Introduction

Skeletal muscle atrophy is a complex biochemical

process occurring under various pathophysiological conditions in

adult animals, such as disuse (e.g., immobilization, denervation,

muscle unloading), starvation, aging and in syndromes, such as

cachexia (1). It is important to

understand the molecular mechanisms underlying skeletal muscle

atrophy and to develop effective strategies to delay its onset

(2–4). Denervation-induced muscle atrophy

has received attention as it is commonly encountered in clinical

practice and is very likely to cause extreme adverse effects

(5,6). A number of factors that contribute

to denervation-induced muscle atrophy have been identified,

including neuromuscular alterations, altered protein synthesis and

degradation, and apoptosis-induced muscle fiber loss (7–10).

However, previous studies have mainly focused on single gene and/or

protein changes potentially linked to skeletal muscle atrophy.

Therefore, a global investigation of the protein expression changes

may help to decipher the molecular basis of denervation-induced

skeletal muscle atrophy.

Proteomics is a well-established approach for

simultaneously detecting the expression of a high number of

proteins in biological samples. Among the different proteomic

techniques, isobaric tags for relative and absolute quantification

(iTRAQ) labeling, albeit initially developed on the basis of

traditional two-dimensional electrophoresis (2-DE), is particularly

suitable and has proven to far surpass 2-DE in sample coverage and

protein separation efficiency (11). iTRAQ coupled with two-dimensional

liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (2D LC-MS/MS)

represents a state-of-the art tool, extensively used to identify

and quantify differential proteomes.

In this study, we first examined the protein

expression profile in denervated tibialis anterior (TA) muscle

following sciatic nerve transection in rats, and then classified

the differentially expressed proteins using Gene Ontology (GO)

functional annotation and the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and

Genomes (KEGG) pathway terms, so as to investigate the functional

implications of differential expression in TA muscle during

denervation-induced atrophy. Additional protein-protein interaction

analysis revealed that the tumor necrosis factor

receptor-associated factor-6 (TRAF6) protein was also

differentially expressed in denervated TA muscle, although this

protein was not detected in our proteomics analysis, possibly due

to its low abundance. TRAF6 knockdown experiments provided further

evidence of the biological significance of TRAF6 in skeletal muscle

atrophy.

Materials and methods

Animals and surgical procedures

Adult female Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats, weighing

180–220 g, were provided by the Experimental Animal Center of

Nantong University. The rats were randomly divided into 2 groups,

subsequently subjected to operation, and 1 control group (10 rats

in each group). Animal handling procedures followed the

Institutional Animal Care Guidelines of Nantong University and were

approved by the Administration Committee of Experimental Animals,

Jiangsu Province, China. The rats were subjected to sciatic nerve

transection (operated groups) or sham operation (control group), as

previously described (12). At 1

and 4 weeks following the operation, the TA muscles were rapidly

dissected from the operated side of the animals and immediately

immersed in liquid nitrogen prior to use. TA muscles were also

harvested from animals of the control group.

Protein sample preparation and iTRAQ

labeling

Protein samples were extracted from the harvested

muscles and quantified using the Protein Assay kit (Bio-Rad,

Hercules, CA, USA). iTRAQ labeling of the protein samples was

performed as previously described (12). Briefly, 100 μg of each protein

sample, obtained by acetone precipitation, was dissolved in 20 μl

of dissolution buffer and sequentially reduced, alkylated and

digested, followed by labeling with the iTRAQ tags 114, 115 and

116, and pooling for further analysis.

The mixed iTRAQ-labeled sample was resuspended in

buffer A (10 mM KH2PO4 in 25% v/v

acetonitrile at pH 2.7) and fractionated using an off-line strong

cation exchange column on a 1100 HPLC system (Agilent Technologies,

Waldbronn, Germany). Gradient elution was performed from 0% buffer

B (10 mM KH2PO4 in 25% v/v acetonitrile/350

mM KCL at pH 2.7) to 25% buffer B for 30 min, and then from 25%

buffer B to 100% buffer B for 20 min. The fractions were collected

at 2-min intervals, and desalted on Vivapure® C18 Micro

spin columns (Sartorius Stedim Biotech, Gottingen, Germany), and

vacuum-dried prior to LC/MS/MS analysis. All reagents used in these

procedures were purchased from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA,

USA).

2D LC-MS/MS

Online 2D nano LC-MS/MS analysis was performed as

previously described (12).

Briefly, the peptides in each fraction were resuspended in 20 μl

solvent A (water with 0.1% formic acid), separated by nano LC, and

analyzed by on-line electrospray tandem mass spectrometry using the

LTQ Orbitrap XL mass spectrometer (Thermo Electron Corp., Bremen,

Germany). An 18-μl peptide sample was loaded for 5 min, with a flow

of 20 μl/min, onto the peptide column Captrap (Michrom

BioResources, Auburn, CA, USA), and subsequently eluted with a

3-step linear gradient, starting from 5% solvent B (acetonitrile

with 0.1% formic acid) to 45% solvent B for 70 min, increased to

80% solvent B for 1 min, and then holding on 80% solvent B for 4

min. The electrospray voltage of 1.9 kV vs. the inlet of the mass

spectrometer was used.

A LTQ Orbitrap XL mass spectrometer was operated in

the data-dependent mode to switch automatically between MS and

MS/MS acquisition. Survey full-scan MS spectra (m/z 400–2,000) were

acquired with a mass resolution of 60,000 at m/z 400, followed by

MS/MS of the 4 most intense peptide ions. The dissociation mode was

higher energy C-trap dissociation (HCD), under which iTRAQ-labeled

peptides fragmented to produce reporter ions at 114.1, 115.1 and

116.1. Fragment ions of the peptides were simultaneously produced,

and sequencing of the labeled peptides allowed the identification

of the corresponding proteins. Dynamic exclusion was used with 2

repeat counts (10-sec repeat duration), and the m/z values

triggering MS/MS were placed on an exclusion list for 120 sec. For

MS/MS, precursor ions were activated using 40% normalized collision

energy and an activation time of 30 msec. The peak intensity of the

3 iTRAQ reporter ions reflected the relative abundance of the

peptides and thereby, proteins, in the samples.

Protein identification and

quantification

The MS raw data were analyzed as previously

described (12). Briefly, MS/MS

spectra were compared to rat data from the Swiss-Prot database

(Release 2010_04) using the SEQUEST software v.28 (revision 12;

Thermo Electron Corp.). The search parameters were set as follows:

trypsin (KR) cleavage with 2 miscleavages allowed;

carbamidomethylation of cysteine residues as fixed modification;

iTRAQ modification of peptide N-termini, methionine oxidation,

iTRAQ modification of lysine residues and N-terminal acetylation as

variable modifications; peptide mass tolerance 20 ppm, and fragment

ion tolerance 0.05 Da. Protein identification results were

evaluated using the Trans Proteomic Pipeline (TPP) set of tools

(revision 4.2), with quantification of iTRAQ reporter ion

intensities performed using the Libra tool.

For the selection of differentially expressed

proteins, we considered the following criteria, as previously

described (13): i) proteins

containing at least 2 unique high-scoring peptides; and ii)

proteins with a median ratio above 2 or below 0.5; and iii) >95%

confidence level in each comparison.

Bioinformatic analysis

The differentially expressed proteins were mapped to

the appropriate GO database to calculate the number of genes at

each node, and were classified according to molecular function. The

differentially expressed proteins were further classified into the

KEGG molecular pathway (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/pathway.html) to explore

specific biological pathways affected by skeletal muscle atrophy.

In addition, predicted protein-protein interactions for the list of

differentially expressed proteins and the resulting network were

retrieved and constructed using the STRING database version 9.0

(http://string-db.org) (14).

Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis was used to confirm the

expression of selected proteins as previously described (15). Briefly, muscle protein samples

were homogenized in RIPA buffer, separated by 1D electrophoresis

and electroblotted onto a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane.

