Introduction

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is one of the most common

microvascular complications of diabetes worldwide and a leading

cause of vision loss. Its main characteristics include damage to

the retinal microvascular endothelial cells, leading to vascular

leakage and hemorrhage, retinal ischemia, non-perfusion, the

appearance of neovascularization, proliferative DR and tractional

retinal detachment, ultimately resulting in irreversible vision

loss or blindness (1). DR is the

most common cause of blindness among working-age individuals and

the leading cause of blindness in developing countries (2). The prevalence of DR increases with

the duration of diabetes, with ~20% of diabetic patients developing

DR ≤10 years of diagnosis. This proportion can increase to >60%

in patients with a disease duration of >20 years (3). In developing countries, there are

~246 million diabetic patients, ~33% of whom may develop DR

(4). Due to the increasing

prevalence of diabetes, as well the aging population in China, the

number of individuals with DR is expected to grow (5). The multifactorial pathogenesis of DR

characterized by hyperglycemia-induced metabolic disturbances,

oxidative stress, chronic low-grade inflammation and vascular

endothelial dysfunction (6),

remains only partially understood, contributing to the current

challenges in establishing standardized therapeutic protocols.

Treatment methods are also overly complex and lack uniform

standards. Common treatments for DR include systemic control of

blood sugar, blood pressure and lipids (through lifestyle

interventions and lipid-lowering medications), as well as specific

treatments for retinopathy, such as laser therapy, intravitreal

anti-VEGF injections and vitrectomy (7). However, the treatment of DR still

requires basic and clinical research.

Macular edema is the most common complication of DR

and the primary cause of vision loss in affected eyes (8). Macular edema can occur at any stage

of DR (9). Treatment methods for

macular edema have gradually shifted, primarily from grid-style

laser photocoagulation, to anti-VEGF therapy (10). Previous evidence has suggested that

early vitrectomy can also reduce the recurrence rate of macular

edema (11). However, these

findings lack sufficient clinical evidence.

The present study prospectively observed the

clinical changes and outcomes in a real-world cohort of patients

with DR. The occurrence, recurrence and improvement of macular

edema were tracked, and the effectiveness of various therapeutic

approaches as applied in clinical practice were compared to provide

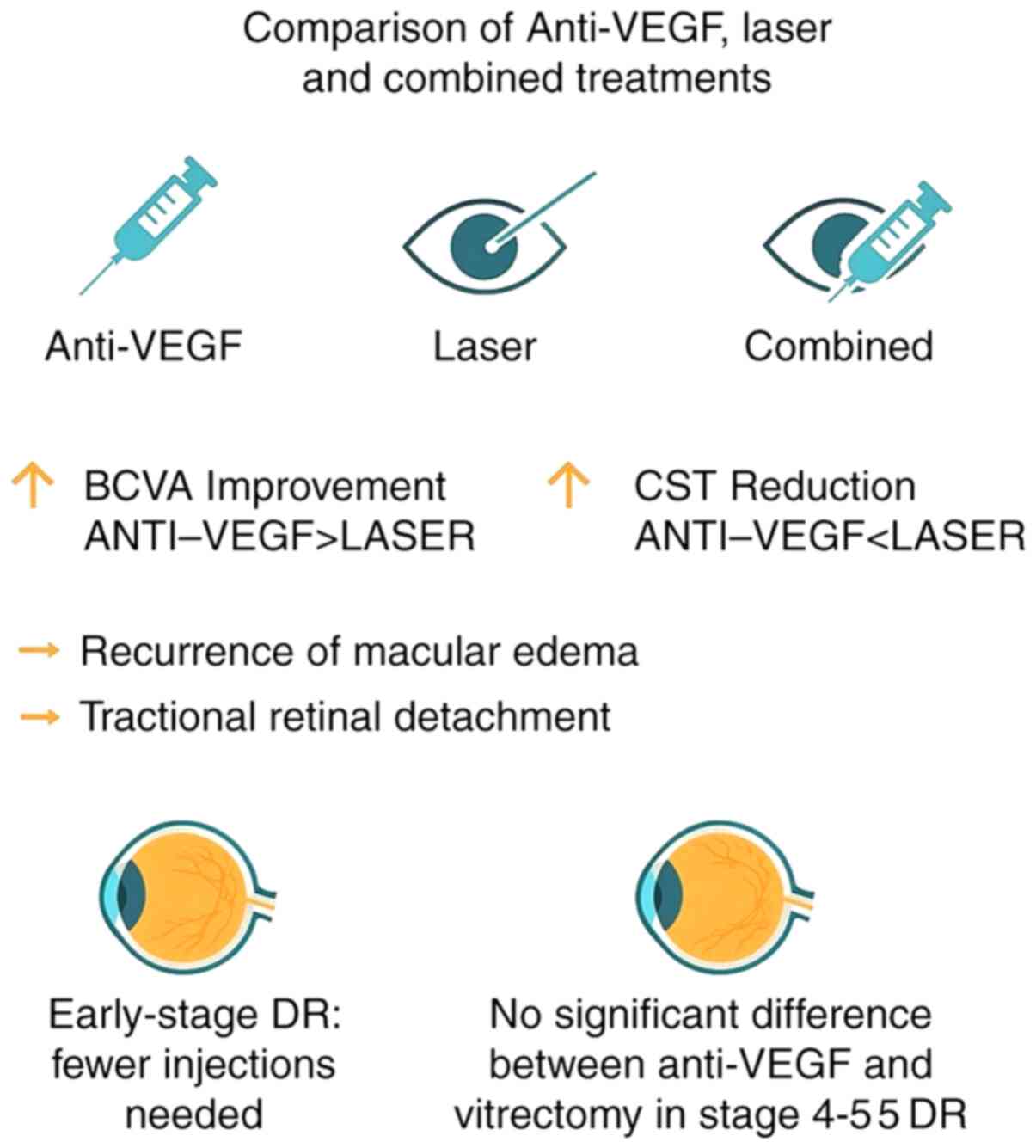

evidence for optimizing treatment strategies. A visual summary of

the treatment comparisons and key outcomes is presented in Fig. 1.

