Introduction

Periodontal bone regeneration is a major clinical

challenge. Current surgical strategies, such as autologous bone

grafting combined with guided tissue regeneration, achieve

long-term success rates of ~58% in restoring functional attachment

(1-4).

These approaches are further constrained by donor site morbidity,

unpredictable graft resorption and diminished efficacy in patients

with systemic conditions such as diabetes mellitus (5-8).

Collectively, these limitations underscore the need for biological

therapies that directly modulate bone metabolism.

Sclerostin (Scl; encoded by the SOST gene) is a

22-kDa secreted glycoprotein that has emerged as a key regulator of

skeletal homeostasis, particularly in bone remodelling and

craniofacial biology. It serves as a key mediator of the

interaction between osteoblasts and osteoclasts, maintaining the

balance between bone formation and resorption (8). Mechanistically, Scl exerts its

effects through a number of interrelated pathways (9-12).

By antagonizing the canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling cascade, Scl

binds to low-density lipoprotein receptor-related proteins (LRPs)

including LRP5/6 on osteoblast precursors, thereby suppressing

osteoblast proliferation, differentiation and matrix

mineralization. This inhibition decreases the capacity for new bone

formation (13-15).

Scl indirectly promotes osteoclastogenesis through bone

morphogenetic protein (BMP)/Wnt signaling interactions. It

increases the receptor activator of NF-κB ligand (RANKL) to

osteoprotegerin (OPG) ratio by stimulating RANKL secretion from

osteocytes while decreasing OPG expression, favoring osteoclast

differentiation and activity. Thus, Scl not only limits bone

formation but also actively enhances bone resorption (16-19).

Beyond local effects in bone, Scl may also act

systemically. Evidence suggests (16,17)

that it can influence distant organs such as the kidney or vascular

system, linking bone metabolism to broader physiological processes.

In periodontal disease, these regulatory networks become

dysregulated. The alveolar bone undergoes rapid turnover and is

subject to continuous mechanical loading from mastication and

occlusal forces (16-18).

When combined with chronic biofilm-induced inflammation, these

stressors amplify disruption of the Scl-Wnt-RANKL axis,

accelerating alveolar bone resorption and undermining periodontal

tissue stability (19).

Given its dual role in suppressing osteoblast

activity and stimulating osteoclastogenesis, therapeutic inhibition

of Scl has attracted extensive research (14-19),

particularly following the clinical success of romosozumab in

osteoporosis. However, whether these benefits extend to

biofilm-driven periodontitis, remains uncertain. The regulatory

pathways by which Scl influences alveolar bone remodeling,

including inhibition of canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling,

modulation of the RANKL/OPG pathway, interactions with BMP

signaling and amplification through inflammatory cytokines are

illustrated in Fig. S1.

Research into therapeutic inhibition of Scl has

progressed since the approval of romosozumab for osteoporosis and

preclinical studies have confirmed its anabolic effects in

long-bone defect models (20-22).

Whether these effects extend to polymicrobial biofilm-induced

periodontitis remains unclear, given the unique challenges of the

periodontal environment, including alveolar bone turnover,

estimated to be 200-300% faster compared with that of tibial bone

(23-27),

constant bidirectional loading from mastication (28,29)

and chronic biofilm-driven inflammation (30,31).

To the best of our knowledge, the present

meta-analysis is the first to synthesize preclinical evidence on

Scl inhibition in experimental periodontitis. Existing studies

(14-19)

demonstrate limited insight into how treatment effects vary by

dose, anatomical site or systemic conditions. By integrating

available data, the present analysis aimed to outline the

dose-response association between SOST suppression and alveolar

regeneration, as well as potential differences across defect types

such as interproximal and furcation lesions and interactions with

systemic bone-modifying factors. Together, these findings may

provide a more comprehensive understanding of the therapeutic

potential of Scl inhibition in periodontal regeneration.

Materials and methods

Protocol and registration

The present protocol was registered on PROSPERO

(https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO;

registration ID: CRD42023388345). The present review aimed to

evaluate whether inhibition of Scl activity promotes alveolar bone

repair and regeneration in animal models of periodontal disease,

based on the recommendations from the Cochrane Handbook for

Systematic Reviews (32) and

PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analysis

(33).

Inclusion criteria

A population, intervention, comparison, outcomes and

study design framework was applied to define the criteria.

Inclusion criteria were as follows: i) Animal models of

experimental periodontal disease; ii) evaluated the inhibition or

neutralization of Scl activity; iii) used animal models with

periodontal disease but without Scl inhibition as the control

group; iv) encompassed primary outcomes associated with decreased

alveolar bone loss (ABL) and secondary outcomes including changes

in bone volume fraction (BVF), bone mineral density (BMD),

bone-specific serum markers and the number of SOST-positive cells;

and v) in vivo randomized controlled trials.

Exclusion criteria

Studies that did not replicate periodontal

pathology, in vitro experiments and studies lacking a

control group or using non-periodontitis animals as controls were

excluded.

Search strategy

Studies were identified through a systematic s earch

of the following electronic databases: PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), the Cochrane

Library (https://www.cochranelibrary.com/), Embase (https://www.embase.com/) and Web of Science (all

databases, https://www.webofscience.com/). Studies published from

inception to January 2025 were included, with no language

restrictions. The search combined medical subject headings with

free-text terms applied to titles, keywords and abstracts. In

addition, a manual search was performed by screening the reference

lists of articles and related reviews for additional relevant

studies. The complete search strategy is provided in Table SI.

Study selection

All retrieved records were imported into EndNote

software (version X9; Clarivate Plc) to remove duplicates. A total

of two reviewers then independently screened the remaining articles

against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. First, titles and

abstracts were reviewed to exclude irrelevant studies. Full text of

potentially eligible studies was assessed to confirm their

relevance. Any discrepancies were resolved by discussion and

consensus or consultation with a third reviewer.

Data extraction

Study publication date, author name, sample size,

animal species, the sex and diet of the animals, construction of

the periodontal disease model, the adopted interventions, route and

dose of administration, the duration of administration, outcomes

and types of detection (e.g., histological, radiographic or

molecular analyses) were collected.

If data were insufficient or presented only

graphically, attempts were made to contact the authors and obtain

the numerical values. If the information could not be retrieved,

WebPlotDigitizer (V5), a digital ruler software, was used to

measure graphical data (automeris.io/WebPlotDigitizer/) (34). If studies reported outcomes at

multiple time points, only data from the most commonly reported

time point across studies (e.g., 3 or 6 weeks) were acquired for

meta-analysis. If the experiments included a number of groups, only

periodontitis animal models were taken as the experimental and

control group for meta-analysis. The data were extracted

independently by two authors, with any disagreements being resolved

through discussion and consensus.

Quality assessment

Risk of bias was independently evaluated by two

reviewers using the Systematic Review Centre for Laboratory Animal

Experimentation (SYRCLE) risk of bias tool (35), which consists of ten domains

adapted from the Cochrane Collaboration tool (36). According to the criteria

recommended by Hooijmans et al (35), each domain was rated as low risk

(score=1) if sufficient methodological details were reported, high

risk (score=-1) if clear methodological shortcomings were present

or unclear risk (score=0) when information was insufficient to

permit judgement. The assessed domains included sequence

generation, baseline characteristics, allocation concealment,

random housing, blinding of caregivers/experimenters, random

outcome assessment, blinding of outcome assessors, incomplete

outcome data, selective outcome reporting and other potential

sources of bias. Discrepancies between reviewers were resolved by

discussion or consultation with a third reviewer.

