Introduction

Cervical cancer remains a major global health

burden, particularly in developing countries, with an estimated

604,000 new cases and 342,000 associated deaths worldwide in 2020,

according to the GLOBOCAN 2020 report (1). For early-stage disease, radical

hysterectomy remains a key part of curative treatment. However,

patients frequently experience substantial postoperative pain,

delayed gastrointestinal and physical recovery and an increased

rate of minor complications, all of which negatively affect their

quality of life and prolong hospitalization (2,3).

Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocols

have gained attention for improving perioperative outcomes through

multimodal interventions. These include preoperative education,

optimized analgesia, early feeding and mobilization strategies

(4). In previous years, ERAS has

been increasingly implemented in gynecologic oncology, with studies

showing its efficacy in reducing the length of hospital stays,

opioid use and postoperative complications (5,6).

Notably, a 2023 multicenter study by Nelson et al (7) demonstrated that ERAS pathways in

gynecologic malignancies were associated with faster bowel function

recovery and improved patient satisfaction, without increasing

adverse events.

However, numerous existing ERAS studies have

emphasized surgical or anesthetic optimization, with limited

attention given to the nursing-specific implementation and

adherence of ERAS elements. Successful ERAS implementation requires

high-fidelity bedside execution of core elements, structured pain

assessment with multimodal and non-pharmacologic analgesia, early

mobilization, nutrition and patient education, a number of which

are nursing-led within perioperative workflows (8-10).

In gynecologic surgery, higher adherence to these ERAS elements is

associated with fewer complications, shorter hospital stays and

reduced readmissions, underscoring the clinical impact of

nursing-driven compliance (11).

Furthermore, the evidence supporting ERAS-based perioperative

nursing in cervical cancer surgery remains sparse, especially in

retrospective real-world settings.

Therefore, the present study aimed to evaluate the

effectiveness of ERAS-based perioperative nursing care in reducing

postoperative pain, enhancing functional recovery and lowering

complication rates in patients with cervical cancer undergoing

radical hysterectomy. We hypothesized that structured nursing-led

ERAS protocols would lead to improved early postoperative outcomes

compared with conventional nursing care.

Materials and methods

Study design

The present retrospective comparative cohort study

was performed at The Affiliated Hospital of Southwest Medical

University (Luzhou, China). The present study evaluated patients

who underwent radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer between

January 2020 and December 2023. Based on the perioperative care

pathway received, patients were divided into an ERAS group and a

control group. Clinical, surgical and nursing data were obtained

from the hospital's electronic medical record and nursing

documentation systems. The ERAS protocol was officially implemented

at the institution in February 2022, allowing for natural

allocation of patients by implementation period. A complete-case

analysis was conducted to include all eligible patients with

complete perioperative data.

Participants

Female patients who underwent elective type II or

type III radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer between January

2020 and December 2023 were screened for eligibility. The inclusion

criteria comprised: i) Histologically confirmed cervical cancer;

ii) aged between 18-75 years; iii) American Society of

Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status classification I-III; and

iv) complete medical and nursing documentation, including

postoperative pain assessments (12). Exclusion criteria comprised: i)

History of chronic pain or psychiatric illness; ii) preoperative

opioid use; iii) emergency or palliative surgery; iv)

intraoperative conversion to an alternate procedure; and v)

readmission or reoperation within 7 days postoperatively. A

complete-case approach was used to maximize data

representativeness, resulting in a final cohort of 327 eligible

patients.

Perioperative nursing

intervention

Patients were categorized into two groups based on

the perioperative nursing protocol received. The ERAS group was

managed using a standardized institutional ERAS nursing pathway,

while the control group received conventional perioperative care.

The ERAS protocol included structured preoperative education and

counseling, shortened fasting time (clear fluids allowed up to 2 h

preoperatively), carbohydrate loading 2 h before surgery,

intraoperative normothermia maintenance, fluid restriction and

preventive multimodal analgesia with non-opioid agents.

Postoperative nursing strategies in the ERAS group focused on early

mobilization within 24 h, early oral intake, standardized pain

monitoring and non-pharmacological analgesia techniques such as

guided breathing, music therapy and psychological support. All ERAS

nurses received formal training and protocol adherence was

monitored using structured checklists, with ≥80% compliance defined

as adequate implementation. By contrast, the control group received

traditional nursing care, including prolonged preoperative fasting

(>8 h), routine opioid-based analgesia administered as needed,

delayed ambulation (>48 h postoperatively) and unstructured

patient education without standardized recovery goals.