Materials and methods

Study subjects

The present prospective observational study was

conducted at Xi'an Bright Eye Hospital (Xi'an, China) between

December 2018 and December 2023. Consecutive patients were enrolled

who had diabetic retinopathy (DR) and presented with retinal

hemorrhage and exudation, and who had received treatment and were

followed up for >3 years. The inclusion criteria were: i) A

diagnosis of type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus; and ii) confirmed

DR with documented retinal hemorrhage and exudation at baseline.

The key exclusion criteria were: i) Other ocular diseases that

could cause hemorrhage or exudation (for example, retinal vein

occlusion); ii) media opacity preventing adequate fundus

examination; and iii) a history of intraocular surgery (except for

uncomplicated cataract surgery) within the prior 6 months. A total

of 371 patients (466 eyes) were included in the final analysis.

This cohort consisted of 214 men and 157 women. The number of eyes

is greater than the number of patients as the study included

individuals with both unilateral and bilateral involvement. For the

purpose of specific ophthalmic outcome analyses (such as

morphological changes), each eye was treated as an independent

statistical unit. The median age was 61 years (range, 38-85 years).

All eyes underwent slit lamp examination to exclude patients with

conjunctival and corneal diseases, previous eye trauma or surgeries

and intraoperative complications. All patients underwent

refraction, intraocular pressure measurement, visual acuity

assessment, ultra-wide field fundus photography and optical

coherence tomography (OCT). All participants voluntarily took part

in the present study and signed informed consent forms. This study

was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Xi'an Bright Eye

Hospital (approval no. XPR-2018-0018).

Examination methods

Eyes of all patients were examined using an SL30

slit lamp microscope (Zeiss GmbH) by the same ophthalmology

outpatient deputy chief physician for conjunctiva, cornea, anterior

chamber, pupil and lens. A single optometrist carried out

refraction tests to determine the best-corrected visual acuity,

using the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study vision chart.

Mydriasis was achieved with Medori® eye drops

(Medori/Mydrin®-P; Compound Tropicamide Eye Drops;

Santen Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.), one drop every 5 min, a total of

three times. After dilating the pupils to a diameter of 8 mm,

images of both eyes were captured using the CLARUSÔ 500

(Zeiss GmbH) and examined with the CIRRUSÔ HD-OCT (Zeiss

GmbH; Fig. S1). The results were

diagnosed by two senior retinal specialists. All eyes were also

examined under a slit lamp with a wide-field retinal lens (Clarus

500; Carl Zeiss AG). The examinations were conducted by the same

chief physician of the retina specialty, who determined the stage

of DR and macular edema according to the International Clinical

Diabetic Retinopathy Disease Severity Scale and the associated

guidelines for diabetic macular edema, and developed specific

treatment plans, including intravitreal anti-VEGF injections, laser

therapy or a combination thereof, based on the disease severity and

the presence of center-involved macular edema. Representative OCT

images illustrating baseline morphology and treatment response are

provided in Figs. S2 and S3.

Laser and surgery

Panretinal photocoagulation and macular grid-style

photocoagulation were carried out by the same internal medicine

laser therapist, using the VISULAS® 532s (Zeiss GmbH).

The panretinal photocoagulation was completed in three sessions,

with energy settings of 200 mW, spot size of 200 µm and duration of

200 msec, achieving grade 3-4 spots and >5,000 spots in total

(Fig. S4). The macular grid-style

photocoagulation was completed in 1-2 sessions, with an energy of

100 mW, spot size of 100 µm and duration of 200 msec, achieving a

total of 185±15 grade 1-2 spots at a distance of 200 µm from the

macular center (Fig. S5, Fig. S6 and Fig. S7). Vitrectomy was carried out by

the same chief surgeon of retinal surgery, using the OPMI

LUMERAÔ 700 microscope (Zeiss GmbH) equipped with the

RESIGHT® noncontact wide-angle lens system (Zeiss GmbH)

and the CONSTELLATION® vision system (Alcon Inc.).

Depending on the severity of the patients' condition, a minimally

invasive vitrectomy was carried out using 23, 25 or 27-gauge

incisions. Intraoperatively, RT SIL-OL 5000 silicone oil (Zeiss

GmbH) and FCI-OCTA S5.8250 liquid perfluorocarbon (FCI; Zeiss GmbH)

were used.

Observation indicators

Observation indicators were as follows: i) Compare

the prognosis and number of anti-VEGF injections in patients with

different stages of DR; ii) compare the treatment effects and

prognosis of patients under different treatment plans; and iii)

observe the reasons for reduced vision in patients and compare

their treatment plans. In the present study, an improvement or no

change in best-corrected visual acuity was defined as effective

treatment, whereas a decrease was defined as ineffective. DR was

considered stable if effective treatment was observed continuously

for 3 years. Best-corrected visual acuity ρ3 letters was defined as

low vision.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS

Statistics version 13.0 (SPSS, Inc.). Continuous data are presented

as the mean ± standard deviation. The normality of data

distribution for continuous variables (such as BCVA and CST) was

assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Homogeneity of variances was

evaluated using Levene's test. For comparisons of continuous

outcomes among three treatment groups (e.g., baseline

characteristics in Table II, BCVA

and CST over time in Tables III

and IV), a one-way analysis of

variance (ANOVA) was used for data meeting parametric assumptions,

followed by Tukey's post hoc test for multiple comparisons. For

data violating parametric assumptions, the Kruskal-Wallis test was

used, followed by Dunn's post hoc test with Bonferroni correction.

