Introduction

Cohesinopathies are a group of rare diseases caused

by defects in the cohesin complex. These disorders involve multiple

organ systems, including the brain, heart and skeleton, and stem

from impairments in fundamental cellular processes such as

chromosome segregation, DNA repair, DNA replication,

heterochromatin formation and gene transcription (1). The cohesin complex, an evolutionarily

conserved large functional unit, consists of four core proteins,

structural maintenance of chromosomes (SMC) protein 1A, SMC2, RAD21

and stromal antigen (STAG)1/2. Additionally, several regulatory

proteins associated with this complex have been implicated in a

wide range of human diseases (2).

The STAG2 gene (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man 300826,

NM_001042751), located on chromosome Xq25, comprises 34 exons and

encodes the STAG2 cohesin complex component, which is involved in

gene expression, DNA repair and genomic integrity (3). Variants in STAG2 have been

identified as the causative factor for neurodevelopmental

disorders, such as X-linked holoprosencephaly 13 (HPE13) and

Mullegama-Klein-Martinez syndrome (MKMS) (4). Patients with STAG2 variants

typically exhibit a wide range of phenotypic abnormalities,

including intellectual disability, developmental delay,

microcephaly, dysmorphic features, short stature, growth

restriction, language impairment, delayed puberty, microtia,

hearing loss and congenital heart and skeletal defects (5). At present, 19 STAG2 variants

have been reported in patients with HPE13 or MKMS (4-13).

These include five missense variants, eight nonsense variants, five

frameshift variants and one splice variant. Additional research is

needed to elucidate the genotype-phenotype associations and

underlying mechanisms of STAG2-related disorders.

Polycystic kidney disease (PKD) is a genetic

disorder characterized by the formation of numerous cysts in the

kidneys, leading to progressive kidney damage and eventual renal

failure (14). The PKD1

gene, located on chromosome 16, encodes polycystin-1, a large

transmembrane protein involved in cell signaling, calcium ion

regulation and the maintenance of normal renal tubular epithelial

cell function (15). Variants in

the PKD1 gene disrupt polycystin-1 function, resulting in

abnormal cell proliferation and the formation of fluid-filled cysts

(16). These cysts gradually

enlarge, compressing and replacing normal kidney tissue, thereby

impairing kidney function (17).

PKD1 variants are responsible for most cases of autosomal

dominant PKD (ADPKD), which is the most common form of PKD

(18).

In the present report, a novel de novo

heterozygous STAG2 variant [NM_001042750.2:c.1775_1777del,

p.(Pro592del)] and a novel heterozygous frameshift PKD1

variant [NM_001009944.3:c.8985delC, p.(Ser2996fs*78)] were

identified in a Chinese infant diagnosed with MKMS and familial

PKD. Furthermore, through a comprehensive review of the literature,

the genotypic, phenotypic and clinical features of STAG2-related

disorders were summarized.

Case report

Patients and methods. Patients

In June 2024, a Chinese family with a member

presenting seizures and developmental delays was referred to the

Department of Pediatric Neurology of Maternal and Child Health

Hospital of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region (Nanning, China) for

genetic evaluation. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics

Committee of Maternal and Child Health Hospital of Guangxi Zhuang

Autonomous Region (approval no. METc 2017-2-11) and conducted in

accordance with the principles of The Declaration of Helsinki.

Written informed consent was obtained from the patients and/or the

parents of the affected individual for the publication of clinical

data and images.

Whole-exome sequencing (WES) and Sanger

validation. WES and Sanger validation were performed on genomic

DNA extracted from 2 ml peripheral blood lymphocytes of the proband

and available family members with the Lab-Aid DNA kit (cat. no.

604016; Xiamen Zeesan Biotech Co., Ltd.). DNA integrity was

verified on a 1% agarose gel (≥20 kb high-molecular-weight band)

and quantified by a Qubit dsDNA BR Assay (cat. no. Q32853; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Trio-WES was carried out for the proband

and parents: 3 µg of each DNA sample were sheared to 180-250 bp,

end-repaired, A-tailed and ligated to Illumina-compatible adapters.

Exome enrichment was performed with the Agilent SureSelect Human

All Exon V5 capture kit (cat. no. 5190-6210; Agilent Technologies,

Inc.). Captured libraries were pooled equimolarly, and the 280-320

bp insert size was confirmed on an Agilent High-Sensitivity DNA

chip (Agilent Technologies, Inc.) run on the 2100 Bioanalyzer (cat.

no. 5067-4626; Agilent Technologies, Inc.). Post-ligation Illumina

NGS libraries served as the DNA source; their concentration was

measured by SYBR Green I qPCR with the KAPA Library Quantification

kit (Roche Diagnostics) using primers P5,

5'-AATGATACGGCGACCACCGA-3', and P7, 5'-CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGA-3',

and a six-point kit-supplied linearized standard series (20-0.0002

pM). Reactions (20 µl) were run on a CFX96 (Bio-Rad Laboratories,

Inc.) at 95˚C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of 95˚C for 30 sec

and 60˚C for 45 sec, and finally a 65-97˚C melt curve. Unknown

libraries were quantified by interpolation from the standard curve,

diluted to 2 nM, denatured with 0.2 N NaOH and loaded at 10 pM onto

an Illumina HiSeq 2000 flow-cell together with 1% PhiX control

(cat. no. FC-110-3001; Illumina, Inc.). Sequencing was performed

with the HiSeq 2000 Rapid SBS Kit v2, 100-cycle paired-end (cat.

no. FC-402-4021; Illumina, Inc.) to generate 100-bp paired-end

reads. Raw reads were aligned to the hg19/GRCh38 human reference

genome with BWA-MEM (v0.7.15; https://github.com/lh3/bwa), and variant calling was

completed using the Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK v3.4; Broad

Institute) following the best-practice workflow. Variant calling

and annotation were performed using LifeMap TGex Version 3.0

(https://auth.shanyint.com/; customised

website), with a focus on variants exhibiting a minor allele

frequency of ≤0.001 in public databases, including the 1000 Genomes

Project (https://www.internationalgenome.org/data), Exome

Sequencing Project (http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/) and Exome

Aggregation Consortium (http://exac.broadinstitute.org).