Pain and outcome assessment

The primary outcome was postoperative pain

intensity, measured using the 10-point visual analog scale (VAS) at

6, 24 and 48 h after surgery (13). Pain assessments were part of

routine nursing care and were recorded by ward nurses. As nurses

were aware of perioperative practices (such as early mobilization

in the ERAS group), complete blinding was not feasible. However,

the use of a standardized VAS protocol helped to minimize

subjectivity. Additional pain-related outcomes included time to

first analgesia request, cumulative opioid consumption within 48 h

(converted to morphine-equivalent dose), use of patient-controlled

analgesia (PCA), use of non-opioid analgesics and application of

non-pharmacologic pain relief methods. Patient satisfaction with

pain control was assessed using a four-point Likert scale (1=very

dissatisfied; 4=very satisfied) and categorized for analysis as

‘satisfied’ (score ≥3) or ‘not satisfied’ (score <3). Secondary

outcomes included early functional recovery indicators comprising

the time to first ambulation (defined as time from arrival in the

ward to first standing or walking, assisted or unassisted), time to

first flatus, time to resume oral intake, time to urinary catheter

and analgesic pump removal and length of postoperative hospital

stay. Recovery of independent mobility was recorded as the number

of days post-surgery until walking without assistance.

Postoperative complications were recorded during hospitalization

and classified using the Clavien-Dindo grading system (14). Complication subtypes (fever,

urinary retention or wound infection) and 30-day hospital

readmissions were also recorded.

Data collection

Detailed demographic, surgical and clinical

variables were extracted from institutional electronic records,

including age, BMI, ASA physical status, International Federation

of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage, surgical method

(laparoscopic vs. open), surgical type (type II or III), operative

time and estimated blood loss. Comorbidities such as hypertension,

diabetes mellitus and cardiopulmonary disease were recorded, as

were lifestyle-related factors (such as smoking or alcohol use).

Laboratory parameters included preoperative hemoglobin and serum

albumin levels. Postoperative nursing records were used to capture

pain scores, analgesia use, recovery milestones (time to

ambulation, oral intake or catheter removal), complications and

discharge-related outcomes.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 26.0

(IBM Corp.). Normality of continuous variables was tested using the

Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Normally distributed variables were

presented as mean ± SD and compared using independent-sample

t-tests. Non-normally distributed variables were reported as median

and interquartile range and analyzed using Mann-Whitney U tests.

Categorical variables were summarized as counts and percentages and

compared using χ2 or Fisher's exact tests, as

appropriate. To identify independent predictors of pain intensity

at 24 h, a multivariable linear regression model was constructed.

Candidate variables included ERAS care, laparoscopic surgery, use

of PCA, use of non-pharmacologic analgesia, BMI, age, ASA class,

operative time, estimated blood loss and preoperative VAS pain

score. Prior to model fitting, collinearity diagnostics were

performed using variance inflation factor (VIF) and no variables

exceeded the conventional threshold (VIF <2 for all predictors).

The model's goodness of fit was evaluated using adjusted

R2 and the F-statistic. Two-tailed P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Baseline characteristics of the

present study population

A total of 327 patients undergoing radical surgery

for cervical cancer were included in the present analysis, with 162

assigned to the ERAS group and 165 to the control group (Table I). The two groups were well

balanced with regard to baseline demographic and clinical

characteristics. The mean age was 49.8±8.3 years in the ERAS group

and 50.5±8.1 years in the control group (P=0.368). BMI was

comparable between groups (23.4±3.2 vs. 23.1±3.4 kg/m², P=0.422).

Distribution of education level (P=0.289), ASA physical status

(P=0.733) and FIGO stage (P=0.648) showed no statistically

significant differences between groups. Laparoscopic surgery was

performed in 59.3% of patients in the ERAS group and 55.2% in the

control group (P=0.518), and the proportion of type III radical

hysterectomy was similar (27.8 vs. 29.1%; P=0.782). Operative time

(P=0.117), estimated blood loss (P=0.212), preoperative VAS pain

score (P=0.296), and the prevalence of comorbidities such as

hypertension (P=0.691) and diabetes mellitus (P=0.765) were

comparable. No significant differences were observed in smoking

(P=0.799), alcohol use (P=0.384), or laboratory parameters

including preoperative albumin (P=0.561) and hemoglobin (P=0.472).

