1. Introduction

Tumor immunotherapy has shown great application

prospects by stimulating the body autoimmune system to balance the

immunosuppressive microenvironment, thereby improving the antitumor

effect (1). Immunotherapy

includes adoptive cell immunotherapy, immune checkpoint inhibitors,

cancer vaccines, costimulatory receptor agonists, monoclonal

anti-bodies (mAbs), and oncolytic virus therapy (2). In recent years, research on immune

checkpoint blockade has become a hotspot study in tumor

immunotherapy (3). Immune

checkpoint molecules are receptors on the surface of immune cells

that, after binding with their ligand, transduce inhibitory signals

or stimulatory signals (4). Drugs

that target immune checkpoint molecules, which can transduce the

inhibitory signals, are called checkpoint inhibitors. Among these

receptors, the most studied ones are cytotoxic

T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4), programmed death

receptor 1 (PD-1), programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1), T-cell

immunoglobulin and mucin domain-containing-3 (TIM-3), and

lymphocyte-activation gene 3 (LAG-3) (4,5).

Blocking tumor immune escape and tolerance mechanisms through

immune checkpoints is an effective way to enhance antitumor effect.

An immune checkpoint inhibitor, especially the mAb-based one, as an

immunoregulatory factor, can specifically bind to T cells or tumor

cells, thus enhancing the antitumor ability of T cells (6-8).

The traditional mAb-based immune checkpoint blockade

is the main method of tumor treatment and detection. Results of

preclinical studies and follow-up of clinical trials led to the

approval of various checkpoint inhibitors by the Food and Drug

Administration (FDA) for the treatment of renal cell carcinoma,

melanoma, lymphoma, classic Hodgkin lymphoma, pancreatic ductal

adenocarcinoma, cervical cancer, non-small cell lung cancer,

squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck, and breast ca, ncer.

Some immune checkpoint inhibitors approved, include mAbs targeting

PD-1 such as nivolumab (Opdivo®), pembrolizumab

(Keytruda®), cemiplimab (Sanofi, Regeneron); mAbs

targeting PD-L1 such as atezolizumab (Tecentriq®),

avelumab (Bavencio®) and durvalumab

(Imfinzi®); and mAb targeting CTLA-4 is represented by

ipilimumab (4,9-14).

Most tumor patients have benefitted from these antibodies, however

some have not responded to them (15). In addition, the characteristics of

mAbs such as poor stability, high production costs, poor tissue

penetration, and immune-related adverse events has limited their

utility (16-18).

To improve the therapeutic effect of antibodies for

immune checkpoint blockade, immune checkpoint expression should be

analyzed in patients before and during treatment. Due to the

heterogeneous and highly dynamic expression of the immune

checkpoint molecules in primary or metastatic tumors, traditional

immunohistochemical methods are limited because they cannot detect

the dynamic information of immune checkpoint molecules in the tumor

environment (19-30). Therefore, a real-time, dynamic,

and accurate detection method with high sensitivity resolution is

urgently required.

Methods involving imaging of labeled antibody

molecules have been reported, but the poor tissue penetration of

these antibodies, the long circulation time, and the high-contrast

imaging are obstacles that prevent them from becoming ideal imaging

agents (16,19,31). Thus, the development of tracers

with faster kinetics is of utmost importance.

To increase the effectiveness of immunotherapy,

including immune checkpoint blockade therapy, miniaturization of

antibodies, has been introduced. Nanobodies have a small molecular

weight conferring them a strong tissue penetration where they bind

their antigens quickly and specifically, while unbound nanobodies

can be quickly cleared through renal excretion. Therefore, compared

to mAbs, nanobodies produce higher target-to-background signals

soon after their administration (18).

Similar to mAb-based immune checkpoint inhibitors,

nanobodies that target immune checkpoint molecules have been

developed as effective tools for studying tumor immunotherapy and

immunoimaging (32). In this

review, some of the recent advances in the development of

nanobodies and nanobody-based immune checkpoint inhibitors for

immunotherapy and immunoimaging (Table I) were examined, as well as the

challenges faced to achieve successful use.

| Table ISummary of nanobodies targeting

immune checkpoints for immunotherapy and immunoimaging. |

Table I

Summary of nanobodies targeting

immune checkpoints for immunotherapy and immunoimaging.

| Target | Nanobody name | Target species | Application | Referred

studies |

|---|

| CTLA-4 | Nb16 | Human | Immunotherapy | (112) |

| CTLA-4 | Nb36 | Human | Immunoimaging | (135,136) |

| PD-L1 | B3 | Murine | Immunotherapy | (116) |

| PD-L1 | KN035 | Human | Immunotherapy | (117) |

| PD-L1 | Nb97 | Human | - | (118) |

| PD-L1 | - | Human | - | (119) |

| PD-L1 | Nb109 | Human | Immunoimaging | (132) |

| PD-L1 C | 3/E2 | Murine | Immunoimaging | (133) |

| PD-L1 | sdAb K2 | Human |

Immunotherapy/immunoimaging | (115,134) |

| TIM3 | - | Human | - | (124) |

| TIM3 | - | Human | - | (125) |

| LAG3 | 3131/3206 | Murine | Immunoimaging | (131) |

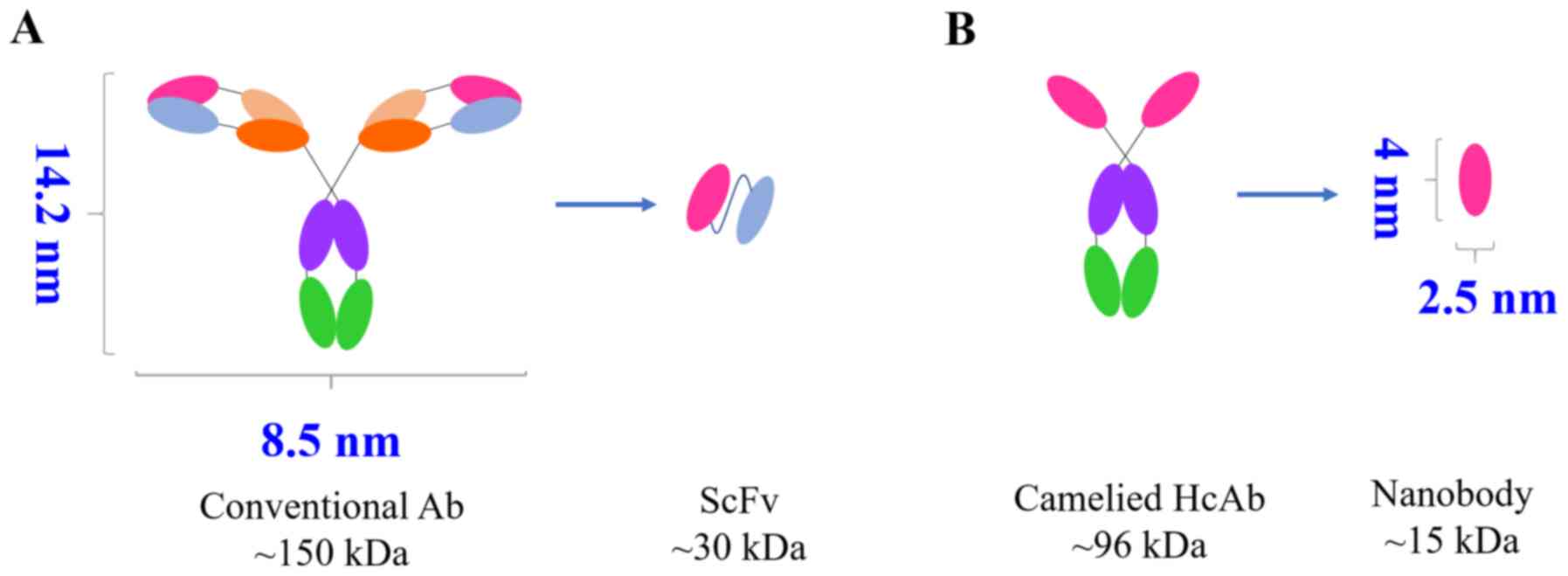

2. Biophysical properties of nanobodies

In 1993, a special antibody was revealed in the

blood of camelids (camel, alpaca, llama) and sharks (33). This antibody is different from the

traditional one with a tetrapeptide chain structure because it

lacks a light chain, thus, it is called a heavy chain antibody. Due

to the absence of the CH1 domain and the light chain, the

antigen-binding region of a heavy chain antibody consists only of

the heavy chain variable region of the heavy chain antibody

(34). For this reason, it is

called single domain antibody (sdAb), or VHH antibody or nanobody

(Fig. 1), and can be obtained

through cloning and expression. The special structure and unique

biological properties of nanobodies have attracted the attention of

numerous scholars, and several research institutions are screening

new nanobodies as new drugs for cancer treatment (35-37) and diagnosis (38).

Small molecular weight and low

immunogenicity

The crystal structure of nanobodies is similar to a

rugby ball with a diameter of approximately 2.5 nm and a length of

approximately 4.2 nm. The relative molecular mass is approximately

15 kDa, which is one-tenth of the size of conventional antibodies.

