Introduction

Myopia is a refractive error frequently attributed

to elongation of the ocular axis (1). Severe myopia can lead to various

complications, including myopic macular degeneration and amblyopia,

resulting in vision impairment and marked health consequences,

including retinal detachment and early-onset cataracts (2,3). In

addition, myopia has been classified among the five serious ocular

conditions that may lead to blindness (4). In recent years, the prevalence of

myopia has increased rapidly, and the age of onset has gradually

decreased to 15.6±4.2 years, making it a global health concern

(5), with the global prevalence of

myopia projected to reach 50% of the population by 2050(4). The choroid plays a crucial role in

the development of myopia (6).

Myopic visual signals can lead to decreased choroidal blood flow,

leading to a reduced supply of oxygen and nutrients to the sclera.

These conditions result in reduced scleral strength and thickness,

axial elongation and the focus of light rays in front of the

retina, thereby causing myopia (7-9).

Following the application of orthokeratology lenses

to treat myopia, the centre of the cornea flattens, the peripheral

retinal refractive state shifts from relative hyperopic defocus to

myopic defocus (10-12),

the axial length (AL) of the eye shows decelerated growth and

choroidal thickness (CT) markedly increases (13-15).

Small incision lenticule extraction (SMILE) and femtosecond

laser-assisted in situ keratomileusis (FS-LASIK) are

currently the predominant corneal refractive surgical procedures.

SMILE and FS-LASIK correct myopia by ablating the central stroma of

the cornea, thereby reducing corneal curvature and enabling light

to focus on the retina. Both these procedures yield comparable

outcomes in terms of safety, efficacy, predictability and stability

for correcting myopia and myopic astigmatism (16,17).

Similarly, SMILE and FS-LASIK also reduces the central curvature of

the cornea and alters the defocus state of the retina (18-20).

Thus, whether the choroid undergoes the same changes after SMILE

and FS-LASIK as observed after orthokeratology lens use remains

unclear. To the best of our knowledge, studies on the choroid after

corneal refractive surgery are relatively limited. Optical

coherence tomography (OCT) represents a breakthrough in ophthalmic

imaging, allowing for the scanning of multiple intraocular tissue

structures and the evaluation of choroidal vasculature (21). The present study aimed to apply OCT

to measure central and peripheral CT and blood flow density in

patients with myopia before and after SMILE and FS-LASIK surgeries,

to observe the choroidal changes induced by these two

procedures.

Materials and methods

Patients

The present study enrolled patients who underwent

SMILE or FS-LASIK surgery for myopia correction at Jinan Mingshui

Eye Hospital (Jinan, China) between November 2020 and October 2022.

All patients provided written informed consent for refractive

surgery and the use of their data in research. The inclusion

criteria were as follows: i) Age 18-30 years; ii) maximum annual

increase in myopic spherical equivalent (SE) of -0.5 diopters (D)

within 2 years; iii) SE ranging from -3.00 to -10.00 D; and iv)

normal fundus oculi. Exclusion criteria included: i) Keratoconus or

corneal ectasia; ii) corneal dystrophy; iii) scar constitution; iv)

conjunctivitis; v) keratitis; vi) compromised immune function; and

vii) mental instability. A total of 56 patients were included, with

35 patients in the SMILE group and 21 patients in the FS-LASIK

group. The sex distribution and age range of the patients are

presented in the results section. The study protocol adhered to the

principles of The Declaration of Helsinki and received approval

from the Human Ethics Committee of Jinan Mingshui Eye Hospital

(approval no. 2020-020).

Ophthalmological examination

SE, AL, ablation depth (AD), CT and blood flow

density were measured before surgery and at 1 week, 1 month and 3

months postoperatively. AL was obtained using the IOLMaster 500

(Zeiss AG; Oberkochen; Germany) to measure the distance from the

anterior corneal surface to the retinal pigment epithelium.

