Introduction

O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) is a

DNA repair protein responsible for combating adducts from

O6-guanine (1,2). Alkylation at the O6 position of

guanine renders the DNA vulnerable to point mutation and the

formation of DNA crosslinks; all of which can predispose an

individual to cancer (3). MGMT

protein is expressed in lower amounts in some cancers,

predominantly due to the hypermethylation of the MGMT promoter CpG

(4,5). Abnormal methylation of gene promoters

leads to a loss of gene function, which can confer a selective

advantage to neoplastic cells, similar to the effects seen with

genetic mutations (6). MGMT serves

a pivotal role in repairing DNA damage caused by environmental

carcinogens and alkylating chemotherapy drugs such as temozolomide

(3); therefore, loss of MGMT

function due to promoter methylation compromises DNA repair

mechanisms, rendering tumor cells more vulnerable to alkylating

agents and increasing DNA damage and apoptosis (7-9).

MGMT methylation has been extensively studied in

glioblastoma, where numerous clinical studies have demonstrated

that methylation of the MGMT promoter is an independent predictor

of improved survival. For instance, a meta-analysis of 11 studies

exclusively involving patients with glioblastoma revealed that

patients with a methylated MGMT promoter experienced improved

outcomes, with improvements in overall survival (OS) (10). MGMT promoter methylation also

serves as a predictive marker for chemotherapy response in patients

with glioblastoma (11,12).

Similar to high-grade gliomas (13), emerging data suggests MGMT

methylation is also a prognostic factor for response to treatment

in advanced neuroendocrine tumors (NETs). Studies have documented

an association between MGMT status and clinical outcomes with

alkylating agents (temozolomide, dacarbazine and

streptozotocin-based therapies) in NET (14-16).

A hypermethylated MGMT phenotype has been identified in multiple

premalignant and malignant solid tumors, including colorectal

(17), urothelial (18), pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas

(19) and oral (20) tumors. However, the prognostic role

of MGMT methylation on OS in solid tumors remains to be

determined.

In the present systematic review and meta-analysis,

the prognostic importance of MGMT methylation on OS in solid tumors

was investigated. By pooling data from diverse studies, the

analysis sought to evaluate the prognostic significance of MGMT

methylation across different tumor types and identify cancers where

MGMT methylation may serve as a predictive biomarker.

Materials and methods

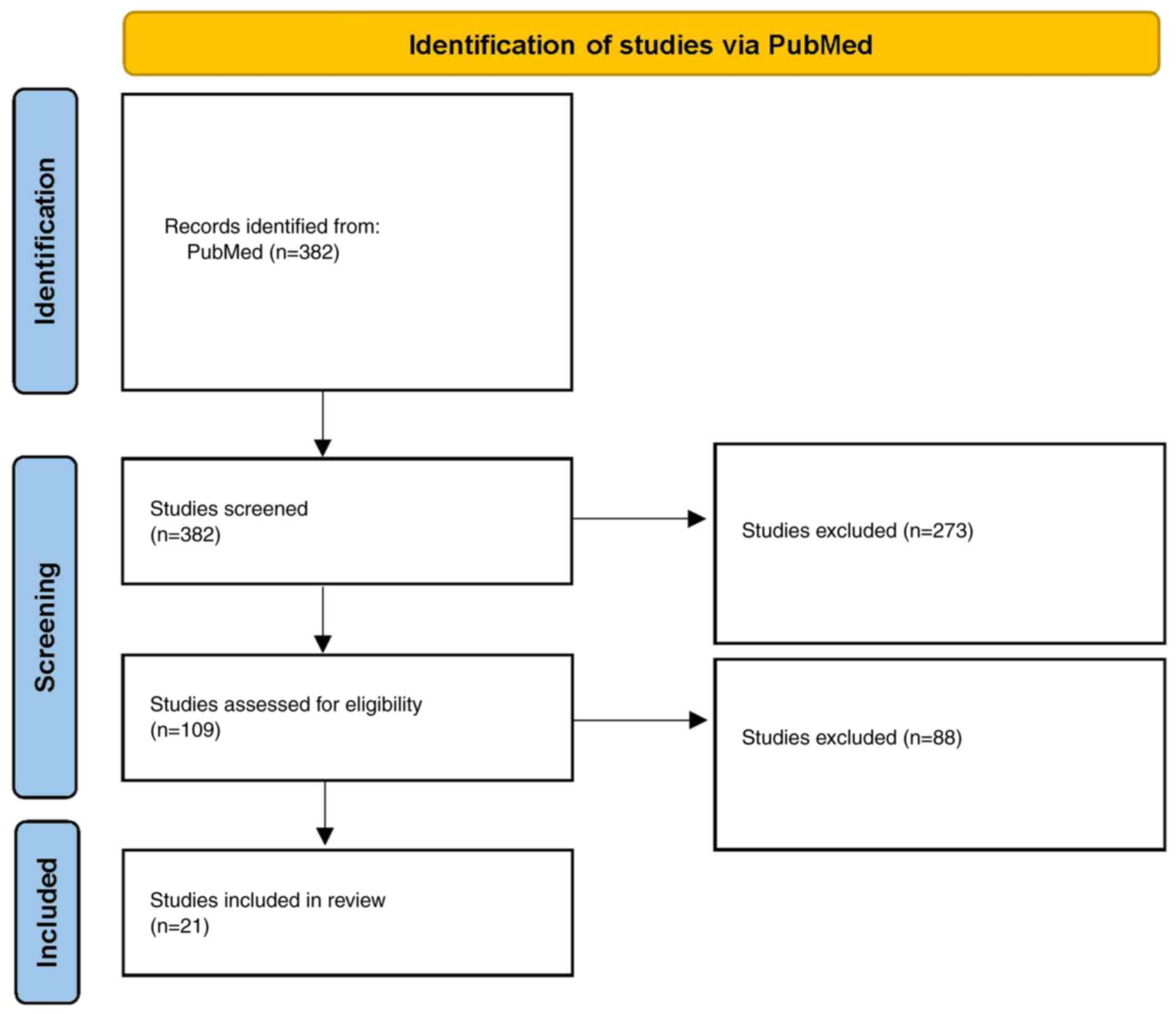

The present meta-analysis and systematic review were

performed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for

Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (21).

Eligibility criteria

Studies were included in the meta-analysis if they

met the following inclusion criteria: i) Population: Only studies

involving human subjects were included, with research based solely

on cell lines without accompanying clinical data, as well as

studies focused on pediatric populations, being excluded.

Additionally, studies concerning gliomas, lymphomas, leukemias or

benign/premalignant conditions were not considered. However,

investigations of brain metastases originating from solid tumors

were included; ii) Methodology: MGMT methylation status had to be

assessed using a method that was stated in detail, and the research

needed to focus on malignant solid tumors; iii) Outcome: OS had to

be reported as a study outcome and presented numerically, through

hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). HR

estimates derived from either univariate or multivariate analyses

comparing MGMT-methylated vs. non-methylated patients were

accepted. When HR or 95% CI values were not provided in a paper,

the paper was excluded; and iv) Language: Finally, only

English-language articles published in peer-reviewed international

journals were included, whereas review papers, meta-analyses and

conference abstracts were excluded.

