Introduction

Appendiceal mucinous tumours are uncommon and are

detected in only 0.7-1.7% of individuals who undergo an

appendectomy. The preoperative diagnosis of appendiceal myxoma is

difficult and the results of imaging can only be used as a

reference. The diagnosis of the disease in the vast majority of

patients relies on the pathological examination (1). Appendiceal mucinous tumours are

low-grade malignant tumours with a high likelihood of metastatic

dissemination, and the most common type is low-grade appendiceal

mucinous neoplasm, which presents as an adenomatous change in the

appendix (2). The complications of

appendiceal mucinous tumours vary, but to the best of our

knowledge, cases resulting in autoamputation of the appendix have

not been reported. Appendiceal autoamputation is defined as the

separation of part of the appendix in the absence of surgical or

other invasive interventions and was first documented by Judd et

al in 1915(3). The clinical

manifestations of appendiceal mucinous tumours are typically

non-specific and their imaging features exhibit marked

heterogeneity, rendering preoperative diagnosis an arduous task. In

most cases, a conclusive diagnosis can only be achieved through

postoperative pathological examination. Over the past few decades,

extensive research has been conducted on the management of

appendiceal mucinous tumours, leading to the development of

well-established and standardized treatment protocols (4). Ruptured appendiceal mucinous tumours

are typically treated with cytoreductive surgery (CRS) combined

with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) (5); CRS is defined as the surgical removal

of all tumour tissue that is visible to the naked eye, as well as

the exploration of potential sites of involvement, and HIPEC is a

procedure whereby chemotherapeutic agents are dissolved in saline

at temperatures between 42.5-43.5˚C and then injected into the

abdominal cavity at a rate of 400 ml/min. This is achieved through

the use of an automated thermotherapy chemotherapy perfusion

device, with the aim of removing both free tumour cells and mucus

components. This comprehensive approach minimizes the risks of

residual tumour cells and local recurrence, thereby markedly

boosting the long-term survival rate of these patients and

remarkably enhancing their prognosis (6).

The present case report presents a particularly

unique case of appendiceal mucinous tumour. It highlights the

diagnostic challenges associated with this condition, the crucial

role of imaging and pathological examinations in its accurate

diagnosis and the standardized treatment protocol. By delving into

the rarity and complexity of the present case, the aim was to

enhance the clinical understanding of appendiceal mucinous tumours,

improving the ability of general surgeons to recognize, diagnose

and manage such cases in clinical practice.

Case report

A 68-year-old male patient (body mass index, 26.1

kg/m²) presented to the Emergency Department of the Second

Affiliated Hospital of Dalian Medical University (Dalian, China) in

March 2023 with a chief complaint of vague abdominal discomfort in

the right lower quadrant, which had been present for 10 days and

had recently worsened for 1 day. Although the patient took

anti-inflammatory medication prior to admission, the symptoms were

not notably relieved and the patient developed a fever reaching

37.5˚C. The postadmission temperature was 36.7˚C, and the white

blood cell (WBC) count was 11.90x109/l (normal range,

4.0-10.0x109/l). Physical examination revealed pressure

points limited to the right lower abdomen with mild rebound pain,

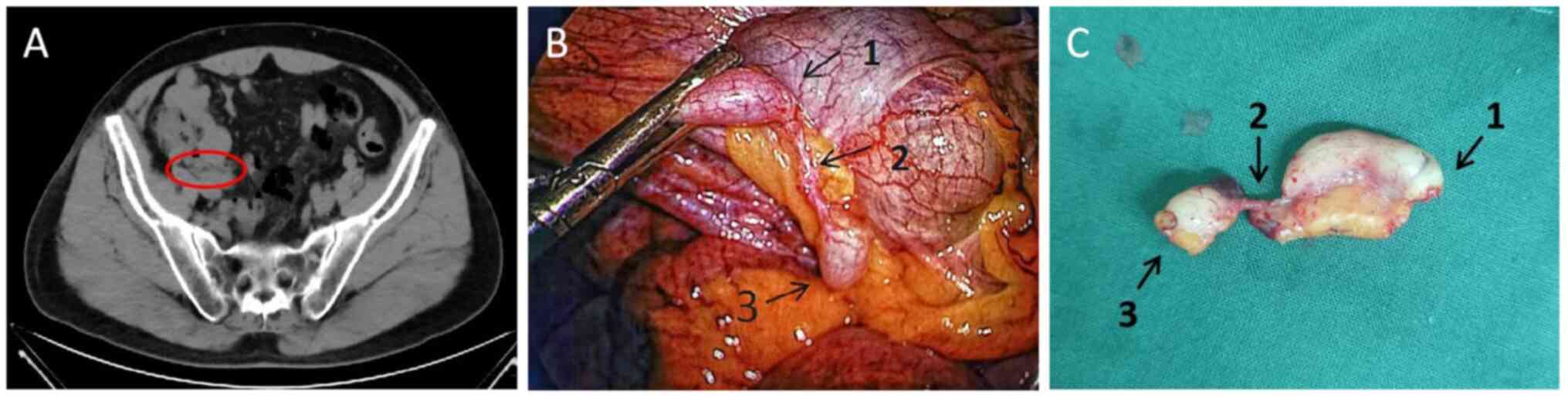

and CT examination revealed exudative effusive changes in the

ileocecal and right iliac fossa regions with adhesions in the

adjacent bowel (Fig. 1A);

additionally, ultrasound revealed the presence of a periappendiceal

inflammatory wrap (Fig. 1B). Based

on the patient's medical history and imaging findings, the appendix

was deemed to have formed complex adhesions with the surrounding

tissues. Following a discussion with the patient and their family,

it was determined that a complete removal of the appendix and

abscess in a single surgical procedure was not feasible;

consequently, a conservative treatment approach was implemented.

