Introduction

Heart failure (HF) occurs when the heart loses its

ability to pump sufficient amounts of blood to the body. HF

represents a pervasive global public health challenge, affecting

>64 million individuals worldwide, and exhibits a growing

prevalence due to the aging population (1,2). The

prevalence of HF exhibited a notable increase from 641.14/100,000

individuals in 1990 to 676.68/100,000 individuals in 2021, with men

(760.78/100,000) showing an increased incidence rate compared with

women (604/100,000) (3). HF may be

caused by numerous different conditions, including right

ventricular dysfunction, left ventricular (LV) dysfunction,

pericardial disease, valvular heart disease and obstructive lesions

in the great vessels or heart (4).

Despite notable improvements in pharmacological (nesiritide,

ularitide, inotropic agents, serelaxin, angiotensin II type 1

receptor, rolofylline) and non-pharmacological (ventilator support,

ultrafiltration) treatment strategies (5), HF continues to be associated with

high morbidity, frequent hospitalizations, impaired quality of life

and substantial mortality rates [32% deaths in patients who had HF

with LV ejection fraction (LVEF) <40%] (6). This burden is magnified in the

context of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), a frequent comorbidity

that not only accelerates HF progression but also complicates

management strategies (7).

Importantly, the pathophysiological association between

hyperglycemia, oxidative stress, insulin resistance, myocardial

fibrosis and inflammation, contributes to both functional and

structural deterioration of the heart (8). Thus, targeting the overlapping

mechanisms of diabetes and HF has been of great interest. Among

recent and emerging therapies, sodium-glucose cotransporter 2

inhibitors (SGLT2i), which were initially developed for glycemic

control, demonstrate promise as potent agents conferring

cardiovascular (CV) and renal protection, beyond the

glucose-lowering effect they exhibit (9,10).

Notable CV outcome trials in patients with T2DM first demonstrated

a reduction in hospitalizations related to HF and CV mortality,

establishing the foundation for dedicated HF trials that excluded

diabetes status as an inclusion criterion (11,12).

Subsequently, high-quality randomized controlled

trials (RCTs) across the spectrum of HF phenotypes, ranging from

reduced to preserved ejection fraction and including non-diabetic

individuals, have consistently demonstrated that SGLT2i reduce HF

hospitalizations, improve functional capacity and enhance

health-related quality of life (13). RCTs, such as the ‘Dapagliflozin and

Prevention of Adverse Outcomes in HF’ trial (DAPA-HF) and the

empagliflozin outcome trial in patients with preserved ejection

fraction (EMPEROR-preserved), have highlighted the efficacy of

SGLT2i in reducing HF-related hospitalizations and CV mortality,

extending their use to non-diabetic populations (14,15).

These patient-centered benefits, as evidenced by the Kansas City

Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) and New York Heart Association

functional classification scores, underscore the broader importance

of SGLT2i in HF management (16).

Beyond their glucose-lowering effects, SGLT2i

exhibit pleiotropic benefits, including natriuresis, blood pressure

reduction, improved ventricular loading conditions and potential

direct myocardial effects (17).

Previous meta-analyses have supported the favorable effect of

SGLT2i on HF outcomes; however, they tended to include a limited

number of studies with heterogeneous populations (18,19).

Therefore, questions remain regarding the consistency and magnitude

of SGLT2i benefits across diabetic and non-diabetic patients, and

whether the observed outcomes are uniformly applicable across a

number of patient populations and HF phenotypes. Moreover, as

evidence continues to accumulate from both CV outcome trials and

HF-specific RCTs, an updated and more focused analysis with

additional variables is warranted. Therefore, the present

systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to collect evidence from

RCTs to evaluate the effect of SGLT2i on HF outcomes in adults with

and without T2DM. The primary objective was to determine whether

SGLT2i reduces the risk of hospitalization for HF across this

population. Secondary objectives included assessing the impact of

SGLT2i on CV mortality, all-cause mortality and adverse events.

Materials and methods

Data sources and search

Comprehensive literature searches were performed in

PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science and Cochrane Central, from database

inception to May 2025, applying combinations of vocabulary and key

words related to SGLT2i, empagliflozin, canagliflozin,

dapagliflozin and HF. These search terms were combined using

Boolean operators and the detailed search strategy is described in

Table SI. The present systematic

review and meta-analysis was designed following the Preferred

Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)

2020 guidelines (20).

Eligibility criteria and outcomes

Eligible studies included phase II-IV RCTs enrolling

adult patients (aged ≥18 years) diagnosed with HF, irrespective of

ejection fraction category or diabetes status. Studies must have

compared any SGLT2i with a placebo or standard-of-care treatment

and reported at least one of the following outcomes: i)

Hospitalization for HF (primary outcome); ii) CV mortality; iii)

all-cause mortality; iv) ejection fraction; v) myocardial

infraction; or vi) health-related quality of life assessed

according to the KCCQ. Studies that exclusively enrolled pediatric

populations, animal models or healthy volunteers were excluded.

Additionally, trials lacking extractable outcome data or those

without stratification by diabetes status were also excluded.

Study selection process

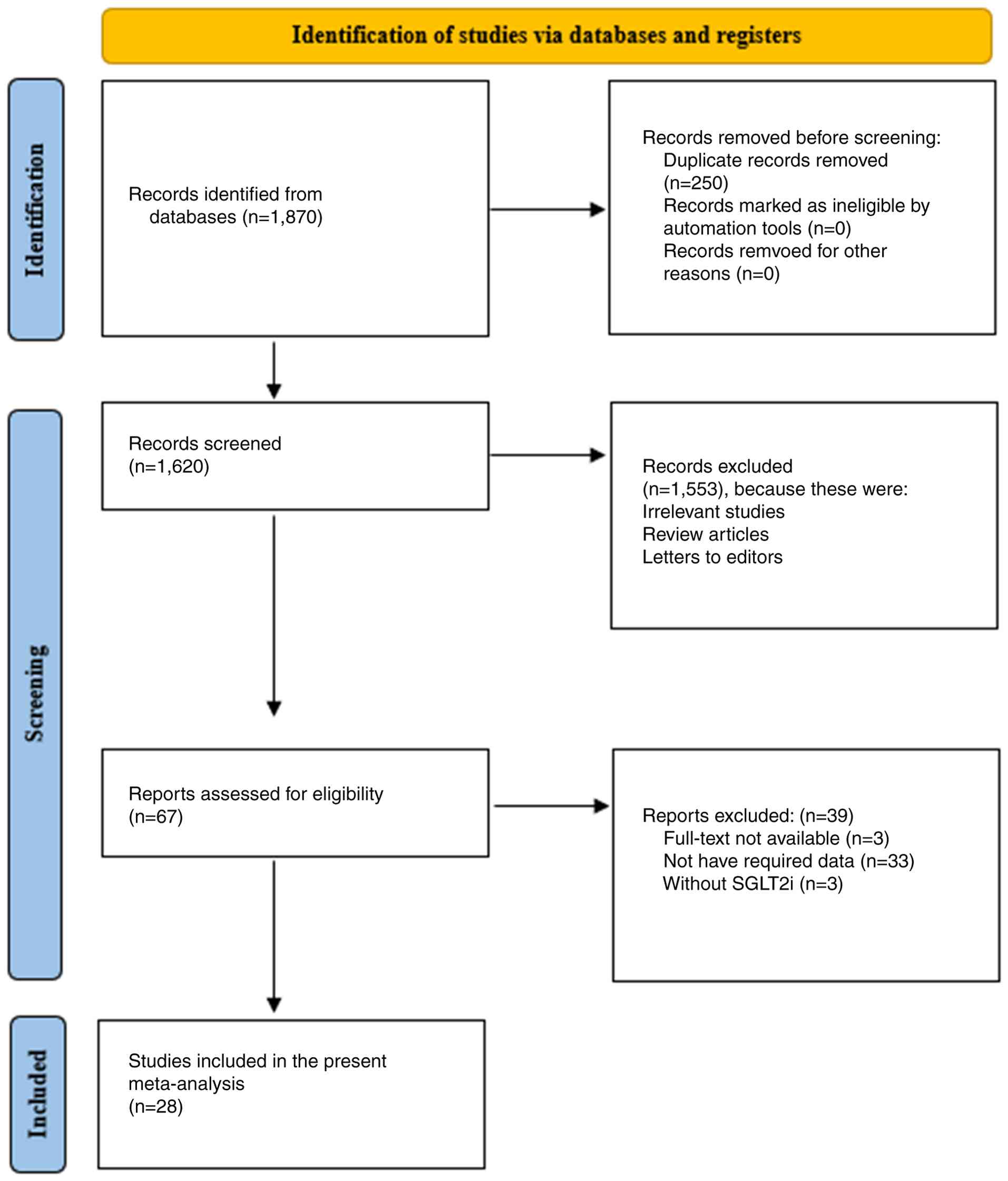

Independent screening processes were carried out by

two authors using the PRISMA flow chart. In the first phase, 1,870

studies were retrieved through a search in different electronic

databases and 250 duplicate studies were removed using the EndNote

X9 referencing software (Clarivate; www.endnote.com). In the second phase, 1,620 studies

were screened by checking their titles and abstracts, and 1,553

studies were excluded due to being irrelevant, or being reviews or

letters to editors, leaving 67 studies eligible for full-text

assessment. During the full-text assessment, 39 studies were

excluded due to non-availability of the full text, not reporting

the required outcomes or not having used SGLT2i. The study

selection process is illustrated in Fig. 1. Finally, 28 studies were selected

for qualitative and quantitative analysis. Discrepancies were

resolved through consensus or consultation with a third author.

Data extraction

Data were extracted from each eligible study by two

independent authors, using a predefined data collection form.

Extracted information included study characteristics (author, year

of publication, country, trial phase and sample size), participant

demographics (age, sex, diabetes status and baseline LVEF),

intervention and comparator details (agent, dosage, administration

route and treatment duration), follow-up periods and reported

effect estimates [hazard ratios (HRs), risk ratios and mean

differences with 95% CIs].

Methodological quality and risk of

bias assessment

Risk of bias was assessed at the study level using

the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2.0 tool (https://methods.cochrane.org/bias/resources/rob-2-revised-cochrane-risk-bias-tool-randomized-trials),

with judgments made in the domains of randomization, deviations

from intended interventions, missing outcome data, measurement of

outcomes and selective reporting. Outcomes were reported in the

form of visualization judgments associated with each risk of bias

item and presented as percentages using the web-based application

Risk of Bias VISualization (21).

This entire process was performed by two independent authors and

any discrepancies were resolved with the consultation of a third

senior author.

Meta-analysis

For qualitative data, narrative synthesis was

performed, with key characteristics of studies and patients

presented as tables. Quantitative data were analyzed using RevMan

5.4 (https://www.cochrane.org/learn/courses-and-resources/software)

for the construction of forest plots using a random-effects model.

The association between HF clinical outcomes and SGLT2i was

measured using a χ2 test and P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference. Heterogeneity

among studies was calculated using the I2 statistic,

with a heterogeneity of <25, 26-75 and >75% being considered

as low, moderate and high, respectively. Funnel plots were

constructed for publication bias. If the distribution of studies

was symmetrical and a clear funnel shape was observed, low

publication bias was found among the studies, while an asymmetrical

distribution of studies without a clear funnel shape indicated a

higher publication bias. The funnel plot asymmetry was evaluated

using Egger's linear regression test through RStudio software

(version 4.0.2; Posit Software, PBC) for Windows.

Certainty of evidence

Certainty of evidence was evaluated using the

Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation

framework (22), a reproducible

and structured framework used for the assessment of outcomes

derived from the included studies. The level of certainty ranges

from low to high after considering specific criteria, such as the

risk of bias, result inconsistency and publication bias.

Results

General characteristics of

studies

Numerous included studies were performed in multiple

countries from Latin America, North America, South America, Europe

and Asia. However, a limited number of studies were also performed

in a single country, such as the USA (23-25),

the UK (26,27), Australia (28), Canada (29) and the Netherlands (30). The majority of the studies were

part of trials or programs, as described in Table I. Sample sizes varied notably and

the majority of the studies used large sample sizes ranging from

8,582 to 8,578 individuals in the intervention and placebo groups

(31), with the lowest sample size

of 162 individuals in both the intervention and placebo groups

(23). Overall, studies included

middle-aged and elderly individuals, between 61 and 73 years of

age, with predominant male representation (Table I). Furthermore, the majority of the

studies included patients with diabetes only (25,28,29,31-41),

while a reasonable number of studies analyzed both diabetic and

non-diabetic patients (23,24,26,27,30,42-50).

