Introduction

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are rare in the context of all tumor types, with the incidence of GIST varying among different countries; however, there has been a gradual escalating trend over time (1-3). The global average incidence of GIST ranges from 1-2 per 100,000 person-years (4), whereas in China, it is ~0.40 per 100,000 person-years (5). In addition, GIST is the most common neoplasm originating from the gastrointestinal mesenchymal tissue (6), most commonly in the stomach, followed by the small intestine, colon, rectum and esophagus (7); the incidence of GIST at the esophagogastric junction is <1% (8). In previous years, the majority of GIST cases were initially misdiagnosed as leiomyoma or leiomyosarcoma, neurofibroma or neurilemmoma (4,9), and it was not until KIT (CD117), an immune marker specific to GIST, was discovered in the early 2000s, that GIST could be accurately diagnosed (9).

GISTs are typically identified during gastroscopy or computed tomography (CT) scan and usually appear as subepithelial lesions (SELs) on gastroscopy. SEL is a protrusion formation of the gastrointestinal tract (10), which typically originates from the deeper mucosa, being covered by epithelium, including GISTs, leiomyomas, neurilemmomas and lipomas (11). Leiomyoma is most common in the esophagus (12,13), and gastric leiomyoma is relatively uncommon; however, when present, it is most likely to occur in the cardia (14). Typically, GISTs and leiomyomas are viewed as different tumor categories that demonstrate no significant relationship.; however, the present study provided evidence that they can coexist.

The present report describes the rare co-occurrence of GIST and gastric leiomyoma in the same SEL at the cardia, and summarizes the clinicopathological and gene mutation characteristics, offering new insights and potential experience for the diagnosis and management of this condition. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report on both GIST and gastric leiomyoma occurring in the same SEL at the gastric cardia.

Case report

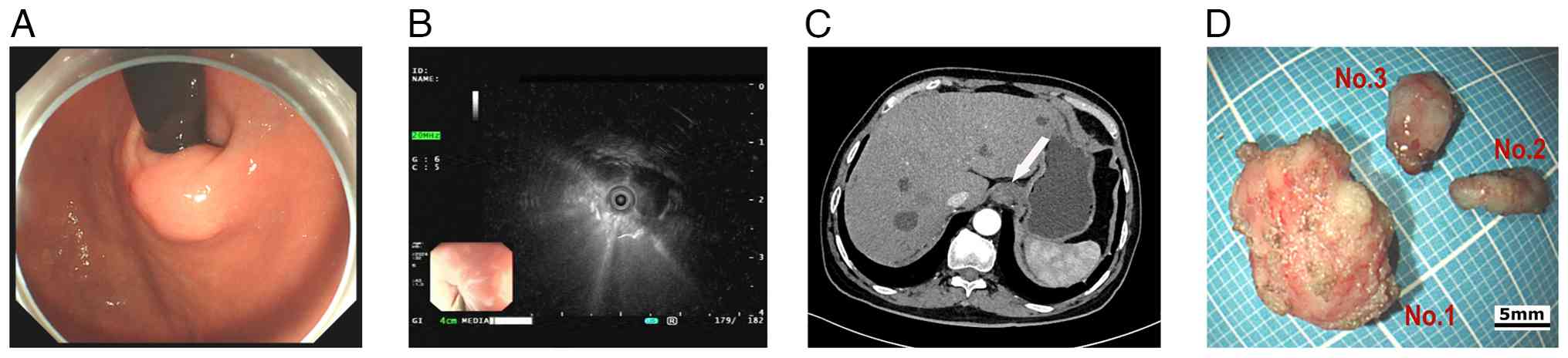

A 72-year-old male patient with a history of type 2 diabetes, hypertension, acute pancreatitis and a pancreatic pseudocyst underwent a gastroscopy examination at Sichuan Science City Hospital (Mianyang, China) without presenting with any symptoms during a physical examination in June 2024. Physical examination showed mild upper abdominal tenderness, and the psychosocial and family medical histories of the patient were unremarkable. Gastroscopy identified chronic gastritis and a 15-mm SEL in the cardia (Fig. 1A); consequently, endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) revealed the lesion originated from the muscularis propria, appearing as a heterogeneous hypoechoic mass with internal septa, which measured 13.9x9.2 mm (Fig. 1B). The CT scan showed a slightly thickened 15-mm nodule in the cardia with slight homogeneous enhancement and no signs of infiltration or metastasis (Fig. 1C).

