Mental health, recognized as a fundamental human

right, holds critical importance globally. However, mental illness

is escalating worldwide (1). Major

mental disorders, such as depressive disorders, anxiety disorders,

bipolar disorder, schizophrenia and autism spectrum disorders,

contribute significantly to this burden. The Global Burden of

Diseases, Injuries and Risk Factors Study (GBD) 2019 highlights a

substantial increase in the burden of non-communicable diseases,

including mental health conditions, over the past three decades

(1990-2019) (2,3). While diagnostic rates of mental

disorders may appear higher in high-income countries due to better

healthcare infrastructure and reporting, access to effective

treatment and mental health services remains insufficient across

both high- and low-income regions (4).

Schizophrenia, a severe mental disorder with a

global lifetime prevalence of ~0.4%, stands as one of the leading

causes of disability worldwide (5-7).

Numerous affected individuals experience long-term functional

impairment, with significant life-altering consequences such as

social isolation, self-stigmatization and increased difficulty in

forming relationships (8).

Schizophrenia is not characterized by pathognomonic symptoms, but

rather by a constellation of features typically categorized into

positive, negative and cognitive domains (9). Positive symptoms reflect distortions

of normal perception and behavior, including delusions,

hallucinations and disorganized behavior. Negative symptoms involve

diminished emotional expression and motivation, manifesting as

avolition, asociality and affective flattening. Cognitive deficits,

such as impairments in attention, working memory and executive

functioning, are increasingly recognized as core features of the

disorder (10,11). Some researchers argue that

cognitive impairment is the primary determinant of long-term

functional disability in schizophrenia (12). Diagnosing schizophrenia and

evaluating treatment effectiveness remain challenging, primarily

due to the absence of reliable, objective biomarkers (13). This review describes the potential

pathogenesis of schizophrenia from environmental and genetic

factors. Further summarising model studies of schizophrenia, this

work integrates genetic, environmental and modelling perspectives

to advance the understanding of the disorder from both holistic and

cellular-molecular viewpoints. This approach yields significant

benefits for research into characteristic biomarkers,

pathophysiology and aetiological mechanisms.

This is a narrative review aiming to summarise

current research on the influence of genetic and environmental

factors on schizophrenia, alongside studies concerning research

models for schizophrenia. The primary themes are the pathogenesis

of schizophrenia (genetic and environmental factors) and model

studies (animal and cellular models). References were retrieved

from the PubMed database {using the following search string:

{[(schizophrenia) OR (psychosis)] AND [(pathogenesis) OR

(mechanism) OR (gene) OR (environment); (schizophrenia) OR

(psychosis)] AND [(model) OR (modeling) OR (animal model) OR (cell

model)]}, encompassing reviews, randomised controlled trials,

meta-analyses and experimental research data from the past decade.

Based on this review, we have screened articles exploring the

pathogenesis of schizophrenia from both genetic and environmental

perspectives, as well as disease research methodologies utilising

animal and cellular models. Studies incorporating schizophrenia

diagnoses will be included. Research primarily consisting of review

reports will be excluded. Model studies failing to explicitly state

that relevant ethical approvals were obtained will be excluded.

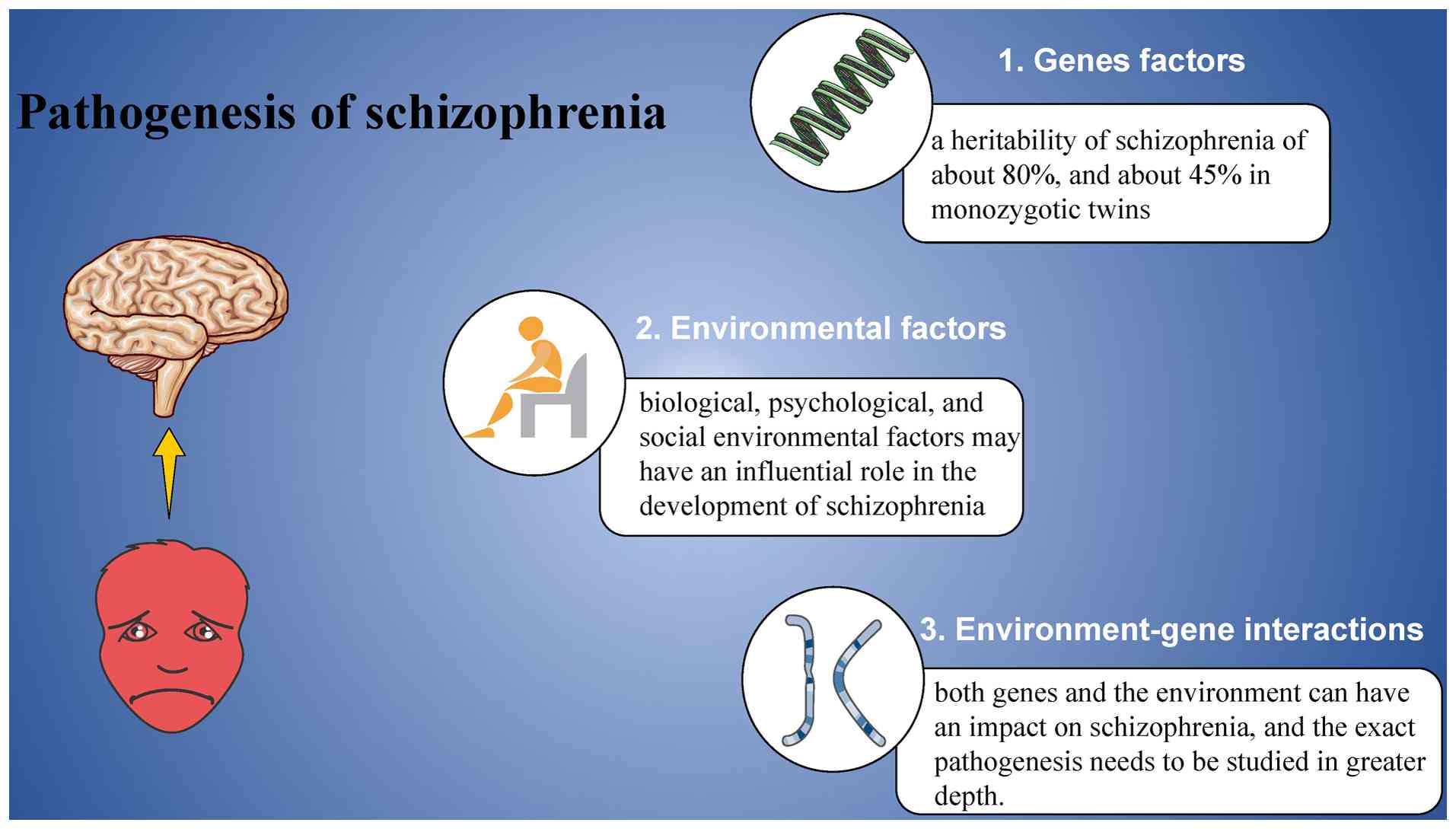

The precise pathogenesis of schizophrenia remains to

be fully elucidated. However, it is generally accepted that

genetic, environmental and immunological factors are key

contributors to the disorder (14,15).