Search strategy

A systematic search of the literature was conducted

in the PubMed database (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) up to October 26,

2024. The search strategy in PubMed was structured as follows:

[‘MGMT’ (title/abstract) OR ‘O6-methylguanine-DNA

methyltransferase’ (title/abstract)] AND [‘methylation’

(title/abstract) OR ‘promoter methylation’ (title/abstract) OR

‘epigenetic’ (title/abstract)] AND [‘prognosis’ (title/abstract) OR

‘survival’ (title/abstract) OR ‘outcome’ (title/abstract)] OR

‘mortality’ (title/abstract) OR ‘prognostic’ (title/abstract) OR

‘predictive’ (title/abstract)] AND [‘solid tumor’ (title/abstract)

OR ‘solid cancer’ (title/abstract) OR ‘carcinoma’ (title/abstract)

OR ‘sarcoma’ (title/abstract) OR ‘neoplasms’ (Medical Subject

Headings terms) NOT [‘review’ (publication type) OR ‘meta-analysis’

(publication type) OR ‘systematic review’ (publication type)] NOT

[‘glioma’ (title/abstract) OR ‘glioblastoma’ (title/abstract) OR

‘astrocytoma’ (title/abstract) OR ‘brain tumor’ (title/abstract) OR

‘brain cancer’ (title/abstract)].

Study selection and data

extraction

The titles and abstracts were independently screened

two by reviewers, followed by a full-text assessment of studies

that potentially satisfied the eligibility criteria. Any

disagreements were resolved by consulting a third reviewer. Data

extraction was performed using a standard form, capturing the

title, first author, publication year, country, study design,

cancer type, total sample size, number of cases with MGMT

methylation, age, metastatic status, follow-up period, sample type,

detection method, analysis type [multivariate (MV); yes or no], OS

HR and upper and lower CIs.

Meta-analysis

Statistical analyses were performed in R (version

4.4.2; RStudio, Inc.), using the ‘meta’ (22) and ‘metafor’ packages (23). HR and corresponding 95% CI were

utilized to assess the association between MGMT methylation status

and OS. The overall effect estimate was derived using a

fixed-effects model (Mantel-Haenszel method) and a random-effects

model (DerSimonian-Laird method). Heterogeneity was assessed via

Cochran's Q test and the I2 statistic. Heterogeneity was

considered significant when the χ2 test P<0.05 and

the I2 statistic >50% (24); in the presence of significant

heterogeneity, a random-effects model was adopted. Subgroup

analyses stratified by cancer type were performed to explore

heterogeneity sources. Publication bias was evaluated through

funnel plot inspection and Egger's linear regression test. A

sensitivity analysis, excluding individual studies iteratively, was

conducted to assess the robustness of the results. P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Included studies

A total of 21 studies met the inclusion criteria,

comprising 2,946 patients (Fig. 1;

Table I). The most frequently

represented cancer types were colorectal cancer (n=6) and head and

neck cancer (n=6), followed by non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC)

(n=2). The remaining cancer types were each represented by a single

study: Pancreatic NET, biliary tract cancer, cervical cancer,

duodenal cancer, esophageal cancer, leiomyosarcoma and

melanoma.

| Table ICharacteristics of included

studies. |

Table I

Characteristics of included

studies.

| Author, year | Country | Study design | Cancer type | Age (median or

mean) | Patients, n | Patients with MGMT

methylation status | Metastatic patients

included | Metastatic

patients, % | Sampling

method | Methylation

detection method | Multi-variable

analysis | OS, HR (95%

CI) | PFS, HR (95%

CI) | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Gupta et al,

2023 | India | Retrospective | Cervical | 48.44 | 220 | 48 | Yes | 7.30 | Serum | Nested MSP | Yes | 2.50

(1.20-5.19) | Not reported | (25) |

| Cannella et

al, 2023 | Italy | Retrospective |

Leiomyo-sarcoma | 58 | 32 | 32 | Yes | 100 | Tissue | MSP | No | 1.70

(0.66-4.20) | 2.2 (1-4.8) | (26) |

| Jamai et al,

2023 | Tunisia | Retrospective | Colorectal | 63 | 111 | 111 | Yes | 50 | Tissue | MSP | Yes | 1.75

(1.30-2.35) | Not reported | (37) |

| Shima et al,

2011 | USA | Retrospective | Colorectal | 66.2 | 855 | 855 | Yes | NA | Tissue | MethyLight

(Q-MSP) | Yes | 1.08

(0.88-1.32) | Not reported | (39) |

| Fu et al,

2016 | China | Retrospective | Duodenal | 64.2 | 64 | 64 | No | 0 | Tissue | MethyLight

(MSP) | Yes | 4.25

(2.00-9.05) | 2.80

(1.43-5.48) | (33) |

| Niger et al,

2022(29) | Italy | Retrospective | Biliary tract

cancer | 66 | 164 | 164 | Yes | NA | Tissue | Pyrosequencing for

methylation | Yes | 2.31

(1.44-3.71) | 1.24

(0.78-1.98) | (40) |

| Guadagni et

al, 2017 | Italy | Retrospective | Melanoma | 64.1 | 27 | 27 | No | 0 | Tissue | MS-MLPA | Yes | 0.32

(0.12-0.89) | Not reported | (41) |

| Viúdez et

al, 2016(31) | USA | Retrospective | Pancreatic

neuroendocrine cancer | 57 | 92 | 92 | No | 0 | Tissue | MSP | Yes | 2.06

(0.44-9.57) | 1.09

(0.52-2.29) | (42) |

| Supic et al,

2011 | Serbia | Retrospective | Head and neck | 58 | 47 | 47 | No | 0 | Tissue | MSP | No | 1.23

(0.41-3.87) | Not reported | (43) |

| Taioli et

al, 2009 | USA | Retrospective | Head and neck | 62.2 | 88 | 88 | Yes | 39.80 | Tissue | MSP; Q-MS using

pyrosequencing | Yes | 2.17

(1.11-4.23) | 3.49

(1.62-7.52) | (44) |

| Chen et al,

2009(42) | Taiwan | Retrospective | Colorectal | 65.5 | 117 | 117 | Yes | 21.40 | Tissue | MSP | Yes | 1.33

(0.61-2.92) | Not reported | (34) |

| Morano et

al, 2018 | Italy | Prospective | Colorectal | 62 | 25 | 25 | Yes | 100 | Tissue | MSP | No | 0.75

(0.24-2.11) | 0.46

(0.13-0.95) | (45) |

| Safar et al,

2005 | USA | Retrospective | NSCLC | 67 | 105 | 105 | Yes | 22 | Tissue | MSP | Yes | 0.59

(0.21-1.63) | Not reported | (27) |

| Nilsson et

al, 2013(36) | Sweden | Retrospective | Colorectal | NA | 111 | 111 | No | 0 | Tissue | Pyrosequencing for

methylation | Yes | 0.36

(0.15-0.87) | Not reported | (28) |

| Lu et al,

2011 | China | Retrospective | Esophageal | 61.8 | 125 | 120 | Yes | 1 | Tissue | MSP | No | 1.00

