Introduction

Bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) is a chronic lung

disease that remains a notable cause of morbidity in preterm

infants, particularly those born at low gestational ages (<28

weeks) or with very low birth weight (<1,000 g). Globally, among

infants born at <28 weeks' gestation, reported incidence of BPD

ranges from 10 to 89% depending on region and definition, with

population-based rates in recent meta-analyses of very low birth

weight (<1,500 g) or very low gestational age (<32 weeks)

neonates estimated at approximately 21% (95% CI 19-24%) (1). Despite advances in neonatal intensive

care, the incidence of BPD has not markedly declined, largely due

to the increased survival of extremely preterm infants who remain

at the highest risk (2-4).

BPD is characterized by abnormal alveolar and vascular development,

resulting from a complex interplay of antenatal, perinatal and

postnatal factors, including inflammation, oxygen toxicity,

mechanical ventilation and sepsis (5).

Early identification of infants at high risk for BPD

is crucial for optimizing management strategies and minimizing

long-term complications such as recurrent wheezing, reduced

pulmonary function, asthma-like symptoms, feeding difficulties,

growth failure, and neurodevelopmental impairments including

cognitive delays, motor dysfunction, and increased risk of cerebral

palsy (6,7). However, the current diagnostic

criteria for BPD, as updated by the National Institute of Child

Health and Human Development (NICHD) in 2018, rely on the need for

respiratory support or supplemental oxygen at 36 weeks

postmenstrual age, which is defined as gestational age at birth

plus the infant's postnatal age. Because this assessment point

occurs after birth, it limits the usefulness of the criteria for

early risk stratification (8,9).

This highlights the need for early-stage predictive tools to

identify high-risk infants before BPD diagnosis is clinically

confirmed.

Previous studies have explored risk factors for BPD,

such as gestational age, birth weight and exposure to invasive

ventilation. However, to the best of our knowledge, few studies

have integrated these variables into a comprehensive, clinically

applicable prediction model (10-12).

Furthermore, the utility of advanced statistical tools such as

nomograms in quantifying individualized risk has been underexplored

in neonatal populations. Nomograms provide a graphical

representation of complex statistical models, and are particularly

valuable in clinical practice for their simplicity and

interpretability (13).

The present study aimed to develop and validate a

robust risk prediction model for BPD in preterm infants,

incorporating readily available clinical and demographic variables.

Using a retrospective cohort of 120 preterm infants, a nomogram was

constructed to estimate individualized risk, and its performance

was evaluated in terms of discrimination, calibration and internal

validation. The present model aimed to provide an early and

accurate assessment of BPD risk, thereby supporting clinical

decision-making and improving outcomes for preterm infants.

Patients and methods

Study design and population

The present retrospective cohort study was conducted

to develop and validate a prediction model for BPD in preterm

infants. Data were collected from 120 preterm infants admitted to

the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) of The Affiliated Hospital

of Southwest Medical University, Luzhou, Sichuan, China, between

January 2020 and December 2022. Infants were stratified into two

groups based on their BPD status, defined according to the 2018

diagnostic criteria published by the NICHD: A BPD group (n=34) and

a non-BPD group (n=86).

Inclusion criteria included preterm infants with

gestational ages <32 weeks and birth weights ≤2,500 g who were

admitted to the NICU within the first week of life. Exclusion

criteria included i) major congenital anomalies or chromosomal

abnormalities; ii) severe congenital heart defects; iii) genetic or

metabolic disorders; iv) mortality or discharge before 14 days of

life; and v) transfer to another hospital within 7 days of birth.

During the study period (January 2020-December 2022), a total of

156 preterm infants with gestational age <32 weeks were admitted

to the NICU of The Affiliated Hospital, Southwest Medical

University (Luzhou, China). Of these, 36 patients were excluded for

the following reasons: Major congenital anomalies or chromosomal

abnormalities (n=5), severe congenital heart defects (n=4), genetic

or metabolic disorder (n=2), early mortality or discharge before 14

days of life (n=15) and transfer to another hospital within 7 days

of birth (n=10). The final analysis therefore included 120 infants,

representing an inclusion rate of 76.9%. Ethical approval for the

study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of The

Affiliated Hospital, Southwest Medical University (approval no.

KY2025055), and informed consent was waived due to the

retrospective nature of the study.

Data collection

Clinical and demographic data were collected from

electronic medical records. Maternal factors included maternal age

(years), parity, pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI,

kg/m2) and the presence of chronic medical conditions

such as hypertension, diabetes or thyroid disease. Antenatal

corticosteroid administration was recorded in detail, including

whether any course was received, the specific agent used

(betamethasone or dexamethasone) and whether the course was

complete or partial according to the standardized institutional

protocol. Chorioamnionitis was diagnosed through clinical or

histopathological findings. The mode of delivery (vaginal or

cesarean section) was also documented. Neonatal characteristics

encompassed gestational age measured in completed weeks, birth

weight in grams, sex, and Apgar scores at 1 and 5 min, which were

documented to assess immediate postnatal adaptation (14). Detailed respiratory support data

were obtained, including the duration (in days) and type of support

provided, such as continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP),

non-invasive positive pressure ventilation (NIPPV) and

high-frequency oscillatory ventilation (HFOV). Additionally,

neonatal comorbidities were recorded, including the occurrence of

sepsis confirmed by positive blood cultures or clinical diagnosis,

patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) diagnosed via echocardiography,

intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH, graded using Papile's

classification) and necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC, identified

based on modified Bell's criteria) (15). For the purposes of the prediction

model, these comorbidities were defined as events occurring within

the first 14 days of life, ensuring that only early-onset cases

were included to maintain the model's utility for early risk

stratification of BPD. Although the formal definitions for sepsis,

PDA, IVH and NEC in the present dataset were restricted to events

occurring within the first 14 days of life, in clinical practice,

the majority of these conditions in the present cohort were either

diagnosed or strongly suspected within the first 72 h after birth,

based on early clinical signs, laboratory findings, and

echocardiographic or cranial ultrasound assessments. Therefore,

these variables retain practical utility for early postnatal risk

stratification. Finally, key outcome measures included the length

of hospital stay (in days) and the presence or absence of BPD,

defined according to the 2018 NICHD criteria. This comprehensive

dataset provided a robust foundation for analyzing factors

contributing to BPD in preterm infants.

