Introduction

Pulmonary fibrosis (PF) is a chronic, fatal disease

characterized by progressive lung tissue scarring and functional

decline, ultimately leading to impaired gas exchange. The core

pathological mechanisms involve aberrant fibroblast activation,

excessive extracellular matrix deposition, persistent oxidative

stress and chronic inflammation (1,2).

Idiopathic PF, the most common form of PF, has a median survival of

only 2.5-3.5 years and to the best of our knowledge, there is no

curative treatment at present (3).

Present clinical therapies, such as pirfenidone and nintedanib, can

only slow disease progression but are associated with side effects,

including gastrointestinal disturbances and hepatic toxicity

(4). Given these limitations,

naturally derived compounds such as quercetin have garnered notable

translational interest due to their multi-target mechanisms and

favorable safety profiles. Therefore, exploring naturally derived

compounds with favorable safety profiles to intervene in the

fibrotic process has become a promising area of research.

Quercetin (3,5,7,3',4'-pentahydroxyflavone) is a

natural flavonoid compound found in plants such as apples, onions

and tea and in Traditional Chinese Medicine, is known for its

multifaceted biological activities (5,6). In

recent years, an increasing number of studies have demonstrated the

potential therapeutic effects of quercetin in PF. Research has

shown that quercetin can inhibit the onset and progression of PF

through numerous mechanisms, such as suppressing the production of

inflammatory cytokines, promoting apoptosis and inhibiting the

expression and activity of TGF-β1 (7-9).

Furthermore, quercetin exhibits a good safety profile, is low-cost

and readily accessible (10),

making it a notable area of research interest. Existing studies

(11,12) primarily focus on animal models and

in vitro mechanisms, while clinical translational evidence

remains insufficient. In addition, while in vitro and animal

studies provide valuable evidence, the translational potential of

quercetin may be affected by the fragmented nature of preclinical

data and methodological heterogeneity.

To address the aforementioned issues, the present

meta-analysis consolidates preclinical evidence to quantitatively

assess the efficacy of quercetin in improving outcomes related to

PF. By accumulating data on fibrotic markers, inflammatory

cytokines and oxidative stress parameters, the present review

systematically evaluates the therapeutic effects of quercetin in

PF. The findings aim to provide a theoretical basis for clinical

trials exploring quercetin as an adjunctive treatment for PF,

advancing its experimental potential toward clinical efficacy.

Materials and methods

Literature search strategy

A systematic search was performed across PubMed

(https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), Web

of Science (https://www.webofscience.com/), Embase (https://www.embase.com/), Ovid (https://ovidsp.ovid.com/) and Cochrane Library

(https://www.cochranelibrary.com/)

databases between inception and January 1, 2025. Following the

population, intervention, comparison, outcomes and study (PICOS)

framework (13), the search

strategy was designed using the keywords ‘quercetin’ and ‘pulmonary

fibrosis’, including both subject headings and free terms. The

detailed search strategy is provided in Tables SI, SII, SIII, SIV and SV. The search approach included

keywords, full-text searches and Medical Subject Headings, with no

restrictions on publication type, sample size, study design or

methods of exposure or outcome measurement. In addition, gray

literature was manually searched using Google Scholar (https://scholar.google.com/). The present study is a

secondary analysis and did not require ethical approval for animal

or human experiments.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were established based on the

PICOS framework and were as follows: i) Population [animal models

of PF (rodents)]; ii) intervention (monotherapy with quercetin or

its derivatives); iii) comparator (placebo or blank control); iv)

outcome; and v) study design (randomized or non-randomized

controlled trials with full text available).

Several outcome measures were considered suitable.

The outcome measures assessed were: i) Basic characteristics [body

weight and lung index (lung index=lung weight (mg)/body weight

(g)]; ii) fibrosis markers [hydroxyproline content, Ashcroft score

(14), α-smooth muscle actin

(α-SMA) and collagen I (Col I)]; iii) inflammatory cytokines

(TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, TGF-β1, total cell count, leukocyte count,

neutrophils, lymphocytes, eosinophils and macrophages); and iv)

oxidative stress indictors [superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity,

malondialdehyde (MDA) levels, glutathione (GSH), catalase (CAT),

nitric oxide (NO) and thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances

(TBARS)].

Exclusion criteria for article screening were as

follows: i) Exclusively in vitro studies, clinical trials,

reviews or conference abstracts; and ii) incomplete data (for

example, charts with unannotated values), duplicate publications or

studies where the full text was unavailable.

Literature screening and data

extraction

For screening, two independent researchers conducted

separate literature searches using the predefined search strategy.

The search results were imported into NoteExpress software (version

4.0.0.9855; Beijing Aegean Software Co., Ltd.) and checked for

duplicates. Next, the titles and abstracts were initially screened

according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, after which the

full texts of the selected studies were read for further screening.

The basic information of the studies that were ultimately included

was extracted. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion

or consultation with a third-party expert to reach a consensus.

Data extraction followed the guidelines outlined in the Preferred

Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (15) statement. The following data were

extracted from the studies: i) Study characteristics, authors,

publication year, species/strain, sex, age, sample size and

modeling methods; ii) intervention details, quercetin dosage,

administration route and intervention duration; iii) outcome

measures, mean values, SD and sample size (n) for both experimental

and control groups; and iv) methodological quality, information on

randomization, blinding and allocation concealment, among others.

If different dosages were used in the studies, the highest dosage

results were extracted. When results were measured at multiple time

points, data from the longest duration were recorded. If the data

were presented solely in graphical form, the authors were contacted

to obtain the raw data. If no response was received, numerical

values were extracted using Engauge Digitizer software (version

12.1; Engauge Open Source Developers). If different values were

obtained by the two researchers, the mean of the value was

calculated to produce a single estimate for analysis, thereby

reducing measurement error.

Quality assessment/bias risk

analysis

The risk of bias in animal studies was assessed

using the SYRCLE risk of bias tool (16), which includes 10 categories: i)

Sequence generation; ii) baseline characteristics; iii) allocation

concealment; iv) random housing; v) blinding implementation; vi)

random outcome assessment; vii) blinded outcome assessment; viii)

incomplete outcome data; ix) selective outcome reporting; and x)

other sources of bias. Each category was rated as high, unclear or

low risk of bias. Quality assessment was performed by three

researchers and any discrepancies in the ratings were resolved

through discussion.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using RevMan (version

5.4; The Cochrane Collaboration) and Stata (version 17.0; StataCorp

LP) software. Continuous variables are expressed as standardized

mean differences (SMDs) with 95% CI. Heterogeneity was assessed

using the I2 statistic (with I2 >50%

indicating significant heterogeneity). A random-effects model was

applied when I2 >50%, while a fixed-effects model was

used when I2 ≤50%. To explore potential sources of

heterogeneity, an exploratory meta-regression analysis was

performed on all available data, incorporating study

characteristics as covariates. Publication bias was evaluated both

visually using funnel plots and statistically using Egger's linear

regression test and Begg's rank correlation test. P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

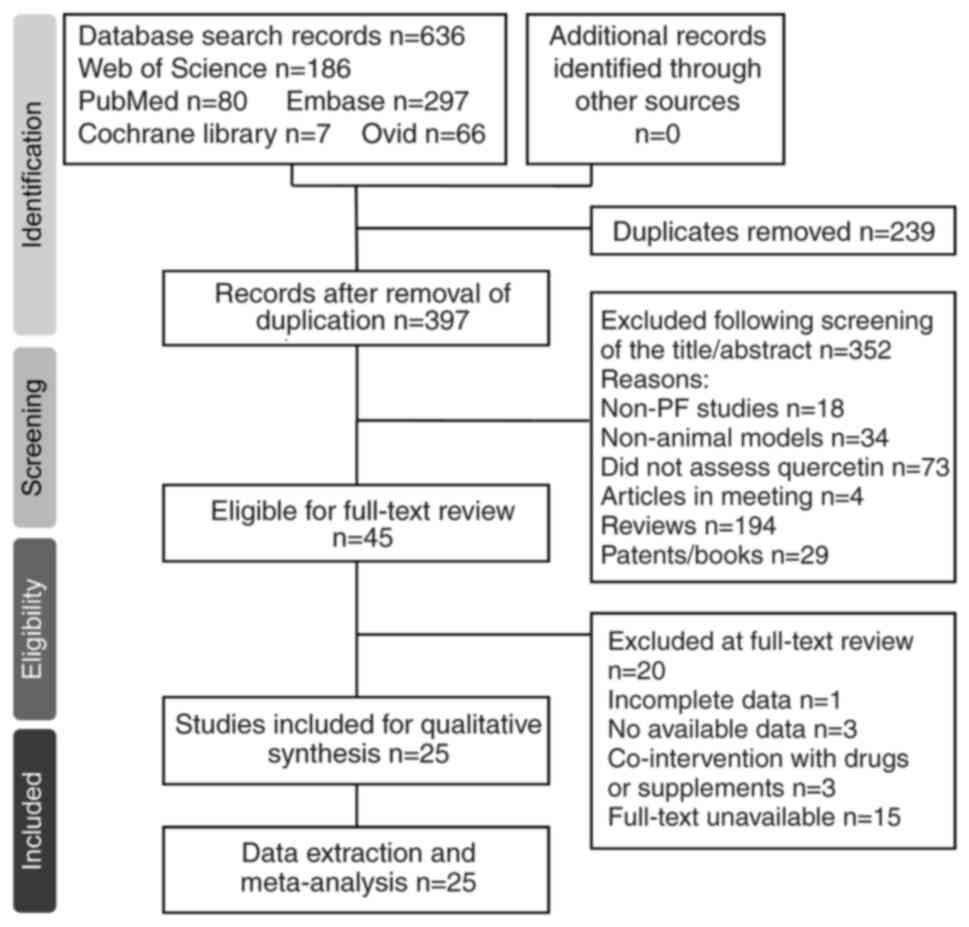

Search results

Literature searches yielded a total of 636 articles

(PubMed, 80; Web of Science, 186; Embase, 297; Cochrane Library, 7;

