Introduction

Paragangliomas (PGLs) are rare neuroendocrine tumors

originating from paraganglionic cells adjacent to blood vessels and

nerves. The tumors are classifiable as parasympathetic or

sympathetic in type. Parasympathetic PGLs primarily involve the

head and neck region, whereas sympathetic variants typically arise

in the retroperitoneum, thoracic cavity and pelvis (1,2).

Such tumors are seldom encountered, having an estimated annual

incidence of 2-8 cases per million individuals (1,3).

Overall, 6-19% are known to exhibit malignant behavior, developing

distant metastases that often affect the regional lymph nodes,

lungs and bones (1,4). According to World Health Organization

guidelines, all PGLs should be viewed as potentially malignant and

thus require vigilant, long-term follow-up, even after surgery

(3,5).

Head and neck paragangliomas (HNPGLs) account for

65-70% of all PGLs (1). Although

generally slow-growing, HNPGLs must be regarded as potentially

malignant subsets of PGL, warranting long-term follow-up after

treatment (4). Common sites of

origin include the carotid body, temporal bone, jugular foramen,

mastoid foramen and areas surrounding the vagus nerve (2,6).

The estimated incidence of HNPGL ranges from 0.3-1

case per 100,000 individuals every year in the general population,

underscoring its rarity (1). Our

limited understanding of their biological attributes and a lack of

standardized treatment strategies complicates interventional

decisions, whether surgery, radiotherapy or observation, which

remain challenging in each instance (1,6).

Importantly, those tumors that recur near critical structures (such

as the brainstem) are in need of safe and effective therapeutic

strategies.

The present study details the course of a patient

undergoing two surgical procedures for PGL. The tumor arose and

then recurred at the jugular foramen, invading the medulla

oblongata. Use of hypofractionated intensity-modulated proton

therapy (IMPT) ultimately allowed successful tumor control. A

discussion of pertinent resources in the literature is also

provided.

Case report

Patient history: The patient was a

52-year-old woman who first experienced tinnitus in the left ear in

November 2013 and presented to Yanshan Phoenix Hospital (Beijing,

China). No clear cause was determined, but the patient was

diagnosed with sensorineural hearing loss at the same hospital

several months later. The patient received oral neurotrophic drugs

and hyperbaric oxygen therapy. Subsequently, vasodilators,

Traditional Chinese Medicine (herbal medicine), and acupuncture

were administered at the Departments of Internal Medicine and

Otolaryngology of Yanshan Phoenix Hospital, but there was no major

improvement. The left-sided hearing loss continued to progress.

In August 2014, the patient also developed

hoarseness. Left vocal cord paralysis was observed using a

laryngeal fiberscope, so standard oral neurotrophic therapy (drug

name and dose unknown) was initiated at Fangshan Chinese Medicine

Hospital (Beijing, China), again without improvement. Another month

after this, the patient presented with left-sided tongue deviation

and dysphagia during liquid intake. According to the patient's

medical history records from Zhuozhou Chinese Medicine Hospital

(Zhuozhou, China), a space-occupying lesion was visible on magnetic

resonance imaging (MRI). This lesion involved the left

cerebellopontine angle, which raised suspicion of a primary tumor

at the jugular foramen. The patient underwent a left paraganglioma

resection via the retroauricular transmastoid and labyrinthine

approach, combined with abdominal fat filling for cavity

obliteration at the Chinese People's Liberation Army General

Hospital (Beijing, China).

The pathology report issued by the Chinese People's

Liberation Army General Hospital documented that postoperative

tissue analysis confirmed the diagnosis of paraganglioma.

Immunohistochemical staining was performed, demonstrating focal

positivity for chromogranin A (CgA), as well as synaptophysin

(Syn), CD56, S-100 protein and vimentin positivity. The Ki-67 index

was low (3%) (data not shown).

Approximately 6 and one-half years after the initial

resection, diplopia became an issue. Preoperative MRI at that time

confirmed a recurrent lesion (data not shown). A second tumor

resection took place 3 months later, at Beijing Tiantan Hospital

(Beijing, China). Following analysis using standard procedures

(fixation in 10% neutral buffered formalin, paraffin embedding and

sectioning to 4 µm thickness, followed by hematoxylin and eosin

staining), histological findings confirmed recurrent PGL. As shown

in Fig. S1A, the tumor cells

exhibited a nested arrangement (Zellballen pattern).

Immunohistochemical staining performed using standard procedures

(fixation in 10% neutral buffered formalin, paraffin embedding and

sectioning to 4 µm thickness, followed by staining using DAB as the

chromogen) showed strong positivity for CD56 (Fig. S1B) and CgA (Fig. S1C). The Ki-67 proliferation index

was low (3-7%) (Fig. S1D). S-100

protein staining was positive in the sustentacular cells

surrounding the tumor nests (Fig.

S1E). Furthermore, the pathology report recorded positive

results for other markers, including Syn, somatostatin receptor

type 2 and CD34 (in vascular endothelium) (data not shown). There

was partial positivity for transcription factor SOX10, and staining

for STAT6, cytokeratin, thyroid transcription factor-1 and

progesterone receptor was negative. Postoperatively, left facial

nerve paralysis was apparent.

At 18 months after the second surgery, tumor

progression was evident on MRI performed at Beijing Tiantan

Hospital, and had extended into the medulla oblongata.

Current presentation

The patient underwent concurrent IMPT at Hebei

Yizhou Cancer Hospital (Zhuozhou, China) in May 2023.

Planning and delivery of

hypofractionated proton beam therapy (PBT)

PBT was performed as a standalone procedure, using

intensity-modulated proton therapy (IMPT) with pencil-beam scanning

(PBS) and limiting treatment to local irradiation. The gross tumor

volume (GTV) was configured by fusing contrast-enhanced MRI and

planning computed tomography (CT) views, adding a 5-mm margin to

GTV to ascertain clinical target volume (CTV). The enhancing lesion

on MRI signified the GTV. For treatment planning, the patient's

head was immobilized in a custom-made thermoplastic mask, and daily

cone-beam CT (CBCT) imaging input offered guidance. Planning CT was

performed in the treatment position at a 1-mm slice thickness, with

CTV representing a 3-mm expansion of GTV. A further 3- to 5-mm

margin was added to the CTV to arrive at planning target volume

(PTV). IMPT served for dose delivery, adjusting prescribed doses

based on tumor location. The treatment plan was designed to ensure

that ≥95% of the PTV received prescribed dosing at the isocenter. A

summary of the doses prescribed and constraints for organs at risk

(OARs) is provided as Fig. 1. The

equivalent dose in 2 Gy fractions (EQD2) was calculated to evaluate

dosing, setting α/β ratios of 2 for the brainstem, optic nerves and

optic chiasm, and 10 for the tumor itself. The presumed relative

biological effectiveness of protons was 1.1, and the prescribed

dose for the GTV was 40 Gy in 15 fractions (EQD2, 42.09 Gy,

assuming α/β=10).