The conservative treatment regimen formulated for the patient

comprised the following measures: i) Nil per os (fasting); ii)

intravenous fluid replacement; and iii) anti-inflammatory therapy,

including a meloxicillin sulbactam injection, 3.75 g administered

intravenously every 12 h, with a planned course of 4 days (total

amount, 30 g). Ultrasound was repeated 3 days later, which revealed

that the abscess had decreased in size (Fig. 1C). Following a 6-day course of

treatment, the patient's body temperature returned to normal, the

abdominal pain abated and no compression or rebound pain was

observed upon examination. The patient was discharged from the

hospital in March 2023 in stable condition (WBC count:

3.56x109/l).

The patient was asked to undergo follow-up

examinations, and 3 months after discharge, CT of the abdomen

revealed slight thickening of the appendix and that the surrounding

abscess had disappeared (Fig. 2A).

The patient was readmitted to the hospital in June 2023 with the

expectation of surgical treatment.

Exploration of the operative area revealed a

relatively fixed and locally oozing ileocecal bowel and its

mesentery, and adhesions due to a previous peripheral abscess were

considered. The adherent tissues were not forcibly separated and

thus the appendiceal autoamputation was discovered (Fig. 2B). The appendix was ~5 mm in

diameter, the entire layer was completely dissected, the proximal

end was ~3 cm long and the distal end was ~1 cm long. The two ends

were connected only by the mesentery, and the distance between the

dissected points was ~1.5 cm.

The appendicular artery was visible on the medial

side of the mesentery; additionally, the appendix at both ends of

the dissected point exhibited robust haemato-vascular activity,

with the capillaries discernible on the surface. The lumen

demonstrated slight distension, and neither the proximal nor distal

segments of the appendix presented any evidence of infarction, the

dissected surfaces were entirely sealed. As there was no marked

mucus component observed in the operative area, it was considered

to be a site of appendicitis and therefore the appendix was removed

(Fig. 2C).

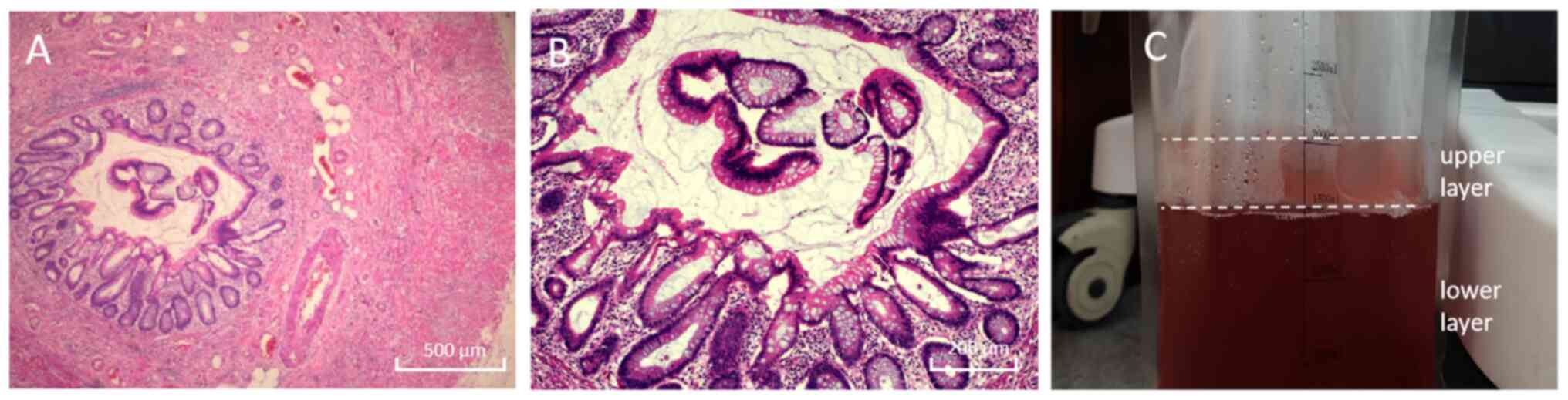

The results of the pathological examination (neutral

buffered formalin; 4% formaldehyde aqueous solution; 20-25˚C; 6-24

h) were returned 3 days later, and indicated a low-grade mucinous

tumour of the appendix (Fig. 3A

and B). The mucosal layer of the

appendix was thickened, with a smooth surface and no notable ulcers

or cauliflower-like protrusions. The appendiceal goblet cells and

mucus-secreting columnar cells were arranged in a columnar or

cuboidal shape, with nuclei located at the basal region of the

cells; the chromatin was uniformly distributed, nucleoli were

inconspicuous, mitotic figures were rare (≤1 per 10 high-power

fields) and no notable cytological atypia was observed. The

appendiceal epithelium and lamina propria were compressed, showing

thinning or even focal absence. Mucus had penetrated the glandular

basement membrane and infiltrated into the muscular layer of the

appendix, and a small number of lymphocytes and plasma cells were

seen infiltrating the area around the serosal layer. The

aforementioned pathological manifestations are consistent with the

pathological characteristics of low-grade appendiceal myxoma

(7).

Following confirmation of the diagnosis, right

hemicolectomy, resection of the greater omentum and partial

peritoneal resection were performed in July 2023 in accordance with

established treatment guidelines (8). Additionally, HIPEC (cisplatin 75

mg/m² for 60 min) was conducted; when HIPEC was performed, the

abdominal lavage fluid was stratified upon standing, with the upper

layer containing clear light red turbid mucus and the lower layer

containing dark red lavage fluid (Fig.

3C).

At 10 days post-surgery, the patient gradually

recovered intestinal function, as evidenced by normal defecation.