Ovid, 66). After removing 23 duplicated articles, 613 articles were

screened based on titles and abstracts, resulting in the exclusion

of 352 studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria. Full-text

evaluation was performed on 45 articles, leading to the exclusion

of 20 studies due to irrelevance or incomplete data. Manual

searching on Google Scholar did not reveal any additional

qualifying studies. Ultimately, 25 studies (17-41)

were included in the present meta-analysis (Fig. 1). The basic characteristics of the

included studies are shown in Table

I.

| Table IBasic characteristics of the included

studies. |

Table I

Basic characteristics of the included

studies.

| First author,

year | Country | Age | Total, n | Species; model | PF induction

method | Quercetin dose

(route) | Duration | Outcome | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Baowen et

al, 2010 | China | N | 40 | Rats;

Sprague-Dawley | Bleomycin

(intratracheal) | 5 mg/kg

(intravenous) | 28 days | TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6,

total cell numbers, lymphocytes, neutrophils, macrophages and

hydroxyproline | (17) |

| Mehrzadi et

al, 2021 | Iran | N | 20 | Male rats;

Wistar | Bleomycin

(intratracheal) | 75 mg/kg (oral

gavage) | 28 days | TNF-α, IL-6, GSH,

CAT, NO, TBARS, Ashcroft score, lung index and hydroxyproline | (18) |

| Martinez et

al, 2008 | Brazil | N | 28 | Male hamsters;

Mesocricetus auratus | Bleomycin

(intratracheal) | 30 mg/kg

(intraperitoneal) | 14 days | GSH, TBARS and

hydroxyproline | (19) |

| Verma et al,

2013 | India | 10-12 weeks | 20 | Male rats;

Wistar | Bleomycin

(intratracheal) | 100 mg/kg

(oral) | 20 days | TNF-α, CAT, SOD,

MDA, weight, hydroxyproline, total cell numbers, neutrophils,

macrophages, eosinophil and lymphocytes | (20) |

| Impellizzeri et

al, 2015 | Italy | N | 20 | Male mice;

CD1(ICR) | Bleomycin

(intratracheal) | 10 mg/kg

(oral) | 7 days | Ashcroft score,

total cell numbers, weight, neutrophils, lymphocytes, macrophages,

eosinophil and leucocytes | (21) |

| Park et al,

2010 | Korea | N | 8 | Male rats;

Sprague-Dawley | Paraquat

(intratracheal) | 50 mg/kg

(intraperitoneal) | 14 days | GSH, MDA and

NO | (22) |

| Taslidere et

al, 2014 | Turkey | 3-4 months | 14 | Albino female rats;

Wistar | CCl4

(intraperitoneal) | 25 mg/kg

(intraperitoneal) | 10 days | GSH, MDA and

CAT | (23) |

| Geng et al,

2022 | China | 6-8 weeks | 20 | Female mice;

C57BL/6 | SiO2

(intratracheal) | 100 mg/kg (oral

gavage) | 28 days | TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6

and Col I | (24) |

| Geng et al,

2023 | China | 8 weeks | 10 | Male mice;

C57BL/6 | SiO2

(intratracheal) | 100 mg/kg

(intraperitoneal) | 28 days | α-SMA and Col

I | (25) |

| Hohmann et

al, 2019 | America | >12 months | 14 | Male and female

mice; C57BL/6 | Bleomycin

(intratracheal) | 30 mg/kg

(intraperitoneal) | 21 days | Weight and

hydroxyproline | (26) |

| Wu et al,

2024 | China | 8 weeks | 10 | Female rats;

Wistar | Bleomycin

(intratracheal) | 75 mg/kg

(oral) | 28 days | α-SMA, Col I,

hydroxyproline and weight | (27) |

| Liu et al,

2013 | China | 6-8 weeks | 46 | Female mice;

C57BL/6 | Cobalt-60γ

radiation (16 Gy; thoracic irradiation) | 5 mg/kg

(intraperitoneal) | 24 weeks | α-SMA, TNF-α,

TGF-β1, SOD, MDA, total cell numbers, hydroxy proline and Ashcroft

score | (28) |

| Verma et al,

2022 | India | 8-10 weeks | 12 | Female mice;

C57BL/6 | γ radiation (12 Gy)

(thoracic irradiation) | 10 mg/kg

(intramuscularly) | 16 weeks | α-SMA, TNF-α,

IL-1β, IL-6, TGF-β1, MDA, NO, lung index, macrophages, total cell

numbers, Ashcroft score and leucocytes | (29) |

| Boots et al,

2020 | Germany | 10-12 weeks | 23 | Male and female

mice; C57BL/6 | Bleomycin

(pharyngeal administration) | 200 mg/kg

(oral) | 21 days | TNF-α and

weight | (30) |

| Wei et al,

2016 | China | 18 weeks | 40 | Male rats;

Sprague-Dawley | Bleomycin

(intraperitoneal) | 3 mg/kg

(intraperitoneal) | 36 days | Ashcroft score,

hydroxyproline and MDA | (31) |

| Oka et al,

2019 | Nigeria | N | 12 | Female rats;

Wistar | Amiodarone

(intratracheal) | 20 mg/kg

(oral) | 21 days | GSH, CAT, total

cell numbers and macrophages | (32) |

| Qin et al,

2017 | China | 5-6 weeks | 24 | Male rats;

Wistar | X-ray (15Gy)

(pulmonary apex irradiation) | 100 mg/kg

(inhaled) | 4 months | Leucocytes | (33) |

| Ding et al,

2024 | China | 6-8 weeks | 12 | Male mice;

C57BL/6 | PM2:5

(intratracheal) | 50 mg/kg (oral

gavage) | 60 days | TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6,

TGF-β1, Col I, Ashcroft score and lung index | (34) |

| Malayeri et

al, 2016 | Iran | N | 20 | Male rats;

Sprague-Dawley | Bleomycin

(intratracheal) | 50 mg/kg

(intraperitoneal) | 28 days | TNF-α | (35) |

| El-Sayed et

al, 2009 | Egypt | N | 14 | Albino male rats;

N | Paraquat

(intraperitoneal) | 50 mg/kg

(p.o.) | 21 days | GSH, SOD, NO and

TBARS | (36) |

| Fang et al,

2023 | China | 6 weeks | 20 | Male mice;

C57BL/6 | 10 mg/ml OVA and

alum adjuvant (intraperitoneal) OVA (inhaled) | 30 mg/kg

(gavage) | 21 days | TGF-β1, α-SMA,

total cell numbers, neutrophils, lymphocytes, eosinophil and

macrophages | (37) |

| Yao et al,

2023 | China | N | 20 | Rats;

Sprague-Dawley | Silica suspension

(intratracheal) | 2 mg/kg

(intratracheal) | 28 days | TNF-α, IL-1β,

α-SMA, SOD, weight and lung index | (38) |

| Yang et al,

2020 | China | 6-8 weeks | 24 | Male mice;

BALB/c | Cigarette smoke

(inhaled) | 50 mg/kg

(intraperitoneal) | 12 weeks | TNF-α, IL-1β, total

cell numbers, neutrophils and macrophages | (39) |

| Zhang et al,

2024 | China | 6-8 weeks | 12 | Male mice;

C57BL/6 | Bleomycin

(intratracheal) | 50 mg/kg

(intragastric administration) | 3 weeks | Ashcroft score and

hydroxyproline | (40) |

| Toker et al,

2024 | Turkey | N | 16 | Albino male rats;

Wistar | Bleomycin

(intratracheal) | 50 mg/kg

(intraperitoneal) | 21 days | α-SMA | (41) |

Basic characteristics of included

studies

A total of 25 studies were included in the analysis,

performed across 11 countries. Among these, 12 studies were from

China, 2 each from India, Iran and Turkey and 1 each from the

United States, Brazil, Egypt, Germany, Italy, South Korea and

Nigeria. All studies were preclinical controlled trials utilizing

rat models. Of these, 24 studies used quercetin as the sole

intervention, while one study employed a derivative of quercetin.

