1. Introduction

Genitourinary and gynecological cancers are a wide

group of cancers with differences in etiology, rapidity of

progression and treatment strategies (1-7).

Among these, prostate and cervical cancers (CCs) are associated

with high incidence and mortality rates worldwide (8). The common feature of the majority

of defined tumors is a lack of characteristic symptoms in the early

stages, which often leads to a diagnosis of invasive or metastatic

disease and treatment difficulties (1,3,9,10). Therefore, novel prognostic and

predictive clinical and molecular targets for modern drugs are

required to improve the therapeutic process.

The Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) signaling pathway is an

evolutionary conserved molecular cascade discovered by

Nusslein-Volhard and Wieschaus during their studies on D.

melanogaster body segmentation (11). Further research has revealed that

this signaling plays an important role in human embryonic

development, as well as in maintaining the homeostasis of organisms

in postnatal life (12-14). The canonical signaling pathway

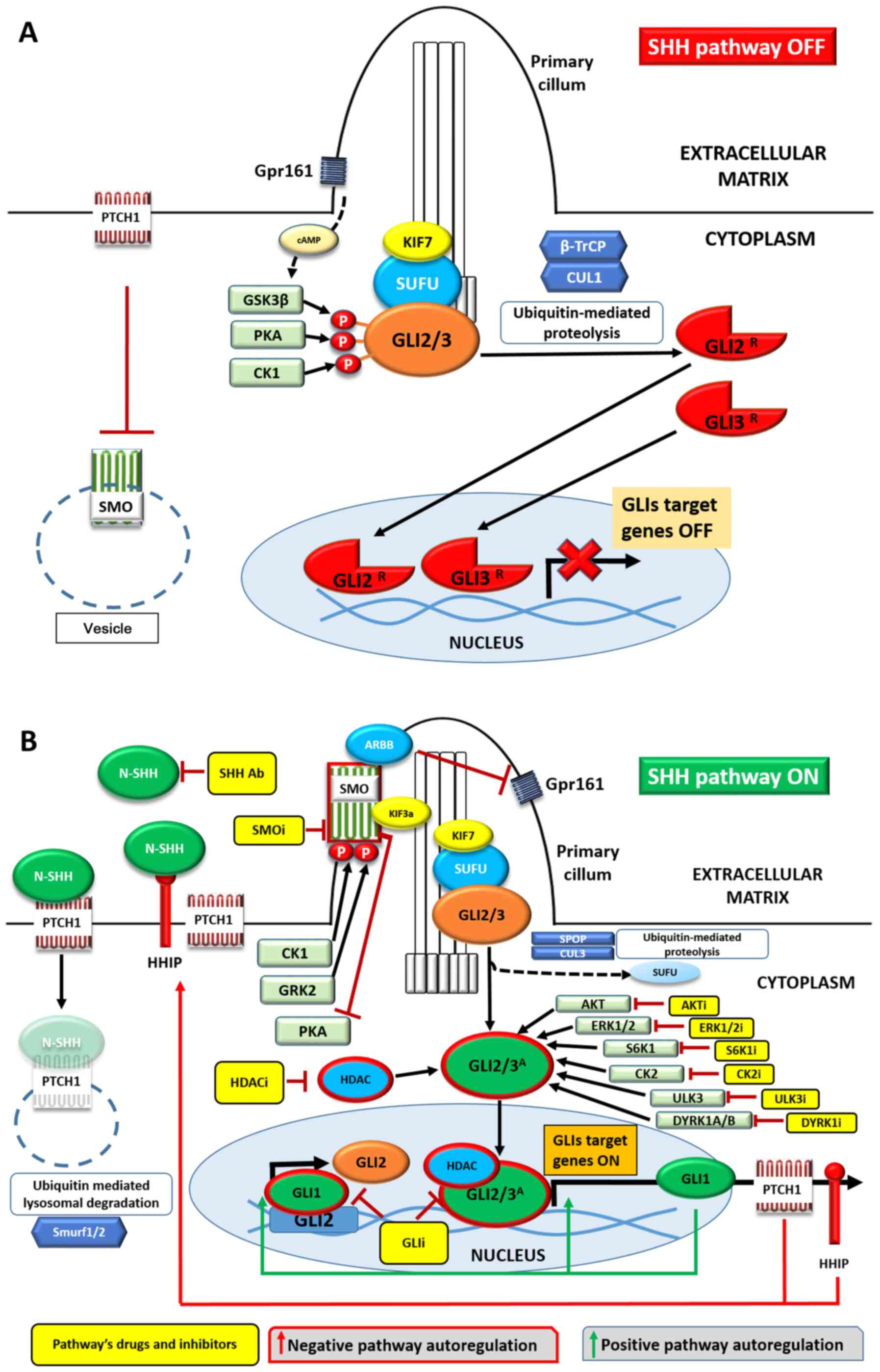

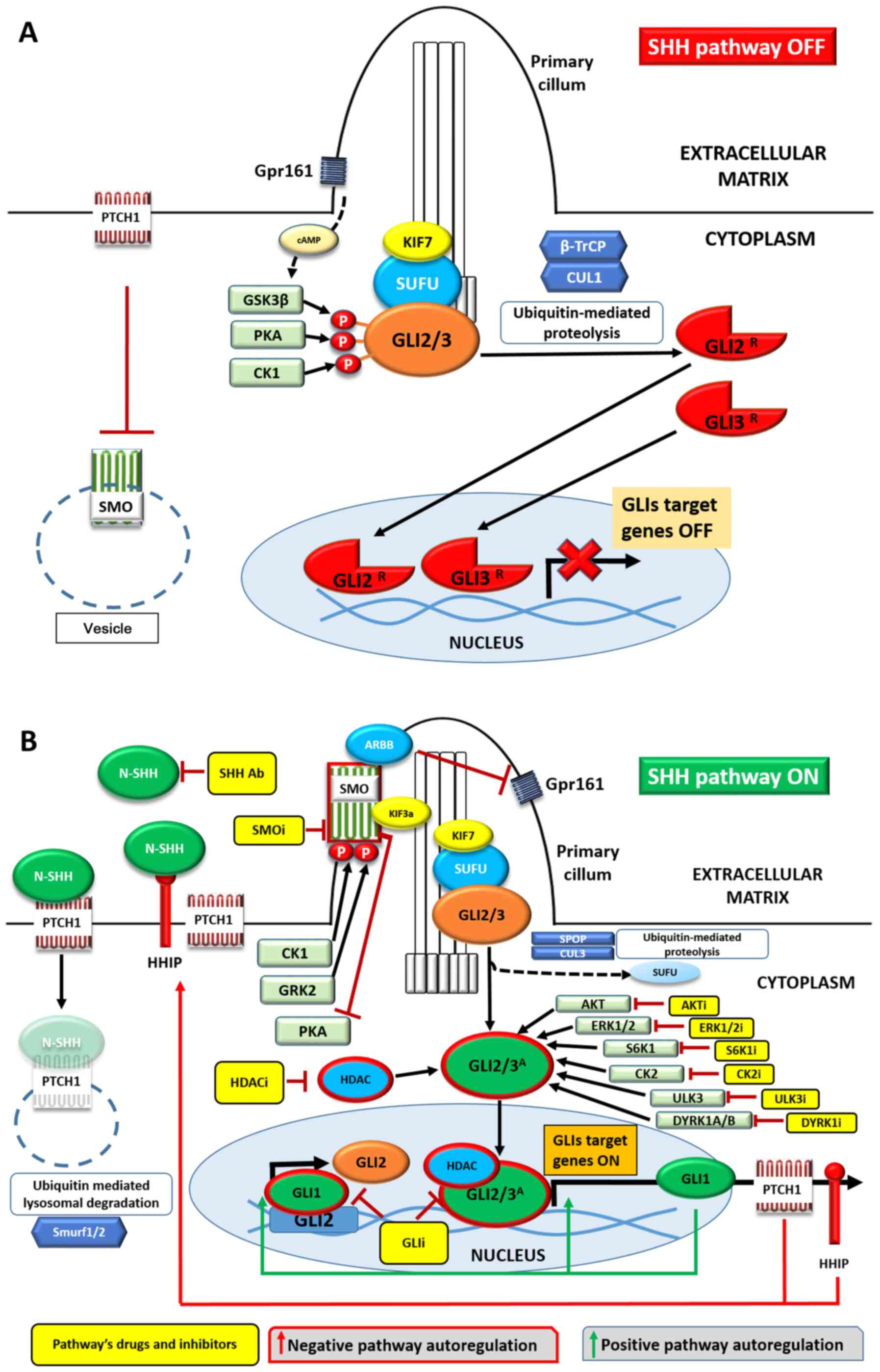

includes several proteins involved in signal transmission from the

cell membrane to the nucleus (Fig.

