Introduction

Hematological neoplasms lead to multiple

cardiovascular complications depending on their type and mechanism.

In patients with myeloproliferative malignancies, the outcome is

influenced not only by the disease itself, but also by severe

cardiovascular complications. The most frequent complications are

thrombotic events, pulmonary hypertension, accelerated

atherosclerosis leading to ischemic heart disease and heart failure

(1). Patients with

lymphoproliferative malignancies have a greater risk of

chemotherapy-associated cardiomyopathy, heart failure and

arrhythmia compared with the general population, effects that are

related either to the primary malignancy or to the specific

treatment (anthracyclines, tyrosine kinase inhibitors, Bruton's

tyrosine kinase inhibitors, stem cell transplantation and radiation

therapy) (2). Venous and arterial

thrombosis, as well as intracardiac thrombosis, are usually found

in myeloproliferative neoplasms, mainly in polycythemia vera (PV)

(3), with thrombosis being the

leading cause of morbidity and mortality globally in PV and

essential thrombocythemia (4),

while cardiac metastases are usually identified in hematological

tumors of the lymphoid line (that is lymphoproliferative neoplasms,

mainly lymphomas) (5).

Cardiac neoplasms can be either primary or

secondary, with the most common tumors identified being metastatic

(6). Among primary tumors, ~90%

are benign (including atrial myxomas and lipomas) (7). Secondary cardiac tumors are of

various histological types, with lung adenocarcinoma being the most

frequent cardiac metastasis identified in autopsy studies (14.6%),

followed by poorly differentiated lung carcinoma (12.4%), squamous

cell lung carcinoma (11.8%) and lymphomas/leukemias (10.1%)

(8).

Secondary cardiac involvement in lymphomas accounts

for ~10% of cardiac metastases (8), although the percentages vary (between

8.7 and 20%), as identified by previous autopsy studies (8,9).

Secondary cardiac lymphomas are more frequent in patients with

disseminated disease, rarely presenting as primary cardiac tumors

(10,11). Of these, the most frequent

lymphomas identified are B-cell lymphomas, with the diffuse large

B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) being

the most frequent (11,12). Burkitt lymphoma (BL), another

subtype of NHL, is a rare and aggressive B-cell lymphoma,

characterized by rapid cell proliferation (12), with a relatively low prevalence in

the general population (~0.8% of all adult B-cell lymphomas)

(5). However, their prevalence

increases markedly in patients who are HIV-positive, with BL being

the second most common type of NHL after DLBCL in this subgroup of

patients (13).

Patients living with HIV infection (PLWHIV) are at

an increased cardiovascular risk compared with the general

population. A high prevalence of traditional and specific risk

factors (chronic inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, immune

dysregulation and antiretroviral therapy) can lead to accelerated

atherosclerosis and, consequently, to ischemic heart disease

(14). The symptomatology of acute

coronary syndromes in these patients can be atypical, creating

diagnostic issues. PLWHIV can develop other cardiac conditions,

such as pericardial disease, endocarditis, dilated cardiomyopathy

and pulmonary hypertension (15,16).

The increased incidence of cardiovascular disease in this

population outlines the need for a higher degree of suspicion and

cardiovascular screening in these patients, especially concerning

the early detection and treatment of conditions such as myocardial

infarction, heart failure, hypertension or arrhythmia, all highly

prevalent in this population group (16). Additionally, lifestyle optimization

and the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in PLWHIV need

to be considered to prevent these secondary outcomes (16).

HIV infection, in addition to the aforementioned

particular risk factors and secondary cardiovascular effects,

affects the development of hematological and non-hematological

neoplasms, with >40% of HIV-positive individuals developing

acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)-associated lymphomas

(13). Even though the incidence

of malignant tumors is higher in HIV-positive individuals, some

[such as Kaposi sarcoma, a multicentric tumor caused by infection

with the oncovirus Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV)],

have a risk inversely related to the CD4+ count, while

others (such as BL), even though slightly more prevalent in the

AIDS stage of the infection, frequently appear in patients with a

normal CD4+ cell count and are not associated with

specific oncoviruses (13,17,18).

However, lymphoproliferative disorders, mainly lymphomas, are the

most common malignancies in PLWHIV, who exhibit either a high or

low T-helper cell count (17).

Hodgkin lymphomas (HLs) and NHL are the main types

of HIV-associated malignancies, with NHL being the most common and

the leading cause of HIV-associated mortality globally (13). In PLWHIV, 25-30% of NHL are BL or

Burkitt-like lymphomas (BLLs), being the second most common subtype

of NHL after DLBCL (13). BL and

BLL are also frequently identified and should be taken into

consideration in patients with a normal CD4+ cell count,

with the risk of developing BL in PLWHIV being more strongly

associated with cumulative HIV viremia (19,20),

outlining the need for a high degree of suspicion even in patients

who are not in the AIDS stage of HIV infection (13,18).

Oncoviruses, as aforementioned, also have an important role in the

development of HIV-associated lymphomas, with Epstein-Barr virus

(EBV) and KSHV being responsible for different subtypes of

lymphomas in PLWHIV (20). In

these patients, the uncontrolled proliferation of virus-infected

cells and expression of viral oncogenic proteins is induced by

HIV-triggered immunosuppression (20). While EBV latency type II

[expressing EBV nuclear antigen 1 (EBNA1) and latent membrane

proteins (LMP)-1 and -2] leads to an increased risk of development

of HL in HIV-infected individuals, other oncoviruses such as

KSHV/human herpesvirus 8 (HHV8) are linked to NHL, particularly

DLBCL or primary effusion lymphoma (PEL) (20). BLs are not linked with these and

often appear sporadically in PLWHIV, more likely secondary to

cumulative HIV viremia, as aforementioned or occasionally in

association with EBV latency type I (expressing only EBNA1, without

expressing LMP1 or LMP2) (20).

Despite being one of the most common lymphomas

diagnosed in PLWHIV, BL rarely represents a cause for intracardiac

masses, with limited cases presented in the literature and with the

disseminated form of the disease being more common than the primary

cardiac form (21-23).

While there is no clear or specific molecular mechanism identified

yet underlying cardiac metastasizing in BLs found in PLWHIV,

cardiac involvement potentially arises secondary to numerous

mechanisms. Firstly, early hematogenous spread appears secondary to

the high circulating tumor burden in BLs, caused by MYC

dysregulation, which drives rapid proliferation in tumor cells

(reflected by a markedly high Ki-67 index of >95%) and by the

loss of immune surveillance found especially in PLWHIV; and,

secondly, through transvenous extension from caval or mediastinal

disease, explaining the preference for the right atrium when it

comes to secondary cardiac masses in these patients (5,13,21,24).

The present report encompasses an illustrative case

of cardiac involvement in a patient with BL and HIV infection,

highlighting the diagnostic challenges, management and clinical

course of such cases.

Case report

The present study describes the case of a 57

year-old man, known to have immunological class B2 HIV infection

diagnosed 1.5 years prior to the current presentation, who has been

treated since diagnosis with antiretroviral therapy (ART)

consisting of a combination of doravirine, lamivudine and tenofovir

disoproxil, with a CD4+ count of 236

cells/mm3 (13.11%) (normal range, 500-1,500

cells/mm3), CD8+ count of 1,175

cells/mm3 (65.30%) (normal range, 170-1,000

cells/mm3) and a CD4+/CD8+

fraction of 0.20 (normal range, 1-3), 1 month prior to

presentation, suggestive of moderate-severe immunosuppression. The

HIV infection history of the patient was notable due to a

CD4+ count of 349 cells/mm3 and a

CD4+/CD8+ fraction of 0.20, with a HIV

viremia of 117 viruses/ml shortly after ART initiation, suggestive

of moderate immunosuppression. The patient presented in April 2025

to the emergency room of Coltea Clinical Hospital (Bucharest,

Romania) with rapidly growing (~3 months), painful, round, soft and

adherent left latero-thoracic and right latero-cervical

subcutaneous masses, measuring 12x7 cm (latero-thoracic) and 9x5 cm

(latero-cervical) in size. Clinical examination revealed

tachycardia with an irregular heart rate (HR) of 140 bpm, skin

pallor, nail clubbing, absent lung sounds in the left pulmonary

base, no crackles on pulmonary auscultation, normal blood pressure,

blood oxygen saturation of 96%, normal respiratory rate, light

exertional dyspnea and no palpitations, dizziness or other

complaints at the moment of presentation. The patient also

mentioned an unintentional weight loss of ~10% in the past 2 years

as well as night sweats.

Considering the clinical presentation and patient

history, laboratory tests were ordered, along with an

electrocardiogram (ECG) and a chest X-ray. The laboratory tests

revealed a normal white blood cell count [5,720 cells/µl

(4,000-11,000 cells/µl normal range), including 35% lymphocytes

(20-45% normal range) and 56% neutrophiles (43-65% normal range)],

mild microcytic anemia [hemoglobin, 10.3 g/dl (14-17 g/dl normal

range); mean corpuscular hemoglobin, 22.5 pg (27-33 pg normal

range); and mean corpuscular volume, 74.3 fl (80-96 fl normal

range)] with no iron deficit [decreased total iron binding capacity

of 219 µmol/dl (250-450 µmol/dl normal range) with increased iron

saturation of 40% (16-25% normal range) and increased ferritin],

mild thrombocytosis [platelet count, 454,000 cells/µl

(150,000-400,000 cells/µl normal value)], inflammatory syndrome

with an increase in all inflammatory biomarkers measured

[C-reactive protein (CRP), 9.4 mg/dl (normal value <0.3 mg/dl);

erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 86 mm/h (3-8 mm/h normal range);