The experimental animals included male rats (60%), female rats

(24%), mixed sex (8%) and those with unspecified sex (8%). The age

of the animals varied notably, ranging from 6 weeks to >12

months, with 10 studies not reporting the age. The primary outcome

measures included body weight (5 studies), lung index (4 studies),

fibrosis markers (hydroxyproline content in 9 studies, α-SMA in 6

studies and COL I in 4 studies), histopathological scores (Ashcroft

score in 7 studies), inflammatory markers (TNF-α in 11 studies,

IL-1β in 6 studies and IL-6 in 5 studies), inflammatory cell counts

(total cell count in 7 studies, macrophage count in 7 studies,

neutrophil count in 5 studies, lymphocyte count in 4 studies,

eosinophil count in 3 studies and white blood cell count in 3

studies) and oxidative stress markers (MDA levels in 7 studies, GSH

levels in 6 studies, SOD and CAT enzyme activities in 4 studies

each and TBARS in 3 studies).

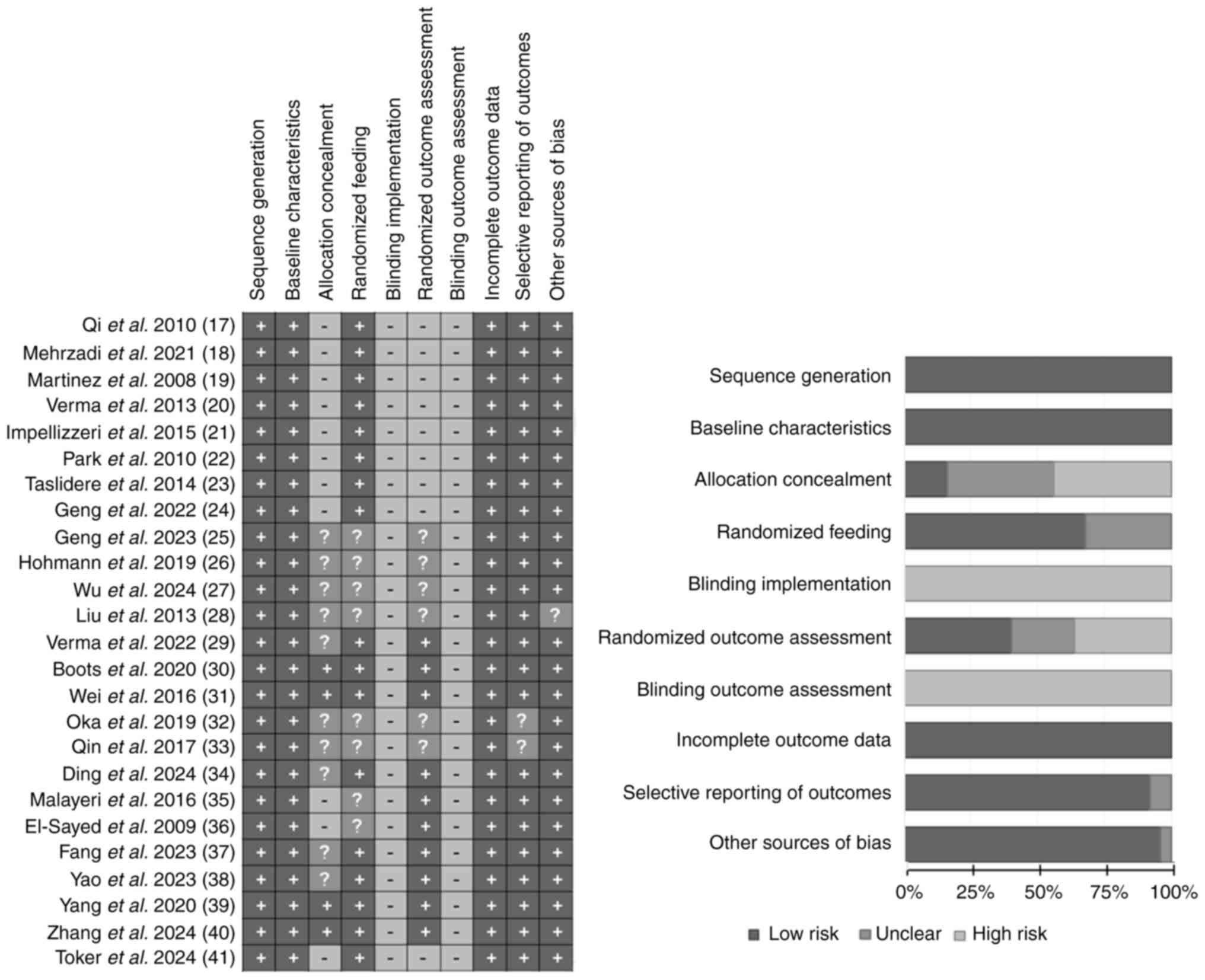

Quality assessment of the studies

Among the 25 studies, the assessment results for

sequence generation, baseline characteristics, incomplete outcome

data, selective outcome reporting and other sources of bias were

generally favorable, with 25, 25, 25, 23 and 24 studies rated as

‘low risk of bias’, respectively. No studies were scored as ‘high

risk of bias’ for random housing. However, the assessments for

blinding and blinding of outcome assessment were poor, with all 25

studies rated as ‘high risk of bias’. Overall, the studies

performed well regarding randomization and outcome data, but there

was notable bias in the implementation of blinding. The specific

findings are summarized in Fig. 2.

Due to the nature of study subjects and interventions, blinding of

both participants and researchers was difficult and thus most of

the studies did not report implementing double blinding.

Research results

The present meta-analysis demonstrated that

quercetin supplementation elicited notable changes across multiple

physiological domains. As summarized in Table II, a significant increase in body

weight was observed in the quercetin group compared with the

control group (n=5; SMD=1.78; 95% CI, 0.72 to 2.84;

I2=73%; P=0.0010). Similarly, lung index values were

significantly reduced following quercetin intervention (n=4;

SMD=-1.55; 95% CI, -3.04 to -0.05; I2=83%; P=0.04).

| Table IIResults of the meta-analysis for each

outcome indicator. |

Table II

Results of the meta-analysis for each

outcome indicator.

| | Heterogeneity test

results | | Meta-analysis

results |

|---|

| Outcome

indicator | I2,

% | P-value | Effect models | SMD | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|

