Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is known to

cause a variety of systemic and ocular manifestations, including

conjunctivitis, retinal vein occlusion, acute macular

neuroretinopathy and neovascular glaucoma (1-3).

Following adjustment of the national dynamic zero-COVID strategy in

China, a rapid surge in cases of COVID-19 occurred after November

14, 2022, particularly in Beijing (4). In December 2022 during an outbreak of

the Omicron variant of COVID-19, the number of individuals with

acute primary angle closure (APAC) following COVID-19 was observed

to increase sharply. Due to the Omicron variant s combination

of high transmissibility, altered tropism for ACE2-rich tissues and

ability to provoke a significant systemic inflammatory

response-even in mild cases - are the key characteristics that may

explain its observed association with unmasking or triggering APAC

in a broader, and often younger, population with susceptible ocular

anatomy (1). Several

ophthalmologists expressed concern regarding the potential impact

of COVID-19 on patients with APAC (5-7).

Zhou et al (5) reported

that during the 2020 lockdown in Wuhan, the incidence of blindness

secondary to APAC was higher than that during in 2021, when the

lockdown policy was not implemented. Barosco et al (6) reported a bilateral case of APAC that

may have been caused by COVID-19 treatment. In addition, Au

(7) described a case of monocular

APAC following COVID-19 during the Omicron outbreak in Hong Kong,

China.

Previous studies have mainly focused on the impact

of the COVID-19 pandemic on the self-management, telemedicine,

prognosis and mental state of patients with glaucoma, and research

on the clinical characteristics and pathogenesis of APAC following

COVID-19 is limited (8-10).

The present study reports on the clinical characteristics and

possible pathogenesis of APAC following COVID-19 infection and

their differences from those of APAC without COVID-19.

Patients and methods

Participants and perioperative

assessments

The present retrospective study of patients with

APAC following COVID-19 was performed at the Xiamen Eye Center of

Xiamen University (Xiamen, China). The study was approved by the

Institutional Review Board of Xiamen Eye Center (approval no.

XMYKZX-KY-2023-003) and was conducted in accordance with the tenets

of the Declaration of Helsinki. All analyzed data were anonymized

and deidentified.

All enrolled participants underwent a series of

ocular examinations and received appropriate treatments.

Demographic data, including age, sex and laterality,

epidemiological data, including the time interval between fever and

APAC onset (IFO), ocular parameters such as the anterior chamber

depth (ACD), lens thickness and lens nucleus hardness graded using

the Lens Opacities Classification System III (11), and treatment procedures were

collected from the electronic outpatient medical record system.

Ocular biometry was performed at presentation using a Lenstar

LS-900 instrument (Haag-Streit Diagnostics) and ultrasound

biomicroscopy (UBM) was also conducted. Pupil diameter measurements

were obtained without the administration of any antiglaucoma

treatments or drugs for miosis or intraocular pressure (IOP)

reduction. A single examiner (YX) assessed the anterior chamber

angle structure, including the quadrants of angle closure, and

evaluated ciliary body morphology for the presence or absence of

ciliary body detachment under darkroom conditions using UBM.

Grouping and perioperative

managements

The study included a post-COVID-19 group and a

pre-pandemic group. The inclusion criteria for the post-COVID-19

group were as follows: All patients diagnosed with APAC who had a

positive result for a severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus

2 (SARS-CoV-2) RNA test within 15 days prior to APAC onset, and who

first presented at the eye center between December 1, 2022 and

January 31, 2023. The exclusion criteria for the post-COVID-19

group were: i) Patients with APAC who had not undergone SARS-CoV-2

RNA testing; ii) patients with APAC who had previously undergone

anti-glaucoma surgery or cataract phacoemulsification (PH) with or

without intraocular lens implantation; and iii) patients with APAC

lacking complete epidemiological or ophthalmic examination data.

The pre-pandemic group comprised patients with APAC and complete

essential data who presented between December 1, 2018 and January

31, 2019, when COVID-19 was not prevalent. All patients, regardless

of their group assignment, were recruited from the Outpatient or

Emergency Department of Xiamen Eye Center. All patients were of

Chinese Han ethnicity, and all eyes affected by APAC in each

enrolled patient were included in the analysis.

Reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain

reaction (RT-qPCR) was performed to detect the open reading frame

1ab (ORF1ab) and nucleocapsid (N) genes of SARS-CoV-2 using a

TaqMan probe-based RT-qPCR method. A novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV)

Nucleic Acid Diagnostic Kit (PCR-Fluorescence Probing) (Sansure

Biotech Inc.) was used according to the manufacturer s

instructions, with human ribonuclease P as the internal control

gene. If both the ORF1ab and N genes exhibited a clear exponential

amplification phase with a cycle threshold value of ≤36, the result

was considered positive. The specific protocol encompassed three

main steps: First, RNA was extracted from nasopharyngeal swab

samples using the Sansure kit s proprietary lysis/binding

buffer, followed by reverse transcription at 50˚C for 30 min to

synthesize cDNA. Subsequent qPCR detection, employing undisclosed

primer and probe sequences, was then performed. The thermal cycling

conditions included cDNA pre denaturation at 95˚C for 1 min,

followed by 45 amplification cycles (denaturation at 95˚C for 15

sec, and annealing, extension and fluorescence collection at 60˚C

for 30 sec), yielding final cycle threshold values.

The diagnostic criteria for APAC were as follows

(5,12): i) Presence of at least two of the

following symptoms: Ocular or periocular pain, nausea and/or

vomiting, or a history of intermittent blurring of vision with

halos; ii) a IOP of >21 mmHg at presentation; and iii) presence

of at least one of the following signs: Conjunctival hyperemia,

cornea edema, a mid-dilated unreactive pupil or a shallow anterior

chamber. APAC was diagnosed by ophthalmologists (both YX and LZ).

In cases of disagreement, another two expert ophthalmologist (both

JZ and YW) were consulted to make the final decision.