Data synthesis and statistical

analysis

As only morphometric results, such as the distance

between the cementoenamel junction and alveolar bone crest

(CEJ-ABC), tissue mineral density (TMD) and BVF, yielded sufficient

data, these continuous variables were extracted for meta-analysis.

Analysis was conducted using REVMAN (version 5.3; The Cochrane

Collaboration) software to determine pooled effects. To identify

and measure heterogeneity in the results, χ2 tests and

I2 statistics were implemented. χ2 with a

significance level of α=0.1 was considered to indicate

heterogeneity.

As all outcome measures were continuous variables,

the standardized mean difference (SMD) with 95% CI was used to

describe the efficacy of the intervention effect. SMD was used

instead of weighted mean difference because the studies included

reported heterogeneous outcomes (BMD, BVF and ABL) in different

units and scales. The use of SMD allowed for standardization and

ensured comparability across studies. In accordance with the

Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, a

random-effects model was applied for all meta-analyses,

irrespective of the I2 value, since heterogeneity is

expected across experimental studies.

Subgroup analyses were conducted to explore

potential sources of heterogeneity, such as type of intervention

(direct vs. indirect inhibition), species, sex, dosage, route of

administration, model construction and whether the ligature was

removed (most models were ligature-induced). To minimize potential

bias from individual studies, sensitivity analysis was conducted by

sequentially excluding each trial to evaluate its influence on the

pooled results.

Level of evidence

A total of two investigators independently assessed

the certainty (level) of evidence for each outcome using the

Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation

(GRADE) system (GRADEPRO.org), based primarily on

five domains, including type of study design, risk of bias,

inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision and other comprehensive

consideration of sample size and confounding factors. Any

disagreements were resolved through discussion or by a third

researcher.

Results

Search outcomes

The literature search yielded a total of 99 studies

(Fig. S2). After removing the

duplicates and screening the remaining publications, 39 articles

were eligible for full-text evaluation. Of these, 31 were excluded.

A total of eight studies was retrieved for systematic review and

assessed by meta-analysis (37-44)

Study characteristics

The present review included articles published from

2013-2023. Although there were no restrictions on the type of

animal or publication language, all periodontal disease models

identified were rat or mouse studies published in English. The

number of animals ranged from 14-40, with a total of 119 males and

64 females [sex not reported in one study (41)]. Models included Sprague-Dawley rats

(37,38,42),

Wistar albino rats (44), inbred

F344 rats (39), OPG-deficient

mice (40) and periostin-knockout

mice (41). Diet primarily

comprised standard chow and tap water, except for the high-sugar

water provided to all groups by Chen et al (37) and the 10%

sucrose given to the experimental group by Yang et al

(43).

For interventions targeting Scl activity, Scl

antibody (Scl-Ab) was used in five studies (37,38,41,42,44),

SOST gene knockout was performed in two studies (41,43)

and specific pharmacological agents were tested in three studies,

namely caffeic acid phenethyl ester (CAPE) (44), low-dose doxycycline (LDD) (44), infliximab (39) and WP9QY (40).

In addition to ligature-induced periodontitis, five

studies also applied additional conditions unfavourable for bone

regeneration, such as ovariectomy (37,38),

periostin knockout (41), OPG

deficiency (40) and

streptozotocin-induced type I diabetes (37-41,43).

A total of one study used silk ligatures saturated with

Porphyromonas gingivalis (43).

Systemic subcutaneous injection of Scl-Ab was

employed in three studies (37,40,42),

while intraperitoneal injection was used in two studies (38,41).

The dosage and duration included 25 mg/kg twice weekly for 2-8

weeks in four studies (37,41,42,44)

and 5 mg/kg weekly for 22 weeks in one study (38). Local Scl-Ab application (125 µg)

was tested in one study (42) but

proved less effective compared with systemic administration. In

addition, Yiğit et al (44)

applied CAPE and LDD at 10 mg/kg for 14 days, delivered by

intraperitoneal injection and oral gavage, respectively. CAPE was

more effective compared with LDD at decreasing Scl expression. In

the other pharmacological studies, infliximab was administered

intraperitoneally at 5 mg/kg once or twice before euthanasia

(39) and WP9QY was given

subcutaneously at 10 mg/kg three times daily for 5 days (40).

The primary outcome assessment methods included

micro-computed tomography (CT) and histological examination to

evaluate ABL, BVF and BMD. Immunohistochemistry was used to assess

the number of SOST-positive cells and osteoclasts. In addition,

serum analysis, ELISA and reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

were performed to measure serum biomarkers, such as procollagen

type I N-terminal propeptide (P1NP), osteocalcin (OCN),

tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase 5b (TRAP5b), RANKL, C-terminal

telopeptide of type I collagen (CTx-1) and ALP. The characteristics

of the included studies are summarized in Table I.

| Table ICharacteristics of included

studies. |

Table I

Characteristics of included

studies.

| | First author,

year |

|---|

| Characteristic | Taut et al,

2013 | Ren et al,

2015 | Chen et al,

2015 | Hadaya et

al, 2019 | Yang et al,

2016 | Yiğit et al,

2022 | Kim et al,

2016 | Ozaki et al,

2017 |

|---|

| Sample size | 16 | 16 | 24 | 40 | 20 | 20 | 16 | 14 |

| Animal | SD rat | Periostin knockout

mouse | SD rat | SD rat | C57BL/6 mouse | Wistar albino

rat | Inbred F344

rat | OPG-/- C57BL/6

mouse |

| Sex | Male | N/A | Female | Female | Male | Male | Male | Male |

| Diet | Regular rodent chow

diet | N/A | Food and high-sugar

drinking water | Standard diet

NIH-31 modified | Standard solid

mouse chow, 10% sucrose for EX group and sterile water for CON

group | Standard rat food

and tap water ad libitum | Standard rat chow

and water ad libitum | Sterilized water

and diet ad libitum |

| Construction of

periodontal disease model | Ligature | Periostin

knockout | Ligature; OVX | Ligature; OVX | Ligature of silk

saturated with P.g | Ligature | Ligature;

streptozoto- cin | OPG deficiency |

| Intervention,

EX/CON | Scl-Ab/PBS | Scl-Ab, SOST and

periostin double knockout/ PBS | Scl-Ab/ empty

vehicle | Scl-Ab/empty

vehicle | SOST gene

knockout/none | CAPE; LDD/ PBS | Infliximab/

PBS | WP9QY/PBS |

| Route of

administration | s.c. | i.p. | s.c. | i.p. | N/A | CAPE, i.p.; LDD,

oral gavage | i.p. | s.c. |

| Dose | 25 mg/kg | 25 mg/kg | 25 mg/kg | 5 mg/kg Scl-ab | N/A | CAPE, 10 µmol/

kg/day; LDD, 10 mg/kg/day | 5 mg/kg | 10 mg/kg |

| Duration | Twice/week for 3 or

6 weeks | Twice/week for 8

weeks | Twice/week for 6

weeks | Weekly for 12 weeks

before OVX and 10 weeks after OVX | N/A (constructive

knockout); 2 months | Daily for 14

days | Once for the 3 day

group (on day 0); twice for the 20 day group (on days 7 and

14) | 3 times/day for 5

days |

| Secondary

outcomes | BVF, TMD. OCN,

P1NP, TRAP5b | Bone deposition

rate, mor- phological changes of osteocytes, BV/TV | TRAP5b, CTx-1, BVF,

BMD | P1NP, TRAP5b | OPG, RANKL, JNK,

p38MAPK, ERK1/2 | PNMLS, BMP2 and

Scl-positive expression | IL-1β, Scl,

cathepsin K-, RANKL- and Scl-positive cells | BV/TV; number of

TRAP-5b-, sterix- orScl- positive cells; serum ALP |

| Detection

technique | Bone-specific serum

biomar- kers; micro-CT; histology immunohisto- chemistry;

