Introduction

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is a

life-threatening pulmonary disorder characterized by uncontrolled

inflammatory responses, diffuse alveolar damage and increased

pulmonary vascular permeability, leading to severe impairment of

gas exchange and potentially fatal respiratory failure (1). Despite significant advances in

supportive care, primarily involving lung-protective ventilation

strategies and refined fluid management, the mortality rate of ARDS

remains unacceptably high, ranging from 35 to 46% (2). The current therapeutic landscape

lacks effective pharmacological agents that directly target these

underlying pathological mechanisms, highlighting a critical unmet

need for novel therapeutic interventions (3).

In recent years, natural products derived from

medicinal plants have garnered significant attention as promising

sources for drug discovery due to their multi-target activities and

favorable safety profiles (4).

Carnosic acid (CA), a phenolic diterpene abundantly found in

rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis Linnaeus) and sage, has

been extensively documented for its potent anti-inflammatory,

antioxidant and antimicrobial properties (5). Previous studies have demonstrated

that CA can activate the nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor

2 (Nrf2) pathway, a master regulator of cellular antioxidant

responses. Upon activation, Nrf2 translocates to the nucleus and

induces the expression of a battery of cytoprotective genes,

including heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), which collectively counteract

oxidative stress (6,7). Furthermore, evidence suggests that

Nrf2 activation can indirectly suppress the NLR family pyrin domain

containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome, a key component of innate

immunity whose hyperactivation drives pyroptosis, a highly

inflammatory form of programmed cell death, through

caspase-1-mediated cleavage of gasdermin D (GSDMD) and subsequent

release of IL-1β and IL-18 (8,9).

This Nrf2-NLRP3 axis has been implicated in various inflammatory

diseases but remains relatively unexplored in the context of

ARDS.

Given the central roles of oxidative stress and

NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated pyroptosis in the pathogenesis of ARDS

(10,11), we hypothesize that CA may confer

protective effects against this syndrome. However, a systematic

investigation into the therapeutic potential and precise molecular

mechanisms of CA in ARDS, particularly its potential to

simultaneously modulate the Nrf2 pathway and NLRP3-mediated

pyroptosis, is still lacking.

Therefore, the present study employed an integrative

approach combining network pharmacology prediction, molecular

docking, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations and experimental

verification to elucidate the protective mechanisms and therapeutic

benefits of CA against ARDS. The study aims to provide a solid

foundation for the further development of CA as a potential

therapeutic agent for ARDS.

Materials and methods

Network pharmacology analysis. Data

preparation

Potential targets for CA were predicted using the

SwissTargetPrediction database (http://www.swisstargetprediction.ch). ARDS-related

targets were identified using public databases, including the

GeneCards database (https://www.genecards.org/) and the DisGeNET database

(version 7.0; http://www.disgenet.org/). To identify relevant

targets, the search terms ‘ARDS’, ‘acute lung injury’, ‘acute

respiratory distress syndrome’, ‘adult respiratory distress

syndrome’ and ‘acute lung injury’ were used. In the GeneCards

database, target selection was carried out using the following

criteria: i) Ranking targets by their relevance score; ii)

retaining only those with a score >2 times the median value and

iii) identifying and presenting the common targets between CA and

ARDS using a Venn diagram.

Functional enrichment analysis. Metascape

(http://www.metascape.org) is an online tool for

functional annotation. This platform facilitates gene function

annotation analysis, empowering users to leverage contemporary,

prevalent bioinformatics methodologies in the examination of gene

and protein batches. By doing so, it enables the elucidation of

gene and protein functionalities (12). The tool was used to carry out a

functional enrichment analysis of the intersected target genes

using Gene Ontology (GO) (13) and

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analyses

(14). The GO analysis encompassed

three categories: i) Biological processes (BP); ii) molecular

functions (MF); and iii) cellular components (CC). The top 10 most

significantly enriched terms in both GO-BP and KEGG pathway

analyses were then visualized using the SRplot bioinformatics

platform (http://www.bioinformatics.com.cn/; last accessed on

April 1, 2025). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Protein-protein interaction (PPI) network

construction. Overlapping targets were analyzed using Search

Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins (STRING;

https://cn.string-db.org/; version 11.0) to

construct a PPI network. This network was constructed with a

specific focus on Homo sapiens and a high confidence score

of 0.950 to ensure the reliability of interactions. Following this,

the PPI network was visually rendered using Cytoscape software

(version 3.7.2) (15),

facilitating a comprehensive visualization and analysis of the

intricate protein interactions.

Molecular docking. Molecular docking has

emerged as a fundamental technique in modern drug discovery,

allowing researchers to predict binding affinities and molecular

interactions by analyzing the three-dimensional conformations of

protein-ligand complexes. In the present study, molecular docking

simulations were carried out between CA and its key target proteins

identified through the aforementioned analysis. The

three-dimensional structures of CA and the pivotal proteins were

sourced from PubChem (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and the Research

Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics Protein Data Bank

database (http://www.rcsb.org/). All docking

procedures were executed using AutoDock Tools (version 1.5.6;

https://autodock.scripps.edu/), with

validation steps incorporated to verify the reliability of the

computational predictions. Analysis of molecular docking utilized

binding energy to assess protein-ligand interactions, with values

≤-5 kcal/mol indicating strong binding affinity (16). To assess structural alignment, root

mean square deviation (RMSD) calculations were employed. The RMSD

lower bound (RMSD l.b.) and the RMSD upper bound (RMSD u.b.) allow

the diversity of conformations in the molecular docking results,

and the deviation range from the target conformation to be

understood. This is useful for evaluating the reliability and

accuracy of the docking results. Generally, the smaller the RMSD

l.b., the more similar the conformation obtained from the docking

is to the target conformation, and the more reliable the docking

result is. Conversely, the RMSD u.b. can assist in determining

whether the docking algorithm is capable of searching a

sufficiently wide enough conformational space. To facilitate a

deeper understanding of the docking results, the molecular docking

patterns were visually represented using PyMOL software (version

2.4; https://www.pymol.com/pymol.html),

allowing for a detailed examination of the interactions at a

molecular level.

MD. Groningen Machine for Chemical

Simulations (GROMACS; version 2022.4; http://www.gromacs.org) was used to carry out MD

simulations, which were all executed under isothermal-isobaric

ensemble conditions simulating a system with a constant number of

particles, temperature and pressure (NPT) with periodic boundary

constraints. The linear constraint solver algorithm constrained

hydrogen bonds with a 2 fsec integration time step. Electrostatic

energy (ELE) interactions were calculated using the particle-mesh

Ewald method, with a 1.2-nm cutoff (17), while van der Waals (VDW)

interactions employed a 10 Å cutoff distance, updated every 10

steps. Temperature (298 K) and pressure (1 bar) were maintained

using the V-rescale thermostat and Berendsen barostat algorithms,

respectively (18). The system

underwent sequential equilibration under the protocol of 100 ps

(constant number of particles, volume and temperature) followed by

100 ps NPT, before a 100 ns production run, with trajectories saved

every 10 ps. Post-simulation analyses included trajectory

visualization using Visual Molecular Dynamics (https://www.ks.uiuc.edu/Research/vmd/)

and PyMOL, along with binding free energy calculations using the

GROMACS package ‘g_mmpbsa’ (19).

Key evaluation metrics comprised: i) System stability parameters

(RMSD of complex protein and ligand; radius of gyration of complex;

root mean square fluctuation of protein residues); ii) interaction

characteristics (binding site distance, buried solvent-accessible

surface area, VDW/ELE energies, hydrogen bond dynamics and

per-residue energy contributions); and iii) structural features

(conformational superposition and interaction fingerprints). This

comprehensive analysis protocol ensured rigorous assessment of the

protein-ligand complex dynamics.

Experimental design. Reagents and

antibodies

Most of the reagents and antibodies used in the

present study are shown in Table

I.

| Table IReagents and antibodies. |

Table I

Reagents and antibodies.

| Name | Catalogue

number | Manufacturer |

|---|

| CA | B21175 | Shanghai Yuanye

Biotechnology Co., Ltd. |

| LPS (0111:B4) | L4391 | Sigma Aldrich;

Merck KGaA |

| ML385 | HY-100523 | MEDCHEMEXPRESS

LLC |

| DMEM | 12100 | Beijing Solarbio

Science & Technology Co., Ltd. |

| RIPA Buffer | R0010 | Beijing Solarbio

Science & Technology Co., Ltd. |

| ATP | A9310 | Beijing Solarbio

Science & Technology Co., Ltd. |

| NLRP3 antibody | 15101 | Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc. |

| ASC antibody | 67824 | Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc. |

| CASP1 antibody | 24232 | Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc. |

| GSDMD antibody | 39754 | Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc. |

| Nrf2 antibody | 12721 | Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc. |

| HO-1 antibody | 43966 | Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc. |

| GAPDH antibody | 2118 | Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc. |

| Secondary

antibody | 7074 | Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc. |

| Fluorescent

secondary antibody | 8889 | Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc. |

| IL-1β ELISA | E-EL-R0012c | Wuhan Elabscience

Biotechnology Co., Ltd. |

| IL-18 ELISA | SEA064Ra | Wuhan Elabscience

Biotechnology Co., Ltd. |

| MDA assay kit | A003-1-2 | Nanjing Jiancheng

Bioengineering Institute |

| MPO assay kit | A044-1-1 | Nanjing Jiancheng

Bioengineering Institute |

| SOD assay kit | A001-3-2 | Nanjing Jiancheng

Bioengineering Institute |

| LDH assay kit | C0016 | Beyotime

Biotechnology |

| Annexin

V-FITC/PI | APOAF | Sigma Aldrich;

Merck KGaA |

| DCFH-DA | S0033 | Beyotime

Biotechnology |

| Goat serum | C0265 | Beyotime

Biotechnology |

| BCA | PC0020 | Beijing Solarbio

Science & Technology Co., Ltd. |

| CCK-8 | C0037 | Beyotime

Biotechnology |

| RT-qPCR kit | D7268S | Beyotime

Biotechnology |

Animals and treatments. Male BALB/c mice

(n=48; age, 8 weeks; weight, 21-25 g), were obtained from the Model

Animal Research Center of Nanjing University. Mice were housed in a

standard laboratory environment maintained at a temperature range

of 20-26˚C, with a relative humidity of 40-70% and a 12-h

light/dark cycle. The mice were allowed to feed and drink ad

libitum throughout the present study. All animal experiments

were approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Medical

School of Nanjing University Affiliated Jinling Hospital (Nanjing,

China; approval no. 2022DZGKJDWLS-00161) and complied with the

Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (https://olaw.nih.gov/policies-laws/guide-care-use-lab-animals).

The ARDS model was established through

intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of lipopolysaccharide (LPS; 10

mg/kg), a well-established method documented in previous studies

(20,21). Mice were randomly allocated into

the following four experimental groups (n=6/group): i) Control

group (PBS; i.p.); ii) LPS group (10 mg/kg; i.p.); iii) CA group

(40 mg/kg; i.p.); and iv) ML385 group (40 mg/kg CA + 30 mg/kg

ML385; i.p.). All animals were anesthetized with 1% sodium

pentobarbital (40 mg/kg; i.p.) before administration. A total of 30

min post-LPS injection, treatment groups received either CA

(dissolved in 0.5% DMSO) or the combination of ML385 [nuclear

factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) inhibitor; dissolved in

0.5% DMSO; 30 mg/kg, i.p.] (22)

followed by CA, while controls received equivalent volumes of PBS.

Survival rates were recorded every 24 h for a 7-day observation

period following the LPS challenge. Animal deaths were checked for

twice daily (morning and evening) using a combination of criteria:

i) The absence of spontaneous movement for >5 min of

observation; ii) the lack of a response to gentle tactile stimuli

(e.g., a soft touch with a clean gloved finger); and iii) the

absence of visible respiration and signs of a heartbeat. For mice

reaching the predefined moribund state (severe lethargy, inability

to rise, dyspnea, etc.), euthanasia was performed promptly with an

overdose of sodium pentobarbital (100 mg/kg, i.p.), and the time of

euthanasia was recorded as the time of death for survival analysis.

Upon confirmation of death, a necropsy was immediately performed.

The thoracic cavity was exposed, and the lung tissues were

carefully excised en bloc. Subsequently, the lungs were perfused

via the trachea with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to

clear residual blood. After blotting the surface liquid with filter

paper, the tissues were processed according to downstream

experimental needs: The left lung lobe was fixed in 4%

paraformaldehyde at 4˚C for 24 h for histological analysis, while

the right lung lobe was snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and then

transferred to a -80˚C freezer for storage, and reserved for

subsequent protein or RNA extraction. All tissue samples were

maintained at -80˚C until use.

Following euthanasia, 0.6-0.8 ml left ventricular

blood was immediately collected for blood gas analysis testing of

arterial oxygen partial pressure (PaO2) levels and

arterial carbon dioxide partial pressure (PaCO2),

FiO2 was measured during sampling using an oxygen

monitor. The PaO2/FiO2 ratio was then

calculated as PaO2 (mmHg) divided by FiO2.

Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) was obtained by carrying out

three cycles of instillation and withdrawal with 1-ml sterile PBS

through a tracheal cannula. The BALF samples were centrifuged at

1,500 x g for 15 min at 4˚C and the resulting supernatant was

aliquoted and stored at -80˚C for subsequent cytokine analysis. For

histological examination, the left lung lobes were perfused with

PBS and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4˚C for 24 h before

paraffin embedding. Tissue sections (4-µm thick) were prepared and

stained with H&E using standard protocols (hematoxylin: 0.1%,

5-8 min, room temperature; eosin: 0.5%, 1-3 min, room temperature).

Lung pathology was examined under a light microscope (Olympus BX53)

by an observer blinded to the groupings. Lung injury scores were

graded using the following scale: 0, no injury; 2, mild injury (up

to 25% injury of the field of view); 4, moderate injury (up to 50%

injury of the field of view); 6, severe injury (up to 75% injury of

the field of view); and 8, extremely severe injury (diffused

injury) (10). The upper right

lung lobes were excised and weighed to determine the wet/dry (W/D)

ratio by comparing fresh weight to weight after 72 h of desiccation

at 60˚C. Remaining lung tissues were quickly frozen in liquid

nitrogen and maintained at -80˚C for future protein

semi-quantification through ELISA and western blotting. This

comprehensive sample collection and processing protocol enabled

systematic evaluation of physiological parameters,

histopathological changes, and molecular markers through techniques

including ELISA, western blotting, RT-qPCR, and immunohistochemical

(IHC) analysis using commercial assay kits, thereby providing a

multi-faceted assessment of the ARDS model.

In the survival study (n=9 per group), mice received

the following treatments: The ARDS model was induced by a single

i.p. injection of LPS (10 mg/kg). After 30 min, the CA group

received CA (40 mg/kg, i.p.), while the CA + ML385 group received

ML385 (30 mg/kg, i.p.) followed by CA (40 mg/kg, i.p.), as

previously described (23).