In fact, it is the smallest antibody with fully functional

properties that currently exists (39-41). Some methods using nanobodies have

better results than conventional antibodies, such as imaging tracer

agents (42-46), microscopic imaging (47), enzyme inhibitors (48,49), and electrochemical biosensors

(50-57). Due to their small size, the

binding region between the nanobody and the epitope forms a

high-density binding, providing a significant advantage in

increasing the sensitivity of the binding signal.

Nanobody backbone regions have more than 80%

sequence homology with human VH regions, and their

three-dimensional structures can overlap. The camel VHH germline

gene sequence is highly homologous to the human VH3 family

sequence. Thus, it has the advantages of weak immunogenicity and

good biocompatibility, and humanizing VHH is relatively simple

(58-61).

High stability

Nanobodies are markedly smaller than traditional

antibodies and they are characterized by the presence of a

disulfide bond, rendering their structure more stable and making

them more resistant to heat and an acid environment (62,63). Under extreme environmental

conditions, such as high temperatures or extreme acid and alkaline

environments, the structure of the traditional polyclonal antibody

changes, exposing its hydrophobic surface; the exposed hydrophobic

molecules aggregate with each other to form large molecules that

precipitate, losing their original function (64). Unlike the traditional antibody,

the nanobody forms different conformational patterns to protect the

stability of amino acids. After chemical and thermal denaturation,

the nanobody refolds and forms a disulfide bond between the

complementarity determination region-1 (CDR1) and CDR3 to improve

the stability of its structure and ensure the stability of its

functional activity (65-68). The stability of nanobodies

establishes them as a potential drug in the treatment of

gastrointestinal diseases, and their excellent characteristics

render them an effictive probe molecule for biosensor applications

(38).

Improved solubility

There are some important differences between the VHH

and the VH of the traditional antibodies. The VH structure of the

conventional antibodies easily form inclusion bodies when expressed

alone, or when the exposed hydrophobic regions adhere to each

other, making the anti-body markedly poor in water solubility. The

four hydrophilic amino acids in FR2 of the nanobodies replace the

hydrophobic amino acids of conventional antibody FR2, such as the

42nd amino acid in the VH of traditional antibodies is often Val,

while in VHH it is often Phe or Tyr. The 49th amino acid in the VH

of the traditional antibodies is often Gly, while in VHH it is

often Glu. The 50th amino acid in the VH of the traditional

antibodies is often Leu, while in VHH it is often Arg or Cys. The

52nd amino acid in the VH of the traditional antibodies is often

Trp, while in VHH it is often Gly. These 4 amino acids in VHH are

hydrophilic, thus rendering the surface of the nanobody more

hydrophilic and increasing its water solubility (40,65,69-72).

High affinity and cavity binding

Similar to traditional VH, VHH includes 4 FRs and 3

CDRs. CDR1 and CDR3 of the VHH are longer than the ones of the VH,

which makes up for the lack of antigen-binding ability caused by

the deletion of the light chains, at least to a certain extent

(40). The cysteine in the VHH

CDR3 also forms disulfide bonds with the cysteine in CDR1 or FR2.

These increased sequences and loop structures expand the area of

antibody-antigen binding and the diversity of antibodies, and

concurrently lead to a markedly stable structure that tolerates

high temperatures and harsh extreme environments (67,70-73). In addition, the nanobody does not

have a traditional Fc segment, thereby avoiding complement

reactions caused by this segment (74).

Conventional Fab fragments and typical ScFv have

concave or planar antigen-binding sites, thus, only surface

antigens can be identified. The nanobody has CDR3 loops that are

generally longer than conventional VH, allowing it to bind to

unconventional epitopes, such as protein clefts and some hidden

epitopes, which are not recognized by traditional anti-bodies

(46,75). Therefore, the nanobody is more

suitable than the ScFv antibody binding site to bind to the

recessed portion of the antigen surface, such as the catalytic

reaction site of the enzyme, thereby blocking its catalytic

activity (70,71,76,77).

Strong tissue penetrability

Nanobodies are small and highly soluble, thus, they

have strong and fast tissue penetration capabilities, and can enter

dense tissues such as solid tumors to play their role (72,78). In addition, nanobodies can

penetrate the blood-brain barrier (71,79,80) and become potential new treatments

for brain diseases such as dementia. Studies have revealed that

camel-derived nanobodies immunize cerebro-vascular endothelial

cells and they can be released on the outer side of vascular

endothelial cells through transcytosis. Their small size allows

better penetration through the tissue- and immune-like synaptic

cell interface. Furthermore, nanobodies are easily filtered by the

glomerulus, and the blood clearing rate is fast so that the excess

of free nanobodies is quickly removed without adversely affecting

the body due to long-term retention. Compared with the shortcoming

of monoclonal anti-bodies, which have poor penetrating power and

are not easily removed, such characteristics are more useful in the

diagnosis of diseases (31,39,46). Currently, several nanobody-based

imaging technologies, such as radionuclides, optics, and

ultra-sound, have been used to visualize target protein expression

levels in multiple types of disease models (31,39).

High expression yields

Nanobodies are markedly simpler in chemical

composition and shape than traditional anti-bodies, which render

nanobodies easily cloned, chemically or genetically modifiable, and

recombinantly produced in various cells (18,40,71,72). It is easier to obtain them from

prokaryotic cells and a soluble expression (81). Recombinant nanobodies are usually

highly expressed in E. coli, reaching 10 mg/l-200 mg/l

(82-84). A biopharmaceutical company

(Ablynx) reported that they greatly increased the production of

nanobodies produced by the yeast reactor to one gram per liter

(85). Nanobodies are easily

genetically manipulated to form monovalent, bivalent, bispecific,

and multivalent anti-bodies, and they can also form fusion proteins

for targeted therapy (31).

Easy modification and functional

modification

Nanobodies are VHH genes cloned from the camel or

alpaca blood by genetic engineering and then expressed by

prokaryotic or eukaryotic cells. Therefore, nanobodies are easily

modified or genetically modified (86). Wang et al (87) added right-handed coiled-coil,

cartilage oligomeric matrix protein, and C4-binding protein to the

C-terminus of the three nanobodies, respectively, and generated

tetramers, pentamers, and heptamers with these added peptides.

Toxins, biotin molecules, and reporter molecules can

also be added to the tail of the nanobody for functional

modification (46,88). In addition, genetic modification

of VHH can transform monovalent nanobodies into various forms, such

as bivalent nanobodies, bispecific nanobodies, and multivalent

nanobodies (89,90).