During the study period, respiratory management in

the NICU followed a standardized protocol based on gestational age,

respiratory distress severity and oxygen requirements. Initial

support typically involved CPAP for infants with mild-to-moderate

respiratory distress. NIPPV was applied when CPAP was insufficient,

or in cases of apnea or moderate respiratory acidosis. HFOV was

typically initiated in cases of severe respiratory failure or

persistent hypercapnia despite conventional support. Intubation and

mechanical ventilation were considered in cases of refractory

hypoxemia, recurrent apnea unresponsive to non-invasive support or

clinical deterioration. Decisions regarding escalation or

de-escalation of support were made collaboratively by the attending

neonatologist and the respiratory team based on ongoing clinical

assessments.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted to summarize

baseline characteristics, develop a predictive model and evaluate

its performance. Baseline characteristics were described using the

mean ± standard deviation for normally distributed continuous

variables, median (interquartile range) for non-normally

distributed continuous variables and frequencies (percentages) for

categorical variables. Comparisons between groups were performed

using independent Student's t-tests for normally distributed

continuous variables, the Mann-Whitney U test for non-normally

distributed variables, and χ2 or Fisher's exact tests

for categorical variables. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference. Univariate logistic

regression analyses were used to assess the association between

each predictor variable and the risk of BPD. Prior to multivariate

modeling, collinearity among candidate predictors (particularly

gestational age and birth weight) was assessed using variance

inflation factors (VIFs). All VIF values were <2, indicating no

significant multicollinearity. Variables with P<0.1 in

univariate analysis were included in a multivariate logistic

regression model, where a stepwise backward elimination approach

was applied to identify independent predictors. The results were

expressed as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

To evaluate model performance, discrimination was assessed using a

receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve, with calculation of

the area under the curve (AUC), while calibration was evaluated

using a calibration curve comparing predicted and observed

probabilities. The Hosmer-Lemeshow test was used to assess

goodness-of-fit. Based on the multivariate logistic regression

model, a nomogram was constructed to visually represent the BPD

risk prediction tool. Points were assigned to each predictor based

on the magnitude of regression coefficients in the multivariable

logistic regression model, with the predictor contributing the

largest coefficient scaled to 100 points and other predictors

allocated proportionally. The total points were then mapped onto

the corresponding predicted probability of BPD. Internal validation

of the nomogram was performed using bootstrapping with 1,000

resamples to ensure robustness. All analyses were conducted using R

software (version 4.2.2; Posit Software, PBC), with the ‘rms’ and

‘pROC’ packages utilized for nomogram construction and ROC curve

analysis (16,17). There were no missing data for the

variables included in the analysis; therefore, no imputation or

exclusion due to missingness was required.

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 120 preterm infants were included in the

analysis, of whom 34 (28.3%) developed BPD. The baseline

characteristics of the study population stratified by BPD status

are summarized in Table I. There

were no significant differences between the two groups in terms of

maternal characteristics, including age, primiparity, pre-pregnancy

BMI or prevalence of chronic medical conditions such as

hypertension or diabetes. Antenatal corticosteroid exposure was

also comparable between groups, with similar proportions receiving

any corticosteroid, similar distributions of specific agents

(betamethasone or dexamethasone) and no difference in the

proportion of patients completing the full treatment course.

Infants in the BPD group had significantly lower gestational age

(28.02±1.05 vs. 29.29±1.70 weeks; P<0.001) and lower median

birth weight (1,036.3 vs. 1,244.7 g; P<0.001) compared with

those in the non-BPD group. CPAP use was significantly less

frequent in the BPD group (35.3 vs. 59.3%; P=0.018) than in the

non-BPD group, whereas HFOV use was more common (35.3 vs. 17.4%;

P=0.035). Comorbidities, including sepsis (58.8 vs. 8.1%;

P<0.001), PDA (55.9 vs. 29.1%; P=0.006), IVH (29.4 vs. 11.6%;

P=0.018) and NEC (23.5 vs. 5.8%; P=0.013), were significantly more

prevalent in the BPD group than in the non-BPD group. The median

length of hospital stay was significantly longer among infants with

BPD (69.5 vs. 34 days; P<0.001).

| Table IBaseline characteristics of the study

population stratified by BPD status. |

Table I

Baseline characteristics of the study

population stratified by BPD status.

| Characteristic | Non-BPD (n=86) | BPD (n=34) | P-value |

|---|

| Maternal

characteristics | | | |

|

Maternal

age, years (mean ± SD) | 29.7±4.8 | 30.1±5.1 | 0.642 |

|

Primiparity

(%) | 49 (57.0) | 18 (52.9) | 0.683 |

|

Chronic

hypertension, n (%) | 6 (7.0) | 4 (11.8) | 0.462 |

|

Diabetes

mellitus, n (%) | 8 (9.3) | 3 (8.8) | >0.999 |

|

Pre-pregnancy

BMI, kg/m² (mean ± SD) | 22.9±3.4 | 23.4±3.6 | 0.514 |

|

Antenatal

corticosteroids use | | | |

|

Any,

n (%) | 64 (81.7) | 27 (79.4) | 0.565 |

|

Betamethasone,

n (%) | 39 (45.3) | 16 (47.1) | 0.859 |

|

Dexamethasone,

n (%) | 25 (29.1) | 11 (32.4) | 0.815 |

|

Complete

course, n (%) | 58 (67.4) | 24 (70.6) | 0.753 |

| Neonatal

characteristics | | | |

|

Gestational

age, weeks (mean ± SD) | 29.29±1.70 | 28.02±1.05 | <0.001 |

|

Birth

weight, g [median (IQR)] | 1,244.7

(989.9-1,354.0) | 1,036.3

(890.2-1,123.2) | <0.001 |

|

Male sex, n

(%) | 45 (52.3) | 22 (64.7) | 0.218 |

| Respiratory support

use | | | |

|

CPAP, n

(%) | 51 (59.3) | 12 (35.3) | 0.018 |

|

NIPPV, n

(%) | 37 (43.0) | 21 (61.8) | 0.064 |

|

HFOV, n

(%) | 15 (17.4) | 12 (35.3) | 0.035 |

| Comorbidities | | | |

|

Sepsis, n

(%) | 7 (8.1) | 20 (58.8) | <0.001 |

|

PDA, n

(%) | 25 (29.1) | 19 (55.9) | 0.006 |

|

IVH, n

(%) | 10 (11.6) | 10 (29.4) | 0.018 |

|

NEC, n

(%) | 5 (5.8) | 8 (23.5) | 0.013 |

| Length of stay,

days [median (IQR)] | 34.0

(31.0-37.0) | 69.5

(67.0-72.8) | <0.001 |

Univariate and multivariate

analyses

The results of univariate and multivariate logistic

regression analyses for predictors of BPD are presented in Table II. In the univariate analysis,

lower gestational age, lower birth weight, absence of CPAP, use of

HFOV, and presence of sepsis, PDA, IVH and NEC were significantly

associated with an increased risk of BPD (P<0.05 for all). In

the multivariate model, lower gestational age (OR=0.625; 95% CI,

0.420-0.932; P=0.021), sepsis (OR=12.847; 95% CI, 3.187-51.789;