The patient was subsequently discharged without any new discomfort

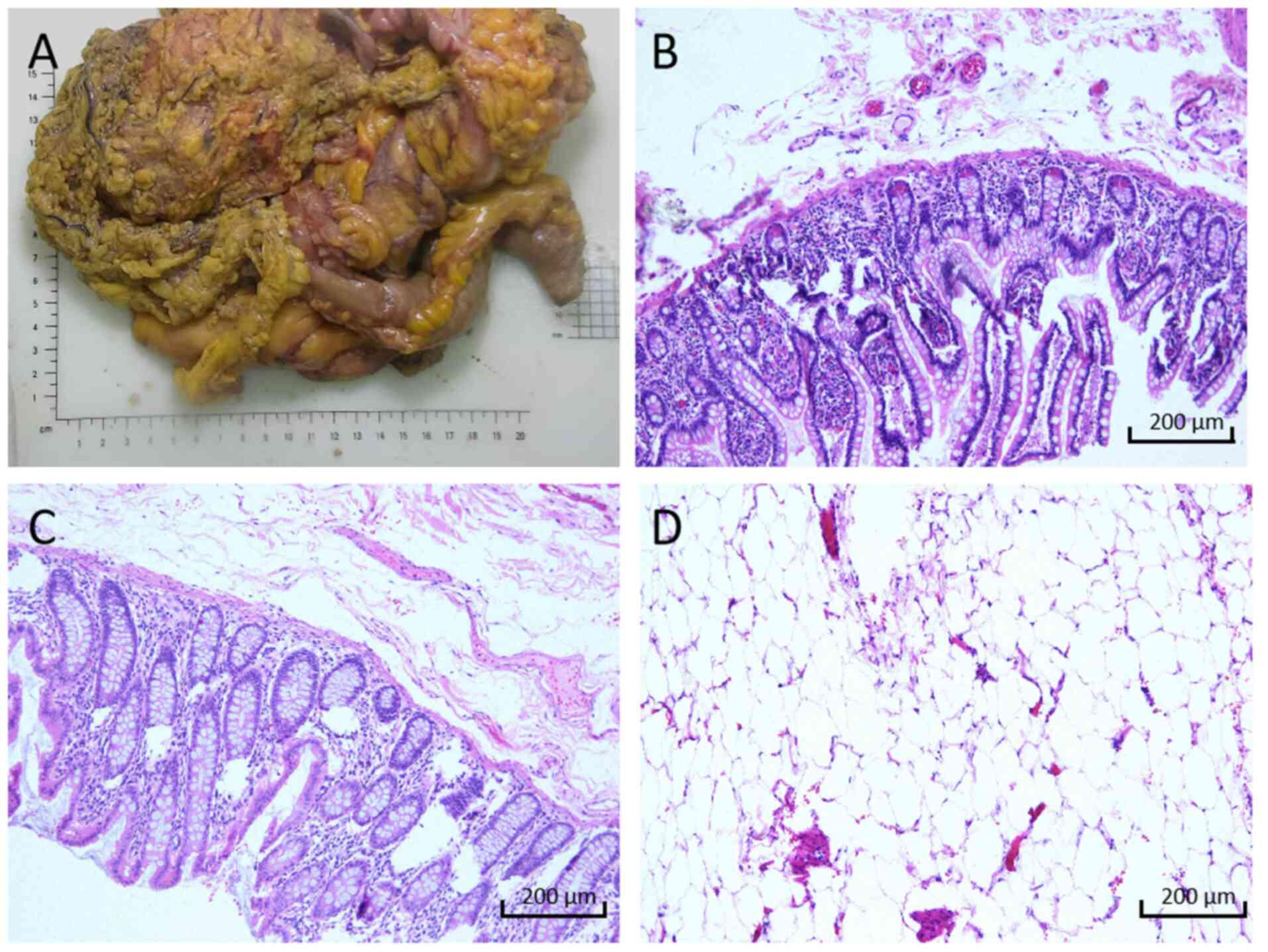

after eating, 10 days after the surgery. Pathological examination

of the appendiceal mucinous tumour revealed the absence of lesional

tissue on the ileocecal side, colonic side of the dissection and

peripheral circumferential margins. Additionally, no lesional

tissue was observed in the peri-intestinal lymph nodes (0/16)