The functional impact of candidate variants was

predicted using in silico tools, including REVEL (https://sites.google.com/site/revelgenomics/),

PolyPhen-2 (http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/), Sorting

Intolerant From Tolerant (https://sift.bii.a-star.edu.sg/), Combined Annotation

Dependent Depletion (https://cadd.gs.washington.edu/snv), MutationTaster

(http://www.mutationtaster.org/) and

NMDEscPredictor (https://fursham-h.github.io/factR/reference/predictNMD.html).

SWISS-MODEL (https://swissmodel.expasy.org/) was used to construct

a 3D model of the STAG2 protein. Co-segregation analysis of the

STAG2 and PKD1 variants was performed among family

members using Sanger sequencing, with primers designed to amplify

the STAG2 variant [NM_001042750.2:c.1775_1777del,

p.(Pro592del)] and the PKD1 variant

[NM_001009944.3:c.8985delC, p.(Ser2996fs*78)]. PCR amplification

was performed with Takara PrimeSTAR Max DNA Polymerase (Takara

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) using the following thermocycling

conditions: Initial denaturation at 95˚C for 5 min; 35 cycles of

denaturation at 95˚C for 3 sec, annealing at 60˚C for 30 sec and

extension at 72˚C for 30 sec; and a final extension at 72˚C for 5

min. The primer sequences were as follows: STAG2 forward,

5'-TTTCCCTAAATGCCTCACAGAA-3' and reverse,

5'-AGGTACAGTTGTGGGCATGA-3'; and PKD1 forward,

5'-CTCTGAGACTGCGACATCCA-3' and reverse, 5'-CACAGGAAACACAAAGCGGA-3'.

The pathogenicity of candidate variants was assessed according to

the guidelines of the American College of Medical Genetics and

Genomics (ACMG)/Association for Molecular Pathology (AMP) and the

ClinGen Sequence Variant Interpretation Working Group (19,20).

Case presentation. Patient

characteristics

The proband (III.1), a 4-month-old female infant,

was the first child of unrelated non-consanguineous Chinese parents

(Fig. 1A). The patient was born

full-term at 40 weeks of gestation by vaginal delivery with a

normal birth weight (3.19 kg). The Apgar scores of the infant at 1,

5 and 10 min after birth were 9, 9 and 10, respectively (21). At the age of 4 months, the patient

was admitted to the Department of Pediatric Neurology of Maternal

and Child Health Hospital of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region for

seizures. The proband experienced the first generalized

tonic-clonic seizure at 3 months and 21 days old, with a frequency

of 1-2 seizures per day during the first 9 days. A 24-h ambulatory

electroencephalogram was performed, and the results showed

bilateral slow waves and spike-like slow waves in the frontal pole,

occipital and temporal areas (data not shown due to the large size

of the video). Global developmental delay was observed in the first

4 months of life, and the patient was unable to hold their head up

or roll over. A physical examination revealed that the patient had

mild short stature (60 cm, <-2 SD), hypotonia and dysmorphic

features, including microcephaly (head circumference of 39 cm,

<-1 SD), a narrow forehead, saddle nose, large ears,

micrognathia, incomplete cleft palate and microstomia (Fig. 1B). Additional findings included

spina bifida occulta and a duplication of the middle phalanx of the

third finger on the left hand. The neurodevelopmental parameters of

the infant were assessed using the Bayley Scales of Infant and

Toddler Development, Third Edition at ~6 months of age, and the

cognitive, motor and language developmental ages were equivalent to

those at 3, 4 and 2 months, respectively (22). Therefore, the patient was diagnosed

with MKMS. Renal ultrasound demonstrated increased renal

echogenicity (Fig. S1A). Notably,

the mother, aunt and grandmother of the patient were all diagnosed

with PKD, although no other malformations were reported in the

family history. The proband did not exhibit other symptoms of ADPKD

beyond the increased echogenicity observed in the renal ultrasound.

Additionally, the patient did not have hypertension, and both

urinalysis and serum creatinine levels were within normal ranges.

Brain magnetic resonance imaging was performed at 4 months of age,

and the results were normal (Fig.

S1B). Audiological evaluation revealed no hearing deficits, but

a middle ear infection was detected. The 4-month-old infant's ear

infection was managed with a 10-day course of high-dose amoxicillin

at 80-90 mg/kg per day, divided into two oral doses (~40 mg/kg

twice daily). The last follow-up of the child was in November 2025,

at which time the patient was 1.5 years old and developing

normally.