1) (15). The activity of

the pathway is regulated by the SHH signaling ligand, which can

bind to patched 1 (PTCH1) receptor (16). This interaction results in the

translocation of smoothened, frizzled class receptor (SMO)

(17) from the cytoplasm to the

cell membrane in the region of the primary cilium (18). The single non-motile cell

protrusion can be found in almost all cell types. The core of the

primary cilium is composed of nine microtubule doublets, without

central microtubule pairs and dynein arms, which are found in the

motile cilia (19). The ciliary

localization of SMO promotes intracellular signal transmission to

the cytoplasm, protein complex composed of SUFU negative regulator

of hedgehog signaling (SUFU) protein and GLI family zinc finger 2

and 3 (GLI2/3) transcription factors (20). Consequently, SUFU undergoes

proteolytic degradation and GLIs (the SHH pathway effectors)

translocate to the cell nucleus and act as transcription factors

for various target genes involved in cell survival (i.e.,

BCL2), proliferation [cyclin D (CCND1) and MYC

proto-oncogene, bHLH transcription factor (MYC)] (15), epithelial-mesenchymal transition

[snail family transcriptional repressor 1 (Snail)] and

angiogenesis (vascular endothelial growth factor A), or genes that

regulate SHH signaling, such as GLI1 (positive feedback

loop) and PTCH1 (negative feedback loop) (21). The upregulation of SHH pathway

components and, particularly GLI transcription factors, is

frequently associated with the progression of various types of

cancer, including retinoblastoma, breast, colorectal and non-small

cell lung cancer (22,27), acute myeloid leukemia (AML), as

well as basal cell carcinoma (BCC) (28,29). Drugs that inhibit SMO have been

introduced for BCC and AML and tested in other malignancies;

however, since GLI activation may occur in an SMO-independent

manner, drug resistance occurs frequently during treatment

(17,30). To date, no SHH pathway-targeted

drugs have been introduced for the treatment of gynecological or

genitourinary tract cancers, at least to the best of our knowledge.

The present review includes a comprehensive description of SHH

signaling components and their role as potential molecular targets,

which may prove useful for the treatment of genitourinary and

gynecological cancers. The present review also aimed to discuss the

upstream regulation of the SHH pathway, as well as its

correspondence with other cellular pathways, which may support the

introduction of a combination of drugs targeting different

tumor-related pathways.

| Figure 1Overview of the SHH pathway in the

(A) absence or (B) presence of the SHH ligand. Negative signaling

regulators are presented in red and positive regulators in green.

Transmembrane proteins are shown as rods or trails, SHH pathway

elements and proteins forming complexes with them as ovals, kinases

as rectangles and proteolytic proteins as hexagons. Yellow

rectangles represent drugs inhibiting/blocking the specific

cellular components. Activated proteins are surrounded by red

borders. See main text for details. Ab, antibody; i, inhibitor;

SHH, Sonic Hedgehog; PITCH1, pitched 1; SMO, smoothened, frizzled

class receptor; Gpr161, G protein-coupled receptor 161; GSK-3β,

glycogen synthase kinase 3β; PKA, protein kinase A; KIF7, kinesin

family member 7 motor protein; CUL1, β-TrCP, β transducin

repeat-containing protein; cullin 1; GRK2, G protein-coupled

receptor kinase 2; HDAC, histone deacetylase. |

2. Mammalian Sonic Hedgehog canonical

pathway

Sonic hedgehog signaling molecule

SHH signaling transfers signals from the

extracellular environment and activates the expression of genes

involved in cell survival and proliferation (28). A schematic presentation of the

pathway is shown in Fig. 1A and

B, and the core elements of the pathway are briefly presented

in Table I.

| Table IMain components of the Sonic Hedgehog

pathway in mammals. |

Table I

Main components of the Sonic Hedgehog

pathway in mammals.