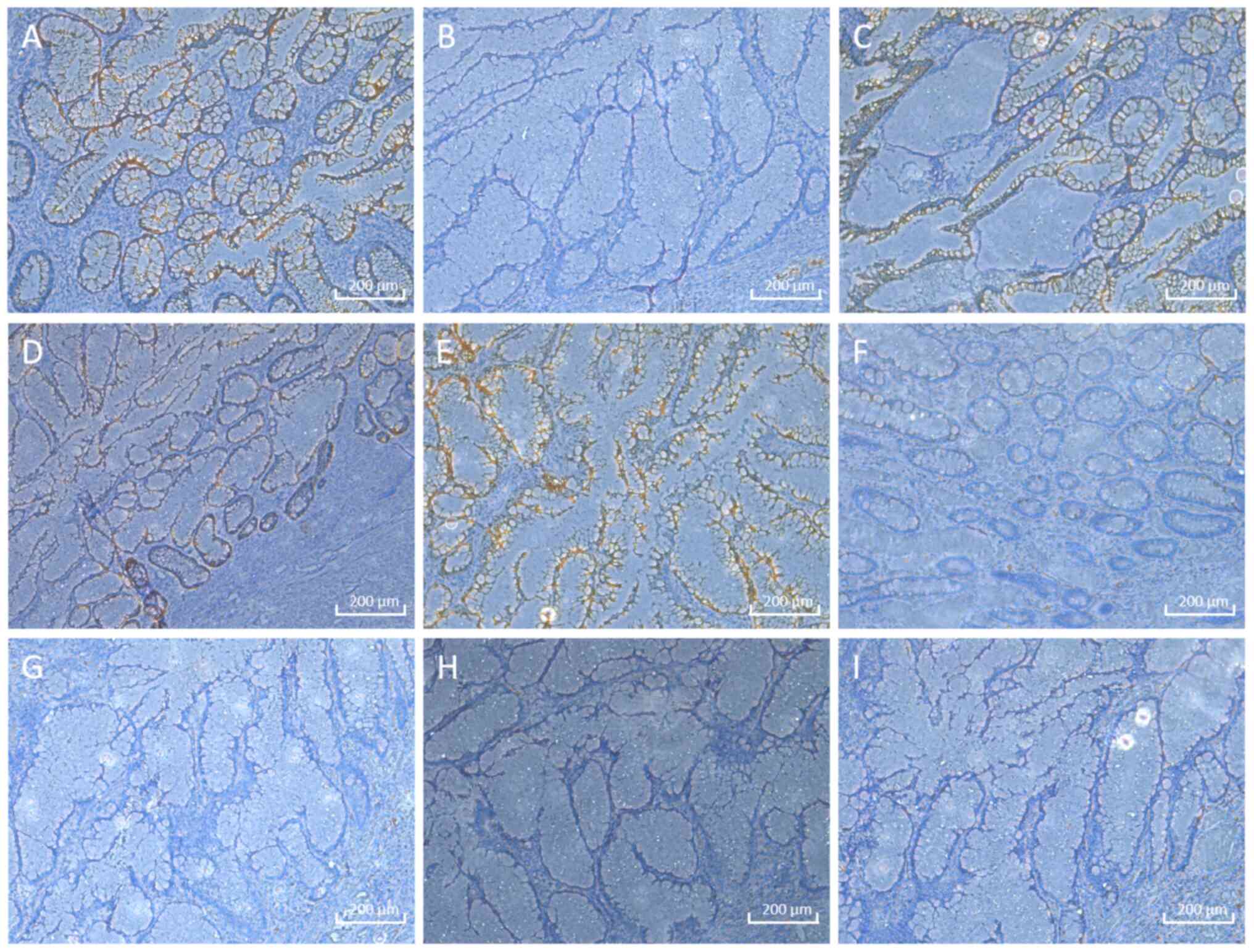

(Fig. 4). Immunohistochemistry was

performed (4% neutral buffered formalin fixative; 20-25˚C for 6-24

h; paraffin-embedded 4- to 5-µm sections), indicating cytokeratin

(CK)-pan+, CK7-, CK20+, caudal

type homeobox 2+, mucin (MUC2)+,

MUC5AC-, paired box (PAX)-2-,

PAX-8- and Ki-67- results (Fig. 5). Primary antibody details were as

follows: CK-pan mouse monoclonal antibody (7H8C4; 1:200; cat. no.

EM1712-42; HUABIO), CK7 recombinant monoclonal antibody (1:2,000;

cat. no. 86153-7-RR; Proteintech Group, Inc.), CK20 recombinant

monoclonal antibody (1:4,000; cat. no. 82428-1-RR; Proteintech

Group, Inc.), CDX2 recombinant monoclonal antibody (1:1,000; cat.

no. 82659-1-RR; Proteintech Group, Inc.), MUC2 polyclonal antibody

(1:2,000; cat. no. 27675-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.), MUC5AC

polyclonal antibody (1:500; cat. no. 20725-1-AP; Proteintech Group,

Inc.), PAX2 polyclonal antibody (1:1,000; cat. no. 29307-1-AP;

Proteintech Group, Inc.), PAX8 polyclonal antibody (1:800; cat. no.

10336-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.) and Ki-67 polyclonal antibody

(1:4,000; cat. no. 27309-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.). Primary

antibodies were incubated at 4˚C for 12 h. Secondary antibody

details were as follows: Multi-rAb® Polymer HRP-Goat

Anti-Rabbit Recombinant Secondary Antibody (H+L) (ready-to-use;

cat. no. RGAR011; Proteintech Group, Inc.), Multi-rAb™ Polymer

HRP-Goat Anti-Mouse Recombinant Secondary Antibody (H+L)

(ready-to-use; cat. no. RGAM011; Proteintech Group, Inc.). The

secondary antibodies were incubated at room temperature for 30

min.

