Introduction

Lumbar disc herniation (LDH) is a prevalent spinal

disorder and a major cause of global disability, as evidenced by

its marked associated healthcare expenditures and economic burden

(1). When conservative management

proves ineffective, surgical intervention becomes necessary

(2,3). The advent of minimally invasive spine

surgery (MISS) has notably transformed treatment paradigms, with

endoscopic techniques gaining prominence for their ability to

minimize tissue trauma and enable precise decompression (4).

Selecting the optimal MISS approach for LDH remains

a subject of debate (5).

Transforaminal endoscopic lumbar discectomy, pioneered by Kambin

and Sampson (6) and based on the

anatomical concept of Kambin's triangle, has demonstrated

effectiveness but is typically limited at the L5-S1 level due to

high iliac crest obstruction and the restricted working corridor

within the safe zone (7).

Consequently, the interlaminar approach has emerged as a valuable

alternative, using the natural anatomical window of the

interlaminar space to overcome osseous restrictions. This method

provides improved access for central and L5-S1 herniations and has

facilitated the development of techniques such as percutaneous

endoscopic interlaminar discectomy (PEID) and unilateral biportal

endoscopic discectomy (UBE) (8,9).

Although both PEID and UBE employ the interlaminar

approach and have yielded favorable outcomes, direct comparative

evidence regarding their efficacy and safety profiles within this

shared surgical corridor remains limited (10). Therefore, the present meta-analysis

aimed to compare UBE and PEID regarding surgical efficiency,

including operative time, intraoperative blood loss, hospital stay

length and fluoroscopy frequency, functional outcomes including

MacNab excellent/good rate (11),

back and leg visual analog scale (VAS) scores (12) and Oswestry Disability Index (ODI)

(13), and safety-complication

rates. The present study aimed to provide evidence-based guidance

for clinical decision-making in selecting the most appropriate

surgical technique.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

A comprehensive systematic literature search was

conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for

Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (14). The search encompassed four major

electronic databases: PubMed (U.S. National Library of Medicine,

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), Web

of Science (Clarivate Analytics platform, https://www.webofscience.com/), Embase (Elsevier,

https://www.embase.com) and the Cochrane Library

(Wiley, https://www.cochranelibrary.com/). The search period

spanned from the inception of each database to June 10, 2025. The

strategy combined Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and free-text

terms using Boolean operators (AND/OR). For example, the PubMed

search syntax was as follows: (‘Unilateral Biportal

Endoscopy’[MeSH] OR ‘Biportal Endoscopic’[tiab] OR UBE[tiab] OR

UBED[tiab]) AND (‘Percutaneous Endoscopy’[MeSH] OR ‘Percutaneous

Endoscopic Interlaminar Discectomy’[tiab] OR PEID[tiab] OR

PELD[tiab]) AND (‘Lumbar Disc Herniation’[MeSH] OR ‘Lumbar

Intervertebral Disc’[tiab] OR LDH[tiab]). Additionally, the

reference lists of relevant reviews were screened to identify

potentially eligible studies.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were as follows: i) Comparative

studies of UBE vs. PEID performed exclusively using the

interlaminar approach for single-level LDH; ii) retrospective or

prospective cohort studies or randomized controlled trials and iii)

publications in English. Exclusion criteria were as follows: i)

Prior lumbar surgery or multi-level LDH; ii) comorbidity, such as

infection, tuberculosis, psychiatric disorders or neoplasms; iii)

non-primary literature (reviews, case reports or conference

abstracts); iv) studies with inaccessible outcome data and v)

procedures not utilizing the interlaminar approach.

Data extraction and quality

assessment

Data were extracted by two independent investigators

regarding study characteristics (first author, study design,

country, sample size, sex, age, BMI and operative levels) and

outcome parameters (operative time, blood loss, fluoroscopy

frequency, hospital stay duration, VAS for back and leg pain, ODI,

modified MacNab criteria with excellent rate and complication

rates). Study quality was evaluated using the Newcastle-Ottawa

Scale (NOS) (15) with

discrepancies resolved through discussion or arbitration by a third

author.

Statistical analysis

Meta-analyses were conducted using Review Manager

(RevMan; version 5.4; The Cochrane Collaboration). Dichotomous

variables (MacNab excellent/good rate and complication rates) were

analyzed using odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CIs. Continuous variables

(operative time, VAS and ODI) were analyzed using mean difference

(MD) or standardized MD (SMD) with 95% CIs. MDs were preferred when

outcomes were measured on identical scales across studies, whereas

SMDs were applied when outcomes were reported on different scales.

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference and heterogeneity was quantified using the I2

statistic. In accordance with the recommendations of the Cochrane

Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (16), a random-effects model was applied

to all meta-analyses to incorporate the expected heterogeneity of

intervention effects across studies from different settings.

Sensitivity or subgroup analyses were conducted to explore

potential sources of heterogeneity sources. Publication bias was

assessed using funnel plots and Egger's regression test.

Results

Search results

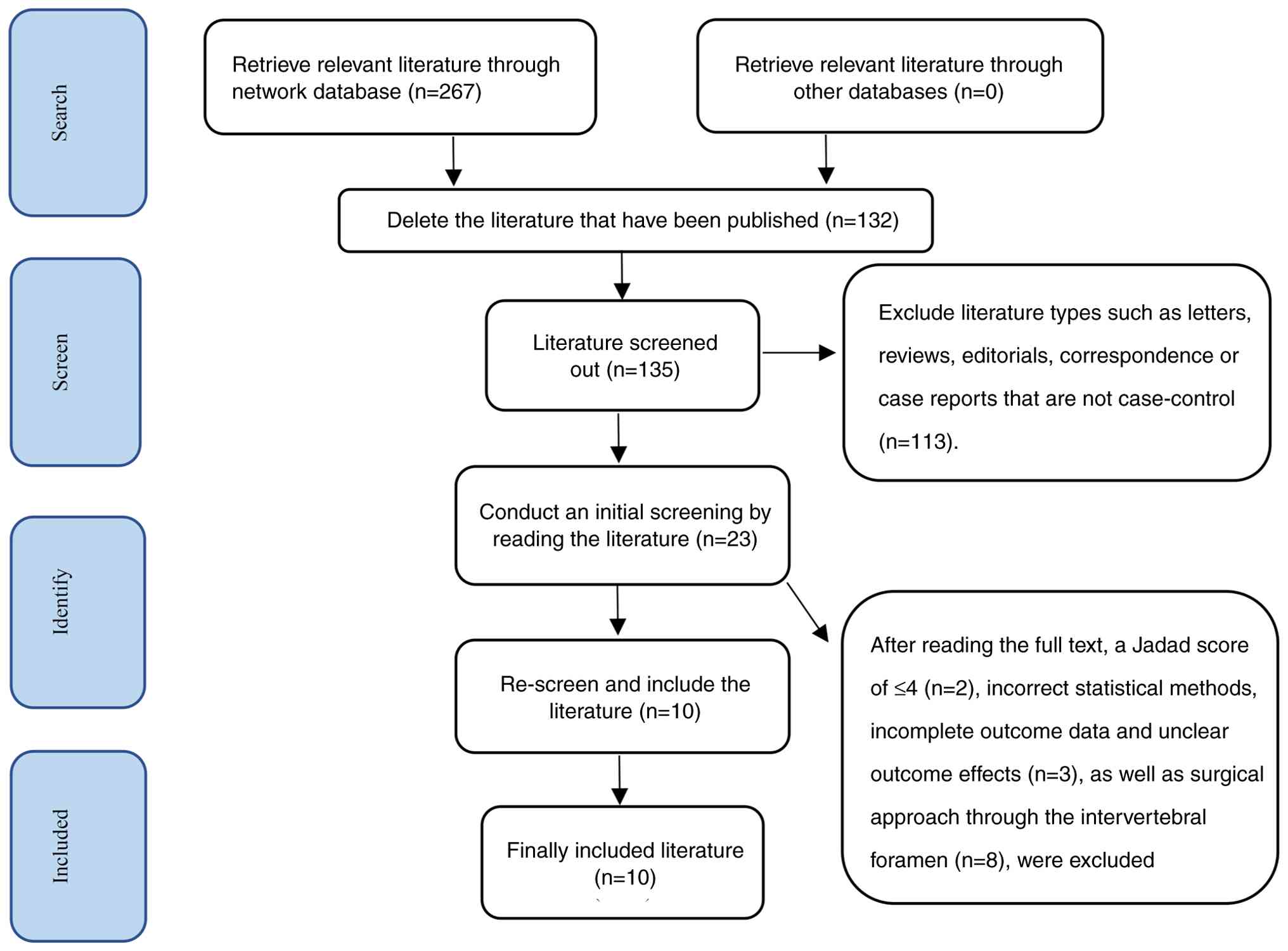

According to the predefined search strategy, a total

of 267 records were retrieved from Embase, the Cochrane Library,

PubMed and Web of Science databases. After removing 132 duplicate

entries, 135 unique records remained. Following a review of titles

and abstracts, 112 records were excluded. The remaining 23 studies

underwent full-text evaluation, of which 13 were excluded based on

the eligibility criteria. Ultimately, 10 studies were included in

the present meta-analysis (Fig. 1)

(17-26).

Basic characteristics of included

studies

Within the 10 included studies, the following

outcomes were reported; i) Operative time (n=10) (17-26);

ii) blood loss (n=5) (17-20,22);

iii) hospital stay duration (n=5) (17,18,20,21,23);

iv) fluoroscopy frequency (n=5) (18,19,23-25)

v) back and leg VAS score (n=10) (17-26);

vi) MacNab criteria with excellent/good rate (n=7) (17-22,24)

and vii) complication rates (n=6) (18-20,23-25).

