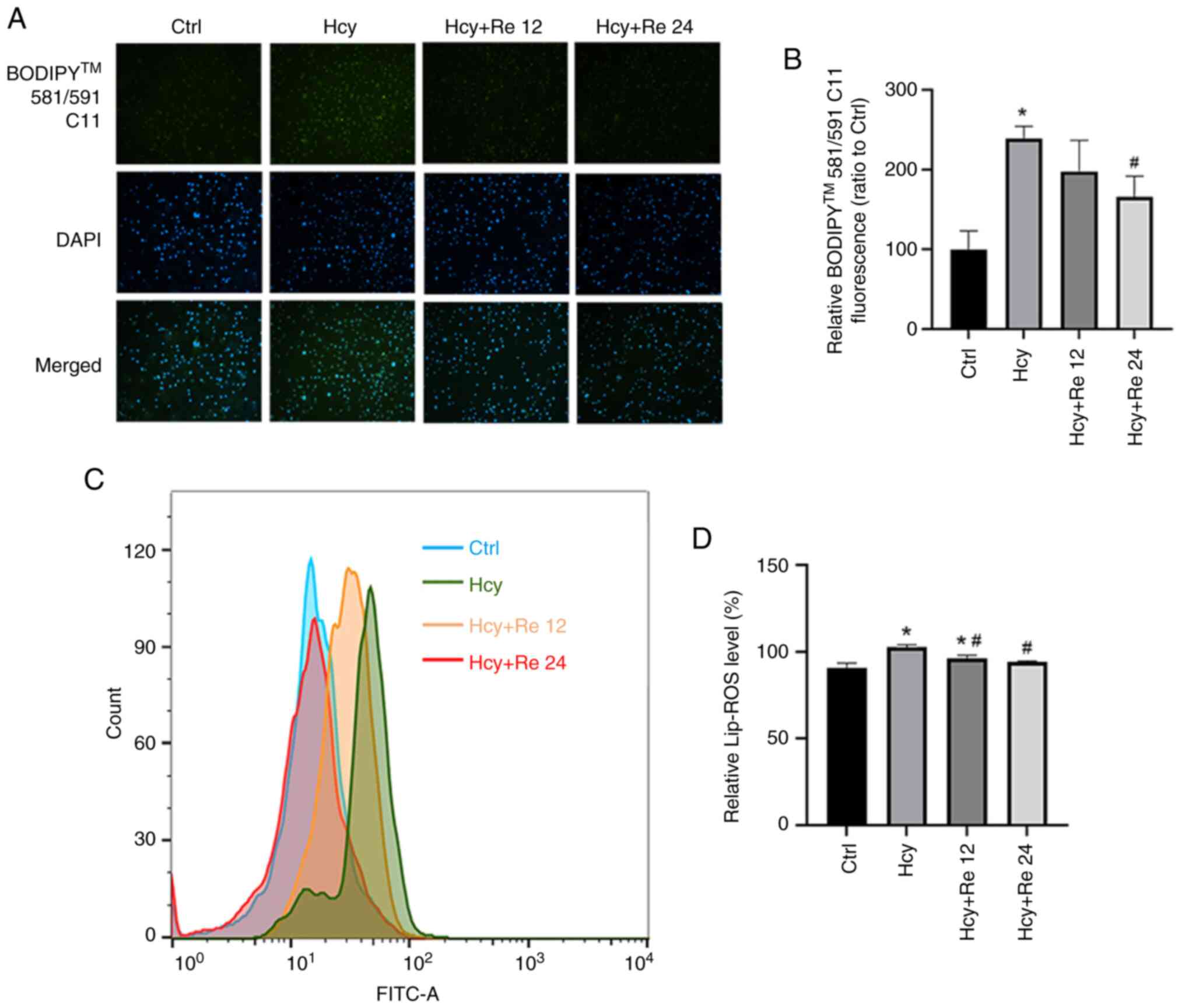

Effect of ginsenoside Re on Lip-ROS

levels in EA.hy926 cells

After EA.hy926 cells were treated with 2 mM Hcy and

either 12 or 24 µM ginsenoside Re, the BODIPY 581/591 C11 probe was

added for staining. Fluorescence microscopy and FCM were used to

measure the level of lipid peroxidation in cells. After Hcy

treatment, the fluorescence intensity of the cells increased,

whereas the fluorescence intensity decreased in the groups treated

with ginsenoside Re compared with that treated with Hcy alone.

These results indicate that Hcy increased the Lip-ROS level in the

cells, while a low dose of ginsenoside Re had no significant effect

on the Lip-ROS level in Hcy group cells. High-dose ginsenoside Re

reduced Lip-ROS levels (Fig. 5A

and B). Subsequently, it was shown

through flow cytometry that the Hcy group could increase the

intracellular Lip-ROS level, and the low-dose ginsenoside Re

(12) intervention could reduce

the reactive oxygen species level, but the rate was still higher

than that of the control group. The high-dose ginsenoside re group

(24) could reduce Lip-ROS levels

to normal levels (Fig. 5C and

D).