fluorescent calcian labeling | Electron

microscopy; micro-CT; histology/ immunohis- tochemistry; FITC

staining and Imaris analysis | Bone- specific

serum biomarkers; micro-CT; histology | Serum analysis;

micro-CT; histology | Immunohisto-

chemistry; micro- CT | Histomorpho- metry,

histopa- thology and immunohisto- chemistry | Histology,

histomorpho- logy and immunohisto chemistry; RT-PCR | Micro-CT;

histomorpho- logy and immunohisto- chemistry; ELISA (serum

marker) |

| (Refs.) | (42) | (41) | (37) | (38) | (43) | (44) | (39) | (40) |

Quantitative synthesis and data

analysis

The outcome variables with sufficient data,

including changes in the CEJ-ABC distance, ABL, BMD, BVF, number of

Scl-positive cells and bone-specific serum biomarkers such as OCN,

P1NP and TRAP5b, were pooled for further analysis (Table SII).

Primary outcomes. ABL

ABL was evaluated by measuring the linear distance

or volume between the CEJ and ABC before and after treatment. This

parameter directly reflects periodontal tissue changes as assessed

by histological or micro-CT examination. All studies (37-44)

reported quantitative changes in ABL, therefore this was used as

the primary outcome variable of the present meta-analysis.

Extracted data were expressed as linear distance, surface area or

volume.

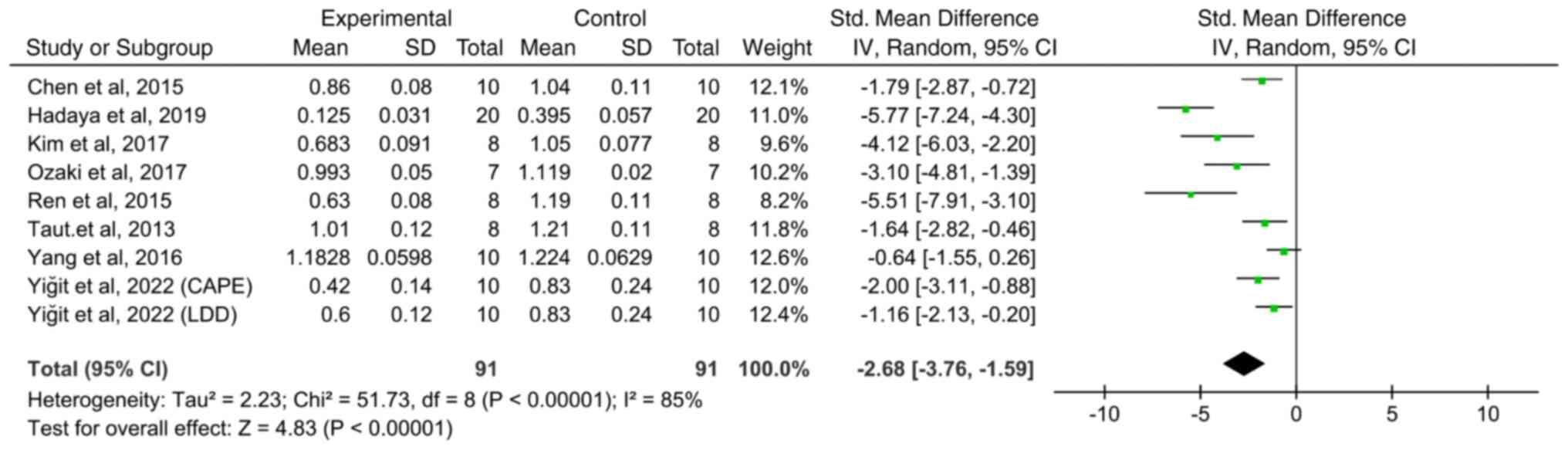

Pooled analysis revealed a significant decrease in

the CEJ-ABC distance in the Scl inhibition group compared with the

control group (Fig. 1; SMD: -2.68;

95% CI: -3.76 to -1.59; I2=85%; P<0.0001). In a study

by Yiğit et al (44), two

drugs (LDD and CAPE) with Scl-inhibiting potential were tested and

results were analysed separately. While numerous ABL data were

derived from micro-CT measurements, two studies employed

histological assessment (39,44),

resulting in different measurement units (linear distance, area or

volume).

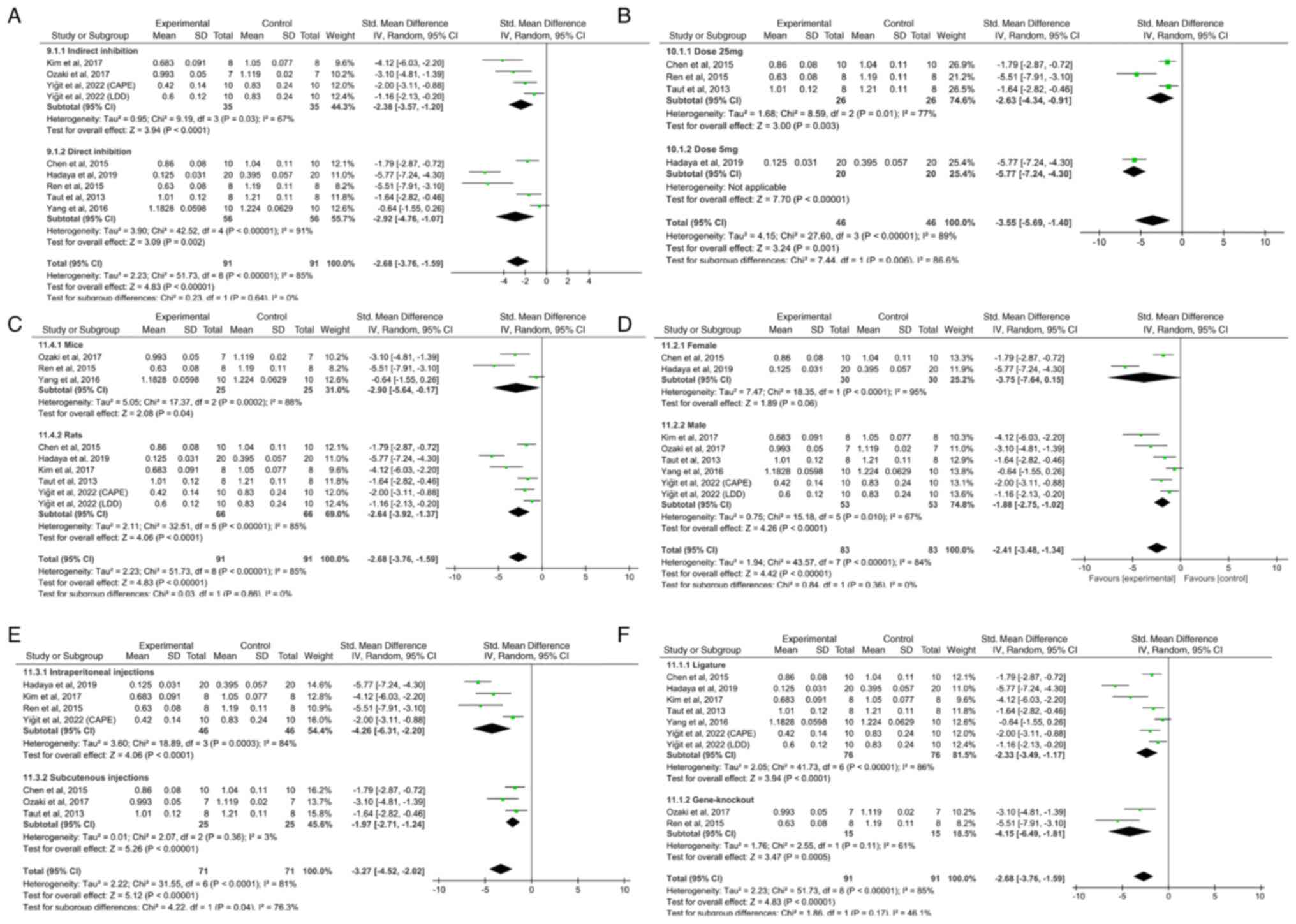

Subgroup analysis was performed according to

species, sex, dose, route of administration, type of Scl inhibition

and periodontitis model. With the exception of dose and route of

administration, no significant subgroup differences were observed

(Fig. 2). Low-dose (5 mg/kg;