Overall, there were no statistically significant differences in any

baseline characteristics between the two groups, indicating good

comparability prior to intervention.

| Table IBaseline characteristics of patients

with cervical cancer undergoing surgery in the ERAS and control

groups. |

Table I

Baseline characteristics of patients

with cervical cancer undergoing surgery in the ERAS and control

groups.

| Variable | ERAS group

(n=162) | Control group

(n=165) | P-value |

|---|

| Age, years | 49.8±8.3 | 50.5±8.1 | 0.368 |

| BMI,

kg/m2 | 23.4±3.2 | 23.1±3.4 | 0.422 |

| Education level | | | 0.289 |

|

Primary or

below | 18 (11.1) | 22 (13.3) | |

|

Secondary | 84 (51.9) | 90 (54.5) | |

|

Tertiary or

above | 60 (37.0) | 53 (32.1) | |

| ASA physical

status | | | 0.733 |

|

I | 68 (42.0) | 65 (39.4) | |

|

II | 81 (50.0) | 86 (52.1) | |

|

III | 13 (8.0) | 14 (8.5) | |

| FIGO stage | | | 0.648 |

|

IA-IB | 108 (66.7) | 104 (63.0) | |

|

IIA-IIB | 54 (33.3) | 61 (37.0) | |

| Surgical

approach | | | 0.518 |

|

Laparoscopic | 96 (59.3) | 91 (55.2) | |

|

Open | 66 (40.7) | 74 (44.8) | |

| Surgical type

III | 45 (27.8) | 48 (29.1) | 0.782 |

| Operative time,

min | 184.6±31.2 | 179.8±34.1 | 0.117 |

| Median estimated

blood loss, ml (IQR) | 200 (150-300) | 220 (160-320) | 0.212 |

| Preoperative VAS pain

score | 1.2±0.8 | 1.3±0.9 | 0.296 |

| Hypertension | 24 (14.8) | 27 (16.4) | 0.691 |

| Diabetes

mellitus | 16 (9.9) | 18 (10.9) | 0.765 |

| Cardiopulmonary

disease | 9 (5.6) | 13 (7.9) | 0.419 |

| Smoking history | 19 (11.7) | 21 (12.7) | 0.799 |

| Alcohol use | 17 (10.5) | 23 (13.9) | 0.384 |

| Preoperative albumin,

g/l | 42.1±3.8 | 41.9±3.5 | 0.561 |

| Hemoglobin, g/l | 125.2±10.9 | 124.5±11.3 | 0.472 |

Postoperative pain and analgesia

outcomes

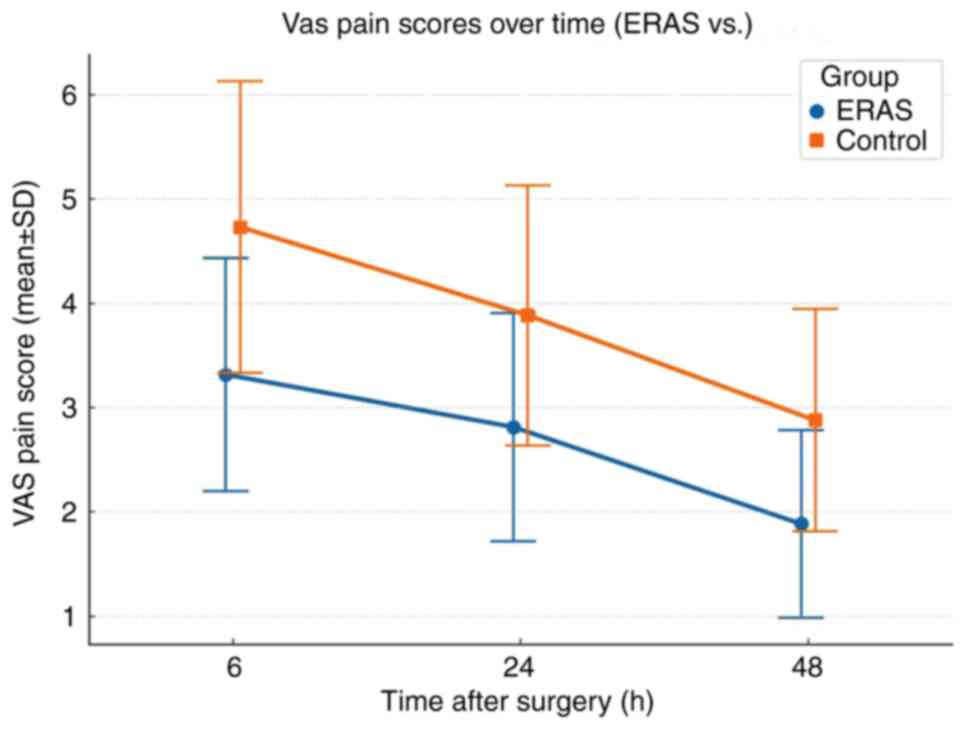

Postoperative pain intensity was significantly lower

in the ERAS group compared with the control group at all

postoperative time points (Table

II). At 6 h after surgery, the mean VAS score was 3.4±1.2 in

the ERAS group and 4.8±1.4 in the control group (P<0.001). This

difference remained significant at 24 h (2.7±1.1 vs. 3.9±1.3;