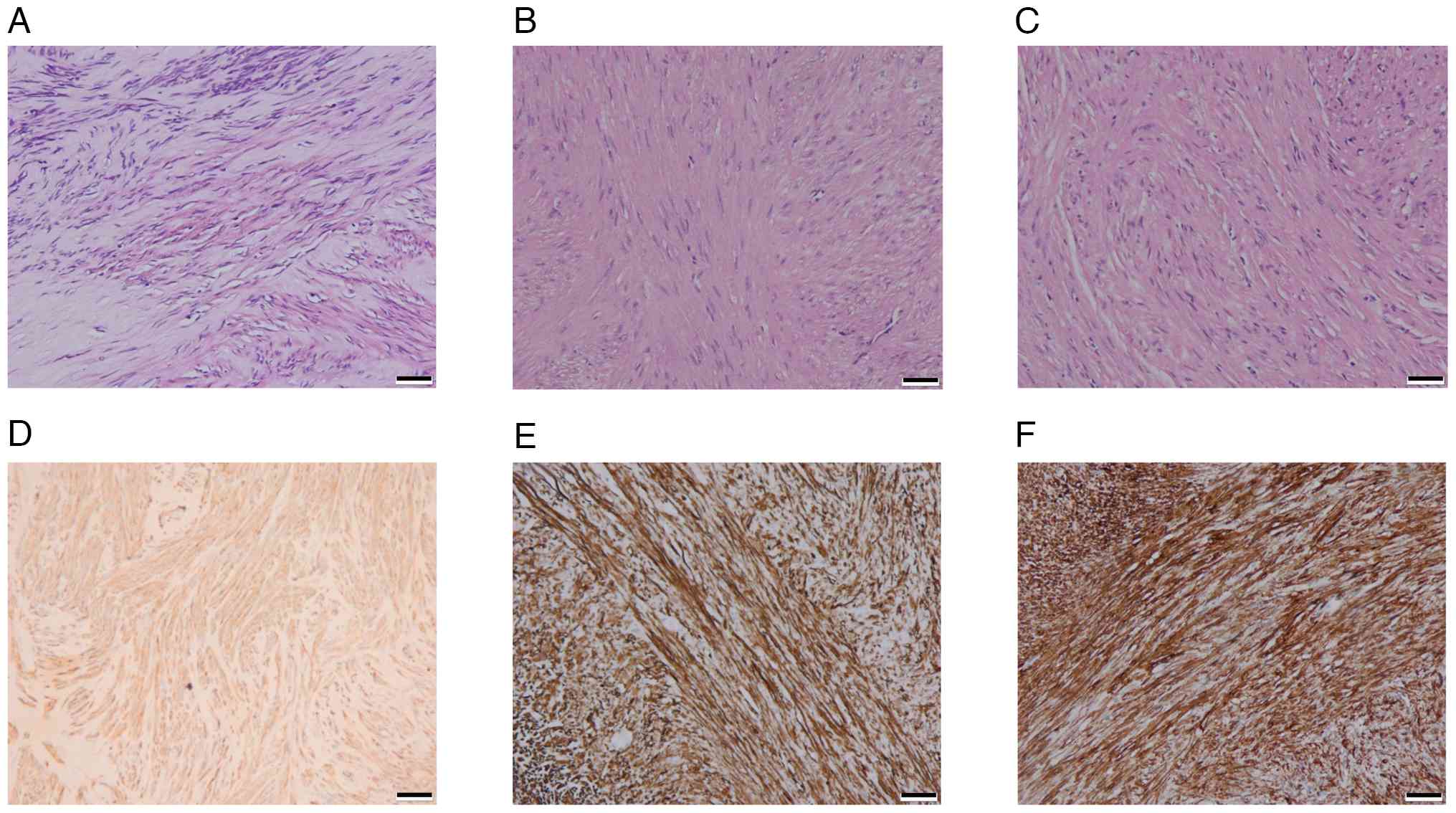

An endoscopic submucosal dissection was performed to excise the lesion completely, and the patient fully recovered without complications. During the procedure, three solid tumors matching the EUS separation finding were removed; the three tumors were distinct with intact structures, light gray surfaces and moderate hardness (Fig. 1D). Tumor tissue specimens were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin at room temperature for 24-48 h. Following fixation, the tissues were embedded in paraffin and sectioned into 3-µm slices. The sections were then stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) at room temperature, with hematoxylin applied for 5-10 min and eosin for 1-3 min. Histopathological analysis demonstrated that light-microscopically (H&E staining; x20 magnification), specimen No. 1 was composed of spindle-like cells with indistinct borders (Fig. 2A), while the No. 2 (Fig. 2B) and No. 3 (Fig. 2C) specimens had spindle-like cells in bundles with defined borders. The immunohistochemical (IHC) staining was performed on a fully automated IHC platform (Roche Diagnostics GmbH) according to the standardized protocol. Deparaffinization was carried out using the instrument s preconfigured settings. Heat-induced antigen retrieval was conducted with cell conditioner 1 reagent (Roche Diagnostics GmbH) in accordance with the manufacturer s protocol. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by incubating the slides with 3% hydrogen peroxide blocking solution (Roche Diagnostics GmbH) at room temperature for 10 min. Primary antibody incubation was performed at 37˚C for 32 min using ready-to-use formulations. The antibodies applied included Pan-CytoKeratin (PCK) (cat. no. CCM-0960), CD34 (cat. no. CCM-0550), Desmin (cat. no. CDM-0023) and Ki-67 (cat. no. CKM-0032) (all from Fuzhou Maixin Biotech. Co., Ltd.); along with CD117 (cat. no. kit-0029), DOG-1 (cat. no. kit-0035), SOX-10 (cat. no. RMA-0726), and S-100 (cat. no. kit-0007) (all from Celnovte Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). Subsequently, slides were incubated with a secondary antibody detection system (cat. no. 760-500; Roche Diagnostics GmbH) at 37˚C for 8 min. All automated procedures were strictly executed following the instrument s pre-programmed protocol. Each staining run included both negative and positive controls. All sections were subsequently examined and analyzed under a light microscope.

Specimen No. 1 was histologically diagnosed as a GIST. According to the modified NIH criteria (15), the tumor had a mitotic count of 1/5 mm2 and was classified as G1 (low risk). IHC analysis revealed a profile positive for CD117, DOG-1 and CD34, and negative for PCK, Desmin, SOX-10 and S-100. The Ki-67 proliferation index was low at 1% (Fig. 2D).