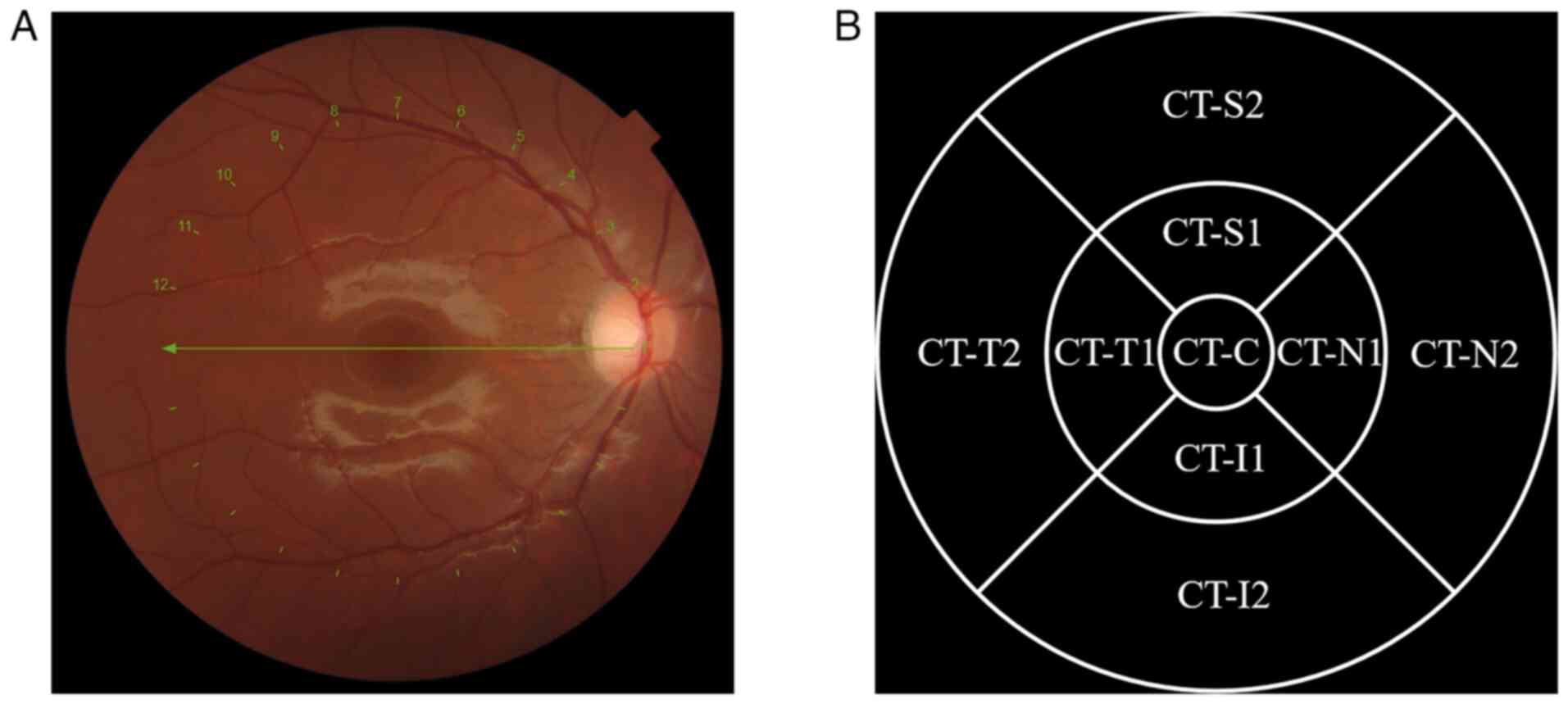

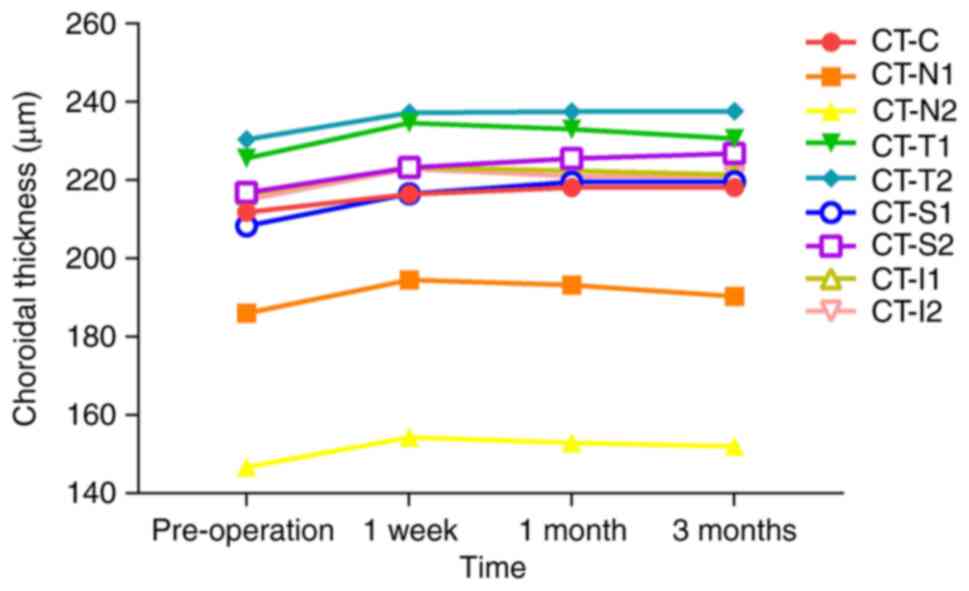

CT was measured using ‘Radial Dia 6.0 mm overlap

radial scanning mode’ of OCT for the macula (DRI-OCT Triton; Topcon

Corporation). A circular area with a 6-mm diameter centred on the

macular fovea was scanned. CT was defined as the vertical distance

from Bruch's membrane to the choroid-sclera junction and was

measured in micrometres. The scanning area was divided into the

following regions for CT measurements: The centre of the macula

(CT-C), 0.5 mm nasal (CT-N1), 1.5 mm nasal (CT-N2), 0.5 mm temporal

(CT-T1), 1.5 mm temporal (CT-T2), 0.5 mm superior (CT-S1), 1.5 mm

superior (CT-S2), 0.5 mm inferior (CT-I1) and 1.5 mm inferior

(CT-I2) to the centre, as shown in Fig. 1.

| Figure 1Measurement of CT. (A) Imaging of CT

during optical coherence tomography scanning. (B) The scanned area

was divided into different regions in the form of quadrants,

including the following regions: CT-C, CT-N1, CT-N2, CT-T1, CT-T2,

CT-S1, CT-S2, CT-I1 and CT-I2. Numbers 1 to 12 indicate the

positions of the captured images. CT, choroidal thickness; CT-C, CT

at the centre of the macula; CT-N1, CT at 0.5 mm nasal; CT-N2, CT

at 1.5 mm nasal; CT-T1, CT at 0.5 mm temporal; CT-T2, CT at 1.5 mm

temporal; CT-S1, CT at 0.5 mm superior; CT-S2, CT at 1.5 mm

superior; CT-I1, CT at 0.5 mm inferior; CT-I2, CT at 1.5 mm

inferior. |

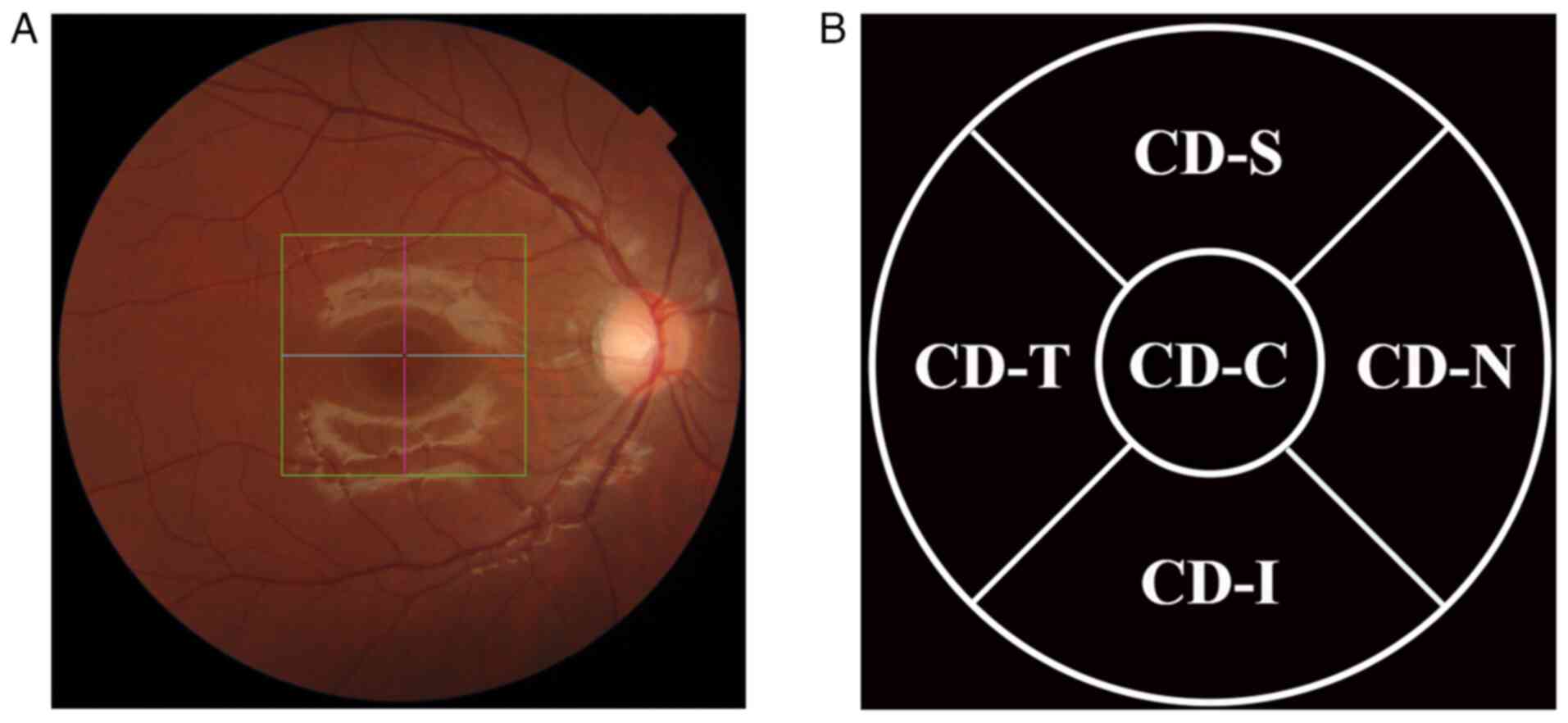

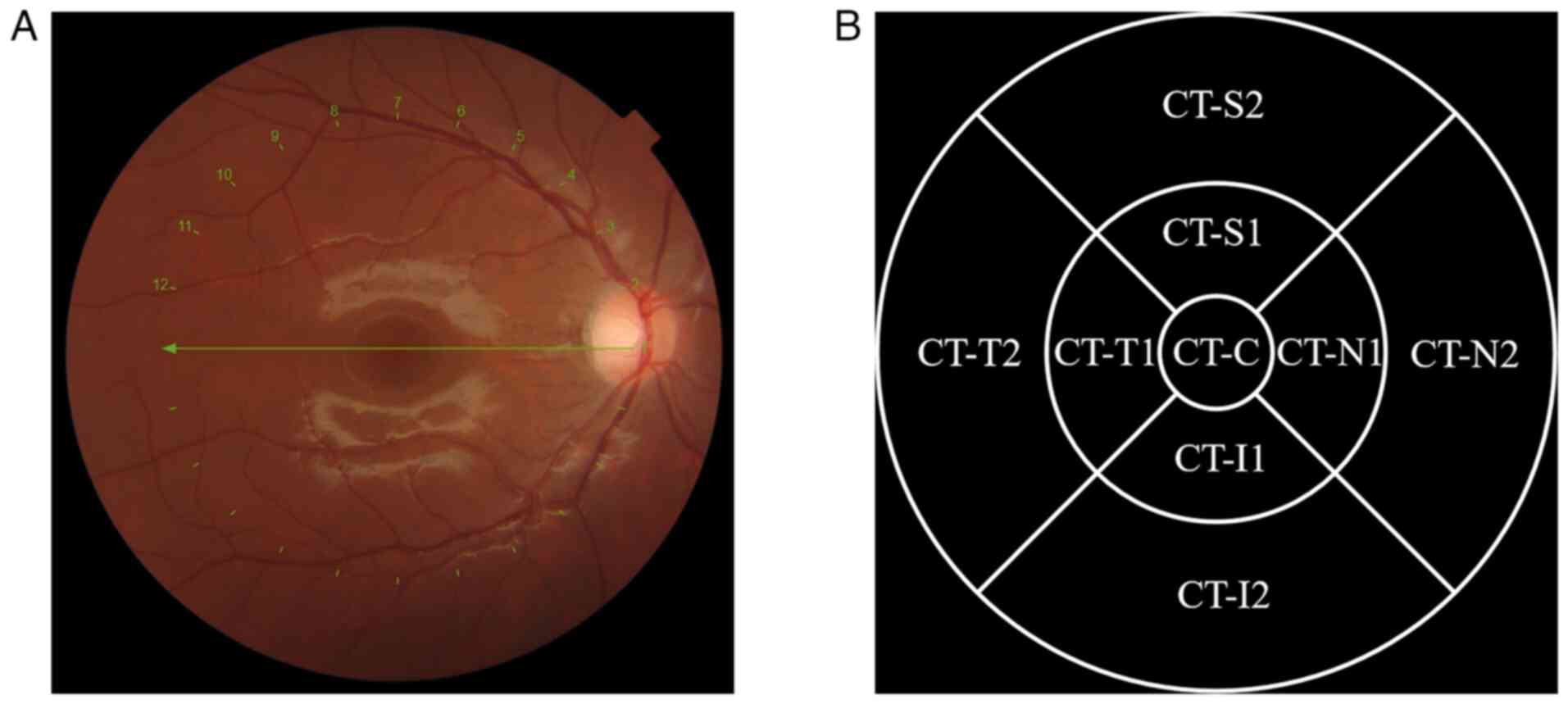

To measure blood flow density, the ‘OCT Angiography

(OCTA) 4.5x4.5’ scanning mode was selected (DRI-OCT Triton; Topcon

Corporation). The macular centre was examined in a 4.5x4.5 mm area.

