Introduction

As per the central dogma of biology, RNA functions

as an intermediate molecule, assisting transfer genetic information

from the DNA level to the protein synthesis level. For a number of

years, this process was considered the primary pathway for gene

expression. However, over time, the functional importance of RNA

transcripts and other non-coding regions, that are not directly

encoded to proteins, has been recognized. Various of these

non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) are involved in several cellular

functions, including the regulation of gene expression, alternative

splicing, RNA processing, the inhibition of translation and mRNA

degradation. In fact, RNA plays a crucial role in almost every

level of genome regulation (1-3).

ncRNAs are typically divided into two main classes:

Structural and regulatory. Structural ncRNAs include ribosomal

RNAs, transfer RNAs and small nuclear RNAs. On the other hand,

regulatory ncRNAs are further classified into several

subcategories, such as microRNAs (miRNAs/miRs), Piwi-interacting

RNAs, small interfering RNAs and long ncRNAs (lncRNAs). In

addition, a subclass of promoter-associated RNAs that interacts

with RNA promoters and is produced by genomic enhancer regions

(enhancer RNAs) has previously been described (4).

lncRNAs are a highly diverse and heterogeneous class

of ncRNAs, varying in their characteristics, locations in the

genome and functional roles. They are the most abundant class of

non-coding transcripts, and they typically have low expression

levels and are >200 nucleotides in length (5). These RNAs can be categorized based on

their location in the genome, into intronic, intergenic (lincRNAs),

divergent, sense and antisense lncRNAs (6,7).

Unlike small ncRNAs, lncRNAs are less conserved across species and

their roles in the regulation of gene expression are not yet fully

understood (8).

Even though the limited number of functional lncRNAs

have been well characterized, they play essential roles in the

regulation of gene expression at various stages. lncRNAs are

involved in post-transcriptional regulation by controlling protein

synthesis, RNA maturation and RNA transport, as well as in gene

silencing through modulation of chromatin structure. Due to the

vast variety of lncRNAs, categorizing them is challenging. However,

several studies have classified them based on their molecular

functions, as signaling molecules that relay temporal, spatial and

developmental information; as decoys that isolate various RNA

molecules and proteins to inhibit their activity; as guides that

direct epigenetic regulators and transcriptional factors to

specific genomic loci; and as scaffolds that facilitate the

formation of macromolecular complexes with a various functions

(8). Notably, individual lncRNAs

may function through more than one mechanism, potentially leading

to the combination of functions that create more complex functions

in cellular procedures. Thus, understanding the shared features of

these mechanisms is crucial for elucidating the functions of

lncRNAs and their crucial roles in cellular regulation (8).

In addition to the aforementioned functions, several

lncRNAs regulate gene expression by binding to miRNAs, functioning

as ‘miRNA sponges’. These lncRNAs contain multiple binding sites

for one or more miRNAs and prevent their interaction with target

mRNAs. As a result, the target mRNAs of the miRNAs are upregulated,

increasing their expression (8,9).

The direct and indirect interactions between lncRNAs

and transcription factors are well-documented. For instance, lncRNA

Gas5, which is activated in the absence of growth factors, contains

a hairpin structure sequence pattern that resembles the DNA-binding

site of the glucocorticoid receptor (GR), a member of the family of

nuclear receptors (NRs). By acting as a decoy, Gas5 blocks the

access of GR to DNA, thus inhibiting the transcription of GR

metabolic target genes (10). NRs

are transcription factors that bind to DNA and regulate the

expression of genes involved in processes, such as homeostasis,

stress response and metabolism (11). The dysregulation of NRs has been

reported in various diseases, including neurodegenerative diseases,

cancer, metabolic syndromes, diabetes, obesity and autism (12). Thus, understanding the mechanisms of

interaction between lncRNAs and NRs is critical for determining the

complex molecular pathways involved and could lead to the

development of more effective and specialized therapies for plenty

of diseases.

To further explore the regulatory roles of lncRNAs

in gene expression, the present study examined lncRNAs whose

expression levels were altered following the activation of an NR.

These lncRNAs were classified into two groups as follows: Those

that are upregulated and those that are downregulated. The aim was

to explore whether any lncRNAs fail to exhibit a regulatory

function. Considering the evolutionary conservation of lncRNAs, it

was hypothesized that the presence of sequence motifs within lncRNA

sequences could provide insight into their regulatory roles. These

motifs, if present with non-random frequency, may serve as

signatures that contribute to the regulatory functions of

lncRNAs.

Using the MEME algorithm, the lncRNA sequences from

the aforementioned groups were analyzed and six specific sequence

motifs (three in each group) were identified. The potential roles

of these motifs were investigated, providing insight into how

lncRNAs containing these motifs may regulate a wide range of

biological processes. According to the results obtained, one of the

discovered motifs was found to be complementary to the miRNA

hsa-miR-1908-3p, suggesting that lncRNAs containing this motif may

act as sponges for this miRNA, regulating the expression of its

target mRNAs. Additionally, all six motifs were detected in

specific genomic regions of human genome, particularly on

chromosome 19, with a high percentage of occurrence. Among these

regions on chromosome 19, the motifs were aligned with the

adeno-associated virus (AAV) integration site 1 (AAVS1), a known

hotspot for the AAV integration. Notably, a number of lncRNAs

containing at least one of these motifs, participate in various

biological pathways such as development, immune response,

inflammation, cell cycle, regulation of gene expression and

homeostasis, highlighting the diverse roles of lncRNAs in cellular

pathways. To explore the evolutionary significance of these motifs,

the present study investigated their presence across various

species, including Mus musculus, Squamata (lizard), Danio

rerio (zebrafish), Drosophila melanogaster, Caenorhabditis elegans,

Escherichia coli (K12 MG1655), Saccharomyces cerevisiae,

Bacillus subtilis (PY79) and Euglena gracilis, which

differ both evolutionarily and genetically. This cross-species

analysis revealed that these motifs are evolutionary conserved,

suggesting their potential importance in fundamental biological

processes. The conservation of these motifs across a wide range of

species highlights their potential functional relevance, warranting

further investigation into their roles in gene regulation and

interaction with NRs.

Data and methods

The present study developed an in-house pipeline for

the analysis of the collected dataset of lncRNAs with known

expression levels, as documented in the literature. These lncRNAs

are related to the activation and expression levels of NRs. This

pipeline includes the following key steps: i) Literature review and

data retrieval: A comprehensive search in current literature was

conducted to identify lncRNAs whose expression levels are known to

be associated with the activation of NRs. In this stage, the

corresponding RNA sequences were also retrieved for further

analysis. ii) Classification of lncRNAs: The identified lncRNAs

were classified into two groups. The first group included lncRNAs

whose expression was upregulated following the activation of an NR,

while the second group included lncRNAs whose expression was

downregulated in response to the activation of an NR. Subsequently,

conserved sequence motifs were identified within these two lncRNA

sub-groups. iii) Statistical evaluation of motif significance: The

identified motifs were statistically evaluated to determine their

significance. This involved estimating the probability of these

motifs occurring randomly within the entire human DNA. iv)

Exploration of motif functionality: In this step, we explored the

potential functions of the identified motifs, focusing on their

role in gene regulation. This included investigating their

potential to function as binding sites for miRNAs, examining their

presence within genome regulatory regions and exploring their

conservation through evolution. These analyses helped broaden the

understanding of the roles of these lncRNAs in cellular processes.

A detailed description of the in-house pipeline is provided

below.

Data collection and filtering and annotation.

The IDs of lncRNAs related to the NRs were collected from the

literature according to the study by Foulds et al (13). The IDs of lncRNAs had the following

formats: i) Name of lncRNA (e.g., MALAT-1); ii) ID such as

AC145110.1; iii) ID such as NR_026765; iv) ID such as

RP1-148H17.1.

The first three ID formats correspond to different

types of IDs detected at GenBank, a comprehensive genetic sequence

database available at NCBI (ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). The fourth ID format derived from

LNCipedia database (14), a novel

database for human lncRNA transcripts and genes.

Based on these ID formats, the dataset of lncRNAs

was classified into four subcategories. To retrieve the

corresponding sequences for each subcategory, an in-house algorithm

was developed using the MATLAB bioinformatics toolbox. The details

of the four algorithms used for sequence retrieval are presented in

Data S1.

Following the creation of the four individual

algorithms for each type of lncRNA ID, we developed a unified

algorithm designed to retrieve the sequences of the entire dataset,

containing all ID formats simultaneously. The aggregate algorithm

used for retrieving all lncRNA sequences is presented in Data S2.

Dataset classification and motif exploration.

In order to further classify the lncRNAs within the two

sub-datasets, the present study investigated the presence of joint

motifs across the lncRNA sequences in each subgroup. Following the

collection, filtering and annotation of the data, the Multiple EM

for Motif Elicitation (MEME) software, version 4.10.0(15), was employed to identify joint motifs

within the lncRNA sequences of each subgroup. MEME is a part of the

ΜEME Suite (https://meme-suite.org/meme/), which is a

comprehensive set of tools for motif-based sequence analysis. This

tool is designed to detect motifs or sequence patterns that occur

repeatedly in a group of related nucleotide or protein sequences,

finding common biological functions and structural features across

different sequences. The term ‘pattern’ or ‘motif’ refers to a

short, sequence that repeats within a group of similar sequences.

The motifs have no gaps, while the MEME algorithm calculates how

often each motif appears across sequences, allowing the detection

of multiple motifs (15). For the

purposes of the present study, the MEME algorithm was run on a

local server using the Linux operating system.

Statistical evaluation of the randomness of the

occurrence of the discovered motifs. To calculate the

probability of finding specific nucleotide bases of each motif at a

random position within the 3.2 billion bases of the human DNA, it

was assumed that the occurrence of a nucleotide at one position in

the motif's sequence is independent of the occurrence of

nucleotides at other positions. This assumption represents the

simplest hypothesis, involving the fewest parameters. Thus, the

rule of probabilities for independent events was applied, which

defines the probability of multiple events occurring independently.

Specifically, two events are considered independent if the

occurrence or non-occurrence of one does not influence the

probability of the other event's occurrence or non-occurrence

(16,17). To calculate the probability of both

events A and B occurring together, the formula for independent

events was used: P (A and B)=P (A) x P (B). This approach was

applied to assess the randomness of each motif existence within

human DNA.

Exploration of the potential role of the

identified motifs. A total of six motifs were discovered, three

in each subgroup of lncRNAs. To explore the potential role of the

collected lncRNAs in the regulation of gene expression, the present

study focused on the lncRNAs that contained at least one of the

discovered motifs. Since motifs are usually conserved through

evolution and contribute crucial functions to the regions they

occupy, the authors proceeded to explore the potential roles of

these motifs in genome regulation, which could reflect the

functions of the lncRNAs that contain them. For this purpose, two

different approaches were pursued. The first included querying the

miRBase database (https://www.mirbase.org/) to identify mature miRNAs

with complementary sequences to these motifs, suggesting the

possibility of miRNA-lncRNA interaction. The second approach

included the exploration of the presence of these motif sequences

across whole human DNA in order to determine their existence in

other genomic regions, assess whether they were associated with

regulatory regions, and explore potential roles in genomic

regulation. In addition, the evolutionary conservation of the

motifs was explored to determine the maintenance of their functions

through evolution.