fibrinogen, 596 mg/dl (150-400 mg/dl normal range); and ferritin,

870 ng/ml (24-260 ng/ml normal range)] and an elevated N-terminal

pro B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) value, suggestive of

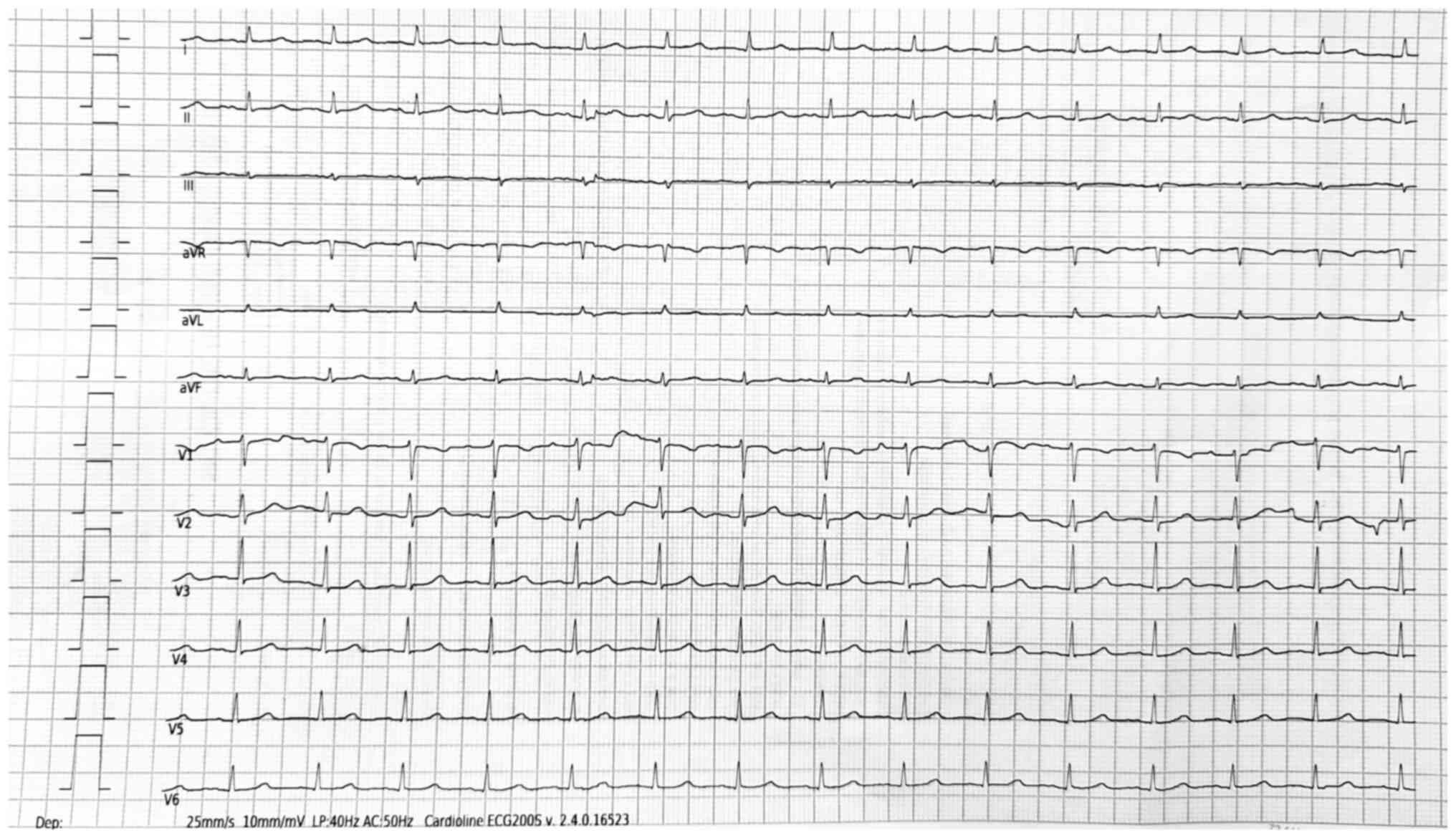

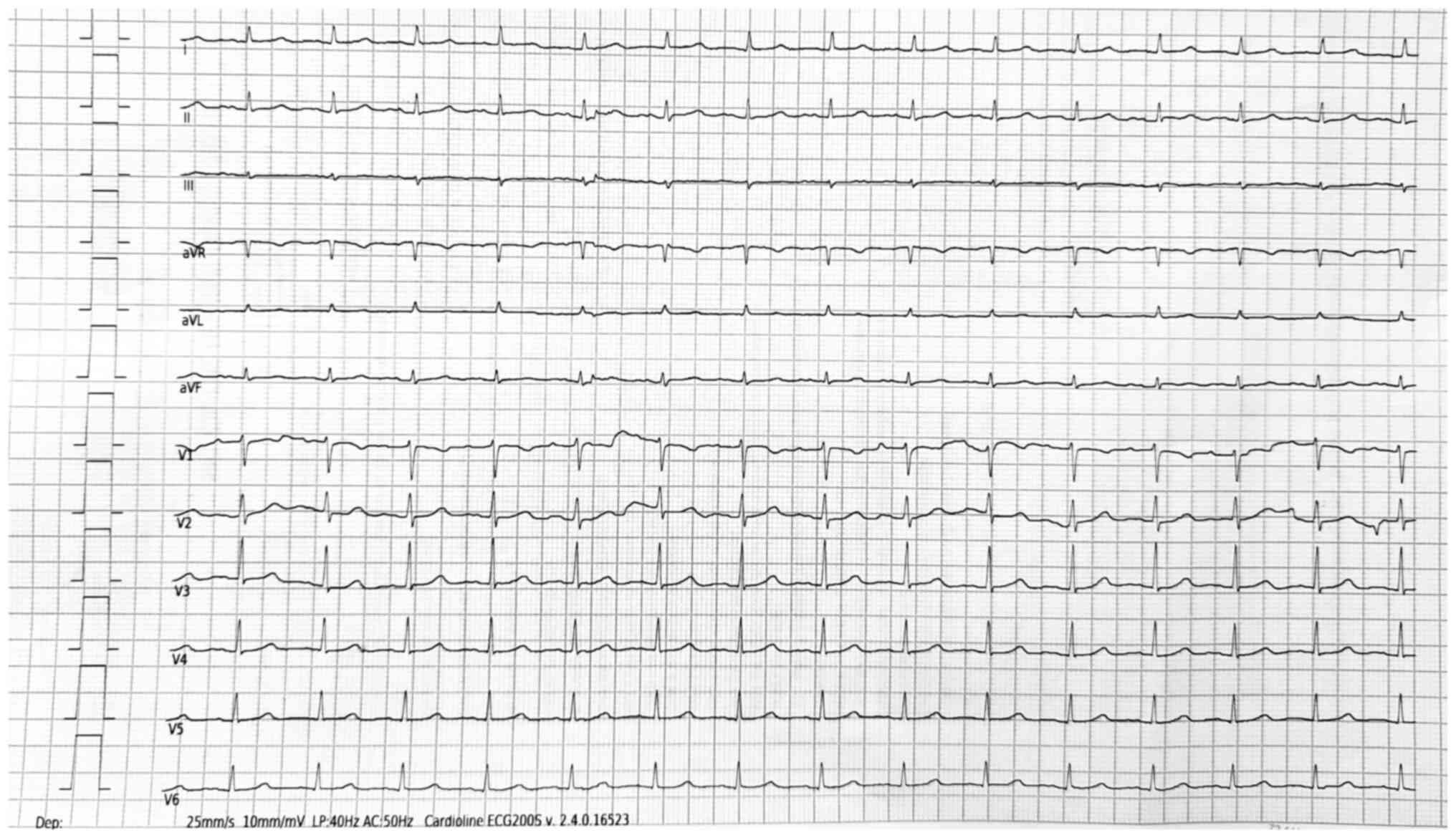

heart failure [2,260 pg/ml (0-300 pg/ml normal range)]. An ECG

revealed atrial fibrillation with a rapid ventricular response

[heart rate (HR), 140 bpm], with a QRS complex duration of <100

msec, diffuse QRS microvoltage and no notable repolarization

abnormalities nor pathological Q waves.

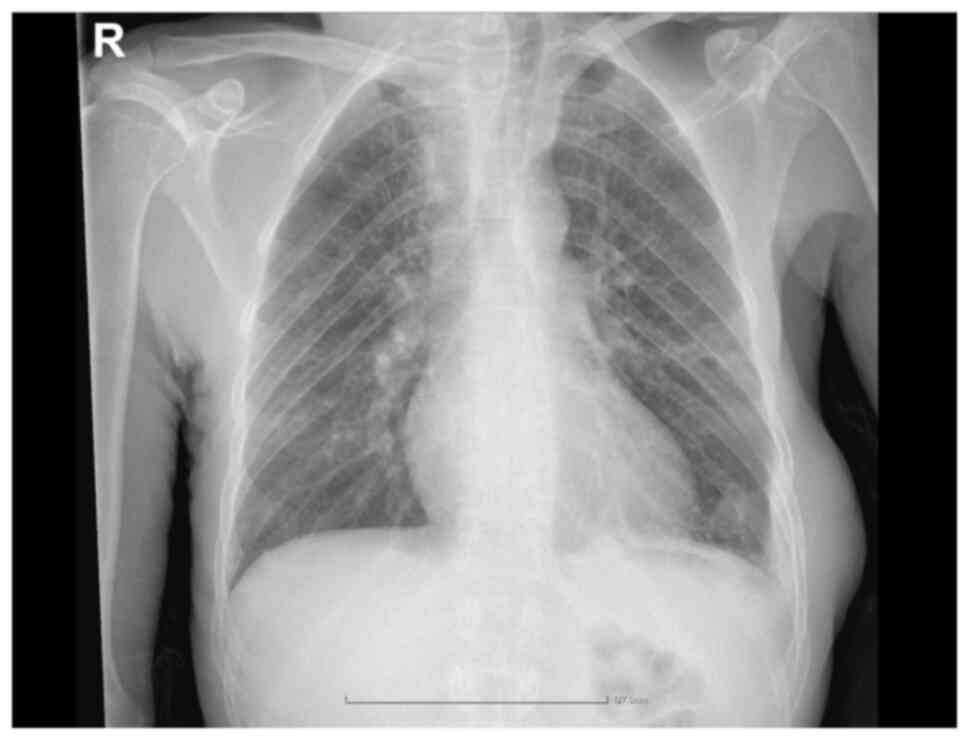

Furthermore, a chest X-ray revealed left basal

pleural effusion and right upper mediastinum enlargement with

secondary tracheal compression (Fig.

1).