All patients with a definite diagnosis of APAC,

regardless of group assignment, were managed according to the

following procedures. First, all patients were treated with a

miotic agent (2% pilocarpine, one drop every 10 min, 6 times in

total). The accompanying IOP-lowering eyedrops were selected from a

range of standard classes (beta-blocker, 2% carteolol, one drop,

twice daily; alpha-2 adrenergic agonist, 0.1% brimonidine, one

drop, 3 times daily; carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, 1% brinzolamide,

one drop, twice daily). The specific combination (1, 2 or 3 agents)

was personalized based on the patient s initial IOP (e.g.,

starting with 2 or 3 agents for high IOP >35 mmHg),

contraindications (e.g., beta-blockers for patients without

asthma), and, most importantly, their real-time response to the

initial treatment (e.g., potentially adding or removing agents

based on efficacy and tolerance), as outlined in the stepwise

management protocol. In summary, while the available menu of drugs

was standardized (carteolol, brimonidine, brinzolamide), the final

regimen for each patient was tailored based on a clinical decision

that integrated the initial presentation, patient-specific factors

and the observed therapeutic response. The use of glucocorticoid

eyedrops (typically 1% prednisolone acetate, one drop 4-8 times

daily) was guided by the severity of anterior chamber inflammation

(usually 1% prednisolone acetate, one drop, 4-8 times daily) and

tailored at the physician s discretion until surgery, rather

than adhering to a fixed, standardized protocol for all

patients.

After 1 h, if the IOP had not decreased, 250 ml

intravenous mannitol drip and oral ocular hypotensive medication

were administered, provided no contraindications existed (e.g.,

severe renal impairment, progressive heart failure, electrolyte

imbalances preclude mannitol, sulfa allergy, electrolyte imbalances

preclude acetazolamide). If these measures failed to reduce the IOP

to the normal range, argon laser peripheral iridoplasty (ALPI) with

or without yttrium aluminum garnet laser peripheral iridotomy (LPI)

was performed. Once the IOP was adequately reduced, appropriate

anti-glaucoma surgery was carried out in patients who meet the

surgical indications (10) to

prevent recurrent elevated IOP. All patients with APAC ultimately

underwent anti-glaucoma surgery, which including one of the

following three procedures: i) PH combined with goniosynechialysis

(GSL), ii) PH combined with GSL plus gonioscopy-assisted

transluminal trabeculotomy (GATT) or endoscopic

cyclophotocoagulation (ECP) and iii) trabeculectomy with or without

PH.

All surgical procedures were performed by one of two

glaucoma specialists (JZ or YW). All included patients, regardless

of group, were examined and operated on using the same equipment

and by the same technicians or glaucoma specialists.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS

Statistics for Windows software (version 25.0; IBM Corp.).

Continuous variables are expressed as the mean ± standard

deviation, median (interquartile range) or median (range),

depending on the data distribution. Categorical variables are

presented as counts and percentages. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used

to assess data normality.

Best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) values were

converted to logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution (logMAR)

units for analysis. For BCVA of counting fingers or worse, the

following conversions were applied: Counting fingers, 2.0 logMAR;

hand movements, 2.3 logMAR; light perception, 2.6 logMAR; and no

light perception, 2.9 logMAR (13).

Students t-test was used to compare continuous

variables, such as demographic data, ocular characteristics,

treatments and outcomes between two groups, where appropriate.

Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare two groups of hierarchical

variables, such as the number of quadrants of anterior chamber

angle closure; and Chi-square or Fisher s exact tests were

used to compare categorical variables.

To account for inter-eye correlation, a generalized

estimating equation (GEE) was used to further validate the key

variables, namely ACD and lens thickness, that exhibited

significant differences.