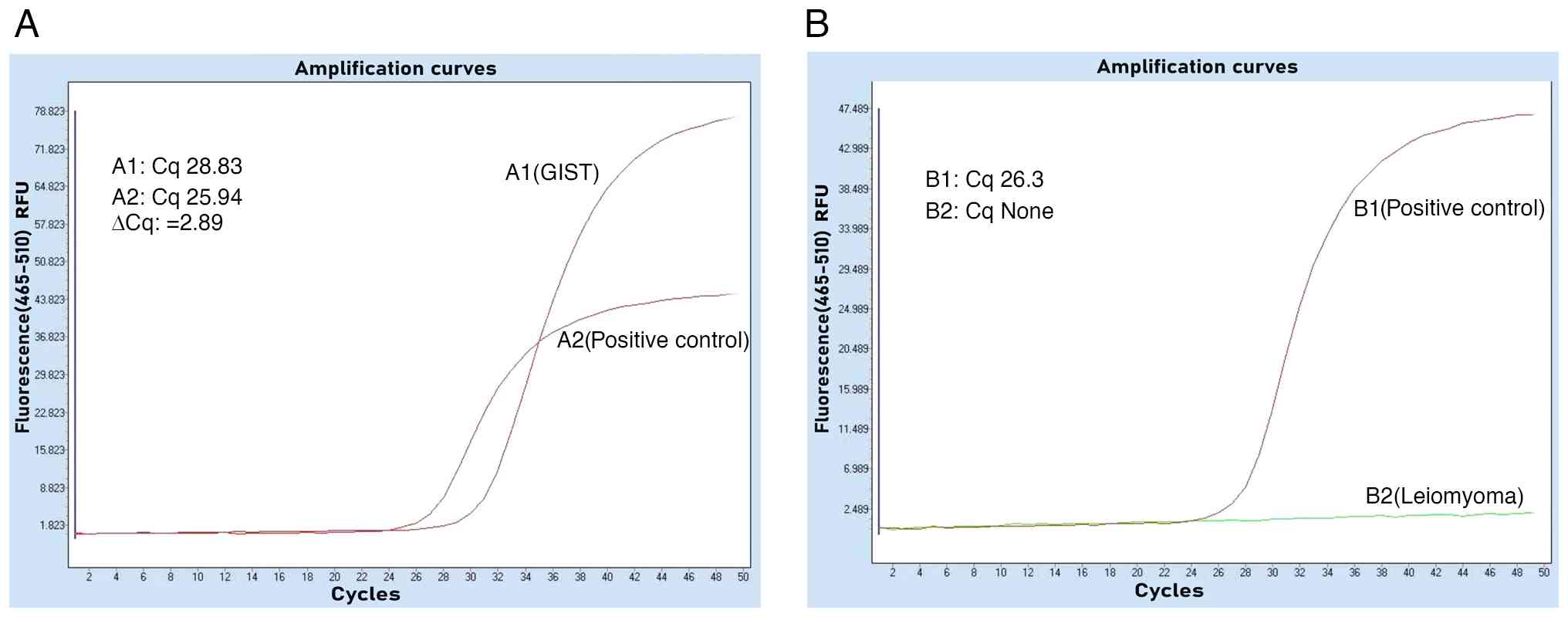

Specimens No. 2 and No. 3 were leiomyomas with immunohistochemistry of PCK(-), CD117(-), Dog-1(-), CD34(-), Desmin(+), SOX-10(-), S-100(-) and Ki-67(+,1%) (Fig. 2E and F). The tumors underwent genetic testing through quantitative PCR, by the independent third-party laboratory, De-an Medical Testing Co., Ltd, using the LightCycler 480 II real-time PCR system (Roche Diagnostics). DNA was extracted from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue specimens (obtained from the Sichuan Science City Hospital, Mianyang, China) by De-an Medical Testing Co., Ltd using the Nucleic Acid Extraction or Purification Reagent (Gene Tech Biotechnology), in strict accordance with the manufacturer s protocol. The procedure included deparaffinization, proteinase K digestion, decrosslinking, DNA capture on a filter membrane, two rapid wash steps and a final elution in the provided DNA elution buffer. For BRAFV600E mutation detection, quantitative PCR was performed using the Human BRAF Gene V600E Mutation Detection Kit (PCR-fluorescent probe method; Wuhan YZY Medical Science and Technology Co., Ltd) in strict adherence to the manufacturer s protocol. The qPCR assay was outsourced to De-an Medical Testing Co., Ltd. The thermal cycling conditions were as follows: Uracil-N-glycosylase treatment at 37˚C for 10 min; pre-denaturation at 95˚C for 5 min; followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95˚C for 15 sec and annealing/extension at 60˚C for 60 sec. The nucleotide sequences for the primers and probes were not provided by the manufacturer (cat. no. YZYMT-003; Wuhan YZY Medical Science and Technology Co., Ltd.). The results determined that a BRAFV600E mutation was present in the GIST, but not in the leiomyomas (Fig. 3A and B).

Based on established risk stratification guidelines, adjuvant targeted therapy was deemed unnecessary as an R0 resection had been achieved and the GIST was determined to be low risk (G1) (15-19). The management plan consisted of active surveillance with contrast-enhanced CT is typically performed every 6-12 months (15-19).