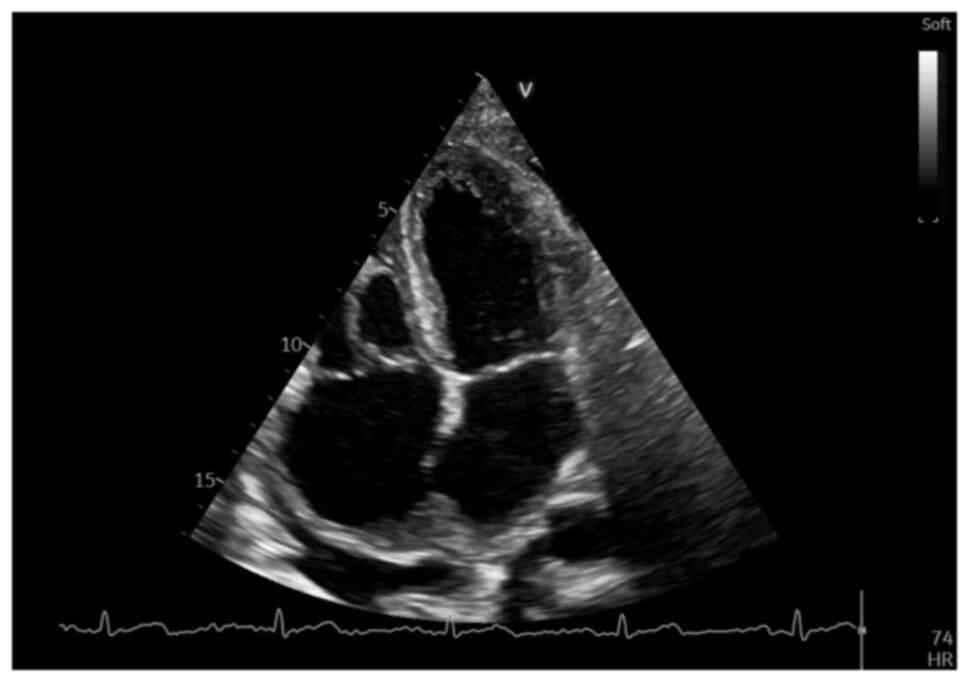

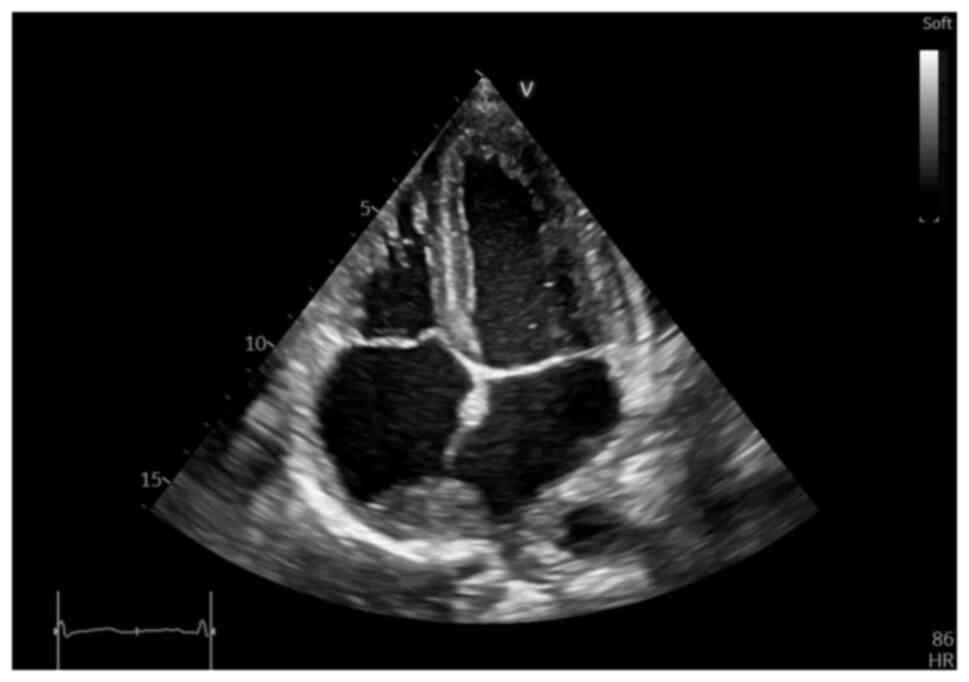

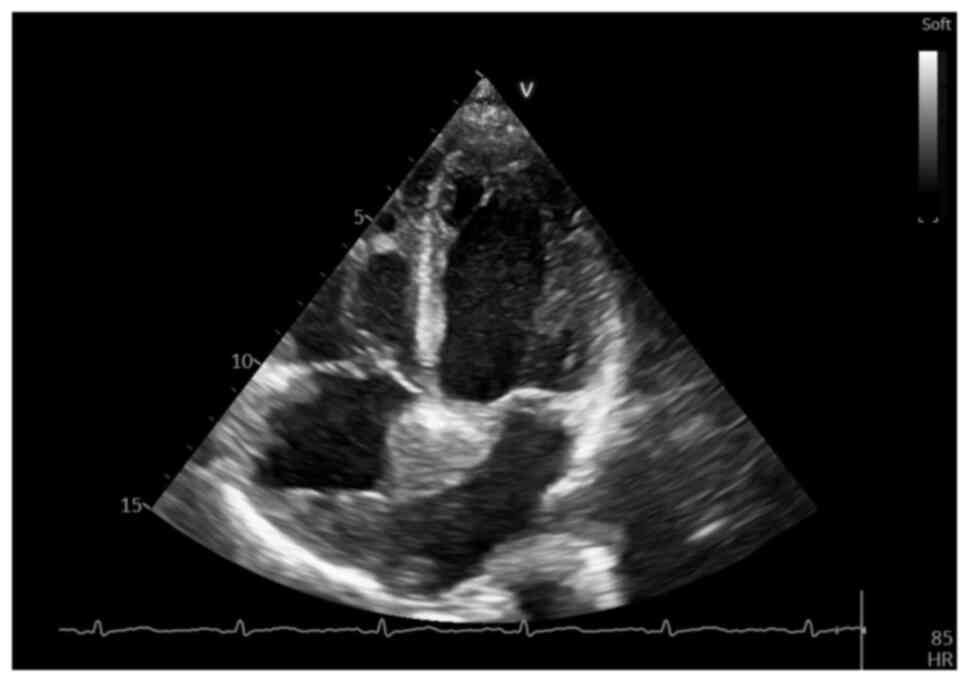

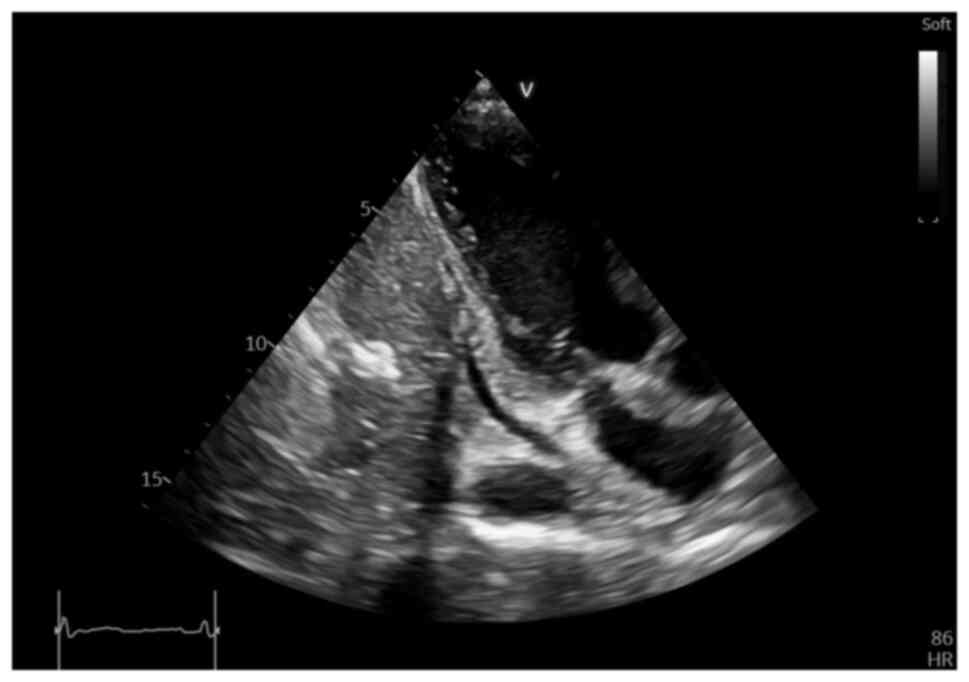

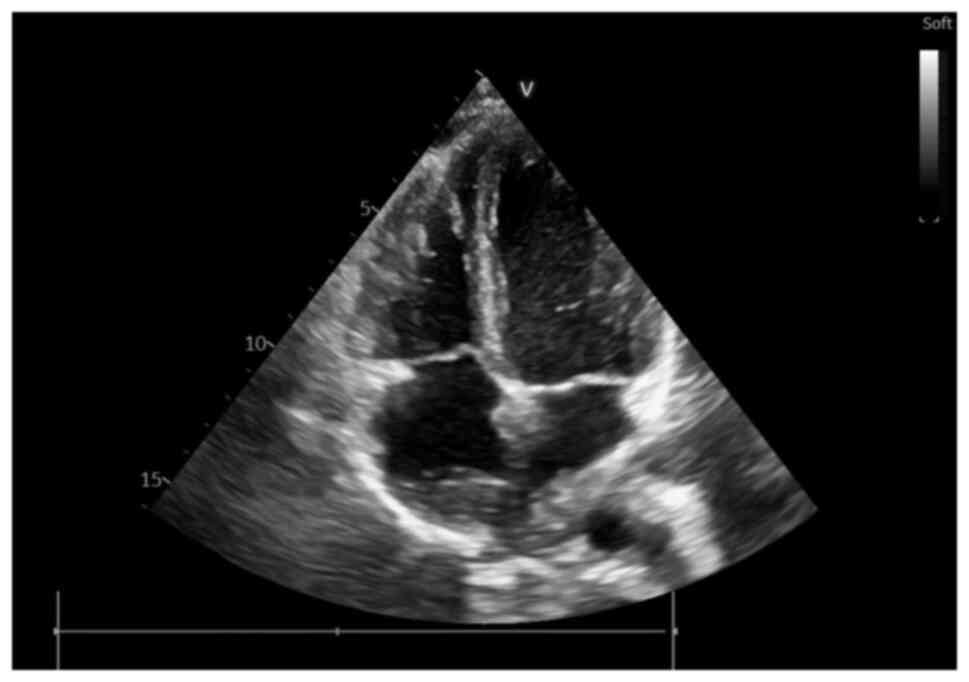

Considering these findings (newly diagnosed atrial

fibrillation, diffuse QRS microvoltage on the ECG and an increased

NT-proBNP value) echocardiography was performed, which revealed an

irregular, diffusely hyperechoic, immobile upper atrial mass, which

occupied ~1/3 of the right atrial (RA) area (4.2 cm2,

with an RA area of 16.9 cm2) and infiltrated the

interatrial septum, extending to the anterior wall and roof of the

left atrium (LA), also involving the right upper pulmonary vein

(Fig. 2, Fig. 3 and Fig. 4), a small pericardial effusion and

mild tricuspid regurgitation, with no apparent flow obstruction at

the level of the tricuspid valve.