Exploration of the interactions of miRNA target

genes. The main purpose of this approach was to identify the

potential role of lncRNAs containing the identified motifs in

functioning as ‘sponges’ for miRNAs, where the motifs serve as

interaction/binding regions between lncRNAs and miRNAs. For this

purpose, the blastn algorithm from miRbase was used, with the

complement sequence of each motif as input. This allowed this

algorithm to search for similarities between the motif sequences

and known miRNA sequences in the miRBase. Subsequently, the authors

further investigated the predicted target genes of the identified

miRNA using the bioinformatic tool miRTarget from the miRDB

database (16), and the TargetScanS

database (Release 8.0) (17-19).

Finally, the location of the binding sites in the

target mRNAs was examined by using the multiple alignment algorithm

ClustalW, using as input the mRNA sequence of the targets and the

complementary sequence of miR-1908-3p.

Exploration of motif sequences in whole human

DNA. To investigate whether these motif sequences also appear

in other regions of the genome, the online tool Find Individual

Motif Occurrences (FIMO) from the MEME Suite was used. This tool is

an algorithm designed to identify specific matches of a given motif

within a set of sequences, specialized for analyzing shorter

sequences such as motifs. Similar to a BLAST algorithm, FIMO

searches for matches to each motif. When employed locally, motifs

must be in MEME Motif Format; however, the online version of FIMO

supports additional motif formats.

Subsequently, an algorithm was developed using the

MATLAB Bioinformatics Toolbox to create a chromosome plot for each

identified motif. This plot displayed the locations of the motif

sequences by marking them with a red dot next to the corresponding

regions on the chromosome where they were detected. The input for

this algorithm was the output from the FIMO tool in tsv format. The

specific algorithm we developed is presented in Data S3.

The FIMO tool was also used to examine the presence

of the identified sequence motifs in the genomes of various

organisms, including Mus musculus, Squamata (lizard),

Danio rerio (zebrafish), Drosophila melanogaster, Caenorhabditis

elegans, Escherichia coli (K12 MG1655), Saccharomyces

cerevisiae and Bacillus subtilis (PY79), to assess their

evolutionary conservation. Additionally, the present study

investigated the presence of these motifs in the genome of

Euglena gracilis, a protist believed to possess an ancient

form of NRs. Due to the unavailability of Euglena's genome

in the database of the FIMO tool, the ‘Matcher’ tool available on

the Galaxy platform (usegalaxy.org)

was employed to check for potential sequence matches (20).

Galaxy is an open-source, web-based platform that

aids computational biology research by providing a comprehensive

suite of tools for data analysis. The ‘Matcher’ tool within this

platform compares two different sequences to identify regions of

similarity, supporting both local and global alignments. This tool

enables the identification of conserved genomic regions across

species and helps in detecting functionally important motifs that

have been preserved through evolution. This tool is widely used in

genomics and bioinformatics for tasks such as gene annotation,

mutation analysis, and the discovery of conserved regulatory

regions (21).

Results and Discussion

Data collection, filtering and

annotation

The initial dataset, collected from the study by

Foulds et al (13),

contained 1,823 lncRNA IDs, with sequences for 1,788 lncRNAs

successfully identified and retrieved. Following the removal of the

duplicate sequences, the final dataset consisted of 1,753 lncRNAs.

These were then classified into two subgroups as follows: The first

subgroup contained 778 upregulated lncRNAs and the second subgroup

contained 975 downregulated lncRNAs (Table SI).

Dataset classification and motif

identification

The MEME algorithm was employed to identify

potential motifs within the lncRNA sequences of each subgroup. The

results of this analysis led to the identification of six motifs:

Three motifs in the upregulated lncRNA group and three in the

downregulated lncRNA group.

In the upregulated lncRNAs group following NR

activation, the first identified motif was

GATCCGCCCGCCTCGGCCTCCCAAAGTGCTGGGATTACAGG, found in 140 lncRNAs

from the total 778 (Fig. S1). The

second motif discovered in this group was

TGGCCAGGCTGGTCTCGAACTCCTGACCT, present in 127 lncRNAs (Fig. S2), while the third motif was

TAATCCCAGCACTTTGGGAGGCCGAGG, which occurs in 115 lncRNAs (Fig. S3).

For the downregulated lncRNA group following NR

activation, the first motif discovered was

GTGGCTCACGCCTGTAATCCCAGCACTTTGGGAGGCCGAGG, found in 145 lncRNA out

of the total of 975 (Fig. S4). The

second motif discovered was

AGGTCAGGAGTTCGAGACCAGCCTGGCCAACATGGTGAAAC, which is present in 128

lncRNAs (Fig. S5), and the third

motif was CCTCAGCCTCCCGAGTAGCTGGGACTACAGGCGC, found in 129 lncRNAs

from this group (Fig. S6).

Statistical evaluation

To calculate the probability of each motif appearing

randomly at a position within the 3.2 billion base pairs of human

DNA, the following steps were taken:

The first motif from the upregulated lncRNAs

subgroup consists of 41 nucleotide bases. Since each base (A, C, G,

or T) has a ¼ probability of being in a specific position in the

sequence, the probability of finding the full sequence of these 41

nucleotide bases is:

(¼)41=2.23517418x10-25.

Taking into consideration the total number of human

DNA base pairs (3.2 billion or 3.2x109), the probability

of this sequence occurring randomly at any position in the genome

is:

3.2x109x2.23517418x10-25=7.15255974x10-16.

Accordingly, for the second motif in the upregulated

lncRNA subgroup, consisting of 29 nucleotides, the probability

calculation is as follows:

(¼)29=1.8626451x10-18. The probability of

finding this specific sequence randomly in human genome is:

3.2x109x1.8626451x10-18=5.96174432x10-10.

For the third motif in the upregulated lncRNAs subgroup, which

consists of 27 nucleotides, the results are as follows:

(¼)27=7.8886x10-17. Thus, the probability of

its random occurrence is:

3.2x109x7.8886x10-17=2.52435x10-7.

In the downregulated lncRNA subgroup, both first and

second motifs consist of 41 nucleotides; thus, the same probability

calculations apply: (¼)41=2.23517418x10-25.

Thus, the probability of their random occurrence is:

3.2x109x2.23517418x10-25=7.15255974x10-16.

The third motif in the downregulated lncRNA subgroup, consists of

34 nucleotides: (¼)34=1.421085x10-21. Thus,

the probability of its random occurrence is:

3.2x109x1.421085x10-21=4.5474755x10-13.

The calculated probabilities are extraordinarily low

compared to common biological standards and are consistent with the

hypothesis that these motifs are not randomly occurring in the

genome (22).

The above-calculated probabilities suggest that the

motifs discovered are non-random occurrences in the human genome,

even when assuming independent events. However, the nucleotide

sequence of DNA is linked to biological functions. The order of the

bases is strictly determined by the way nucleotides bind each other

in the double helix structure. The complementary pairing of

nucleotides restricts the possible sequences that DNA can form,

meaning that the probability of these motifs occurring randomly in

the genome would likely be even lower than the values calculated

above.

Exploration of the potential role of

the identified motifs. Exploration of the miRNA-target gene

interactions

As previously mentioned, lncRNAs can function as

miRNA sponges, regulating the expression of mRNA targets (8,9).

Considering this regulatory role, we searched for potential miRNAs

complementary to the six identified motifs in miRBase. In the

present study, the search revealed that the motif

GATCCGCCCGCCTCGGCCTCCCAAAGTGCTGGGATTACAGG was complementary to

hsa-miR-1908-3p.

miRNAs typically bind to complementary sequences in

mRNAs, mainly targeting the 3' untranslated regions (UTRs)

(23), while there is evidence to

indicate that they can also target the 5' UTRs and coding regions,

thus inhibiting mRNA expression (24). To predict the potential targets of

miRNAs, several computational approaches have been developed, such

as miRanda (25), mirSVR (26), PicTar (27), TargetScan (28), TargetScanS (29), RNA22(30), PITA (31), RNAhybird (32) and DIANA-microT (33). In addition, there are miRNA target

prediction databases such as TarBase (34), PicTar (27) and TargetScan (28).

Thus, to identify mRNAs targeted by hsa-miR-1908-3p,

whose expression may be affected by the interaction between lncRNAs

and this miRNA, the miRDB database was used. This database, through

its miRTarget bioinformatics tool, predicts the mRNA based on

high-throughput sequencing experiments. By this analysis, 11

targets were identified, including METTL21A, CHFR, MTA1, CAVIN4,

IGFBP3, GRB2, DYNLL2, H2AFX, TNRC6C, C1orf229 and ELOVL2

(Table I). In addition, the

TargetScanS (Release 8.0) database (17-19,35)

was also searched, and 487 predicted targets were found (Table SII), including the

aforementioned 11 targets.

| Table IThe target genes of mir-1908-3p were

predicted using the miRTarget tool of miRDB. |

Table I

The target genes of mir-1908-3p were

predicted using the miRTarget tool of miRDB.

| Gene symbol | Gene

description | miRNA name | Target score |

|---|

| METTL21A | Methyltransferase

like 21A |

hsa-miR-1908-3p | 80 |

| CHFR | Checkpoint with

forkhead and ring finger domains |

hsa-miR-1908-3p | 62 |

| MTA1 | Metastasis

associated 1 |

hsa-miR-1908-3p | 62 |

| CAVIN4 | Caveolae associated

protein 4 |

hsa-miR-1908-3p | 61 |

| IGFBP3 | Insulin like growth

factor binding protein 3 |

hsa-miR-1908-3p | 61 |

| GRB2 | Growth factor

receptor bound protein 2 |

hsa-miR-1908-3p | 56 |

| DYNLL2 | Dynein light chain

LC8-type 2 |

hsa-miR-1908-3p | 55 |

| H2AFX | H2A histone family

member X |

hsa-miR-1908-3p | 53 |

| TNRC6C | Trinucleotide

repeat containing 6C |

hsa-miR-1908-3p | 53 |

| C1orf229 | Chromosome 1 open

reading frame 229 |

hsa-miR-1908-3p | 51 |

| ELOVL2 | ELOVL fatty acid

elongase 2 |

hsa-miR-1908-3p | 50 |

miR-1908 is encoded by the first intron of the

FADS1 gene and is highly expressed in mature human

adipocytes, where it is likely involved in regulating the

preadipocyte differentiation (36).