In total, the studies encompassed 1,003 patients (514 male and 489

female). Detailed study characteristics are presented in Tables I and II.

| Table IBasic information on included

retrospective studies. |

Table I

Basic information on included

retrospective studies.

| First author,

year | Country | Group | Sample size

(M/F) | Mean age,

years | BMI,

kg/m2 | Operation level

(n) | Mean fluoroscopy

frequency, n | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Wang et al,

2025 | China | UBE | 18 (10/8) | 40.94±13.73 | 24.51±3.12 | L2-3(1); L4-5(12);

L5-S1(11) | NR | (17) |

| | | PEID | 21 (14/7) | 42.33±11.63 | 23.14±3.83 | L2-3 (0); L4-5(6);

L5-S1(15) | NR | |

| Xiao et al,

2025 | China | UBE | 84 (45/39) | 53.46±15.60 | 24.17±2.94 | L3-4(4); L4-5(52);

L5-S1(28) | 4.06±4.63 | (18) |

| | | PEID | 62 (23/39) | 55.61±15.52 | 23.90±2.61 | L3-4(3); L4-5(37);

L5-S1(21) | 7.72±3.35 | |

| Guo et al,

2025 | China | UBE | 79 (43/36) | 47.35±14.07 | 22.51±2.38 | L4-5(38);

L5-S1(38); other (3) | 3.28±1.67 | (19) |

| | | PEID | 94 (52/42) | 44.03±14.19 | 22.99±2.06 | L4-5(44);

L5-S1(44); other (6) | 2.99±1.04 | |

| Yin et al,

2025 | China | UBE | 46 (29/17) | 43.85±11.41 | 24.83±3.92 | L5-S1(50) | NR | (20) |

| | | PEID | 50 (27/23) | 45.64±13.60 | 24.70±4.24 | L5-S1(46) | NR | |

| Qian et al,

2024 | China | UBE | 15 (8/7) | 36.27±11.11 | 21.93±2.12 | L4-5(4);

L5-S1(11) | NR | (21) |

| | | PEID | 26 (18/8) | 35.15±9.30 | 22.38±1.75 | L4-5(12);

L5-S1(14) | NR | |

| Yang et al,

2024 | China | UBE | 33 (18/15) | 43.60±15.80 | NR | L4-5(11);

L5-S1(22) | NR | (22) |

| | | PEID | 66 (36/30) | 44.70±12.90 | NR | L4-5(22);

L5-S1(44) | NR | |

| Wei et al,

2024 | China | UBE | 55 (19/36) | 56.89±15.01 | 26.88±4.13 | L4-5 (NR); L5-S1

(NR) | 3.51±0.63 | (23) |

| | | PEID | 60 (23/37) | 57.19±14.25 | 27.06±4.93 | L4-5 (NR); L5-S1

(NR) | 3.28±0.66 | |

| Wu et al,

2024 | China | UBE | 31 (16/15) | 58.50±13.20 | 24.10±3.00 | L4-5(17);

L5-S1(14) | 3.40±0.90 | (24) |

| | | PEID | 65 (29/36) | 57.60±16.80 | 25.00±2.90 | L4-5(35);

L5-S1(30) | 4.80±1.00 | |

| Wang et al,

2023 | China | UBE | 51 (22/29) | 43.80±14.20 | 25.40±3.70 | L5-S1(51) | 2.50±0.60 | (25) |

| | | PEID | 55 (28/27) | 42.30±3.80 | 25.80±3.60 | L5-S1(55) | 2.40±0.50 | |

| Zuo et al,

2022 | China | UBE | 42 (23/19) | 45.57±11.15 | NR | L5-S1(42) | NR | (26) |

| | | PEID | 50 (31/19) | 46.68±12.09 | NR | L5-S1(50) | NR | |

| Table IIIntraoperative data and postoperative

recovery indices. |

Table II

Intraoperative data and postoperative

recovery indices.

| First author,

year | Group | Mean operative

time, min | Mean blood loss,

ml | Mean hospital stay,

days | Back VAS score | Leg VAS score | ODI score | MacNab score

excellence rate, % | Complic ations,

n | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Wang et al,

2025 | UBE | 136.44±32.11 | 18.89±6.54 | 9.17±2.81 | Pre-op; postop day

1; | Pre-op; postop | Pre-op; postop day

1; | 94.44 | NR | (17) |

| | PEID | 104.86±35.74 | 7.14±2.99 | 6.95±1.69 | 1 and 3 month

postop | day 1; 1 and 3

month postop | 1 and 3 month

postop | 95.24 | NR | |

| Xiao et al,

2025 | UBE | 66.67±15.83 | 76.81±26.74 | 5.39±1.83 | Pre-op; 1, 6

and | NR | Pre-op; 1, 6

and | 91.70 | 5 | (18) |

| | PEID | 69.11±25.84 | 69.44±25.74 | 5.11±3.42 | 24 month

postop | NR | 24 month

postop | 87.10 | 20 | |

| Guo et al,

2025 | UBE | 116.52±47.20 | 80.19±22.81 | 7.34±2.36

(post) | Pre-op; postop | Pre-op; postop | Pre-op; postop day

1; | 96.20 | 7 | (19) |

| | PEID | 99.96±34.74 | 20.85±11.06 | 3.47±1.23

(post) | day 1; 3 and 6

month postop | day 1; 3 and 6

month postop | 3 and 6 month

postop | 94.68 | 8 | |

| Yin et al,

2025 | UBE | 80.98±33.61 | 394.16±227.96 | 5.54±1.92 | Pre-op; postop day

1; | Pre-op; postop day

1; | Pre-op; final | 97.80 | 2 | (20) |

| | PEID | 89.42±32.16 | 273.83±158.53 | 5.24±1.89 | final

follow-up | final

follow-up | follow-up | 96.00 | 2 | |

| Qian et al,

2024 | UBE | 133.07±10.46 | NR | 4.24±1.44 | Pre -op; 1, 3

and | Pre -op; 1, 3

and | Pre -op; 1, 3

and | 86.70 | NR | (21) |

| | PEID | 110.81±11.48 | NR | 2.73±1.28 | 6 month postop | 6 month postop | 6 month postop | 92.30 | NR | |

| Yang et al,

2024 | UBE | 100.80±36.10 | 9.90±3.40 | NR | Pre-op; postop | NR | Pre-op;

post-op | 97.00 | NR | (22) |

| | PEID | 86.00±19.40 | 5.50±2.30 | NR | | NR | | 95.50 | NR | |

| Wei et al,

2024 | UBE | 56.74±10.57 | NR | 7.50±2.12 | Pre-op; postop day

1; | Pre-op; postop day

1; | Pre-op; postopday

1; | NR | 1 | (23) |

| | PEID | 54.34±10.15 | NR | 7.18±2.30 | 1, 3, 6 and 12

month postop | 1, 3, 6 and 12

month postop | 1, 3, 6 and 12

month postop | NR | 1 | |

| Wu et al,

2024 | UBE | 77.30±20.40 | NR | 4.50±2.60

(post) | Pre-op; postop day

1; | Pre-op; postop day

1; | Pre-op; postop day

1; | 90.30 | 1 | (24) |

| | PEID | 65.80±15.90 | NR | 3.10±1.80

(post) | 1 and 6 month

postop; final follow-up | 1 and 6 month

postop; final follow-up | 1 and 6 month

postop; final follow-up | 84.60 | 2 | |

| Wang et al,

2023 | UBE | 83.60±10.80 | NR | 2.10±0.80

(post) | Pre-op; postop day

1; | Pre-op; postop day

1; | Pre-op; postop day

1; | NR | 3 | (25) |

| | PEID | 80.20±8.40 | NR | 2.00±0.80

(post) | 3 month postop;

final follow-up | 3 month postop;

final follow-up | 3-month postop;

final follow-up | NR | 2 | |

| Zuo et al,

2022 | UBE | 68.57±10.87 | NR | 6.88±1.85

(post) | Pre-op; postop day

3; | Pre-op; postop day

3; | Pre-op; postop day

3; | NR | NR | (26) |

| | | | | 7.36±4.62

(post) | 3, 6 and 12 month

postop | 3, 6 and 12 month

postop | 3, 6 and 12 month

postop | | | |

| | PEID | 65.6±15.24 | NR | | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

Quality evaluation of the included

studies

All 10 included studies were retrospective in

design, with no prospective studies identified. Study quality was

assessed using the NOS, whereby three studies scored 8 points and

seven scored 7 points. All studies met the high-quality threshold

(NOS score ≥7; Table III).

| Table IIIStudy evaluation using modified

Newcastle-Ottawa Scale. |

Table III

Study evaluation using modified

Newcastle-Ottawa Scale.

| First author,

year | Selection | Comparability | Exposure | Total score | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Wang et al,

2025 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 | (17) |

| Xiao et al,

2025 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 7 | (18) |

| Guo et al,

2025 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 | (19) |

| Yin et al,

2025 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 | (20) |

| Qian et al,

2024 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 | (21) |

| Yang et al,

2024 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 7 | (22) |

| Wei et al,

2024 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 | (23) |

| Wu et al,

2024 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 7 | (24) |

| Wang et al,

2023 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 8 | (25) |

| Zuo et al,

2022 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 8 | (26) |

Analysis of clinical outcomes.