Survival rates were recorded every 24 h for a 7-day observation

period following LPS challenge and euthanized at the moribund

stage. The humane endpoints were defined as the occurrence of

moribund animal characteristics in the mice, such as severe or

persistent lethargy, inability to rise from a recumbent position,

convulsions, tetraplegia and dyspnea (24,25).

Mortality was assessed through twice-daily monitoring (morning and

evening) to ensure accurate determination of survival time

points.

Cell culture. MH-S cells (murine alveolar

macrophage cells) were obtained from The Cell Bank of Type Culture

Collection of The Chinese Academy of Sciences. Cells were

maintained in a culture medium consisting of DMEM, supplemented

with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin and streptomycin. The cells were

incubated at 37˚C in an environment containing 5% CO2.

Following the respective treatments, cell culture supernatants were

collected for subsequent analysis by centrifugation of the culture

medium at 1,000 x g for 5 min at 4˚C to remove cellular debris.

For in vitro investigations, MH-S cells were

systematically allocated into the following four groups: i) Control

group; ii) LPS/ATP group; iii) CA-10 group; and iv) CA-20 group.

MH-S cells in the LPS/ATP, CA-10 and CA-20 groups were initially

exposed to LPS (1 µg/ml) for 4 h at 37˚C, followed by ATP

stimulation (5 mM) for 30 min at 37˚C (26). Subsequently, the CA-10 and CA-20

groups received either 10 or 20 µM CA and were further incubated

for 48 h at 37˚C, whereas the control groups received equivalent

volumes of culture medium.

Cell viability assay. A Cell Counting Kit-8

(CCK-8) assay was used to assess cell viability according to the

instructions of the manufacturer. MH-S cells were plated in 96-well

plates at a concentration of 5x103 cells/well and left

to adhere for 24 h under standard culture conditions. The cells

were then exposed to CA (0, 0.1, 1, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30 and 35 µM)

for 48 h at 37˚C. After treatment, each well received 10 µl CCK-8

solution (5 mg/ml) and the plates were incubated for 1 h at 37˚C in

an environment with 5% CO2. Absorbance was read at 450

nm with the model 680 microplate reader (Bio-Rad Laboratories,

Inc.).

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

analysis. In accordance with a previous study (23), total RNA was extracted from lung

tissues and cultured cells using TRIzol® reagent

(Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), strictly adhering to

the guidelines of the manufacturer. Subsequently, cDNA synthesis

was performed using the RT Kit (Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd.) according

to the manufacturer's protocol. The qPCR amplification was then

conducted on the SmartCycler® II system (Cepheid) using the

following thermocycling conditions: Initial denaturation at 95˚C

for 30 sec, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95˚C for 10

sec and annealing/extension at 60˚C for 30 sec. A melting curve

analysis was performed immediately after amplification to verify

the specificity of the PCR products. GAPDH as the endogenous

control. Relative gene expression levels were calculated using the

2-ΔΔCq method (27).

The specificity of the PCR amplification was confirmed by a single

peak in the melting curve analysis. The primer sequences used are

listed in Table II.

| Table IIPrimer sequences. |

Table II

Primer sequences.

| Gene | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|

| NLRP3 |

5'-GCTGCGATCAACAGGCGAGAC-3' |

5'-AAGGCTGTCCTCCTGGCATACC-3' |

| ASC |

5'-AACCCAAGCAAGATGCGGAAG-3' |

5'-TTAGGGCCTGGAGGAGCAAG-3' |

| CASP1 |

5'-ACAACCACTCGTACACGTCTTGC-3' |

5'-CCAGATCCTCCAGCAGCAACTTC-3' |

| GSDMD |

5'-ACTGAGGTCCACAGCCAAGAGG-3' |

5'-GCCACTCGGAATGCCAGGATG-3' |

| Nrf2 |

5'-TCTCCTCGCTGGAAAAAGAA-3' |

5'-AATGTGCTGGCTGTGCTTTA-3' |

| HO-1 |

5'-CAAGCCGAGAATGCTGAGTTCATG-3' |

5'-GCAAGGGATGATTTCCTGCCAG-3' |

| GAPDH |

5'-GCACCGTCAAGGCTGAGAAC-3' |

5'-TGGTGAAGACGCCAGTGGA-3' |

Western blotting. Protein lysates were

prepared from both treated MH-S cells and mouse lung tissues using

RIPA buffer supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors.

Protein concentrations were evaluated through the BCA assay kit,

according to the manufacturer's protocol. Prior to electrophoresis,

protein samples were mixed with 5X Laemmli sample buffer containing

5% β-mercaptoethanol (or 100 mM DTT) as a reducing agent and

denatured by boiling at 95-100˚C for 5-10 min. For western

blotting, protein lysates were adjusted to a concentration of 0.75

µg/µl for lung tissues or 1.0 µg/µl for MH-S cells using RIPA

buffer. A total of 15 µg protein/lane was loaded for all samples,

corresponding to 20 µl for lung tissues and 15 µl for cell lysates.

Proteins were then separated by SDS-PAGE on 8-12% gels (depending

on target protein size) under reducing conditions. The resolved

proteins were then electrophoretically transferred onto PVDF

membranes (0.45-µm pore size; MilliporeSigma) using a semi-dry

transfer system.

Each target protein and its loading control, GAPDH,

were ultimately detected on the same physical membrane to ensure

direct comparability. This was achieved through sequential

detection (stripping and re-probing) on a single membrane: For

analysis of the inflammasome pathway, the membrane was first probed

for NLRP3, ASC, and caspase-1 (p20). After imaging, the antibodies

were stripped, and the same membrane was then re-probed for GAPDH.

For analysis of GSDMD cleavage, the membrane was first probed for

GSDMD-FL and GSDMD-N. After imaging, the antibodies were stripped,

and the same membrane was then re-probed for GAPDH. Electrophoresis

conditions were optimized to ensure sufficient separation between

the GAPDH (~36 kDa) and GSDMD-N (30-35 kDa) bands prior to

stripping and re-probing, allowing for accurate post hoc alignment

and densitometric analysis.

Following transfer, all membranes were stained with

Ponceau S to confirm uniform protein loading and transfer

efficiency. The membranes were then blocked with 5% skimmed milk in

Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween-20 (TBST) at 4˚C

overnight (or for 1 h at room temperature if applicable). After

washing three times with TBST (10 min each), the membranes were

incubated with corresponding HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies

diluted in 5% skimmed milk/TBST for 1 h at room temperature.

Immunoreactive bands were detected using the Enhanced ECL Kit (cat.

no. P0018; Beyotime Biotechnology) according to the manufacturer's

instructions, and visualized using a Tanon-5200 Imaging System

(Tanon Science & Technology Co., Ltd.). Between probing cycles,

the membranes were stripped using a mild stripping buffer. Complete

removal of previous antibodies was verified by incubating the

membrane with ECL substrate and confirming the absence of signal

prior to the next round of antibody incubation. Densitometric

analysis of the bands was performed using ImageJ software (V1.37;

National Institutes of Health). The signal intensity of each target

protein was normalized to that of GAPDH obtained from the same

membrane lane.

Immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis. Firstly,

lung tissue samples were preserved in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4˚C

for 1 day, processed through a graded ethanol series and embedded

in paraffin blocks. Serial sections (5 µm) were then cut using the

RM2235 rotary microtome (Leica Biosystems). The staining procedure

involved: i) Deparaffinization in xylene (three changes, 5 min

each); ii) rehydration through a graded ethanol series (100-70%);

iii) antigen retrieval in citrate buffer (pH 6.0) at 95˚C for 20

min; iv) endogenous peroxidase blocking with 3%

H2O2 for 10 min at room temperature; and v)

non-specific site blocking with 5% goat serum for 30 min at room

temperature.

Sections were incubated with a primary antibody

against gasdermin D (GSDMD; 1:1,000) overnight at 4˚C in a

humidified environment. After three washes with PBS (5 min each),

the sections were exposed to an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody

(1:200) for 20 min at room temperature, followed by

3,3'-diaminobenzidine chromogen development (6 min) with

microscopic monitoring. Counterstaining was performed with

hematoxylin at room temperature for 30 sec, followed by dehydration

through graded ethanol and xylene clearing. Slides were examined

under the LSM700 confocal microscope (Zeiss GmbH).

Semi-quantitative analysis of IHC staining was performed using

ImageJ software.

For the co-detection of GSDMD-FL and GSDMD-N, the

same membrane was used. Due to the close molecular weights of

GSDMD-N and GAPDH, which could lead to overlapping bands and

imprecise semi-quantification, GAPDH was probed on a separate

membrane. Similarly, other target proteins (NLRP3, caspase-1 and

ASC) were detected on dedicated membranes to optimize antibody

conditions and avoid excessive stripping/re-probing cycles. To

ensure perfect comparability between different membranes, total

protein lysates for all samples were run on two identical SDS-PAGE

gels in parallel under the same electrophoretic conditions.

Proteins were then transferred in parallel onto separate PVDF

membranes under identical transfer conditions. To control for

loading and transfer variations, the membranes were stained with

Ponceau S (Sigma-Aldrich) after transfer. Densitometric analysis of

the total protein stain (Ponceau S) for each lane was performed

using ImageJ software, and the signal intensity of each target

protein was normalized to the total protein signal of its

corresponding lane.

Immunofluorescence analysis. Cells were

rinsed with PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at room

temperature and then washed three times with TBST (5 min each).

Permeabilization with 0.1% Triton X for 20 min at room temperature

was carried out after another three TBST washes (5 min each).

Primary antibodies of Nrf2 (as aforementioned) diluted in blocking

buffer were then applied and incubated overnight at 4˚C in a

humidified chamber. Subsequently, the cells were washed, incubated

with secondary antibody for 1 h in the dark at room temperature and

rinsed three times with TBST. Each sample received 200 µl antifade

mounting medium with DAPI and visualization was performed using the

LSM700 confocal microscope. Semi-quantitative analysis of IF

staining was performed using ImageJ software.

ELISA. Concentrations of IL-1β and IL-18 in

MH-S cell culture supernatants and BALF were quantified using ELISA

kits following the manufacturer's protocols. Standards and samples

(100 µl/well) were loaded in duplicate onto 96-well plates and

incubated at 37˚C for 90 min. After washing, 100 µl biotinylated

detection antibody was added to each well and incubated for 60 min

at 37˚C. After three washes, 100 µl HRP-conjugated streptavidin was

added and incubated for 30 min at 37˚C in the dark. The enzymatic

reaction was terminated by adding 50 µl stop solution and the

absorbance was immediately measured at 450 nm (with 570 nm

correction) using the Bio-Rad Model 680 microplate reader (Bio-Rad

Laboratories, Inc.). Cytokine concentrations were interpolated from

a four-parameter logistic standard curve generated with reference

standards.

Annexin V-FITC staining. MH-S cells were

cultured in a 24-well plate. After treatment, the plates were

centrifuged at 1,000 x g for 5 min at room temperature, the

supernatant was removed and the cells were washed twice with PBS.

Subsequently, the cells were stained with 250 µl Annexin V-FITC/PI

solution for 15 min at room temperature in the dark. Images were

then acquired using an IX73 inverted fluorescence microscope

(Olympus Corporation).

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release assay.

Cytotoxicity was assessed by quantifying LDH activity in cell

culture supernatants and BALF using a commercial LDH detection kit

assay, following the product description. A total of 100 µl

cell-free supernatant from each sample was transferred to a 96-well

plate and incubated with the reaction mixture for 30 min at room

temperature in the dark. The enzymatic reaction was terminated by

adding stop solution and absorbance was immediately measured at 450

nm using the model 680 microplate reader (Bio-Rad Laboratories,

Inc.).

Assessment of intracellular reactive oxygen

species (ROS) levels. Intracellular ROS levels were quantified

using 2',7'-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) as a

fluorescent probe. Cells were seeded in 24-well plates

(5x104 cells/well) and treated as indicated for 48 h at

37˚C. Subsequently, the cells were incubated with 10 µM DCFH-DA in

serum-free medium at 37˚C for 20 min in the dark. After three

washes with warm DMEM to remove excess probe, ROS detection was

carried out using the IX73 inverted fluorescence microscope

(Olympus Corporation).

Measurement of oxidative stress markers.

Myeloperoxidase (MPO), malondialdehyde (MDA) and superoxide

dismutase (SOD) oxidative stress marker activity was quantitatively

analyzed in both cell culture supernatants and BALF using

commercial assay kits according to the manufacturer's protocols.

All spectrophotometric measurements were carried out in triplicate

using the model 680 microplate reader (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.),

with appropriate blank and standard controls included in each assay

plate.

Statistical analysis. All quantitative data,

except for survival data, are presented as the mean ± standard

deviation (SD) from at least three independent experiments, with

each experiment carried out in triplicate. Statistical analyses

were carried out using GraphPad Prism (version 6.0; Dotmatics). For

comparisons between multiple groups, one-way analysis of variance

(ANOVA) was performed: for data with homogeneous variances, Tukey's

post hoc test was used; for data with heterogeneous variances,

Welch's ANOVA followed by Games-Howell's post hoc test was

employed. For the survival study, Kaplan-Meier survival curves were

generated, and differences between groups were compared for

statistical significance using the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. In

all analyses, a P-value of less than 0.05 (P<0.05) was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