| Mammalian gene | Protein, full name

(aliases) | Post-translational

protein modifications (Refs.) | Protein function

(Refs.) |

|---|

| SHH | SHH, Sonic Hedgehog

signaling molecule | Autocatalytic

cleavage into C-SHH and N-SHH Addition of cholesterol and palmitic

acid moiety to N-SHH (39-42) | Upstream, positive

regulator of SHH signaling; ligand for PTCH1 receptor (16,20,46) |

| PTCH1 | PTCH, patched 1

(PTC, BCNS, PTC1) | Conformational

changes of protein to enable binding of N-palmitoyled residue of

SHH ligand (48) | Receptor for SHH

protein; negative SHH signaling regulator; suppress the activity of

SMO protein (20,45) |

| SMO | SMO, smoothened,

frizzled class receptor (Gx, CRJS, SMOH) | Phosphorylation by

PKA, GSK3β and CK1 Translocation into primary cilia with ARBB

(18,59) | Atypical G-coupled

receptor; positive, SHH pathway signal carrier (17,55) |

| GLI1 | GLI1, GLI family

zinc finger 1 (GLI, PPD1) | Translocation into

primary cilia (21) Dissociation

from SUFU (21) GLI2 and GLI3

proteolytic truncation | Downstream effector

of SHH signaling; zinc-finger transcriptional activator (20,21,70) |

| GLI2 | GLI2, GLI family

zinc finger 2 (CJS; HPE9) | suppression

(70) Phosphorylation,

ubiquitination, sumoylation, acetylation, deacetylation (70) | Downstream effector

of SHH signaling; zinc-finger transcriptional activator/repressor

(20,21,70) |

| GLI3 | GLI3, GLI family

zinc finger 3 | | Downstream effector

of SHH signaling; zinc-finger transcriptional activator/repressor

(20,21,70) |

SHH signaling is triggered by the cell membrane

binding of the functional SHH glycoprotein. It acts as a classic

morphogen during embryonic development, where it is involved in the

crucial phases, such as patterning of the ventral neural tube, the

anterior-posterior limb axis and ventral somites (20). Germinal mutations of the

SHH gene, located at 7q36.3, lead to congenital defects,

such as holoprosencephaly (31-33). Recent research on genomic DNA of

patients affected by holoprosencephaly has revealed that eight

synonymous single-nucleotide variants in the SHH gene are

associated with a reduced level of SHH protein (34). A recent in vivo study on

Cre-modified mice demonstrated that SHH expression was also

crucial for proper fetal development of the tongue and mandible

(35). SHH is the most

well-known among other hedgehog family proteins, comprising Desert

Hedgehog (DHH) and Indian hedgehog (IHH) molecules (36). Although all hedgehog family

members can bind to the PTCH1 receptor, their tissue distribution

and roles are different (20,37). It has been proven that SHH

protein plays a significant role in central nervous system

development (38). The activity

of IHH in skeletal tissue formation has been reported, whereas DHH

is present only in granulosa cells of ovaries and Sertoli cells of

the testis (20,32). Post-translational modifications

of all three hedgehog protein family members are required for their

attachment to the PTCH1 receptor (15). During this molecular process, the

full-length SHH protein (~45 kDa) undergoes autoproteolysis and

cleavage into the C- (C-SHH; ~25 kDa) and N- (N-SHH; ~19 kDa)

terminal domains (39,40). C-SHH is an auto-processing

molecule that participates in the attachment of cholesterol to the

C-terminal end of N-SHH. Furthermore, the N-terminal end of N-SHH

binds to palmitic acid moiety through the reaction induced by

hedgehog acyltransferase (HHAT), which is necessary for its full

biological activity (41,42).

The activity of HHAT may be blocked by the use of RU-SKI inhibitors

(RU-SKI 41, 43, 101 and 201; not shown in the figures) (43); however, overall cytotoxicity was

observed for RU-SKI 41, 43 and 101 in an in vitro study

(44). Currently, there are no

data available regarding the use of RU-SKI inhibitors in clinical

studies, at least to the best of our knowledge. Finally, through

its interaction with dispatched resistance-nodulation-division

(RND) transporter family member 1, modified N-SHH is secreted to

the extracellular matrix (ECM) and may act as a biologically active

upstream regulator of the SHH pathway (Fig. 1B) (15,45,46). Therefore, the binding of N-SHH

may present another target in cancer drug studies. For that reason,

5E1 antibody against N-SHH (Fig.