The causes of schizophrenia are multifactorial, typically arising

from the complex interplay of these factors (Fig. 1) (16).

Genetic factors play a significant role in

schizophrenia's etiology, with heritability estimates of ~80 and

~45% for monozygotic twins (17).

Following the completion of the human genome sequencing in 2003,

genetic research has expanded considerably (18). Approximately 70-80% of human genes

are expressed in the brain, and numerous genes involved in synaptic

transmission have been linked to psychiatric disorders (19). Schizophrenia exhibits familial

aggregation, and studies involving adoption and twins suggest that

genetic factors outweigh environmental influences (20,21).

The 22q11.2 gene deletion was one of the first variants identified

in relation to schizophrenia, but no single genetic mutation has

been conclusively tied to the disorder (22,23).

Individuals with a deletion in the glutathione S-transferase theta

1 gene within the 22q11.2 region exhibit an increased risk of

developing schizophrenia (24). A

genetic study encompassing 36,989 patients with schizophrenia and

113,075 controls revealed 108 independent loci strongly associated

with the disorder. These include the gene encoding dopamine D2

receptor, the primary target of nearly all antipsychotic drugs, as

well as genes involved in glutamatergic signaling and synaptic

plasticity, such as glutamate ionotropic receptor

α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid type subunit

1, glutamate ionotropic receptor noncompetitive malondialdehyde

type subunit 2A and serine racemase, providing genetic support for

existing hypotheses that implicate both dopaminergic and

glutamatergic systems in schizophrenia (25-27).

A separate study of 5,220 patients with schizophrenia and 18,823

controls identified 145 independent gene loci linked to the

disorder (28). These risk

variants primarily cluster in neuronal and synaptic gene sets, and

ongoing research with larger sample sizes continues to enhance the

understanding of schizophrenia's genetic underpinnings (29). Certain researchers proposed that

common genetic variants account for 30-50% of schizophrenia's

genetic liability, but the risk posed by any individual variant is

limited (30).

Notably, several studies have identified new

mutations clustered in loss-of-function genes in individuals with

childhood-onset schizophrenia (31). These studies highlight that many of

the mutations affect genes linked to neurodevelopmental disorders,

including ATPase Na+/K+ transporting subunit alpha 3, Up-frameshift

suppressor 3B, snf2 related CREBBP activator protein and

polynucleotide kinase 3'-phosphatase (32-34).

Further research has underscored the role of

epigenetic modifications in schizophrenia (35). Epigenetic processes, including

histone modification, DNA methylation, chromatin remodeling and

non-coding RNA expression, contribute to the regulation of gene

expression. Guidotti et al (36) suggested that targeting the link

between reduced Reelin expression in patients with schizophrenia

and epigenetic dysregulation may offer a more promising therapeutic

approach. A large-scale study by Jaffe et al (37) identified 2,104 methylated CpG sites

in the forebrain cortex of schizophrenia cases, which differed

significantly from controls. Additionally, histone deacetylase

(HDAC) inhibitors have shown potential for improving clinical

symptoms of schizophrenia (38).

Evidence from brain samples of patients with schizophrenia

indicates altered epigenetic markers, including elevated H3R17

methylation levels (39),

increased cortical HDAC1 expression (40) and reduced cortical HDAC2 levels

(41).

Environmental factors, once overlooked, are now

widely acknowledged as significant contributors to the development

of schizophrenia. It is increasingly recognized that a combination

of biological, psychological and social environmental influences

may play a critical role in the onset and progression of the

disorder, as summarized in Table I

(42-53).

Environmental factors (such as prenatal infections,

childhood trauma and adolescent cannabis use) can shape

schizophrenia risk across critical developmental windows, from

early gestation to young adulthood, impacting both individuals and

populations. These factors may play a more significant role in the

onset of schizophrenia than common genetic variants identified in

global genomic studies (54).

Schizophrenia's origins may be rooted in

neurodevelopmental disruptions during the fetal stage. Research has

shown that maternal exposure to infections or stress during

pregnancy can increase the likelihood of schizophrenia in offspring

(55-57).

Early investigations into psychiatric disorders following in-utero

infections primarily focused on schizophrenia (58). A significant amount of research has

examined the effects of Toxoplasma gondii infection, though

the exact mechanism by which it contributes to schizophrenia

remains elusive. Toxoplasma gondii, a unicellular eukaryote

primarily hosted by felines but capable of infecting any

warm-blooded animal, has been associated with behavioral

alterations in humans (59). In

healthy individuals, Toxoplasma gondii infection typically

shows no overt clinical symptoms, but during pregnancy, it can be

transmitted to the fetus via the placenta (60). Serological studies have revealed

significantly higher serum levels of anti-Toxoplasma IgG and

IgM in patients with schizophrenia compared to healthy controls

(61-63).

Current research indicates that Toxoplasma infection may

disrupt central nervous system neurotransmitter regulation, the

blood-brain barrier, immune stress responses and inflammatory

reactions, factors closely associated with schizophrenia

pathogenesis (64,65).

Childhood adversity is also known as childhood

trauma, such as abuse, domestic violence and neglect (66). Individuals with schizophrenia who

have experienced such adversity may exhibit earlier cognitive

deficits, possibly due to neurodevelopmental impairments (67). There is substantial evidence

linking childhood maltreatment to more severe psychotic symptoms,

with those affected being more than four times as likely to develop

a psychotic disorder following trauma (68,69).

Additionally, such adversity is strongly associated with positive

symptoms of schizophrenia, such as hallucinations and delusions

(70).

Several studies have also highlighted the influence

of the social environment on the onset of schizophrenia. Factors

such as social adversity, discrimination, poverty and substance

use-especially cannabis-have all been identified as potential

contributors to schizophrenia development (71-75).

As research has advanced, it has become increasingly

evident that schizophrenia is a multifactorial disorder, prompting

more studies focused on the interaction between genetic and

environmental factors in its development. Epidemiological studies

have established a clear link between infection and schizophrenia

(76). Among the infectious

agents, Toxoplasma gondii has been the most extensively

studied, with substantial evidence supporting its association with

schizophrenia. A meta-analysis by Wang et al (77) revealed that

schizophrenia-associated genes were notably enriched in the

Toxoplasma gondii IgG seropositive population, suggesting

that Toxoplasma infection may influence the expression of

genes related to schizophrenia. However, a more recent study by

Lori et al (78) indicated

that signs of Toxoplasma infection do not serve as reliable

predictors of schizophrenia. As previously noted, Toxoplasma

gondii infection exerts a significant influence on

schizophrenia by affecting associated genetic loci. Additional

studies have indicated that inflammatory environments and stress

responses within the central nervous system may contribute to

psychiatric disorders, including schizophrenia, by affecting the

hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (79), with anti-inflammatory medications

showing promise in alleviating certain schizophrenia symptoms

(80). In the context of

environment-gene interactions in schizophrenia, neuroinflammation

driven by infectious agents has been recognized as a potential

mechanism. Elevated peripheral inflammatory markers, such as

C-reactive protein, have been observed in patients with

schizophrenia (81). Furthermore,

high levels of immune antibodies in infected mothers have been

suggested as potential causes of neuropathological changes

(82). Neuropathological

alterations in offspring resulting from maternal infection with

infectious viruses such as influenza and measles may increase the

incidence rate by 1-20% (83).