Meta-analysis results of surgical efficiency

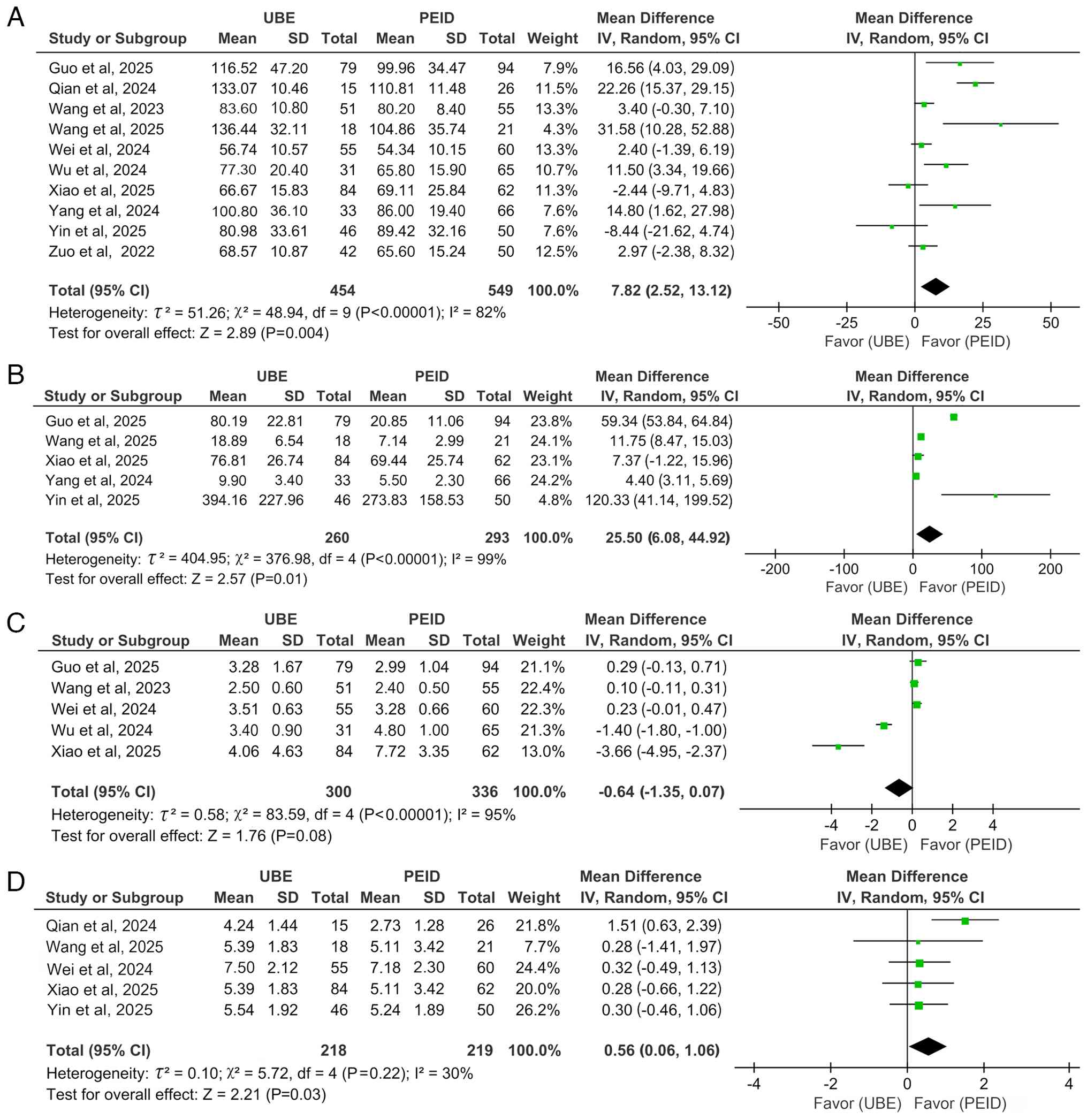

A pooled analysis of 10 studies (17-26)

comparing operative time demonstrated that PEID required a

significantly shorter operative time compared with UBE in the

treatment of LDH (MD=7.82; 95% CI: 2.52-13.12; P=0.004;

I2=82%; Fig. 2A).

Similarly, analysis of five studies (17-19,22,24)

on intraoperative blood loss showed that PEID was associated with a

significantly decreased blood loss (MD=25.50; 95% CI: 6.08-44.92;

P=0.01; I2=99%; Fig.

2B), also demonstrated through a random-effects model.

Furthermore, five studies (18,19,23-25)

comparing fluoroscopy frequency revealed no significant difference

between PEID and UBE (MD=-0.64; 95% CI: -1.35-0.07; P=0.08;

I2=95%), analyzed using a random-effects model (Fig. 2C).

In the comparison of hospital stay duration of UBE

and PEID, five studies (17,18,20,21,23)

demonstrated significantly shorter hospitalization with PEID

(MD=0.56; 95% CI: 0.06-1.06; P=0.03; I2=30%; Fig. 2D), analyzed using a random-effects

model.

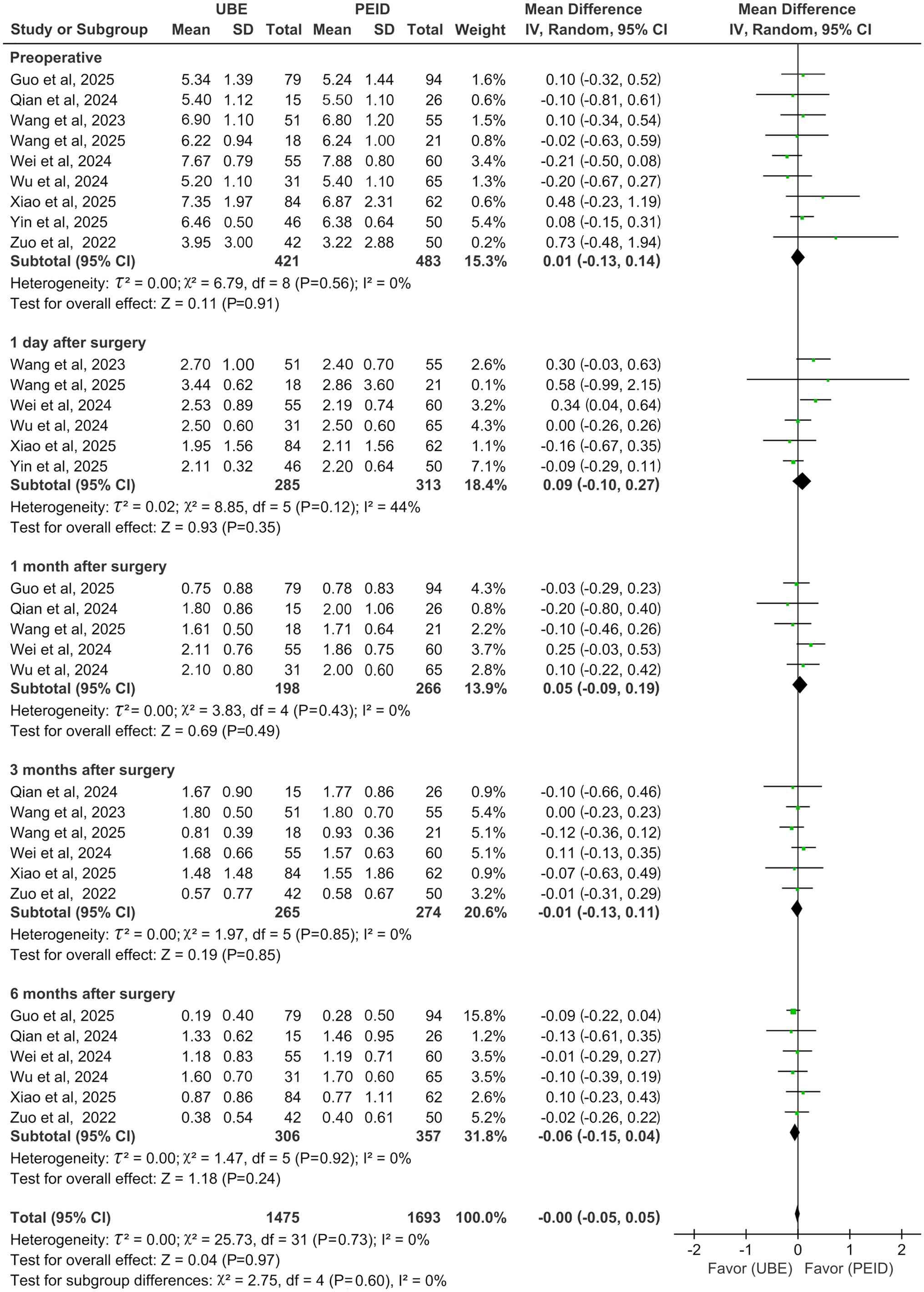

Meta-analysis results of functional outcomes.

Back VAS score showed no significant differences between UBE and

PEID at preoperative (MD=0.01; 95% CI: -0.13-0.14; P=0.91;

I2=0%) and postoperative day 1 (MD=0.09; 95% CI:

-0.10-0.27; P=0.35; I2=44%) and month 1 (MD=0.05; 95%

CI: -0.09-0.19; P=0.49; I2=0%), 3 (MD=-0.01; 95% CI:

-0.13-0.11; P=0.85; I2=0%) and 6 (MD=-0.06; 95% CI:

-0.15-0.04; P=0.24; I2=0%; Fig. 3), all analysed using a

random-effects model.