Z=7.70) and subcutaneous (Z=5.26) treatments yielded improved

outcomes compared with high-dose (25 mg/kg; Z=3.00; P=0.006;

Fig. 2B) and intraperitoneal

(Z=4.06; P=0.04) treatments (Fig.

2E).

A number of studies used a therapeutic design

initiated after ligature removal (37,41-43).

Taut et al (42) also

incorporated a preventive arm, but no quantitative data were

reported and this subgroup could not be included in the present

meta-analysis. By contrast, Hadaya et al (38), in which ligatures were not removed

and chronic inflammation persisted during treatment, exhibited a

larger effect size compared with ligature-removed models (Fig. S3). These findings suggested that

sustained inflammation may modify the response to Scl inhibition

and decrease its net regenerative benefit.

Sensitivity analysis was conducted using a

leave-one-out approach. After sequentially removing each included

study, the pooled effect size and its 95% CI did not notably change

(Fig. S4). This indicated that no

single study had a decisive influence on the overall results,

supporting the validity of the present meta-analysis.

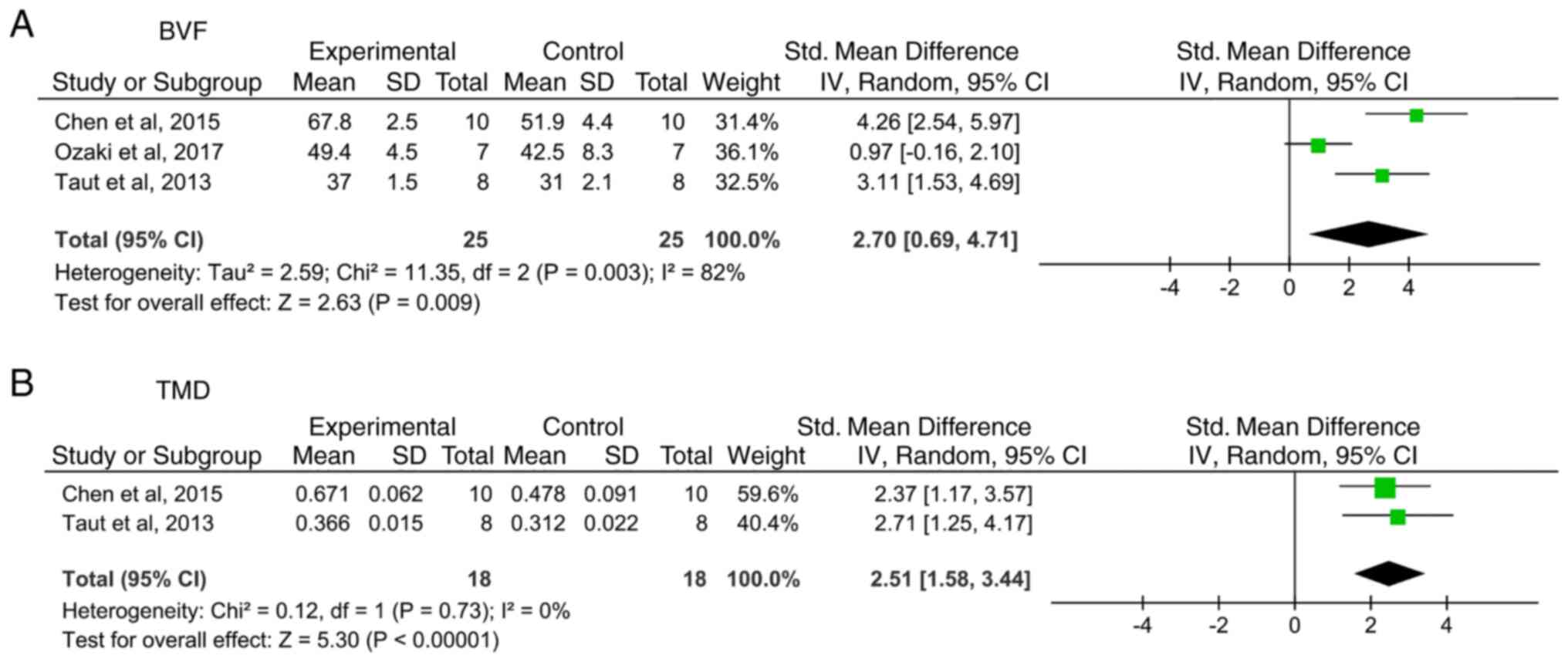

Secondary outcomes. BVF

BVF is a volumetric parameter calculated as the

ratio of BV to tissue volume based on micro-CT scanning. A total of

three studies (37,40,42)

reported the BVF and the newly formed bone area was significantly

larger in the experimental groups compared with the control groups

(Fig. 3A; SMD: 2.70; 95% CI:

0.69-4.71; I2=82%; P=0.009). In a study by Taut et al

(42), both systemic and local administration were tested, but

only systemic data were extracted for meta-analysis to ensure

consistency.

BMD/TMD. A total of two studies (37,42)

reported BMD/TMD and revealed that compared with control treatment,

systemic Scl-Ab treatment significantly increased BMD (Fig. 3B; SMD: 2.51; 95% CI: 1.58-3.44;

I2=0%; P<0.00001).