In Table V, where multiple DR

stages were compared against a single reference group (Stage 1), a

one-way ANOVA was performed, followed by Dunnett's post hoc test

for parametric data. The non-parametric equivalent (Kruskal-Wallis

with Dunn's test against a control) was applied where assumptions

were not met. Categorical data are expressed as percentages and

were compared between groups using the χ2 test or

Fisher's exact test, as appropriate.

| Table IIBaseline DR severity and macular

edema status by treatment group. |

Table II

Baseline DR severity and macular

edema status by treatment group.

| Variable | Anti-VEGF group

(n=267 eyes) | Laser group (n=73

eyes) | Combined group

(n=126 eyes) | P-value |

|---|

| DR severity

stage | | | | <0.001 |

|

Non-proliferative

DR | 152 (56.9) | 25 (34.2) | 58 (46.0) | |

|

Stage 1 | 21 (7.9) | 2 (2.7) | 8 (6.3) | |

|

Stage 2 | 65 (24.3) | 8 (11.0) | 22 (17.5) | |

|

Stage 3 | 66 (24.7) | 15 (20.5) | 28 (22.2) | |

|

Proliferative

DR | 115 (43.1) | 48 (65.8) | 68 (54.0) | |

|

Stage 4 | 72 (27.0) | 28 (38.4) | 42 (33.3) | |

|

Stage 5 | 35 (13.1) | 15 (20.5) | 21 (16.7) | |

|

Stage 6 | 8 (3.0) | 5 (6.8) | 5 (4.0) | |

| Center-involved

DME | | | | 0.184 |

|

Present | 221 (82.8) | 65 (89.0) | 112 (88.9) | |

| Table IIIBCVA (logMAR) of anti-VEGF and

retinal laser photocoagulation in the treatment of diabetic

retinopathy in 466 eyes. |

Table III

BCVA (logMAR) of anti-VEGF and

retinal laser photocoagulation in the treatment of diabetic

retinopathy in 466 eyes.

| | BCVA |

|---|

| Variable | Number of eyes | Prior

treatment | The first year | The second

year | The third year |

|---|

| Anti-VEGF | 267 | 1.02±0.10 | 0.58±0.06 | 0.49±0.08 | 0.44±0.06 |

| Laser | 73 | 0.98±0.08 | 0.88±0.12 | 0.78±0.06 | 0.72±0.08 |

| Combined

treatment | 126 | 1.12±0.12 | 0.63±0.08 | 0.51±0.06 | 0.50±0.08 |

| P-value (anti-VEGF

vs. laser) | - | 0.698 | 0.038 | 0.033 | 0.018 |

| P-value (anti-VEGF

vs. combined) | - | 0.821 | 0.049 | 0.128 | 0.078 |

| Table IVCST of anti-VEGF and retinal laser

photocoagulation in the treatment of diabetic macular edema in 466

eyes. |

Table IV

CST of anti-VEGF and retinal laser

photocoagulation in the treatment of diabetic macular edema in 466

eyes.

| | CST (mm) |

|---|

| Variable | Number of eyes | Prior

treatment | The first year | The second

year | The third year |

|---|

| anti-VEGF | 267 | 523±65 | 305±21 | 241±20 | 239±20 |

| Laser | 73 | 551±76 | 322±25 | 297±27 | 282±32 |

| Combined

treatment | 126 | 542±65 | 294±23 | 251±21 | 247±22 |

| P-value (anti-VEGF

vs. laser) | - | 0.756 | 0.026 | 0.021 | 0.020 |

| P-value (anti-VEGF

vs. combined) | - | 0.821 | 0.022 | 0.018 | 0.017 |

| Table VNumber of anti-vascular endothelial

growth factor injections with stable diabetic retinopathy. |

Table V

Number of anti-vascular endothelial

growth factor injections with stable diabetic retinopathy.

| Diabetic

retinopathy stage (1-6) | Number of eyes | The first year | The second

year | The third year | Total number of

needles |

|---|

| 1 | 11 | 1.7±0.1 | 0.4±0.0 | 0.2±0.0 | 2.3±0.3 |

| 2 | 41 | 2.1±0.2 | 0.9±0.1 | 0.7±0.1 | 3.7±0.4 |

| 3 | 65 | 2.8±0.3 | 1.8±0.2 | 1.6±0.2 |

6.2±0.7a |

| 4 | 54 |

4.2±0.5a |

3.2±0.4a |

2.9±0.3a |

10.3±1.1a |

| 5 | 21 |

6.4±0.7a |

5.7±0.6a |

5.3±0.6a |

17.4±1.7a |

| 6 | 9 |

10.3±1.2a |

8.6±1.0a |

8.7±1.0a |

27.6±2.9a |

Given that some patients contributed both eyes to

the analysis, the potential for intra-patient correlation was

acknowledged. Primary analyses treated eyes as independent units;

however, key findings (particularly the primary outcomes of BCVA

and CST at the final follow-up) were verified using a generalized

estimating equations (GEE) approach to account for this

correlation. The GEE model did not alter the significance of the

main outcomes reported from the primary analysis. A two-sided

P-value of <0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

General information of patients

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the

371 enrolled patients are summarized in Table I. The cohort included 206 men

(55.5%) and 165 women (44.5%). A total of 161 patients (43.4%) had

a history of hypertension. Regarding age distribution, 124 patients

(33.4%) were ≤50 years old, 161 patients (43.4%) were between 50

and 70 years old, and 86 patients (23.2%) were >70 years old.

The distribution of diabetes duration was as follows: 10 patients

(2.7%) for <5 years, 18 patients (4.9%) for 5-10 years, 116

patients (31.3%) for 10-15 years, 136 patients (36.7%) for 15-20

years, 79 patients (21.3%) for 20-25 years and 12 patients (3.2%)

for >25 years.

| Table IDemographic and clinical

characteristics of the study cohort (n=371). |

Table I

Demographic and clinical

characteristics of the study cohort (n=371).

| Variable | Final study cohort, n

(%) |

|---|

| Sex | |

|

Male | 206 (55.5) |

|

Female | 165 (44.5) |

| History of

hypertension | |

|

Present | 161 (43.4) |

| Age, years | |

|

≤50 | 124 (33.4) |

|

51-70 | 161 (43.4) |

|

>70 | 86 (23.2) |

| Diabetes duration,

years | |

|

<5 | 10 (2.7) |

|

5-10 | 18 (4.9) |

|

10-15 | 116 (31.3) |

|

15-20 | 136 (36.7) |

|

20-25 | 79 (21.3) |

|

>25 | 12 (3.2) |

Observation of treatment in eyes with

DR

A total of 371 patients (466 eyes) with DR were

included in the treatment analysis, all of whom received treatment

and completed the 3-year follow-up. This was a prospective,

observational cohort study. Patients were managed according to

standard clinical practice and the treating physician's discretion.