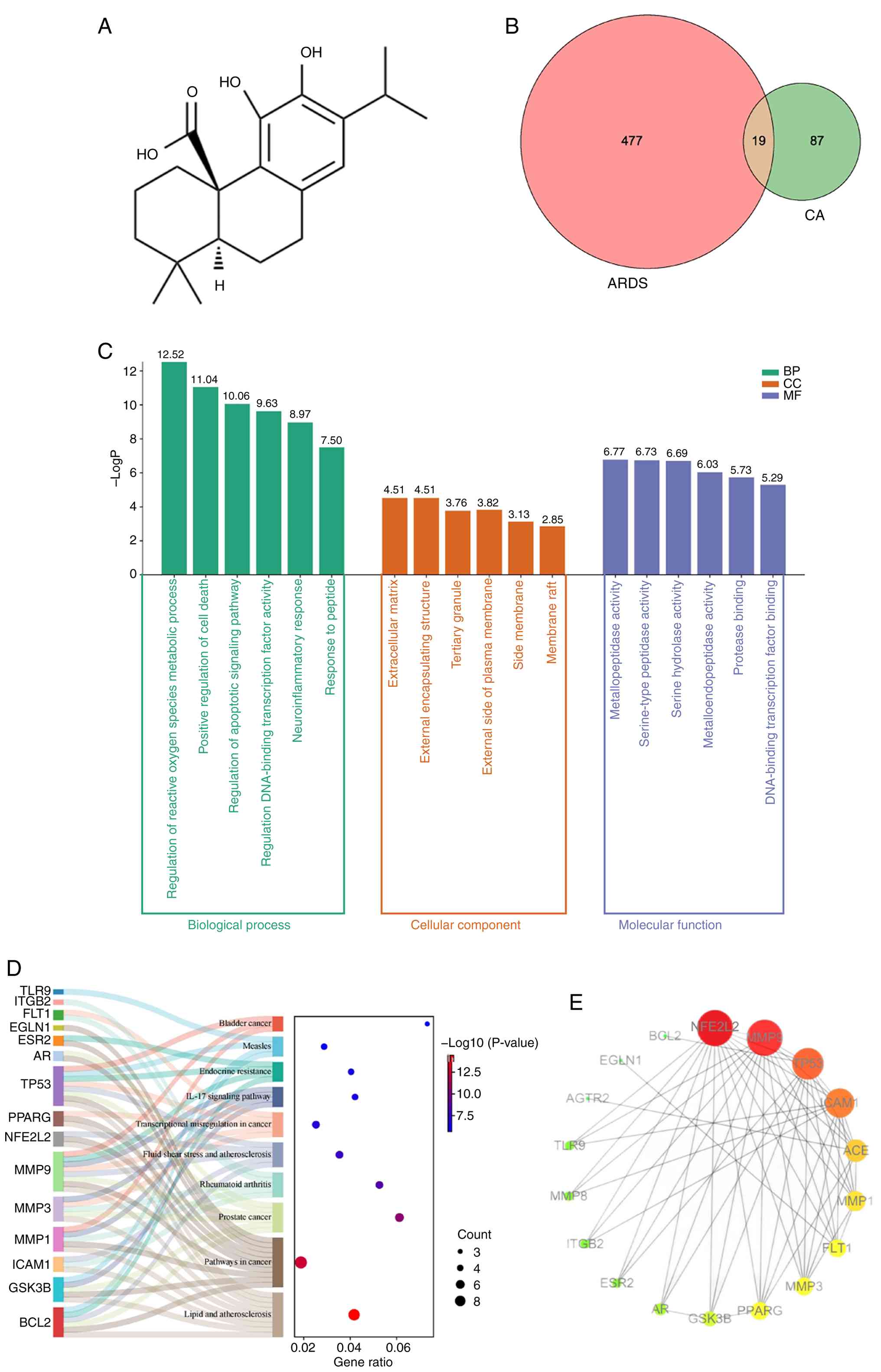

Network pharmacology analysis. Target

screening of CA and ARDS

The two-dimensional structure of CA was retrieved

from the PubChem database (Fig.

1A). Target prediction analysis using the SwissTargetPrediction

platform identified 106 potential CA target genes (probability

score, >0.1). In addition, 496 ARDS-associated genes were

compiled from comprehensive disease databases (GeneCards, 387

targets; DisGeNET, 109 targets) after removing duplicates.

Comparative analysis through a Venn diagram revealed 19 overlapping

genes between CA targets and ARDS-related genes (Fig. 1B), representing potential

therapeutic targets through which CA may exert its pharmacological

effects against ARDS. These 19 candidate targets were subsequently

prioritized for further network pharmacology analysis.

Functional enrichment analysis.

Bioinformatics analysis using the Metascape platform revealed

significant functional enrichment among the 19 common targets,

identifying 466 GO BP, 22 GO CC, 56 GO MF and 37 KEGG pathways. BP

analysis demonstrated that these targets were predominantly

involved in ‘regulation of reactive oxygen species metabolic

process’ (GO: 2000377), ‘positive regulation of cell death’,

‘regulation of apoptotic signaling pathway’ and ‘regulation of

DNA-binding transcription factor activity’, suggesting these BP may

mediate the therapeutic effects of CA in ARDS (Fig. 1C). MF analysis results demonstrated

that the common target genes were most involved in

‘metallopeptidase activity’, ‘serine-type peptidase activity’ and

‘serine hydrolase activity’. CC analysis results indicated that the

common target genes were the most predicated on the ‘extracellular

matrix’, ‘external encapsulating structure’ and ‘tertiary granule’.

Results of the KEGG analysis revealed that the 19 genes were mainly

enriched in ‘Fluid shear stress and atherosclerosis’, ‘Pathways in

cancer’, ‘Lipid and atherosclerosis’ and the ‘IL-17 signaling

pathway’ (Fig. 1D).

PPI network construction. Among the 19 genes,

ADCY10 was excluded from PPI network construction as it exhibited

no association with the other genes. The finalized network

comprised 18 nodes and 80 edges, illustrating the complex web of

interactions among the remaining targets (Fig. 1E). Hub targets were subsequently

identified to uncover the core characteristics of the network.

These key nodes were pinpointed based on their degree values, which

effectively captured their relative importance and connectivity

within the network, providing insight into the functional

architecture of the network.

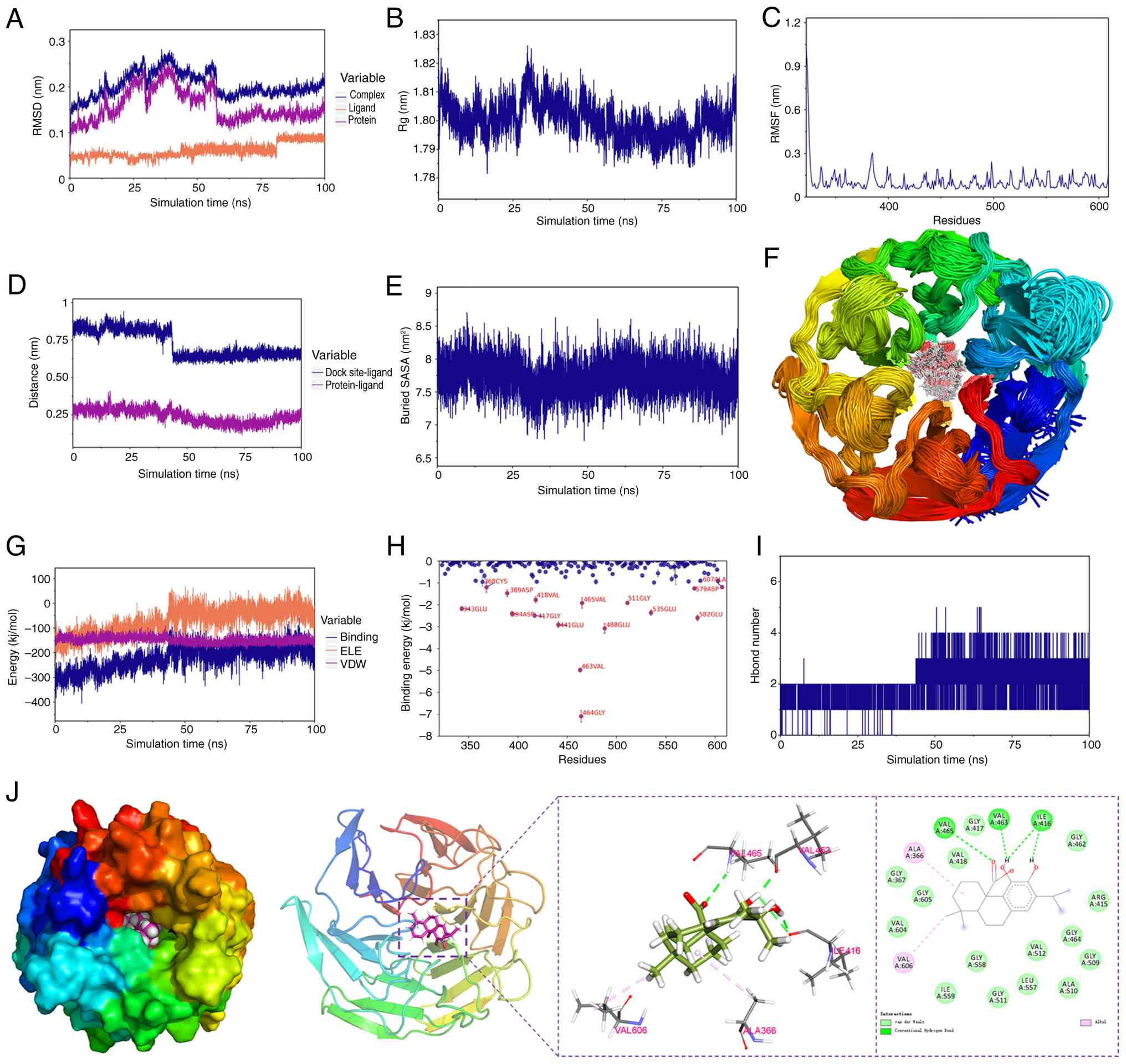

Molecular docking and MD. Following

comprehensive analysis of the PPI network, NFE2L2 (encoding the

Nrf2 protein) emerged as the pivotal target. Subsequently, to

explore the potential binding mode and interaction mechanism,

molecular docking experiments were conducted between NFE2L2 and CA.

A total of 10 different docking sites were assessed, with findings

indicating that the docking affinity was <-5 kcal/mol (Table III). Subsequently, the top-ranked

conformation from the molecular docking results, which demonstrated

the highest binding affinity, was subjected to MD simulations for

further validation. All results suggested that NFE2L2 and CA are

capable of stable binding (Fig.

2). As shown in Fig. 2A-C, the

RMSD of the complex, protein and ligand CA, the radius of gyration,

and the root-mean-square fluctuation of amino acid residues all

stabilized over the 100 nsec molecular dynamics simulation,

indicating that the complex system reached equilibrium and the

binding conformation remained stable. Further binding analysis

revealed that the distance between CA and the Nrf2 binding site, as

well as the buried solvent-accessible surface area, remained stable

during the later stages of the simulation (Fig. 2D-E). Moreover, superimposed

simulation conformations demonstrated that CA stably bound the

initial docking site (Fig. 2F).

Binding free energy calculations (molecular mechanics

Poisson-Boltzmann surface area) revealed that van der Waals

interactions served as the primary driving force for binding.

Additionally, residual energy decomposition analysis identified key

amino acids, such as GLY-464 and VAL-463, that contributed

significantly to the binding energy (Fig. 2H). These results confirm at the

atomic level that CA and Nrf2 can form a stable complex, providing

a theoretical foundation for subsequent experimental

validation.

| Table IIIMolecular docking affinity between

carnosic acid and the target protein nuclear factor erythroid

2-related factor 2. |

Table III

Molecular docking affinity between

carnosic acid and the target protein nuclear factor erythroid

2-related factor 2.

| Dock poses | Affinity,

kcal/mol | RMSD l.b. | RMSD u.b. |

|---|

| 1 | -9.606 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | -9.508 | 1.605 | 6.209 |

| 3 | -9.473 | 1.861 | 6.457 |

| 4 | -8.859 | 4.454 | 7.007 |

| 5 | -8.743 | 4.177 | 6.832 |

| 6 | -8.615 | 4.637 | 7.487 |

| 7 | -8.588 | 3.847 | 6.335 |

| 8 | -8.396 | 2.010 | 3.009 |

| 9 | -8.266 | 1.572 | 2.136 |

| 10 | -7.930 | 6.649 | 10.900 |

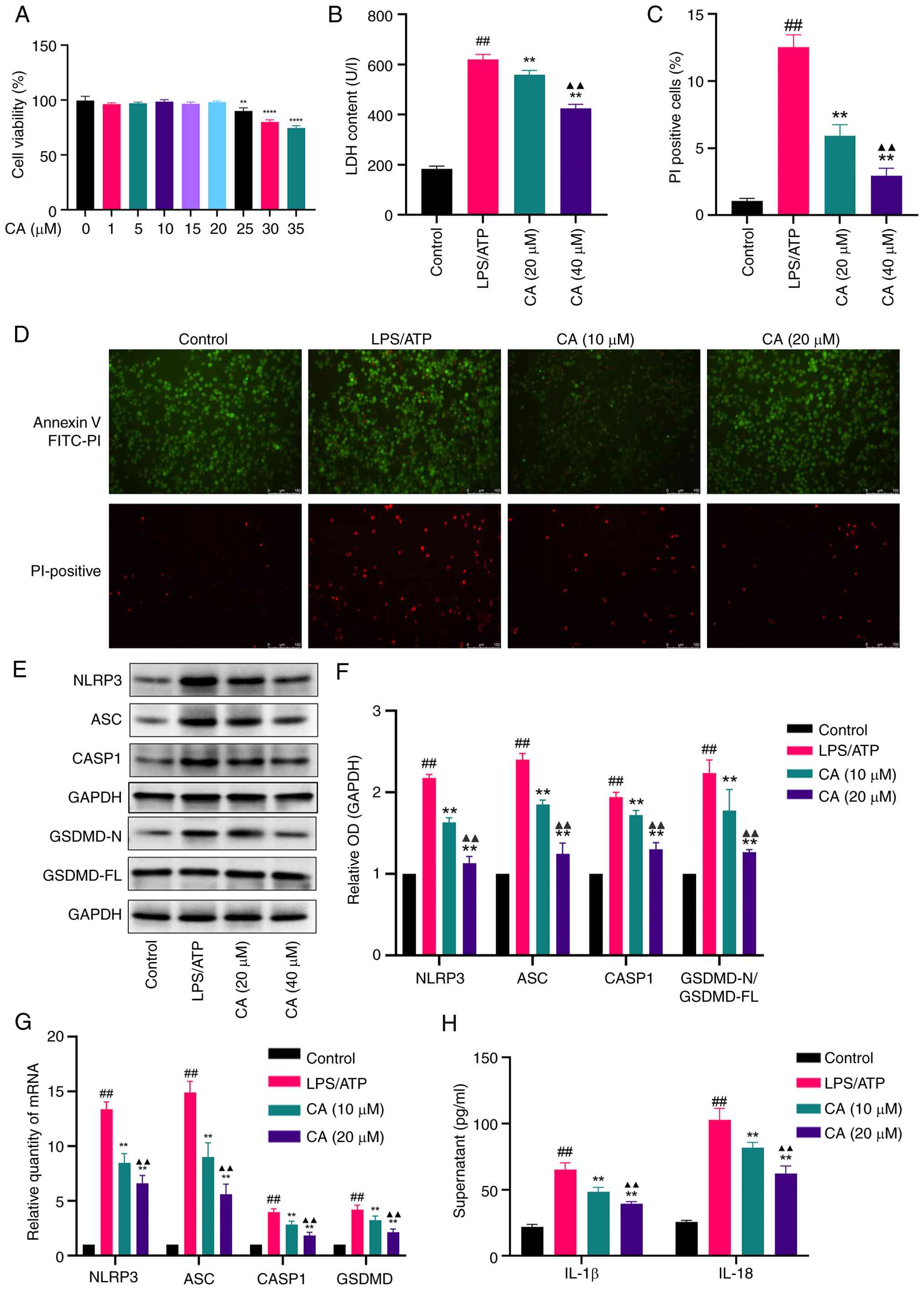

Biological experiment results. Effect

of CA on MH-S cell viability

A CCK-8 assay was used to assess the cytotoxic

effects of CA on MH-S cells. The results demonstrated that low CA

concentrations (1-20 µM) did not significantly affect cell

viability. Based on these findings, 10 and 20 µM CA concentrations

were selected for subsequent experimental investigation (Fig. 3A).