(0.55-1.79) | Not reported | (35) |

| Brabender et

al, 2003(37) | Multinational | Retrospective | NSCLC | 63.3 | 90 | 90 | No | 0 | Tissue | Q-MSP (TaqMan) | Yes | 1.89

(1.06-3.37) | 2.60

(1.60-3.60) | (29) |

| Dikshit et

al, 2007 | Multinational | Retrospective | Head and neck | 60.4 | 235 | 212 | No | 0 | Tissue | MSP | Yes | 1.02

(0.66-1.58) | Not reported | (30) |

| Šupić et al,

2009 | Serbia | Retrospective | Head and neck | 58 | 77 | 77 | No | 0 | Tissue | MSP | Yes | 0.67

(0.34-1.33) | Not reported | (31) |

| Li et al,

2014(45) | China | Retrospective | Colorectal | 58.8 | 282 | 282 | Yes | NA | Tissue | MS-HRM | Yes | 1.05

(0.69-1.61) | Not reported | (38) |

| Zuo et al,

2004 | USA | Retrospective | Head and neck | 63.5 | 94 | 94 | Yes | 38 | Tissue | MS-HRM | No | 1.66

(1.11-5.18) | 2.38

(1.14-7.26) | (32) |

| Sun et al,

2012 | USA | Prospective | Head and neck | 58 | 197 | 185 | Yes | 66 | Saliva | Q-MSP | Yes | 0.91

(0.47-1.75) | 0.96

(0.53-1.73) | (36) |

In the included studies, a range of methylation

detection techniques were used, including methylation-specific

polymerase chain reaction (MSP), real-time quantitative MSP and

pyrosequencing. A summary of the study characteristics is provided

in Table I (25-45).

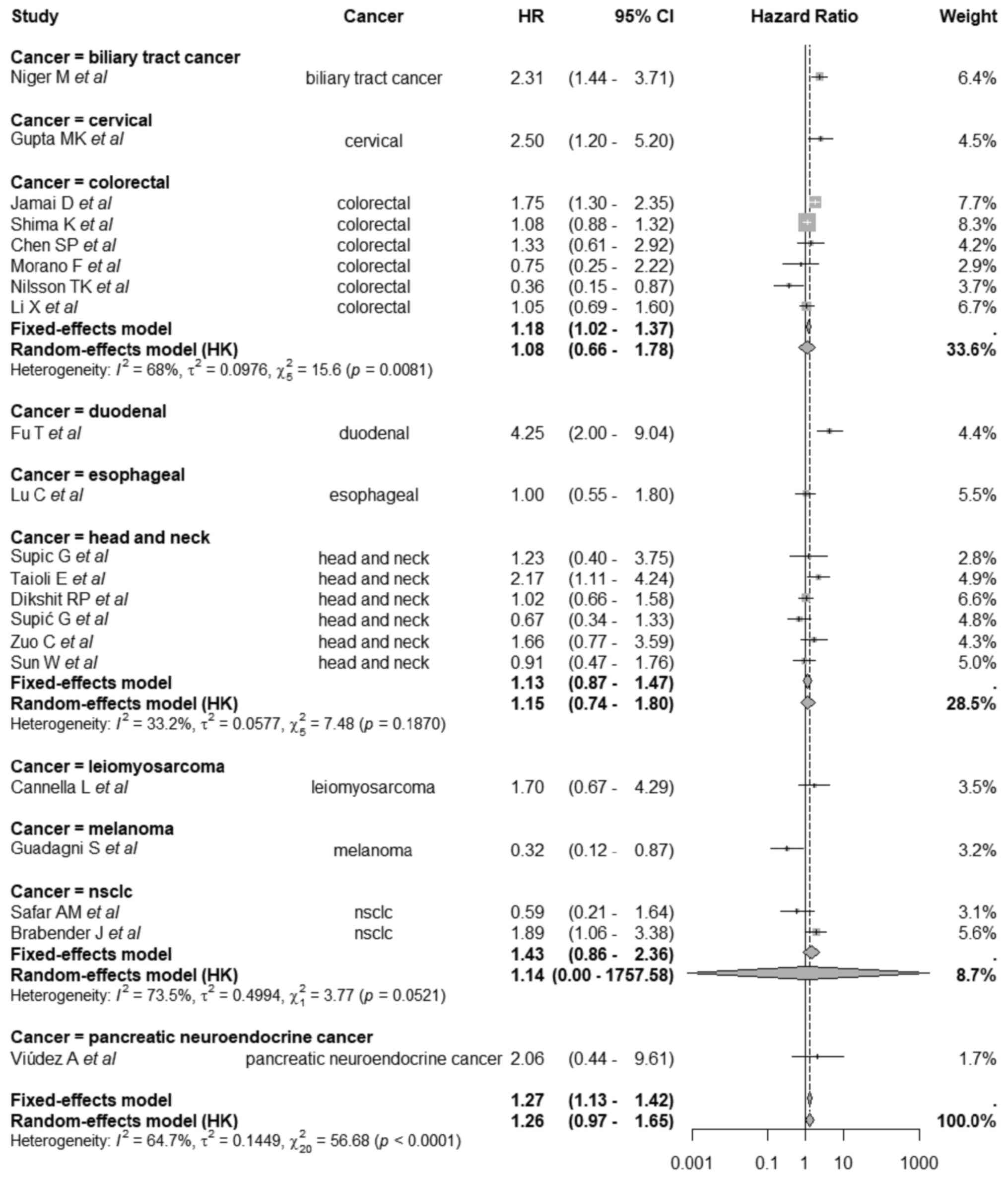

Pooled analysis

A total of two meta-analytic models were computed,

fixed-effects and random-effects. Using the fixed-effects model

(Mantel-Haenszel method), MGMT promoter methylation was

significantly associated with worse OS, with a pooled HR of 1.27

(95% CI, 1.13-1.42; P<0.0001). However, due to significant

heterogeneity across studies [Q=56.68; degrees of freedom (df)=20;

P<0.0001; I2=64.7%], a random-effects model using the

DerSimonian-Laird estimator with Hartung-Knapp adjustment was

employed. Under this model, the association between MGMT

methylation and OS was not statistically significant, with a pooled

HR of 1.26 (95% CI, 0.97-1.65; P=0.084).

