Introduction

Cervical cancer is the fourth most common

gynecological malignant tumor that affects females, and results in

~57,000 new cases annually with 311,000 deaths worldwide (1,2).

In China, the incidence of cervical cancer has increased rapidly

over the past 20 years (3).

Surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy are currently the main

treatment methods for cervical cancer (4). Although advances in these therapies

have prolonged patient survival, the limitations of effective

regimens are the resistance of tumor cells and their severe side

effects (5). Thus, there is an

urgent need for new anticancer drugs with fewer side effects that

may improve survival rates.

Voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC) family

proteins in the mitochondrial outer membrane play an important role

in cell survival and death (6).

VDACs interact with members of the Bcl-2 family to participate in

the release of cytochrome c and the subsequent activation of

caspase-9 (7,8). Furthermore, VDACs are involved in

caspase-independent apoptosis (9). Among the three isomers (VDAC1, VDAC2

and VDAC3), VDAC1 shows the highest expression in mammalian

mitochondria and plays an important role in apoptosis (10,11). VDAC1 upregulation promotes

apoptosis in multiple cell lines (12,13). VDAC1 is also a target of various

pro-apoptotic compounds such as curcumin, arsenic trioxide and

cannabinoids (14-16).

A previous study showed that a VDAC1-based peptide

induces apoptosis by releasing bound hexokinase 2 (HK2) from the

mitochondria (17). HK2 is a

crucial enzyme in the glycolytic pathway and antagonizes apoptosis

through its direct interaction with VDAC1 (18). HK2 is overexpressed in a variety

of tumor cell types, and HK2 is transported to the mitochondria and

interacts with VDAC1, which promotes the development of anaerobic

metabolism to compensate for the higher energy requirements in

tumor cells (19). Most tumor

cells still show active glucose uptake and glycolysis under aerobic

conditions, a phenomenon known as the Warburg effect, and metabolic

dysregulation affects tumor growth and cell death (20,21). Several compounds, such as

3-bromopyru-vate and methyl jasmonates, interact with HK2, causing

HK2 to separate from mitochondria and trigger apoptosis (22,23).

20(S)-Ginsenoside Rh2 [20(S)-GRh2], a

protopanaxadiol-type ginsenoside extracted from

Panaxginseng, is an active component with an anti-tumor

effect that inhibits tumor cell growth and induces tumor cell

apoptosis (24,25). Previous studies showed that

20(S)-GRh2 has safety advantages (such as reverse multidrug

resistance, balanced immunity and enhanced chemotherapy) (24) and shows no side effects,

indicating 20(S)-GRh2 may be a promising new antitumor drug

(26). Several reports

demonstrated that 20(S)-GRh2 stimulates apoptosis and induces

mitochondrial dysfunction by activating caspases, upregulating

various pro-apoptotic proteins such as Bax and downregulating

Bcl-XL (27-29). Therefore, 20(S)-GRh2 may stimulate

HeLa cell apoptosis by affecting the mitochondria and regulating

energy metabolism.

The present study tested this hypothesis and the

results showed that 20(S)-GRh2 exposure activated

mitochondrion-dependent apoptosis and suppressed mitochondrial

oxidative phosphorylation and glycolysis. To understand its

underlying mechanism, it was found that VDAC1 was significantly

upregulated in response to 20(S)-GRh2 treatment, while HK2 was

downregulated and separated from mitochondria. Bax transport from

the cytosol to the mitochondria was promoted by 20(S)-GRh2 and

knockdown of VDAC1 reduced 20(S)-GRh2-induced Bax translocation and

apoptosis. The results provided a more comprehensive understanding

of the mechanistic association between cancer mitochondrial

metabolism and tumor growth control by 20(S)-GRh2 and may

facilitate the development of new therapeutic methods for cervical

cancer.

Materials and methods

Materials and antibodies

20(S)-GRh2 (98% pure) was purchased from Shanghai

Yanye Biotechnology Co., Ltd. The following primary antibodies were

used in this study: Anti-HK2 rabbit polyclonal antibody (1:1,000;

cat. no. 22029-1-AP; ProteinTech Group, Inc.), anti-VDAC1 rabbit

monoclonal antibody (1:1,000; cat. no. AF1027; Beyotime Institute

of Biotechnology), anti-prohibitin rabbit monoclonal antibody

(1:1,000; cat. no. AF1126; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology),

anti-cytochrome c rabbit monoclonal antibody (1:1,000; cat.

no. AF2047; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology), anti-Bax rabbit

monoclonal antibody (1:1,000; cat. no. D2E11; Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc.), anti-Bcl-2 rabbit polyclonal antibody (1:1,000;

cat. no. abs131701, Absin) and anti-β-actin mouse monoclonal

antibody (1:1,000; cat. no. BS6007M; Bioworld Technology,

Inc.).

Cell culture and transfection

HeLa cells were obtained from the Cell Bank of the

Chinese Academy of Sciences and cultured in DMEM (HyClone; Cytiva)

with 10% FBS (HyClone; Cytiva), 100 µg/ml penicillin and 100

µg/ml streptomycin (HyClone; Cytiva) at 37°C in a humidified

atmosphere with 5% CO2. Cells were transfected with a

final concentration of 100 nM small interfering RNA (siRNA)

targeting VDAC1 using ribo-FECT CP reagent (Guangzhou Ribobio Co.,

Ltd.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Following

incubation for 24 h, HeLa cells were treated with 20(S)-GRh2 (35

and 45 µM) for 24 h at 37° before subsequent

experimentation. The target sequence in negative controls for RNA

interference is 5′-AAT TCT CCG AAC GTG TCA CGT-3′, and the target

sequences in VDAC1 for RNA interference were 5′-GGA GAC CGC TGT CAA

TCT T-3′ (siVC1-1) and 5′-GCT GCG ACA TGG ATT TCG A-3′

(siVC1-2).

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from HeLa cells treated with

20(S)-GRh2 using TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.). RNA purity was measured using a

BioSpec-nano spectrophotometer (Shimadzu Corporation), and total

RNA was reverse transcribed using a PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit with

gDNA Eraser (Takara Bio, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's

instructions. RT-qPCR was performed using a SYBR-Green assay

(Takara Bio, Inc.) on a CFX Connect Real-Time system (Bio-Rad

Laboratories, Inc.). Fold-changes in the expression of each gene

were calculated using the 2-ΔΔCq method (30). The following thermocycling

conditions were used for the qPCR: Initial denaturation at 95°C for

30 sec, followed by 40 cycles at 95°C for 5 sec and 60°C for 30

sec. GAPDH mRNA was used as an internal reference. The following

primer pairs were used for the qPCR: GAPDH forward, 5′-CTG GGC TAC

ACT GAG CAC C-3′ and reverse, 5′-AAG TGG TCG TTG AGG GCA ATG-3′

(Harbin Xinhai Genetic Testing Co., Ltd.); VDAC1 forward, 5′-CTG

ACC TTC GAT TCA TCC TTC TC-3′ and reverse, 5′-CTC CCG CTT GTA CCC

TGT C-3′ (Harbin Xinhai Genetic Testing Co., Ltd.) and HK2 forward,

5′-AGC CAC CAC TCA CCC TAC-3′ and reverse, 5′-CCA TTG TCC GTT ACT

TTC AC-3′ as well as forward, 5′-AGC CAC CAC TCA CCC TAC-3′ and

reverse, 5′-CCC ATT GTC CGT TAC TTT C-3′ (Comate Bioscience Co.,

Ltd.).

Cell viability assessment

The Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay (Wuhan Boster

Biological Technology Co., Ltd.) was used to assess cell viability

according to the manufacturer's instructions. HeLa cells were

treated with 20(S)-GRh2 at 37°C for 24 h at various concentrations

(35, 45, 55 and 65 µM) to determine the IC50

values. In addition, cells were treated with IC50

concentrations at 37°C at various timepoints (6, 12, 24, 36 and 48

h). Following treatment, 20 µl CCK-8 solution was added to

each well, and the plate was incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Absorption

at a wavelength of 450 nm was recorded using an Infinite M200 pro

reader (Tecan Group, Ltd.) and the cell viability was

calculated.

Cell apoptosis analysis

Cells were treated with various concentrations (35

and 45 µM) of 20(S)-GRh2 at 37°C for 24 h. Cells were then

suspended in 1X Binding Buffer and incubated with 5 µl

Annexin V-FITC and 5 µl PI (BD Biosciences) at room

temperature in the dark for 15 min. The cells were analyzed with a

Flow Sight flow cytometer (Amnis Corporation) and data were

analyzed using IDEAS software v6.1 (Amnis Corporation). Apoptotic

cells were also analyzed by Hoechst 33342 staining (Beyotime).

Briefly, following 20(S)-GRh2 (35 and 45 µM) treatment,

cells were incubated with Hoechst 33342 at 37°C in the dark for 30

min. Cells treated with 45 µM DMSO waere used as the control

group. Images were captured under an EVOS FL Auto fluorescence

microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at ×295

magnification.

Determination of the mitochondrial

membrane potential (MMP)

MMP alterations were measured using a JC-1 MMP Assay

kit (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.). HeLa

cells were treated with 20(S)-GRh2 (35 and 45 µM) at 37°C

for 24 h and then washed with cold PBS. A total of 10 µM

carbonyl cyanide 3-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP) was used to induce

a decrease in mitochondrial membrane potential for 20 min as a

positive control. JC-1 working solution was added to the cell

culture medium, and cells were incubated at 37°C in the dark for 20

min. Cells were imaged using an EVOS FL Auto fluorescence

microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at ×295

magnification.

MMP was also measured using the cationic dye

rhodamine 123 (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). Briefly, HeLa

cells were pre-treated with 20(S)-GRh2 (35 and 45 µM) at

37°C for 24 h and then incubated with 2 µM rhodamine 123 at

37°C in the dark for 30 min. Fluorescence intensity was detected

using the Flow Sight flow cytometer (Amnis Corporation) and data

were analyzed using IDEAS software v6.1 (Amnis Corporation).