P<0.001) and 48 h (1.9±0.9 vs. 2.7±1.1; P<0.001). Although

both groups showed reductions in pain from 6 to 48 h

postoperatively, the magnitude of reduction was smaller in the ERAS

group (1.5±0.7 vs. 2.1±0.9; P=0.002), suggesting improved early

pain control. As shown in Table

II, patients in the ERAS group required significantly lower

cumulative opioid doses within the first 48 h postoperatively

(14.2±5.6 vs. 20.6±6.3 mg morphine equivalents; P<0.001).

Additionally, the proportion of patients requiring PCA was

significantly lower in the ERAS group (31.5%) compared with the

control group (58.8%; P<0.001). The use of non-opioid analgesics

(72.8 vs. 58.2%; P=0.005) and application of multimodal analgesia

strategies (51.9 vs. 28.5%; P<0.001) were significantly more

common among patients receiving ERAS-based care. Non-pharmacologic

interventions were also more frequently implemented in the ERAS

group, as summarized in Table II.

Methods such as guided breathing and music therapy were employed

with 42.6% of patients in the ERAS group compared with only 17.0%

in the control group (P<0.001). Furthermore, the time to first

analgesia request was longer in the ERAS group (3.9±1.4 h) compared

with in the control group (2.6±1.2 h; P<0.001), suggesting

improved pain tolerance. Notably, patient satisfaction with

postoperative pain management was significantly higher in the ERAS

group (82.7 vs. 58.2%; P<0.001). Together these results

indicated that the ERAS-based nursing pathway markedly improved

pain control, reduced reliance on opioids, encouraged multimodal

and non-pharmacologic pain strategies and enhanced patient

satisfaction during the early postoperative period in patients with

cervical cancer (Table II and

Fig. 1). In the present study, the

overall adherence rate to the ERAS nursing protocol was

approximately 86.4%, with no notable differences in compliance

across individual ERAS elements. Core components such as

preoperative counseling, shortened fasting, multimodal analgesia,

early mobilization, and early oral intake all demonstrated

adherence rates above 80%, indicating consistent application of key

protocol elements.

| Table IIComparison of postoperative

pain-related outcomes between ERAS and control groups. |

Table II

Comparison of postoperative

pain-related outcomes between ERAS and control groups.

| A, VAS pain scores

and dynamics |

|---|

| Variable | ERAS group

(n=162) | Control group

(n=165) | P-value |

|---|

| VAS score at 6

h | 3.4±1.2; [3

(3-4)] | 4.8±1.4; [5

(4-6)] | 0.000001 |

| VAS score at 24

h | 2.7±1.1; [3

(2-3)] | 3.9±1.3; [4

(3-5)] | 0.000003 |

| VAS score at 48

h | 1.9±0.9; [2

(1-2)] | 2.7±1.1; [3

(2-3)] | 0.000024 |

| VAS reduction 6-48

h | 1.5±0.7; [2

(1-2)] | 2.1±0.9; [2

(2-3)] | 0.002 |

| B, Analgesic use

and methods |

| Variable | ERAS group | Control group | P-value |

| Cumulative opioid

dose, mg | 14.2±5.6; [14

(10-18)] | 20.6±6.3; [20

(16-25)] | 0.000001 |

| Use of PCA

devices, | 51 (31.5) | 97 (58.8) | 0.000015 |

| Non-opioid

analgesics used | 118 (72.8) | 96 (58.2) | 0.005 |

| Multimodal

analgesia applied | 84 (51.9) | 47 (28.5) | 0.000038 |

| C,

Non-pharmacologic and satisfaction outcomes |

| Variable | ERAS group | Control group | P-value |

| Use of

non-pharmacological pain relief | 69 (42.6) | 28 (17.0) | 0.000004 |

| Time to first

request for analgesia, h | 3.9±1.4; [4

(3-5)] | 2.6±1.2; [3

(2-3)] | 0.000009 |

| Patient

satisfaction with pain management | 134 (82.7) | 96 (58.2) | 0.000003 |

Postoperative recovery and

complications

Patients in the ERAS group demonstrated

significantly faster postoperative recovery across multiple

indicators compared with those in the control group (Table III). The median time to first

ambulation was 18 h in the ERAS group compared with 27 h in the

control group (P<0.001), while time to first flatus and oral

intake were also reduced in the ERAS group (30 vs. 40 h and 17 vs.