Scattering of the retina generates artifacts anterior to the

choroid, and the sensitivity of OCTA decreases sharply with

increasing scanning depth, both of which affect the imaging quality

of the blood flow (22,23). Therefore, to minimize measurement

errors, the depth range of 10.4-31.2 µm below Bruch's membrane was

selected to obtain the choriocapillaris blood flow density (CD)

(22,24). The scanning area was divided into

the following regions for CD measurements: Centre of the macula,

0.5 mm nasal, 0.5 mm temporal (CD-T), 0.5 mm superior and 0.5 mm

inferior to the centre, as shown in Fig. 2.

| Figure 2Measurement of CD. (A) Imaging of the

choriocapillaris vessels during optical coherence tomography

scanning. The square in the picture represents the scanning area

used by the instrument to measure blood flow density, and the cross

is the center of the scan. (B) The scanned area was divided into

different regions in the form of quadrants, including the following

regions: CD-C, CD-N, CD-T, CD-S and CD-I. CD, choriocapillaris

blood flow density; CD-C, CD at the centre of the macula; CD-N, CD

at 0.5 mm nasal; CD-T, CD at 0.5 mm temporal; CD-S, CD at 0.5 mm

superior; CD-I, CD at 0.5 mm inferior. |

All examinations were conducted between 8:00 and

11:00 a.m. to account for the circadian rhythm of the choroid

(25). In addition, all procedures

were performed by the same experienced optometrist to avoid

systematic errors.

Surgical procedure

SMILE was performed using the VisuMax femtosecond

laser (VisuMax-500; Zeiss AG) to create corneal lenticules and

caps. The surgical plan was developed based on preoperative

refractive diopter and entered into the device. Laser scanning was

then initiated, followed by lenticule removal using forceps through

the upper aperture.

FS-LASIK was performed as a two-step procedure.

First, a corneal flap was created using the VisuMax femtosecond

laser. Next, the patient was transferred to the excimer laser

system (AMARIS-500E; SCHWIND eye-tech-solution GmbH), where the

corneal flap was opened and the corneal stroma was ablated. Normal

saline was used to irrigate the stromal bed and conjunctival sac,

resulting in a smooth corneal flap. All surgeries were performed by

the same qualified and experienced ophthalmologist.

Statistical analysis

SPSS 25.0 statistical software (IBM Corp.) was used

for data analysis. Normally distributed data are presented as the

mean ± standard deviation, while non-normally distributed data are

presented as the median (25th percentile, 75th percentile). When

comparing the baseline characteristics between the SMILE and

FS-LASIK groups, independent sample Student's t-test was used for

the analysis of normally distributed data, while the non-parametric

Mann-Whitney U test was used for data not conforming to a normal

distribution. When conducting overall intergroup and intragroup

analyses of various parameters, a two-way mixed ANOVA was used for

normally distributed data, while non-normally distributed data were

analysed using the non-parametric K-related sample Friedman test

for within-group comparisons and the Mann-Whitney U test for

between-group comparisons, all followed by a Bonferroni post hoc

test or correction as necessary. Correlations between datasets were

performed using Spearman correlation analysis. P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Baseline characteristics

The present study included 56 patients (112 eyes;

all surgeries were performed on both eyes). The patients had a mean

age of 23.07±3.61 years and a mean SE of -5.75±1.77 D. The SMILE

group had a mean age of 22.89±3.01 years and a mean SE of

-5.76±1.67 D; this group included 35 patients (15 male patients and

20 female patients). The FS-LASIK group had a mean age of

23.38±4.51 years and a mean SE of -5.74±1.79 D; this group included

21 patients (7 male patients and 14 female patients). No

significant differences were found between the groups in age,

preoperative SE, AL, AD of the corneal stroma, CT or CD

(P>0.05). Table I presents the

baseline characteristic comparisons between the two groups.

| Table IComparison of baseline

characteristics between the SMILE and FS-LASIK groups. |

Table I

Comparison of baseline

characteristics between the SMILE and FS-LASIK groups.

| Variable | SMILE | FS-LASIK | t/Z-value | P-value |

|---|

| Age, years | 22.89±3.01 | 23.38±4.51 | -0.447 | 0.658 |

| SE, D | -5.76±1.67 | -5.74±1.79 | 1.580 | 0.343 |

| AL, mm | 25.45 (24.70,

26.08) | 25.62 (24.99,

26.34) | -0.884 | 0.377 |

| AD, µm | 98.37±25.27 | 92.74±22.35 | 1.192 | 0.236 |

| CT-C, µm | 227.69±82.07 | 211.83±63.11 | 1.323 | 0.189 |

| CT-N1, µm | 200.00 (151.25,

248.00) | 177.00 (144.00,

226.75) | -1.328 | 0.184 |

| CT-N2, µm | 159.00 (123.00,

216.75) | 141.50 (112.75,

202.00) | -1.614 | 0.107 |

| CT-T1, µm | 241.24±80.51 | 225.65±65.97 | 1.205 | 0.231 |

| CT-T2, µm | 252.27±76.23 | 230.42±63.50 | 1.678 | 0.096 |

| CT-S1, µm | 235.87±76.60 | 208.32±64.40 | 2.030 | 0.055 |

| CT-S2, µm | 245.74±71.49 | 216.88±58.12 | 2.202 | 0.060 |

| CT-I1, µm | 236.70±83.19 | 216.43±62.74 | 1.693 | 0.094 |

| CT-I2, µm | 234.50 (178.75,

297.75) | 217.50 (170.50,

245.50) | -1.668 | 0.095 |

| CD-C, % | 55.52±4.91 | 55.23±4.66 | 0.534 | 0.595 |

| CD-N, % | 55.94±3.83 | 55.48±2.44 | 1.015 | 0.312 |

| CD-T, % | 57.22 (55.10,

58.90) | 55.89 (53.72,

56.88) | -2.515 | 0.067 |

| CD-S, % | 51.01±3.91 | 50.90±3.35 | 0.398 | 0.691 |

| CD-I, % | 53.19 (51.06,

56.15) | 53.74 (51.09,

55.60) | -0.237 | 0.621 |

Changes in SE and AL. Changes in

SE

The SE at all postoperative time points was

significantly increased compared with that before the surgery in

each group (P<0.001). Statistically significant differences

between the two groups were observed at 1 week and 1 month

postoperatively (P<0.05) but not at the remaining time points

(P>0.05) (Table II).

| Table IIChanges in SE and AL before and after

the operation in the SMILE and FS-LASIK groups. |

Table II

Changes in SE and AL before and after

the operation in the SMILE and FS-LASIK groups.

| A, SE, D |

|---|

| Variable | Pre-operation | 1 week | 1 month | 3 months |

F/χ2-value | P-value |

|---|

| SMILE | -5.74±1.79 | 0.00±0.30 | -0.03±0.27 | 0.01±0.31 | 612.340 | <0.001 |

| FS-LASIK | -5.76±1.67 | 0.33±0.28 | 0.29±0.28 | -0.06±0.05 | 598.430 | <0.001 |

| P-value | 0.343 | <0.001 | 0.010 | 0.610 | | |

| B, AL, mm |

| Variable | Pre-operation | 1 week | 1 month | 3 months |

F/χ2-value | P-value |

| SMILE | 25.45 (24.70,

26.08) | 25.29 (24.61,

25.94) | 25.32 (24.59,

25.93) | 25.29 (24.59,

25.93) | 137.586 | <0.001 |

| FS-LASIK | 25.62 (24.99,

26.34) | 25.48 (24.88,

26.14) | 25.48 (24.85,

26.14) | 25.50 (24.85,

26.16) | 84.274 | <0.001 |

| P-value | 0.377 | 0.465 | 0.447 | 0.220 | | |

Changes in AL. The AL at each time point

postoperatively was significantly shorter than preoperative AL in

both groups (P<0.001). No significant differences were found

between the two groups at each time point before and after surgery

(P>0.05) (Table II).