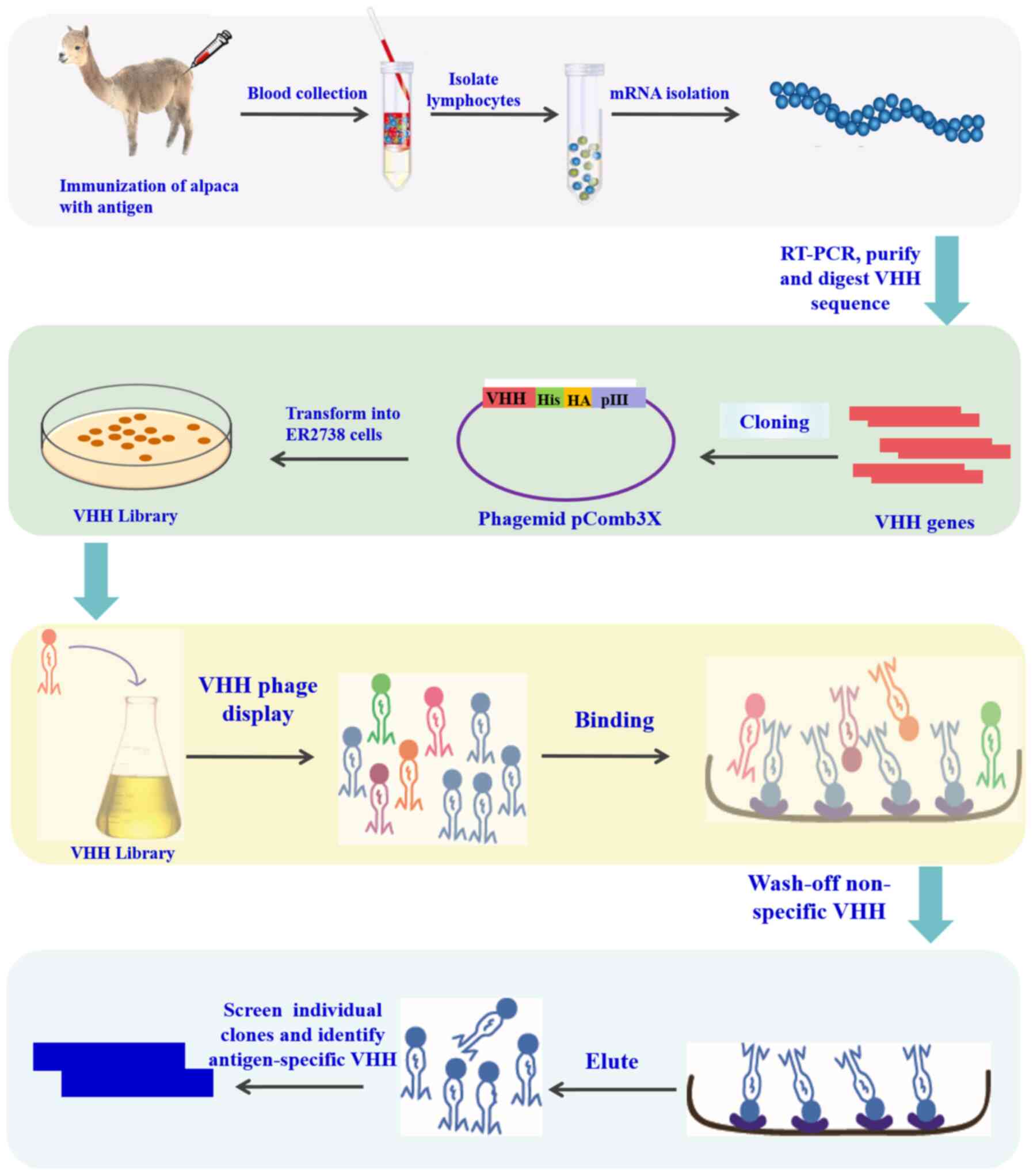

3. Construction of library and panning of

nanobodies

The merits of molecular properties such as affinity

and specificity of nanobodies depend on two factors: The capacity

and diversity of the library. The preparation and screening of

nanobodies are commonly used in a phage display library (40), which contains three library types:

Natural, immune, and synthetic (91,92). The natural library is formed by

amplifying the variable region genes of heavy chain antibodies from

camel peripheral blood mononuclear lymphocytes that have not yet

been immunized, then these variable region genes are recombined

into phagemid vectors, and transformed into host bacteria to form

antibody libraries (93,94). The immune library is an antibody

library obtained by immunizing an alpaca or camel with an antigen

protein, using peripheral blood mononuclear cells of the camel to

amplify the variable region gene of the heavy chain antibody, and

then recombining this variable region gene into a phagemid vector

(94). The capacity of the immune

library is lower than that of natural libraries, but numerous

functional antibodies in the library recognize specific antigens

for immunity, making screening of high-affinity antibodies a

reality. For the construction of synthetic libraries (95), a certain VHH framework (such as

cAbBCIll0) is generally selected as the backbone structure.

Trinucleotide cassettes are used as a unit of raw materials to

generate CDRs sequences. Then, the DNA of each region of VHH is

assembled by PCR to form a complete VHH gene. The gene is cloned

into a phagemid vector and transformed into an E. coli TG1

cell to form a library. The synthetic library, as an artificial

library constructed by genetic engineering technology, has a great

complementary role in the immune libraries and natural libraries

and is an important source for screening high-affinity antibodies,

with significant importance for the development of antibody drugs

(91,95).

The phage display technology is used to screen

binders for various targets from diverse and large libraries and is

widely employed by various research teams. Since the difference

between VHH and VH is mainly due to the absence of the CH1 region,

the work of building an immune and natural library focuses on

isolating antibodies lacking CH1 from IgG, which can be achieved by

one-step (96) or two-step nested

PCR amplification (97). The key

of PCR is to design PCR primers using the conserved nucleotide

sequence of the antibody back-bone region. With regard to the

one-step PCR, the sequence can be amplified from the FR1 to the

hinge region, and restriction sites are introduced on the primers.

For two-step nested PCR, two bands are obtained through the first

step of PCR amplification, and the sizes are 700 and 900 bp,

respectively. Among them, the 700-bp band encodes the VHH-H-CH2

fragment of the heavy chain antibody. This fragment is recovered

using a Gel Extraction kit and used as a template for the second

PCR. The VHH fragment is amplified by the second PCR (98). The amplified antibody sequence is

ligated to the phagemid vector, such as pMECS (95,97), pHEN (99), pAX50 (100), and pComb3 (96,101). The remaining steps are the same

as the ordinary process of constructing an antibody library

(98). The specific protocol is

presented in Fig. 2. In general,

the nanobody library capacity can easily reach 1x108 or

1x109, and diversity is greater than 95%. Furthermore,

because VHH has only one variable region, specific antibodies can

be screened at 1x106. However, in ordinary antibody Fab

or ScFv libraries, the library needs to be large enough to more

easily screen for antibodies (93,96,97,102,103).

In addition to phage display, some other techniques

are applied to screen nanobodies, such as mRNA (104), ribosome (105-107), yeast (108,109) and bacterial surface displays

(110,111). Salema et al (112) reported an E. coli display

system, which combines the advantages of both a phage display and

yeast display system. Flow cytometric analysis of nanobodies on the

surface of E. coli during the screening process can monitor

the selection process in real-time and identify antigen-binding

characteristics.

Nanobodies are generally screened from libraries

using specific immobilized antigens. A specific antigen is coated

in a microtiter plate to specifically bind VHH-displayed phages in

the library, then unbound phages are removed, and the bound phages

are eluted, and are used for further amplification. After several

rounds of panning and enrichment, VHH with high affinity is

obtained, and a positive VHH is identified by indirect ELISA

(98). Or, as an alternative, it

can also be panned in the liquid phase (96). After blocking, binding, elution

and amplification, specific binding between streptavidin-coated

magnetic beads and biotin-labeled antigen can also be used to

obtain antigen-specific antibodies. Cells expressing specific

antigens are similar to protein molecules and can also be used for

nanobody panning (113). The

panning step is the same as the panning step for protein molecules.

To improve the affinity of the antibodies obtained by panning,

during the panning process, the concentration of immobilized

antigen or the number of cells in each panning can be continuously

reduced, and the number of washings can be gradually increased.

4. Nanobodies targeting immune checkpoints

for immunotherapy

The large size of mAbs limits their penetration and

distribution in tumor tissues in certain clinical situations.

Compared to mAbs, the unique structure and biological activity of

the small nanobody molecule make it an effective tool for

successful immunotherapy (60).

CTLA-4

Ipilimumab (10,114-117), a fully human IgG1κ anti-CTLA-4

mAb, was the first immune checkpoint inhibitor against CTLA4

approved for non-small cell lung carcinoma, renal cell carcinoma,

prostate cancer, and metastatic melanoma by the FDA in 2011.

Tremelimumab is another fully human IgG2 anti-CTLA-4 mAb, which is

used in clinical trials (10).

Considering that mAbs have some drawbacks, such as a

markedly poor tissue penetration, production cost and unstable

behavior, Tang et al (118) immunized the camel using the

recombinant human CTLA4 protein, constructed a VHH library and

screened nanobodies using phage display technology. Four

CTLA-4-specific nanobodies were obtained from the repertoire of an

immunized dromedary camel using phage display technology. These

nanobodies recognized unique epitopes of CTLA-4 and exhibited high

binding ability. The Nb16 treatment for melanoma-bearing mice could

reduce tumor growth and prolong their survival time. However, the

study revealed that both the Nb16 and mAb groups have anti-tumor

effects, with no difference between these two groups. Thus, the

antitumor mechanism of Nb16 should be analyzed to facilitate the

clinical application of antibodies.

PD1/PD-L1

The world's first PD-1 inhibitor Opdivo®

was approved for use in 2014. By the end of 2018, the FDA had

approved 6 PD-1/PD-L1 mAbs such as nivolumab (Opdivo®;

Bristol-Myers Squibb), pembrolizumab (Keytruda®; Merck),

and cemiplimab (Libtayo®; Sanofi and Regeneron), and

three PD-L1 inhibitors, such as atezolizumab

(Tecentriq®; Roche), avelumab (Bavencio®;

Pfizer and Merck) and durvalumab (Imfinzi®; AstraZeneca)

(9,10,119). To increase the effectiveness of

immunotherapy, including the immune checkpoint blockade therapy,

miniaturization of antibodies has been introduced. Some

nanobody-based PD1/PD-L1 inhibitors were developed (19).

Broos et al developed a PD-L1 specific sdAb

called K2, which blocks the interaction between PD1 and PD-L1

(120). This property enhances

the ability of dendritic cells to stimulate T-cell activation and

cytokine production. sdAb K2 combined with dendritic cell vaccine

treatment may be more beneficial than PD-L1 mAb against cancer

diseases. The reason that PD-L1 mAbs fail to enhance T-cell

activation may be that they have low efficacy in binding to PD-L1

on DCs, while sdAb K2 has a high ability to bind PD-L1 on both

immune and non-immune cells.

Nanobodies can also be used as a carrier for

cytokines to remodel the tumor microenvironment. In one context,

Fang et al (121)

developed a functional chemokine-VHH fusion protein using a PD-L1

specific nanobody B3 and a model chemo-kine CCL21 to deliver CCL21

to a PD-L1-positive environment and recruit the relevant leukocyte

for improving immunotherapy.

KN035 (122), an

anti-PD-L1 nanobody, was screened using a camel immunological

library. It is the first nanobody research project used in the

field of immunotherapy in the world. Its binding surface of PD-L1

is smaller than other PD-L1 anti-bodies, and its affinity is

similar to other antibodies (3 nm). KN035 can bind the PD-L1

molecule with a high affinity and effectively block the action

between PD-L1 and PD1. Similar to other PD-L1 antibodies, it can

effectively compete for the five hotspot sites where PD-L1 binds to

PD-1. In addition, KN035 can effectively activate PBMCs in

vitro and induce interferon secretion. As an antitumor drug,

its preliminary results regarding its efficacy are favorable.

