Introduction

SRY-related high-mobility group box protein B5

(SOX5), a member of the SRY-related HMG-box gene family, has gained

interest for its functions in developmental biology and disease

pathogenesis (1-5).

In tumor biology, abnormal SOX5 expression and activity is

associated with the advancement of a number of human malignancies,

including hepatocellular carcinoma [promoting epithelial-mesencymal

transition (EMT) and invasion], bladder cancer (modulating

migration and therapy resistance), prostate cancer (driving

metastasis via EMT), ovarian cancer (regulating glycolysis and

proliferation), gastric cancer (enhancing proliferation and

migration), tongue carcinoma (facilitating tumorigenesis) and

esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (where its downregulation is

associated with a poor prognosis) (6-8).

While SOX5 may have tumor-suppressive characteristics in some

tissues, its upregulation in numerous malignancies is acknowledged

as a notable contributor to tumor growth, rendering it a key

subject within cancer research.

The protein encoded by SOX5 is part of the high

mobility group of proteins, which modulate transcription through

DNA binding and are key in cell differentiation. In typical

physiological conditions, SOX5 regulates collagen synthesis, neural

development and cartilage creation. In cancer, the function of SOX5

is altered, potentially facilitating tumor initiation and

progression by regulating the cell cycle and promoting malignant

behaviors (such as inducing EMT, enhancing cell migration and

invasion, maintaining cancer stem cell properties) or enabling

immune evasion (9-12).

Altered SOX5 expression has been documented in a

number of malignancies, including lung, breast, gastric cancers and

melanoma (13,14). In lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD),

increased SOX5 expression is associated with adverse prognosis,

including reduced survival and enhanced recurrence rates. This

modified expression indicates that SOX5 may enhance tumor cell

proliferation and survival by activating downstream signaling

pathways, such as Wnt/β-catenin and PI3K/AKT. In addition to its

intrinsic effects on tumor cells, SOX5 also affects the tumor

microenvironment (TME). It can regulate the activity of

tumor-associated fibroblasts, thereby influencing immunological

responses and facilitating immune evasion (15-17).

Additionally, SOX5 has been associated with the regulation of tumor

angiogenesis, highlighting its complex involvement in cancer

advancement.

Understanding the varied expression patterns and

roles of SOX5 across different tumor types is key for the

advancement of novel cancer therapeutics. Consequently, the aims of

the present study are threefold: i) To delineate the molecular

regulatory network of SOX5; ii) to characterize its distinct

involvement in carcinogenesis; and iii) to explore methodologies

for improving therapeutic efficacy through the targeting of

SOX5-associated pathways. Pan-cancer analysis provides a thorough

method to elucidate the role of SOX5 role in tumorigenesis,

establishing a theoretical basis and prospective targets for

forthcoming clinical therapies.

Materials and methods

Data processing

Within the present study, data from The Cancer

Genome Atlas (TCGA; https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/) was utilized. TCGA is

a large-scale cancer genome project jointly funded and managed by

the National Cancer Institute and the National Human Genome

Research Institute to advance the scientific understanding of

cancer. Specifically, RNA-sequencing data (fragments per kilobase

format) and clinical annotations from TCGA Pan-Cancer Atlas

(version 2018) were obtained through the University of California,

Santa Cruz Xena browser (https://xena.ucsc.edu/). Normalization and batch

correction were performed using the ComBat algorithm from the ‘sva’

R package (version 4.3.1) (18) to

mitigate technical variations across sequencing centers. Samples

with incomplete clinical metadata or low sequencing quality (read

count <10 million) were excluded.

For validation, Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO;

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/)

datasets (GSE30219, GSE31210 and GSE50081) (19-21)

were retrieved using the ‘GEOquery’ R package (22). Probes were annotated to gene

symbols based on platform-specific annotation files (such as the

platform name ‘GPL570’ for the array name ‘Affymetrix Human

Genome-U133 Plus 2.0’). For genes mapped by multiple probes, the

duplicates were collapsed by selecting the single probe with the

maximum mean expression value across all samples for that gene.

Additionally, the ‘TCGAbiolinks’ R package (23) was employed to download and access

TCGA data, facilitating the integration and bioinformatics analysis

of numerous data types.

Expression of SOX5 gene in a number of

cancers

Differential SOX5 expression across tumor and

corresponding normal tissues in TCGA was examined through use of

the ‘TCGAplot’ R package (version 1.0) (24). For cancers lacking normal tissue

data in TCGA [including diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBC) and

mesothelioma (MESO)], GEO datasets (GSE12453 and GSE51024)

(25,26) were supplemented. Normalized

log2-transformed expression values from both sources

were compared using Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. This analysis provided

SOX5 expression profiles in normal and tumor tissues for cancers

including DLBC, low-grade glioma, MESO, ovarian serous

cystadenocarcinoma, testicular germ cell tumor (TGCT), uterine

carcinosarcoma and uveal melanoma.

Diagnosis and prognosis analysis

Using TCGA data, the diagnostic potential of SOX5

was assessed by generating receiver-operating characteristic (ROC)

curves with the ‘pROC’ R package (27). An area under the curve (AUC) value

of 0.5-0.7 indicated a low diagnostic value, 0.7-0.9 indicated a

moderate value and >0.9 indicated a high diagnostic value.

Prognostic associations of SOX5 expression with overall survival

(OS), disease-specific survival (DSS), disease-free interval (DFI)

and progression-free interval (PFI) were evaluated using the

SangerBox database (version 3.0; http://sangerbox.com/). Statistical significance was

determined using multiple-testing correction (the

Benjamini-Hochberg method) (28).

Patients were stratified by median SOX5 expression and multivariate

Cox regression adjusted for age, stage and sex was applied where

appropriate.

Correlation analysis of immune

infiltration

Immune infiltration in the TME was assessed by

calculating Stromal Score, Immune Score and Estimation of Stromal

and Immune Cells in Malignant Tumor Tissues Using Expression Data

(ESTIMATE) Score using the ‘ESTIMATE’ R package (29). The cancer immunity cycle was

analyzed using the Tumor Immune Estimation Resource 2.0 web tool

(http://timer.cistrome.org/) to evaluate

correlations between SOX5 expression and immune activation steps

such as T cell recruitment and antigen presentation. Immune cell

fractions were estimated using Cell-Type Identification by

Estimating Relative Subsets of RNA Transcripts (CIBERSORT version

1.04) (30) deconvolution and

single-sample Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (ssGSEA) through the

Gene Set Variation (‘GSVA’) R package (31) quantified immune cell enrichment.

Associations between SOX5 expression and microsatellite instability

(MSI), tumor mutational burden (TMB) and immune checkpoint proteins

across tumors were analyzed in SangerBox (http://sangerbox.com/) using Pearson correlation

tests.

Drug sensitivity analysis

Drug sensitivity data from the Genomics of Drug

Sensitivity in Cancer 2 database (version Release 8.5) (https://www.cancerrxgene.org/) were processed using

the ‘oncoPredict’ R package (version 0.2) (32). IC50 values were

estimated through ridge regression and normalized to Z-scores.

Drugs with a Z-score >2 were considered to be significantly

associated with SOX5 expression.

Analysis of tumor mutation

patterns

The cBioPortal database (https://www.cbioportal.org/) was used to explore

associations between SOX5 expression and tumor mutation patterns.

Somatic mutations and copy-number alterations were retrieved from

cBioPortal (TCGA Pan-Cancer Atlas; version 2018). Patients were

divided into high and low SOX5 expression groups (top/bottom 25%;

high SOX5, n=250; low SOX5, n=261). Mutational signatures were

visualized using the ‘Maftools’ package (version 2.6.05) (33), enabling comprehensive analysis of

somatic mutation patterns in TCGA-LUAD cohort.

Functional enrichment analysis

Co-expression networks were constructed using

LinkedOmics (www.linkedomics.org; TCGA_LUAD cohort; HiSeq platform)

with Pearson correlation [r>0.3; false discovery rate (FDR)

<0.05] to identify genes co-expressed with SOX5. GSEA of

Molecular Signatures Database Hallmark and Kyoto Encyclopedia of

Genes and Genomes (KEGG) gene sets, as well as GSVA of Gene

Ontology terms were performed to explore associated biological

functions and pathways. Analyses were performed with 1,000

permutations and results with FDR-adjusted P<0.05 were

considered significant.

Cell culture

Human non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cell lines

A549 and H1299, as well as the normal human bronchial epithelial

cell line BEAS-2B, were obtained from the Cell Bank of the Chinese

Academy of Sciences (Shanghai Institute of Biochemistry and Cell

Biology). H1299, A549 and BEAS-2B normal lung epithelial cells were

cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) at 37˚C in a humidified incubator with 5%

CO2. Cells were digested every 48 h with 0.25%

trypsin-EDTA (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and passaged

at a 1:3 ratio. Experiments utilized cells between passages

5-20.

Cell transfection

For SOX5 knockdown, A549 cells were transfected with

50 nM of a SOX5-targeting siRNA (sense, 5'-GGGUCGUGUUCAAUCUUAUU-3'

and antisense, 5'-UUAAGAUUGAACACGACCCUU-3'; Shanghai GenePharma

Co., Ltd.) or a scrambled control siRNA (sense,

5'-GGCUGGUAGUUGGCAUUUAUU-3' and antisense,

5'-UAAAUGCCAACUACCAGCCUU-3'; Shanghai GenePharma Co., Ltd.) using

Lipofectamine™ RNAiMAX (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

according to the manufacturer's instructions. Following

transfection, cells were incubated at 37˚C in a 5% CO2

atmosphere for 24 h to allow for efficient knockdown. Experimental

groups consisted of the untreated control, scrambled siRNA control

and SOX5 knockdown. SOX5 expression was measured after the 24-h

incubation period using quantitative PCR (qPCR).