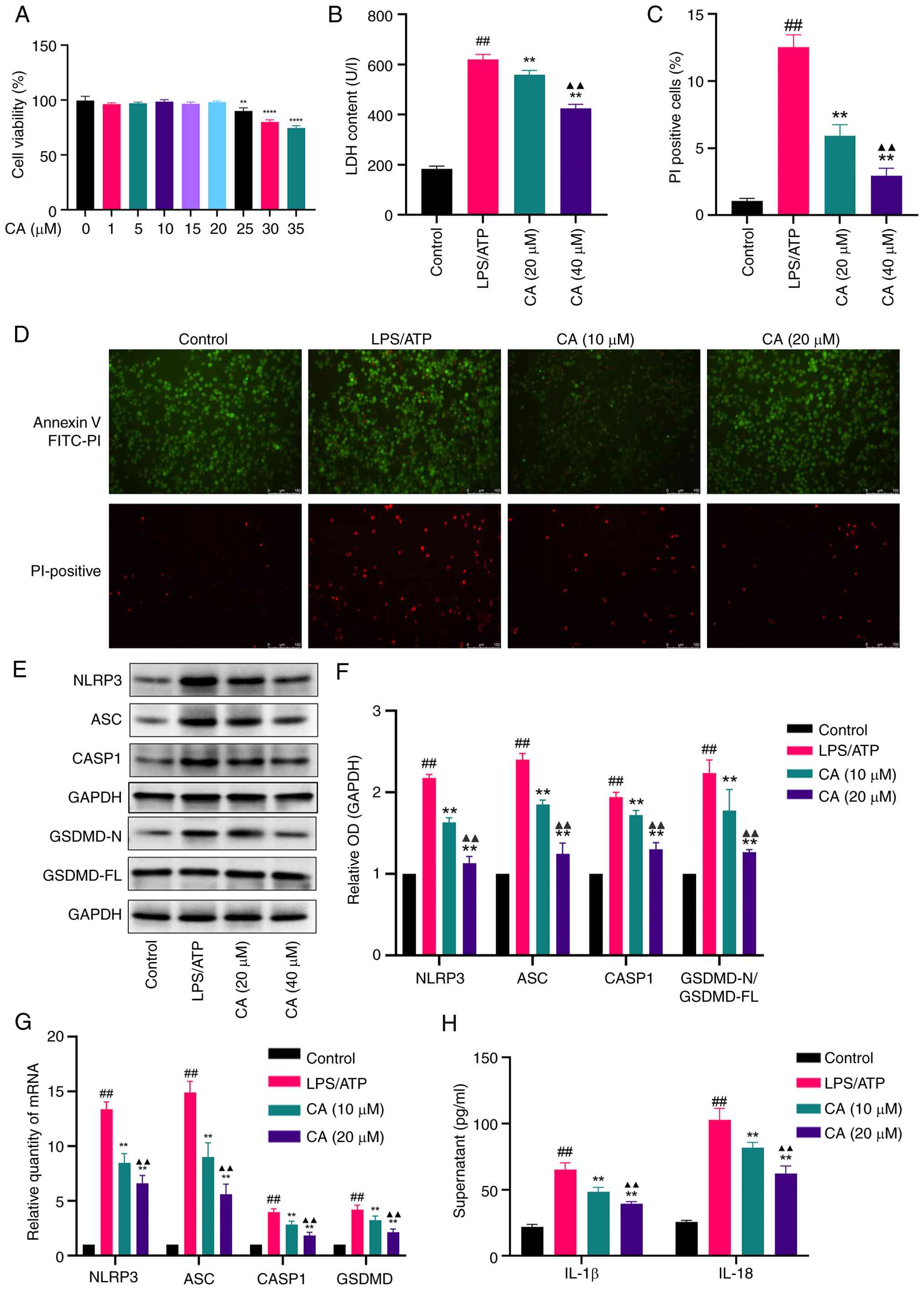

| Figure 3CA inhibits pyroptosis in

LPS/ATP-stimulated MH-S cells. (A) Cytotoxicity of CA evaluated by

a Cell Counting Kit-8 assay. (B) LDH release in the supernatant

following CA treatment. (C) Percentage of PI-positive cells

following CA treatment. (D) Annexin V-FITC (green)

double-fluorescent staining representing apoptosis levels and PI

(red) double-fluorescent staining representing cell necrosis

levels. Scale bar, 100 µm. PI-positive cell rate was calculated

using ImageJ software. (E) Representative bands and (F) analysis of

protein expression of NLRP3, ASC, CASP1 and GSDMD detected by

western blotting. (G) mRNA expression levels of NLRP3, ASC, CASP1

and GSDMD detected by reverse transcription-quantitative PCR. (H)

Production of IL-18 and IL-1β in the supernatant measured by ELISA.

Data are presented as the mean ± SD of three independent

experiments. ##P<0.01 vs. control;

**P<0.01, ****P<0.0001 vs. LPS/ATP;

▲▲P<0.01 vs. CA (10 µM). CA, carnosic acid; LPS,

lipopolysaccharide; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; NLRP3, NLR family

pyrin domain containing 3; ASC, apoptosis-associated speck-like

protein containing a CARD; CASP1, caspase-1; GSDMD, gasdermin D;

OD, optical density. |

CA inhibits pyroptosis in LPS/ATP-stimulated MH-S

cells. To assess the impact of CA on pyroptosis, MH-S cells

were treated with LPS and ATP. Pyroptosis was then quantified by

measuring the proportion of PI-positive cells (Annexin V-FITC and

PI double staining, a combination of methods evaluating membrane

integrity and inflammasome activation) and LDH levels in the cell

supernatant. The findings indicated a notable reduction in both LDH

release (Fig. 3B) and PI-positive

cells (Fig. 3C and D) following CA treatment. During the

early stages of apoptosis and pyroptosis, phosphatidylserine

becomes externalized on the cell membrane. However, pyroptosis

ultimately leads to complete membrane rupture. Consequently, a cell

population positive for Annexin V-FITC (green) and negative for PI

(red) indicates an early stage of cell death, while cells positive

for both Annexin V and PI represent a later stage characterized by

loss of membrane integrity. The results demonstrated that LPS/ATP

stimulation significantly increased the proportion of

double-positive cells, an effect that was effectively reversed by

CA treatment. To assess NLR family pyrin domain containing 3

(NLRP3) inflammasome activation, key markers were examined,

including apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a CARD

(ASC), caspase-1 (CASP1), the N-terminal fragment of GSDMD and the

downstream cytokines IL-18 and IL-1β. CA treatment significantly

inhibited the protein expression of these key markers induced by

LPS/ATP and their corresponding mRNA upregulation (Fig. 3E-G). Furthermore, CA markedly

attenuated the release of IL-18 and IL-1β in the supernatant

compared with the LPS/ATP-stimulated group (Fig. 3H). Collectively, these outcomes

indicated that CA may effectively hinder LPS/ATP-induced pyroptosis

in MH-S cells by inhibiting NLRP3 activation and averting GSDMD

cleavage.

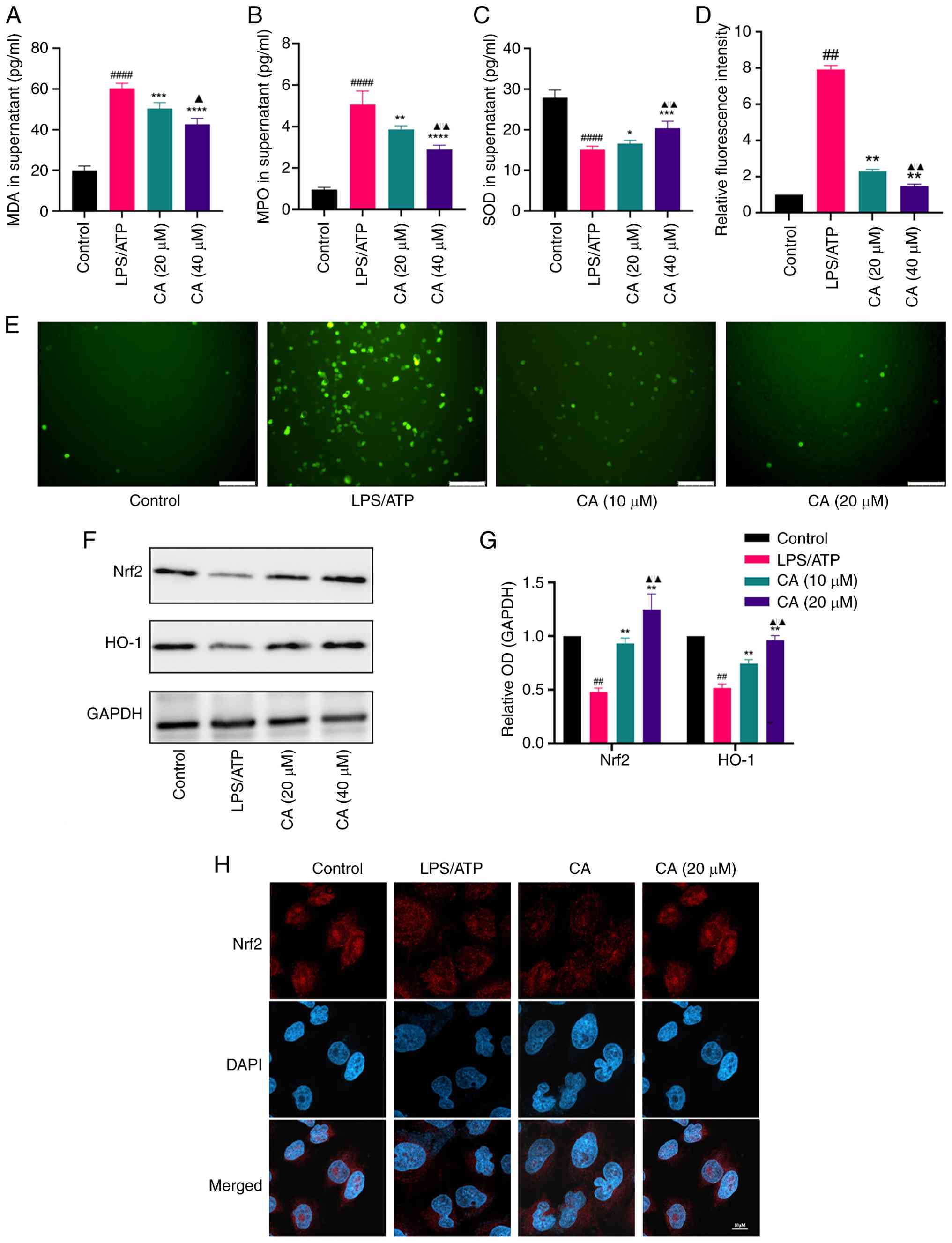

CA activates Nrf2 and alleviates oxidative stress

in LPS/ATP-stimulated MH-S cells. CA has previously been

documented to exhibit potent antioxidative properties (28); however, its protective effects

against oxidative stress in MH-S cells remain unclear. Thus, the

antioxidant effects and underlying mechanisms of CA in

LPS/ATP-challenged MH-S cells were investigated.

To assess the antioxidant properties of CA, the key

oxidative stress markers MDA, MPO and SOD were analyzed. CA

treatment significantly reduced MDA and MPO levels while enhancing

SOD activity in MH-S cells compared with the LPS/ATP group

(Fig. 4A-C). In addition, LPS/ATP

stimulation led to a notable increase in intracellular ROS

production in MH-S cells compared with that in the control group,

with CA treatment effectively mitigating this increase (Fig. 4D and E).

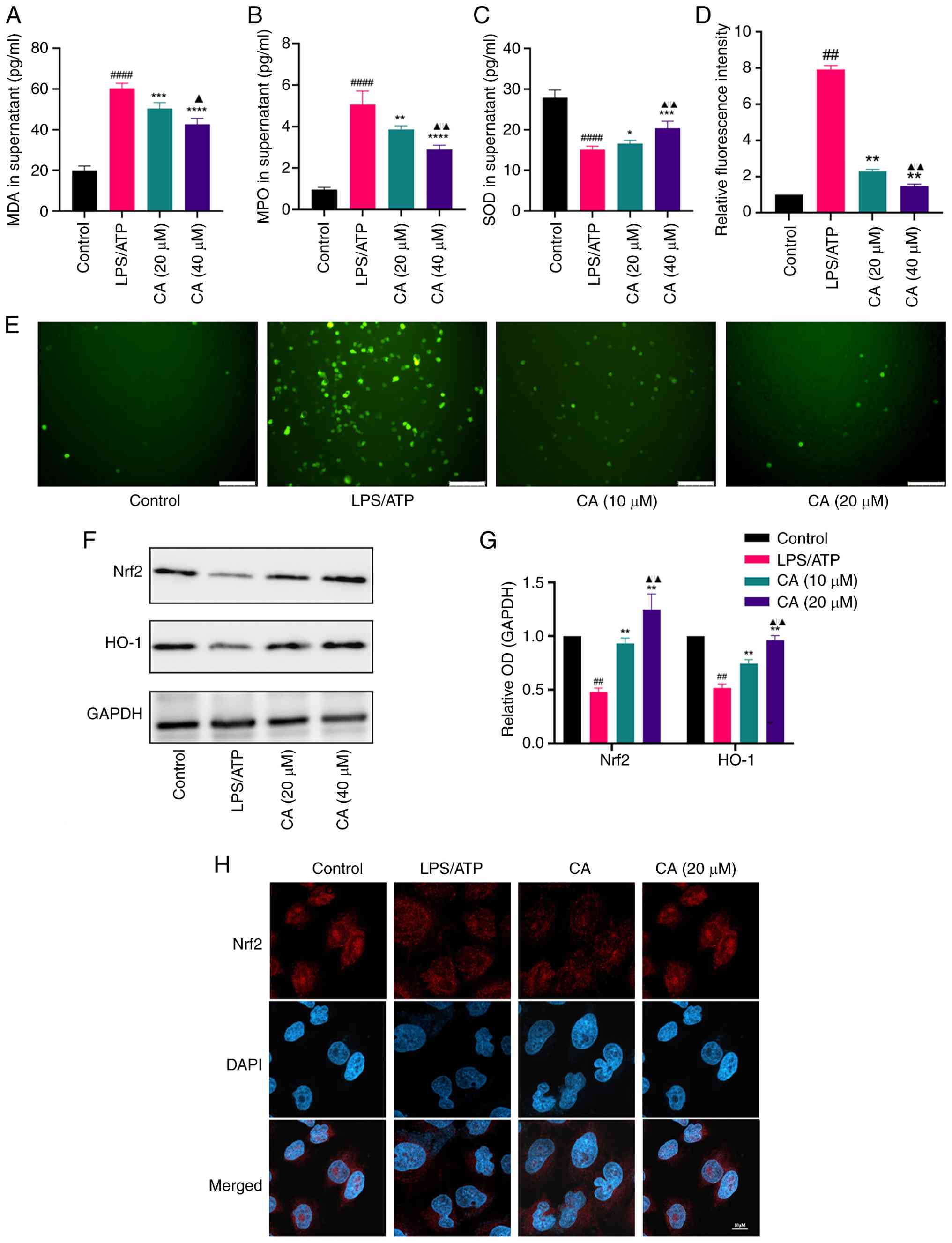

| Figure 4CA activates Nrf2 and improves the

oxidative stress in LPS/ATP-stimulated MH-S cells. Levels of (A)

MDA, (B) MPO and (C) SOD in the supernatant measured by ELISA. (D

and E) ROS generation of MH-S cells detected by

2',7'-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate cellular ROS detection

assay, with fluorescence intensity calculated using ImageJ

software. Scale bar, 100 µm. (F) Representative bands and (G)

analysis of protein expression of Nrf2 and HO-1 detected by western

blotting. (H) Nuclear translocation of the Nrf2 subunit determined

by an immunofluorescence assay. Scale bar, 20 µm. Data are

presented as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments.