Western blotting

Cells treated with 20(S)-GRh2 (35 and 45 µM)

at 37°C for 24 h were lysed in RIPA buffer (Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology) pre-cooled at 4°C. Mitochondrial and cytoplasmic

proteins were extracted using a cell mitochondrial isolation kit

(Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). Protein quantification was

performed using the BCA method (Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology). Equal amounts of protein (30 µg) were

subjected to 12% SDS-PAGE and then transferred onto a

nitrocellulose membrane (Pall Corporation). The membranes were

blocked with 5% skim milk powder and PBS for 1 h at room

temperature, then incubated with primary antibodies overnight at

4°C, followed by incubation with goat polyclonal secondary antibody

to mouse IgG-H&L (HRP) (1:1,000; cat. no. 115-005-00; Jackson

ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc.) and goat anti-rabbit IgG H&L

(HRP) (1:1,000; cat. no. 111-005-003; Jackson ImmunoResearch

Laboratories, Inc.) for 1 h at 37°C. Development was performed with

an ECL kit (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). Imaging and

densitometric analysis were performed using an iBright FL1000

imaging system (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

β-actin and prohibitin were used as loading controls.

Measurement of cellular ATP levels

Total ATP levels were determined using a

Chemiluminescence ATP assay kit (Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Briefly, the culture solution was removed, followed by addition of

200 µl lysate to each well of a six-well plate and

centrifuged at 12,000 × g to collect the cell supernatant. In

addition, 100 µl ATP detection working solution was added to

the 96-well assay plates and incubated at room temperature for 3

min. Subsequently, 20 µl sample was added to the wells and

analyzed on the Infinite M200 pro reader (Tecan Group, Ltd.).

Meanwhile, added gradient diluions of ATP standard solution were

added to 96-well plates to generate a standard curve, and ATP

concentration was calculated according to the standard curve.

Determination of reactive oxygen species

(ROS) levels

To detect intracellular ROS levels, the

ROS-sensitive probe 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate

(H2DCFDA; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) was used.

Cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of 20(S)-GRh2

(35 and 45 µM) for 24 h and then incubated with 10 µM

H2DCFDA in the dark for 30 min at 37°C. The fluorescence

intensity of the cells was measured with a Flow Sight flow

cytometer (Amnis Corporation).

Mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation

(OXPHOS) and glycolysis assays

A total of 5×103 HeLa cells were seeded

into the B-G pores of an XF 8 Cell Culture Microplate (Agilent

Technologies, Inc.) in 80 µl medium. Equal volumes of media

were then added into the A and H pores, followed by overnight

incubation at 37°C with 5% CO2. Only the calibration

solution was left on both sides of the culture chamber. HeLa cells

were treated with 20(S)-GRh2 (35 and 45 µM) for 24 h. The

probe plate of the Seahorse XFp sensor was incubated overnight in

the calibration solution the day before the experiment. Cells were

washed with 180 µl DMEM without bicarbonate and then

incubated at 37°C for 1 h before measurement.

Oxygen consumption rates (OCR) and extracellular

acidification rates (ECAR) were measured using an XFp Extracellular

Flux Analyzer (Agilent Technologies, Inc.) according to

manufacturer′s instructions. The OCR was continuously recorded for

12 cycles, with each cycle consisting of 3 min of mixing and 3 min

of measurement. Basal respiration was measured during cycles 1-3.

Further measurement of OCR was run as follows: As 4-6 cycles of

oligomycin injection (oligo, ATP synthase inhibitor, 5 µM),

7-9 cycles of carbonyl cyanide 4-(trifluoromethoxy) phenylhydrazone

(FCCP, proton, 5 µM) injection and 10-12 cycles of

rotenone/antimycin A (AA/Rot, complex I and III inhibitor, 2.5

µM) injection [all, XFp Cell Mito Stress Test kit (Agilent

Technologies, Inc.)]. Further measurement of ECAR was run as

follows: 4-6 cycles of glucose (substrate for hexokinase, 10 mM)

injection, 7-9 cycles of oligomycin (oligo, ATP synthase inhibitor,

5 µM) injection and 10-12 cycles of 2-Deoxy-D-glucose (2-DG,

competitive inhibitor of hexokinase, 50 mM) injection. The use of

these inhibitors permits the determination of key aspects of

mitochondrial function (31).

Caspase activity assays

Assays for caspase-3 (cat. no. C1115), -8 (cat. no.

C1151) and -9 (cat. no. C1157) activities were performed using kits

according to the manufacturer′s instructions (Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology). Briefly, cells were washed with PBS, collected by

centrifugation (600 × g, 5 min) at 4°C and resuspended in ice cold

lysis buffer. A total of 100 µl lysate was used per

2×106 cells and incubated on ice for 20 min. The protein

concentration in the supernatant was measured with a Bradford assay

kit (Tiangen Biotech Co., Ltd.). Subsequently, 50 µl cell

lysate supernatant was mixed with 10 µl Ac-DEVD-pNA (2 mM)

for caspase-3, Ac-IETD-pNA (2 mM) for caspase-8 and Ac-LEHD-pNA (2

mM) for caspase-9 in 40 µl assay buffer for 4 h at 37°C, and

then analyzed with an Infinite M200 pro reader (Tecan Group,

Ltd.).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad

Prism software 6 (GraphPad Software, Inc.). In quantitative

analyses shown in histograms, values were obtained from three

independent experiments and expressed as the mean ± SD. One-way

ANOVA followed by Dunnett′s post-hoc test was used to compare

between two groups. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

20(S)-GRh2 inhibits cell viability and

induces apoptosis in HeLa cells

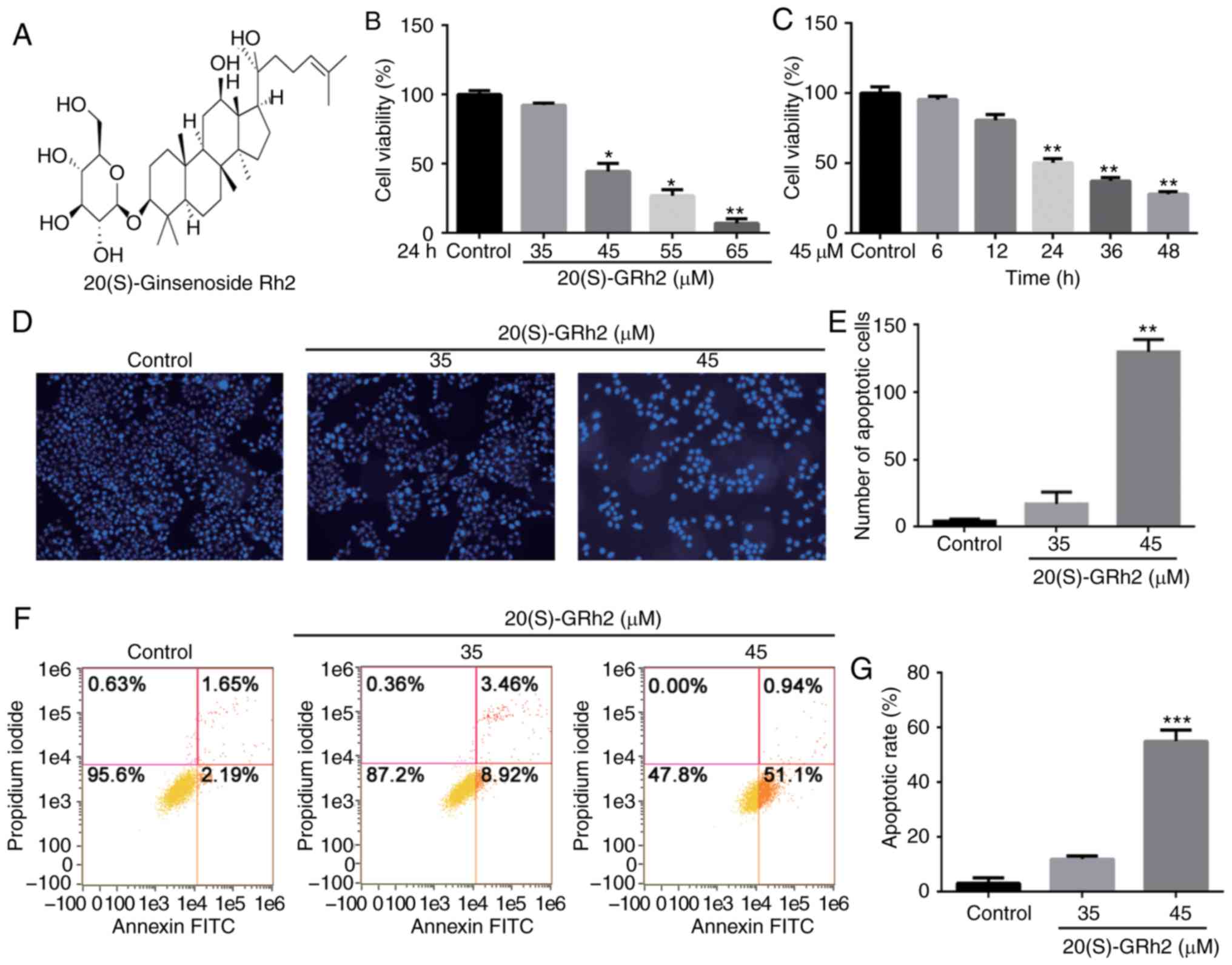

The CCK-8 method was used to examine the effect of

20(S)-GRh2 (Fig. 1A) on HeLa cell

viability. Cells were treated with various doses of 20(S)-GRh2 for

different timepoints. The results showed that 20(S)-GRh2 reduced

the viability of HeLa cells in dose- and time-dependent manners

(Fig. 1B and C). The

IC50 of 20(S)-GRh2 was calculated to be ~45 µM,

and 35 and 45 µM for further experiments.

It was next examined whether 20(S)-GRh2 inhibited

cell viability via inducing apoptosis. Hoechst staining showed an

increase in the amount of condensed and fragmented nuclei in cells

treated with 45 µM 20(S)-GRh2 compared with the control

group (Fig. 1D and E), indicating

that 20(S)-GRh2 induced apoptosis in HeLa cells. Annexin V and PI

double staining was used to detect the apoptotic rate of HeLa cells

treated with 20(S)-GRh2. The percentages of apoptotic cells upon

treatment with 0, 35 and 45 µM 20(S)-GRh2 were 3.84, 12.38

and 52.04%, respectively (Fig. 1F and

G). Taken together, these findings suggested that 20(S)-GRh2

reduces cell viability by inducing apoptosis in HeLa cells.