P<0.001), PDA (OR=4.514; 95% CI, 1.324-15.389; P=0.016) and IVH

(OR=5.926; 95% CI, 1.217-28.845; P=0.028) remained independent

predictors of BPD. Although birth weight did not reach statistical

significance in the multivariate model (OR=0.997; P=0.059), it was

retained due to its established clinical importance in neonatal

outcome prediction (18).

| Table IIUnivariate and multivariate logistic

regression analyses of risk factors for bronchopulmonary

dysplasia. |

Table II

Univariate and multivariate logistic

regression analyses of risk factors for bronchopulmonary

dysplasia.

| Characteristic | Univariate OR (95%

CI) | P-value | Multivariate OR

(95% CI) | P-value |

|---|

| Gestational age,

weeks | 0.570

(0.419-0.777) | <0.001 | 0.625

(0.420-0.932) | 0.021 |

| Birth weight,

g | 0.997

(0.994-0.999) | <0.001 | 0.997

(0.994-1.000) | 0.059 |

| Male sex | 1.670

(0.735-3.796) | 0.221 | - | - |

| Antenatal

steroids | 1.326

(0.507-3.470) | 0.566 | - | - |

| CPAP use | 2.671

(1.171-6.093) | 0.020 | 2.158

(0.656-7.098) | 0.205 |

| NIPPV use | 2.139

(0.949-4.822) | 0.067 | 2.458

(0.731-8.271) | 0.146 |

| HFOV use | 2.582

(1.053-6.332) | 0.038 | 1.725

(0.440-6.758) | 0.434 |

| Sepsis | 16.122

(5.748-45.225) | <0.001 | 12.847

(3.187-51.789) | <0.001 |

| PDA | 3.091

(1.359-7.028) | 0.007 | 4.514

(1.324-15.389) | 0.016 |

| IVH | 3.167

(1.177-8.517) | 0.022 | 5.926

(1.217-28.845) | 0.028 |

| NEC | 4.985

(1.499-16.575) | 0.009 | 3.663

(0.718-18.698) | 0.119 |

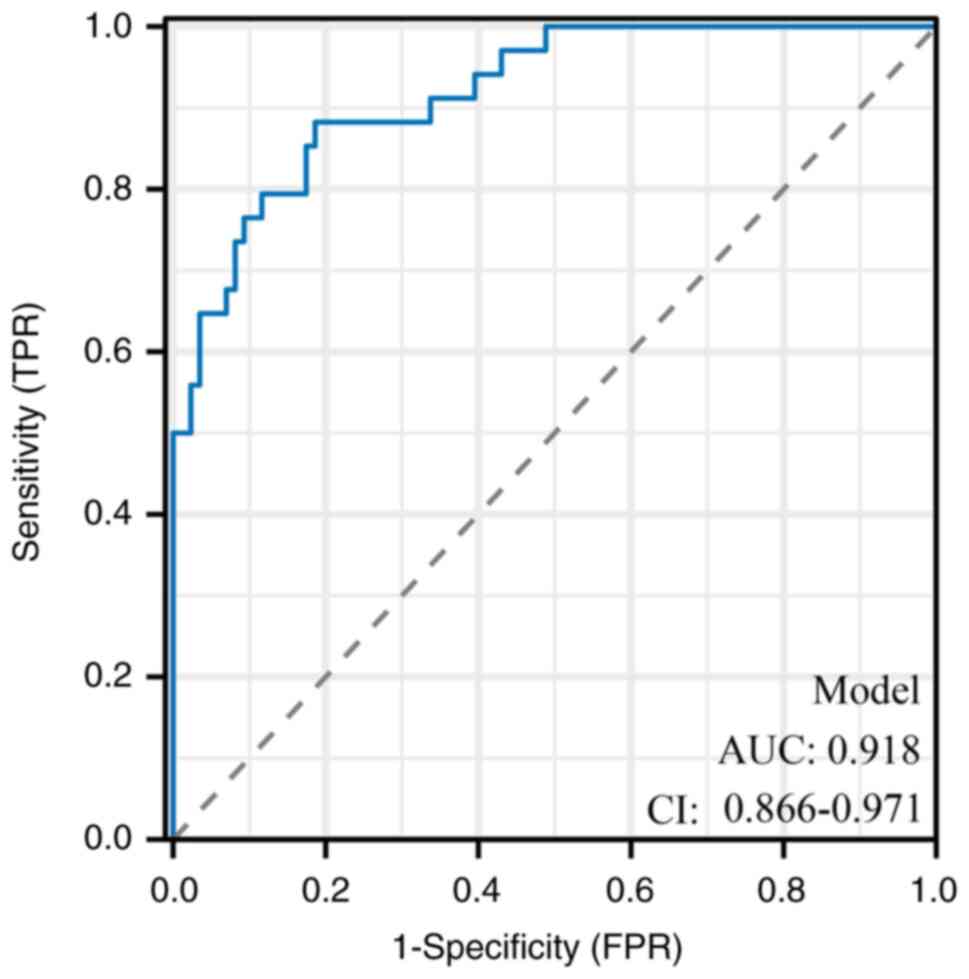

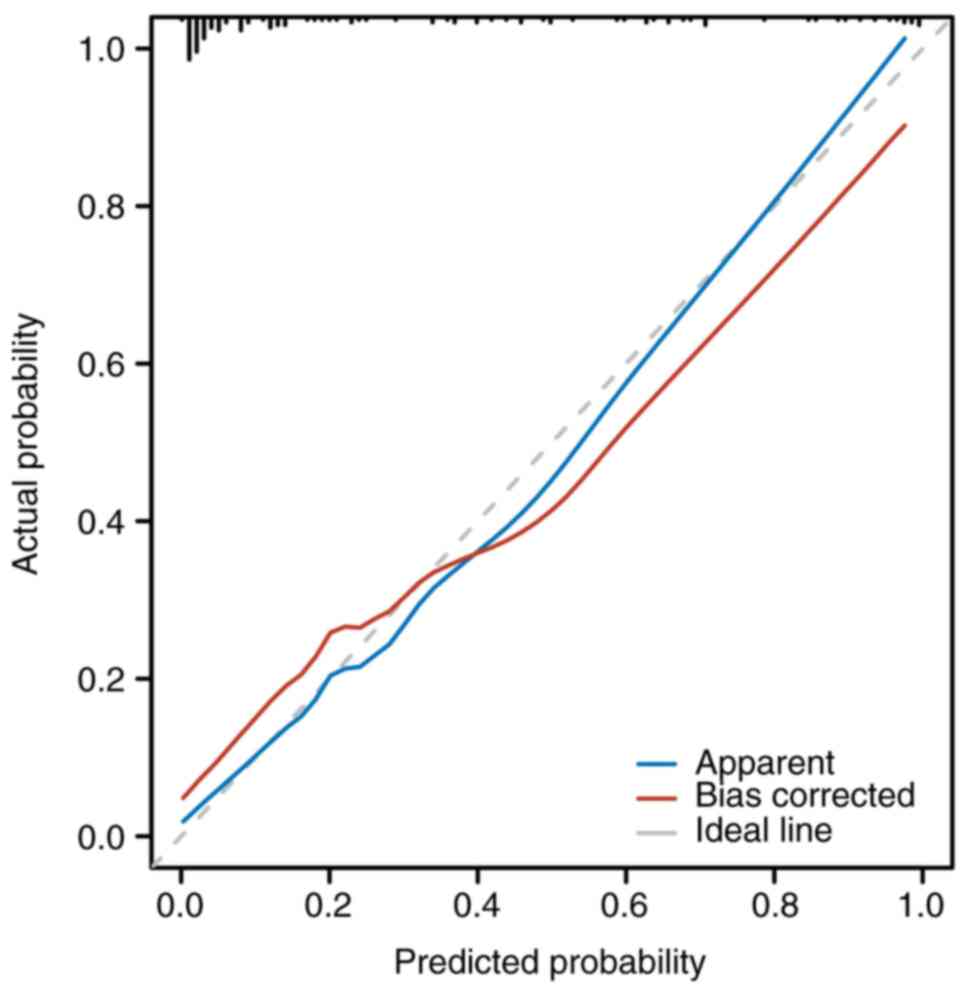

Model performance and validation

The predictive performance of the multivariate model

was evaluated through discrimination and calibration analyses. The

nomogram demonstrated excellent discrimination, with an apparent

AUC of 0.918 (95% CI, 0.866-0.971) in the derivation dataset

(Fig. 1). This result indicates

indicating only minimal optimism and confirms the robustness of the

model after adjustment for potential overfitting. The calibration

performance of the internally validated model is shown in Fig. 2, which demonstrates strong

agreement between observed and predicted probabilities. The

Hosmer-Lemeshow test yielded a non-significant result (P>0.05),

indicating a good overall model fit.