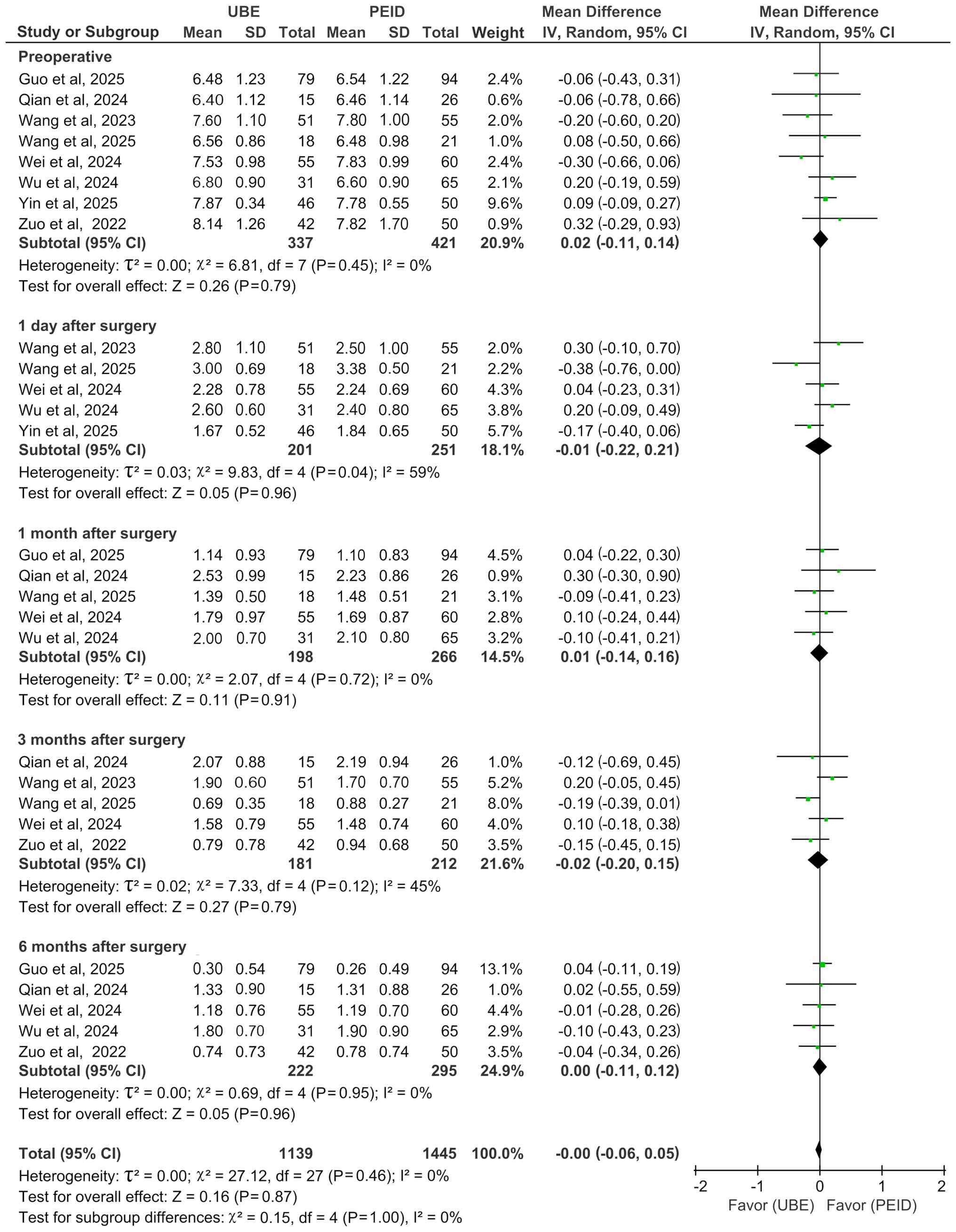

With regard to leg VAS score, no statistically

significant differences were observed between UBE and PEID at

preoperative (MD=0.02; 95% CI: -0.11-0.14; P=0.79;

I2=0%] and postoperative day 1 (MD=-0.01; 95% CI:

-0.22-0.21; P=0.96; I2=59%) and month 1 (MD=0.01; 95%

CI: -0.14-0.16; P=0.91; I2=0%), 3 (MD=-0.02; 95% CI:

-0.20-0.15; P=0.79; I2=45%) and 6 (MD=0.00; 95% CI:

-0.11-0.12; P=0.96; I2=0%; Fig. 4), with all analyses performed using

a random-effects model.

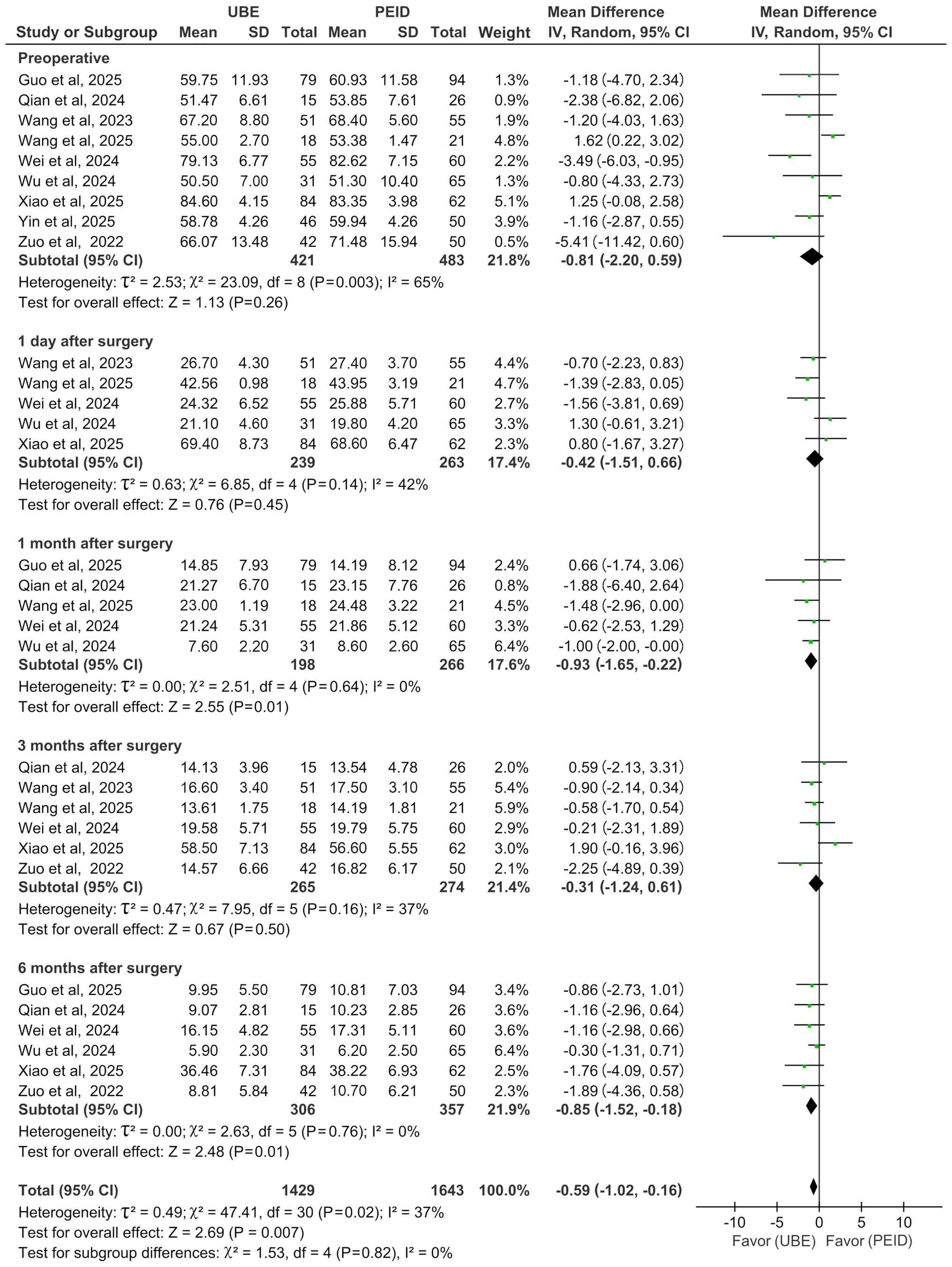

Preoperative ODI comparisons across nine studies

(17-21,23-26)

revealed no significant differences (MD=-0.81; 95% CI: -2.20-0.59;

P=0.26; I2=65%). Postoperative ODI analysis results were

as follows: Day 1 (17,18,23-25)

(MD=-0.42; 95% CI: -1.51-0.66; P=0.45; I2=42%) and month

1 (17,19,21,23,24)

(MD=-0.93; 95% CI: -1.65-0.22; P=0.01; I2=0%), 3

(17,18,21,23,25,26)

(MD=-0.31; 95% CI: -1.24-0.61; P=0.50; I2=37%) and 6

(18,19,21,23,24,26)

(MD=-0.85; 95% CI: -1.52-0.18; P=0.01; I2=0%; Fig. 5). UBE showed significant

superiority at 1 and 6 months (both P≤0.01) but not at

preoperative, postoperative day 1 or month 3. All analyses were

performed using a random-effects model (Fig. 5).