| Weight | 73 | 0.005 | Random | 1.78 | (0.72, 2.84) | 0.001 |

| Lung index | 83 | 0.0005 | Random | -1.55 | (-3.04, -0.05) | 0.040 |

| TBARS | 9 | 0.330 | Fixed | -1.15 | (-1.69, -0.61) | <0.0001 |

| Ashcroft score | 73 | 0.001 | Random | -2.20 | (-3.21, -1.18) | <0.0001 |

| Hydroxyproline | 75 | <0.0001 | Random | -2.05 | (-2.91, -1.18) | <0.00001 |

| Col I | 0 | 0.710 | Fixed | -1.77 | (-2.85, -0.69) | 0.001 |

| α-SMA | 53 | 0.060 | Random | -2.25 | (-3.17, -1.32) | <0.00001 |

| TNF-α | 80 | <0.0001 | Random | -1.73 | (-2.65, -0.82) | 0.0002 |

| IL-1β | 0 | 0.410 | Fixed | -2.77 | (-3.55, -2.00) | <0.00001 |

| IL-6 | 0 | 0.410 | Fixed | -1.45 | (-2.07, -0.83) | <0.00001 |

| TGF-β1 | 0 | 0.980 | Fixed | -2.68 | (-3.58, -1.78) | <0.00001 |

| GSH | 85 | <0.00001 | Random | 1.93 | (0.52, 3.34) | 0.007 |

| CAT | 41 | 0.170 | Fixed | 1.99 | (1.30, 2.68) | <0.00001 |

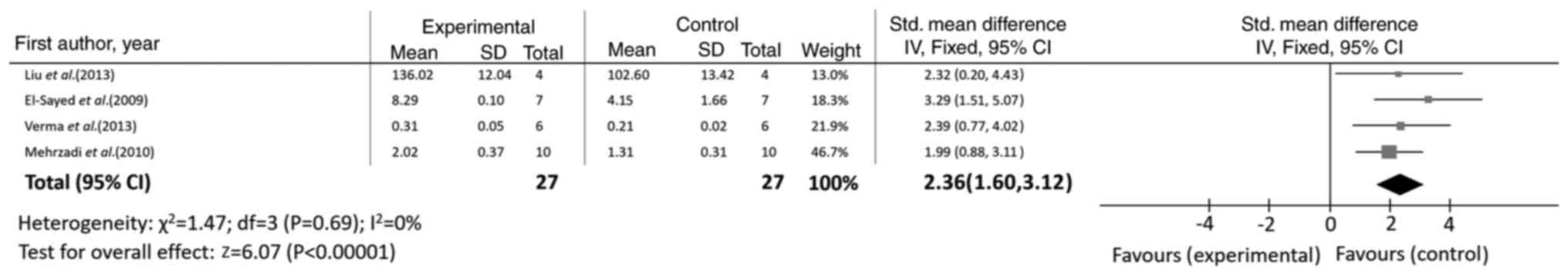

| SOD | 0 | 0.690 | Fixed | 2.36 | (1.60, 3.12) | <0.00001 |

| MDA | 58 | 0.030 | Random | -2.56 | (-3.46, -1.66) | <0.00001 |

| NO | 53 | 0.090 | Random | -2.42 | (-3.63, -1.21) | <0.0001 |

| Neutrophils | 89 | <0.00001 | Random | -3.73 | (-6.50, -0.95) | 0.009 |

| Lymphocytes | 80 | 0.002 | Random | -0.74 | (-2.20, 0.73) | 0.320 |

| Macrophages | 82 | <0.00001 | Random | -1.85 | (-3.36, -0.35) | 0.020 |

| Eosinophil | 79 | 0.009 | Random | -1.66 | (-3.25, -0.06) | 0.040 |

| Total cell

numbers | 37 | 0.150 | Fixed | -1.32 | (-1.87, -0.78) | <0.00001 |

| Leucocytes | 77 | 0.010 | Random | -2.33 | (-3.89, -0.77) | 0.003 |

Effect of quercetin on

fibrosis-related markers

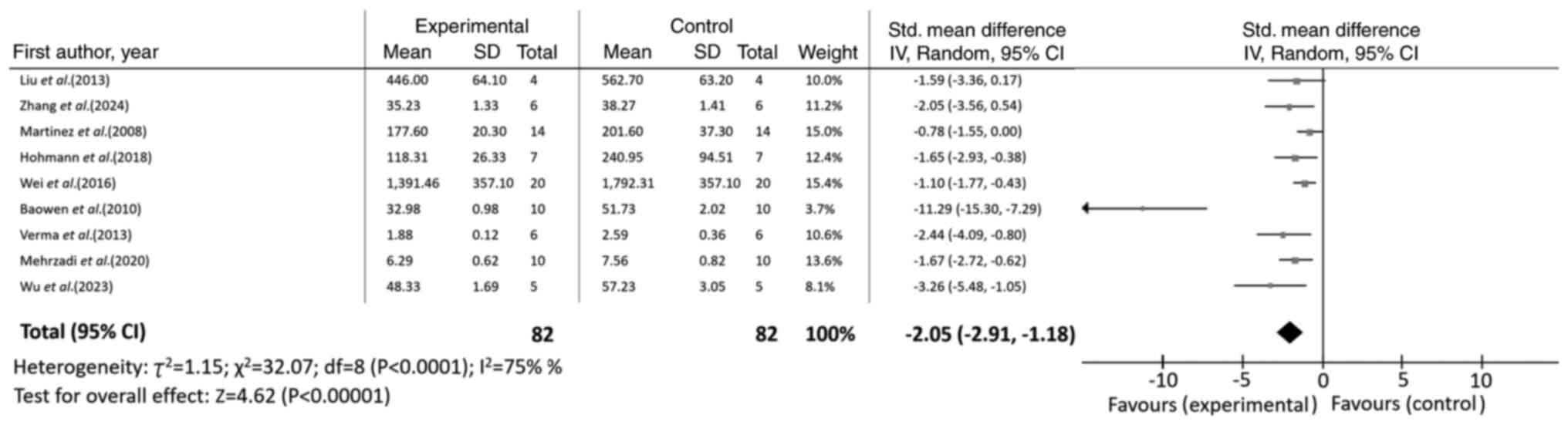

Regarding fibrosis-related markers, quercetin

administration resulted in marked improvements. Notably,

hydroxyproline levels were significantly decreased (n=9; SMD=-2.05;

95% CI, -2.91 to -1.18; I2=75%; P<0.00001), as shown

in Fig 3. Consistently, the

Ashcroft score was also significantly lower in the quercetin group

(n=7; SMD=-2.20; 95% CI, -3.21 to -1.18; I2=73%;

P<0.0001). Furthermore, expression levels of Col I (n=4;

SMD=-1.77; 95% CI, -2.85 to -0.69; I2=0%; P=0.001) and

α-SMA (n=6; SMD=-2.25; 95% CI, -3.17 to -1.32; I2=53%;

P<0.00001) were significantly suppressed, further supporting the

anti-fibrotic effect of quercetin (Table II).

Effect of quercetin on inflammatory

markers

Analysis of inflammatory parameters revealed notable

modulation by quercetin, which was evaluated through

pro-inflammatory cytokines and inflammatory cells. The quercetin

group exhibited significantly lower levels of key pro-inflammatory

cytokines, including TNF-α (n=11; SMD=-1.73; 95% CI, -2.65 to

-0.82; I2=80%; P=0.0002), IL-1β (n=6; SMD=-2.77; 95% CI,

-3.55 to -2.00; I2=0%; P<0.00001, IL-6 (n=5;

SMD=-1.45; 95% CI, -2.07 to -0.83; I2=0%; P<0.00001)

and TGF-β1 (n=4; SMD=-2.68; 95% CI, -3.58 to -1.78;

I2=0%; P<0.00001) (Table II).

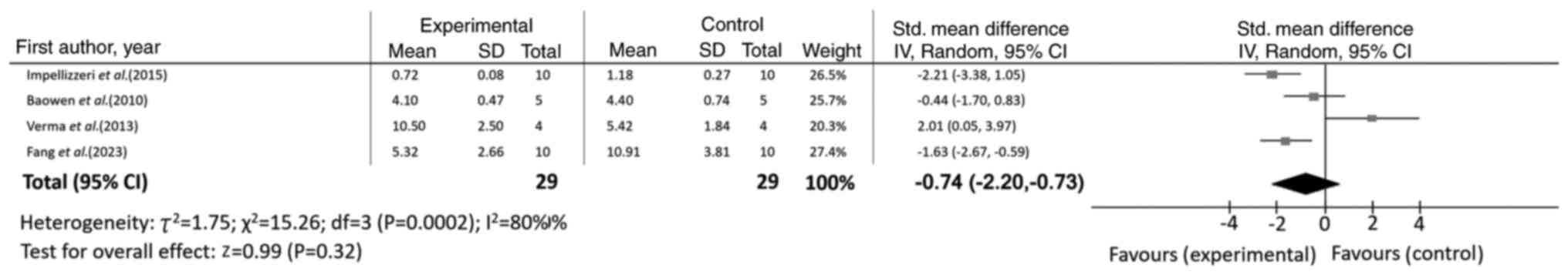

With regards to inflammatory cell infiltration,

quercetin supplementation significantly reduced counts of

neutrophils (n=5; SMD=-3.73; 95% CI, -6.50 to -0.95;

I2=89%; P=0.009), macrophages (n=7; SMD=-1.85; 95% CI,

-3.36 to -0.35; I2=82%; P=0.02), eosinophils (n=3;

SMD=-1.66; 95% CI, -3.25 to -0.06; I2=79%; P=0.04),

leukocytes (n=3; SMD=-2.33; 95% CI, -3.89 to -0.77;

I2=77%; P=0.003) and total cells (n=7; SMD=-1.32; 95%

CI, -1.87 to -0.78; I2=37%; P<0.00001) (Table II). However, no significant effect

was observed on lymphocyte count (n=4; SMD=-0.74; 95% CI, -2.20 to

0.73; I2=80%; P=0.32), as illustrated in Fig. 4.

Effect of quercetin on oxidative

stress markers

Quercetin supplementation significantly alleviated

oxidative stress, as evidenced by the increased activities of

antioxidant enzymes. Specifically, SOD activity was significantly

enhanced (n=4; SMD=2.36; 95% CI, 1.60 to 3.12; I2=0%;

P<0.00001), as shown in Fig. 5.

CAT (n=4; SMD=1.99; 95% CI, 1.30 to 2.68; I2=41%;

P<0.00001) activity and GSH levels were also significantly

increased (n=6; SMD=1.93; 95% CI, 0.52 to 3.34; I2=85%;

P=0.007) (Table II).

Conversely, quercetin significantly reduced the

levels of biomarkers of oxidative damage, including MDA (n=7;

SMD=-2.56; 95% CI, -3.46 to -1.66; I2=58%;

P<0.00001), NO (n=4; SMD=-2.42; 95% CI, -3.63 to -1.21;

I2=53%; P<0.0001) and TBARS (n=3; SMD=-1.15; 95% CI,

-1.69 to -0.61; I2=9%; P<0.0001) (Table II).

Meta-regression analysis for sources

of heterogeneity

To explore potential sources of heterogeneity across

the included studies, a meta-regression analysis was performed

using four covariates: i) Animal model type (‘Model’); ii) fibrosis

induction method (‘Pfinductiod’); iii) quercetin dosage

(‘Quercetindose’); and i) intervention duration (‘Duration’).