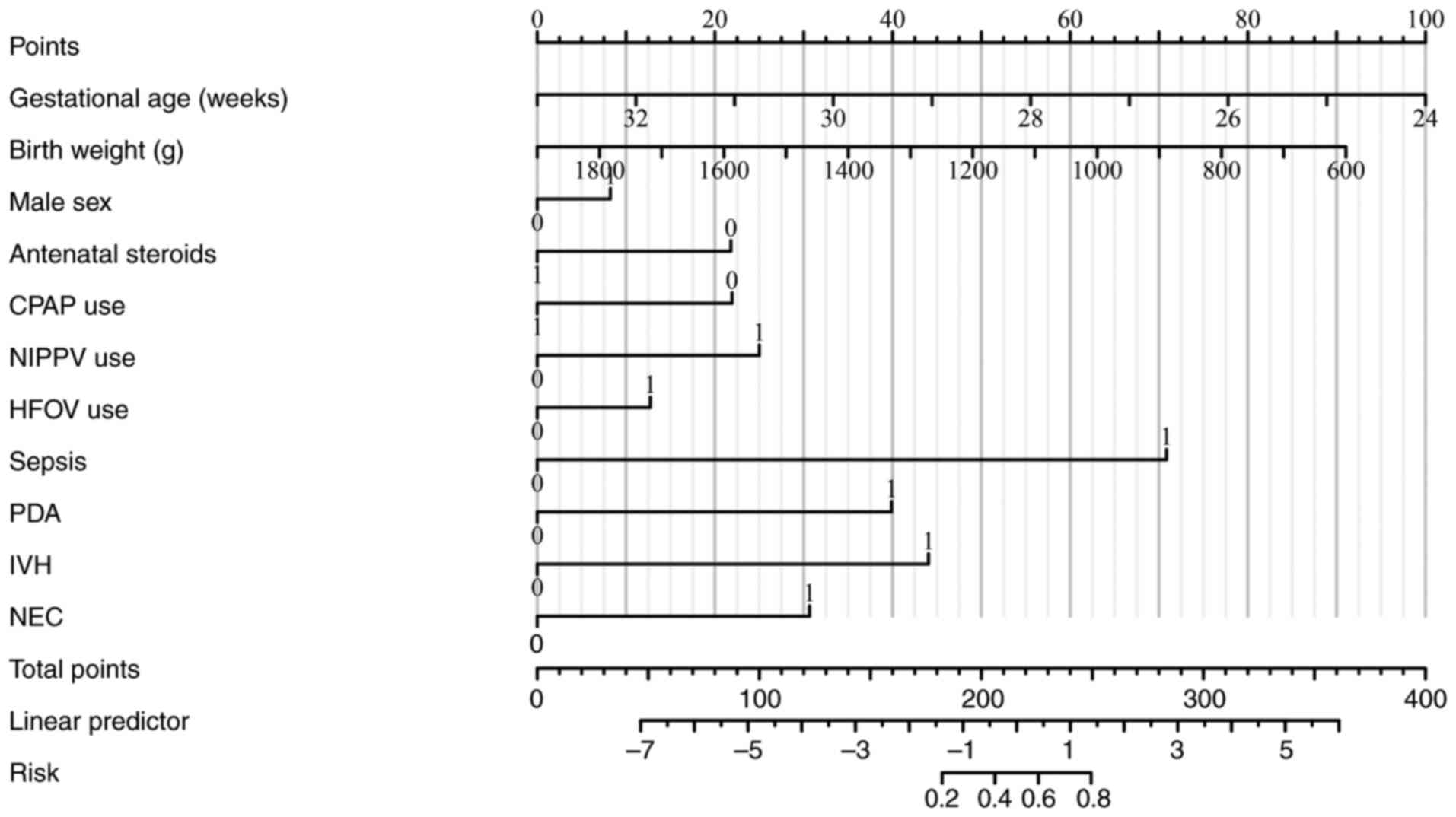

Nomogram construction

Based on the final multivariate model, a clinical

nomogram was constructed to estimate the individualized risk of BPD

in preterm infants (Fig. 3). The

predictors included in the nomogram were gestational age, birth

weight, sex, antenatal steroid use, respiratory support modalities

(CPAP, NIPPV and HFOV), and comorbidities (sepsis, PDA, IVH and

NEC). Although certain predictors did not reach statistical

significance in the multivariate model, they were retained in the

nomogram because of their established clinical relevance and

routine use in neonatal risk assessment, consistent with accepted

nomogram-building practices. Each factor contributed a weighted

score to the total, which corresponded to the predicted probability

of BPD. This nomogram offered a practical and interpretable tool

for bedside application in neonatal intensive care settings.

| Figure 3Nomogram for BPD risk prediction. The

nomogram visualizes the contribution of multiple predictors to the

risk of BPD. Predictors include gestational age, birth weight, sex,

antenatal steroids, respiratory support modes, sepsis, PDA, IVH and

NEC. The total points correspond to the predicted probability of

BPD. BPD, bronchopulmonary dysplasia CPAP, continuous positive

airway pressure; NIPPV; non-invasive positive pressure ventilation;

HFOV, high-frequency oscillatory ventilation; PDA, patent ductus

arteriosus; IVH, intraventricular hemorrhage; NEC, necrotizing

enterocolitis. |

Discussion

The present study provides a comprehensive analysis

of risk factors for BPD and presents a validated predictive model

for early identification of at-risk preterm infants. The present

model demonstrated high discriminatory power, with an area under

the ROC curve of 0.918, and robust calibration, highlighting its

potential clinical utility.

Here, gestational age and birth weight emerged as

critical predictors of BPD, which is consistent with prior research

highlighting the heightened vulnerability of extremely preterm

infants and those with impaired early growth (19-21).

Lower gestational age (OR=0.625; P=0.021) reflects the immaturity

of the lung parenchyma, surfactant deficiency, and susceptibility

to barotrauma and oxygen toxicity (5). Similarly, reduced birth weight

(P=0.059 in multivariate analysis) underscores the importance of

intrauterine growth and its association with postnatal outcomes

(22). These findings reinforce

the need for strategies targeting antenatal interventions, such as

corticosteroids and optimal timing of delivery, to reduce

prematurity-related risks.

In the present study, sepsis showed the strongest

independent association with BPD in the multivariate model

(OR=12.847; P<0.001), with an effect size notably greater than

that of the other significant predictors. This increased risk

aligns with prior studies linking systemic inflammation to

disrupted alveolarization and pulmonary vascular remodeling