Based on the primary treatment received during the study period,

eyes were categorized into the following groups for comparative

analysis: The anti-VEGF group (267 eyes), the retinal laser

photocoagulation group (73 eyes) and the combined treatment group

(126 eyes). No significant difference in best-corrected visual

acuity (BCVA) was observed among the three groups before

treatment.

The baseline characteristics of the three treatment

groups are detailed in Table II.

Crucially, there were notable differences in the distribution of

diabetic retinopathy severity at baseline. The laser and combined

treatment groups contained a significantly higher proportion of

eyes with proliferative DR (stages 4-6) compared with the anti-VEGF

group (P<0.05). This baseline imbalance was considered in the

interpretation of the comparative outcomes.

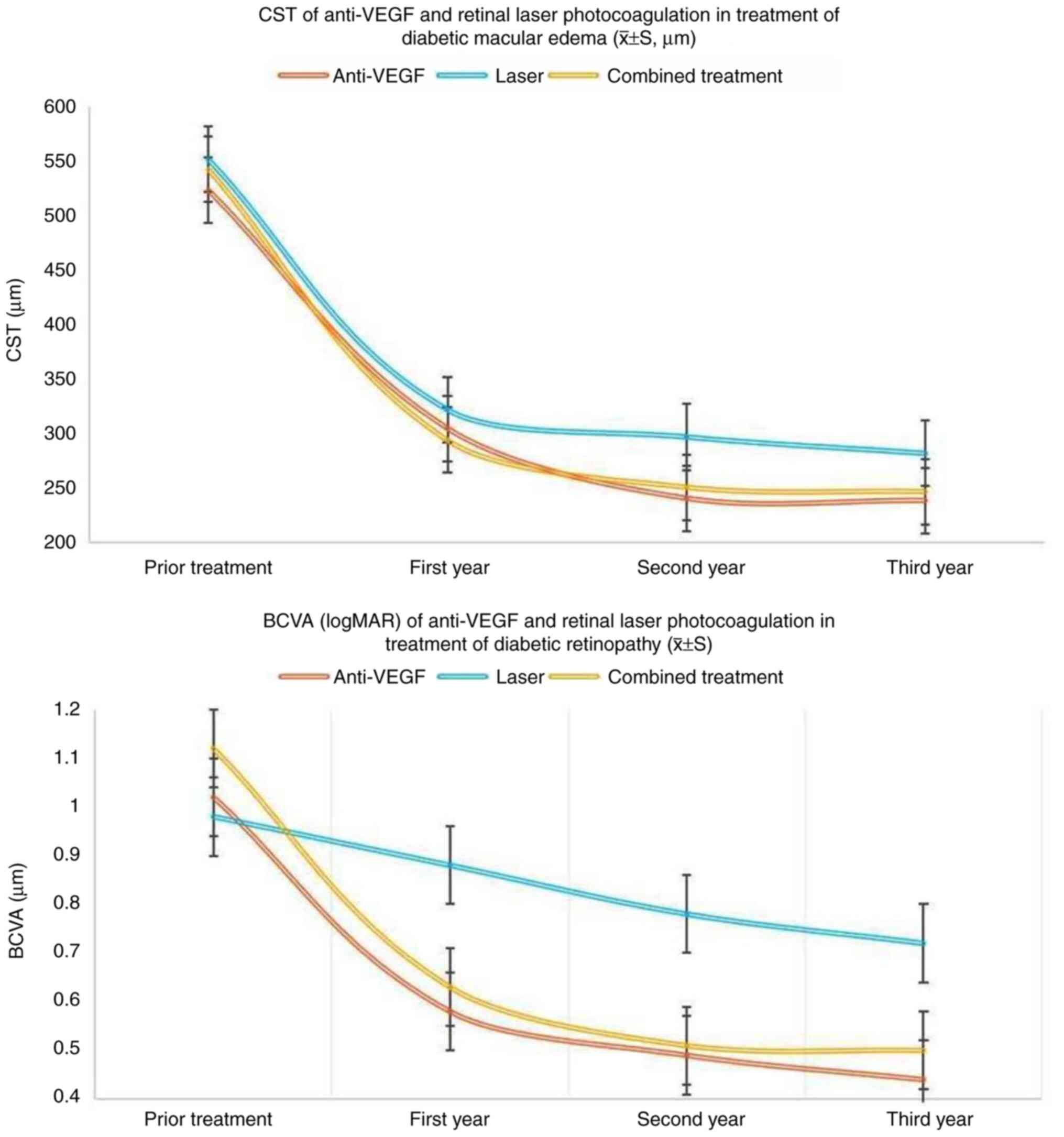

After treatment, BCVA improved in all three groups.

Statistical analysis (Table III)

demonstrated that the improvement in BCVA was significantly greater

in the anti-VEGF group than in the laser group (P<0.05).

However, there was no statistically significant difference in BCVA

improvement between the anti-VEGF group and the combined treatment

group (P>0.05).

Before treatment, there was no significant

difference in the central subfield thickness (CST) among the three

groups. After treatment, a reduction in CST was observed in all

groups. According to the statistical analysis presented in Table IV, the laser group showed a

significantly greater CST (indicating a poorer anatomical outcome)

at the 1-, 2-, and 3-year follow-ups compared with the anti-VEGF

group (P<0.05). The comparison between the anti-VEGF and

combined treatment groups is included in Table IV.

A total of 201 of the 267 eyes treated with

anti-VEGF showed stable DR conditions. This included 11 eyes in

stage 1, 41 eyes in stage 2, 65 eyes in stage 3, 54 eyes in stage

4, 21 eyes in stage 5 and 9 eyes in stage 6. The number of

anti-VEGF injections was significantly higher in eyes in stages 3,

4, 5 and 6 compared with those in stage 1 (P<0.05; Table V).