All patients with APAC following COVID-19 were

further divided into two groups according to sex, age (≤65 and

>65 years) or laterality, and the differences in demographic

features, the characteristics of affected eyes, and treatment

options between the two groups were compared. Two-sided P<0.05

was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

Demographic and epidemiological

findings of all recruited patients with APAC

A total of 86 eyes (43 right and 43 left) from 78

patients with APAC (21 males and 57 females) were enrolled in the

post-COVID-19 group and another 50 eyes (28 right and 22 left) from

48 patients with APAC (16 males and 32 females) were enrolled in

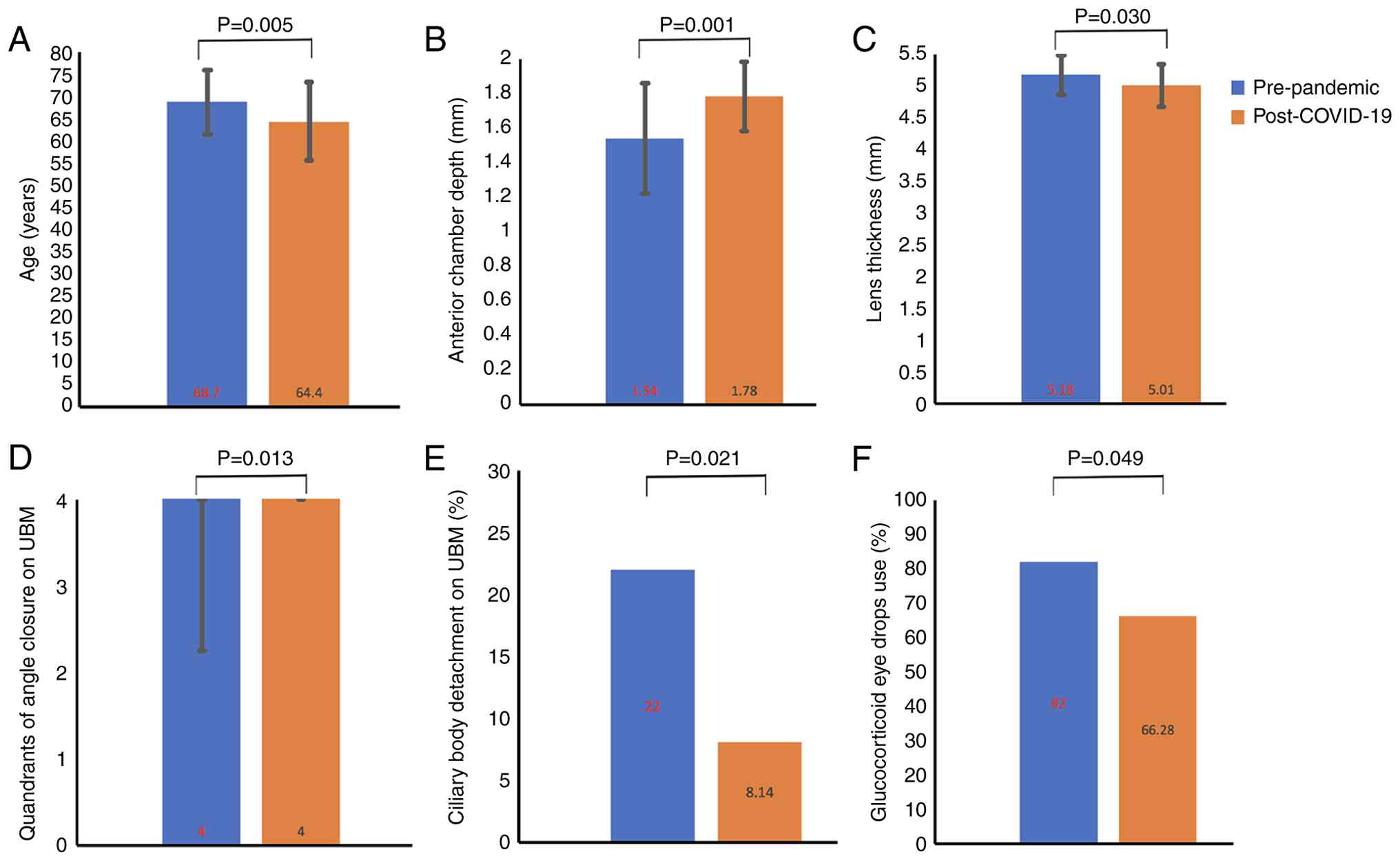

the pre-pandemic group. There was a significant difference in age

(64.4±8.8 vs. 68.7±7.2 years; P=0.005; Fig. 1A), but no statistically significant

difference in male percentage (26.92 vs. 33.33%; P=0.443) or

laterality distribution (right, 44.87%; left, 44.87%; both, 10.26%

vs. right, 54.17%; left, 41.67%; both 4.17%; P=0.370) between the

post-COVID-19 and pre-pandemic groups, respectively.

In the epidemiological analysis, 74.36% (58/78) of

the patients in the post-COVID-19 group experienced fever before

APAC onset. The median IFO was 1 day (range, 0-15 days) and the

median fever duration was 2 days (range, 0-4 days). Among patients

with fever, the maximum recorded body temperature was 39˚C and the

mean maximum body temperature was 38.26±0.56˚C. All 78 patients

manifested with either mild COVID-19 symptoms or were

asymptomatic.

When clinical manifestations and ocular structural

parameters were compared between the two groups, the post-COVID-19

group had a significantly greater ACD (1.78±0.20 vs. 1.54±0.32 mm;

P=0.001; Fig. 1B), thinner lens

(5.01±0.33 vs. 5.18±0.31 mm; P=0.030; Fig. 1C), more quadrants of angle closure

on UBM [4.00 (4.00-4.00) vs. 4.00 (2.25-4.00); P=0.013; Fig. 1D] and a lower prevalence of ciliary

body detachment (8.14 vs. 22.00%; P=0.021; Fig. 1E) compared with the pre-pandemic

group. By contrast, the post-COVID-19 and pre-pandemic groups had

similar median lens nucleus hardness gradings [2 (2-3) vs. 3 (2-3);

P=0.437], BCVA at first visit (1.28±0.77 vs. 1.49±0.80 logMAR;

P=0.336), axial length (AL; 22.35±0.73 vs. 22.37±0.59 mm; P=0.964),

maximum IOP (48.74±9.11 vs. 51.29±9.65 mmHg; P=0.319), prevalence

of glaucomatous subcapsular flecks (24.42 vs. 16.00%; P=0.248),

previous history of APAC (6.98 vs. 0.00%; P=0.140), pupil diameter

without any treatment (5.73±1.34 vs. 5.87±1.30 mm; P=0.715) and

corneal thickness (611.14±93.08 vs. 683.31±162.73 µm; P=0.106). The

demographic and clinical characteristics of all enrolled

participants with APAC and their affected eyes are summarized in

Table I.

| Table IDemographic, epidemiological and

clinical characteristics of all patients with APAC. |

Table I

Demographic, epidemiological and

clinical characteristics of all patients with APAC.

| | Group | |

|---|

| Baseline

characteristics | Pre-pandemic (n=48)

unfavorable group group 1 group 2 | Post-COVID-19

(n=78) | P-value |

|---|

| Males | 16 (33.33) | 21 (26.92) | 0.443 |

| Age, years | 68.7±7.2 | 64.4±8.8 | 0.005 |

| Laterality | | | 0.370 |

|

Right | 26 (54.17) | 35 (44.87) | |

|

Left | 20 (41.67) | 35 (44.87) | |

|

Both | 2 (4.17) | 8 (10.26) | |

| Fever | - | 58 (74.36) | |

| Maximum body

temperature,˚C | - | 38.26±0.56 | |

| IFO,

daysa | - | 1 (0-15) | |

| Fever duration,

daysa | - | 2 (0-4) | |

| No. of affected

eyes | 50 | 86 | |

| ACD, mm | 1.54±0.32 | 1.78±0.20 | 0.001 |

| Lens thickness,

mm | 5.18±0.31 | 5.01±0.33 | 0.030 |

| Lens nucleus

hardness, gradeb | 3 (2-3) | 2 (2-3) | 0.437 |

| BCVA at first

visit, logMAR | 1.49±0.80 | 1.28±0.77 | 0.336 |

| AL, mm | 22.37±0.59 | 22.35±0.73 | 0.964 |

| Maximum IOP,

mmHg | 51.29±9.65 | 48.74±9.11 | 0.319 |

| Glaucomatic

subcapsular flecks | 8 (16.00) | 21 (24.42) | 0.248 |

| Previous history of

APAC | 0 (0) | 6 (6.98) | 0.140 |

| PD without any

treatments, mm | 5.87±1.30 | 5.73±1.34 | 0.715 |

| Corneal thickness,

µm | 683.31±162.73 | 611.14±93.08 | 0.106 |

| Ciliary body

detachment on UBM | 11 (22.00) | 7 (8.14) | 0.021 |

| Quadrants of angle

closure on UBMb | 4.00

(2.25-4.00) | 4.00

(4.00-4.00) | 0.013 |

| Treatments | | | |

|

Glucocorticoid

eye drops | 41 (82.00) | 57 (66.28) | 0.049 |

|

ALPI | 4 (8.00) | 3 (3.49) | 0.456 |

|

LPI | 0 (0) | 3 (3.49) | 0.465 |

|

ALPI +

LPI | 0 (0) | 3 (3.49) | 0.465 |

|

PH +

GSL | 19 (38.00) | 33 (38.37) | 0.966 |

|

PH + GSL +

ECP/GATT | 18 (36.00) | 28 (32.56) | 0.682 |

|

Trabeculectomy | 13 (26.00) | 25 (29.07) | 0.700 |

In the comparison of ACD and lens thickness between

the two groups, Students t-test showed a significant

difference. However, since some patients contributed both eyes to

the analysis, GEEs were used to account for inter-eye correlation.