31 h, respectively; both P<0.001). The removal of urinary

catheters and analgesic pumps occurred earlier in the ERAS group

(30.6±5.7 and 41.3±6.5 h) compared with the control group (39.1±6.2

and 53.8±8.4 h; both P<0.001). Overall, functional recovery was

improved in the ERAS group. The average time to independent walking

was 1.8±0.7 days in the ERAS group compared with 2.5±0.9 days in

the control group (P<0.001). Additionally, a higher proportion

of patients in the ERAS group were discharged without assistance

(88.9 vs. 71.5%; P<0.001). The median postoperative hospital

stay was significantly shorter in the ERAS group [5 (4-6)

days] compared with in the control group [7 (6-9)

days; P<0.001]. The overall incidence of postoperative

complications was lower in the ERAS group (8.0%) compared with the

control group (17.6%; P=0.009). Minor complications (Clavien-Dindo

grades I-II) were significantly reduced in the ERAS group (5.6 vs.

12.7%; P=0.031). There was no significant difference in the rate of

major complications (Clavien-Dindo grades III-IV) between groups

(P=0.283). Specific complications such as fever (P=0.065), urinary

retention (P=0.163) and wound infection (P=0.337) occurred less

frequently in the ERAS group, although the differences were not

statistically significant. The 30-day readmission rate was also

lower in the ERAS group (2.5 vs. 4.8%), but the difference did not

reach statistical significance (P=0.283). These findings suggested

that ERAS-based perioperative nursing markedly improved

postoperative functional recovery and reduced minor complications

in patients with cervical cancer undergoing surgery.

| Table IIIPostoperative recovery and

complications between ERAS and control groups. |

Table III

Postoperative recovery and

complications between ERAS and control groups.

| A, Early recovery

indicators |

|---|

| Variable | ERAS group

(n=162) | Control group

(n=165) | P-value |

|---|

| Time to first

ambulation, h | 18 (15-22) | 27 (23-34) | 0.000002 |

| Time to first

flatus, h | 30 (26-35) | 40 (34-46) | 0.000004 |

| Time to resume oral

intake, h | 17 (14-20) | 31 (25-36) | 0.000001 |

| Time to remove

urinary catheter, h | 30.6±5.7 | 39.1±6.2 | 0.000003 |

| Time to stop

analgesic pump, h | 41.3±6.5 | 53.8±8.4 | 0.000002 |

| B, Overall recovery

and discharge |

| Variable | ERAS group

(n=162) | Control group

(n=165) | P-value |

| Postoperative

hospital stay, days | 5 (4-6) | 7 (6-9) | 0.000001 |

| Time to independent

walking, days | 1.8±0.7 | 2.5±0.9 | 0.000006 |

| Discharged without

assistance, n (%) | 144 (88.9) | 118 (71.5) | 0.000013 |

| C, Postoperative

complications |

| Variable | ERAS group

(n=162) | Control group

(n=165) | P-value |

| Any complication, n

(%) | 13 (8.0) | 29 (17.6) | 0.009 |

| Clavien-Dindo grade

I-II, n (%) | 9 (5.6) | 21 (12.7) | 0.031 |

| Clavien-Dindo grade

III-IV, n (%) | 4 (2.5) | 8 (4.8) | 0.283 |

| Fever (>38.5˚C),

n (%) | 6 (3.7) | 14 (8.5) | 0.065 |

| Urinary retention,

n (%) | 4 (2.5) | 9 (5.5) | 0.163 |

| Wound infection, n

(%) | 3 (1.9%) | 6 (3.6) | 0.337 |

| 30-day readmission,

n (%) | 4 (2.5) | 8 (4.8) | 0.283 |

Factors associated with postoperative

pain at 24 h

Multivariate linear regression analysis identified

several independent predictors of VAS pain score at 24 h

postoperatively (Table IV).

ERAS-based nursing care was significantly associated with lower

pain scores (β=-1.05; 95%CI: -1.34 to -0.76; P<0.001). The use

of non-pharmacological analgesia methods also contributed to

reduced pain (β=-0.39; P=0.010), while the use of PCA was

associated with higher reported pain scores (β=0.51; P<0.001),

perhaps reflecting more severe discomfort requiring intervention.