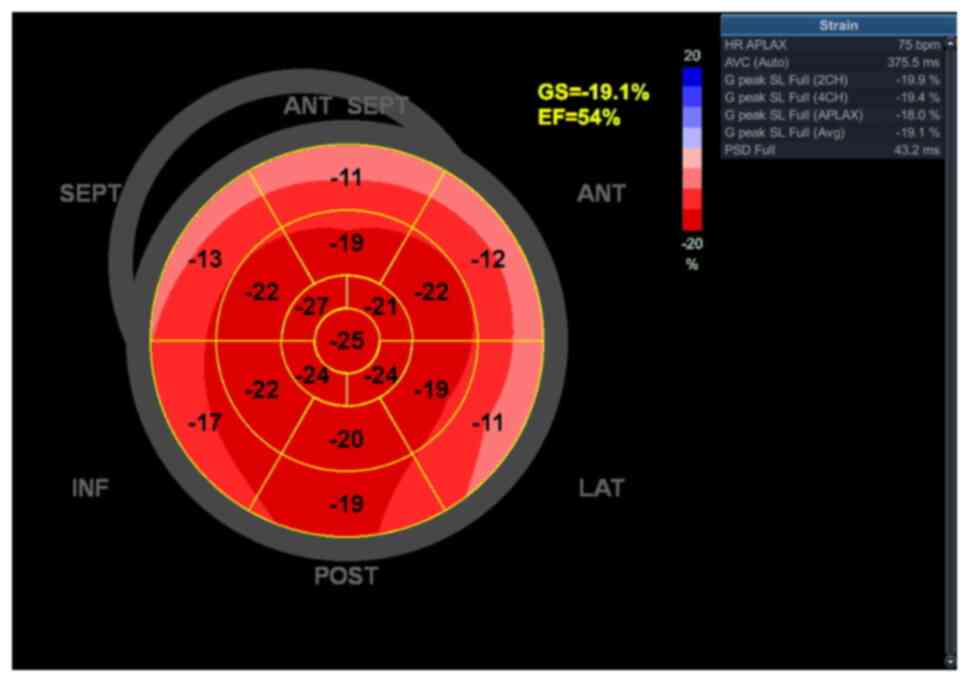

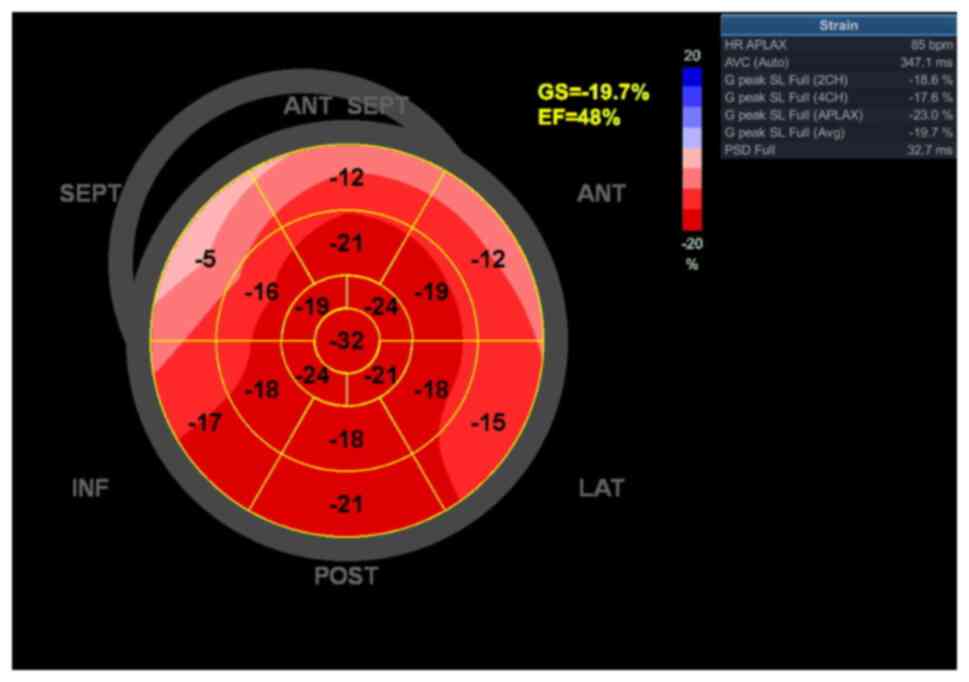

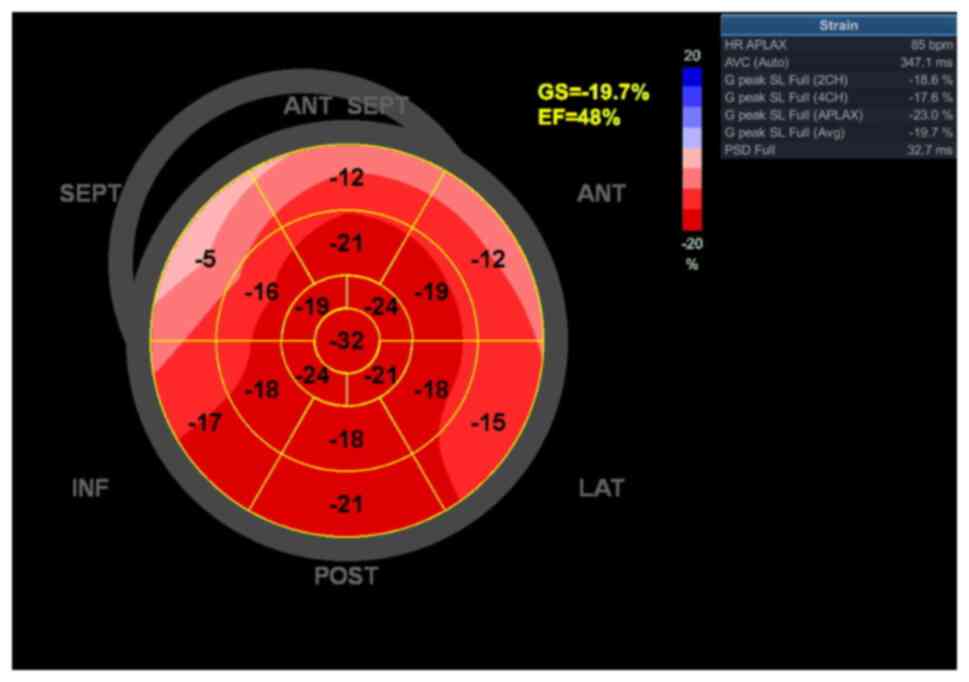

Functionally, the left ventricle demonstrated normal

filling pressures, but a left ventricular global longitudinal

strain (GLS) of -19.7% with a slightly reduced ejection fraction

(EF) of 48% (Fig. 5). The slight

reduction in GLS and EF, without any specific segmentary

distribution, suggesting an ischemic etiology, was suspected to be

due to tumoral infiltration. As a consequence, a CT scan was

ordered to further understand the tumoral infiltration extent and

distribution.

| Figure 5Echocardiography bull's-eye plot at

the initial evaluation showing a slightly reduced global strain and

ejection fraction, localized at the level of the basal segments of

the antero-lateral, antero-septal and septal walls and

interventricular septum. SEPT, septal wall; ANT, anterior; LAT,

lateral wall; POST, posterior; INF, inferior; GS, global

longitudinal strain; EF, ejection fraction; AVC, aortic valve

closure; HR, heart rate; APLAX, apical long-axis; PSD, peak strain

dispersion; G peak SL, global peak longitudinal strain. |

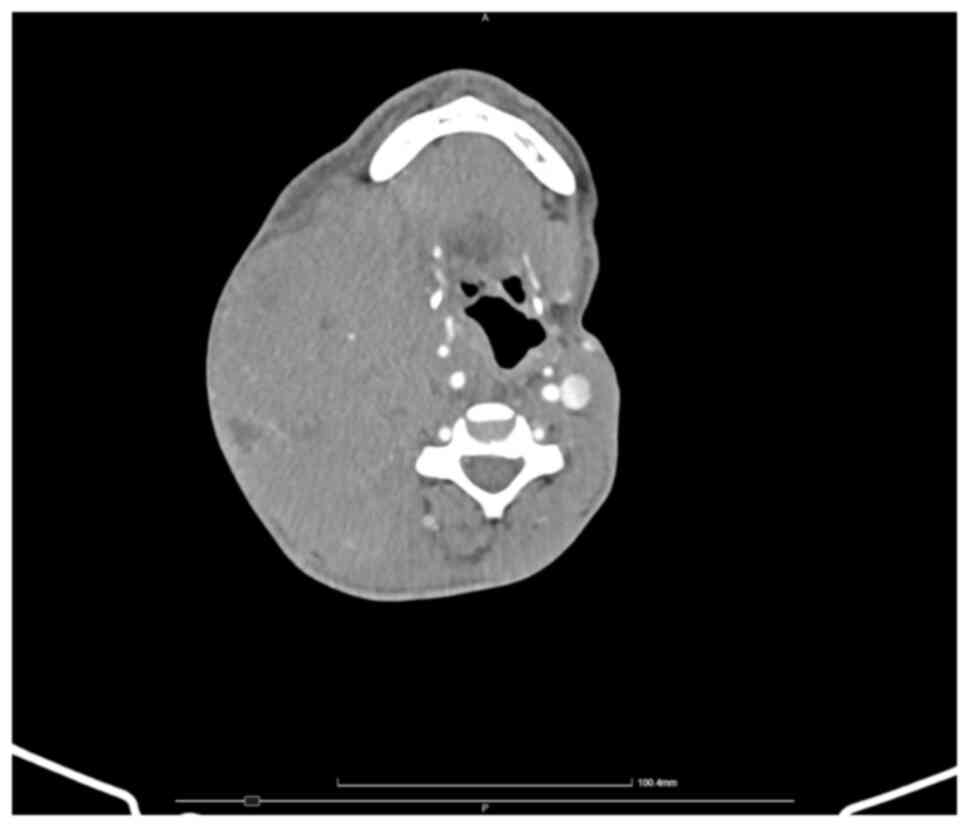

The whole-body CT showed multiple large masses,

including: i) A right lateral cervical mass of ~8.3x12x18 cm, with

a diffuse iodine uptake, necrosis areas and pharyngeal, laryngeal,

tracheal and thyroid compression, alongside compression and

stenosis of the right common, internal and external carotid

arteries and apparent extrinsic obstruction of the internal jugular

vein (Fig. 6); ii) a left

latero-thoracic mass of 8.4x4x11 cm with diffuse iodine uptake and

necrosis areas; and iii) an RA mass, which infiltrated the LA and

the right upper pulmonary vein, extending to the interatrial

septum, surrounding the aortic root and further extending to the

base of the interventricular septum and right ventricle (Figs. 7 and 8). No central nervous system (CNS)

involvement was identified, and neither any other notable findings

on the CT scan. Considering the cardiac infiltration observed on

the CT scan, which extended to the base of the left and right

ventricles, the slight reduction in EF and the reduced GLS observed

at the level of the basal segments of the antero-lateral,

antero-septal and septal walls as well as the interventricular

septum was interpreted in the context of tumoral infiltration.

Considering these findings, anticoagulant therapy

was initiated with a direct oral coagulant, due to the high

thromboembolic risk in the context of atrial fibrillation

(apixaban, 5 mg twice daily, with no interactions with ART) and a

β-blocker (metoprolol) for rate control. Additionally, a discussion

was held regarding the addition of a sodium-glucose cotransporter-2

[inhibitor to the treatment regimen (dapagliflozin or

empagliflozin, sodium-glucose cotransporters used in treating type

2 diabetes and heart failure)] according to the current guideline

recommendations and considering the presence of heart failure

(25); however, after careful

consideration of the potential benefits (a reduction in heart

failure mortality and hospitalization) and risks (increased risk of

urinary tract infections in the context of HIV co-infection with

moderate-severe immunosuppression), it was decided, in accordance

with the wishes of the patient, to temporarily withhold the

addition of dapagliflozin or empagliflozin to the treatment regimen

until an improved immune control was obtained with ART (changed

from doravirine, lamivudine and tenofovir disoproxil to

bictegravirum/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide after

hematological diagnosis and chemotherapy initiation).