The promoter region of miR-1908 contains two binding sites of

NF-κB, suggesting its transcription is regulated by this

transcription factor (37).

miR-1908 was first discovered in human embryonic stem cells in

2008(38), and its functional role

in melanoma metastasis and angiogenesis was explored in

2012(39). More specifically,

miR-1908, in conjunction with miR-199a-3p and miR-199a-5p, inhibits

apolipoprotein E and DNAJ heat shock protein family 23 member A4,

which reduces the interaction of Apo-E with low-density lipoprotein

receptor-related protein (LRP)-1 and LRP-8. This interaction

promotes melanoma cell invasion and endothelial cell recruitment,

resulting in poor prognosis (39).

Moreover, miR-1908 dysregulation has been shown to be associated

with various types of cancer, where its dysregulation tends to

enhance cell proliferation, invasion, migration and angiogenesis,

thus reducing the survival rate of affected patients (40,41).

Finally, free fatty acids and adipokines, such as resistin and

leptin, are considered to downregulate the expression of miR-1908,

suggesting a role of this miRNA in regulating obesity-related

insulin resistance (42).

Exploration of motif sequences in

whole human DNA

For the analysis of motif sequences across the whole

human genome using the FIMO tool, the following results were

obtained for each of the six motifs. In the upregulated lncRNA

subgroup, the first motif appeared 53,524 times, the second motif

was detected 51,673 times and the third motif was found 53,936

times. In the downregulated lncRNA subgroup, the first motif

(fourth in total) was found 63,126 times, the second motif (fifth

in total) was detected 58,442 times and the third motif (sixth in

total) was found 57,943 times. Using these results, karyotypes were

created for each motif, and the percentage of the occurrences of

each motif across all chromosomes was calculated. The karyotypes

are presented in Fig. S7, Fig. S8, Fig.

S9, Fig. S10, Fig. S11 and Fig. S12.