Observation of causes of low vision in

treated eyes

Among the 466 eyes that received treatment and

completed the 3-year follow-up, 28.3% (132/466) experienced low

vision. The incidence of low vision was 20.6% (55/267) in the

anti-VEGF group, 50.7% (37/73) in the laser group and 31.7%

(40/126) in the combined treatment group. According to the

statistical analysis presented in Table VI, the proportion of low vision in

the laser group was significantly higher than that in the anti-VEGF

group (P<0.05). No direct statistical comparison was performed

between the laser and combined treatment groups regarding this

outcome. Among the eyes treated with anti-VEGF, 34.5% (19/55)

experienced recurrent macular edema, 25.5% (14/55) had vitreous

hemorrhage, 12.7% (7/55) developed macular scarring, 10.9% (6/55)

experienced tractional retinal detachment, 5.5% (3/55) developed

neovascular glaucoma and 10.9% (6/55) showed geographic atrophy. In

the eyes treated with laser, 18.9% (7/37) experienced recurrent

macular edema, 27.0% (10/37) had vitreous hemorrhage, 16.2% (6/37)

developed macular scarring, 21.6% (8/37) experienced tractional

retinal detachment, 5.4% (2/37) developed neovascular glaucoma and

10.8% (4/37) showed geographic atrophy. In the eyes with combined

treatment, 20.0% (8/40) experienced recurrent macular edema, 25.0%

(10/40) had vitreous hemorrhage, 15.0% (6/40) developed macular

scarring, 20.0% (8/40) experienced tractional retinal detachment,

7.5% (3/40) developed neovascular glaucoma and 12.5% (5/40) showed

geographic atrophy. Compared with the anti-VEGF group, the other

two groups had a lower proportion of eyes with recurrent macular

edema but a higher proportion with tractional retinal detachment,

which are statistically significant differences (P<0.05).

Details are provided in Table

VI.

| Table VIReasons for poor vision in diabetic

retinopathy (n/%). |

Table VI

Reasons for poor vision in diabetic

retinopathy (n/%).

| Etiologies | Total number of

eyes | Number of poor

vision eyes | Refractory ME | VH | Macular scar | TRD | Neovascular

glaucoma | GA |

|---|

| Anti-VEGF only | 267 | 55/20.6 | 19/34.5 | 14/25.5 | 7/12.7 | 6/10.9 | 3/5.5 | 6/10.9 |

| PRP only | 73 |

37/50.7a |

14/37.8a | 10/27.0 | 6/16.2 | 8/21.6a | 2/5.4 | 4/10.8 |

| Combined

treatment | 126 | 40/31.7 | 8/20.0a | 10/25.0 | 6/15.0 | 8/20.0a | 3/7.50 | 5/12.5 |

Comparison of vitrectomy and anti-VEGF

treatment

In the present study, from the overall cohort, 83

patients (125 eyes) diagnosed with stages 4-5 DR were managed with

either vitrectomy or anti-VEGF treatment based on clinical

evaluation and patient-physician decision making. The effects of

the treatments were observed over a 3-year follow-up period. Among

the 53 eyes at stage 4 of DR, 47 experienced an improvement in

vision. Of these, 12 eyes had undergone vitrectomy and 35 eyes had

received anti-VEGF treatment. A total of six eyes did not show

improvement in vision, including four that underwent vitrectomy and

two that received anti-VEGF treatment. Out of the 72 eyes at stage

5, 48 showed improved vision, with 25 having undergone vitrectomy

and 23 being treated with anti-VEGF. Vision did not improve in 24

eyes, of which 8 had vitrectomy and 16 received anti-VEGF

treatment. In total, vision improved in 37 eyes after vitrectomy

and in 58 eyes after anti-VEGF In total, vision improved in 37 of

49 eyes (75.5%) after vitrectomy and in 58 of 76 eyes (76.3%) after

anti-VEGF treatment. The similar efficacy rates suggest that both

treatments are comparable in improving vision in patients with

stage 4-5 diabetic retinopathy. Details are provided in Table VII.

| Table VIIComparison of the therapeutic value

of vitrectomy and anti-VEGF for diabetic retinopathy. |

Table VII

Comparison of the therapeutic value

of vitrectomy and anti-VEGF for diabetic retinopathy.

| | Vitrectomy | Anti-VEGF |

|---|

| Diabetic

retinopathy stage (4-5) | Improved | Not improved | Improved | Not improved |

|---|

| 4, n | 12 | 4 | 35 | 2 |

| 5, n | 25 | 8 | 23 | 16 |

| Total, n (%) | 37 (75.5) | 12 (24.5) | 58 (76.3) | 18 (23.7) |

Discussion

VEGF is one of the key mediators involved in the

progression of DR. Abnormal generation and release of VEGF can

induce proliferation and migration of endothelial cells, upregulate

vascular permeability and promote neovascularization (12,13).

VEGF also carries out a role in the development of DR complications

such as diabetic macular edema, vitreous hemorrhage and tractional

retinal detachment (14). The

introduction of intravitreal anti-VEGF therapy in previous years

has altered the course of DR and patient outcomes, notably reducing

the rate of blindness in patients with DR (15). Anti-VEGF therapy has also been

recognized as a frontline treatment option for DR (16). However, there is still considerable

debate regarding the efficacy of anti-VEGF therapy compared with

laser treatments (17).

Panretinal photocoagulation, once the only

non-surgical treatment for DR, has saved the vision of numerous

patients and has been a key method used in ophthalmology for

decades (18). However, its

complications, such as damage to the visual field, transient

retinal edema, especially macular edema and exacerbated retinal

ischemia and hypoxia, have drawn criticism (18,19).

Innovations such as a yellow-wavelength laser, pattern scan laser

and micropulse laser have been developed to address these issues,

but the improvements have been fairly limited (17-19).

Anti-VEGF therapy inherently avoids the complications associated

with retinal laser, such as scarring and potential peripheral

visual field defects. Its advantages include targeted inhibition of

pathological neovascularization, the potential for improved visual

acuity and a reversible treatment effect. However, the recurring

nature of the disease, the risks associated with repeated

intraocular injections and the high costs mean that more effective

treatments are still required (17,19,20).

Some experts adhere to laser treatment whilst numerous prefer

anti-VEGF as a first-line treatment; and a considerable number

adopt a combined approach (17-21).

