Introduction

Cancer remains one of the leading causes of

mortality worldwide, with the number of new cases rising each year.

Chemotherapy, although a mainstay in cancer treatment, is

associated with high toxicity and significant side-effects. This

approach targets not only tumor cells, but also healthy cells,

resulting in severe adverse outcomes such as nausea, fatigue, organ

damage and immune suppression. These effects often necessitate

treatment interruption, thereby compromising therapeutic efficacy

(1). Furthermore, the development

of resistance to chemotherapeutic agents remains a major challenge

in cancer treatment (2). These

limitations underscore the need for alternative adjuvant therapies

capable of exerting antitumor effects without inducing toxicity,

thereby allowing for reduced dosage and/or duration of conventional

chemotherapy without compromising efficacy. Natural compound-based

therapies have shown promise as complementary strategies that

improve the quality of life of patients and support uninterrupted

treatment.

Brazil harbors a vast biodiversity of plants

containing natural bioactive compounds with a high biotechnological

potential for the pharmaceutical industry. Among these, a wide

variety of plant-derived polysaccharides have attracted

considerable attention for their immunomodulatory and antitumor

properties. Pectins, a family of covalently linked D-galacturonic

acid-rich polysaccharides abundant in the primary cell walls of

fruits, exhibit diverse biological activities, including

anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, immunoregulatory and antitumor

effects, and may also serve as carriers for targeted drug delivery

(3). In numerous fruits, pectic

polysaccharide structures undergo chemical and enzymatic

modifications during ripening, leading to substantial

intramolecular changes in the pectic chain (4). Pectins derived from diverse

biological sources are known to exhibit considerable structural

variability, and such differences in chemical composition have been

associated with distinct biological activities. Notably,

accumulating evidence indicates that pectins may exert antitumor

effects through the modulation of tumor cell proliferation,

adhesion and apoptosis (3). Pectin

derived from papaya has been shown to reduce the viability and

induce the necroptosis of colon and prostate cancer cell lines

(5). Previous studies have

demonstrated that pectic polysaccharides extracted from potatoes

(6) and sugar beet (7) significantly inhibited the

proliferation of HT-29 cells in vitro. Furthermore, apple

pectin has been reported to promote the apoptosis and reduce the

adhesion of 4T1 breast cancer cells (8). Notably, pectins display low toxicity

and minimal side-effects on normal cells compared to conventional

chemotherapeutic agents (9). These

properties highlight pectins as molecules with potential to serve

as adjuvants in cancer therapy, exerting antitumor effects and

potentially enabling a reduction in the use of chemotherapeutic

agents associated with severe side effects.

Prunes are the dried fruits of Prunus

domestica L. (European plum; P. domestica), a tree

cultivated on all continents, with its fruits widely consumed

worldwide (10). Pectins extracted

from P. domestica fruits have been reported to exhibit

antioxidant (11),

gastroprotective (12,13) and anti-inflammatory activities

(14). Recently, Vaz da Luz et

al (15) demonstrated that

isolated side chains of pectins (type I arabinogalactans) with

different molar masses, obtained from prune tea infusions,

displayed varying antitumor effects. However, unlike the study by

Vaz da Luz et al (15), the

present study aimed to evaluate the antitumor activity of pectins

present in the prune pectic fraction obtained with hot water (PWH),

which consists of a mixture of rhamnogalacturonans with type I

arabinogalactan side chains and low-methyl-esterified

homogalacturonan (13). It is

well-established that a mixture of pectic polysaccharides in

solution can elicit different biological effects compared to those

produced by individual polysaccharide chains (4). To the best of our knowledge, the

antitumor activity of pectins in the PWH fraction has not been

previously investigated, which justifies the present

investigation.

In light of the above, the present study aimed to

evaluate the antitumor activity of the PWH fraction obtained from

prunes in B16F10 murine melanoma cells. The present study assessed

its cytotoxicity on both tumor and normal cells, as well as its

effects on tumor cell migration, colony formation and

morphology.

Materials and methods

Purification, characterization and

solubilization of polysaccharide fraction

The prune pectin fraction (PWH) was characterized

and kindly provided by the Department of Biochemistry at the

Federal University of Paraná (Paraná, Brazil). Pitted prunes (dried

fruits from P. domestica purchased at a local market in

Curitiba, Brazil; LA VIOLETERA®) were freeze-dried and

milled. The extraction of pectic polysaccharides was carried out

using hot water in order to obtain the molecules more tightly bound

to the cell wall. Moreover, hot-water extraction results in a

higher pectin yield compared to cold-water extraction. The water

extract was obtained by filtration, and the polysaccharides were

recovered by ethanol (3 vol.) precipitation and lyophilization,

originating the fractions. A homogeneous fraction was analyzed by

sugar composition, high-performance steric exclusion

chromatography, methylation, and nuclear magnetic resonance

spectroscopy analyses. The PWH comprises rhamnogalacturonans with

type I arabinogalactans as side chains, and low-methyl esterified

homogalacturonan (9). The

freeze-dried pectin fraction was solubilized in the cell growth

medium [RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.),

supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) and 1% antibiotic (penicillin 10,000 U and

streptomycin 10 mg/l), MilliporeSigma] and stored at -20˚C until

its use.

Cell groups were divided into a control group (CT)

and a group treated with prune pectins (PWH). The control group

received only the cell growth medium without PWH. For cytotoxicity

analysis, doxorubicin (DX, Pfizer®) at a concentration

of 2.5 µg/ml was used as a positive control. In this case, the same

control medium was used, supplemented with the chemotherapy

drug.

Cell lines and cell culture

The B16F10 murine melanoma cell line (BCRJ, 0046)

and BALB/c 3T3 normal cell line (clone A31, ATCC, CCL-163) were

kindly provided by the Laboratory of Inflammatory and Neoplastic

Cells, Department of Cell Biology, UFPR, Curitiba, Brazil, and were

initiated and maintained according to specific recommendations for

each line. The BALB/c 3T3 cell line, derived from fibroblasts of

BALB/c mouse embryos, is non-tumorigenic and widely employed as a

representative model of normal cells in contrast to tumor cell

lines. Given that fibroblasts are distributed throughout the body,

this lineage provides an appropriate model for assessing normal

cell function in studies of viability and cytotoxicity. Cells were

cultured in growth medium and maintained in an incubator (Sanyo

Scientific MCO-18AC) at 37˚C, 90% humidity, and 5% CO2

for 72 h. All experiments were performed in biological

triplicates.