BMI also markedly ranged from average (<25 kg/m2) to

obese (35.1 kg/m2) (23,39).

Among the comorbidities, hypertension and kidney-associated

diseases were the most prevalent (Table I). In addition, a number of studies

focused on patients with an LVEF of <45 or <40% (23,27,32,36,42-44,47,48,50),

while one study focused on the preserved or reduced range of

ejection fraction and one study gave chronic kidney disease (CKD)

stage information (49), as

described in Table I.

| Table ISummary of general characteristics of

the included studies. |

Table I

Summary of general characteristics of

the included studies.

| Study

characteristics | Participant

characteristics |

|---|

| First author,

year | Country | Trial phase | Sample size, N | Age, years | Sex, M:F | Diabetic

status | Comorbidities | BMI,

kg/m2 | Baseline LVEF | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Zinman et

al, 2015 | Multinational (42

countries from North America, Australia, New Zealand, Latin

America, Europe, Africa and Asia) | NA | Intervention group,

468,7; control group, 233,3 | Intervention group,

63.2; control group, 63.1 | Intervention group,

333,6:135,1; control group, 168,0:653 | Diabetic

patients | NA | Intervention group,

30.6; control group, 30.7 | NA | (41) |

| Fitchett et

al, 2016 | Multinational (42

countries) | EMPA-REG OUTCOME

trial | Intervention group,

468,7; control group, 233,3 | Intervention group,

63.1; control group, 63.1 | 505,4:196,6 | Diabetic

patients | NA | 30.6 | NA | (34) |

| Neal et al,

2017 | Multinational (30

countries) | NA | Intervention group,

579,5; control group, 434,7 | Intervention group,

63.2; control group, 63.4 | Intervention group,

375,9:203,6; control group, 275,0:159,7 | Diabetes

(chronic) | Hypertension | Intervention group,

31.9; control group, 32.0 | NA | (38) |

| Wanner et

al, 2018 | Multinational

(countries from Europe, North America, Asia, Africa, Latin America,

Australia and New Zealand) | NA | Intervention group,

464,7; control group, 222,7 | 61.0 | Intervention group,

330,2:134,5; control group, 167,1:556 | Diabetic

patients | Kidney

diseases | 30.8 | NA | (40) |

| Mahaffey et

al, 2018 | Multinational

(North America, South/Central America, Europe and the rest of the

world) | CANVAS program | 101,42 |

62.7-63.8a | 650,9:363,3 | Diabetic

patients | Hypertension |

31.7-32.5b | NA | (37) |

| Kato et al,

2019 | Multinational

(countries from North America, Latin America, Europe and the Asia

Pacific) | DECLARE-TIMI 58

trial | 171,60 | 63-65a | 108,11:634,9 | Diabetic

patients | Hypertension |

31.1-31.6b | <45% (n=671),

>45% (n=808) | (36) |

| McMurray et

al, 2019 | Multinational

(countries from North and South America, Europe and the Asia

Pacific) | Phase 3 | Intervention group,

237,3; control group, 237,1 | Intervention group,

66.2; control group, 66.5 | Intervention group,

180,9:564; control group, 1,826:545 | With or without

diabetes | NA | Intervention group,

28.2; control group, 28.1 | <40% | (48) |

| Wiviott et

al, 2019 | Multinational

(North America, Latin America, Europe and Asia Pacific) | DECLARE-TIMI 58

trial/phase 3 | Intervention group,

858,2; control group, 857,8 | Intervention group,

63.9; control group, 64.0 | Intervention group,

541,1:317,1; control group, 5,327:3,251 | Diabetic

patients | NA | Intervention group,

32.1; control group, 32.0 | NA | (31) |

| Perkovic et

al, 2019 | Australia | NA | Intervention group,

220,2; control group, 219,9 | Intervention group,

62.9; control group, 63.2 | Intervention group,

144,0:762; control group, 146,7:732 | Diabetic

patients | Hypertension | Intervention group,

31.4; control group, 31.3 | NA | (28) |

| Cannon et

al, 2020 | Multinational

(countries from North and South America, Asia, Europe, South

Africa, New Zealand and Australia) | NA | Intervention group,

549,9; control group, 274,7 | 64.4 | Intervention group,

386,6:163,3; control group, 1,903:844 | Diabetic

patients | Coronary artery

disease, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral arterial disease and

MI | Intervention group,

31.9; control group, 32.0 | NA | (33) |

| Heerspink et

al, 2020 | The

Netherlands | NA | Intervention group,

215,2; control group, 215,2 | Intervention group,

61.8; control group, 61.9 | Intervention group,

144,3:709; control group, 143,6:716 | With or without

diabetes | Kidney

diseases | Intervention group,

29.4; control group, 29.6 | NA | (30) |

| Kosiborod et

al, 2020 | Multinational

(countries from the Asia Pacific, Europe, North and South

America) | DAPA-HF trial | 444,3 | 66.3 | 345,2:991 | With or without

diabetes | Hypertension | NA | 6.8% | (46) |

| Inzucchi et

al, 2020 | Multinational

(countries from Europe, Asia, Latin America, North America and

Africa) | EMPA-REG OUTCOME

trial | Intervention group,

468,7; control group, 233,3 |

62.5-63.4a | 495,1:198,4 | Diabetic

patients | NA | NA | NA | (35) |

| Verma et al,

2020 | Canada | EMPA-REG OUTCOME

trial | 702,0 |

61.4-65.5a | NA | Diabetic

patients | Hypertension |

30.0-31.0b | NA | (29) |

| Ohkuma et

al, 2020 | Multinational | CANVAS program | 101,28 |

62.8-64.0a | 650,1:362,7 | Diabetic

patients | Hypertension | <25.0 or

>30.0 | NA | (39) |

| Bhatt et al,

2021 | Multinational

(countries from North America, Latin America, western Europe,

eastern Europe and the rest of the world) | NA | Intervention group,

608; control group, 614 | Intervention group,

69.0; control group, 70.0 | Intervention group,

410:198; control group, 400:214 | Diabetic

patients | NA | NA | <50%:

Intervention group (n=481) and control group (n=485) | (32) |

| McMurray et

al, 2021 | Multinational

(Europe, Asia Pacific, South and North America) | NA | 430,4 |

61.4-65.3a | 287,9:142,5 | With or without

diabetes | CKD, hypertension,

angina, MI and stroke | NA | NA | (49) |

| Nassif et

al, 2021 | USA | NA | Intervention group,

162; control group, 162 | Intervention group,

69.0; control group, 71.0 | Intervention group,

70:92; control group, 70:92 | With or without

diabetes | NA | Intervention group,

35.1; control group, 34.6 | Intervention group,

60%; control group, 60% | (23) |

| Anker et al,

2021 | Multinational

(countries from Latin and North America, Europe and Asia) | EMPEROR-preserved

trial | Intervention group,

299,7; control group, 299,1 | Intervention group,

71.8; control group, 71.9 | Intervention group;

165,9:133,8; control group, 165,3:133,8 | With or without

diabetes | NA | Intervention group,

29.77; control group, 29.90 | Intervention group:

≤50% (n=995), ≤60% (n=1,028), >60% (n=974); control group: ≤50%

(n=988), ≤60% (n=1,030) and >60% (n=973) | (42) |

| Anker et al,

2021 | Multinational

(countries from Latin and North America, Asia and Europe) | EMPEROR-reduced

trial | Intervention group,

299,7; control group, 299,1 |

66.3-67.6a | Intervention group,

165,9:133,8; control group, 165,3:133,8 | With or without

diabetes | Hypertension |

27.0-28.8b | ≤40% | (43) |

| Spertus et

al, 2022 | USA | CHIEF-HF | Intervention group,

222; control group, 226 | Intervention group,

62.9; control group, 64.0 | Intervention group,

118:104; control group, 129:97 | With or without

diabetes | NA | NA | NA | (24) |

| Kosiborod et

al, 2022 | Multinational

(countries from Asia, North America and Europe) | EMPULSE trial | Intervention group,

265; control group, 265 |

66.5-69.5a | 349:177 | With or without

diabetes | Hypertension |

27.4-32.6b | NA | (45) |

| Solomon et

al, 2022 | Multinational

(countries from Asia, Europe, Saudi Arabia, Latin and North

America) | NA | Intervention group,

313,1; control group, 313,2 | Intervention group,

71.8; control group, 71.5 | Intervention group,

176,7:136,4; control group, 174,9:138,3 | With or without

diabetes | Hypertension | NA | Intervention group,

54%; control group, 54.3% | (50) |

| Herrington et

al, 2023 | UK | NA | Intervention group,

330,4; control group, 330,5 | Intervention group,

63.9; control group, 63.8 | Intervention group,

220,7:109,7; control group, 221,0:109,5 | With or without

diabetes | NA | Intervention group,

29.7; control group, 29.8 | NA | (26) |

| Hernandez et

al, 2024 | Multinational (22

countries from North and Latin America, Europe and Asia) | NA | Intervention group,

326,0; control group, 326,2 | Intervention group,

63.6; control group, 63.7 | Intervention group,

244,8:812; control group, 244,9:813 | With or without

diabetes | Hypertension and

peripheral arterial disease | Intervention group,

28.1; control group, 28.1 | <45% in 78.4% of

patients | (44) |

| McMurray et

al, 2024 | Western Europe,

North America and the rest of the world | The DETERMINE

randomized clinical trials | DETERMINE-reduced

intervention group, 156; control group, 157. DETERMINE-preserved

intervention group, 253; control group, 251 | DETERMINE-reduced

intervention group, 69.0; control group, 69.0. DETERMINE-preserved

intervention group, 73.0; control group, 73.0 | DETERMINE-reduced

intervention group, 111:45; control group, 122:35.

DETERMINE-preserved intervention group, 162:91; control group,

158:93 | With or without

diabetes | NA | DETERMINE-reduced

intervention group, 28.0; control group, 29.0. DETERMINE-preserved

intervention group, 29.0; control group, 28.0 | DETERMINE-reduced

intervention group, 30%; control group, 29%. DETERMINE-preserved

intervention group, 50%; control group, 53% | (47) |

| Vaduganathan et

al, 2024 | USA | CANVAS program and

CREDENCE | 145,43 |

62-65.5a | 941,8:512,5 | Diabetic

patients | Kidney diseases and

hypertension | NA | NA | (25) |

| Petrie et

al, 2025 | UK | EMPACT-MI

trial | 652,2 |

63.0-64.0a | 489,2:163,0 | With or without

diabetes | Hypertension and

COPD |

27.0-29.0b | <45% | (27) |

Characteristics of intervention and

control groups

Among SGLT2i, the most commonly used agents were

empagliflozin (26,27,29,34,35,40-45),

dapagliflozin (23,30,31,36,46-50)

and canagliflozin (24,25,28,37-39),

while other less frequently used agents included ertugliflozin and

sotagliflozin (32,33). Most agents were administered orally

once daily; however, a wide range was observed in the dosages

administered, depending on the agent. Empagliflozin was

administered at a dose of 10 or 25 mg, dapagliflozin at 10 mg and

canagliflozin at either 100 or 300 mg, as described in Table II. Variation was also observed in

the treatment durations, ranging from 14 days (33,38,40,41,44)

to 2.6 years (34). Across all

included studies, a standard-of-care was used as a comparison

group, ensuring consistency in comparative evaluation (Table II).

| Table IISummary of intervention and control

characteristics. |

Table II

Summary of intervention and control

characteristics.