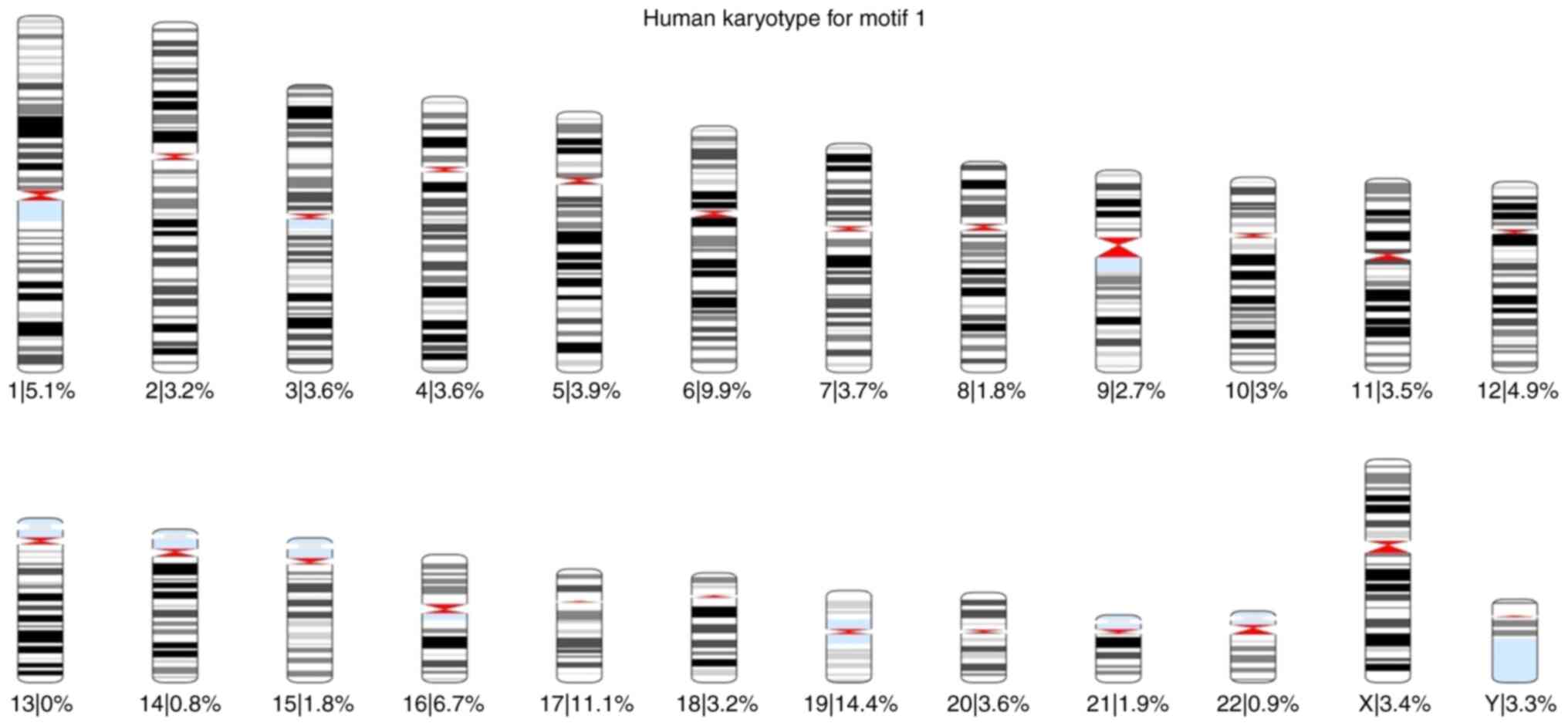

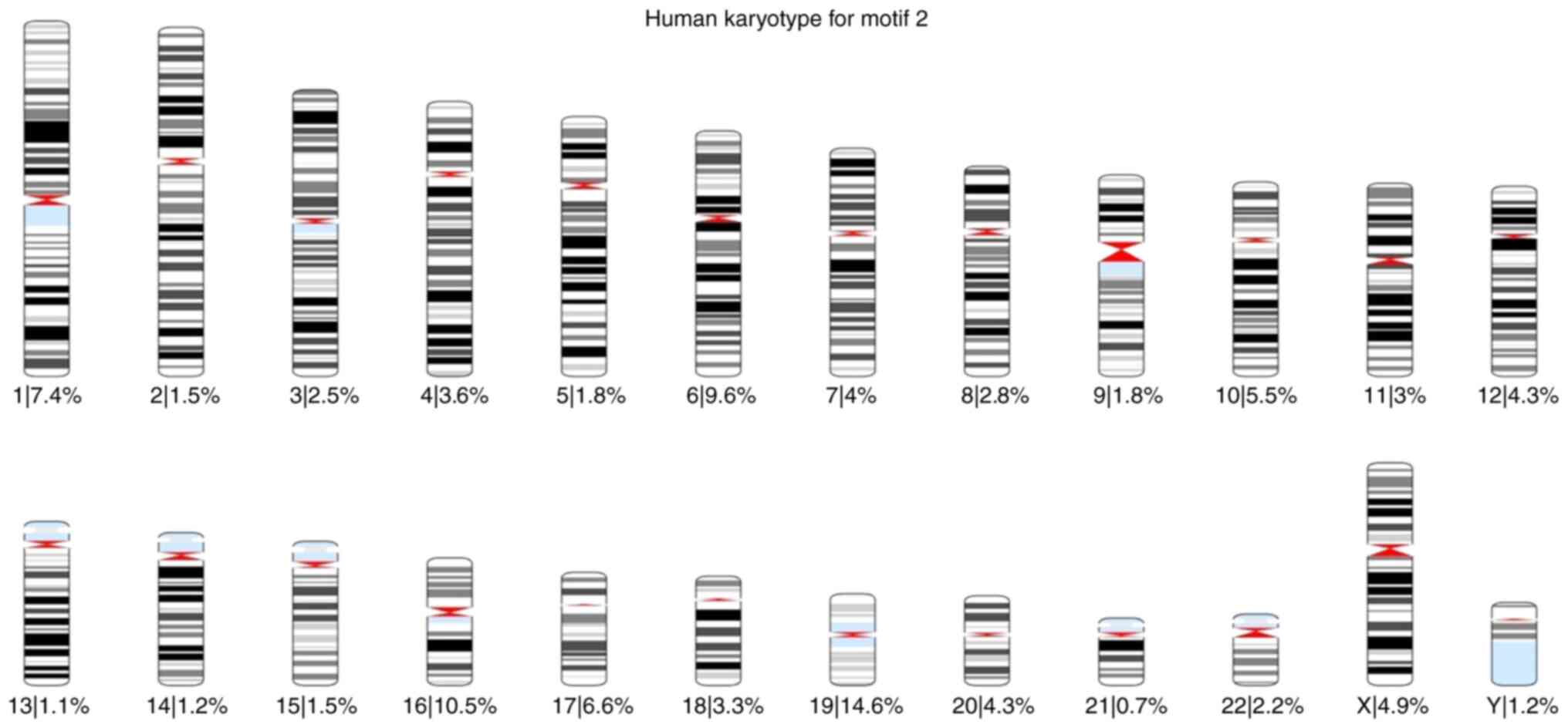

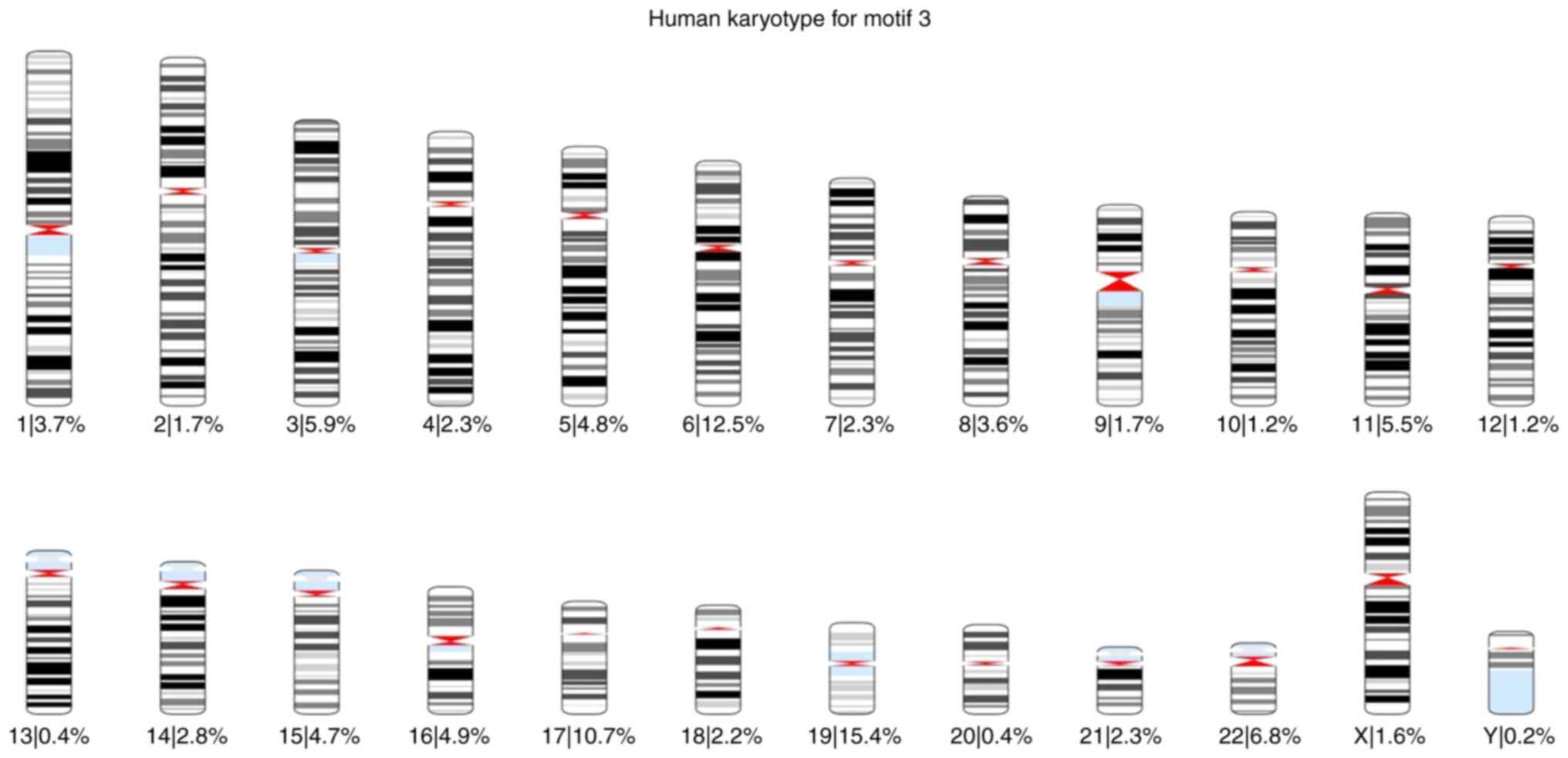

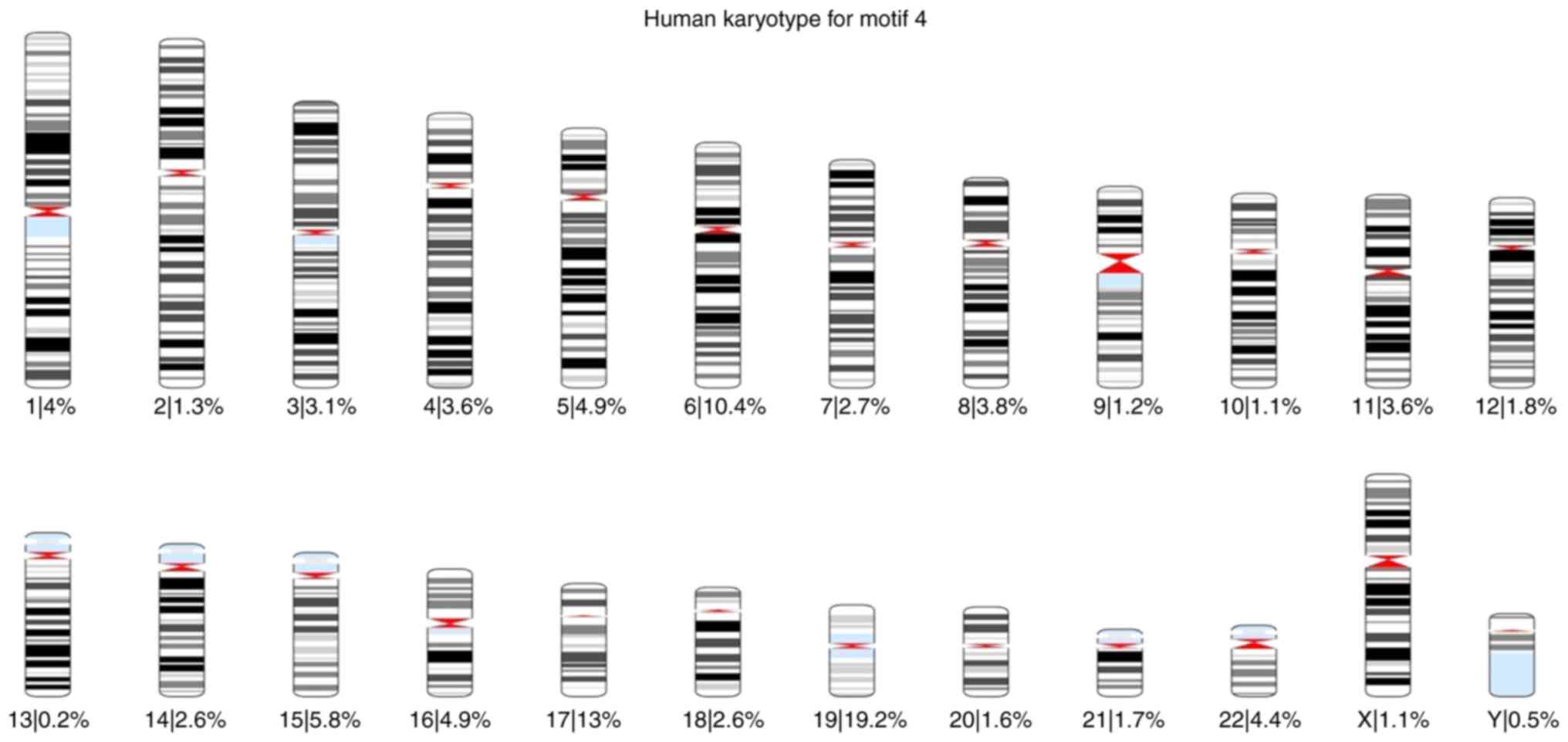

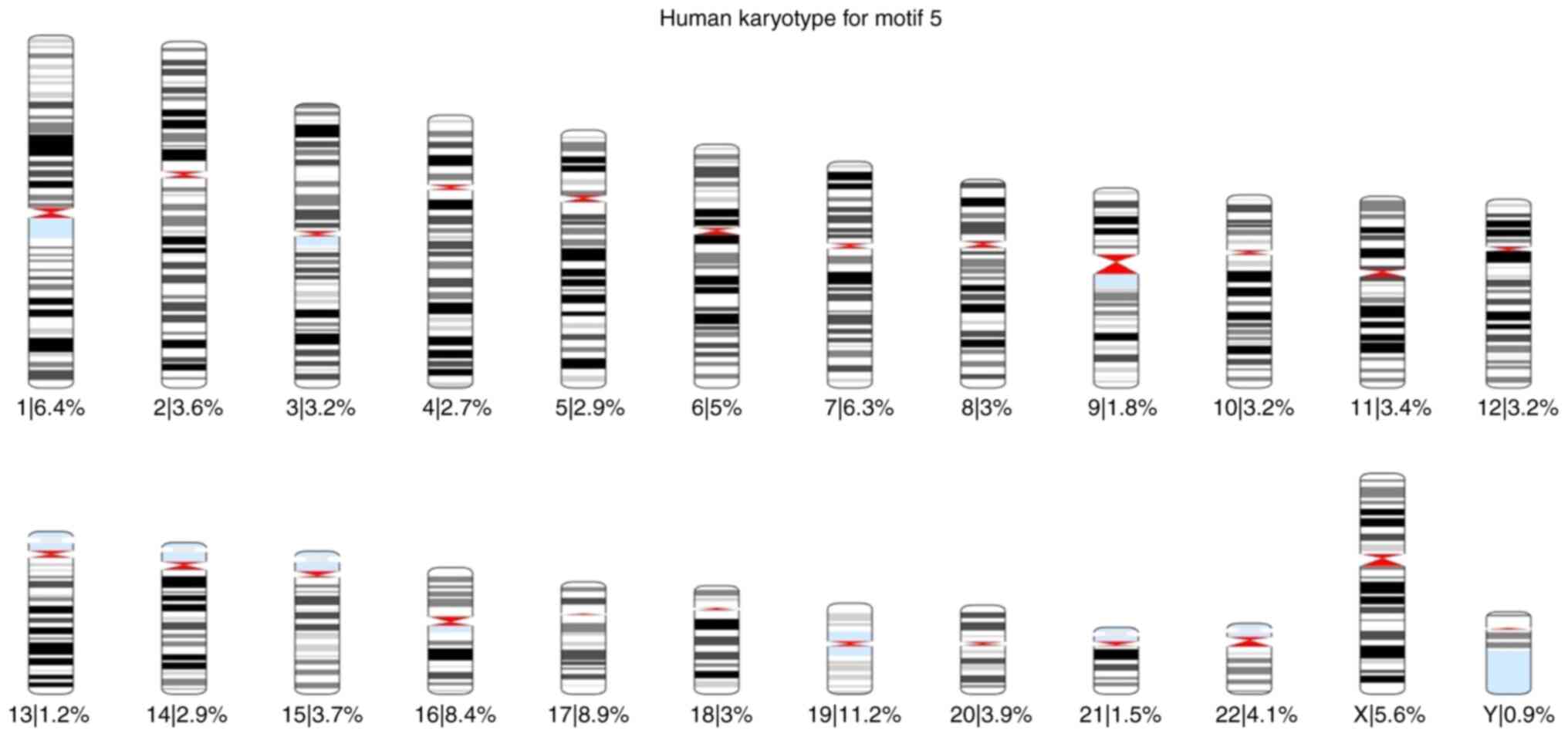

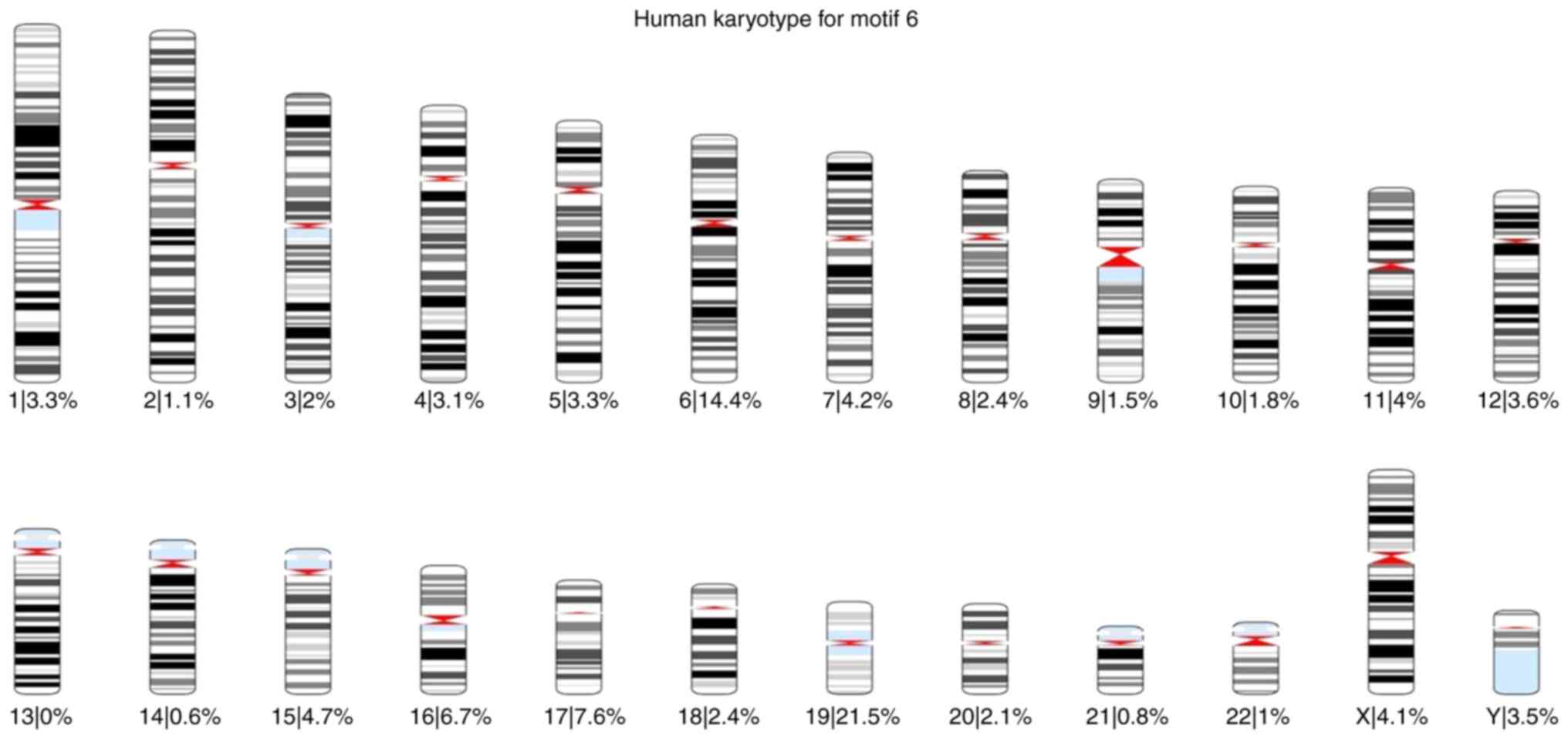

Subsequently, the present study focused on the 1,000

highest-scoring loci which occurred using the FIMO tool for each

motif across the human genome. Using these 1,000 loci, karyotypes

for each motif were also created, and the percentage of occurrences

of each motif was also calculated for each chromosome (Fig. 1, Fig.

2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig.

5 and Fig. 6).

In addition, the chromosome plots for each motif

were created, where the 1,000 loci are represented as red dots

beside the corresponding region. These chromosome plots are

presented in Fig. S13, Fig. S14, Fig. S15, Fig. S16, Fig. S17 and Fig. S18.

Based on these karyotypes and chromosome plots, it

was observed that chromosome 19 exhibited a fairly high percentage

of motif occurrence relative to its size. In fact, for all six

motifs, the percentage of occurrence in chromosome 19 was higher

than that of the longer chromosomes.

According to the literature, human chromosome 19 is

recognized for its unusual nature, which was noted even before the

initial publication of its DNA sequence (43). One of its unusual features is the

considerably high gene density, which exceeds the genome-wide

average by >2-fold and includes 20 large, tandemly clustered

gene families (43). In addition,

chromosome 19 contains a considerable number of segmental

duplications, with 6.2% of its sequence lying within

intrachromosomal segmental duplications (43). The sequence divergence within these

duplications implies that these events occurred between 30 and 40

million years ago (44). These

duplications likely played a pivotal role in the evolution of

phenotypic characteristics that occurred by genes on chromosome 19

across primates, including humans. Moreover, chromosome 19 presents

an unusually high repeat content, comprising 55%, with Alu repeats

comprising 26% of the sequence of the chromosome (44). Another notable feature is the GC

content (48%) of chromosome 19, the highest of any human

chromosome, compared to the GC content of the whole human genome of

41%. This elevated GC content enhances the potential for wide gene

regulation via DNA methylation, particularly at CpG islands, as

well as in CpG regions located within promoters and enhancers

(45).

According to the chromosome plots, the six

identified motifs were detected in various regions of chromosome

19. Between those regions, all six motifs aligned with a specific

locus, AAVS1, located on chromosome 19q13.42. This site was first

mapped in 1991 Kotin et al (46) and Samulski et al (47), who were investigating the

integration mechanism of the AAV into the host genome. According to

these studies, the AAV preferentially intergrades into the AAVS1

region of human chromosome 19q13.42, a unique phenomenon among

eukaryotic DNA viruses (48).

Several features make the AAVS1 region particularly

noteworthy. Notably, the locus for myotonic dystrophy (49), as well as a common breakpoint

related to chronic B-cell leukemia (BCL-3) (47,48),

are located at this region. In addition, AAVS1 undergoes frequent

sister chromatid exchanges (50).

The alignments of motifs with the AAVS1 region were developed using

the Clustal Omega program (51) and

visualized with Jalview version 2.11.2.6 program (52) (Fig.

S19, Fig. S20, Fig. S21, Fig. S22, Fig. S23 and Fig. S24).

The AAVS1 region is located within the first intron

of the phosphatase 1 regulatory subunit 12C (PPP1R12C) gene,

which encodes a protein with a poorly defined function. This region

exhibits several unique features that contribute to its unique

nature. First, it includes a tetrad GACT repeat, which functions as

an AAV Rep-binding element, also detected in the AAV2 inverted

terminal repeats, facilitating the exclusive integration of the AAV

genome in the presence of AAV replication protein. Second,

chromosome 19 is GC-rich, with a higher number of CpG islands

relative to GpC islands, a characteristic linked to regions of

transcriptional activity in vertebrates, which may be relevant to

gene expression (53-55).

Third, several putative transcription factor-binding sites are

present in AAVS1, including CREB, AP-1, AP-2 and Sp1 (48,56).

Fourth, topoisomerase I is predicted to cleave at least two sites

within AAVS1(48). Fifth, Lamartina

et al (56) demonstrated an

open chromatin conformation of AAVS1, accompanied by promoter

activity on chromosome 19 in cultured cells. All these features

position AAVS1 as an approachable region, subject to regulation by

both host and viral regulatory elements.

The potential of the AAVS1 site as a target for gene

therapy applications has been investigated and well-characterized.

This site is known for its ability to integrate exogenous DNA with

limited disruption to endogenous genes, providing a preferred site

for stable transgene expression (57). A key feature that facilitates the

usage of the AAVS1 site in gene therapy is its open chromatin

structure, which is accompanied by endogenous insulator elements

that protect the integrated DNA sequences from trans-activation or

repression (58).

The insertion of exogenous genes into the human