Discussion

According to the current World Health Organization tumor classification, GIST is classified as a malignant tumor (20,21). The GIST primarily stems from Cajal cells or their precursor cells in the muscular connective tissue of the gastrointestinal tract (9), while a minor fraction may originate from smooth muscle cells (22). Cajal cells could be traced back to mesenchymal cells during the embryonic period (22). Gastrointestinal leiomyomas occur predominantly in the esophagus (12,13) and originate from the smooth muscle cells (23), which are also derived from embryonic mesenchymal cells (24).

Derived from the mesodermal germ layer, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) serve as multipotent precursors that generate the diverse spectrum of mesenchymal cells. This differentiation cascade culminates in the formation of mature bone, cartilage and connective tissue (25). Notably, interstitial cells of Cajal (ICC) are a specialized product of this cascade, originating directly from mesenchymal cells but whose developmental origin can be traced to the primordial MSC pool (26). Research by Radenkovic et al (27) indicates that mesenchymal cells give rise to c-KIT-positive precursors common to both ICC and smooth muscle cells. The divergent differentiation of this precursor pool is then directed by stem cell factor; precursors adjacent to ganglia commit to the ICC lineage, whereas the remainder differentiate into smooth muscle cells (27). Therefore, GIST and gastric leiomyoma originate from the same cellular lineages, suggesting a potential relation. Further research has revealed that GIST can develop from smooth muscle cells of the digestive tract by the BRAFV600E mutation (28-30). In a previous study, Kondo et al (31) successfully generated GIST cells by inducing a BRAFV600E mutation in smooth muscle cells using Myh11CreERT2 and BRAFLSL-V600E/+ mouse models. These findings provided the rationale for our detection into BRAFV600E mutation in patient. Notably, the BRAFV600E gene mutation was identified in the GIST specimen from the patient in the present study, thereby providing compelling evidence for the close association between GIST and smooth muscle cells. It would have been of interest to conduct single-cell sequencing on the present samples to elucidate the precise connection between GIST and gastric leiomyoma; however, at the time, this was not possible. Nevertheless, the co-occurrence of GIST and gastric leiomyomas within the same lesion provides some new insights for scientific exploration.

It is well known that most GISTs are positive for the gene KIT (CD117) (95%), DOG1 (>95%), CD34 (60-80%), α-smooth muscle actin (20-40%) and S-100 protein (5%). GISTs that are negative for the KIT gene occur in 5% of patients, and these exhibit epithelial cell morphology and a mutation in the platelet-derived growth factor receptor α (PDGFRA) gene (19). Numerous studies define some GISTs as ‘wild-type’ due to a lack of common driver mutations (such as KIT or PDGFRA); among these, BRAFV600E mutations represent a frequently observed alternative (32,33). The incidence of BRAFV600E mutations has been reported with a low frequency between 3.5 and 13.4% in wild-type GISTs, which is notably lower than KIT/PDGFRA mutations (30,34), leading to oversight frequently. In the clinical diagnosis of GIST, essential immunohistochemical tests include CD117, DOG1, actin, desmin, S-100 and CD34 (16,19). Therefore, physicians predominantly assess the KIT (CD117) and PDGFRA mutations without BRAFV600E in the diagnosis of GIST in clinical practice. However, the BRAFV600E mutations can co-occur with KIT. Consequently, the prevalence of BRAFV600E mutations in patients with GIST could be markedly underestimated. In addition, the present findings indicate that the KIT and BRAFV600E gene can be concomitant in a patient with GIST, which is consistent with other research. For example, during the investigation of BRAFV600E mutations in patients with wild-type GIST, researchers incidentally identified a case with co-existing KIT and BRAFV600E mutations in the same individual (34). This speculation is further corroborated in the research conducted by Jašek et al (35), in the present study, screening of 35 unselected GISTs revealed a significant finding, eight KIT/PDGFRA-positive tumors harbored concurrent BRAFV600E mutations. The co-occurrence involved five cases with KIT and three with PDGFRA mutations.