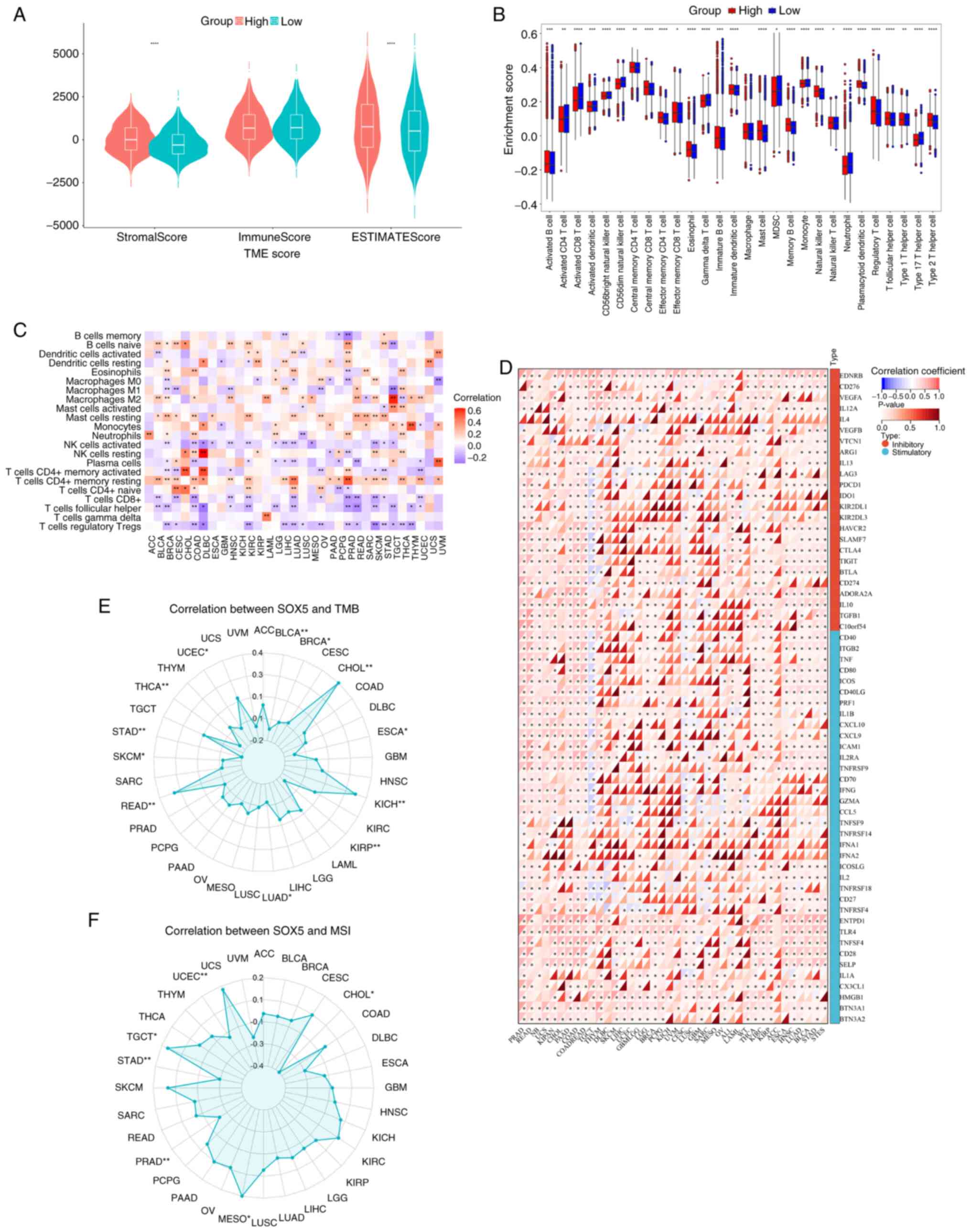

Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay

At 24 h post-transfection, cells were seeded in

96-well plates (5x103 cells/well) and incubated for 24

h. Furthermore, 10 µl of Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) solution

(Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Inc.) was added to each well and

the plates were incubated for 4 h. A total of 150 µl DMSO was added

to each well to dissolve the formazan crystals. The absorbance at

490 nm was then measured using a microplate reader (BioTek Synergy

HTX; BioTek; Agilent Technologies, Inc.). Cytotoxic activity (%)

using optical density (OD) values was calculated as:

Wound healing assay

Cell migration was evaluated by monitoring wound

closure over 24 h. Cells were grown to ~80% confluence in 6-well

plates,, scratched with a sterile 200 µl pipette tip, washed with

PBS and cultured in serum-free DMEM. Images were captured at 0 and

24 h using the Axiovert 200 microscope (Zeiss GmbH) and analyzed

with ImagePro Plus software (version 6.0). Experiments were

performed in triplicate.

Transwell invasion assay

After 24 h of transfection, cells

(5x104/well) were seeded into Transwell chambers. The

chambers were pre-coated with Matrigel by incubating with a diluted

Matrigel solution at 37˚C for 1 h to allow for polymerization. The

cells were then plated in serum-free medium. Medium containing 10%

FBS was added to the lower chamber. After a 24-h incubation period

at 37˚C, non-migrated cells on the upper surface of the membrane

were carefully removed with a cotton swab. The invaded cells on the

lower surface were fixed with 95% ethanol for 15 min at room

temperature and subsequently stained with 0.1% crystal violet for

20 min at room temperature. After washing and air-drying, the cells

were imaged in three random fields per chamber at x100

magnification using an inverted light microscope (Olympus

Corporation).

Reverse Transcription Quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was isolated from cultured A549 cells

using the TRIzol™ reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) according to the manufacturer's protocol. RNA concentration

and purity were determined spectrophotometrically. Subsequently, 1

µg of total RNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA using the

PrimeScript™ RT Reagent Kit (Takara Bio Inc.) in strict accordance

with the manufacturer's instructions. qPCR was performed using

PowerUp™ SYBR™ Green Master Mix (cat. no. A25742; Applied

Biosystems) on an Applied Biosystems 7500 Real-Time PCR System. The

thermal cycling conditions were as follows: Initial denaturation at

95˚C for 2 min; followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95˚C for

15 sec and annealing/extension at 60˚C for 1 min. A melting curve

analysis was performed post-amplification to verify reaction

specificity. Relative mRNA expression levels were calculated using

the 2-ΔΔCq method (34), with GAPDH serving as the internal

reference gene for normalization using the following formulae:

∆Cq=Cqtarget-CqGAPDH;

∆∆Cq=∆Cqreference-∆Cqtest. The primer

sequences were as follows: GAPDH forward,

5'-CATCATCCCTGCCTCTACTGG-3' and reverse,

5'-GTGGGTGTCGCTGTTGAAGTC-3'; and SOX5 forward,

5'-CAGATGGAGAGGTAGCCATGG-3 and reverse,

5'-CCATTGTATTGTGCTGAGAAGTG-3'.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS

(version 26.0; IBM Corp.) and R (version 4.3.1). For comparisons

between two groups of continuous variables, the unpaired Student's

t-test was used for normally distributed data and the unpaired

Mann-Whitney U test for non-normally distributed data. For

comparisons among three or more groups, one-way ANOVA (parametric)

was applied, followed by Tukey's post hoc test for multiple

comparisons. The prognostic value of SOX5 expression was evaluated

by univariate Cox regression analysis and Kaplan-Meier survival

analysis with the log-rank test. Associations between SOX5

expression and immune-related regulatory factors were assessed

using Spearman's rank correlation analysis. A two-sided P-value of

<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

Differential expression of SOX5 in

pan-cancer between tumor and normal tissue

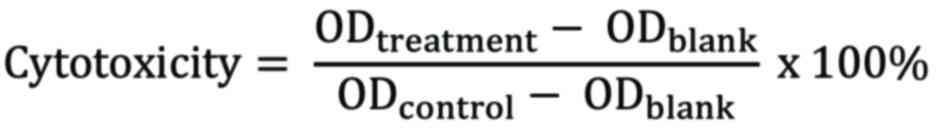

Using box plots generated from TCGA database, the

expression levels of SOX5 mRNA in tumor and normal tissues were

analyzed. As shown in Fig. 1A,

SOX5 expression was significantly higher in tumor tissues compared

with normal tissues in certain cancer types, such as PCPG

(P<0.01). By contrast, in numerous cancers, including LUAD, lung

squamous cell carcinoma (LUSC) and breast invasive carcinoma

(BRCA), SOX5 mRNA expression was markedly lower in tumor tissues

compared with adjacent normal tissues (P<0.05). Fig. 1B further demonstrated this pattern,