##P<0.01, ####P<0.0001 vs. control;

*P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001 vs. LPS/ATP

group; ▲P<0.05, ▲▲P<0.01 vs. CA (10

µM). CA, carnosic acid; Nrf2, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related

factor 2; HO-1, heme oxygenase-1; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; MDA,

malondialdehyde; MPO, myeloperoxidase; SOD, superoxide dismutase;

ROS, reactive oxygen species; OD, optical density. |

Subsequently, the molecular mechanisms responsible

for the antioxidant properties of CA were explored. Nrf2, a

regulator of cellular antioxidant responses, was focused on to

determine its involvement in CA-mediated oxidative stress

protection (29). The findings

demonstrated that, compared to the LPS/ATP-stimulated group, CA

treatment significantly augmented the protein expression of both

total Nrf2 and heme oxygenase-1 (Fig.

4F and G) and facilitated the

nuclear translocation of Nrf2 (Fig.

4H). Collectively, these findings suggested that CA may

alleviate oxidative stress and activate Nrf2 in MH-S cells.

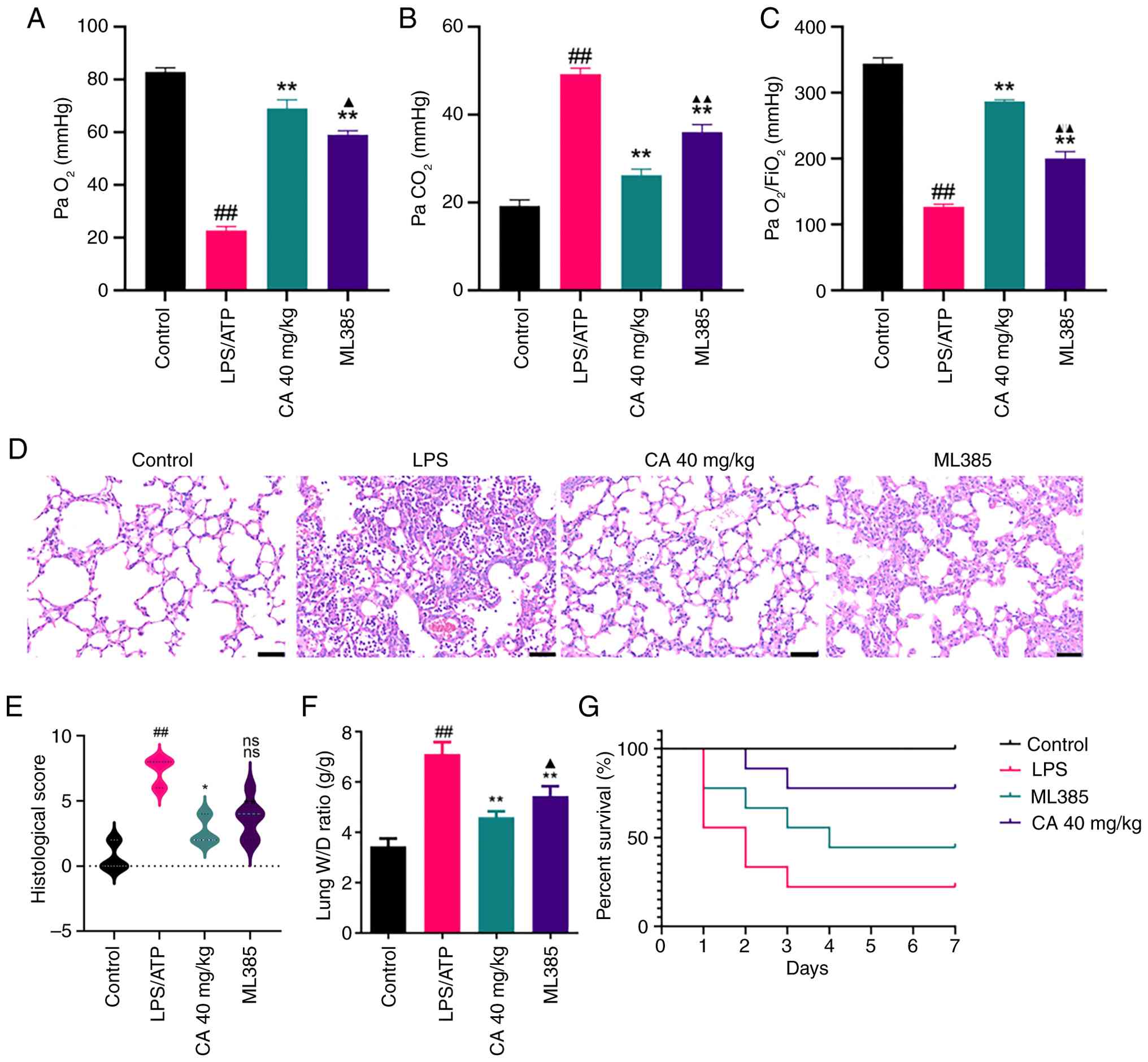

CA attenuates LPS-induced ARDS in mice.

Arterial blood gas analysis showed that, in comparison with the

control group, the LPS group exhibited a notable decrease in

PaO2 and PO2/FiO2 levels, and a

marked increase in PaCO2 levels (Fig. 5A-C). These characteristic

alterations in blood gas parameters confirm the successful

establishment of the ARDS mouse model (23). The mice that received treatment

with CA demonstrated an elevation in PaO2 levels and a

significant decrease in PaCO2 levels, indicating a

marked improvement in pulmonary gas exchange, thus supporting its

potential for clinical application.

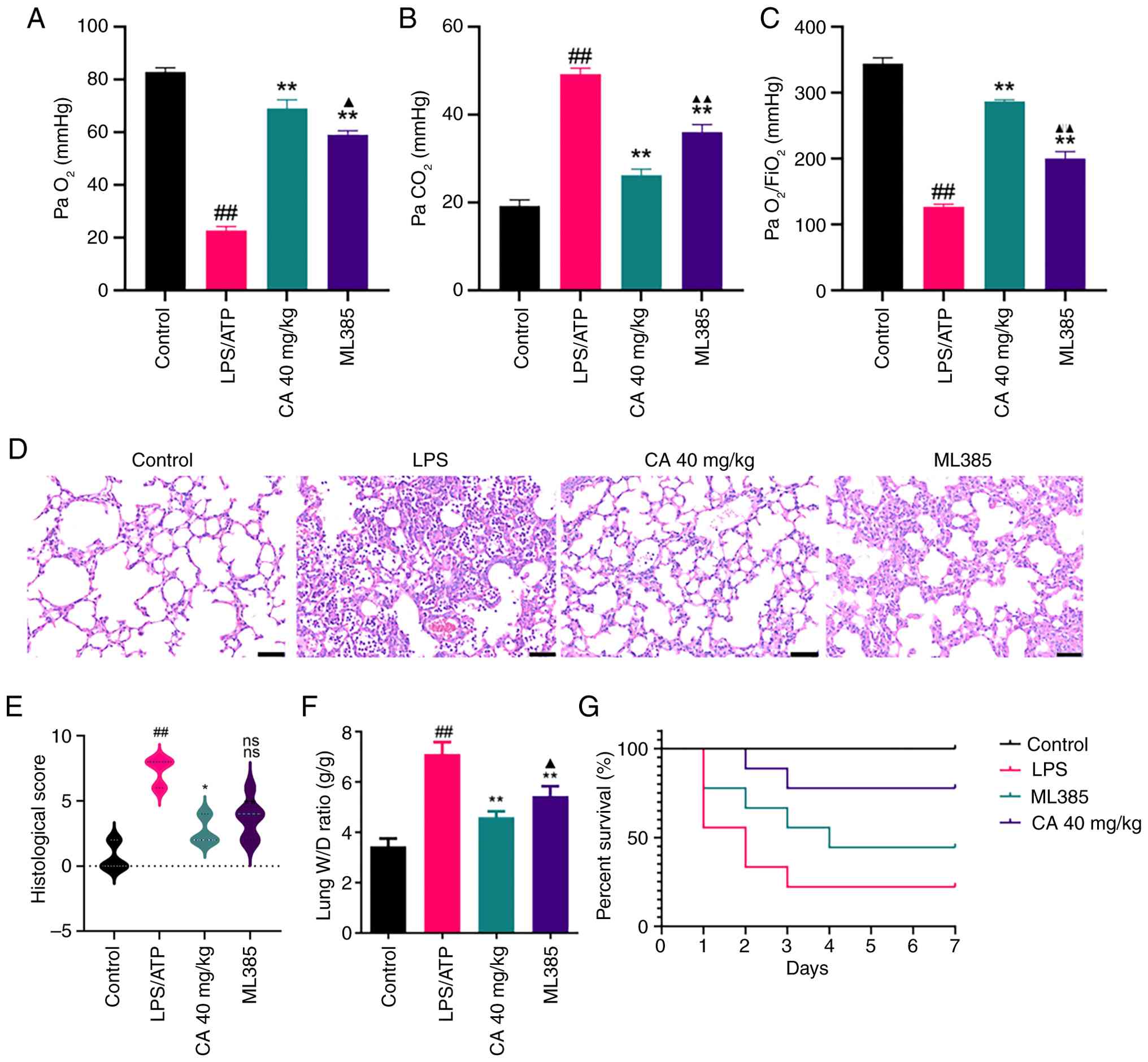

| Figure 5CA attenuates LPS-induced acute

respiratory distress syndrome in mice. (A) PaO2 and (B)

PaCO2 data of each group. (C)

PaO2/FiO2 ratio of each group. (D)

Histopathological variation in lung tissues determined using

H&E staining. Scale bar, 50 µm. (E) Lung injury score. (F) Lung

W/D ratio assessed using histological sections. (G) Survival rate

for mice observed twice daily for 7 days. Data are presented as the

mean ± SD of three independent experiments. ##P<0.01

vs. control; *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs. LPS;

▲P<0.05, ▲▲P<0.01 vs. CA (40 mg/kg).

CA, carnosic acid; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; ns, not significant;

PaO2, partial pressure of oxygen; PaCO2,

partial pressure of carbon dioxide; FiO2, fraction of

inspired oxygen; W/D, wet dry. |

The effects of CA against LPS-induced ARDS were

subsequently evaluated by performing histopathological analysis of

lung tissues using H&E staining (Fig. 5D). Compared with in the control

group, LPS-challenged mice exhibited significantly elevated

histological scores, characterized by extensive inflammatory cell

infiltration, alveolar hemorrhage and interstitial edema (Fig. 5E). Notably, CA treatment markedly

attenuated these pathological alterations and significantly

improved histological scores. These findings provide histological

evidence for the protective role of CA in mitigating LPS-induced

acute lung injury.

To further assess pulmonary edema formation, lung

tissue water content was quantified by measuring the W/D weight

ratio. As shown in Fig. 5F, ARDS

mice exhibited a significantly elevated lung W/D ratio compared

with that in the control group, indicating severe pulmonary edema.

Notably, CA treatment effectively normalized this parameter.

Together with the histological findings, these results demonstrated

that CA could confer marked protection against ARDS by attenuating

pathological vascular permeability and edema formation.

Consistent with its reversal of CA-mediated

improvements in lung injury parameters (Fig. 5A-F), pharmacological inhibition of

Nrf2 with ML385 also significantly attenuated the survival benefit

conferred by CA. Survival analysis via the Kaplan-Meier method

revealed marked differences between groups (log-rank test, Fig. 5G). LPS-challenged mice only

exhibited a 20% survival rate, treatment with CA markedly improved

survival rates to >50%. Pharmacological inhibition of Nrf2 with

ML385 attenuated the protective effects of CA, thus reducing

survival rates. These findings suggested that CA may provide a

notable survival benefit in LPS-induced ARDS, mediated through Nrf2

pathway activation.

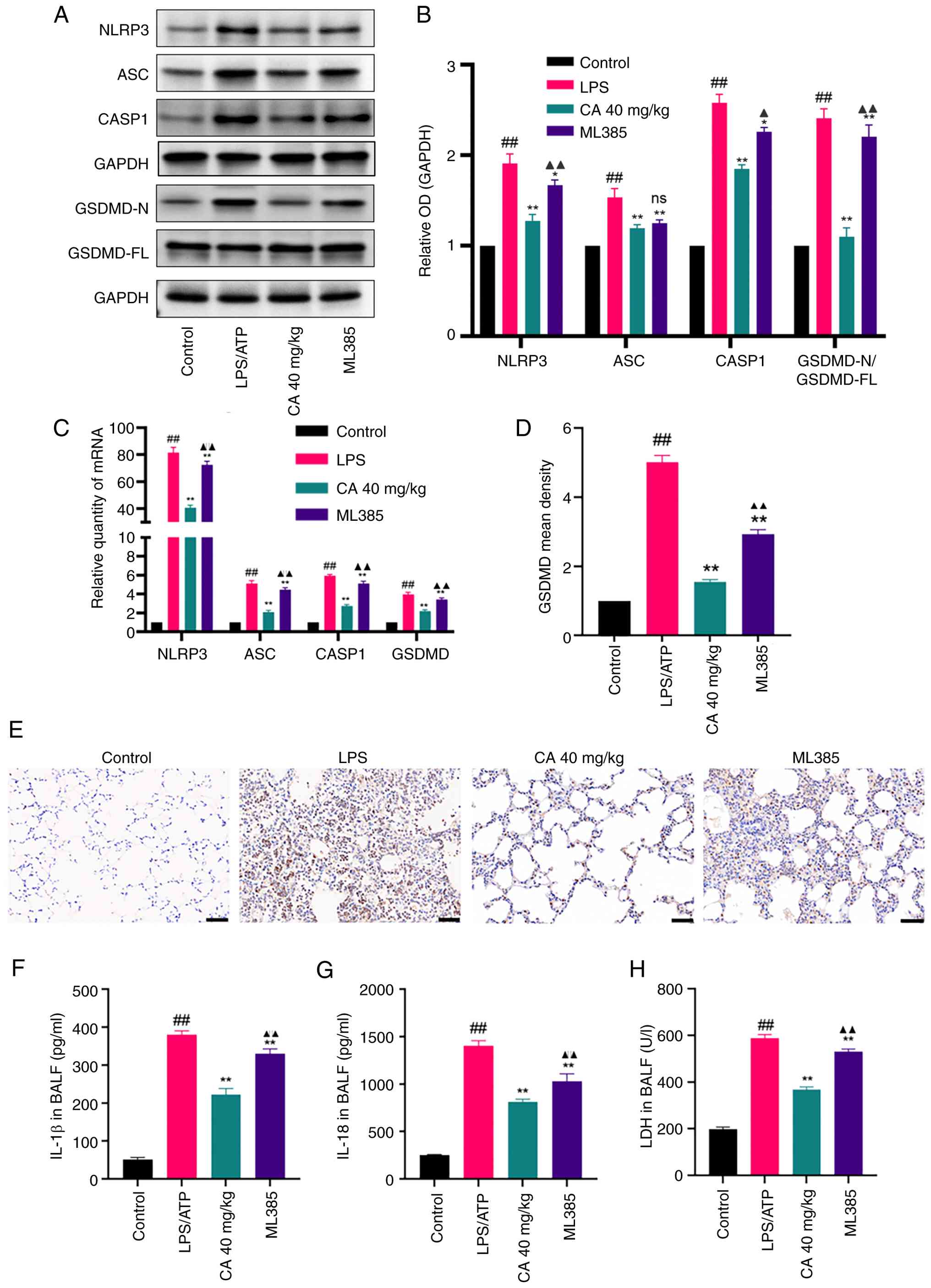

CA inhibits NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated

pyroptosis in mice with LPS-induced ARDS through activation of

Nrf2. To further explore the anti-pyroptotic effect of CA and

its protective role in LPS-induced ARDS, the impact of CA on NLRP3

inflammasome-mediated pyroptosis was investigated in vivo.