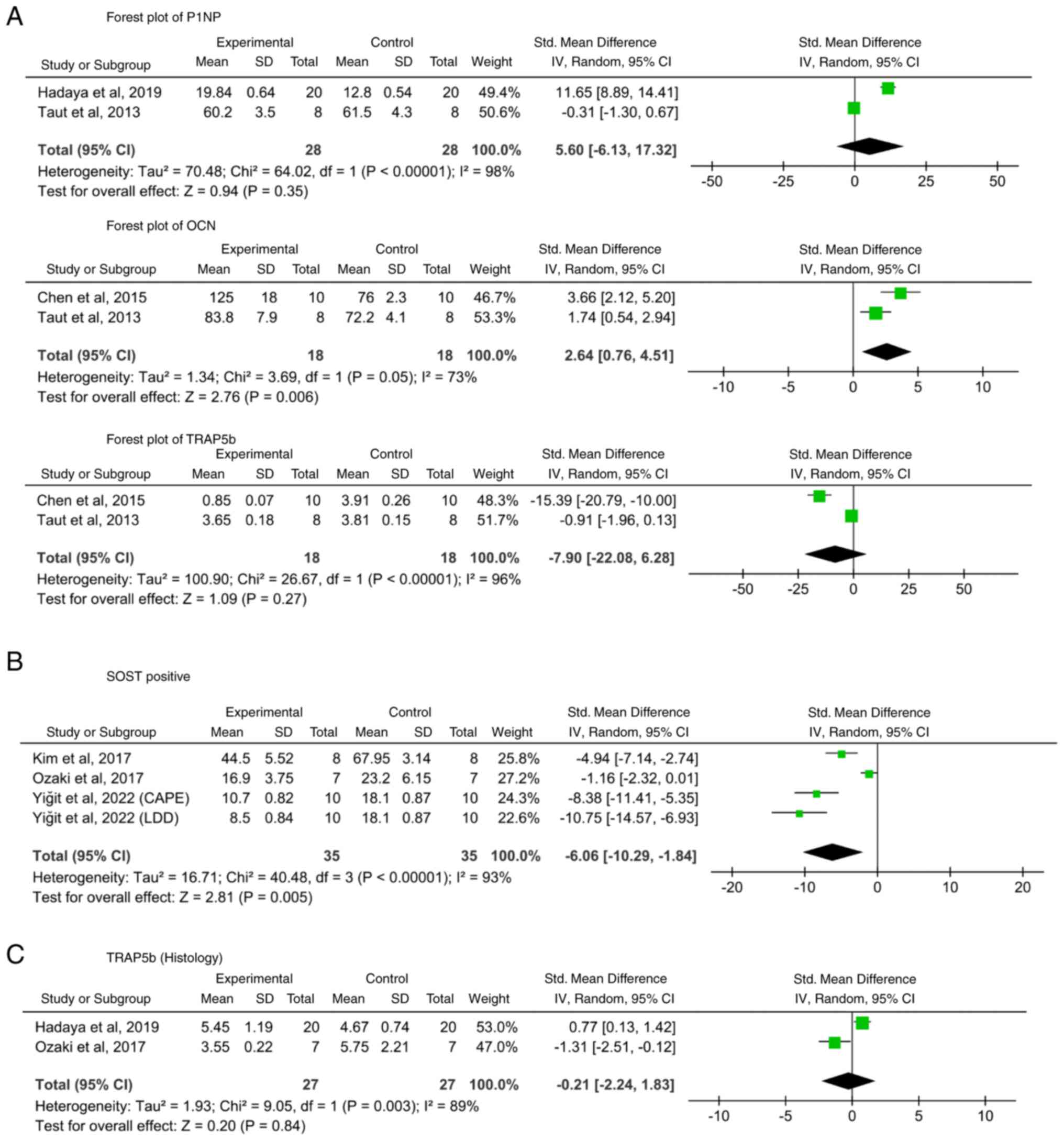

Other bone-specific serum biomarkers.

Bone-associated serum markers (P1NP, OCN, OPG, RANKL, TRAP5b, CTx-1

and ALP) were evaluated in four studies (37,38,42,43).

Except for OCN in two studies (37,42),

no significant pooled results were obtained (Fig. 4A). Hadaya et al (38) reported that P1NP levels were

notably higher in the Scl-Ab group at 6 and 12 weeks

post-ovariectomy but decreased below baseline at the end of

treatment (38). Taut et al

(42) reported that OCN levels

were notably elevated in the Scl-Ab group at 3 and 6 weeks. P1NP

was also notably higher at 3 but not at 6 weeks (42). Chen et al (37) observed marked increases in OCN and

OPG in the experimental group after 6 weeks, accompanied by

decreases in TRAP5b and CTx-1(37). Ozaki et al (40) reported that WP9QY did not reduce

ALP levels in OPG-deficient mice but increased osteoblast

differentiation in the M1 interradicular septum.

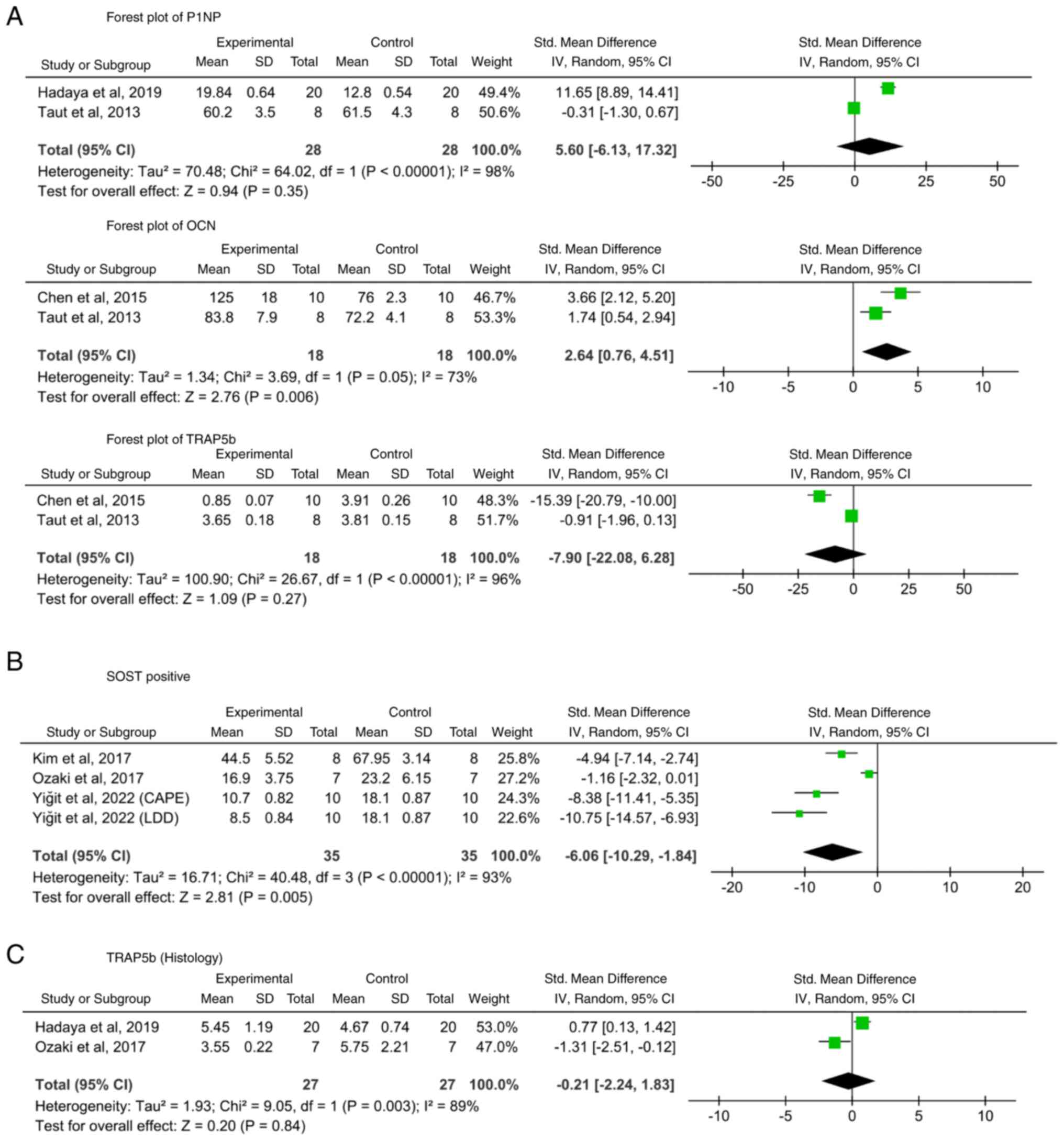

| Figure 4Forest plots of bone-specific

biomarkers and SOST-positive cells. (A) Bone-specific serum

biomarkers (P1NP, OCN and TRAP5b). (B) Histological test for

TRAP5b. (C) SOST-positive cells. Scl, sclerostin; df, degrees of

freedom; LDD, low-dose doxycycline; CAPE, caffeic acid phenethyl

ester; SMD, standardized mean difference; TRAP5b,

tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase 5b; SOST, sclerostin; IV,

Inverse Variance Model; Pp1NP, procollagen type I N-terminal

propeptide; OCN, osteocalcin; TRAP5b, tartrate-resistant acid

phosphatase 5b. Supplementary figure legends |

For serum TRAP5b, no notable differences were

observed between the groups. The detection methods varied: Two

studies (37,42) assessed TRAP5b expression through

Scl-associated assays, while two others (38,40)

used histological staining to quantify the number of

osteoclasts/unit area (Fig. 4C).