genome is conducted mainly using lentiviral and gamma-retroviral

vectors. However, these vectors tend to integrate randomly within

the genome (59-61),

which can lead to unpredictable interactions between the transgene

and the host genome. Such random integration may result in the

attenuation or complete silencing of the transgene (62-64)

or, more critically, in the dysregulation of host gene expression

(64,65), which poses significant risks in gene

therapy application. One promising strategy to mitigate these risks

involves the use of gene-editing tools that enable site-specific

insertion of transgenes into genomic safe harbors (GSHs) (64,66,67).

GSHs are genomic locus that support a stable environment for

transgene expression without interfering the integrity of

endogenous genes (64,68,69).

The AAVS1 site is considered a GSH that provides a stable transgene

expression (70) due to the

presence of flanking insulator regions (58). According to the study by Lombardo

et al (66), the GSH AAVS1

can support transgene expression across different human cell types,

facilitated by the active and open chromatin structure of the

PPP1R12C gene located in this region (66).

The regulatory role of lncRNAs has been

well-characterized. Numerous studies have detected that lncRNAs

function as crucial regulators of gene expression, participating in

various pathways by acting as decoys, guides and scaffolds for

molecular interactions. In the present study, it was hypothesized

that the regulatory roles of lncRNAs are indisputable, and to

investigate this hypothesis, an in-house pipeline was developed to

analyze a collection of lncRNAs. This pipeline enabled the

identification of conserved motifs within their sequences that may

contribute to their regulatory functions. The analysis revealed

that one of the motifs may function as a sponge for a specific

miRNA, thereby suppressing the function of the miRNA and leading to

the upregulation of its mRNA targets. The function of miRNAs in the

suppression of the translation of mRNA targets is well known, with

implications for numerous pathological conditions, such as

neurodegeneration (71-73),

cancer (72,74,75)

and cardiovascular diseases (74,76,77).

Consequently, the interaction between lncRNAs and miRNAs could have

significant consequences, either promoting disease prevention and

treatment or exacerbating disease progression and severity.

Furthermore, all six motifs identified in the

present study were detected across numerous regions of the human

genome, with chromosome 19 presenting a markedly high frequency of

motif occurrence relative to other chromosomes. Focusing on

chromosome 19, it was found that these motifs were aligned with the

AAVS1 regulatory region, a genomic locus known for its unique

features, including the specific integration of the AAV, the

presence of transcription factor binding sites, an AAV Rep-binding

element, high GC-content, open chromatin, and two cleavage sites

for topoisomerase I. It is noteworthy that the identified motifs

demonstrate a pronounced GC content, a feature commonly associated

with key regulatory regions, including transcription factor binding

sites, polymerase binding sites, and loci involved in chromatin

modification and DNA methylation. GC-rich sequences are often

enriched at genomic sites that regulate transcription and chromatin

remodeling due to their structural properties, such as enhanced

stability and the presence of CpG sites that are key for epigenetic

regulation (78-81).

The existence of these motifs in regions integral to the regulation

of the human genome, combined with their GC-rich nature, suggests

their role in regulating gene expression through DNA methylation

processes. Consequently, these motifs and the lncRNAs containing

them, likely function as pivotal regulatory elements in gene

expression.

In addition to the potential functions of lncRNAs

that contain the identified motifs-based on the presence of these

motif sequences in well-characterized regulatory regions of DNA and

their interactions with other molecules, including miRNAs, the

present study further investigated the documented roles of the

lncRNAs containing at least one of these motifs in the literature

(82-124)

and relevant databases such as NCBI (ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) and GeneCards (125). Despite the incomplete annotation

and characterization of these lncRNAs, the majority of the examined

lncRNAs are located either within intergenic space, introns of

coding genes, or are antisense to coding genes. These lncRNAs are

believed to influence the functions of their associated genes,

mainly by suppressing gene functions. The lncRNAs examined are

involved in various biological processes, such as development,

cellular proliferation, immune responses, inflammation,

transmembrane transport, gene expression regulation, chromatin and

chromosome structure modulation, differentiation, cell cycle

control, spermatogenesis, metabolic regulation, and several

functions related to the nervous and cardiovascular systems. The

results from the present study, as depicted in the diagrams shown

in Fig. S25, Fig. S26, Fig. S27, Fig. S28, Fig. S29 and Fig. S30, illustrate the involvement of

lncRNAs with each specific motif in these diverse biological

pathways.