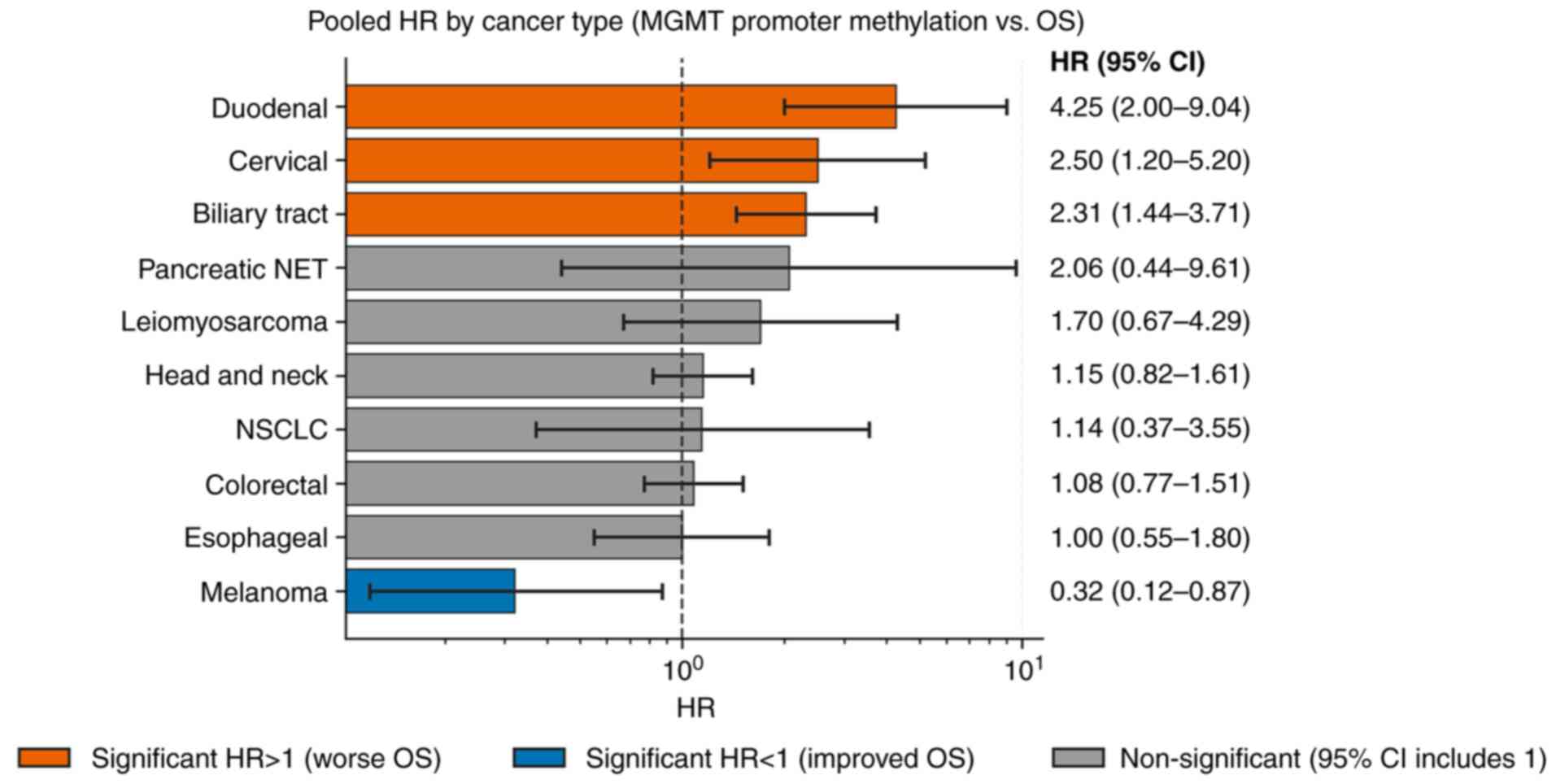

Subgroup analysis

Subgroup analyses stratified by cancer type

demonstrated a significant difference in the effect of MGMT

methylation on OS across tumor types (Q=28.60; df=9; P=0.0008). The

corresponding pooled subgroup HRs and CIs are shown in Figs. 2 and 3. In biliary tract cancer, MGMT

methylation was associated with a significantly worse OS (HR=2.31;

95% CI, 1.44-3.71). A similar detrimental effect was observed in

cervical cancer (HR=2.50; 95% CI, 1.20-5.20) and duodenal cancer,

which showed the highest HR among all subgroups (HR=4.25; 95% CI,

2.00-9.04). By contrast, melanoma demonstrated a significant

association with improved survival (HR=0.32; 95% CI, 0.12-0.87).

For colorectal cancer, the pooled estimate was HR=1.08 (95% CI,

0.77-1.51), indicating a non-significant relationship; similarly,

head and neck cancer showed a non-significant association (HR=1.15;

95% CI, 0.82-1.61). Other cancer types, including esophageal cancer

(HR=1.00; 95% CI, 0.55-1.80), leiomyosarcoma (HR=1.70; 95% CI,

0.67-4.29), NSCLC (HR=1.14, 95% CI, 0.37-3.55) and pancreatic NET

(HR=2.06; 95% CI, 0.44-9.61), were also not significantly

associated with OS.

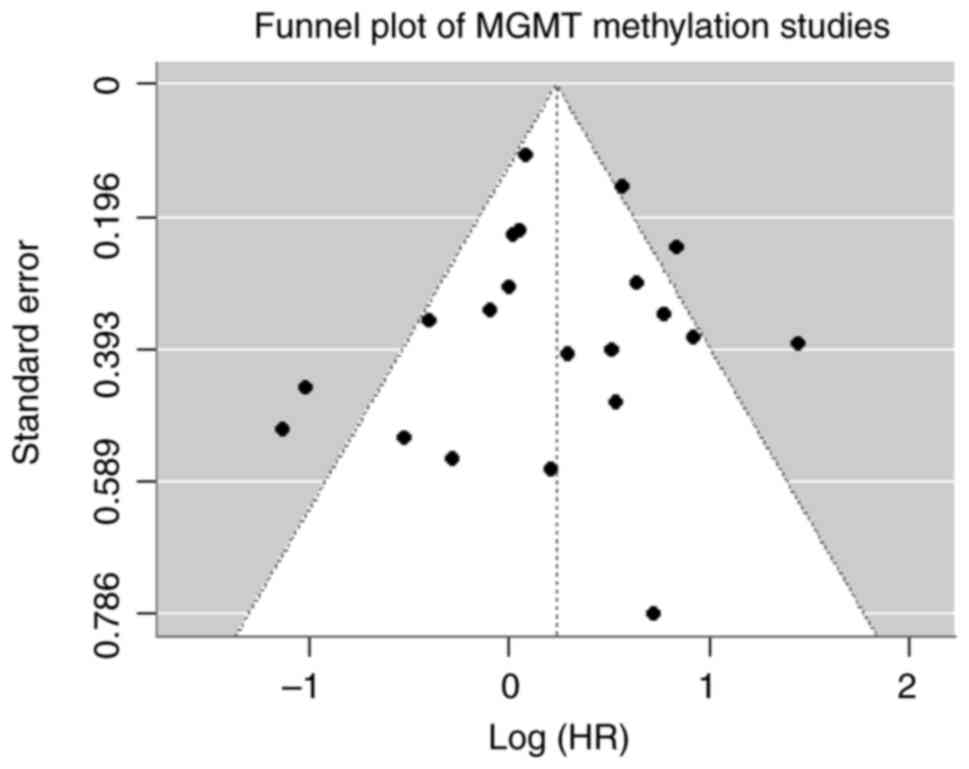

Publication bias

The Egger's regression test was not significant

(t=-0.13; P=0.895), suggesting no substantial evidence of

publication bias among the included studies (Fig. 4).