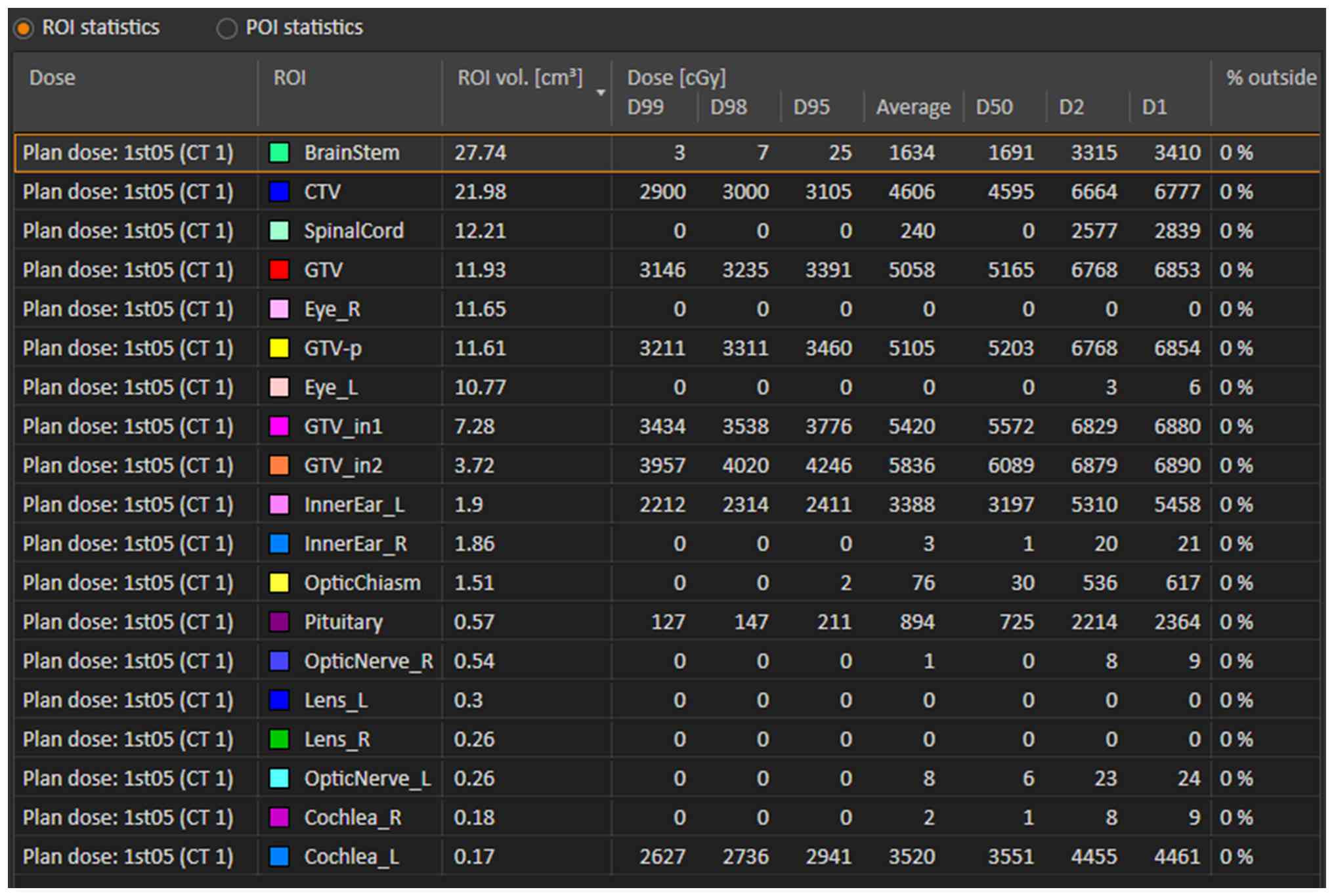

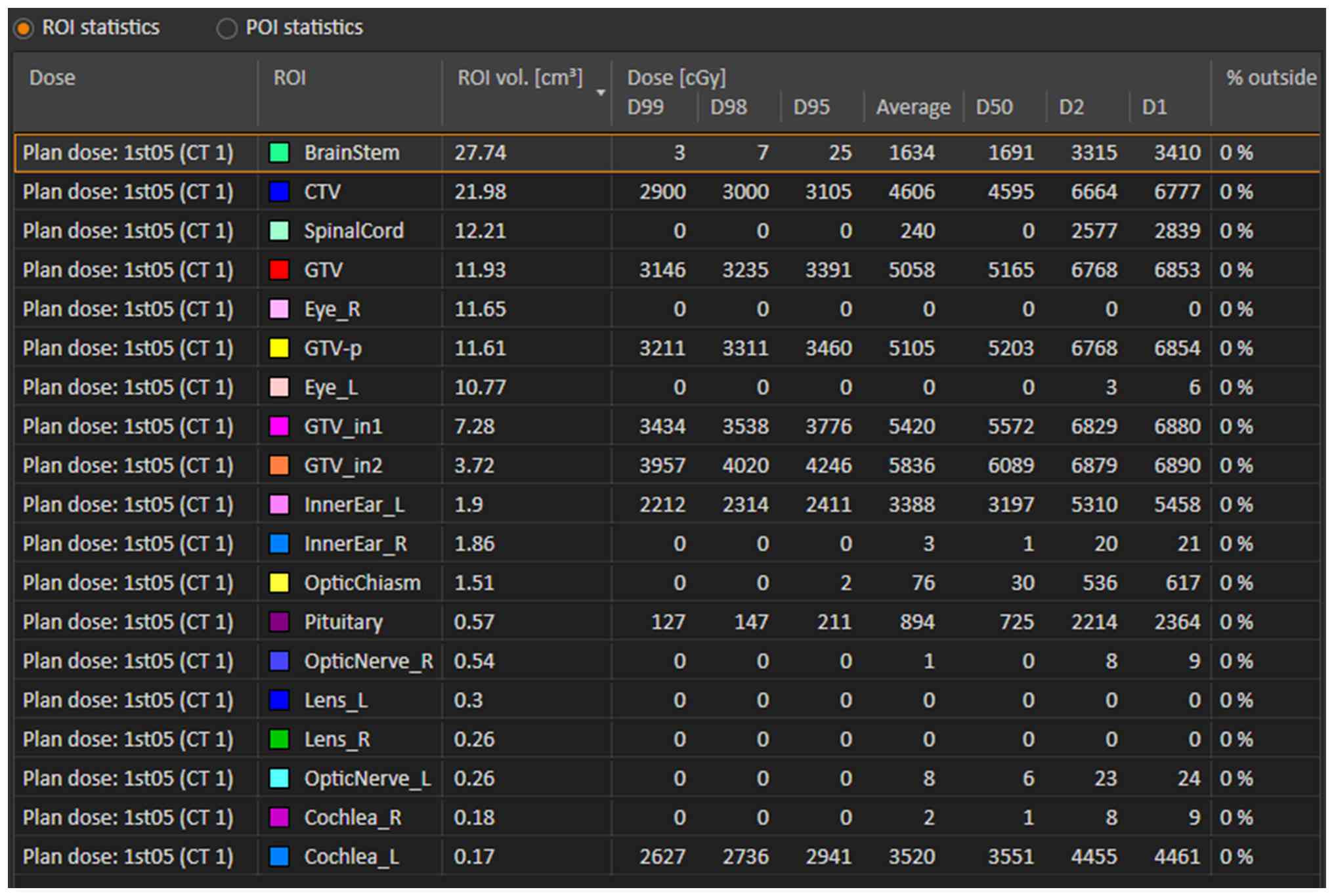

| Figure 1Summary of prescribed doses and

constraints for organs at risk. CTV, clinical target volume; GTV,

gross target volume; R, right; L, left; GTV_in1, GTV reduced by

2-mm margin; GTV_in2, GTV reduced by 3-mm margin; ROI, region of

interest; GTV-p, gross tumor volume-primary; CT, computed

tomography (planning image); D99, dose received by 99% of the

target volume. |

Two interior subvolumes of GTV were specified as GTV

reduced by 2-mm margin and GTV reduced by 3-mm margin. Prescribed

doses were 50 Gy/15 fractions (EQD2, 5.49 Gy) and 60 Gy/15

fractions (EQD2, 70.00 Gy), respectively.