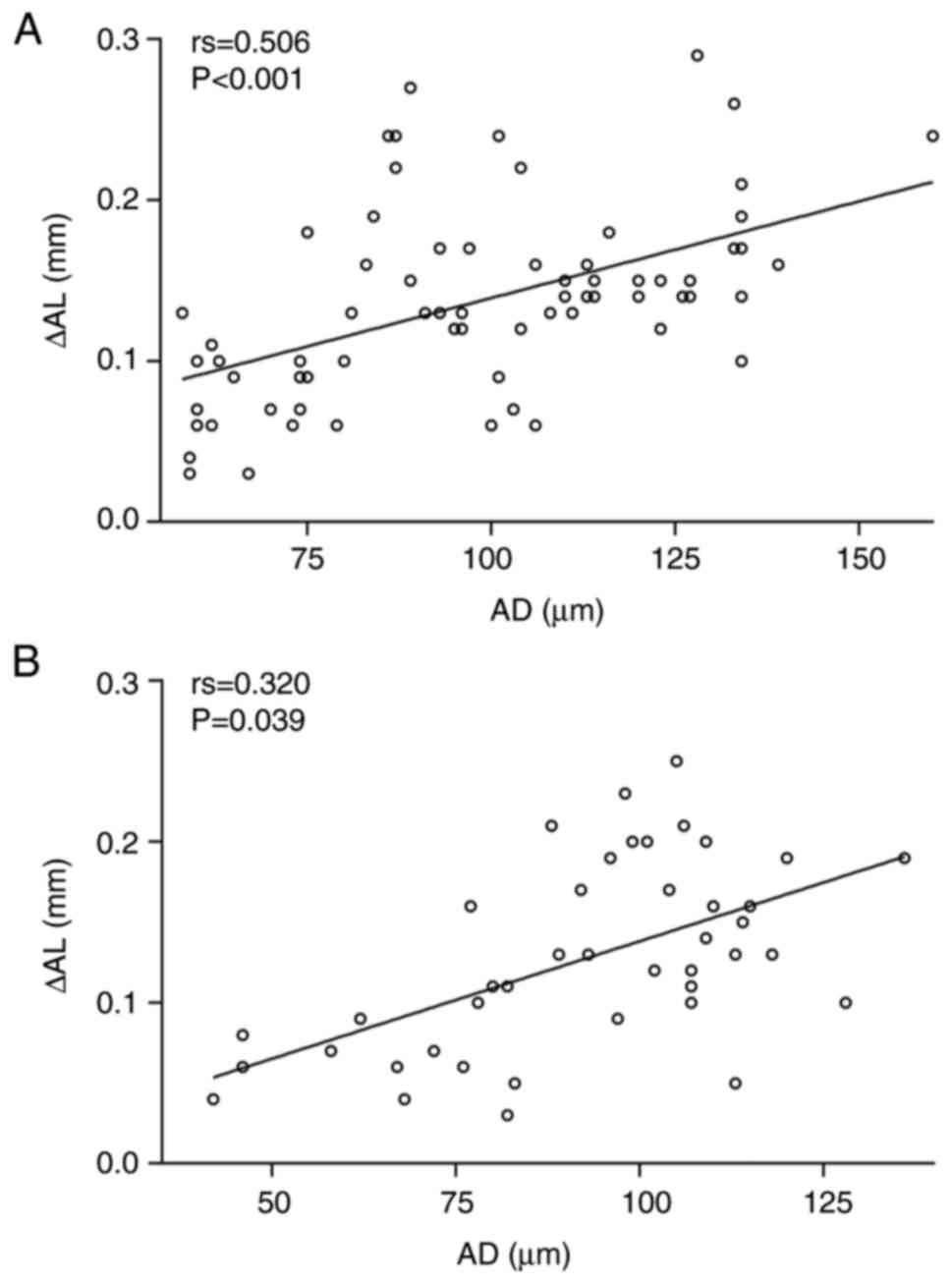

Correlation between the shortening of AL and

AD. A significant correlation was found between the shortening

of AL and AD at 3 months postoperatively in the SMILE group

compared with the preoperative values (P<0.001; Fig. 3A). In addition, a significant

correlation was also found between the shortening of AL and AD at 3

months postoperatively in the FS-LASIK group (P=0.039; Fig. 3B).