The membrane was blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk in Tris-buffered

saline (TBS) for 1 h at room temperature, followed by incubation

with primary polyclonal antibodies: mouse anti-β-enolase (1:1,000;

BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA, USA) and rabbit anti-α-enolase

(1:500; AB Biotec, Stockholm, Sweden) in TBST (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH

7.5, 150 mM NaCl and 0.1% Tween-20) supplemented with 5% milk

overnight at 4°C. After washing in TBST, the membrane was incubated

with HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit/mouse IgG polyclonal antibody

(AB Biotec) for 60 min. Following TBST washes, immunoprobed

proteins were visualized using the enhanced chemiluminescence

method: Chemiluminescent solution luminol and hydrogen peroxide

were provided with the ECL luminescence kit (Pierce Corp.,

Rockford, IL, USA). HRP catalyzes the reaction of luminol with

hydrogen peroxide to generate a peroxide. The peroxide is unstable

and easy to decompose to form a luminescent electron excitation

energy intermediates, which will produce fluorescence, when the

electron excitation energy intermediates return from the excited

state to the ground state.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical analysis was performed as

described in a previous study (15). Briefly, the TA muscle was

dissected, post-fixed, dehydrated, and sectioned (8-μm-thick

sections) using a cryostat; the sections were thaw-mounted onto

poly-L-lysine-coated slides and stored at −20°C prior to

immunostaining. The slides were washed in phosphate-buffered saline

(PBS) for 10 min at room temperature, blocked, and then incubated

overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies: mouse anti-β-enolase

antibody and rabbit anti-α-enolase antibody (both at 1:100). After

washing with PBS, the slides were incubated at 4°C for 24 h with

secondary goat antibodies labeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate 1

(FITC): anti-mouse IgG-FITC (1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.,

Santa Cruz, CA, USA) and anti-rabbit IgG-FITC (1:200; Abcam,

Cambridge, MA, USA). The slides were washed 3 times in PBS,

coverslipped and visualized under a DMR fluorescent microscope

(Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany).

Cell culture and small interfering RNA

(siRNA) transfection

The cells were cultured as previously described

(16). Briefly, L6 skeletal

muscle cells were grown and maintained in high-glucose Dulbecco’s

modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine

serum (FBS), 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin in a

10% CO2 humidified atmosphere at 37°C. The cells grown

in culture flasks up to approximately 80% confluency were

trypsinized and seeded into a 6-well culture plate for incubation

in DMEM containing 10% FBS, until they reached approximately 90%

confluence. Following replacement of the medium with DMEM

containing 2% horse serum, the cells were induced to differentiate

until >90% had differentiated into myotubes. The resulting L6

myotubes were treated with 100 nM dexamethasone in 0.1% ethanol for

48 h. Dexamathasone is a glucocorticoid that induces myotube

atrophy (16).

TRAF6 siRNA oligonucleotides targeting rat TRAF6,

and control oligonucleotides (TRAF6 siRNA negative control) were

purchased from RiboBio Co., Ltd. (Guangzhou, China). Cells were

transfected using riboFect™ CP reagent (RiboBio Co., Ltd.)

according to the manufacturer’s instructions. L6 myotubes were

transfected with 100 nM TRAF6 siRNA or 100 nM negative control

siRNA. Six hours later, the medium was replaced with

differentiation medium. L6 myotubes were treated with 100 nM

dexamathasone in 0.1% ethanol for 48 h and collected for RNA

preparation. For myotube size quantification, the transfected L6

myotubes were fixed after 48 h of dexamatheasone treatment. Myotube

cultures were photographed under a phase contrast microscope (Leica

Microsystems). The diameters were measured in a total of 60

myotubes from at least 6 random fields using Image-Pro Plus

software (Media Cybernetics, Silver Springs, MD, USA).

Quantitative reverse-transcription PCR

(qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from the L6 myotubes, and

reverse transcription was performed using Oligo(dT) primers

(Shanghai Sangon Biotechnology Corp., Shanghai, China). cDNA was

synthesized using an iScript cDNA Synthesis kit (Bio-Rad) following

the manufacturer’s instructions, and stored at −20°C prior to use.

All primers were purchased from Generay Biotech Co., Ltd.

(Shanghai, China). The primers used in this study were as folows:

TRAF6 forward, GGCA TTTACATTTGGAAGATTGGC and reverse, AGGGAAATG

TAGTTTGCACAGCG; muscle ring-finger protein 1 (MuRF1) forward,

GGTGCCTACTTGCTCCTTGTGC and reverse, CTGTTTTCCTTGGTCACTCGGC; muscle

atrophy F-box (MAFbx) forward, GATCTTGTCTGACAAAGGGCAGC and reverse,

GGGTGAAAGTGAGACGGAGCAG and GAPDH forward, CAACGGGAAACCCATCACCA and

reverse, ACG CCAGTAGACTCCACGACAT. The PCR reactions were performed

on the Applied Biosystems 7500 real-time PCR system using the iTaq

Fast SYBR-Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) following the manufacturer’s

instructions. The cycle threshold (Ct) values, corresponding to the

PCR cycle number at which fluorescence emission reached a threshold

above baseline emission, were determined. mRNA expression levels

were then calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method, as

described in a previous study (16). GAPDH served as an internal

control.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as the means ± SD. One-way

ANOVA was used to compare differences between groups. All

statistical analyses were conducted with the Stata 7.0 software

package (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). Values of

p<0.05 were considered to indicate statistically significant

differences.

Results

Screening of differentially expressed

proteins and functional analysis

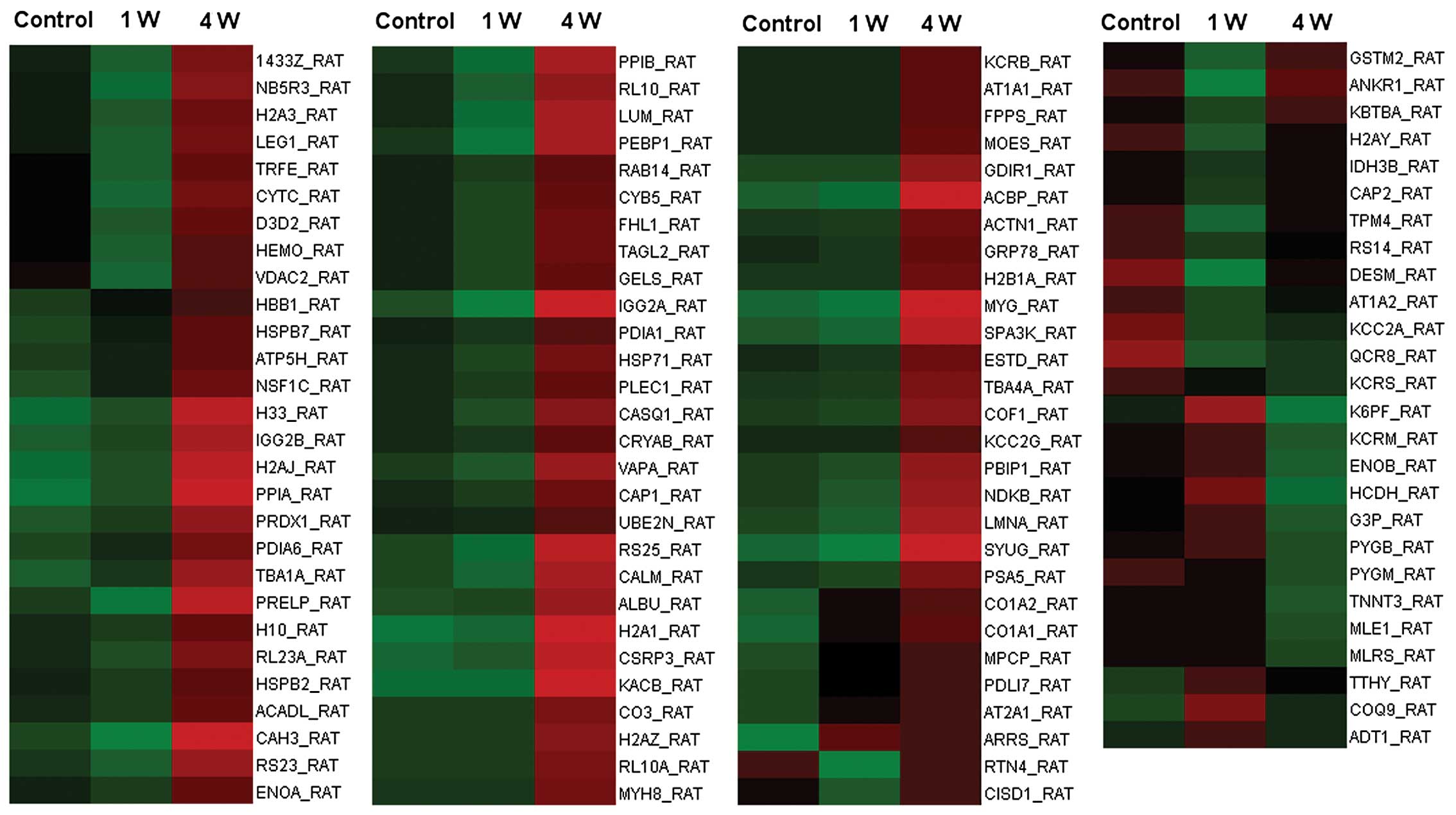

iTRAQ-based proteomic analysis

A total of 110 proteins were identified as

differentially expressed (with criteria: p<0.05 and fold change

of >2.0) in denervated TA muscle at 1 and 4 weeks following

sciatic nerve transection. The 110 proteins are listed in Table I, and their expression levels

relative to the control are displayed in a heatmap graphic

(Fig. 1).