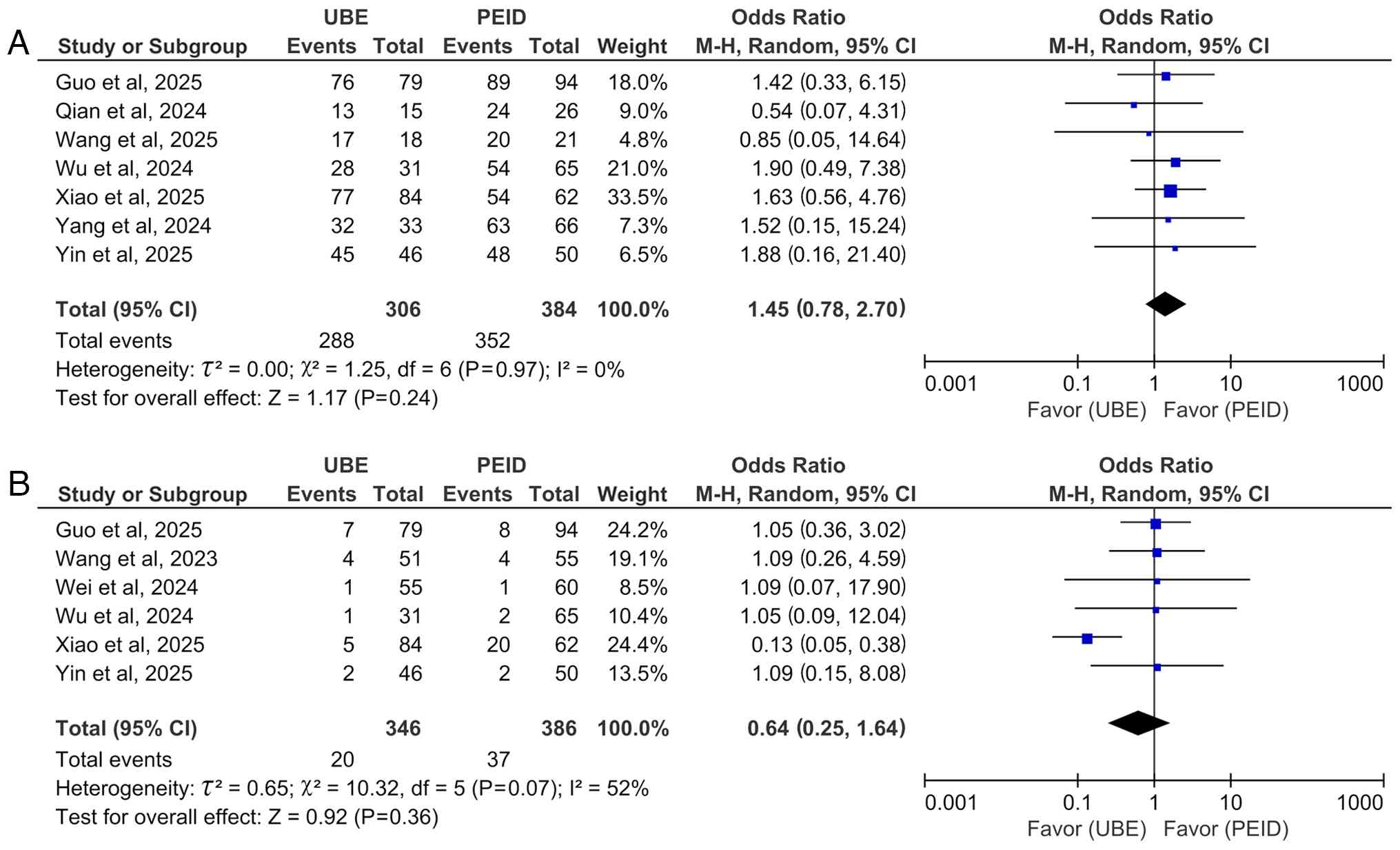

A total of seven studies (17-22,24)

comparing MacNab excellent/good rates showed no significant

difference between UBE and PEID groups (OR=1.45; 95% CI: 0.78-2.70;

P=0.24; I2=0%; Fig.

6A).

Meta-analysis of safety. A pooled analysis of

postoperative complications from six studies (18-20,23-25)

showed no significant difference between UBE and PEID (OR=0.64; 95%

CI: 0.25-1.64; P=0.36; I2=52%; Fig. 6B), using a random-effects

model.