Cannabis use interacts with genetic factors in the

pathogenesis of schizophrenia (84). Further studies suggest that

individuals with a genetic predisposition may be more susceptible

to developing schizophrenia as a result of cannabis use (85). Cannabis use may influence the

development of schizophrenia by affecting specific genetic loci,

potentially alleviating symptoms of central nervous system

disorders (86). A study on the

catechol-o-methyltransferase (COMT) Val158Met polymorphism revealed

that the COMT Val158Met Val allele is associated with an increased

risk of psychosis following cannabis use (87). In a further study, Met allele

homozygotes for the COMT Val158Met polymorphism were more sensitive

to stress and exhibited a neurotic tendency in response to daily

stressors (88). Additionally,

research on specific alleles of the Protein Kinase B and fatty acid

amide hydrolase genes has demonstrated that cannabis users with

certain genetic variations are more susceptible to showing

psychotic symptoms (89). However,

the relationship between cannabis use and schizophrenia is complex

and somewhat controversial. Cannabis is known to alleviate stress

symptoms and individuals who have experienced high levels of stress

or depression may be more inclined to use it (90). This highlights the intricate nature

of the link between cannabis use and schizophrenia, further

reinforcing the understanding that schizophrenia is a

multifactorial mental illness.

Extensive evidence indicates that both genetic and

environmental factors contribute to schizophrenia, although the

exact pathogenesis remains elusive. More comprehensive studies

exploring the interaction between genes and the environment could

offer valuable insights into the causes, pathology and potential

treatment options for schizophrenia.

Constructing an appropriate model is a powerful

approach to understanding how a disease affects an organism. The

schizophrenia model, described here from both an animal and

cellular perspective, provides a key example.

The unique complexity of the human brain in both

function and structure poses challenges for schizophrenia research.

Studies of the living patient's brain primarily rely on

neuroimaging and cognitive testing, while direct analysis of brain

tissue is restricted to post-mortem investigations. Factors such as

ongoing environmental stress, genetic influences and drug effects

in patients complicate research, necessitating the development of

reliable animal models. An effective model should encompass three

core characteristics: Face validity, construct validity and

predictive validity (91). Face

validity requires that the model replicates the symptoms of

schizophrenia, while construct validity ensures the model mimics

the structural and functional abnormalities observed in the

disease. Predictive validity ensures that therapeutic interventions

can reverse the disease-like phenotype. Animal models, including

both invertebrates and vertebrates, such as non-human primates,

offer valuable tools for investigating the mechanisms underlying

schizophrenia risk. The MATRICS program, developed by the National

Institute of Mental Health, identified seven domains relevant to

schizophrenia and proposed corresponding rodent-based assays

(92).

Established high-risk factors, such as maternal

infections and early neurodevelopmental disorders, play a critical

role in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. Animal models

addressing these factors often involve perinatal and/or early

postnatal environmental manipulation, or the administration of

medications, followed by longitudinal studies of offspring

development. One of the earliest approaches to modeling

schizophrenia in animals involved inducing ventral hippocampal

lesions in rats through localized toxin injections on postnatal day

7. Another widely used model is the administration of

methylazomethanol (MAM) to pregnant rats (93), which induces neuroanatomical,

electrophysiological and behavioral alterations in offspring, with

the timing of MAM exposure-particularly on gestational day 17-being

a critical determinant of model fidelity (94).

Inducing maternal immune activation (MIA) in

pregnant rodents is another widely used strategy for constructing

schizophrenia models. Strong evidence suggests that rodents and

primates subjected to MIA during gestation produce offspring

exhibiting anatomical, neurochemical, electrophysiological and

behavioral alterations consistent with schizophrenia (95). Using this model, Steullet et

al (96) demonstrated that

changes in parasympathetic interneurons and their associated

perineuronal networks (extracellular matrix structures critical for

structural and synaptic plasticity) in the prefrontal cortex and

hippocampal formation were linked to cognitive deficits, findings

aligning with autopsy reports from patients with schizophrenia

(97).

The most commonly utilized pharmacological agents in

animal models of schizophrenia are dopamine enhancers and

noncompetitive malondialdehyde (NMDA) receptor antagonists.

Amphetamine, a dopamine-enhancing agent known to induce psychosis

in humans, does not cause social impairment in rodents with

continuous administration, although it does affect certain

forebrain-associated cognitive functions (98). Studies have shown that amphetamine

impairs cholinergic basal neurons in rat cerebral cortical

projections, suggesting that dysregulation of this activity is

related to attentional dysfunction (99-101).

Wearne et al (102)

identified 96 differentially expressed proteins in the prefrontal

cortex of methamphetamine-treated rats, with 20% linked to

schizophrenia pathogenesis. Additionally, certain dopamine

enhancers are known to elevate tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) and

MDA, signaling increased inflammation and oxidative stress

(103). NMDA receptor antagonists

are often used in rodents to simulate the hypofunction of NMDA

glutamate receptors observed in patients with schizophrenia

(104). The NMDA receptor

antagonist pentachlorophenol (PCP) induces hallucinations,

delusions, speech impoverishment and cognitive deficits in humans,

while in rodents, PCP causes social withdrawal and cognitive

impairments.

Advances in human genome-wide studies have recently

revealed a growing list of schizophrenia-associated and candidate

genes (105), emphasizing the

importance of genetic factors in the development of animal models.

The identification of these candidate genes has significantly

contributed to refining and enhancing schizophrenia model systems

(106,107). Certainly, animal models used in

modern research must obtain approval from the Animal Research

Ethics Committee and comply with the animal experiment guidelines

or directives formulated by relevant institutions.

In the post-genome-wide era of schizophrenia, the

development of cellular models incorporating

schizophrenia-associated variants has become a crucial tool for

understanding the disease. Both autopsy and in vivo

neuroimaging studies have highlighted neuronal and glial cell

abnormalities as prominent features of schizophrenia.

Artificially manipulating SH-SY5Y cells to construct

cellular models greatly benefits research into schizophrenia at the

cellular and molecular levels. SH-SY5Y cells treated with the NMDA

antagonist MK-801 are commonly used to model neuronal damage seen

in patients with schizophrenia. MK-801 downregulates the sirtuin

1/microRNA (miRNA)-134 signaling pathway and Ca2+

influx, replicating dysfunction in the prefrontal cortex (112). Additionally, SH-SY5Y cells are

utilized to investigate the molecular mechanisms underlying reduced

neurite spines, a known susceptibility factor for schizophrenia

that is also observed in postmortem brain samples from patients

(113). Lentiviral infection of

SH-SY5Y cells with short hairpin RNA targeting the schizophrenia

susceptibility gene DISC1 results in mitochondrial fragmentation

and respiratory defects. Studies on DISC1 in SH-SY5Y cells suggest

that DISC1-depleted cells fail to maintain proper mitochondrial

oxidative phosphorylation complex function, and mitochondrial

abnormalities may have a role in the onset of schizophrenia

(114). SHANK2, a gene encoding a

protein essential for the formation and development of

glutamatergic synapses, has also been implicated in schizophrenia

pathogenesis (115). Mutations in

SHANK2 in SH-SY5Y cells impair early neuronal differentiation,

alter cell growth properties and reduce both pre- and post-synaptic

protein expression (116).