1B) was analyzed in a mouse model of pancreatic cancer, and was

found to have a promising effect in the reduction of tumor size and

angiogenesis (47). The final

interaction between N-SHH ligand and PTCH1 may occur in either an

auto- or paracrine way (40),

which will be discussed below in the present review.

PTCH1 protein

The PTCH1 receptor, encoded by the PTCH1 gene

at 9q22.32, is composed of 1,447 amino acids, arranged in 12

transmembrane helices, two extracellular domains (1 and 2) that can

attach extracellular ligand N-SHH and one cytoplasmic

carboxyl-terminal domain (48).

Mutations in the PTCH1 gene lead to an autosomal dominant,

multisystem disorder known as Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome,

also known as the Gorlin-Goltz syndrome (49). The patched protein family also

includes PTCH2 receptor (50).

Although both PTCH1 and PTCH2 can bind to Hedgehog ligands with the

same affinity, PTCH2 appears to have a lower ability to inhibit the

SMO protein (20,45,51). PTCH1 acts as a negative regulator

of the SHH pathway by inhibiting SMO protein from translocating to

the plasma membrane (Fig. 1A).

The mechanism of this inhibition is not yet fully understood;

however, recent studies have suggested the involvement of

cholesterol or another sterol lipid in this regulation (52,53). Following SHH pathway activation,

the blockade of PTCH1 is abolished and the receptor undergoes

internalization, while SMO protein is exposed on the cell surface

in the primary cilium (54).

PTCH1 subsequently undergoes endocytosis, followed by

ubiquitination and lysosomal degradation through E3 ubiquitin

ligase SMAD specific E3 ubiquitin protein ligase 1/2 (Smurf1-2;

Fig. 1B).

Smoothened protein

Smoothened protein belongs to the F-class of the

G-protein-coupled receptor superfamily and is a key intracellular

positive SHH pathway regulator (55,56). Research on SHH signaling in D.

melanogaster has indicated that biochemical processes, such as

phosphorylation or sumoylation, are required to obtain full SMO

activity (57). In mammalian

cells, ciliary localization of this molecule appears to be crucial

for SMO activation, as well as post-translational SMO

modifications, which are analogous to those in Drosophila

cells (58). The ciliary

translocation of SMO occurs following phosphorylation by a

β-adrenergic-receptor kinase (G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2)

and is followed by an interaction between cytosolic β-arrestin

(ARBB) and clathrins (59).

Following ciliary translocation, SMO is further phosphorylated by

casein kinase 1α, and then SMO-β-arrestin complex recruits motor

protein kinesin family member 3A (Kif3A), which consequently

interacts with the kinesin family member 7 motor protein

(KIF7)-SUFU-GLI2/3 ciliary located complex (Fig. 1B) (60). The SMO protein is the main

anticancer treatment target among all SHH pathway proteins

(61). Several SMO inhibitors

are in clinical trials, and three of them (vismodegib, sonidegib

and, in November 2018, glasdegib) have been approved for selected

cancer treatment by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

(61,62). However, this molecular treatment

has certain limitations, including the development of drug

resistance due to frequent SMO mutations, as well as the presence

of alternative SMO-independent mechanisms of GLI transcription

factor activation (63,64), which are discussed in the

following paragraphs.

GLI proteins

Cubitus interruptus has been identified as a

transcription factor of the Hedgehog pathway in D.

melanogaster (41,65). In mammals, this protein has three

analogs (the GLI1, GLI2 and GLI3 molecules), which belong to the

Kruppel zinc-finger transcription factor family (66). The lack of a repressor domain in

GLI1 protein structure suggests that this molecule may act only as

a transcription activator, while GLI2 and GLI3 possess both

repressive (GLI2/3R; Fig.