For ACD, the GEE analysis confirmed a significant group effect

(Wald Chi-square, 13.647; P<0.001), with no significant effect

of laterality (Wald Chi-square, 0.005; P=0.943) or group x

laterality interaction (Wald Chi-square, 0.313; P=0.576). After

removing the non-significant group x laterality interaction term,

GEE analysis revealed that the group effect remained significant

(Wald Chi-square, 13.208; P<0.001), while laterality remained

non-significant (Wald Chi-square, 0.128; P=0.720). In the

comparison of lens thickness between the two groups, GEE analysis

also showed a significant group effect (Wald Chi-square, 6.257;

P=0.012), with non-significant laterality (Wald Chi-square, 1.277;

P=0.258) and group x laterality interaction (Wald Chi-square,

3.040; P=0.081). After removing the group x laterality interaction,

further GEE revealed that the group effect remained significant

(Wald Chi-square, 5.421; P=0.020) and laterality remained

non-significant (Wald Chi-square, 0.172; P=0.678).

Comparison of drug, laser and surgical

treatment methods between the post-COVID-19 and pre-pandemic

groups

In the comparison of treatment methods, the

proportion of cases treated in with glucocorticoid eyedrops in the

post-COVID-19 group was lower than that in the pre-pandemic group

(66.28 vs. 82.00%; P=0.049; Fig.

1F). However, there were no significant differences in the

proportions of patients treated with ALPI (3.49 vs. 8.00%;

P=0.456), LPI (3.49 vs. 0.00%; P=0.465), ALPI combined with LPI

(3.49 vs. 0.00%; P=0.465), PH combined with GSL (38.37 vs. 38.00%;

P=0.966), PH combined with GSL and either ECP or GATT (32.56 vs.

36.00%; P=0.682) and trabeculectomy with or without PH (29.07 vs.

26.00%; P=0.700) between the post-COVID-19 and pre-pandemic groups,

respectively. The detailed treatment methods of all participants

and affected eyes are summarized in Table I.

Comparison of demographic and clinical

characteristics between the sexes

All patients with APAC following COVID-19 were

divided into male (22 eyes from 21 men) and female (64 eyes from 57

women) groups according to sex. Analysis revealed that the female

group had a shallower ACD (1.74±0.18 vs. 1.86±0.24 mm; P=0.048),

higher BCVA at first visit (1.36±0.76 vs. 0.94±0.74 logMAR;

P=0.031) and shorter AL (22.22±0.69 vs. 22.92±0.59 mm; P=0.001).

However, no significant differences between the male and female

groups were detected for any other clinical features or treatments.

A comparison of the demographic and clinical characteristics

between male and female patients following COVID-19 is presented in

Table II.

| Table IIComparison of demographic and

clinical characteristics between males and females with APAC

following COVID-19. |

Table II

Comparison of demographic and

clinical characteristics between males and females with APAC

following COVID-19.

| | Group | |

|---|

| Baseline

characteristics | Male (n=21) | Female (n=57) | P-value |

|---|

| Age, years | 62.5±10.2 | 64.9±8.6 | 0.328 |

| Laterality | | | 0.349 |

|

Right | 8 (38.10) | 27 (47.37) | |

|

Left | 12 (57.14) | 23 (40.35) | |

|

Both | 1 (4.76) | 7 (12.28) | |

| Fever | 16 (76.19) | 42 (73.68) | 0.822 |

| Maximum body

temperature,˚C | 38.36±0.47 | 38.22±0.59 | 0.548 |

| IFO,

daysa | 1 (0-10) | 1 (0-15) | 0.581 |

| Fever duration,

daysa | 1 (0-3) | 2 (0-4) | 0.160 |

| No. of affected

eyes | 22 | 64 | |

| ACD, mm | 1.86±0.24 | 1.74±0.18 | 0.048 |

| Lens thickness,

mm | 5.14±0.27 | 4.97±0.36 | 0.117 |

| Lens nucleus

hardness, gradeb | 2 (2-3) | 2 (2-3) | 0.293 |

| BCVA at first

visit, log MAR | 0.94±0.74 | 1.36±0.76 | 0.031 |

| AL, mm | 22.92±0.59 | 22.22±0.69 | 0.001 |

| Maximum IOP,

mmHg | 48.39±7.95 | 48.89±9.76 | 0.851 |

| Glaucomatic

subcapsular flecks | 3 (13.64) | 18 (28.13) | 0.172 |

| Previous history of

APAC | 2 (9.09) | 4 (6.25) | 1.000 |

| PD without any

treatments, mm | 5.82±1.30 | 5.71±1.34 | 0.781 |

| Corneal thickness,

µm | 617.07±73.99 | 615.00±104.72 | 0.946 |

| Ciliary body

detachment on UBM | 0 (0) | 7 (10.94) | 0.243 |

| Quadrants of angle

closure on UBMb | 4.00

(3.75-4.00) | 4.00

(4.00-4.00) | 0.685 |

| Treatments | | | |

|

Glucocorticoid

eye drops | 17 (77.27) | 40 (62.50) | 0.206 |

|

PH +

GSL | 8 (36.36) | 25 (39.06) | 0.822 |

|

PH + GSL +

ECP/GATT | 7 (36.00) | 21 (32.56) | 0.932 |

|

Trabeculectomy | 7 (31.82) | 18 (28.13) | 0.742 |

Comparison of demographic and clinical

features by age and laterality

Analysis by age group showed that patients aged

>65 years (42 eyes from 39 cases) developed APAC at a median

time of 1 day (range, 0-15 days) after COVID-19-induced fever,

while patients aged ≤65 years (44 eyes from 39 cases) had a

significantly longer median APAC development time of 2 days (range,

0-15 days) (P=0.023). In addition, the older patients had a

shallower ACD (1.76±0.18 vs. 1.79±0.22 mm; P=0.030), thicker lens

(5.17±0.27 vs. 4.87±0.34 mm; P=0.001), harder lens nucleus [3 (3-3)

vs. 2 (2-2); P<0.001] and a higher incidence of ciliary body

detachment on UBM (16.67 vs. 0.00%; P=0.015) than younger patients.