Most GISTs and leiomyomas are typically asymptomatic, and are frequently detected during gastrointestinal endoscopy (14,36). Early GISTs can be effectively treated through endoscopic or surgical resection, resulting in a favorable prognosis. The current guidelines in numerous countries advocate endoscopic resection for GISTs <2 cm, whereas for those >2 cm, the risk of metastasis escalates (17,19). The pathological results of GISTs determine whether the patient receives tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) (10,16,17,19); the accurate determination of genetic mutations plays a notable role in the diagnosis and treatment, as based on existing research, the efficacy of TKIs varies markedly among distinct gene mutation types (16,19). The current international guidelines advocate imatinib as the first-line treatment for patients with locally advanced unresectable and metastatic GIST, as well as those who have undergone complete resection with metastasis (15,19). The majority of GISTs harboring KIT mutations exhibit sensitivity to imatinib, whereas >50% of GISTs with PDGFRA mutations demonstrate resistance to imatinib, particularly those carrying the D842V mutation in exon 18 of PDGFRA (15,19). For patients with local GIST at high risk of recurrence, the standard regimen entails continuous imatinib for 3 years. The management of patients with metastases often requires a protracted course of drug therapy, unless there is an occurrence of intolerance or a specific request for discontinuation (18). However, the risk of TKI resistance is high due to the presence of primary multiple gene mutation mechanisms of GIST and subsequent secondary gene mutations during late-stage medication (37,38). Currently, there are no consensus guidelines for the treatment of GISTs harboring co-existing KIT and BRAFV600E mutations. In our view, for localized GIST <2 cm, endoscopic resection is the initial treatment of choice. For metastatic GIST, imatinib remains the first-line therapy. However, optimal treatment strategies for patients who develop resistance to imatinib require further investigation. The results of the current study present an innovative research direction in GIST treatment and management.

In conclusion, to the best of our knowledge, we propose for the first time that there may be homology between GISTs and gastric leiomyomas, and that the BRAFV600E mutation is the critical trigger; the incidence of BRAFV600E may have been underestimated by clinicians and researchers. Clinicians should recognize that GIST and gastric leiomyoma can coexist in the same SEL to avoid misdiagnosis and mistreatment. In the face of the escalating drug resistance rate of GIST, researchers may derive some novel insights from the present findings for GIST treatment and management.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the external company De-an Medical Testing Co., Ltd for their collaboration.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be requested from the corresponding author.

Authors contributions

YZ and XQS confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. The present study was conceptualized by YZ, who also drafted the manuscript. XQS oversaw patient management and communication. WFX and MLH performed the endoscopic resection of the lesion. SZ, XP and HL were responsible for patient care management and data summarization. HYL and XLL were responsible for the fixation and processing of surgical specimens, immunohistochemical examination, and the related data collection and verification. Pathology and molecular biology testing were carried out by QS, FYZ and MYW. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Sichuan Science City Hospital (Mianyang, China; approval no. 2025019).

Patient consent for publication

Written informed consent for publication of the clinical details and images was obtained from the patient.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