Xian et al (123) screened anti-PD1 nanobody Nb97 by

phage display, and then Nb97 was used to develop the

Nb97-Nb97-Human serum albumin fusion protein (MY2935), which

exhibited a more efficient blocking effect to that of a humanized

Nb97-Fc (MY2626), and Human serum albumin fusion extended the serum

half-life of nanobody Nb97. Li et al (124) obtained three anti-PDL1

nanobodies from a high quality dromedary camel immune library by

phage display, and analyzed the binding activity and affinity of

the three nanobodies, but did not research the PD1/PDL1 pathway

blocking effect.

TIM3 and LAG3

Some cancer patients do not respond to PD1/PDL1 and

CTLA4 inhibitors. To obtain a greater number of patients benefiting

from immune checkpoint blockade immunotherapy, some other immune

checkpoint molecules have been developed such as TIM3 (125,126) and LAG3 (127,128).

Homayouni et al (129) immunized a six-month Camelus

dromedarius with a human TIM3 protein and developed a novel

anti-human TIM-3 (CD366) nanobody from an immune library. This

nanobody exhibited a high binding capacity to TIM-3, and a high

antiproliferative effect on the acute myeloid leukemia cell line

HL-60 by blocking the galectin/TIM-3 signal, with an inhibitory

effect comparable to or better than that of anti-TIM-3 antibodies.

However, the researchers did not detect the difference in tissue

penetration between nanobodies and mAbs. Ma et al (130) immunized a camel, constructed the

phage display library, and then screened ten anti-TIM3 nanobodies

with high specificity and high affinity using flow cytometry.

However, the researchers did not detect the function of the

anti-TIM3 nanobody, thus, it is not known whether blocking the TIM3

inhibitory signal by anti-TIM3 nanobodies can activate the

antitumor function of T cells. Nevertheless, the aforementioned

studies provide the basis for the development of specific nanobody

drugs blocking TIM-3.

There are seven anti-LAG3 mAbs and two bispecific

anti-bodies targeting LAG3 (131-133), which are at different stages of

clinical development. However, studies on the application of

anti-LAG3 nanobodies in antitumor research have yet to be

published.

5. Nanobodies targeting immune checkpoints

for immunoimaging

Molecular imaging can intuitively detect changes at

the molecular level during and after the treatment of diseases,

therefore it is one of the important methods for evaluating the

effect of tumor therapies. With the continuous development of

targeted therapies, it is becoming increasingly important to

visualize the expression of tumor antigens and the level of immune

infiltrations to predict the course of the treatment. Molecular

imaging based on mAbs has been extensively studied, however the

poor tissue penetration and long half-life severely hinder the

development of successful molecular imaging (60). Nanobody molecular probes bind to

the target with high specificity, and the unbound part is quickly

excreted by the kidney. In addition, nanobody molecular probes have

a deep tumor penetration and high tumor to background ratio soon

after their administration, which clearly reveals the dynamic

changes of target molecules (60,134,135). Therefore, nanobodies have

recently become a powerful tool for in vivo and in

vitro imaging diagnostics.

Imaging of LAG-3

In 2019, Lecocq et al reported an anti-LAG3

nanobody used for noninvasive imaging (136). They immunized alpaca with mouse

LAG3 protein, bio-panned the phage-displayed library, and obtained

nine nanobodies 3132, 3134, 3141, 3204, 3206, 3208, 3209, 3210, and

3366, which exhibited high specificity and high affinity validated

by ELISA, flow cytometry, and surface plasmon resonance methods.

These nanobodies were labeled with Technetium-99m

(99mTc) at the His tail, and then, these nanobodies were

injected into naive C57BL/6 mice intravenously. The results

revealed the nanobody 3132 exhibited specific uptake by LAG3-low

expression immune peripheral organs, such as the spleen and lymph

nodes. To detect whether the nine 99mTc-labeled

nanobodies bind to the tumor overexpressing LAG-3, SPECT/CT imaging

was used to detect the biodistribution of 99mTc-labeled

nanobodies in mice harboring a subcutaneous tumor modified to

overexpress mouse LAG-3. The result revealed that it was possible

to visualize the nanobody uptake using SPECT/CT imaging with high

contrast levels immediately, even 1 h after injection, and this

result was confirmed by flow cytometry and immunohistochemistry.

The results demonstrated that the nanobodies 3132 and 3206 are both

effective diagnostic tools for noninvasively evaluating LAG-3

expression within the tumor environment before and during

immunotherapy.

Imaging of PD1/PDL1

Lv et al developed a nanobody tracer using

the PD-L1 targeted nanobody (Nb109) and the radionuclide 68Ga

through the chelator 1,4,7-triazacyclononane-1,4,7-triac-etic acid

(NOTA), and 68Ga-NOTA-Nb109 exhibited a high affinity for PD-L1

with a KD of 2.9x10-9 M (137). The competitive binding assay

demonstrated a different binding epitope between Nb109 and PD-L1 or

PD1 mAb, suggesting no impact on the tumor uptake of

68Ga-NOTA-Nb109 before and after the treatment with KN035. The

68Ga-NOTA-Nb109 tracer specifically accumulated in mice model

harboring the A375-human PD-L1 tumor, with a maximum uptake of

5.0±0.35% ID/g at 1 h as determined through the PET imaging,

biodistribution, immunohistochemical staining, and autoradiography

assay, indicating that 68Ga-NOTA-Nb109 is a promising nanobody

tracer for noninvasive PET imaging of PD-L1 in the tumor

microenvironment and promising in evaluating the effectiveness of

immune checkpoint blockade immunotherapy in real-time.

In 2017, Broos et al developed an anti-PD-L1

nanobody for noninvasive imaging of the murine PDL1 (138). They immunized 10 million PD-L1

high-expressing mouse macro-phage RAW264.7 cells, and 37 mouse

PD-L1 nanobodies were identified by biopanning of the Nb-phage

display library. Among those Technetium-99m

(99mTc)-labeled nanobodies, four nanobodies were

selected to evaluate their biodistribution in PD-L1-knockout and

wild-type mice using SPECT/CT. According to the results,

Technetium-99m (99mTc)-labeled nanobodies C3 and E2 were

used to image PD-L1 in a synge-neic mouse model because C3 and E2

have high specific antigen binding and beneficial biodistribution.

Their work demonstrated that 99mTc-labeled nanobody

tracers identified PD-L1-expressing tumors, but not in the

PD-L1-knockout tumors, suggesting that these

99mTc-labeled nanobodies can be used in SPECT/CT imaging

to assess the PD-L1 expression markedly soon even one hour after

injection. Owing to the fast tumor-penetrating properties of the

nanobodies, the results confirmed that a 99mTc-labeled

nanobody tracer is a good method to image PD-L1 inhibitory signals

during the treatment of the tumor environment.

In 2019, Broos et al (139) developed another tracer for

noninvasive imaging of the human PDL1. They generated a new panel

of sdAbs by alpaca immunizations, biopanning, and screenings on

recombinant human PD-L1 protein, and they obtained a nanobody

called sdAb K2, which binds to the same epitope on the PD-L1

molecule as the mAb avelumab. Thus, this nanobody is able to block

the PD1/PDL1 inhibitory signal resulting in activated T cells and

enhanced antitumor activity. The nanobody tracer also labeled with

Technetium-99m (99mTc) to develop

99mTc-labeled sdAb K2 tracer, was intravenously injected

into mice bearing melanoma and breast tumors to detect the PD-L1 by

SPECT/CT imaging. This assay revealed a 99mTc-labeled

sdAb K2 tracer with a high signal-to-noise ratio and a strong

ability to image PD-L1. Collectively, sdAb K2 has a dual function

as a diagnostic and therapeutic agent, offering broad prospects in

a variety of tumor immunotherapy and immunoimaging techniques.

Imaging of CTLA4

In 2018, Wan et al reported four

CTLA-4-specific nanobodies from a camel immune library by phage

display technology (140). One

of these nanobodies called Nb36 was conjugated to the carbon

quantum to synthesize a CTLA-4-specific nanobody-fluorescent carbon

quantum dot complex (QDs-Nb36) (141) in 2019 by the same group. Because

anti-CTLA-4 nanobodies specifically bind to CTLA-4+ T

cells and QDs provide a sensitive fluorescent signal for accurate

detection, the QDs-Nb36 complex revealed a high sensitivity

detection of CTLA-4+ T cells by flow cytometry and

immunofluorescence staining. Owing to the small size of the

nanobody, the QDs-Nb36 complex was superior to mAbs in detecting

the positive cells. Thus, nanobody-QDs is a promising method for

the detection of some other biological targets, although this

method cannot monitor the dynamic changes of the target molecule in

real-time.