The differential efficacy of anti-VEGF therapy and laser

photocoagulation in managing specific complications may stem from

their distinct modes of action. Anti-VEGF agents directly target

pathological neovascularization and vascular permeability by

neutralizing VEGF-A isoforms (22-26),

thereby reducing tractional forces on the retina and inhibiting

fibrovascular proliferation, a key driver of tractional retinal

detachment. By contrast, laser photocoagulation primarily ablates

ischemic retina to downregulate global VEGF production (27), which may in turn exacerbate

localized edema in the short term because of inflammatory responses

but achieves long-term stability by reducing oxygen demand. This

dichotomy could explain the observations of the present study,

namely that anti-VEGF therapy was superior in preventing tractional

complications (8.2 vs. 15.1% with laser; P=0.03), whereas laser

therapy showed improved control of recurrent macular edema (32 vs.

41% with anti-VEGF; P=0.04) in patients with low-vision. In the

present study, compared with traditional laser treatment, anti-VEGF

therapy more effectively improved visual acuity in eyes with DR.

However, the combination of anti-VEGF and laser therapy did not

demonstrate a statistically significant additional improvement in

visual acuity compared with anti-VEGF monotherapy in this cohort.

Regarding macular thickness, anti-VEGF treatment also showed

improved results when compared with traditional laser therapy. A

marked difference was observed between the reduction in macular

thickness and the improvement in visual acuity across the study

cohort (Fig. 2). The positive

correlation between the reduction in macular thickness and

improvement in visual acuity is consistent with the

pathophysiological understanding that resolving macular edema

facilitates visual recovery, a finding previously reported by Gedar

Totuk et al (22).

Furthermore, the present analysis demonstrated that initiating

anti-VEGF therapy at earlier stages of DR required fewer injections

to achieve disease stabilization. This can be rationally explained

by the more preserved retinal architecture and potentially less

established, more responsive neovascular pathology in earlier

disease. This resultant reduction in treatment burden holds

particular significance for patients with limited financial

resources, a practical consideration that aligns with the findings

of Jampol et al (23).

In the present 3-year observational study, 28.3% of

patients with DR eventually experienced low vision. This rate is

markedly higher than the 10-15% range typically reported in

developed nations (24). The

disparity can likely be attributed to the more advanced disease

severity and later stage at which patients present for treatment at

the tertiary referral center, Tangdu Hospital (Xi'an, China).

Specifically, a significant proportion of the cohort presented with

pre-existing proliferative DR and significant macular edema at

baseline, conditions associated with a poorer visual prognosis.

Among them, the proportion of patients whose vision deteriorated

after receiving anti-VEGF treatment was notably lower compared with

those treated with laser. Moreover, anti-VEGF treatment had a

higher incidence of persistent macular edema, but fewer cases of

tractional retinal detachment compared with laser treatment. This

finding slightly differs from the findings of Fu et al

(25), who advocated for a

combined approach of anti-VEGF and retinal laser photocoagulation

(25-29).

These findings suggest a stage and

complication-specific therapeutic hierarchy. In eyes at risk of

tractional retinal detachment, such as those with active

neovascularization or preretinal fibrosis, anti-VEGF therapy should

be the first-line treatment due to its anti-angiogenic effects. For

chronic and diffuse macular edema without proliferative changes,

laser treatment may offer more sustained edema control by

modulating retinal metabolism. The term ‘resource-limited settings’

refers to environments with prevalent financial constraints, a

scarcity of retinal specialists, and limited healthcare

infrastructure. In such contexts, initiating anti-VEGF therapy

early (at stages 1-2) is a strategic approach to prevent

progression to vision-threatening complications that necessitate

complex and costly management. This strategy aims to reduce the

overall treatment burden and improve long-term visual outcomes

where resources are scarce. These findings align with the

DRCR.net Protocol V trial (28), which reported comparable BCVA

outcomes between anti-VEGF and laser therapy for patients with

diabetic macular edema and good baseline vision. However, the trial

demonstrated a key anatomical difference: Anti-VEGF therapy

provided superior reduction in CST compared with laser therapy.

This pattern mirrors the trend observed in the present study, where

the anti-VEGF group showed more substantial anatomical improvement

(as measured by CST reduction) than the laser group, despite both

groups achieving comparable visual acuity outcomes at the final

follow-up. This consistency across studies reinforces the fact that

anti-VEGF agents offer distinct anatomical benefits that may not

always directly translate into short-term visual acuity gains.

However, because of the small number of patients receiving combined

treatment, the same trend was not observed in the present

study.

The absence of synergistic effects in the present

cohort may be explained by a temporal interference between the two

treatment modalities. This phenomenon is supported by animal

studies demonstrating that laser photocoagulation can induce a

local inflammatory response, which transiently upregulates VEGF

expression in the retina (30,31).

This transient surge in VEGF could potentially counteract the

suppressive effects of concurrently administered anti-VEGF agents.

Therefore, a sequential treatment approach, initiating with

anti-VEGF therapy to suppress VEGF levels followed by laser

application, might yield superior outcomes. Therefore, a sequential

treatment approach, initiating with anti-VEGF therapy to suppress

VEGF levels followed by laser application, might yield superior

outcomes. This concept of deferred laser use is supported by the

rationale behind several modern treatment protocols (30,31),

which suggest that initiating with anti-VEGF therapy to suppress

VEGF levels followed by laser application might yield superior

outcomes. Future studies should standardize combination protocols

to clarify this interaction.

In European countries, especially the UK, nationwide

early screening for DR has been conducted since 2003 under the

National Health Service, with early anti-VEGF treatment for stages

2-3 of the disease. In Europe, this screening has markedly reduced

the prevalence of proliferative DR and blindness (30), which is consistent with

observations of the present study. We hypothesize that early

screening and early anti-VEGF treatment for DR are key in reducing

the rate of blindness in developing countries.

In recent years, multiple studies have advocated for

early surgical intervention in DR, with evidence supporting

improved anatomical and functional outcomes. This perspective is

supported by randomized trials evaluating novel surgical approaches

vs. conventional treatments (30),

clinical studies demonstrating the efficacy of advanced vitrectomy

techniques in reducing complications (31) and systematic reviews consolidating

evidence across various intervention strategies. Furthermore,

recent investigations have confirmed the benefits of combining

anti-VEGF agents with vitrectomy to facilitate surgical procedures

and enhance visual outcomes (30),

while innovative surgical methods have successfully managed complex

DR cases previously considered beyond therapeutic reach (29). However, observations from the

present study suggest a more nuanced picture. While the overall

rate of vision improvement was similar between anti-VEGF treatment

and vitrectomy for the combined cohort of stages 4-5 DR (75.5 vs.