Analysis of cell viability

To determine the concentrations to be used in the

present study, a cell viability and cytotoxicity test was carried

out to determine the concentrations that were not cytotoxic to

normal cells. For this, the colorimetric tests of reduction of

diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) and neutral red (NR) were

performed by the protocols proposed by Mosmann (16) and Repetto et al (17), respectively. The B16F10 cells

(5x102 cells/well) and BALB/c 3T3 (2x103

cells/well) were exposed to 0, 2.5, 5, 10, 100 and 800 µg/ml PWH,

and 2.5 µg/ml DX for 72 h. Briefly, the MTT cell viability assay

was performed by first seeding the cells into 96-well plates and

treating them as described in the experimental design. Following

treatment, the wells were aspirated to remove the culture medium

(RPMI-1640, MilliporeSigma; containing fetal bovine serum 10%

Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), and 100 µl MTT solution

[3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide 5

mg/ml in PBS, MilliporeSigma, pH 7.4] were added to each well. The

plates were incubated for 3.5 h at 37˚C in a humidified atmosphere

with 5% CO2 to allow the formation of formazan crystals

by metabolically active cells. Following incubation, the MTT

solution was discarded, and 100 µl dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO,

MilliporeSigma) were added to each well to solubilize the formazan

crystals. The plates were gently shaken to ensure complete

solubilization, and the absorbance was measured at 540 nm using a

microplate reader (TECAN® Infinite M200; Tecan Group,

Ltd.). The absorbance values obtained were directly proportional to

the number of viable cells.

The neutral red cell viability assay was performed

by first treating cells cultured in 96-well plates according to the

experimental protocol. Following treatment, the medium (RPMI-1640,

MilliporeSigma; containing fetal bovine serum 10% Gibco; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was removed, and 100 µl Neutral Red

solution (MilliporeSigma, 40 µg/ml in culture medium) were added to

each well. The cells were then incubated for 3 h at 37˚C in a 5%

CO2 atmosphere to allow dye uptake by viable cells.

Following incubation, the dye solution was removed, and the cells

were washed gently with 150 µl PBS (MilliporeSigma) to eliminate

excess dye. Subsequently, 100 µl destaining solution (50% ethanol,

49% distilled water, and 1% glacial acetic acid, MilliporeSigma)

was added to each well to extract the dye from the lysosomes. The

plate was shaken until the complete solubilization of the dye, and

the absorbance was measured at 540 nm using a microplate reader

(TECAN® Infinite M200). The absorbance values obtained

were directly proportional to the number of viable cells. The

results obtained from the MTT and neutral red assays (measured by

absorbance) were converted into percentages, using the control

group (without treatment with the PWH fraction) as having 100%

viability.

Cytotoxicity assay

The assay was performed through the crystal violet

method, as previously described by Bonnekoh et al (18). The B16F10 cells (2x103

cells/well) were plated in a new 96-well plate and exposed to 0, 10

and 100 µg/ml PWH. Cell viability was measured in 24, 48 and 72 h.

Following the treatment period, the medium (RPMI-1640

MilliporeSigma; containing fetal bovine serum 10% Gibco; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was removed, and the cells were gently

washed with 150 µl PBS to eliminate non-adherent cells and debris.

Subsequently, 100 µl of 4% paraformaldehyde solution

(MilliporeSigma) were added to each well to fix the cells for 20

min at room temperature. Following fixation, the wells were washed

again with PBS, and 100 µl 0.1% crystal violet solution (prepared

in 20% methanol, Merck KGaA) were added to stain the cells at room

temperature for 10 min. Excess dye was removed by rinsing the plate

under running distilled water until the background was clear. After

drying, the bound dye was solubilized by the addition of 100 µl 10%

acetic acid (MilliporeSigma) to each well. The plate was gently

shaken to ensure complete solubilization. The results were obtained

using a TECAN® Infinite M200 device at 590 nm. The data

are presented as a percentage relative to the CT group at 24 h.

Cell migration (wound healing)

assay

Following 72 h of exposure to 0, 10 and 100 µg/ml

PWH, the B16F10 surviving cells were plated again (2x104

cells/well) in a new 96-well plate with culture medium (RPMI-1640

MilliporeSigma; containing fetal bovine serum 10% Gibco; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) to perform the cell migration assay

(‘scratch’ method) (19). Briefly,

after the cells reached full confluency, cell proliferation was

inhibited with the use of RPMI growth medium lacking in FBS (1%),

and a straight scratch was made in the monolayer using a sterile

200 µl pipette tip. The wells were then gently washed with PBS to

remove detached cells. Images of the scratch area were captured

immediately (0 h) and following 24 h of incubation at 37˚C in a 5%

CO2 atmosphere using an inverted microscope

(BIOVAL® XDS-1B). The wound closure area was analyzed

using ImageJ® software 1.52 (National Institutes of

Health), and the migration rate was expressed as the percentage of

area covered by cells after 24 h compared to time 0(20).

Colony formation assay

Following 72 h of exposure to 0, 10 and 100 µg/ml

PWH, B16F10 surviving cells were plated again at a reduced

concentration (1x102 cells/well) in a 24-well plate to

perform the colony formation assay analyses (21). This assay is expected to evaluate

the ability of a single cell to form new colonies. For this,

surviving cells were maintained only in the growth medium

(RPMI-1640 MilliporeSigma; containing fetal bovine serum 10% Gibco;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and incubated at 37˚C for 96 h. At

the end of the incubation period, the colonies were fixed with 4%

paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 15 min and then stained

with 0.1% crystal violet solution (prepared in 20% methanol) for 10

min at room temperature. Excess dye was washed off with distilled

water, and the plates were dried in air. The images were acquired

using an inverted microscope (BIOVAL® XDS-1B), and

colonies containing >50 cells were counted using

ImageJ® software 1.52 (National Institutes of

Health).

Analysis of cell morphology

This assay aimed to evaluate morphological changes

in B16F10 cells following exposure to the PWH fraction. The cells

(5x10³ cells/well) were seeded in 24-well plates and treated with

0, 10, or 100 µg/ml PWH. Cell morphology was assessed at the start

of treatment and again after 24 h. At each time point, the cells

were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 10 min

and stained with 0.25% crystal violet (prepared in methanol) at

room temperature for 10 min (22).