20(S)-GRh2 reduces MMP, decreases ATP

generation and induces ROS in HeLa cells

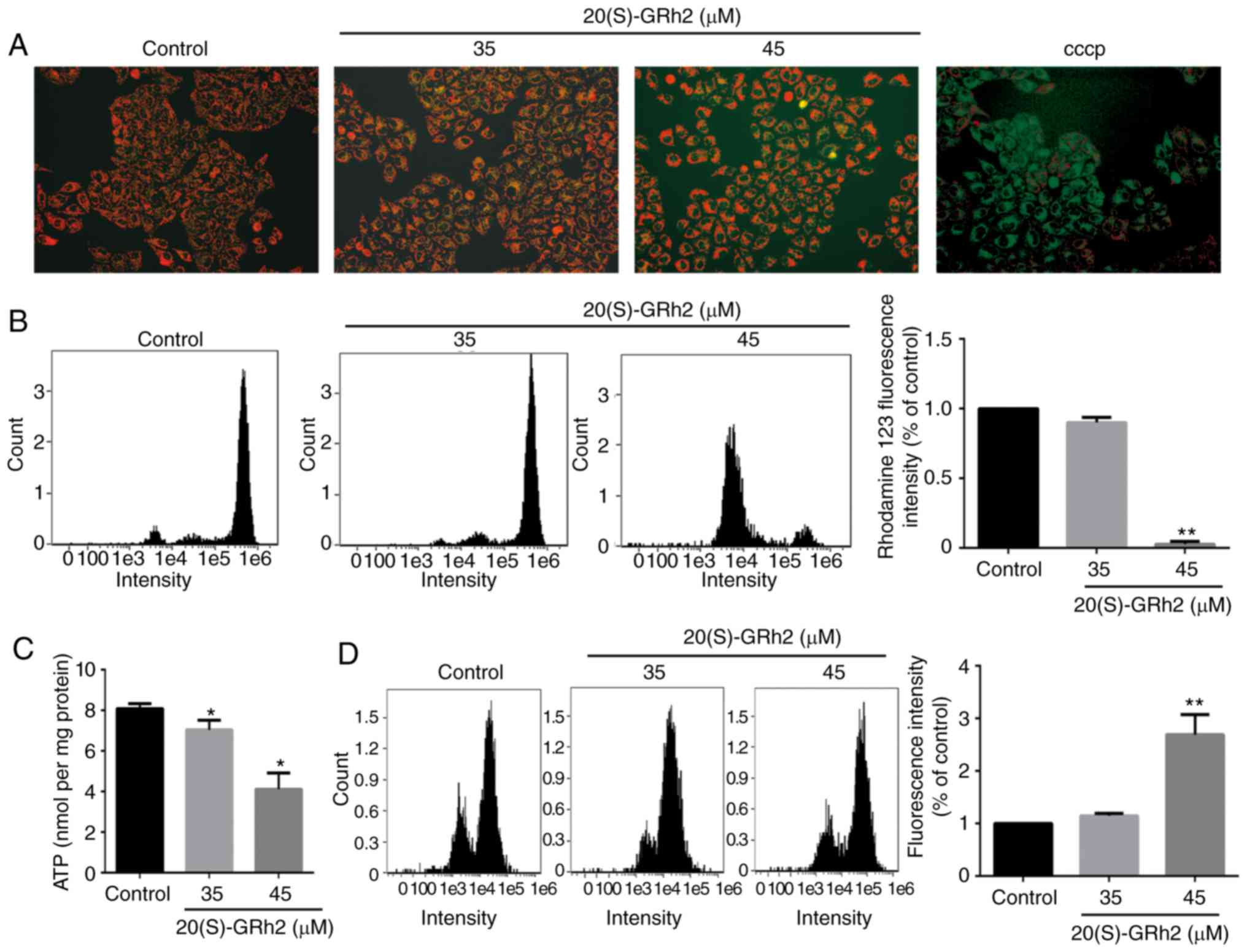

Mitochondria play a central role in the growth and

apoptosis of cells (32).

Therefore, it was next assessed whether 20(S)-GRh2-induced

apoptosis was associated with mitochondrial dysfunction. The

effects of 20(S)-GRh2 on the MMP, an indicator of mitochondrial

functions, were assessed using JC-1 and rhodamine-123 staining.

Fluorescence microscopy showed that cells exposed to 20(S)-GRh2

showed increased conversion of JC-1 aggregates (red) to JC-1

monomers (green). Following treatment with 10 µM CCCP as the

positive control, the cells showed obvious green fluorescence,

indicating that 10 µM CCCP almost completely depleted the

MMP of HeLa cells (Fig. 2A). Flow

cytometry showed that 45 µM 20(S)-GRh2 treatment

significantly reduced the fluorescence intensity of rhodamine-123

(Fig. 2B). MMP and ATP generation

are indicators of mitochondrial function (33), and thus the effects of 20(S)-GRh2

on the cellular ATP levels were assessed. Compared with the control

group, 20(S)-GRh2 exposure reduced cellular ATP levels in HeLa

cells by 14% (35 µM) and 49% (45 µM) (Fig. 2C). The decrease in MMP and ATP

levels showed that 20(S)-GRh2 induced mitochondrial dysfunction in

HeLa cells.

It was hypothesized that 20(S)-GRh2-induced

mitochondrial dysfunction may cause increased levels of ROS. To

test this hypothesis, ROS levels in 20(S)-GRh2-treated HeLa cells

were measured. Low concentrations of 20(S)-GRh2 (35 µM) had

no significant effect on cellular ROS, whereas a high concentration

of 20(S)-GRh2 (45 µM) significantly increased cellular ROS

by 2.69-fold compared with control cells (Fig. 2D).

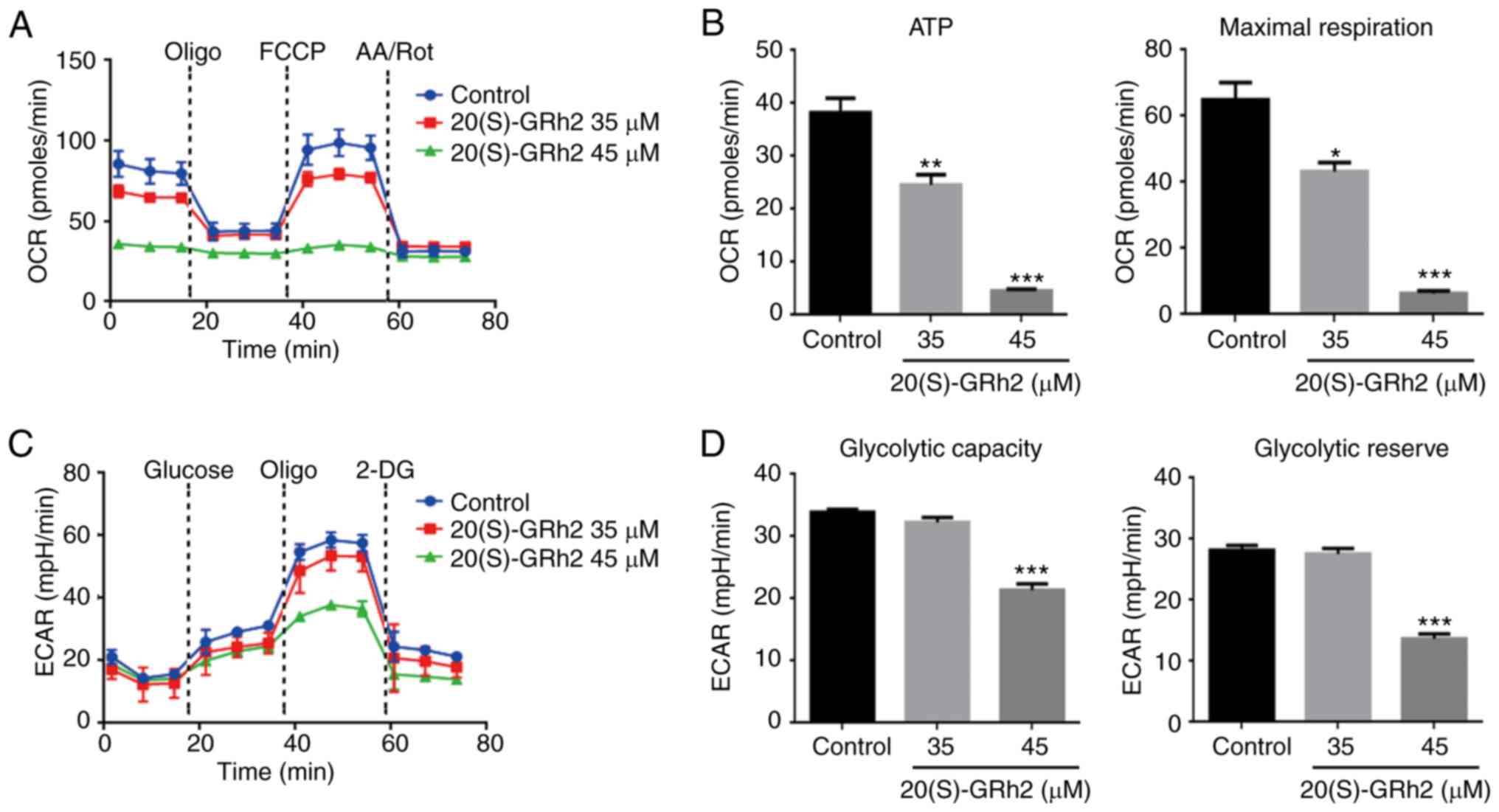

20(S)-GRh2 inhibits mitochondrial OXPHOS

and glycolysis

Since the mitochondrial electron transfer chain is

the main target site of ROS (34), the present study hypothesized that

20(S)-GRh2 might affect mitochondrial ATP generation, which is

involved in 20(S)-GRh2-induced cell death. The XFp extracellular

flux analyzer was then used to assess the role of 20(S)-GRh2 on

mitochondrial OXPHOS and glycolysis, the two major energy

metabolism pathways, in real-time. OXPHOS was measured by

quantifying the OCR of the medium and glycolysis was assessed by

quantifying the ECAR of the medium. Treatment with 20(S)-GRh2 (35

and 45 µM) caused a decrease in the OCR and altered cellular

responses to typical mitochondrial complexes inhibitors (including

oligomycin, an ATP synthase inhibitor; FCCP, a mitochondrial

uncoupler and AA/Rot, inhibitors of complex I and III), suggesting

that the mitochondrial OXPHOS capacity was inhibited (Fig. 3A). HeLa cells had a significantly

reduced OCR linked to ATP production and maximum respiratory

capacity following 20(S)-GRh2 (35 and 45 µM) treatment

(Fig. 3B). However, in HeLa cells

treated with 20(S)-GRh2, the OCR associated with non-mitochondrial

respiration was also reduced (Fig.