1A) and activating (GLI2/3A; Fig. 1B) properties (20). Furthermore, several isoforms of

GLI1 and GLI2 (called GLIΔN or tGLI), which are the products of

alternative splicing, have been identified in human tissues

(65). tGLI1 has been detected

only in cancer samples and been associated with aggressive behavior

of the disease (67-69). In the absence of SHH, GLI2/3 are

attached to the SUFU molecule in the ciliary location by KIF7

(Fig. 1A). GLI2/3 underwent

phosphorylation by glycogen synthase kinase (GSK)-3β, protein

kinase A (PKA) and CK1, which is triggered by cyclic AMP produced

by G protein-coupled receptor 161 (Gpr161). Such action causes

proteolytic cleavage of GLIs' C terminus by cullin 1 (CUL1) and β

transducin repeat-containing protein (β-TrCP), leading to the

removal of their transcriptional activation domain. Cleaved GLI2/3,

in the form of GLI2R and GLI3R, translocates

to the nucleus and act as inhibitors/repressors after binding to

regulatory regions of SHH target genes (21,70).

Following the activation of the canonical SHH

pathway, the SMO-β-arrestin complex inhibits Gpr161 and cyclic

adenosine monophosphate-dependent PKA (Fig. 1B) (71), which blocks the phosphorylation

and proteolytic cleavage of GLI2/3. Subsequently, the GLI2/3

KIF7/SUFU/GLI2/3 complex dissociates, and full-length GLIs undergo

several posttranslational modifications, including phosphorylation,

ubiquitination and sumoylation (70), and may simultaneously undergo

proteolysis mediated by CUL3 and speckle-type POZ protein (72). The activity of GLI2A

and GLI3A transcription factors may then be upregulated

by various cytoplasmic factors on their way to the nucleus. There

are several protein kinases [casein kinase II (CK2), protein kinase

B (AKT), extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2),

ribosomal protein S6 kinase 1 (S6K1), dual specificity tyrosine

phosphorylation regulated kinase 1B (DYRK1B) or unc-51 like kinase

3 (ULK3)] (73), which

phosphorylate GLI2/3A (Fig. 1B), thus promoting GLI

translocation into the nucleus. Acetylation/deacetylation of GLIs

is another important factor that regulates their transcriptional

activity (70). Acetylation of

GLI1/2 by p300/CBP complex prevents GLIs from attaching to DNA and

provides nuclear export through exportin 1 and LAP2 proteins

(70,74). On the contrary, GLI deacetylation

by histone deacetylase HDAC1 enables them to interact with genomic

DNA (75). Of note, HDAC1

is upregulated by GLIs; therefore, the HDAC1-GLIs interaction forms

a positive feedback loop with the SHH pathway (70,75). A significant role of primary

cilium in the functioning of the GLI proteins has been recently

reported. In the absence of the SHH ligand, GLI2/3-SUFU complexes

are transported to the tip of the cilium by kinesin through the

microtubule cytoskeleton, while GLI2 translocation to the cell

nucleus following ligand stimulation occurs through dynein-2

(76). The in vivo

studies by Wong et al (77) and Han et al (78) revealed that the removal of the

Kif3a allele, which is essential for cilia formation, leads

to the inhibition of both BCC and medulloblastoma, respectively.

However, this effect was observed only in lesions overexpressing

the SMO gene, but not the constitutively active GLI2

gene. Therefore, the primary cilium components could be a molecular

target for SMO-dependent neoplasms (77,78).

Due to frequent mutations in the SMO receptor, which

lead to cancer resistance to previously mentioned SMO-targeted

drugs (64), blocking

cytoplasmic/nuclear GLI-activator proteins is one of the recently

identified targets (30,79). It has been found that CK2, DYRK1B

and S6K1 protein kinases, as well as HDAC1, do not require

SMO-dependent activation of the SHH pathway to activate GLIs

(64). This observation provides

reasoning for examining the activity of several potential drugs,

including CIGB-300 and CX-4945 targeting CK2 (80), CCI-779 and RAD001 targeting S6K1

(81), BVD-523 targeting ERK1/2

(82), MK2206 targeting AKT

(83), AZ191 inhibiting DYRK1B

(84) and SU6668 targeting ULK3

(85). It has also been reported

that HDAC1 deacetylation activity is successfully blocked by

4SC-202 (17), with

GLI-DNA-interaction inhibitors (glabrescione B and GANT61) as well

as GLI2 destabilizers (arsenic trioxide and pirfenidone) (Fig. 1B) (17). It is worth noting that the GLI

proteins are also involved in other cancer-related pathways, which

are discussed below in the present review.