The area occupied by the cells in culture was quantified through

digital analysis of images captured using a light microscope

(BIOVAL® XDS-1B) at x400 magnification. Images were

processed using ImageJ software 1.52 (National Institutes of

Health), applying threshold-based segmentation to differentiate

cells from the background. The total cell area was subsequently

measured in pixels.

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

RNA isolation from the B16F10 cell samples following

72 h of PWH treatment was performed using TRIzol®

reagent (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) according to the

manufacturer's recommendations. The extracted RNA samples were then

converted to cDNA using the iScript Reverse Transcription Supermix

for RT-qPCR kit (cat. no. 1708841, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). The

reactions were taken to the thermocycler (Applied Biosystems;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), and the samples were incubated in

three cycles: 1st cycle of 5 min at 25˚C, 2nd cycle of 20 min at

46˚C, and 3rd cycle of 1 min at 95˚C. The RT-qPCR reaction was

performed using the one-step RT-PCR SYBR®-Green kit

(cat. no. 1725270, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) and the appropriate

primers for each reaction, as follows: Focal adhesion kinase (FAK)

forward, 5'-TCTGTGGAATTGGCAATCGG-3' and reverse,

5'-TGGATGGTCTGCACTTGGTT-3'; beta actin (ACTB) forward,

5'-CTGTATTCCCCTCCATCGTG-3' and reverse,

5'-GGGTCAGGATACCTCTCTTGC-3'; hypoxanthine-guanine

phosphoribosyltransferase (HPRT1) forward,

5'-GTTGGGCTTACCTCACTGCT-3' and reverse, 5'-TAATCACGACGCTGGGACTG-3'.

The samples were analyzed in a QuantStudioTM 5 device (Applied

Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). For each reaction, a

control RT (without conversion of RNA to cDNA) was performed. The

relative quantification was measured according to the pre-set

threshold fluorescence level of the target gene (FAK) compared to

the endogenous controls used (ACTB and HPRT1). ACTB and HPRT1 were

utilized for normalization. The quality and purity of total RNA

were evaluated using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). Samples exhibited A260/A280 ratios between 1.8

and 2.0 and A260/A230 ratios >1.8, indicating minimal

contamination by proteins or phenolic compounds and falling within

commonly accepted parameters for gene expression analysis. For each

RT-qPCR reaction, 4.5 µl cDNA, synthesized from a standardized RNA

concentration of 10 ng/µl, was used, corresponding to 45 ng total

RNA per reaction. The assay performance was monitored using two

endogenous reference genes (ACTB and HPRT1), selected for their

stability across the analyzed Mus musculus samples.

No-reverse transcriptase (RT-) controls were included to confirm

the absence of genomic DNA contamination. Each sample was tested in

triplicate, and the relative gene levels were normalized using the

2-ΔΔCq method (23).

Statistical analysis

The normal distribution of values was verified using

the Shapiro-Wilk test. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's test was

performed in all analyses, apart from cell proliferation, which was

analyzed using two-way ANOVA (mixed model) followed by the

Bonferroni post hoc test, both through GraphPad Prism8

Software® (Dotmatics). P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference. Tukey's test was

used as a post hoc test. Data are presented as the mean ± SD of at

least three independent experiments.