The CTV determined as the contrast-enhancing lesion

on MRI plus a 3-mm margin, received 30 Gy in 15 fractions (EQD2,

30.00 Gy).

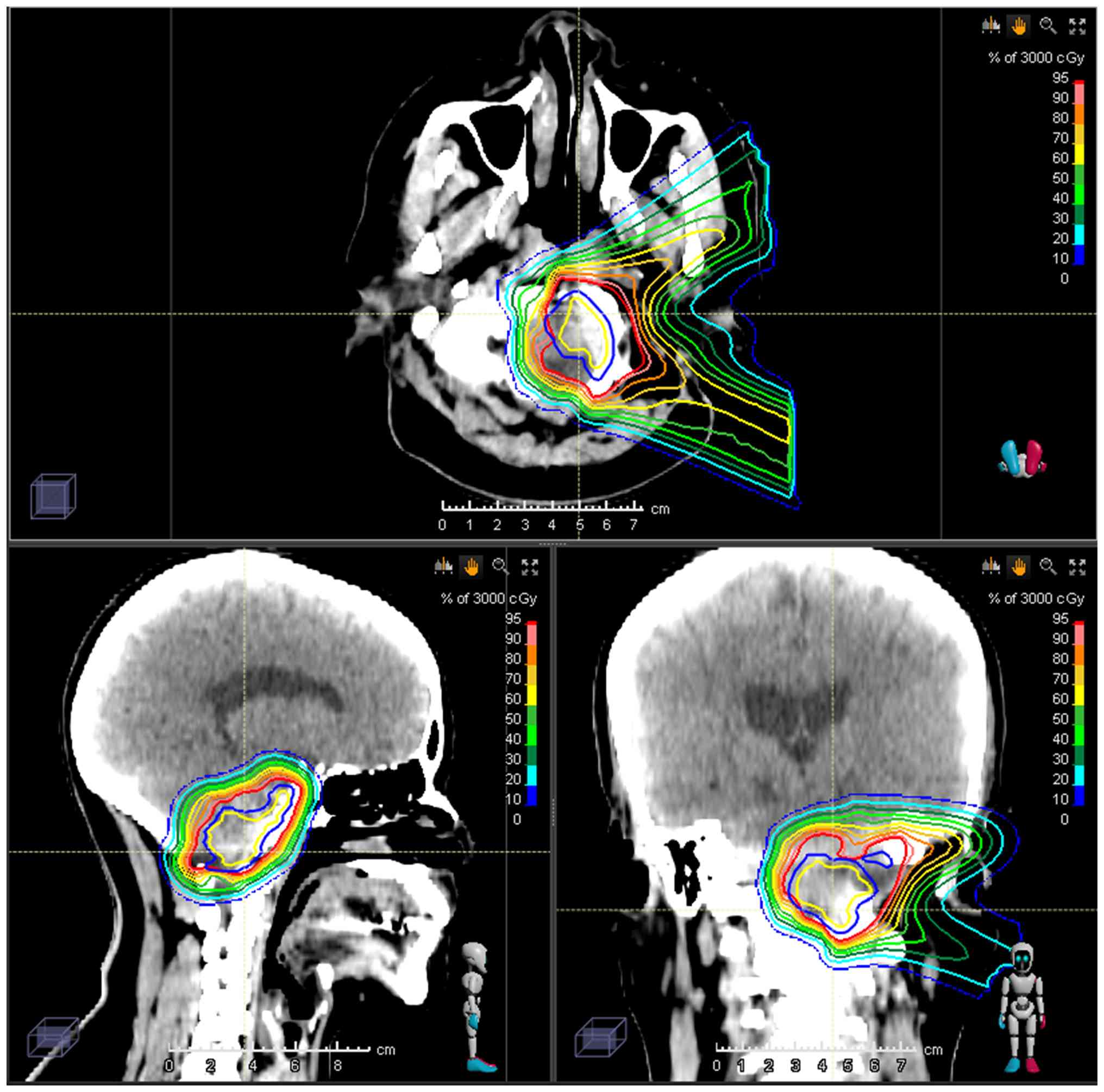

As OARs, the cochlea received 44.61 Gy in 15

fractions (EQD2, 55.48 Gy, assuming α/β=2) and the brainstem

received 34.1 Gy in 15 fractions (EQD2, 36.42 Gy, assuming α/β=2)

(Fig. 2).

Pretreatment physical examination. At the

start of PBT, the patient presented with left facial nerve

paralysis and oral commissure deviation to the right. Both pupils

were equal in size (~3 mm) and reactive to light. Right-eye

esotropia and left-eye diplopia were both noted, without visual

field defects. Complete hearing loss was also documented on the

left, whereas the right ear retained normal function. The patient

reported intermittent dysphagia, with choking during fluid intake

and difficulty consuming solid foods.