3. Role of microRNAs (miRNAs/miRs) in

upstream SHH gene regulation

The SHH ligand is a major molecule that activates

SHH signaling. It is, therefore, of no surprise, that studies

regarding the upstream regulation of the SHH gene have been

performed to complete the understanding of the role of the SHH

pathway in carcinogenesis. The available data are schematically

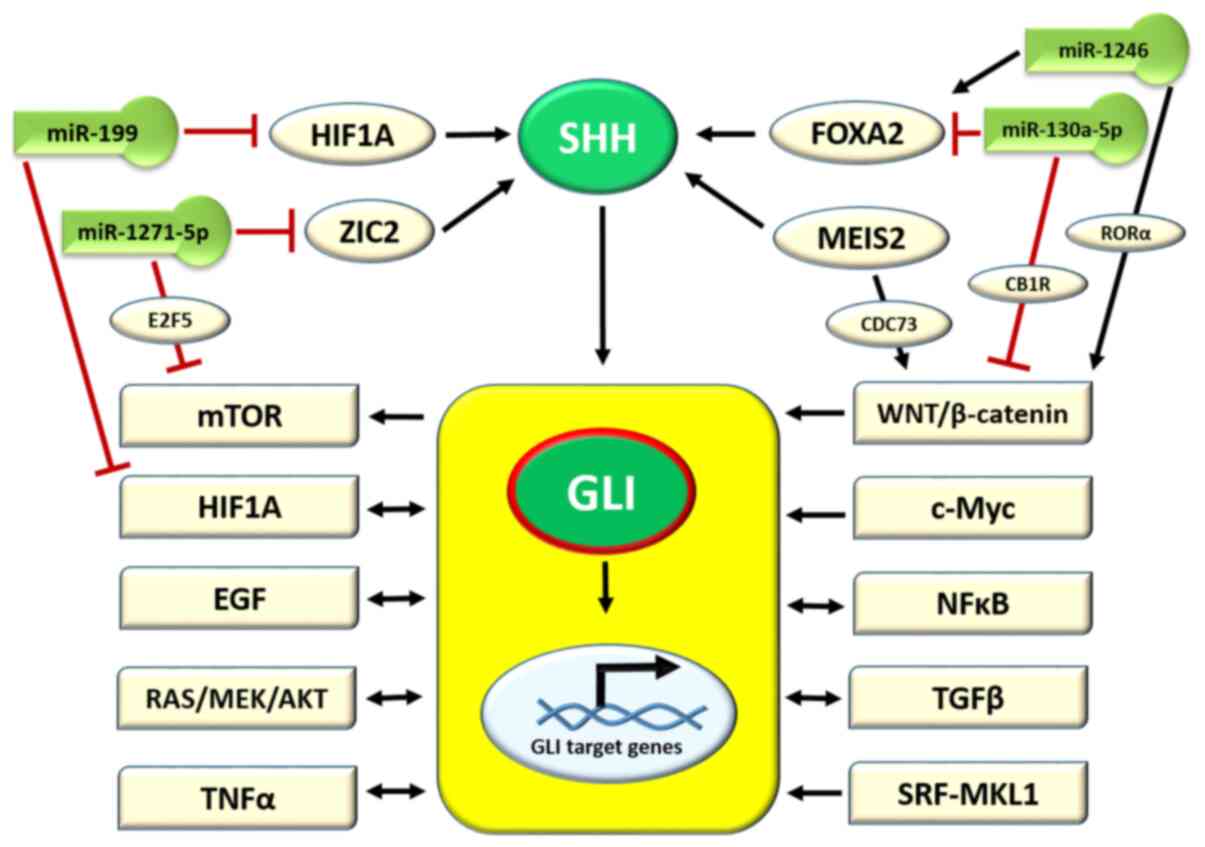

presented in Fig. 2. Due to the

important role of SHH signaling in the CNS formation during fetal

life, the majority of studies are based on CNS diseases associated

with SHH pathway alterations. In this regard, Schachter and Krauss

(86) observed, in a mouse model

of holoprosencephaly, that the activation of the SHH gene

was regulated by zinc finger protein 2 (ZIC2). ZIC2 protein belongs

to the zinc-finger transcription factor family, and its deficiency

results in holoprosencephaly 5, as observed by Barratt and Arkell

(87), also in a murine model.