(23,24). Pro-inflammatory cytokines and

reactive oxygen species released during sepsis amplify lung injury,

perpetuating the cycle of inflammation and impaired repair

mechanisms (25,26). This underscores the importance of

stringent infection control measures in the NICU, including early

recognition and management of sepsis.

Notably, the OR value for sepsis in the multivariate

analysis conducted in the present study was markedly high

(OR=12.847). This magnitude likely reflects both the strong

biological plausibility of the association and the relatively

concentrated distribution of severe early-onset sepsis in the

present BPD cohort. All cases of sepsis included in the present

analysis were diagnosed within the first 14 days of life, a

critical period for lung development, during which systemic

inflammation can exert disproportionate and irreversible effects on

alveolarization and microvascular maturation (27). Early-onset sepsis in preterm

infants has been shown to trigger release of cytokines (including

IL-6, TNF-α and IL-1β), oxidative stress and endothelial

dysfunction, which collectively disrupt pulmonary angiogenesis and

promote interstitial fibrosis (23,24,26).

Furthermore, severe infection frequently necessitates prolonged

invasive ventilation and higher oxygen exposure, compounding the

risk of ventilator-induced lung injury and oxygen toxicity

(25).

Clinically, this finding underscores the imperative

for early sepsis prevention and prompt antimicrobial treatment in

the NICU, particularly during the first 2 postnatal weeks.

Stringent infection control protocols, rapid pathogen

identification and optimized empiric antibiotic strategies may

therefore represent critical interventions to mitigate BPD risk in

high-risk preterm populations.

PDA (OR=4.514; P=0.016) was a significant predictor

identified in the present study, in agreement with previous studies

suggesting that prolonged ductal patency exacerbates pulmonary

overcirculation, increasing the risk of pulmonary edema and

ventilator dependency (28,29).

The role of PDA treatment in mitigating BPD remains controversial;

however, the present findings suggest that early closure, whether

pharmacological or surgical, may reduce the burden of

ventilator-associated lung injury in high-risk infants.

IVH (OR=5.926; P=0.028) was strongly associated with

BPD, reflecting shared mechanisms of systemic inflammation,

oxidative stress and vascular fragility (30,31).

The interplay between brain and lung injury highlights the

importance of a multidisciplinary approach to managing extremely

preterm infants, focusing on neuroprotection and minimizing

invasive procedures that increase hemodynamic instability.

While CPAP and high-frequency oscillatory

ventilation (HFOV) were significant in univariate analysis, their

effects did not remain significant in multivariate models. This may

indicate that respiratory support modalities reflect underlying

disease severity, rather than acting as direct predictors of BPD.