Results

Cell viability

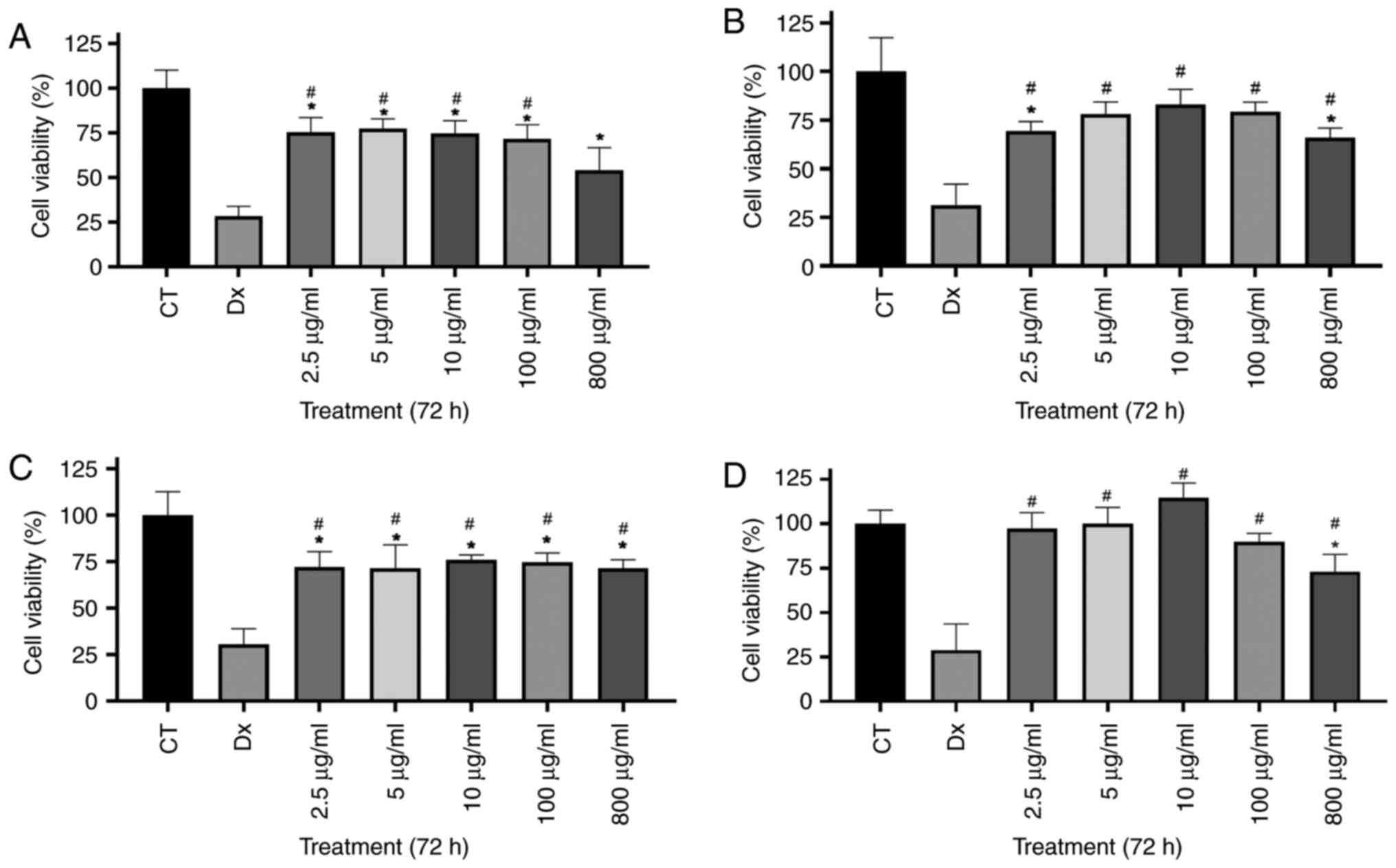

In the NR assay, all PWH concentrations

significantly reduced the viability of the B16F10 cells compared

with the CT group (Fig. 1A). In

the BALB/c 3T3 cells, a significant reduction was observed only

following treatment with 2.5 and 800 µg/ml PWH in relation to the

CT group (Fig. 1B). The MTT assay

revealed a similar viability profile for the B16F10 cells as in the

NR assay (Fig. 1C). In the BALB/c

3T3 cells, cytotoxicity was detected only following treatment with

800 µg/ml PWH, although it remained lower than that induced by DX

(Fig. 1D). Overall, PWH was less

cytotoxic than DX across all concentrations and assays (Fig. 1A-C), apart from the concentration

of 800 µg/ml in the NR assay (Fig.

1A). These assays suggest that the PWH fraction exhibits

greater cytotoxicity toward tumor cells than toward normal

cells.

Cytotoxicity assay

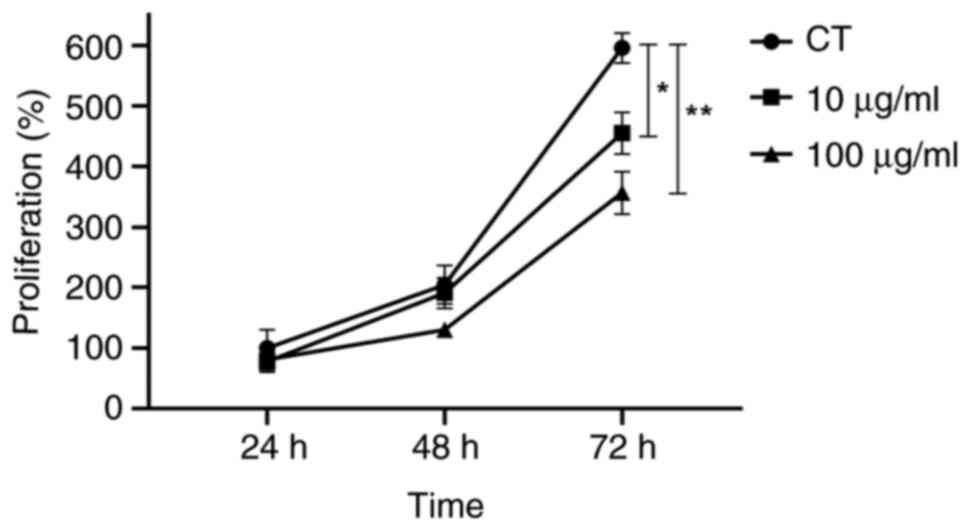

Based on the cell viability data, concentrations

were selected to avoid cytotoxic effects on normal cells while

effectively reducing tumor cell viability. Subsequent experiments

were performed using 10 and 100 µg/ml PWH, with the control (CT)

group remaining polysaccharide-free (0 µg/ml). The results

demonstrated the cytotoxicity of the PWH fraction on tumor cells

over time. PWH did not significantly affect cell viability at 24 or

48 h compared to the CT group. However, after 72 h, viability was

markedly reduced at both concentrations, with decreases of 23.6 and

40.3%, respectively (Fig. 2).