An incisional biopsy of the right latero-cervical

mass was made and the fragment was sent for histopathological and

immunohistochemical analyses. The patient was closely monitored

clinically and biologically awaiting the results, with

echocardiographic evaluations repeated weekly. After 1 week from

the initial evaluation, the patient exhibited an increase in size

and discomfort in the latero-thoracic and latero-cervical regions,

with notable growth of the cardiac mass observed during

echocardiographic re-evaluation, and no other morphological or

functional changes observed compared with the initial evaluation

(Fig. 9). The conversion to sinus

rhythm was obtained spontaneously, without the need for rhythm

control therapy, and sinus rhythm was maintained throughout

subsequent evaluations, although certain changes in repolarization

were observed on subsequent ECG evaluations, as the tumoral mass

expanded in size (negative T waves in V1-V3), with no other

repolarization abnormalities or pathological Q waves and a right

bundle branch block (RBBB) QRS morphology (rsR' aspect of the QRS

segment, suggestive of incomplete RBBB), with a QRS complex <100

msec and a slightly prolonged corrected QT (QTc) interval of 458

msec (corrected with the Fridericia formula:

QTc=QT/RR1/3). Additionally, a decrease in NT-proBNP

levels shortly after spontaneous restoration of the sinus rhythm

(786 pg/ml) was observed.

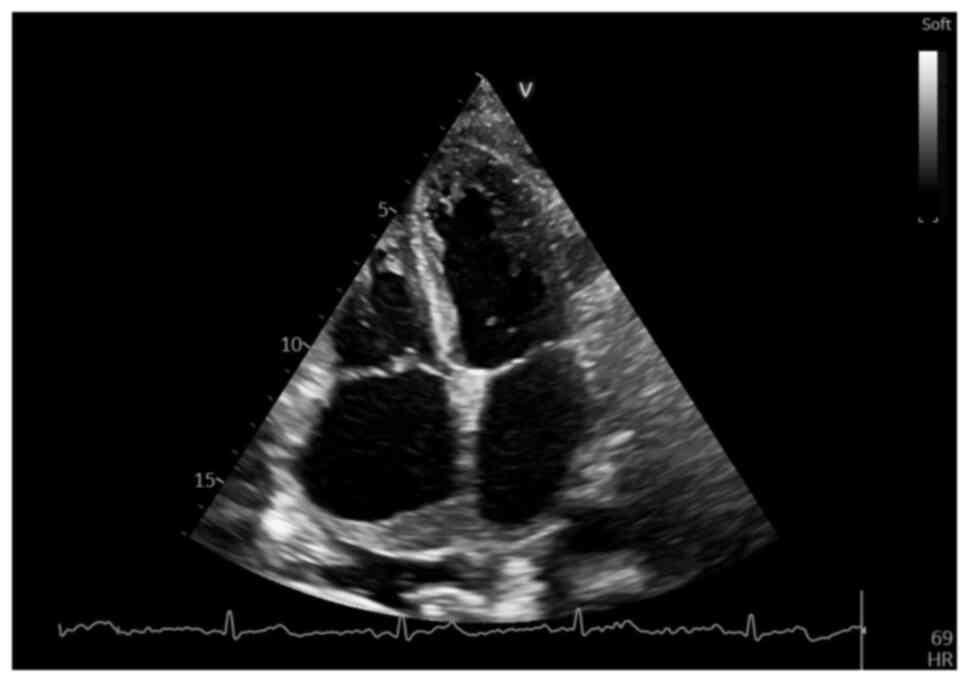

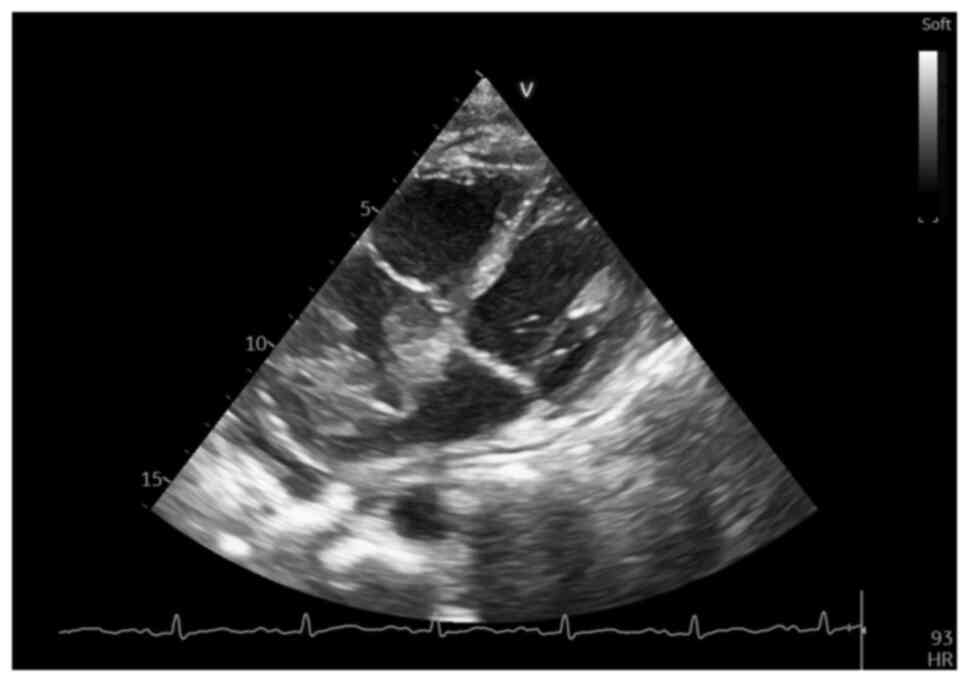

A subsequent echocardiographic follow-up evaluation

at 3 weeks after the initial one, while awaiting the tissue

immunohistochemical analysis results, revealed a marked increase in

size of the RA mass, which now occupied >1/2 of the RA area (9.4

cm2 with an RA area of 16.6 cm2),

infiltrating almost entirely the interatrial septum and more of the

anterior wall, as well as the roof of the LA and right upper

pulmonary vein (Fig. 10),

demonstrating a notably rapid increase in the size of the cardiac

tumor, but well tolerated at the time, with no apparent flow

obstruction or further changes in cardiac function. However, the

rapid growth of the latero-thoracic and latero-cervical masses made

echocardiographic assessment difficult, and the aggressive growth

of the cardiac mass highlighted the need for a quick, definitive

diagnosis and the initiation of therapy.

Tissue immunohistochemical analysis was performed,

using the following procedure: Sections with a thickness of 2.5 µm

obtained from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue

samples were cut and affixed to positively charged microscope

slides. Subsequently, these slides were subjected to a heating

process at a temperature of 60˚C for 1 h in a dry oven, thereby

enhancing the adhesion of the tissue and softening the paraffin.

The immunohistochemistry procedure was conducted as per established

protocol using a Ventana BenchMark ULTRA autostainer (Roche Tissue

Diagnostics). The sections went through steps of deparaffinisation,

rehydration and antigen retrieval with Ventana's CC1 (prediluted,

ph 8.0) solution (Roche Tissue Diagnostics). Primary antibodies

were applied according to the manufacturer's dilution guidelines

and permitted to interact with the sections. The primary antibodies

utilized in this study included the following: Anti-c-MYC (cat. no.

790-4628) Rabbit Monoclonal Primary Antibody (ready-to-use; Roche

Diagnostics GmbH), CONFIRM anti-bcl-2 (cat. no. 790-4464) Mouse

Monoclonal Primary Antibody (ready-to-use; Roche Diagnostics GmbH),

CONFIRM anti-Ki-67 (cat. no. 790-4286) Rabbit Monoclonal Primary

Antibody (ready-to-use; Roche Diagnostics GmbH), CONFIRM anti-CD20

(cat. no. 760-2531) Primary Antibody (ready-to-use; Roche

Diagnostics GmbH), CONFIRM anti-CD3 (cat. no. 790-4341) Rabbit

Monoclonal Primary Antibody (ready-to-use; Roche Diagnostics GmbH),

CD138/syndecan-1 (cat. no. 760-4248) Mouse Monoclonal Antibody

(ready-to-use; Roche Diagnostics GmbH), VENTANA anti-CD10 (cat. no.

790-4506) Rabbit Monoclonal Primary Antibody (ready-to-use; Roche

Diagnostics GmbH), bcl-6 (cat. no. 760-4241) Mouse Monoclonal

Antibody (ready-to-use; Roche Diagnostics GmbH), MUM1 (cat. no.

760-6082) Rabbit Monoclonal Primary Antibody (ready-to-use; Roche

Diagnostics GmbH), Epstein-Barr Virus (cat. no. 760-2640) Mouse

Monoclonal Antibody (ready-to-use; Roche Diagnostics GmbH), HHV-8

(cat. no. 760-4260) Mouse Monoclonal Antibody (ready-to-use; Roche

Diagnostics GmbH) and anti-CD30 (cat. no. 790-4858) Mouse

Monoclonal Primary Antibody (ready-to-use; Roche Diagnostics GmbH).

The incubation periods were established as 16 min for MYC and Ki67,

and 32 min for BCL2, BCL6, CD10, CD20, CD3, MUM1, CD138, EBV-LMP1,

HHV-8 and CD30. The visualization process was conducted using the

Ultraview universal DAB IHC detection kit (cat. no. 760-500; Roche

Diagnostics GmbH), followed by counterstaining utilizing

hematoxylin II for 8 min and a bluing solution for 8 min at room

temperature in the automated BenchMark ULTRA (cat. no. 750-600;

Roche Diagnostics GmbH). The slides were meticulously cleaned and

dehydrated through a graded series of ethanol and xylene. Finally,

the slides were affixed with mounting media onto microscope slides.

The subsequent analysis showed a CD20 diffusely positive, CD10

positive, B cell lymphoma 6 (BCL6) positive, multiple myeloma

oncogene 1 (MUM1) negative, CD30 and BCL2 negative, and c-Myc 70%

positive tissue (Fig. 11A and

B). Positivity for CD3 was

observed in frequent small intratumoral T cells, while CD138 was

positive in rare intratumoral plasmacytes and negative in tumoral

cells. The tissue was negative for EBV-LMP1 and HHV8 (thus

excluding other oncovirus-driven hematological malignancies

identified in PLWHIV, such as DLBCL, PEL or HL and supporting a

diagnosis of BL), with a very high proliferation index Ki-67 of

~98%, helping differentiate BL from DLBCL, which has a lower index

of proliferation (Fig. 11C)

(26).

The identified malignant cells also possessed strong

basophilia and multiple prominent basophilic nucleoli and multiple

mitoses observed under standard histological analysis, performed

according to the following procedure by the Pathology Department:

H&E staining was performed on 2.5-µm FFPE sections. Tissue was

fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin, processed through graded

ethanol and xylene and embedded in paraffin. Sections mounted on

charged slides were dewaxed in xylene, rehydrated through

descending alcohol concentrations and stained with hematoxylin

(0.1% solution) for 5 min, followed by bluing in water, and

counterstaining with eosin (0.5% solution) for 2 min, at room

temperature. Slides were then dehydrated in 70, 95 and 100%

ethanol, cleared in xylene and coverslipped. Histological

evaluation was performed using a standard light microscope at x20

and x40 magnification (Fig. 11D).