Nonetheless, the judicious use of non-invasive ventilation and

minimizing oxygen toxicity remain cornerstones of BPD prevention

(32,33). CPAP is generally regarded as a

protective modality that reduces ventilator-associated lung injure

(34) In the present cohort, CPAP

use was lower among infants who ultimately developed BPD, whereas

escalation to HFOV was more frequent. This pattern most likely

reflects baseline illness severity rather than a detrimental effect

of CPAP: Infants with more severe initial respiratory compromise

were less able to tolerate CPAP and required earlier escalation to

invasive ventilation or HFOV. Thus, the observed group difference

in respiratory support should be interpreted as a marker of

underlying disease severity, consistent with prior reports showing

that the choice of respiratory support modality typically reflects

the infant's clinical acuity rather than functioning as an

independent predictor of BPD (35,36).

NEC, a systemic inflammatory condition, was

significant in the present univariate analysis, but lost

significance in multivariate modeling. This result may reflect

collinearity with sepsis and other variables. Nevertheless, the

present findings align with previous research highlighting NEC as a

driver of systemic inflammation and impaired lung development

(15). Preventative measures, such

as human milk feeding and probiotics, could have dual benefits for

gut and lung health in preterm infants (37).

The nomogram constructed in the present study

provides a user-friendly tool for bedside application. While some

predictors in the final model, such as sepsis or HFOV use, were

formally coded as occurring within the first 14 days, in the

majority of cases, these events were clinically apparent or could

be anticipated within the first 72 h after birth. For example,

early-onset sepsis in preterm infants often manifests within the

first 48 h, and the need for HFOV is typically determined during

initial respiratory stabilization (38). As such, the model maintains its

intended role for early risk stratification and timely intervention

in clinical practice. By integrating gestational age, birth weight,

sepsis, PDA and IVH, the model facilitates individualized risk

stratification and enables timely interventions. Compared with

earlier models that primarily relied on gestational age and birth

weight (39,40), the present approach incorporates

comorbidities, thus enhancing predictive accuracy. Importantly, the

present study introduces several novel aspects: Unlike prior models

that typically focused on gestational age and birth weight alone,

the present nomogram integrates comorbidities such as sepsis, PDA

and IVH, variables with high clinical relevance yet often excluded

from earlier predictive tools. The development of a visually

intuitive nomogram enhances practical usability, making the model

more accessible for bedside application by clinicians. Moreover, to

the best of our knowledge, this is one of the few studies conducted

in Southwest China that has systematically developed and internally

validated a BPD risk prediction model, thereby addressing a

regional gap in neonatal research and contributing valuable

insights to the global literature. Although birth weight and sex

were not statistically significant in the present multivariate

model, they were retained in the nomogram due to their strong

clinical relevance and prior validation as BPD risk factors

(41). Including such variables

ensures clinical interpretability and aligns with accepted

practices in predictive model development (42).

The present model's high AUC (0.918) surpasses

benchmarks reported in similar studies (11), underscoring its robustness.

Moreover, the calibration curve in the present study demonstrated

excellent agreement between predicted and observed probabilities,

thus ensuring reliability across various clinical settings. These

strengths make the model particularly valuable for guiding early

interventions, such as caffeine therapy, optimization of

ventilation strategies and nutritional support (43).

The inclusion of these parameters significantly

enhances predictive accuracy while maintaining applicability within

the first 72 h of life in most cases. The comprehensive collection

of maternal, neonatal and comorbid factors allowed for a thorough

exploration of BPD risk determinants, while multivariate logistic

regression ensured the identification of independent predictors.

Furthermore, the application of bootstrapping for internal

validation enhanced the reliability of the model and reduced the

risk of overfitting. The visually intuitive nomogram bridges the

gap between complex statistical models and bedside decision-making,

facilitating rapid individualized risk estimation by

clinicians.

However, certain limitations exhibited by the

current study should be acknowledged. First, the model underwent

only internal validation using bootstrapping without any external

validation, which restricts its generalizability and positions it

as a preliminary exploratory tool; external validation in diverse

cohorts is necessary to confirm its applicability across different

clinical environments. Furthermore, the ratio of BPD events (n=34)

to the 11 candidate predictors initially entered into the

multivariate model resulted in an events-per-variable ratio of

~3.1:1, which is below the commonly recommended threshold of

10:1(44). To minimize this risk,

a stepwise backward elimination process was applied to retain only

the most stable predictors and performed bootstrap internal

validation to assess and adjust for optimism. This yielded a

bias-corrected AUC of 0.902, which was only slightly lower than the

apparent AUC, supporting the relative stability of the model.

Nevertheless, external validation in larger, multi-center cohorts

is essential to confirm the generalizability of the present

findings. The retrospective design of the present study, despite

meticulous data collection, is inherently prone to selection and

information biases. Additionally, the current study was conducted

in a single center with a relatively small sample size (n=120; BPD

cases=34), which may limit statistical power and precluded more

granular subgroup analyses by gestational age and birth weight

categories. The relatively small number of events also means that

some clinically important variables, such as birth weight and

infant sex, did not reach statistical significance in multivariable

analysis.

Future research should focus on addressing the

limitations of the present study and further advancing the field of

BPD risk prediction. Conducting multicenter, prospective studies

with larger and more diverse populations will be essential to

validate the current model externally and ensure its

generalizability. Incorporating biomarkers such as peripheral blood

cytokines (e.g., IL-6, IL-8) or molecular signatures identified

through transcriptomic approaches may enhance the precision of the

model and provide insights into the underlying mechanisms of BPD

(45). Additionally, integrating

advanced imaging techniques, such as lung ultrasound or magnetic

resonance imaging, may offer novel perspectives on disease

progression and early risk stratification. Long-term follow-up

studies are crucial to evaluate the predictive impact of the model

on neurodevelopmental and respiratory outcomes, ensuring that early

identification translates into improved quality of life for preterm

infants. Finally, assessing the real-world clinical utility of the

model, including its integration into electronic health records and

decision-support systems, will determine its potential to optimize

neonatal care and resource allocation.