6. Conclusion

In view of the past few decades, monoclonal

antibodies have shown considerable success in cancer treatment and

diagnosis (44). However, the

large and complex structure of the monoclonal anti-bodies limits

their clinical utility (44). As

revealed in this review, nanobodies have a small molecular weight

conferring them a strong tissue penetration where they bind their

antigens quickly and specifically, while unbound nanobodies can be

quickly cleared through renal excretion, resulting in high

target-to-background signals soon after their administration

(134,135). Therefore, the introduction of

nanobodies has demonstrated that they can overcome certain

shortcomings of monoclonal antibody-based immunotherapy and

immunoimaging.

Currently, nanobodies targeting immune checkpoints

are mainly concentrated in PD1/PDL1. In the future, it is necessary

to develop more research on nanobodies targeting other immune

checkpoints, including TIM3, LAG3, OX40 and VISTA. These immune

checkpoints and their corresponding nanobodies should be

characterized for clinical application. In addition, in order to

prolong the half-life of nanobodies in vivo, nanobody dimers

and multimeric nanobodies have been produced. The moderate relative

molecular mass can better meet the requirements of deep tissue

penetration, targeted aggregation, and blood clearance. With

in-depth research on nanobodies, the application of nanobodies in

tumor immunotherapy and immunodiagnosis is promising.

Funding

The present work was supported by grants from the

National Natural Scientific Foundation of China (grant nos.

81760551 and 82003250), the Guangxi Natural Science Foundation

Project (grant no. 2018GXNSFAA294117), and the Guangxi Medical and

Health Appropriate Technology Development and Application Project

(grant no. S2020005).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

SD and XB conceived and designed this review. GX

and SZ researched and wrote sections 1 and 2 of the present review.

SY researched and wrote section 3 of the present review. YT and HT

researched and wrote section 4 of the present review. KW, HL and KL

researched and wrote sections 5 and 6 of the present review. All

authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to all those

who helped during the writing of this review.

References

|

1

|

Frankel T, Lanfranca MP and Zou W: The

role of tumor micro-environment in cancer immunotherapy. Adv Exp

Med Biol. 1036:51–64. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Fan CA, Reader J and Roque DM: Review of

immune therapies targeting ovarian cancer. Curr Treat Options

Oncol. 19:742018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Marin-Acevedo JA, Soyano AE, Dholaria B,

Knutson KL and Lou Y: Cancer immunotherapy beyond immune checkpoint

inhibitors. J Hematol Oncol. 11:82018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Marin-Acevedo JA, Dholaria B, Soyano AE,

Knutson KL, Chumsri S and Lou Y: Next generation of immune

checkpoint therapy in cancer: New developments and challenges. J

Hematol Oncol. 11:392018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Ok CY and Young KH: Checkpoint inhibitors

in hematological malignancies. J Hematol Oncol. 10:1032017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Baghdadi M, Takeuchi S, Wada H and Seino

K: Blocking mono-clonal antibodies of TIM proteins as orchestrators

of anti-tumor immune response. MAbs. 6:1124–1132. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Rodallec A, Sicard G, Fanciullino R,

Benzekry S, Lacarelle B, Milano G and Ciccolini J: Turning cold

tumors into hot tumors: Harnessing the potential of tumor immunity

using nanoparticles. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 14:1139–1147.

2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Nishino M, Ramaiya NH, Hatabu H and Hodi

FS: Monitoring immune-checkpoint blockade: Response evaluation and

biomarker development. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 14:655–668. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Darvin P, Toor SM, Sasidharan Nair V and

Elkord E: Immune checkpoint inhibitors: Recent progress and

potential biomarkers. Exp Mol Med. 50:1–11. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Hargadon KM, Johnson CE and Williams CJ:

Immune checkpoint blockade therapy for cancer: An overview of

FDA-approved immune checkpoint inhibitors. Int Immunopharmacol.

62:29–39. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Shen H, Yang ES, Conry M, Fiveash J,

Contreras C, Bonner JA and Shi LZ: Predictive biomarkers for immune

checkpoint blockade and opportunities for combination therapies.

Genes Dis. 6:232–246. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Kamath SD, Kalyan A and Benson AB III:

Pembrolizumab for the treatment of gastric cancer. Expert Rev

Anticancer Ther. 18:1177–1187. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Hsu FS, Su CH and Huang KH: A

comprehensive review of US FDA-approved immune checkpoint

inhibitors in urothelial carcinoma. J Immunol Res.

2017:69405462017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Song MK, Park BB and Uhm J: Understanding

immune evasion and therapeutic targeting associated with PD-1/PD-L1

pathway in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Int J Mol Sci.

20:13262019. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

15

|

Michot JM, Bigenwald C, Champiat S,

Collins M, Carbonnel F, Postel-Vinay S, Berdelou A, Varga A,

Bahleda R, Hollebecque A, et al: Immune-related adverse events with

immune checkpoint blockade: A comprehensive review. Eur J Cancer.

54:139–148. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Bannas P, Hambach J and Koch-Nolte F:

Nanobodies and nanobody-based human heavy chain antibodies as

antitumor therapeutics. Front Immunol. 8:16032017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Ubah OC, Buschhaus MJ, Ferguson L,

Kovaleva M, Steven J, Porter AJ and Barelle CJ: Next-generation

flexible formats of VNAR domains expand the drug platform's utility

and developability. Biochem Soc Trans. 46:1559–1565. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Wang H, Meng AM, Li SH and Zhou XL: A

nanobody targeting carcinoembryonic antigen as a promising

molecular probe for non-small cell lung cancer. Mol Med Rep.

16:625–630. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Broos K, Lecocq Q, Raes G, Devoogdt N,

Keyaerts M and Breckpot K: Noninvasive imaging of the PD-1:PD-L1

immune checkpoint: Embracing nuclear medicine for the benefit of

personalized immunotherapy. Theranostics. 8:3559–3570. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Mayer AT, Natarajan A, Gordon SR, Maute

RL, McCracken MN, Ring AM, Weissman IL and Gambhir SS: Practical

immuno-PET radiotracer design considerations for human immune

checkpoint imaging. J Nucl Med. 58:538–546. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

21

|

Natarajan A, Mayer AT, Reeves RE, Nagamine

CM and Gambhir SS: Development of novel ImmunoPET tracers to image

human PD-1 checkpoint expression on tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes

in a humanized mouse model. Mol Imaging Biol. 19:903–914. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Li M, Ehlerding EB, Jiang D, Barnhart TE,

Chen W, Cao T, Engle JW and Cai W: In vivo characterization of

PD-L1 expression in breast cancer by immuno-PET with

89Zr-labeled avelumab. Am J Transl Res. 12:1862–1872.

2020.

|

|

23

|

Kikuchi M, Clump DA, Srivastava RM, Sun L,

Zeng D, Diaz-Perez JA, Anderson CJ, Edwards WB and Ferris RL:

Preclinical immunoPET/CT imaging using Zr-89-labeled anti-PD-L1

monoclonal antibody for assessing radiation-induced PD-L1

upregulation in head and neck cancer and melanoma. Oncoimmunology.

6:e13290712017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Li D, Zou S, Cheng S, Song S, Wang P and

Zhu X: Monitoring the response of PD-L1 expression to epidermal

growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors in nonsmall-cell

lung cancer xenografts by immuno-PET imaging. Mol Pharm.

16:3469–3476. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

González Trotter DE, Meng X, McQuade P,

Rubins D, Klimas M, Zeng Z, Connolly BM, Miller PJ, O'Malley SS,

Lin SA, et al: In vivo imaging of the programmed death ligand 1 by

18F PET. J Nucl Med. 58:1852–1857. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Hettich M, Braun F, Bartholomä MD,

Schirmbeck R and Niedermann G: High-resolution PET imaging with

therapeutic antibody-based PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint tracers.

Theranostics. 6:1629–1640. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Heskamp S, Hobo W, Molkenboer-Kuenen JD,

Olive D, Oyen WJ, Dolstra H and Boerman OC: Noninvasive imaging of

tumor PD-L1 expression using radiolabeled anti-PD-L1 antibodies.

Cancer Res. 75:2928–2936. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Li D, Cheng S, Zou S, Zhu D, Zhu T, Wang P

and Zhu X: Immuno-PET imaging of 89Zr labeled anti-PD-L1

domain anti-body. Mol Pharm. 15:1674–1681. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Josefsson A, Nedrow JR, Park S, Banerjee

SR, Rittenbach A, Jammes F, Tsui B and Sgouros G: Imaging,

biodistribution, and dosimetry of radionuclide-labeled PD-L1

antibody in an immunocompetent mouse model of breast cancer. Cancer

Res. 76:472–479. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

30

|

Natarajan A, Patel CB, Habte F and Gambhir

SS: Dosimetry prediction for clinical translation of

64Cu-pembrolizumab ImmunoPET targeting human PD-1

expression. Sci Rep. 8:6332018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Van Audenhove I and Gettemans J:

Nanobodies as versatile tools to understand, diagnose, visualize

and treat cancer. EBioMedicine. 8:40–48. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Lecocq Q, De Vlaeminck Y, Hanssens H,

D'Huyvetter M, Raes G, Goyvaerts C, Keyaerts M, Devoogdt N and

Breckpot K: Theranostics in immunooncology using nanobody

derivatives. Theranostics. 9:7772–7791. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

33

|

Hamers-Casterman C, Atarhouch T,

Muyldermans S, Robinson G, Hamers C, Songa EB, Bendahman N and

Hamers R: Naturally occurring antibodies devoid of light chains.