| | Intervention and

control characteristics | |

|---|

| First author,

year | Agent | Dosage | Administration

route | Treatment

duration | Control | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Zinman et

al, 2015 | Empagliflozin | 10 or 25 mg

daily | Oral | 14 days | Placebo | (41) |

| Fitchett et

al, 2016 | Empagliflozin | 10 or 25 mg

daily | Oral | 2.6 years | Placebo | (34) |

| Neal et al,

2017 | Canagliflozin | 100 or 300 mg

daily | Oral | 14 days | Placebo | (38) |

| Wanner et

al, 2018 | Empagliflozin | 10 or 25 mg

daily | Oral | 14 days | Placebo | (40) |

| Mahaffey et

al, 2018 | Canagliflozin | NA | NA | NA | Placebo | (37) |

| Kato et al,

2019 | Dapagliflozin | NA | NA | NA | Placebo | (36) |

| McMurray et

al, 2019 | Dapagliflozin | 10 mg daily | Oral | NA | Placebo | (48) |

| Wiviott et

al, 2019 | Dapagliflozin | 10 mg daily | Oral | NA | Placebo | (31) |

| Perkovic et

al, 2019 | Canagliflozin | 100 mg daily | Oral | NA | Placebo | (28) |

| Cannon et

al, 2020 | Ertugliflozin | 5 or 15 mg

daily | Oral | 14 days | Placebo | (33) |

| Heerspink et

al, 2020 | Dapagliflozin | 10 mg daily | Oral | 2.4 years | Placebo | (30) |

| Kosiborod et

al, 2020 | Dapagliflozin | 10 mg daily | Oral | NA | Placebo | (46) |

| Inzucchi et

al, 2020 | Empagliflozin | 10 or 25 mg

daily | Oral | 12 weeks | Placebo | (35) |

| Verma et al,

2020 | Empagliflozin | 10 or 25 mg

daily | Oral | NA | Placebo | (29) |

| Ohkuma et

al, 2020 | Canagliflozin | 100 or 300 mg

daily | Oral | NA | Placebo | (39) |

| Bhatt et al,

2021 | Sotagliflozin | 200 mg daily | Oral | NA | Placebo | (32) |

| McMurray et

al, 2021 | Dapagliflozin | 10 mg daily | Oral | NA | Placebo | (49) |

| Nassif et

al, 2021 | Dapagliflozin | NA | NA | 12 weeks | Placebo | (23) |

| Anker et al,

2021 | Empagliflozin | 10 mg daily | Oral | NA | Placebo | (42) |

| Anker et al,

2021 | Empagliflozin | 10 mg daily | Oral | NA | Placebo | (43) |

| Spertus et

al, 2022 | Canagliflozin | 100 mg | Oral | 12 weeks | Placebo | (24) |

| Kosiborod et

al, 2022 | Empagliflozin | 10 mg daily | Oral | 90 days | Placebo | (45) |

| Solomon et

al, 2022 | Dapagliflozin | 10 mg daily | Oral | NA | Placebo | (50) |

| Herrington et

al, 2023 | Empagliflozin | 10 mg daily | Oral | NA | Placebo | (26) |

| Hernandez et

al, 2024 | Empagliflozin | 10 mg daily | Oral | 14 days | Placebo | (44) |

| McMurray et

al, 2024 | Dapagliflozin | NA | NA | NA | Placebo | (47) |

| Vaduganathan et

al, 2024 | Canagliflozin | 100 or 300 mg

daily | Oral | NA | Placebo | (25) |

| Petrie et

al, 2025 | Empagliflozin | 10 mg daily | Oral | NA | Placebo | (27) |

Outcomes

Overall, the majority of the studies reported a

significant reduction in hospitalization for HF and CV-associated

mortality with the use of SGLT2i, with HR values ranging from 0.51

to 2.64, indicating consistent benefits. Similarly, these agents

also demonstrated favorable outcomes in reducing all-cause

mortality, although a number of studies reported a neutral impact

in reducing these CV-mortality outcomes (33,50).

In addition, myocardial infarction rates (in studies that reported

them) also demonstrated a non-significant difference (31,33,38,41)

between the SGLT2i and placebo groups. However, quality of life was

improved after the administration of SGLT2i agents, as observed

through improved scores based on the KCCQ (Table III). A wide range was observed in

the follow-up duration of these trials, with most studies having

reported >1 year of follow-up (26-28,30,33,34,36,38,41,42,44,47,48)

and one study following up for <1 year (32). The most commonly occurring adverse

events associated with SGLT2i were genital mycotic infections,

urinary tract infections, volume depletion/hypotension, acute

kidney injury (AKI), lower limb amputation, severe hypoglycemia,

ketoacidosis and hypovolemia (Table

III). Overall, these results consistently supported the

efficacy and safety of SGLT2i in improving HF-associated outcomes

in patients with or without diabetes.

| Table IIISummary of outcomes associated with

the application of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors. |

Table III

Summary of outcomes associated with

the application of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors.

| | Outcomes | |

|---|

| First author,

year | Hospitalization for

total HF | CV mortality | All-cause

mortality | Myocardia

infraction | QoL (KCCQ) | Follow-up | Adverse events | Conclusion | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Zinman et

al, 2015 | 0.65 (95% CI:

0.50-0.85) | 0.62 (95% CI:

0.49-0.77) | 0.68 (95% CI:

0.57-0.82) | 0.87 (95% CI:

0.70-1.09) | NA | 206 weeks | UTI | Empagliflozin was

found effective in reducing primary CV outcomes | (41) |

| Fitchett et

al, 2016 | 0.65 (95% CI:

0.50-0.85) | 0.66 (95% CI:

0.55-0.79) | 0.68 (95% CI:

0.57-0.82) | NA | NA | 3.1 years | Adverse events

occurred in both groups, like hypoglycemia | Empagliflozin

effectively reduced HF hospitalization and CV mortality | (34) |

| Neal et al,

2017 | NA | 0.87 (95% CI:

0.72-1.06) | 0.87 (95% CI:

0.74-1.01) | 0.86 (95% CI:

0.75-0.97) | NA | 188.2 weeks | Volume depletion,

kidney problems, diuresis | Canagliflozin

successfully lowered the risk of CV events | (38) |

| Wanner et

al, 2018 | 0.61 (95% CI:

0.42-0.87) | 0.71 (95% CI:

0.52-0.98) | 0.76 (95% CI:

0.59-0.99) | NA | NA | NA | Acute renal

failure, bone fracture, lower limb amputation and hyperkalemia | Empagliflozin

improved clinical outcomes | (40) |

| Mahaffey et

al, 2018 | 2.64 (95% CI:

1.90-3.65) | 2.51 (95% CI:

1.99-3.16) | 1.86 (95% CI:

1.57-2.22) | NA | NA | NA | Amputations,

genital infections, fractures, volume depletion and renal adverse

events | Canagliflozin

reduced CV outcomes | (37) |

| Kato et al,

2019 | 0.64 (95% CI:

0.43-0.95) | 0.55 (95% CI:

0.34-0.90) | 0.59 (95% CI:

0.40-0.88) | NA | NA | 4.2 years | Major hypoglycemia,

amputation, diabetic ketoacidosis, fracture, acute renal failure,

genital infection, urinary tract infection | Dapagliflozin

reduced CV outcomes | (36) |

| McMurray et

al, 2019 | 0.70 (95% CI:

0.59-0.83) | 0.82 (95% CI:

0.69-0.98) | 0.83 (95% CI:

0.71-0.97) | NA | NA | 18.2 months | Renal dysfunction,

hypoglycemia and volume depletion | Dapagliflozin

reduced HF in patients with and without diabetes | (48) |

| Wiviott et

al, 2019 | 0.73 (95% CI:

0.61-0.88) | 0.83 (95% CI:

0.73-0.95) | 0.93 (95% CI:

0.82-1.04) | 0.89 (95% CI:

0.77-1.01) | NA | 4.2 years | Renal failure and

ketoacidosis | Dapagliflozin did

not result in a higher or lower rate of MACE than placebo but did

result in a lower rate of CV mortality or hospitalization for

HF | (31) |

| Perkovic et

al, 2019 | 0.61 (95% CI:

0.47-0.80) | 0.78 (95% CI:

0.61-1.00) | 0.83 (95% CI:

0.68-1.02) | NA | NA | 2.62 years | Amputation,

fracture, renal cell carcinoma, bladder and breast cancer, acute

pancreatitis | Canagliflozin was

found to be effective in reducing cardiovascular events and kidney

failure events | (28) |

| Cannon et

al, 2020 | 0.70 (95% CI:

0.54-0.90) | 0.92 (95.8% CI:

0.77-1.11) | 0.93 (95% CI:

0.80-1.08) | 1.04 (95% CI:

0.86-1.27) | NA | 3.5 years | Amputation, UTI,

genital mycotic infection, hypovolemia, AKI and diabetic

ketoacidosis | Ertugliflozin was

non-inferior to placebo with respect to MACE | (33) |

| Heerspink et

al, 2020 | NA | 0.71 (95% CI:

0.55-0.92 | NA | NA | NA | 2.4 years | Amputation,

fracture, renal failure and volume depletion | Dapagliflozin

markedly reduced CV outcomes | (30) |

| Kosiborod et

al, 2020 | NA | 0.70 (95% CI:

0.57-0.86) | NA | NA | 2.8-point

improvement (intervention) | 12 months | NA | Dapagliflozin

reduced CV mortality and worsening HF across the range of baseline

KCCQ | (46) |

| Inzucchi et

al, 2020 | 1.91 (95% CI:

0.96-3.79) | 4.00 (95% CI:

2.26-7.11) | NA | NA | NA | NA | Non-fatal

myocardial infarction, non-fatal stroke | Empagliflozin

effectively improved CV outcomes | (35) |

| Verma et al,

2020 | 0.53 (95% CI:

0.28-1.01) | 0.75 (95% CI:

0.48-1.18) | 0.68 (95% CI:

0.48-0.97) | NA | NA | NA | UTI, volume

depletion and acute renal failure | Empagliflozin

reduced CV outcomes | (29) |

| Ohkuma et

al, 2020 | 0.67 (95% CI:

0.52-0.87) | 0.87 (95% CI:

0.72-1.06) | NA | NA | NA | NA | Amputation,

fractures, infection, serious hyperkalemia, diabetic

ketoacidosis | Canagliflozin

improved CV outcomes | (39) |

| Bhatt et al,

2021 | 0.64 (95% CI:

0.49-0.83) | 0.84 (95% CI:

0.58-1.22) | 0.82 (95% CI:

0.59-1.14) | NA | 4.10 (95% CI:

1.3-7.00) | 9 months | Diarrhea, severe

hypoglycemia, hypotension and AKI | Sotagliflozin

therapy markedly lowered CV mortality and hospitalizations | (32) |

| McMurray et

al, 2021 | 0.51 (95% CI:

0.34-0.76) | 0.68 (95% CI:

0.44-1.05) | 0.56 (95% CI:

0.34-0.93) | NA | NA | 2.4 years | Amputation,

fracture, renal adverse events, major hypoglycemia, volume

depletion | Dapagliflozin

reduced the risk of CV mortality and HF hospitalization | (49) |

| Nassif et

al, 2021 | NA | NA | Intervention group

(0.6%) and control group (1.2%) | NA | 5.8 points (95% CI:

2.3-9.2) | 12 weeks | AKI, volume

depletion and hypoglycemic events, lower limb amputation | Dapagliflozin

markedly improved patient-reported symptoms | (23) |

| Anker et al,

2021 | 0.73 (95% CI:

0.61-0.88) | 0.91 (95% CI:

0.76-1.09) | 1.00 (95% CI:

0.87-1.15) | NA | HR=1.32 (95% CI:

0.45-2.19) | 26.2 months | Uncomplicated

genital infections, UTI and hypotension were reported more

frequently in the intervention group | Empagliflozin

reduced the combined risk of CV mortality or hospitalization for

HF | (42) |

| Anker et al,

2021 | 0.70 (95% CI:

0.58-0.85) | 0.75 (95% CI:

0.65-0.86) | NA | NA | Difference in

change: 1.75 (95% CI: 0.5-3.0) | NA | Hypotension, volume

depletion, hypoglycemic events, ketoacidosis and lower limp

amputation | Empagliflozin

markedly improved CV and renal outcomes | (43) |

| Spertus et

al, 2022 | NA | NA | NA | NA | KCCQ TSS change:

4.3 points (95% CI: 0.8-7.8) higher in the intervention group | 12 weeks | Infections,

hypotension, increased urination | Canagliflozin

markedly improves symptom burden in HF, regardless of ejection

fraction or diabetes status | (24) |

| Kosiborod et

al, 2022 | NA | NA | NA | NA | Corrected

difference: 1.36 win ratio (95% CI: 1.09-1.68) | 90 days | NA | Empagliflozin

markedly improved symptoms, physical limitations and QoL | (45) |

| Solomon et

al, 2022 | 0.82 (95% CI:

0.73-0.92) | 0.88 (95% CI:

0.74-1.05) | 0.94 (95% CI:

0.83-1.07) | NA | Corrected

difference: 2.4 points (95% CI: 1.5-3.4) | 2.3 years | Amputation,

hypergly cemic events, ketoacidosis and volume depletion | Dapagliflozin

reduced the risk of worsening HF or CV mortality | (50) |

| Herrington et

al, 2023 | NA | 0.84 (95% CI:

0.60-1.19) | 0.87 (95% CI:

0.70-1.08) | NA | NA | 2 years | UTI, genital

infection, hyperkalemia, AKI, liver injury, lower limb amputation,

fractures and severe hypoglycemia | Empagliflozin was

found to be effective for reducing risk of progression of kidney

diseases and cardiovascular deaths | (26) |

| Hernandez et

al, 2024 | First intervention

group (118/3,260) and control group (153/3, 262); total inter

vention group (148/3, 260) and control group (207/3,262) | Intervention group

(280/3,260) and control group (338/3,262) | Intervention group

(20/3,260) and control group (30/3,262) | NA | NA | 17.9 months | Intervention group,

cardiac failure and cardiogenic shock; control group, cardiac

failure, cardiogenic shock and acute pulmonary edema | Empagliflozin

reduced the risk of HF | (44) |

| McMurray et

al, 2024 | NA | NA | NA | NA | KCCQ-TSS corrected

difference after 16 weeks: 4.2 (95% CI:1.0-8.2) favoring

dapagliflozin; KCCQ-PLS: 4.2 (95% CI: 0.0-8.3) | 16 weeks | Adverse events

occurred in both groups | Dapagliflozin

improved the KCCQ-TSS in patients with HF with reduced ejection

fraction, but did not improve KCCQ-PLS | (47) |

| Vaduganathan et

al, 2024 | Intervention group

(304) and control group (368) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 2.5 years | NA | Canagliflozin

reduced the total burden of HF hospitalizations | (25) |

| Petrie et

al, 2025 | First HR=0.77 (95%

CI: 0.60-0.98); total HR=0.67 (95% CI: 0.50-0.89) | NA | HR=0.96 (95% CI:

0.78-1.19) | NA | NA | 17.9 months | AKI, hypotension,

volume depletion, hypoglycemia, hepatic injury and

ketoacidosis | Empagliflozin

reduced first and total HF hospitalizations | (27) |

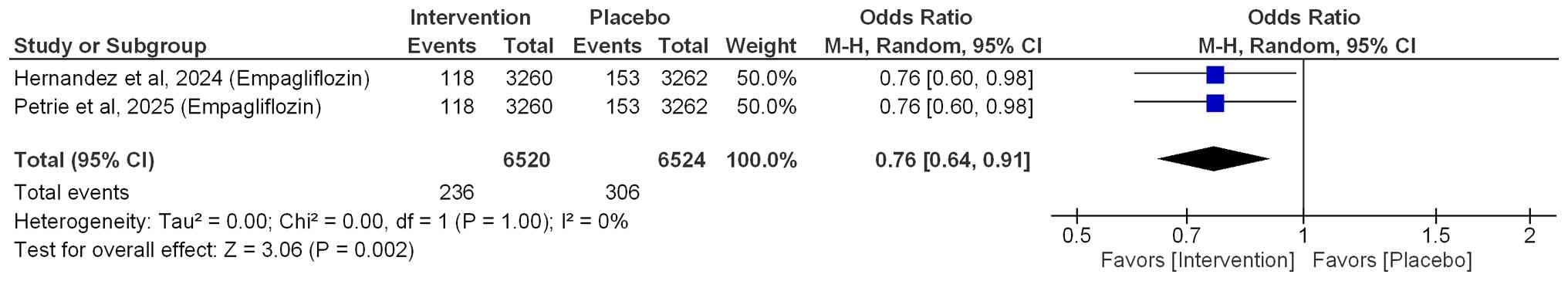

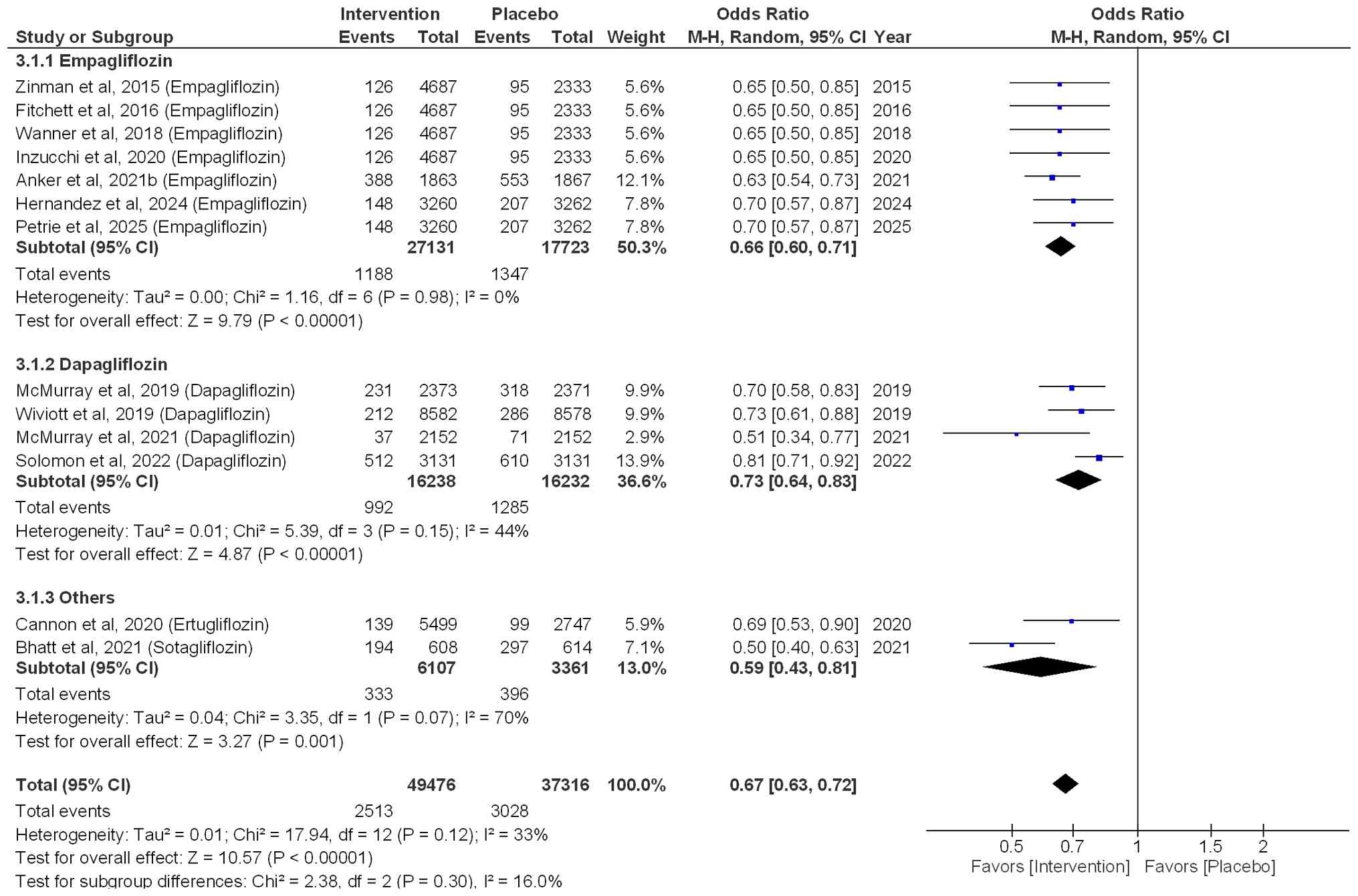

Hospitalization for HF

Among patients with HF who had diabetes and were

treated with empagliflozin, the risk of first hospitalization for

HF was significantly reduced by 24% (OR=0.76; 95% CI: 0.64-0.91;

P=0.002; I²=0%; Fig. 2). In

addition, the risk of hospitalization for total HF was reduced by

34% (OR=0.66; 95% CI: 0.60-0.71; P<0.00001; I²=0%), when

patients were treated with empagliflozin. Similarly, a significant

reduction of 27% (OR=0.73; 95% CI: 0.64-0.83; P<0.00001) was

observed when patients were treated with dapagliflozin, with

moderate heterogeneity (I2=44%). In addition, other

SGLT2i, such as ertugliflozin and sotagliflozin, also resulted in a

significant reduction of 41% in the risk of hospitalization for HF

(OR=0.59; 95% CI: 0.43-0.81; P=0.001), with a notable heterogeneity

(I2=70%). Overall, the pooled effect size (OR=0.67; 95%

CI: 0.63-0.72; P<0.00001; I²=33%) indicated that SGT2i

effectively reduced the risk of hospitalization for HF by 33%, as

shown in Fig. 3.

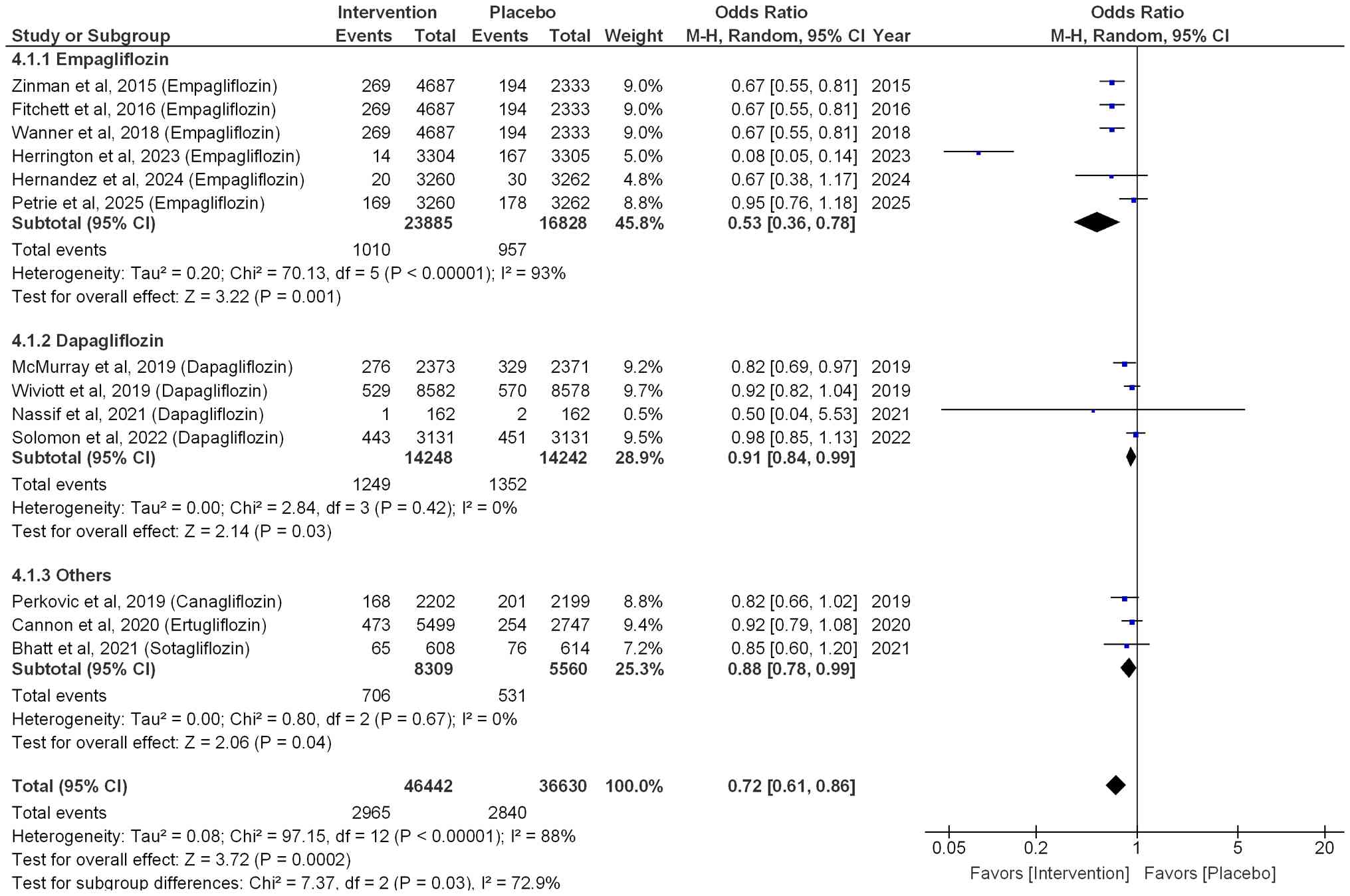

All-cause mortality and CV

mortality

Among patients with HF who had diabetes,

empagliflozin significantly reduced the risk of all-cause mortality

by 47% (OR=0.53; 95% CI: 0.36-0.78; P=0.001; I²=93%; Fig. 4). Dapagliflozin also resulted in a

significant reduction in all-cause mortality by 9% (OR=0.91; 95%

CI: 0.84-0.99; P=0.03; I2=0%). Other SGLT2i, such as

sotagliflozin, ertugliflozin and canagliflozin, also led to a

significant reduction in all-cause mortality by 12% (OR=0.88; 95%

CI: 0.78-0.99; P=0.04, I2=0%). Overall, a 28% reduction

was observed in all-cause mortality when patients were treated with

SGLT2i (OR=0.72; 95% CI: 0.61-0.86; P=0.0002; I2=88%),

as illustrated in Fig. 4.