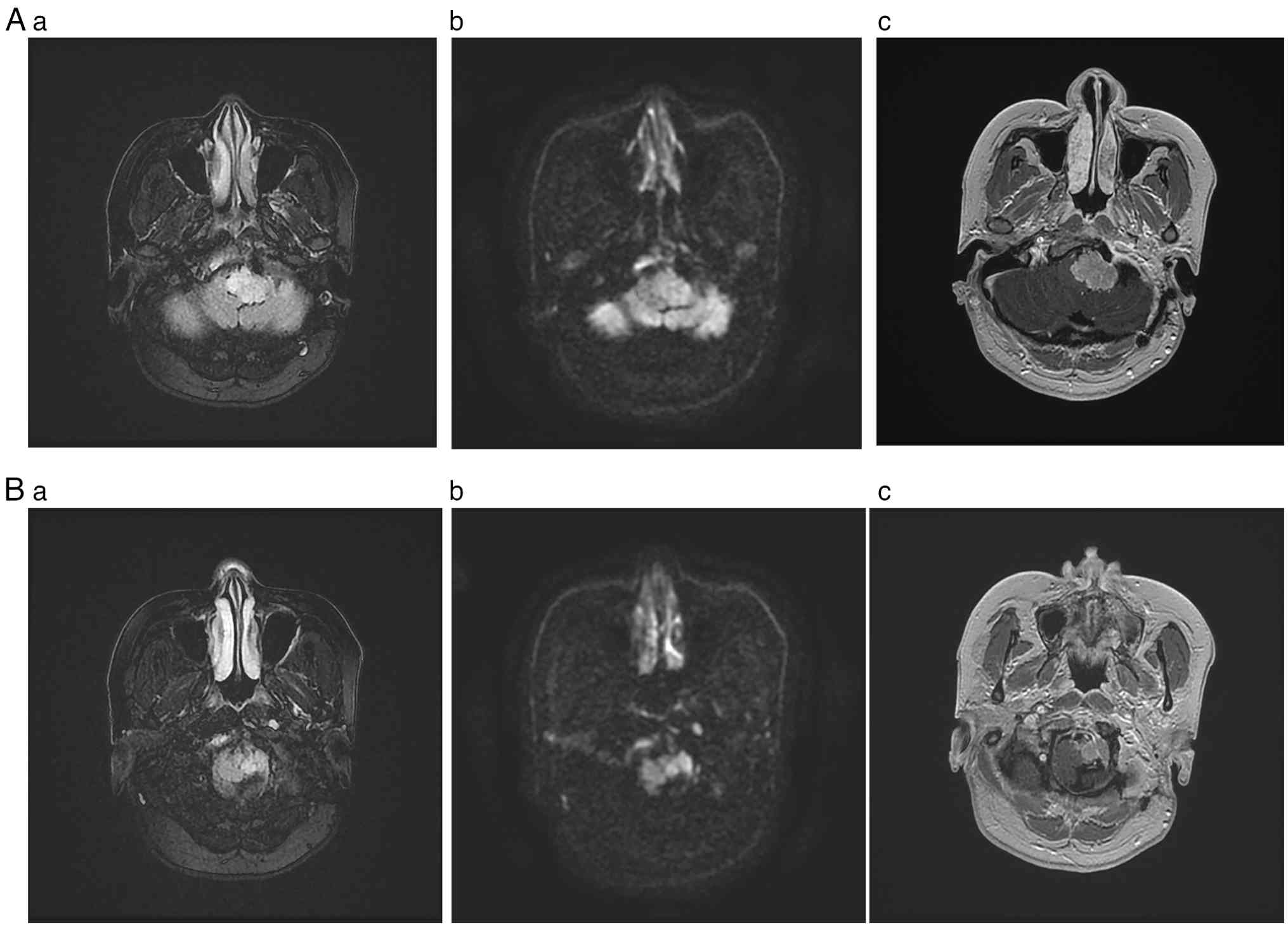

Imaging findings at baseline. Pretreatment

MRI revealed a mass lesion of the left anterior medulla (jugular

bulb region), showing somewhat increased signal intensity on both

T1- and T2-weighted images. This lesion was heterogeneous but

proved strongly enhanced by contrast, displaying an irregular shape

and measuring ~2.5x2.1x1.7 cm. The medulla was compressed, deformed

and displaced to the right (Fig.

3).

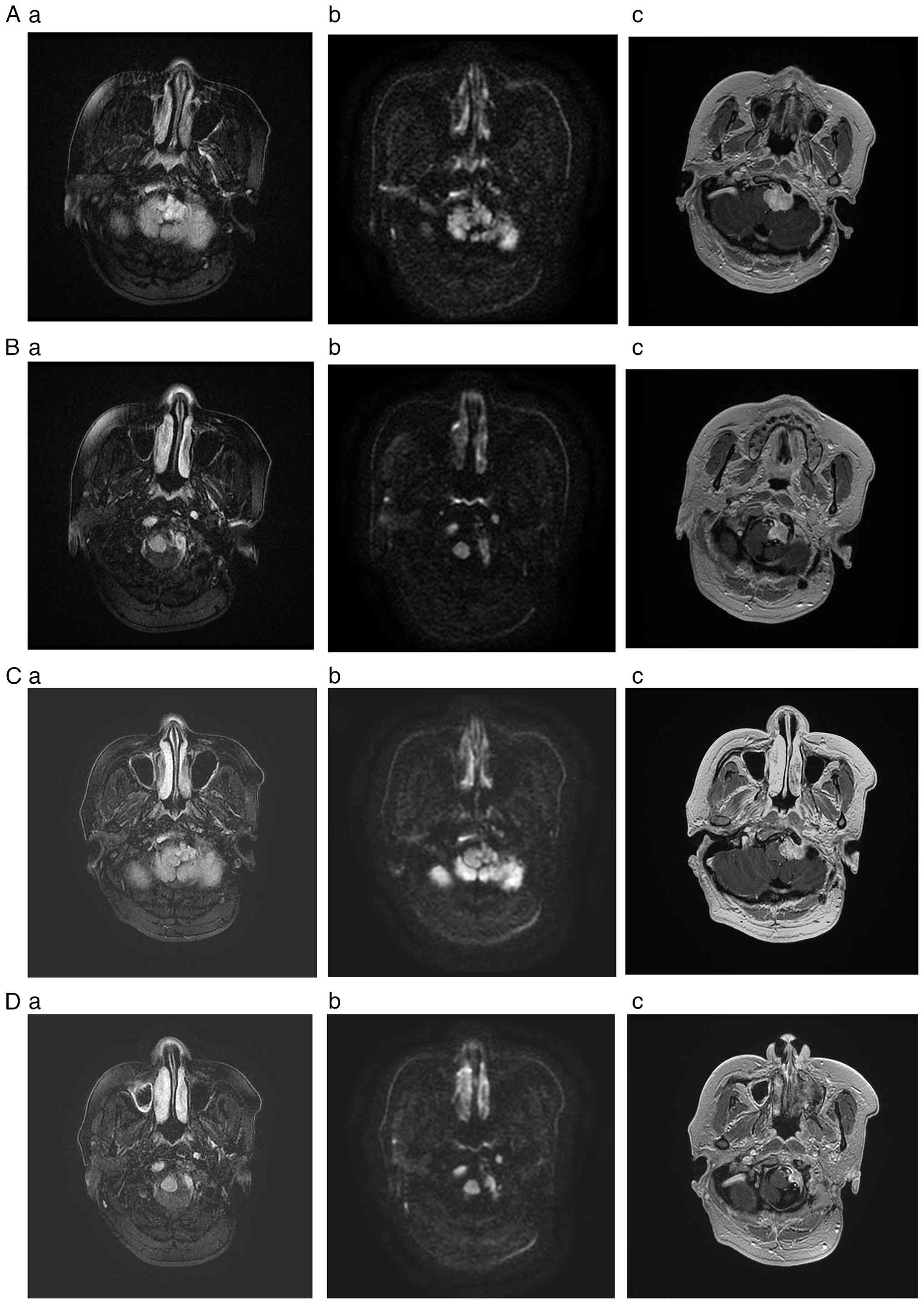

Follow-up imaging evaluation at 11 months

post-surgery. MRI showed no evidence of significant tumor

growth or recurrence 11 months after treatment, indicating stable

post-treatment changes. Follow-up imaging conducted 18 months after

treatment also demonstrated stable conditions, supporting the

long-term efficacy of PBT in suppressing tumor progression and

preventing recurrence (Fig.

4).