Nature. 363:446–448. 1993. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Muyldermans S: Nanobodies: Natural

single-domain antibodies. Annu Rev Biochem. 82:775–797. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Könning D, Zielonka S, Grzeschik J,

Empting M, Valldorf B, Krah S, Schröter C, Sellmann C, Hock B and

Kolmar H: Camelid and shark single domain antibodies: Structural

features and therapeutic potential. Curr Opin Struct Biol.

45:10–16. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Krah S, Schröter C, Zielonka S, Empting M,

Valldorf B and Kolmar H: Single-domain antibodies for biomedical

applications. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 38:21–28. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Steeland S, Vandenbroucke RE and Libert C:

Nanobodies as therapeutics: Big opportunities for small antibodies.

Drug Discov Today. 21:1076–1113. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Stijlemans B, De Baetselier P, Caljon G,

Van Den Abbeele J, Van Ginderachter JA and Magez S: Nanobodies as

tools to understand, diagnose, and treat African trypanosomiasis.

Front Immunol. 8:7242017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Hassanzadeh-Ghassabeh G, Devoogdt N, De

Pauw P, Vincke C and Muyldermans S: Nanobodies and their potential

applications. Nanomedicine (Lond). 8:1013–1026. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Arezumand R, Alibakhshi A, Ranjbari J,

Ramazani A and Muyldermans S: Nanobodies as novel agents for

targeting angio-genesis in solid cancers. Front Immunol.

8:17462017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Van Heeke G, Allosery K, De Brabandere V,

De Smedt T, Detalle L and de Fougerolles A: Nanobodies®

as inhaled biotherapeutics for lung diseases. Pharmacol Ther.

169:47–56. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Massa S, Xavier C, Muyldermans S and

Devoogdt N: Emerging site-specific bioconjugation strategies for

radioimmunotracer development. Expert Opin Drug Deliv.

13:1149–1163. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Massa S, Vikani N, Betti C, Ballet S,

Vanderhaegen S, Steyaert J, Descamps B, Vanhove C, Bunschoten A,

van Leeuwen FW, et al: Sortase A-mediated site-specific labeling of

camelid single-domain antibody-fragments: A versatile strategy for

multiple molecular imaging modalities. Contrast Media Mol Imaging.

11:328–339. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Oliveira S, Heukers R, Sornkom J, Kok RJ,

van Bergen EN and Henegouwen PM: Targeting tumors with nanobodies

for cancer imaging and therapy. J Control Release. 172:607–617.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Iezzi ME, Policastro L, Werbajh S,

Podhajcer O and Canziani GA: Single-domain antibodies and the

promise of modular targeting in cancer imaging and treatment. Front

Immunol. 9:2732018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Hu Y, Liu C and Muyldermans S:

Nanobody-based delivery systems for diagnosis and targeted tumor

therapy. Front Immunol. 8:14422017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Beghein E and Gettemans J: Nanobody

technology: A versatile toolkit for microscopic imaging,

protein-protein interaction analysis, and protein function

exploration. Front Immunol. 8:7712017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Menzel S, Rissiek B, Haag F, Goldbaum FA

and Koch-Nolte F: The art of blocking ADP-ribosyltransferases

(ARTs): Nanobodies as experimental and therapeutic tools to block

mammalian and toxin ARTs. FEBS J. 280:3543–3550. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Unger M, Eichhoff AM, Schumacher L,

Strysio M, Menzel S, Schwan C, Alzogaray V, Zylberman V, Seman M,

Brandner J, et al: Selection of nanobodies that block the

enzy-matic and cytotoxic activities of the binary clostridium

difficile toxin CDT. Sci Rep. 5:78502015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Mars A, Bouhaouala-Zahar B and Raouafi N:

Ultrasensitive sensing of androctonus australis hector scorpion

venom toxins in biological fluids using an electrochemical graphene

quantum dots/nanobody-based platform. Talanta. 190:182–187. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Singh A, Pasha SK, Manickam P and Bhansali

S: Single-domain antibody based thermally stable electrochemical

immunosensor. Biosens Bioelectron. 83:162–168. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Zhu Z, Shi L, Feng H and Zhou HS: Single

domain antibody coated gold nanoparticles as enhancer for

Clostridium difficile toxin detection by electrochemical impedance

immunosensors. Bioelectrochemistry. 101:153–158. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Li G, Zhu M, Ma L, Yan J, Lu X, Shen Y and

Wan Y: Generation of small single domain nanobody binders for

sensitive detection of testosterone by electrochemical impedance

spectroscopy. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 8:13830–13839. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Li H, Sun Y, Elseviers J, Muyldermans S,

Liu S and Wan Y: A nanobody-based electrochemiluminescent

immunosensor for sensitive detection of human procalcitonin.

Analyst. 139:3718–3721. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Liu X, Wen Y, Wang W, Zhao Z, Han Y, Tang

K and Wang D: Nanobody-based electrochemical competitive

immunosensor for the detection of AFB1 through

AFB1-HCR as signal amplifier. Mikrochim Acta.

187:3522020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Liu A, Yin K, Mi L, Ma M, Liu Y, Li Y, Wei

W, Zhang Y and Liu S: A novel photoelectrochemical immunosensor by

integration of nanobody and ZnO nanorods for sensitive detection of

nucleoside diphosphatase kinase-A. Anal Chim Acta. 973:82–90. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Zhou Q, Li G, Zhang Y, Zhu M, Wan Y and

Shen Y: Highly selective and sensitive electrochemical immunoassay

of Cry1C using nanobody and π-π stacked graphene oxide/thionine

assembly. Anal Chem. 88:9830–9836. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Steeland S, Puimège L, Vandenbroucke RE,

Van Hauwermeiren F, Haustraete J, Devoogdt N, Hulpiau P,

Leroux-Roels G, Laukens D, Meuleman P, et al: Generation and

characterization of small single domain antibodies inhibiting human

tumor necrosis factor receptor 1. J Biol Chem. 290:4022–4037. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

59

|

Kazemi-Lomedasht F, Pooshang-Bagheri K,

Habibi-Anbouhi M, Hajizadeh-Safar E, Shahbazzadeh D, Mirzahosseini

H and Behdani M: In vivo immunotherapy of lung cancer using

cross-species reactive vascular endothelial growth factor

nano-bodies. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 20:489–496. 2017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Salvador JP, Vilaplana L and Marco MP:

Nanobody: Outstanding features for diagnostic and therapeutic

applications. Anal Bioanal Chem. 411:1703–1713. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

De Munter S, Van Parys A, Bral L, Ingels

J, Goetgeluk G, Bonte S, Pille M, Billiet L, Weening K, Verhee A,

et al: Rapid and effective generation of nanobody based CARs using

PCR and gibson assembly. Int J Mol Sci. 21:8832020. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

62

|

Ren W, Li Z, Xu Y, Wan D, Barnych B, Li Y,

Tu Z, He Q, Fu J and Hammock BD: One-step ultrasensitive

bioluminescent enzyme immunoassay based on nanobody/nanoluciferase

fusion for detection of aflatoxin B1 in cereal. J Agric

Food Chem. 67:5221–5229. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Allegra A, Innao V, Gerace D, Vaddinelli

D, Allegra AG and Musolino C: Nanobodies and cancer: Current status

and new perspectives. Cancer Invest. 36:221–237. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

De Genst E, Chan PH, Pardon E, Hsu SD,

Kumita JR, Christodoulou J, Menzer L, Chirgadze DY, Robinson CV,

Muyldermans S, et al: A nanobody binding to non-amyloido-genic

regions of the protein human lysozyme enhances partial unfolding

but inhibits amyloid fibril formation. J Phys Chem B.

117:13245–13258. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Gonzalez-Sapienza G, Rossotti MA and

Tabares-da Rosa S: Single-domain antibodies as versatile affinity

reagents for analytical and diagnostic applications. Front Immunol.

8:9772017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Akazawa-Ogawa Y, Uegaki K and Hagihara Y:

The role of intra-domain disulfide bonds in heat-induced

irreversible denaturation of camelid single domain VHH antibodies.

J Biochem. 159:111–121. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

67

|

Goldman ER, Liu JL, Zabetakis D and

Anderson GP: Enhancing stability of camelid and shark single domain

antibodies: An overview. Front Immunol. 8:8652017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Kunz P, Zinner K, Mücke N, Bartoschik T,

Muyldermans S and Hoheisel JD: The structural basis of nanobody

unfolding reversibility and thermoresistance. Sci Rep. 8:79342018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Schumacher D, Helma J, Schneider AFL,

Leonhardt H and Hackenberger CPR: Nanobodies: Chemical

functionalization strategies and intracellular applications. Angew

Chem Int Ed Engl. 57:2314–2333. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

70

|

Wang Y, Fan Z, Shao L, Kong X, Hou X, Tian

D, Sun Y, Xiao Y and Yu L: Nanobody-derived nanobiotechnology tool

kits for diverse biomedical and biotechnology applications. Int J

Nanomedicine. 11:3287–3303. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Jovčevska I and Muyldermans S: The

therapeutic potential of nanobodies. BioDrugs. 34:11–26. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

72

|

Zottel A, Jovčevska I, Šamec N, Mlakar J,

Šribar J, Križaj I, Skoblar Vidmar M and Komel R: Anti-vimentin,

anti-TUFM, anti-NAP1L1 and anti-DPYSL2 nanobodies display cytotoxic

effect and reduce glioblastoma cell migration. Ther Adv Med Oncol.