![Clinical and genetic features. (A)

Pedigree chart of the family of the proband with

Mullegama-Klein-Martinez syndrome and familial polycystic kidney

disease. The pedigree depicts the segregation of both the STAG2

(shown in black) and PKD1 (shown in blue) variants within the

family. (B) Facial appearance of the proband (Ⅲ-1) at the age of 4

months, showing microcephaly (head circumference of 39 cm, <-1

SD), narrow forehead, saddle nose, large ears, micrognathia and

microstomia. (C) The Sanger sequencing chromatograms illustrate the

presence of a novel heterozygous STAG2 variant

[NM_001042750.2:c.1775_1777del, p.(Pro592del)] and a novel

heterozygous frameshift PKD1 variant [NM_001009944.3:

c.8985delC, p.(Ser2996fs*78)] in the proband. (D) The spectrum of

STAG2 pathogenic variants. The red variant is the novel

variant identified in the present study. STAG, stromal antigen;

SCD, stromalin conservative domain; HEAT_SCC3-SA, cohesin subunit

SCC3/SA, HEAT-repeats domain.](/article_images/etm/31/3/etm-31-03-13057-g00.jpg) | Figure 1Clinical and genetic features. (A)

Pedigree chart of the family of the proband with

Mullegama-Klein-Martinez syndrome and familial polycystic kidney

disease. The pedigree depicts the segregation of both the STAG2

(shown in black) and PKD1 (shown in blue) variants within the

family. (B) Facial appearance of the proband (Ⅲ-1) at the age of 4

months, showing microcephaly (head circumference of 39 cm, <-1

SD), narrow forehead, saddle nose, large ears, micrognathia and

microstomia. (C) The Sanger sequencing chromatograms illustrate the

presence of a novel heterozygous STAG2 variant

[NM_001042750.2:c.1775_1777del, p.(Pro592del)] and a novel

heterozygous frameshift PKD1 variant [NM_001009944.3:

c.8985delC, p.(Ser2996fs*78)] in the proband. (D) The spectrum of

STAG2 pathogenic variants. The red variant is the novel

variant identified in the present study. STAG, stromal antigen;

SCD, stromalin conservative domain; HEAT_SCC3-SA, cohesin subunit

SCC3/SA, HEAT-repeats domain. |

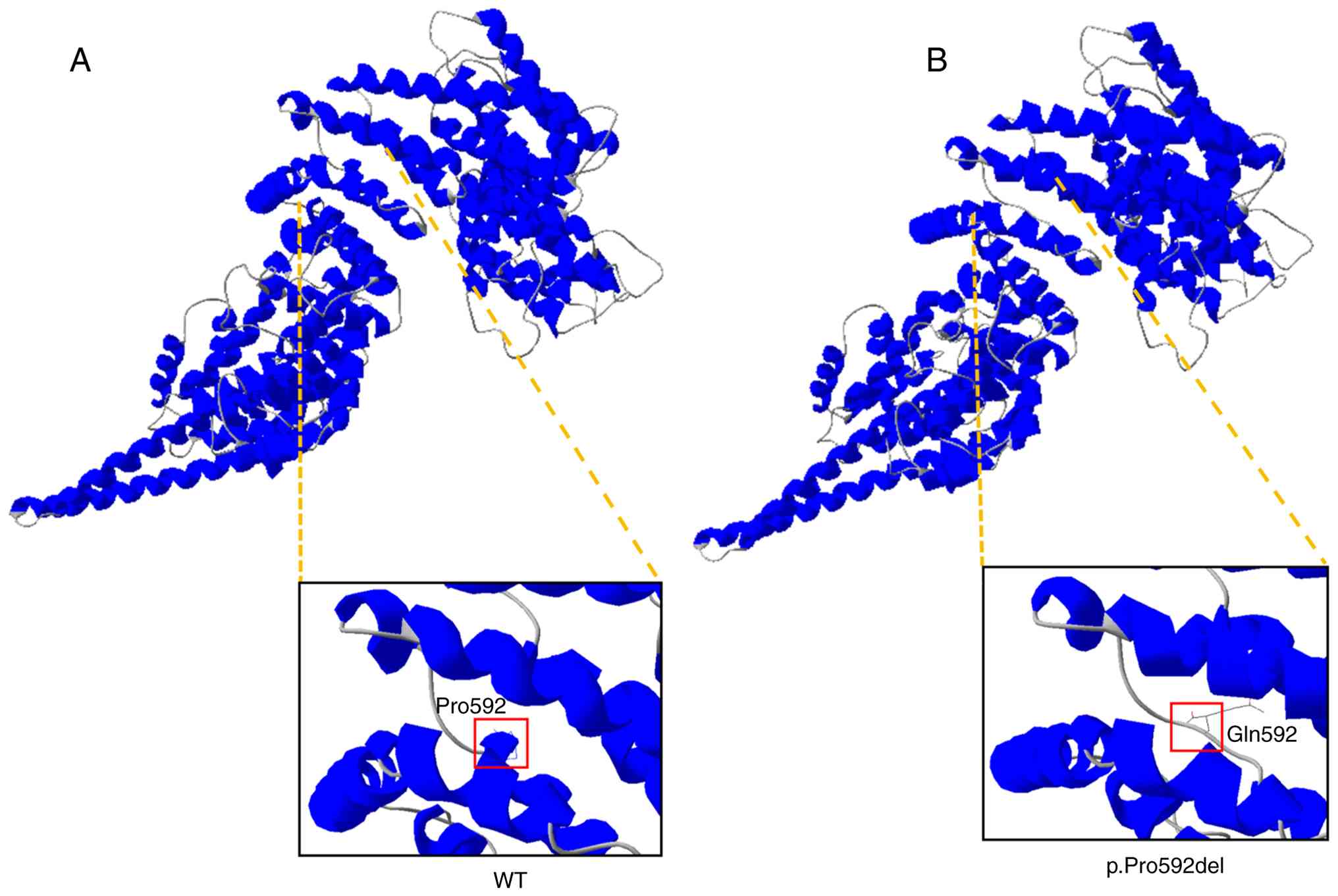

Genetic analysis. Trio-WES identified a novel

de novo heterozygous in-frame variant in STAG2

[NM_001042750.2:c.1775_1777del, p.(Pro592del)] and a novel

heterozygous frameshift variant in PKD1

[NM_001009944.3:c.8985delC, p.(Ser2996fs*78)] (Fig. 1C). Both variants were confirmed in

the proband and the family members by Sanger sequencing. The

STAG2 variant [c.1775_1777del, p.(Pro592del)] was absent in

the parents, aunt and grandmother, confirming its de novo

origin. By contrast, the PKD1 variant [c.8985delC,

p.(Ser2996fs*78)] was identified in the mother, aunt and

grandmother of the proband (Fig.