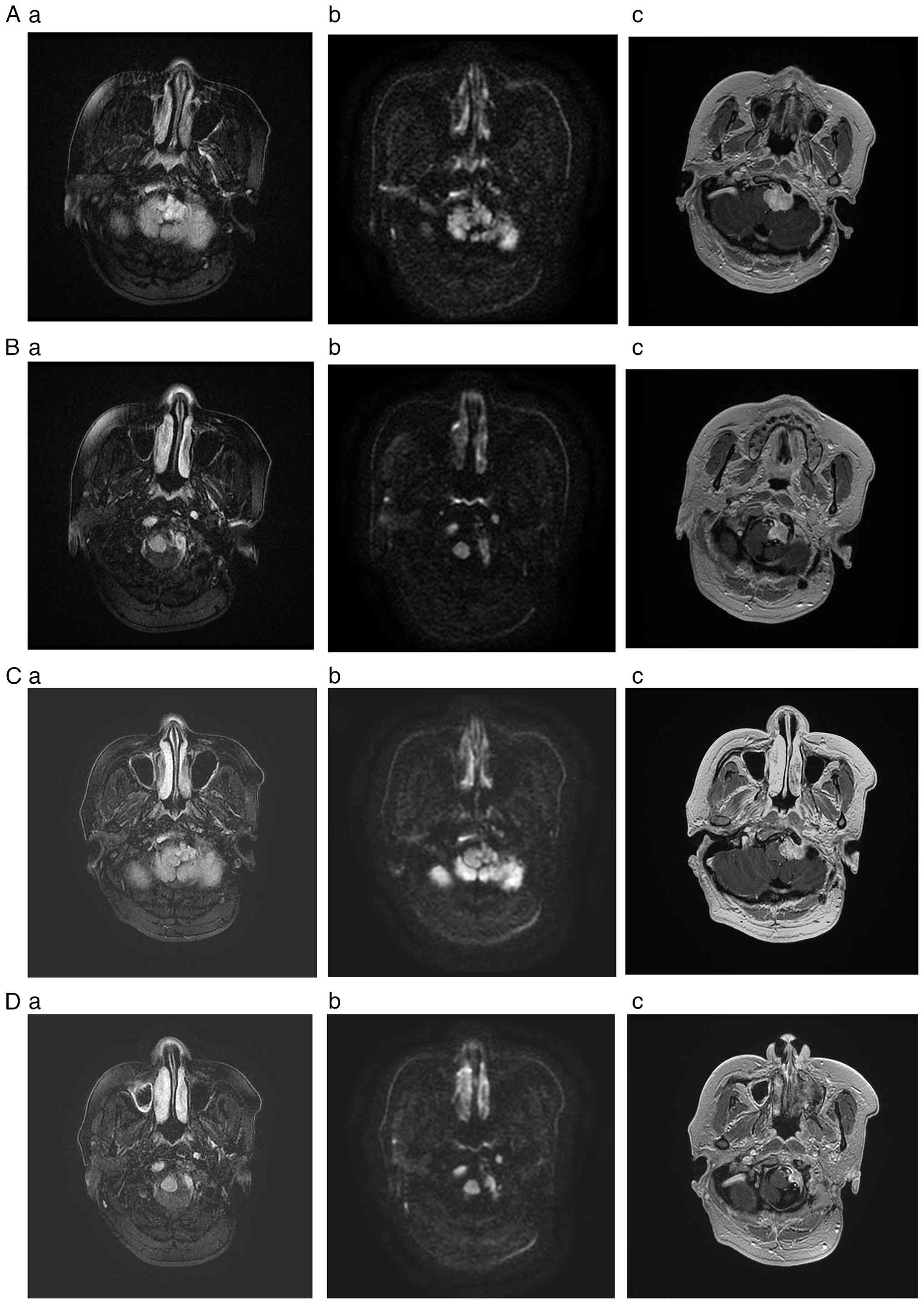

| Figure 4Magnetic resonance imaging study

during follow-up. (A and B) Images obtained at 11 months

post-treatment (April 2024). Images (A) and (B) represent different

axial section levels. (C and D) Images obtained at 18 months

post-treatment (December 2024). Images (C) and (D) represent

different axial section levels. (A-a, B-a, C-a and D-a) T2-weighted

fluid-attenuated inversion recovery sequences marked by a nodular,

somewhat hyperintense signal involving the left jugular bulb region

and the left lateral medulla oblongata. (A-b, B-b, C-b and D-b) DWI

demonstrating isointense or now vaguely hypointense signaling in

these areas. (A-c, B-c, C-c and D-c) T1-weighted imaging, again

disclosing moderate contrast enhancement in a heterogeneous pattern

at the aforementioned sites. Relative to pretreatment status in

Fig. 3 (May 2023), follow-up views

(A and B) at 11 months and (C and D) 18 months confirm significant

tumor volume reduction and diminished DWI signal intensity,

suggesting pronounced decline in tumor activity. DWI,

diffusion-weighted imaging. |

Clinical course 1 year after PBT. The

patient's neurological function had markedly improved at the 1-year

follow-up, showing substantial recovery of the facial nerve palsy.

The strabismus and diplopia had largely resolved, and there were

major strides in the abatement of choking frequency and swallowing

difficulty. The patient's hearing had also partially returned on

the left, although vertigo persisted.

Overall, the patient had experienced acute adverse

effects, such as vertigo, headache, nausea, vomiting and reflux,

during the first year after treatment. These were effectively

addressed through symptomatic management. By the 1-year mark, most

symptoms had considerably lessened, indicating good overall

tolerability of PBT. Late adverse effects further improved over

time, gradually diminishing between 6- and 18-months

post-treatment. This aided the recovery process and enhanced the

patient's quality of life. The patient is currently followed up

with clinical assessments and MRI scans every 3 months. Given the

high local control rates typically associated with high-dose PBT

for paragangliomas, the likelihood of local recurrence is

considered low, and the long-term prognosis for tumor control is

expected to be favorable. The patient has remained recurrence-free

for 24 months since PBT, showing marked symptom improvement

Discussion

As seen in the present patient, PGL recurrence in

close proximity to vital neurovascular structures has serious

clinical ramifications. Both anatomical considerations and

difficulties entailed in separating tumor from nerves and vessels

create inordinate opportunities for surgically related damage and

complications. The majority of PGLs arise within the head and neck

regions, and commonly originate from paraganglionic tissue near the

carotid body, vagus nerve, middle ear and jugular foramen (2,6).

Those abutting the jugular foramen are spawned by adventitial

paraganglionic cells of the jugular bulb, set within the temporal

bone; they are slow-growing and yet intensely vascular. Although

typically benign, such tumors may enlarge, infiltrate or destroy

surrounding bony structures and inflict complications due to mass

effects (1,2,7).

Traditionally, their clinical management (especially those at the

jugular foramen) has centered on complete surgical resection

(8,9). However, advances in neuroimaging and

radiotherapy technologies, along with mounting demand for less

invasive strategies in this rather benign setting, have prompted a

shift toward more conservative efforts fostering retention of

cranial nerve function (10,11).

For PGLs at the jugular foramen, the reported rates

of total resection vary (83-90%), depending on published sources

(7-9,12,13).

Conventional surgical procedures are more disruptive in general,

calling for external auditory canal closure and facial nerve

manipulation. Risks of cranial nerve palsy, dysphagia and

cerebrospinal fluid leakage are thereby increased. To minimize such

hazards (especially in large tumors) and preserve cranial nerve

function, a subtotal resection is often preferred (10,14-16).