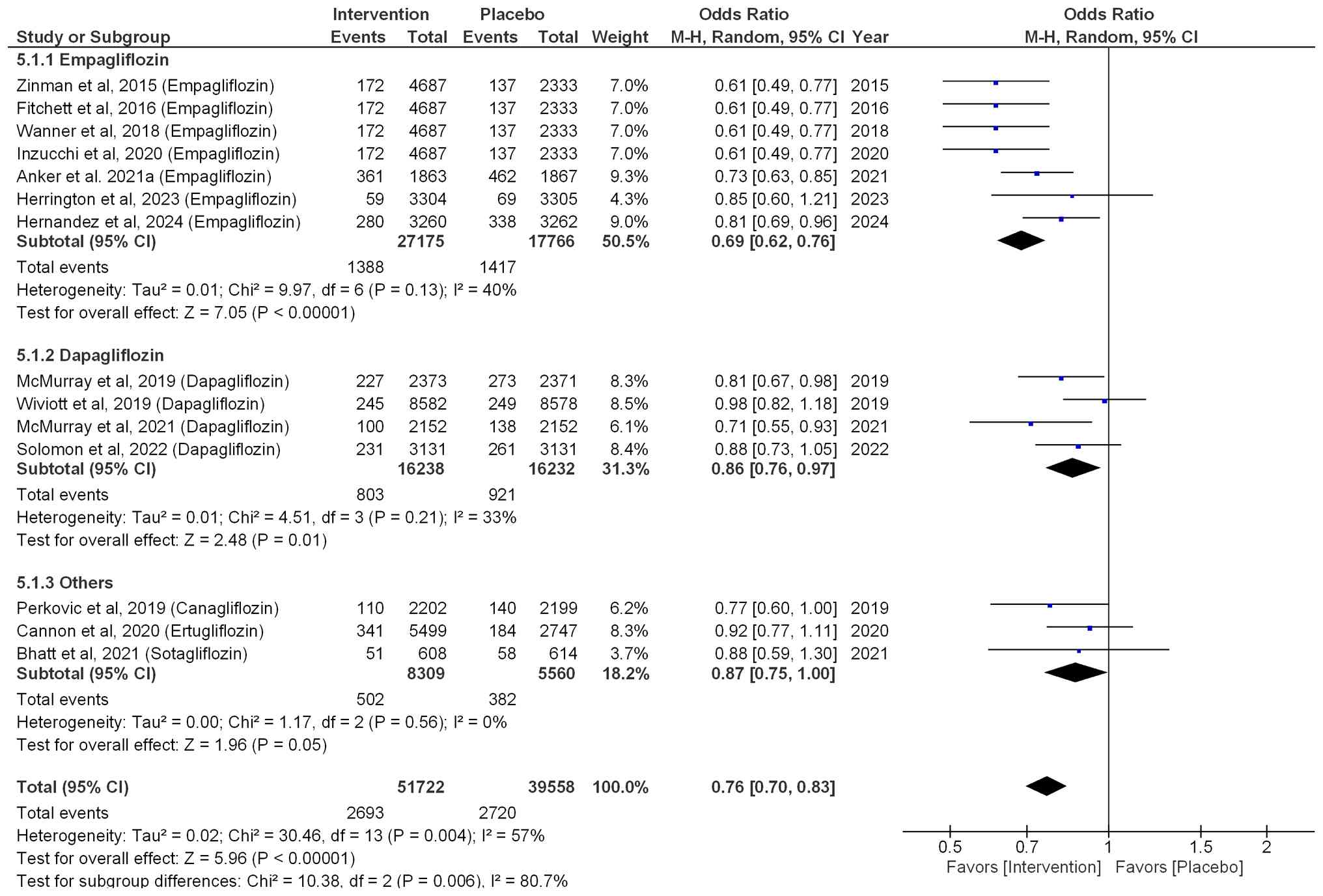

Similarly, regarding CV mortality, the risk was

reduced by 31% (OR=0.69; 95% CI: 0.62-0.76; P<0.00001; I²=40%)

when patients were treated with empagliflozin. Patients treated

with dapagliflozin exhibited a significant 14% reduction in

CV-associated mortality (OR=0.86; 95% CI: 0.76-0.97; P=0.01;

I2=33%). Similarly, patients treated with other SGLT2i

(sotagliflozin, ertugliflozin and canagliflozin) exhibited a

non-significant 13% reduction (OR=0.87; 95% CI: 0.75-1.00; P=0.05;

I2=0%). Overall, the pooled effect size (OR=0.76; 95%

CI: 0.70-0.83; P<0.00001; I²=57%) indicated that SGLT2i

effectively reduced the risk of CV-associated mortality by 24%, as

shown in Fig. 5.

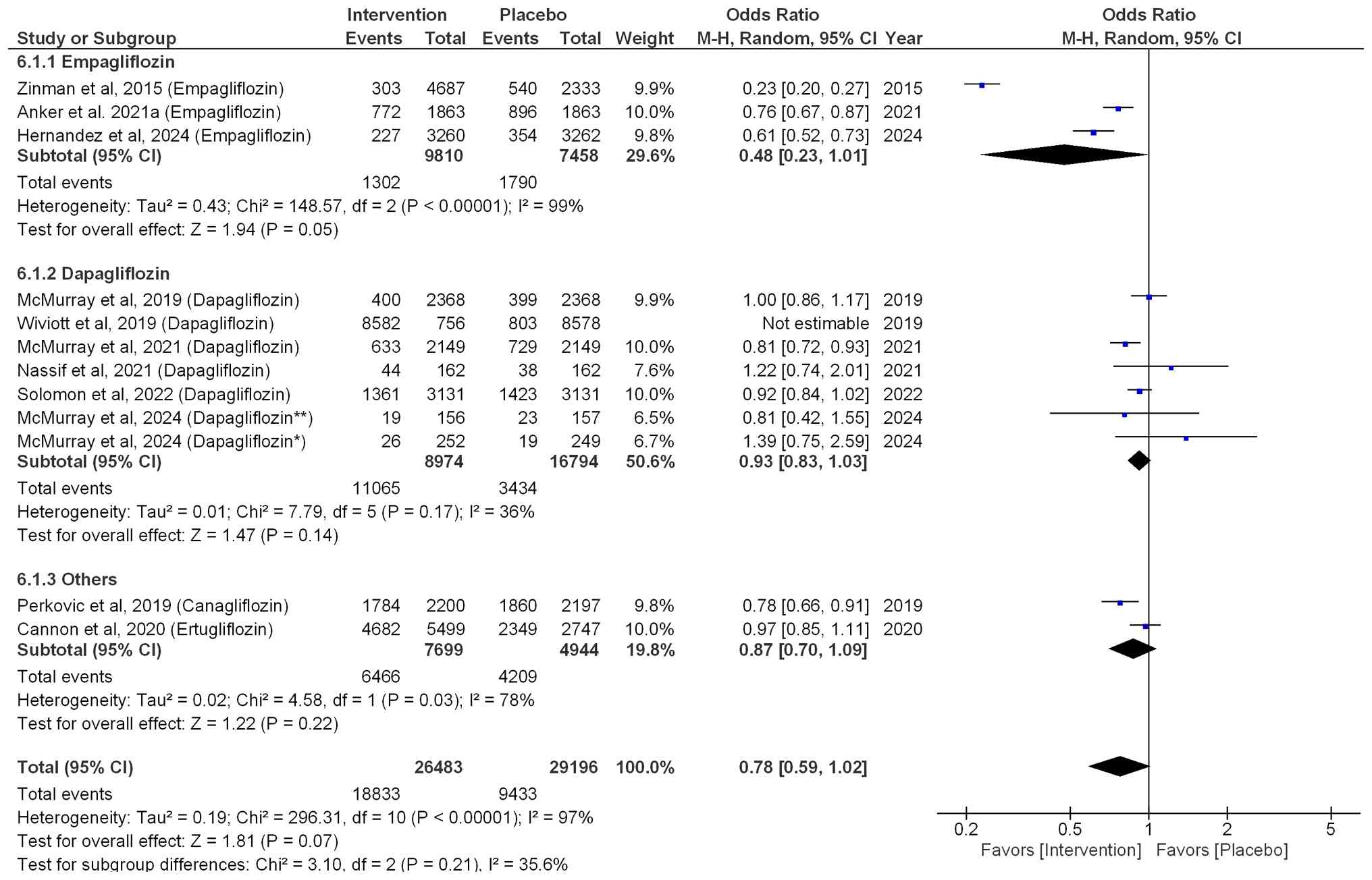

Adverse events

Within the empagliflozin treatment group, a

non-significant 52% reduction in the risk of adverse events was

demonstrated (OR=0.48; 95% CI: 0.23-1.01; P=0.05;

I2=99%). Dapagliflozin (OR=0.93; 95% CI: 0.83-1.03;

P=0.14; I2=36%) and other SGLT2i, such as ertugliflozin

and ertugliflozin (OR=0.87; 95% CI: 0.70-1.09; P=0.22;

I2=78%), did not significantly reduce the risk of

adverse events compared with that in the placebo group. Overall,

the pooled effect size for adverse events (OR=0.78; 95% CI:

0.59-1.02; P=0.07; I2=97%), indicated that SGLT2i

non-significantly reduced the risk of adverse events by 22%

compared with that in the placebo group (Fig. 6).