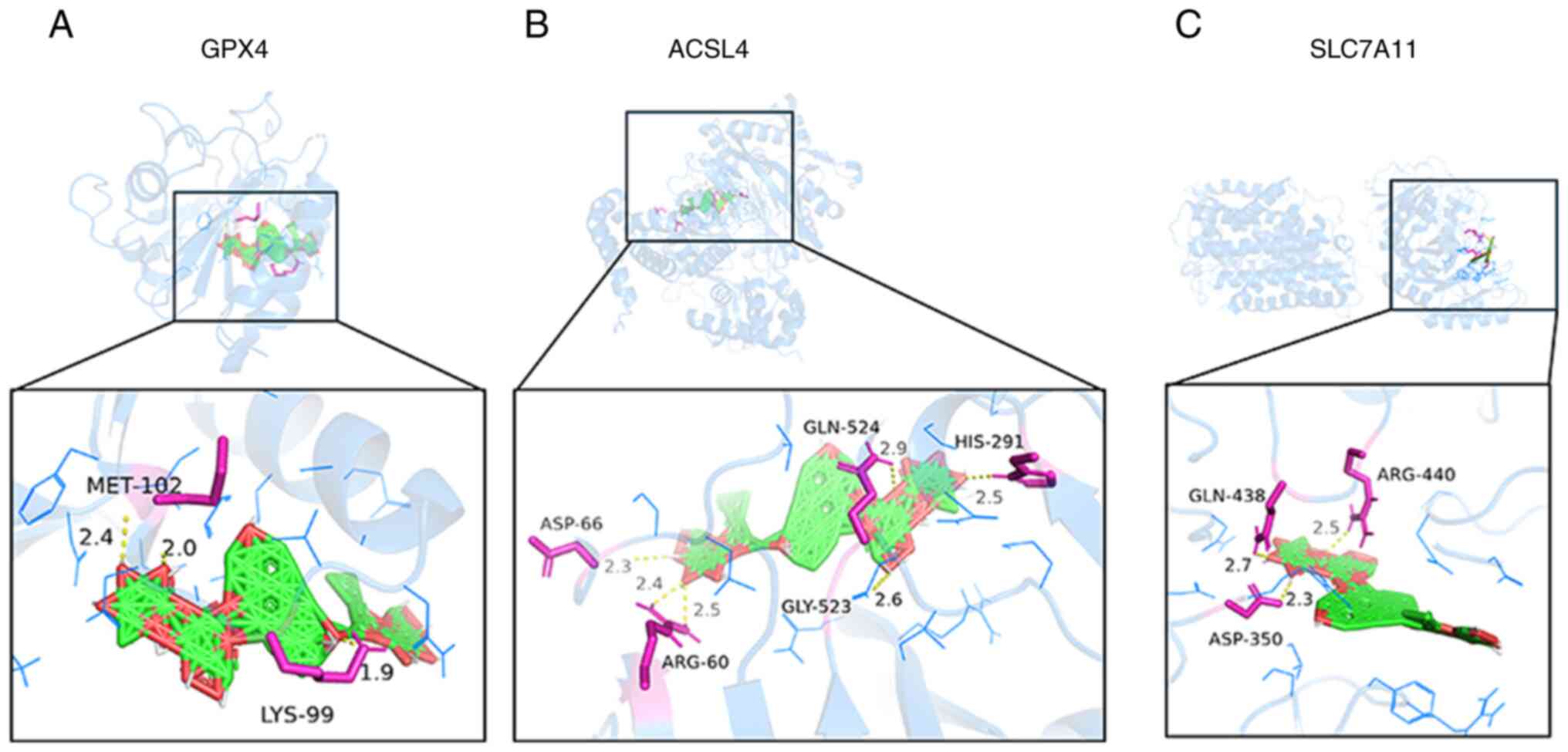

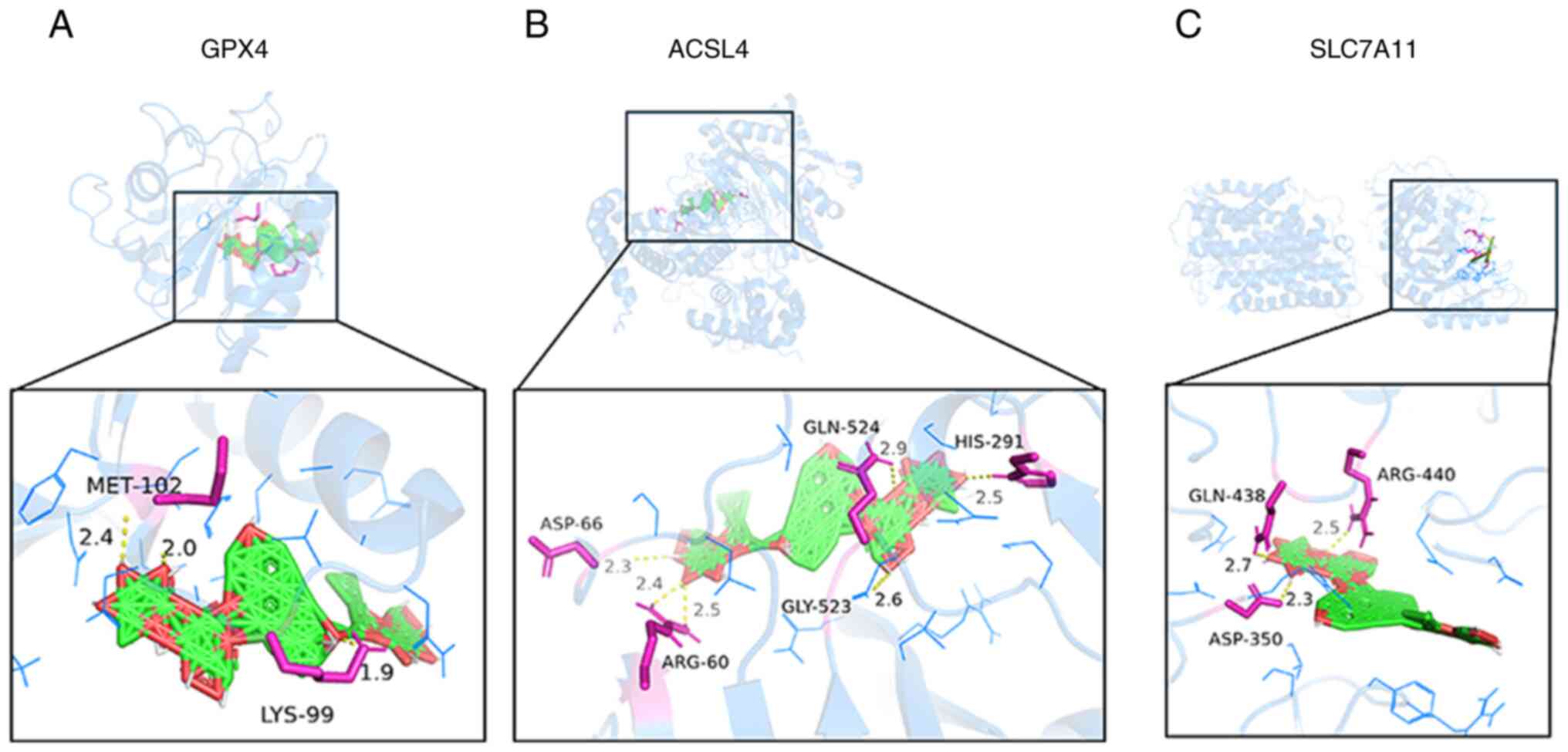

Association between ginsenoside Re and

the GPX4, SLC7A11 and ACSL4 antioxidant axis

To elucidate the mechanism by which ginsenoside Re

reduces ferroptosis in EA.hy926 cells, the effect of ginsenoside Re

on the GPX4, SLC7A11 and ACSL4 antioxidant axis in ferroptosis was

evaluated. Previous studies have reported that protein binding to

ligands is influenced by binding energies, with binding energies

<-5.0 kcal/mol indicating good binding and those <-7.0

kcal/mol indicating very firm binding (33,34).

Docking results showed that the binding energies of ginsenoside Re

with GPX4, SLC7A11 and ACSL4 were all <-7.0 kcal/mol (Table I). To more intuitively reflect the

combination of active ingredients and key targets, PyMOL was used

to visualize the results, revealing amino acid residues and the

combination of hydrogen bonding and active compounds. Therefore,

active components that bind strongly to target proteins were

selected for visualization (Fig.

6). The results revealed that ginsenoside Re binds to GPX4 on