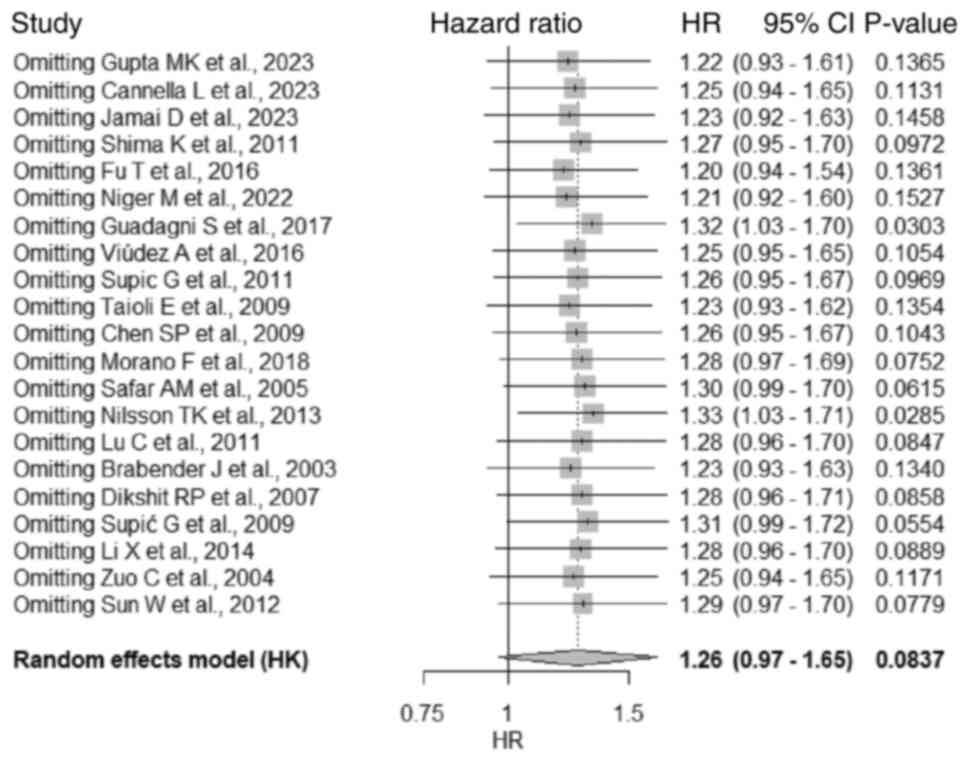

Sensitivity analysis

A leave-one-out sensitivity analysis was performed

for the overall pooled meta-analysis using a random-effects model

with Hartung-Knapp adjustment. The analysis demonstrated that no

single study exerted a disproportionate influence on the overall

pooled estimate. Across all iterations, the HR remained relatively

stable (ranging from 1.20 to 1.33), and heterogeneity

(I2) was within a moderate range (59-67%). Notably, the

removal of certain studies [such as that by Guadagni et al,

2017(41) or that by Nilsson et

al, 2013(28)] led to a

significant association (P<0.05), but the overall findings

remained generally consistent (Fig.

5).

Discussion

Against the backdrop of the need for prognostic

biomarkers for cancer, to the best of our knowledge, the present

meta-analysis investigated for the first time the prognostic

relevance of MGMT promoter methylation on OS across a mix of

non-glioma solid cancers in adult patients. A total of 21 studies

involving 2,946 patients were included, encompassing diverse solid

cancer types. The findings provide a nuanced understanding of the

potential role of MGMT methylation as a prognostic biomarker.

MGMT promoter methylation is a relatively common

epigenetic finding in numerous solid tumors, which are found in

~33% of colorectal cancers (46),

frequently arising early in the adenoma-carcinoma sequence

(47). Similarly, the frequency of

MGMT promoter methylation appears on the order of 20-30% in

patients with duodenal cancer, independent of microsatellite

instability or KRAS status (33).

In head and neck cancers, MGMT promoter methylation occurs in ~47%

of cases (48), and is

consistently observed in a notable portion of oral, pharyngeal and

laryngeal tumors. Such alteration often co-occurs with tobacco and

alcohol exposure and human papillomavirus (HPV) infection,

suggesting a field defect in carcinogenesis (48). Similarly, MGMT promoter methylation

is often part of the HPV-driven CpG island hypermethylation

phenotype in cervical carcinogenesis (49). It occurs in a minority of cervical

carcinomas but rises with disease progression, with 20-30% of

invasive cervical cancers harboring MGMT methylation, increasing

from <5% in low-grade lesions to >25% in invasive cancer

(49).

In NSCLC, frequency of this alteration ranges

between 20-35% of tumors, with MGMT methylation being slightly more

common in advanced-stage NSCLC compared with early-stage disease

(50). Smoking appears to affect

MGMT promoter methylation status in tumors; for example, in

patients with esophageal cancer with a history of heavy tobacco or

betel use, MGMT promoter methylation has been detected in up to 70%

of cases using serum DNA assays (51). Notably, tissue-based studies report

lower frequencies; MGMT methylation is noted in 30-40% of

esophageal tumors (51,52).

Moreover, one-third of pancreatic neuroendocrine

tumors exhibit MGMT hypermethylation and loss of MGMT expression

(53), with MGMT protein loss

occurring more frequently in higher-grade tumors (54). MGMT promoter methylation is

observed in ~38% of biliary tract cancers, with intrahepatic

cholangiocarcinomas showing 38% methylation, extrahepatic

cholangiocarcinomas showing 26% and gallbladder cancers showing up

to 62% (55). In leiomyosarcoma,

MGMT methylation is less studied, but it was reported in a study

that it was present in 5 of 9 uterine leiomyosarcoma cases

(56). By contrast, among

soft-tissue sarcomas overall, MGMT methylation is less common,

occurring in ~13% of cases (57),

and in melanoma, MGMT promoter methylation occurs in 15-30% of

cases (58).

In the present study the pooled analysis under the

fixed-effects model revealed a significant association between MGMT

promoter methylation and worse OS. However, the presence of

substantial heterogeneity (I2=64.7%) warranted the use

of a random-effects model with Hartung-Knapp adjustment, which

yielded a non-significant association.

In the subgroup analysis performed in the present

study, MGMT promoter methylation had variable impact on OS across

cancer types, occasionally reaching significance. The divergent

prognostic effects of MGMT methylation noted on subgroup analysis

may be explained by the role of the MGMT gene in DNA repair.