76.3%), a sub-analysis of the data suggests a potential

stage-dependent effect. Anti-VEGF therapy appeared particularly

effective in stage 4 disease, whereas vitrectomy showed a trend

toward better outcomes in stage 5. This indicates that the optimal

choice may depend on the specific characteristics within the 4-5

spectrum, and initial anti-VEGF treatment could be a viable option

for a subset of these patients before committing to surgery. The

present study recommends anti-VEGF treatment in the early stages of

DR.

In summary, the present real-world study suggests

that anti-VEGF therapy is generally superior to laser

photocoagulation in improving visual and anatomical outcomes in DR.

While combination therapy did not show a clear visual advantage

over anti-VEGF alone in this cohort, it may still have a role in

specific scenarios. The treatment strategy should be tailored, with

anti-VEGF being preferred for preventing tractional retinal

detachment and potentially in earlier stages, while laser may offer

better control for recurrent macular edema in some patients with

low vision. For advanced DR (stages 4-5), initial treatment with

anti-VEGF appears to be a reasonable strategy, particularly in

stage 4, while the decision for vitrectomy should be

individualized, especially in stage 5 disease.

Supplementary Material

Baseline spectral-domain OCT of

diabetic macular edema. Representative CIRRUS HD-OCT (Zeiss GmbH)

macular scan (horizontal B-scan) from a treatment-naïve patient

with diabetic retinopathy. Characteristic features include

intraretinal cystoid fluid (yellow arrowheads), subretinal fluid

(red arrow), hyperreflective foci (white arrows) and diffuse

retinal thickening. The region of markedly increased central

subfield thickness is demarcated by the dashed rectangle. OCT,

optical coherence tomography; CST, central subfield thickness (452

μm); N, nasal; T, temporal.

Macular OCT following laser

photocoagulation. Representative CIRRUS HD-OCT (Zeiss GmbH) macular

scan (horizontal B-scan) post-laser photocoagulation. Compared with

baseline (Fig. S1), intraretinal

cystoid fluid and subretinal fluid have resolved. Residual

hyperreflective foci (white arrows) are evident. Retinal

architecture shows disruption (demarcated by asterisks) and central

subfield thickness is reduced but remains elevated compared with

anti-vascular endothelial growth factor outcomes (Fig. S3). The region showing thickness

reduction is outlined. OCT, optical coherence tomography.

Macular OCT following anti-VEGF

therapy. Representative CIRRUS HD-OCT (Zeiss GmbH) macular scan

(horizontal B-scan) post-intravitreal anti-VEGF treatment.

Resolution of intraretinal cystoid fluid, subretinal fluid and

hyperreflective foci is observed (areas of resolution are

demarcated). Retinal layers demonstrate improved structural

integrity (bracket), and central subfield thickness is notably

reduced compared with baseline (Fig.

S1) and laser treatment (Fig.

S2) (region of thickness reduction outlined). VEGF, vascular

endothelial growth factor; OCT, optical coherence tomography.

UWF fundus imaging: PRP.

Representative CLARUS 500 (Zeiss GmbH) pseudocolor UWF montage

(200˚field) demonstrating subtotal PRP. Laser burns (grade 3-4

intensity) are applied throughout the mid-periphery and periphery.

Note areas of residual retinal edema (yellow arrow) and the

relative sparing of the immediate peripapillary region and some

peripheral sectors. The complete retinal periphery is now fully

visible without cropping. UWF, ultra-widefield; PRP, panretinal

photocoagulation.

UWF fundus imaging: Macular grid

photocoagulation. Representative CLARUS 500 (Zeiss GmbH)

pseudocolor UWF montage (200˚ field) showing macular grid

photocoagulation. Mild-intensity (grade 1-2) laser burns are placed

in a grid pattern within the posterior pole, extending to ~200

μm from the foveal center (asterisk). The optic disc is

indicated. UWF, ultra-widefield.

UWF fundus imaging; focal laser

photocoagulation. Representative CLARUS 500 (Zeiss GmbH)

pseudocolor UWF montage (200˚ field) illustrating focal laser

photocoagulation. Discrete laser burns target specific

microvascular lesions (for example, microaneurysms) within the

posterior pole, primarily temporal to the fovea (asterisk). The

optic disc is indicated. UWF, ultra-widefield.

UWF fundus imaging; standard full

panretinal photocoagulation. Representative CLARUS 500 (Zeiss GmbH)

pseudocolor UWF montage (200˚ field) depicting standard full

panretinal photocoagulation. A high density of moderately intense

(grade 3-4) laser burns covers the peripheral and mid-peripheral

retina, extending close to the vascular arcades. The posterior

pole, including the macula (asterisk) and immediate peripapillary

region (bracket) are characteristically spared. The optic disc is

indicated. UWF, ultra-widefield; PRP, panretinal

photocoagulation.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

YG and RY contributed to various aspects of the

research, from conceptualization to visualization and taking the

lead in writing. YG and HCL contributed to methodology and

supervision of the project. YG, RY, YL and CJG contributed to data

collection and analysis and contributed to editing and

visualization. YG and HCL confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data. All authors read and approved the final version of the

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Xi'an Bright

Eye Hospital Ethics Committee (Xi'an, China; approval no.

XPR-2018-0018). All patients underwent optometry, intraocular

pressure and visual acuity examinations and all patients

voluntarily participated in the present study and signed informed

consent forms.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Cheung N, Mitchell P and Wong TY: Diabetic

retinopathy. Lancet. 376:124–136. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Kollias AN and Ulbig MW: Diabetic

retinopathy: Early diagnosis and effective treatment. Dtsch Arztebl

Int. 107:75–84. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Congdon NG, Friedman DS and Lietman T:

Important causes of visual impairment in the world today. JAMA.

290:2057–2060. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Lin KY, Hsih WH, Lin YB, Wen CY and Chang

TJ: Update in the epidemiology, risk factors, screening, and

treatment of diabetic retinopathy. J Diabetes Investig.