| Table IList of differentially expressed

proteins in denervated tibialis anterior (TA) muscle. |

Table I

List of differentially expressed

proteins in denervated tibialis anterior (TA) muscle.

| Functional

category: gene name | 115/114 | 116/114 | Predicted molecular

function/protein name |

|---|

| Metabolic

enzymes |

| ACADL_RAT | 0.756 | 2.180 | Long-chain specific

acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, mitochondrial |

| CAH3_RAT | 0.300 | 4.451 | Carbonic anhydrase

3 |

| CYB5_RAT | 0.692 | 2.077 | Cytochrome b5 |

| D3D2_RAT | 0.444 | 1.778 | 3,2-Trans-enoyl-CoA

isomerase, mitochondrial |

| ENOA_RAT | 0.725 | 2.102 | Alpha-enolase |

| ENOB_RAT | 1.236 | 0.302 | Beta-enolase |

| ESTD_RAT | 0.923 | 2.538 | S-formylglutathione

hydrolase |

| FPPS_RAT | 1.028 | 2.355 | Farnesyl

pyrophosphate synthetase |

| G3P_RAT | 1.445 | 0.429 |

Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate

dehydrogenase |

| GSTM2_RAT | 0.316 | 1.158 | Glutathione

S-transferase Mu 2 |

| HADH_RAT | 1.820 | 0.261 |

Hydroxyacyl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase,

mitochondrial |

| K6PF_RAT | 2.512 | 0.288 |

6-Phosphofructokinase, muscle type |

| KCC2A_RAT | 0.300 | 0.425 |

Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein

kinase type II alpha chain |

| KCC2G_RAT | 0.923 | 2.000 |

Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein

kinase type II gamma chain |

| KCRB_RAT | 1.000 | 2.286 | Creatine kinase

B-type |

| KCRM_RAT | 1.271 | 0.373 | Creatine kinase

M-type |

| KCRS_RAT | 0.600 | 0.425 | Creatine kinase,

sarcomeric mitochondrial |

| NDKB_RAT | 0.778 | 3.444 | Nucleoside

diphosphate kinase B |

| PDIA1_RAT | 0.824 | 2.015 | Protein

disulfide-isomerase |

| PDIA6_RAT | 1.400 | 3.400 | Protein

disulfide-isomerase A6 |

| PPIA_RAT | 2.000 | 10.000 | Peptidyl-prolyl

cis-trans isomerase A |

| PPIB_RAT | 0.400 | 3.300 | Peptidyl-prolyl

cis-trans isomerase B |

| PRDX1_RAT | 1.375 | 4.375 |

Peroxiredoxin-1 |

| PYGB_RAT | 1.355 | 0.425 | Glycogen

phosphorylase, brain form (fragment) |

| PYGM_RAT | 0.895 | 0.354 | Glycogen

phosphorylase, muscle form |

| ATP5H_RAT | 1.412 | 2.753 | ATP synthase

subunit d, mitochondrial |

| IDH3B_RAT | 0.488 | 0.847 | Isocitrate

dehydrogenase (NAD+) subunit beta, mitochondrial |

| NB5R3_RAT | 0.337 | 2.228 | NADH-cytochrome b5

reductase 3 |

| Structural

proteins |

| ACTN1_RAT | 0.904 | 2.604 |

Alpha-actinin-1 |

| CAP1_RAT | 0.800 | 2.467 | Adenylyl

cyclase-associated protein 1 |

| CAP2_RAT | 0.462 | 0.846 | Adenylyl

cyclase-associated protein 2 |

| COF1_RAT | 0.909 | 3.182 | Cofilin-1 |

| CSRP3_RAT | 1.312 | 6.750 | Cysteine and

glycine-rich protein 3 |

| DESM_RAT | 0.055 | 0.575 | Desmin |

| FHL1_RAT | 0.667 | 2.200 | Four and a half LIM

domains protein 1 |

| LMNA_RAT | 0.750 | 3.875 | Lamin-A |

| MLE1_RAT | 1.047 | 0.394 | Myosin light chain

1, skeletal muscle isoform |

| MLRS_RAT | 1.038 | 0.421 | Myosin regulatory

light chain 2, skeletal muscle isoform |

| MOES_RAT | 1.019 | 2.443 | Moesin |

| MYH8_RAT | 1.000 | 2.780 | Myosin-8

(fragment) |

| PDLI7_RAT | 1.917 | 2.750 | PDZ and LIM domain

protein 7 |

| PLEC1_RAT | 0.786 | 2.214 | Plectin-1 |

| TAGL2_RAT | 0.658 | 2.225 | Transgelin-2 |

| TBA1A_RAT | 1.625 | 5.125 | Tubulin alpha-1A

chain |

| TBA4A_RAT | 0.917 | 2.917 | Tubulin alpha-4A

chain |

| TNNT3_RAT | 1.019 | 0.360 | Troponin T, fast

skeletal muscle |

| TPM4_RAT | 0.222 | 0.815 | Tropomyosin alpha-4

chain |

| Signaling

molecules |

| ADT1_RAT | 2.070 | 1.038 | ADP/ATP translocase

1 |

| ARRS_RAT | 87.902 | 74.473 | S-arrestin |

| AT1A1_RAT | 1.000 | 2.231 |

Sodium/potassium-transporting ATPase

subunit alpha-1 |

| AT1A2_RAT | 0.367 | 0.600 |

Sodium/potassium-transporting ATPase

subunit alpha-2 |

| AT2A1_RAT | 2.300 | 2.502 |

Sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum calcium

ATPase 1 |

| CALM_RAT | 0.586 | 3.810 | Calmodulin |

| CASQ1_RAT | 0.701 | 2.731 | Calsequestrin-1

(fragment) |

| GDIR1_RAT | 1.046 | 3.650 | Rho

GDP-dissociation inhibitor 1 |

| GELS_RAT | 0.665 | 2.081 | Gelsolin |

| LEG1_RAT | 0.452 | 2.123 | Galectin-1 |

| MPCP_RAT | 2.291 | 3.311 | Phosphate carrier

protein, mitochondrial |

| PEBP1_RAT | 0.333 | 3.333 |

Phosphatidylethanolamine-binding protein