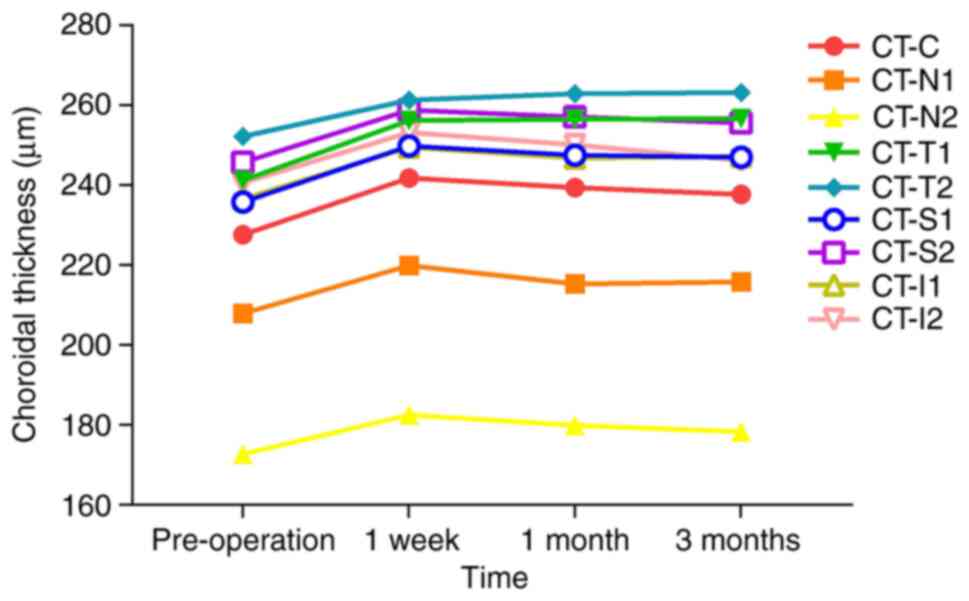

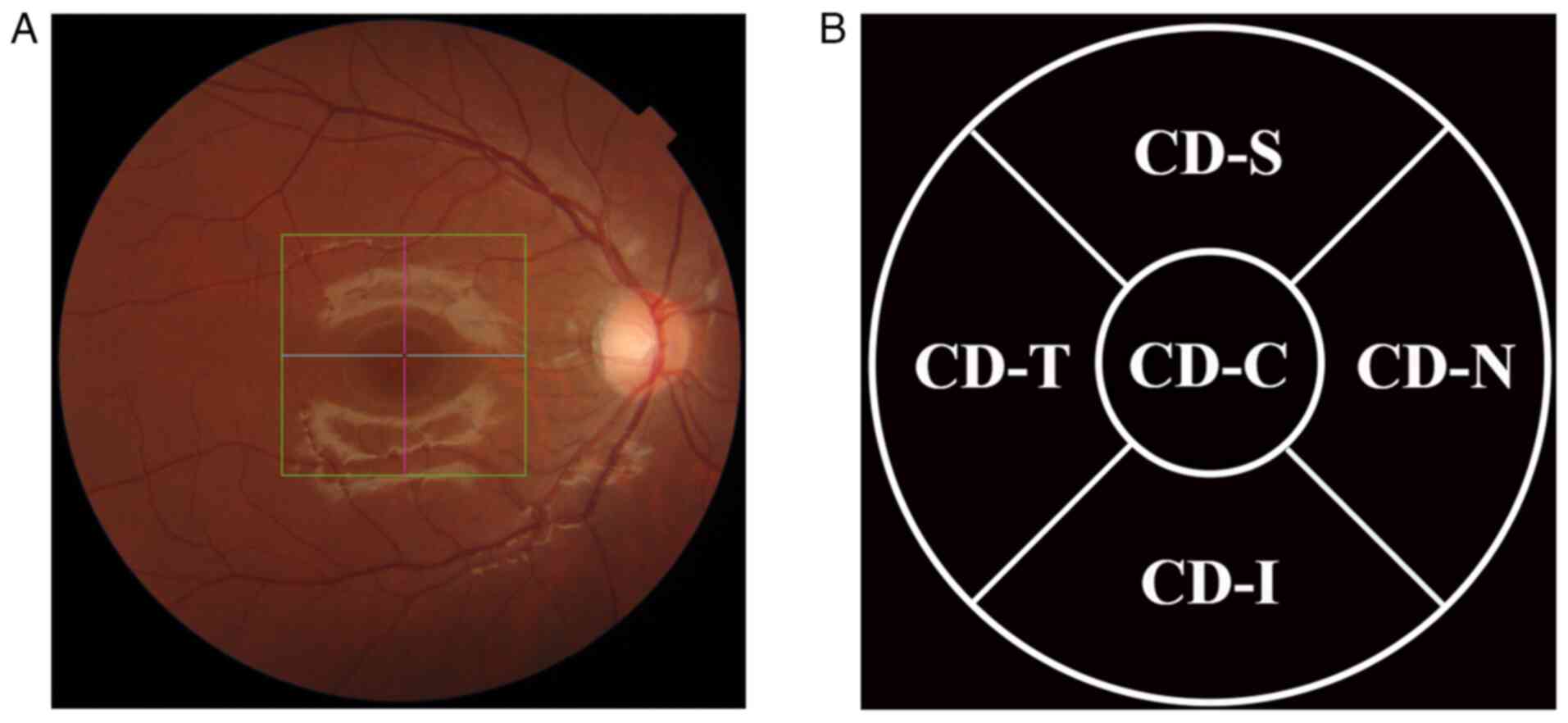

Changes in CT. Changes in CT in the

SMILE group

CT-C, CT-N1, CT-N2, CT-S1, CT-S2, CT-I1 and CT-I2

were significantly increased at 1 week postoperatively compared

with their preoperative levels (P<0.001), followed by a

decreasing trend and the return to preoperative thickness by 3

months after surgery (P>0.05). CT-T1 and CT-T2 remained

significantly increased compared with preoperative values at all

postoperative time points (P<0.001); however, these two

measurement indicators showed a slow growth trend at 1 month and 3

months postoperatively. Details on the levels of the CT parameters

are presented in Table III and

Fig. 4.

| Figure 4Change in the trend of CT before and

after the operation in the small incision lenticule extraction

group measured across different regions. Pre, pre-operation; CT,

choroidal thickness; CT-C, CT at the centre of the macula; CT-N1,

CT at 0.5 mm nasal; CT-N2, CT at 1.5 mm nasal; CT-T1, CT at 0.5 mm

temporal; CT-T2, CT at 1.5 mm temporal; CT-S1, CT at 0.5 mm

superior; CT-S2, CT at 1.5 mm superior; CT-I1, CT at 0.5 mm

inferior; CT-I2, CT at 1.5 mm inferior. |

| Table IIIChanges in CT before and after the

operation in the SMILE and FS-LASIK groups. |

Table III

Changes in CT before and after the

operation in the SMILE and FS-LASIK groups.