They also had a higher frequency of treatment with glucocorticoid

eyedrops (80.95 vs. 52.27%; P=0.005), or PH combined with GSL plus

either ECP or GATT (45.24 vs. 20.45%; P=0.014), and fewer

trabeculectomies with or without PH (19.05 vs. 38.64%; P=0.014). A

detailed comparison of the demographic and clinical features by age

grouping is shown in Table

III.

| Table IIIComparison of demographic and

clinical characteristics between two age groups of patients with

APAC following COVID-19. |

Table III

Comparison of demographic and

clinical characteristics between two age groups of patients with

APAC following COVID-19.

| | Group | |

|---|

| Baseline

characteristics | ≤65 years

(n=39) | 65 years

(n=39) | P-value |

|---|

| Laterality | | | 0.479 |

|

Right | 19 (48.72) | 16 (41.03) | |

|

Left | 15 (38.46) | 20 (51.28) | |

|

Both | 5 (12.82) | 3 (7.69) | |

| Fever | 30 (76.92) | 28 (71.79) | 0.604 |

| Maximum body

temperature,˚C | 38.34±0.63 | 38.16±0.47 | 0.350 |

| IFO,

daysa | 2 (0-15) | 1 (0-15) | 0.023 |

| Fever duration,

daysa | 1 (0-3) | 1 (0-4) | 0.787 |

| No. of affected

eyes | 44 | 42 | |

| ACD, mm | 1.79±0.22 | 1.76±0.18 | 0.030 |

| Lens thickness,

mm | 4.87±0.34 | 5.17±0.27 | 0.001 |

| Lens nucleus

hardness, gradeb | 2 (2-2) | 3 (3-3) | <0.001 |

| BCVA at first

visit, logMAR | 1.31±0.79 | 1.26±0.76 | 0.847 |

| AL, mm | 22.34±0.71 | 22.46±0.75 | 0.519 |

| Maximum IOP,

mmHg | 50.90±8.12 | 48.17±10.04 | 0.272 |

| Glaucomatic

subcapsular flecks | 13 (29.55) | 8 (19.05) | 0.257 |

| Previous history of

APAC | 1 (2.27) | 5 (11.90) | 0.184 |

| PD without any

treatments, mm | 5.78±1.25 | 5.81±1.48 | 0.921 |

| Corneal thickness,

µm | 621.74±0.39 | 608.85±105.57 | 0.625 |

| Ciliary body

detachment on UBM | 0 (0) | 7 (16.67) | 0.015 |

| Quadrants of angle

closure on UBMb | 4.00

(4.00-4.00) | 4.00

(3.00-4.00) | 0.067 |

| Treatments | | | |

|

Glucocorticoid

eyedrops | 23 (52.27) | 34 (80.95) | 0.005 |

|

PH +

GSL | 18 (40.91) | 15 (35.71) | 0.620 |

|

PH + GSL +

ECP/GATT | 9 (20.45) | 19 (45.24) | 0.014 |

|

Trabeculectomy | 17 (38.64) | 8 (19.05) | 0.046 |

Finally, a comparison was performed according to

laterality (43 eyes in both the from right and left groups). The

results revealed no significant differences between these groups

for all eye structure parameters and treatment options. A detailed

comparison of demographic and clinical features by laterality

grouping is presented in Table

IV.

| Table IVComparison of clinical

characteristics between eyes affected with APAC following

COVID-19. |

Table IV

Comparison of clinical

characteristics between eyes affected with APAC following

COVID-19.

| | Group by

laterality | |

|---|

| Baseline

characteristics | Right | Left | P-value |

|---|

| No. of affected

eyes | 43 | 43 | |

| ACD, mm | 1.76±0.18 | 1.80±0.23 | 0.427 |

| Lens thickness,

mm | 5.03±0.36 | 4.98±0.30 | 0.612 |

| Lens nucleus

hardness, gradea | 2 (2-3) | 2 (2-3) | 0.842 |

| BCVA at first

visit, logMAR | 1.30±0.74 | 1.28±0.81 | 0.931 |

| AL, mm | 22.38±0.66 | 22.33±0.83 | 0.821 |

| Maximum IOP,

mmHg | 48.29±10.39 | 49.28±7.46 | 0.633 |

| Glaucomatic

subcapsular flecks | 11 (25.58) | 10 (23.26) | 0.802 |

| Previous history of

APAC | 2 (4.65) | 4 (9.30) | 0.672 |

| PD without any

treatments, mm | 5.77±1.46 | 5.69±1.14 | 0.8022 |

| Corneal thickness,

µm | 617.60±94.78 | 603.07±91.99 | 0.542 |

| Ciliary body

detachment on UBM | 3 (6.98) | 4 (9.30) | 1.000 |

| Quadrants of angle

closure on UBMb | 4.00

(1.00-4.00) | 4.00

(0.00-4.00) | 0.767 |

| Treatments | | | |

|

Glucocorticoid

eye drops | 30 (69.77) | 27 (62.79) | 0.494 |

|

PH +

GSL | 16 (37.21) | 17 (39.53) | 0.825 |

|

PH + GSL +

ECP/GATT | 12 (27.91) | 16 (37.21) | 0.357 |

|

Trabeculectomy | 15 (34.88) | 10 (23.26) | 0.235 |

Discussion

In clinical practice, it was observed that the

two-month period from December 1, 2022 to January 31, 2023, when

the Omicron variant of COVID-19 was most prevalent in China, the

number of emergency cases of APAC increased markedly compared with

that between December 1, 2018 and January 31, 2019. Similarly,

during the COVID-19 epidemic in India, the number of emergency

glaucoma cases increased by 62.4% (14), further suggesting a possible

association between the prevalence of COVID-19 and the increased

presentation of acute ocular emergencies, including APAC.

Among patients with COVID-19, conjunctivitis is the

most common ocular manifestation, with blurred vision occurring in

4.8-12.8% of cases (15). By

contrast, APAC following SARS-CoV-2 infection not only presents

with conjunctival congestion resembling conjunctivitis, but is also

accompanied by eyelid swelling, vision loss and increased IOP.

Therefore, it poses a serious threat to visual health and warrants

greater attention from ophthalmologists. However, the exact

association between COVID-19 and APAC remains unclear.