1 |

| RAB14_RAT | 0.706 | 2.000 | Ras-related protein

Rab-14 |

| SPA3K_RAT | 0.800 | 5.400 | Serine protease

inhibitor A3K |

| SYUG_RAT | 0.143 | 8.857 |

Gamma-synuclein |

| VDAC2_RAT | 0.313 | 1.438 | Voltage-dependent

anion-selective channel protein 2 |

| Chaperones |

| 1433Z_RAT | 0.501 | 2.291 | 14-3-3 protein

zeta/delta |

| CRYAB_RAT | 0.860 | 2.156 | Alpha-crystallin B

chain |

| GRP78_RAT | 0.951 | 2.354 | 78 kDa

glucose-regulated protein |

| HSP71_RAT | 0.750 | 2.431 | Heat shock 70 kDa

protein 1A/1B |

| HSPB2_RAT | 0.769 | 2.077 | Heat shock protein

beta-2 |

| HSPB7_RAT | 1.498 | 2.902 | Heat shock protein

beta-7 (fragment) |

| Extracellular

matrix proteins |

| CO1A1_RAT | 3.754 | 5.350 | Collagen alpha-1

(I) chain |

| CO1A2_RAT | 2.884 | 4.169 | Collagen alpha-2

(I) chain |

| LUM_RAT | 0.375 | 3.125 | Lumican |

| PRELP_RAT | 0.333 | 3.833 | Prolargin |

| Ubiquitin

proteasome pathway |

| PSA5_RAT | 0.818 | 2.727 | Proteasome subunit

alpha type-5 |

| UBE2N_RAT | 0.867 | 2.000 |

Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2 N |

| Carrier

proteins |

| ACBP_RAT | 0.667 | 6.167 | Acyl-CoA-binding

protein |

| ALBU_RAT | 1.148 | 4.169 | Serum albumin |

| HBB1_RAT | 1.521 | 2.413 | Hemoglobin subunit

beta-1 |

| HEMO_RAT | 0.38 | 1.500 | Hemopexin |

| MYG_RAT | 0.667 | 7.529 | Myoglobin |

| TRFE_RAT | 0.385 | 1.769 |

Serotransferrin |

| Ribosomal proteins

and histones |

| H10_RAT | 0.738 | 2.150 | Histone H1.0 |

| H2A1_RAT | 1.500 | 11.500 | Histone H2A type

1 |

| H2A3_RAT | 0.492 | 2.014 | Histone H2A type

3 |

| H2AJ_RAT | 1.750 | 7.750 | Histone H2A.J |

| H2AY_RAT | 0.286 | 0.750 | Core histone

macro-H2A.1 |

| H2AZ_RAT | 1.000 | 3.273 | Histone H2A.Z |

| H2B1A_RAT | 0.946 | 2.630 | Histone H2B type

1-A |

| H33_RAT | 1.600 | 7.600 | Histone H3.3 |

| RL10_RAT | 0.533 | 2.800 | 60S ribosomal

protein L10 |

| RL10A_RAT | 1.000 | 3.100 | 60S ribosomal

protein L10a |

| RL23A_RAT | 0.667 | 2.467 | 60S ribosomal

protein L23a |

| RS14_RAT | 0.424 | 0.727 | 40S ribosomal

protein S14 |

| RS23_RAT | 0.571 | 3.143 | 40S ribosomal

protein S23 |

| RS25_RAT | 0.500 | 4.200 | 40S ribosomal

protein S25 |

| Membrane

trafficking proteins |

| NSF1C_RAT | 1.600 | 3.500 | NSFL1 cofactor

p47 |

| RTN4_RAT | 0.104 | 0.991 | Reticulon-4 |

| TTHY_RAT | 2.377 | 1.600 | Transthyretin |

| VAPA_RAT | 0.700 | 3.200 | Vesicle-associated

membrane protein-associated protein A |

| Protein

synthesis |

| KBTBA_RAT | 0.474 | 1.159 | Kelch repeat and

BTB domain-containing protein 10 |

| Other proteins |

| ANKR1_RAT | 0.047 | 1.213 | Ankyrin repeat

domain-containing protein 1 |

| CISD1_RAT | 0.364 | 1.045 | CDGSH iron sulfur

domain-containing protein 1 |

| CO3_RAT | 1.015 | 3.195 | Complement C3 |

| COQ9_RAT | 3.467 | 1.294 | Ubiquinone

biosynthesis protein COQ9, mitochondrial |

| CYTC_RAT | 0.319 | 1.837 | Cystatin-C |

| IGG2A_RAT | 0.240 | 5.230 | Ig gamma-2A chain C

region |

| IGG2B_RAT | 1.420 | 5.569 | Ig gamma-2B chain C

region |

| KACB_RAT | 1.009 | 9.908 | Ig kappa chain C

region, B allele |

| PBIP1_RAT | 0.818 | 3.273 | Pre-B-cell leukemia

transcription factor-interacting protein 1 |

| QCR8_RAT | 0.235 | 0.333 | Cytochrome b-c1

complex subunit 8 |

GO functional annotation

The 110 differentially expressed proteins were

grouped into 11 classes according to their molecular function based

on GO terms (Table I). The

highest number of proteins was classified as metabolic enzymes,

followed by structural proteins, signaling molecules, chaperones,

extracellular matrix proteins and ubiquitin proteasome

pathway-related proteins.

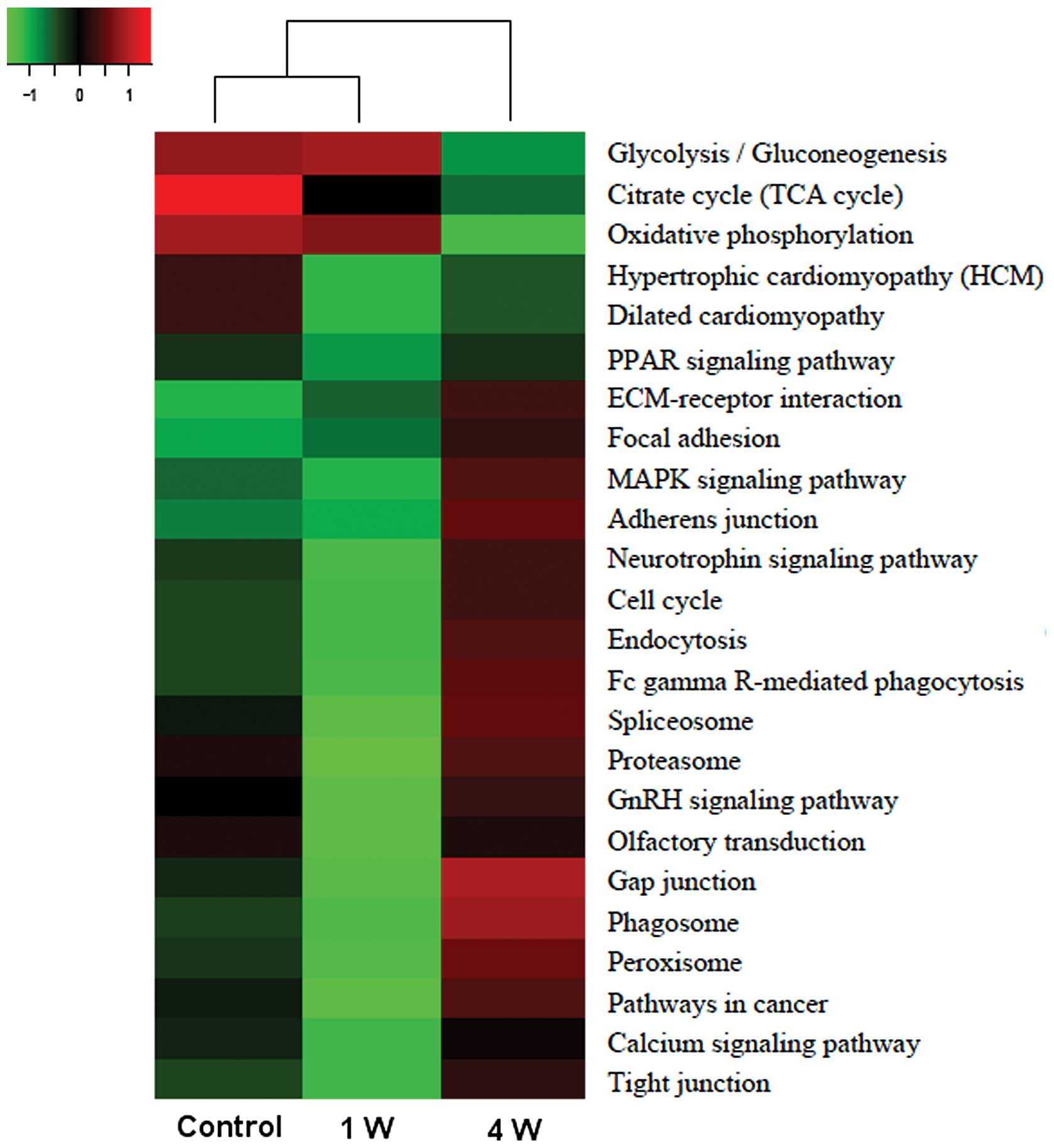

KEGG pathway identification

The 110 differentially expressed proteins were

involved in a number of distinct pathways, such as glycolysis,

Krebs (tricarboxylic acid/citrate) cycle, proteasome and MAPK

signaling. The heatmap displaying the expression data for the

corresponding genes (Fig. 2)

shows that during denervation-induced muscle atrophy, decreasing

trends are observed for the Krebs cycle and glycolysis (at 4

weeks), while proteasome and MAPK signaling pathway genes showed an

increasing trend at 4 weeks. Moreover, glycolysis-related genes

were the most highly expressed in all conditions.