1C). To the best of our knowledge, these variants have not been

reported previously and are not identified in public databases,

including the Exome Sequencing Project (https://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/), Genome

Aggregation Database (https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/), 1000 Genomes

Project (https://www.internationalgenome.org/data) and the

Single Nucleotide Polymorphism database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SNP/), as well as

disease-related databases such as ClinVar (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/) and the Human

Gene Mutation Database (http://www.hgmd.cf.ac.uk/ac/). To date, a total of 21

distinct STAG2 variants, including the one reported here, have been

identified in patients with HPE13 or MKMS, distributed across the

entire gene (Fig. 1D). The variant

described in the present report falls within the HEAT_SCC3-SA

domain. To further analyze the effect of the amino acid changes

caused by the c.1775_1777del, p.(Pro592del) variant on the

structure of the protein, the variant was modelled using the

wild-type STAG2 crystal structure. Pro592 is located at a junction

between multiple α-helices, where it may influence their stability

and packing (Fig. 2A); however,

Pro592del leads to structural defects, disrupting the formation of

α-helices (Fig. 2B). Therefore, we

hypothesize that the c.1775_1777del, p.(Pro592del) variant may lead

to defective protein folding and ultimately reduced stability of

STAG2. According to the ACMG/AMP guidelines, the variant

c.1775_1777del is classified as likely pathogenic (PS2 +

PM2_Supporting + PP3), while the c.8985delC variant is classified

as pathogenic (PVS1 + PM2_Supporting + PP1 + PP4) (Table I).

| Table IPredicted pathogenicity of

STAG2 and PKD1 variants. |

Table I

Predicted pathogenicity of

STAG2 and PKD1 variants.

| Gene | Reference allele

(GRCh38) | Variant | Inheritance | Variant Taster |

NMDEscPredictor | PolyPhen-2 | SIFT | CADD | ACMG/AMP

guidelines |

|---|

| STAG2

(NM_001042750.2) | ChrX:124063159_

124063161 | c.1775_1777del,

p.(Pro592del) | DNV | D | NA | NA | NA | NA | LP (PS2 + PM2_

Supporting + PP3) |

| PKD1

(NM_001009944.3) | Chr16:2102597 | c.8985delC,

p.(Ser2996fs*78) | Maternal | D | Causes NMD | NA | NA | NA | P (PVS1 +

PM2_Supporting + PP1 + PP4) |

Discussion

STAG2 has been identified as a causative gene

associated with a spectrum of neurodevelopmental disorders,

including microcephaly, microphthalmia, hearing loss, developmental

delay, dysmorphic features, congenital heart defects and digital

anomalies (4,5). The association between STAG2

and neurodevelopmental disorders was initially established through

the identification of copy number variants affecting this gene. In

addition, this association has been corroborated by the

identification of novel single nucleotide variants, which have

provided deeper insights into the genetic architecture of

STAG2-related disorders (4,5). At

present, 19 STAG2 variants have been identified in 25

patients with HPE13 or MKMS (4-13).

In the current report, trio-based WES was performed, which

identified a novel de novo heterozygous variant in the

STAG2 gene in a female Chinese infant. The patient exhibited

a clinical phenotype consistent with STAG2-related

disorders, including epilepsy, global developmental delay, short

stature, hypotonia, dysmorphic features, incomplete cleft palate,

micrognathia, spina bifida occulta and a duplication of the middle

phalanx of the third finger on her left hand; therefore, the

patient was diagnosed with MKMS.

The clinical features of the 26 reported patients

with HPE13 or MKMS, including the patient in the current report,

are summarized in Table II.

Phenotypic analysis of these patients revealed marked heterogeneity

in the clinical features associated with pathogenic or likely

pathogenic variants of the STAG2 gene; however, certain

common features were identified in >50% of cases. All patients

with available data exhibited developmental abnormalities of

varying severity across multiple domains. Intellectual disability

or developmental delay was observed in all patients with available

data (20/20), ranging from mild to severe. Pathogenic variants in

the STAG2 gene are associated with a spectrum of brain

abnormalities. Brain anomalies were observed in almost all patients

(15/17), and included microcephaly, delayed or incomplete

myelination, myelin hypotrophy, agenesis or dysgenesis of the

corpus callosum, white matter hypoplasia, holoprosencephaly and

atelencephaly. Among these, holoprosencephaly (9/19) was the most

frequently reported, whereas alobar holoprosencephaly represented

the most severe manifestation. In the present patient, however, no

brain malformations were observed at 4 months of age. Additionally,

dysmorphic facial features were present in nearly all cases

(19/21); individuals with MKMS typically exhibit characteristic

facial dysmorphisms, including a broad forehead, low-set ears, a

short and broad nose, a shallow philtrum, cleft lip/palate, a small

mouth with thin lips and a small, receding chin (4,13).

Ocular anomalies such as hypertelorism, hypotelorism, ptosis and

epicanthal folds, as well as facial asymmetry, are also commonly

observed. By contrast, patients with X-linked HPE13 often present

with midline facial defects, such as a single central incisor, a

flat nasal bridge and a proboscis (10). Ocular and eyelid abnormalities,

including microphthalmia, anophthalmia, colobomas, ptosis and

ankyloblepharon, are frequently noted, alongside oral and

mandibular anomalies such as microstomia, macroglossia, cleft

lip/palate and micrognathia. Dysmorphic features were shared in

both conditions. The present patient also exhibited mild dysmorphic

features including mild microcephaly, narrow forehead, saddle nose,

large ears, micrognathia, incomplete cleft palate and microstomia.