Collectively, these studies strongly support the use of SH-SY5Y

cells as a reliable model for investigating schizophrenia.

Additionally, SH-SY5Y cells have proven valuable as a screening

platform for potential antipsychotic drugs (117).

Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) were

initially utilized to model diseases linked to highly penetrant

genetic variants with significant phenotypic effects, and more

recently, iPSC-derived neurons have been employed to construct

models of psychiatric disorders. Although iPSCs are not commonly

used to model schizophrenia-related processes directly, genetic

variants associated with schizophrenia can substantially affect

iPSCs. For instance, the 22q11.2 deletion has been shown to reduce

the proliferation rate of iPSCs in culture (118). Furthermore, the study of

patient-derived iPSCs enables the screening of genetic variants

that may not be detectable through human genome-wide studies, while

also shedding light on the roles of relevant candidate variants.

Although the reproducibility of iPSC models remains a subject of

debate, careful selection of iPSC lines for reprogramming, as well

as thoughtful consideration of subjects and controls, can mitigate

many of their limitations (119).

iPSC-derived neurons mainly include neural

progenitor cells (NPCs), glutamatergic neurons, dopaminergic

(DAergic) neurons and γ-aminobutyric acid-secreting (GABAergic)

neurons. Studies involving NPCs have broadened the understanding of

schizophrenia, highlighting its complexity as a neurodevelopmental

disorder. The glutamatergic neurons model is based on the

glutamatergic hypothesis, where SNP-4bp mutations in DISC1 in

glutamatergic neurons result in reduced presynaptic labeling and

defective neurotransmitter release. Notably, the mutant phenotype

can be reversed by restoring the DISC1 sequence, thereby

demonstrating how synaptic defects contribute to schizophrenia

(120). The DAergic neurons model

is linked to the dopaminergic dysfunction hypothesis, which remains

central to schizophrenia research, supported by both animal models

and human studies (121). The

iPSC-derived DAergic neurons model helps elucidate the molecular

mechanisms underlying the relationship between genetic variants and

dopaminergic dysfunction in patients with schizophrenia. While most

studies on iPSC-derived GABAergic neurons have focused on

Huntington's disease, research has indicated the downregulation of

key GABA pathway genes in GABAergic neurons derived from patients

with schizophrenia, suggesting there is still significant room for

further exploration of GABAergic neurons in schizophrenia (122).

Non-neuronal cells can be reprogrammed into neuronal

cells or used directly as cell models. It has been demonstrated

that fibroblasts can be directly converted into patient-specific

inducible neurons, such as glutamatergic and GABAergic neurons,

through transcription factor overexpression and the addition of

miRNAs (123). Non-neuronal

cells, like HEK293 cells, can also serve as models for studying

genes and proteins associated with schizophrenia. The

primate-specific mutant isoform Kv11.1-3.1 of the brain

voltage-gated potassium channel exhibits aberrant folding and

impaired migration to the plasma membrane, which correlates with

prolonged neuronal action potentials observed in patients with

schizophrenia. Researchers have developed a platform for screening

drugs that restore Kv11.1-3.1 function using HEK293 cells (124). Studies on the DPYSL2 isoform in

HEK293 cells have shown that alterations in risk alleles can lead

to changes in cellular morphology, affecting synaptic transmission

and correlating with schizophrenia susceptibility (125,126).

However, current research on schizophrenia largely

focuses on relatively narrow perspectives and the symptoms of

schizophrenia exhibit significant individual variation. Such

individual variations pose significant challenges to the

establishment of disease models and the conduct of more in-depth

research. Furthermore, differing hypotheses exist regarding the

pathogenesis of schizophrenia, and genetic outcomes also vary

across different populations. This review primarily employed broad

keywords in its literature search (such as schizophrenia, mental

illness, model studies, animal models, cellular models,

environment, genes and epigenetics), and consequently may have

overlooked certain publications. Advancing the translation of

findings from animal/cell model research into human pathology

facilitates researchers' deeper understanding of schizophrenia and

aids in drug screening and validation.

The causes of schizophrenia are unknown and include

complex genetic inheritance, the environment and the interaction of

the two. Current findings suggest that schizophrenia involves a

number of different neurotransmitters, including dopamine,

glutamate and serotonin. More research related to schizophrenia

remains to be done, and the construction of more accurate models

will facilitate further exploration of the pathogenesis of

schizophrenia as well as its treatment.

At present, mental disorders pose considerable

challenges both in diagnosis and treatment. Schizophrenia lacks

precise biomarkers or pathological criteria for diagnosis, and

psychiatric disorders frequently co-occur with it, presenting

symptoms that vary significantly among individuals. The current

mainstream medications for treating schizophrenia carry significant

side effects, resulting in a markedly reduced quality of life for

patients. Whether through human genomics research or more complex

and precise biological modelling, the aim is to gain deeper

insights into schizophrenia, uncover its precise mechanisms, and

identify therapeutic drugs with enhanced efficacy and reduced side

effects. In the current state of mental health, research into

mechanisms and therapeutic drug development is of considerable

value and significance.

Not applicable.

Funding: No funding was received.

Not applicable.

SL contributed to the writing and editing of this

review. CL collected the data. Data authentication is not

applicable. All authors have read and approved the final

manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

|

1

|

Patel V, Saxena S, Lund C, Thornicroft G,

Baingana F, Bolton P, Chisholm D, Collins PY, Cooper JL, Eaton J,

et al: The lancet commission on global mental health and

sustainable development. Lancet. 392:1553–1598. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

GBD 2019 Demographics Collaborators.

Global age-sex-specific fertility, mortality, healthy life

expectancy (HALE), and population estimates in 204 countries and

territories, 1950-2019: A comprehensive demographic analysis for

the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 396:1160–1203.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries

Collaborators. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204

countries and territories, 1990-2019: A systematic analysis for the

Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 396:1204–1222.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators.

Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204

countries and territories, 1990-2019: A systematic analysis for the

Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry. 9:137–150.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Khavari B and Cairns MJ: Epigenomic

dysregulation in schizophrenia: In search of disease etiology and

biomarkers. Cells. 9(1837)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

McCutcheon RA, Reis Marques T and Howes

OD: Schizophrenia-an overview. JAMA Psychiatry. 77:201–210.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Saha S, Chant D, Welham J and McGrath J: A

systematic review of the prevalence of schizophrenia. PLoS Med.