12:17588359209153022020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Peyron I, Kizlik-Masson C, Dubois MD,

Atsou S, Ferrière S, Denis CV, Lenting PJ, Casari C and Christophe

OD: Camelid-derived single-chain antibodies in hemostasis:

Mechanistic, diagnostic, and therapeutic applications. Res Pract

Thromb Haemost. 4:1087–1110. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Kijanka M, Dorresteijn B, Oliveira S and

van Bergen en Henegouwen PM: Nanobody-based cancer therapy of solid

tumors. Nanomedicine (Lond). 10:161–174. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

75

|

Huen J, Yan Z, Iwashkiw J, Dubey S,

Gimenez MC, Ortiz ME, Patel SV, Jones MD, Riazi A, Terebiznik M, et

al: A novel single domain antibody targeting FliC flagellin of

salmonella enterica for effective inhibition of host cell invasion.

Front Microbiol. 10:26652019. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

76

|

Zavrtanik U, Lukan J, Loris R, Lah J and

Hadži S: Structural basis of epitope recognition by heavy-chain

camelid antibodies. J Mol Biol. 430:4369–4368. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Lauwereys M, Arbabi Ghahroudi M, Desmyter

A, Kinne J, Hölzer W, De Genst E, Wyns L and Muyldermans S: Potent

enzyme inhibitors derived from dromedary heavy-chain anti-bodies.

EMBO J. 17:3512–3520. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Arbabi-Ghahroudi M: Camelid single-domain

antibodies: Historical perspective and future outlook. Front

Immunol. 8:15892017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Muruganandam A, Tanha J, Narang S and

Stanimirovic D: Selection of phage-displayed llama single-domain

antibodies that transmigrate across human blood-brain barrier

endothelium. FASEB J. 16:240–242. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Abulrob A, Sprong H, Van Bergen en

Henegouwen P and Stanimirovic D: The blood-brain barrier

transmigrating single domain antibody: Mechanisms of transport and

antigenic epitopes in human brain endothelial cells. J Neurochem.

95:1201–1214. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Menzel S, Schwarz N, Haag F and Koch-Nolte

F: Nanobody-based biologics for modulating purinergic signaling in

inflammation and immunity. Front Pharmacol. 9:2662018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Zhu M, Hu Y, Li G, Ou W, Mao P, Xin S and

Wan Y: Combining magnetic nanoparticle with biotinylated nanobodies

for rapid and sensitive detection of influenza H3N2. Nanoscale Res

Lett. 9:5282014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Zarschler K, Witecy S, Kapplusch F,

Foerster C and Stephan H: High-yield production of functional

soluble single-domain antibodies in the cytoplasm of Escherichia

coli. Microb Cell Fact. 12:972013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

He T, Zhu J, Nie Y, Hu R, Wang T, Li P,

Zhang Q and Yang Y: Nanobody technology for mycotoxin detection in

the field of food safety: Current status and prospects. Toxins

(Basel). 10:1802018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

85

|

Detalle L, Stohr T, Palomo C, Piedra PA,

Gilbert BE, Mas V, Millar A, Power UF, Stortelers C, Allosery K, et

al: Generation and characterization of ALX-0171, a potent novel

therapeutic nanobody for the treatment of respiratory syncytial

virus infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 60:6–13. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Sheng Y, Wang K, Lu Q, Ji P, Liu B, Zhu J,

Liu Q, Sun Y, Zhang J, Zhou EM and Zhao Q: Nanobody-horseradish

peroxidase fusion protein as an ultrasensitive probe to detect

antibodies against newcastle disease virus in the immunoassay. J

Nanobiotechnology. 17:352019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Wang L, Liu X, Zhu X, Wang L, Wang W, Liu

C, Cui H, Sun M and Gao B: Generation of single-domain antibody

multimers with three different self-associating peptides. Protein

Eng Des Sel. 26:417–423. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Behdani M, Zeinali S, Karimipour M,

Khanahmad H, Schoonooghe S, Aslemarz A, Seyed N, Moazami-Godarzi R,

Baniahmad F, Habibi-Anbouhi M, et al: Development of

VEGFR2-specific nanobody pseudomonas exotoxin A conjugated to

provide efficient inhibition of tumor cell growth. N Biotechnol.

30:205–209. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

89

|

Sadeghnezhad G, Romão E, Bernedo-Navarro

R, Massa S, Khajeh K, Muyldermans S and Hassania S: Identification

of new DR5 agonistic nanobodies and generation of multivalent

nanobody constructs for cancer treatment. Int J Mol Sci.

20:48182019. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

90

|

Huet HA, Growney JD, Johnson JA, Li J,

Bilic S, Ostrom L, Zafari M, Kowal C, Yang G, Royo A, et al:

Multivalent nano-bodies targeting death receptor 5 elicit superior

tumor cell killing through efficient caspase induction. Mabs.

6:1560–1570. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

91

|

Liu W, Song H, Chen Q, Yu J, Xian M, Nian

R and Feng D: Recent advances in the selection and identification

of antigen-specific nanobodies. Mol Immunol. 96:37–47. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Wagner HJ, Wehrle S, Weiss E, Cavallari M

and Weber W: A two-step approach for the design and generation of

nanobodies. Int J Mol Sci. 19:34442018. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

93

|

Yan J, Wang P, Zhu M, Li G, Romão E, Xiong

S and Wan Y: Characterization and applications of nanobodies

against human procalcitonin selected from a novel naïve Nanobody

phage display library. J Nanobiotechnology. 13:332015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

94

|

Itoh K, Reis AH, Hayhurst A and Sokol SY:

Isolation of nanobodies against xenopus embryonic antigens using

immune and nonimmune phage display libraries. PLoS One.

14:e02160832019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

95

|

Yan J, Li G, Hu Y, Ou W and Wan Y:

Construction of a synthetic phage-displayed Nanobody library with

CDR3 regions randomized by trinucleotide cassettes for diagnostic

applications. J Transl Med. 12:3432014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Cui Y, Li D, Morisseau C, Dong JX, Yang J,

Wan D, Rossotti MA, Gee SJ, González-Sapienza GG and Hammock BD:

Heavy chain single-domain antibodies to detect native human soluble

epoxide hydrolase. Anal Bioanal Chem. 407:7275–7283. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Gong X, Zhu M, Li G, Lu X and Wan Y:

Specific determination of influenza H7N2 virus based on

biotinylated single-domain antibody from a phage-displayed library.

Anal Biochem. 500:66–72. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

98

|

Vincke C, Gutiérrez C, Wernery U, Devoogdt

N, Hassanzadeh-Ghassabeh G and Muyldermans S: Generation of single

domain antibody fragments derived from camelids and generation of

manifold constructs. Methods Mol Biol. 907:145–176. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Behar G, Sibéril S, Groulet A, Chames P,

Pugnière M, Boix C, Sautès-Fridman C, Teillaud JL and Baty D:

Isolation and characterization of anti-FcgammaRIII (CD16) llama

single-domain antibodies that activate natural killer cells.

Protein Eng Des Sel. 21:1–10. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

100

|

Maussang D, Mujić-Delić A, Descamps FJ,

Stortelers C, Vanlandschoot P, Stigter-van Walsum M, Vischer HF,

van Roy M, Vosjan M, Gonzalez-Pajuelo M, et al: Llama-derived

single variable domains (nanobodies) directed against chemokine

receptor CXCR7 reduce head and neck cancer cell growth in vivo. J

Biol Chem. 288:29562–29572. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

101

|

Farajpour Z, Rahbarizadeh F, Kazemi B and

Ahmadvand D: A nanobody directed to a functional epitope on VEGF,

as a novel strategy for cancer treatment. Biochem Biophys Res

Commun. 446:132–136. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

102

|

Kim HJ, McCoy MR, Majkova Z, Dechant JE,

Gee SJ, Tabares-da Rosa S, González-Sapienza GG and Hammock BD:

Isolation of alpaca anti-hapten heavy chain single domain

antibodies for development of sensitive immunoassay. Anal Chem.