12:1322–1325. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Song P, Yu J, Chan KY, Theodoratou E and

Rudan I: Prevalence, risk factors and burden of diabetic

retinopathy in China: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Glob

Health. 8(010803)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Kang Q and Yang C: Oxidative stress and

diabetic retinopathy: Molecular mechanisms, pathogenetic role and

therapeutic implications. Redox Biol. 37(101799)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Tan TE and Wong TY: Diabetic retinopathy:

Looking forward to 2030. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne).

13(1077669)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Tan GS, Cheung N, Simó R, Cheung GC and

Wong TY: Diabetic macular oedema. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol.

5:143–155. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Liu E, Craig JE and Burdon K: Diabetic

macular oedema: Clinical risk factors and emerging genetic

influences. Clin Exp Optom. 100:569–576. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Amoaku WM, Ghanchi F, Bailey C, Banerjee

S, Banerjee S, Downey L, Gale R, Hamilton R, Khunti K, Posner E, et

al: Diabetic retinopathy and diabetic macular oedema pathways and

management: UK consensus working group. Eye (Lond). 34 (Suppl

1):S1–S51. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Simunovic MP, Hunyor AP and Ho IV:

Vitrectomy for diabetic macular edema: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. Can J Ophthalmol. 49:188–195. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Yang Z, Tan TE, Shao Y, Wong TY and Li X:

Classification of diabetic retinopathy: Past, present and future.

Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 13(1079217)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Aiello LP and Wong JS: Role of vascular

endothelial growth factor in diabetic vascular complications.

Kidney Int Suppl. 77:S113–S119. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Antonetti DA, Klein R and Gardner TW:

Diabetic retinopathy. N Engl J Med. 366:1227–1239. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Wang W and Lo ACY: Diabetic retinopathy:

Pathophysiology and treatments. Int J Mol Sci.

19(1816)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Wong TY, Cheung CMG, Larsen M, Sharma S

and Simó R: Diabetic retinopathy. Nat Rev Dis Primers.

2(16012)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Lois N, Campbell C, Waugh N, Azuara-Blanco

A, Maredza M, Mistry H, McAuley D, Acharya N, Aslam TM, Bailey C,

et al: Diabetic macular edema and diode subthreshold micropulse

laser: A randomized double-masked noninferiority clinical trial.

Ophthalmology. 130:14–27. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Everett LA and Paulus YM: Laser therapy in

the treatment of diabetic retinopathy and diabetic macular edema.

Curr Diab Rep. 21(35)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Baker CW, Glassman AR, Beaulieu WT,

Antoszyk AN, Browning DJ, Chalam KV, Grover S, Jampol LM, Jhaveri

CD, Melia M, et al: Effect of initial management with aflibercept

vs laser photocoagulation vs observation on vision loss among

patients with diabetic macular edema involving the center of the

macula and good visual acuity: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA.

321:1880–1894. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Arrigo A, Aragona E and Bandello F:

VEGF-targeting drugs for the treatment of retinal

neovascularization in diabetic retinopathy. Ann Med. 54:1089–1111.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Stitt AW, Curtis TM, Chen M, Medina RJ,

McKay GJ, Jenkins A, Gardiner TA, Lyons TJ, Hammes HP, Simó R and

Lois N: The progress in understanding and treatment of diabetic

retinopathy. Prog Retin Eye Res. 51:156–186. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Gedar Totuk OM, Kanra AY, Bromand MN,

Kilic Tezanlayan G, Ari Yaylalı S, Turkmen I and Ardagil Akcakaya

A: Effectiveness of intravitreal ranibizumab in nonvitrectomized

and vitrectomized eyes with diabetic macular edema: A two-year

retrospective analysis. J Ophthalmol. 2020(2561251)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Jampol LM, Glassman AR and Sun J:

Evaluation and care of patients with diabetic retinopathy. N Engl J

Med. 382:1629–1637. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Yau JWY, Rogers SL, Kawasaki R, Lamoureux

EL, Kowalski JW, Bek T, Chen SJ, Dekker JM, Fletcher A, Grauslund

J, et al: Global prevalence and major risk factors of diabetic

retinopathy. Diabetes Care. 35:556–564. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Fu P, Huang Y, Wan X, Zuo H, Yang Y, Shi R

and Huang M: Efficacy and safety of pan retinal photocoagulation

combined with intravitreal anti-VEGF agents for high-risk

proliferative diabetic retinopathy: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 102(e34856)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Figueira J, Fletcher E, Massin P, Silva R,

Bandello F, Midena E, Varano M, Sivaprasad S, Eleftheriadis H,

Menon G, et al: Ranibizumab Plus panretinal photocoagulation versus

panretinal photocoagulation alone for high-risk proliferative

diabetic retinopathy (PROTEUS study). Ophthalmology. 125:691–700.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Figueira J, Silva R, Henriques J, Caldeira

Rosa P, Laíns I, Melo P, Gonçalves Nunes S and Cunha-Vaz J:

Ranibizumab for high-risk proliferative diabetic retinopathy: An

exploratory randomized controlled trial. Ophthalmologica.

235:34–41. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Rebecca , Shaikh FF and Jatoi SM:

Comparison of efficacy of combination therapy of an intravitreal

injection of bevacizumab and photocoagulation versus pan retinal

photocoagulation alone in high risk proliferative diabetic

retinopathy. Pak J Med Sci. 37:157–161. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Tao Y, Jiang P, Zhao Y, Song L, Ma Y, Li Y

and Wang H: Retrospective study of aflibercept in combination

therapy for high-risk proliferative diabetic retinopathy and

diabetic maculopathy. Int Ophthalmol. 41:2157–2165. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Vujosevic S, Aldington SJ, Silva P,

Hernández C, Scanlon P, Peto T and Simó R: Screening for diabetic

retinopathy: New perspectives and challenges. Lancet Diabetes

Endocrinol. 8:337–347. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Berrocal MH and Acaba-Berrocal L: Early

pars plana vitrectomy for proliferative diabetic retinopathy:

Update and review of current literature. Curr Opin Ophthalmol.

32:203–208. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|