2(e141)2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Jauhar S, Johnstone M and McKenna PJ:

Schizophrenia. Lancet. 399:473–486. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Bueno-Antequera J and Munguía-Izquierdo D:

Exercise and Schizophrenia. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1228:317–332.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Correll CU and Schooler NR: Negative

symptoms in schizophrenia: A review and clinical guide for

recognition, assessment, and treatment. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat.

16:519–534. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Faden J and Citrome L: Schizophrenia: One

name, many different manifestations. Med Clin North Am. 107:61–72.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Javitt DC: Cognitive impairment associated

with schizophrenia: From pathophysiology to treatment. Annu Rev

Pharmacol Toxicol. 63:119–141. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Ma H, Cheng N and Zhang C: Schizophrenia

and alarmins. Medicina (Kaunas). 58(694)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Zamanpoor M: Schizophrenia in a genomic

era: A review from the pathogenesis, genetic and environmental

etiology to diagnosis and treatment insights. Psychiatr Genet.

30:1–9. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Chauhan P, Kaur G, Prasad R and Singh H:

Pharmacotherapy of schizophrenia: Immunological aspects and

potential role of immunotherapy. Expert Rev Neurother.

21:1441–1453. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Helaly AMN and Ghorab DSED: Schizophrenia

as metabolic disease. What are the causes? Metab Brain Dis.

38:795–804. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Stilo SA and Murray RM: Non-genetic

factors in schizophrenia. Curr Psychiatry Rep.

21(100)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Collins FS, Morgan M and Patrinos A: The

human genome project: Lessons from large-scale biology. Science.

300:286–290. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Peedicayil J: Genome-environment

interactions and psychiatric disorders. Biomedicines.

11(1209)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Tsuang M: Schizophrenia: Genes and

environment. Biol Psychiatry. 47:210–220. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Kendler KS and Diehl SR: The genetics of

schizophrenia: A current, genetic-epidemiologic perspective.

Schizophr Bull. 19:261–285. 1993.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Wahbeh MH and Avramopoulos D:

Gene-environment interactions in schizophrenia: A literature

review. Genes (Basel). 12(1850)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Takata A, Xu B, Ionita-Laza I, Roos JL,

Gogos JA and Karayiorgou M: Loss-of-function variants in

schizophrenia risk and SETD1A as a candidate susceptibility gene.

Neuron. 82:773–780. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Ansari-Lari M, Zendehboodi Z, Masoudian M

and Mohammadi F: Additive effect of glutathione S-transferase T1

active genotype and infection with Toxoplasma gondii for increasing

the risk of schizophrenia. Nord J Psychiatry. 75:275–280.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Coyle JT: Passing the torch: The

ascendance of the glutamatergic synapse in the pathophysiology of

schizophrenia. Biochem Pharmacol. 228(116376)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Harrison PJ and Bannerman DM: GRIN2A

(NR2A): A gene contributing to glutamatergic involvement in

schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 28:3568–3572. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Zhang CY, Xiao X, Zhang Z, Hu Z and Li M:

An alternative splicing hypothesis for neuropathology of

schizophrenia: evidence from studies on historical candidate genes

and multi-omics data. Mol Psychiatry. 27:95–112. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Pardiñas AF, Holmans P, Pocklington AJ,

Escott-Price V, Ripke S, Carrera N, Legge SE, Bishop S, Cameron D,

Hamshere ML, et al: Common schizophrenia alleles are enriched in

mutation-intolerant genes and in regions under strong background

selection. Nat Genet. 50:381–389. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Forsyth JK and Asarnow RF: Genetics of

childhood-onset schizophrenia 2019 update. Child Adolesc Psychiatr

Clin N Am. 29:157–170. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Schizophrenia Working Group of the

Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. Biological insights from 108

schizophrenia-associated genetic loci. Nature. 511:421–427.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Ambalavanan A, Girard SL, Ahn K, Zhou S,

Dionne-Laporte A, Spiegelman D, Bourassa CV, Gauthier J, Hamdan FF,

Xiong L, et al: De novo variants in sporadic cases of childhood

onset schizophrenia. Eur J Hum Genet. 24:944–948. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Chaumette B, Ferrafiat V, Ambalavanan A,

Goldenberg A, Dionne-Laporte A, Spiegelman D, Dion PA, Gerardin P,

Laurent C, Cohen D, et al: Missense variants in ATP1A3 and FXYD

gene family are associated with childhood-onset schizophrenia. Mol

Psychiatry. 25:821–830. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Smedemark-Margulies N, Brownstein CA,

Vargas S, Tembulkar SK, Towne MC, Shi J, Gonzalez-Cuevas E, Liu KX,

Bilguvar K, Kleiman RJ, et al: A novel de novo mutation in ATP1A3

and childhood-onset schizophrenia. Cold Spring Harb Mol Case Stud.

2(a001008)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Jolly LA, Homan CC, Jacob R, Barry S and

Gecz J: The UPF3B gene, implicated in intellectual disability,

autism, ADHD and childhood onset schizophrenia regulates neural

progenitor cell behaviour and neuronal outgrowth. Hum Mol Genet.

22:4673–4687. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Richetto J and Meyer U: Epigenetic

modifications in schizophrenia and related disorders: Molecular

scars of environmental exposures and source of phenotypic

variability. Biol Psychiatry. 89:215–226. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Guidotti A, Grayson DR and Caruncho HJ:

Epigenetic RELN dysfunction in schizophrenia and related

neuropsychiatric disorders. Front Cell Neurosci.

10(89)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Jaffe AE, Gao Y, Deep-Soboslay A, Tao R,

Hyde TM, Weinberger DR and Kleinman JE: Mapping DNA methylation

across development, genotype and schizophrenia in the human frontal

cortex. Nat Neurosci. 19:40–47. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Sharma RP, Rosen C, Kartan S, Guidotti A,

Costa E, Grayson DR and Chase K: Valproic acid and chromatin

remodeling in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: Preliminary

results from a clinical population. Schizophr Res. 88:227–231.

2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Akbarian S, Ruehl MG, Bliven E, Luiz LA,

Peranelli AC, Baker SP, Roberts RC, Bunney WE Jr, Conley RC, Jones

EG, et al: Chromatin alterations associated with down-regulated

metabolic gene expression in the prefrontal cortex of subjects with

schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 62:829–840. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Bahari-Javan S, Varbanov H, Halder R,

Benito E, Kaurani L, Burkhardt S, Anderson-Schmidt H, Anghelescu I,

Budde M, Stilling RM, et al: HDAC1 links early life stress to

schizophrenia-like phenotypes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

114:E4686–E4694. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Schroeder FA, Gilbert TM, Feng N, Taillon

BD, Volkow ND, Innis RB, Hooker JM and Lipska BK: Expression of

HDAC2 but Not HDAC1 transcript is reduced in dorsolateral

prefrontal cortex of patients with schizophrenia. ACS Chem

Neurosci. 8:662–668. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Dickerson F, Schroeder JR, Nimgaonkar V,

Gold J and Yolken R: The association between exposure to herpes

simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) and cognitive functioning in

schizophrenia: A meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res.