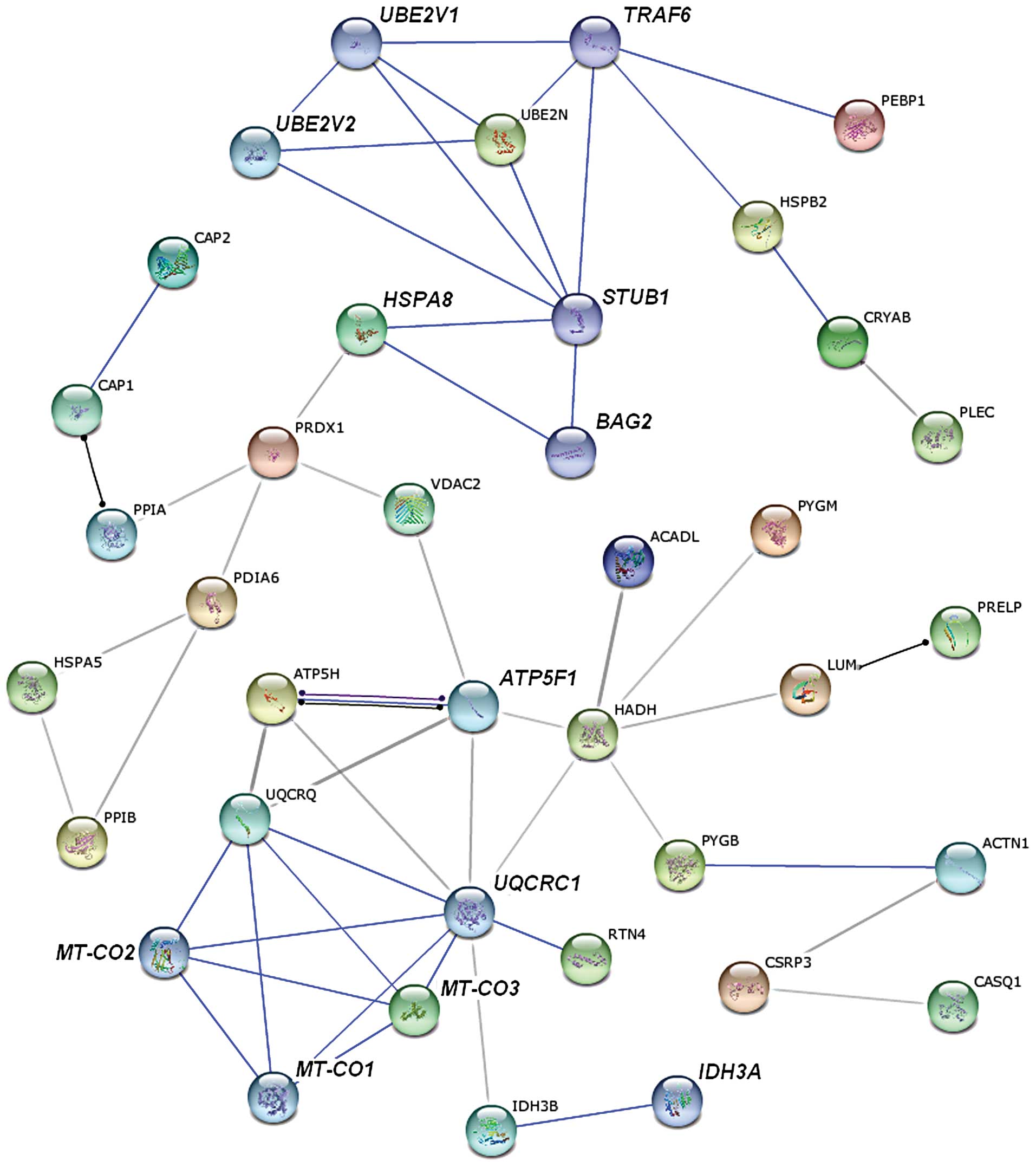

Analysis with STRING databases

We searched for known and predicted interactions for

the differentially expressed proteins identified by iTRAQ-based

proteomics in the STRING protein-protein interaction database and

constructed a protein-protein interaction network (Fig. 3). The network predicted an

interaction between ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2N (UBE2N),

identified as upregulated in denervated atrophic skeletal muscle

from our proteomics analysis, and TRAF6, which was not detected in

our study. UBE2N is required for TRAF6 activation (17). Therefore, we hypothesized that

TRAF6 may also be expressed in denervated TA muscle and upregulated

during denervation-induced atrophy. Furthermore, it was shown that

TRAF6 activates both MuRF1 and muscle-specific ubiquitin E3-ligase

atrophy gene-1/muscle atrophy F-box (Atrogin-1/MAFbx) (18), which further suggests that the

expression of MuRF1 and Atrogin-1/MAFbx is upregulated during the

progression of muscle atrophy. Both hypotheses derived from the

network analysis were confirmed by western blot analysis (see

below).