The emergence of NRs dates back >1.5 billion

years, originating in early eukaryotic organisms as

ligand-dependent transcription factors. These receptors were

responsive to environmental cues such as hormones, light, and

metabolic shifts. The earliest NRs likely played a critical role in

regulating gene expression, helping primitive eukaryotes adapt to

dynamic external conditions, thus aiding their survival and

proliferation. Of note, unicellular organisms such as Euglena

gracilis, a photosynthetic protist, contain an ancestral

version of the NR, providing evidence that these mechanisms were

present well before the evolution of multicellular organisms. This

discovery enhances the understanding of the origins of NRs and

their evolutionary significance (126).

As evolution progressed, NRs diversified into a

complex protein family with distinct functions. Different

subfamilies evolved to regulate a wide variety of biological

processes across animals, plants, fungi and even bacteria. In

modern organisms, NRs govern critical processes such as metabolism,

immune response, reproduction, and development. The diversity of

these receptors is reflected in the large number of subfamilies,

including steroid hormone receptors, thyroid hormone receptors,

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors and orphan NRs. Despite

their varied roles, these receptors retain a conserved

ligand-binding domain that allows them to interact with specific

signaling molecules to regulate gene expression (126).

The present study discovered six novel sequence

motifs within the lncRNA sequences under investigation. These

lncRNAs exhibited altered expression levels upon the activation of

NRs, either increasing or decreasing in abundance. Notably, several

of these lncRNAs, which contain at least one of the identified

motifs, are regulated by multiple NRs. This suggests that these

motifs may be associated with NR function but do not show

specificity to any single receptor, underscoring the complexity of

the regulatory network between NRs and ncRNAs. This finding

highlights the importance of further research to explore their

broader biological implications.

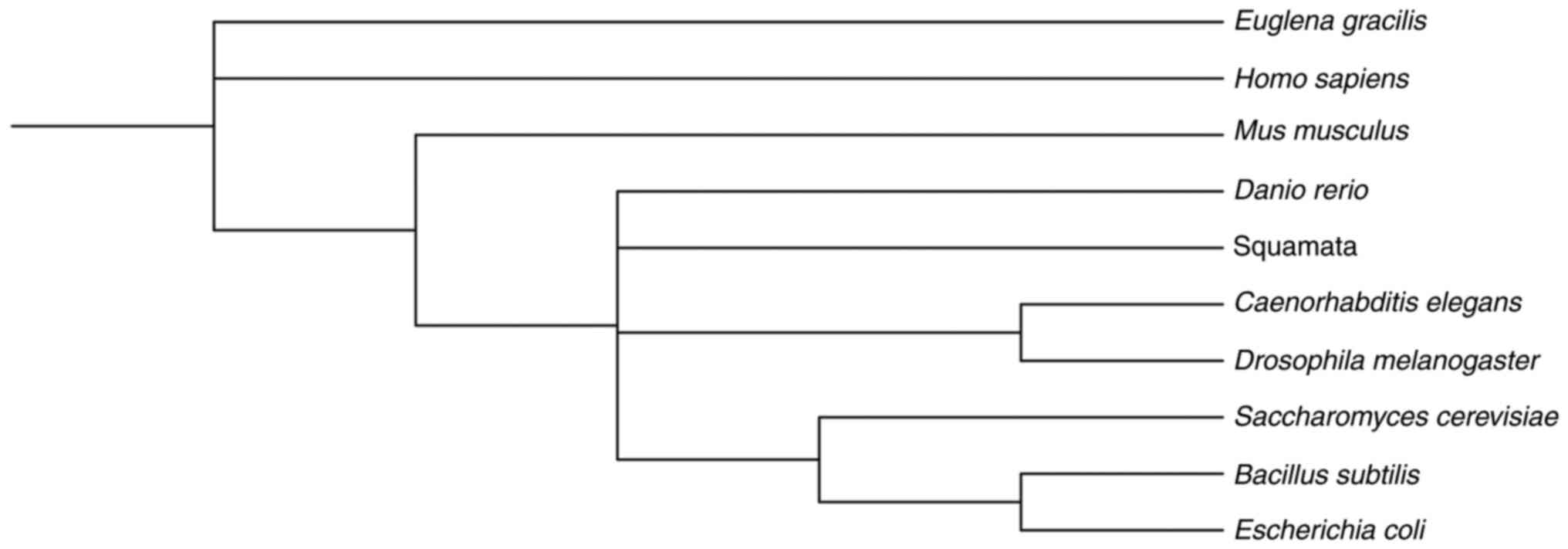

To investigate the evolutionary conservation of

these motifs, the FIMO tool was applied to examine their presence

in various organisms. The present study analyzed species such as

Mus musculus, Squamata (lizard), Danio rerio

(zebrafish), Drosophila melanogaster, Caenorhabditis elegans,

Escherichia coli (K12 MG1655), Saccharomyces cerevisiae

and Bacillus subtilis (PY79). Additionally, the present

study explored the presence of these motifs in the genome of

Euglena gracilis using the ‘Matcher’ tool on the Galaxy

platform. A phylogenetic tree was subsequently constructed using

the iTOL tool (Interactive Tree Of Life), which enabled the

visualization and annotation of the evolutionary associations among

the organisms and the conservation of the motifs across species

(127). The resulting phylogenetic

tree (Fig. 7) clearly illustrates

the evolutionary conservation of these motifs, which were

identified repeatedly in the studied organisms (Table II).

| Table IIOccurrence frequency of the motifs in

the genome sequences of the species Mus musculus, Squamata

(lizard), Danio rerio (zebrafish), Drosophila

melanogaster, Caenorhabditis elegans, Escherichia coli,

Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Bacillus subtilis (PY79) and

Euglena gracilis. |

Table II

Occurrence frequency of the motifs in

the genome sequences of the species Mus musculus, Squamata

(lizard), Danio rerio (zebrafish), Drosophila

melanogaster, Caenorhabditis elegans, Escherichia coli,

Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Bacillus subtilis (PY79) and

Euglena gracilis.

| Species | Motif 1 | Motif 2 | Motif 3 | Motif 4 | Motif 5 | Motif 6 |

|---|

| Mus

musculus | 61,755 | 83,484 | 56,870 | 64,325 | 81,207 | 81,748 |

| Squamata

(lizard) | 50,267 | 53,382 | 98,626 | 52,822 | 51,308 | 59,874 |

| Danio

rerio | 66,238 | 91,870 | 54,896 | 91,910 | 97,171 | 42,731 |

| Drosophila

melanogaster | 41,658 | 35,397 | 29,320 | 33,960 | 44,610 | 60,662 |

| Caenorhabditis

elegans | 42,982 | 20,446 | 21,768 | 29,076 | 27,321 | 40,169 |

| Escherichia

coli | 903 | 682 | 644 | 679 | 1269 | 760 |

| Saccharomyces

cerevisiae | 3,060 | 2,386 | 3,416 | 3,110 | 3,770 | 5,483 |

| Bacillus

subtilis | 912 | 663 | 662 | 638 | 865 | 830 |

| Euglena

gracilis | 364 | 1,657 | 1,278 | 541 | 522 | 1,711 |

The genetic similarities between humans and the

other organisms examined in the present study exhibit significant

variation. For instance, humans and Mus musculus (mouse)

share ~85% genetic similarity, reflecting a divergence of ~70

million years ago, making the mouse an essential model for human

genetic research, particularly in disease mechanisms and

therapeutic development (128).

Squamata, a diverse group of reptiles, includes species that serve

as critical models for studying thermoregulation, behavior and

reproductive strategies. Research on lizards and snakes has

provided important insights into immunity, skin regeneration, and

other physiological processes crucial for survival in varied

environments (129). The genetic

similarity between humans and different Squamata species varies

considerably, with lizards sharing ~70% genetic similarity with

humans, diverging ~250 million years ago. The six motifs identified

in the present study were also present in Squamata, suggesting

their ancient evolutionary origins. Danio rerio (zebrafish),

with a genetic similarity to humans of ~70%, diverged ~400 million

years ago and is an critical model organism for developmental

biology and gene function studies (130). Drosophila melanogaster

(fruit fly), sharing ~60% of its genes with humans and diverging

~600 million years ago, is extensively used in genetic regulation,

neurobiology, and cellular research (131). Caenorhabditis elegans

(nematode), with ~40% genetic similarity to humans, has been

instrumental in research on aging, developmental biology and

cellular processes (132).

Escherichia coli K12 MG1655, although lacking direct gene

homologs in humans, plays a crucial role in understanding

fundamental gene regulation and bacterial genetics (133). Saccharomyces cerevisiae

(yeast) shares ~23% of its genes with humans and diverged from

humans >1 billion years ago, rendering it a key organism for

cell biology, genomics and metabolism research (134). Bacillus subtilis PY79, a

soil bacterium, has markedly contributed to the understanding of

bacterial gene regulation and stress responses (135). Finally, Euglena gracilis, a

single-celled eukaryote, is considered to share ancient NR

mechanisms with humans, offering insights into the early evolution

of eukaryotic gene regulation (136).

The presence of the discovered motifs in species

that diverged long before humans, including organisms with distinct

genomes, such as Euglena gracilis and Saccharomyces

cerevisiae, combined with the lack of specificity in these

motifs, suggests they may represent ancestral binding sites for the

precursors of NRs. The conservation of these motifs across a broad

evolutionary spectrum emphasizes their potential role in regulating

gene expression via NR binding. Given that these motifs do not

exhibit specificity for any particular NR, it was hypothesized that

they may have functioned as general binding sites for ancestral NR

precursors (137). Moreover, these

motifs play a crucial role in the evolution of NR function by

enabling NRs to interact with a broader range of binding sites,

facilitating gene regulation in response to environmental and

internal cues (126,138).

The widespread presence of these motifs across

different evolutionary lineages points to their ancient origins,

likely predating the highly specific NRs found in modern organisms.

In early eukaryotes, these motifs could have functioned as genomic

binding sites for precursor forms of NRs, which were less specific

in their binding preferences compared to the more specialized NRs

currently observed (139). This

generalization would have been essential in the early stages of NR

evolution, allowing for flexible and robust gene regulation. These

early, versatile genomic binding sites could have allowed

primordial NR-like proteins to modulate gene expression

effectively, even in the absence of the highly refined

receptor-genome interactions seen in contemporary systems.

The conservation of these motifs across such

diverse species also suggests that they may have functioned as

backup mechanisms, ensuring the continued regulation of essential

genes when canonical NR binding sites, such as the glucocorticoid

response element for GR, were unavailable or dysfunctional

(139). In this sense, these

motifs may have served as a safety net, allowing the NR system to

maintain gene expression and cellular functions even in the absence

of optimal binding site availability. This backup role would have

been particularly important in the early evolutionary stages, when

the molecular machinery for precise gene regulation was still

evolving (140).

As NRs became more specialized through evolution,

the ancestral motifs likely persisted due to their role in

maintaining regulatory flexibility. In modern organisms, these

motifs may still contribute to the robustness of gene regulation,

particularly in cases where the canonical NR-binding sites are

compromised or unable to function. Their ability to interact with

multiple NRs enhances the adaptability of the organism to different

signaling environments, providing a more versatile and resilient

regulatory system (140).