84:1165–1171. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

103

|

Li K, Zettlitz KA, Lipianskaya J, Zhou Y,

Marks JD, Mallick P, Reiter RE and Wu AM: A fully human scFv phage

display library for rapid antibody fragment reformatting. Protein

Eng Des Sel. 28:307–316. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

104

|

Doshi R, Chen BR, Vibat CR, Huang N, Lee

CW and Chang G: In vitro nanobody discovery for integral membrane

protein targets. Sci Rep. 4:67602014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

105

|

Ferrari D, Garrapa V, Locatelli M and

Bolchi A: A novel nanobody scaffold optimized for bacterial

expression and suitable for the construction of ribosome display

libraries. Mol Biotechnol. 62:43–55. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

106

|

Yau KY, Groves MA, Li S, Sheedy C, Lee H,

Tanha J, MacKenzie CR, Jermutus L and Hall JC: Selection of

hapten-specific single-domain antibodies from a non-immunized llama

ribosome display library. J Immunol Methods. 281:161–175. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

107

|

Bencurova E, Pulzova L, Flachbartova Z and

Bhide M: A rapid and simple pipeline for synthesis of

mRNA-ribosome-V(H)H complexes used in single-domain antibody

ribosome display. Mol Biosyst. 11:1515–1524. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

108

|

McMahon C, Baier AS, Pascolutti R,

Wegrecki M, Zheng S, Ong JX, Erlandson SC, Hilger D, Rasmussen SGF,

Ring AM, et al: Yeast surface display platform for rapid discovery

of conformationally selective nanobodies. Nat Struct Mol Biol.

25:289–296. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

109

|

Uchański T, Zögg T, Yin J, Yuan D,

Wohlkönig A, Fischer B, Rosenbaum DM, Kobilka BK, Pardon E and

Steyaert J: An improved yeast surface display platform for the

screening of nanobody immune libraries. Sci Rep. 9:3822019.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

110

|

Salema V and Fernández LÁ: Escherichia

coli surface display for the selection of nanobodies. Microb

Biotechnol. 10:1468–1484. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

111

|

Salema V, Marín E, Martínez-Arteaga R,

Ruano-Gallego D, Fraile S, Margolles Y, Teira X, Gutierrez C,

Bodelón G and Fernández LÁ: Selection of single domain antibodies

from immune libraries displayed on the surface of E. coli cells

with two β-domains of opposite topologies. PLoS One. 8:e751262013.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

112

|

Salema V, Mañas C, Cerdán L, Piñero-Lambea

C, Marín E, Roovers RC, Van Bergen En Henegouwen PM and Fernández

LÁ: High affinity nanobodies against human epidermal growth factor

receptor selected on cells by E. coli display. MAbs. 8:1286–1301.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

113

|

Tang J, Li J, Zhu X, Yu Y, Chen D, Yuan L,

Gu Z, Zhang X, Qi L, Gong Z, et al: Novel CD7-specific

nanobody-based immunotoxins potently enhanced apoptosis of

CD7-positive malignant cells. Oncotarget. 7:34070–34083. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

114

|

Hassel JC, Heinzerling L, Aberle J, Bähr

O, Eigentler TK, Grimm MO, Grünwald V, Leipe J, Reinmuth N, Tietze

JK, et al: Combined immune checkpoint blockade

(anti-PD-1/anti-CTLA-4): Evaluation and management of adverse drug

reactions. Cancer Treat Rev. 57:36–49. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

115

|

Gupta A, De Felice KM, Loftus EV Jr and

Khanna S: Systematic review: Colitis associated with anti-CTLA-4

therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 42:406–417. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

116

|

Savoia P, Astrua C and Fava P: Ipilimumab

(Anti-Ctla-4 Mab) in the treatment of metastatic melanoma:

Effectiveness and toxicity management. Hum Vaccin Immunother.

12:1092–1101. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

117

|

Gao X and McDermott DF: Ipilimumab in

combination with nivolumab for the treatment of renal cell

carcinoma. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 18:947–957. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

118

|

Tang Z, Mo F, Liu A, Duan S, Yang X, Liang

L, Hou X, Yin S, Jiang X, Vasylieva N, et al: A nanobody against

cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated antigen-4 increases the

anti-tumor effects of specific CD8+ T cells. J Biomed

Nanotechnol. 15:2229–2239. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

119

|

Mahoney KM, Freeman GJ and McDermott DF:

The next immune-checkpoint inhibitors: PD-1/PD-L1 blockade in

melanoma. Clin Ther. 37:764–782. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

120

|

Broos K, Lecocq Q, Keersmaecker B, Raes G,

Corthals J, Lion E, Thielemans K, Devoogdt N, Keyaerts M and

Breckpot K: Single domain antibody-mediated blockade of programmed

death-ligand 1 on dendritic cells enhances CD8 T-cell activation

and cytokine production. Vaccines (Basel). 7:852019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

121

|

Fang T, Li R, Li Z, Cho J, Guzman JS, Kamm

RD and Ploegh HL: Remodeling of the tumor microenvironment by a

chemokine/Anti-PD-L1 nanobody fusion protein. Mol Pharm.

16:2838–2844. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

122

|

Zhang F, Wei H, Wang X, Bai Y, Wang P, Wu

J, Jiang X, Wang Y, Cai H, Xu T and Zhou A: Structural basis of a

novel PD-L1 nanobody for immune checkpoint blockade. Cell Discov.

3:170042017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

123

|

Xian Z, Ma L, Zhu M, Li G, Gai J, Chang Q,

Huang Y, Ju D and Wan Y: Blocking the PD-1-PD-L1 axis by a novel

PD-1 specific nanobody expressed in yeast as a potential

therapeutic for immunotherapy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun.

519:267–273. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

124

|

Li S, Jiang K, Wang T, Zhang W, Shi M,

Chen B and Hua Z: Nanobody against PDL1. Biotechnol Lett.

42:727–736. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

125

|

Liu J, Zhang S, Hu Y, Yang Z, Li J, Liu X,

Deng L, Wang Y, Zhang X, Jiang T and Lu X: Targeting PD-1 and Tim-3

path-ways to reverse CD8 T-cell exhaustion and enhance ex vivo

T-cell responses to autologous dendritic/tumor vaccines. J

Immunother. 39:171–180. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

126

|

Liu JF, Ma SR, Mao L, Bu LL, Yu GT, Li YC,

Huang CF, Deng WW, Kulkarni AB, Zhang WF and Sun ZJ: T-cell

immu-noglobulin mucin 3 blockade drives an antitumor immune

response in head and neck cancer. Mol Oncol. 11:235–247. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

127

|

Chang X, Lu X, Guo J and Teng GJ:

Interventional therapy combined with immune checkpoint inhibitors:

Emerging opportunities for cancer treatment in the era of

immunotherapy. Cancer Treat Rev. 74:49–60. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

128

|

Ascione A, Arenaccio C, Mallano A, Flego

M, Gellini M, Andreotti M, Fenwick C, Pantaleo G, Vella S and

Federico M: Development of a novel human phage display-derived

anti-LAG3 scFv antibody targeting CD8+ T lymphocyte

exhaustion. BMC Biotechnol. 19:672019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

129

|

Homayouni V, Ganjalikhani-Hakemi M, Rezaei

A, Khanahmad H, Behdani M and Lomedasht FK: Preparation and

characterization of a novel nanobody against T-cell immunoglobulin

and mucin-3 (TIM-3). Iran J Basic Med Sci. 19:1201–1208.

2016.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

130

|

Ma LL, Zhu M, Li GH, Li YF, Gai JW and Wan

YK: Construction and screening of phage display library for TIM-3

nanobody. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica. 53:388–395. 2018.

|

|

131

|

Long L, Zhang X, Chen F, Pan Q,

Phiphatwatchara P, Zeng Y and Chen H: The promising immune

checkpoint LAG-3: From tumor microenvironment to cancer

immunotherapy. Genes Cancer. 9:176–189. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

132

|

Everett KL, Kraman M, Wollerton FPG,

Zimarino C, Kmiecik K, Gaspar M, Pechouckova S, Allen NL, Doody JF

and Tuna M: Generation of Fcabs targeting human and murine LAG-3 as

building blocks for novel bispecific antibody therapeutics.

Methods. 154:60–69. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

133

|

Puhr HC and Ilhan-Mutlu A: New emerging

targets in cancer immunotherapy: The role of LAG3. ESMO Open.

4:e0004822019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

134

|

Dmitriev OY, Lutsenko S and Muyldermans S:

Nanobodies as probes for protein dynamics in vitro and in cells. J

Biol Chem. 291:3767–3775. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

135

|

Chanier T and Chames P: Nanobody

engineering: Toward next generation immunotherapies and

immunoimaging of cancer. Antibodies (Basel). 8:132019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

136

|

Lecocq Q, Zeven K, De Vlaeminck Y, Martens

S, Massa S, Goyvaerts C, Raes G, Keyaerts M, Breckpot K and

Devoogdt N: Noninvasive imaging of the immune checkpoint LAG-3

using nanobodies, from development to pre-clinical use.

Biomolecules. 9:5482019. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

137

|

Lv G, Sun X, Qiu L, Sun Y, Li K, Liu Q,

Zhao Q, Qin S and Lin J: PET imaging of tumor PD-L1 expression with

a highly specific nonblocking single-domain antibody. J Nucl Med.

61:117–122. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

138

|

Broos K, Keyaerts M, Lecocq Q, Renmans D,

Nguyen T, Escors D, Liston A, Raes G, Breckpot K and Devoogdt N:

Non-invasive assessment of murine PD-L1 levels in syngeneic tumor

models by nuclear imaging with nanobody tracers. Oncotarget.

8:41932–41946. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

139

|