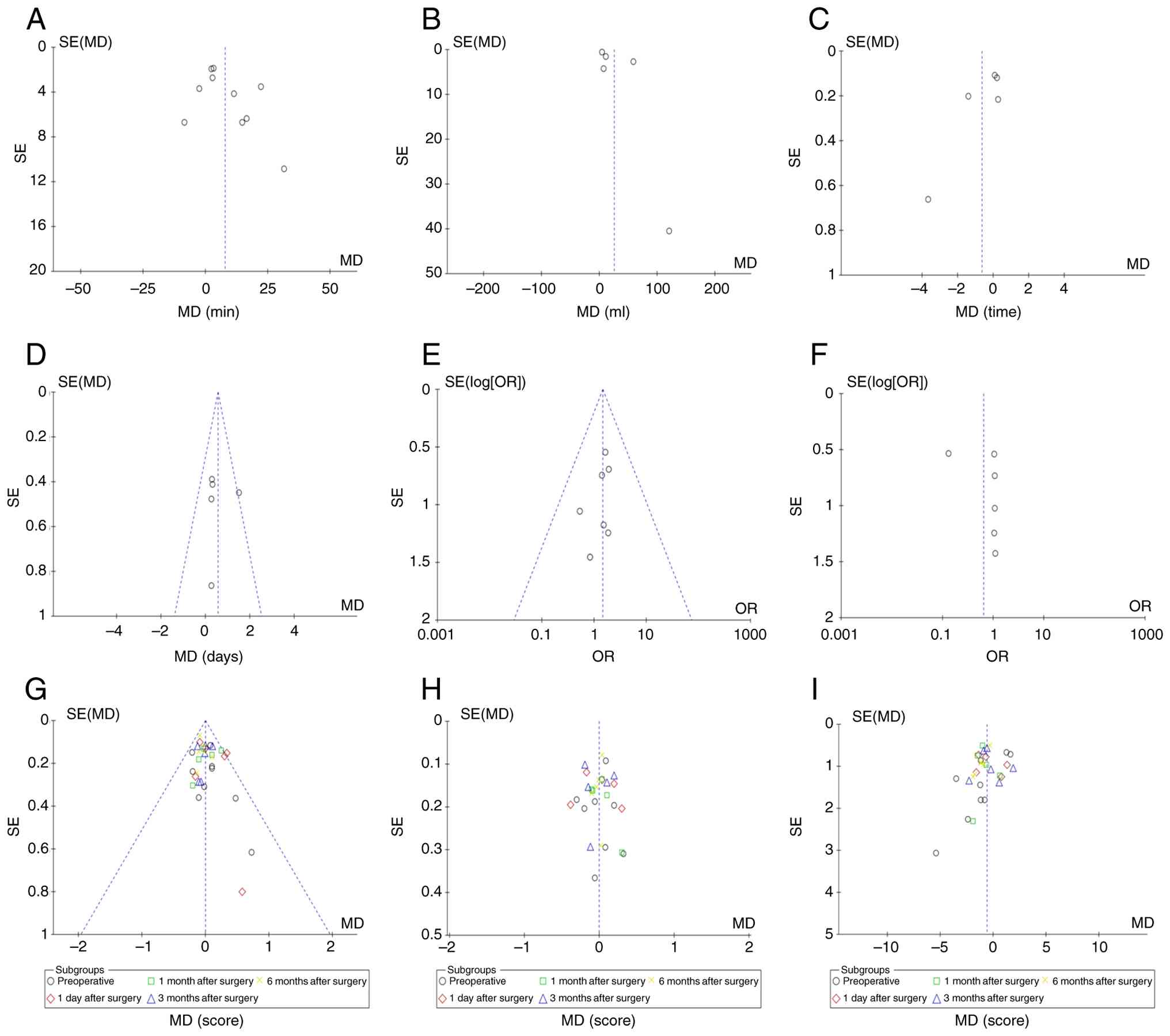

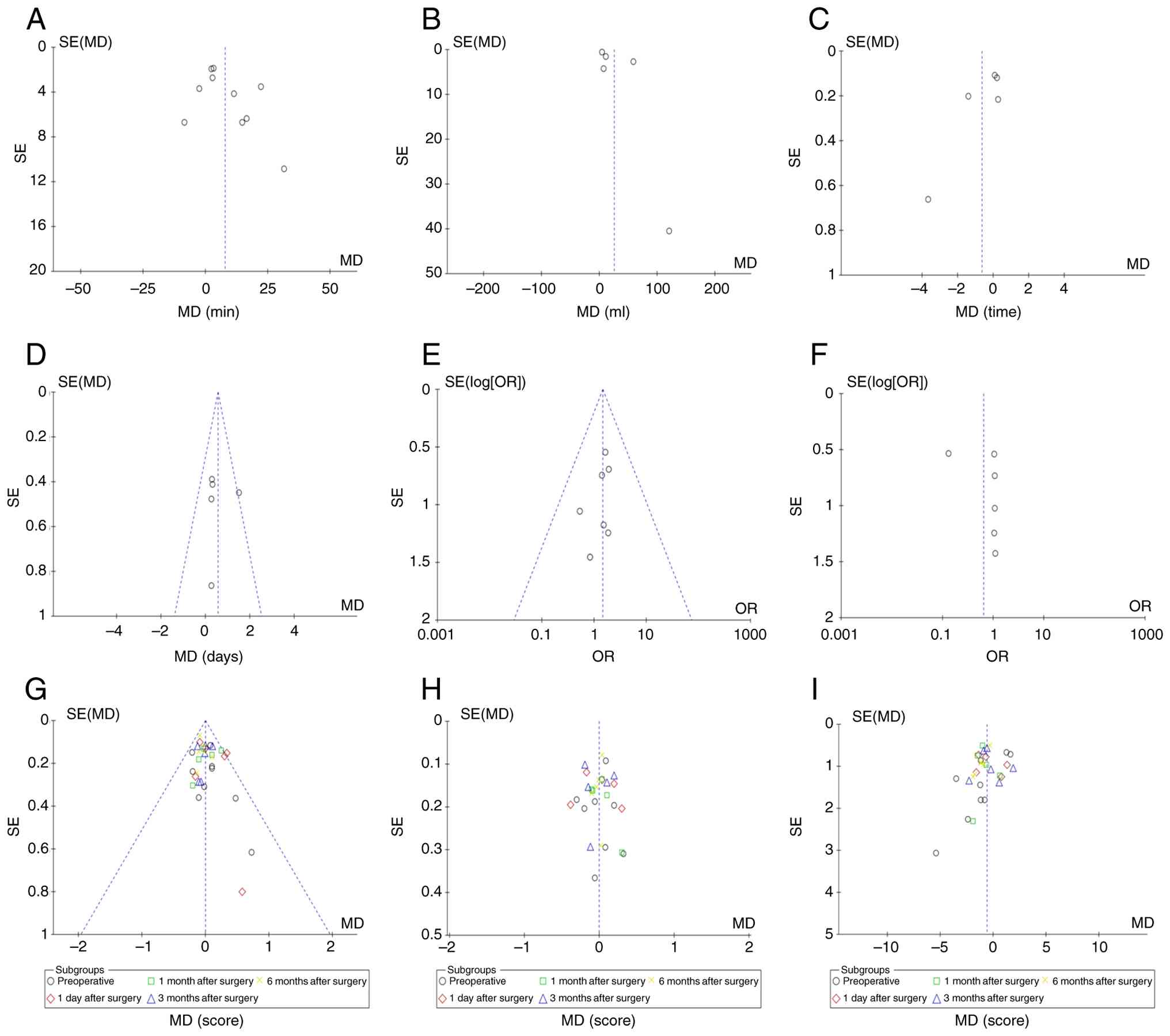

Publication bias. Publication bias evaluation

for the nine primary outcomes including surgical efficiency

(operative time, blood loss, hospital stay and fluoroscopy

frequency), functional outcomes (MacNab excellent/good rate, back

and leg VAS and ODI) and safety (complications), was assessed using

funnel plots in RevMan 5.4. Visual inspection combined with Egger's

test (P>0.05 threshold) confirmed symmetrical funnel plots

across all outcomes (Fig. 7),

indicating no significant publication bias.

| Figure 7Funnel plots assessing publication

bias across (A) operative time, (B) blood loss, (C) fluoroscopy

frequency, (D) hospital stay, (E) MacNab excellent/good rate, (F)

complications, (G) back VAS score, (H) leg VAS score and (I) ODI

score outcomes. SE, standard error; MD, mean difference; OR, odds

ratio; VAS, Visual Analog Scale; ODI, Oswestry Disability

Index. |

Sensitivity and subgroup analyses. Notable

heterogeneity (I2>50%) was identified for operative

time, blood loss and fluoroscopy frequency (Fig. 2). Sensitivity analyses, performed

by sequentially excluding each individual study, demonstrated that

the overall results and the substantial heterogeneity remained

largely unchanged (I² consistently >50%) (data not shown). This

indicates that the observed heterogeneity is robust and not driven

by any single outlier study. Instead, the sources of heterogeneity

are likely multifactorial, potentially stemming from variations in

surgical techniques, patient selection criteria, case complexity

and surgeon experience across the included studies.

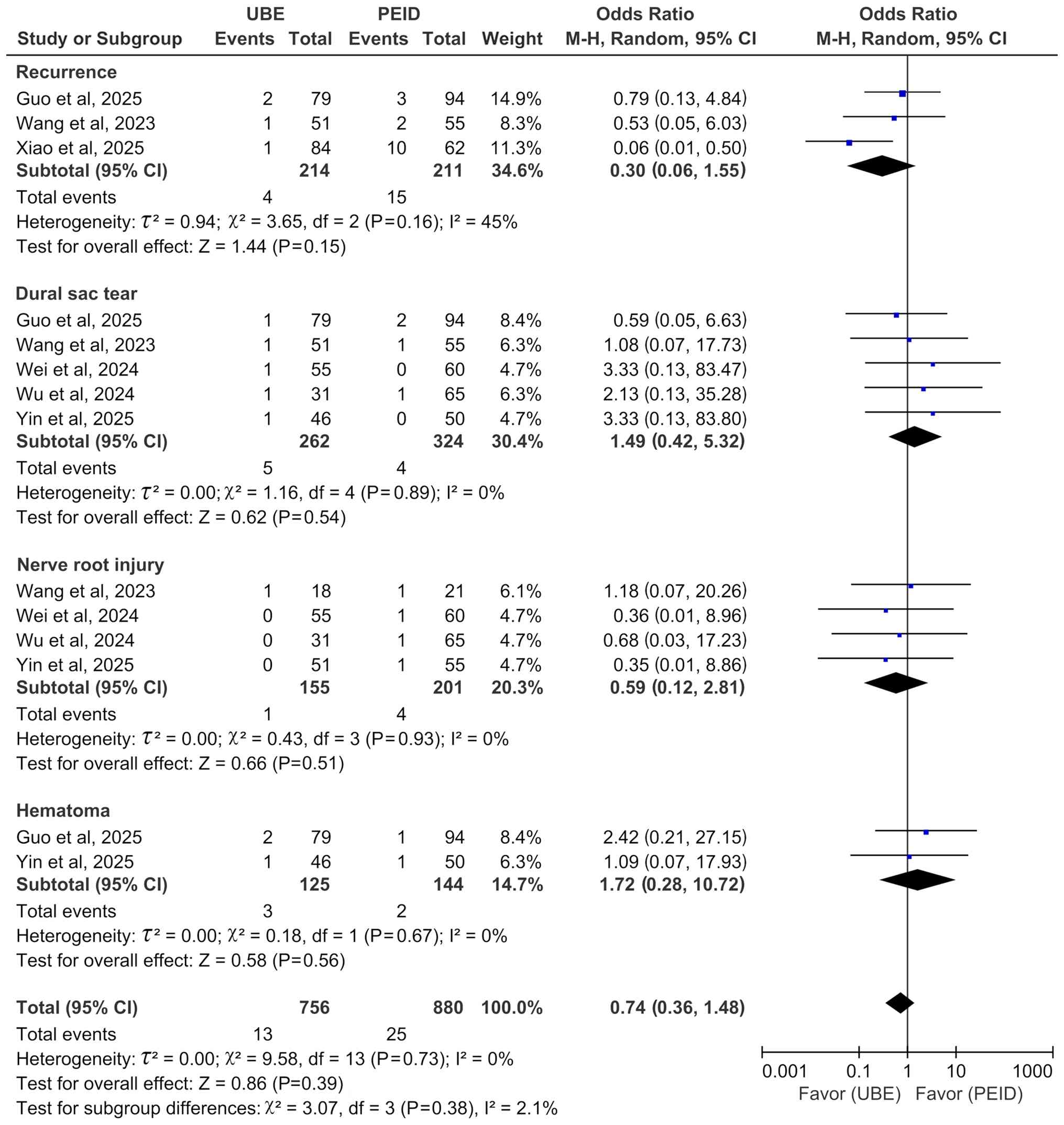

Subgroup analysis of complications was performed to

delineate the safety profiles of the two techniques beyond the

pooled overall rate. While the overall complication rates did not

differ significantly between UBE and PEID, the subgroup analysis

revealed distinct patterns. Notably, the recurrence subgroup

exhibited moderate heterogeneity (I²=45%), whereas heterogeneity

was negligible (I²=0%) in subgroups for dural tear, nerve root

injury and hematoma (Fig. 8).

For the recurrence outcome, subgroup analysis

revealed moderate heterogeneity (I²=45%). To investigate its

source, a sensitivity analysis was performed by sequentially

excluding each study. The exclusion of Xiao et al (18) eliminated the between-study

heterogeneity (I²=0%), identifying it as the primary source of

variance. This study (18)

reported an exceptionally high recurrence rate in the PEID group

(16.13%; 10/62) compared with that in the UBED group (1.19%; 1/84),

yielding an extreme effect size (OR, 0.06) that diverged markedly

from the other trials (Fig. 8).

This disparity was attributed to the technical and anatomical

limitations of the interlaminar PEID approach, particularly at the

L5-S1 level, such as a high iliac crest or a narrow interlaminar

space, which may restrict visual field and lead to incomplete

fragment removal. By contrast, the dual-portal design and wider

laminar exposure in UBED were described as enabling a broader

operative field and more complete decompression. Thus, the

sensitivity analysis confirms that the heterogeneity in recurrence

rates was largely driven by the distinct findings reported by Xiao

et al (18).

Discussion

Efficacy and safety of UBE and PEID in the treatment

of single-level LDH were compared using the interlaminar approach.