Since only internal validation was performed, the

present study should be regarded as a preliminary exploratory

effort requiring future external validation to confirm its broader

applicability. In the current study, a clinically meaningful

preliminary risk prediction model for BPD in preterm infants was

constructed. The inclusion criteria were intentionally broad

(gestational age <32 weeks and birth weight ≤2,500 g) to ensure

the applicability of the model to a wider range of preterm infants

in routine clinical practice. Although this approach may include

infants at relatively lower risk for BPD, it enhances the

generalizability and relevance of the model in diverse neonatal

care settings. While the model demonstrates strong discrimination

and calibration, the relatively small sample size (n=120) and

single-center design aspect of the current study may limit the

generalizability of the present findings. Nevertheless, the use of

readily accessible clinical predictors and the application of 1,000

bootstrap resamples for internal validation provide a reliable

foundation for further model development. This exploratory analysis

offers an important first step toward establishing a practical risk

stratification tool. Although internal validation using 1,000

bootstrap resamples indicates strong model stability and reduces

overfitting risk, the absence of external validation remains a key

limitation of the present study. Without testing it on an

independent cohort, the generalizability of the model across

different populations and clinical practices cannot be fully

ensured. Future research should therefore prioritize external

validation through large-scale, multicenter, prospective studies to

confirm the performance of the nomogram in broader settings.

Establishing external credibility through future validation is

essential for integrating this model into routine clinical practice

and reinforcing its predictive value.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

YSP conceived and designed the study, and

participated in data collection, statistical analysis and

manuscript drafting. LX participated in data acquisition,

interpretation of results and critical revision of the manuscript.

WBD was responsible for data management, literature review and

assisting in statistical analysis. JWD conceived and designed the

study and critically revised the manuscript. All authors have read

and approved the final manuscript. YSP and LX confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was conducted in accordance with

The Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional

Review Board of The Affiliated Hospital, Southwest Medical

University (approval no. KY2025055). Due to the retrospective

nature of the present study, the requirement for informed consent

was waived by the ethics committee. All patient data were fully

anonymized and utilized exclusively for research purposes.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Siffel C, Kistler KD, Lewis JFM and Sarda

SP: Global incidence of bronchopulmonary dysplasia among extremely

preterm infants: A systematic literature review. J Matern Fetal

Neonatal Med. 34:1721–1731. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Perveen S, Chen CM, Sobajima H, Zhou X and

Chen JY: Editorial: Bronchopulmonary dysplasia: Latest advances.

Front Pediatr. 11(1303761)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Algarni SS, Ali K, Alsaif S, Aljuaid N,

Alzahrani R, Albassam M, Alanazi R, Alqueflie D, Almutairi M,

Alfrijan H, et al: Changes in the patterns of respiratory support

and incidence of bronchopulmonary dysplasia; a single center

experience. BMC Pediatr. 23(357)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Moreira A, Noronha M, Joy J, Bierwirth N,

Tarriela A, Naqvi A, Zoretic S, Jones M, Marotta A, Valadie T, et

al: Rates of bronchopulmonary dysplasia in very low birth weight

neonates: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Respir Res.

25(219)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Dankhara N, Holla I, Ramarao S and

Kalikkot Thekkeveedu R: Bronchopulmonary dysplasia: Pathogenesis

and pathophysiology. J Clin Med. 12(4207)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Sikdar O, Harris C and Greenough A:

Improving early diagnosis of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Expert Rev

Respir Med. 18:283–294. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Abdelrazek AA, Kamel SM, Elbakry AAE and

Elmazzahy EA: Lung ultrasound in early prediction of

bronchopulmonary dysplasia in pre-term babies. J Ultrasound.

27:653–662. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Pérez-Tarazona S, Marset G, Part M, López

C and Pérez-Lara L: Definitions of bronchopulmonary dysplasia:

Which one should we use? J Pediatr. 251:67–73.e2. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Higgins RD, Jobe AH, Koso-Thomas M,

Bancalari E, Viscardi RM, Hartert TV, Ryan RM, Kallapur SG,

Steinhorn RH, Konduri GG, et al: Bronchopulmonary dysplasia:

Executive summary of a workshop. J Pediatr. 197:300–308.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Sucasas Alonso A, Pértega Diaz S, Sáez

Soto R and Avila-Alvarez A: Epidemiology and risk factors for

bronchopulmonary dysplasia in preterm infants born at or less than

32 weeks of gestation. An Pediatr (Engl Ed). 96:242–251.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

He W, Zhang L, Feng R, Fang WH, Cao Y, Sun

SQ, Shi P, Zhou JG, Tang LF, Zhang XB and Qi YY: Risk factors and

machine learning prediction models for bronchopulmonary dysplasia

severity in the Chinese population. World J Pediatr. 19:568–576.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Zhang H, Fang J, Su Q, et al: Development

and validation of a nomogram for predicting bronchopulmonary

dysplasia in very-low-birth-weight infants. Front Pediatr.

9(648828)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Sun X, Li L, He L, Wang S, Pan Z and Li D:

Preoperative malnutrition predicts poor early immune recovery

following gynecologic cancer surgery: A retrospective cohort study

and risk nomogram development. Front Immunol.

16(1681762)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Papile LA: The Apgar score in the 21st

century. N Engl J Med. 344:519–520. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Hu X, Liang H, Li F, Zhang R, Zhu Y, Zhu X

and Xu Y: Necrotizing enterocolitis: Current understanding of the

prevention and management. Pediatr Surg Int. 40(32)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Robin X, Turck N, Hainard A, Tiberti N,

Lisacek F, Sanchez JC and Müller M: pROC: An open-source package

for R and S+ to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC Bioinformatics.

12(77)2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Zhang Z and Kattan MW: Drawing nomograms

with R: Applications to categorical outcome and survival data. Ann

Transl Med. 5(211)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Basnet K, Yadav BK, Khan SA, Bhattarai CD,

Adhikari K, Bajgain A, Karki M and Yadav R: Birth weight status of

newborns and its relationship with other anthropometric parameters.

Medicine (Baltimore). 104(e45374)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Maytasari GM, Haksari EL and

Prawirohartono EP: Predictors of bronchopulmonary dysplasia in

infants with birth weight less than 1500 g. Glob Pediatr Health.

10(2333794X231152199)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Wang L, Lin XZ, Shen W, Wu F, Mao J, Liu

L, Chang YM, Zhang R, Ye XZ, Qiu YP, et al: Risk factors of

extrauterine growth restriction in very preterm infants with

bronchopulmonary dysplasia: A multi-center study in China. BMC

Pediatr. 22(363)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Yoneda K, Seki T, Kawazoe Y, Ohe K and

Takahashi N: Neonatal Research Network of Japan. Immediate

postnatal prediction of death or bronchopulmonary dysplasia among

very preterm and very low birth weight infants based on gradient

boosting decision trees algorithm: A nationwide database study in

Japan. PLoS One. 19(e0300817)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Li L, Guo J, Wang Y, Yuan Y, Feng X, Gu X,

Jiang S, Chen C, Cao Y, Sun J, et al: Association of neonatal

outcome with birth weight for gestational age in Chinese very

preterm infants: A retrospective cohort study. Ital J Pediatr.