Encoded by the gene, MGMT protein is a key DNA repair enzyme that

counteracts adduct formation at the O6 position of guanine

(1,2). When alkylated, DNA becomes prone to

point mutations and the formation of crosslinks (3). The resultant compromise in DNA repair

capacity has two major consequences; this includes increased

chemo-sensitivity and genomic instability and progression. Tumor

cells lacking MGMT cannot easily repair the lethal O6 guanine

lesions induced by alkylating chemotherapeutic agents (including

temozolomide and dacarbazine). As a result, MGMT-methylated cancers

are more sensitive to these drugs, manifesting as improved

treatment response and survival. This mechanism underlies the use

of MGMT status to predict benefit from temozolomide in patients

with glioblastoma. In a prospective study, MGMT-promoter

methylation was associated with improved progression-free survival

and OS (although 95% CI were not mentioned) with temozolomide-based

treatment in patients with advanced NETs (53); this was also reported in melanomas

(58). Notably, in the present

analysis, the only cancer showing a significant increase in OS with

MGMT methylation was melanoma, with a HR of 0.32.

On the other hand, MGMT loss permits accumulation of

O6-methylguanine lesions from spontaneous alkylation via

environmental carcinogens or cellular processes (51). These unrepaired lesions lead to a

characteristic G:C to A:T mutation pattern due to misrepair

(51); consequently,

MGMT-methylated cells can acquire additional driver mutations

(46), therefore contributing to

cancer development and progression. This may be associated with the

aforementioned relationship between the exposure to smoking and

betel nut and MGMT promoter methylation status. Moreover, the

mutator phenotype from MGMT loss might produce more aggressive

subclones, associating with advanced stage or recurrence; for

example, MGMT-methylated head and neck squamous cell carcinoma have

been associated with more frequent lymph node metastases and tumor

recurrences (48). In cervical

cancer, methylation-induced MGMT downregulation is associated with

poor survival (49), likely as it

occurs as part of a broader CpG island hypermethylation phenotype

leading to concurrent epigenetic inactivation of multiple tumor

suppressor genes (such as CDKN2A, DAPK, RARB and HIC1) (59,60).

Therefore, in the absence of effective alkylator therapy, MGMT

methylation often portends a worse prognosis due to increased

genomic instability and tumor aggressiveness. According to the

present analysis, cancers demonstrating a significant decrease in

survival were duodenal, biliary tract and cervical cancers.

Finally, the remaining cancer types, colorectal,

esophageal, head and neck, leiomyosarcoma, NSCLC and pancreatic

NET, demonstrated no significant relationship with OS in the

present analysis. Lack of association in the present results does

not exclude the presence of a clinically relevant relationship, as

a subset of patients may still derive an advantage or disadvantage

from harboring MGMT promoter methylation, but further studies are

needed to confirm this.

The present study has several limitations. First,

the evidence is drawn mostly from observational studies, a number

of which studied MGMT promoter methylation status as part of a

larger methylation panel, making results of such studies prone to

bias and confounding. Additionally, such studies are also

predisposed to residual confounding; MGMT promoter methylation

might coincide with other genetic or epigenetic alterations that

drive prognosis, making it challenging to isolate the effect of

MGMT promoter methylation per se. Second, a number of tumor

types were represented by a single study with modest sample sizes;

this limited evidence base within each subgroup reduces statistical

power and confidence in the subgroup-specific estimates. Also, the

inclusion of different cancer subtypes in a single analysis makes

it hard to draw insights on such a heterogeneous group of patients.

Third, there was considerable heterogeneity in the methodologies

for determining MGMT methylation status; for example, there was no

centralized standard for what threshold defines the ‘methylated’

status; this can result in misclassification and variability in

results across studies. Fourth, the high between-study

heterogeneity in the pooled analysis limits the strength of

conclusions from the summary estimate; thus, the lack of a

significant overall effect in the random-effects model may be due

to true differences in effect rather than absence of any biological

effect. Publication bias is another concern, as studies finding a

significant prognostic effect of a biomarker are more likely to be

published. While the present study attempted to assess this (via

funnel plot symmetry and Egger's test), the interpretability was

limited by the small number of studies in numerous subgroups.

Overall, these limitations suggest that the findings should be

interpreted with caution.

There is a need for well-designed prospective

studies that uniformly evaluate MGMT promoter methylation and

follow patients for survival outcomes, especially OS, as

progression-free survival or other potentially surrogate survival

outcomes may not be truly significant for the clinical journey for

the patient. Studies should also work on harmonizing the MGMT

promoter methylation evaluation procedures, which includes agreeing

on an optimal laboratory method and defining clinically relevant

cut-off values.

In summary, MGMT promoter methylation may be

associated with worse OS in select cancer types, but the evidence

remains inconsistent when accounting for heterogeneity. The

findings highlight the importance of tumor-specific context in

biomarker research and reinforce the need for further high-quality

studies to validate the prognostic utility of MGMT methylation.

Moreover, laboratory studies are needed to understand the

mechanisms behind MGMT promoter methylation impact on tumor

behavior, which could inform targeted therapeutic strategies.

Acknowledgements

This abstract was presented at the American Society

of Clinical Oncology annual meeting, June 2025, which was held in

Chicago, Illinois, and was published as Abstract no. 3146.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

AA and FA designed the overall concept and outline

of the manuscript. AA, AK, MAH, RA, IM, HAR and FA contributed to

data collection and review of literature; in addition these authors

contributed to the writing and editing of the manuscript. AA

performed the statistical analysis. All authors have read and

approved the final version of the manuscript. AA and FA confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Montesano R, Becker R, Hall J, Likhachev

A, Lu SH, Umbenhauer D and Wild CP: Repair of DNA alkylation

adducts in mammalian cells. Biochimie. 67:919–928. 1985.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Pegg AE, Dolan ME and Moschel RC:

Structure, function, and inhibition of O6-alkylguanine-DNA

alkyltransferase. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 51:167–223.

1995.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Jacinto FV and Esteller M: MGMT

hypermethylation: A prognostic foe, a predictive friend. DNA Repair

(Amst). 6:1155–1160. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Esteller M, Hamilton SR, Burger PC, Baylin

SB and Herman JG: Inactivation of the DNA repair gene

O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase by promoter hypermethylation

is a common event in primary human neoplasia. Cancer Res.

59:793–797. 1999.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Qian XC and Brent TP: Methylation hot

spots in the 5'flanking region denote silencing of the

O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase gene. Cancer Res.

57:3672–3677. 1997.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Jones PA and Baylin SB: The fundamental

role of epigenetic events in cancer. Nat Rev Genet. 3:415–428.

2002.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Bernd K, Fritz G, Mitra S and Coquerelle

T: Transfection and expression of human O6-methylguanine-DNA

methyltransferase (MGMT) cDNA in Chinese hamster cells: The role of

MGMT in protection against the genotoxic effects of alkylating

agents. Carcinogenesis. 12:1857–1867. 1991.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Glassner BJ, Weeda G, Allan JM, Broekhof

JLM, Carls NHE, Donker I, Engelward BP, Hampson RJ, Hersmus R,

Hickman MJ, et al: DNA repair methyltransferase (Mgmt) knockout

mice are sensitive to the lethal effects of chemotherapeutic

alkylating agents. Mutagenesis. 14:339–347. 1999.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Hansen RJ, Nagasubramanian R, Delaney SM,

Samson LD and Dolan ME: Role of O6-methylguanine-DNA

methyltransferase in protecting from alkylating agent-induced

toxicity and mutations in mice. Carcinogenesis. 28:1111–1116.