showing lower SOX5 expression was observed in tumor tissues across

the majority of cancers analyzed (P<0.05). Collectively, these

results indicate that SOX5 expression is generally reduced in

numerous cancer tissues

Predictive value of SOX5 expression

for diagnosis and prognosis

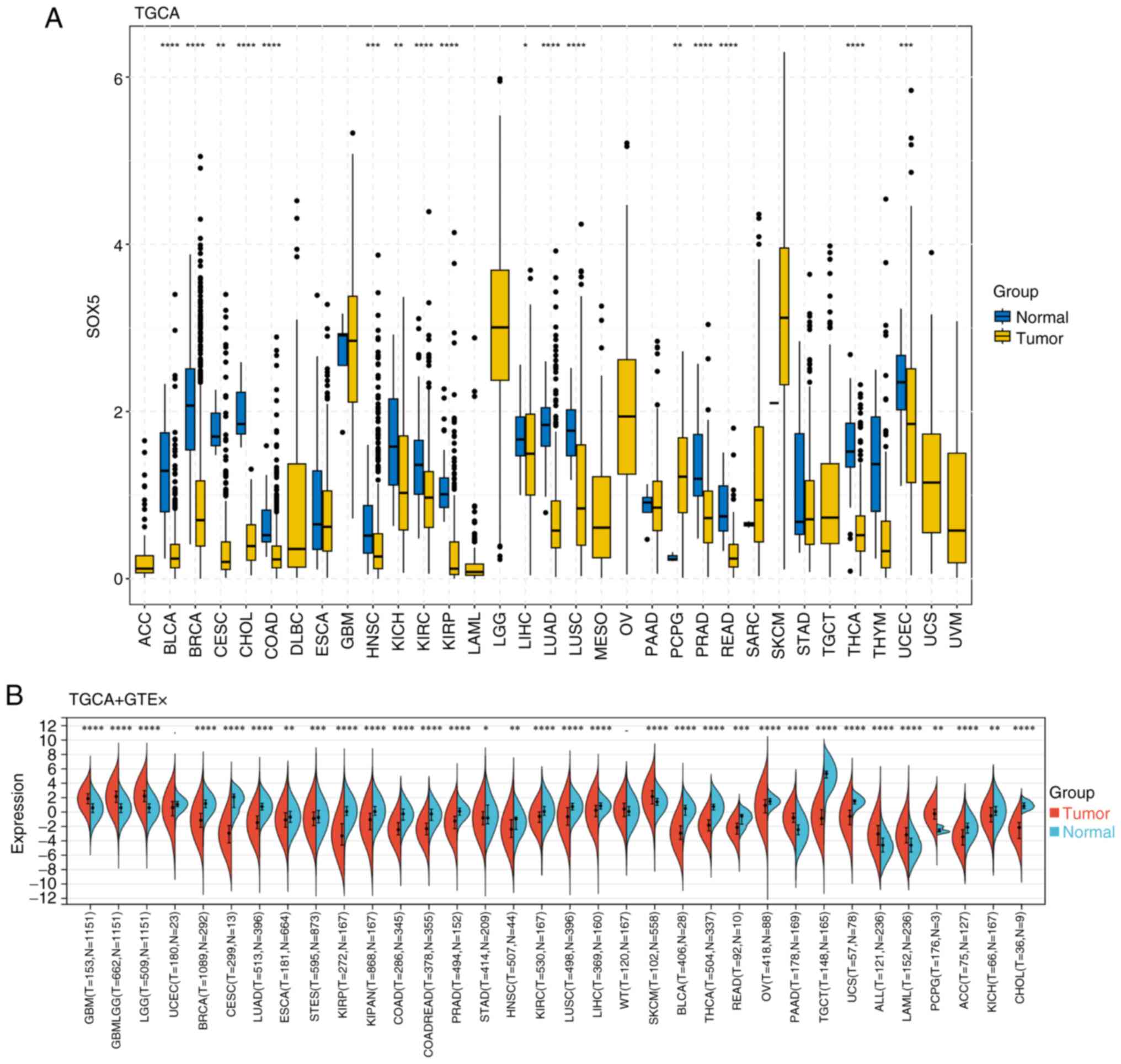

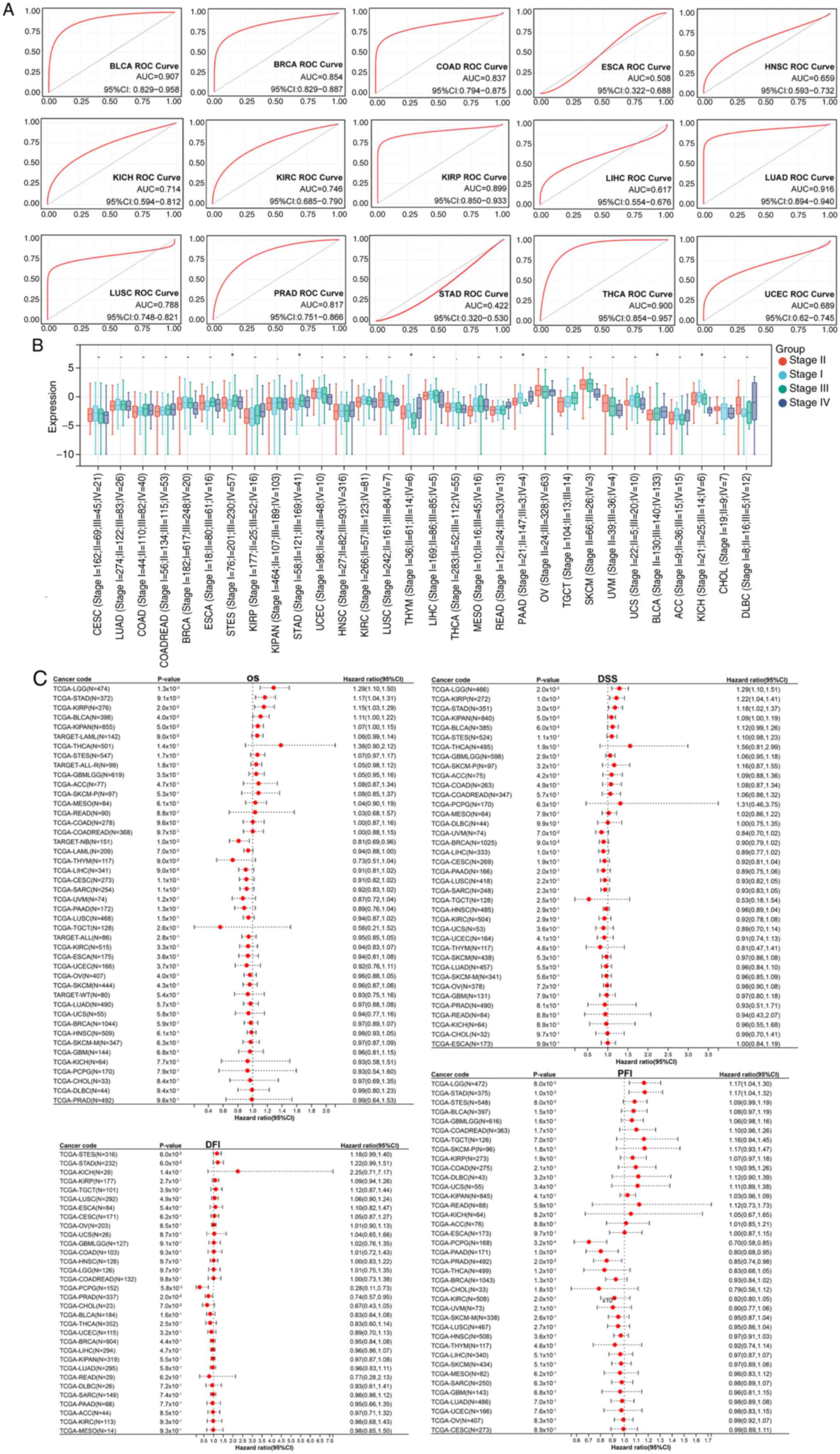

Fig. 2 illustrates

the diagnostic and prognostic significance of SOX5 across cancers.

ROC curve analysis (Fig. 2A)

demonstrated good diagnostic performance for head-neck squamous

cell carcinoma (AUC=0.953; 95% CI, 0.928-0.978) and LUAD

(AUC=0.916; 95% CI, 0.894-0.940), with notable discrimination in 15

additional cancer types (AUC range, 0.508-0.893), all exceeding

random chance. Differential expression analysis (Fig. 2B) showed that SOX5 plays an

environment-dependent role in tumorigenesis and is progressively

dysregulated at various tumor stages. We observed significant

differences in six types of tumors, such as STES (Stage I=76;

II=201; III=230; IV=57) (P<0.05), STAD (Stage I=58; II=121;

III=169; IV=41) (P<0.05), THYM (Stage I=36;II=61;III=14;IV=6)

(P<0.05), PAAD (Stage I=21;II=147; III=3;IV=4) (P<0.05), BLCA

(Stage II=130;III=140;IV=133) (P<0.05), and KICH (Stage

I=21;II=25;III=14;IV=6) (P<0.05). Notably, 78% (18/23) of

carcinomas showed marked downregulation of SOX5.

| Figure 2Diagnostic and prognostic value of

SOX5 in pan-cancer. (A) ROC curves for diagnosing 15 cancers based

on SOX5 expression. (B) Boxplots showing the association between

SOX5 expression levels and seven clinical characteristics in 30

cancer types. (C) Circular histogram of OS, DSS, DFI and PFI of

SOX5 in 44 types of cancer using Kaplan-Meier analysis.

*P<0.05; **P<0.01;

***P<0.001. ns, not significant; ROC, receiver

operator characteristic; SOX5, SRY-related high-mobility group box

protein B5; OS, overall survival; DSS, disease-specific survival;

DFI, disease-free interval; PFI, progression-free interval; BLCA,

bladder urothelial carcinoma; BRCA, breast invasive carcinoma;

COAD, colon adenocarcinoma; ESCA, esophageal carcinoma; KICH,

kidney chromophobe; KIRC, kidney renal clear cell carcinoma; KIRP,

kidney renal papillary cell carcinoma; LIHC, liver hepatocellular

carcinoma; HNSC, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma; LUAD, lung

adenocarcinoma; LUSC, lung squamous cell carcinoma; PRAD, prostate

adenocarcinoma; STAD, stomach adenocarcinoma; THCA, thyroid

carcinoma; UCEC, uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma. |

Multivariate survival analysis (Fig. 2C) demonstrated clinically relevant

prognostic stratification. Forest plots for OS, DSS, DFI and PFI

revealed that elevated SOX5 expression was associated with worse

outcomes [hazard ratio (HR) >1; 95% CI, excluding 1] in a number

of cancers, while low expression was associated with protective

effects (HR <1). These integrated findings suggest that SOX5 is

a key dual-purpose biomarker for early cancer detection and precise

prognostication.