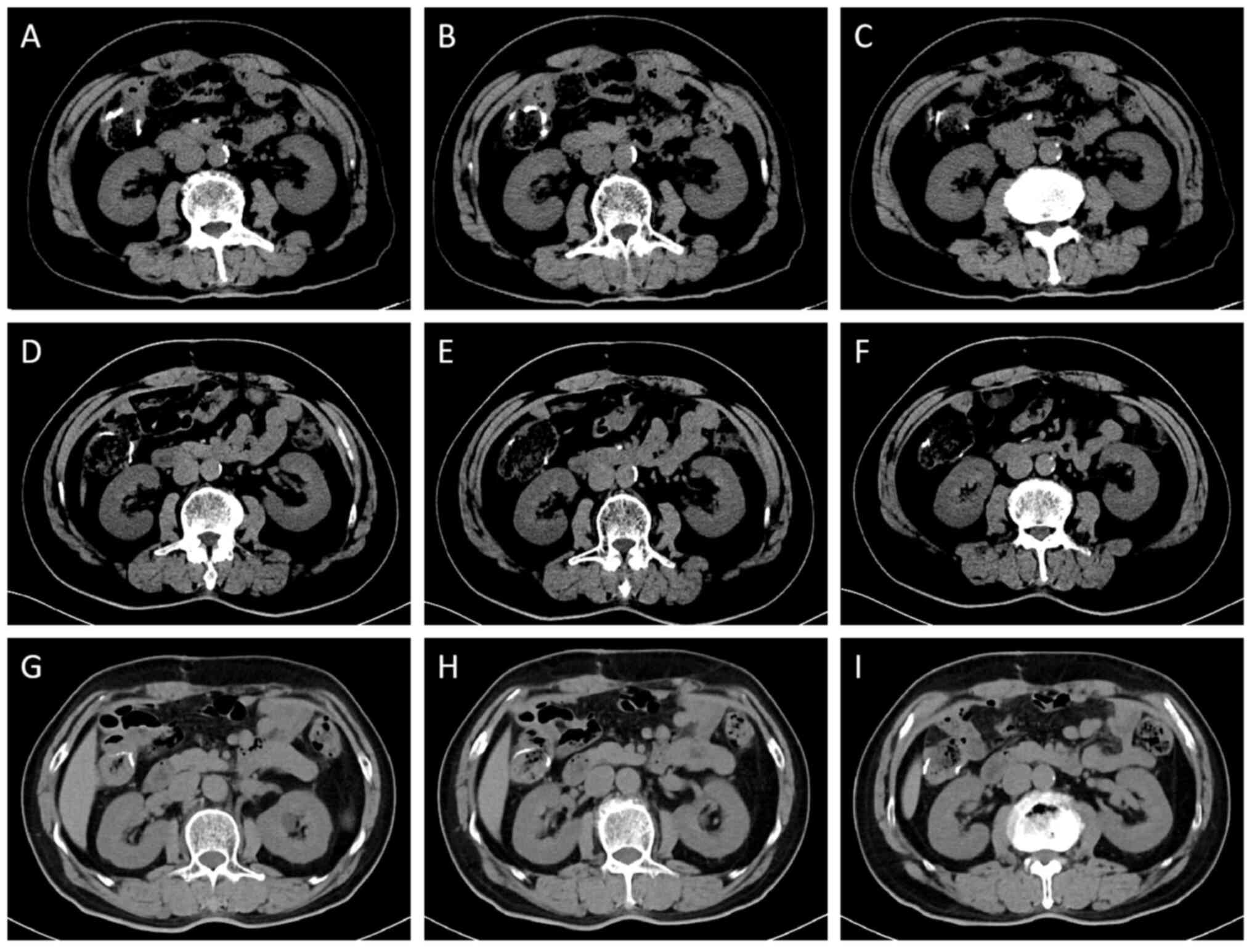

The patient underwent a total of three follow-up

reexaminations from July 2023 to June 2024, mainly including blood

biochemical and CT examinations. The 1-year follow-up after the

right hemicolectomy indicated that the patient had achieved

satisfactory postoperative recovery. Follow-up evaluation

demonstrated the absence of clinical symptoms (such as abdominal

discomfort and gastrointestinal dysfunction); physical examination

revealed normal abdominal signs, including negative tenderness, no

palpable masses, absent rebound tenderness and normal bowel sounds;

laboratory tests showed no abnormal findings: CEA, 0.97 ng/ml

(normal range, <5.0 ng/ml); CA125, 14.53 U/ml (normal range

<25 U/ml); CA19-9: consistently <1.20 U/ml (normal range,

<37 U/ml); and serial CT imaging revealed no evidence of disease

progression or recurrence (Fig.

6). A regular follow-up examination will be performed every

year in the future.

Discussion

In the present case report, a rare case of

appendiceal autoamputation due to an appendiceal mucinous tumour

was reported; the appendix was dissected into two parts, with good

haematology at both ends. An appendiceal mucocele is challenging to

diagnose preoperatively, and initially, it was assumed that the

appendix had autoamputated as a result of inflammation, so an

appendectomy was performed; however, the results of the

postoperative pathological examination revealed a diagnosis of

appendiceal mucocele. The most common presentation of an

appendiceal mucinous tumour is acute appendicitis combined with

perforation. This may present with numerous symptoms, including

abdominal pain (which may be located in the periumbilical area or

extensive abdomen and may progressively migrate to the right lower

abdomen), abdominal distension, an abdominal mass and bloody stool

(4). Most patients present with

atypical clinical manifestations; some individuals present with

lower back pain and ileocecal intestinal obstruction (9-11).

Appendiceal mucinous tumours are diagnosed on the basis of imaging

data and pathological findings. CT allows for straightforward,

rapid assessment of abdominal organs, but diagnosing appendiceal

mucinous tumours on the basis of CT findings alone is challenging

owing to the variable, ambiguous and nonspecific presentation of

these tumours on CT scans. Appendiceal mucinous tumour should be

considered when encountering a focal well-defined cystic mass with

slightly higher than water attenuation, thickened cystic wall with

ring mural enhancement and a characteristic progressive contrast

enhancement on CT imaging (7).

Consequently, a definitive diagnosis is often made on the basis of

incidental intraoperative findings and postoperative pathology.

Intraoperative visualisation of mucus draining from the appendix or

intra-abdominal findings of a distinct mucus component aids in the

pathological diagnosis of an appendiceal mucocele, as do

microscopic observation of villous or flat mucinous epithelial

hyperplasia with low-grade isoforms and a mucin component (1,7). The

immunohistochemical results were as follows: CK20-, MUC2- and

MUC5AC-positive, and PAX-2- and PAX-8-negative, mostly suggestive

of a diagnosis of an appendiceal mucinous tumour (12,13).