Quantitative analysis revealed that LPS challenge induced

pyroptotic activation, as evidenced by significant upregulation of

NLRP3 inflammasome components (NLRP3, ASC, CASP1 and GSDMD) at both

transcriptional and translational levels (Fig. 6A-E). This was associated with

elevated BALF concentrations of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β

(Fig. 6F) and IL-18 (Fig. 6G), and increased LDH release

(Fig. 6F). Notably, CA exerts its

effects by selectively inhibiting the activation of the NLRP3

inflammasome, reducing LDH release and decreasing IL-18 and IL-1β

secretion, thereby demonstrating the anti-pyroptotic effects

observed in vitro through suppression of the NLRP3

inflammasome pathway.

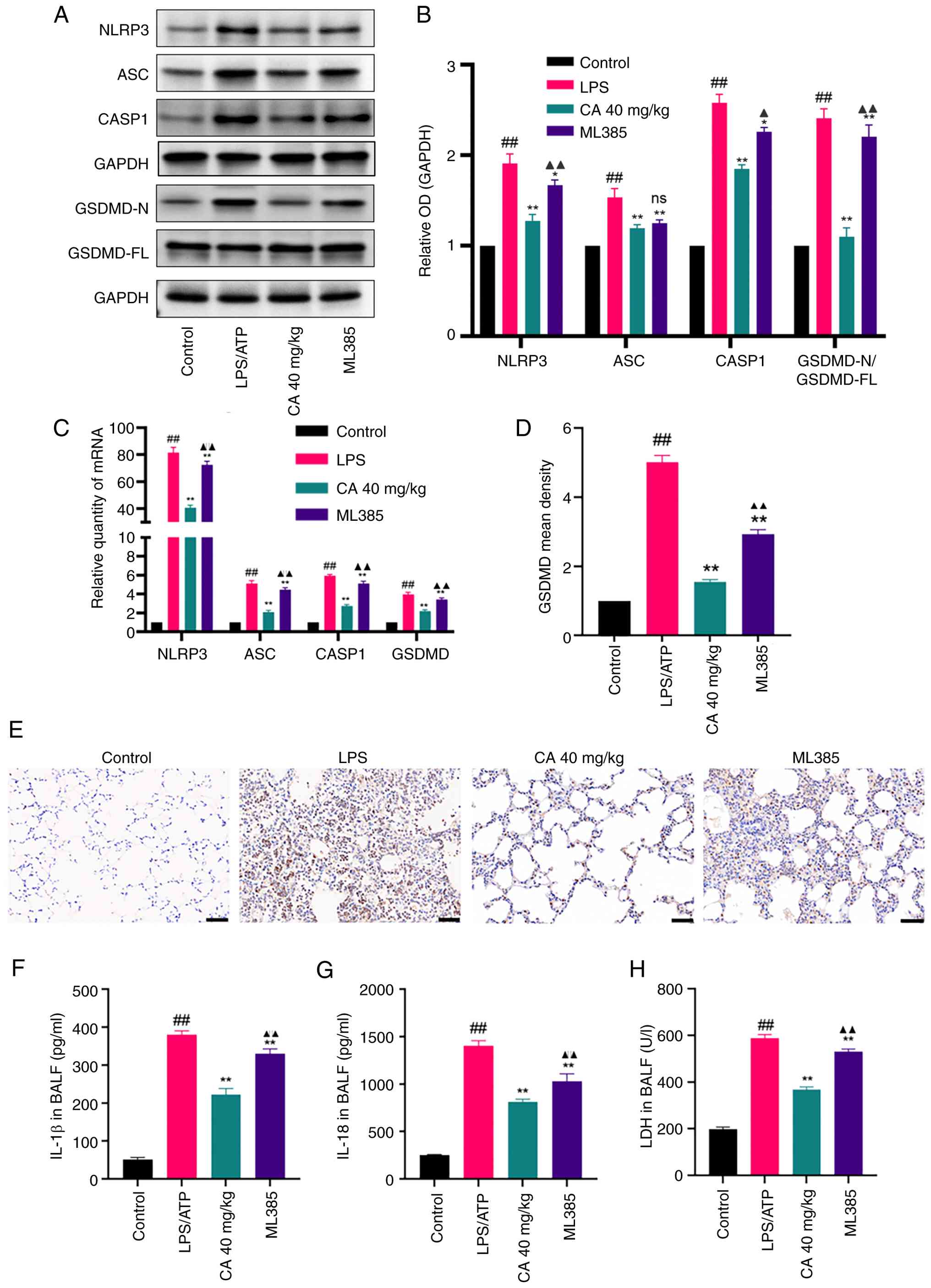

| Figure 6CA inhibits NLRP3

inflammasome-mediated pyroptosis in LPS-induced acute respiratory

distress syndrome in mice. (A) Representative bands and (B)

analysis of protein expression of NLRP3, ASC, CASP1 and GSDMD

detected by western blotting. (C) mRNA expression levels of NLRP3,

ASC, CASP1 and GSDMD detected by reverse transcription-quantitative

PCR. (D) Analysis and (E) immunohistochemical staining showing the

positive rate of GSDMD protein expression in lung tissues of mice

in each group. Scale bar, 50 µm. Production of (F) IL-18 and (G)

IL-1β in the BALF measured by ELISA. (H) LDH release in the BALF.

Data are presented as the mean ± SD of three independent

experiments. ##P<0.01 vs. control;

*P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs. LPS;

▲P<0.05, ▲▲P<0.01 vs. CA (40 mg/kg).

CA, carnosic acid; NLRP3, NLR family pyrin domain containing 3;

LPS, lipopolysaccharide; ASC, apoptosis-associated speck-like

protein containing a CARD; CASP1, caspase-1; GSDMD, gasdermin D;

LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; BALF, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid; ns,

not significant; OD, optical density. |

To explore whether the effects of CA were

Nrf2-dependent, mice were pretreated with the Nrf2 inhibitor ML385.

This pretreatment eliminated the ability of CA to downregulate

NLRP3 inflammasome components and reduce inflammatory mediator

release (Fig. 6A-H). Therefore,

these findings suggested that CA could attenuate LPS-induced ARDS

by suppressing NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated pyroptosis, a process

partially dependent on Nrf2 activation.

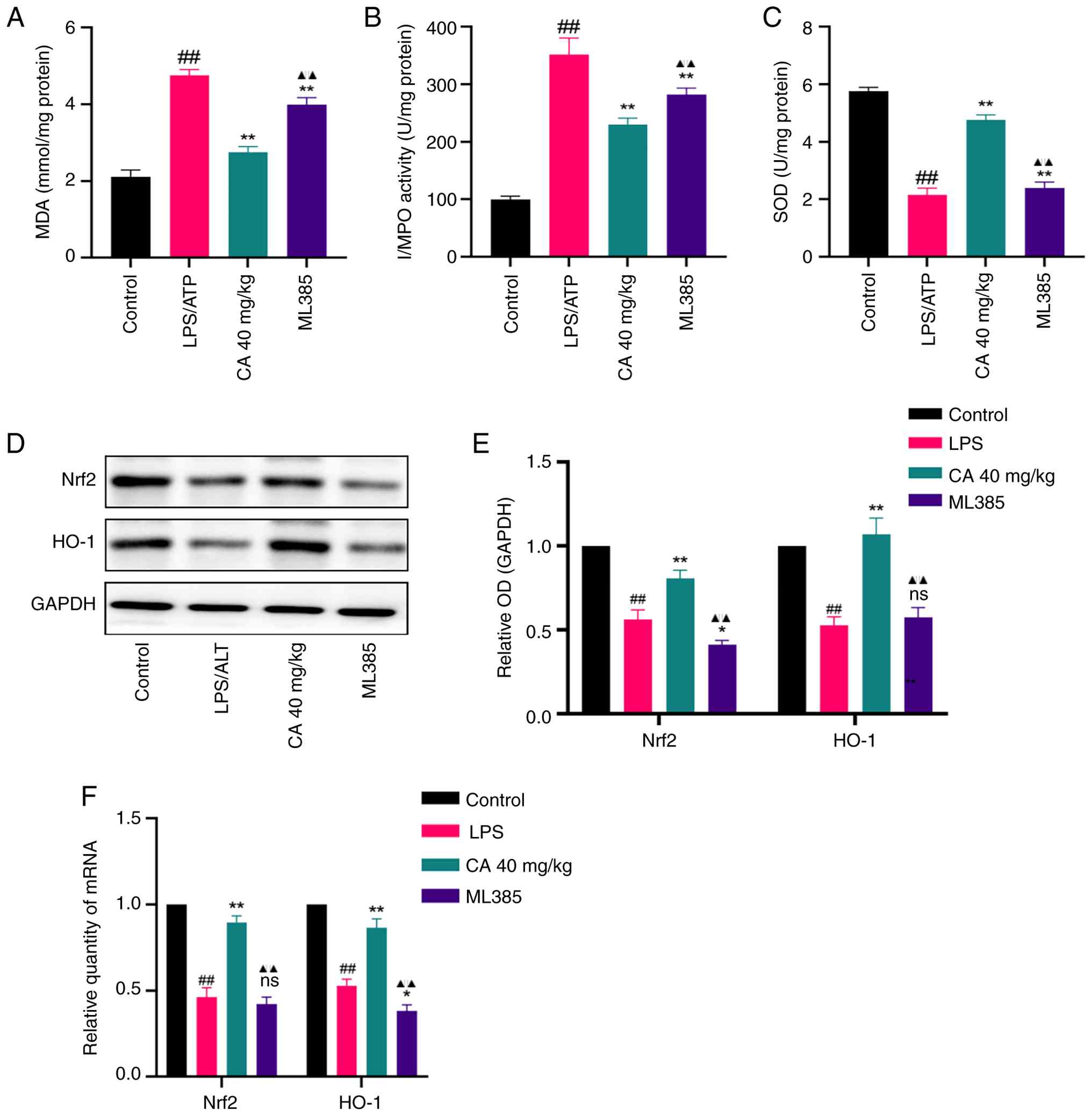

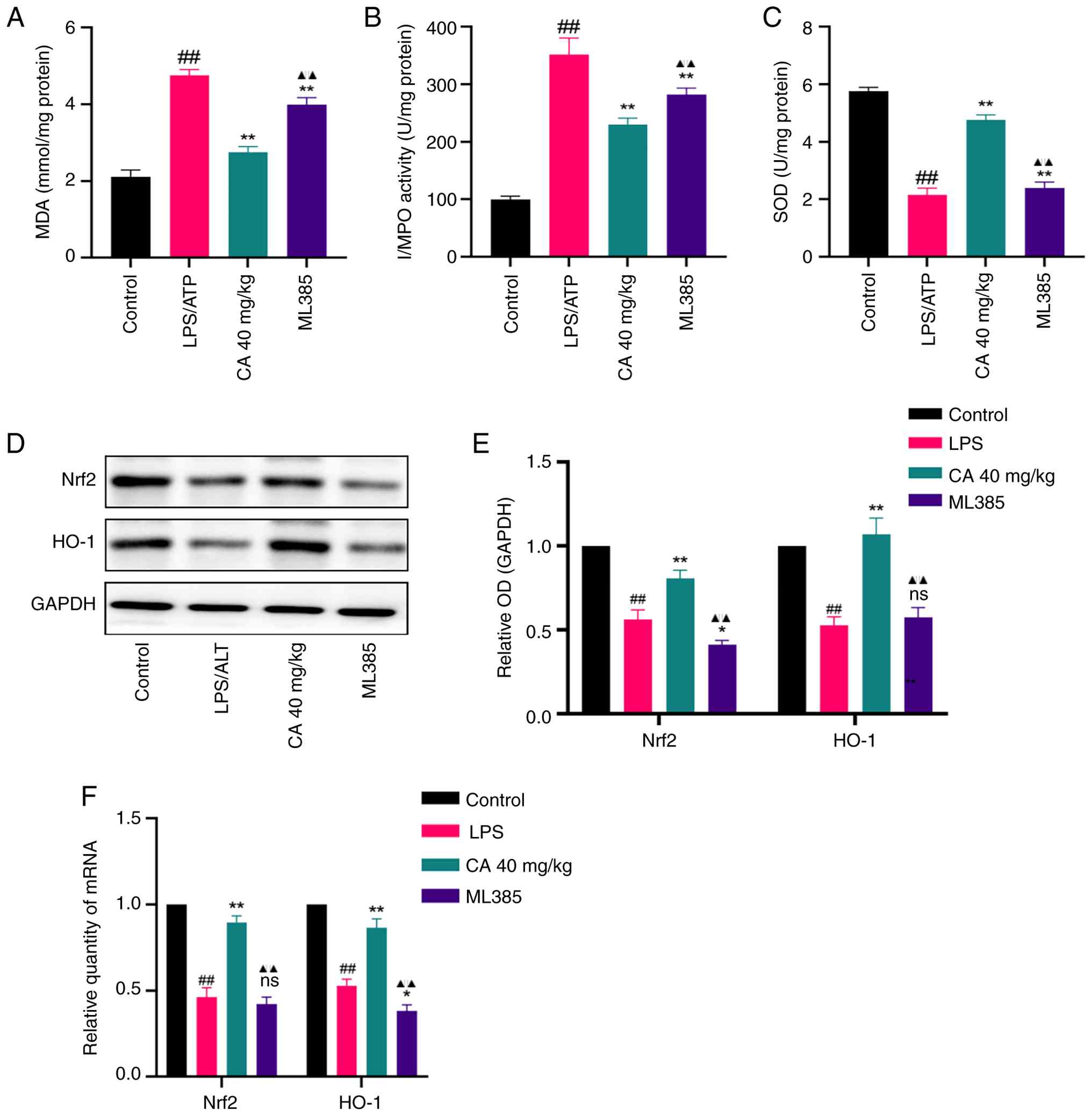

CA alleviates LPS-induced ARDS through

Nrf2-dependent antioxidant mechanisms. MPO, MDA and SOD

activity was assessed to evaluate whether CA exerted a protective

effect against LPS-induced ARDS through its antioxidant properties.