Cell migration and colony formation

capacity

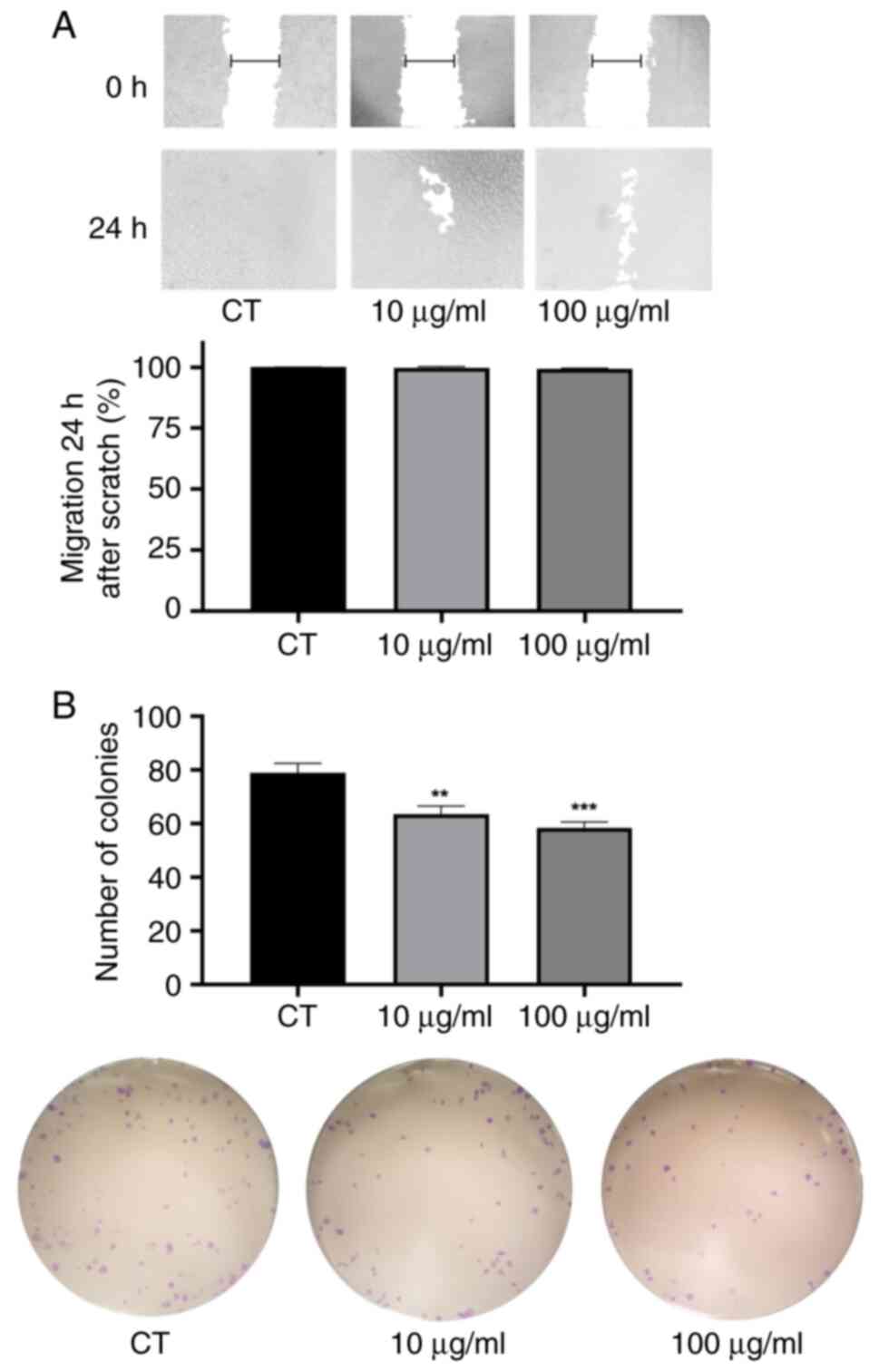

In the migration assay, tumor cells treated with the

PWH fraction closed the scratch to a similar extent as untreated

cells, indicating that PWH did not significantly impair cell

migration at either concentration within 24 h (Fig. 3A).

By contrast, PWH effectively reduced colony

formation at both concentrations. Compared to the CT group, the

number of new colonies decreased by 19.6% in the cells treated with

10 µg/ml PWH and by 25.9% in those exposed to 100 µg/ml PWH

(Fig. 3B). These data indicated

that tumor cells exhibited a reduced proliferation and diminished

colony formation capacity following treatment with PWH.

Area occupied by cultured cells

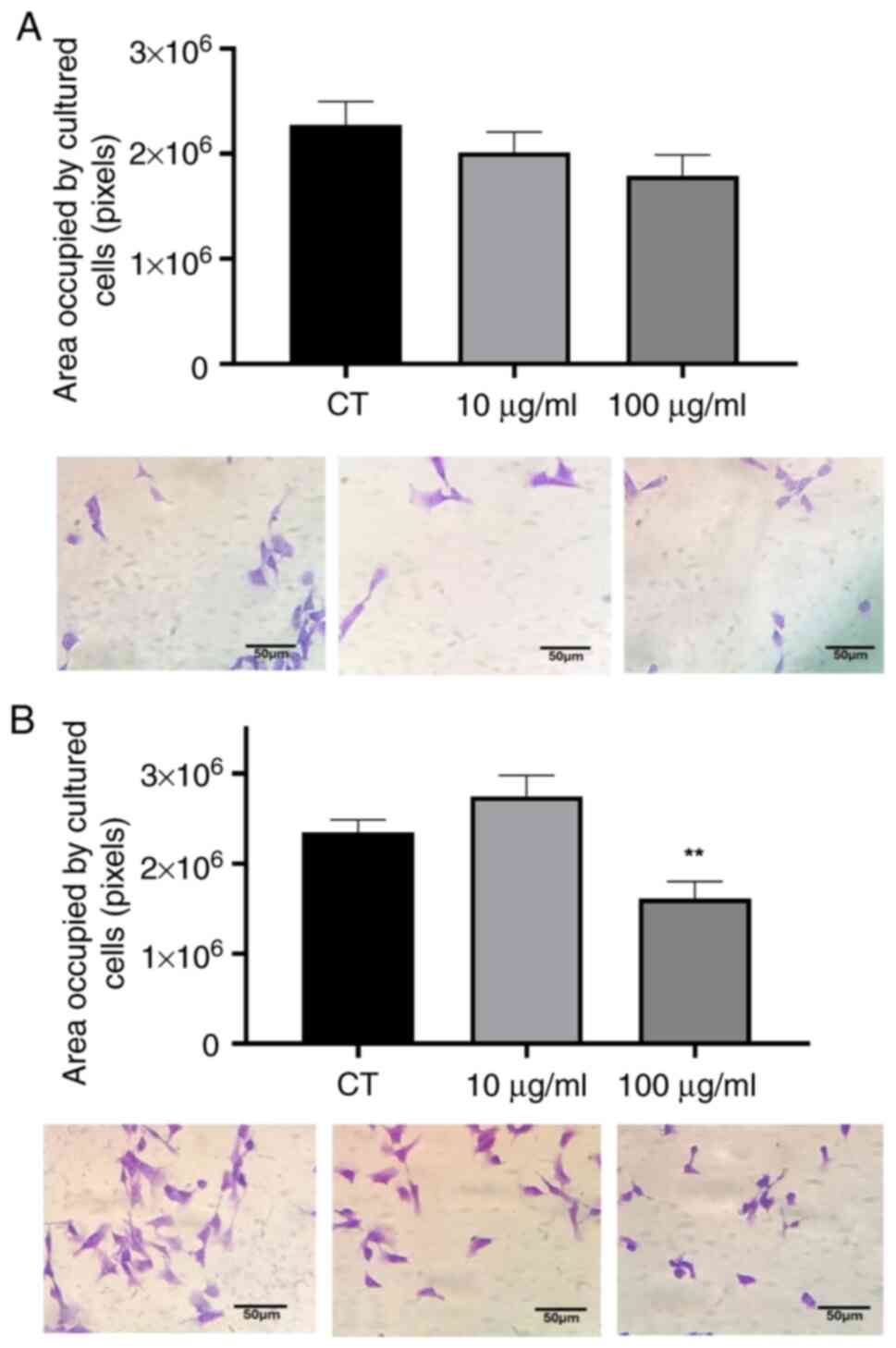

Morphological changes were observed in the cells

exposed to PWH under an inverted microscope. To confirm and further

investigate these changes, a detailed morphological analysis was

performed. Immediately after treatment (0 h), no noticeable

differences were detected between the treated and control cells

(Fig. 4A). However, following 24 h

of exposure, the cells treated with 100 µg/ml PWH exhibited a 30%

reduction in the area occupied by cultured cells compared to the

control group (Fig. 4B),

suggesting that contact with the polysaccharides in the PWH

fraction interfered with the cytoskeletal organization of tumor

cells.