3A). This result indicated that 20(S)-GRh2 may also inhibit the

oxygen consumption of the non-mitochondrial respiratory pathway,

but the exact molecular mechanism was unclear.

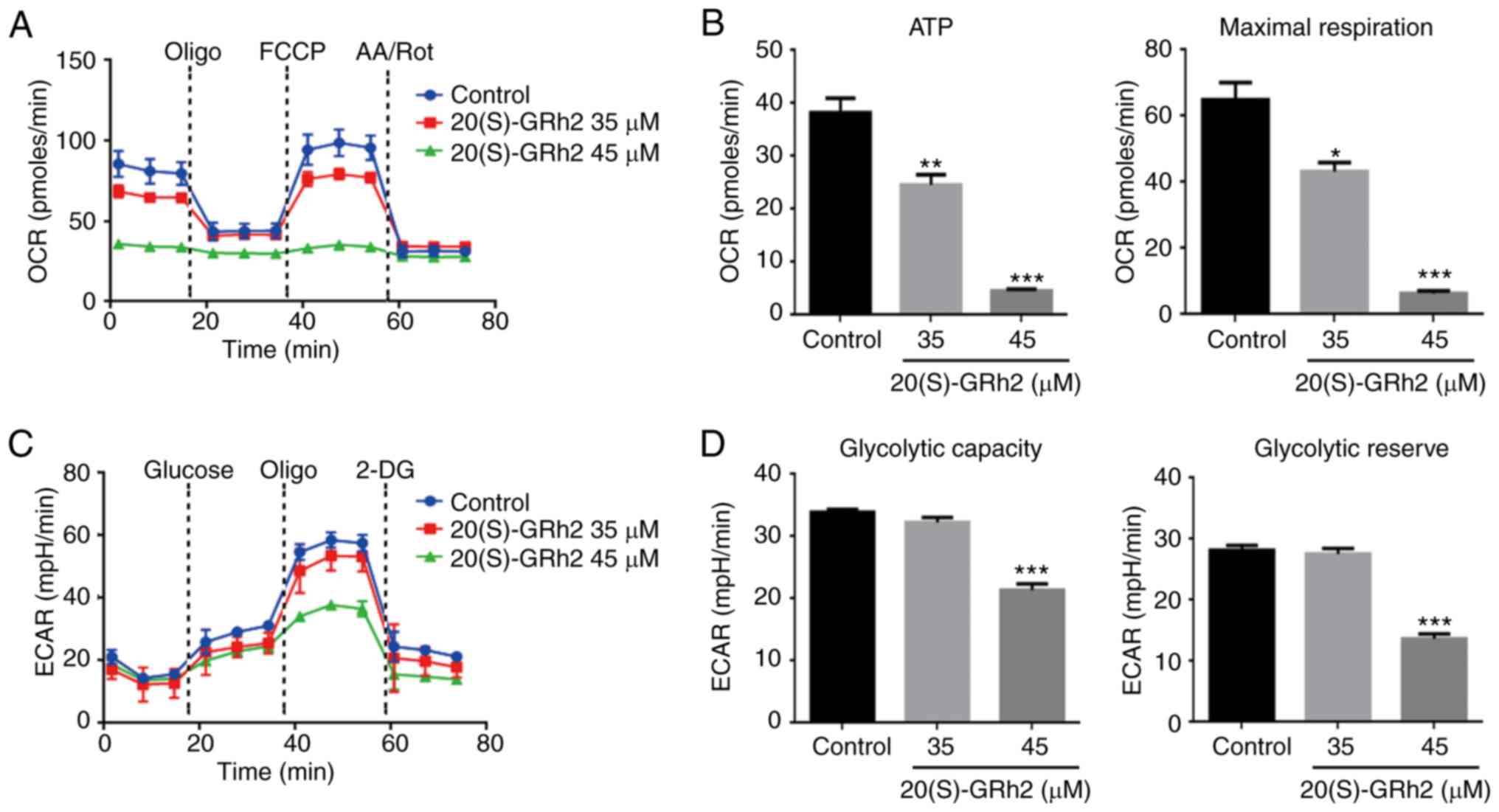

| Figure 3Effects of 20(S)-GRh2 on

mitochondrial respiration and glycolysis. HeLa cells were treated

with 20(S)-GRh2 at indicated concentrations for 24 h and the

dynamics of OCR and ECAR were measured. (A) Graphical

representation of the OCR measurement over time; sequential

additions are indicated as: Oligo, FCCP and AA/Rot. (B) The effects

of 20(S)-GRh2 on the ATP-linked OCR and maximal respiration

capacity-linked OCR calculated from the OCR curves. Data analyzed

using one-way ANOVA and presented as the mean ± standard deviation.

n=3. *P<0.05; **P<0.01 and

***P<0.001 vs. control. (C) Graphical representation

of the ECAR measurement over time; sequential additions are

indicated as: Glucose, Oligo and 2-DG. (D) The effects of

20(S)-GRh2 on the glycolytic capacity-linked ECAR and glycolytic

reserve-linked ECAR calculated from the ECAR curves. Data were

analyzed using one-way ANOVA and presented as the mean ± standard

deviation. n=3. ***P<0.001 vs. control. 20(S)-GRh2,

20(S)-ginsenoside Rh2; OCR, oxygen consumption rate; ECAR,

extracellular acidification rate; Oligo, oligomycin; FCCP, carbonyl

cyanide 4-(trifluoromethoxy) phenylhydrazone; AA/Rot, antimycin

A/rote-none; 2-DG, 2-Deoxy-D-glucose; mpH/min, the rate of mpH

change per minute. |

Numerous cancer cells break down glucose by aerobic

glycolysis to obtain the energy needed for growth in a process

known as the Warburg effect (35). It was next examined whether

20(S)-GRh2 also induced this effect on glycolysis in HeLa cells.

The results showed that both basal and stimulated ECAR reduced

after 45 µM 20(S)-GRh2 treatment (Fig. 3C). 20(S)-GRh2 (45 µM)

significantly reduced the ECAR linked to glycolytic capacity and

the glycolytic reserve in HeLa cells (Fig. 3D). At 35 µM, 20(S)-GRh2 had

no effect on ECAR (Fig. 3C) but

inhibited OCR (Fig. 3A) and

decreased cellular ATP levels (Figs.

2C and 3B), suggesting that

20(S)-GRh2 decreased ATP production primarily by inhibition of

OXPHOS.

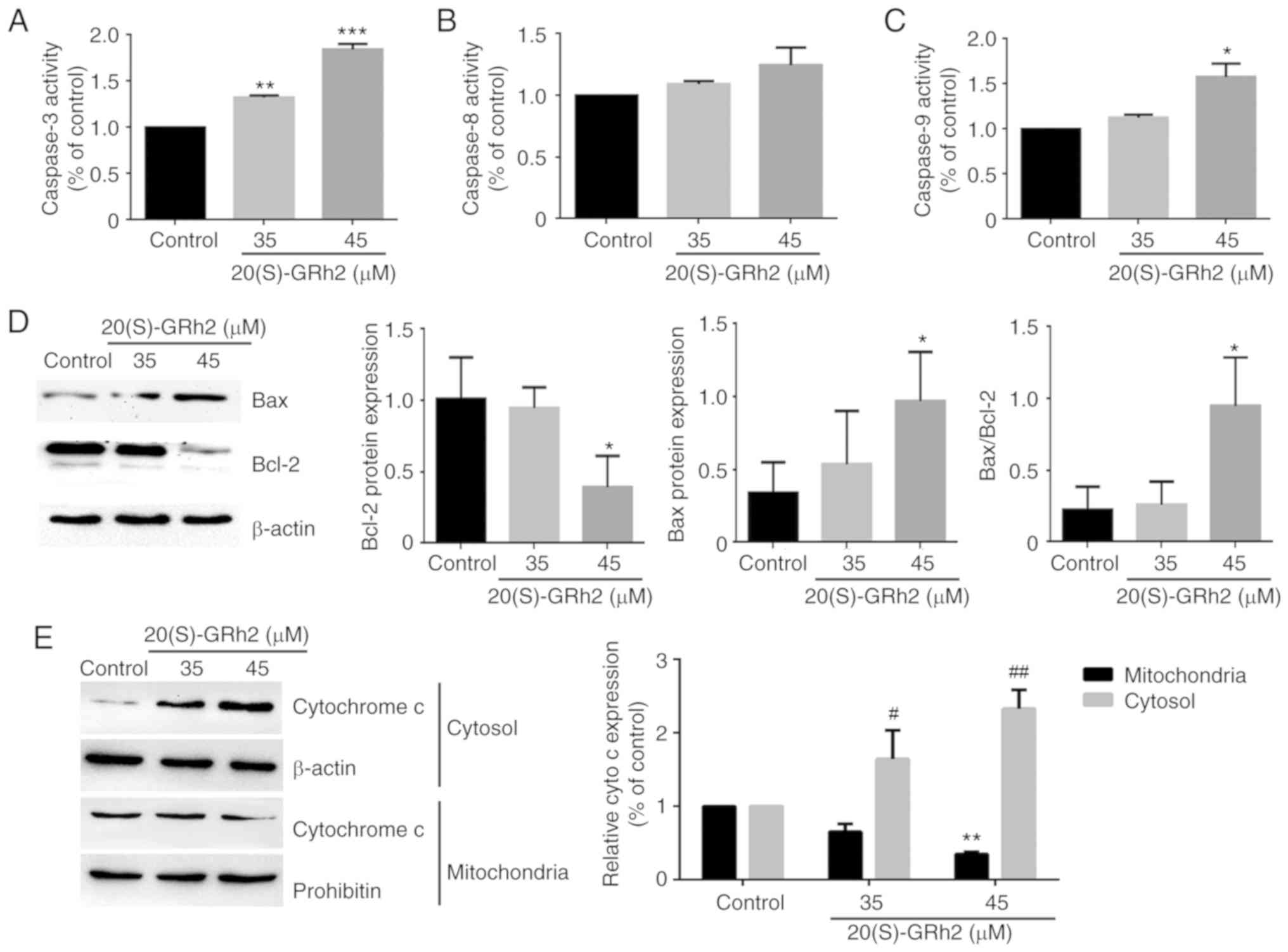

Mitochondrial pathway is involved in

20(S)-GRh2-induced HeLa cell apoptosis

To further assess the apoptotic process induced by

20(S)-GRh2, the activation of caspase-3, a critical marker of

apoptosis, was investigated. As shown in Fig. 4A, 20(S)-GRh2 treatment

significantly increased caspase-3 activity in a dose-dependent

manner. Next, the upstream regulators of caspase-3 involved in

20(S)-GRh2-induced apoptosis were determined.