Thoracic vertebra abnormalities were observed in more than

two-thirds (11/14) of the patients, primarily affecting the

thoracic spine; these included hemivertebrae, butterfly vertebrae,

scoliosis, spina bifida and fused ribs. Other skeletal anomalies

involved left hip dysplasia, broad hands and feet and

hyperextensibility of the hand and foot joints. The present patient

also presented with spina bifida occulta accompanied by a novel

clinical manifestation of middle phalanx duplication in the third

digit of the left hand. Congenital cardiac malformations were also

common (10/15), with a spectrum of anomalies ranging from patent

foramen ovale to severe dextroposition of the heart and aortic

valve atresia; notably, the present patient had no cardiac

problems. Additional dysmorphic features included seizures, left

facial palsy, mild left pelviectasis, sacral dimple, congenital

dislocation of the hip, gastroesophageal reflux, hypotonia,

pulmonary hypoplasia, single kidney, hearing loss, polycystic

kidney, duodenal atresia and left-sided diaphragmatic hernia. These

findings highlight the broad phenotypic spectrum associated with

STAG2 gene variants and underscore the importance of a

comprehensive clinical evaluation in patients with these

conditions. Further studies are needed to elucidate the underlying

mechanisms and improve diagnostic and therapeutic approaches.

| Table IIClinical features of patients with

STAG2 variants. |

Table II

Clinical features of patients with

STAG2 variants.

|

Patienta | Sex | STAG2

variants | Inheritance | ID/DD | Brain

abnormalities | Micro-cephaly | Dysmorphic features

and malformations | Cleft

lip/palate | Congenital heart

defects | Thoracic vertebra

anomalies | Seizures | Other features | (Refs.) |

|---|

| 1 | M | c.3027A>T,

p.(Lys1009Asn) | De novo | + | - | + | + | - | - | - | - | Polycystic

kidney | (4) |

| One family (5

patients) | All M | c.980G>A,

p.(Ser327Asn) | Maternally | 5/5 | NA | 0/5 | 5/5 | 1/5 | NA | NA | 0/5 | NA | (5) |

| 7 | F | c.3097C>T,

p.(Arg1033*) | De novo | NA | HPE | NA | NA | + | Left heart

hypoplasia | NA | - | NA | (6) |

| 8 | F | c.2229G>A,

p.(Trp743*) | De novo | + | White matter

hypoplasia | - | + | + | - | Hemivertebra | + | Amblyopia | |

| 9 | F | c.205C>T,

p.(Arg69*) | De novo | + | HCC, subarachnoid

cyst, subgaleal | + | + | + | VSD | Scoliosis,

hemivertebra, butterfly vertebra | - | Left facial palsy,

mild left pelviectasis | (7) |

| 10 | F | c.1913_1922del,

p.(Ala638Valfs*10) | De novo | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| 11 | F | c.1840C>T,

p.(Arg614*) | De novo | + | Cystic pituitary

lesion | + | NA | NA | NA | Scoliosis | - | Sacral dimple,

CDH | (8) |

| 12 | F | c.418C>T,

p.(Gln140*) | De novo | + | NA | - | + | - | Left heart

hypoplasia, VSD, CA | Scoliosis, rib

fusion, vertebral clefts | + | Gastroesophageal

reflux, CDH | |

| 13 | F | c.1605T>A,

p.(Cys535*) | De novo | + | NA | + | + | - | NA | Scoliosis, rib

fusion | + | Hypotonia | |

| 14 | F | c.1658_1660delinsT,

p.(Lys553Ilefs*6) | De novo | + | HPE

(microform) | + | + | - | NA | Scoliosis, rib

fusion | + | Hypotonia | (9) |

| 15 | F | c.1811G>A,

p.(Arg604Gln) | De novo | + | NA | + | + | NA | - | Vertebral

clefts | - | Gastroesophageal

reflux, CDH, pulmonary hypoplasia | |

| 16 | M | c.476A>G,

p.(Tyr159Cys) | De novo | + | Ectopic posterior

pituitary, short pituitary stalk | - | + | + | Minimal PFO | Scoliosis | - | Single kidney,

hypotonia | |

| 17 | F | c.205C>T,

p.(Arg69*) | De novo | + | HPE

(semi-lobar) | + | + | + | PFO, PDA | - | - | NA | (10) |

| 18 | F | c.436C>T,

p.(Arg146*) | NA | NA | HPE (alobar) | + | + | - | VSD | Hemivertebra | - | Duodenal

atresia | |

| 19 | F | c.775C>T,

p.(Arg259*) | De novo | + | HPE (septo-optic

dysplasia) | - | - | - | VSD | NA | - | Left hip dysplasia,

bilateral optic nerve hypoplasia | |

| 20 | F | c.3034C>T,

p.(Arg1012*) | De novo | NA | HPE (alobar) | + | + | + | NA | Spina bifida | - | Gastroesophageal

reflux | |

| 21 | F | c.2898_2899del,

p.(Glu968Serfs*15) | De novo | + | HPE

(microform) | + | NA | NA | - | NA | - | NA | |

| 22 | F | c.2533+1G>A | Maternally | NA | HPE

(semi-lobar) | + | - | - | Left heart

hypoplasia, DORV | NA | - | Hypotonia | |

| 23 | F | c.1639delG,

p.(Val547Cysfs*29) | De novo | + | + | NA | + | NA | NA | NA | + | Hearing loss | (11) |