By focusing exclusively on this specific surgical corridor, the

present study offered a more precise comparison by minimizing

confounding variables associated with anatomical variations. The

main findings indicate a nuanced balance, whereby EID demonstrated

superior surgical efficiency, reflected by shorter operative time,

lower intraoperative blood loss and decreased hospital stay

durations. Conversely, UBE was associated with improved

intermediate-term functional recovery, evidenced by greater ODI

improvement at 1 and 6 months postoperatively. No significant

differences were found in pain relief (VAS score), MacNab

excellent/good rates or overall complication rates.

Observed advantages of PEID in operative time and

blood loss align with its minimally invasive, single-portal design,

which facilitates direct access and minimizes osseous disruption

(27). However, the notable

heterogeneity (I2>80%) in these outcomes warrants

cautious interpretation. Sensitivity analyses indicated that the

heterogeneity was not random but primarily driven by specific

studies (17-26),

suggesting both clinical and methodological variability. This

variability may be attributable to two primary factors: Case

selection bias, as the more versatile UBE technique may be

preferentially used for complex cases (such as those involving

migrated fragments or spinal stenosis) that inherently require

longer operative times and involve more vascularized tissue

(28) and variations in surgeon

experience and learning curves among the included studies. The

technically demanding spatial orientation required for PEID and the

steep learning curve associated with UBE both affect procedural

efficiency (19,29). Therefore, although PEID exhibits

higher efficiency in controlled analyses, the notable heterogeneity

indicates that real-world outcomes are influenced by

patient-specific characteristics and surgeon proficiency.

Consequently, the efficiency differences may partially reflect

variations in clinical application rather than inherent procedural

superiority.

Comparable VAS scores demonstrated that both

techniques are highly effective in relieving pain. The key finding,

however, is the sustained superiority of UBE in ODI improvement. As

the ODI represents a multifactorial index reflecting ability to

perform daily activities, this outcome suggests that UBE may

promote a more favorable quality of functional recovery. This

advantage may be attributed to the biportal configuration of the

UBE technique (30). The

separation of the endoscope from the surgical instruments provides

a panoramic, fluid-maintained visual field. Enhanced visualization,

together with the capacity for bimanual instrument triangulation,

enables meticulous dissection of herniated fragments and adhesions

and facilitates more comprehensive decompression of neural

structures, particularly in cases with concomitant pathological

changes such as ligamentum flavum hypertrophy or lateral recess

stenosis (31). Such complete

decompression may contribute to improved medium-term functional

restoration. By contrast, the single-channel design of PEID,

although minimally invasive, restricts instrument maneuverability

and limits the ability to adequately address coexisting pathology,

thereby increasing the likelihood of residual compression that may

hinder postoperative functional recovery (32,33).

Although the overall complication rates did not

differ significantly between UBE and PEID, the specific patterns of

complications and recurrence rates varied notably, reflecting their

technical characteristics.

The higher recurrence rate associated with PEID in

one study may be explained by anatomical and procedural factors

(18). At the L5-S1 level,

constraints such as a high iliac crest and a narrow interlaminar

window may restrict the working angle and motion range of the

single portal (34). These

limitations may impede the ability of the surgeon to adequately

access and remove migrated or sequestered disc fragments located

ventrally to the thecal sac or nerve root, thereby increasing the

likelihood of residual fragments and subsequent recurrence

(35). By contrast, the

configuration and broader operative field of the UBE dual-port

mitigate these constraints, enabling more extensive visualization

and thorough decompression (36).

Conversely, UBE exhibits a distinct risk profile,

primarily involving dural tears and epidural hematoma (37,38).

The use of multiple instruments, such as burrs and rongeurs, within

a confined space under continuous irrigation heightens the risk of

inadvertent dural injury (39,40).

Moreover, the greater degree of soft tissue dissection and bone

removal creates a larger potential dead space, predisposing

patients to postoperative epidural hematoma formation (41,42).

By contrast, the primary procedure-specific complications of PEID

include iatrogenic nerve root injury and dural tears, typically

occurring during working cannula insertion, instrument manipulation

or contact within the limited endoscopic field of view (43,44).

Selection between UBE and PEID should be

individualized based on a comprehensive evaluation of patient

anatomy, pathology and surgeon expertise (22,23).

PEID, utilizing a single-portal system, is optimally indicated for

contained central or paracentral disc herniations at the L5-S1

level (45). This approach

leverages the relatively larger anatomical interlaminar window at

this level, facilitating direct access with minimal tissue

disruption (46). Consequently,

PEID is typically associated with accelerated postoperative

recovery, making it a favorable option for patients seeking a rapid

return to daily activity (47).

By contrast, UBE, characterized by separate

endoscopic and instrumental channels, provides a panoramic field of

view and triangulated bimanual maneuverability (48). These technical advantages make it

suited for managing complex pathologies, including foraminal or

extraforaminal herniation, highly migrated disc fragments and cases

complicated by notable central or lateral recess stenosis (49). Furthermore, UBE is advantageous at

higher lumbar levels (L1-L4), where the narrower interlaminar space

poses a challenge for single-portal techniques (50). From a surgical ergonomics

perspective, the operational principles of UBE resemble those of

conventional microdiscectomy, which may flatten the learning curve

for surgeons transitioning from open procedures to endoscopic spine

surgery (30,36).

Within the present meta-analysis, several

limitations must be noted. i) All included studies were

retrospective cohorts, which inherently carry selection bias. The

notable variation in follow-up duration (range, 3-24 months)

limited long-term outcome evaluation. Inadequate reporting of disc

herniation subtypes (such as protrusion and extrusion) in the

primary studies precluded stratified subgroup analyses by pathology

severity. The relatively small number of studies/outcome metric

(4-10 studies) may have increased methodological heterogeneity.

Inclusion of only English language publications introduced

potential language bias and omission of parameters such as hidden

blood loss may have led to underestimation of total procedural

trauma. Consequently, these limitations may restrict the

generalizability of the findings to broader clinical settings.

Future validation should involve large-scale, multicenter,

prospective randomized controlled trials with standardized outcome

assessment protocols to demonstrate long-term efficacy and

safety.

In conclusion, the present meta-analysis

demonstrated that, for the treatment of single-level lumbar disc

herniation using the interlaminar approach, PEID is associated with

greater surgical efficiency, characterized by shorter operative

time, decreased intraoperative blood loss and shorter hospital

stay. Conversely, UBE provides improved intermediate-term

functional recovery, evidenced by markedly improved ODI scores at

1- and 6-month follow-ups. The notable heterogeneity in

efficiency-related outcomes highlights the influence of case

selection and surgeon proficiency. Therefore, the choice between

techniques should be individualized. PEID is most appropriate for

less complex cases in which rapid recovery is a clinical priority,

whereas UBE is preferable for complex scenarios requiring extensive

decompression. Ultimately, surgical decision-making should be

guided by the specific pathological features of the patient,

familiarity with the technique and the available institutional

resources.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported by the Hospital-level

Scientific Research Fund of Changzhi Key Laboratory of

Biomechanical Research and Application of Spinal Degenerative

Diseases (grant no. 2022-008). This study was also facilitated by

the research platform of the Changzhi Key Laboratory of

Biomechanical Research and Application of Spinal Degenerative

Diseases.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study are included

in the figures and/or tables of this article.

Authors' contributions

YG and FH conceived and designed the study. FH, JW

and SQ performed the literature search, data extraction and

meta-analysis. PH and YX conducted the statistical analysis and

interpreted the data. PH and YX drafted the manuscript. All authors

critically reviewed and revised the manuscript for important

intellectual content. All authors have read and approved the final

version of the manuscript. YG and FH confirm the authenticity of

all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Dieleman JL, Cao J, Chapin A, Chen C, Li

Z, Liu A, Horst C, Kaldjian A, Matyasz T, Scott KW, et al: US

Health Care Spending by Payer and Health Condition, 1996-2016.

JAMA. 323:863–884. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Benzakour T, Igoumenou V, Mavrogenis AF

and Benzakour A: Current concepts for lumbar disc herniation. Int

Orthop. 43:841–851. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Martin BI, Deyo RA, Mirza SK, Turner JA,

Comstock BA, Hollingworth W and Sullivan SD: Expenditures and

health status among adults with back and neck problems. JAMA.

299:656–664. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Kwon H and Park JY: The role and future of

endoscopic spine surgery: A narrative review. Neurospine. 20:43–55.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Penchev P, Ilyov IG, Todorov T, Petrov PP

and Traykov P: Comprehensive analysis of treatment approaches for

lumbar disc herniation: A systematic review. Cureus.

16(e67899)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Kambin P and Sampson S: Posterolateral

percutaneous suction-excision of herniated lumbar intervertebral

discs. Report of interim results. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 207:37–43.

1986.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Sakti YM, Khadafi RN, Tarsan AK, Putro AC,

Sakadewa GP, Susanto DB and Sukotjo KK: Transforaminal endoscopic

lumbar discectomy for L5-S1 disc herniation: A case series. Int J

Surg Case Rep. 83(105967)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Chen J, Jing X, Li C, Jiang Y, Cheng S and

Ma J: Percutaneous endoscopic lumbar discectomy for L5S1 lumbar

disc herniation using a transforaminal approach versus an

interlaminar approach: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World

Neurosurg. 116:412–420.e2. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Chen KT, Tseng C, Sun LW, Chang KS and

Chen CM: Technical considerations of interlaminar approach for

lumbar disc herniation. World Neurosurg. 145:612–620.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

He Y, Wang H, Yu Z, Yin J, Jiang Y and

Zhou D: Unilateral biportal endoscopic versus uniportal

full-endoscopic for lumbar degenerative disease: A meta-analysis. J

Orthop Sci. 29:49–58. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Burke SM, Safain MG, Kryzanski J and

Riesenburger RI: Nerve root anomalies: Implications for

transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion surgery and a review of the

Neidre and Macnab classification system. Neurosurg Focus.