The preservation of these motifs across such a

broad evolutionary spectrum underscores their importance in the

evolutionary trajectory of gene regulation. These motifs may

represent a foundational aspect of NR functionality, offering a

mechanism that allowed early organisms to adapt to changing

environments by ensuring continued gene regulation, even when

specific receptor-binding sites were not fully evolved. The fact

that these motifs can still be found in modern organisms suggests

that they continue to play a role in gene regulation, particularly

in situations where canonical NR interactions are suboptimal or

unavailable (126).

This broader, more flexible role in gene regulation

may have allowed organisms to thrive in variable environments and

adapt to new challenges. The conservation of motifs across both

ancient and modern species highlights their functional importance

and their potential as key elements in maintaining the adaptability

of the NR signaling system throughout evolutionary history.

To date, numerous studies have examined and

described the potential function of lncRNAs in the regulation of

gene expression and their abilities to act as biomarkers or as

pharmaceutical targets, or even therapeutic molecules (141-144).

In the present study, six conserved motifs were detected for the

first time in the sequences of the lncRNAs studied which are

suggested to participate in the regulatory function of lncRNAs that

contain them. However, to fully understand the role of these

motifs, and the lncRNAs containing them, in gene regulation, future

research is required to explore their functional significance in

greater detail. Experimental studies could confirm whether these

motifs act as alternative binding sites for NRs or other

transcription factors. Additionally, further investigations into

the mechanisms through which these motifs contribute to the

regulation of gene expression in both ancient and modern species

are warranted to provide valuable insight into the evolution of

NR-mediated gene regulation and its ongoing role in cellular

adaptability.

Supplementary Material

The first discovered motif in the

upregulated lncRNA subgroup.

The second discovered motif in the

upregulated lncRNA subgroup.

The third discovered motif in the

upregulated lncRNA subgroup.

The first discovered motif in the

downregulated lncRNA subgroup.

The second discovered motif in the

downregulated lncRNA subgroup.

The third discovered motif in the

downregulated lncRNA subgroup.

Human karyotype in which the

percentage of the occurrence of motif 1 in each chromosome is

presented.

Human karyotype in which the

percentage of the occurrence of motif 2 in each chromosome is

presented.

Human karyotype in which the

percentage of the occurrence of motif 3 in each chromosome is

presented.

Human karyotype in which the

percentage of the occurrence of motif 4 in each chromosome is

presented.

Human karyotype in which the

percentage of the occurrence of motif 5 in each chromosome is

presented.

Human karyotype in which the

percentage of the occurrence of motif 6 in each chromosome is

presented.

Chromosome plot for the 1,000

higher-scored loci of motif 1 in the human genome which are

presented as red dots next to the corresponding chromosomal region

where they are located.

Chromosome plot for the 1,000

higher-scored loci of motif 2 in the human genome which are

presented as red dots next to the corresponding chromosomal region

where they are located.

Chromosome plot for the 1,000

higher-scored loci of motif 3 in the human genome which are

presented as red dots next to the corresponding chromosomal region

where they are located.

Chromosome plot for the 1,000

higher-scored loci of motif 4 in the human genome which are

presented as red dots next to the corresponding chromosomal region

where they are located.

Chromosome plot for the 1,000

higher-scored loci of motif 5 in the human genome which are

presented as red dots next to the corresponding chromosomal region

where they are located.

Chromosome plot for the 1,000

higher-scored loci of motif 6 in the human genome which are

presented as red dots next to the corresponding chromosomal region

where they are located.

Multiple alignment of the sequences of

motif 1 with AAVS1 site using Clustal Omega (51) visualized with JalView (52).

Multiple alignment of the sequences of

motif 2 with AAVS1 site using Clustal Omega (51) visualized with JalView (52).

Multiple alignment of the sequences of

motif 3 with AAVS1 site using Clustal Omega (51) visualized with JalView (52).

Multiple alignment of the sequences of

motif 4 with AAVS1 site using Clustal Omega (51) visualized with JalView (52).

Multiple alignment of the sequences of

motif 5 with AAVS1 site using Clustal Omega (51) visualized with JalView (52).

Multiple alignment of the sequences of

motif 6 with AAVS1 site using Clustal Omega (51) visualized with JalView (52).

The biological pathways in which the

lncRNAs that contain the motif 1 participate and have a regulatory

function, according to GeneCards (https://www.genecards.org/) and NCBI Gene (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/)

databases.

The biological pathways in which the

lncRNAs that contain the motif 2 participate and have a regulatory

function, according to GeneCards (https://www.genecards.org/) and NCBI Gene (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/)

databases.

The biological pathways in which the

lncRNAs that contain the motif 3 participate and have a regulatory

function, according to GeneCards (https://www.genecards.org/) and NCBI Gene (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/)

databases.

The biological pathways in which the

lncRNAs that contain the motif 4 participate and have a regulatory

function, according to GeneCards (https://www.genecards.org/) and NCBI Gene (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/)

databases.

The biological pathways in which the

lncRNAs that contain the motif 5 participate and have a regulatory

function, according to GeneCards (https://www.genecards.org/) and NCBI Gene (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/)

databases.

The biological pathways in which the

lncRNAs that contain the motif 6 participate and have a regulatory

function, according to GeneCards (https://www.genecards.org/) and NCBI Gene (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/)

databases.

Data S1

Data S2

Data S1

The dataset of the lncRNAs that are

either upregulated or downregulated following the activation of an

NR.

List of 487 transcripts which are

targets of hsa-miR-1908-3p according to the TargetScanS (Release

8.0) database.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The authors would like to acknowledge funding from the

following organizations: i) AdjustEBOVGP-Dx (RIA2018EF-2081):

Biochemical Adjustments of native EBOV Glycoprotein in Patient

Sample to Unmask target Epitopes for Rapid Diagnostic Testing. A

European and Developing Countries Clinical Trials Partnership

(EDCTP2) under the Horizon 2020 ‘Research and Innovation Actions’

DESCA; and ii) ‘MilkSafe: A novel pipeline to enrich formula milk

using omics technologies’, a research co-financed by the European

Regional Development Fund of the European Union and Greek national

funds through the Operational Program Competitiveness,

Entrepreneurship and Innovation, under the call

RESEARCH-CREATE-INNOVATE (project code: T2EDK-02222).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

DV conceived the study. DV, GPC, EE and KP

contributed to the overall study design. KP and LP developed the

in-house algorithms in MATLAB. KP, EE and DV performed and

evaluated the analysis using bioinformatics tools, as well as the

statistical analysis. KP, LP, GPC, EE and DV wrote, drafted and

critically revised the manuscript. DV, LP and KP confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. KP, LP, GPC, EE and DV wrote,

drafted, revised, edited and reviewed the manuscript. All authors

have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

GPC is the Editor in Chief of the journal, and DV

and EE are Editors of the journal. However, they had no personal

involvement in the reviewing process, or any influence in terms of

adjudicating on the final decision, for this article. The other

authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

|

1

|

Carninci P, Kasukawa T, Katayama S, Gough

J, Frith MC, Maeda N, Oyama R, Ravasi T, Lenhard B, Wells C, et al:

The transcriptional landscape of the mammalian genome. Science.

309:1559–1563. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Mattick JS: RNA regulation: A new

genetics? Nat Rev Genet. 5:316–323. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Frith MC, Pheasant M and Mattick JS: The

amazing complexity of the human transcriptome. Eur J Hum Genet.

13:894–897. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Kaikkonen MU, Lam MTY and Glass CK:

Non-coding RNAs as regulators of gene expression and epigenetics.

Cardiovasc Res. 90:430–440. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Harrow J, Frankish A, Gonzalez JM,

Tapanari E, Diekhans M, Kokocinski F, Aken BL, Barrell D, Zadissa

A, Searle S, et al: GENCODE: The reference human genome annotation

for The ENCODE project. Genome Res. 22:1760–1774. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Salviano-Silva A, Lobo-Alves SC, Almeida

RC, Malheiros D and Petzl-Erler ML: Besides pathology: Long

non-coding RNA in cell and tissue homeostasis. Noncoding RNA.

4(3)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Ma L, Bajic VB and Zhang Z: On the

classification of long non-coding RNAs. RNA Biol. 10:925–933.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Wang KC and Chang HY: Molecular mechanisms

of long noncoding RNAs. Mol Cell. 43:904–914. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Hombach S and Kretz M: Non-coding RNAs:

Classification, biology and functioning. Adv Exp Med Biol.

937:3–17. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Rinn JL and Chang HY: Genome regulation by

long noncoding RNAs. Annu Rev Biochem. 81:145–166. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Francis GA, Fayard E, Picard F and Auwerx

J: Nuclear receptors and the control of metabolism. Annu Rev

Physiol. 65:261–311. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Olivares AM, Moreno-Ramos OA and Haider

NB: Role of nuclear receptors in central nervous system development

and associated diseases. J Exp Neurosci. 9 (Suppl 2):S93–S121.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Foulds CE, Panigrahi AK, Coarfa C, Lanz RB

and O'Malley BW: Long noncoding RNAs as targets and regulators of

nuclear receptors. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 394:143–176.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Volders PJ, Helsens K, Wang X, Menten B,

Martens L, Gevaert K, Vandesompele J and Mestdagh P: LNCipedia: A

database for annotated human lncRNA transcript sequences and

structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 41 (Database Issue):D246–D251.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Bailey TL, Williams N, Misleh C and Li WW:

MEME: Discovering and analyzing DNA and protein sequence motifs.

Nucleic Acids Res. 34 (Web Server Issue):W369–W373. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Liu W and Wang X: Prediction of functional

microRNA targets by integrative modeling of microRNA binding and

target expression data. Genome Biol. 20(18)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Agarwal V, Bell GW, Nam JW and Bartel DP:

Predicting effective microRNA target sites in mammalian mRNAs.

Elife. 4(e05005)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Garcia DM, Baek D, Shin C, Bell GW,

Grimson A and Bartel DP: Weak seed-pairing stability and high

target-site abundance decrease the proficiency of lsy-6 and other

microRNAs. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 18:1139–1146. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Grimson A, Farh KK, Johnston WK,

Garrett-Engele P, Lim LP and Bartel DP: MicroRNA targeting

specificity in mammals: Determinants beyond seed pairing. Mol Cell.

27:91–105. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Goecks J, Nekrutenko A and Taylor J:

Galaxy Team. Galaxy: A comprehensive approach for supporting

accessible, reproducible, and transparent computational research in

the life sciences. Genome Biol. 11(R86)2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Afgan E, Baker D, van den Beek M,

Blankenberg D, Bouvier D, Čech M, Chilton J, Clements D, Coraor N,

Eberhard C, et al: The Galaxy platform for accessible, reproducible

and collaborative biomedical analyses: 2016 update. Nucleic Acids

Res. 44 (W1):W3–W10. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Durbin R, Eddy SR, Krogh A and Mitchison

G: Biological sequence analysis: Probabilistic Models of Proteins

and Nucleic Acids. Cambridge University Press, 1998.

|

|

23

|

Ha M and Kim VN: Regulation of microRNA

biogenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 15:509–524. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Broughton JP, Lovci MT, Huang JL, Yeo GW

and Pasquinelli AE: Pairing beyond the seed supports microRNA

targeting specificity. Mol Cell. 64:320–333. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

John B, Enright AJ, Aravin A, Tuschl T,

Sander C and Marks DS: Human MicroRNA targets. PLoS Biol.