Higher preoperative VAS scores (β=0.18; P=0.017), greater blood

loss (β=0.09 per 100 ml; P=0.032) and longer operative times

(β=0.05 per 10 min; P=0.021) were also positively associated with

increased postoperative pain. Laparoscopic surgery was

independently associated with lower pain scores compared with open

surgery (β=-0.46; P=0.006). Higher BMI was significantly associated

with increased pain scores (β=0.06; P=0.031), whereas age and ASA

class showed no significant associations. The overall model

demonstrated good fit and explanatory power (F=8.41; P<0.001;

adjusted R2=0.37), indicating that ERAS nursing and

intraoperative factors together accounted for a meaningful

proportion of variance in early postoperative pain. Collinearity

diagnostics confirmed no evidence of multicollinearity among

predictors (all VIF <2).

| Table IVMultivariate linear regression

analysis of factors associated with VAS pain score at 24 h

postoperatively (n=327). |

Table IV

Multivariate linear regression

analysis of factors associated with VAS pain score at 24 h

postoperatively (n=327).

| Variable | β coefficient | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|

| ERAS nursing care

(yes vs. no) | -1.05 | -1.34 to -0.76 | 0.000002 |

| Preoperative VAS

pain score | 0.18 | 0.03 to 0.33 | 0.017 |

| Use of PCA (yes vs.

no) | 0.51 | 0.23 to 0.80 | 0.000004 |

| Use of

non-pharmacological analgesia (yes vs. no) | -0.39 | -0.68 to -0.09 | 0.010 |

| Laparoscopic

surgery (vs. open) | -0.46 | -0.80 to -0.13 | 0.006 |

| Age (per 1 year

increase) | 0.01 | -0.01 to 0.03 | 0.264 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 0.06 | 0.01 to 0.11 | 0.031 |

| ASA class III (vs.

I-II) | 0.28 | -0.02 to 0.58 | 0.069 |

| Operative time (per

10 min increase) | 0.05 | 0.01 to 0.10 | 0.021 |

| Estimated blood

loss (per 100 ml increase) | 0.09 | 0.01 to 0.18 | 0.032 |

Discussion

The present retrospective cohort study provided

evidence to support the effectiveness of ERAS-based perioperative

nursing in enhancing postoperative outcomes among patients with

cervical cancer undergoing radical hysterectomy. Compared with

conventional care, patients managed under ERAS nursing protocols

reported significantly lower pain scores, faster recovery, reduced

opioid usage and fewer minor complications, all without increased

rates of major adverse events or readmission.

Effective pain management is a key part of

successful postoperative recovery. The present findings showed that

ERAS care significantly reduced pain intensity at 6, 24 and 48 h

postoperatively, aligning with previous ERAS studies in gynecologic

malignancies (15-17).

This improvement may be attributed to the integrated use of

multimodal analgesia, reduced opioid dependence and the increased

adoption of non-pharmacologic interventions, such as guided

breathing and music therapy. Multivariate regression analysis

confirmed ERAS nursing as an independent predictor of reduced VAS

pain score at 24 h. These findings highlight the key influence of

structured nursing-led protocols in optimizing early postoperative

pain trajectories.

In addition to superior pain control, patients in

the ERAS group achieved earlier mobilization, faster return of

gastrointestinal function and shorter hospitalization, objectives

that are key to ERAS (18,19). The present findings revealed that

patients in the ERAS group achieved earlier ambulation (median, 18

vs. 27 h) and oral intake (17 vs. 31 h), and a higher proportion

(88.9 vs. 71.5%) were discharged without assistance, reflecting

superior early functional recovery. This finding aligns with recent

prospective studies indicating that early ambulation after

abdominal or pelvic cancer surgery is associated with a reduced

risk of postoperative venous thromboembolism and paralytic ileus

(20,21). These benefits are plausibly

mediated by ERAS nursing components that promote early mobilization

and multimodal, opioid-sparing analgesia, which together reduce

opioid-related gastrointestinal hypomotility and facilitate earlier

activity and feeding (18-21).

Preoperative counseling and goal-setting may enhance patient

participation and adherence, supporting earlier independent

ambulation and discharge.

Notably, ERAS care was associated with a lower

incidence of Clavien-Dindo grade I-II complications. While the

reduction in major complications and readmission was not

statistically significant, the observed trends suggest a positive

clinical trajectory (22-24).