The results indicated that quercetin dosage and

intervention duration were the most influential factors

contributing to heterogeneity across multiple outcome measures

(Table III). Specifically,

higher quercetin dosage was significantly associated with increased

levels of the antioxidant marker GSH [unstandardized regression

coefficients (coef.)=0.107; P=0.035] and lymphocyte count

(coef.=0.040; P=0.035), decreased total inflammatory cell count

(coef.=-0.025; P=0.027) and leukocyte cell count (coef.=-0.030;

P=0.002). A longer intervention duration was significantly

associated with increased CAT activity (coef.=0.101; P=0.044) and

elevated GSH levels (coef.=0.228; P=0.017).

| Table IIIMeta-regression analysis of potential

moderators for various outcome measures. |

Table III

Meta-regression analysis of potential

moderators for various outcome measures.

| Outcome

measure | Moderator | Coefficient | SE | z-value | P-value | 95% CI |

|---|

| α-SMA | Model | -0.171 | 0.342 | -0.50 | 0.618 | -0.841 to

0.500 |

| | Pfinductiod | -0.293 | 0.273 | -1.07 | 0.284 | -0.829 to

0.243 |

| | Quercetindose | -0.009 | 0.020 | -0.46 | 0.642 | -0.048 to

0.030 |

| | Duration | 0.018 | 0.012 | 1.54 | 0.124 | -0.005 to

0.042 |

| CAT | Model | -1.389 | 0.799 | -1.74 | 0.082 | -2.956 to

0.178 |

| | Pfinductiod | -0.082 | 0.284 | -0.29 | 0.773 | -0.638 to

0.475 |

| | Quercetindose | -0.007 | 0.018 | -0.37 | 0.709 | -0.042 to

0.029 |

| | Duration | 0.101 | 0.050 | 2.02 | 0.044a | 0.003 to 0.198 |

| Col I | Model | -0.442 | 0.355 | -1.24 | 0.214 | -1.138 to

0.255 |

| | Pfinductiod | -0.302 | 0.366 | -0.83 | 0.409 | -1.020 to

0.415 |

| | Quercetindose | -0.011 | 0.034 | -0.33 | 0.739 | -0.077 to

0.055 |

| | Duration | -0.022 | 0.044 | -0.51 | 0.612 | -0.108 to

0.063 |

| GSH | Model | 0.479 | 0.455 | 1.05 | 0.292 | -0.413 to

1.371 |

| | Pfinductiod | -0.030 | 0.547 | -0.05 | 0.957 | -1.102 to

1.042 |

| | Quercetindose | 0.107 | 0.051 | 2.11 | 0.035a | 0.008 to 0.207 |

| | Duration | 0.228 | 0.096 | 2.38 | 0.017a | 0.040 to 0.416 |

| Hydroxyproline | Model | 0.475 | 0.507 | 0.94 | 0.349 | -0.519 to

1.468 |

| | Pfinductiod | 0.475 | 1.405 | 0.34 | 0.735 | -2.279 to

3.229 |

| | Quercetindose | 0.009 | 0.029 | 0.33 | 0.744 | -0.047 to

0.066 |

| | Duration | 0.005 | 0.019 | 0.26 | 0.798 | -0.033 to

0.043 |

| IL-1β | Model | -0.204 | 0.212 | -0.96 | 0.336 | -0.621 to

0.212 |

| | Pfinductiod | -0.119 | 0.232 | -0.51 | 0.610 | -0.574 to

0.336 |

| | Quercetindose | -0.006 | 0.016 | -0.39 | 0.695 | -0.039 to

0.026 |

| | Duration | -0.018 | 0.015 | -1.20 | 0.230 | -0.046 to

0.011 |

| IL-6 | Model | -0.153 | 0.160 | -0.96 | 0.338 | -0.466 to

0.160 |

| | Pfinductiod | -0.094 | 0.194 | -0.48 | 0.629 | -0.474 to

0.287 |

| | Quercetindose | -0.019 | 0.014 | -1.31 | 0.190 | -0.046 to

0.009 |

| | Duration | -0.006 | 0.010 | -0.58 | 0.561 | -0.025 to

0.013 |

| MDA | Model | 0.468 | 0.160 | 2.93 | 0.003a | 0.155 to 0.782 |

| | Pfinductiod | 0.164 | 0.354 | 0.46 | 0.643 | -0.529 to

0.858 |

| | Quercetindose | -0.007 | 0.015 | -0.45 | 0.653 | -0.037 to

0.023 |

| | Duration | 0.012 | 0.008 | 1.55 | 0.121 | -0.003 to

0.027 |

| NO | Model | -0.386 | 0.198 | -1.95 | 0.051 | -0.775 to

0.002 |

| | Pfinductiod | -0.586 | 0.546 | -1.07 | 0.284 | -1.656 to

0.485 |

| | Quercetindose | -0.016 | 0.053 | -0.31 | 0.760 | -0.119 to

0.087 |

| | Duration | 0.008 | 0.023 | 0.33 | 0.740 | -0.037 to

0.053 |

| Ashcroft score | Model | 0.759 | 0.507 | 1.50 | 0.135 | -0.236 to

1.753 |

| | Pfinductiod | 0.565 | 0.650 | 0.87 | 0.385 | -0.709 to

1.838 |

| | Quercetindose | -0.059 | 0.038 | -1.53 | 0.125 | -0.133 to

0.016 |

| | Duration | 0.015 | 0.017 | 0.88 | 0.379 | -0.019 to

0.049 |

| SOD | Model | 0.210 | 0.163 | 1.29 | 0.198 | -0.110 to

0.530 |

| | Pfinductiod | 0.378 | 0.311 | 1.22 | 0.224 | -0.232 to

0.989 |

| | Quercetindose | -0.0003 | 0.014 | -0.02 | 0.984 | -0.027 to

0.027 |

| | Duration | 0.0004 | 0.008 | 0.05 | 0.960 | -0.015 to

0.016 |

| TBARS | Model | -0.005 | 0.194 | -0.02 | 0.981 | -0.385 to

0.376 |

| | Pfinductiod | -0.129 | 0.314 | -0.41 | 0.682 | -0.745 to

0.487 |

| | Quercetindose | -0.044 | 0.027 | -1.59 | 0.112 | -0.097 to

0.010 |

| | Duration | -0.070 | 0.046 | -1.54 | 0.124 | -0.160 to

0.019 |

| TGF-β1 | Model | 0.451 | 0.921 | 0.49 | 0.624 | -1.353 to 2.25 |

| | Pfinductiod | 0.155 | 0.320 | 0.48 | 0.628 | -0.473 to

0.783 |

| | Quercetindose | 0.014 | 0.032 | 0.43 | 0.668 | -0.048 to

0.076 |

| | Duration | -0.004 | 0.008 | -0.48 | 0.631 | -0.020 to

0.012 |

| TNF-α | Model | 0.584 | 0.223 | 2.62 | 0.009 | 0.147 to 1.021 |

| | Pfinductiod | 0.136 | 0.309 | 0.44 | 0.660 | -0.469 to

0.741 |

| | Quercetindose | 0.015 | 0.008 | 1.83 | 0.067 | -0.001 to

0.031 |

| | Duration | 0.013 | 0.012 | 1.05 | 0.295 | -0.011 to

0.036 |

| Leukocyte | Model | 0.953 | 0.398 | 2.39 | 0.017 | 0.172 to 1.734 |

| | Pfinductiod | -0.653 | 1.114 | -0.59 | 0.558 | -2.837 to

1.531 |

| | Quercetindose | -0.030 | 0.010 | -3.07 | 0.002 | -0.049 to

-0.011 |

| | Duration | -0.013 | 0.020 | -0.67 | 0.501 | -0.052 to

0.025 |

| Lung index | Model | 0.615 | 0.444 | 1.38 | 0.166 | -0.256 to

1.485 |

| | Pfinductiod | 0.581 | 0.726 | 0.80 | 0.423 | -0.842 to

2.004 |

| | Quercetindose | 0.052 | 0.043 | 1.22 | 0.223 | -0.032 to

0.137 |

| | Duration | 0.027 | 0.031 | 0.89 | 0.375 | -0.033 to

0.088 |

| Macrophages | Model | -0.712 | 0.634 | -1.12 | 0.261 | -1.956 to

0.531 |

| | Pfinductiod | -0.947 | 0.312 | -3.03 | 0.002 | -1.559 to

-0.335 |

| | Quercetindose | 0.039 | 0.035 | 1.11 | 0.266 | -0.030 to

0.109 |

| | Duration | -0.009 | 0.033 | -0.26 | 0.796 | -0.074 to

0.057 |

| Lymphocytes | Model | -0.674 | 0.570 | -1.18 | 0.237 | -1.791 to

0.444 |

| | Pfinductiod | -0.290 | 0.511 | -0.57 | 0.571 | -1.291 to

0.712 |

| | Quercetindose | 0.040 | 0.019 | 2.11 | 0.035 | 0.003 to 0.077 |

| | Duration | 0.096 | 0.140 | 0.68 | 0.495 | -0.179 to

0.371 |

| Eosinophils | Model | -0.790 | 0.636 | -1.24 | 0.214 | -2.038 to

0.457 |

| | Pfinductiod | -0.102 | 0.525 | -0.19 | 0.846 | -1.132 to

0.927 |

| | Quercetindose | 0.033 | 0.010 | 3.17 | 0.002 | 0.013 to 0.053 |

| | Duration | 0.140 | 0.142 | 0.99 | 0.324 | -0.139 to

0.419 |

| Body weight | Model | -0.350 | 0.444 | -0.79 | 0.430 | -1.220 to

0.520 |

| | Pfinductiod | 2.915 | 1.076 | 2.71 | 0.007 | 0.806 to 5.024 |

| | Quercetindose | -0.023 | 0.012 | -2.01 | 0.044 | -0.046 to

-0.001 |

| | Duration | 0.018 | 0.092 | 0.20 | 0.843 | -0.162 to

0.198 |

| Total cell

count | Model | -0.032 | 0.269 | -0.12 | 0.905 | -0.560 to

0.496 |

| | Pfinductiod | -0.280 | 0.197 | -1.42 | 0.156 | -0.667 to

0.106 |

| | Quercetindose | -0.025 | 0.011 | -2.22 | 0.027a | -0.047 to

-0.003 |

| | Duration | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.91 | 0.362 | -0.008 to

0.021 |

| Neutrophils | Model | -0.510 | 0.940 | -0.54 | 0.587 | -2.353 to

1.332 |

| | Pfinductiod | 0.234 | 0.680 | 0.34 | 0.731 | -1.098 to

1.566 |

| | Quercetindose | -0.032 | 0.053 | -0.61 | 0.543 | -0.136 to

0.072 |

| | Duration | 0.031 | 0.068 | 0.46 | 0.645 | -0.102 to

0.165 |

The choice of fibrosis induction method emerged as a

significant source of heterogeneity for macrophage infiltration

(coef.=-0.947; P=0.002) and changes in body weight (coef.=2.915;

P=0.007). Conversely, the type of animal model was significantly

associated with variations in MDA (coef.=0.468; P=0.003) and TNF-α

levels (coef.=0.584; P=0.009).