SOX5 in pan-cancer immune

infiltration

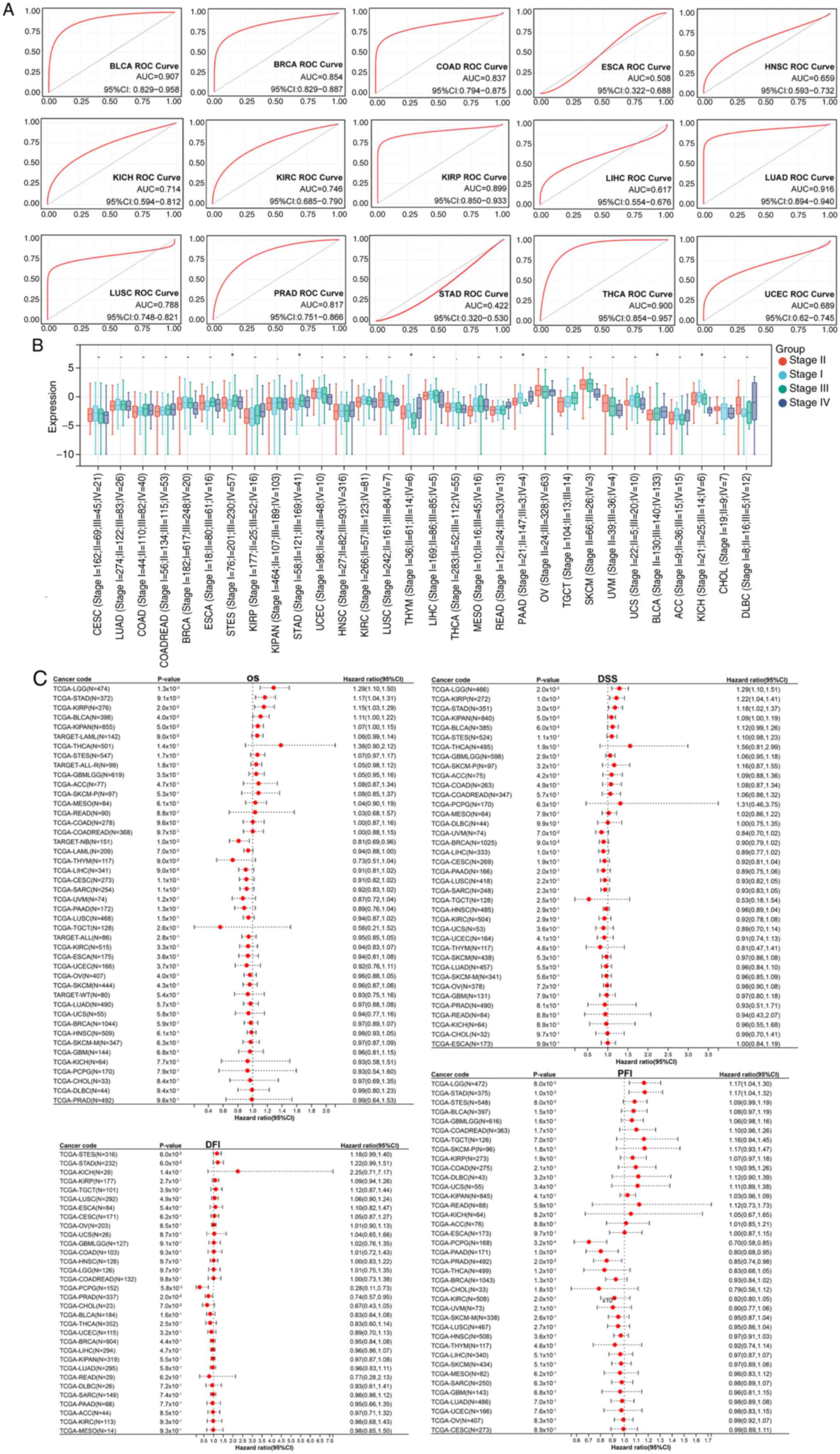

The present analysis identified SOX5 as a notable

modulator of tumor immune dynamics. Violin plots (Fig. 3A) showed significantly higher SOX5

expression in tumor tissues compared with normal tissues

(P<1x10-15), while box plots (Fig. 3B) revealed notable inter-cohort

heterogeneity. ESTIMATE, CIBERSORT and ssGSEA analyses demonstrated

that high SOX5 expression is associated with an activated TME and

increased immune scores (P<0.05), particularly in LUAD and

UCEC.

Heatmap analysis (Fig.

3C) revealed a negative correlation between SOX5 and cytotoxic

T cell infiltration (Pearson r=-0.68; P<2x10-16) and

a positive correlation between SOX5 and regulatory T cell abundance

(r=0.59; P<5x10-9), indicating immunosuppressive

reprogramming. Radar charts (Fig.

3E and F) further showed that

SOX5 expression was inversely correlated with TMB (r=-0.43;

P<0.001) and microsatellite instability (r=-0.51; P<0.0001),

although subtype-specific variations existed. Correlation networks

(Fig. 3D) revealed significant

co-expression of SOX5 with immune checkpoint molecules [programmed

death-ligand 1 (PD-L1), r=0.62; cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated

protein 4 (CTLA-4), r=0.57; P<0.05], positioning SOX5 as a key

regulator of immune evasion and DNA damage response in cancer.

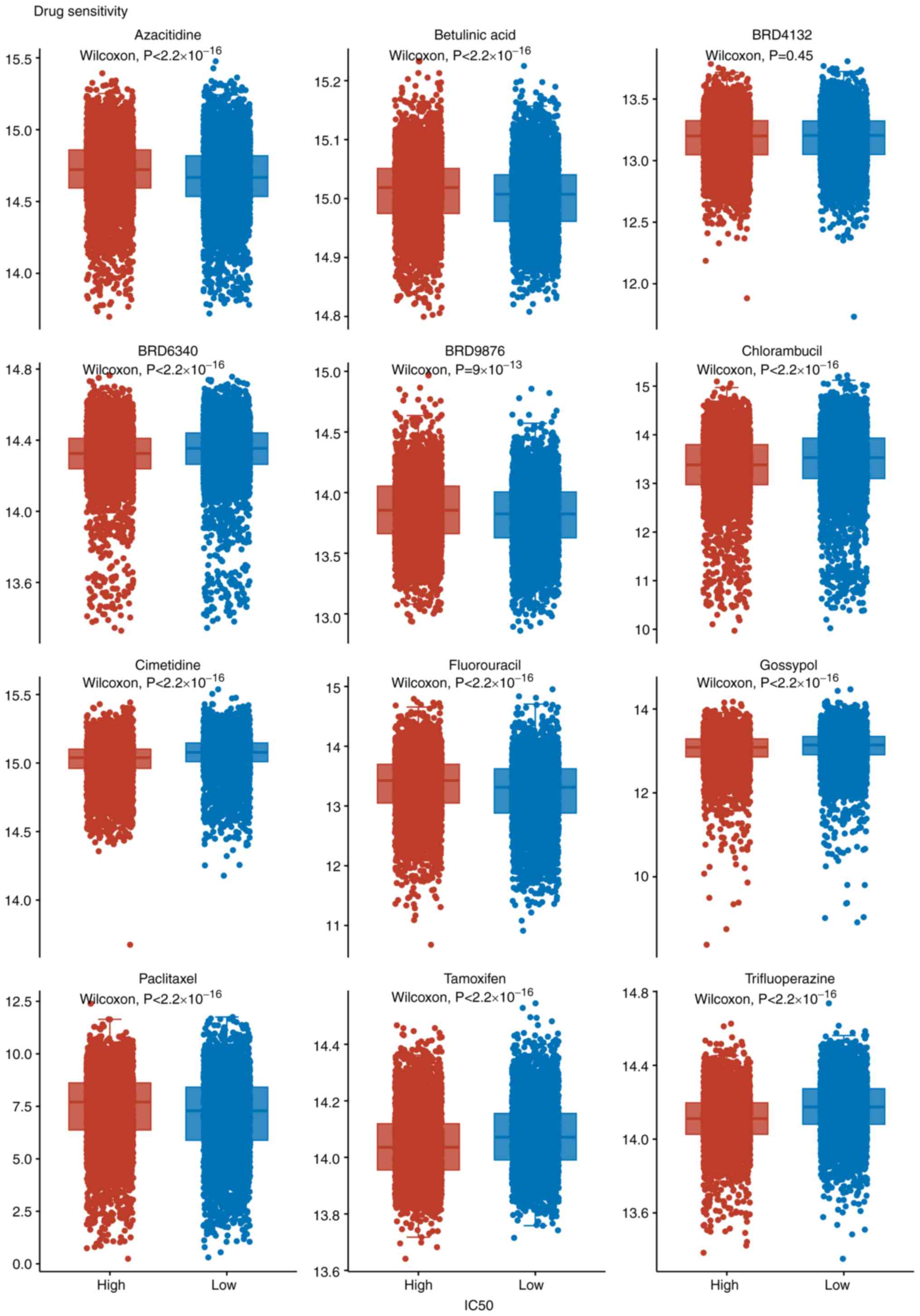

Drug sensitivity analysis

The drug sensitivity screening revealed

statistically significant differences in inhibitory potency between

the high and low groups for the majority of tested compounds. With

the exception of BRD4132, all agents, including azacitidine,

betulinic acid, dorsomorphin, etoposide, GW843682X, mitotane,

PX-478, S-trityl-L-cysteine, sanguinarine, and selenium,

demonstrated markedly enhanced efficacy against the high group (all

P<0.001). By contrast, BRD4132 exhibited no significant

difference in activity between the two groups (P=0.45). These

findings successfully identify a panel of candidate compounds with

high potential for selective efficacy against the defined cellular

model, providing a substantive basis for further investigation into

targeted therapeutic strategies (Fig.

4). Pharmacogenomic profiling of 12 drugs revealed notably

distinct IC50 distributions between ‘SOX5_High’ and

‘SOX5_Low’ cohorts. Wilcoxon rank-sum tests showed significant

differences (P<2.2x10-16) for 11 compounds, including

azacitidine and betulinic acid, with BRD4132 as the only exception

(P=0.45). These results highlight SOX5 expression as a potential

predictor of therapeutic response, underscoring its value as a

precision oncology biomarker.