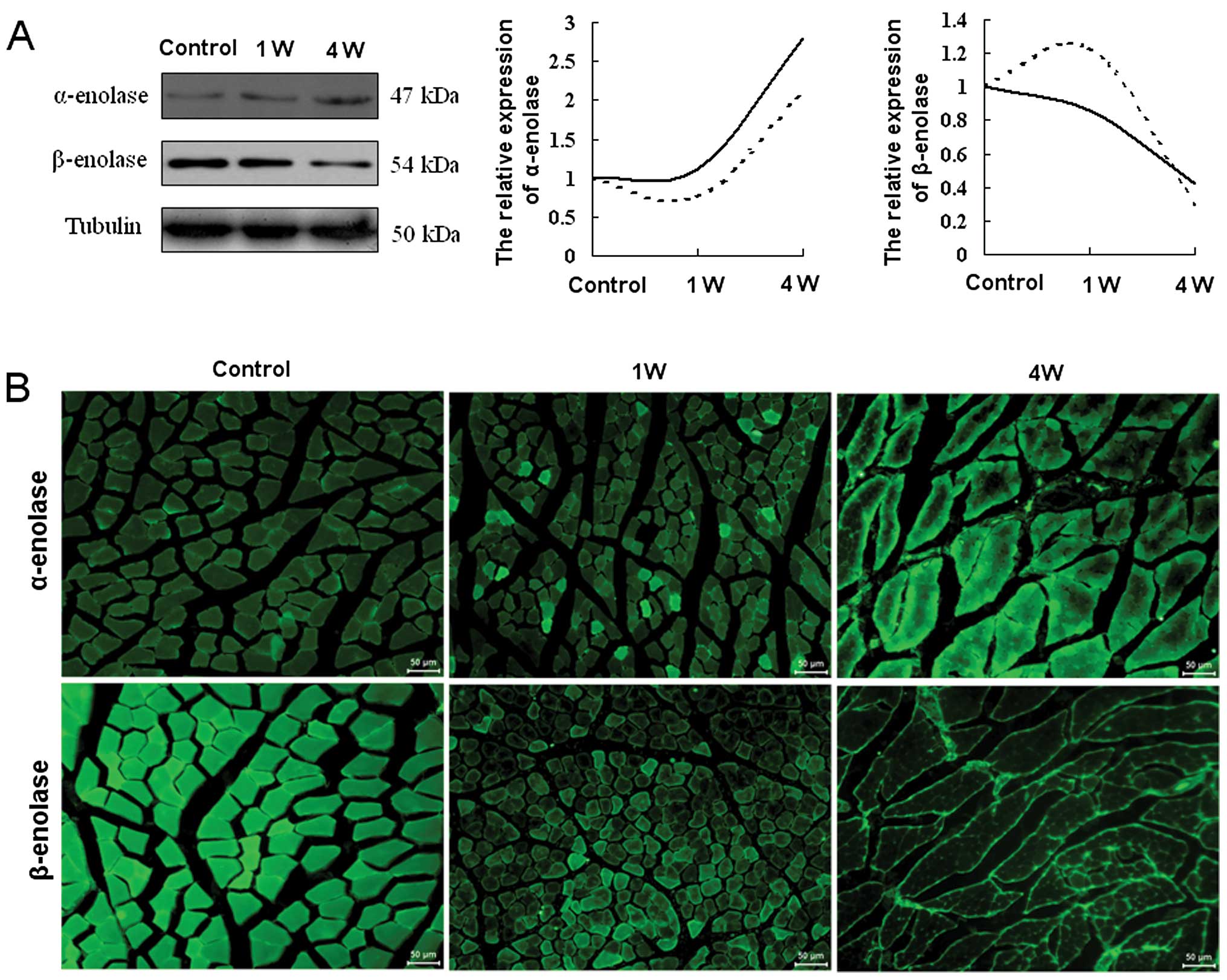

Validation of selected differentially

expressed proteins

To validate the results obtained by iTRAQ coupled

with 2DLC-MS/MS, 2 representative glycolytic enzymes, α- and

β-enolase, were selected for western blot and immunohistochemical

analyses. In these analyses, α- and β-enolase were found to be

gradually up- and downregulated during denervation-induced atrophy

in TA muscle, respectively (Fig. 4A

and B). The comparison between the western blot analysis and

iTRAQ-based proteomics results for the 2 enzymes indicated that the

expression change trends were consistent overall between the 2

methods, despite some deviations (Fig. 4A).

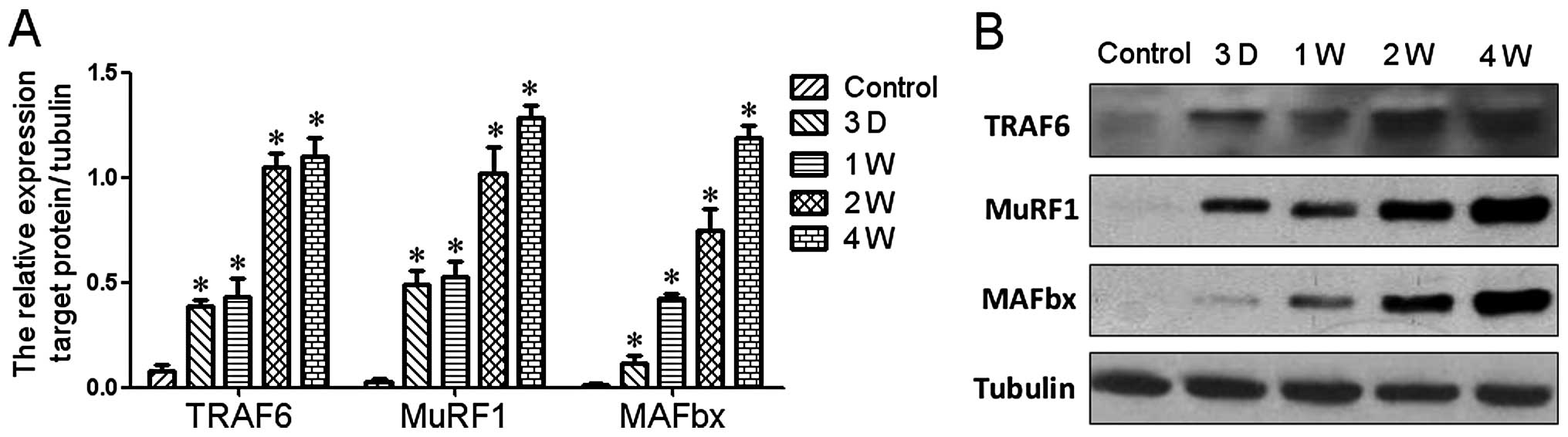

Western blot analysis was also carried out to

confirm the hypothesis derived from the protein-protein interaction

network. The results indicated that the protein expression of

TRAF6, MAFBx and MuRF1 was significantly upregulated during

denervation-induced muscle atrophy in TA muscle (Fig. 5).

Involvement of TRAF6 in myotube

atrophy

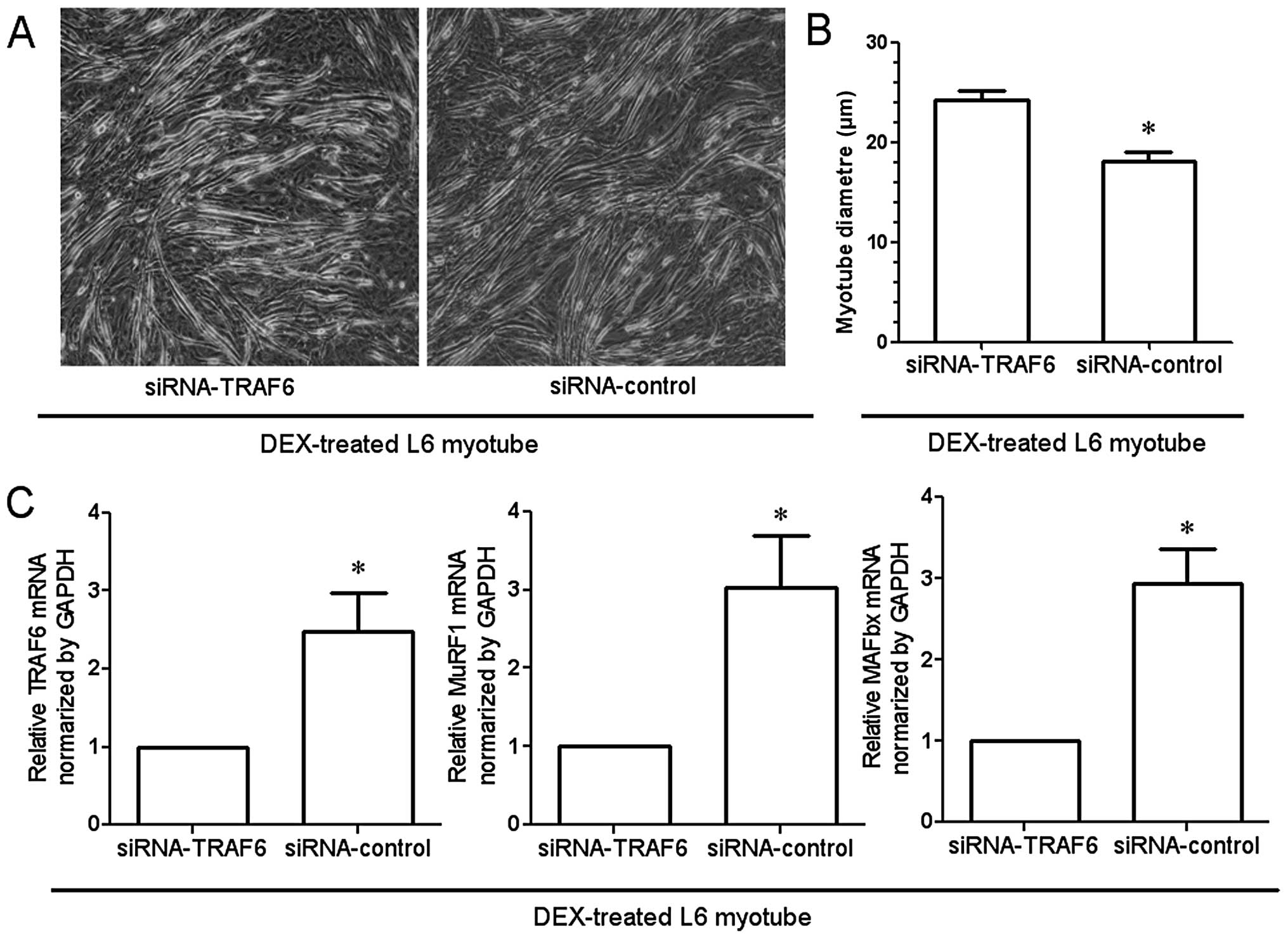

Light microscopy revealed that transfection of

myotubes with the siRNA targeting TRAF6 attenuated

dexamethasone-induced atrophy of L6 myotubes as compared to

transfection with the negative control siRNA (Fig. 6A). The diameter of L6 myotubes in

which TRAF6 was knocked down was significantly larger than that of

the myotubes transfected with the negative control (Fig. 6B). In addition, qRT-PCR

demonstrated the dexamethasone-induced upregulation of MAFBx and

MuRF1, as well as the expected downregulation of TRAF6 expression

by transfection with siRNA (Fig.