Thus, considering the presence of frequent basophilic monomorphic

cells with prominent basophilic nucleoli on histological analysis,

along with the diffusely positive CD20, positive BCL6 (Fig. S1A), intensely positive CD10

(Fig. S1B), negative MUM1

(Fig. S1C) and negative BCL2

(Fig. S1D), with a positive c-Myc

of 70% and the high index of proliferation, close to 100% (Ki67 of

98%), a diagnosis of non-Hodgkin BL as BL international prognostic

index 2(27), high-risk secondary

to HIV immunosuppression, was made (26). Chemotherapy with a

hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine,

methotrexate, cytarabine and dexamethasone (hyper CVAD) regimen was

initiated considering the markedly high hematological risk of the

patient according to the BL international prognostic index (namely,

>40 years old, with a high index of tumoral progression and

lactate dehydrogenase >3-fold the upper limit of the normal

range, with a value of 879 U/l). The regimen included the following

agents and dosing, and was administered according to the following

protocol: On cycles 1, 3, 5 and 7 (3-4 weeks between cycles), 600

mg/m2 cyclophosphamide was administered intravenously

(IV) over 2 h every 12 h for six doses starting on day 1. Mesna

(600 mg/m2/day) was administred by continuous IV

infusion on days 1-3, starting 1 h before, plus 2 mg vincristine IV

on days 4 and 11, plus 50 mg/m2 doxorubicin IV on day 4

and 40 mg dexamethasone orally on days 1-4 and 11-14. On cycles 2,

4, 6 and 8 (3-4 weeks between cycles), 200 mg/m methotrexate was

administered IV over 2 h followed by 800 mg/m2 IV over

22 h on day 1, plus 3 g/m2 cytarabine IV over 2 h every

12 h for four doses starting on day 2, plus 15 mg leucovorin IV

every 6 h for eight doses beginning 12 h after the completion of

methotrexate infusion, and increased to 50 mg IV every 6 h if

methotrexate levels were >20 µM/l at baseline, were >1.0 µM/l

at 24 h or were >0.1 µM/l at 48 h after the end of methotrexate

infusion, until levels were <0.1 µM/l. Methylprednisolone (50

mg) was administered IV every 12 h on days 1-3.

However, considering the markedly high

cardiovascular risk according to the score developed by the Heart

Failure Association in collaboration with the International

Cardio-Oncology Society (HFA-ICOS) (25), namely, elevated baseline NT-proBNP,

history of heart failure and a selected treatment plan with

anthracyclines, the patient was closely monitored with repeated

echocardiographic evaluations during chemotherapy initiation. The

patient responded well to the regimen, with a notable reduction in

all tumoral masses after chemotherapy initiation. In an

echocardiographic evaluation made 5 days after chemotherapy

initiation, the cardiac mass occupied <1/5 of the RA area (2.7

cm2 with an RA area of 20.6 cm2, right atrial

dilation compared with the initial measurement and a marked tumor

area reduction compared with the first and second evaluation),

measured ~2.3x1.2 cm and was restricted to the roof of the RA and

upper third of the interatrial septum, with minimal involvement of

the LA roof and right upper pulmonary vein compared with

pretherapeutic evaluation and no extension to the base of the right

or left ventricles (Figs. 12 and

13).

After 2 weeks post-therapy initiation, a notable

reduction in size of the latero-cervical and latero-thoracic

tumoral masses was observed and the compression of the carotid

arteries and the jugular vein subsequently remitted. The patient

also demonstrated a notable improvement in symptoms, with remission

of the pain that was present during initial and subsequent

evaluations. The laboratory results exhibited a marked reduction in

inflammatory syndrome biomarkers (CRP, 1.6 mg/dl and fibrinogen,

521 mg/dl) and a decrease in the platelet count (218,000 cells/µl),

with the persistence of microcytic anemia (hemoglobin, 9 g/dl) and

a reduction in white blood cell count (2,590 cells/µl, including

45% lymphocytes and 40.7% neutrophiles). The patient maintained the

sinus rhythm and no other cardiovascular complications associated

with treatment were observed during monitoring. The ECG showed a

notable improvement compared with previous evaluations (namely,

sinus rhythm with an HR of 90 bpm and no QRS morphology changes,

indicative of remission of RBBB morphology) and the remission of

the negative T waves in V2-V3, which became positive, with no other

repolarization abnormalities and correction of the slightly

prolonged QTc interval (now 435 msec with the Fridericia formula).

However, a diffuse QRS microvoltage was still observed (Fig. 14).

| Figure 14Post-chemotherapy electrocardiogram

showing sinus rhythm, a heart rate of 90 bpm, remission of the

right bundle branch block morphology, remission of the negative T

waves in V2-V3, diffuse QRS microvoltage (showing in this case loss

of electrical signal caused probably by tumoral infiltration)and

normalization of the corrected QT interval (435 msec, Fridericia

formula). V1-V6 refer to precordial leads. aVR, augmented vector

right; aVL, augmented vector left; aVF, augmented vector foot; LP,

low pass; AC, alternating current. |

There were no further changes in cardiac function or

morphology observed in subsequent echocardiographic evaluations

until discharge, which occurred 2 weeks after the initiation of the

first cycle of the hyper CVAD protocol. The patient continued to be

monitored after chemotherapy initiation for cardiovascular or

systemic side effects through regular clinical evaluations every 2

weeks, laboratory tests, ECG monitoring and echocardiographic

screenings. Furthermore, recommendations for the prevention of

cardiovascular disease, including lifestyle changes, as well as the

benefits and risks of the cardiovascular treatment prescribed, were

offered, in addition to information regarding possible adverse

cardiovascular effects of the chemotherapy regimen and the early

identification of warning signs and symptoms requiring further

evaluation (including sudden onset dyspnea or dyspnea aggravation,

palpitations, dizziness, chest pain or lower extremity edema).

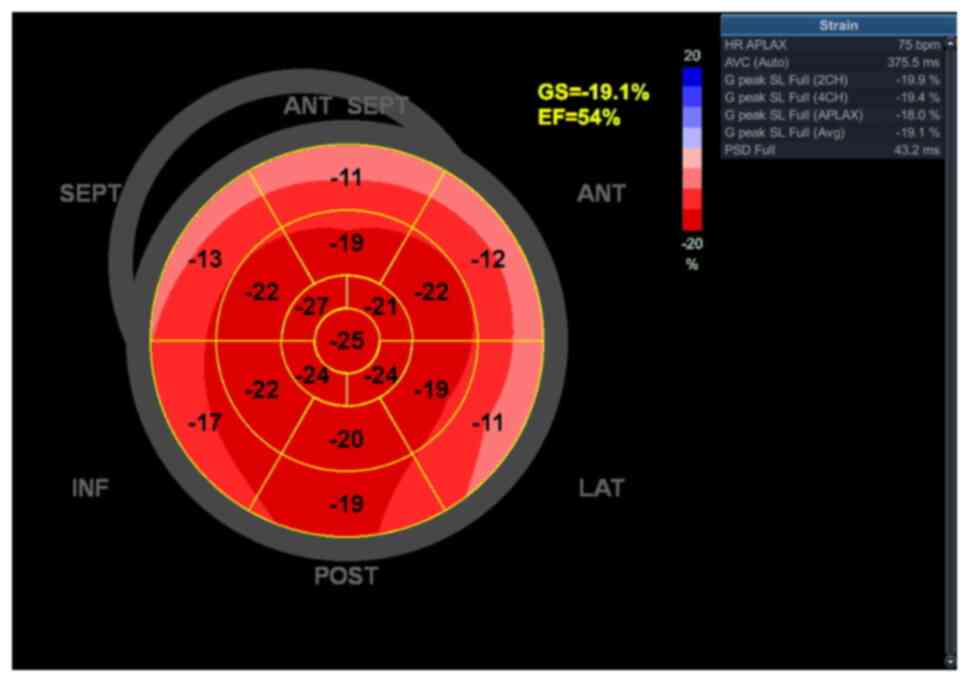

After three cycles of chemotherapy, there were no

marked changes in infectious status (HIV immunological class C3 and

moderate-severe immunosuppression after the hematological diagnosis

and ART change) or cardiac tumor size compared with chemotherapy

initiation, with the persistence of the small tumoral mass at the

level of the RA roof, without any marked growth in size, but with

an improved left ventricular function on longitudinal strain

evaluation (including a GLS of -19.1%, with minimal anterior,

septal and lateral basal dyskinesia and with a calculated EF of

54%, which was an increase from the initial 48%; Fig. 15). This was a marked improvement

from the previous evaluation, perhaps secondary to tumor

infiltration reduction at the level of the left ventricular base.

The ECG objectified a slight reduction in the QRS microvoltage and

sinus rhythm, with no repolarization abnormalities or QTc

prolongation. However, a slightly increased NT-proBNP level was

observed at the end of the third cycle of chemotherapy (1,810

pg/ml), without the presence of any symptoms or signs of heart

failure, with no other cardiovascular complications to date.

| Figure 15Echocardiography bull's-eye plot

recorded after 3 cycles of chemotherapy showing slightly reduced

GS, with minimal dyskinesia localized at the level of the basal

segments of the antero-lateral, antero-septal, septal and lateral

walls and preserved ejection fraction. SEPT, septal wall; ANT,

anterior; LAT, lateral wall; POST, posterior; INF, inferior; GS,

global longitudinal strain; EF, ejection fraction; AVC, aortic

valve closure; HR, heart rate; APLAX, apical long-axis; PSD, peak

strain dispersion; G peak SL, global peak longitudinal strain. |

Literature review and discussion

Hematological malignancies may have multiple

cardiovascular complications, usually related to thrombosis, heart

failure, cardiomyopathy or secondary cardiac metastases, which are

either associated with the primary malignancy or with chemotherapy

(1,2). These complications depend on the

malignancy subtype, with fluid malignancies such as

myeloproliferative neoplasms leading to an increased risk in

thrombosis and lymphoid line neoplasms such as lymphomas

occasionally leading to cardiac metastases (4,5).

Usually, cardiac tumors have a secondary origin,

with primary cardiac tumors being benign in nature and rarely

identified (6,7). Among cardiac tumors, lymphomas

exhibit an incidence in the general population of ~10%, although

the values vary between 8.7-20% according to previous autopsy

studies (8,9). The majority of cardiac lymphomas

appear secondary to disseminated disease and rarely present as

primary cardiac malignancies (10,11).

Even though lymphomas are not the most frequent cardiac tumors

identified, their prevalence increases markedly in PLWHIV, with

>40% of HIV-positive individuals developing AIDS-associated

lymphomas and thus having an increased risk of secondary cardiac

metastases compared with the general population (13).