For numerous outcomes, including inflammatory

cytokines (IL-1β and IL-6) and fibrosis markers (COL I and α-SMA),

none of the examined covariates demonstrated a significant

moderating effect (all P>0.05), suggesting that other unmeasured

factors likely contributed to the observed heterogeneity.

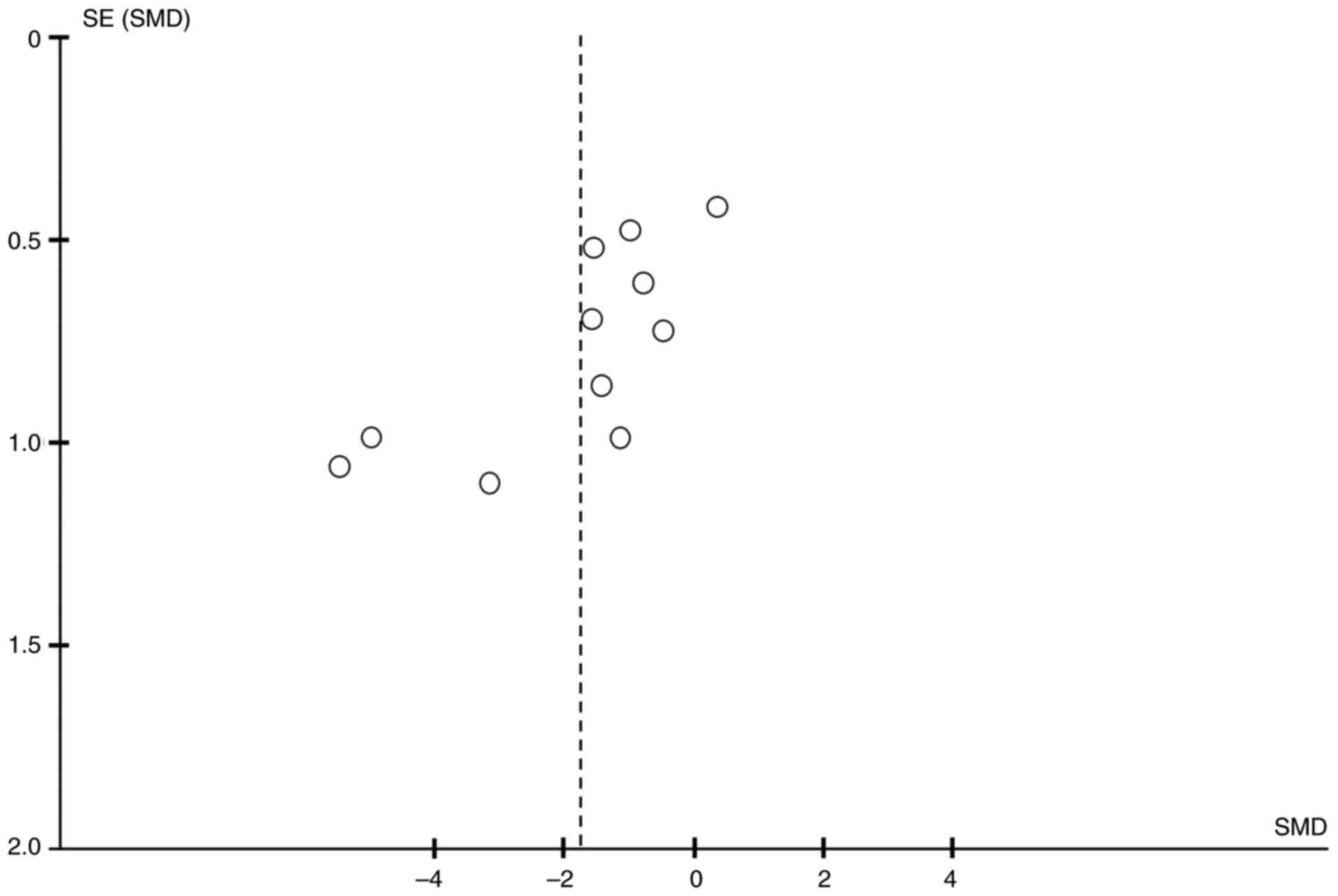

Publication bias

The potential for publication bias was

systematically evaluated for all outcomes using both Egger's linear

regression test and Begg's rank correlation test (Table IV). The visual inspection of

funnel plots indicated general symmetry for numerous outcomes (for

example, TNF-α; Fig. 6). In

accordance with methodological recommendations (including the

Cochrane Handbook), statistical tests for funnel plot asymmetry,

such as Egger's test, are only recommended when a meta-analysis

contains ≥10 studies. Among all outcomes in the present analysis,

TNF-α exhibited the largest number of studies (n=11), meeting this

minimum threshold. Therefore, funnel plots and statistical tests

for this outcome were selectively performed and reported to provide

a meaningful assessment. The statistical tests demonstrated that no

significant publication bias was detected for the majority of

outcomes (all P>0.05).

| Table IVResults of the Begg's and Egger's

tests for assessment of potential publication bias. |

Table IV

Results of the Begg's and Egger's

tests for assessment of potential publication bias.

| | | Begg's test | Egger's test |

|---|

| Outcome

measure | n | z-value | P-value | t-value | P-value |

|---|

| Boby weight | 5 | 1.96 | 0.050 | 2.25 | 0.110 |

| Lung index | 4 | -0.68 | 0.497 | -1.84 | 0.207 |

| TBARS | 3 | -0.52 | 0.602 | -2.10 | 0.283 |

| Ashcroft score | 7 | -1.35 | 0.176 | -1.87 | 0.120 |

| Hydroxyproline

content | 9 | -2.50 | 0.012a | -4.60 | 0.002b |

| Col I | 4 | -2.04 | 0.042a | -5.14 | 0.036a |

| α-SMA | 6 | -1.69 | 0.091 | -1.04 | 0.357 |

| TNF-α | 11 | -1.95 | 0.052 | -3.45 | 0.007b |

| IL-1β | 6 | -0.94 | 0.348 | -0.81 | 0.463 |

| IL-6 | 5 | -1.47 | 0.142 | -1.78 | 0.173 |

| TGF-β1 | 4 | 0.68 | 0.497 | 0.20 | 0.860 |

| GSH | 6 | 1.69 | 0.091 | 4.32 | 0.012a |

| CAT | 4 | 1.36 | 0.174 | 1.22 | 0.347 |

| SOD | 4 | 0.68 | 0.497 | 1.18 | 0.359 |

| MDA | 7 | 0.45 | 0.652 | -0.27 | 0.801 |

| NO | 4 | -1.36 | 0.174 | -1.88 | 0.200 |

| Neutrophils | 5 | -1.47 | 0.142 | -1.90 | 0.154 |

| Lymphocytes | 4 | 1.36 | 0.174 | 2.94 | 0.099 |

| Macrophages | 7 | -0.15 | 0.881 | -0.58 | 0.586 |

| Eosinophils | 3 | 0.52 | 0.602 | 0.33 | 0.800 |

| Total cell

count | 7 | -1.35 | 0.176 | -2.20 | 0.079 |

| Leukocyte

count | 3 | -1.57 | 0.117 | -1.08 | 0.475 |

However, significant publication bias was identified

for four specific outcomes. Egger's test yielded statistically

significant results for hydroxyproline (t=-4.60; P=0.002), Col I

(t=-5.14; P=0.036), TNF-α (t=-3.45; P=0.007) and GSH (t=4.32;

P=0.012). The findings from Begg's test further supported the

presence of a significant bias for hydroxyproline (z=-2.50;

P=0.012) and Col I (z=-2.04; P=0.042), while the result for TNF-α

was of borderline statistical significance (P=0.052), and no

significant bias was detected for GSH (P=0.091) using this

method.

Discussion

The present meta-analysis evaluated the therapeutic

potential of quercetin in experimental models of PF to explore

potential sources of heterogeneity in its efficacy. The present

comprehensive analysis indicated that quercetin intervention may

exert regulatory effects across multiple physiological processes,

including body weight recovery, attenuation of fibrosis

progression, suppression of inflammatory responses and reduction of

oxidative stress. These findings are consistent with previous

experimental studies (42-44).