Mitochondrion-associated caspase-9 activity was significantly

increased by 45 µM 20(S)-GRh2 but did not affect death

receptor-associated caspase-8 activity in HeLa cells (Fig. 4B and C). Since caspase-9 is

activated by Bcl-2 family proteins (36), it was investigated whether

20(S)-GRh2 affected the expression of Bcl-2 and Bax proteins. 45

µM 20(S)-GRh2 induced Bax upregulation and Bcl-2

downregulation (Fig. 4D). Bcl-2

and Bax induces the release of cytochrome c from the

mitochondria into the cytoplasm (37). Western blot analysis showed that

20(S)-GRh2 significantly promoted the release of cytochrome

c into the cytoplasm, which coincided with caspase-9

activation (Fig. 4E). Once

cytochrome c is released into the cytoplasm, it activates

caspase-9, triggering a cascade causing mitochondrion-mediated

apoptosis (38); hence, the

results indicated that 20(S)-GRh2 induces apoptosis via the

mitochondrial pathway (Fig.

4E).

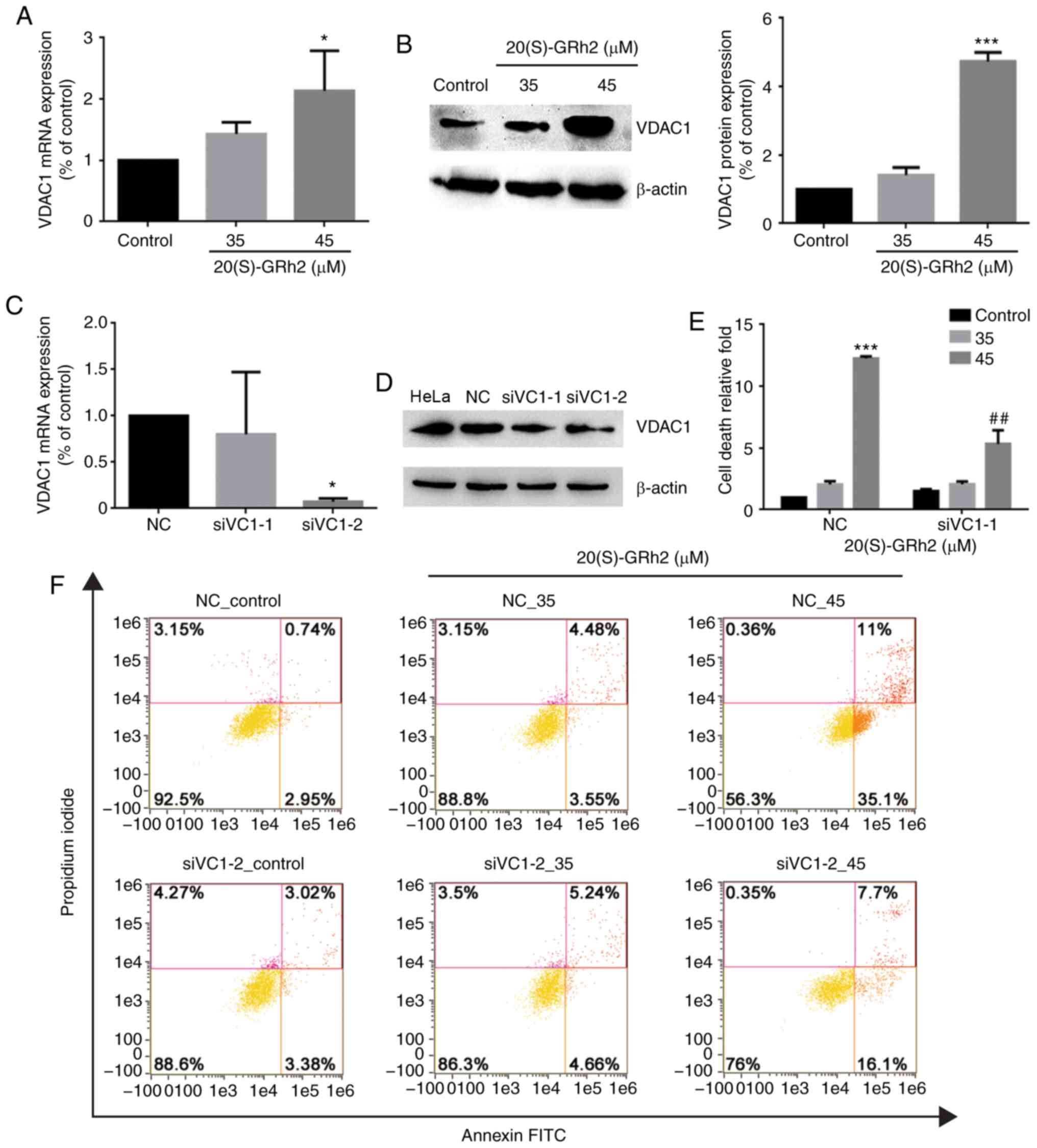

Upregulation of VDAC1 plays a role in

20(S)-GRh2-induced apoptosis

VDAC1 plays an important role in regulating

mitochondrial energy metabolism and mitochondrion-mediated

apoptosis (39). Therefore, the

role of VDAC1 in 20(S)-GRh2-induced apoptosis was assessed. VDAC1

expression in HeLa cells was significantly increased by 45

µM 20(S)-GRh2 treatment (Fig.

5A and B), indicating that induction of VDAC1 may be involved

in 20(S)-GRh2-mediated induction of apoptosis in HeLa cells. To

determine the role of VDAC1 in HeLa cell apoptosis induced by

20(S)-GRh2, a synthetic siRNA targeting VDAC1 to knockdown VDAC1 in

HeLa cells was used (Fig. 5C and

D). Annexin V staining showed that 20(S)-GRh2-induced apoptosis

was suppressed in VDAC1-silenced cells (Fig. 5E and F). These results showed that

20(S)-GRh2 induced apoptosis in HeLa cells by regulating VDAC1.