A number of studies have confirmed that a subtotal resection not

only provides tumor stability or volume reduction, but also helps

safeguard critical neurovascular structures (10,14-18).

Huy et al (18) analyzed

patients after treatment with a combined subtotal resection and

adjuvant radiotherapy. Although some (27%) experienced regrowth,

which was curtailed through additional therapy, the majority (73%)

showed residual tumor stability (18). This combination approach maintains

a balance between tumor removal and functional preservation.

The decision to combine a subtotal resection with

radiotherapy should be based on the size and location of the tumor,

and the presence or absence of neurological symptoms. In a study of

47 patients with tumors classified as Fisch C or D (19), a subtotal resection was the more

frequent choice in patients who were elderly or had no preoperative

neurological deficits (20).

Another study involving 56 patients found that a subtotal resection

was often performed in the context of advanced tumors classified as

Fisch C3 or D (21).

Radiotherapy is particularly suitable for elderly

patients or for those with comorbidities, as it is less invasive

and carries fewer complications (11,22-25).

The patient in the present study showed complete tumor-related

brainstem compression, so postoperative complications seemed

unavoidable. Radiotherapy alone was therefore chosen as the primary

treatment method.

The principal dosimetric advantage of PBT lies in

the physical properties of the Bragg peak. This allows for the

delivery of high-dose, conformal radiation to the tumor while

largely sparing adjacent OARs from the broader low-dose ‘bath’

associated with intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT), which

may intensify long-term toxicity risk (26,27).

This capability is vital for sensitive structures such as the

brainstem, cochlea and salivary glands. Several dosimetric studies

have confirmed that PBT can significantly lower radiation doses to

these critical structures, thereby reducing risks of hearing

impairment, xerostomia and hypothyroidism, with some evidence

suggesting improved long-term survival (26,27).

Furthermore, the IMPT with PBS utilized in the

present case represents the most advanced form of PBT. Unlike older

passive scattering techniques, PBS employs a fine proton pencil

beam that is magnetically scanned across the tumor layer-by-layer

(11). This technology creates

exceptionally steep dose gradients, providing superior dose

conformality and the ability to pre-set tolerable doses for OARs,

ensuring an optimal dose distribution that further minimizes

exposure compared with traditional broad-beam PBT. This level of

precision is particularly advantageous when treating tumors in

complex anatomical regions, such as the skull base (27,28).

However, these dosimetric advantages must be weighed

against practical limitations. The primary disadvantages of PBT are

its substantially higher cost and limited availability. Moreover,

its precision makes it highly sensitive to positional uncertainties

arising from patient setup or physiological motion. Such shifts can

alter the position of the Bragg peak, potentially undermining

target coverage and the OAR-sparing benefit (26). Therefore, rigorous quality

assurance, such as the daily CBCT used in this case, is essential

to mitigate these risks (27,28).

In contrast to PBT, while IMRT is dosimetrically inferior in terms

of OAR sparing, it is more widely accessible, less costly and

offers greater robustness against tumor motion, making it a more

tolerant option for such uncertainties.

Stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) and IMRT my offer

high local control rates but often confer more risk in terms of

acute and late toxicities, owing to limited dose modulation in

surrounding tissues (22,29,30).

Despite the reported efficacy of SRS in controlling PGLs, acute

side effects, such as headache and fatigue, and late toxicities,

including dysphagia and otalgia, have resulted (30,31).

PBT is broadly categorized as broad-beam methodology

and IMPT. Various studies have reported the efficacy of PBT

treatment in patients with PGLs (27,28).

During one single-center trial, a median dose of 50.4 GyE over

25-34 fractions reduced tumor volumes by ≥20% in 40% of patients

with HNPGLs (28). A second study

similarly documented 100% local control in 10 patients receiving

45-67 Gy [median, 50.4 gray equivalents (GyE)] who were followed up

for a median of 24.6 months (26).

Yet another study (median follow-up time, 50.1 months) showed 100%

local disease control after irradiation at 50.4 GyE (32). The aforementioned findings imply

that local tumor control is attainable at doses of ~50 GyE.

However, in treating malignant PGLs of high grade or with recurrent

features, doses of 54-60 Gy may be warranted (22,33-35).

For greater precision in dose delivery, IMPT by PBS

was used in the present case, rather than engaging conventional

broad-beam techniques. Earlier efforts at PBT use in patients with

PGL have deployed broad-beam methods alone, without this advanced

PBS technology. As in IMRT, PBS allows for pre-defined dose

constraints on nearby normal tissues and augmented dose conformity

to the CTV, minimizing adjacent critical organ exposure (26-28).

Moreno et al (36) reported respective differences in

dose distribution characteristics of broad-beam and PBS methods,

emphasizing that PBS allows for more flexible adjustment of the

spread-out Bragg peak (SOBP) along the beam axis (36). By contrast, broad-beam techniques

utilize ridge filters to generate a uniform SOBP, which may result

in excessive radiation to surrounding tissues if the shape of the

CTV is suboptimal (37,38). PBS instead may deliver individually

modulated spots tailored to tumor shape, forming an SOBP that

follows tumor contours more precisely. The combination of IMPT and

PBS permits focal dose escalation to the tumor center and spares

normal tissues at the perimeter (39,40).

In the present patient, tumor shrinkage was observed

relatively early after PBS irradiation, coupled with symptomatic

improvement. Given the tumor's proximity to the brainstem and the

overt prognostic devastation dealt by cranial nerve dysfunction,

these extraordinary results may underscore the utility of PBS-based

proton therapeutics in treating similar cases.

Beyond dosimetric considerations, practical factors,

such as treatment cost and duration, also influence modality

selection. Within China, PBT (vs. IMRT) is associated with

substantially higher costs (US $40,000 vs. US $4,000-14,000) and

prolonged treatment sessions (30-45 min vs. 15-20 min) (41). Patient selection is therefore

paramount. PBT is preferentially recommended for specific patient

populations, including children and young adults in whom long-term

growth, development and radiation-induced secondary malignancy

risks are major concerns. PBT is also an ideal option in instances

where tumors border critical OARs or where cost is not an issue.

Conversely, IMRT may be more appropriate for patients with limited

life expectancies, certain tumor profiles (large, superficial or

highly mobile), or dire economic prospects (42).

To minimize the risk of radiation-induced toxicity,

strict dose constraints were applied during PBT in the present

study. The fractionation scheme was designed to achieve tumor

shrinkage and impart clinical improvement, both deemed essential to

therapeutic optimization. Fig. 1

delineates the patient's treatment regimen, including the

prescribed doses and aforementioned constraints.

In reviewing the current literature, a trend towards

less invasive, function-preserving strategies for recurrent jugular

foramen PGLs is clear, especially when surgical options are

exhausted (20-24).

The present report contributes to the limited but growing body of

evidence supporting the use of advanced radiation therapies for

this rare and complex condition.

However, the limitations of the present study must

be acknowledged. As a single case report, strong conclusions cannot

be drawn, and the favorable outcomes observed in the patient cannot

be generalized to the entire population of patients with this

disease. This highlights a significant potential research gap:

there is a lack of large-scale, prospective studies to define the

optimal radiation dose, fractionation and long-term outcomes for

anaplastic PGLs treated with PBT.