The immunohistochemical results were largely consistent with the

typical immunophenotypic characteristics of appendiceal myxoma,

which provides objective evidence for confirming the pathological

diagnosis. In addition, the immunohistochemical results further

provide a basis for the differential diagnosis of this disease, as

follows: i) CK-pan positivity excludes non-epithelial neoplasms,

such as carcinoid tumours, lymphomas and sarcomas (14); ii) CDX2 positivity rules out the

possibility of primary pancreatic myxoma (15); iii) Ki-67 negativity is consistent

with the biological behaviours of low-grade tumours, supporting the

exclusion of high-grade malignant tumours (16); and iv) PAX-2 and PAX-8 negativity

eliminated the possibility of metastatic tumours originating from

the genitourinary system or thyroid (17).

Rupture of an appendiceal mucinous tumour can result

in a variety of complications, but to the best of our knowledge,

cases leading to appendiceal autoamputation have not been reported.

Autoamputation of the appendix has been documented in cases of

appendiceal mucous cysts, gangrenous appendicitis, chronic pelvic

abscesses and blunt abdominal injury (18-22).

The aforementioned cases were identified as intraoperative

autoamputation of the appendix, and the underlying causes and

clinical manifestations of these occurrences exhibited notable

differences (including abdominal pain, calcified masses, fever and

free gas in the abdominal cavity).

The underlying aetiological mechanism of appendiceal

autoamputation resulting from the rupture of an appendiceal

mucinous tumour is the transformation of appendiceal cup cells into

tumour cells, which maintain the expression of mucin throughout the

process of proliferation, leading to the accumulation of mucus in

the appendiceal lumen (23). As

allometric tension increased, the likelihood of appendiceal rupture

and perforation increased concomitantly. Owing to the absence of

cell surface adhesion factors, appendiceal mucus tumour cells are

capable of traversing the abdominal cavity and continuing to

produce mucus (24). A clinical

study showed that ~20% of patients with appendiceal mucinous

tumours experienced appendiceal rupture or perforation, resulting

in the formation of a peritoneal pseudomucinous tumour (PMP)

(25). The 3-, 5- and 10-year

survival rates for patients who develop PMPs are 100, 86 and 45%,

respectively (26).

A review of the literature and relevant case

material revealed that an appendiceal mucocele can be caused by

chronic inflammation over a long period, which was discussed in the

context of the past medical history of the patient in the present

case. The current patient initially presented with a

periappendiceal abscess secondary to appendicitis, and following

anti-inflammatory and other symptomatic treatments, the

inflammation subsided and the abscess was absorbed; however, the

appendiceal inflammation was not resolved. After a prolonged period

of chronic inflammatory stimulation, the appendiceal cup cells

undergo tumour transformation, resulting in the formation of an

appendiceal mucocele, and the mucus produced by the tumour cells

accumulates within the appendiceal lumen. In the presence of

bacterial growth and infection, the appendix becomes gangrenous and

the entire layer of the appendix undergoes necrosis. Autoamputation

of the appendix occurs, and the fractured surface of the lumen

closes after the expulsion of necrotic material and mucus (27).

Treatment options for appendiceal mucinous tumours

have been progressively developed over the years, leading to more

standardized systemic treatment protocols currently in place. For

low-grade appendiceal mucinous tumours confined to the appendix,

the recommended treatment is right hemicolectomy, but for patients

whose appendix has ruptured secondary to PMP, CRS combined with

HIPEC (28,29), a protocol first proposed by Spratt

et al (30) in 1980, is

recommended. According to the guidelines, in the present study, a

right hemicolectomy, resection of the greater omentum and partial

peritoneal resection were performed and the surrounding tissues and

organs were cleared to minimise the risk of missing small lesions

(31,32). Surgery allows extensive removal of

solid tumour tissue but is limited in terms of addressing free

tumour cells and their mucus secretion; therefore, in the present

study, HIPEC was used to compensate for the lack of free tumour

cells and the mucus clearance ability of CRS (33). HIPEC kills tumour cells through the

following processes (34-36):

i) Increasing the concentration of local chemotherapy and enhancing

the direct cytotoxic effect of chemotherapy drugs; ii) causing

microvascular embolism in the tumour tissue, resulting in tissue

ischaemia and necrosis; iii) activating lysosomes to destroy the

cell structure to directly kill tumour cells in the S and M phases

of the cell cycle; and iv) destroying the membrane proteins of

tumour cells at the molecular level, interfering with the synthesis

process of DNA, RNA and proteins.

The CRS + HIPEC regimen combines the advantages of

surgical resection, local chemotherapy, hyperthermia and abdominal

lavage (37-40).

After years of investigation and research, CRS combined with HIPEC

has been identified as the optimal treatment option for patients

with appendiceal mucinous tumours combined with PMP (41). A follow-up analysis of 512 patients

with appendiceal mucinous tumours secondary to PMP who underwent

CRS combined with HIPEC was performed. Among these patients, ~25%

experienced recurrence, 375 were recurrence-free, 35 underwent

reoperation and 102 experienced recurrence but did not undergo

surgery. The 5-year survival rates were 90.9, 79.0 and 64.5%,

respectively (42).

In conclusion, the present case report describes a

rare case of an appendiceal mucinous tumour leading to

autoamputation of the appendix. The present report presents a

detailed analysis of the mechanism underlying the development of

appendiceal mucinous tumours, accompanied by a concise overview of

the literature on this subject. In addition, diagnosing appendiceal

mucinous tumours preoperatively is challenging, with the

specificity of the most commonly used imaging tests being

suboptimal. It is therefore recommended that full exploration of

the abdominal cavity and intraoperative frozen pathology is

conducted when the abdominal cavity is clear and the risk of

collateral injuries is low. This will facilitate an early

definitive diagnosis and standardise treatment, thus reducing

recurrence rates and prolonging survival.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

The present study was conceptualised by all authors.