| 24 | F | c. 3458_3459delTT,

p.(Leu1153Argfs*3) | De novo | NA | Dandy-Walker

malformation | - | NA | - | Dextrocardia, CA,

VSD | NA | - | CDH | (12) |

| 25 | M | c.475T>C,

p.(Tyr159His) | Maternally | + | HPE, PMG, HCC | - | + | - | PFO | - | + | Hands and feet as

well as fingers and toes were broad, with soft dorsal surfaces; the

nails were deeply inserted and the joints of the hands and feet

were hyperextensible | (13) |

| 26 | F | c.1775_1777delCTC,

p.(Pro592del) | De novo | + | - | + | + | + | - | Spina bifida | + | Polycystic kidney,

hypotonia | Present case |

| Total | M=8, F=18 | Frameshift=5,

Splicing=1, Nonsense=8, In-frame deletion=1, Missense=5 | | 20/20 | 15/17 | 12/23 | 19/21 | 8/21 | 10/15 | 11/14 | 7/25 | | |

To date, only 26 affected individuals (including the

present case) have been reported with STAG2 variants,

including five missense variants, one in-frame deletion (present

case), eight nonsense variants, five frameshift variants and one

splice variant (4-13).

Notably, a distinct pattern emerged upon further analysis of these

cases; all male patients (8/8) harbored hemizygous missense

variants, whereas nearly all female patients (16/18) carried

heterozygous null variants. A study by Cheng et al (23) showed that Stag2 knockout

mouse embryos displayed severe developmental defects and underwent

necrosis at day E11.5, whereas conditional knockout mice with

Stag2 deletion in the nervous system exhibited growth

retardation, neurological defects and early death. These results

suggest that a hemizygous deletion of the STAG2 gene may

lead to severe phenotypes and could potentially cause embryonic

lethality, thereby preventing the generation of male individuals

with null variants. In addition, the present findings suggested

that female patients with truncating variants exhibit a higher

incidence of congenital malformations, such as brain malformations,

cleft lip and palate, congenital heart disease, thoracic spine

anomalies and epileptic seizures, compared with male patients with

missense variants (Table III).

These observations are likely driven by the greater pathogenic

potential of truncating variants relative to missense variants,

rather than by sex differences. Specifically, null variants

typically result in a complete loss of function of the STAG2

protein, leading to more profound disruptions in cellular

processes. By contrast, missense variants may retain partial

protein function, potentially explaining the milder phenotypic

manifestations observed in these cases. However, the precise

mechanisms underlying these observations remain unclear and warrant

further investigation through more comprehensive studies.

| Table IIIComparison of the effects of sex and

variant type on clinical manifestations. |

Table III

Comparison of the effects of sex and

variant type on clinical manifestations.

| Clinical

manifestation | Male patients with

missense variants, n (%) | Female patients

with truncating variantsa, n (%) | Total, n (%) |

|---|

| DD/ID | 8/8 (100.00) | 10/10 (100.00) | 18/18 (100.00) |

| Microcephaly | 1/8 (12.50) | 9/13 (69.23) | 10/21 (47.62) |

| Brain

abnormalities | 2/3 (66.67) | 13/13 (100.00) | 15/16 (93.75) |

| Dysmorphic

features | 8/8 (100.00) | 9/11 (81.82) | 17/19 (89.47) |

| Cleft

lip/palate | 2/8 (25.00) | 5/12 (41.67) | 7/20 (35.00) |

| Congenital heart

defects | 2/3 (66.67) | 8/10 (80.00) | 10/13 (76.92) |

| Thoracic vertebra

anomalies | 1/3 (33.33) | 8/9 (88.89) | 9/12 (75.00) |

| Seizures | 1/8 (12.50) | 5/15 (33.33) | 6/23 (26.09) |

In the present study, the proband was also

considered to have PKD. A renal ultrasound conducted at the age of

4 months revealed enhanced renal echogenicity. Furthermore,

whole-exome sequencing in the proband identified pathogenic

variants in the PKD1 gene. A familial investigation further

indicated that the mother, aunt and grandmother of the proband had

previously been diagnosed with PKD. ADPKD is a common genetic renal

disorder with an estimated worldwide incidence of 1:1,000. ADPKD is

frequently associated with progressive renal failure (18), and variants in the PKD1 gene

are responsible for ~85% of ADPKD cases. Trio-WES analysis

identified a heterozygous pathogenic variant [c.8985delC,

p.(Ser2996fs*78)] in exon 25 of the PKD1 gene in both the

proband and the mother. Further validation in other family members

by Sanger sequencing confirmed that this heterozygous variant was

also detected in the affected aunt and grandmother of the patient,

but it was not detected in other unaffected family members. There

was co-segregation of the variant with the disease phenotype in

this family. The novel frameshift variant was predicted to be

disease-causing by MutationTaster, resulting in a premature

termination codon or a translational frameshift, leading to the

production of a truncated protein and markedly reduced mRNA levels

due to nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. Consistent with the ACMG/AMP

guidelines, this frameshift variant was classified as pathogenic,

with the evidence criteria PVS1, PM2_supporting, PP1 and PP4. This

finding confirmed that PKD1 defects are likely to be the

cause of PKD in this family. ADPKD is characterized by

age-dependent and progressive clinical manifestations, usually

becoming apparent in adulthood (18). While the proband, who was only 4

months old, had not shown typical PKD, these symptoms are expected

to become more evident as the proband grows older. Therefore, a

long-term follow-up plan needs to be established for this patient,

with regular monitoring of renal ultrasound, glomerular filtration

rate and urinary protein levels, to detect renal structural or

functional abnormalities at an early stage and intervene in a

timely manner. Notably, studies by Mullegama et al (4) and Yuan et al (9) reported two patients with STAG2

variants who exhibited distinct renal anomalies, one presented with

polycystic kidneys, while the other had a solitary kidney; however,

genetic testing in these cases did not identify variants associated

with PKD or renal dysplasia. Although no definitive studies have

yet explored the specific role of STAG2 in kidney development, its

widespread expression in various tissues, including the kidneys,

and its critical role in cell proliferation, differentiation and

gene regulation suggest that STAG2 may influence kidney development

(5,7-8,10,24).