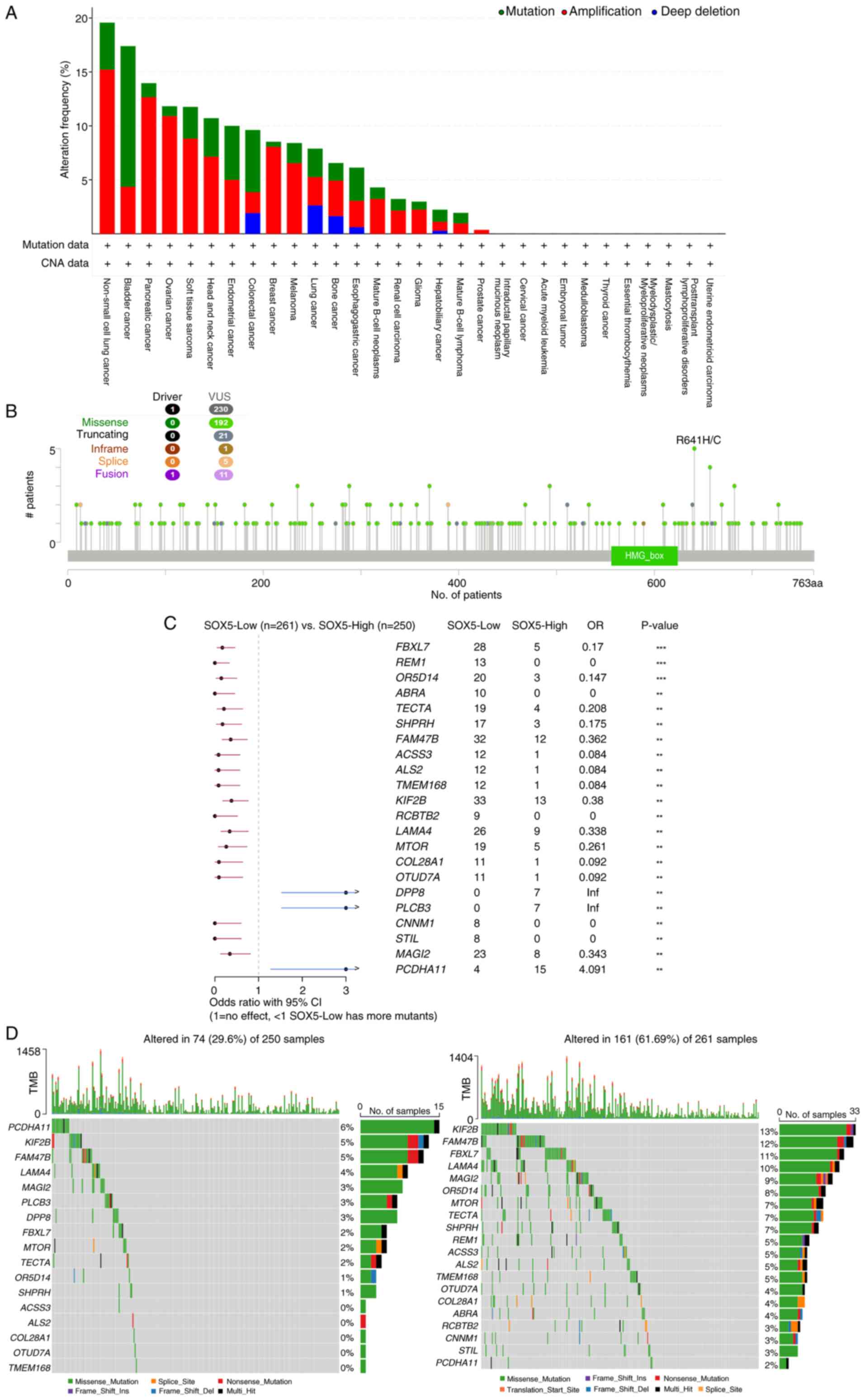

Tumor mutation pattern analysis

Pan-cancer genomic profiling revealed that

SOX5-altered tumors exhibit distinct molecular signatures.

Alteration frequency analysis (Fig.

5A) demonstrated prevalent SOX5 mutations and copy-number

changes with lineage-specific prevalence, notably in gastric and

pancreatic cancers. Detailed characterization (Fig. 5B) showed truncating mutations as

the predominant alteration subtype.

Expression stratification (Fig. 5C) revealed that ‘SOX5_Low’ tumors

were associated with transcriptional suppression of cardiac

morphogenesis pathways [odds ratio (OR)=0.32;

P<1x10-15] and upregulation of cell-cycle regulators

(OR=3.41; P<8x10-10). Waterfall plots (Fig. 5D) demonstrated mutually exclusive

alterations between ‘SOX5_High’ and ‘SOX5_Low’ groups, with

truncating mutations concentrated in ‘SOX5_Low_tumors’ (P=0.0028)

and the analysis demonstrated significant associations between SOX5

expression status and mutations in specific signaling pathways,

primarily the PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway and PD-L1 associated immune

regulation (P<0.05). (P<0.05). These findings establish SOX5

loss-of-function as a driver of gene expression changes, especially

in LUAD and other cancers with frequent SOX5 variation and

amplification.

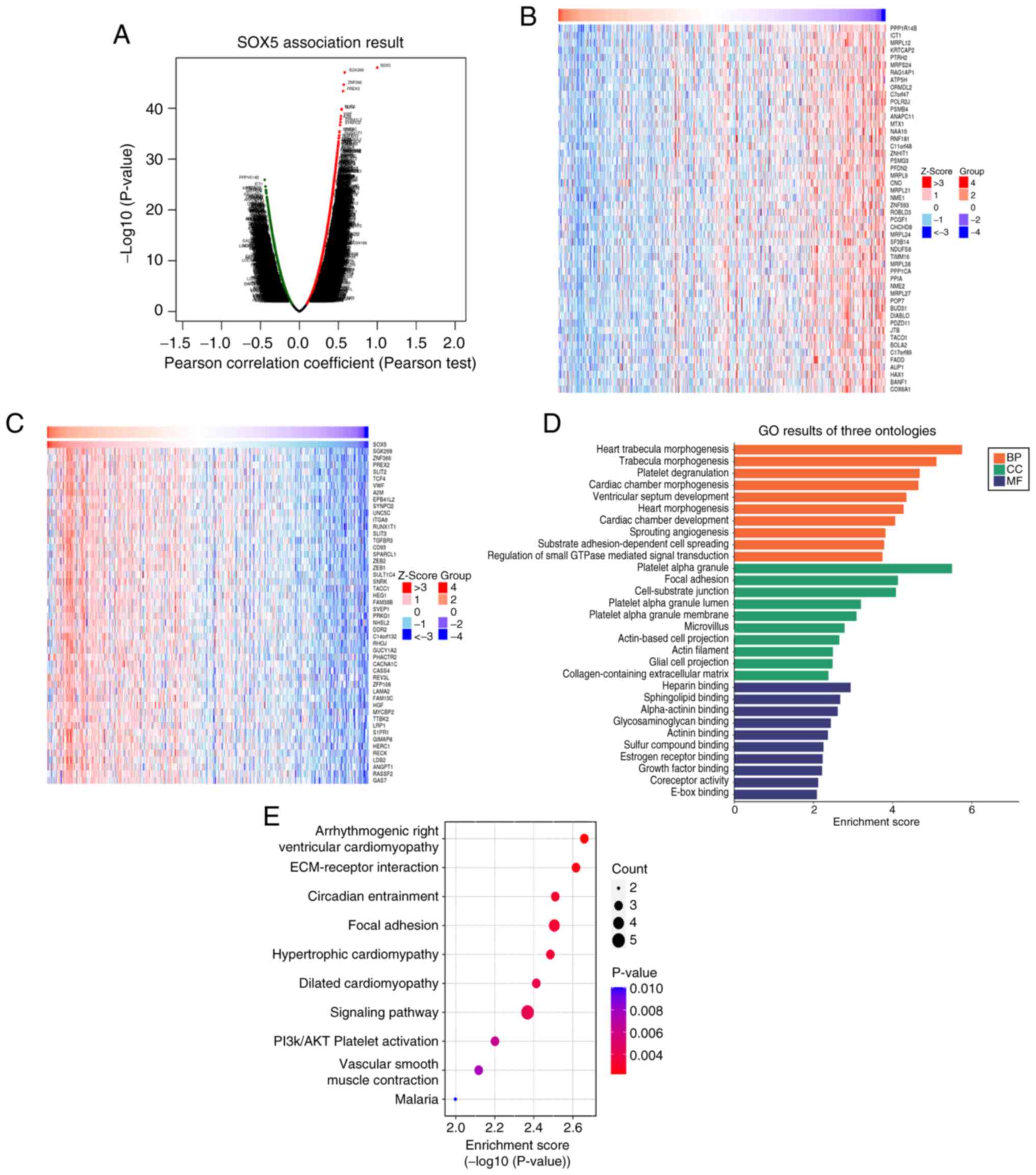

Functional enrichment analysis

Multi-omics integration revealed SOX5 as a central

regulator of cardiac morphogenesis and tumor biology. Pearson

correlation analysis (Fig. 6A)

showed strong associations (r=1; P<1x10-30) with

select targets. Z-score clustering (Fig. 6B and C) demonstrated SOX5 co-activation of

morphogenetic pathways, such as heart trabecula morphogenesis

(Z>3) and cardiac chamber development, alongside suppression of

proliferative pathways (cell cycle, Z<-3; small GTPase

signaling, Z<-2). KEGG and Hallmark enrichment analyses revealed

SOX5 involvement in biological processes including cardiac

morphogenesis and angiogenesis, cellular components such as the

actin cytoskeleton and molecular functions including actin binding.

KEGG analysis (Fig. 6E) implicated

SOX5 dysregulation in ‘Arrhythmogenic right ventricular

cardiomyopathy’ pathogenesis (-log10P>20), mediated

by altered adhesion molecules, extracellular matrix receptors and

metalloproteinases (P<0.05). These findings highlight SOX5 as a

key regulator of structural integrity and tumor biology in

LUAD.