The present study revealed that following COVID-19

exposure, APAC occurred in younger individuals than during the

pre-pandemic period (64.4±8.8 vs. 68.7±7.2 years; P=0.005), and the

patients had mild or asymptomatic infections. Similar age-related

trends have been reported for other diseases following COVID-19.

For example, Ashkenazy et al (16) described 12 cases of retinal venous

obstruction without hypertension, diabetes, glaucoma, underlying

hypercoagulable states or other common risk factors, all of whom

were under 50 years of age, and Fonollosa et al (17) reported 15 cases of retinal vein

occlusion following COVID-19 with a median age of onset of 39

years. However, Wu et al (18) observed that conjunctivitis

following COVID-19 was more common in patients with more severe

COVID-19 symptoms, and Romero-Castro et al (19) reported that among 117 cases of

severe COVID-19 there were 43 cases with abnormal ocular

manifestations. These reports suggest that while APAC following

COVID-19 is more common in patients with milder infections, the

influence of COVID-19 on the presentation of various ocular

conditions differs depending on disease type and infection

severity.

The time intervals between COVID-19 diagnosis and

the onset of various COVID-19 related diseases are known to differ.

For example, a study revealed that in patients who eventually died,

elevations in blood urea nitrogen and serum creatinine typically

occurred within 28 days following COVID-19 diagnosis (20). The peak incidence of

COVID-19-associated retinal venous occlusion has been reported to

be 6-8 weeks after infection onset (21). In addition, a case of panuveitis

and optic neuritis occurred ~2 weeks after SARS-CoV-2 infection in

60-year-old woman (22), while a

30-year-old man developed acute conjunctivitis in both eyes 13 days

after infection, with SARS-CoV-2 RNA detected in the conjunctival

secretions (23). It may be

inferred from these reports that acute inflammatory reactions

following COVID-19 usually occur within 1 month, particularly

within 2 weeks of infection. Similarly, in the present study, APAC

following COVID-19 developed within 15 days after the onset of

fever, with a median IFO of 1 day. This suggests that APAC onset

following COVID-19 may be associated with the acute inflammatory

reaction caused by SARS-CoV-2.

COVID-19 has been shown to cause extensive vascular

abnormalities in the conjunctiva, choroid and retina. Abdelmassih

et al (24) reported a

group of 14 patients with severe COVID-19, all of whom exhibited

abnormal choroidal angiography. Other studies have reported a

higher susceptibility of the retinal vein to occlusion and reduced

retinal thickness following COVID-19 (15,21,25).

In the present study, it was observed that cases with APAC

following COVID-19 had a greater ACD (1.78±0.20 vs. 1.54±0.32 mm;

P=0.001), thinner lens (5.01±0.33 vs. 5.18±0.31; P=0.030) and more

quadrants of angle closure [4.00 (4.00-4.00) vs. 4.00 (2.25-4.00);

P=0.013] on UBM than those in the pre-pandemic time period. These

findings suggest that APAC following COVID-19 may involve distinct

ocular characteristics and different risk factors than those

observed in pre-pandemic APAC cases (26).

While the post-COVID-19 group had a significantly

deeper average ACD than the pre-pandemic group, the values still

fell within the category of shallow ACD (defined as ACD <2.8 mm)

(27). This suggests that COVID-19

may act as a precipitating factor in eyes with pre-existing shallow

ACD, rather than serving as an independent risk factor for APAC;

specifically, COVID-19 infection may unmask or accelerate APAC in

susceptible individuals. We hypothesize that extended indoor

sedentary activities and reduced sunlight exposure during the

Omicron outbreak may have contributed to the risk of APAC in

SARS-CoV-2-positive patients. There is extensive literature on the

association between APAC onset and environmental factors (28-31).

Teikari et al (28,29) reported that fewer hours of sunshine

were associated with a higher incidence of APAC, and several

studies have reported a higher risk of APAC onset in December than

at other times of the year (29-31).

Coincidentally, the Omicron outbreak in China occurred between

December 1, 2022 and January 31, 2023, when there was little

sunshine and patients spent a larger proportion of time indoors,

thereby increasing the risk of APAC.

Apart from two cases that used 0.2 g ibuprofen for

self-management of myalgia, the vast majority of patients in the

present study with APAC following COVID-19 infection did not

receive any treatment for COVID-19 prior to enrollment, effectively

ruling out the possibility that COVID-19 treatment measures induced

APAC. In addition, the patients with APAC following COVID-19

exhibited a greater ACD and larger number of quadrants with angle

closure compared with those in pre-pandemic cases. This suggests

that the inflammatory response caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection may

serve as an additional induction factor for APAC. The possible

mechanisms underlying this may involve a combined effect involving

both anterior chamber angle blockage and inflammation, rather than

being solely attributable to pupillary block.

Another difference between the two groups of

patients with APAC was that patients with COVID-19-associated APAC

were less prone to ciliary body detachment on UBM (8.14 vs. 22.00%;

P=0.021) and less likely to use glucocorticoid eyedrops (66.28 vs.

82.00%; P=0.049). The reduced requirement for glucocorticoid

eyedrops in the post-COVID-19 group may indicate less disruption of

the blood-aqueous barrier, milder anterior chamber inflammation or

earlier intervention. These findings suggest a distinct

inflammatory profile in COVID-19-associated APAC that could

influence clinical management.

In the subgroup analysis of COVID-19-associated APAC

according to sex, female patients comprised a larger proportion of

the cohort (73.08%) than male patients (26.92%). The female

patients had a shallower ACD (1.74±0.18 vs. 1.86±0.24 mm; P=0.048),

poorer BCVA at first visit (1.36±0.76 vs. 0.94±0.74 log MAR;

P=0.031) and shorter AL (22.22±0.69 vs. 22.92±0.59; P=0.001). These

findings are consistent with previously reported pre-pandemic risk

factors for APAC (26,32-34),

which indicates that the presence of COVID-19 did not alter the

difference in clinical characteristics of APAC and treatment

methods between the sexes.