2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Wang S, Song C, Zha Y and Li L: The

prognostic value of MGMT promoter status by pyrosequencing assay

for glioblastoma patients' survival: A meta-analysis. World J Surg

Oncol. 14(261)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Hegi ME, Diserens AC, Gorlia T, Hamou MF,

de Tribolet N, Weller M, Kros JM, Hainfellner JA, Mason W, Mariani

L, et al: MGMT gene silencing and benefit from temozolomide in

glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 352:997–1003. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Hegi ME, Liu L, Herman JG, Stupp R, Wick

W, Weller M, Mehta MP and Gilbert MR: Correlation of

O6-Methylguanine Methyltransferase (MGMT) promoter methylation with

clinical outcomes in glioblastoma and clinical strategies to

modulate MGMT activity. J Clin Oncol. 26:4189–4199. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Esteller M, Garcia-Foncillas J, Andion E,

Goodman SN, Hidalgo OF, Vanaclocha V, Baylin SB and Herman JG:

Inactivation of the DNA-repair gene MGMT and the clinical response

of gliomas to alkylating agents. N Engl J Med. 343:1350–1354.

2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Kulke MH, Hornick JL, Frauenhoffer C,

Hooshmand S, Ryan DP, Enzinger PC, Meyerhardt JA, Clark JW, Stuart

K, Fuchs CS and Redston MS: O6-methylguanine DNA methyltransferase

deficiency and response to Temozolomide-based therapy in patients

with neuroendocrine tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 15:338–345.

2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Walter T, Van Brakel B, Vercherat C,

Hervieu V, Forestier J, Chayvialle JA, Molin Y, Lombard-Bohas C,

Joly MO and Scoazec JY: O6-Methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase

status in neuroendocrine tumours: Prognostic relevance and

association with response to alkylating agents. Br J Cancer.

112:523–531. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Kunz PL, Graham NT, Catalano PJ, Nimeiri

HS, Fisher GA, Longacre TA, Suarez CJ, Martin BA, Yao JC, Kulke MH,

et al: Randomized study of temozolomide or temozolomide and

capecitabine in patients with advanced pancreatic neuroendocrine

tumors (ECOG-ACRIN E2211). J Clin Oncol. 41:1359–1369.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Svrcek M, Buhard O, Colas C, Coulet F,

Dumont S, Massaoudi I, Lamri A, Hamelin R, Cosnes J, Oliveira C, et

al: Methylation tolerance due to an O6-methylguanine DNA

methyltransferase (MGMT) field defect in the colonic mucosa: An

initiating step in the development of mismatch repair-deficient

colorectal cancers. Gut. 59:1516–1526. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Millis SZ, Bryant D, Basu G, Bender R,

Vranic S, Gatalica Z and Vogelzang NJ: Molecular profiling of

infiltrating urothelial carcinoma of bladder and nonbladder origin.

Clin Genitourin Cancer. 13:e37–e49. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Hadoux J, Favier J, Scoazec JY, Leboulleux

S, Ghuzlan AAl, Caramella C, Déandreis D, Borget I, Loriot C,

Chougnet C, et al: SDHB mutations are associated with response to

temozolomide in patients with metastatic pheochromocytoma or

paraganglioma. Int J Cancer. 135:2711–2720. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Mithani SK, Mydlarz WK, Grumbine FL, Smith

IM and Califano JA: Molecular genetics of premalignant oral

lesions. Oral Dis. 13:126–133. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron

I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan

SE, et al: The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for

reporting systematic reviews. PLoS Med. 18(e1003583)2021.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Balduzzi S, Rücker G and Schwarzer G: How

to perform a Meta-analysis with R: A practical tutorial. Evid Based

Ment Health. 22:153–160. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Viechtbauer W: Conducting Meta-analyses in

R with the metafor package. J Stat Softw. 36:1–48. 2010.

|

|

24

|

Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ and

Altman DG: Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ.

327:557–560. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Gupta MK, Kushwah AS, Singh R, Srivastava

K and Banerjee M: Genetic and epigenetic alterations in MGMT gene

and correlation with concomitant chemoradiotherapy (CRT) in

cervical cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 149:15159–15170.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Cannella L, Della Monica R, Marretta AL,

Iervolino D, Vincenzi B, De Chiara AR, Clemente O, Buonaiuto M,

Barretta ML, Di Mauro A, et al: The impact of O6-Methylguanine-DNA

methyltransferase (MGMT) promoter methylation on the outcomes of

patients with leiomyosarcoma treated with dacarbazine. Cells.

12(1635)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Safar AM, Spencer H III, Su X, Coffey M,

Cooney CA, Ratnasinghe LD, Hutchins LF and Fan CY: Methylation

profiling of archived non-small cell lung cancer: A promising

prognostic system. Clin Cancer Res. 11:4400–4405. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Nilsson TK, Löf-Öhlin ZM and Sun XF: DNA

methylation of the p14ARF, RASSF1A and APC1A genes as an

independent prognostic factor in colorectal cancer patients. Int J

Oncol. 42:127–133. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Brabender J, Usadel H, Metzger R,

Schneider PM, Park J, Salonga D, Tsao-Wei DD, Groshen S, Lord RV,

Takebe N, et al: Quantitative O(6)-methylguanine DNA

methyltransferase methylation analysis in curatively resected

non-small cell lung cancer: Associations with clinical outcome.

Clin Cancer Res. 9:223–227. 2003.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Dikshit RP, Gillio-Tos A, Brennan P, De

Marco L, Fiano V, Martinez-Peñuela JM, Boffetta P and Merletti F:

Hypermethylation, risk factors, clinical characteristics, and

survival in 235 patients with laryngeal and hypopharyngeal cancers.

Cancer. 110:1745–1751. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Šupić G, Kozomara R, Branković-Magić M,

Jović N and Magić Z: Gene hypermethylation in tumor tissue of

advanced oral squamous cell carcinoma patients. Oral Oncol.

45:1051–1057. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Zuo C, Ai L, Ratliff P, Suen JY, Hanna E,

Brent TP and Fan CY: O6-Methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase gene:

Epigenetic silencing and prognostic value in head and neck squamous

cell carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 13:967–975.

2009.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Fu T, Sharmab A, Xie F, Liu Y, Li K, Wan

W, Baylin SB, Wolfgang CL and Ahuja N: Methylation of MGMT is

associated with poor prognosis in patients with stage III duodenal

adenocarcinoma. PLoS One. 11(e0162929)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Chen SP, Chiu SC, Wu CC, Lin SZ, Kang JC,

Chen YL, Lin PC, Pang CY and Harn HJ: The association of

methylation in the promoter of APC and MGMT and the prognosis of

Taiwanese CRC patients. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 13:67–71.