2(e363)2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Betel D, Koppal A, Agius P, Sander C and

Leslie C: Comprehensive modeling of microRNA targets predicts

functional non-conserved and non-canonical sites. Genome Biol.

11(R90)2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Krek A, Grün D, Poy MN, Wolf R, Rosenberg

L, Epstein EJ, MacMenamin P, da Piedade I, Gunsalus KC, Stoffel M

and Rajewsky N: Combinatorial microRNA target predictions. Nat

Genet. 37:495–500. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Lewis BP, Shih IH, Jones-Rhoades MW,

Bartel DP and Burge CB: Prediction of mammalian microRNA targets.

Cell. 115:787–798. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Lewis BP, Burge CB and Bartel DP:

Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that

thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell. 120:15–20.

2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Miranda KC, Huynh T, Tay Y, Ang YS, Tam

WL, Thomson AM, Lim B and Rigoutsos I: A pattern-based method for

the identification of MicroRNA binding sites and their

corresponding heteroduplexes. Cell. 126:1203–1217. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Kertesz M, Iovino N, Unnerstall U, Gaul U

and Segal E: The role of site accessibility in microRNA target

recognition. Nat Genet. 39:1278–1284. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Rehmsmeier M, Steffen P, Hochsmann M and

Giegerich R: Fast and effective prediction of microRNA/target

duplexes. RNA. 10:1507–1517. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Maragkakis M, Alexiou P, Papadopoulos GL,

Reczko M, Dalamagas T, Giannopoulos G, Goumas G, Koukis E, Kourtis

K, Simossis VA, et al: Accurate microRNA target prediction

correlates with protein repression levels. BMC Bioinformatics.

10(295)2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Karagkouni D, Paraskevopoulou MD,

Chatzopoulos S, Vlachos IS, Tastsoglou S, Kanellos I, Papadimitriou

D, Kavakiotis I, Maniou S, Skoufos G, et al: DIANA-TarBase v8: A

decade-long collection of experimentally supported miRNA-gene

interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 46 (D1):D239–D245. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

McGeary SE, Lin KS, Shi CY, Pham TM,

Bisaria N, Kelley GM and Bartel DP: The biochemical basis of

microRNA targeting efficacy. Science. 366(eaav1741)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Yang L, Shi CM, Chen L, Pang LX, Xu GF, Gu

N, Zhu LJ, Guo XR, Ni YH and Ji CB: The biological effects of

hsa-miR-1908 in human adipocytes. Mol Biol Rep. 42:927–935.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Kuang Q, Li J, You L, Shi C, Ji C, Guo X,

Xu M and Ni Y: Identification and characterization of NF-kappaB

binding sites in human miR-1908 promoter. Biomed Pharmacother.

74:158–163. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Bar M, Wyman SK, Fritz BR, Qi J, Garg KS,

Parkin RK, Kroh EM, Bendoraite A, Mitchell PS, Nelson AM, et al:

MicroRNA discovery and profiling in human embryonic stem cells by

deep sequencing of small RNA libraries. Stem Cells. 26:2496–2505.

2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Pencheva N, Tran H, Buss C, Huh D,

Drobnjak M, Busam K and Tavazoie SF: Convergent multi-miRNA

targeting of ApoE drives LRP1/LRP8-dependent melanoma metastasis

and angiogenesis. Cell. 151:1068–1082. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Xia X, Li Y, Wang W, Tang F, Tan J, Sun L,

Li Q, Sun L, Tang B and He S: MicroRNA-1908 functions as a

glioblastoma oncogene by suppressing PTEN tumor suppressor pathway.

Mol Cancer. 14(154)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Chai Z, Fan H, Li Y, Song L, Jin X, Yu J,

Li Y, Ma C and Zhou R: miR-1908 as a novel prognosis marker of

glioma via promoting malignant phenotype and modulating SPRY4/RAF1

axis. Oncol Rep. 38:2717–2726. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Jiang X, Yang L, Pang L, Chen L, Guo X, Ji

C, Shi C and Ni Y: Expression of obesity-related miR-1908 in human

adipocytes is regulated by adipokines, free fatty acids and

hormones. Mol Med Rep. 10:1164–1169. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Grimwood J, Gordon LA, Olsen A, Terry A,

Schmutz J, Lamerdin J, Hellsten U, Goodstein D, Couronne O,

Tran-Gyamfi M, et al: The DNA sequence and biology of human

chromosome 19. Nature. 428:529–535. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Kumar S, Stecher G, Suleski M and Hedges

SB: TimeTree: A resource for timelines, timetrees, and divergence

times. Mol Biol Evol. 34:1812–1819. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Kim SH, Elango N, Warden C, Vigoda E and

Yi SV: Heterogeneous genomic molecular clocks in primates. PLoS

Genet. 2(e163)2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Kotin RM, Menninger JC, Ward DC and Berns

KI: Mapping and direct visualization of a region-specific viral DNA

integration site on chromosome 19q13-qter. Genomics. 10:831–834.

1991.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Samulski RJ, Zhu X, Xiao X, Brook JD,

Housman DE, Epstein N and Hunter LA: Targeted integration of

adeno-associated virus (AAV) into human chromosome 19. EMBO J.

10:3941–3950. 1991.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Kotin RM, Linden RM and Berns KI:

Characterization of a preferred site on human chromosome 19q for

integration of adeno-associated virus DNA by non-homologous

recombination. EMBO J. 11:5071–5078. 1992.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Aslanidis C, Jansen G, Amemiya C, Shutler

G, Mahadevan M, Tsilfidis C, Chen C, Alleman J, Wormskamp NG,

Vooijs M, et al: Cloning of the essential myotonic dystrophy region

and mapping of the putative defect. Nature. 355:548–551.

1992.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Feichtinger W and Schmid M: Increased

frequencies of sister chromatid exchanges at common fragile sites

(1)(q42) and (19)(q13). Hum Genet. 83:145–147. 1989.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Sievers F and Higgins DG: Clustal Omega

for making accurate alignments of many protein sequences. Protein

Sci. 27:135–145. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Waterhouse AM, Procter JB, Martin DMA,

Clamp M and Barton GJ: Jalview Version 2-a multiple sequence

alignment editor and analysis workbench. Bioinformatics.

25:1189–1191. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Deaton AM and Bird A: CpG islands and the

regulation of transcription. Genes Dev. 25:1010–1022.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Larsen F, Gundersen G, Lopez R and Prydz

H: CpG islands as gene markers in the human genome. Genomics.

13:1095–1107. 1992.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Yamashita R, Suzuki Y, Sugano S and Nakai

K: Genome-wide analysis reveals strong correlation between CpG

islands with nearby transcription start sites of genes and their

tissue specificity. Gene. 350:129–136. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Lamartina S, Sporeno E, Fattori E and

Toniatti C: Characteristics of the adeno-associated virus

preintegration site in human chromosome 19: Open chromatin

conformation and transcription-competent environment. J Virol.

74:7671–7677. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Bhagwan JR, Collins E, Mosqueira D, Bakar

M, Johnson BB, Thompson A, Smith JGW and Denning C: Variable

expression and silencing of CRISPR-Cas9 targeted transgenes

identifies the AAVS1 locus as not an entirely safe harbour.

F1000Res. 8(1911)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Ogata T, Kozuka T and Kanda T:

Identification of an insulator in AAVS1, a preferred region for

integration of adeno-associated virus DNA. J Virol. 77:9000–9007.

2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Gaspar HB, Cooray S, Gilmour KC, Parsley

KL, Zhang F, Adams S, Bjorkegren E, Bayford J, Brown L, Davies EG,

et al: Hematopoietic stem cell gene therapy for adenosine

deaminase-deficient severe combined immunodeficiency leads to

long-term immunological recovery and metabolic correction. Sci

Transl Med. 3(97ra80)2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Cartier N, Hacein-Bey-Abina S, Bartholomae

CC, Veres G, Schmidt M, Kutschera I, Vidaud M, Abel U, Dal-Cortivo

L, Caccavelli L, et al: Hematopoietic stem cell gene therapy with a

lentiviral vector in X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy. Science.

326:818–823. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Hacein-Bey-Abina S, Pai SY, Gaspar HB,

Armant M, Berry CC, Blanche S, Bleesing J, Blondeau J, de Boer H,

Buckland KF, et al: A modified γ-retrovirus vector for X-linked

severe combined immunodeficiency. N Engl J Med. 371:1407–1417.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Martin DIK and Whitelaw E: The vagaries of

variegating transgenes. Bioessays. 18:919–923. 1996.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Bestor TH: Gene silencing as a threat to

the success of gene therapy. J Clin Invest. 105:409–411.

2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Papapetrou EP and Schambach A: Gene

insertion into genomic safe harbors for human gene therapy. Mol

Ther. 24:678–684. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Wu C and Dunbar CE: Stem cell gene

therapy: The risks of insertional mutagenesis and approaches to

minimize genotoxicity. Front Med. 5:356–371. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Lombardo A, Cesana D, Genovese P, Di

Stefano B, Provasi E, Colombo DF, Neri M, Magnani Z, Cantore A, Lo

Riso P, et al: Site-specific integration and tailoring of cassette

design for sustainable gene transfer. Nat Methods. 8:861–869.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

67

|

Klatt D, Cheng E, Hoffmann D, Santilli G,

Thrasher AJ, Brendel C and Schambach A: Differential transgene

silencing of myeloid-specific promoters in the AAVS1 safe harbor

locus of induced pluripotent stem cell-derived myeloid cells. Hum

Gene Ther. 31:199–210. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

68

|

Papapetrou EP, Lee G, Malani N, Setty M,

Riviere I, Tirunagari LM, Kadota K, Roth SL, Giardina P, Viale A,

et al: Genomic safe harbors permit high β-globin transgene

expression in thalassemia induced pluripotent stem cells. Nat

Biotechnol. 29:73–78. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

69

|

Sadelain M, Papapetrou EP and Bushman FD:

Safe harbours for the integration of new DNA in the human genome.

Nat Rev Cancer. 12:51–58. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

70

|

Smith SD, Morgan R, Gemmell R, Amylon MD,

Link MP, Linker C, Hecht BK, Warnke R, Glader BE and Hecht F:

Clinical and biologic characterization of T-cell neoplasias with

rearrangements of chromosome 7 band q34. Blood. 71:395–402.

1988.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Maes OC, Chertkow HM, Wang E and Schipper