50(203)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Qiao X, Yin J, Zheng Z, Li L and Feng X:

Endothelial cell dynamics in sepsis-induced acute lung injury and

acute respiratory distress syndrome: Pathogenesis and therapeutic

implications. Cell Commun Signal. 22(241)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Gong T, Wang QD, Loughran PA, Li YH, Scott

MJ, Billiar TR, Liu YT and Fan J: Mechanism of lactic

acidemia-promoted pulmonary endothelial cells death in sepsis: role

for CIRP-ZBP1-PANoptosis pathway. Mil Med Res.

11(71)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Deng L, Xie W, Lin M, Xiong D, Huang L,

Zhang X, Qian R, Huang X, Tang S and Liu W: Taraxerone inhibits M1

polarization and alleviates sepsis-induced acute lung injury by

activating SIRT1. Chin Med. 19(159)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Xu Y, Xin J, Sun Y, Wang X, Sun L, Zhao F,

Niu C and Liu S: Mechanisms of sepsis-induced acute lung injury and

advancements of natural small molecules in its treatment.

Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 17(472)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Mižíková I and Thébaud B: Perinatal

origins of bronchopulmonary dysplasia-deciphering normal and

impaired lung development cell by cell. Mol Cell Pediatr.

10(4)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

El-Khuffash A, Mullaly R and McNamara PJ:

Patent ductus arteriosus, bronchopulmonary dysplasia and pulmonary

hypertension-a complex conundrum with many phenotypes? Pediatr Res.

94:416–417. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Villamor E, van Westering-Kroon E,

Gonzalez-Luis GE, Bartoš F, Abman SH and Huizing MJ: Patent ductus

arteriosus and bronchopulmonary dysplasia-associated pulmonary

hypertension: A bayesian meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open.

6(e2345299)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Faro DC, Di Pino FL and Monte IP:

Inflammation, oxidative stress, and endothelial dysfunction in the

pathogenesis of vascular damage: Unraveling novel cardiovascular

risk factors in fabry disease. Int J Mol Sci.

25(8273)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Panda P, Verma HK, Lakkakula S, Merchant

N, Kadir F, Rahman S, Jeffree MS, Lakkakula BVKS and Rao PV:

Biomarkers of oxidative stress tethered to cardiovascular diseases.

Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2022(9154295)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Shahzad T, Dong Y, Behnke NK, Brandner J,

Hilgendorff A, Chao CM, Behnke J, Bellusci S and Ehrhardt H:

Anti-CCL2 therapy reduces oxygen toxicity to the immature lung.

Cell Death Discov. 10(311)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Behnke J, Dippel CM, Choi Y, Rekers L,

Schmidt A, Lauer T, Dong Y, Behnke J, Zimmer KP, Bellusci S and

Ehrhardt H: Oxygen toxicity to the immature lung-part II: The unmet

clinical need for causal therapy. Int J Mol Sci.

22(10694)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Kaltsogianni O, Dassios T and Greenough A:

Neonatal respiratory support strategies-short and long-term

respiratory outcomes. Front Pediatr. 11(1212074)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Ramaswamy VV, Devi R and Kumar G:

Non-invasive ventilation in neonates: A review of current

literature. Front Pediatr. 11(1248836)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Dou C, Yu YH, Zhuo QC, Qi JH, Huang L,

Ding YJ, Yang DJ, Li L, Li D, Wang XK, et al: Longer duration of

initial invasive mechanical ventilation is still a crucial risk

factor for moderate-to-severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia in very

preterm infants: A multicentrer prospective study. World J Pediatr.

19:577–585. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Sjödin KS, Sjödin A, Ruszczyński M,

Kristensen MB, Hernell O, Szajewska H and West CE: Targeting the

gut-lung axis by synbiotic feeding to infants in a randomized

controlled trial. BMC Biol. 21(38)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Tana M, Tirone C, Aurilia C, Lio A,

Paladini A, Fattore S, Esposito A, De Tomaso D and Vento G:

Respiratory management of the preterm infant: Supporting

evidence-based practice at the bedside. Children (Basel).

10(535)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Jassem-Bobowicz JM, Klasa-Mazurkiewicz D,

Żawrocki A, Stefańska K, Domżalska-Popadiuk I, Kwiatkowski S and

Preis K: Prediction Model for bronchopulmonary dysplasia in preterm

newborns. Children (Basel). 8(886)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Yin J, Liu L, Li H, Hou X, Chen J, Han S

and Chen X: Mechanical ventilation characteristics and their

prediction performance for the risk of moderate and severe

bronchopulmonary dysplasia in infants with gestational age <30

weeks and birth weight <1,500 g. Front Pediatr.

10(993167)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Huang LY, Lin TI, Lin CH, Yang SN, Chen

WJ, Wu CY, Liu HK, Wu PL, Suen JL, Chen JS and Yang YN:

Comprehensive analysis of risk factors for bronchopulmonary

dysplasia in preterm infants in Taiwan: A four-year study. Children

(Basel). 10(1822)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Efthimiou O, Seo M, Chalkou K, Debray T,

Egger M and Salanti G: Developing clinical prediction models: A

step-by-step guide. BMJ. 386(e078276)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Oliphant EA, Hanning SM, McKinlay CJD and

Alsweiler JM: Caffeine for apnea and prevention of

neurodevelopmental impairment in preterm infants: Systematic review

and meta-analysis. J Perinatol. 44:785–801. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Peduzzi P, Concato J, Kemper E, Holford TR

and Feinstein AR: A simulation study of the number of events per

variable in logistic regression analysis. J Clin Epidemiol.

49:1373–1379. 1996.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Luo L, Luo F, Wu C, Zhang H, Jiang Q, He

S, Li W, Zhang W, Cheng Y, Yang P, et al: Identification of

potential biomarkers in the peripheral blood of neonates with

bronchopulmonary dysplasia using WGCNA and machine learning

algorithms. Medicine (Baltimore). 103(e37083)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|