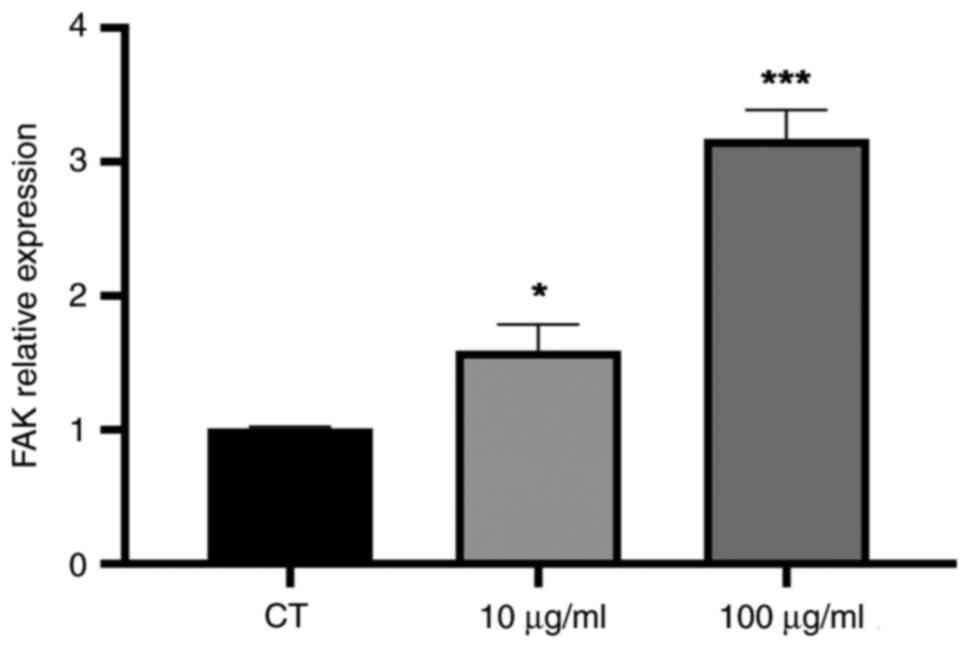

RT-qPCR

Based on the observed effects on cell proliferation,

colony formation and morphology, it was hypothesized that PWH may

influence the focal adhesion points of cells. To determine this,

FAK gene expression was quantified. FAK is a central regulator that

promotes focal adhesion to the extracellular matrix and

cytoskeletal remodeling. The results revealed the altered

expression of the FAK gene in the B16F10 cells treated with PWH,

with a 57% increase at the concentration of 10 µg/ml and a 3-fold

increase at the concentration of 100 µg/ml (Fig. 5).

Discussion

The results of the present study demonstrated that

PWH exerted specific effects on B16F10 cells, including reduced

viability, decreased colony formation, fewer cytoplasmic extensions

and an altered FAK gene expression. These changes are closely

linked to melanoma differentiation and invasiveness (24-26).

Even the lowest concentration of PWH (2.5 µg/ml) was sufficient to

reduce B16F10 cell viability following 72 h of treatment. From a

pharmacological perspective, the ability to decrease cancer cell

viability at low concentrations are highly desirable (27). It was also observed that the

reduction in cell viability was similar at both low and high

concentrations, a phenomenon previously reported in studies

involving pectins (28). Notably,

the effect of PWH on normal cell viability was substantially lower

than that of DX, consistent with other reports highlighting the low

toxicity of pectins (29,30).

Cell cytotoxicity assays over time are essential for

understanding the mechanisms of action of any proposed treatment.

In the present study, a concentration-dependent reduction in tumor

cell viability was observed after 72 h of exposure to PWH. Similar

effects of pectins on tumor cell cultures have been reported in

other studies (5,31,32).

Of note, despite the 10-fold difference between the lowest and

highest PWH concentrations (10 and 100 µg/ml), the effect on B16F10

cell viability was not proportionally greater at the higher

concentration. This suggests that the impact of the PWH fraction on

cell viability may reach a plateau beyond a certain concentration,

indicating that the cellular pathways involved are already fully

modulated, and increasing the concentration to 100 µg/ml does not

further enhance the response. Indeed, a similar non-proportional

reduction in viability with increasing concentrations of a

comparable polysaccharide fraction has been reported previously

(33).

Pectins from various sources have been reported to

reduce tumor cell migration (34,35),

including the migration of B16F10 cells (36). In contrast, in the present study,

treatment with PWH did not produce significant changes in the

migration rate of B16F10 cells. Nevertheless, the potential effect

of the polysaccharides on cell migration cannot be ruled out, as

the present study focused solely on migration at 0 and 24 h after

scratch creation, which may have overlooked any early delays in

movement immediately following the ‘wound’. Additionally, employing

alternative techniques to evaluate migratory capacity could provide

further insights.

The process of metastasis involves not only the

ability of cells to migrate, but also the capacity of a single cell

to proliferate and form a new colony in a tissue different from its

primary origin. Studies investigating the effects of

polysaccharides on tumor cell colony formation have reported

promising results (37,38). These findings are consistent with

those of the present study, in which PWH significantly reduced

colony formation at its highest concentration (100 µg/ml).

In the present study, PWH at 100 µg/ml reduced the

cytoplasmic area of B16F10 cells. Since cell-cell contact is a key

mechanism for proliferation, the reduction in cell area and

dendritic projections may lead to decreased release of critical

growth factors necessary for sustaining cell proliferation

(39). Furthermore, the data

presented herein indicated that exposure to PWH was associated with

a reduced cell area alongside increased FAK gene expression in

B16F10 murine melanoma cells. Cytoskeletal reorganization plays a

crucial role in the adaptation of a cell to specific exogenous

stimuli or inhibitors present in the surrounding microenvironment.

Consequently, the signaling proteins involved in this

reorganization are essential for maintaining cell morphology and

regulating biophysical dynamics (40). Focal adhesion sites are specialized

regions where the cytoskeleton connects with the extracellular

matrix (ECM). These sites rely on the coordinated activity of

integrins, the cytoskeleton and signaling proteins, such as FAK and

Src. They are essential for maintaining cellular architecture and

sensing mechanical cues from the environment. The FAK-Src pathway

can be activated by various signals involved in cell survival,

invasion and adhesion. FAK is a central regulator of tumor cell

motility and invasiveness. Upon activation, via integrin-ECM

interactions or growth factor signaling, FAK autophosphorylates at

Tyr397 and recruits Src kinases, promoting focal adhesion turnover

and cytoskeletal remodeling through targets such as paxillin,

p130Cas and Rho GTPases. FAK signaling also enhances MMP-2 and

MMP-9 expression, supporting extracellular matrix degradation and

invasion, and contributes to invadopodia formation and EMT-like

phenotypes in melanoma (25,41).