amino acid residues methionine (MET)-102 and lysine (LYS)-99

(Fig. 6A), to ACSL4 on amino acid

residues aspartate (ASP)-66, arginine (ARG)-60, glycine (GLY)-523,

glutamine (GLN)-524 and histidine (HIS)-291 (Fig. 6B) and to SLC7A11 on amino acid

residues GLN-438, ASP-350 and ARG-440 (Fig. 6C). These findings suggested a

direct association between ginsenoside Re and the GPX4, SLC7A11 and

ACSL4 antioxidant axis.

| Figure 6Optimal docking map of ginsenoside Re

and key gene molecules. Ginsenoside Re can bind to (A) GPX4, (B)

ACSL4 and (C) SLC7A11. The yellow dotted line represents hydrogen

bonds, and the number beside the dotted line indicates the length

of the hydrogen bond in Ångströms. GPX4, glutathione peroxidase 4;

SLC7A11; solute carrier family 7 member 11; ACSL4, acyl-CoA

synthetase long-chain family member 4; MET, methionine; LYS,

lysine; ASP, aspartate; ARG, arginine; GLY, glycine; GLN,

glutamine; HIS, histidine. |

| Table IDocking analysis between ginsenoside

Re and target proteins. |

Table I

Docking analysis between ginsenoside

Re and target proteins.