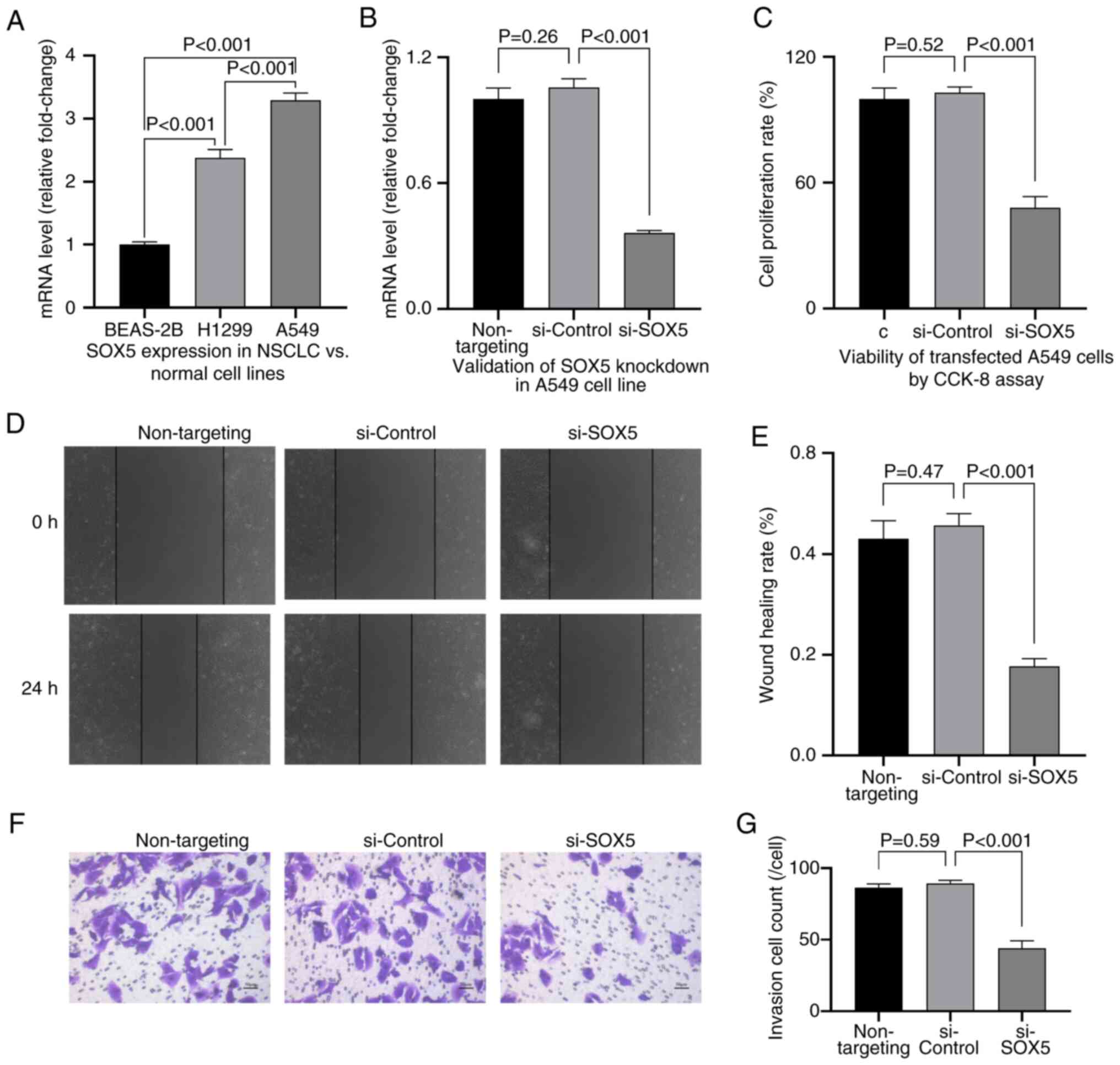

SOX5 silencing inhibits NSCLC

progression in vitro

Functional studies revealed that SOX5 is upregulated

in NSCLC cell lines (H1299 and A549) compared with normal bronchial

epithelial cells (BEAS-2B; P<0.001; Fig. 7A). SOX5 knockdown in A549 cells,

confirmed using qPCR (Fig. 7B),

significantly inhibited proliferation (P<0.01; Fig. 7C), migration (scratch assay;

P<0.001; Fig. 7D and E) and invasion (Transwell assay;

P<0.001; Fig. 7F and G).

The study findings are consistent with the

established oncogenic role of SOX5 in other cancers. In

triple-negative breast cancer, SOX5 drives stemness, EMT and immune

evasion (35). In melanoma, SOX5

promotes migration and invasion via transcriptional regulation by

the oncogenic long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) SLNCR1(36). Mechanistically, SOX5 interacts with

co-activators, such as transcriptional co-activator with

PDZ-binding motif, stabilizing effectors, such as collagen type X

α1 chain, and enhancing extracellular matrix remodeling (37,38).

In gliomas, SOX5:anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) fusion drives

tumor progression, with ALK inhibitors suppressing growth in

vivo (39). Collectively,

these data validate SOX5 as a driver of NSCLC aggressiveness and a

potential therapeutic target.

Discussion

Research into the mechanisms driving malignant tumor

development and progression has advanced beyond initial

understandings. The rapid development of molecular biological

technologies, particularly the application of omics approaches and

bioinformatics, has been key in elucidating the functional roles of

tumor-associated genes and evaluating their potential as diagnostic

biomarkers and therapeutic targets (40-43).

SOX5 displays diverse expression patterns and

biological roles across human cancers. In the present study, the

role of SOX5 in tumor development was investigated, with a focus on

the impact of SOX5 on the TME and its potential mechanisms

underlying tumor progression, diagnosis and prognosis, employing a

range of bioinformatics tools and statistical approaches.

Results indicate that the functional role of SOX5 in

tumorigenesis is highly context-dependent. Dysregulation of SOX5

(upregulation or downregulation) varies notably among cancer types

and is strongly influenced by cell-of-origin, driver mutations and

the surrounding signaling microenvironment (44-46).

Specifically, SOX5 acts predominantly as a tumor suppressor in

epithelial carcinomas driven by somatic mutations, where it is

frequently downregulated or inactivated (47-49),

however exhibits oncogenic properties in specific malignancies such

as germ cell tumors, where it is maintained or upregulated

(45). This dual role underscores

the importance of evaluating SOX5 as a diagnostic or prognostic

biomarker and therapeutic target within the context of specific

cancer types (45,48,50).

The differential expression of SOX5 across cancers

not only reflects its complexity in tumor development but also

highlights distinct underlying biological mechanisms (51-53).

Reduced SOX5 expression in LUAD, LUSC and BRCA is consistent with a

tumor-suppressive role, potentially through regulation of the cell

cycle, induction of senescence, or promotion of apoptosis.

Conversely, elevated SOX5 expression in germ cell tumors suggests

an oncogenic role, possibly by activating pro-proliferative

pathways, enhancing migration and invasion or inhibiting

apoptosis.

Previous studies further illustrate these divergent

roles (3,54,55).

In Kaposi's sarcoma, SOX5 overexpression inhibits

epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in Kaposi's sarcoma-associated

herpesvirus-infected cells, suggesting a tumor-suppressive function

and therapeutic potential. In germ cell tumors, where germ

cell-specific expression patterns prevail, increased SOX5 levels

may reflect the physiological role it has in reproductive system

development, repurposed within the TME to drive uncontrolled

growth. This variability in expression patterns underscores the

necessity for detailed, cancer type-specific research into SOX5

function. For example, the role of SOX5 in promoting germ cell

tumors may involve interactions with specific transcription factors

or growth factors that are lost in other types of cancer. In TGCTs,

amplification of the 12p11.1-p12.1 region (which contains the SOX5

gene) has been identified as a key event (56), and this 12p gain [including i(12p)

and 12p11.2-12.1 amplification] is associated with aggressive tumor

progression (55). Although SOX5

is located within this critical region, its expression is lost in

some 12p amplification-positive TGCTs, suggesting that its role may

be mediated through complex regulatory networks. This mechanism may

involve interactions with germ cell tumor-specific signaling

pathways such as the KIT/KITLG pathway, or exert effects through

regulating cell proliferation, migration and EMT (50).

Beyond its tissue-specific functions, SOX5 shows

notable potential as a biomarker. In cancer diagnosis and

prognosis, biomarker identification is key to improving patient

management and therapeutic efficacy (48,57).

The present findings position SOX5 as a promising biomarker with

clinical relevance. In LUAD, a high AUC value (0.916) highlights

its diagnostic accuracy, suggesting potential utility for early

detection. This supports the notion that SOX5 serves a role in

early tumor formation and progression, making it a good candidate

for early diagnosis, particularly in LUAD, through its expression

profiling.

Notable associations between SOX5 expression and

survival outcomes, including DSS, DFI and PFI, further reinforce

its prognostic value. Variations in SOX5 expression may reflect

differences in tumor invasiveness and therapeutic response, thereby

impacting patient survival and recurrence risk. In LUAD, low SOX5

expression was associated with worse survival rates, potentially

due to its involvement in regulating cell proliferation and

apoptosis pathways. Thus, SOX5 expression represents a key

prognostic indicator to guide clinical decision-making.

Notably, SOX5 appears to influence the TME,

particularly immune evasion mechanisms. The complexity of the TME

markedly affects therapeutic outcomes. SOX5 may modulate the immune

landscape by regulating immune cell infiltration and related

factors, thereby influencing tumor immune surveillance and

treatment response (58). The

observed positive correlation between elevated SOX5 expression and

immune checkpoint levels (PD-L1 and CTLA-4) suggests that SOX5

serves a key immunomodulatory role, potentially facilitating immune

evasion within the TME. ‘SOX5_High’ tumors exhibited activated yet

exhausted immune features (including increased immune infiltration,

immune scores and TMB, especially in LUAD and UCEC), suggesting

SOX5 coordinates both immune recognition and immunosuppressive

checkpoint expression.

These findings position SOX5 as a promising

predictive biomarker for immune checkpoint blockade (ICB)

responsiveness. Patients with high SOX5 expression may benefit more

from ICB due to pre-existing checkpoint enrichment. Moreover,

targeting SOX5 could enhance ICB efficacy by reducing intrinsic

immunosuppression. Future work should aim to validate the

mechanistic regulation of immune checkpoints SOX5 may exhibit and

associate its expression with clinical ICB outcomes.