ART has notably improved the prognosis of PLWHIV in

previous years. In the early ART era HIV infection had multiple

secondary cardiovascular effects documented, such as pericarditis,

endocarditis and dilated cardiomyopathy; nowadays, with improved

immunological control, atherosclerotic heart disease has become the

most important cardiovascular complication in these patients,

mainly due to a higher prevalence of traditional risk factors such

as chronic inflammation and endothelial dysfunction (16), leading to an increased risk in

heart failure, arrhythmias, myocardial infarction or hypertension

(15). However, the increased

incidence of lymphomas, mainly NHL (with DLBCL being the most

frequent subtype, followed by BL) (13), needs to be considered due to the

rapid tumor growth and aggressive nature of these neoplasms,

leading to the necessity of rapidly diagnosing and initiating

treatment in these cases (21).

BLs are a subtype of B-cell lymphomas, characterized by rapid

growth; however, they are rarely a cause for secondary cardiac

metastases, with limited cases documented to date and most of them

having been identified in HIV-positive individuals (12,21).

In this regard, a PubMed literature review was conducted to analyze

adult cardiac BL cases published during the last 15 years

(2010-2025). The search was performed using the keyword ‘cardiac

Burkitt lymphoma’. Inclusion criteria were study publication and

diagnosis between 2010 and 2025, and patients diagnosed with

primary or secondary cardiac BL with the intracardiac mass location

mentioned and with documented age, sex and response to treatment.

All cases of BLL or ambiguous line lymphomas were excluded, as well

as patients aged <18 years (since the prevalence, incidence and

etiology differ markedly compared with the adult population) and

cases without a comprehensive documentation of the diagnostic or

treatment response. Furthermore, 2 cases were excluded, as they

were published in Chinese and could not be translated accurately.

The 13 cases identified are summarized in Table I (21,22,28-38).

| Table IDocumented cases of adult Burkitt

cardiac lymphomas based on a PubMed search of the last 15 years

(2010-2025). |

Table I

Documented cases of adult Burkitt

cardiac lymphomas based on a PubMed search of the last 15 years

(2010-2025).

| First author,

year | Age, years | Sex | Presenting

symptoms | HIV status | Intracardiac mass

location/s | Diagnostic

modality | Treatment

regimen | Outcome | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Tzachanis et

al, 2014 | 44 | F | Early satiety,

abdominal bloating and epigastric discomfort | Negative | Right atrium | CT scan, TTE,

pericardiocentesis and MRI | Cyclophosphamide,

vincristine, doxorubicin and high-dose methotrexate; ifosfamide,

etoposide and high-dose cytarabine; rituximab | Complete

remission | (28) |

| Lazkani et

al, 2015 | 38 | M | Dyspnea,

tachycardia and palpitations | Positive | Right atrium | CT scan, TTE and

MRI | Rituximab,

etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide and

doxorubicin | Remission (6

weeks) | (29) |

| Chan et al,

2016 | 27 | M | Palpitations and

dizziness | Positive | Right atrium, right

ventricular base and interatrial septum | CT scan, TTE and

TEE | Modified

cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and

methotrexate/ifosfamide; etoposide and cytarabine | Partial remission

(12 weeks) | (21) |

| Vervloet et

al, 2017 | 49 | M | Dyspnea, chest pain

and lower limb edema | Positive | Right atrium, left

atrium and interatrial septum | X-ray, TTE and

MRI | Methotrexate and

fractionated high doses of ifosfamide; rituximab, cyclophosphamide,

doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone | Complete

remission | (30) |

| Vilaça et

al, 2017 | 64 | M | Lipothymia, nausea

and palpitations | Positive | Right atrium, right

ventricle base and interventricular apical septum | CT scan, TTE and

MRI | Prednisolone,

vincristine, daunorubicin, L-asparaginase, rituximab and adaptive

radiation therapy | Partial

remission | (22) |

| Usry et al,

2020 | 80 | F | Dyspnea | N/A | Right atrium,

interatrial septum and inlet ventricular septum | TTE and CT

scan | Rituximab,

etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide and

doxorubicin | Partial

remission | (31) |

| Khalid et

al, 2020 | 49 | M | Dyspnea and

palpitations | Positive | Right atrium and

right ventricle base | TTE and CT

scan | Rituximab,

cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin and methotrexate | Partial remission

(complete response N/A) | (32) |

| Chen et al,

2020 | 68 | M | Mild chest pain,

nausea and wheezing | N/A | Right atrium | TTE, CT scan, MRI

and PET-CT | Rituximab,

etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide and

doxorubicin | Complete

remission | (33) |

| Martinez et

al, 2021 | 77 | F | N/A | N/A | Right atrium, left

atrium and interatrial septum | PET-CT, EUS and CT

scan | Rituximab,

etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide and

doxorubicin | Complete

remission | (34) |

| Khaba et al,

2021 | 30 | F | Dyspnea,

non-productive cough and leg edema | Positive | Right atrium | X-ray and TTE | Modified

cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and

methotrexate/ifosfamide; etoposide and cytarabine | Complete

remission | (35) |

| Hérnandez Jimenez

et al, 2021 | 65 | F | Cough, fatigue,

dyspnea and bilateral leg edema | Negative | Right atrium | TTE and MRI | None | Deceased (shortly

after biopsy) | (36) |

| Schmiester et

al, 2022 | 54 | M | Paranasal sinus

swelling, fatigue and dyspnea on exertion | Negative | Right ventricle and

right atrium | CT scan, TTE and

MRI | Cyclophosphamide,

doxorubicin and prednisone; rituximab, vincristine, cytarabine,

etoposide, methotrexate, ifosfamide and dexamethasone; intrathecal

prophylaxis with cytarabine, dexamethasone and methotrexate | Complete

remission | (37) |

| Rector et

al, 2022 | 70 | M | Constipation,

eating discomfort and unintentional weight loss | Negative | Right atrium and

right ventricle | CT scan, TTE and

MRI | Vincristine,

doxorubicin, dexamethasone and rituximab; etoposide, prednisone,

vincristine, cyclophosphamide and hydroxydaunorubicin; intrathecal

methotrexate without complication | Deceased | (38) |

Out of these cases, there were no observed

differences regarding sex (5 female patients and 8 male patients),

with a median age of 55 years and an age range of 27-80 years. The

main presenting symptom was dyspnea (7 cases), with palpitations

being reported by ~1/3 of the patients, who were eventually

diagnosed with cardiac BL (4 cases). There were 4 HIV-negative

patients, 6 HIV-positive patients and 3 patients with their HIV

status not available (no testing was mentioned), outlining the

increased prevalence of cardiac BL in PLWHIV. All the cases

featured RA involvement, with 5 cases having an isolated mass

limited to the RA, without any extension to the other cardiac walls

or chambers, confirming past reviews of literature that noted the

RA as the main and preferred localization of cardiac BL (21,29,33-36).

The majority of patients responded well to treatment, complete

remission documented for 6 cases and partial remission for 5,

although in 2 cases, the patients deceased shortly after therapy

initiation. The chemotherapeutic regimens varied, with multiple

regimens employed across 15 years of evolving oncological

therapies. The main diagnostic method used was transthoracic

echocardiography, which highlights the importance of

echocardiographic evaluation and screening, even when a small level

of suspicion is present. CT scans and MRI were also used as

diagnostic or screening tools (particularly CT scans) or as methods

of in-depth description of the nature and extension of the cardiac

involvement (particularly MRI).

Considering the low prevalence and the aggressive

nature of these cardiac tumors, as outlined in the literature

review and in the aforementioned case presented, a high threshold

of suspicion is necessary when diagnosing these types of cardiac

metastasis and echocardiographic screening is key in these cases

(24,39), particularly in PLWHIV, in whom the

prevalence of cardiac BL is increased compared with the general

population, irrespective of their CD4+ cell count or

immune status (13,21). Beyond standard transthoracic

echocardiography, which is readily available and non-invasive, thus

making it the method of choice when it comes to cardiac evaluation

when an index of suspicion is present, CT scans, cardiac MRI or

transesophageal echocardiography also have a diagnostic role when

it is unclear whether cardiac involvement exists or when a more

in-depth characterization is necessary (9,21).

Often, cardiac BLs are localized solely at the RA level and, in the

majority of cases, there is some RA involvement, even when other

chambers and walls are occupied or infiltrated by tumoral masses,

making the careful evaluation of right atrial morphology and

function key when diagnosing these types of cardiac tumor (21).

Treatment with a hyper CVAD regimen is highly

effective, particularly in BL with high-risk features, and is

associated with a low incidence of CNS relapse (40), although cardiovascular risk

stratification (clinical, biological, imaging modalities and risk

scores, including the aforementioned HFA-ICOS score) and monitoring

of the side effects related to anthracycline treatment (heart

failure, left ventricular dysfunction and cardiomyopathy) is

necessary in patients receiving this protocol (41).

In conclusion, hematological malignancies have

numerous complications, which are either associated with treatment

or with the disease, including, but not limited to, thrombosis,

heart failure, cardiomyopathy, rhythm and rate disturbances. One

notable complication is the potential of these malignancies to

determine cardiac metastases, especially when in tumors of the

lymphoid line. Out of these, NHL, particularly BL and DLBCL, even

though rare in the general population, are much more frequent in

PLWHIV and exhibit rapid and aggressive growth and subsequently, a

markedly poor prognosis. Thus, patients with HIV infection, even

those with a normal CD4+ cell count, need a high index

of suspicion for the diagnosis of these types of lymphoma

(particularly BL and BLL) and secondary cardiac metastases,

especially since rapid diagnosis and initiation of treatment

improves the otherwise poor prognosis of these patients. However,

patients still need to be monitored for adverse cardiovascular

effects, considering that the use of multiple treatment regimens

has demonstrated cardio-toxic effects and also considering the

important chronic and acute cardiovascular complications of HIV

infection, even though, to the best of our knowledge, at present,

there is no clear standardized protocol regarding the evaluation

and follow-up of this group of patients.

The literature review and the case presented in the

present report underline the importance of a high index of

suspicion, echocardiographic screening, rapid diagnosis and

therapeutic intervention in patients with BL with secondary cardiac

metastases and history of HIV infection, even in PLWHIV with a

normal CD4+ count, considering their low prevalence

(even though higher than the prevalence in the general population)

and aggressive nature, as outlined in the sequential

echocardiographic evaluations in the present case report (the rapid

growth of the tumor mass was observed in a short span, doubling in

size over the course of ~3 weeks) and otherwise poor prognosis of

this diagnosis in a occasionally neglected group of patients. The

present case presentation also outlines, in conjunction with the

literature review, the rapid and remarkable response to treatment

(in this case with a hyper CVAD regimen) when a quick diagnosis is

made and an adequate treatment regimen is employed. Additionally,

the patient also particularly presented with no cardiac adverse

effects to the treatment regimen administered, with an increase in

left ventricular function and left ventricular longitudinal strain

during treatment, even in the context of anthracycline treatment.

However, considering the potential cardiotoxicity of the regimen

and of the hematological diseases, periodic cardiologic follow-up

is necessary in these patients, especially during anti-neoplastic

treatment, to identify potential cardiovascular complications and

address them as early as possible.