| Compound | Key target | Protein Data Bank

ID | Binding energy

(kcal/mol) |

|---|

| Ginsenoside Re | GPX4 | 6HN3 | -12.8 |

| | SLC7A11 | 7EPZ | -13.1 |

| | ACSL4 | AF_AFO60488F1 | -12.8 |

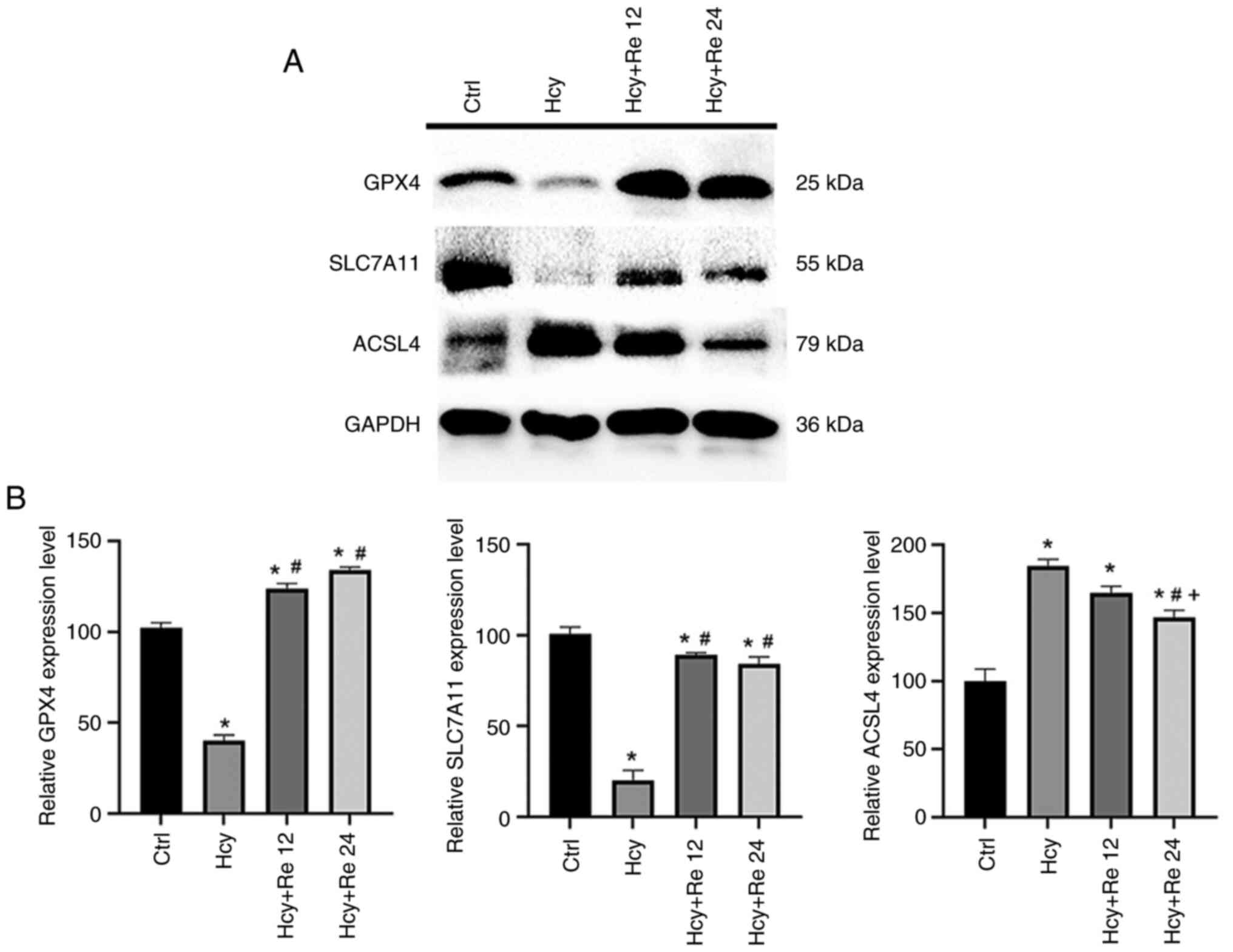

Impact of ginsenoside Re on the

expression of ferroptosis-related proteins induced by Hcy in

EA.hy926 cells

The present study indicated that after Hcy treatment

of cells, the expression levels of GPX4 and SLC7A11 proteins

decreased. After treating EA.hy926 cells with 12 and 24 µM

ginsenoside Re, it was found that the expression levels of GPX4 and

SLC7A11 increased compared with the Hcy alone group, indicating

that ginsenoside Re treatment could significantly increase the

expression level of ferroptosis protein induced by Hcy. The

ferroptosis protein marker ACSL4 was significantly increased in the

Hcy group, but significantly decreased in the ginsenoside Re

groups, thus suggesting that ginsenoside Re may alleviate

Hcy-induced endothelial cell ferroptosis (Fig. 7A and B). The present study demonstrated that

ginsenoside Re significantly increased the expression levels of

GPX4 in Hcy-treated EA.hy926 cells and therefore may mitigate

Hcy-induced ferroptosis in EA.hy926 cells. The results of this

study have clinical application value for the treatment of AS

caused by endothelial cell injury resulting from ferroptosis.

Discussion

Ferroptosis serves a key role in the progression of

AS, participating in various pathological processes, such as

endothelial cell damage, macrophage inflammation, foam cell

formation and vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and

migration (35-38),

making ferroptosis a novel target for AS research. Therefore,

exploring the relevant mechanisms of endothelial cell ferroptosis

and identifying effective intervention methods are key in the

treatment of AS.

Hcy is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular

disease. Increased levels of Hcy can damage endothelial cells,

leading to local infiltration of lipids and inflammatory cells and

the formation of foam cells and lipid streaks, which gradually

progress to atherosclerotic plaques (20,39).

In recent years, a number of studies have demonstrated the

involvement of ferroptosis in cell damage caused by Hcy; for

example, a study found that the protective properties of Fer-1

against KGN cell Hcy-induced injury were mediated by TET activity

and DNA demethylation (40). Wang

et al (41) reported that

Hcy may promote pulmonary microvascular endothelial cell

ferroptosis by upregulating ACSL4 and downregulating GPX4 and

ferroptosis suppressor protein 1 expression. The present study

showed that the expression levels of GPX4 and SLC7A11 were lower in

Hcy-treated EA.hy926 cells than those in the control group, while

the expression levels of ACSL4 and the levels of Lip-ROS were

greater than those in the control group. These results indicated

that Hcy could decrease the expression of GPX4 and SLC7A11,

potentially leading to increased Lip-ROS generation and therefore

endothelial cell ferroptosis.