|

1

|

Klangjorhor J, Pongnikorn D, Sittiju P, Phanphaisarn A, Chaiyawat P, Teeyakasem P, Kongdang P, Moonmuang S, Waisri N, Daoprasert K, et al: Descriptive epidemiology of soft tissue sarcomas and gastrointestinal stromal tumors in Thailand. Sci Rep. 12(12824)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Verschoor AJ, Bovée JVMG and Overbeek LIH: PALGA group. Hogendoorn PCW and Gelderblom H: The incidence, mutational status, risk classification and referral pattern of gastro-intestinal stromal tumours in the Netherlands: A nationwide pathology registry (PALGA) study. Virchows Arch. 472:221–229. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Zhu H, Yang G, Ma Y, Huo Q, Wan D and Yang Q: Update of epidemiology, survival and initial treatment in patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumour in the USA: A retrospective study based on SEER database. BMJ Open. 13(e072945)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Mantese G: Gastrointestinal stromal tumor: Epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Curr opin gastroen. 35:555–559. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Xu L, Ma Y, Wang S, Feng J, Liu L, Wang J, Liu G, Xiu D, Fu W, Zhan S, et al: Incidence of gastrointestinal stromal tumor in Chinese urban population: A national population-based study. Cancer Med. 10:737–744. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Khan J, Ullah A, Waheed A, Karki NR, Adhikari N, Vemavarapu L, Belakhlef S, Bendjemil SM, Mehdizadeh Seraj S, Sidhwa F, et al: Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST): A population-based study using the SEER database, including management and recent advances in targeted therapy. Cancers (Basel). 14(3689)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Mechahougui H, Michael M and Friedlaender A: Precision oncology in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Curr Oncol. 30:4648–4662. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Abdalla TSA, Pieper L, Kist M, Thomaschewski M, Klinkhammer-Schalke M, Zeissig SR, Tol KK, Wellner UF, Keck T and Hummel R: Gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the upper GI tract: Population-based analysis of epidemiology, treatment and outcome based on data from the German clinical cancer registry group. J Cancer Res Clin. 149:7461–7469. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Alvarez CS, Piazuelo MB, Fleitas-Kanonnikoff T, Ruhl J, Pérez-Fidalgo JA and Camargo MC: Incidence and survival outcomes of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. JAMA Netw Open. 7(e2428828)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Deprez PH, Moons LMG, O toole D, Gincul R, Seicean A, Pimentel-Nunes P, Fernández-Esparrach G, Polkowski M, Vieth M, Borbath I, et al: Endoscopic management of subepithelial lesions including neuroendocrine neoplasms: European society of gastrointestinal endoscopy (ESGE) guideline. Endoscopy. 54:412–429. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Kim GH: Systematic endoscopic approach for diagnosing gastric subepithelial tumors. Gut Liver. 16:19–27. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Zackria R and Choi EH: Esophageal schwannoma: A rare benign esophageal tumor. Cureus. 13(e15667)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

A-Lai GH, Hu JR, Yao P and Lin YD: Surgical treatment for esophageal leiomyoma: 13 years of experience in a high-volume tertiary hospital. Front Oncol. 12(876277)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Park K, Ahn JY, Na HK, Jung KW, Lee JH, Kim DH, Choi KD, Song HJ, Lee GH and Jung HY: Natural history of gastric leiomyoma. Surg Endosc. 38:2726–2733. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Serrano C, Álvarez R, Carrasco JA, Marquina G, Martínez-García J, Martínez-Marín V, Sala MÁ, Sebio A, Sevilla I and Martín-Broto J: SEOM-GEIS clinical guideline for gastrointestinal stromal tumors (2022). Clin Transl Oncol. 25:2707–2717. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Serrano C, Martín-Broto J, Asencio-Pascual JM, López-Guerrero JA, Rubió-Casadevall J, Bagué S, García-Del-Muro X, Fernández-Hernández JÁ, Herrero L, López-Pousa A, et al: 2023 GEIS Guidelines for gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 15(17588359231192388)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Jacobson BC, Bhatt A, Greer KB, Lee LS, Park WG, Sauer BG and Shami VM: ACG clinical guideline: Diagnosis and management of gastrointestinal subepithelial lesions. Am J Gastroenterol. 118:46–58. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Casali PG, Blay JY, Abecassis N, Bajpai J, Bauer S, Biagini R, Bielack S, Bonvalot S, Boukovinas I, Bovee JVMG, et al: Gastrointestinal stromal tumours: ESMO-EURACAN-GENTURIS clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann oncol. 33:20–33. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Hirota S, Tateishi U, Nakamoto Y, Yamamoto H, Sakurai S, Kikuchi H, Kanda T, Kurokawa Y, Cho H, Nishida T, et al: English version of Japanese clinical practice guidelines 2022 for gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) issued by the Japan society of clinical oncology. Int J Clin Oncol. 29:647–680. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

International Classification of Diseases for Oncology: ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics: XH9HQ1. World Health Organization, Geneva, 2025. https://icd.who.int/browse/2024-01/mms/en#2069696861.

|

|

21

|

Tsurumaru D, Nishimuta Y, Kai S, Oki E, Minoda Y and Ishigami K: Clinical significance of dual-energy dual-layer CT parameters in differentiating small-sized gastrointestinal stromal tumors from leiomyomas. Jpn J Radiol. 41:1389–1396. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Sweet T, Abraham CM and Rich A: Origin and development of interstitial cells of Cajal. Int J Dev Biol. 68:93–102. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