For instance, in renal cancer tissues, the expression level of

STAG2 is markedly reduced, and its function is closely

associated with cell proliferation and migratory capacity,

indicating a potential role in the normal physiological processes

of kidney cells (23).

Additionally, while STAG2 and polycystin-1 are involved in

different biological pathways, their functions may be

interconnected at the cellular level. For instance, abnormalities

in cell division and proliferation caused by STAG2 mutations

may indirectly affect kidney development or tissue homeostasis,

thereby potentially influencing the manifestation of symptoms

associated with polycystin-1; however, there is currently no direct

evidence to suggest a clear molecular interaction between STAG2 and

polycystin-1. In the present report, although pathogenic variants

in the PKD1 gene were detected in the patients, it cannot be

excluded that STAG2 gene variants may be associated with

renal abnormalities. Furthermore, to accurately assess the role of

STAG2 in kidney development, its potential interaction with

polycystin-1 and the impact of STAG2 variants on related

diseases, further functional studies involving larger patient

cohorts are required.

In conclusion, in the present study, a novel de

novo STAG2 variant was identified in a Chinese female infant

with MKMS, expanding the clinical and genetic spectrum of

STAG2-related disorders. Phenotypic analysis of additional

25 patients revealed marked heterogeneity; however, common features

included intellectual disability, brain abnormalities, dysmorphic

features and skeletal anomalies. Notably, loss-of-function variants

were associated with more severe phenotypes compared with missense

or in-frame variants, likely due to the complete loss of

STAG2 protein function. Additionally, a sex-biased

distribution of variant types was observed, in which male patients

predominantly harbored hemizygous missense variants, whereas female

patients typically harbored heterozygous null variants. This

pattern suggests potential sex-biased differences in disease

severity, possibly influenced by X-chromosome inactivation or

residual protein function in male patients. A pathogenic

PKD1 variant was also identified in the present patient,

providing an independent explanation for the observed renal

abnormalities. However, it is noteworthy that renal anomalies,

including cystic dysplasia and renal hypoplasia, have also been

reported in other STAG2 variant carriers without concurrent

PKD1 variants or other identified nephropathy-associated

genetic alterations. This phenotypic overlap suggests a potential

pleiotropic role of STAG2 in renal organogenesis.

Nevertheless, the mechanistic relationship between STAG2

variants and renal pathology remains poorly understood. In summary,

the present findings emphasized the importance of genetic testing

in diagnosing STAG2-related disorders. Future research

should prioritize functional studies in larger cohorts to elucidate

the molecular mechanisms of STAG2 and its potential role in

renal development. Such insights are critical for developing

targeted therapies and improving the clinical management of

patients with STAG2-related conditions.

Supplementary Material

Clinical features of the proband. (A)

An ultrasound examination at the age of 4 months revealed markedly

increased echogenicity in the left kidney. (B) At 4 months of age,

an MRI scan of the brain revealed no abnormalities.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present study was funded by the Health Department

of Guangxi Province (grant nos. Z-A20220256, Z20190311 and

Z20210309).

Availability of data and materials

The sequencing data generated in the present study

may be found in the Sequence Read Archive database under accession

number PRJNA1321735 or at the following URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/PRJNA1321735.

The other data generated in the present study may be requested from

the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

QY and JL designed the study and drafted the

manuscript. QiaZ, SheY, XZ, YR, SZ, ShaY, QinZ and ZQ collected the

patients' clinical information and analyzed the WES data. QY and

QiaZ revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the

coordination of the study and revised the manuscript. QY and JL

confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and

approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study, involving the use of genetic

testing for diagnosis, was approved by the Ethics Committee of

Maternal and Child Health Hospital of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous

Region (approval no. METc 2017-2-11), and adhered to the principles

of The Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent for

genetic testing was obtained from the parents of the affected

individual and the other relatives examined.

Patient consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from all adult

patients and the parents of the minor individual for the

publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included

in this article.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Losada A: Cohesin in cancer: Chromosome

segregation and beyond. Nat Rev Cancer. 14:389–393. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Musio A, Selicorni A, Focarelli ML,

Gervasini C, Milani D, Russo S, Vezzoni P and Larizza L: X-linked

cornelia de Lange syndrome owing to SMC1L1 variants. Nat Genet.

38:528–530. 2006.

|

|

3

|

Solomon DA, Kim T, Diaz-Martinez LA, Fair

J, Elkahloun AG, Harris BT, Toretsky JA, Rosenberg SA, Shukla N,

Ladanyi M, et al: Variantal inactivation of STAG2 causes aneuploidy

in human cancer. Science. 333:1039–1043. 2011.

|

|

4

|

Mullegama SV, Klein SD, Mulatinho MV,

Senaratne TN and Singh K: UCLA Clinical Genomics Center. Nguyen DC,

Gallant NM, Strom SP, Ghahremani S, et al: De novo loss-of-function

variants in STAG2 are associated with developmental delay,

microcephaly, and congenital anomalies. Am J Med Genet A.