It has been shown that ginsenoside Re can upregulate

the expression of GPX4 in cells through a process mediated by

phosphoinositide 3-kinase and extracellular signal-regulated

kinase, thereby alleviating oxidative stress-induced neuronal

damage (31). In a previous study,

10-50 µM ginsenoside Re alone was applied to SH-SY5Y cells for 9 h,

which markedly increased the expression levels of GPX4 in a

concentration-dependent manner (31). The present study showed that within

a certain concentration range (0-200 µM), ginsenoside Re had no

significant effect on cell viability. After treating EA.hy926 cells

with ginsenoside Re at concentrations of 12 and 24 µM for 24 h, the

expression levels of GPX4 were increased compared with those in the

control group. Ye et al (42) pretreated rats with 150 mg/kg

ginsenoside Re for 5 days, after which a myocardial

ischemia/reperfusion injury model was generated. This previous

study revealed that ginsenoside Re alleviated myocardial cell

ferroptosis induced by ischemia/reperfusion injury through microRNA

(miR)-144-3p and SLC7A11. These findings suggest that ginsenoside

Re may increase the expression levels of GPX4 and exert a

protective effect on ferroptosis in various cell types at

appropriate concentrations and treatment durations.

Since the discovery of ferroptosis, there has been a

focus on its two major regulatory mechanisms, namely the

disturbance in iron metabolism and lipid peroxidation. The Fenton

reaction refers to the process where Fe2+ reacts with

hydrogen peroxide to generate Fe3+ and oxygen radicals.

Excessive iron within cells can generate oxygen radicals and ROS

through the iron-dependent Fenton reaction, activating

iron-containing enzymes such as lipoxygenase, and leading to

oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation, thereby triggering

ferroptosis (43). In 2012, Dixon

et al (10) stimulated

HT1080 cells with erastin, which resulted in a marked increase in

intracellular iron ion and Lip-ROS levels. Notably, intervention

with iron chelators and lipid peroxidation inhibitors markedly

improved cell viability. Chen et al (44) established a ferroptosis model in

H9C2 cells by stimulating them with artemisinin for 24 h.

Fluorescence microscopy revealed marked increases in intracellular

ROS and Fe2+ levels as well as lipid peroxidation. By

contrast, SLC7A11 overexpression or miR-16-5p knockdown inhibits

ferroptosis and exhibits cardioprotective effects in vitro

and in vivo. The present study revealed that Hcy can lead to

a significant increase in the levels of ferroptosis related factors

Fe2+, MDA and ROS. However, after the intervention with

ginsenoside Re, the levels of Fe2+, ROS, Lip-ROS and MDA

were all lower than those in the Hcy group. These findings

suggested that ginsenoside Re treatment potentially reduced the

occurrence of the Fenton reaction, decreased cellular lipid

peroxidation levels and thereby alleviated Hcy-induced endothelial

cell ferroptosis.

Cystine/glutamate antiporter (system

xc-)/GPX4 is an important antioxidant system and one of

the central mechanisms underlying ferroptosis (45). System xc- consists of a

light chain subunit (xCT, also known as SLC7A11) and a heavy chain

(hc) subunit (CD98hc, also known as solute carrier family 3 member

2) located on the cell membrane (46). Extracellular cystine is absorbed

into cells in equimolar amounts and rapidly reduced to cysteine,

participating in the synthesis of the important intracellular free

radical scavenger GSH (47). GSH

is an essential antioxidant in cells that is synthesized by

cysteine synthase and GSH synthetase and is also a key

neurotransmitter and endogenous antioxidant in the body (48). System xc- participates

in the biosynthesis of GSH, and GSH, as an important cofactor of

GPX4, reduces intracellular oxygen levels. When system

xc- is inhibited by certain compounds (such as erastin),

GSH synthesis is decreased, leading to the inability of GPX4 to use

GSH to reduce lipid peroxides, resulting in ferroptosis. To

evaluate the extent to which ginsenoside Re binds

ferroptosis-related proteins, the present study performed molecular

docking experiments with GPX4, ACSL4, SLC7A11 and ginsenoside Re.

Results showed that ginsenoside Re tightly bound to the three

target proteins. Notably, the binding energies of ginsenoside Re to

GPX4, ACSL4 and SLC7A11 were all <-7.0 kcal/mol, indicating a

strong binding affinity. Molecular docking analysis of ginsenoside

Re with the ferroptosis-related proteins GPX4, ACSL4 and SLC7A11

revealed key interactions, suggesting their potential therapeutic

relevance. The interaction between ginsenoside Re and GPX4 at the

MET-102 and LYS-99 residues is particularly notable, as this

binding may stabilize GPX4, thereby enhancing its antioxidant

capacity and reducing iron-dependent lipid peroxidation (49). Similarly, the binding of

ginsenoside Re to ACSL4 at the residues ASP-66, ARG-60, GLY-523,

GLN-524 and HIS-291 suggests that ginsenoside Re may interfere with

ACSL4 function and inhibit its ferroptosis-promoting activity

(50). Moreover, the interaction

between ginsenoside Re and SLC7A11 at residues GLN-438, ASP-350 and

ARG-440 may enhance the stability of SLC7A11, which is a key

component of the system xc- pathway and serves a central

role in regulating ferroptosis (51). This hypothesis was verified by

western blotting and cellular GSH assays. GPX4 and SLC7A11

expression levels and intracellular GSH levels were significantly

decreased in the Hcy group. However, when compared with those in

the Hcy group, GPX4 and SLC7A11 expression levels and intracellular

GSH levels were significantly increased in the ginsenoside Re

intervention groups. The present study suggested that Hcy impaired

system xc-function and reduced GSH synthesis by decreasing SLC7A11

expression. By contrast, ginsenoside Re upregulated the expression

of GPX4, increased the synthesis of GSH and reduced

ferroptosis.