Additionally, it should be noted that the specific

immunohistochemical findings for the recurrent tumor described

within the present case were extracted from the official clinical

pathology reports, as the original slide image files from the

external institution were no longer retrievable due to the passage

of time.

Therefore, our future recommendations include the

establishment of multi-center registries to collect more data on

these rare tumors. Further studies with extended follow-up are

essential to fully assess the long-term efficacy and safety of PBT,

to confirm its benefits in preserving neurocognitive function and

to evaluate the risk of late-onset toxicities or secondary

malignancies. Such research will be crucial to solidifying the role

of PBT in the treatment algorithm for similar cases.

In conclusion, the present case highlights the

clinical challenges imposed by the recurrence of PGL at the jugular

foramen. Surgery remains a cornerstone of treatment but is clearly

quite limited under these circumstances. Proton therapy,

particularly if delivered via PBS and hypofractionated regimens,

offers an effective and precise alternative modality that may

protect critical structures while ensuring meaningful tumor

control. Long-term follow-up is essential to monitor disease

progression and evaluate the durability of outcomes post-treatment.

However, the merit of advanced proton therapy techniques in such

complex scenarios stems from compelling evidence and is hard to

deny.

Supplementary Material

Pathological findings from the second

surgery (recurrence). (A) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining

(original magnification, x100) showing tumor cells arranged in a

characteristic nested pattern (‘Zellballen’) separated by a rich

capillary network. (B) Immunohistochemical staining showing tumor

cells positive for CD56 (original magnification, x200). (C) Tumor

cells showing strong positivity for chromogranin A (original

magnification, x200). (D) The Ki-67 proliferation index is low at

3-7% (original magnification, x200). (E) S-100 protein staining

highlighting the sustentacular cells surrounding the tumor nests

(original magnification, x200).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: This study was supported by institutional funds from

Hebei Yizhou Cancer Hospital (Zhuozhou, China).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study are included

in the figures and/or tables of this article.

Authors' contributions

SS was responsible for conceptualization,

supervision, methodology, validation, project administration and

manuscript writing (reviewing/editing). WW was responsible for

conceptualization, data curation, investigation and manuscript

writing (original draft). SS and WW confirm the authenticity of all

the raw data. YY performed the formal data analysis, investigation

and manuscript writing (review/editing). JB was responsible for

methodology and data analysis. YZ assisted with resources and data

collection. DZ assisted in investigation and data curation. JZ

assisted with resources and follow-up data collection. SZ performed

data integration and visualization. ZW and JW were responsible for

radiotherapy dose data acquisition and software use. JK performed

data organization and visualization. LY was responsible for formal

analysis and manuscript writing (reviewing/editing). MM assisted in

investigation and data validation. HS was responsible for the

methodology and conceptualization. All authors took part in the

direct clinical care of the patient, and each author contributed

significantly to the data collection, dose acquisition or formal

analysis processes. All authors have read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All procedures involving human participants complied

with ethical standards of applicable institutional and national

research committees, and with the principles of the 1964

Declaration of Helsinki, its later amendments or comparable ethical

standards. This case report was approved by the Institutional

Review Board of Hebei Yizhou Cancer Hospital (Zhuozhou, China).

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient. Although

some journals may not require formal ethics approval for a single

case report, it is the policy of Hebei Yizhou Cancer Hospital to

obtain such approval for any publication involving patient data to

ensure the highest standards of patient privacy protection and

ethical conduct.

Patient consent for publication

The patient depicted herein granted written informed

consent for publication of this case report and its accompanying

images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Use of artificial intelligence tools

During the preparation of this work, AI tools were

used to improve the readability and language of the manuscript or

to generate images, and subsequently, the authors revised and

edited the content produced by the AI tools as necessary, taking

full responsibility for the ultimate content of the present

manuscript.

References

|

1

|

Palade DO, Hainarosie R, Zamfir A,

Vrinceanu D, Pertea M, Tusaliu M, Mocanu F and Voiosu C:

Paragangliomas of the head and neck: A review of the latest

diagnostic and treatment methods. Medicina (Kaunas).

60(914)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Strasser V and Steinbichler T:

Paragangliomas of the head and neck. Radiologie (Heidelb).

64:960–970. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar : (In German).

|

|

3

|

Mete O, Asa SL, Gill AJ, Kimura N, de

Krijger RR and Tischler A: Overview of the 2022 WHO classification

of paragangliomas and pheochromocytomas. Endocr Pathol. 33:90–114.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Sethi RV, Sethi RK, Herr MW and Deschler

DG: Malignant head and neck paragangliomas: Treatment efficacy and

prognostic indicators. Am J Otolaryngol. 34:431–438.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Brewczyński A, Kolasińska-Ćwikła A,

Jabłońska B and Wyrwicz L: Pheochromocytomas and

paragangliomas-current management. Cancers (Basel).

17(1029)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Strasser V and Steinbichler T:

Paragangliome im Kopf-Hals-Bereich Paragangliomas of the head and

neck. HNO. 72:598–608. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar : (In German).

|

|

7

|

Moe KS, Li D, Linder TE, Schmid S and

Fisch U: An update on the surgical treatment of temporal bone

paraganglioma. Skull Base Surg. 9:185–194. 1999.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Sanna M, Jain Y, De Donato G, Rohit Lauda

L and Taibah A: Management of jugular paragangliomas: The Gruppo

Otologico experience. Otol Neurotol. 25:797–804. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Jackson CG, McGrew BM, Forest JA,

Netterville JL, Hampf CF and Glasscock ME III: Lateral skull base

surgery for glomus tumors: Long-term control. Otol Neurotol.

22:377–382. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Manzoor NF, Yancey KL, Aulino JM, Sherry

AD, Khattab MH, Cmelak A, Morrel WG, Haynes DS, Bennett ML,

O'Malley MR, et al: Contemporary management of jugular

paragangliomas with neural preservation. Otolaryngol Head Neck

Surg. 164:391–398. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Chuong M, Badiyan SN, Yam M, Li Z, Langen

K, Regine W, Morris C, Snider J III, Mehta M, Huh S, et al: Pencil

beam scanning versus passively scattered proton therapy for

unresectable pancreatic cancer. J Gastrointest Oncol. 9:687–693.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Manolidis S, Jackson CG, Von Doersten PG,

Pappas D and Glasscock ME: Lateral skull base surgery: The otology

group experience. Skull Base Surg. 7:129–137. 1997.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Borba LA, Araújo JC, de Oliveira JG, Filho

MG, Moro MS, Tirapelli LF and Colli BO: Surgical management of

glomus jugulare tumors: A proposal for approach selection based on

tumor relationships with the facial nerve. J Neurosurg. 112:88–98.

2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

de Brito R, Cisneros Lesser JC, Lopes PT

and Bento RF: Preservation of the facial and lower cranial nerves

in glomus jugulare tumor surgery: Modifying our surgical technique

for improved outcomes. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 275:1963–1969.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Wanna GB, Sweeney AD, Carlson ML, Latuska

RF, Rivas A, Bennett ML, Netterville JL and Haynes DS: Subtotal

resection for management of large jugular paragangliomas with

functional lower cranial nerves. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg.