Previous studies have suggested that quercetin may

inhibit collagen synthesis through modulation of the TGF-β1/Smad

signaling pathway (45,46), while also promoting collagen

degradation by regulating the MMP/TIMP balance; thereby

demonstrating anti-fibrotic effects. This is reflected in reduced

levels of hydroxyproline, Col I, α-SMA and lower Ashcroft scores.

However, meta-regression analysis indicated that the type of animal

model may be a notable source of heterogeneity in fibrosis markers,

suggesting that the genetic backgrounds of different animal strains

may influence treatment responsiveness.

With regards to anti-inflammatory mechanisms, the

present study observed that quercetin may reduce the levels of

pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 and

TGF-β1, as suggested in the literature through inhibition of the

NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways (47-49).

Notably, the method of fibrosis induction markedly influenced the

degree of inflammatory cell infiltration, indicating that different

induction methods (for example, bleomycin vs. silica) may activate

distinct inflammatory pathways, thereby perhaps contributing to

variability in treatment outcomes.

In relation to its antioxidant effects, quercetin

may enhance the activities of SOD, CAT and GSH through activation

of the nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2

(Nrf2)/Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1/antioxidant response

element pathway (50,51). Meta-regression analysis revealed a

positive association between quercetin dosage and GSH levels and

intervention duration was also notably associated with CAT activity

and GSH, suggesting that its antioxidant effects may be dose- and

time-dependent.

Interactions among experimental design parameters

add complexity to the assessment of efficacy. The present study

found that both animal model selection and induction method jointly

influence treatment outcomes. For example, the present data

indicate that different induction methods may produce markedly

distinct pathological phenotypes across animal strains.

Furthermore, we hypothesize that there may be an interaction

between quercetin dosage and intervention duration, suggesting that

long-term high-dose treatment could yield synergistic effects,

although this hypothesis warrants further validation.

It should be noted that the high heterogeneity

observed in the present study may affect the interpretation of

results. Although several indicators, including hydroxyproline,

lung index, TNF-α and neutrophil count, exhibited high

heterogeneity (I2>75%), this variation largely

reflects methodological diversity across studies rather than

fundamental differences in treatment effects. Importantly,

meta-regression analysis demonstrated the beneficial therapeutic

effect of quercetin across all studies, with heterogeneity

primarily influencing the magnitude rather than the direction of

the effect.

Notably, quercetin did not demonstrate a notable

effect on lymphocyte count, contrasting with its pronounced effects

on innate immune cells. This may indicate differential regulatory

activity on innate compared with adaptive immune responses. For

other outcomes with high heterogeneity but statistical

significance, the results suggested context-dependent

variability.

Moreover, for certain indicators (for example,

IL-1β, IL-6, Col I or α-SMA), none of the covariates examined

showed notable influence, indicating that other unmeasured sources

of heterogeneity, such as animal age, sex differences or analytical

method variations, may be present.

The present meta-analysis provided a comprehensive

and quantitative summary of the current preclinical evidence

regarding the therapeutic effects of quercetin in experimental PF.

One of the primary strengths is the integration of data from 25

independent studies, which enhances the statistical power and

allows for a more robust estimation of treatment effects across

multiple outcome domains, including fibrotic, inflammatory and

oxidative stress parameters. The application of random-effects

meta-analysis and meta-regression analysis further strengthens the

present study by accounting for between-study heterogeneity and

exploring the influence of key experimental variables, such as

dosage, duration, animal model and induction method. This approach

not only increases the reliability of the findings but also helps

identify subtle and consistent treatment effects that may not be

apparent in individual studies. Moreover, the present study offers

novel insights into the context-dependent efficacy of quercetin and

highlights potential sources of heterogeneity, thereby contributing

to the optimization of future preclinical research design.

Several limitations should be considered when

interpreting the present results. First, the inclusion of studies

with varying methodological quality, particularly in areas such as

randomization and blinding, a common issue in animal studies, may

introduce bias and affect the validity of pooled effect estimates.

Second, the presence of notable heterogeneity, although partially

explained by meta-regression, remains a concern, as unmeasured

factors such as animal age, sex and specific analytical protocols

may contribute to variability. Third, the reliance on data

extracted from figures in certain studies, despite efforts to

obtain original datasets, may have introduced inaccuracies in

measurement. Finally, all included studies were conducted in animal

models, which inherently limits the direct translatability of the

findings to human patients. These limitations, however, are

reflective of broader challenges in preclinical meta-research

rather than specific flaws in the current methodology.

The present meta-analysis indicated that quercetin

administration was associated with notable improvements in

fibrotic, inflammatory and oxidative stress parameters, potentially

through the modulation of key pathways such as TGF-β1/Smad, NF-κB

and Nrf2 signaling.

However, these findings must be interpreted with

caution due to the inherent limitations of the included preclinical

studies. The notable methodological heterogeneity, variability in

experimental design and lack of clinical validation, all of which

are common in animal research, undermine the robustness of the

results and render their translational relevance to human disease

uncertain. Consequently, the implications of the present analysis

should be considered hypothesis-generating rather than

definitive.

To strengthen the evidence, future investigations

should prioritize: i) Standardizing experimental protocols to

minimize heterogeneity; ii) performing rigorous dose-response and

time-course studies; iii) validating these findings across a

broader range of PF models; and iv) enhancing data transparency and

reproducibility.

In summary, while the present meta-analysis

highlights the promising therapeutic potential of quercetin and

provides a rationale for further mechanistic investigation, its

ultimate clinical value can only be established through

well-designed future clinical trials.

Supplementary Material

Search strategy for PubMed.

Search strategy for Cochrane

Library.

Search strategy for Embase.

Search strategy for Ovid.

Search strategy for Web of

Science.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported by funding from

Guangzhou Municipal Science and Technology Project on Traditional

Chinese Medicine and Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western

Medicine (grant no. 20252A010010).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

LHC wrote the manuscript, conceived the present

study, collected the data and analyzed the data. LC conceived the

present study, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. CML

designed the present study and reviewed the manuscript. LHC and CML

confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and

approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Yang Y, Lv M, Xu Q, Wang X and Fang Z:

Extracellular vesicles in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis:

Pathogenesis, biomarkers and innovative therapeutic strategies. Int

J Nanomedicine. 19:12593–12614. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Richeldi L, Collard HR and Jones MG:

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Lancet. 389:1941–1952.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Lederer DJ and Martinez FJ: Idiopathic

pulmonary fibrosis. New Engl J Med. 378:1811–1823. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Kou M, Jiao Y, Li Z, Wei B, Li Y, Cai Y

and Wei W: Real-world safety and effectiveness of pirfenidone and

nintedanib in the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: A

systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Pharmacol.

80:1445–1460. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Chagas MDSS, Behrens MD, Moragas-Tellis

CJ, Penedo GXM, Silva AR and Goncalves-de-Albuquerque CF: Flavonols

and flavones as Potential anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and

antibacterial compounds. Oxid Med Cell Longev.

2022(9966750)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Rajesh RU and Sangeetha D: Therapeutic

potentials and targeting strategies of quercetin on cancer cells:

Challenges and future prospects. Phytomedicine.

133(155902)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Godoy MCX, Monteiro GA, Moraes BHD, Macedo

JA, Goncalves GMS and Gambero A: Addition of polyphenols to drugs:

The potential of controlling ‘Inflammaging’ and fibrosis in human

senescent lung fibroblasts in vitro. Int J Mol Sci.

25(7163)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Reyes-Jimenez E, Ramirez-Hernandez AA,

Santos-Alvarez JC, Velázquez-Enríquez JM, González-García K,

Carrasco-Torres G, Villa-Treviño S, Baltiérrez-Hoyos R and

Vásquez-Garzón VR: Coadministration of 3'5-dimaleamylbenzoic acid

and quercetin decrease pulmonary fibrosis in a systemic sclerosis

model. Int Immunopharmacol. 122(110664)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Wiggins Z, Chioma OS, Drake WP and

Langford M: The effect of quercetin on human lung fibroblasts and

regulation of collagen production. Am J Resp Crit Care.

(207)2023.

|

|

10

|

Andres S, Pevny S, Ziegenhagen R, Bakhiya

N, Schäfer B, Hirsch-Ernst KI and Lampen A: Safety aspects of the

use of quercetin as a dietary supplement. Mol Nutr Food Res.

(62)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar : doi:

10.1002/mnfr.201700447.

|

|

11

|

Liu X, Liang Q, Qin Y, Chen Z and Yue R:

Advances and perspectives on the Anti-fibrotic mechanisms of the

quercetin. Am J Chin Med. 53:1411–1440. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Sellares J and Rojas M: Quercetin in

idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: Another brick in the senolytic wall.

Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 60:3–4. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Amir-Behghadami M and Janati A:

Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes and Study (PICOS)

design as a framework to formulate eligibility criteria in

systematic reviews. Emerg Med J. 37(387)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Ashcroft T, Simpson JM and Timbrell V:

Simple method of estimating severity of pulmonary fibrosis on a

numerical scale. J Clin Pathol. 41:467–470. 1988.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron

I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan

SE, et al: The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for

reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 372(n71)2021.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Hooijmans CR, Rovers MM, de Vries RBM,

Leenaars M, Ritskes-Hoitinga M and Langendam MW: SYRCLE's risk of

bias tool for animal studies. BMC Med Res Methodol.