Notably, research has shown that an increased FAK expression is

directly associated with heightened cancer aggressiveness (42), which is in contrast to the findings

of the present study. However, it was hypothesized that the pectins

present in PWH may impair cell adhesion to the surrounding

environment. This could explain why, unable to adhere efficiently

to their microenvironment, the cells remodel their cytoskeleton and

display a reduced morphology compared to the control group.

Consequently, in the absence of optimal adhesion and spreading, a

compensatory mechanism may be triggered, leading cells to

upregulate FAK in an attempt to form additional focal adhesion

points for survival. Further detailed investigations of the

mechanisms involved in the FAK-Src signaling pathway are required

to clarify these findings.

The present study has certain limitations which

should be mentioned. The analysis of additional genes related to

cell proliferation and migration/invasion, as well as their

corresponding protein expression, was not performed here and should

be addressed in future work.

In conclusion, the pectins from prunes present in

the PWH fraction reduced the viability of B16F10 murine melanoma

cells, while exhibiting minimal toxicity toward normal BALB/c 3T3

cells, exhibiting lower cytotoxicity than the chemotherapeutic

agent DX. Additionally, PWH inhibited malignant colony formation

and appeared to affect focal adhesion in the B16F10 cell line.

These results provide preliminary evidence supporting PWH as a

potential compound for future cancer research.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Dr Edvaldo da Silva

Trindade and Dr Fernanda Fogagnoli Simas from the Laboratory of

Inflammatory and Neoplastic Cells - Federal University of Paraná,

Curitiba, Brazil, for kindly providing the cell lines.

Funding

Funding: The present study was funded by the Araucaria

Foundation (Official Agreement no. 051/2017), CNPq (grant nos.

404717/2026-0, 310731/2021-6 and 403295/2021-1), and fellowships

from CAPES (Funding code 001, PROEX - Grant no.

88881.924191/2023-01).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

APB, SCSB and RFA conducted the assays. GDOF and FFW

analyzed the photo-derived data. LMCC isolated and characterized

the polysaccharides. MHA contributed to the experimental design. KN

and LCF assisted in the analysis and discussion of the results. FI

was involved in the experimental design, and data analysis and

interpretation. APB and FI confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Use of artificial intelligence tools

During the preparation of this work, AI tools were

used to improve the readability and language of the manuscript or

to generate images, and subsequently, the authors revised and

edited the content produced by the AI tools as necessary, taking

full responsibility for the ultimate content of the present

manuscript.

References

|

1

|

Hossain MB and Haldar Neer AH:

Chemotherapy. Cancer Treat Res. 185:49–58. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Riganti C and Contino M: New strategies to

overcome resistance to chemotherapy and immune system in cancer.

Int J Mol Sci. 20(4783)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Sultana N: Biological properties and

biomedical applications of pectin and pectin-based composites: A

review. Molecules. 28(7974)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Pedrosa LF, Raz A and Fabi JP: The complex

biological effects of pectin: Galectin-3 targeting as potential

human health improvement? Biomolecules. 12(289)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Prado SBRD, Ferreira GF, Harazono Y, Shiga

TM, Raz A, Carpita NC and Fabi JP: Ripening-induced chemical

modifications of papaya pectin inhibit cancer cell proliferation.

Sci Rep. 7(16564)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Ogutu FO, Mu TH, Sun H and Zhang M:

Ultrasonic modified sweet potato pectin induces apoptosis like cell

death in colon cancer (HT-29) cell line. Nutr Cancer. 70:136–145.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Maxwell EG, Colquhoun IJ, Chau HK,

Hotchkiss AT, Waldron KW, Morris VJ and Belshaw NJ: Modified sugar

beet pectin induces apoptosis of colon cancer cells via an

interaction with the neutral sugar side-chains. Carbohydr Polym.

136:923–929. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Delphi L and Sepehri H: Apple pectin: A

natural source for cancer suppression in 4T1 breast cancer cells in

vitro and express p53 in mouse bearing 4T1 cancer tumors, in vivo.

Biomed Pharmacother. 84:637–644. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Li DQ, Li J, Dong HL, Li X, Zhang JQ,

Ramaswamy S and Xu F: Pectin in biomedical and drug delivery

applications: A review. Int J Biol Macromol. 185:49–65.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Ortega-Vidal J, Ruiz-Martos L, Salido S

and Altarejos J: Proanthocyanidins in pruning wood extracts of four

european plum (Prunus domestica L.) cultivars and their hLDHA

inhibitory activity. Chem Biodivers. 20(e202200931)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Konrade D, Gaidukovs S, Vilaplana F and

Sivan P: Pectin from fruit- and berry-juice production by-products:

Determination of physicochemical, antioxidant and rheological

properties. Foods. 12(1615)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Markov PA, Paderin NM, Chelpanova TI,

Efimtseva EA, Nikitina IR and Popov SV: Gastroprotective and

antidepressant-like effect of plum pectin (Prunus domestica L.)

under water-immobilization stress in laboratory mice. Vopr Pitan.

92:16–25. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar : (In Russian).

|

|

13

|

Cantu-Jungles TM, Maria-Ferreira D, da

Silva LM, Baggio CH, Werner MF, Iacomini M, Cipriani TR and

Cordeiro LM: Polysaccharides from prunes: Gastroprotective activity

and structural elucidation of bioactive pectins. Food Chem.

146:492–499. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Popov SV, Ovodova RG, Golovchenko VV,

Khramova DS, Markov PA, Smirnov VV, Shashkov AS and Ovodov YS:

Pectic polysaccharides of the fresh plum Prunus domestica L.

isolated with a simulated gastric fluid and their anti-inflammatory

and antioxidant activities. Food Chem. 143:106–113. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Vaz da Luz KT, Gonçalves JP, de Lima

Bellan D, Visnheski BRC, Schneider VS, Cortes Cordeiro LM, Vargas

JE, Puga R, da Silva Trindade E, de Oliveira CC and Simas FF:

Molecular weight-dependent antitumor effects of prunes-derived type

I arabinogalactan on human and murine triple wild-type melanomas.