151:991–995. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Li D, Zeng XJ, Hao SY, Wang L, Tang J,

Xiao XR, Meng GL, Jia GJ, Zhang LW, Wu Z and Zhang JT:

Less-aggressive surgical management and long-term outcomes of

jugular foramen paragangliomas: A neurosurgical perspective. J

Neurosurg. 125:1143–1154. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Anderson JL, Khattab MH, Anderson C,

Sherry AD, Luo G, Manzoor N, Attia A, Netterville J and Cmelak AJ:

Long-term outcomes for the treatment of paragangliomas in the

upfront, adjuvant, and salvage settings with stereotactic

radiosurgery and intensity-modulated radiotherapy. Otol Neurotol.

41:133–140. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Huy PT, Kania R, Duet M, Dessard-Diana B,

Mazeron JJ and Benhamed R: Evolving concepts in the management of

jugular paraganglioma: A comparison of radiotherapy and surgery in

88 cases. Skull Base. 19:83–91. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Fisch U and Mattox D: Microsurgery of the

Skull Base. Thieme, Stuttgart, 1988.

|

|

20

|

Tran Ba Huy P, Chao PZ, Benmansour F and

George B: Long-term oncological results in 47 cases of jugular

paraganglioma surgery with special emphasis on the facial nerve

issue. J Laryngol Otol. 115:981–987. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Zhao P, Zhang Y, Lin F, Kong D, Feng Y and

Dai C: Comparison of surgical outcomes between early and advanced

class of jugular paragangliomas following application of our

modified surgical techniques. Sci Rep. 13(885)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Lassen-Ramshad Y, Ozyar E, Alanyali S,

Poortmans P, van Houtte P, Sohawon S, Esassolak M, Krengli M, Villa

S, Miller R, et al: Paraganglioma of the head and neck region,

treated with radiation therapy, a Rare Cancer Network study. Head

Neck. 41:1770–1776. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Sharma M, Meola A, Bellamkonda S, Jia X,

Montgomery J, Chao ST, Suh JH, Angelov L and Barnett GH: Long-term

outcome following stereotactic radiosurgery for glomus jugulare

tumors: A single institution experience of 20 years. Neurosurgery.

83:1007–1014. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Jansen TTG, Kaanders JHAM, Beute GN,

Timmers HJLM, Marres HAM and Kunst HPM: Surgery, radiotherapy or a

combined modality for jugulotympanic paraganglioma of Fisch class C

and D. Clin Otolaryngol. 43:1566–1572. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Suárez C, Rodrigo JP, Bödeker CC, Llorente

JL, Silver CE, Jansen JC, Takes RP, Strojan P, Pellitteri PK,

Rinaldo A, et al: Jugular and vagal paragangliomas: Systematic

study of management with surgery and radiotherapy. Head Neck.

35:1195–1204. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Cao KI, Feuvret L, Herman P, Bolle S,

Jouffroy T, Goudjil F, Amessis M, Rodriguez J, Dendale R and

Calugaru V: Proton therapy of head and neck paragangliomas: A

monocentric study. Cancer Radiother. 22:31–37. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Chartier J, Beddok A, Cao KI, Feuvret L,

Herman P, Bolle S, Goudjil F, Sauvaget E, Choussy O, Dendale R and

Calugaru V: Protontherapy to maintain local control of head and

neck paragangliomas. Acta Oncol. 62:400–403. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Kang KH, Lebow ES, Niemierko A, Bussière

MR, Dewyer NA, Daly J, McKenna MJ, Lee DJ, Loeffler JS, Busse PM

and Shih HA: Proton therapy for head and neck paragangliomas: A

single institutional experience. Head Neck. 42:670–677.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Gottfried ON, Liu JK and Couldwell WT:

Comparison of radiosurgery and conventional surgery for the

treatment of glomus jugulare tumors. Neurosurg Focus.

17(E4)2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Ehret F, Ebner DK, McComas KN, Gogineni E,

Andraos T, Kim M, Lo S, Schulder M, Redmond KJ, Muacevic A, et al:

The Radiosurgery Society case-based discussion of the management of

head and neck or skull base paragangliomas with stereotactic

radiosurgery and radiotherapy. Pract Radiat Oncol. 14:225–233.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Fatima N, Pollom E, Soltys S, Chang SD and

Meola A: Stereotactic radiosurgery for head and neck

paragangliomas: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosurg

Rev. 44:741–752. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Henzel M, Hamm K, Gross MW, Surber G,

Kleinert G, Failing T, Sitter H, Strassmann G and

Engenhart-Cabillic R: Fractionated stereotactic radiotherapy of

glomus jugulare tumors. Local control, toxicity, symptomatology,

and quality of life. Strahlenther Onkol. 183:557–562.

2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Bianchi LC, Marchetti M, Brait L,

Bergantin A, Milanesi I, Broggi G and Fariselli L: Paragangliomas

of head and neck: A treatment option with CyberKnife radiosurgery.

Neurol Sci. 30:479–485. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Gilbo P, Morris CG, Amdur RJ, Werning JW,

Dziegielewski PT, Kirwan J and Mendenhall WM: Radiotherapy for

benign head and neck paragangliomas: A 45-year experience. Cancer.

120:3738–3743. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Galland-Girodet S, Maire JP, De-Mones E,

Benech J, Bouhoreira K, Protat B, Demeaux H, Darrouzet V and Huchet

A: The role of radiation therapy in the management of head and neck

paragangliomas: Impact of quality of life versus treatment

response. Radiother Oncol. 111:463–467. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Moreno AC, Frank SJ, Garden AS, Rosenthal

DI, Fuller CD, Gunn GB, Reddy JP, Morrison WH, Williamson TD,

Holliday EB, et al: Intensity modulated proton therapy (IMPT) - The

future of IMRT for head and neck cancer. Oral Oncol. 88:66–74.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Paganetti H: Range uncertainties in proton

therapy and the role of Monte Carlo simulations. Phys Med Biol.

57:R99–R117. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Akagi T, Kanematsu N, Takatani Y, Sakamoto

H, Hishikawa Y and Abe M: Scatter factors in proton therapy with a

broad beam. Phys Med Biol. 51:1919–1928. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Reese AS, Das SK, Kirkpatrick JP and Marks

LB: Quantifying the dosimetric trade-offs when using

intensity-modulated radiotherapy to treat concave targets

containing normal tissues. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys.

73:585–593. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Kaulfers T, Lattery G, Cheng C, Zhao X,

Selvaraj B, Wu H, Chhabra AM, Choi JI, Lin H, Simone CB II, et al:

Pencil beam scanning proton bragg peak conformal FLASH in prostate

cancer stereotactic body radiotherapy. Cancers (Basel).

16(798)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Li G, Qiu B, Huang YX, Doyen J, Bondiau

PY, Benezery K, Xia YF and Qian CN: Cost-effectiveness analysis of

proton beam therapy for treatment decision making in paranasal

sinus and nasal cavity cancers in China. BMC Cancer.

20(599)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Paganetti H, Athar BS, Moteabbed M, Adams

JY, Schneider U and Yock TI: Assessment of radiation-induced second

cancer risks in proton therapy and IMRT for organs inside the

primary radiation field. Phys Med Biol. 57:6047–6061.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|