White A, Sikora J, Thannoun A and Soliman B: Gastric leiomyoma near the gastroesophageal junction causing massive gastrointestinal bleeding. Cureus. 15(e48374)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Mclin VA, Henning SJ and Jamrich M: The role of the visceral mesoderm in the development of the gastrointestinal tract. Gastroenterology. 136:2074–2091. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Gou Y, Huang Y, Luo W, Li Y, Zhao P, Zhong J, Dong X, Guo M, Li A, Hao A, et al: Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are a superior cell source for bone tissue engineering. Bioact Mater. 34:51–63. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Mihai MC, Popa MA, Șuică VI, Antohe F, Jackson EK, Leeners B, Simionescu M and Dubey RK: Proteomic analysis of estrogen-mediated enhancement of mesenchymal stem cell-induced angiogenesis in vivo. Cells. 10(2181)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Radenkovic G, Radenkovic D and Velickov A: Development of interstitial cells of Cajal in the human digestive tract as the result of reciprocal induction of mesenchymal and neural crest cells. J Cell Mol Med. 22:778–785. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Unk M, Jezeršek Novaković B and Novaković S: Molecular mechanisms of gastrointestinal stromal tumors and their impact on systemic therapy decision. Cancers (Basel). 15(1498)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Zhang W, Wang S, Zhang H, Meng Y, Jiao S, An L and Zhou Z: Modeling human gastric cancers in immunocompetent mice. Cancer Biol Med. 21:553–570. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Biagioni A, Peri S, Versienti G, Fiorillo C, Becatti M, Magnelli L and Papucci L: Gastric cancer vascularization and the contribution of reactive oxygen species. Biomolecules. 13(886)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Kondo J, Huh WJ, Franklin JL, Heinrich MC, Rubin BP and Coffey RJ: A smooth muscle-derived, Braf-driven mouse model of gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST): Evidence for an alternative GIST cell-of-origin. J Pathol. 252:441–450. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Denu RA, Joseph CP, Urquiola ES, Byrd PS, Yang RK, Ratan R, Zarzour MA, Conley AP, Araujo DM, Ravi V, et al: Utility of clinical next generation sequencing tests in KIT/PDGFRA/SDH wild-type gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Cancers (Basel). 16(1707)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Nishida T, Naito Y, Takahashi T, Saito T, Hisamori S, Manaka D, Ogawa K, Hirota S and Ichikawa H: Molecular and clinicopathological features of KIT/PDGFRA wild-type gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Cancer Sci. 115:894–904. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Jasek K, Buzalkova V, Minarik G, Stanclova A, Szepe P, Plank L and Lasabova Z: Detection of mutations in the BRAF gene in patients with KIT and PDGFRA wild-type gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Virchows Arch. 470:29–36. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Jašek K, Váňová B, Grendár M, Štanclová A, Szépe P, Hornáková A, Holubeková V, Plank L and Lasabová Z: BRAF mutations in KIT/PDGFRA positive gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GISTs): Is their frequency underestimated? Pathol Res Pract. 216(153171)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Li AX, Liu E, Xie X, Peng X, Nie XB, Li JJ, Gao Y, Liu L, Bai JY, Wang TC and Fan CQ: Efficacy and safety of piecemeal submucosal tunneling endoscopic resection for giant esophageal leiomyoma. Dig Liver Dis. 56:1358–1365. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Liu X, Yu J, Li Y, Shi H, Jiao X, Liu X, Guo D, Li Z, Tian Y, Dai F, et al: Deciphering the tumor immune microenvironment of imatinib-resistance in advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumors at single-cell resolution. Cell Death Dis. 15(190)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Kalfusova A, Linke Z, Kalinova M, Krskova L, Hilska I, Szabova J, Vicha A and Kodet R: Gastrointestinal stromal tumors- Summary of mutational status of the primary/secondary KIT/PDGFRA mutations, BRAF mutations and SDH defects. Pathol Res Pract. 215(152708)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|