In addition, the protein and mRNA levels of Nrf2 and HO-1 were

measured. The findings revealed that LPS administration notably

elevated MPO and MDA activities, while suppressing SOD levels in

the BALF (Fig. 7A-C). However,

these changes were effectively prevented by pretreatment with CA.

Additionally, treatment with CA resulted in a notable upregulation

of both Nrf2 and HO-1 at both transcriptional and translational

levels in the lung tissue of mice (Fig. 7D-F).

| Figure 7CA exerts an anti-oxidative effect in

LPS-induced acute respiratory distress syndrome. Levels of (A) MDA,

(B) MPO and (C) SOD in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid measured by

ELISA. (D) Representative bands and (E) analysis of protein

expression of Nrf2 and HO-1 detected by western blotting. (F) mRNA

expression of Nrf2 and HO-1 detected by reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR. Data are presented as the mean ± SD

of three independent experiments. ##P<0.01 vs.

control; *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs. LPS;

▲▲P<0.01 vs. CA (40 mg/kg). CA, carnosic acid; LPS,

lipopolysaccharide; MDA, malondialdehyde; MPO, myeloperoxidase;

SOD, superoxide dismutase; Nrf2, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related

factor 2; HO-1, heme oxygenase-1; ns, not significant; OD, optical

density. |

To further substantiate whether the antioxidant

protection offered by CA against LPS-induced ARDS was dependent

upon Nrf2 activation, mice were pretreated with the aforementioned

ML385. ML385 not only abolished the CA-mediated reduction in MPO

and MDA levels and the restoration of SOD activity (Fig. 7A-C), but also attenuated the

CA-induced upregulation of both Nrf2 and HO-1 (Fig. 7D-F). These findings indicated that

Nrf2 activation constitutes an essential mechanism underlying the

antioxidant protection of CA in LPS-induced ARDS.

Discussion

ARDS is a severe respiratory disease marked by high

rates of mortality (30-50%). To the best of our knowledge, at the

present time, no treatment has been demonstrated as completely

effective and conclusive for managing ARDS (2). As phytochemistry and pharmacological

research have advanced, numerous natural products exhibiting

antioxidant (30,31), anti-inflammatory (32,33)

and antibacterial (34,35) properties have emerged.

Consequently, there is a growing interest in utilizing the

botanical constituents of traditional medicines as potential

preventative and therapeutic agents for ARDS (4,36).

CA, a naturally occurring compound derived from Rosmarinus

officinalis Linnaeus, has demonstrated promising antioxidant

and anti-inflammatory effects (37,38).

The present study systematically investigated the therapeutic

potential and molecular mechanisms of CA against LPS-induced ARDS,

employing an integrative approach combining network pharmacology,

molecular docking, MD simulations, and comprehensive in

vitro and in vivo validation experiments.

Network pharmacology identified 19 overlapping

targets between CA and ARDS, with NFE2L2 (Nrf2) emerging as the hub

target based on Venn and PPI network analysis. GO analysis

suggested that the regulation of the ROS metabolic process is an

important biological process in the mechanism of how CA treats

ARDS. Research has suggested that uncontrolled oxidative stress

markedly aggravates pulmonary inflammation, and accelerates the

development and progression of ARDS (39,40).

Central to this process is Nrf2, a key transcriptional factor that

governs cellular antioxidant defense systems and maintains redox

equilibria. Nrf2 activation induces the expression of

cytoprotective enzymes, including HO-1, creating a key defense

mechanism against oxidative damage. Emerging evidence has indicated

that Nrf2/HO-1 pathway activation is specifically associated with

ARDS mitigation through oxidative stress suppression (41,42).

Building on these findings and considering the documented

antioxidant properties of CA, it was hypothesized that CA could

ameliorate LPS-induced ARDS through Nrf2/HO-1 pathway activation.

Computational analyses, including molecular docking and MD

simulations, demonstrated that CA forms stable binding complexes

with the Nrf2 protein, perhaps indicating direct modulation of this

transcriptional regulator. This prediction was experimentally

validated in both cellular and animal models, whereby CA

upregulated the protein and mRNA expression levels of Nrf2 and

HO-1, decreased the levels of MPO and MDA, and increased the level

of SOD. CA was also found to exert its antioxidant effects by

reversing the LPS-induced downregulation of Nrf2, suggesting that

CA serves an antioxidant role in LPS-induced ARDS through

modulation of the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway.

KEGG pathway enrichment analysis revealed that the

most significantly enriched pathways were primarily associated with

oxidative stress and inflammatory responses.. GO analysis suggested

that the BP term ‘positive regulation of cell death’ is also

important. Macrophages are important inflammatory response cells

and there is increasing evidence suggesting that macrophages are

involved in the pathogenesis of ARDS. Activated macrophages

exacerbate pulmonary edema in LPS-induced ARDS through excessive

production of pro-inflammatory mediators (43). Particularly, hyperactivation of the

NLRP3 inflammasome has been shown to amplify lung inflammation and

tissue injury (44).

Mechanistically, NLRP3 inflammasome activation triggers

CASP1-dependent cleavage of GSDMD, leading to the release of IL-1β

and IL-18, which ultimately drives pyroptotic cell death. Despite

these advances, the specific involvement of NLRP3

inflammasome-mediated macrophage pyroptosis in ARDS progression

remains poorly characterized, highlighting a key gap in

understanding the pathophysiology of ARDS.

In vitro experiments using LPS/ATP-stimulated

MH-S macrophages demonstrated characteristic pyroptotic changes,

including notable elevation of pyroptosis-related markers (NLRP3,

ASC, CASP1 and GSDMD) at both the protein and mRNA levels,

increased cell death indicators and the release of mature

inflammatory cytokines (IL-18 and IL-1β) into culture supernatants.

Notably, CA was revealed to prevent the changes observed in the

aforementioned indicators. These in vitro findings were

corroborated in vivo using a mouse model of ARDS. CA

administration reduced pulmonary expression of NLRP3 inflammasome

components, alveolar damage markers (LDH release), and BALF

concentrations of IL-18 and IL-1β. Collectively, these findings

suggested airway macrophage pyroptosis as a promising therapeutic

target for ARDS intervention, with CA representing a potential

NLRP3-targeted therapeutic candidate that warrants further clinical

investigation.

Emerging evidence has highlighted a key regulatory

relationship between Nrf2 activation and NLRP3 inflammasome

suppression across various cell types (45-47).

Notably, Nrf2 has been shown to negatively regulate NLRP3

inflammasome activation in primary microglia, attenuating

neuroinflammatory responses (48,49),

while in cardiomyocytes, Nrf2 similarly modulates ROS-induced NLRP3

activation. To the best of our knowledge, the Nrf-NLRP3 regulatory

axis had not been investigated in MH-S cells prior to the present

study. The findings of the present study demonstrated that CA

simultaneously activated Nrf2 signaling and inhibited NLRP3

inflammasome-mediated pyroptosis in MH-S cells. Through

pharmacological inhibition using ML385, a potentially causal

relationship was established whereby the Nrf2 blockade abrogated

the suppressive effects of CA on NLRP3 activation. These results

suggested that CA may exert its protective effects against ARDS

through Nrf2-dependent suppression of NLRP3-mediated pyroptosis in

alveolar macrophages, revealing a novel therapeutic mechanism for

this phytochemical compound.

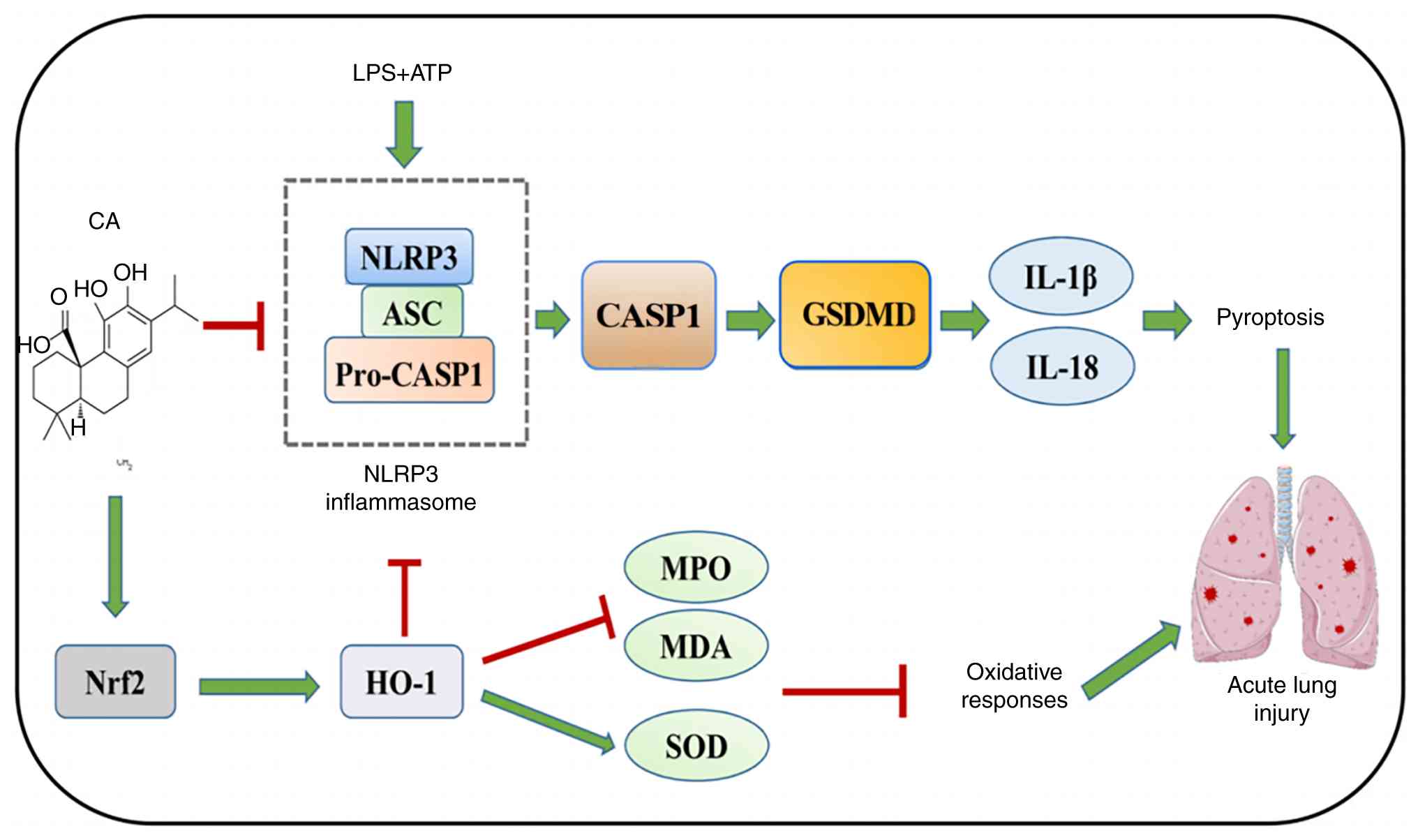

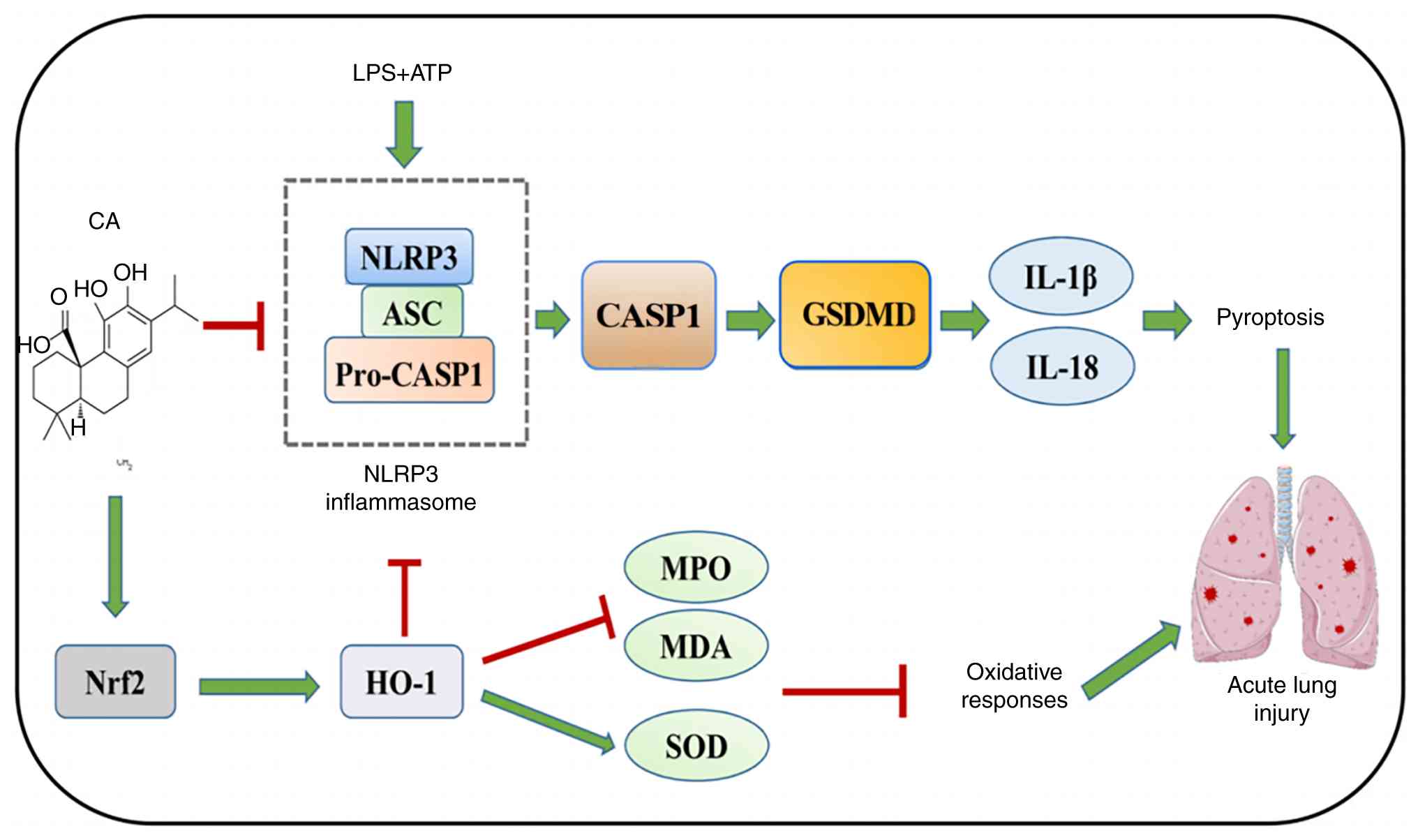

In conclusion, the present study established that CA

exerts potent protective effects against ARDS through a novel

dual-mechanism action, activating the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway to

alleviate oxidative stress, and inhibiting NLRP3

inflammasome-mediated pyroptosis by blocking CASP1 activation and

GSDMD cleavage (Fig. 8). The

findings suggested that CA may simultaneously target these two key

pathways in MH-S cells, revealing an important Nrf2-NLRP3

regulatory axis in the pathogenesis of ARDS. While the therapeutic

potential of CA was established through in vitro and in

vivo validation, further research is necessary to evaluate

dose-response relationships, long-term safety profiles, optimal

delivery methods and potential drug interactions before clinical

translation. The present study not only advances general

understanding of ARDS pathophysiology but also provides a

foundation for developing plant-derived multi-target therapies for

inflammatory lung diseases.