| A, CT-C, µm |

|---|

| Variable | Pre-operation | 1 week | 1 month | 3 months |

F/χ2-value | P-value |

|---|

| SMILE | 227.69±82.07 | 241.83±84.35 | 239.46±83.41 | 237.77±81.29 | 14.024 | <0.001 |

| FS-LASIK | 211.83±63.11 | 216.48±64.39 | 218.20±64.83 | 218.15±65.76 | 1.889 | 0.035 |

| P-value | 0.189 | 0.050 | 0.108 | 0.128 | | |

| B, CT-N1, µm |

| Variable | Pre-operation | 1 week | 1 month | 3 months |

F/χ2-value | P-value |

| SMILE | 200.00 (151.25,

248.00) | 207.50 (155.00,

279.25) | 205.00 (153.50,

265.00) | 206.00 (152.50,

271.00) | 31.108 | <0.001 |

| FS-LASIK | 177.00 (144.00,

226.75) | 187.50 (151.25,

228.75) | 191.50 (144.25,

248.50) | 192.00 (134.50,

239.75) | 8.632 | 0.031 |

| P-value | 0.184 | 0.168 | 0.234 | 0.129 | | |

| C, CT-N2, µm |

| Variable | Pre-operation | 1 week | 1 month | 3 months |

F/χ2-value | P-value |

| SMILE | 159.00 (123.00,

216.75) | 163.00 (12825,

230.25) | 155.00 (122.00,

217.00) | 154.00 (12.002,

220.25) | 25.536 | <0.001 |

| FS-LASIK | 141.50 (112.75,

202.00) | 150.50 (115.75,

202.25) | 145.00 (113.50,

193.00) | 149.50 (105.00,

189.75) | 10.832 | 0.013 |

| P-value | 0.107 | 0.188 | 0.220 | 0.222 | | |

| D, CT-T1, µm |

| Variable | Pre-operation | 1 week | 1 month | 3 months |

F/χ2-value | P-value |

| SMILE | 241.24±80.51 | 256.24±80.22 | 256.57±82.46 | 256.76±81.77 | 17.534 | <0.001 |

| FS-LASIK | 225.65±65.97 | 234.62±70.26 | 233.00±69.26 | 230.70±70.09 | 2.581 | 0.057 |

| P-value | 0.231 | 0.103 | 0.085 | 0.060 | | |

| E, CT-T2, µm |

| Variable | Pre-operation | 1 week | 1 month | 3 months |

F/χ2-value | P-value |

| SMILE | 252.27±76.23 | 261.31±73.37 | 262.96±75.08 | 263.26±75.09 | 6.238 | <0.001 |

| FS-LASIK | 230.42±63.50 | 237.25±66.84 | 237.50±67.50 | 237.68±65.17 | 3.113 | 0.039 |

| P-value | 0.096 | 0.063 | 0.045 | 0.058 | | |

| F, CT-S1, µm |

| Variable | Pre-operation | 1 week | 1 month | 3 months |

F/χ2-value | P-value |

| SMILE | 235.87±76.60 | 249.80±79.13 | 247.50±79.54 | 247.00±79.30 | 18.432 | <0.001 |

| FS-LASIK | 208.32±64.40 | 216.58±62.16 | 219.52±61.59 | 219.68±61.93 | 3.097 | 0.030 |

| P-value | 0.055 | 0.016 | 0.061 | 0.056 | | |

| G, CT-S2, µm |

| Variable | Pre-operation | 1 week | 1 month | 3 months |

F/χ2-value | P-value |

| SMILE | 245.74±71.49 | 258.83±75.15 | 257.16±76.20 | 255.63±73.09 | 12.220 | <0.001 |

| FS-LASIK | 216.88±58.12 | 223.22±62.13 | 225.58±64.18 | 226.83±61.10 | 3.683 | 0.030 |

| P-value | 0.060 | 0.010 | 0.022 | 0.064 | | |

| H, CT-I1, µm |

| Variable | Pre-operation | 1 week | 1 month | 3 months |

F/χ2-value | P-value |

| SMILE | 236.70±83.19 | 249.56±86.29 | 246.83±87.99 | 247.23±84.41 | 13.852 | <0.001 |

| FS-LASIK | 216.43±62.74 | 223.30±65.26 | 222.45±64.91 | 221.47±68.42 | 1.966 | 0.140 |

| P-value | 0.094 | 0.058 | 0.077 | 0.060 | | |

| I, CT-I2, µm |

| Variable | Pre-operation | 1 week | 1 month | 3 months |

F/χ2-value | P-value |

| SMILE | 234.50 (178.75,

297.75) | 237.00 (201.25,

327.00) | 229.50 (199.00,

304.25) | 230.00 (193.25,

284.00) | 27.965 | <0.001 |

| FS-LASIK | 217.50 (170.50,

245.50) | 225.00 (171.75,

257.00) | 218.50 (170.50,

261.00) | 222.00 (161.75,

271.50) | 11.310 | 0.010 |

| P-value | 0.095 | 0.072 | 0.100 | 0.092 | | |

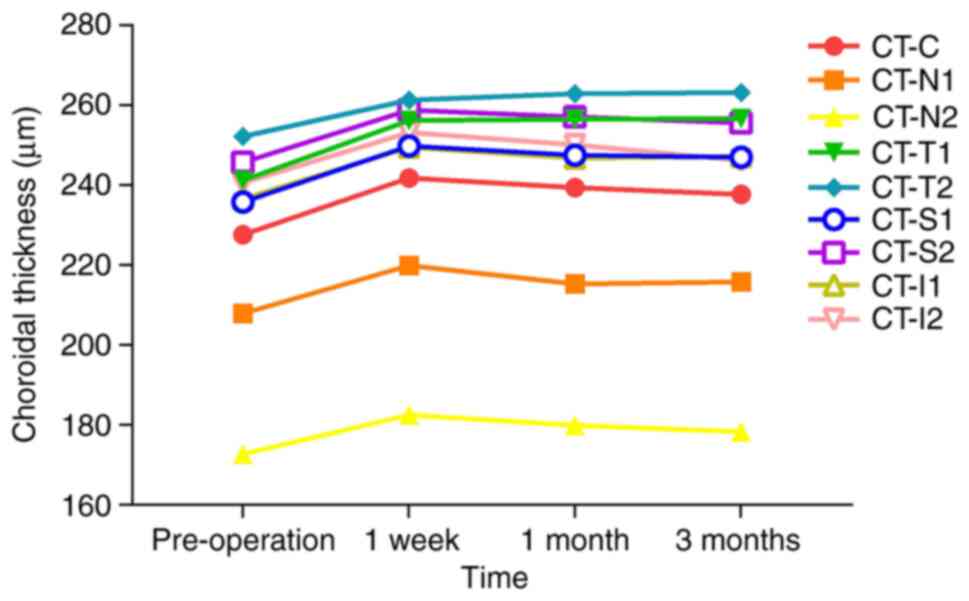

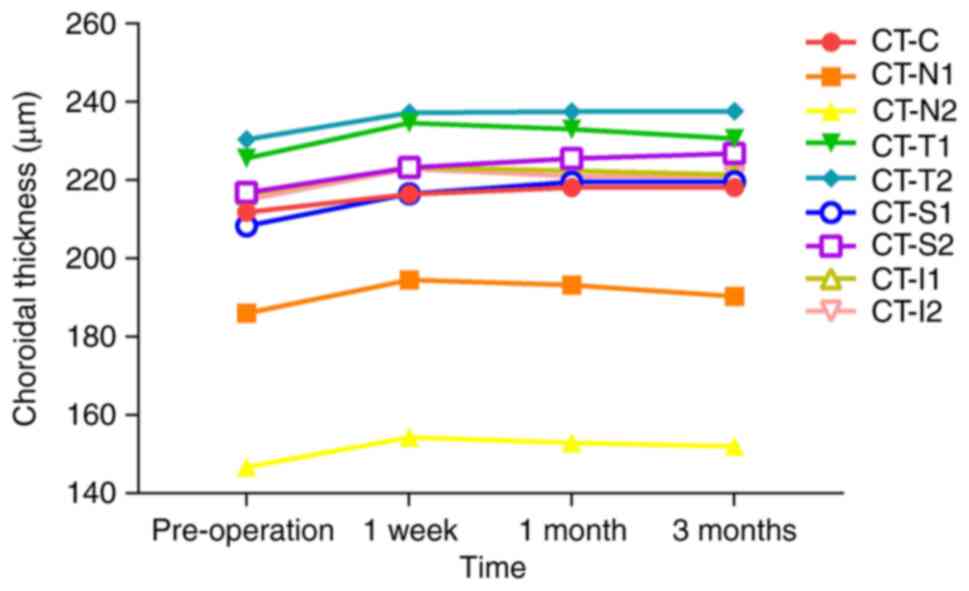

Changes in CT in the FS-LASIK group. CT-N1,

CT-N2 and CT-I2 significantly increased at 1 week postoperatively

compared with their preoperative levels (all P<0.05),

followed by gradual decrease by 1 month. No significant difference

was found at 3 months postoperatively compared with the baseline

(P>0.05). CT-T1 and CT-I1 showed no significant changes but

followed a pattern of initial increase followed by reduction at 1

month postoperatively. All other measurement sites showed

significantly greater thickness than their preoperative levels at

all postoperative time points (P<0.05) but T2, S1 and S2

exhibited a slow increase, and CT-C exhibited a decrease at 3

months postoperatively. Details on the levels of the CT parameters

are presented in Table III and

Fig. 5.

| Figure 5Change in the trend of CT before and

after the operation in the femtosecond laser-assisted in

situ keratomileusis group measured across different regions.

Pre, pre-operation; CT, choroidal thickness; CT-C, CT at the centre

of the macula; CT-N1, CT at 0.5 mm nasal; CT-N2, CT at 1.5 mm

nasal; CT-T1, CT at 0.5 mm temporal; CT-T2, CT at 1.5 mm temporal;

CT-S1, CT at 0.5 mm superior; CT-S2, CT at 1.5 mm superior; CT-I1,

CT at 0.5 mm inferior; CT-I2, CT at 1.5 mm inferior. |

Comparison of CT between the two groups. The

CT-T2 in the SMILE group was significantly thicker than that in the

FS-LASIK group at 1 month postoperatively (P=0.045). CT-S1 in the

SMILE group was significantly thicker than that in the FS-LASIK

group at 1 week (P=0.016), as was CT-S2 at both 1 week and 1 month

postoperatively (P<0.05). No significant differences were

observed between groups at other measurement sites across the

postoperative timepoints (P>0.05) (Table III).

Changes in CD. Changes in CD in the

SMILE group

A significant decrease in CD-T was observed at 1

week postoperatively (P=0.010), but the values returned to

preoperative levels by 1 month. No significant changes were found

at other observation sites (Table

IV).

| Table IVChanges in CD before and after the

operation in the SMILE and FS-LASIK groups. |

Table IV

Changes in CD before and after the

operation in the SMILE and FS-LASIK groups.

| A, CD-C, % |

|---|

| Variable | Pre-operation | 1 week | 1 month | 3 months |

F/χ2-value | P-value |

|---|

| SMILE | 55.52±4.91 | 55.19±6.02 | 55.54±5.48 | 55.18±5.87 | 0.249 | 0.843 |

| FS-LASIK | 55.23±4.66 | 57.15±5.14 | 55.10±4.84 | 55.40±5.42 | 2.694 | 0.050 |

| P-value | 0.595 | 0.052 | 0.634 | 0.893 | | |

| B, CD-N, % |

| Variable | Pre-operation | 1 week | 1 month | 3 months |

F/χ2-value | P-value |

| SMILE | 55.94±3.83 | 55.35±3.58 | 55.36±4.01 | 55.69±4.13 | 0.852 | 0.467 |

| FS-LASIK | 55.48±2.44 | 55.31±3.91 | 54.81±3.69 | 56.12±4.32 | 1.832 | 0.160 |

| P-value | 0.312 | 0.756 | 0.810 | 0.681 | | |

| C, CD-T, % |

| Variable | Pre-operation | 1 week | 1 month | 3 months |

F/χ2-value | P-value |

| SMILE | 57.22 (55.10,

58.90) | 56.43 (54.28,

57.86) | 56.30 (54.36,

58.45) | 56.97 (54.52,

59.06) | 10.898 | 0.012 |

| FS-LASIK | 55.89 (53.72,

56.88) | 55.25(53.73,

57.49) | 56.10 (53.15,

57.80) | 56.58 (53.69,

58.33) | 0.756 | 0.521 |

| P-value | 0.067 | 0.261 | 0.140 | 0.489 | | |

| D, CD-S, % |

| Variable | Pre-operation | 1 week | 1 month | 3 months |

F/χ2-value | P-value |

| SMILE | 51.01±3.91 | 51.58±3.86 | 51.94±3.84 | 52.06±4.74 | 2.029 | 0.111 |

| FS-LASIK | 50.90±3.35 | 52.08±3.50 | 51.86±3.53 | 50.89±4.07 | 2.492 | 0.085 |

| P-value | 0.691 | 0.794 | 0.730 | 0.189 | | |

| E, CD-I, % |

| Variable | Pre-operation | 1 week | 1 month | 3 months |

F/χ2-value | P-value |

| SMILE | 53.19 (51.06,

56.15) | 53.83 (50.34,

56.46) | 53.76 (51.66,

57.07) | 54.45 (50.32,

57.56) | 2.584 | 0.460 |

| FS-LASIK | 53.74 (51.09,

55.60) | 54.02 (51.28,

56.01) | 53.62 (50.62,

56.57) | 53.74 (50.10,

58.13) | 0.368 | 0.699 |

| P-value | 0.621 | 0.995 | 0.757 | 0.843 | | |

Changes in CD in the FS-LASIK group. No

significant changes in CD parameters were observed among

preoperative and postoperative groups (Table IV).

Comparison of CD between the two groups. No

statistically significant differences were found between the

surgical groups at any time point before or after surgery (Table IV).

Discussion

The choroid, an essential ocular tissue, responds to

changes in internal visual signal transmission, and visual signals

of peripheral myopic defocus on the retina induce choroidal

thickening (26-28).

Recent studies have shown that after correcting myopia with

orthokeratology lenses, peripheral retinal myopic defocus results

in increased CT (13-15).

Although corneal refractive surgery also alters the retinal defocus

state during myopia correction (19,20),

the present study, in conjunction with existing research (29,30),

revealed that choroidal responses may not entirely mirror those

observed with orthokeratology.