14(43)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Baowen Q, Yulin Z, Xin W, Wenjing X, Hao

Z, Zhizhi C, Xingmei D, Xia Z, Yuquan W and Lijuan C: A further

investigation concerning correlation between anti-fibrotic effect

of liposomal quercetin and inflammatory cytokines in pulmonary

fibrosis. Eur J Pharmacol. 642:134–139. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Mehrzadi S, Hosseini P, Mehrabani M,

Siahpoosh A, Goudarzi M, Khalili H and Malayeri A: Attenuation of

Bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in wistar rats by combination

treatment of two natural phenolic compounds: Quercetin and Gallic

acid. Nutr Cancer. 73:2039–2049. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Martinez JA, Ramos SG, Meirelles MS,

Verceze AV, Arantes MR and Vannucchi H: Effects of quercetin on

Bleomycin-induced lung injury: A preliminary study. J Bras Pneumol.

34:445–452. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Kushwah L, Verma R, Gohel D, Patel M,

Marvania T and Balakrishnan S: Evaluating the ameliorative

potential of quercetin against the Bleomycin-induced pulmonary

fibrosis in wistar rats. Pulm Med. 2013:280–289. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Impellizzeri D, Talero E, Siracusa R,

Alcaide A, Cordaro M, Maria Zubelia J, Bruschetta G, Crupi R,

Esposito E, Cuzzocrea S and Motilva V: Protective effect of

polyphenols in an inflammatory process associated with experimental

pulmonary fibrosis in mice. Brit J Nutr. 114:853–865.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Park HK, Kim SJ, Kwon DY, Park JH and Kim

YC: Protective effect of quercetin against paraquat-induced lung

injury in rats. Life Sci. 87:181–186. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Taslidere E, Esrefoglu M, Elbe H, Cetin A

and Ates B: Protective effects of melatonin and quercetin on

experimental lung injury induced by carbon tetrachloride in rats.

Exp Lung Res. 40:59–65. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Geng F, Xu M, Zhao L, Zhang H, Li J, Jin

F, Li Y, Li T, Yang X, Li S, et al: Quercetin alleviates pulmonary

fibrosis in mice exposed to silica by inhibiting macrophage

senescence. Front Pharmacol. 13(912029)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Geng F, Zhao L, Cai Y, Zhao Y, Jin F, Li

Y, Li T, Yang X, Li S, Gao X, et al: Quercetin alleviates pulmonary

fibrosis in silicotic mice by inhibiting macrophage transition and

TGF-β-Smad2/3 pathway. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 45:3087–3101.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Hohmann MS, Habiel DM, Coelho AL, Verri

JWA and Hogaboam CM: Quercetin enhances ligand-induced apoptosis in

senescent idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis fibroblasts and reduces

lung fibrosis in vivo. Am J Resp Cell Mol. 60:28–40.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Wu W, Wu X, Qiu L, Wan R, Zhu X, Chen S,

Yang X, Liu X and Wu J: Quercetin influences intestinal

dysbacteriosis and delays alveolar epithelial cell senescence by

regulating PTEN/PI3K/AKT signaling in pulmonary fibrosis. Naunyn

Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 397:4809–4822. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Liu H, Xue J, Li X, Ao R and Lu Y:

Quercetin liposomes protect against Radiation-induced pulmonary

injury in a murine model. Oncol Lett. 6:453–459. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Verma S, Dutta A, Dahiya A and Kalra N:

Quercetin-3-Rutinoside alleviates radiation-induced lung

inflammation and fibrosis via regulation of NF-κB/TGF-β1 signaling.

Phytomedicine. 99(154004)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Boots AW, Veith C, Albrecht C, Bartholome

R, Drittij MJ, Claessen SMH, Bast A, Rosenbruch M, Jonkers L, van

Schooten FJ and Schins RPF: The dietary antioxidant quercetin

reduces hallmarks of bleomycin-induced lung fibrogenesis in mice.

BMC Pulm Med. 20:112–116. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Wei QF, Wang XH, Zhang XY, Song LJ, Wang

YM, Wang Q, Lv F and Li XF: Therapeutic effects of quercetin on

bleomycin induced pulmonary fibrosis in rats. Int J Clin Exp Med.

9:5161–5167. 2016.

|

|

32

|

Oka VO, Okon UE and Osim EE: Pulmonary

responses following quercetin administration in rats after

intratracheal instillation of amiodarone. Niger J Physiol Sci.

34:63–68. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Qin M, Chen W, Cui J, Li W, Liu D and

Zhang W: Protective efficacy of inhaled quercetin for radiation

pneumonitis. Exp Ther Med. 14:5773–5778. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Ding S, Jiang J and Li Y: Quercetin

alleviates PM2.5-induced chronic lung injury in mice by targeting

ferroptosis. PeerJ. 12(e16703)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Malayeri AR, Hemmati AA, Arzi A, Rezaie A,

Ghafurian-Boroojerdnia M and Khalili HR: A comparison of the

effects of quercetin hydrate with those of vitamin E on the levels

of IL-13, PDGF, TNF-α, and INF-γ in bleomycin-induced pulmonary

fibrosis in rats. Jundishapur J Nat Ph. 11(e27705)2016.

|

|

36

|

El-Sayed NS and Rizk SM: The protective

effect of quercetin, green tea or malt extracts against

experimentally-induced lung fibrosis in rats. African J Pharm

Pharmacol. 3:191–201. 2009.

|

|

37

|

Fang Y, Jin W, Guo Z and Hao J: Quercetin

alleviates Asthma-induced airway inflammation and remodeling

through downregulating periostin via blocking TGF-β1/smad pathway.

Pharmacology. 108:432–443. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Yao J, Li Y, Meng F, Shen W and Wen H:

Enhancement of suppression oxidative stress and inflammation of

quercetin by Nano-decoration for ameliorating silica-induced

pulmonary fibrosis. Environ Toxicol. 38:1494–1508. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Yang T, Wang H, Li Y, Zeng Z, Shen Y, Wan

C, Wu Y, Dong J, Chen L and Wen F: Serotonin receptors 5-HTR2A and

5-HTR2B are involved in cigarette smoke-induced airway

inflammation, mucus hypersecretion and airway remodeling in mice.

Int Immunopharmacol. 81(106036)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Zhang H, Hua H, Liu J, Wang C, Zhu C, Xia

Q, Jiang W, Cheng X, Hu X and Zhang Y: Integrative analysis of the

efficacy and pharmacological mechanism of Xuefu Zhuyu decoction in

idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis via evidence-based medicine,

bioinformatics, and experimental verification. Heliyon.

10(e38122)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Toker C, Kuyucu Y, Saker D, Kara S,

Guzelel B and Mete UO: Investigation of miR-26b and miR-27b

expressions and the effect of quercetin on fibrosis in experimental

pulmonary fibrosis. J Mol Histol. 55:25–35. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Geng Q, Yan L, Shi C, Zhang L, Li L, Lu P,

Cao Z, Li L, He X, Tan Y, et al: Therapeutic effects of flavonoids

on pulmonary fibrosis: A preclinical Meta-analysis. Phytomedicine.

132(155807)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Zhang X, Cai Y, Zhang W and Chen X:

Quercetin ameliorates pulmonary fibrosis by inhibiting SphK1/S1P

signaling. Biochem Cell Biol. 96:742–751. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Xiao C, Tang Y, Ren T, Kong C, You H, Bai

XF, Huang Q, Chen Y, Li LG, Liu MY, et al: Treatment of silicosis

with quercetin depolarizing macrophages via inhibition of

mitochondrial damage-associated pyroptosis. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf.

286(117161)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Zhang H, Yang L, Han Q and Xu W: Original

antifibrotic effects of quercetin on TGF-β1-induced vocal fold

fibroblasts. Am J Transl Res. 14:8552–8561. 2022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Widiatmoko A, Fitri LE, Endharti AT and

Murlistyarini S: The effect of quercetin on phosphorylated p38,

Smad7, Smad2/3 nuclear translocation and collagen type I of keloid

fibroblast culture. J Biotech Res. 16:32–42. 2024.

|

|

47

|

Takano M, Deguchi J, Senoo S, Izumi M,

Kawami M and Yumoto R: Suppressive effect of quercetin against

bleomycin-induced Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in alveolar

epithelial cells. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 35:522–526.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Lee GB, Kim Y, Lee KE, Vinayagam R, Singh

M and Kang SG: Anti-inflammatory effects of quercetin, rutin, and

troxerutin result from the inhibition of NO production and the

reduction of COX-2 levels in RAW 264.7 cells treated with LPS. Appl

Biochem Biotechnol. 196:8431–8452. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Boots AW, Haenen GRMM and Bast A: Health

effects of quercetin: From antioxidant to nutraceutical. Eur J

Pharmacol. 585:325–337. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Kostyuk VA, Potapovich AI, Speransky SD

and Maslova GT: Protective effect of natural flavonoids on rat

peritoneal macrophages injury caused by asbestos fibers. Free Radic

Bio Med. 21:487–493. 1996.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Veith C, Drent M, Bast A, van Schooten FJ

and Boots AW: The disturbed redox-balance in pulmonary fibrosis is

modulated by the plant flavonoid quercetin. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol.

336:40–48. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|