291(113157)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Tripathy S, Singh N, Singh A and Kar SK:

COVID-19 and psychotic symptoms: The view from psychiatric

immunology. Curr Behav Neurosci Rep. 8:172–178. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Banerjee D and Viswanath B:

Neuropsychiatric manifestations of COVID-19 and possible pathogenic

mechanisms: Insights from other coronaviruses. Asian J Psychiatr.

54(102350)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Klein HC, Guest PC, Dobrowolny H and

Steiner J: Inflammation and viral infection as disease modifiers in

schizophrenia. Front Psychiatry. 14(1231750)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Pandey JP, Namboodiri AM and Elston RC:

Immunoglobulin G genotypes and the risk of schizophrenia. Hum

Genet. 135:1175–1179. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Inyang B, Gondal FJ, Abah GA, Minnal

Dhandapani M, Manne M, Khanna M, Challa S, Kabeil AS and Mohammed

L: The role of childhood trauma in psychosis and schizophrenia: A

systematic review. Cureus. 14(e21466)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Thomson P and Jaque SV: Childhood

adversity and the creative experience in adult professional

performing artists. Front Psychol. 9(111)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Buscemi V, Chang WJ, Liston MB, McAuley JH

and Schabrun S: The role of psychosocial stress in the development

of chronic musculoskeletal pain disorders: Protocol for a

systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst Rev.

6(224)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Li KJ, Chen A and DeLisi LE: Opioid use

and schizophrenia. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 33:219–224.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Guloksuz S, Rutten BPF, Pries LK, Ten Have

M, de Graaf R, van Dorsselaer S, Klingenberg B, van Os J and

Ioannidis JPA: European Network of National Schizophrenia Networks

Studying Gene-Environment Interactions Work Package 6 (EU-GEI WP6)

Group. The complexities of evaluating the exposome in psychiatry: A

data-driven illustration of challenges and some propositions for

amendments. Schizophr Bull. 44:1175–1179. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Rodriguez-Gonzalez A and Orio L:

Microbiota and alcohol use disorder: Are psychobiotics a novel

therapeutic strategy? Curr Pharm Des. 26:2426–2437. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Clausing ES and Non AL: Epigenetics as a

mechanism of developmental embodiment of stress, resilience, and

cardiometabolic risk across generations of latinx immigrant

families. Front Psychiatry. 12(696827)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Jaaro-Peled H and Sawa A:

Neurodevelopmental factors in schizophrenia. Psychiatr Clin North

Am. 43:263–274. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Karlsson H and Dalman C: Epidemiological

studies of prenatal and childhood infection and schizophrenia. Curr

Top Behav Neurosci. 44:35–47. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Ju S, Shin Y, Han S, Kwon J, Choi TG, Kang

I and Kim SS: The gut-brain axis in schizophrenia: The implications

of the gut microbiome and SCFA production. Nutrients.

15(4391)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Tandon R, Nasrallah H, Akbarian S,

Carpenter WT Jr, DeLisi LE, Gaebel W, Green MF, Gur RE, Heckers S,

Kane JM, et al: The schizophrenia syndrome, circa 2024: What we

know and how that informs its nature. Schizophr Res. 264:1–28.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Al-Haddad BJS, Oler E, Armistead B,

Elsayed NA, Weinberger DR, Bernier R, Burd I, Kapur R, Jacobsson B,

Wang C, et al: The fetal origins of mental illness. Am J Obstet

Gynecol. 221:549–562. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Desmettre T: Toxoplasmosis and behavioural

changes. J Fr Ophtalmol. 43:e89–e93. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Maldonado YA and Read JS: COMMITTEE ON

INFECTIOUS DISEASES. Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of

congenital toxoplasmosis in the United States. Pediatrics.

139(e20163860)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Chen X, Chen B, Hou X, Zheng C, Yang X, Ke

J, Hu X and Tan F: Association between Toxoplasma gondii infection

and psychiatric disorders in Zhejiang, Southeastern China. Acta

Trop. 192:82–86. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Liu T, Gao P, Bu D and Liu D: Association

between Toxoplasma gondii infection and psychiatric disorders: A

cross-sectional study in China. Sci Rep. 12(15092)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Veleva I, Stoychev K, Stoimenova-Popova M,

Stoyanov L, Mineva-Dimitrova E and Angelov I: Toxoplasma gondii

seropositivity and cognitive function in adults with schizophrenia.

Schizophr Res Cogn. 30(100269)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Acquarone M, Poleto A, Perozzo AF,

Gonçalves PFR, Panizzutti R, Menezes JRL, Neves GA and Barbosa HS:

Social preference is maintained in mice with impaired startle

reflex and glutamate/D-serine imbalance induced by chronic cerebral

toxoplasmosis. Sci Rep. 11(14029)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Lucchese G: From toxoplasmosis to

schizophrenia via NMDA dysfunction: Peptide overlap between

toxoplasma gondii and N-Methyl-d-Aspartate receptors as a potential

mechanistic link. Front Psychiatry. 8(37)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Bhavsar V, Boydell J, McGuire P, Harris V,

Hotopf M, Hatch SL, MacCabe JH and Morgan C: Childhood abuse and

psychotic experiences-evidence for mediation by adulthood adverse

life events. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 28:300–309. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

67

|

Sheffield JM, Karcher NR and Barch DM:

Cognitive deficits in psychotic disorders: A lifespan perspective.

Neuropsychol Rev. 28:509–533. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

68

|

Kaufman J and Torbey S: Child maltreatment

and psychosis. Neurobiol Dis. 131(104378)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

69

|

Powers A, Fani N, Cross D, Ressler KJ and

Bradley B: Childhood trauma, PTSD, and psychosis: Findings from a

highly traumatized, minority sample. Child Abuse Negl. 58:111–118.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

70

|

Vila-Badia R, Butjosa A, Del Cacho N,

Serra-Arumí C, Esteban-Sanjusto M, Ochoa S and Usall J: Types,

prevalence and gender differences of childhood trauma in

first-episode psychosis. What is the evidence that childhood trauma

is related to symptoms and functional outcomes in first episode

psychosis? A systematic review. Schizophr Res. 228:159–179.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

71

|

Abdel-Baki A, Ouellet-Plamondon C, Salvat

É, Grar K and Potvin S: Symptomatic and functional outcomes of

substance use disorder persistence 2 years after admission to a

first-episode psychosis program. Psychiatry Res. 247:113–119.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

72

|

Di Forti M, Quattrone D, Freeman TP,

Tripoli G, Gayer-Anderson C, Quigley H, Rodriguez V, Jongsma HE,

Ferraro L, La Cascia C, et al: The contribution of cannabis use to

variation in the incidence of psychotic disorder across Europe

(EU-GEI): A multicentre case-control study. Lancet Psychiatry.

6:427–436. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

73

|

Morgan C, Charalambides M, Hutchinson G

and Murray RM: Migration, ethnicity, and psychosis: Toward a

sociodevelopmental model. Schizophr Bull. 36:655–664.