CW and YuL wrote the manuscript and collected the data. CW, YuL, ZC

and SN designed and performed the analysis. YaL, BLi, Blu and XH

contributed to the acquisition and interpretation of data. All

authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

CW and YuL confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was conducted according to the

guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and ethical review and

approval was waived for the single case report (Ethics Office, the

Second Affiliated Hospital of Dalian Medical University, Dalian,

China).

Patient consent for publication

Patient characteristics have been anonymized in

compliance with ethical standards. Written informed consent was

obtained from the next of kin for the publication of any associated

images or patient data.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Kawecka W, Adamiak-Godlewska A, Lewkowicz

D, Urbańska K and Semczuk A: Diagnostic difficulties in the

differentiation between an ovarian metastatic low-grade appendiceal

mucinous neoplasm and primary ovarian mucinous cancer: A case

report and literature review. Oncol Lett. 28(500)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Kabbani W, Houlihan PS, Luthra R, Hamilton

SR and Rashid A: Mucinous and nonmucinous appendiceal

adenocarcinomas: Different clinicopathological features but similar

genetic alterations. Mod Pathol. 15:599–605. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Judd JR: A specimen of ‘auto-amputation’

of the appendix. JAMA. 65(1179)1915.

|

|

4

|

Shaib WL, Assi R, Shamseddine A, Alese OB,

Staley C III, Memis B, Adsay V, Bekaii-Saab T and El-Rayes BF:

Appendiceal mucinous neoplasms: Diagnosis and management.

Oncologist. 22:1107–1116. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Chow FC, Yip J, Foo DC, Wei R, Choi HK, Ng

KK and Lo OS: Cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic

intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) for colorectal and appendiceal

peritoneal metastases-The Hong Kong experience and literature

review. Asian J Surg. 44:221–228. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Auer RC, Sivajohanathan D, Biagi J, Conner

J, Kennedy E and May T: Indications for hyperthermic

intraperitoneal chemotherapy with cytoreductive surgery: A

systematic review. Eur J Cancer. 127:76–95. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Yu XR, Mao J, Tang W, Meng XY, Tian Y and

Du ZL: Low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasms confined to the

appendix: Clinical manifestations and CT findings. J Investig Med.

68:75–81. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Govaerts K, Lurvink RJ, De Hingh IHJT, Van

der Speeten K, Villeneuve L, Kusamura S, Kepenekian V, Deraco M,

Glehen O and Moran BJ: PSOGI. Appendiceal tumours and pseudomyxoma

peritonei: Literature review with PSOGI/EURACAN clinical practice

guidelines for diagnosis and treatment. Eur J Surg Oncol. 47:11–35.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Mannarini M, Maselli F, Giannotta G,

Cioeta M and Giovannico G: Low back pain as main symptom in

Low-grade Appendiceal Mucinous Neoplasm (LAMN): A case report.

Physiother Theory Pract. 41:230–238. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Liapis SC, Perivoliotis K, Psarianos K,

Chatzinikolaou C, Moula AI, Skoufogiannis P, Balogiannis I and

Lytras D: A giant low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm (LAMN)

presenting as ileocecal intussusception: A case report. J Surg Case

Rep. 2023(rjad273)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Komo T, Kohashi T, Hihara J, Oishi K,

Yoshimitsu M, Kanou M, Nakashima A, Aoki Y, Miguchi M, Kaneko M, et

al: Intestinal obstruction caused by Low-grade appendiceal mucinous

neoplasm: A case report and review of the literature. Int J Surg

Case Rep. 51:37–40. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Ji H, Isacson C, Seidman JD, Kurman RJ and

Ronnett BM: Cytokeratins 7and 20, Dpc4, and MUC5AC in the

distinction of metastatic mucinous carcinomas in the ovary

fromprimary ovarian mucinous tumors: Dpc4 assists in identifying

metastatic pancreatic carcinomas. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 21:391–400.

2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Dundr P, Singh N, Nozickova B, Nemejcova

K, Bartu M and Struzinska I: Primary mucinous ovarian tumors vs.

ovarian metastases from gastrointestinal tract, pancreas and

biliary tree: A review of current problematics. Diagn Pathol.

16(20)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Son EM, Kim JY, An S, Song KB, Kim SC, Yu

E and Hong SM: Clinical and prognostic significances of cytokeratin

19 and KIT expression in surgically resectable pancreatic

neuroendocrine tumors. J Pathol Transl Med. 49:30–36.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Chu PG, Schwarz RE, Lau SK, Yen Y and

Weiss LM: Immunohistochemical staining in the diagnosis of

pancreatobiliary and ampulla of Vater adenocarcinoma: Application

of CDX2, CK17, MUC1, and MUC2. Am J Surg Pathol. 29:359–367.

2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Kalvala J, Parks RM, Green AR and Cheung

KL: Concordance between core needle biopsy and surgical excision

specimens for Ki-67 in breast cancer-a systematic review of the

literature. Histopathology. 80:468–484. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Ozcan A, de la Roza G, Ro JY, Shen SS and

Truong LD: PAX2 and PAX8 expression in primary and metastatic renal

tumors: A comprehensive comparison. Arch Pathol Lab Med.

136:1541–1551. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Sachs L and Hoffman E: Autoamputation in

mucocele of the appendix. AMA Arch Surg. 63:712–714.

1951.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Lovrenski J, Jokić R and Varga I:

Sonographically detected free appendicolith as a sign of retrocecal

perforated appendicitis in a 2-year-old child. J Clin Ultrasound.

44:395–398. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Weil BR, Al-Ibraheemi A, Vargas SO and

Rangel SJ: Autoamputation of the appendix presenting as a calcified

abdominal mass following necrotizing enterocolitis. Pediatr Dev

Pathol. 20:335–339. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Markey CM and Vestal LE: Autoamputation of

the appendix in a chronic adnexal abscess. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol.