Although Taut et al (42)

concluded that Scl inhibition had no effect on TRAP5b expression,

the remaining studies indicated that Scl-Ab therapy decreased

TRAP5b expression, which was consistent with increases in the

expression of other osteogenic markers.

Number or ratio of SOST-positive cells. A

total of three studies (39,40,44)

using specific drugs assessed SOST-positive cells, consistently

showing that the number of Scl-positive cells increased

significantly in untreated periodontitis models but decreased

markedly after treatment (Fig. 4B;

SMD: -6.06, 95% CI: -10.29 to -1.84; I2=93%;

P=0.005).

Risk of bias. The risk of bias across ten

domains was assessed using SYRCLE (Table SIII). Overall, the methodological

quality of the included studies was moderate, with a number of

domains judged as unclear or high risk. Adequate sequence

generation was reported in 1/8 studies, while baseline

characteristics were comparable in 7/8 (37-41,43,44).

Allocation concealment was not described in any report and

therefore was rated as high risk across all the studies. Random

housing and outcome assessments were not reported in any study,

resulting in universally unclear ratings. A total of three studies

(37,38,44)

described the blinding of experimenters and the blinding of outcome

assessors. By contrast, incomplete outcome data were adequately

addressed in all studies and selective outcome reporting was judged

as low risk in 7/8 (37-41,43,44).

Other sources of bias were consistently rated as low risk.

Collectively, these findings indicated that although the internal

validity of the included studies was limited by insufficient

reporting of randomization, housing and blinding, the risk of

attrition and reporting bias was generally low.

Level of evidence. Level of evidence for

SOST-positive cells, ABL and related subgroups was determined to be

moderate. However, the levels of evidence for TMD, BVF, OCN, P1NP

and TRAP5b were lower (Table

SIV). The decrease in the level of evidence was primarily due

to inconsistency and imprecision or less overlap in CI, small

P-values for the heterogeneity test, large I2 value and

failure to perform sensitivity analyses. None of the included

studies reported osteonecrosis or other adverse events associated

with sclerostin inhibition

Discussion

The present analysis highlighted the potential of

Scl inhibition in mitigating ABL and promoting osteogenesis in

experimental periodontitis models (37,38,41-43).

The mechanisms underlying these effects are complex but may involve

key pathways including Wnt/β-catenin signaling, which regulates

osteoblast differentiation and bone formation (13-15,41,43).

In addition, Scl inhibition may act via the RANKL/OPG pathway,

thereby balancing osteoclast activity and limiting excessive bone

resorption (16,37,40,42).

The decrease in the number of SOST-positive cells further suggested

that Scl inhibition effectively targets its intended biological

pathway at the histological level (39,41,44).

Scl inhibition not only attenuated alveolar bone

loss (ABL) but also promoted regeneration through three primary

mechanisms. First, activation of the canonical Wnt pathway restores

β-catenin translocation to the nucleus, rescuing osteogenic

differentiation in periodontal ligament stem cells (13-15,41,43,45).

Second, modulation of the RANKL/OPG pathway limits

osteoclastogenesis by suppressing macrophage colony-stimulating

factor secretion from platelet-derived growth factor receptor-β

(PDGFRβ)-positive osteoprogenitors (16,37,40,42,46,47).

Third, disruption of the TNF-α/NF-κB/SOST feedback loop reduces

inflammation-induced osteocyte apoptosis and RANKL production,

thereby supporting bone preservation and regeneration (39,48,49).

Together, these multi-pathway interactions highlight the key role

of Scl in periodontitis, namely bone microenvironment

crosstalk.

Low-dose regimens (5 mg/kg) (38) showed greater efficacy compared with

higher doses (25 mg/kg), particularly in maintaining bone formation

and decreasing ABL (37,41,42,44).

This paradox suggests that treatment duration and timing may be

more influential compared with dose alone. In periodontal models,

longer treatment (22 vs. 4-6 weeks) promoted cumulative Wnt

activation, underscoring the importance of optimizing both dose and

duration for clinical translation (38). Administration route also influenced

outcomes, with subcutaneous delivery (37,40,42)

outperforming intraperitoneal injection, potentially due to

decreased hepatic first-pass metabolism (38,41,45).

However, the current evidence is limited and the superiority of

lower-dose regimens should be interpreted cautiously. More data are

needed to confirm the optimal dose-time association and future

studies should systematically examine dosing schedules and

treatment durations to validate these observations.

The present study primarily reflects therapeutic

models, as preventive evidence was scarce. A number of studies

applied therapeutic interventions following ligature removal

(37,41-43).

Taut et al (42) tested

both preventive and therapeutic arms, but only the therapeutic arm

reported quantitative data, hindering pooled analysis of preventive

effects. Hadaya et al (38)

retained ligatures during treatment to model persistent

inflammation. Compared with inflammation-resolved therapeutic

models, this design produced a larger effect size for ABL but less

pronounced regenerative benefits. These findings suggested that

persistent inflammation limits the anabolic effects of Scl

inhibition, even when short-term improvements in bone turnover

markers are observed. The coexistence of preventive and therapeutic

designs may therefore obscure biological interpretation and should

be considered when extrapolating to clinical contexts.

To assess the robustness of the present results, a

leave-one-out sensitivity analysis was performed, sequentially

excluding each study and recalculating the pooled effect size.

Results remained consistent across all iterations, indicating that

no single study disproportionately influenced the overall findings.

This supported the validity of the present conclusions despite

heterogeneity and small sample sizes.

Notably, transient increases in bone formation

markers such as P1NP have been reported, consistent with findings

from osteoporosis models (38,42,46).

None of the included studies reported osteonecrosis or similar

adverse events (38). This

suggested a favorable safety profile compared with antiresorptive

therapies such as bisphosphonates, which are associated with

medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw. The absence of major

adverse outcomes supports the translational potential of Scl

inhibition.

A number of limitations should be acknowledged.

First, heterogeneity across studies was moderate-high, stemming

from differences in animal species, periodontitis induction method,

intervention protocol (dose, duration, route of administration,

preventive vs. therapeutic design and presence or absence of

residual inflammation). These variations complicate direct

comparisons and may explain the variability in effect sizes.

However, sensitivity analysis demonstrated that the overall

conclusions remained robust despite this heterogeneity. Second, the

overall risk of bias was high or unclear across a number of

domains. A number of studies did not adequately describe

randomization procedures and allocation concealment was rarely

reported, raising concerns regarding potential selection bias.

While a number of studies reported blinding of investigators or

outcome assessors, these practices were inconsistent, increasing

the risk of performance and detection bias. In addition, small

sample size and incomplete methodological reporting further

decreased the certainty of evidence and may limit reproducibility.

These shortcomings highlight the need for stricter adherence to

established guidelines such as the ARRIVE guidelines (50) or SYRCLE (35), which emphasize transparent

reporting of randomization, allocation concealment and blinding.