Analysis using ESTIMATE and CIBERSORT demonstrated

that elevated SOX5 expression is associated with an activated TME

and high immune scores, particularly in LUAD and UCEC and is

associated with high TMB. SOX5 may regulate the TME through

multiple mechanisms, influencing immune cell recruitment,

activation and immune escape. Elevated SOX5 could enhance secretion

of cytokines and chemokines, recruiting immune cells such as T

cells and macrophages. While such infiltration could support

antitumor immunity, it may also promote immune escape by recruiting

immunosuppressive cells. SOX5 may also regulate immune cell

activity by modulating the expression of cell surface molecules

such as MHC proteins or immune checkpoint ligands (such as PD-L1),

directly affecting T cell activation and inhibition.

The correlation between SOX5 expression and TMB

suggests an association with tumor genetic complexity and

neoantigen production. As high TMB often predicts improved

immunotherapy responses, SOX5 may influence sensitivity to

immunotherapy through TMB modulation.

The present study also revealed therapeutic

implications of SOX5 expression. Pharmacogenomic analyses showed

high SOX5 expression correlates with increased sensitivity to

various chemotherapeutics, including azacitidine and betulinic

acid. This aligns with the regulation of DNA methyltransferase 1

(DNMT1)/p21 signaling in bladder cancer progression exhibited by

SOX5(48) and suggests that

SOX5-overexpressing tumors may be particularly susceptible to DNMT1

inhibitor therapies. Furthermore, targeting the HuR-lncRNA-SOX5

axis, which stabilizes SOX5 transcripts in carcinomas, could

exploit this therapeutic vulnerability (59). In addition, SOX5 may sensitize

tumor cells to drug-induced apoptosis by regulating cell death

pathways, enhancing cell cycle arrest through p53 activation,

altering cancer cell metabolism and influencing drug transport and

metabolism gene expression (60).

Pan-cancer analysis of SOX5 mutation patterns

indicates that alterations in SOX5, particularly in gastric and

pancreatic cancers, may drive invasion and therapy resistance. Such

mutations could disrupt normal regulatory networks and activate

oncogenic pathways (such as Wnt and Notch), contributing to tumor

progression. While this may confer resistance to conventional

therapies, it offers opportunities for targeted interventions

against specific SOX5 alterations.

Although this study provides a comprehensive

pan-cancer analysis of SOX5, several important limitations should

be acknowledged. First, the research primarily relies on

bioinformatic analyses of public databases such as TCGA, and lacks

validation in large-scale independent cohorts, which may introduce

potential biases or overfitting. For instance, while citation3

developed a prognostic model, it was based solely on TCGA data

without involving multi-center samples, thereby limiting its

clinical applicability. Second, functional experiments were

confined to in vitro cell lines (e.g., A549 and H1299), and

lacked in vivo animal model validation, which is essential

for fully recapitulating the complexity of the tumor

microenvironment. Third, the mechanistic insights remain

insufficient; for example, the specific pathways through which SOX5

regulates immune infiltration or drug sensitivity were not fully

elucidated. Fourth, while the mutation pattern analysis revealed

associations between SOX5 alterations and specific signaling

pathways, it did not account for tumor heterogeneity and subtype

variations, which may affect the generalizability of the findings.

Finally, the drug sensitivity data were based on computational

predictions and lacked pre-clinical experimental support,

necessitating further validation of actual therapeutic

efficacy.

In conclusion, the present pan-cancer analysis

established SOX5 as a context-dependent regulator with dual roles

in tumorigenesis, acting as a tumor suppressor in numerous

epithelial cancers while driving oncogenesis in select

malignancies. The dysregulation of SOX5 is associated with immune

evasion, TME remodeling, genomic instability and patient prognosis.

Functional validation demonstrates the role of SOX5 in enhancing

proliferation, migration and invasion in NSCLC. These findings

position SOX5 as a robust biomarker for cancer diagnosis and

prognosis and a promising therapeutic target, offering a strategic

avenue for precision oncology across diverse tumor types.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported by the Hunan Natural

Science Foundation-Regional Joint Fund (grant no. 2024JJ7601) and

Basic Research Guiding Program of Yueyang City Science and

Technology Bureau 2024(20).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

QY, LO and YT contributed to the conception and

design of the study. Data collection was performed by YT, HD, KT,

SL, QZ, LY, SB and LL. Formal analysis was conducted by YT, HD, KT,

SL, QZ, LY, SB, LL and QY. YT, HD and QY wrote the original draft

of the manuscript. The manuscript was reviewed and edited by YT,

HD, KT, QZ, LO, QY and SB. LL, SB, LO and QY supervised the study.

YT, HD, KT, QZ, SL, LL and QY confirm the authenticity of all the

raw data. All authors have read and approved the final version of

the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Li Q, Wang W, Yang T, Li D, Huang Y, Bai G

and Li Q: LINC00520 up-regulates SOX5 to promote cell proliferation

and invasion by miR-4516 in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Biol

Chem. 403:665–678. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Wu B, Wang X, Yu R and Xue X: CircWHSC1

serves as a prognostic biomarker and promotes malignant progression

of non-small-cell lung cancer via miR-590-5p/SOX5 axis. Environ

Toxicol. 38:2440–2449. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Yuan WM, Fan YG, Cui M, Luo T, Wang YE,

Shu ZJ, Zhao J, Zheng J and Zeng Y: SOX5 regulates cell

proliferation, apoptosis, migration and invasion in KSHV-infected

cells. Virol Sin. 36:449–457. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Hu C, Li Q, Xiang L, Luo Y, Li S, An J, Yu

X, Zhang G, Chen Y, Wang Y and Wang D: Comprehensive pan-cancer

analysis unveils the significant prognostic value and potential

role in immune microenvironment modulation of TRIB3. Comput Struct

Biotechnol J. 23:234–250. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Yu D, Sun R, Shen D, Ge L, Xue T and Cao

Y: Nuclear heme oxygenase-1 improved the hypoxia-mediated

dysfunction of blood-spinal cord barrier via the miR-181c-5p/SOX5

signaling pathway. Neuroreport. 32:112–120. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Liang Q, Chu F, Zhang L, Jiang Y, Li L and

Wu H: circ-LDLRAD3 knockdown reduces cisplatin chemoresistance and

inhibits the development of gastric cancer with cisplatin

resistance through miR-588 enrichment-mediated SOX5 inhibition. Gut

Liver. 17:389–403. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Sadeghi Z, Dodangeh F and Raheb J: SOX2

overlapping transcript (SOX2-OT) enhances the lung cancer

malignancy through interaction with miR-194-5p/SOX5 axis. Iran J

Biotechnol. 21(e3530)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Tenorio-Castano J, Gómez ÁS, Coronado M,

Rodríguez-Martín P, Parra A, Pascual P, Cazalla M, Gallego N, Arias

P, Morales AV, et al: Lamb-Shaffer syndrome: 20 Spanish patients

and literature review expands the view of neurodevelopmental

disorders caused by SOX5 haploinsufficiency. Clin Genet.

104:637–647. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Jing Y, Jiang X, Ji Q, Wu Z, Wang W, Liu

Z, Guillen-Garcia P, Esteban CR, Reddy P, Horvath S, et al:

Genome-wide CRISPR activation screening in senescent cells reveals

SOX5 as a driver and therapeutic target of rejuvenation. Cell Stem

Cell. 30:1452–1471.e10. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Shi L, Zhang H, Sun J, Gao X and Liu C:

CircSEC24A promotes IL-1β-induced apoptosis and inflammation in

chondrocytes by regulating miR-142-5p/SOX5 axis. Biotechnol Appl

Biochem. 69:701–713. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Qiu M, Lu Y, Li J, Gu J, Ji Y, Shao Y,

Kong X and Sun W: Interaction of SOX5 with SOX9 promotes

warfarin-induced aortic valve interstitial cell calcification by

repressing transcriptional activation of LRP6. J Mol Cell Cardiol.

162:81–96. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Chen Z, Shang Y, Zhang X, Duan W, Li J,

Zhu L, Ma L, Xiang X, Jia J, Ji X and Gong S: METTL3 mediates SOX5

m6A methylation in bronchial epithelial cells to attenuate Th2 cell

differentiation in T2 asthma. Heliyon. 10(e28884)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Gu Y, Tang S, Wang Z, Cai L, Lian H, Shen

Y and Zhou Y: A pan-cancer analysis of the prognostic and

immunological role of β-actin (ACTB) in human cancers.

Bioengineered. 12:6166–6185. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Chen R, Zhang C, Cheng Y, Wang S, Lin H

and Zhang H: LncRNA UCC promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition

via the miR-143-3p/SOX5 axis in non-small-cell lung cancer. Lab

Invest. 101:1153–1165. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Li C, Zhang J and Bi Y: Unveiling the

prognostic significance of SOX5 in esophageal squamous cell

carcinoma: A comprehensive bioinformatic and experimental analysis.

Aging (Albany NY). 15:7565–7582. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Innella G, Greco D, Carli D, Magini P,

Giorgio E, Galesi O, Ferrero GB, Romano C, Brusco A and Graziano C:

Clinical spectrum and follow-up in six individuals with

Lamb-Shaffer syndrome (SOX5). Am J Med Genet A. 185:608–613.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Edgerley K, Bryson L, Hanington L, Irving

R, Joss S, Lampe A, Maystadt I, Osio D, Richardson R, Split M, et

al: SOX5: Lamb-Shaffer syndrome-A case series further expanding the

phenotypic spectrum. Am J Med Genet A. 191:1447–1458.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Leek JT, Johnson WE, Parker HS, Jaffe AE

and Storey JD: The sva package for removing batch effects and other

unwanted variation in high-throughput experiments. Bioinformatics.