173:1319–1327. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Soardi FC, Machado-Silva A, Linhares ND,

Zheng G, Qu Q, Pena HB, Martins TMM, Vieira HGS, Pereira NB,

Melo-Minardi RC, et al: Familial aSTAG2 germline variant

defines a new human cohesinopathy. NPJ Genom Med. 2(7)2017.

|

|

6

|

Aoi H, Lei M, Mizuguchi T, Nishioka N,

Goto T, Miyama S, Suzuki T, Iwama K, Uchiyama Y, Mitsuhashi S, et

al: Nonsense variants of STAG2 result in distinct congenital

anomalies. Hum Genome Var. 7(26)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Mondal G, Stevers M, Goode B, Ashworth A

and Solomon DA: A requirement for STAG2 in replication fork

progression creates a targetable synthetic lethality in

cohesin-mutant cancers. Nat Commun. 10(1686)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Yu L, Sawle AD, Wynn J, Aspelund G, Stolar

CJ, Arkovitz MS, Potoka D, Azarow KS, Mychaliska GB, Shen Y, et al:

Increased burden of de novo predicted deleterious variants in

complex congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Hum Mol Genet.

24:4764–4773. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Yuan B, Neira J, Pehlivan D, Santiago-Sim

T, Song X, Rosenfeld J, Posey JE, Patel V, Jin W, Adam MP, et al:

Clinical exome sequencing reveals locus heterogeneity and

phenotypic variability of cohesinopathies. Genet Med. 21:663–675.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Kruszka P, Berger SI, Casa V, Dekker MR,

Gaesser J, Weiss K, Martinez AF, Murdock DR, Louie RJ, Prijoles EJ,

et al: Cohesin complex-associated holoprosencephaly. Brain.

142:2631–2643. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Epilepsy Genetics Initiative. The epilepsy

genetics initiative: Systematic reanalysis of diagnostic exomes

increases yield. Epilepsia. 60:797–806. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Provenzano A, La Barbera A, Lai F, Perra

A, Farina A, Cariati E, Zuffardi O and Giglio S: Non-invasive

detection of a de novo frameshift variant of stag2 in a

female fetus: Escape genes influence the manifestation of X-linked

diseases in females. J Clin Med. 11(4182)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Freyberger F, Kokotović T, Krnjak G,

Frković SH and Nagy V: Expanding the known phenotype of

Mullegama-Klein-Martinez syndrome in male patients. Hum Genome Var.

8(37)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Harris PC and Torres VE: Polycystic kidney

disease. Annu Rev Med. 60:321–337. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Hughes J, Ward CJ, Peral B, Aspinwall R,

Clark K, San Millán JL, Gamble V and Harris PC: The polycystic

kidney disease 1 (PKD1) gene encodes a novel protein with multiple

cell recognition domains. Nat Genet. 10:151–160. 1995.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Qian F, Germino FJ, Cai Y, Zhang X, Somlo

S and Germino GG: PKD1 interacts with PKD2 through a probable

coiled-coil domain. Nat Genet. 16:179–183. 1997.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Grantham JJ, Mulamalla S and

Swenson-Fields KI: Why kidneys fail in autosomal dominant

polycystic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 7:556–566.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Cornec-Le Gall E, Alam A and Perrone RD:

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Lancet. 393:919–935.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S,

Gastier-Foster J, Grody WW, Hegde M, Lyon E, Spector E, et al: ACMG

Laboratory quality assurance committee. Standards and guidelines

for the interpretation of sequence variants: A joint consensus

recommendation of the American College of Medical genetics and

genomics and the association for molecular pathology. Genet Med.

17:405–424. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Rivera-Muñoz EA, Milko LV, Harrison SM,

Azzariti DR, Kurtz CL, Lee K, Mester JL, Weaver MA, Currey E,

Craigen W, et al: ClinGen variant curation expert panel experiences

and standardized processes for disease and gene-level specification

of the ACMG/AMP guidelines for sequence variant interpretation. Hum

Mutat. 39:1614–1622. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Apgar V: A proposal for a new method of

evaluation of the newborn infant. Originally published in July.

1953, volume 32, pages 250-259. Anesth Analg. 120:1056–1059.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Spencer-Smith MM, Spittle AJ, Lee KJ,

Doyle LW and Anderson PJ: Bayley-III cognitive and language scales

in preterm children. Pediatrics. 135:e1258–e1265. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Cheng N, Li G, Kanchwala M, Evers BM, Xing

C and Yu H: STAG2 promotes the myelination transcriptional program

in oligodendrocytes. Elife. 12(e77848)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Yu C, Dai D and Xie J: Molecular subtype

classification of papillary renal cell cancer using miRNA

expression. Onco Targets Ther. 12:2311–2322. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

![Clinical and genetic features. (A)

Pedigree chart of the family of the proband with

Mullegama-Klein-Martinez syndrome and familial polycystic kidney

disease. The pedigree depicts the segregation of both the STAG2

(shown in black) and PKD1 (shown in blue) variants within the

family. (B) Facial appearance of the proband (Ⅲ-1) at the age of 4

months, showing microcephaly (head circumference of 39 cm, <-1

SD), narrow forehead, saddle nose, large ears, micrognathia and

microstomia. (C) The Sanger sequencing chromatograms illustrate the

presence of a novel heterozygous STAG2 variant

[NM_001042750.2:c.1775_1777del, p.(Pro592del)] and a novel

heterozygous frameshift PKD1 variant [NM_001009944.3:

c.8985delC, p.(Ser2996fs*78)] in the proband. (D) The spectrum of

STAG2 pathogenic variants. The red variant is the novel

variant identified in the present study. STAG, stromal antigen;

SCD, stromalin conservative domain; HEAT_SCC3-SA, cohesin subunit

SCC3/SA, HEAT-repeats domain.](/article_images/etm/31/3/etm-31-03-13057-g00.jpg)