| Figure 8CA protects against acute respiratory

distress syndrome by targeting Nrf2, suppressing oxidative stress

and pyroptosis. LPS activates the NLRP3/CASP1/GSDMD signaling

pathway to induce pyroptosis. CA inhibits oxidative stress and

pyroptosis by activating Nrf2 to reduce lung injury. CA, carnosic

acid; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; NLRP3, NLR family pyrin domain

containing 3; ASC, apoptosis-associated speck-like protein

containing a CARD; CASP1, caspase-1; HO-1, heme oxygenase-1, MPO,

myeloperoxidase; MDA, malondialdehyde; SOD, superoxide dismutase;

GSDMD, gasdermin D; Nrf2, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor

2. |

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: This work was financially supported by the Suqian

Science&Tech Program (grant no. KY202209), the General Project

of Science and Technology Development Fund of Nanjing Medical

University (grant no. NMUB20210295) and the Suqian City Traditional

Chinese Medicine Science and Technology Project (grant no.

YB202212).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

QL contributed to writing the original draft,

project administration, methodology, investigation, funding

acquisition, formal analysis and data curation. LD contributed to

the software used, formal analysis, data curation and

visualization. HS contributed to data curation, formal analysis,

methodology and writing the original draft. WD contributed to the

methodology, data curation, formal analysis and investigation. MW

contributed to project administration and data curation. ZS

contributed to the study conception and design, data

interpretation, and critically revised the manuscript for important

intellectual content. CM contributed to the acquisition of funding,

project administration, data analysis and interpretation, and

critically revised the manuscript. QL and CM confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors have read and

approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All experimental procedures involving animals were

conducted in strict adherence to the Guide for the Care and Use of

Laboratory Animals. Furthermore, the present study protocol was

approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Jinling Hospital,

Medical School of Nanjing University (approval no.

2022DZGKJDWLS-00161).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Gorman EA, O'Kane CM and McAuley DF: Acute

respiratory distress syndrome in adults: diagnosis, outcomes,

long-term sequelae, and management. Lancet. 400:1157–1170.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Wick KD, Ware LB and Matthay MA: Acute

respiratory distress syndrome. BMJ. 387(e76612)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Matthay MA, Arabi Y, Arroliga AC, Bernard

G, Bersten AD, Brochard LJ, Calfee CS, Combes A, Daniel BM,

Ferguson ND, et al: A new global definition of acute respiratory

distress syndrome. Am J Resp Crit Care. 209:37–47. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

He YQ, Zhou CC, Yu LY, Wang L, Deng JL,

Tao YL, Zhang F and Chen WS: Natural product derived phytochemicals

in managing acute lung injury by multiple mechanisms. Pharmacol

Res. 163(105224)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Farhadi F, Baradaran Rahimi V, Mohamadi N

and Askari VR: Effects of rosmarinic acid, carnosic acid, rosmanol,

carnosol, and ursolic acid on the pathogenesis of respiratory

diseases. Biofactors. 49:478–501. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

McCord JM, Hybertson BM, Cota-Gomez A and

Gao B: Nrf2 activator PB125® as a carnosic acid-based therapeutic

agent against respiratory viral diseases, including COVID-19. Free

Radical Bio Med. 175:56–64. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Zhang D, Lee B, Nutter A, Song P,

Dolatabadi N, Parker J, Sanz-Blasco S, Newmeyer T, Ambasudhan R,

McKercher SR, et al: Protection from cyanide-induced brain injury

by the Nrf2 transcriptional activator carnosic acid. J Neurochem.

133:898–908. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Zhang C, Zhao M, Wang B, Su Z, Guo B, Qin

L, Zhang W and Zheng R: The Nrf2-NLRP3-caspase-1 axis mediates the

neuroprotective effects of Celastrol in Parkinson's disease. Redox

Biol. 47(102134)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Arioz BI, Tastan B, Tarakcioglu E, Tufekci

KU, Olcum M, Ersoy N, Bagriyanik A, Genc K and Genc S: Melatonin

attenuates LPS-Induced acute depressive-like behaviors and

microglial NLRP3 inflammasome activation through the SIRT1/Nrf2

pathway. Front Immunol. 10(1511)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Xu L, Zhu Y, Li C, Wang Q, Ma L, Wang J

and Zhang S: Small extracellular vesicles derived from

Nrf2-overexpressing human amniotic mesenchymal stem cells protect

against lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury by inhibiting

NLRP3. Biol Direct. 17(35)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Dhar R, Rana MN, Zhang L, Li Y, Li N, Hu

Z, Yan C, Wang X, Zheng X, Liu H, et al: Phosphodiesterase 4B is

required for NLRP3 inflammasome activation by positive feedback

with Nrf2 in the early phase of LPS-induced acute lung injury. Free

Radical Bio Med. 176:378–391. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Zhou Y, Zhou B, Pache L, Chang M,

Khodabakhshi AH, Tanaseichuk O, Benner C and Chanda SK: Metascape

provides a biologist-oriented resource for the analysis of

systems-level datasets. Nat Commun. 10(1523)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Gene Ontology Consortium. Gene Ontology

Consortium: Going forward. Nucleic Acids Res. 43(Database

issue):D1049–D1056. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Kanehisa M and Goto S: KEGG: Kyoto

encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:27–30.

2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, Baliga NS,

Wang JT, Ramage D, Amin N, Schwikowski B and Ideker T: Cytoscape: A

software environment for integrated models of biomolecular

interaction networks. Genome Res. 13:2498–2504. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Paggi JM, Pandit A and Dror RO: The art

and science of molecular docking. Annu Rev Biochem. 93:389–410.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Kaiyun T, Xiaotong X, Min L, Yongrong W,

Xuyi T, Fu S, Jinwen G and Gaoyan K: Jiawei duhuo jisheng mixture

mitigates osteoarthritis progression in rabbits by inhibiting

inflammation: A network pharmacology and experimental approach.

Comb Chem High Throughput Screen. 28:2107–2131. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Ding Z, Lu Y, Zhao J, Zhang D and Gao B:

Network pharmacology and molecular dynamics identified potential

androgen receptor-targeted metabolites in crocus alatavicus. Int J

Mol Sci. 26(3533)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Kumari R and Kumar R: Open Source Drug

Discovery Consortium. Lynn A: g_mmpbsa-a GROMACS tool for

high-throughput MM-PBSA calculations. J Chem Inf Model.

54:1951–1962. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Xuan W, Wu X, Zheng L, Jia H, Zhang X,

Zhang X and Cao B: Gut microbiota-derived acetic acids promoted

sepsis-induced acute respiratory distress syndrome by delaying

neutrophil apoptosis through FABP4. Cell Mol Life Sci.

81(438)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Huang X, Zhu W, Zhang H, Qiu S and Shao H:

SARS-CoV-2 N protein induces alveolar epithelial apoptosis via

NLRP3 pathway in ARDS. Int Immunopharmacol.

144(113503)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Jeong EJ, Choi JJ, Lee SY and Kim YS: The

effects of ML385 on head and neck squamous cell carcinoma:

implications for NRF2 inhibition as a therapeutic strategy. Int J

Mol Sci. 25(7011)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Chen J, Ding W, Zhang Z, Li Q, Wang M,

Feng J, Zhang W, Cao L, Ji X, Nie S and Sun Z: Shenfu injection

targets the PI3K-AKT pathway to regulate autophagy and apoptosis in

acute respiratory distress syndrome caused by sepsis.

Phytomedicine. 129(155627)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

McGinn R, Fergusson DA, Stewart DJ,

Kristof AS, Barron CC, Thebaud B, McIntyre L, Stacey D, Liepmann M,

Dodelet-Devillers A, et al: Surrogate humane endpoints in small

animal models of acute lung injury: A modified delphi consensus

study of researchers and laboratory animal veterinarians. Crit Care

Med. 49:311–323. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Zingarelli B: First do no harm: A proposal

of an expert-guided framework of surrogate humane endpoints in

preclinical models of acute lung injury. Crit Care Med. 49:373–375.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Kang JY, Xu MM, Sun Y, Ding ZX, Wei YY,

Zhang DW, Wang YG, Shen JL, Wu HM and Fei GH: Melatonin attenuates

LPS-induced pyroptosis in acute lung injury by inhibiting

NLRP3-GSDMD pathway via activating Nrf2/HO-1 signaling axis. INT

Immunopharmacol. 109(108782)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 25:402–408.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Bahri S, Jameleddine S and Shlyonsky V:

Relevance of carnosic acid to the treatment of several health

disorders: Molecular targets and mechanisms. Biomed Pharmacother.

84:569–582. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

He F, Ru X and Wen T: NRF2, a

transcription factor for stress response and beyond. Int J Mol Sci.

21(4777)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Pinela J, Dias MI, Pereira C and

Alonso-Esteban JI: Antioxidant activity of foods and natural

products. Molecules. 29(1814)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Cardoso SM and Fassio A: The antioxidant

capacities of natural products 2019. Molecules.

25(5676)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Qiu Y, Chen S, Yu M, Shi J, Liu J, Li X,

Chen J, Sun X, Huang G and Zheng C: Natural products from

marine-derived fungi with anti-inflammatory activity. Mar Drugs.

22(433)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Moudgil KD and Venkatesha SH: The

anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory activities of natural

products to control autoimmune inflammation. Int J Mol Sci.

24(95)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Heard SC, Wu G and Winter JM: Antifungal

natural products. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 69:232–241. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Lewis K, Lee RE, Brötz-Oesterhelt H,

Hiller S, Rodnina MV, Schneider T, Weingarth M and Wohlgemuth I:

Sophisticated natural products as antibiotics. Nature. 632:39–49.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Amaral-Machado L, Oliveira WN, Rodrigues

VM, Albuquerque NA, Alencar ÉN and Egito EST: Could natural

products modulate early inflammatory responses, preventing acute

respiratory distress syndrome in COVID-19-confirmed patients?

Biomed Pharmacother. 134(111143)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Maione F, Cantone V, Pace S, Chini MG,

Bisio A, Romussi G, Pieretti S, Werz O, Koeberle A, Mascolo N and

Bifulco G: Anti-inflammatory and analgesic activity of carnosol and

carnosic acid in vivo and in vitro and in silico analysis of their

target interactions. Br J Pharmacol. 174:1497–1508. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Albadrani GM, Altyar AE, Kensara OA,

Haridy MAM, Zaazouee MS, Elshanbary AA, Sayed AA and Abdel-Daim MM:

Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-DNA damage effects of

carnosic acid against aflatoxin B1-induced hepatic, renal, and

cardiac toxicities in rats. Toxicol Res (Camb).

13(tfae083)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Dhlamini Q, Wang W, Feng G, Chen A, Chong

L, Li X, Li Q, Wu J, Zhou D, Wang J, et al: FGF1 alleviates

LPS-induced acute lung injury via suppression of inflammation and

oxidative stress. Mol Med. 28(73)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Gong L, Shen Y, Wang S, Wang X, Ji H, Wu

X, Hu L and Zhu L: Nuclear SPHK2/S1P induces oxidative stress and

NLRP3 inflammasome activation via promoting p53 acetylation in

lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury. Cell Death Discov.

9(12)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Zhu YS, Shah SAA, Yang BY, Fan SS, He L,

Sun YR, Shang WB, Qian Y and Zhang X: Gen-17, a beta-methyl

derivative of Genipin, attenuates LPS-induced ALI by regulating

Keap1-Nrf2/HO-1 and suppressing NF-κB and MAPK-dependent signaling

pathways. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis.

1871(167770)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Huang J, Zhu Y, Li S, Jiang H, Chen N,

Xiao H, Liu J, Liang D, Zheng Q, Tang J and Meng X: Licochalcone B

confers protective effects against LPS-Induced acute lung injury in

cells and mice through the Keap1/Nrf2 pathway. Redox Rep.

28(2243423)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Song Y, Gou Y, Gao J, Chen D, Zhang H,

Zhao W, Qian F, Xu A and Shen Y: Lomerizine attenuates LPS-induced

acute lung injury by inhibiting the macrophage activation through

reducing Ca(2+) influx. Front Pharmacol. 14(1236469)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Sayson SG, Ashbaugh A, Porollo A, Smulian

G and Cushion MT: Pneumocystis murina promotes inflammasome

formation and NETosis during Pneumocystis pneumonia. mBio.

15(e140924)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Che J, Wang H, Dong J, Wu Y, Zhang H, Fu L

and Zhang J: Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell-derived

exosomes attenuate neuroinflammation and oxidative stress through

the NRF2/NF-κB/NLRP3 pathway. CNS Neurosci Ther.

30(e14454)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Rajan S, Tryphena KP, Khan S, Vora L,

Srivastava S, Singh SB and Khatri DK: Understanding the involvement

of innate immunity and the Nrf2-NLRP3 axis on mitochondrial health

in Parkinson's disease. Ageing Res Rev. 87(101915)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Sun YY, Zhu HJ, Zhao RY, Zhou SY, Wang MQ,

Yang Y and Guo ZN: Remote ischemic conditioning attenuates

oxidative stress and inflammation via the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway in MCAO

mice. Redox Biol. 66(102852)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Han QQ and Le W: NLRP3

inflammasome-mediated neuroinflammation and related mitochondrial

impairment in Parkinson's disease. Neurosci Bull. 39:832–844.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Qiu WQ, Ai W, Zhu FD, Zhang Y, Guo MS, Law