28:882–883. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Rousseaux S, Debernardi A, Jacquiau B,

Vitte AL, Vesin A, Nagy-Mignotte H, Moro-Sibilot D, Brichon PY,

Lantuejoul S, Hainaut P, et al: Ectopic activation of germline and

placental genes identifies aggressive metastasis-prone lung

cancers. Sci Transl Med. 5(186ra66)2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Okayama H, Kohno T, Ishii Y, Shimada Y,

Shiraishi K, Iwakawa R, Furuta K, Tsuta K, Shibata T, Yamamoto S,

et al: Identification of genes upregulated in ALK-positive and

EGFR/KRAS/ALK-negative lung adenocarcinomas. Cancer Res.

72:100–111. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Der SD, Sykes J, Pintilie M, Zhu CQ,

Strumpf D, Liu N, Jurisica I, Shepherd FA and Tsao MS: Validation

of a histology-independent prognostic gene signature for

early-stage, non-small-cell lung cancer including stage IA

patients. J Thorac Oncol. 9:59–64. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Davis S and Meltzer PS: GEOquery: A bridge

between the gene expression omnibus (GEO) and BioConductor.

Bioinformatics. 23:1846–1847. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Colaprico A, Silva TC, Olsen C, Garofano

L, Cava C, Garolini D, Sabedot TS, Malta TM, Pagnotta SM,

Castiglioni I, et al: TCGAbiolinks: An R/Bioconductor package for

integrative analysis of TCGA data. Nucleic Acids Res.

44(e71)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Liao C and Wang X: TCGAplot: An R package

for integrative pan-cancer analysis and visualization of TCGA

multi-omics data. BMC Bioinformatics. 24(483)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Brune V, Tiacci E, Pfeil I, Döring C,

Eckerle S, van Noesel CJ, Klapper W, Falini B, von Heydebreck A,

Metzler D, et al: Origin and pathogenesis of nodular

lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma as revealed by global gene

expression analysis. J Exp Med. 205:2251–2268. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Suraokar MB, Nunez MI, Diao L, Chow CW,

Kim D, Behrens C, Lin H, Lee S, Raso G, Moran C, et al: Expression

profiling stratifies mesothelioma tumors and signifies deregulation

of spindle checkpoint pathway and microtubule network with

therapeutic implications. Ann Oncol. 25:1184–1192. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Robin X, Turck N, Hainard A, Tiberti N,

Lisacek F, Sanchez JC and Müller M: pROC: An open-source package

for R and S+ to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC Bioinformatics.

12(77)2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Benjamini Y and Hochberg Y: Controlling

the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to

Multiple Testing. J R Statist Soc В. 57:289–300. 1995.

|

|

29

|

Yoshihara K, Shahmoradgoli M, Martínez E,

Vegesna R, Kim H, Torres-Garcia W, Treviño V, Shen H, Laird PW,

Levine DA, et al: Inferring tumour purity and stromal and immune

cell admixture from expression data. Nat Commun.

4(2612)2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Chen B, Khodadoust MS, Liu CL, Newman AM

and Alizadeh AA: Profiling tumor infiltrating immune cells with

CIBERSORT. Methods Mol Biol. 1711:243–259. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Hänzelmann S, Castelo R and Guinney J:

GSVA: Gene set variation analysis for microarray and RNA-seq data.

BMC Bioinformatics. 14(7)2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Maeser D, Gruener RF and Huang RS:

oncoPredict: An R package for predicting in vivo or cancer patient

drug response and biomarkers from cell line screening data. Brief

Bioinform. 22(bbab260)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Mayakonda A, Lin DC, Assenov Y, Plass C

and Koeffler HP: Maftools: Efficient and comprehensive analysis of

somatic variants in cancer. Genome Res. 28:1747–1756.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 25:402–408.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Dong G, Wang X, Wang X, Jia Y, Jia Y, Zhao

W and Tong Z: Circ_0084653 promotes the tumor progression and

immune escape in triple-negative breast cancer via the

deubiquitination of MYC and upregulation of SOX5. Int J Biol

Macromol. 280 (Pt 1)(135655)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Cong L, Zhao Q, Sun H, Zhou Z, Hu Y, Li C,

Hao M and Cong X: A novel long non-coding RNA SLNCR1 promotes

proliferation, migration, and invasion of melanoma via

transcriptionally regulating SOX5. Cell Death Discov.

10(160)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Li Y and Yang S, Qin L and Yang S: TAZ is

required for chondrogenesis and skeletal development. Cell Discov.

7(26)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Medina-Menéndez C, Tirado-Melendro P, Li

L, Rodríguez-Martín P, Melgarejo-de la Peña E, Díaz-García M,

Valdés-Bescós M, López-Sansegundo R and Morales AV: Sox5 controls

the establishment of quiescence in neural stem cells during

postnatal development. PLoS Biol. 23(e3002654)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Tsai CC, Huang MH, Fang CL, Hsieh KL,

Hsieh TH, Ho WL, Chang H, Tsai ML, Kao YC, Miser JS, et al: An

infant-type hemispheric glioma with SOX5::ALK: A novel fusion. J

Natl Compr Canc Netw. 22(e237102)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Sara H, Kallioniemi O and Nees M: A decade

of cancer gene profiling: From molecular portraits to molecular

function. Methods Mol Biol. 576:61–87. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Legge F, Ferrandina G and Scambia G: From

bio-molecular and technology innovations to clinical practice:

Focus on ovarian cancer. Ann Oncol. 17 (Suppl 7):vii46–vii48.

2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Lu DY, Qu RX, Lu TR and Wu HY: Cancer

bioinformatics for updating anticancer drug developments and

personalized therapeutics. Rev Recent Clin Trials. 12:101–110.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Shi Y, Wang Y, Zhang W, Niu K, Mao X, Feng

K and Zhang Y: N6-methyladenosine with immune infiltration and

PD-L1 in hepatocellular carcinoma: Novel perspective to

personalized diagnosis and treatment. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne).

14(1153802)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Chen X, Fu Y, Xu H, Teng P, Xie Q, Zhang

Y, Yan C, Xu Y, Li C, Zhou J, et al: SOX5 predicts poor prognosis

in lung adenocarcinoma and promotes tumor metastasis through

epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Oncotarget. 9:10891–10904.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Ueda R, Yoshida K, Kawase T, Kawakami Y

and Toda M: Preferential expression and frequent IgG responses of a

tumor antigen, SOX5, in glioma patients. Int J Cancer.

120:1704–1711. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Chen M, Zou S, He C, Zhou J, Li S, Shen M,

Cheng R, Wang D, Zou T, Yan X, et al: Transactivation of SOX5 by

Brachyury promotes breast cancer bone metastasis. Carcinogenesis.

41:551–560. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Yang B, Zhang W, Sun D, Wei X, Ding Y, Ma

Y and Wang Z: Downregulation of miR-139-5p promotes prostate cancer

progression through regulation of SOX5. Biomed Pharmacother.

109:2128–2135. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Wu L, Yang Z, Dai G, Fan B, Yuan J, Liu Y,

Liu P and Ou Z: SOX5 promotes cell growth and migration through

modulating the DNMT1/p21 pathway in bladder cancer. Acta Biochim

Biophys Sin (Shanghai). 54:987–998. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Pei XH, Lv XQ and Li HX: SOX5 induces

epithelial to mesenchymal transition by transactivation of Twist1.

Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 46:322–327. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Xue JD, Xiang WF, Cai MQ and Lv XY:

Biological functions and therapeutic potential of SRY related high

mobility group box 5 in human cancer. Front Oncol.

14(1332148)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Docherty AR, Mullins N, Ashley-Koch AE,

Qin X, Coleman JRI, Shabalin A, Kang J, Murnyak B, Wendt F, Adams

M, et al: GWAS meta-analysis of suicide attempt: identification of

12 genome-wide significant loci and implication of genetic risks

for specific health factors. Am J Psychiatry. 180:723–738.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Vinyals A, Ferreres JR, Calbet-Llopart N,

Ramos R, Tell-Martí G, Carrera C, Marcoval J, Puig S, Malvehy J,

Puig-Butillé JA and Fabra À: Oncogenic properties via MAPK

signaling of the SOX5-RAF1 fusion gene identified in a wild-type

NRAS/BRAF giant congenital nevus. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res.

35:450–460. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Collins FL, Roelofs AJ, Symons RA, Kania

K, Campbell E, Collie-Duguid ESR, Riemen AHK, Clark SM and De Bari

C: Taxonomy of fibroblasts and progenitors in the synovial joint at

single-cell resolution. Ann Rheum Dis. 82:428–437. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Sridharan S and Basu A: Distinct roles of

mTOR targets S6K1 and S6K2 in breast cancer. Int J Mol Sc.

21(1199)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Blanco L and Tirado CA: Testicular germ

cell tumors: A cytogenomic update. J Assoc Genet Technol.

44:128–133. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Mostert MC, Verkerk AJ, van de Pol M,

Heighway J, Marynen P, Rosenberg C, van Kessel AG, van Echten J, de

Jong B, Oosterhuis JW and Looijenga LH: Identification of the

critical region of 12p over-representation in testicular germ cell

tumors of adolescents and adults. Oncogene. 16:2617–2627.

1998.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Cai Y and Jia Y: Circular RNA SOX5

promotes the proliferation and inhibits the apoptosis of the

hepatocellular carcinoma cells by targeting miR-502-5p/synoviolin 1

axis. Bioengineered. 13:3362–3370. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Knights AJ, Farrell EC, Ellis OM, Lammlin

L, Junginger LM, Rzeczycki PM, Bergman RF, Pervez R, Cruz M, Knight

E, et al: Synovial fibroblasts assume distinct functional

identities and secrete R-spondin 2 in osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum

Dis. 82:272–282. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Wang L, Ye S, Wang J, Gu Z, Zhang Y, Zhang

C and Ma X: HuR stabilizes lnc-SOX5 mRNA to promote tongue

carcinogenesis. Biochemistry (Mosc). 82:438–445. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Li QS, Shabalin AA, DiBlasi E, Gopal S and

Canuso CM: FinnGen, International Suicide Genetics Consortium.

Palotie A, Drevets WC, Docherty AR and Coon H: Genome-wide

association study meta-analysis of suicide death and suicidal

behavior. Mol Psychiatry. 28:891–900. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|