In the subgroup analysis by age, elderly patients

(>65 years) exhibited a significantly shallower ACD, thicker

lens and harder lens nucleus compared with those in younger

patients. APAC developed in elderly patients at a median IFO of 1

day after fever compared with 2 days in younger patients. These

findings suggest that older patients with pre-existing risk factors

may develop APAC more rapidly following COVID-19. Therefore, it is

necessary to be aware of the risk of APAC following COVID-19 in

elderly patients with APAC-related ocular characteristics. Another

difference observed between two age groups was the choice of

treatment methods. The older patients more frequently received

glucocorticoid eyedrops (80.95 vs. 52.27%; P=0.005), which may

reflect more severe damage of the blood-aqueous barrier. They also

were more frequently treated with PH combined with GSL and either

ECP or GATT (45.24 vs. 20.45%; P=0.014), reflecting more severe

lens opacity. By contrast, younger patients more frequently

underwent trabeculectomy with or without PH (38.64 vs. 19.05%;

P=0.014), likely due to having more quadrants of angle closure on

UBM [4.00 (4.00-4.00) vs. 4.00 (3.00-4.00); P=0.067] but milder

lens changes.

The present study is the first to describe in detail

the clinical characteristics of APAC following COVID-19 during the

Omicron outbreak in China, serving as a reference for the diagnosis

and treatment of patients with APAC during an epidemic outbreak.

However, the study has some limitations. These include its

retrospective, non-randomized design, and the lack of measurement

of systemic inflammatory markers, such as CRP or IL-6, or vitamin D

levels. This limits its ability to support a causal relationship

between COVID-19 and APAC through these pathways or to identify

predictive indicators. In addition, comparing patients from

different time periods may introduce selection bias due to

seasonal, environmental or healthcare variations. To minimize these

effects on COVID-19 as the primary factor under investigation, data

from the same months in the preceding year were used for

comparison. Although this may have introduced some bias, potential

confounding effects were mitigated by maintaining consistency in

equipment, surgical personnel and examiners in both groups.

However, variations in the duration of winter sunshine exposure

between years cannot be excluded. The analysis of patients from

different time periods was necessary as the availability of control

patients over the pandemic period was limited, resulting in an

insufficient sample size of patients without COVID-19 due to the

high infectivity of SARS-CoV-2. Furthermore, patients with APAC

following COVID-19 were younger than those without COVID-19. As no

data on the total number of patients with COVID-19 are available,

it was not possible to determine whether this age difference

reflects an increased susceptibility of younger individuals to

SARS-CoV-2 or a larger population base of younger COVID-19

patients. Moreover, all participants were of Chinese Han ethnicity,

so it is not clear whether the conclusions of the study can be

generalized to other races or nationalities. Finally, due to

limited detection methods, it was not possible to obtain evidence

of the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in the intraocular fluid. Therefore,

the possibility of concurrent intraocular infections in patients

with APAC following SARS-CoV-2 infection cannot be excluded.

In conclusion, patients with APAC following COVID-19

during the Omicron wave presented with a greater ACD compared with

that observed in patients with APAC prior to the pandemic, although

both were within the clinically shallow range. This suggests a

potential pathophysiological mechanism involving both anterior

chamber angle obstruction and inflammatory processes, possibly

triggered by SARS-CoV-2 infection, rather than pure pupillary

block. Ophthalmologists should maintain a high level of vigilance

for APAC in patients post-COVID-19 infection, even in those with

only moderately shallow ACD, and pay particular attention to

individuals with pre-existing anatomic risk factors. However, these

recommendations should be interpreted with caution given the

retrospective design of the study, as well as the single-center

origin and unmeasured potential confounding factors of the

patients. Further large-scale, prospective, multi-center studies

are warranted to validate these observations. These limitations

will be addressed in future research.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors contributions

SS, YX, and JZ conceived and planned the study and

wrote the manuscript. YX, YW and LZ acquired the data. SS, YW and

JZ analyzed the data, and participated in manuscript discussion and

revision. SS conducted statistical analysis of the data. YX and LZ

checked and confirmed the authenticity of all the raw data. All

authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The study was approved by the Institutional Review

Board of Xiamen Eye Center (Xiamen, China; approval no.

XMYKZX-KY-2023-003) and was conducted in accordance with the tenets

of the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided written

informed consent to participate.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Authors information

Dr Shancheng Si: ORCID:0009-0003-9159-7972.

References

|

1

|

Pan Y, Wang L, Feng Z, Xu H, Li F, Shen Y,

Zhang D, Liu WJ, Gao GF and Wang Q: Characterisation of SARS-CoV-2

variants in Beijing during 2022: An epidemiological and

phylogenetic analysis. Lancet. 401:664–672. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Soman M, Indurkar A, George T, Sheth JU

and Nair U: Rapid onset neovascular glaucoma due to

COVID-19-related retinopathy. J Curr Glaucoma Pract. 16:136–140.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Chen L, Deng C, Chen X, Zhang X, Chen B,

Yu H, Qin Y, Xiao K, Zhang H and Sun X: Ocular manifestations and

clinical characteristics of 535 cases of COVID-19 in Wuhan, China:

A cross-sectional study. Acta Ophthalmol. 98:e951–e959.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Zhang Y and Stewart JM: Retinal and

choroidal manifestations of COVID-19. Curr Opin Ophthalmol.

32:536–540. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Zhou L, Wu S, Wang Y, Bao X, Peng T, Luo W

and Ortega-Usobiaga J: Clinical presentation of acute primary angle

closure during the COVID-19 epidemic lockdown. Front Med

(Lausanne). 9(1078237)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Barosco G, Morbio R, Chemello F, Tosi R

and Marchini G: Bilateral angle-closure during hospitalization for

coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19): A case report. Eur J Ophthalmol.

32:NP75–NP82. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Au SCL: From acute angle-closure to

COVID-19 during Omicron outbreak. Vis J Emerg Med.