Ginsenoside Re has been shown to alleviate the

inhibitory effect of miR-144-3p on SLC7A11 expression, resulting in

the upregulation of SLC7A11. It was further confirmed that the

solute carrier family 7 member 11 (SLC7A11) was the target gene of

miR-144-3p by database analysis and western blotting (42). Specifically, miR-144-3p targets

SLC7A11 mRNA, suppressing its translation and stability. Through

modulation of miR-144-3p, ginsenoside Re indirectly enhances

SLC7A11 expression, promoting cystine uptake and GSH synthesis

(42). This cascade inhibits lipid

peroxidation associated with ferroptosis. Elevated SLC7A11 levels

increase GSH concentrations, which are key for the function of GPX4

as an antioxidant. Consequently, ginsenoside Re may indirectly

augment GPX4 activity through SLC7A11-dependent mechanisms

(42).

The pharmacokinetics and bioavailability of

ginsenoside Re are the key limiting factors to its clinical

application. The oral bioavailability of ginsenoside Re is

generally low, mainly due to its macromolecular structure and

hydrophilic properties, which lead to intestinal malabsorption,

rapid first-pass metabolism and enzyme-mediated degradation

(52). A study showed that the use

of ginsenoside Re complexes with polysaccharide protects

ginsenoside Re from degradation through hydrogen bonding and

regulates the expression of intestinal efflux proteins and tight

junction proteins, thereby enhancing absorption and bioavailability

(53). In animal experiments,

ginsenoside Re has demonstrated rapid absorption and a relatively

long elimination half-life. For example, after oral administration

of red ginseng extract, ginsenoside Re has been detected as a

20(S)-protopanaxatriol saponin in mouse plasma. The high plasma

protein binding and low hepatic distribution contribute to the

prolonged plasma circulation time observed with highly glycosylated

ginsenoside structures such as ginsenoside Re, which exhibits high

plasma exposure; however, tetra- or tri-glycosylated saponins

demonstrate greater accumulation susceptibility than ginsenoside

Re, highlighting its metabolic uniqueness (54).

In conclusion, the present study indicated that

ginsenoside Re may improve Hcy-induced ferroptosis in EA.hy926

cells by upregulating the expression of GPX4. Nevertheless, this

established cell model may not fully replicate the dynamic

functional adaptations characteristic of native endothelial cells

within atherosclerotic microenvironments. Future in vivo

studies are warranted to elucidate the therapeutic efficacy of

ginsenoside Re in inhibiting endothelial ferroptosis.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported by the Clinical

Research Fund project of Guangdong Medical Association (grant no.

A202302018), the Medical Science and Technology Research Foundation

of Guangdong Province (grant no. B2025385), the

‘Hundred-Thousand-Million Project’ for Science and Technology

Support in 2025 (grant no. 250623211606897) and the Social

Development Science and Technology Plan Project of Heyuan City

(grant no. 250609171604668).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

ShL, CZ, SY, SiL and SZ contributed to the

conception and design of the present study. SL, CZ and SL wrote the

manuscript and collected and analyzed the data. SL and SZ

critically revised the final manuscript. KY and SY interpreted the

data, and SL was responsible for capturing and organizing the

images. SL, CZ, SY, KY, SZ and SL confirm the authenticity of all

the raw data. All authors read and approved the final version of

the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Duan H, Zhang Q, Liu J, Li R, Wang D, Peng

W and Wu C: Suppression of apoptosis in vascular endothelial cell,

the promising way for natural medicines to treat atherosclerosis.

Pharmacol Res. 168(105599)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Qin X, Zhang J, Wang B, Xu G, Yang X, Zou

Z and Yu C: Ferritinophagy is involved in the zinc oxide

nanoparticles-induced ferroptosis of vascular endothelial cells.

Autophagy. 17:4266–4285. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Yang Z, Shi J, Chen L, Fu C, Shi D and Qu

H: Role of pyroptosis and ferroptosis in the progression of

atherosclerotic plaques. Front Cell Dev Biol.

10(811196)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Carlson BA, Tobe R, Yefremova E, Tsuji PA,

Hoffmann VJ, Schweizer U, Gladyshev VN, Hatfield DL and Conrad M:

Glutathione peroxidase 4 and vitamin E cooperatively prevent

hepatocellular degeneration. Redox Biol. 9:22–31. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Imai H and Nakagawa Y: Biological

significance of phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase

(PHGPx, GPx4) in mammalian cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 34:145–169.

2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Tang D, Chen X, Kang R and Kroemer G:

Ferroptosis: Molecular mechanisms and health implications. Cell

Res. 31:107–125. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Illés E, Patra SG, Marks V, Mizrahi A and

Meyerstein D: The Fe(II)(citrate) Fenton reaction under

physiological conditions. J Inorg Biochem.

206(111018)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Kist M and Vucic D: Cell death pathways:

Intricate connections and disease implications. EMBO J.

40(e106700)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Kagan VE, Mao G, Qu F, Angeli JP, Doll S,

Croix CS, Dar HH, Liu B, Tyurin VA, Ritov VB, et al: Oxidized

arachidonic and adrenic PEs navigate cells to ferroptosis. Nat Chem

Biol. 13:81–90. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Dixon SJ, Lemberg KM, Lamprecht MR, Skouta

R, Zaitsev EM, Gleason CE, Patel DN, Bauer AJ, Cantley AM, Yang WS,

et al: Ferroptosis: An iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell

death. Cell. 149:1060–1072. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Bai T, Li M, Liu Y, Qiao Z and Wang Z:

Inhibition of ferroptosis alleviates atherosclerosis through

attenuating lipid peroxidation and endothelial dysfunction in mouse

aortic endothelial cell. Free Radic Biol Med. 160:92–102.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Huang D, Zheng S, Liu Z, Zhu K, Zhi H and

Ma G: Machine learning revealed ferroptosis features and a novel

ferroptosis-based classification for diagnosis in acute myocardial

infarction. Front Genet. 13(813438)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Tang LJ, Zhou YJ, Xiong XM, Li NS, Zhang

JJ, Luo XJ and Peng J: Ubiquitin-specific protease 7 promotes

ferroptosis via activation of the p53/TfR1 pathway in the rat

hearts after ischemia/reperfusion. Free Radic Biol Med.