6C).

Discussion

In this study, proteomic and bioinformatic analyses

were performed to examined the changes in TA muscle during

denervation-induced atrophy. Our findings are in agreement with

results from previous global protein expression profiling studies

in denervated skeletal muscle (12,19), but also identified novel protein

targets that may be relevant to the pathobiology of muscle

atrophy.

The majority of differentially expressed proteins in

denervated TA muscle identified in our study are enzymes involved

in the regulation of energy metabolism, including α- and β-enolase,

glycogen phosphorylase muscle form (PYGM), creatine kinase M-type

(KCRM) and GAPDH (G3P). Cross-referencing with KEGG pathway data

indicated that these energy metabolism-related enzymes are involved

in the glycolytic, Krebs cycle and oxidative phosphorylation

pathways. These observations suggest that time-dependent changes in

energy production might be a dominant molecular event occurring in

denervated skeletal muscle. The altered expression of energy

metabolism-related proteins can lead to an overall disturbance of

the muscle, and ultimately contribute to the establishment of

pathological states, such as atrophy (20–22).

Enolase (2-phospho-D-glycerate hydrolase) is an

essential dimeric glycolytic enzyme, and skeletal muscles contain 2

isoforms, α and β (15,23). A previous study demonstrated that

the ubiquitous α-enolase and the muscle-specific β-enolase have the

highest and lowest expression in undifferentiated myoblasts,

respectively, and that a significant increase in the expression of

β-enolase occurs upon differentiation of myoblasts and is

maintained until the postnatal period (24). By contrast, α-enolase has been

rarely found expressed in the adult skeletal muscle. An isozymic

switch from the embryonic α- towards the muscle-specific β-enolase

has been observed during differentiation and maturation of

myoblasts with high-energy requirements (24,25). In our study, the expression of α-

and β-enolase following muscle denervation in adult TA muscle was

increased and decreased, respectively. This result suggests that an

isozymic switch opposite to that occurring in muscle maturation

(from the muscle-specific β- towards the embryonic α-enolase) takes

place during denervation-induced muscle atrophy.

Enolase is a glycolytic enzyme that catalyses the

conversion of 2-phosphoglycerate (2-PGA) to phosphoenolpyruvate

(PEP) (24). β-Enolase binds with

high affinity to sarcomeric troponin at the subcellular site where

glycolysis-produced ATP is most needed for muscle contraction

(26). In human muscles, the

β-enolase subunit accounts for >90% of the total enolase

activity (27), and high levels

of β-enolase characterize the glycolytic fast-twitch fibers of

adult muscles. During the degeneration of myofibers, the drop in

total enolase activity, mainly caused by a rapid decrease of

β-enolase, correlates with myofiber degeneration (25). In this study, β-enolase was

significantly downregulated in denervated TA muscle, which might

relate to the reduced production of ATP in glycolysis, the failure

in maintenance of the fast-twitch skeletal muscle phenotype, and

the myofiber degeneration observed in atrophy. These hypotheses

remain to be further investigated.

Enolase is well known as an enzyme of the glycolytic

pathway, ubiquitously expressed in the cytosol of prokaryotic and

eukaryotic cells (28). α-enolase

is however a multifunctional protein; in addition to its glycolytic

activity, this protein has plasminogen receptor functions and plays

a regulatory role in extracellular remodelling processes such as

myogenesis (29,30). In this study, α-enolase was

significantly upregulated in denervated TA muscle, which might be

associated with early stages of myogenesis following nerve

transection. Furthermore, α-enolase was reported to be upregulated

by hypoxia (31) and

pro-inflammatory stimuli (32),

which are two common pathogenic characteristics of muscle atrophy

(33–36). Based on these reports, we

hypothesize that the significant upregulation of α-enolase might

relate to the inflammatory environment of the denervated skeletal

muscle. Pro-inflammatory cytokines play a key role in the

pathophysiology of muscle atrophy through activation of

atrophy-related genes, such as nucleasr factor (NF)-κB, TRAF6,

MuRF1 and MAFbx (37–39). Therefore, it appears that

α-enolase plays a complex role in the regulation of

denervation-induced muscle atrophy. The exact underlying mechanisms

will be evaluated in a future study.

In proteomic studies, low-abundance proteins are

commonly undetected. In this study, proteomic analysis indicated

that the E2 polyubiquitin-conjugating enzyme UBE2N, required for

TRAF6 activation (17), is

upregulated in denervated TA muscle. This result, combined with

predictions of protein-protein interactions based on the STRING

database, allowed us to infer that TRAF6 might be upregulated in

denervated TA muscle, although the expression of this protein was

not directly assessed by iTRAQ-based proteomics (undetected

protein). This hypothesis was confirmed by western blotting. Our

finding on TRAF6 expression in denervation-induced muscle atrophy

is consistent with a previous study of starvation-induced muscle

atrophy (18).

TRAF6 is a unique E3 ubiquitin ligase and adaptor

protein involved in receptor-mediated activation of a number of

signaling pathways, and its expression is enhanced during skeletal

muscle atrophy (40). Deletion of

the TRAF6 reduced the expression of the muscle-specific ubiquitin

ligases MuRF1 and MAFBx (18),

which are critical proteins in the development of muscle atrophy

(41,42). We further inferred that MAFBx and

MuRF1 may be upregulated in denervated TA muscle. The inference was

also confirmed by western blot analysis.

We hypothesized that the increased expression of

α-enolase in denervated TA muscle may relate to the activation of

atrophy-related genes, including TRAF6, MuRF1 and MAFBx. Although

these proteins were not identified by our proteomics analysis

(possibly due to their low abundance), predicted interaction data

from the STRING database allowed to infer a potential expression of

the protein TRAF6 in denervated TA muscle. The expression of TRAF6,

but also, MuRF1 and MAFBx proteins, was positively detected in

denervated TA muscle with western blot analysis.

In order to investigate the potential involvement

and the functional role of TRAF6 in the development of myotube

atrophy, in this study, we examined the effects of siRNA-mediated

TRAF6 knockdown on dexamethasone-induced L6 myotube atrophy. In

addition, the mRNA levels of TRAF6, MuRF1 and MAFBx were quantified

by qRT-PCR in atrophied myotubes with the TRAF6 knockdown, and the

results confirmed that TRAF6 may possibly exert its function

through at least in part, regulating the muscle-specific ubiquitin

ligases MAFBx and MuRF1.

In summary, the combined use of proteomics and

bioinformatics provided additional knowledge on denervation-induced

skeletal muscle atrophy. Hopefully, our findings may contribute to

the understanding and treatment of skeletal muscle atrophy. This

study also provided an example where a high number of proteins with

high- or medium-abundance were identified with high confidence by

an advanced proteomics technique, although even higher-sensitivity

methods still remain to be developed so as to allow detection of

low-abundance proteins. We suggest that subcellular fractionation

techniques may be used in the future to reduce the sampling

complexity and enrich for proteins of interest in skeletal muscle

extracts, thereby allowing more a thorough analysis of the

proteomic content of atrophied muscle.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the Hi-Tech Research and

Development Program of China (863 Program, grant no. 2012AA020502),

the National Key Basic Research Program of China (973 Program,

grant nos. 2014CB542202 and 2014CB542203), the National Natural

Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 81130080, 81171180,

81301628 and 81073079), a project funded by the Priority Academic

Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions

(PAPD), the Basic Research Project of the Jiangsu Education

Department (grant no. 12KJB310010), the Colleges and Universities

in Jiangsu Province graduate research project (grant no.

CXZZ12_0861) and the Nantong Science and Technology Innovation

Program (grant no. BK2011045). We thank Professor Jie Liu for

assistance in the manuscript preparation.