2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Lu C, Xie H, Wang F, Shen H and Wang J:

Diet folate, DNA methylation and genetic polymorphisms of MTHFR

C677T in association with the prognosis of esophageal squamous cell

carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 11(91)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Sun W, Zaboli D, Wang H, Liu Y,

Arnaoutakis D, Khan T, Khan Z, Koch WM and Califano JA: Detection

of TIMP3 promoter hypermethylation in salivary rinse as an

independent predictor of local recurrence-free survival in head and

neck cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 18:1082–1091. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Jamai D, Gargouri R, Selmi B and Khabir A:

ERCC1 and MGMT methylation as a predictive marker of relapse and

FOLFOX response in colorectal cancer patients from south tunisia.

Genes (Basel). 14(1467)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Li X, Hu F, Wang Y, Yao X, Zhang Z, Wang

F, Sun G, Cui BB, Dong X and Zhao Y: CpG island methylator

phenotype and prognosis of colorectal cancer in Northeast China.

Biomed Res Int. 2014(236361)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Shima K, Morikawa T, Baba Y, Nosho K,

Suzuki M, Yamauchi M, Hayashi M, Giovannucci E, Fuchs CS and Ogino

S: MGMT promoter methylation, loss of expression and prognosis in

855 colorectal cancers. Cancer Causes Control. 22:301–309.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Niger M, Nichetti F, Casadei-Gardini A,

Morano F, Pircher C, Tamborini E, Perrone F, Canale M, Lipka DB,

Vingiani A, et al: MGMT inactivation as a new biomarker in patients

with advanced biliary tract cancers. Mol Oncol. 16:2733–2746.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Guadagni S, Fiorentini G, Clementi M,

Palumbo G, Masedu F, Deraco M, De Manzoni G, Chiominto A, Valenti M

and Pellegrini C: MGMT methylation correlates with melphalan pelvic

perfusion survival in stage III melanoma patients: A pilot study.

Melanoma Res. 27:439–447. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Viúdez A, Carvalho FLF, Maleki Z, Zahurak

M, Laheru D, Stark A, Azad NS, Wolfgang CL, Baylin S, Herman JG, et

al: A new immunohistochemistry prognostic score (IPS) for

recurrence and survival in resected pancreatic neuroendocrine

tumors (PanNET). Oncotarget. 7:24950–24961. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Supic G, Kozomara R, Jovic N, Zeljic K and

Magic Z: Prognostic significance of tumor-related genes

hypermethylation detected in cancer-free surgical margins of oral

squamous cell carcinomas. Oral Oncol. 47:702–708. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Taioli E, Ragin C, Wang X hong, Chen J,

Langevin SM, Brown AR, Gollin SM, Garte S and Sobol RW: Recurrence

in oral and pharyngeal cancer is associated with quantitative MGMT

promoter methylation. BMC Cancer. 9(354)2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Morano F, Corallo S, Niger M, Barault L,

Milione M, Berenato R, Moretto R, Randon G, Antista M, Belfiore A,

et al: Temozolomide and irinotecan (TEMIRI regimen) as salvage

treatment of irinotecan-sensitive advanced colorectal cancer

patients bearing MGMT methylation. Ann Oncol. 29:1800–1806.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Ogino S, Kawasaki T, Kirkner GJ, Suemoto

Y, Meyerhardt JA and Fuchs CS: Molecular correlates with MGMT

promoter methylation and silencing support CpG island methylator

phenotype-Low (CIMP-Low) in colorectal cancer. Gut. 56:1564–1571.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Li Y, Lyu Z, Zhao L, Cheng H, Zhu D, Gao

Y, Shang X and Shi H: Prognostic value of MGMT methylation in

colorectal cancer: A meta-analysis and literature review. Tumour

Biol. 36:1595–1601. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Cai F, Xiao X, Niu X, Shi H and Zhong Y:

Aberrant Methylation of MGMT Promoter in HNSCC: A Meta-Analysis.

PLoS One. 11(e0163534)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Choi B, Na Y, Whang MY, Ho JY, Han MR,

Park SW, Song H, Hur SY and Choi YJ: MGMT Methylation is associated

with human papillomavirus infection in cervical dysplasia: A

longitudinal study. J Clin Med. 12(6188)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Chen L, Wang Y, Liu F, Xu L, Peng F, Zhao

N, Fu B, Zhu Z, Shi Y, Liu J, et al: A systematic review and

meta-analysis: Association between MGMT hypermethylation and the

clinicopathological characteristics of non-small-cell lung

carcinoma. Sci Reports. 8(1439)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Das M, Sharma SK, Sekhon GS, Saikia BJ,

Mahanta J and Phukan RK: Promoter methylation of MGMT gene in serum

of patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in North East

India. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 15:9955–9960. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Zhang L, Lu W, Miao X, Xing D, Tan W and

Lin D: Inactivation of DNA repair gene O6-methylguanine-DNA

methyltransferase by promoter hypermethylation and its relation to

p53 mutations in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma.

Carcinogenesis. 24:1039–1044. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Brighi N, Lamberti G, Andrini E, Mosconi

C, Manuzzi L, Donati G, Lisotti A and Campana D: Prospective

evaluation of MGMT-Promoter methylation status and correlations

with outcomes to Temozolomide-based chemotherapy in

Well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumors. Curr Oncol.

30:1381–1394. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Yagi K, Ono H, Kudo A, Kinowaki Y, Asano

D, Watanabe S, Ishikawa Y, Ueda H, Akahoshi K, Tanaka S and Tanabe

M: MGMT is frequently inactivated in pancreatic NET-G2 and is

associated with the therapeutic activity of STZ-based regimens. Sci

Reports. 13(7535)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Niger M, Morano F, Manglaviti S, Nichetti

F, Tamborini E, Perrone F, Marcuzzo M, Peverelli G, Brambilla M,

Pagani F, et al: 732P-Is MGMT methylation a new therapeutic target

for biliary tract cancer? Ann Oncol. 30(v281)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Bujko M, Kowalewska M, Danska-Bidzinska A,

Bakula-Zalewska E, Siedecki JA and Bidzinski M: The promoter

methylation and expression of the O6-methylguanine-DNA

methyltransferase gene in uterine sarcoma and carcinosarcoma. Oncol

Lett. 4:551–555. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Jakob J, Hille M, Sauer C, Ströbel P, Wenz

F and Hohenberger P: O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT)

Promoter methylation is a rare event in soft tissue sarcoma. Radiat

Oncol. 7(180)2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Schraml P, Von Teichman A, Mihic-Probst D,

Simcock M, Ochsenbein A, Dummer R, Michielin O, Seifert B, Schläppi

M, Moch H and von Moos R: Predictive value of the MGMT promoter

methylation status in metastatic melanoma patients receiving

First-line temozolomide plus bevacizumab in the trial SAKK 50/07.

Oncol Rep. 28:654–668. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Kazanets A, Shorstova T, Hilmi K, Marques

M and Witcher M: Epigenetic silencing of tumor suppressor genes:

Paradigms, puzzles, and potential. Biochim Biophys Acta.

1865:275–288. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Esteller M: CpG island hypermethylation

and tumor suppressor genes: A booming present, a brighter future.

Oncogene. 21:5427–5440. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|