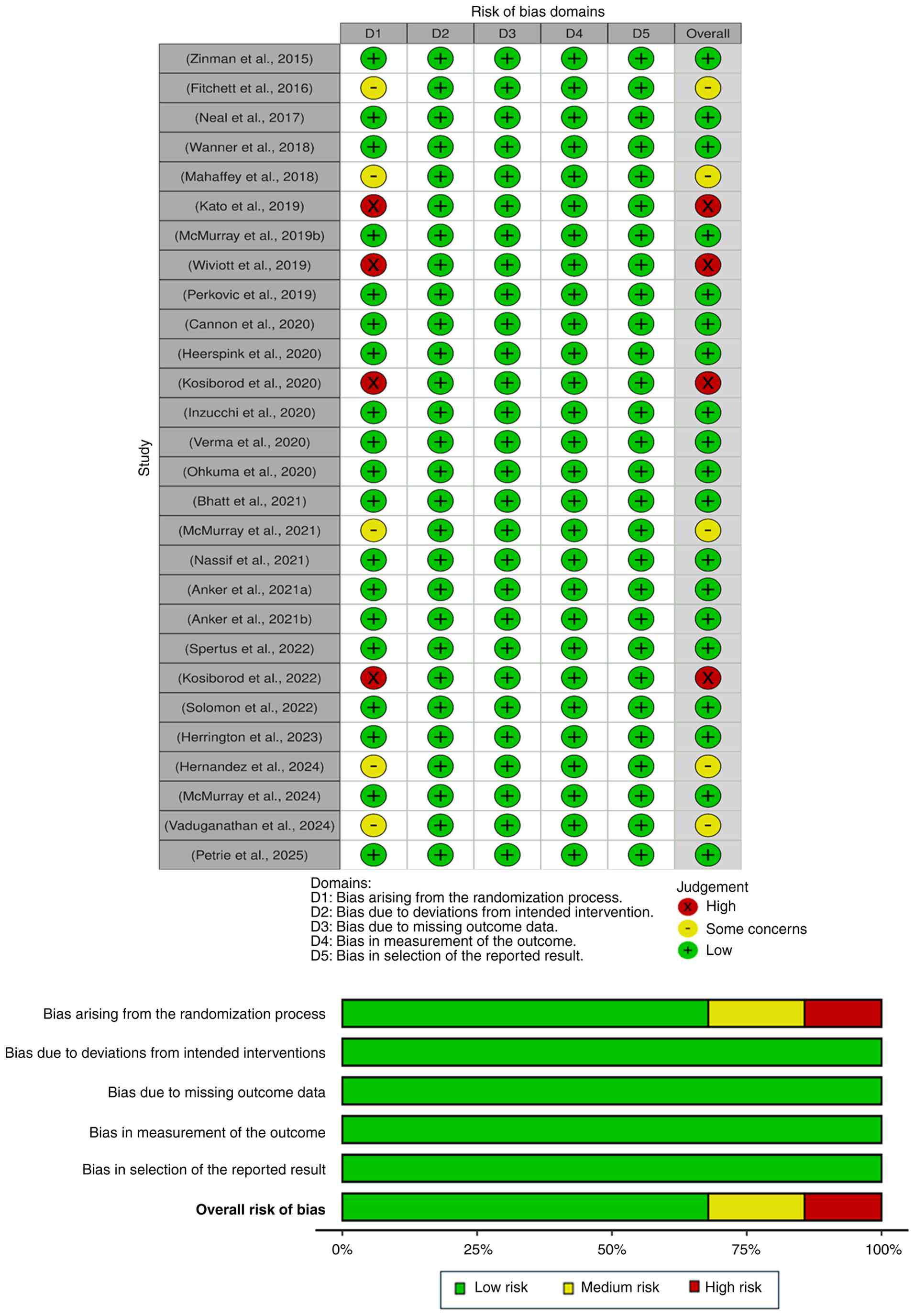

Methodological quality assessment

Overall, the majority of included studies exhibited

a low risk of bias in the randomization process, deviations from

intended interventions, missing outcome data, measurement of the

outcome and reporting results domains. However, a total of 4

studies exhibited a high risk of bias in the randomization domain

(31,36,45,46),

while 5 studies exhibited some concerns in the randomization domain

(25,34,37,44,49),

as illustrated in Fig. 7.

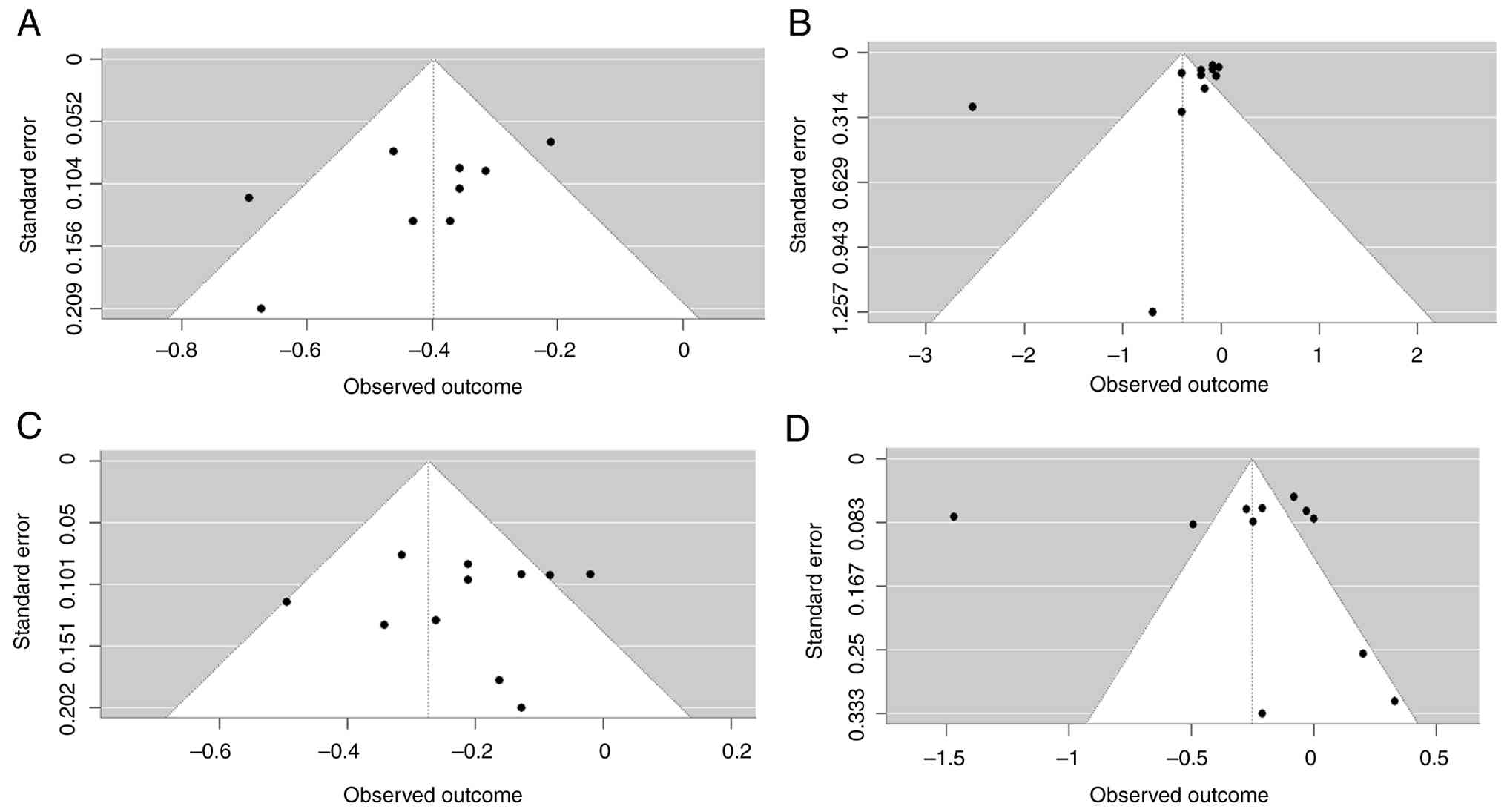

Publication bias

The Egger's regression test for publication bias

regarding the first hospitalization for HF was not performed due to

the presence of <10 studies. However, for total hospitalization

for HF (t=-2.21; P=0.048), the distribution of studies appeared

relatively asymmetrical around the effect size line, suggesting a

high publication bias (Fig. 8A).

On the other hand, the distribution of studies for all-cause

mortality (t=-2.10; P=0.058), CV-associated mortality (t=-0.72;

P=0.479) and adverse events (t=-0.01; P=0.988) appeared relatively

symmetrical around the effect size line, suggesting a low

publication bias (Fig. 8B-D).

Source of heterogeneity

However, despite efforts to further investigate

potential sources of heterogeneity, the available data did not

allow more conclusive results to be drawn, as the included studies

did not provide sufficient association data to evaluate the sources

of heterogeneity (such as the impact of age and sex of patients,

drug type, comorbidities, diabetes status and follow-up durations

on the outcomes). As a result, the sources of heterogeneity could

not be examined further despite a number of studies providing basic

demographic information, including age and sex.

Certainty of evidence

Outcomes, including the impact of SGLT2i on

hospitalization for HF (first and total), mortality (all-cause and

CV-associated) and adverse events in patients with or without

diabetes, were assessed in the domain of risk of bias,

inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision and publication bias.

Total hospitalization for HF, all-cause mortality and adverse

events were assessed in these domains and rated with low certainty

due to the presence of high heterogeneity and publication bias,

while, CV-associated mortality had moderate certainty due to

moderate heterogeneity. Furthermore, a high certainty was present

for the first hospitalization for HF, which may be due to the

limited number of studies, as publication bias test could not be

assessed (Table IV).

| Table IVSummary of the certainty of

evidence. |

Table IV

Summary of the certainty of

evidence.

| Outcomes | Number of

studies | RoB | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Publication

bias | Effect size

(OR) | Certainty of

evidence |

|---|

| First

hospitalization for HF | Empagliflozin

(n=2) | Low to some

concerns | Not serious

(I2=0%) | Not serious | Not serious | Not assessed | 0.76 (95% CI:

0.64-0.91) | High ƟƟƟƟ |

| Total

hospitalization for HF | Empagliflozin

(n=7), dapagliflozin (n=4) and others (n=2) | Low to high | Partially serious

(I2=33%) | Not serious | Not serious | Present | 0.67 (95% CI:

0.63-0.72) | Low Ɵ |

| All-cause

mortality | Empagliflozin

(n=6), dapagliflozin (n=4) and others (n=3) | Low to high | Serious

(I2=88%) | Not serious | Not serious | Absent | 0.72 (95% CI:

0.61-0.86) | Low Ɵ |

| CV-associated

mortality | Empagliflozin

(n=7), dapagliflozin (n=4) and others (n=3) | Low to high | Serious

(I2=57%) | Not serious | Not serious | Absent | 0.76 (95% CI:

0.70-0.83) | Moderate ƟƟƟ |

| Adverse events | Empagliflozin

(n=3), dapagliflozin (n=7) and others (n=2) | Low to high | Serious

(I2=97%) | Not serious | Not serious | Absent | 0.78 (95% CI:

0.59-1.02) | Low Ɵ |

Discussion

Encompassing data from 28 studies, the present

comprehensive meta-analysis provided robust evidence regarding the

clinical benefits of SGLT2i across diabetic and non-diabetic

populations with HF. The outcomes of the present meta-analysis

indicated that SGLT2i were significantly associated with a relative

risk reduction in the composite endpoint of first and total

hospitalizations for HF in patients with and without diabetes by 24

and 33%, respectively. Similarly, pooled analysis for all-cause

mortality and CV-associated mortality also demonstrated a

significantly reduced risk in patients treated with SGLT2i by 28

and 24%, respectively. In addition, the risk of adverse events was

reduced by 22% in the SGLT2i-treated intervention group compared

with that in the placebo group; however, this result was not

significant. Furthermore, the majority of studies exhibited a low

risk of bias, except for a small number of studies, which exhibited

a high risk of bias or some concerns in the randomization process.

This was due to these studies not mentioning or explaining the

process used for randomization. For example, these studies

(31,36,45,46)

did not use a computer-generated randomization process or any other

standard procedure, like random number generators, flip coin

method, or block randomization. This may have influenced the

reliability of the pooled estimates, thereby underestimating the

true effect of treatment. However, most overall outcomes were found

without any publication bias, except for total hospitalizations,

which likely reflects an over-representation of studies reporting

significant reductions in total hospitalizations, while studies

with non-significant outcomes may remain unpublished or less

accessible. Due to this reason, positive findings may skew the

pooled effect estimate, indicating treatment to be more effective

than the true effect estimates if non-significant outcomes were

included. Therefore, the total hospitalization outcome in

particular should be interpreted with caution.