162:339–352. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Guo Y, Zhang W, Zhou X, Zhao S, Wang J,

Guo Y, Liao Y, Lu H, Liu J, Cai Y, et al: Roles of ferroptosis in

cardiovascular diseases. Front Cardiovasc Med.

9(911564)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Chen X, Xu S, Zhao C and Liu B: Role of

TLR4/NADPH oxidase 4 pathway in promoting cell death through

autophagy and ferroptosis during heart failure. Biochem Biophys Res

Commun. 516:37–43. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Stockwell BR, Friedmann Angeli JP, Bayir

H, Bush AI, Conrad M, Dixon SJ, Fulda S, Gascón S, Hatzios SK,

Kagan VE, et al: Ferroptosis: A regulated cell death nexus linking

metabolism, redox biology, and disease. Cell. 171:273–285.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Forcina GC and Dixon SJ: GPX4 at the

crossroads of lipid homeostasis and ferroptosis. Proteomics.

19(e1800311)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Shimada K, Skouta R, Kaplan A, Yang WS,

Hayano M, Dixon SJ, Brown LM, Valenzuela CA, Wolpaw AJ and

Stockwell BR: Global survey of cell death mechanisms reveals

metabolic regulation of ferroptosis. Nat Chem Biol. 12:497–503.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Dixon SJ, Patel DN, Welsch M, Skouta R,

Lee ED, Hayano M, Thomas AG, Gleason CE, Tatonetti NP, Slusher BS

and Stockwell BR: Pharmacological inhibition of cystine-glutamate

exchange induces endoplasmic reticulum stress and ferroptosis.

Elife. 3(e02523)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Kim J, Kim H, Roh H and Kwon Y: Causes of

hyperhomocysteinemia and its pathological significance. Arch Pharm

Res. 41:372–383. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Qin X, Xu M, Zhang Y, Li J, Xu X, Wang X,

Xu X and Huo Y: Effect of folic acid supplementation on the

progression of carotid intima-media thickness: A meta-analysis of

randomized controlled trials. Atherosclerosis. 222:307–313.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Esse R, Barroso M, Tavares de Almeida I

and Castro R: The contribution of homocysteine metabolism

disruption to endothelial dysfunction: State-of-the-art. Int J Mol

Sci. 20(867)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Zhang X, Huang Z, Xie Z, Chen Y, Zheng Z,

Wei X, Huang B, Shan Z, Liu J, Fan S, et al: Homocysteine induces

oxidative stress and ferroptosis of nucleus pulposus via enhancing

methylation of GPX4. Free Radic Biol Med. 160:552–565.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Mancuso C and Santangelo R: Panax ginseng

and Panax quinquefolius: From pharmacology to toxicology. Food Chem

Toxicol. 107:362–372. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Quan HY, Yuan HD, Jung MS, Ko SK, Park YG

and Chung SH: Ginsenoside Re lowers blood glucose and lipid levels

via activation of AMP-activated protein kinase in HepG2 cells and

high-fat diet fed mice. Int J Mol Med. 29:73–80. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Kim JM, Park CH, Park SK, Seung TW, Kang

JY, Ha JS, Lee DS, Lee U, Kim DO and Heo HJ: Ginsenoside Re

ameliorates brain insulin resistance and cognitive dysfunction in

high fat diet-induced C57BL/6 mice. J Agric Food Chem.

65:2719–2729. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Wang H, Lv J, Jiang N, Huang H, Wang Q and

Liu X: Ginsenoside Re protects against chronic restraint

stress-induced cognitive deficits through regulation of NLRP3 and

Nrf2 pathways in mice. Phytother Res. 35:2523–2535. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Su F, Xue Y, Wang Y, Zhang L, Chen W and

Hu S: Protective effect of ginsenosides Rg1 and Re on

lipopolysaccharide-induced sepsis by competitive binding to

Toll-like receptor 4. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 59:5654–5663.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Wang QW, Yu XF, Xu HL, Zhao XZ and Sui DY:

Ginsenoside Re improves isoproterenol-induced myocardial fibrosis

and heart failure in rats. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med.

2019(3714508)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Yao H, Li J, Song Y, Zhao H, Wei Z, Li X,

Jin Y, Yang B and Jiang J: Synthesis of ginsenoside Re-based carbon

dots applied for bioimaging and effective inhibition of cancer

cells. Int J Nanomedicine. 13:6249–6264. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Lee GH, Lee WJ, Hur J, Kim E, Lee HG and

Seo HG: Ginsenoside Re mitigates 6-hydroxydopamine-induced

oxidative stress through upregulation of GPX4. Molecules.

25(188)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Shi J, Chen D, Wang Z, Li S and Zhang S:

Homocysteine induces ferroptosis in endothelial cells through the

systemXc-/GPX4 signaling pathway. BMC Cardiovasc Disord.