Strengthening these aspects in future animal studies may minimize

bias and improve reliability. Third, the use of different outcome

assessment methods created additional inconsistency. Techniques

such as micro-CT, histology, immunohistochemistry and serum

biomarkers vary in sensitivity, quantification accuracy and the

biological processes they capture. For example, micro-CT provides

precise three-dimensional measurements of alveolar bone, whereas

histology and immunohistochemistry yield localized and often

semi-quantitative information. Serum biomarkers, by contrast,

reflect systemic rather than site-specific changes in bone

turnover. Furthermore, different biomarkers (such as OCN, P1NP and

TRAP5b) and detection approaches (immunohistochemistry vs. serum

assays) were used across studies. These discrepancies complicate

comparisons, contribute to variability in effect sizes and may

explain why some results had low statistical significance. Such

inconsistencies may also affect the reliability of the results.

Consequently, the overall certainty of evidence was downgraded to

moderate to low according to GRADE. Future studies should use

standardized and validated detection protocols or coordinate

primary outcome measures and biomarker panels, to enhance

comparability, reproducibility and reliability. Finally, the

predominance of ligature-induced models (7/8 studies) limits the

generalizability of findings to bacterially driven periodontitis

(37-44).

These limitations underscore the need for more rigorous and

standardized protocols in future. Clear reporting of randomization,

allocation concealment and blinding, along with coordination of

biomarker detection methods and outcome assessments, are key in

reducing heterogeneity and improving evidence quality. In parallel,

systematic investigation of preventive vs. therapeutic settings,

optimized dose-time regimens, alternative delivery routes and

diverse disease models are necessary to delineate the translational

potential of Scl inhibition in periodontal regeneration (37-44).

In conclusion, the present analysis suggested Scl

inhibition notably decreased ABL and enhanced the expression of

bone formation markers in preclinical periodontitis models. The

improved efficacy of low-dose subcutaneous regimens (5 mg/kg)

suggested that sustained Wnt activation rather than transient

peak-dose stimulation may underlie the superior therapeutic

response. These findings warrant clinical trials evaluating Scl-Ab

as an adjunct to conventional periodontal therapy (for example,

scaling and root planing), prioritizing dose optimization and

standardized imaging protocols.

Supplementary Material

Mechanism of sclerostin-mediated

regulation of bone remodeling, integrating Wnt/β-catenin,

RANKL/OPG, BMP and inflammatory pathways. LRP, lipoprotein

receptor-related protein; RANKL, receptor activator of nuclear

factor κ-B ligand; OPG, osteoprotegerin; Runx2, RUNX family

transcription factor 2; SOST, sclerostin.

Flow chart of study selection

according to PRISMA guidelines. WOS, Web of Science.

Subgroup analysis comparing studies

with ligature removal vs. retention. Scl, sclerostin; df, degrees

of freedom; LDD, low-dose doxycycline; CAPE, caffeic acid phenethyl

ester; SMD, standardized mean difference; IV, inverse variance

model.

Leave-one-out sensitivity analysis

showing the pooled effect size following sequential exclusion of

each study. LDD, low-dose doxycycline; CAPE, caffeic acid phenethyl

ester.

Search strategy.

Details of outcomes variables.

SYRCLE (The Systematic Review Centre

for Laboratory Animal Experimentation) results.

Level of evidence.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

MY contributed to data analysis using RevMan and

EndNote software, constructed figures, analyzed data, and wrote and

revised the manuscript. YM conceived the study, constructed

figures, analyzed data, and wrote and revised the manuscript. XQ

designed the study methodology, contributed to project

administration and resources, and provided supervision. ZQ

contributed to the study conception, critical revision of the

manuscript for important intellectual content, and overall

supervision of the project. JS contributed to study validation,

data interpretation and resource coordination. MY and YM confirm

the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors have read and

approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Abdulkareem AA, Al-Taweel FB, Al-Sharqi

AJB, Gul SS, Sha A and Chapple ILC: Current concepts in the

pathogenesis of periodontitis: From symbiosis to dysbiosis. J Oral

Microbiol. 15(2197779)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Meyle J and Chapple I: Molecular aspects

of the pathogenesis of periodontitis. Periodontol 2000. 69:7–17.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Hajishengallis G and Chavakis T: Local and

systemic mechanisms linking periodontal disease and inflammatory

comorbidities. Nat Rev Immunol. 21:426–440. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Tonetti MS, Greenwell H and Kornman KS:

Staging and grading of periodontitis: Framework and proposal of a

new classification and case definition. J Clin Periodontol 45

Suppl. 20:S149–S161. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Kwon T, Lamster IB and Levin L: Current

concepts in the management of periodontitis. Int Dent J.

71:462–476. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Graziani F, Karapetsa D, Alonso B and

Herrera D: Nonsurgical and surgical treatment of periodontitis: How

many options for one disease? Periodontol 2000. 75:152–188.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Slots J: Periodontitis: Facts, fallacies

and the future. Periodontol 2000. 75:7–23. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Haque MM, Yerex K, Kelekis-Cholakis A and

Duan K: Advances in novel therapeutic approaches for periodontal

diseases. BMC Oral Health. 22(492)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Preshaw PM and Bissett SM: Periodontitis

and diabetes. Br Dent J. 227:577–584. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Zhou N, Zou F, Cheng X, Huang Y, Zou H,

Niu Q, Qiu Y, Shan F, Luo A, Teng W and Sun J: Porphyromonas

gingivalis induces periodontitis, causes immune imbalance, and

promotes rheumatoid arthritis. J Leukoc Biol. 110:461–473.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Cardoso EM, Reis C and Manzanares-Céspedes

MC: Chronic periodontitis, inflammatory cytokines, and

interrelationship with other chronic diseases. Postgrad Med.

130:98–104. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Persson GR: Periodontal complications with

age. Periodontol 2000. 78:185–194. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Napimoga MH, Nametala C, da Silva FL,

Miranda TS, Bossonaro JP, Demasi AP and Duarte PM: Involvement of

the Wnt-β-catenin signalling antagonists, sclerostin and

dickkopf-related protein 1, in chronic periodontitis. J Clin

Periodontol. 41:550–557. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Mihara A, Yukata K, Seki T, Iwanaga R,

Nishida N, Fujii K, Nagao Y and Sakai T: Effects of sclerostin

antibody on bone healing. World J Orthop. 12:651–659.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Jacobsen CM: Application of

anti-Sclerostin therapy in non-osteoporosis disease models. Bone.

96:18–23. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Kitaura H, Marahleh A, Ohori F, Noguchi T,

Shen WR, Qi J, Nara Y, Pramusita A, Kinjo R and Mizoguchi I:

Osteocyte-related cytokines regulate osteoclast formation and bone

resorption. Int J Mol Sci. 21(5169)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Liao C, Liang S, Wang Y, Zhong T and Liu

X: Sclerostin is a promising therapeutic target for oral

inflammation and regenerative dentistry. J Transl Med.

20(221)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Chatzopoulos GS, Costalonga M, Mansky KC

and Wolff LF: WNT-5a and SOST levels in gingival crevicular fluid

depend on the inflammatory and osteoclastogenic activities of

periodontal tissues. Medicina (Kaunas). 57(788)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Yakar N, Guncu GN, Akman AC, Pınar A,

Karabulut E and Nohutcu RM: Evaluation of gingival crevicular fluid

and peri-implant crevicular fluid levels of sclerostin, TWEAK,

RANKL and OPG. Cytokine. 113:433–439. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Chatzopoulos GS, Koidou VP and Wolff LF:

Expression of Wnt signaling agonists and antagonists in

periodontitis and healthy subjects, before and after non-surgical

periodontal treatment: A systematic review. J Periodontal Res.