Consistent implementation of nursing-led elements, such as

optimized fluid management, active temperature maintenance and

structured postoperative monitoring, has been linked to fewer minor

infections and urinary complications in ERAS pathways, which is

concordant with the present study findings (8,11,22).

A key strength of the present study lies in its

nursing-centered focus. Numerous ERAS studies emphasize surgical

techniques or anesthetic interventions yet overlook the operational

role of nursing staff (25,26).

The present findings reinforced that the quality and consistency of

nursing practice were central to ERAS success. Trained nurses were

responsible not only for implementing daily care interventions, but

also for promoting patient education, protocol adherence and

recovery assessment, all factors shown to influence ERAS outcomes

across specialties (27).

However, several limitations warrant consideration.

First, the retrospective design inherently carries risks of

information and selection bias, even with statistical adjustments.

Second, the present study was conducted at a single academic

institution, which may limit generalizability, particularly in

settings lacking dedicated ERAS training programs. Third,

postoperative pain scores were documented by ward nurses as part of

routine clinical care. As the nurses were aware of perioperative

practices (including earlier ambulation and oral intake in the ERAS

group), true blinding was not feasible. This limitation raised the

possibility of detection bias, although the standardized use of the

VAS scale aimed to minimize subjectivity. Fourth, as allocation was

purely time-based (2020-2021 for conventional care and February

2022 onwards for ERAS) potential temporal confounding factors, such

as gradual refinements in surgical practice, evolving hospital

protocols and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic cannot be

completely excluded. This may have introduced a degree of detection

bias, although standardized use of the VAS scale was applied to

mitigate subjectivity. With this, patient-level factors such as

anxiety, depression and cultural attitudes toward pain, which are

known to influence postoperative outcomes, were not captured in

this analysis. Fifth, nursing compliance rates or ERAS fidelity

scores were not quantified, both of which are key metrics in ERAS

implementation science. Lastly, long-term functional outcomes,

patient-reported quality of life and cost-effectiveness were not

evaluated in the present study but remain important targets for

future prospective research.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that

ERAS-based perioperative nursing was associated with improved pain

management, faster recovery and lower minor complication rates in

cervical cancer surgery. These findings support the integration of

standardized nursing protocols within ERAS frameworks and

underscore the need for scalable, nurse-led ERAS models in

gynecologic oncology.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

LM contributed to the study design, data collection

and manuscript drafting. RL participated in data curation,

statistical analysis and interpretation of results. XW assisted

with patient screening, clinical data extraction and literature

review. ZX was responsible for coordinating clinical procedures and

quality control of perioperative data. ZW contributed to the

implementation of the ERAS nursing protocol and provided key

revisions to the manuscript. LC contributed to the conception and

design of the study, critically reviewed all data analyses for

methodological accuracy, guided the interpretation of findings and

revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. LM and

RL confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors have

read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was conducted in accordance with

the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics

Committee of The Affiliated Hospital of Southwest Medical

University (approval no. KY2025317). Due to the retrospective

nature of the present study and the use of anonymized patient data,

the requirement for informed consent was waived by the

committee.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Li DL, Li W and Chen ZJ: Enhanced recovery

after surgery in the perioperative period promotes recovery of

cervical cancer patients undergoing transabdominal radical

resection. Am J Transl Res. 17:230–238. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Benlolo S, Hanlon JG, Shirreff L, Lefebvre

G, Husslein H and Shore EM: Predictors of persistent postsurgical

pain after hysterectomy-A prospective cohort study. J Minim

Invasive Gynecol. 28:2036–2046.e1. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Ljungqvist O, Scott M and Fearon KC:

Enhanced recovery after surgery: A review. JAMA Surg. 152:292–298.

2017.

|

|

5

|

Bhandoria GP, Bhandarkar P, Ahuja V,

Maheshwari A, Sekhon RK, Gultekin M, Ayhan A, Demirkiran F,

Kahramanoglu I, Wan YL, et al: Enhanced recovery after surgery

(ERAS) in gynecologic oncology: An international survey of

peri-operative practice. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 30:1471–1478.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Bisch SP, Jago CA, Kalogera E, Ganshorn H,

Meyer LA, Ramirez PT, Dowdy SC and Nelson G: Outcomes of enhanced

recovery after surgery (ERAS) in gynecologic oncology-A systematic

review and meta-analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 161:46–55. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Nelson G, Fotopoulou C, Taylor J, Glaser

G, Bakkum-Gamez J, Meyer LA, Stone R, Mena G, Elias KM, Altman AD,

et al: Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS®) society

guidelines for gynecologic oncology: Addressing implementation

challenges-2023 update. Gynecol Oncol. 173:58–67. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Balfour A, Amery J, Burch J and

Smid-Nanninga H: Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS): Barriers

and solutions for nurses. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs.