Carbohydr Res. 535(108986)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Mosmann T: Rapid colorimetric assay for

cellular growth and survival: Application to proliferation and

cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods. 65:55–63. 1983.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Repetto G, del Peso A and Zurita JL:

Neutral red uptake assay for the estimation of cell

viability/cytotoxicity. Nat Protoc. 3:1125–1131. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Bonnekoh B, Wevers A, Jugert F, Merk H and

Mahrle G: Colorimetric growth assay for epidermal células cultures

by their crystal violet binding capacity. Arch Dermatol Res.

281:487–490. 1989.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Liang CC, Park AY and Guan JL: In vitro

scratch assay: A convenient and inexpensive method for analysis of

cell migration in vitro. Nat Protoc. 2:329–333. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Borges BE, Appel MH, Cofré AR, Prado ML,

Steclan CA, Esnard F, Zanata SM, Laurindo FR and Nakao LS: The

flavo-oxidase QSOX1 supports vascular smooth muscle cell migration

and proliferation: Evidence for a role in neointima growth. Biochim

Biophys Acta. 1852:1334–1346. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Boia-Ferreira M, Basílio AB, Hamasaki AE,

Matsubara FH, Appel MH, Da Costa CRV, Amson R, Telerman A, Chaim

OM, Veiga SS and Senff-Ribeiro A: TCTP as a therapeutic target in

melanoma treatment. Br J Cancer. 117:656–665. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Naliwaiko K, Luvizon AC, Donatti L,

Chammas R, Mercadante AF, Zanata SM and Nakao LS: Guanosine

promotes B16F10 melanoma cell differentiation through PKC-ERK 1/2

pathway. Chem Biol Interact. 173:122–128. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Maddodi N and Setaluri V: Prognostic

significance of melanoma differentiation and trans-differentiation.

Cancers (Basel). 2:989–999. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Qi X, Chen Y, Liu S, Liu L, Yu Z, Yin L,

Fu L, Deng M, Liang S and Lü M: Sanguinarine inhibits melanoma

invasion and migration by targeting the FAK/PI3K/AKT/mTOR

signalling pathway. Pharm Biol. 61:696–709. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Raineri A, Fasoli S, Campagnari R, Gotte G

and Menegazzi M: Onconase restores cytotoxicity in

dabrafenib-resistant A375 human melanoma cells and affects cell

migration, invasion and colony formation capability. Int J Mol Sci.

20(5980)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Cobs-Rosas M, Concha-Olmos J,

Weinstein-Oppenheimer C and Zúñiga-Hansen ME: Assessment of

antiproliferative activity of pectic substances obtained by

different extraction methods from rapeseed cake on cancer cell

lines. Carbohydr Polym. 117:923–932. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Amaral SDC, Barbieri SF, Ruthes AC, Bark

JM, Brochado Winnischofer SM and Silveira JLM: Cytotoxic effect of

crude and purified pectins from Campomanesia xanthocarpa Berg on

human glioblastoma cells. Carbohydr Polym.

224(115140)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Chen GT, Fu YX, Yang WJ, Hu QH and Zhao

LY: Effects of polysaccharides from the base of Flammulina

velutipes stipe on growth of murine RAW264.7, B16F10 and L929

cells. Int J Biol Micromol. 107:2150–2156. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Xiang T, Yang R, Li L, Lin H and Kai G:

Research progress and application of pectin: A review. J Food Sci.

89:6985–7007. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Prado SBRD, Santos GRC, Mourão PAS and

Fabi JP: Chelate-soluble pectin fraction from papaya pulp interacts

with galectin-3 and inhibits colon cancer cell proliferation. Int J

Biol Macromol. 126:170–178. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Wu XQ, Fu JY, Mei RY, Dai XJ, Li JH, Zhao

XF and Liu MQ: Inhibition of liver cancer HepG2 cell proliferation

by enzymatically prepared low-molecular citrus pectin. Curr Pharm

Biotechnol. 23:861–872. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Angeli RF, Bialli AP, Baal SCS, dos Santos

EF, Filho PSL, Schneider VS, Fernandes LC, Naliwaiko K, Cordeiro

LMC and Iagher F: Antitumor activity of polysaccharides obtained

from guavira fruit industrial waste on murine melanoma cells.

Bioact Carbohydrates Diet Fibre. 33(100469)2025.

|

|

34

|

Fan Y, Sun L, Yang S, He C, Tai G and Zhou

Y: The roles and mechanisms of homogalacturonan and

rhamnogalacturonan I pectins on the inhibition of cell migration.

Int J Biol Macromol. 106:207–217. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

do Prado SBR, Shiga TM, Harazono Y, Hogan

VA, Raz A, Carpita NC and Fabi JP: Migration and proliferation of

cancer cells in culture are differentially affected by molecular

size of modified citrus pectin. Carbohydr Polym. 211:141–151.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Wikiera A, Kozioł A, Mika M and Stodolak

B: Structure and bioactivity of apple pectin isolated with

arabinanase and mannanase. Food Chem 15:.

388(133020)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Cao XY, Liu JL, Yang W, Hou X and Li QJ:

Antitumor activity of polysaccharide extracted from Pleurotus

ostreatus mycelia against gastric cancer in vitro and in vivo. Mol

Med Rep. 12:2383–2389. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Adami ER, Corso CR, Turin-Oliveira NM,

Galindo CM, Milani L, Stipp MC, do Nascimento GE, Chequin A, da

Silva LM, de Andrade SF, et al: Antineoplastic effect of pectic

polysaccharides from green sweet pepper (Capsicum annuum) on

mammary tumor cells in vivo and in vitro. Carbohydr Polym.

201:280–292. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Vayssade M, Sengkhamparn N, Verhoef R,

Delaigue C, Goundiam O, Vigneron P, Voragen AG, Schols HA and Nagel

MD: Antiproliferative and proapoptotic actions of okra pectin on

B16F10 melanoma cells. Phytother Res. 24:982–989. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Nikkhah M, Strobl JS, De Vita R and Agah

M: The cytoskeletal organization of breast carcinoma and fibroblast

cells inside three dimensional (3-D) isotropic silicon

microstructures. Biomaterials. 31:4552–4561. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Xu B, Song G and Ju Y: Effect of focal

adhesion kinase on the regulation of realignment and tenogenic

differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells by mechanical

stretch. Connect Tissue Res. 51:373–379. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Zhao J and Guon JL: Signal transduction by

focal adhesion kinase in cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 28:35–40.

2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|