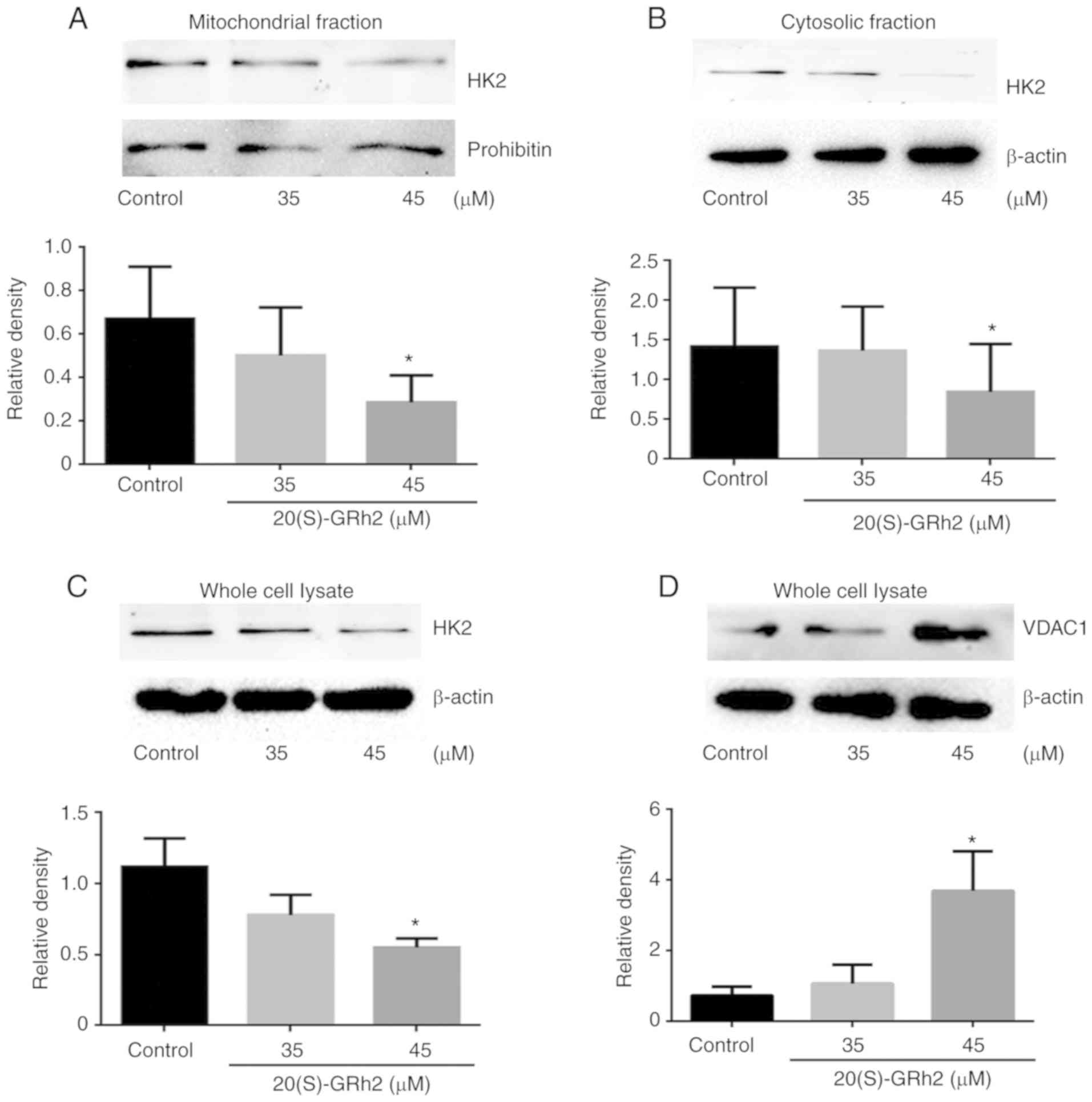

20(S)-GRh2-induced reduction of HK2

results in VDAC1 upregulation

To further elucidate the molecular mechanism

underlying 20(S)-GRh2-induced VDAC1 upregulation on HeLa cell

apoptosis, known VDAC1-binding proteins were investigated. HK2

interacts with VDAC1 and plays major roles in tumor cell

metabolism, including mitochondrial ATP synthesis and glucose

metabolism (40). HK2 also

inhibits tumor cell apoptosis by inhibiting changes in

mitochondrial membrane permeability (41). Therefore, HK2 expression was

measured. It was found that the expression of mitochondrial HK2 and

cytosolic HK2 in HeLa cells treated with 45 µM 20(S)-GRh2

was decreased which was consistent with the pattern of total HK2

(Fig. 6A-C). By contrast, the

expression levels of VDAC1 protein was increased in response to 45

µM 20(S)-GRh2 (Fig. 6D),

indicating that 20(S)-GRh2 induces changes in the expression levels

of HK2 and VDAC1 that are closely related to its induction of

apoptosis.

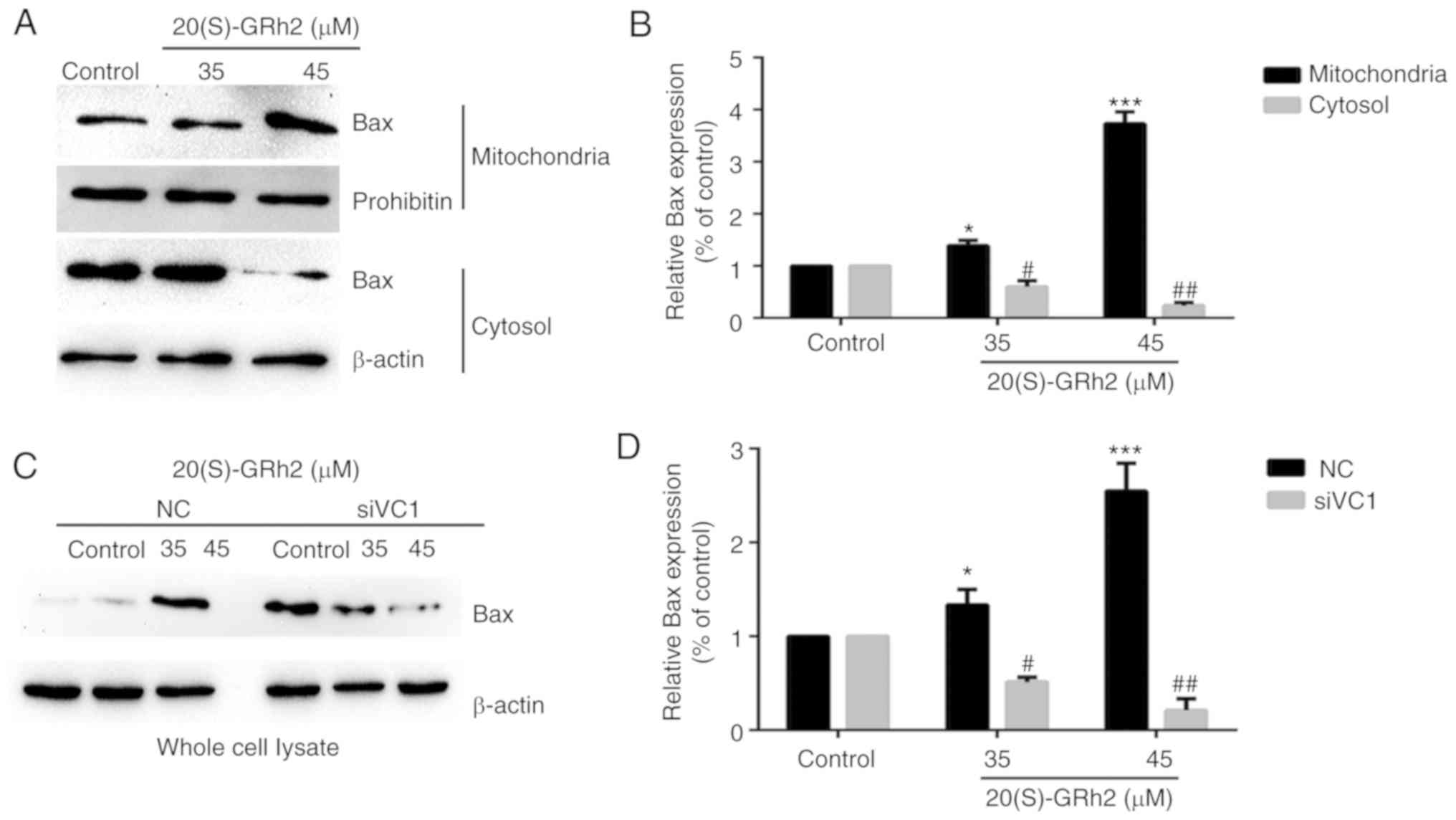

Bax expression is involved in

20(S)-GRh2-induced apoptosis

It was found that 20(S)-GRh2 treatment induced Bax

upregulation and promoted Bax translocation to the mitochondria

(Fig. 7A and B). Bax expression

was significantly suppressed when VDAC1 was silenced by siRNA

(Fig. 7C and D). The

aforementioned results showed that the separation of HK2 from the

mitochondria promoted the translocation of Bax to mitochondria and

the release of cytochrome cinto the cytoplasm.

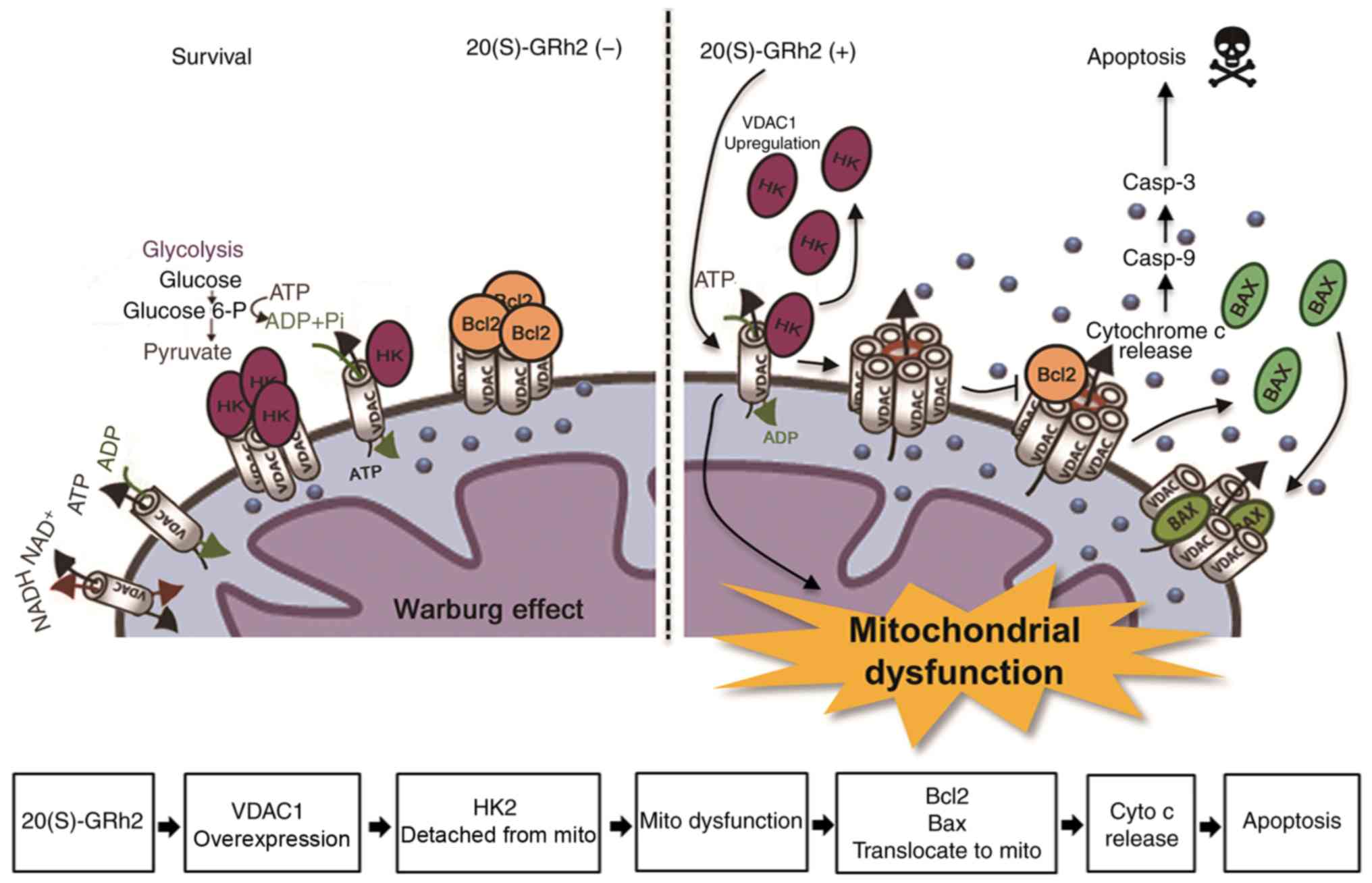

We hypothesize that treatment of HeLa cells with

20(S)-GRh2 causes metabolic stress leading to upregulation of

VDAC1, the translocation of Bax to the mitochondria and subsequent

apoptosis of cancer cells (Fig.