23(316)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Yang R, Gao W, Wang Z, Jian H, Peng L, Yu

X, Xue P, Peng W, Li K and Zeng P: Polyphyllin I induced

ferroptosis to suppress the progression of hepatocellular carcinoma

through activation of the mitochondrial dysfunction via

Nrf2/HO-1/GPX4 axis. Phytomedicine. 122(155135)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Wu B, Lan X, Chen X, Wu Q, Yang Y and Wang

Y: Researching the molecular mechanisms of Taohong Siwu Decoction

in the treatment of varicocele-associated male infertility using

network pharmacology and molecular docking: A review. Medicine

(Baltimore). 102(e34476)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Gimbrone MA Jr and García-Cardeña G:

Endothelial cell dysfunction and the pathobiology of

atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 118:620–636. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Botts SR, Fish JE and Howe KL:

Dysfunctional vascular endothelium as a driver of atherosclerosis:

Emerging insights into pathogenesis and treatment. Front Pharmacol.

12(787541)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Mou Y, Wang J, Wu J, He D, Zhang C, Duan C

and Li B: Ferroptosis, a new form of cell death: Opportunities and

challenges in cancer. J Hematol Oncol. 12(34)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Ouyang S, You J, Zhi C, Li P, Lin X, Tan

X, Ma W, Li L and Xie W: Ferroptosis: The potential value target in

atherosclerosis. Cell Death Dis. 12(782)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Azad MAK, Huang P, Liu G, Ren W, Teklebrh

T, Yan W, Zhou X and Yin Y: Hyperhomocysteinemia and cardiovascular

disease in animal model. Amino Acids. 50:3–9. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Shi Q, Liu R and Chen L: Ferroptosis

inhibitor ferrostatin-1 alleviates homocysteine-induced ovarian

granulosa cell injury by regulating TET activity and DNA

methylation. Mol Med Rep. 25(130)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Wang Y, Kuang X, Yin Y, Han N, Chang L,

Wang H, Hou Y, Li H, Li Z, Liu Y, et al: Tongxinluo prevents

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease complicated with

atherosclerosis by inhibiting ferroptosis and protecting against

pulmonary microvascular barrier dysfunction. Biomed Pharmacother.

145(112367)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Ye J, Lyu TJ, Li LY, Liu Y, Zhang H, Wang

X, Xi X, Liu ZJ and Gao JQ: Ginsenoside Re attenuates myocardial

ischemia/reperfusion induced ferroptosis via miR-144-3p/SLC7A11.

Phytomedicine. 113(154681)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Yang WS, Kim KJ, Gaschler MM, Patel M,

Shchepinov MS and Stockwell BR: Peroxidation of polyunsaturated

fatty acids by lipoxygenases drives ferroptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci

USA. 113:E4966–E4975. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Chen Y, Deng Y, Chen L and Huang Z, Yan Y

and Huang Z: miR-16-5p regulates ferroptosis by targeting SLC7A11

in adriamycin-induced ferroptosis in cardiomyocytes. J Inflamm Res.

16:1077–1089. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Xu S, Wu B, Zhong B, Lin L, Ding Y, Jin X,

Huang Z, Lin M, Wu H and Xu D: Naringenin alleviates myocardial

ischemia/reperfusion injury by regulating the nuclear

factor-erythroid factor 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2)/System

xc-/glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) axis to inhibit ferroptosis.

Bioengineered. 12:10924–10934. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Zhang L, Liu W, Liu F, Wang Q, Song M, Yu

Q, Tang K, Teng T, Wu D, Wang X, et al: IMCA induces ferroptosis

mediated by SLC7A11 through the AMPK/mTOR pathway in colorectal

cancer. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2020(1675613)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Wang L, Liu Y, Du T, Yang H, Lei L, Guo M,

Ding HF, Zhang J, Wang H, Chen X and Yan C: ATF3 promotes

erastin-induced ferroptosis by suppressing system Xc. Cell Death

Differ. 27:662–675. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Parker JL, Deme JC, Kolokouris D, Kuteyi

G, Biggin PC, Lea SM and Newstead S: Molecular basis for redox

control by the human cystine/glutamate antiporter system xc. Nat

Commun. 12(7147)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Qiao O, Zhang L, Han L, Wang X, Li Z, Bao

F, Hao H, Hou Y, Duan X, Li N and Gong Y: Rosmarinic acid plus

deferasirox inhibits ferroptosis to alleviate crush

syndrome-related AKI via Nrf2/Keap1 pathway. Phytomedicine.

129(155700)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Ren S, Wang J, Dong Z, Li J, Ma Y, Yang Y,

Zhou T, Qiu T, Jiang L, Li Q, et al: Perfluorooctane sulfonate

induces ferroptosis-dependent non-alcoholic steatohepatitis via

autophagy-MCU-caused mitochondrial calcium overload and MCU-ACSL4

interaction. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 280(116553)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Wei XL, Yu AG, Zhang X, Pantopoulos K, Liu

ZB, Xu PC, Zheng H and Luo Z: Fe2O3

nanoparticles induce ferroptosis by binding to the N-terminus of

ACSL4 and suppressing its ubiquitin-mediated degradation. Free

Radic Biol Med. 238:123–136. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Cai J, Huang K, Han S, Chen R, Li Z, Chen

Y, Chen B, Li S, Xinhua L and Yao H: A comprehensive system review

of pharmacological effects and relative mechanisms of Ginsenoside

Re: Recent advances and future perspectives. Phytomedicine.

102(154119)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Zhu Y, Yue J, Yan R, Xia W, Li T and Fu X:

Enhancement in the intestinal absorption of ginsenoside Re by

ginseng polysaccharides and its mechanisms. Food Chem.

488(144914)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Jeon JH, Lee J, Choi MK and Song IS:

Pharmacokinetics of ginsenosides following repeated oral

administration of red ginseng extract significantly differ between

species of experimental animals. Arch Pharm Res. 43:1335–1346.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|