35(E9)2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Price DD, McGrath PA, Rafii A and

Buckingham B: The validation of visual analogue scales as ratio

scale measures for chronic and experimental pain. Pain. 17:45–56.

1983.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Fairbank JC and Pynsent PB: The oswestry

disability index. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 25:2940–2952; discussion

2952. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron

I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan

SE, et al: The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for

reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 372(n71)2021.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Cook DA and Reed DA: Appraising the

quality of medical education research methods: The medical

education research study quality instrument and the

newcastle-ottawa scale-education. Acad Med. 90:1067–1076.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Nasser M: New Standards for Systematic

Reviews Incorporate Population Health Sciences. Am J Public Health.

110:753–754. 2020.

|

|

17

|

Wang D, Yang J, Liu C, Lin W, Chen Y, Lei

S, Cheng P, Huang Y, Gu S, Lin Y, et al: Comparative analysis of

endoscopic discectomy for demanding lumbar disc herniation. Sci

Rep. 15(9098)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Xiao L, Zhou J, Zhong Q, Zhang X and Cao

X: Clinical comparison of percutaneous endoscopic interlaminar vs.

unilateral biportal endoscopic discectomy for lumbar disc

herniation: A retrospective study. Sci Rep.

15(15347)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Guo W, Guo S, Zhang X, Zhang W, Xia G and

Liao B: Comparative study of the learning curves for percutaneous

endoscopic interlaminar lumbar discectomy and unilateral biportal

endoscopy techniques. BMC Surg. 25(210)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Yin J, Gao G, Chen S, Ma T and Nong L:

comparative study between unilateral biportal endoscopic discectomy

and percutaneous interlaminar endoscopic discectomy for the

treatment of L5/S1 disc herniation. World Neurosurg.

194(123526)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Qian J, Lv X, Luo Y, Liu Y and Jiang W:

Unilateral biportal endoscopic discectomy versus percutaneous

endoscopic lumbar discectomy in the treatment of lumbar disc

herniation linked with posterior ring apophysis separation: A

retrospective study. World Neurosurg. 193:957–963. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Yang YF, Yu JC, Zhu ZW, Li YW, Xiao Z, Zhi

CG, Xie Z, Kang YJ, Li J and Zhou B: Comparison of clinical

outcomes and cost-utility between unilateral biportal endoscopic

discectomy and percutaneous endoscopic interlaminar discectomy for

single-level lumbar disc herniation: A retrospective matched

controlled study. J Orthop Surg Res. 19(755)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Wei WB, Dang SJ, Liu HZ, Duan DP and Wei

L: Unilateral biportal endoscopic discectomy versus percutaneous

endoscopic interlaminar discectomy for lumbar disc herniation. J

Pain Res. 17:1737–1744. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Wu S, Zhong D, Zhao G, Liu Y and Wang Y:

Comparison of clinical outcomes between unilateral biportal

endoscopic discectomy and percutaneous endoscopic interlaminar

discectomy for migrated lumbar disc herniation at lower lumbar

spine: A retrospective controlled study. J Orthop Surg Res.

19(21)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Wang L, Li C, Han K, Chen Y, Qi L and Liu

X: Comparison of clinical outcomes and muscle invasiveness between

unilateral biportal endoscopic discectomy and percutaneous

endoscopic interlaminar discectomy for lumbar disc herniation at

L5/S1 Level. Orthop Surg. 15:695–703. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Zuo R, Jiang Y, Ma M, Yuan S, Li J, Liu C

and Zhang J: The clinical efficacy of biportal endoscopy is

comparable to that of uniportal endoscopy via the interlaminar

approach for the treatment of L5/S1 lumbar disc herniation. Front

Surg. 9(1014033)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Wu TL, Yuan JH, Jia JY, He DW, Miao XX,

Deng JJ and Cheng XG: Percutaneous endoscopic interlaminar

discectomy via laminoplasty technique for L5 -S1 lumbar disc

herniation with a narrow interlaminar window. Orthop Surg.

13:825–832. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Feng F, Li G, Meng H, Chen H, Li X and Fei

Q: Clinical efficacy of unilateral biportal endoscopic technique

for adjacent segment pathology following lumbar fusion. J Orthop

Surg Res. 20(628)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Demirtaş OK and Özer Mİ: Unilateral

biportal endoscopic discectomy for lumbar disc herniation: Learning

curve analysis with CUSUM analysis and clinical outcomes. Clin

Neurol Neurosurg. 249(108755)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Yu Z, Ye C, Alhendi MA and Zhang H:

Unilateral biportal endoscopy for the treatment of lumbar disc

herniation. J Vis Exp. 15:2023.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Kwon O, Yoo SJ and Park JY: Comparison of

unilateral biportal endoscopic discectomy with other surgical

technics: A systemic review of indications and outcomes of

unilateral biportal endoscopic discectomy from the current

literature. World Neurosurg. 168:349–358. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Fang N, Yan S and Yang A: Research

advances in unilateral endoscopic spinal surgery for the treatment

of lumbar disc herniation: A review. J Orthop Surg Res.

20(643)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Fukuhara D, Ono K, Kenji T and Majima T: A

narrative review of full-endoscopic lumbar discectomy using

interlaminar approach. World Neurosurg. 168:324–332.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Choi G, Lee SH, Raiturker PP, Lee S and

Chae YS: Percutaneous endoscopic interlaminar discectomy for

intracanalicular disc herniations at L5-S1 using a rigid working

channel endoscope. Neurosurgery. 58 (1 Suppl):ONS59–68; discussion

ONS59-68. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Kim HS and Park JY: Comparative assessment

of different percutaneous endoscopic interlaminar lumbar discectomy

(PEID) techniques. Pain Physician. 16:359–367. 2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Kim SK, Kang SS, Hong YH, Park SW and Lee

SC: Clinical comparison of unilateral biportal endoscopic technique

versus open microdiscectomy for single-level lumbar discectomy: A

multicenter, retrospective analysis. J Orthop Surg Res.

13(22)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Bai TY, Meng H, Lin JS, Fan ZH and Fei Q:

Application of intraoperative neurophysiological monitoring in

unilateral biportal endoscopic lumbar spine surgery. J Orthop Surg

Res. 20(334)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Lee SY, Shin DA, Yi S, Ha Y, Kim KN and

Lee CK: Overview and prevention of complications during biportal

endoscopic lumbar spine surgery. J Minim Invasive Spine Surg Tech.

8:145–152. 2023.

|

|

39

|

Deng C, Li X, Wu C, Xie W and Chen M:

One-hole split endoscopy versus unilateral biportal endoscopy for

lumbar degenerative disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis

of clinical outcomes and complications. J Orthop Surg Res.

20(187)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Matsukawa K, Fujiyoshi K, Kobayashi Y,

Kitagawa T and Yato Y: Delayed herniation of cauda equina root

through occult dural tear following unilateral biportal endoscopic

decompression: Illustrative case. J Neurosurg Case Lessons.

10(CASE25438)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Lou X, Chen P, Shen J, Chen J, Ge Y and Ji

W: Why does such a cyst appear after unilateral biportal endoscopy

surgery: A case report and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore).

102(e36665)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Xu J, Wang D, Liu J, Zhu C, Bao J, Gao W,

Zhang W and Pan H: Learning curve and complications of unilateral

biportal endoscopy: Cumulative sum and risk-adjusted cumulative sum

analysis. Neurospine. 19:792–804. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Zhou C, Zhang G, Panchal RR, Ren X, Xiang

H, Xuexiao M, Chen X, Tongtong G, Hong W and Dixson AD: Unique

complications of percutaneous endoscopic lumbar discectomy and

percutaneous endoscopic interlaminar discectomy. Pain physician.

21:E105–E112. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Xie TH, Zeng JC, Li ZH, Wang L, Nie HF,

Jiang HS, Song YM and Kong QQ: Complications of lumbar disc

herniation following full-endoscopic interlaminar lumbar

discectomy: A large, single-center, retrospective study. Pain

Physician. 20:E379–E387. 2017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Pan M, Li Q, Li S, Mao H, Meng B, Zhou F

and Yang H: percutaneous endoscopic lumbar discectomy: Indications

and complications. Pain Physician. 23:49–56. 2020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Li T, Yang G, Zhong W, Liu J, Ding Z and

Ding Y: Percutaneous endoscopic transforaminal vs. interlaminar

discectomy for L5-S1 lumbar disc herniation: A retrospective

propensity score matching study. J Orthop Surg Res.

19(64)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Liu W, Liu L, Pan Z and Gu E: Percutaneous

endoscopic interlaminar discectomy with patients' participation :

Better postoperative rehabilitation and satisfaction. J Orthop Surg

Res. 19(547)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Liu L, Zhang X and Kang N: Application

status and considerations of unilateral biportal endoscopy

technique. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi. 38:1510–1516.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar : (In Chinese).

|

|

49

|

Reis JPG, Pinto EM, Teixeira A, Frada R,

Rodrigues D, Cunha R and Miranda A: Unilateral biportal endoscopy:

Review and detailed surgical approach to extraforaminal approach.

EFORT Open Rev. 10:151–155. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Shao R, Du W, Zhang W, Cheng W, Zhu C,

Liang J, Yue J and Pan H: Unilateral biportal endoscopy via two

different approaches for upper lumbar disc herniation: A technical

note. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 25(367)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|