29(101514)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Tejwani S, Angmo D, Nayak BK, Sharma N,

Sachdev MS, Dada T and Sinha R: Prepared in Association with the

AIOS and GSI Expert Group; Composition of the All India

Ophthalmological Society (AIOS) and Glaucoma Society of India (GSI)

Expert Group includes the Writing Committee (as listed) and the

following members. Devindra Sood, et al: Preferred practice

guidelines for glaucoma management during COVID-19 pandemic. Indian

J Ophthalmol. 68:1277–1280. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Pujari R, Chan G and Tapply I:

Addenbrookes Glaucoma COVID response consortium and Bourne RR. The

impacts of COVID-19 on glaucoma patient outcomes as assessed by

POEM. Eye (Lond). 36:653–655. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Zhou W, Lin H, Ren Y, Lin H, Liang Y, Chen

Y and Zhang S: Mental health and self-management in glaucoma

patients during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study in

China. BMC Ophthalmol. 22(474)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Chylack LT Jr, Wolfe JK, Singer DM, Leske

MC, Bullimore MA, Bailey IL, Friend J, McCarthy D and Wu SY: The

lens opacities classification system III. The longitudinal study of

cataract study group. Arch Ophthalmol. 111:831–836. 1993.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Gao X, Lv A, Lin F, Lu P, Zhang Y, Song W,

Zhu X, Zhang H, Liao M, Song Y, et al: Efficacy and safety of

trabeculectomy versus peripheral iridectomy plus goniotomy in

advanced primary angle-closure glaucoma: Study protocol for a

multicentre, non-inferiority, randomised controlled trial (the TVG

study). BMJ Open. 12(e 062441)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Niederer RL, Sharief L, Tomkins-Netzer O

and Lightman SL: Uveitis in sarcoidosis-clinical features and

comparison with other non-infectious uveitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm.

31:367–373. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Rajendrababu S, Durai I, Mani I, Ramasamy

KS, Shukla AG and Robin AL: Urgent and emergent glaucoma care

during the COVID-19 pandemic: An analysis at a tertiary care

hospital in South India. Indian J Ophthalmol. 69:2215–2221.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Sen M, Honavar SG, Sharma N and Sachdev

MS: COVID-19 and eye: A review of ophthalmic manifestations of

COVID-19. Indian J Ophthalmol. 69:488–509. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Ashkenazy N, Patel NA, Sridhar J, Yannuzzi

NA, Belin PJ, Kaplan R, Kothari N, Benitez Bajandas GA, Kohly RP,

Roizenblatt R, et al: Hemi- and central retinal vein occlusion

associated with COVID-19 infection in young patients without known

risk factors. Ophthalmol Retina. 6:520–530. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Fonollosa A, Hernández-Rodríguez J,

Cuadros C, Giralt L, Sacristán C, Artaraz J, Pelegrín L,

Olate-Pérez Á, Romero R, Pastor-Idoate S, et al: Characterizing

COVID-19-related retinal vascular occlusions: A case series and

review of the literature. Retina. 42:465–475. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Wu P, Duan F, Luo C, Liu Q, Qu X, Liang L

and Wu K: Characteristics of ocular findings of patients with

coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Hubei Province, China. JAMA

Ophthalmol. 138:575–578. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Romero-Castro RM, Ruiz-Cruz M, Alvarado-de

la Barrera C, González-Cannata MG, Luna-Villalobos YA,

García-Morales AK, Ablanedo-Terrazas Y, González-Navarro M and

Ávila-Ríos S: Posterior segment ocular findings in critically ill

patients with COVID-19. Retina. 42:628–633. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Liu YM, Xie J, Chen MM, Zhang X, Cheng X,

Li H, Zhou F, Qin JJ, Lei F, Chen Z, et al: Kidney function

indicators predict adverse outcomes of COVID-19. Med. 2:38–48.e2.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Modjtahedi BS, Do D, Luong TQ and Shaw J:

Changes in the incidence of retinal vascular occlusions after

COVID-19 Diagnosis. JAMA Ophthalmol. 140:523–527. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Benito-Pascual B, Gegúndez JA, Díaz-Valle

D, Arriola-Villalobos P, Carreño E, Culebras E, Rodríguez-Avial I

and Benitez-Del-Castillo JM: Panuveitis and optic neuritis as a

possible initial presentation of the novel coronavirus disease 2019

(COVID-19). Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 28:922–925. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Chen L, Liu M, Zhang Z, Qiao K, Huang T,

Chen M, Xin N, Huang Z, Liu L, Zhang G and Wang J: Ocular

manifestations of a hospitalised patient with confirmed 2019 novel

coronavirus disease. Br J Ophthalmol. 104:748–751. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Abdelmassih Y, Azar G, Bonnin S, Scemama

Timsit C, Vasseur V, Spaide RF, Behar-Cohen F and Mauget-Faysse M:

COVID-19 associated choroidopathy. J Clin Med.

10(4686)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Kanra AY, Altınel MG and Alparslan F:

Evaluation of retinal and choroidal parameters as neurodegeneration

biomarkers in patients with post-covid-19 syndrome. Photodiagnosis

Photodyn Ther. 40(103108)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Wang L, Huang W, Huang S, Zhang J, Guo X,

Friedman DS, Foster PJ and He M: Ten-year incidence of primary

angle closure in elderly Chinese: The Liwan Eye Study. Br J

Ophthalmol. 103:355–360. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Qian T, Du J, Ren R, Zhou H, Li H, Zhang Z

and Xu X: Vault-Correlated efficacy and safety of implantable

collamer lens V4c implantation for myopia in patients with shallow

anterior chamber depth. Ophthalmic Res. 66:445–456. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Teikari JM, O Donnell J, Nurminen M

and Raivio I: Acute closed angle glaucoma and sunshine. J Epidemiol

Community Health. 45:291–293. 1991.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Teikari J, Raivio I and Nurminen M:

Incidence of acute glaucoma in Finland from 1973 to 1982. Graefes

Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 225:357–360. 1987.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

David R, Tessler Z and Yassur Y:

Epidemiology of acute angle-closure glaucoma: Incidence and

seasonal variations. Ophthalmologica. 191:4–7. 1985.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Mehta SK, Mir T, Freedman IG, Sheth AH,

Sarrafpour S, Liu J and Teng CC: Emergency department presentations

of acute primary angle closure in the United States from 2008 to

2017. Clin Ophthalmol. 16:2341–2351. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Zhang X, Liu Y, Wang W, Chen S, Li F,

Huang W, Aung T and Wang N: Why does acute primary angle closure

happen? Potential risk factors for acute primary angle closure.

Surv Ophthalmol. 62:635–647. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Li M, Chen Y, Jiang Z, Chen X, Chen J and

Sun X: What are the characteristics of primary angle closure with

longer axial length? Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 59:1354–1359.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Choudhari NS, Khanna RC, Marmamula S,

Mettla AL, Giridhar P, Banerjee S, Shekhar K, Chakrabarti S, Murthy

GVS, Gilbert C and Rao GN: Andhra Pradesh eye disease study group.

Fifteen-Year incidence rate of primary angle closure disease in the

Andhra Pradesh eye disease study. Am J Ophthalmol. 229:34–44.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|