The present findings align with those of a previous

meta-analysis, which included 15 studies and observed a 29%

(HR=0.71; 95% CI: 0.67-0.77) reduction in the risk of first

hospitalization for HF in patients with diabetes treated with

SGLT2i. Similarly, CV-associated mortality was also reduced by 14%

(HR=0.86; 95% CI: 0.79-0.93) (51). The main difference between the

present study and this previous meta-analysis was the larger number

of studies being included in the present analysis, making it more

reliable. In addition, another difference was the inclusion of both

diabetic and non-diabetic patients in the present study. Similarly,

another previous meta-analysis included 8 studies, observing a

reduced relative risk in CV-associated mortality and HF

hospitalizations by 20% (52). The

main difference between this study and the present meta-analysis is

both the number of studies included in the analysis and the

parameters examined, such as adverse events, and all-cause

mortality. Greene et al (53) demonstrated that diabetic and

non-diabetic patients with HF exhibit an annual mortality rate of

8-10%, even in the presence of sTable symptoms. In addition, nearly

one in four patients either succumb to the disease or are

re-hospitalized within 30 days of a previous hospitalization for

HF. These findings provide support for the use of SGLT2i in

reducing both hospitalization for HF and CV mortality in this

population. Although absolute event rates varied across the trials,

from ~35 per 1,000 patient-years in the EMPA-REG OUTCOME (41), CANVAS (38) and EMPEROR-preserved trials to

>120 per 1,000 patient-years in the SOLOIST-WHF trial, low

heterogeneity in the treatment effects suggests the applicability

of these findings across a wide risk spectrum (32).

The benefits of SGLT2i are likely multifactorial and

may include favorable effects on cardiac remodeling. In addition,

in patients with diabetes, SGLT2i were found to be effective in

reducing both first and total hospitalizations for HF and in

reducing all-cause and CV-associated mortality. Diabetes has been

shown to significantly elevate the HF risk by ~2-fold in men and

5-fold in women (54). The

observed benefits in these patients appear to be largely

independent of glycemic control, as the outcomes did associate with

the changes in HbA1c across the trial (55). Instead, these effects may be

attributable to cardiorenal (55)

and systemic hemodynamic mechanisms (56). Within this bidirectional

pathophysiologic relationship, use of SGLT2i emerges as a safe and

effective therapeutic strategy.

Furthermore, a 22% reduction in adverse events was

observed in the SGLT2i-treated groups in the present study, which

is consistent with another recent meta-analysis showing that SGLT2i

markedly reduced the risk of kidney disease progression and AKI

across a broad spectrum of renal functions (diabetic kidney disease

or nephropathy, ischemic and hypertensive kidney disease),

irrespective of T2DM status (57).

SGLT2i can improve CV-associated outcomes by blocking glucose and

sodium reabsorption in the proximal renal tubules, causing

increased urinary excretion of both glucose and sodium, which

reduces preload and afterload through natriuresis and diuresis,

lowering interstitial fluid volume without notable electrolyte loss

or disturbance (58). This

reduction in sodium reabsorption also reduces renal oxygen demand

and improves tubuloglomerular feedback by reabsorption in the

proximal tubule, increasing sodium delivery to the macula densa and

contributing to improved heart function (59). In addition, SGLT2i also enhances

myocardial energy efficiency, and reduces fibrosis by

downregulating pro-inflammatory pathways (IL-6, TNF-alpha), cardiac

inflammation and oxidative stress whilst improving endothelial

function, collectively leading to reduced hospitalization and

mortality rates in both populations exhibiting HF with reduced

ejection fraction and HF with preserved ejection fraction (60). SGLT2i improve glycemic control and

reduce glucotoxicity in diabetic patients, while in non-diabetic

patients, the mechanisms are primarily hemodynamic and metabolic,

independent of glucose lowering (61,62).

Low-to-high heterogeneity was observed in the

present meta-analysis, which can be attributed to a number of

reasons. For example, baseline LVEF and presence of comorbidities,

such as CKD, are critical modifiers of the treatment response. In

the present study, these factors were not considered due to the

unavailability of uniform data for performing subgroup analysis.

These factors suggest that the response of patients with reduced

and preserved ejection fraction towards treatment may be different,

with studies indicating greater relative benefits in HF with

reduced ejection fraction (51,63).

Similarly, CKD severity can also markedly affect both the efficacy

and safety of SGLT2i, as renal function impacts drug

pharmacodynamics and the associated metabolic responses (64).

The findings of the present meta-analysis may have

important clinical implications for the management of HF in

patients with or without diabetes, as a significant reduction in

the risk of hospitalizations for HF, mortality and adverse events

was observed in the SGLT2i-treated groups. These outcomes strongly

suggest the routine incorporation of SGLT2i into HF treatment

protocols for both diabetic and non-diabetic patients.

The present study exhibits a number of strengths,

such as the inclusion of a large number of RCTs with diverse

populations from across the globe, enhancing the generalizability

of the present findings across both diabetic and non-diabetic

patients with HF. In addition, the present study also focused on

key outcomes, such as first and total hospitalizations for HF,

all-cause mortality, CV mortality and adverse events associated

with the administration of SGLT2i. Another strength may lie in the

inclusion of studies with a low risk of bias. However, certain

limitations should be considered during interpretation of the

results. Firstly, high heterogeneity was observed among the

studies, which can affect the generalizability of the outcomes.

This may have been due to the included population, as in certain

studies only diabetic patients were considered, while in other

studies, both diabetic and non-diabetic patients were included. The

heterogeneity may have also been impacted by the exclusion of

non-English studies. Another limitation may be the administration

of varying SGLT2i with different dosages and follow-up durations,

which were found to be non-consistent across all studies. Secondly,

a meta-analysis could not be performed regarding the impact of LVEF

and comorbidities such as CKD, due to the unavailability of

consistent data, which may have influenced the outcomes of the

present study. Thirdly, subgroup analysis between diabetic and

non-diabetic patients could not be performed, as HR values were

presented as composite measures that combined different clinical

outcomes (such as HF hospitalization and mortality), making them

unsuitable for pooling in a meaningful or methodologically sound

subgroup analysis. In addition, the reporting across studies lacked

sufficient consistency in outcome definitions (assessment tools

used for assessment of clinical outcomes, like hospitalization) and

stratification, further limiting the feasibility of combining these

data. Therefore, incorporating composite HRs that merge numerous

endpoints would affect or compromise the clarity and validity of

the present findings. Future studies are required to elucidate the

general understanding of the cardioprotective mechanisms and

long-term safety of SGLT2i.

In conclusion, the findings of the present

meta-analysis provided marked evidence that SGLT2i significantly

reduce the risk of first and total hospitalizations for HF,

all-cause mortality and CV mortality in both diabetic and

non-diabetic patients with HF. However, a non-significant reduction

in adverse events was observed. The consistent benefits

demonstrated across a wide range of clinical outcomes and

populations highlight the therapeutic importance of SGLT2i as a

treatment in HF management, supporting their clinical relevance and

routine use in improving outcomes. Future meta-analyses should aim

to focus on broader HF populations, including those with preserved

ejection fraction and numerous comorbidities. In addition, the

mechanism behind the cardioprotective impact of SGLT2i in

non-diabetic patients should be examined.

Supplementary Material

Literature search strategy from

different databases.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

DAB and NHA conceptualized and designed the present

study, contributed to data analysis, interpretation and curation,

created graphs, contributed to the interpretation of results and

served a key role in writing the manuscript. DAB and NHA confirm

the authenticity of all the raw data. Both authors have read and

approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Savarese G, Becher PM, Lund LH, Seferovic

P, Rosano GMC and Coats AJS: Global burden of heart failure: A

comprehensive and updated review of epidemiology. Cardiovasc Res.

118:3272–3287. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Sheraliev A: Pathophysiology of heart

failure, hemodynamic changes and their consequences. Mod Sci Res.

4:965–969. 2025.

|

|

3

|

Ran J, Zhou P, Wang J, Zhao X, Huang Y,

Zhou Q, Zhai M and Zhang Y: Global, regional, and national burden

of heart failure and its underlying causes, 1990-2021: Results from

the global burden of disease study 2021. Biomark Res.

13(16)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Dini FL, Pugliese NR, Ameri P, Attanasio

U, Badagliacca R, Correale M, Mercurio V, Tocchetti CG, Agostoni P

and Palazzuoli A: Heart Failure Study Group of the Italian Society

of Cardiology. Right ventricular failure in left heart disease:

From pathophysiology to clinical manifestations and prognosis.

Heart Fail Rev. 28:757–766. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Shah P, Pellicori P, Cuthbert J and Clark

AL: Pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment for

decompensated heart failure: What is new? Curr Heart Fail Rep.

14:147–157. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Shahim B, Kapelios CJ, Savarese G and Lund

LH: Global public health burden of heart failure: An updated

review. Card Fail Rev. 9(e11)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Talha KM, Anker SD and Butler J: SGLT-2

inhibitors in heart failure: A review of current evidence. Int J

Heart Fail. 5(82)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Salvatore T, Pafundi PC, Galiero R,

Albanese G, Di Martino A, Caturano A, Vetrano E, Rinaldi L and

Sasso FC: The diabetic cardiomyopathy: The contributing

pathophysiological mechanisms. Front Med (Lausanne).

8(695792)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Chen J, Jiang C, Guo M, Zeng Y, Jiang Z,

Zhang D, Tu M, Tan X, Yan P, Xu X, et al: Effects of SGLT2

inhibitors on cardiac function and health status in chronic heart

failure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cardiovasc

Diabetol. 23(2)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Vasquez-Rios G and Nadkarni GN: SGLT2

inhibitors: Emerging roles in the protection against cardiovascular

and kidney disease among diabetic patients. Int J Nephrol Renovasc

Dis. 13:281–296. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Singh J: A Comprehensive Analysis of

SGLT2-inhibition in Type 2 Diabetes and Heart Failure. University

of Dundee, 2019.

|

|

12

|

Fernandes GC, Fernandes A, Cardoso R,

Penalver J, Knijnik L, Mitrani RD, Myerburg RJ and Goldberger JJ:

Association of SGLT2 inhibitors with arrhythmias and sudden cardiac

death in patients with type 2 diabetes or heart failure: A

meta-analysis of 34 randomized controlled trials. Heart rhythm.

18:1098–1105. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Treewaree S, Kulthamrongsri N,

Owattanapanich W and Krittayaphong R: Is it time for class I

recommendation for sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors in

heart failure with mildly reduced or preserved ejection fraction?:

An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Cardiovasc

Med. 10(1046194)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

McMurray JJV, DeMets DL, Inzucchi SE,

Køber L, Kosiborod MN, Langkilde AM, Martinez FA, Bengtsson O,

Ponikowski P, Sabatine MS, et al: The dapagliflozin and prevention

of Adverse-outcomes in heart failure (DAPA-HF) trial: Baseline

characteristics. Eur J Heart Fail. 21:1402–1411. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Packer M, Butler J, Zannad F, Filippatos

G, Ferreira JP, Pocock SJ, Carson P, Anand I, Doehner W, Haass M,

et al: Effect of empagliflozin on worsening heart failure events in

patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction:

EMPEROR-preserved trial. Circulation. 144:1284–1294.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Gao M, Bhatia K, Kapoor A, Badimon J,

Pinney SP, Mancini DM, Santos-Gallego CG and Lala A: SGLT2

inhibitors, functional capacity, and quality of life in patients

with heart failure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA

Netw Open. 7(e245135)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Savarese G, Butler J, Lund LH, Bhatt DL

and Anker SD: Cardiovascular effects of non-insulin

glucose-lowering agents: A comprehensive review of trial evidence

and potential cardioprotective mechanisms. Cardiovasc Res.

118:2231–2252. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Banerjee M, Pal R, Nair K and Mukhopadhyay

S: SGLT2 inhibitors and cardiovascular outcomes in heart failure

with mildly reduced and preserved ejection fraction: A systematic

review and meta-analysis. Indian Heart J. 75:122–127.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Minisy MM and Abdelaziz A: The role of

SGLT 2 inhibitors in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction

(HFpEF): A systematic review and Meta-analysis of randomized

controlled trials. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 25(765)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Parums DV: Review articles, systematic

reviews, meta-analysis, and the updated preferred reporting items

for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines.