9(100040)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Brown D and Xhaja A: Nursing perspectives

on enhanced recovery after surgery. Surg Clin North Am.

98:1211–1221. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Akbuğa GA and Yılmaz K: Obstacles to

compliance and implementation of ERAS protocol from nursing

perspective: A qualitative study. J Perianesth Nurs. 40:331–336.

2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Hayek J, Zorrilla-Vaca A, Meyer LA, Mena

G, Lasala J, Iniesta MD, Suki T, Huepenbecker S, Cain K,

Garcia-Lopez J and Ramirez PT: Patient outcomes and adherence to an

enhanced recovery pathway for open gynecologic surgery: A 6-year

single-center experience. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 32:1443–1449.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Mayhew D, Mendonca V and Murthy BVS: A

review of ASA physical status-historical perspectives and modern

developments. Anaesthesia. 74:373–379. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Myles PS, Myles DB, Galagher W, Boyd D,

Chew C, MacDonald N and Dennis A: Measuring acute postoperative

pain using the visual analog scale: The minimal clinically

important difference and patient acceptable symptom state. Br J

Anaesth. 118:424–429. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML,

Vauthey JN, Dindo D, Schulick RD, de Santibañes E, Pekolj J,

Slankamenac K, Bassi C, et al: The Clavien-Dindo classification of

surgical complications: Five-year experience. Ann Surg.

250:187–196. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Chao L, Lin E and Kho K: Enhanced recovery

after surgery in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery. Obstet

Gynecol Clin North Am. 49:381–395. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Asklid D, Ljungqvist O, Xu Y and

Gustafsson UO: Short-term outcome in robotic vs. laparoscopic and

open rectal tumor surgery within an ERAS protocol: A retrospective

cohort study from the Swedish ERAS database. Surg Endosc.

36:2006–2017. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Bogani G, Sarpietro G, Ferrandina G,

Gallotta V, DI Donato V, Ditto A, Pinelli C, Casarin J, Ghezzi F,

Scambia G and Raspagliesi F: Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS)

in gynecology oncology. Eur J Surg Oncol. 47:952–959.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Nelson G: Enhanced recovery in gynecologic

oncology surgery-state of the science. Curr Oncol Rep.

25:1097–1104. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Ding Y, Zhang X, Qiu J, Zhang J and Hua K:

Assessment of ESGO quality indicators in cervical cancer surgery: A

real-world study in a high-volume chinese hospital. Front Oncol.

12(802433)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Porserud A, Aly M, Nygren-Bonnier M and

Hagströmer M: Association between early mobilisation after

abdominal cancer surgery and postoperative complications. Eur J

Surg Oncol. 49(106943)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Egger EK, Merker F, Ralser DJ, Marinova M,

Vilz TO, Matthaei H, Hilbert T and Mustea A: Postoperative

paralytic ileus following debulking surgery in ovarian cancer

patients. Front Surg. 9(976497)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Tazreean R, Nelson G and Twomey R: Early

mobilization in enhanced recovery after surgery pathways: Current

evidence and recent advancements. J Comp Eff Res. 11:121–129.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Shen Y, Lv F, Min S, Wu G, Jin J, Gong Y,

Yu J, Qin P and Zhang Y: Impact of enhanced recovery after surgery

protocol compliance on patients' outcome in benign hysterectomy and

establishment of a predictive nomogram model. BMC Anesthesiol.

21(289)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Chen Y, Wan J, Zhu Z, Su C and Mei Z:

Embedding evidence of early postoperative off-bed activities and

rehabilitation in a real clinical setting in China: An interrupted

time-series study. BMC Nurs. 21(98)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Wainwright TW, Jakobsen DH and Kehlet H:

The current and future role of nurses within enhanced recovery

after surgery pathways. Br J Nurs. 31:656–659. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Peña CG: What makes a nurse a good ERAS

nurse? Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs. 9(100034)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Francis NK, Walker T, Carter F, Hübner M,

Balfour A, Jakobsen DH, Burch J, Wasylak T, Demartines N, Lobo DN,

et al: Consensus on training and implementation of enhanced

recovery after surgery: A delphi study. World J Surg. 42:1919–1928.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|