57:698–710. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Chatzopoulos GS, Mansky KC, Lunos S,

Costalonga M and Wolff LF: Sclerostin and WNT-5a gingival protein

levels in chronic periodontitis and health. J Periodontal Res.

54:555–565. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Ozden FO, Demir E, Lutfioglu M, Acarel EE,

Bilgici B and Atmaca A: Effects of periodontal and bisphosphonate

treatment on the gingival crevicular levels of sclerostin and

dickkopf-1 in postmenopausal osteoporosis with and without

periodontitis. J Periodontal Res. 57:849–858. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Delgado-Calle J, Sato AY and Bellido T:

Role and mechanism of action of sclerostin in bone. Bone. 96:29–37.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Iwamoto R, Koide M, Udagawa N and

Kobayashi Y: Positive and negative regulators of sclerostin

expression. Int J Mol Sci. 23(4895)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Tanaka S and Matsumoto T: Sclerostin: From

bench to bedside. J Bone Miner Metab. 39:332–340. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Cosman F, Crittenden DB, Adachi JD,

Binkley N, Czerwinski E, Ferrari S, Hofbauer LC, Lau E, Lewiecki

EM, Miyauchi A, et al: Romosozumab treatment in postmenopausal

women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 375:1532–1543.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Martiniakova M, Babikova M and Omelka R:

Pharmacological agents and natural compounds: Available treatments

for osteoporosis. J Physiol Pharmacol. 71:2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Tinsley BA, Dukas A, Pensak MJ, Adams DJ,

Tang AH, Ominsky MS, Ke HZ and Lieberman JR: Systemic

administration of sclerostin antibody enhances bone morphogenetic

protein-induced femoral defect repair in a rat model. J Bone Joint

Surg Am. 97:1852–1859. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Korn P, Kramer I, Schlottig F, Tödtman N,

Eckelt U, Bürki A, Ferguson SJ, Kautz A, Schnabelrauch M, Range U,

et al: Systemic sclerostin antibody treatment increases

osseointegration and biomechanical competence of

zoledronic-acid-coated dental implants in a rat osteoporosis model.

Eur Cell Mater. 37:333–346. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Virdi AS, Irish J, Sena K, Liu M, Ke HZ,

McNulty MA and Sumner DR: Sclerostin antibody treatment improves

implant fixation in a model of severe osteoporosis. J Bone Joint

Surg Am. 97:133–140. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Li X, Ominsky MS, Villasenor KS, Niu QT,

Asuncion FJ, Xia X, Grisanti M, Wronski TJ, Simonet WS and Ke HZ:

Sclerostin antibody reverses bone loss by increasing bone formation

and decreasing bone resorption in a rat model of male osteoporosis.

Endocrinology. 159:260–271. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Chandler J,

Welch VA, Higgins JP and Thomas J: Updated guidance for trusted

systematic reviews: A new edition of the cochrane handbook for

systematic reviews of interventions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.

10(ED000142)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron

I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan

SE, et al: The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for

reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 372(n71)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Drevon D, Fursa SR and Malcolm AL:

Intercoder reliability and validity of WebPlotDigitizer in

extracting graphed data. Behav Modif. 41:323–339. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Hooijmans CR, Rovers MM, de Vries RB,

Leenaars M, Ritskes-Hoitinga M and Langendam MW: SYRCLE's risk of

bias tool for animal studies. BMC Med Res Methodol.

14(43)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Higgins JPT and Green S: Cochrane handbook

for systematic reviews of interventions. Version 5.1.0. The

Cochrane Collaboration, London, 2011. www.handbook.cochrane.org.

|

|

37

|

Chen H, Xu X, Liu M, Zhang W, Ke HZ, Qin

A, Tang T and Lu E: Sclerostin antibody treatment causes greater

alveolar crest height and bone mass in an ovariectomized rat model

of localized periodontitis. Bone. 76:141–148. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Hadaya D, Gkouveris I, Soundia A,

Bezouglaia O, Boyce RW, Stolina M, Dwyer D, Dry SM, Pirih FQ,

Aghaloo TL and Tetradis S: Clinically relevant doses of sclerostin

antibody do not induce osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ) in rats with

experimental periodontitis. J Bone Miner Res. 34:171–181.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Kim JH, Kim AR, Choi YH, Jang S, Woo GH,

Cha JH, Bak EJ and Yoo YJ: Tumor necrosis factor-α antagonist

diminishes osteocytic RANKL and sclerostin expression in diabetes

rats with periodontitis. PLoS One. 12(e0189702)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Ozaki Y, Koide M, Furuya Y, Ninomiya T,

Yasuda H, Nakamura M, Kobayashi Y, Takahashi N, Yoshinari N and

Udagawa N: Treatment of OPG-deficient mice with WP9QY, a

RANKL-binding peptide, recovers alveolar bone loss by suppressing

osteoclastogenesis and enhancing osteoblastogenesis. PLoS One.

12(e0184904)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Ren Y, Han X, Ho SP, Harris SE, Cao Z,

Economides AN, Qin C, Ke H, Liu M and Feng JQ: Removal of SOST or

blocking its product sclerostin rescues defects in the

periodontitis mouse model. FASEB J. 29:2702–2711. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Taut AD, Jin Q, Chung JH, Galindo-Moreno

P, Yi ES, Sugai JV, Ke HZ, Liu M and Giannobile WV: Sclerostin

antibody stimulates bone regeneration after experimental

periodontitis. J Bone Miner Res. 28:2347–2356. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Yang X, Han X, Shu R, Jiang F, Xu L, Xue

C, Chen T and Bai D: Effect of sclerostin removal in vivo on

experimental periodontitis in mice. J Oral Sci. 58:271–276.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Yiğit U, Kırzıoğlu FY and Özmen Ö: Effects

of low dose doxycycline and caffeic acid phenethyl ester on

sclerostin and bone morphogenic protein-2 expressions in

experimental periodontitis. Biotech Histochem. 97:567–575.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Ominsky MS, Boyce RW, Li X and Ke HZ:

Effects of sclerostin antibodies in animal models of osteoporosis.

Bone. 96:63–75. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Ashifa N, Viswanathan K, Sundaram R and

Srinivasan S: Sclerostin and its role as a bone modifying agent in

periodontal disease. J Oral Biosci. 63:104–110. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

de Vries TJ and Huesa C: The osteocyte as

a novel key player in understanding periodontitis through its

expression of RANKL and sclerostin: A review. Curr Osteoporos Rep.

17:116–121. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Sapir-Koren R and Livshits G: Osteocyte

control of bone remodeling: Is sclerostin a key molecular

coordinator of the balanced bone resorption-formation cycles?

Osteoporos Int. 25:2685–2700. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Li X, Niu QT, Warmington KS, Asuncion FJ,

Dwyer D, Grisanti M, Han CY, Stolina M, Eschenberg MJ, Kostenuik

PJ, et al: Progressive increases in bone mass and bone strength in

an ovariectomized rat model of osteoporosis after 26 weeks of

treatment with a sclerostin antibody. Endocrinology. 155:4785–4797.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Percie du Sert N, Hurst V, Ahluwalia A,

Alam S, Avey MT, Baker M, Browne WJ, Clark A, Cuthill IC, Dirnagl

U, et al: The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: Updated guidelines for

reporting animal research. PLoS Biol. 18(e3000410)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|