8).

Discussion

The present study found that 20(S)-GRh2, a

pharmacologically active component of Panax ginseng, exerted

significant cytotoxicity in HeLa cells. Exposure to 20(S)-GRh2

altered mitochondrial function in HeLa cells, leading to

mitochondrion-related apoptosis, confirming that 20(S)-GRh2 induces

apoptosis of HeLa cells, as reported previously (25,42). In addition, cell death induced by

20(S)-GRh2 was associated with the regulation of energy metabolism.

Treatment with 20(S)-GRh2 significantly inhibited OXPHOS and

glycolysis. The dual targeting of mitochondrial and glycolysis

pathways by 20(S)-GRh2 may explain why ROS generation, MMP collapse

and ATP reduction were observed in HeLa cells treated with

20(S)-GRh2.

In addition, the OCR that corresponds to

non-mitochondrial O2 consumption was also slightly

affected by 20(S)-GRh2. Mitochondria consume >95% of the

O2 of aerobic higher organisms; however, 10% of cellular

oxygen uptake in mammal cells is due to non-mitochondrial

respiration (43). It has been

proposed that an increase in non-mitochondrial oxygen consumption

might serve as a protective mechanism to remove ROS when it is

present at potentially harmful concentrations (44). This suggestion provides a

plausible explanation for the decrease in non-mitochondrial oxygen

consumption observed in the present study, as it would help

increase in ROS generation and oxidative stress to further induce

apoptosis.

The mechanism by which 20(S)-GRh2 regulates cell

death and energy metabolism was next elucidated. 20(S)-GRh2

influenced the protein levels of VDAC1 and HK2, which are important

regulators of glucose metabolism (45,46), and the changes in VDAC1 and HK2

protein levels were inversely associated. Treatment with 20(S)-GRh2

inhibited mitochondrial metabolism, leading to dissociation of HK2

from mitochondrial VDAC1, which regulated the transfer of Bax to

the mitochondria and allowed cytochrome c to enter the

cytosol via the outer mitochondrial membrane. These events led to

apoptosis induced by metabolic stress. A loss of the MMP during

20(S)-GRh2-induced apoptosis and the opening of mitochondrial

permeability transition pores were observed. The present findings

are the first to show that this mechanism is associated with

20(S)-GRh2-induced apoptosis. These results also showed that VDAC1

may be a target in the process of HeLa cell apoptosis induced by

20(S)-GRh2.

By transferring HK2 to the mitochondria, an acidic

anti-hypoxic microenvironment suitable for tumor cell survival can

be formed and maintained (47).

The interaction between HK2 and VDAC1 provides metabolic

preponderance for cancer cells by enhancing anaerobic glycolysis,

which is called the Warburg effect (48). When HK2 separates from the

mitochondria, cells become sensitive to many apoptotic factors

(49). Many anticancer compounds

that target the mitochondria have been shown to release HK2 from

the mitochondria (50-52). The present study found that

20(S)-GRh2 disaggregated HK2 from the mitochondria in HeLa cells.

However, whether desorption of HK2 was due solely to the direct

interaction of 20(S)-GRh2 with VDAC1 was unclear, and an

interaction between 20(S)-GRh2 and HK2 cannot be ruled out. Thus,

20(S)-GRh2-induced cell death is a cumulative effect of VDAC1

blockade and desorption of HK2 from mitochondria. ROS production,

MMP collapse and ATP decrease may be the result of VDAC shutdown.

The wide range of antitumor activities of 20(S)-GRh2 includes

inhibiting tumor growth, restraining tumor progression and

strengthening chemotherapeutic responses (24). Previous studies have shown that

20(S)-GRh2 inhibits the growth of many tumor cell types and its

potential mechanism has been confirmed. Ginsenoside Rh2 also

inhibited proliferation and promotes apoptosis of H1299 cells by

inducing endoplasmic reticulum stress mediated by ROS (53). The synergistic effect of autophagy

and β-catenin signal transduction inhibited the proliferation and

migration of human liver cancer HepG2, Hep3B and Huh7 cells, and

restrained tumor growth in HepG2-xenografted mice (54,55). Ginsenoside Rh2 inhibited cell

proliferation, promoted apoptosis and reversed the resistance of

colon cancer to the chemotherapeutic drug oxaliplatin (56). The p53 tumor suppressor is also

activated in response to ginsenosides (25,57). Ginsenoside Rh2 also induced

apoptosis of HCT-116 and SW-480 cells via p53 activation (58).

In conclusion, the present findings have revealed

VDAC1 as a new target of 20(S)-GRh2. These results have provided

further understanding of the metabolic mechanism of ginsenoside Rh2

against cancer and have validated the potential clinical value for

20(S)-GRh2 or anticancer drugs based on 20(S)-GRh2 in cervical

cancer in vitro. However, the present study only studied a

human papillomavirus (HPV)-positive cervical cancer cell. Based on

evidence suggesting the heterogeneity in cervical cancer-related

pathways in terms of HPV status, we are currently examining the

effects of 20(S)-GRh2 in a comprehensive panel of human cervical

cancer-derived cell lines, including HPV-positive and HPV-negative

cell lines. Future research will examine the efficacy of 20(S)-GRh2

in an in vivo system.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key Research

and Development program of China (grant no. 2017YFC1702104) and

grants from the National Natural Foundation of China (grant no.

81703663); and Key Project At Central Government Level: The Ability

Establishment of Sustainable Use For Valuable Chinese Medicine

Resources (grant no. 2060302).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current

study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors′ contributions

ML and JW managed data collection and designed the

experiments. YL, JQ, SL and SW performed the experiments. YL and ML

wrote the manuscript. DZ and XB contributed to data analysis,

supervised the experiments and helped draft the manuscript. All

authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

References

|

1

|

Chen S and Wang J: HAND2-AS1 inhibits

invasion and metastasis of cervical cancer cells via

microRNA-330-5p-mediated LDOC1. Cancer Cell Int. 19:3532019.

View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

2

|

Arbyn M, Weiderpass E, Bruni L, de Sanjosé

S, Saraiya M, Ferlay J and Bray F: Estimates of incidence and

mortality of cervical cancer in 2018: A worldwide analysis. Lancet

Glob Health. 8:e191–e203. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

3

|

Di J, Rutherford S and Chu C: Review of

the cervical cancer burden and population-based cervical cancer

screening in China. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 16:7401–7407. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Iwata T, Miyauchi A, Suga Y, Nishio H,

Nakamura M, Ohno A, Hirao N, Morisada T, Tanaka K, Ueyama H, et al:

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy for locally advanced cervical cancer. Chin

J Cancer Res. 28:235–240. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Marchetti C, Fagotti A, Tombolini V,

Scambia G and De Felice F: Survival and toxicity in neoadjuvant

chemotherapy plus surgery versus definitive chemoradiotherapy for

cervical cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer

Treat Rev. 83:1019452020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Shoshan-Barmatz V, Ben-Hail D, Admoni L,

Krelin Y and Tripathi SS: The mitochondrial voltage-dependent anion

channel 1 in tumor cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1848:2547–2575.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Abu-Hamad S, Zaid H, Israelson A, Nahon E

and Shoshan-Barmatz V: Hexokinase-I protection against apoptotic

cell death is mediated via interaction with the voltage-dependent

anion channel-1: Mapping the site of binding. J Biol Chem.

283:13482–13490. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Shoshan-Barmatz V, Israelson A, Brdiczka D

and Sheu SS: The voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC): Function

in intracellular signalling, cell life and cell death. Curr Pharm

Des. 12:2249–2270. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Adachi M, Higuchi H, Miura S, Azuma T,

Inokuchi S, Saito H, Kato S and Ishii H: Bax interacts with the

voltage-dependent anion channel and mediates ethanol-induced

apoptosis in rat hepatocytes. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver

Physiol. 287:G695–G705. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Zaid H, Abu-Hamad S, Israelson A, Nathan I

and Shoshan-Barmatz V: The voltage-dependent anion channel-1

modulates apoptotic cell death. Cell Death Differ. 12:751–760.

2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Yamamoto T, Yamada A, Watanabe M,

Yoshimura Y, Yamazaki N, Yoshimura Y, Yamauchi T, Kataoka M, Nagata

T, Terada H and Shinohara Y: VDAC1, having a shorter N-terminus

than VDAC2 but showing the same migration in an SDS-polyacrylamide

gel, is the predominant form expressed in mitochondria of various

tissues. J Proteome Res. 5:3336–3344. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Li B, Chen X, Yang W, He J, He K, Xia Z,

Zhang J and Xiang G: Single-walled carbon nanohorn aggregates

promotes mitochondrial dysfunction-induced apoptosis in

hepatoblastoma cells by targeting SIRT3. Int J Oncol. 53:1129–1137.

2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Nagakannan P, Islam MI, Karimi-Abdolrezaee

S and Eftekharpour E: Inhibition of VDAC1 protects against

glutamate-induced oxytosis and mitochondrial fragmentation in

hippocampal HT22 cells. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 39:73–85. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Tewari D, Ahmed T, Chirasani VR, Singh PK,

Maji SK, Senapati S and Bera AK: Modulation of the mitochondrial

voltage dependent anion channel (VDAC) by curcumin. Biochim Biophys

Acta. 1848:151–158. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Watanabe M, Funakoshi T, Unuma K, Aki T

and Uemura K: Activation of the ubiquitin-proteasome system against

arsenic trioxide cardiotoxicity involves ubiquitin ligase Parkin

for mitochondrial homeostasis. Toxicology. 322:43–50. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Rimmerman N, Ben-Hail D, Porat Z, Juknat

A, Kozela E, Daniels MP, Connelly PS, Leishman E, Bradshaw HB,

Shoshan-Barmatz V and Vogel Z: Direct modulation of the outer

mitochondrial membrane channel, voltage-dependent anion channel 1

(VDAC1) by cannabidiol: A novel mechanism for cannabinoid-induced

cell death. Cell Death Dis. 4. pp. e9492013, View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Liu Y, Cheng H, Zhou Y, Zhu Y, Bian R,

Chen Y, Li C, Ma Q, Zheng Q, Zhang Y, et al: Myostatin induces

mitochondrial metabolic alteration and typical apoptosis in cancer

cells. Cell Death Dis. 4:e4942013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Pastorino JG and Hoek JB: Regulation of

hexokinase binding to VDAC. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 40:171–182. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Dolder M, Wendt S and Wallimann T:

Mitochondrial creatine kinase in contact sites: Interaction with

porin and adenine nucleotide translocase, role in permeability

transition and sensitivity to oxidative damage. Biol Signals

Recept. 10:93–111. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Warburg O: On the origin of cancer cells.