Supplementary Material

Immunohistochemistry findings

supporting the diagnosis of Burkitt lymphoma. (A) Positive B cell

lymphoma 6 maker. (B) Strongly positive CD10 marker. (C) Negative

multiple myeloma oncogene 1. (D) Negative BCL2. [(A-D)

Magnification, x20; scale bar, 100 μm].

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

AG participated in the design, drafting, reviewing

and rewriting of the article throughout its development. IM

participated in the drafting and reviewing of the manuscript, as

well as in the acquisition and interpretation of the review data.

AC contributed to the design and review of the article and provided

insight into the main cardiovascular complications of hematological

malignancies. MB further revised the article offering substantial

contributions to its design and aided in the comprehensive

description and presentation of HIV-associated cardiovascular

complications. AM and CS were involved in patient care, acquisition

of data and manuscript drafting, offering valuable insight into

patient symptoms, signs and effects to treatment throughout

monitoring. RR contributed by designing and reviewing the data and

describing the patient's HIV status in chronological and logical

order. ALG contributed to the conception of the article, revised

the draft and performed further literature and article reviews,

interpreting, adding and rearranging the data in a logical,

detailed and coherent manner. AG and ALG confirm the authenticity

of all the raw data. All authors read and approved the final

version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Approval from the Medical Ethics Committee for

Clinical Studies of the Coltea Clinical Hospital (Bucharest,

Romania) was obtained prior to submission (approval no.

10/10.07.2025).

Patient consent for publication

Written informed consent for the publication of case

data and images was obtained from the patient prior to

publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Leiva O, Hobbs G, Ravid K and Libby P:

Cardiovascular disease in myeloproliferative neoplasms: JACC:

CardioOncology state-of-the-art review. JACC CardioOncol.

4:166–182. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Herrmann J, McCullough KB and Habermann

TM: How I treat cardiovascular complications in patients with

lymphoid malignancies. Blood. 139:1501–1516. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Gangadharamurthy D and Shih H:

Intracardiac thrombosis in polycythemia vera. BMJ Case Rep.

2013(bcr2012008214)2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Kelliher S and Falanga A: Thrombosis in

myeloproliferative neoplasms: A clinical and pathophysiological

perspective. Thromb Update. 5(100081)2021.

|

|

5

|

Campo E, Stein H, Harris N, et al: Burkitt

lymphoma. In: Swerdlow SH, Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Pileri SA, Stein H,

Thiele J, editors. WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic

and lymphoid tissues. Revised 4th ed. Vol. 2. WHO Press, p. 586,

2018.

|

|

6

|

Bajdechi M, Onciul S, Costache V, Brici S

and Gurghean A: Right atrial lipoma: A case report and literature

review. Exp Ther Med. 24(697)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Tyebally S, Chen D, Bhattacharyya S,

Mughrabi A, Hussain Z, Manisty C, Westwood M, Ghosh AK and Guha A:

Cardiac tumors: JACC CardioOncology state-of-the-art review.

JACC CardioOncol. 2:293–311. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Bussani R, De-Giorgio F, Abbate A and

Silvestri F: Cardiac metastases. J Clin Pathol. 60:27–34.

2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

O'Mahony D, Peikarz RL, Bandettini WP,

Arai AE, Wilson WH and Bates SE: Cardiac involvement with lymphoma:

A review of the literature. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma. 8:249–252.

2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Lichtenberger JP III, Dulberger AR,

Gonzales PE, Bueno J and Carter BW: MR imaging of cardiac masses.

Top Magn Reson Imaging. 27:103–111. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Jeudy J, Burke AP and Frazier AA: Cardiac

lymphoma. Radiol Clin North Am. 54:689–710. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Al-Mehisen R, Al-Mohaissen M and Yousef H:

Cardiac involvement in disseminated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma,

successful management with chemotherapy dose reduction guided by

cardiac imaging: A case report and review of literature. World J

Clin Cases. 7:191–202. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Berhan A, Bayleyegn B and Getaneh Z:

HIV/AIDS associated lymphoma: Review. Blood Lymphat Cancer.

12:31–45. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Bajdechi M, Gurghean A, Bataila V,

Scafa-Udriste A, Radoi R, Oprea AC, Marinescu A, Ion S, Chioncel V,

Nicula A, et al: Cardiovascular risk factors, angiographical

features and short-term prognosis of acute coronary syndrome in

people living with human immunodeficiency virus: Results of a

retrospective observational multicentric Romanian study.

Diagnostics (Basel). 13(1526)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Bajdechi M, Gurghean A, Bataila V,

Scafa-Udriste A, Bajdechi GE, Radoi R, Oprea AC, Chioncel V,

Mateescu I, Zekra L, et al: Particular aspects related to CD4+

level in a group of HIV-infected patients and associated acute

coronary syndrome. Diagnostics (Basel). 13(2682)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Feinstein MJ: HIV and cardiovascular

disease: From insights to interventions. Top Antivir Med.

29:407–411. 2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Yarchoan R and Uldrick TS: HIV-associated

cancers and related diseases. N Engl J Med.

378(2145)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Bush LM, Urrutia JG, Rodriguez EA and

Perez MT: AIDS-associated cardiac lymphoma: A review: Apropos a

case report. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 14:482–490.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Hernández-Ramírez RU, Shiels MS, Dubrow R

and Engels EA: Cancer risk in HIV-infected people in the USA from

1996 to 2012: A population-based, registry-linkage study. Lancet

HIV. 4:e495–e504. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Dolcetti R, Vaccher E and Carbone A:

Lymphoproliferations in people living with HIV: Oncogenic pathways,

diagnostic challenges and new therapeutic opportunities. Cancers

(Basel). 17(2088)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Chan O, Igwe M, Breburda CS and Amar S:

Burkitt lymphoma presenting as an intracardiac mass: Case report

and review of literature. Am J Case Rep. 17:553–558.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Vilaca A, Monteiro M, Pimentel T and

Marques H: Intracardiac mass from Burkitt's lymphoma in an

immunocompromised patient: A very rare form of presentation. BMJ

Case Rep. 2017(bcr2017221001)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Soldea S, Iovanescu M, Berceanu M, Mirea

O, Raicea V, Bezna MC, Rocsoreanu A and Donoiu I: Cardiovascular

disease in HIV patients: A comprehensive review of current

knowledge and clinical implications. Int J Mol Sci.

26(1837)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Bruce CJ: Cardiac tumours: Diagnosis and

management. Heart. 97:151–160. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Lyon AR, Lopez-Fernandez T, Couch LS,

Asteggiano R, Aznar MC, Bergler-Klein J, Boriani G, Cardinale D,

Cordoba R, Cosyns B, et al: 2022 ESC guidelines on cardio-oncology

developed in collaboration with the European hematology

association, the European society for therapeutic radiology and

oncology and the international cardio-oncology society: Developed

by the task force on cardio-oncology of the European society of

cardiology. Eur Heart J. 43:4229–4361. 2022.

|

|

26

|

Harlendea N and Harlendo K: Ki-67 as a

Marker to differentiate Burkitt lymphoma and diffuse large B-cell

lymphoma: A literature review. Cureus. 16(e72190)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Olszewski AJ, Jakobsen LH, Collins GP,

Cwynarski K, Bachanova V, Blum KA, Boughan KM, Bower M, Dalla Pria

A, Danilov A, et al: Burkitt lymphoma international prognostic

index. J Clin Oncol. 39:1129–1138. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Tzachanis D, Dewar R, Luptakova K, Chang

JD and Joyce RM: Primary cardiac Burkitt lymphoma presenting with

abdominal pain. Case Rep Hematol. 2014(687598)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Lazkani M, Rivera-Bonilla T, Eddin M,

Girotra S and Pershad A: The evanescent right atrial mass. Indian

Heart J. 67:485–488. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Vervloet DM, De Pauw M, Demulier L,

Vercammen J, Terryn W, Steel E and Vandekerckhove L: Aggressive

extensive cardiac mass in an HIV-1-infected patient: Should we go

for comfort therapy? Acta Clin Belg. 72:198–200. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Usry CR, Wilson AS and Bush KNV: Primary

cardiac lymphoma manifesting as complete heart block. Case Rep

Cardiol. 2020(3825312)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Khalid K, Faza N, Lakkis NM and Tabbaa R:

Cardiac involvement by Burkitt lymphoma in a 49-year-old man. Tex

Heart Inst J. 47:210–212. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Chen X, Lin Y and Wang Z: Primary cardiac

lymphoma: A case report and review of literature. Int J Clin Exp

Pathol. 13:1745–1749. 2020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Martinez HA, Kuijvenhoven JC and Annema

JT: Intracardiac EUS-B-guided FNA for diagnosing cardiac tumors.

Respiration. 100:918–922. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Khaba MC, Kampetu MF, Rangaka MC, Karodia

M, Ramoroko SP and Madzhia EI: Primary cardiac lymphoma in HIV

infected patients: A clinicopathological report of two cases. Ann

Med Surg (Lond). 69(102757)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Hernandez Jimenez CA, Schlie Villa W and

Ordinola Navarro A: Cardiac Burkitt's lymphoma presenting with

heart failure. QJM. 114:589–590. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Schmiester M, Tranter E, Lorusso A,

Blaschke F, Geisel D, Bullinger L, Damm F and Na IK: Acute left

ventricular insufficiency in a Burkitt lymphoma patient with

myocardial involvement and extensive local tumor cell lysis: A case

report. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 22(31)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Rector G, Koh SJ and Tabbaa R: A case of

isolated cardiac Burkitt lymphoma causing right-sided heart

failure. Tex Heart Inst J. 49(e217575)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

De Filippo M, Chernyschova N, Maffei E,

Rovani C, De Blasi M, Beghi C and Zompatori M: Primary cardiac

Burkitt's type lymphoma: Transthoracic echocardiography,

multidetector computed tomography and magnetic resonance findings.

Acta Radiol. 47:167–171. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Samra B, Khoury JD, Morita K, Ravandi F,

Richard-Carpentier G, Short NJ, El Hussein S, Thompson P, Jain N,

Kantarjian H and Jabbour E: Long-term outcome of hyper-CVAD-R for

Burkitt leukemia/lymphoma and high-grade B-cell lymphoma: Focus on

CNS relapse. Blood Adv. 5:3913–3918. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Cardinale D, Iacopo F and Cipolla CM:

Cardiotoxicity of anthracyclines. Front Cardiovasc Med.

7(26)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

![Representative histopathology and

immunophenotype supporting the diagnosis of Burkitt lymphoma. (A)

Ki-67 proliferation index of ~98%. (B) CD20 highlights diffuse

B-cell phenotype. (C) Nuclear c-Myc expression in ~70% of tumor

cells(D) Standard H&E staining showing diffuse B-cell

infiltrate with strong basophilia and multiple prominent basophilic

nucleoli, with multiple mitoses [(A-C) magnification, x20; scale

bar, 100 µm; (D) magnification, x40; scale bar, 50 µm].](/article_images/etm/31/2/etm-31-02-13046-g10.jpg)