2018(6010568)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Sharma K, Tomar S, Sharma S and Bajpai M:

Floating appendix: Post-traumatic amputation of the appendix as

sequela or complication?: A case report. J Med Case Rep.

15(192)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Legué LM, Creemers GJ, de Hingh IHJT,

Lemmens VEPP and Huysentruyt CJ: Review: Pathology and its clinical

relevance of mucinous appendiceal neoplasms and pseudomyxoma

peritonei. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 18:1–7. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Hinson FL and Ambrose NS: Pseudomyxoma

peritonei. Br J Surg. 85:1332–1339. 1998.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Smeenk RM, van Velthuysen ML, Verwaal VJ

and Zoetmulder FAN: Appendiceal neoplasms and pseudomyxoma

peritonei: A population based study. Eur J Surg Oncol. 34:196–201.

2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Misdraji J, Yantiss RK, Graeme-Cook FM,

Balis UJ and Young RH: Appendiceal mucinous neoplasms: A

clinicopathologic analysis of 107 cases. Am J Surg Pathol.

27:1089–1103. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Zerem E, Salkic N, Imamovic G and Terzić

I: Comparison of therapeutic effectiveness of percutaneous drainage

with antibiotics versus antibiotics alone in the treatment of

periappendiceal abscess: Is appendectomy always necessary after

perforation of appendix? Surg Endosc. 21:461–466. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

McDonald JR, O'Dwyer ST, Rout S,

Chakrabarty B, Sikand K, Fulford PE, Wilson MS and Renehan AG:

Classification of and cytoreductive surgery for Low-grade

appendiceal mucinous neoplasms. Br J Surg. 99:987–92.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Huang Y, Alzahrani NA, Chua TC and Morris

DL: Histological subtype remains a significant prognostic factor

for survival outcomes in patients with appendiceal mucinous

neoplasm with peritoneal dissemination. Dis Colon Rectum.

60:360–367. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Spratt JS, Adcock RA, Muskovin M, Sherrill

W and McKeown J: Clinical delivery system for intraperitoneal

hyperthermic chemotherapy. Cancer Res. 40:256–260. 1980.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Sugarbaker PH: Pont hepatique (hepatic

bridge), an important anatomic structure in cytoreductive surgery.

J Surg Oncol. 101:251–252. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Somashekhar SP, Ashwin KR, Yethadka R,

Zaveri SS, Ahuja VK, Rauthan A and Rohit KC: Impact of extent of

parietal peritonectomy on oncological outcome after cytoreductive

surgery and HIPEC. Pleura Peritoneum. 4(20190015)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Li Y, Zhou YF, Liang H, Wang HQ, Hao JH,

Zhu ZG, Wan DS, Qin LX, Cui SZ, Ji JF, et al: Chinese expert

consensus on cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal

chemotherapy for peritoneal malignancies. World J Gastroenterol.

22:6906–6916. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Gonzalez-Moreno S, Gonzalez-Bayon LA and

Ortega-Perez G: Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy:

Rationale and technique. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2:68–75.

2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Glehen O, Osinsky D, Cotte E, Kwiatkowski

F, Freyer G, Isaac S, Trillet-Lenoir V, Sayag-Beaujard AC, François

Y, Vignal J and Gilly FN: Intraperitoneal chemohyperthermia using a

closed abdominal procedure and cytoreductive surgery for the

treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis: Morbidity and mortality

analysis of 216 consecutive procedures. Ann Surg Oncol. 10:863–869.

2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Elias D, Bonnay M, Puizillou JM, Antoun S,

Demirdjian S, El OA, Pignon JP, Drouard-Troalen L, Ouellet JF and

Ducreux M: Heated intraoperative intraperitoneal oxaliplatin after

complete resection of peritoneal carcinomatosis: Pharmacokinetics

and tissue distribution. Ann Oncol. 13:267–272. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

El-Kareh AW and Secomb TW: A theoretical

model for intraperitoneal delivery of cisplatin and the effect of

hyperthermia on drug penetration distance. Neoplasia. 6:117–127.

2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Sinukumar S, Mehta S, As R, Damodaran D,

Ray M, Zaveri S, Kammar P and Bhatt A: . Analysis of clinical

outcomes of pseudomyxoma peritonei from appendicular origin

following cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal

Chemotherapy-A Retrospective study from INDEPSO. Indian J Surg

Oncol. 10 (Suppl 1):S65–S70. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Wahba R, Schmidt T, Buchner D, Wagner T

and Bruns CJ: Surgical treatment of pseudomyxoma

peritonei-Cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal

chemotherapy. Chirurgie (Heidelb). 94:840–844. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar : (In German).

|

|

40

|

Baratti D, Kusamura S, Guaglio M, Milione

M, Pietrantonio F, Cavalleri T, Morano F and Deraco M: Relapse of

pseudomyxoma peritonei after cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic

intraperitoneal chemotherapy: Pattern of failure, clinical

management and outcomes. Ann Surg Oncol. 30:404–414.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Kusamura S, Barretta F, Yonemura Y,

Sugarbaker PH, Moran BJ, Levine EA, Goere D, Baratti D, Nizri E,

Morris DL, et al: The role of hyperthermic intraperitoneal

chemotherapy in pseudomyxoma peritonei after cytoreductive surgery.

JAMA Surg. 156(e206363)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Lord AC, Shihab O, Chandrakumaran K,

Mohamed F, Cecil TD and Moran BJ: Recurrence and outcome after

complete tumour removal and hyperthermic intraperitoneal

chemotherapy in 512 patients with pseudomyxoma peritonei from

perforated appendiceal mucinous tumours. Eur J Surg Oncol.

41:396–399. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|