Med Sci Monit. 27(e934475)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

McGuinness LA and Higgins JP: Risk-of-bias

VISualization (robvis): An R package and Shiny web app for

visualizing risk-of-bias assessments. Res Syn Methods. 12:55–61.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

González-Padilla DA and Dahm P: Evaluating

the certainty of evidence in Evidence-based medicine. Euro Urol

Focus. 9:708–710. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Nassif ME, Windsor SL, Borlaug BA, Kitzman

DW, Shah SJ, Tang F, Khariton Y, Malik AO, Khumri T, Umpierrez G,

et al: The SGLT2 inhibitor dapagliflozin in heart failure with

preserved ejection fraction: A multicenter randomized trial. Nat

Med. 27:1954–1960. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Spertus JA, Birmingham MC, Nassif M,

Damaraju CV, Abbate A, Butler J, Lanfear DE, Lingvay I, Kosiborod

MN and Januzzi JL: The SGLT2 inhibitor canagliflozin in heart

failure: The CHIEF-HF remote, patient-centered randomized trial.

Nat Med. 28:809–813. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Vaduganathan M, Cannon CP, Jardine MJ,

Heerspink HJL, Arnott C, Neuen BL, Sarraju A, Gogate J, Seufert J,

Neal B, et al: Effects of canagliflozin on total heart failure

events across the kidney function spectrum: Participant-level

pooled analysis from the CANVAS Program and CREDENCE trial. Eur J

Heart Fail. 26:1967–1975. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

The EMPA-KIDNEY Collaborative Group.

Herrington WG, Staplin N, Wanner C, Green JB, Hauske SJ, Emberson

JR, Preiss D, Judge P, Mayne KJ, et al: Empagliflozin in patients

with chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 388:117–127.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Petrie MC, Udell JA, Anker SD, Harrington

J, Jones WS, Mattheus M, Gasior T, van der Meer P, Amir O, Bahit

MC, et al: Empagliflozin in acute myocardial infarction in patients

with and without type 2 diabetes: A pre-specified analysis of the

EMPACT-MI trial. Eur J Heart Fail. 27:577–588. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Perkovic V, Jardine MJ, Neal B, Bompoint

S, Heerspink HJL, Charytan DM, Edwards R, Agarwal R, Bakris G, Bull

S, et al: Canagliflozin and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes and

nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 380:2295–2306. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Verma S, Sharma A, Zinman B, Ofstad AP,

Fitchett D, Brueckmann M, Wanner C, Zwiener I, George JT, Inzucchi

SE, et al: Empagliflozin reduces the risk of mortality and

hospitalization for heart failure across Thrombolysis In Myocardial

Infarction Risk Score for Heart Failure in Diabetes categories:

Post hoc analysis of the EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial. Diabetes Obes

Metab. 22:1141–1150. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Heerspink HJL, Stefánsson BV,

Correa-Rotter R, Chertow GM, Greene T, Hou FF, Mann JFE, McMurray

JJV, Lindberg M, Rossing P, et al: Dapagliflozin in patients with

chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 383:1436–1446.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Wiviott SD, Raz I, Bonaca MP, Mosenzon O,

Kato ET, Cahn A, Silverman MG, Zelniker TA, Kuder JF and Murphy SA:

Dapagliflozin and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N

Engl J Med. 380:347–357. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Bhatt DL, Szarek M, Steg PG, Cannon CP,

Leiter LA, McGuire DK, Lewis JB, Riddle MC, Voors AA, Metra M, et

al: Sotagliflozin in patients with diabetes and recent worsening

heart failure. N Engl J Med. 384:117–128. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Cannon CP, Pratley R, Dagogo-Jack S,

Mancuso J, Huyck S, Masiukiewicz U, Charbonnel B, Frederich R,

Gallo S, Cosentino F, et al: Cardiovascular outcomes with

ertugliflozin in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 383:1425–1435.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Fitchett D, Zinman B, Wanner C, Lachin JM,

Hantel S, Salsali A, Johansen OE, Woerle HJ, Broedl UC and Inzucchi

SE: EMPA-REG OUTCOME® trial investigators. Heart failure

outcomes with empagliflozin in patients with type 2 diabetes at

high cardiovascular risk: Results of the EMPA-REG

OUTCOME® trial. Eur Heart J. 37:1526–1534.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Inzucchi SE, Khunti K, Fitchett DH, Wanner

C, Mattheus M, George JT, Ofstad AP and Zinman B: Cardiovascular

benefit of empagliflozin across the spectrum of cardiovascular risk

factor control in the EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial. J Clin Endocrinol

Metab. 105:3025–3035. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Kato ET, Silverman MG, Mosenzon O,

Zelniker TA, Cahn A, Furtado RHM, Kuder J, Murphy SA, Bhatt DL,

Leiter LA, et al: Effect of dapagliflozin on heart failure and

mortality in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Circulation. 139:2528–2536.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Mahaffey KW, Neal B, Perkovic V, de Zeeuw

D, Fulcher G, Erondu N, Shaw W, Fabbrini E, Sun T, Li Q, et al:

Canagliflozin for primary and secondary prevention of

cardiovascular events: Results from the CANVAS Program

(Canagliflozin Cardiovascular Assessment Study). Circulation.

137:323–334. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Neal B, Perkovic V, Mahaffey KW, De Zeeuw

D, Fulcher G, Erondu N, Shaw W, Law G, Desai M and Matthews DR:

CANVAS Program Collaborative Group. Canagliflozin and

cardiovascular and renal events in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med.

377:644–657. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Ohkuma T, Van Gaal L, Shaw W, Mahaffey KW,

de Zeeuw D, Matthews DR, Perkovic V and Neal B: Clinical outcomes

with canagliflozin according to baseline body mass index: Results

from post hoc analyses of the CANVAS Program. Diabetes Obes Metab.

22:530–539. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Wanner C, Lachin JM, Inzucchi SE, Fitchett

D, Mattheus M, George J, Woerle HJ, Broedl UC, von Eynatten M and

Zinman B: EMPA-REG OUTCOME Investigators. Empagliflozin and

clinical outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus,

established cardiovascular disease, and chronic kidney disease.

Circulation. 137:119–129. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Zinman B, Wanner C, Lachin JM, Fitchett D,

Bluhmki E, Hantel S, Mattheus M, Devins T, Johansen OE, Woerle HJ,

et al: Empagliflozin, cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in

type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 373:2117–2128. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Anker SD, Butler J, Filippatos G, Ferreira

JP, Bocchi E, Böhm M, Brunner-La Rocca HP, Choi DJ, Chopra V,

Chuquiure-Valenzuela E, et al: Empagliflozin in heart failure with

a preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 385:1451–161.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Anker SD, Butler J, Filippatos G, Khan MS,

Marx N, Lam CSP, Schnaidt S, Ofstad AP, Brueckmann M, Jamal W, et

al: Effect of empagliflozin on cardiovascular and renal outcomes in

patients with heart failure by baseline diabetes status: Results

from the EMPEROR-Reduced trial. Circulation. 143:337–349.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Hernandez AF, Udell JA, Jones WS, Anker

SD, Petrie MC, Harrington J, Mattheus M, Seide S, Zwiener I, Amir

O, et al: Effect of empagliflozin on heart failure outcomes after

acute myocardial infarction: Insights from the EMPACT-MI trial.

Circulation. 149:1627–1638. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Kosiborod MN, Angermann CE, Collins SP,

Teerlink JR, Ponikowski P, Biegus J, Comin-Colet J, Ferreira JP,

Mentz RJ, Nassif ME, et al: Effects of empagliflozin on symptoms,

physical limitations, and quality of life in patients hospitalized

for acute heart failure: Results From the EMPULSE trial.

Circulation. 146:279–288. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Kosiborod MN, Jhund PS, Docherty KF, Diez

M, Petrie MC, Verma S, Nicolau JC, Merkely B, Kitakaze M, DeMets

DL, et al: Effects of dapagliflozin on symptoms, function, and

quality of life in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection

fraction: Results from the DAPA-HF trial. Circulation. 141:90–99.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

McMurray JJV, Docherty KF, de Boer RA,

Hammarstedt A, Kitzman DW, Kosiborod MN, Maria Langkilde A, Reicher

B, Senni M, Shah SJ, et al: Effect of dapagliflozin versus placebo

on symptoms and 6-Minute walk distance in patients with heart

failure: The DETERMINE randomized clinical trials. Circulation.

149:825–838. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

McMurray JJV, Solomon SD, Inzucchi SE,

Køber L, Kosiborod MN, Martinez FA, Ponikowski P, Sabatine MS,

Anand IS, Bělohlávek J, et al: Dapagliflozin in patients with heart

failure and reduced ejection fraction. Eur Heart J. 381:1995–2008.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

McMurray JJV, Wheeler DC, Stefánsson BV,

Jongs N, Postmus D, Correa-Rotter R, Chertow GM, Hou FF, Rossing P,

Sjöström CD, et al: Effects of dapagliflozin in patients with

kidney disease, with and without heart failure. JACC Heart failure.

9:807–820. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Solomon SD, McMurray JJV, Claggett B, de

Boer RA, DeMets D, Hernandez AF, Inzucchi SE, Kosiborod MN, Lam

CSP, Martinez F, et al: Dapagliflozin in heart failure with mildly

reduced or preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med.

387:1089–1098. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Usman MS, Bhatt DL, Hameed I, Anker SD,

Cheng AYY, Hernandez AF, Jones WS, Khan MS, Petrie MC, Udell JA, et

al: Effect of SGLT2 inhibitors on heart failure outcomes and

cardiovascular death across the cardiometabolic disease spectrum: A

systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol.

12:447–461. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Teo YH, Teo YN, Syn NL, Kow CS, Yoong CSY,

Tan BYQ, Yeo TC, Lee CH, Lin W and Sia CH: Effects of

Sodium/Glucose Cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) Inhibitors on cardiovascular

and metabolic outcomes in patients without diabetes mellitus: A

systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized-controlled

trials. J Am Heart Assoc. 10(e019463)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Greene SJ, Butler J and Fonarow GC:

Contextualizing risk among patients with heart failure. JAMA.

326:2261–2262. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Kenny HC and Abel ED: Heart failure in

type 2 diabetes mellitus: Impact of glucose-lowering agents, heart

failure therapies, and novel therapeutic strategies. Circ Res.

124:121–141. 2019.

|

|

55

|

Kluger AY, Tecson KM, Lee AY, Lerma EV,

Rangaswami J, Lepor NE, Cobble ME and McCullough PA: Class effects

of SGLT2 inhibitors on cardiorenal outcomes. Cardiovasc Diabetol:

Aug 5, 2019 (Epub ahead of print).

|

|

56

|

Tromp J, Lim SL, Tay WT, Teng THK,

Chandramouli C, Ouwerkerk W, Wander GS, Sawhney JPS, Yap J,

MacDonald MR, et al: Microvascular disease in patients with

diabetes with heart failure and reduced ejection versus preserved

ejection fraction. Diabetes Care. 42:1792–1799. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Nuffield Department of Population Health

Renal Studies Group; SGLT2 inhibitor Meta-Analysis Cardio-Renal

Trialists' Consortium. Impact of diabetes on the effects of sodium

glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors on kidney outcomes:

Collaborative meta-analysis of large placebo-controlled trials.

Lancet. 400:1788–1801. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Abdelgadir E, Rashid F, Bashier A and Ali

R: SGLT-2 inhibitors and cardiovascular protection: Lessons and

gaps in understanding the current outcome trials and possible

benefits of combining SGLT-2 Inhibitors With GLP-1 agonists. J Clin

Med Res. 10:615–625. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Packer M, Wilcox CS and Testani JM:

Critical analysis of the effects of SGLT2 inhibitors on renal

tubular sodium, water and chloride homeostasis and their role in

influencing heart failure outcomes. Circulation. 148:354–372.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Dyck JRB, Sossalla S, Hamdani N, Coronel

R, Weber NC, Light PE and Zuurbier CJ: Cardiac mechanisms of the

beneficial effects of SGLT2 inhibitors in heart failure: Evidence

for potential off-target effects. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 167:17–31.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Hanke J, Romejko K and Niemczyk S:

Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter-2 inhibitors in diabetes and beyond:

Mechanisms, pleiotropic benefits, and clinical Use-Reviewing

protective effects exceeding glycemic control. Molecul.

30(4125)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

McLean P and Bennett J: ‘Trey’ Woods E.

Chandrasekhar S, Newman N, Mohammad Y, Khawaja M, Rizwan A,

Siddiqui R, Birnbaum Y, et al: SGLT2 inhibitors across various

patient populations in the era of precision medicine: The