Science. 123:309–314. 1956. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC and Thompson

CB: Understanding the Warburg effect: The metabolic requirements of

cell proliferation. Science. 324:1029–1033. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Rai Y, Yadav P, Kumari N, Kalra N and

Bhatt AN: Hexokinase II inhibition by 3-bromopyruvate sensitizes

myeloid leukemic cells K-562 to anti-leukemic drug, daunorubicin.

Biosci Rep. 39:BSR201908802019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Guo X, Zhang X, Wang T, Xian S and Lu Y:

3-Bromopyruvate and sodium citrate induce apoptosis in human

gastric cancer cell line MGC-803 by inhibiting glycolysis and

promoting mitochondria-regulated apoptosis pathway. Biochem Biophys

Res Commun. 475:37–43. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Luo H, Vong CT, Chen H, Gao Y, Lyu P, Qiu

L, Zhao M, Liu Q, Cheng Z, Zou J, et al: Naturally occurring

anti-cancer compounds: Shining from Chinese herbal medicine. Chin

Med. 14:482019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Guo XX, Li Y, Sun C, Jiang D, Lin YJ, Jin

FX, Lee SK and Jin YH: p53-dependent Fas expression is critical for

ginsenoside Rh2 triggered caspase-8 activation in HeLa cells.

Protein Cell. 5:224–234. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Li S, Guo W, Gao Y and Liu Y: Ginsenoside

Rh2 inhibits growth of glioblastoma multiforme through mTor. Tumour

Biol. 36:2607–2612. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Popovich DG and Kitts DD:

Structure-function relationship exists for ginsenosides in reducing

cell proliferation and inducing apoptosis in the human leukemia

(THP-1) cell line. Arch Biochem Biophys. 406:1–8. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Guo XX, Guo Q, Li Y, Lee SK, Wei XN and

Jin YH: Ginsenoside Rh2 induces human hepatoma cell apoptosisvia

bax/bak triggered cytochrome C release and caspase-9/caspase-8

activation. Int J Mol Sci. 13:15523–15535. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Choi S, Oh JY and Kim SJ: Ginsenoside Rh2

induces Bcl-2 family proteins-mediated apoptosis in vitro and in

xenografts in vivo models. J Cell Biochem. 112:330–340. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Hu M, Crawford SA, Henstridge DC, Ng IH,

Boey EJ, Xu Y, Febbraio MA, Jans DA and Bogoyevitch MA: p32 protein

levels are integral to mitochondrial and endoplasmic reticulum

morphology, cell metabolism and survival. Biochem J. 453:381–391.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Zhao L, Zhu L and Guo X: Valproic acid

attenuates Aβ 25-35-induced neurotoxicity in PC12 cells through

suppression of mitochondria-mediated apoptotic pathway. Biomed

Pharmacother. 106:77–82. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Liberti MV and Locasale JW: The Warburg

effect: How does it benefit cancer cells? Trends Biochem Sci.

41:211–218. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Qu C, Zhang S, Wang W, Li M, Wang Y, van

der Heijde-Mulder M, Shokrollahi E, Hakim MS, Raat NJH,

Peppelenbosch MP and Pan Q: Mitochondrial electron transport chain

complex III sustains hepatitis E virus replication and represents

an antiviral target. FASEB J. 33:1008–1019. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

35

|

Pavithra PS, Mehta A and Verma RS:

Induction of apoptosis by essential oil from P. Missionis in skin

epidermoid cancer cells. Phytomedicine. 50:184–195. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Abbaszadeh H, Valizadeh A, Mahdavinia M,

Teimoori A, Pipelzadeh MH, Zeidooni L and Alboghobeish S:

3-Bromopyruvate potentiates TRAIL-induced apoptosis in human colon

cancer cells through a reactive oxygen species- and

caspase-dependent mitochondrial pathway. Can J Physiol Pharmacol.

97:1176–1184. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Pan X, Yan D, Wang D, Wu X, Zhao W, Lu Q

and Yan H: Mitochondrion-mediated apoptosis induced by acrylamide

is regulated by a balance between Nrf2 antioxidant and MAPK

signaling pathways in PC12 cells. Mol Neurobiol. 54:4781–4794.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Camara AKS, Zhou Y, Wen PC, Tajkhorshid E

and Kwok WM: Mitochondrial VDAC1: A key gatekeeper as potential

therapeutic target. Front Physiol. 8:4602017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Xue YN, Yu BB, Li JL, Guo R, Zhang LC, Sun

LK, Liu YN and Li Y: Zinc and p53 disrupt mitochondrial binding of

HK2 by phosphorylating VDAC1. Exp Cell Res. 374:249–258. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Li M, Shao J, Guo Z, Jin C, Wang L, Wang

F, Jia Y, Zhu Z, Zhang Z, Zhang F, et al: Novel

mitochondrion-targeting copper(II) complex induces HK2 malfunction

and inhibits glycolysis via Drp1-mediating mitophagy in HCC. J Cell

Mol Med. 24:3091–3107. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Shoshan-Barmatz V, Maldonado EN and Krelin

Y: VDAC1 at the crossroads of cell metabolism, apoptosis and cell

stress. Cell Stress. 1:11–36. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Ham YM, Lim JH, Na HK, Choi JS, Park BD,

Yim H and Lee SK: Ginsenoside-Rh2-induced mitochondrial

depolarization and apoptosis are associated with reactive oxygen

species- and Ca2+-mediated c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase 1 activation

in HeLa cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 319:1276–1285. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Brand MD and Nicholls DG: Assessing

mitochondrial dysfunction in cells. Biochem J. 435:297–312. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Bishop T and Brand MD: Processes

contributing to metabolic depression in hepatopancreas cells from

the snail Helix aspersa. J Exp Biol. 203:3603–3612. 2000.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Bustamante MF, Oliveira PG,

Garcia-Carbonell R, Croft AP, Smith JM, Serrano RL, Sanchez-Lopez

E, Liu X, Kisseleva T, Hay N, et al: Hexokinase 2 as a novel

selective metabolic target for rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis.

77:1636–1643. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Park SH, Lee AR, Choi K, Joung S, Yoon JB

and Kim S: TOMM20 as a potential therapeutic target of colorectal

cancer. BMB Rep. 52:712–717. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Pastorino JG and Hoek JB: Hexokinase II:

The integration of energy metabolism and control of apoptosis. Curr

Med Chem. 10:1535–1551. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Yuan S, Fu Y, Wang X, Shi H, Huang Y, Song

X, Li L, Song N and Luo Y: Voltage-dependent anion channel 1 is

involved in endostatin-induced endothelial cell apoptosis. FASEB J.

22:2809–2820. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Shoshan-Barmatz V and Ben-Hail D: VDAC, a

multi-functional mitochondrial protein as a pharmacological target.

Mitochondrion. 12:24–34. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Arbel N, Ben-Hail D and Shoshan-Barmatz V:

Mediation of the antiapoptotic activity of Bcl-xL protein upon

interaction with VDAC1 protein. J Biol Chem. 287:23152–23161. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Zheng Y, Shi Y, Tian C, Jiang C, Jin H,

Chen J, Almasan A, Tang H and Chen Q: Essential role of the

voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC) in mitochondrial

permeability transition pore opening and cytochrome c release

induced by arsenic trioxide. Oncogene. 23:1239–1247. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Tajeddine N, Galluzzi L, Kepp O, Hangen E,

Morselli E, Senovilla L, Araujo N, Pinna G, Larochette N, Zamzami

N, et al: Hierarchical involvement of Bak, VDAC1 and Bax in

cispl-atin-induced cell death. Oncogene. 27:4221–4232. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Li H, Huang N, Zhu W, Wu J, Yang X, Teng

W, Tian J, Fang Z, Luo Y, Chen M and Li Y: Modulation the crosstalk

between tumor-associated macrophages and non-small cell lung cancer

to inhibit tumor migration and invasion by ginsenoside Rh2. BMC

Cancer. 18:5792018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Li Q, Li B, Dong C, Wang Y and Li Q:

20(S)-Ginsenoside Rh2 suppresses proliferation and migration of

hepatocellular carcinoma cells by targeting EZH2 to regulate

CDKN2A-2B gene cluster transcription. Eur J Pharmacol. 815:173–180.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Zhang J, Li W, Yuan Q, Zhou J, Zhang J,

Cao Y, Fu G and Hu W: Transcriptome analyses of the

anti-proliferative effects of 20(S)-ginsenoside Rh2 on HepG2 cells.

Front Pharmacol. 10:13312019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Ma J, Gao G, Lu H, Fang D, Li L, Wei G,

Chen A, Yang Y, Zhang H and Huo J: Reversal effect of ginsenoside

Rh2 on oxaliplatin-resistant colon cancer cells and its mechanism.

Exp Ther Med. 18:630–636. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Li B, Zhao J, Wang CZ, Searle J, He TC,

Yuan CS and Du W: Ginsenoside Rh2 induces apoptosis and

paraptosis-like cell death in colorectal cancer cells through

activation of p53. Cancer Lett. 301:185–192. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Wang CZ, Zhang B, Song WX, Wang A, Ni M,

Luo X, Aung HH, Xie JT, Tong R, He TC and Yuan CS: Steamed American

ginseng berry: Ginsenoside analyses and anticancer activities. J

Agric Food Chem. 54:9936–9942. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|