2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

74

|

Porter M and Haslam N: Predisplacement and

postdisplacement factors associated with mental health of refugees

and internally displaced persons: A meta-analysis. JAMA.

294:602–612. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

75

|

Veling W, Selten JP, Susser E, Laan W,

Mackenbach JP and Hoek HW: Discrimination and the incidence of

psychotic disorders among ethnic minorities in The Netherlands. Int

J Epidemiol. 36:761–768. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

76

|

Benros ME and Mortensen PB: Role of

infection, autoimmunity, atopic disorders, and the immune system in

schizophrenia: Evidence from epidemiological and genetic studies.

Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 44:141–159. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

77

|

Wang AW, Avramopoulos D, Lori A, Mulle J,

Conneely K, Powers A, Duncan E, Almli L, Massa N, McGrath J, et al:

Genome-wide association study in two populations to determine

genetic variants associated with Toxoplasma gondii infection and

relationship to schizophrenia risk. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol

Psychiatry. 92:133–147. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

78

|

Lori A, Avramopoulos D, Wang AW, Mulle J,

Massa N, Duncan EJ, Powers A, Conneely K, Gillespie CF, Jovanovic

T, et al: Polygenic risk scores differentiate schizophrenia

patients with toxoplasma gondii compared to toxoplasma seronegative

patients. Compr Psychiatry. 107(152236)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

79

|

Xiao J, Prandovszky E, Kannan G, Pletnikov

MV, Dickerson F, Severance EG and Yolken RH: Toxoplasma gondii:

Biological parameters of the connection to schizophrenia. Schizophr

Bull. 44:983–992. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

80

|

Hong J and Bang M: Anti-inflammatory

strategies for schizophrenia: A review of evidence for therapeutic

applications and drug repurposing. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci.

18:10–24. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

81

|

Avramopoulos D, Pearce BD, McGrath J,

Wolyniec P, Wang R, Eckart N, Hatzimanolis A, Goes FS, Nestadt G,

Mulle J, et al: Infection and inflammation in schizophrenia and

bipolar disorder: A genome wide study for interactions with genetic

variation. PLoS One. 10(e0116696)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

82

|

Estes ML and McAllister AK: Maternal

immune activation: Implications for neuropsychiatric disorders.

Science. 353:772–777. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

83

|

Reisinger S, Khan D, Kong E, Berger A,

Pollak A and Pollak DD: The poly(I:C)-induced maternal immune

activation model in preclinical neuropsychiatric drug discovery.

Pharmacol Ther. 149:213–226. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

84

|

Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Cannon M, McClay J,

Murray R, Harrington H, Taylor A, Arseneault L, Williams B,

Braithwaite A, et al: Moderation of the effect of adolescent-onset

cannabis use on adult psychosis by a functional polymorphism in the

catechol-O-methyltransferase gene: longitudinal evidence of a gene

X environment interaction. Biol Psychiatry. 57:1117–1127.

2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

85

|

Zammit S, Spurlock G, Williams H, Norton

N, Williams N, O'Donovan MC and Owen MJ: Genotype effects of

CHRNA7, CNR1 and COMT in schizophrenia: Interactions with tobacco

and cannabis use. Br J Psychiatry. 191:402–407. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

86

|

Akhtar MJ, Yar MS, Grover G and Nath R:

Neurological and psychiatric management using COMT inhibitors: A

review. Bioorg Chem. 94(103418)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

87

|

Henquet C, Rosa A, Krabbendam L, Papiol S,

Fananás L, Drukker M, Ramaekers JG and van Os J: An experimental

study of catechol-o-methyltransferase Val158Met moderation of

delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol-induced effects on psychosis and

cognition. Neuropsychopharmacology. 31:2748–2757. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

88

|

van Winkel R, Stefanis NC and Myin-Germeys

I: Psychosocial stress and psychosis. A review of the

neurobiological mechanisms and the evidence for gene-stress

interaction. Schizophr Bull. 34:1095–1105. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

89

|

Hindocha C, Quattrone D, Freeman TP,

Murray RM, Mondelli V, Breen G, Curtis C, Morgan CJA, Valerie

Curran H and Di Forti M: Do AKT1, COMT and FAAH influence reports

of acute cannabis intoxication experiences in patients with first

episode psychosis, controls and young adult cannabis users? Transl

Psychiatry. 10(143)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

90

|

Hiemstra M, Nelemans SA, Branje S, van

Eijk KR, Hottenga JJ, Vinkers CH, van Lier P, Meeus W and Boks MP:

Genetic vulnerability to schizophrenia is associated with cannabis

use patterns during adolescence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 190:143–150.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

91

|

Dzirasa K and Covington HE 3rd: Increasing

the validity of experimental models for depression. Ann N Y Acad

Sci. 1265:36–45. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

92

|

Hvoslef-Eide M, Mar AC, Nilsson SR, Alsiö

J, Heath CJ, Saksida LM, Robbins TW and Bussey TJ: The NEWMEDS

rodent touchscreen test battery for cognition relevant to

schizophrenia. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 232:3853–3872.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

93

|

Modinos G, Allen P, Grace AA and McGuire

P: Translating the MAM model of psychosis to humans. Trends

Neurosci. 38:129–138. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

94

|

Talamini LM, Ellenbroek B, Koch T and Korf

J: Impaired sensory gating and attention in rats with developmental

abnormalities of the mesocortex. Implications for schizophrenia.

Ann N Y Acad Sci. 911:486–494. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

95

|

Paylor JW, Lins BR, Greba Q, Moen N, de

Moraes RS, Howland JG and Winship IR: Developmental disruption of

perineuronal nets in the medial prefrontal cortex after maternal

immune activation. Sci Rep. 6(37580)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

96

|

Steullet P, Cabungcal JH, Coyle J,

Didriksen M, Gill K, Grace AA, Hensch TK, LaMantia AS, Lindemann L,

Maynard TM, et al: Oxidative stress-driven parvalbumin interneuron

impairment as a common mechanism in models of schizophrenia. Mol

Psychiatry. 22:936–943. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

97

|

Careaga M, Murai T and Bauman MD: Maternal

immune activation and autism spectrum disorder: From rodents to

nonhuman and human primates. Biol Psychiatry. 81:391–401.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

98

|

Sams-Dodd F: A test of the predictive

validity of animal models of schizophrenia based on phencyclidine

and D-amphetamine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 18:293–304.

1998.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

99

|

Kittirattanapaiboon P, Mahatnirunkul S,

Booncharoen H, Thummawomg P, Dumrongchai U and Chutha W: Long-term

outcomes in methamphetamine psychosis patients after first

hospitalisation. Drug Alcohol Rev. 29:456–461. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

100

|

Lecomte T, Dumais A, Dugré JR and Potvin

S: The prevalence of substance-induced psychotic disorder in

methamphetamine misusers: A meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res.