References

|

1

|

Jackman RW and Kandarian SC: Am J Physiol

Cell Physiol. 287:C834–843. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Ibebunjo C, Chick JM, Kendall T, et al:

Genomic and proteomic profiling reveals reduced mitochondrial

function and disruption of the neuromuscular junction driving rat

sarcopenia. Mol Cell Biol. 33:194–212. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

McKinnell IW and Rudnicki MA: Molecular

mechanisms of muscle atrophy. Cell. 119:907–910. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Romanick M, Thompson LV and Brown-Borg HM:

Murine models of atrophy, cachexia, and sarcopenia in skeletal

muscle. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1832:1410–1420. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Wei B, Dui W, Liu D, et al: MST1, a key

player, in enhancing fast skeletal muscle atrophy. BMC Biology.

11:122013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Nagpal P, Plant PJ, Correa J, et al: The

ubiquitin ligase Nedd4-1 participates in denervation-induced

skeletal muscle atrophy in mice. PloS One. 7:e464272012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Nader GA: Molecular determinants of

skeletal muscle mass: getting the ‘AKT’ together. Int J Biochem

Cell Biol. 37:1985–1996. 2005.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Ramamoorthy S, Donohue M and Buck M:

Decreased Jun-D and myogenin expression in muscle wasting of human

cachexia. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 297:E392–401. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Menconi MJ, Arany ZP, Alamdari N, et al:

Sepsis and glucocorticoids downregulate the expression of the

nuclear cofactor PGC-1beta in skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol

Endocrinol Metab. 299:E533–543. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Tews DS, Behrhof W and Schindler S:

Expression patterns of initiator and effector caspases in

denervated human skeletal muscle. Muscle Nerve. 31:175–181. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Bantscheff M, Boesche M, Eberhard D, et

al: Robust and sensitive iTRAQ quantification on an LTQ Orbitrap

mass spectrometer. Mol Cell Proteomics. 7:1702–1713. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Sun H, Li M, Gong L, et al: iTRAQ-coupled

2D LC-MS/MS analysis on differentially expressed proteins in

denervated tibialis anterior muscle of Rattus norvegicus.

Mol Cell Biochem. 364:193–207. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Sinclair J, Metodieva G, Dafou D, et al:

Profiling signatures of ovarian cancer tumour suppression using

2D-DIGE and 2D-LC-MS/MS with tandem mass tagging. J Proteomics.

74:451–465. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Szklarczyk D, Franceschini A, Kuhn M, et

al: The STRING database in 2011: functional interaction networks of

proteins, globally integrated and scored. Nucleic Acids Res.

39:D561–D568. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Sun H, Zhu T, Ding F, et al: Proteomic

studies of rat tibialis anterior muscle during postnatal growth and

development. Mol Cell Biochem. 332:161–171. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Menconi M, Gonnella P, Petkova V, et al:

Dexamethasone and corticosterone induce similar, but not identical,

muscle wasting responses in cultured L6 and C2C12 myotubes. J Cell

Biochem. 105:353–364. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Sanada T, Kim M, Mimuro H, et al: The

Shigella flexneri effector OspI deamidates UBC13 to dampen

the inflammatory response. Nature. 483:623–626. 2012.

|

|

18

|

Paul PK, Bhatnagar S, Mishra V, et al: The

E3 ubiquitin ligase TRAF6 intercedes in starvation-induced skeletal

muscle atrophy through multiple mechanisms. Mol Cell Biol.

32:1248–1259. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Jones A, Hwang DJ, Narayanan R, et al:

Effects of a novel selective androgen receptor modulator on

dexamethasone-induced and hypogonadism-induced muscle atrophy.

Endocrinology. 151:3706–3719. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Wang X, Pickrell AM, Rossi SG, et al:

Transient systemic mtDNA damage leads to muscle wasting by reducing

the satellite cells pool. Hum Mol Genet. 22:3976–3986. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Calvani R, Joseph AM, Adhihetty PJ, et al:

Mitochondrial pathways in sarcopenia of aging and disuse muscle

atrophy. Biol Chem. 394:393–414. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Picard M, Ritchie D, Thomas MM, et al:

Alterations in intrinsic mitochondrial function with aging are

fiber type-specific and do not explain differential atrophy between

muscles. Aging Cell. 10:1047–1055. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Sun H, Liu J, Ding F, et al: Investigation

of differentially expressed proteins in rat gastrocnemius muscle

during denervation-reinnervation. J Muscle Res Cell Motil.

27:241–250. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Keller A, Peltzer J, Carpentier G, et al:

Interactions of enolase isoforms with tubulin and microtubules

during myogenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1770:919–926. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Merkulova T, Dehaupas M, Nevers MC, et al:

Differential modulation of alpha, beta and gamma enolase isoforms

in regenerating mouse skeletal muscle. Eur J Biochem.

267:3735–3743. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Merkulova T, Lucas M, Jabet C, et al:

Biochemical characterization of the mouse muscle-specific enolase:

developmental changes in electrophoretic variants and selective

binding to other proteins. Biochem J. 323(Pt 3): 791–800. 1997.

|

|

27

|

Comi GP, Fortunato F, Lucchiari S, et al:

Beta-enolase deficiency, a new metabolic myopathy of distal

glycolysis. Ann Neurol. 50:202–207. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Seweryn E, Pietkiewicz J, Szamborska A, et

al: Enolase on the surface of prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells is a

receptor for human plasminogen. Postepy Hig Med Dosw (Online).

61:672–682. 2007.(In Polish).

|

|

29

|

Díaz-Ramos A, Roig-Borrellas A,

García-Melero A, et al: Requirement of plasminogen binding to its

cell-surface receptor alpha-enolase for efficient regeneration of

normal and dystrophic skeletal muscle. PloS One.

7:e504772012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Díaz-Ramos A, Roig-Borrellas A,

García-Melero A, et al: alpha-Enolase, a multifunctional protein:

its role on pathophysiological situations. J Biomed Biotechnology.

2012:1567952012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Aaronson RM, Graven KK, Tucci M, et al:

Non-neuronal enolase is an endothelial hypoxic stress protein. J

Biol Chem. 270:27752–27757. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Fontán PA, Pancholi V, Nociari MM, et al:

Antibodies to streptococcal surface enolase react with human

α-enolase: implications in poststreptococcal sequelae. J Infect

Dis. 182:1712–1721. 2000.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Paul PK, Gupta SK, Bhatnagar S, et al:

Targeted ablation of TRAF6 inhibits skeletal muscle wasting in

mice. J Cell Biol. 191:1395–1411. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Zhao W, Pan J, Zhao Z, et al: Testosterone

protects against dexamethasone-induced muscle atrophy, protein

degradation and MAFbx upregulation. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol.

110:125–129. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Castillero E, Alamdari N, Lecker SH, et

al: Suppression of atrogin-1 and MuRF1 prevents

dexamethasone-induced atrophy of cultured myotubes. Metabolism.

62:1495–1502. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Castillero E, Alamdari N, Aversa Z, et al:

PPARβ/δ regulates glucocorticoid- and sepsis-induced FOXO1

activation and muscle wasting. PloS One. 8:e597262013.

|

|

37

|

Suetta C, Frandsen U, Jensen L, et al:

Aging affects the transcriptional regulation of human skeletal

muscle disuse atrophy. PloS One. 7:e512382012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Caron AZ, Haroun S, Leblanc E, et al: The

proteasome inhibitor MG132 reduces immobilization-induced skeletal

muscle atrophy in mice. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 12:1852011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Caron AZ, Drouin G, Desrosiers J, et al: A

novel hindlimb immobilization procedure for studying skeletal

muscle atrophy and recovery in mouse. J Appl Physiol.

106:2049–2059. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Paul PK and Kumar A: TRAF6 coordinates the

activation of autophagy and ubiquitin-proteasome systems in

atrophying skeletal muscle. Autophagy. 7:555–556. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Cao PR, Kim HJ and Lecker SH:

Ubiquitin-protein ligases in muscle wasting. Int J Biochem Cell

Biol. 37:2088–2097. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Zhang L, Tang H, Kou Y, et al:

MG132-mediated inhibition of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway

ameliorates cancer cachexia. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol.

139:1105–1115. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|