In the present study, after SMILE and FS-LASIK, CT

increased initially and then gradually returned to baseline at the

majority of measurement sites. Among the two groups, only a very

small number of measurement sites showed significant differences in

choroidal thickness at very few time points. These findings are

consistent with those of previous research. Xu et al

(29) reported that CT increased

after FS-LASIK but returned to baseline levels 3 months

postoperatively. Zhang et al (30) observed a temporary increase in CT 2

h after FS-LASIK, which returned to preoperative levels at 1 week;

however, the average thickness at 3 months postoperatively exceeded

that at 2 h after the operation, which differs from the present

study results. The authors attributed the transient increase to

elevated intraocular pressure during surgery, which may stimulate

the choroid, causing thickening. As intraocular pressure

stabilizes, CT initially recovers, followed by an increase possibly

related to myopic defocus of the peripheral retina, similar to

orthokeratology mechanisms (30).

Another study demonstrated that myopic defocus promotes the

recovery of CT and slows axial elongation (31), further supporting the association

between choroidal changes and retinal defocus state. In the present

study, choroidal thickening occurred during the early postoperative

period. In addition to the aforementioned mechanisms, we

hypothesize that changes in signal molecule transmission along the

retina-choroid pathway may contribute to these findings. Previous

studies indicated that alterations in visual signals can regulate

the release of dopamine in the dopamine pathway (32,33);

an increase in dopamine secretion can lead to the thickening of the

choroid and inhibit the progression of myopia, whereas a decrease

in secretion has the opposite effect (7,34).

Corneal refractive surgery reduces central corneal curvature,

shifting the peripheral retina defocus from hyperopic to myopic

(19,20); consequently, this emmetropization

of the visual signal increases the secretion of dopamine from the

retina to the choroid, increasing CT. This hypothesis aligns with

the perspectives shared in the study by Cheng et al

(35), where it was also

considered that the release of dopamine is what caused the change

in the thickness of the choroid. This mechanism may occur during

the early postoperative period, as retinal areas adapt to the

altered visual environment, after which dopamine secretion

decreases (7) and CT gradually

returns to baseline. In the present study, in both the SMILE and

FS-LASIK groups, some measurement points, primarily at the macular

centre (CT-C), temporal side (CT-T) or superior region (CT-S),

remained increased compared with their preoperative levels

throughout the study. These regions are known to have relatively

greater CT (36,37), and thicker choroid exhibits a

delayed response to visual signalling (7). Although CT in these regions stayed

above baseline, these variables demonstrated a slow increase or

decline. However, the clinical relevance of CT changes remains

unclear; the present study only tracked patients until 3 months

post-surgery, and more long-term observations are required to

clarify the outcomes.

Xu et al (29) reported a notable decrease in

choroidal blood flow density 1 day after surgery, which returned to

baseline near the macular centre by 1 month. Similarly, Chen et

al (38) observed reduced

vascular density in and around the optic disc 1 day after SMILE,

with recovery by 1 week postoperatively. Another study revealed an

initial decline in vascular density after FS-LASIK, followed by a

gradual increase and return to preoperative levels within 1 month

(39). In the present study, CD

decreased at a single site in the SMILE group but returned to

baseline. No significant changes were observed in other areas.

These findings are consistent with those of Chen et al

(40), who reported no significant

changes in superficial or deep retinal vascular density

post-surgery. In the present study, CD was specifically measured to

minimize artifacts from the anterior retina and reduce potential

errors from scanning deeper layers of the choroid (22-24).

We hypothesize that postoperative changes in choroidal blood flow

density may not be entirely absent but could occur in the deeper

choroidal vasculature, which remains underexplored. Currently,

although OCTA can be used to image the choriocapillaris blood flow,

this technique has limitations (22,41),

including reduced detection sensitivity in deeper tissues and

artifacts during scanning, which limits the conclusions on the

overall choroidal blood flow in the present study. Based on the

results of the current study, it is proposed that temporary changes

in intraocular pressure do not markedly affect choroidal blood

flow. A previous study supports this view, showing that choroidal

blood flow remains relatively stable during the early stages of

intraocular pressure elevation after surgery (42). In the present study, although CT

changed during the observation period, blood flow density remained

largely stable, suggesting no strong association between the two

parameters. Some studies have also found no clear association

between CT and blood flow (29,43).

Moreover, another study indicated that CT is more closely related

to choroidal vascularity than to choriocapillaris perfusion

(44). Given the structural

complexity of the choroid, evaluating its vascular characteristics

remains challenging, and further research is required to better

understand choroidal vascular responses following corneal

refractive surgery.

The present study also observed postoperative

reductions in AL in both groups. AL elongation and choroidal

thinning are known to correlate closely with myopia progression

(45,46). Peripheral hyperopic defocus in

myopia can further accelerate AL elongation (47), whereas correcting myopia can delay

this progression (48). Chen et

al (49) reported that in

adolescents using orthokeratology lenses, AL growth slowed and CT

increased markedly. Peripheral retinal myopic defocus induced by

orthokeratology has been shown to substantially alter ocular

development and slow myopia progression (10-12).

In the current study, postoperative AL was significantly shorter

than baseline, consistent with the effects observed with

orthokeratology. The IOLMaster 500 (Zeiss AG) used for AL

measurement in the present study calculates the distance from the

anterior corneal surface to the retinal pigment epithelium

(50); corneal refractive surgery

reduces corneal thickness through stromal ablation, which may lead

to shorter AL. The present data also indicated that AL shortening

was correlated with stromal AD. However, Xu et al (29) reported no significant association

between reduced AL and choroidal parameters. Therefore, it cannot

be definitively concluded that AL reduction is related to increased

CT or to changes in retinal myopic defocus.

The present study has several limitations, including

a small sample size and a relatively short follow-up period, which

limited the ability to assess long-term postoperative choroidal

changes. Owing to limitations in imaging sensitivity, blood flow

density in deeper choroidal layers was not assessed. Future studies

should address these aspects for a more comprehensive understanding

of the choroid.

In conclusion, an increase in CT following SMILE and

FS-LASIK surgeries was observed in the present study. However, by

the end of the observation period, CT at most locations had

returned to preoperative levels, indicating that the change was not

sustained. In addition, no significant changes in CD were observed.

The present findings suggest that SMILE and FS-LASIK exert minimal

influence on the choroid.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

The present study was conceived and designed by YL

and SY. The experiments were performed by SY, MT and JZ. The data

were analyzed by SY, TQ, JH and YD. YL contributed materials. SY,

YL and TQ wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the

final manuscript. JZ and YL confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The study protocol adhered to the principles of The

Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the Human Ethics

Committee of Jinan Mingshui Eye Hospital (approval no. 2020-020).

All patients provided written informed consent.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Jonas JB, Panda-Jonas S, Dong L and Jonas

RA: Clinical and anatomical features of myopia. Asia Pac J

Ophthalmol (Phila). 13(100114)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Du Y, Meng J, He W, Qi J, Lu Y and Zhu X:

Complications of high myopia: An update from clinical

manifestations to underlying mechanisms. Adv Ophthalmol Pract Res.

4:156–163. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Landreneau JR, Hesemann NP and Cardonell

MA: Review on the myopia pandemic: Epidemiology, risk factors, and

prevention. Mo Med. 118:156–163. 2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Arnoldi K: Growing pains: The incidence

and prevalence of myopia from 1950 to 2050. J Binocul Vis Ocul

Motil. 74:118–121. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Liang J, Pu Y, Chen J, Liu M, Ouyang B,

Jin Z, Ge W, Wu Z, Yang X, Qin C, et al: Global prevalence, trend

and projection of myopia in children and adolescents from 1990 to

2050: A comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J

Ophthalmol. 109:362–371. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Liu Y, Wang L, Xu Y, Pang Z and Mu G: The

influence of the choroid on the onset and development of myopia:

From perspectives of choroidal thickness and blood flow. Acta

Ophthalmol. 99:730–738. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Brown DM, Mazade R, Clarkson-Townsend D,

Hogan K, Datta Roy PM and Pardue MT: Candidate pathways for retina

to scleral signaling in refractive eye growth. Exp Eye Res.

219(109071)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Ostrin LA, Harb E, Nickla DL, Read SA,

Alonso-Caneiro D, Schroedl F, Kaser-Eichberger A, Zhou X and

Wildsoet CF: IMI-the dynamic choroid: New insights, challenges, and

potential significance for human myopia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci.

64(4)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Jonas JB, Jonas RA, Bikbov MM, Wang YX and

Panda-Jonas S: Myopia: Histology, clinical features, and potential

implications for the etiology of axial elongation. Prog Retin Eye

Res. 96(101156)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Tang T, Lu Y, Li X, Zhao H, Wang K, Li Y

and Zhao M: Comparison of the long-term effects of atropine in

combination with orthokeratology and defocus incorporated multiple

segment lenses for myopia control in Chinese children and

adolescents. Eye (Lond). 38:1660–1667. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Erdinest N, London N, Lavy I, Berkow D,

Landau D, Morad Y and Levinger N: Peripheral defocus and myopia

management: A mini-review. Korean J Ophthalmol. 37:70–81.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Vincent SJ, Cho P, Chan KY, Fadel D,

Ghorbani-Mojarrad N, González-Méijome JM, Johnson L, Kang P,

Michaud L, Simard P and Jones L: CLEAR-orthokeratology. Cont Lens

Anterior Eye. 44:240–269. 2021.

|

|

13

|

Zhang R, Zhuang S, Zhou Y, Chin MP, Sun L,

Jhanji V and Zhang M: Associations between choroidal thickness and

rate of axial elongation in orthokeratology lens users.

Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 51(104450)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Liu M, Huang J, Xie Z, Wang Y, Wang P, Xia

R, Liu X, Su B, Qu J, Zhou X, et al: Dynamic changes of choroidal

vasculature and its association with myopia control efficacy in

children during 1-year orthokeratology treatment. Cont Lens

Anterior Eye. 48(102314)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Wang XQ, Chen M, Zeng LZ and Liu LQ:

Investigation of retinal microvasculature and choriocapillaris in

adolescent myopic patients with astigmatism undergoing

orthokeratology. BMC Ophthalmol. 22(382)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Lin MY, Tan HY and Chang CK: Myopic

regression after FS-LASIK and SMILE. Cornea. 43:1560–1566.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Ramirez-Miranda A, Mota ADL, Rosa GGDL,

Serna-Ojeda JC, Valdez-García JE, Fábregas-Sánchez-Woodworth D,

Navas A, Jiménez-Corona A and Graue-Hernandez EO: Visual and

refractive outcomes after SMILE versus FS-LASIK: A paired-eye

study. Cir Cir. 92:758–768. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Kim BK and Chung YT: Comparison of changes

in corneal thickness and curvature after myopia correction between

SMILE and FS-LASIK. J Refract Surg. 39:15–22. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Khanjian AT, Khodzhabekyan NV, Tarutta EP,

Harutyunyan SG and Milash SV: Changes in the wavefront and

peripheral defocus profile after excimer laser and orthokeratology

corneal reshaping in myopia. Vestn Oftalmol. 139:87–92.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar : (In Russian).

|

|

20

|

Du Y, Zhou Y, Ding M, Zhang M and Guo Y:

Changes in relative peripheral refraction and optical quality in

Chinese myopic patients after small incision lenticule extraction

surgery. PLoS One. 18(e0291681)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Zeppieri M, Marsili S, Enaholo ES, Shuaibu

AO, Uwagboe N, Salati C, Spadea L and Musa M: Optical coherence

tomography (OCT): A brief look at the uses and technological

evolution of ophthalmology. Medicina (Kaunas).

59(2114)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Tan B, Chua J, Wong D, Liu X, Ismail M and

Schmetterer L: Techniques for imaging the choroid and choroidal

blood flow in vivo. Exp Eye Res. 247(110045)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Spaide RF: Choriocapillaris flow features

follow a power law distribution: Implications for characterization

and mechanisms of disease progression. Am J Ophthalmol. 170:58–67.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Singh RB, Perepelkina T, Testi I, Young

BK, Mirza T, Invernizzi A, Biswas J and Agarwal A: Imaging-based

assessment of choriocapillaris: A comprehensive review. Semin

Ophthalmol. 38:405–426. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Stone RA, Tobias JW, Wei W, Carlstedt X,

Zhang L, Iuvone PM and Nickla DL: Diurnal gene expression patterns

in retina and choroid distinguish myopia progression from myopia

onset. PLoS One. 19(e0307091)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

She Z and Gawne TJ: The parameters

governing the anti-myopia efficacy of chromatically simulated

myopic defocus in tree shrews. Transl Vis Sci Technol.

13(6)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Ma JX, Tian SW and Liu QP: Effectiveness

of peripheral defocus spectacle lenses in myopia control: A

meta-analysis and systematic review. Int J Ophthalmol.

15:1699–1706. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Troilo D, Nickla DL and Wildsoet CF:

Choroidal thickness changes during altered eye growth and

refractive state in a primate. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci.

41:1249–1258. 2000.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Xu Z, Gui S, Huang J, Li Y, Lu F and Hu L:

Effect of femtosecond laser in situ keratomileusis on the

choriocapillaris perfusion and choroidal thickness in myopic

patients. Curr Eye Res. 46:878–884. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Zhang J, He FL, Liu Y and Fan XQ:

Comparison of choroidal thickness in high myopic eyes after

FS-LASIK versus implantable collamer lens implantation with

swept-source optical coherence tomography. Int J Ophthalmol.

13:773–781. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Zhu X: Temporal integration of visual

signals in lens compensation (a review). Exp Eye Res. 114:69–76.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Zhang Y and Wildsoet CF: RPE and choroid

mechanisms underlying ocular growth and myopia. Prog Mol Biol

Transl Sci. 134:221–240. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Roy S and Field GD: Dopaminergic

modulation of retinal processing from starlight to sunlight. J

Pharmacol Sci. 140:86–93. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Zhou X, Pardue MT, Iuvone PM and Qu J:

Dopamine signaling and myopia development: What are the key

challenges. Prog Retin Eye Res. 61:60–71. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Cheng D, Qiao YL, Zhu XY, Ruan KM, Lian

HL, Shen MX, Wang SL, Shen LJ and Ye YF: Change in choroid

thickness and vascularity index associated with accommodation and

aberration after small-incision lenticule extraction. Int J

Ophthalmol. 18:672–682. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Gupta P, Jing T, Marziliano P, Cheung CY,

Baskaran M, Lamoureux EL, Wong TY, Cheung CM and Cheng CY:

Distribution and determinants of choroidal thickness and volume

using automated segmentation software in a population-based study.

Am J Ophthalmol. 159:293–301. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Mori Y, Miyake M, Hosoda Y, Uji A, Nakano

E, Takahashi A, Muraoka Y, Miyata M, Tamura H, Ooto S, et al:

Distribution of choroidal thickness and choroidal vessel dilation

in healthy Japanese individuals: The Nagahama study. Ophthalmol

Sci. 1(100033)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Chen Y, Liao H, Sun Y and Shen X:

Short-term changes in the anterior segment and retina after small

incision lenticule extraction. BMC Ophthalmol.

20(397)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Wang P, Hu X, Zhu C, Liu M, Yuan Y and Ke

B: Transient alteration of retinal microvasculature after

refractive surgery. Ophthalmic Res. 64:128–138. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Chen M, Dai J and Gong L: Changes in

retinal vasculature and thickness after small incision lenticule

extraction with optical coherence tomography angiography. J

Ophthalmol. 2019(3693140)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Gandhi S, Pattathil N and Choudhry N:

OCTA: Essential or gimmick? Ophthalmol Ther. 13:2293–2302.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Kiyota N, Shiga Y, Ichinohasama K, Yasuda

M, Aizawa N, Omodaka K, Honda N, Kunikata H and Nakazawa T: The

impact of intraocular pressure elevation on optic nerve head and

choroidal blood flow. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 59:3488–3496.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Sogawa K, Nagaoka T, Takahashi A, Tanano

I, Tani T, Ishibazawa A and Yoshida A: Relationship between

choroidal thickness and choroidal circulation in healthy young

subjects. Am J Ophthalmol. 153:1129–1132.e1. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Wang Y, Liu M, Xie Z, Wang P, Li X, Yao X,

Tian J, Han Y, Chen X, Xu Z, et al: Choroidal circulation in 8- to

30-year-old chinese, measured by SS-OCT/OCTA: Relations to age,

axial length, and choroidal thickness. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci.

64(7)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Tian F, Zheng D, Zhang J, Liu L, Duan J,

Guo Y, Wang Y, Wang S, Sang Y, Zhang X, et al: Choroidal and

retinal thickness and axial eye elongation in Chinese junior

students. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 62(26)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Xie J, Ye L, Chen Q, Shi Y, Hu G, Yin Y,

Zou H, Zhu J, Fan Y, He J and Xu X: Choroidal thickness and its

association with age, axial length, and refractive error in Chinese

adults. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 63(34)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Chakraborty R, Read SA and Collins MJ:

Hyperopic defocus and diurnal changes in human choroid and axial

length. Optom Vis Sci. 90:1187–1198. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Read SA, Collins MJ and Sander BP: Human

optical axial length and defocus. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci.

51:6262–6269. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Chen Z, Xue F, Zhou J, Qu X and Zhou X:

Effects of orthokeratology on choroidal thickness and axial length.

Optom Vis Sci. 93:1064–1071. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Shi Q, Wang GY, Cheng YH and Pei C:

Comparison of IOL-Master 700 and IOL-Master 500 biometers in ocular

biological parameters of adolescents. Int J Ophthalmol.

14:1013–1017. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|