268:189–192. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

101

|

Medhus S, Rognli EB, Gossop M, Holm B,

Mørland J and Bramness JG: Amphetamine-induced psychosis:

Transition to schizophrenia and mortality in a small prospective

sample. Am J Addict. 24:586–589. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

102

|

Wearne TA, Mirzaei M, Franklin JL,

Goodchild AK, Haynes PA and Cornish JL: Methamphetamine-induced

sensitization is associated with alterations to the proteome of the

prefrontal cortex: Implications for the maintenance of psychotic

disorders. J Proteome Res. 14:397–410. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

103

|

El-Sayed El-Sisi A, Sokkar SS, El-Sayed

El-Sayad M, Sayed Ramadan E and Osman EY: Celecoxib and omega-3

fatty acids alone and in combination with risperidone affect the

behavior and brain biochemistry in amphetamine-induced model of

schizophrenia. Biomed Pharmacother. 82:425–431. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

104

|

Kalinichev M, Robbins MJ, Hartfield EM,

Maycox PR, Moore SH, Savage KM, Austin NE and Jones DN: Comparison

between intraperitoneal and subcutaneous phencyclidine

administration in Sprague-Dawley rats: A locomotor activity and

gene induction study. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry.

32:414–422. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

105

|

Dennison CA, Legge SE, Pardiñas AF and

Walters JTR: Genome-wide association studies in schizophrenia:

Recent advances, challenges and future perspective. Schizophr Res.

217:4–12. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

106

|

Keller MC: Evolutionary perspectives on

genetic and environmental risk factors for psychiatric disorders.

Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 14:471–493. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

107

|

Power RA, Kyaga S, Uher R, MacCabe JH,

Långström N, Landen M, McGuffin P, Lewis CM, Lichtenstein P and

Svensson AC: Fecundity of patients with schizophrenia, autism,

bipolar disorder, depression, anorexia nervosa, or substance abuse

vs their unaffected siblings. JAMA Psychiatry. 70:22–30.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

108

|

Bray NJ, Kapur S and Price J:

Investigating schizophrenia in a ‘dish’: Possibilities, potential

and limitations. World Psychiatry. 11:153–155. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

109

|

Kovalevich J and Langford D:

Considerations for the use of SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells in

neurobiology. Methods Mol Biol. 1078:9–21. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

110

|

Bell M, Bachmann S, Klimek J,

Langerscheidt F and Zempel H: Axonal TAU sorting requires the

C-terminus of TAU but is independent of ANKG and TRIM46 Enrichment

at the AIS. Neuroscience. 461:155–171. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

111

|

Paik S, Somvanshi RK and Kumar U:

Somatostatin-mediated changes in microtubule-associated proteins

and retinoic acid-induced neurite outgrowth in SH-SY5Y cells. J Mol

Neurosci. 68:120–134. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

112

|

Farber NB, Wozniak DF, Price MT, Labruyere

J, Huss J, St Peter H and Olney JW: Age-specific neurotoxicity in

the rat associated with NMDA receptor blockade: Potential relevance

to schizophrenia? Biol Psychiatry. 38:788–796. 1995.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

113

|

Berdenis van Berlekom A, Muflihah CH,

Snijders GJLJ, MacGillavry HD, Middeldorp J, Hol EM, Kahn RS and de

Witte LD: Synapse pathology in schizophrenia: A meta-analysis of

postsynaptic elements in postmortem brain studies. Schizophr Bull.

46:374–386. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

114

|

Piñero-Martos E, Ortega-Vila B, Pol-Fuster

J, Cisneros-Barroso E, Ruiz-Guerra L, Medina-Dols A, Heine-Suñer D,

Lladó J, Olmos G and Vives-Bauzà C: Disrupted in schizophrenia 1

(DISC1) is a constituent of the mammalian mitochondrial contact

site and cristae organizing system (MICOS) complex, and is

essential for oxidative phosphorylation. Hum Mol Genet.

25:4157–4169. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

115

|

Peykov S, Berkel S, Schoen M, Weiss K,

Degenhardt F, Strohmaier J, Weiss B, Proepper C, Schratt G, Nöthen

MM, et al: Identification and functional characterization of rare

SHANK2 variants in schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 20:1489–1498.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

116

|

Unsicker C, Cristian FB, von Hahn M,

Eckstein V, Rappold GA and Berkel S: SHANK2 mutations impair

apoptosis, proliferation and neurite outgrowth during early

neuronal differentiation in SH-SY5Y cells. Sci Rep.

11(2128)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

117

|

Wu S, Wang P, Tao R, Yang P, Yu X, Li Y,

Shao Q, Nie F, Ha J, Zhang R, et al: Schizophrenia-associated

microRNA-148b-3p regulates COMT and PRSS16 expression by targeting

the ZNF804A gene in human neuroblastoma cells. Mol Med Rep.

22:1429–1439. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

118

|

Toyoshima M, Akamatsu W, Okada Y, Ohnishi

T, Balan S, Hisano Y, Iwayama Y, Toyota T, Matsumoto T, Itasaka N,

et al: Analysis of induced pluripotent stem cells carrying 22q11.2

deletion. Transl Psychiatry. 6(e934)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

119

|

Lee IS, Carvalho CM, Douvaras P, Ho SM,

Hartley BJ, Zuccherato LW, Ladran IG, Siegel AJ, McCarthy S,

Malhotra D, et al: Characterization of molecular and cellular

phenotypes associated with a heterozygous CNTNAP2 deletion using

patient-derived hiPSC neural cells. NPJ Schizophr. 1:15019-.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

120

|

Wen Z, Nguyen HN, Guo Z, Lalli MA, Wang X,

Su Y, Kim NS, Yoon KJ, Shin J, Zhang C, et al: Synaptic

dysregulation in a human iPS cell model of mental disorders.

Nature. 515:414–418. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

121

|

McCutcheon RA, Krystal JH and Howes OD:

Dopamine and glutamate in schizophrenia: Biology, symptoms and

treatment. World Psychiatry. 19:15–33. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

122

|

Cohen SM, Tsien RW, Goff DC and Halassa

MM: The impact of NMDA receptor hypofunction on GABAergic neurons

in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 167:98–107.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

123

|

Raabe FJ, Slapakova L, Rossner MJ,

Cantuti-Castelvetri L, Simons M, Falkai PG and Schmitt A:

Oligodendrocytes as a new therapeutic target in schizophrenia: From

histopathological findings to neuron-oligodendrocyte interaction.

Cells. 8(1496)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

124

|

Tran NN, Ladran IG and Brennand KJ:

Modeling schizophrenia using induced pluripotent stem cell-derived

and fibroblast-induced neurons. Schizophr Bull. 39:4–10.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

125

|

Liu Y, Pham X, Zhang L, Chen PL, Burzynski

G, McGaughey DM, He S, McGrath JA, Wolyniec P, Fallin MD, et al:

Functional variants in DPYSL2 sequence increase risk of

schizophrenia and suggest a link to mTOR signaling. G3 (Bethesda).

5:61–72. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

126

|

Stratton H, Boinon L, Moutal A and Khanna

R: Coordinating synaptic signaling with CRMP2. Int J Biochem Cell

Biol. 124(105759)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|