In addition, ZIC2 activity is regulated by the miRNA/miR molecule,

miR-1271-5p, as reported by Chen et al (88) in an in vitro study on AML.

In turn, miR-1271-5p inhibits carcinogenesis in ovarian cancer (OC)

and negatively regulates the mechanistic target of rapamycin kinase

(mTOR) pathway through the E2F5 transcription factor protein

(89). Another study on

SHH gene activation in a CNS murine model revealed the

positive role of forkhead box protein A2 (FOXA2) transcription

factor in this process (Fig. 2),

while the lack of FOXA2 was found to result in a lethal birth

defect known as congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) (90). The FOXA2/SHH axis is also

negatively regulated by the miR-130a-5p molecule, which has been

found to be overexpressed in CDH (90). The progression of gastric cancer

is associated with a decreased expression of miR-130a-5p; in turn,

this deficiency causes an upregulation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling

by targeting cannabinoid receptor 1 (Fig. 2) (91). Other studies on melanoma

progression and hepatocellular carcinoma demonstrated that FOXA2

was activated by the miR-1246 molecule and, in turn, triggered the

Wnt/β-catenin pathway by retinoid-related orphan receptor α nuclear

receptor (Fig. 2) (92,93). A myeloid ecotropic insertion site

2 (MEIS2) transcription factor is another molecule that activates

the expression of the SHH gene for patterning the mandibular

arch during fetal development, as observed by Fabik et al

(35) in a mouse model. The

upregulation of MEIS2 was observed in castration-resistant prostate

cancer (PC) (94) and

hepatocellular carcinoma, where its isoform MEIS2C activates the

Wnt/β-catenin pathway by interacting with the CDC73 molecule

(95). The hypoxia-inducible

factor 1-α (HIF1A) transcription factor is an important molecule

triggered by hypoxia in the cells and tissues of fetal and mature

organisms. It has been observed that HIF1A activates SHH secretion

in the frontonasal ectodermal zone during upper jaw development

(96). Furthermore, the

upregulation of HIF1A and, indirectly, the HIF1A pathway is halted

by the miR-199b molecule (Fig.

2) (96). In conclusion, SHH

secretion is regulated by cellular transcription factors, which in

turn are mostly regulated by miRNA molecules involved in the

regulation of various cellular pathways (Fig. 2).

4. Activation of the target genes of the SHH

pathway via GLI factors and crosstalk with other cellular

pathways

Several dozen target genes of GLI1-3 have been

identified, which are summarized in Table II. Of note, GLI2/3A

stimulates the expression of GLI1, which in turn recognizes

the same DNA motive in target genes (5′-GACCACCCA-3′) as

GLI3A, with GLI2A recognizing an almost

identical sequence (5′-GAACCACCCA-3′) (15). Therefore, the expression of

GLI1 acts as a positive feedback loop for SHH signaling

(Fig. 1B) (41). On the contrary, two genes of the

SHH pathway negative loop are simultaneously activated by GLIs:

PTCH1 (97) and hedgehog

interacting protein (HHIP); once their protein products

reach the plasma membrane, PTCH and HHIP may decrease the rate of

SHH signaling, due to their binding to the extracellular N-SHH

ligand (41) (Fig. 1B). Other genes activated by

GLI1-3 encode proteins that are involved in the processes of cell

proliferation (MYCN proto-oncogene, bHLH transcription factor),

cell cycle regulation (CCND1), angiogenesis (VEGF)

and cell survival (BCL2) (37,98). They are also responsible for the

stimulation of mechanisms strongly associated with tumorigenesis,

such as activating invasion and metastasis [genes encoding matrix

metallopeptidases and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β], cell

immortality maintenance (gene encoding telomerase reverse

transcriptase) or avoiding immune destruction [genes encoding

interleukin (IL)-4 and suppressor of cytokine signaling 1].

Therefore, since the SHH pathway interacts with the molecular

events important for cancer development and progression, it may be

a promising target for anti-tumor therapy (37).

| Table IISonic Hedgehog signaling target genes

and their impact on cells or the SHH pathway. |

Table II

Sonic Hedgehog signaling target genes

and their impact on cells or the SHH pathway.

| Gene | Protein, full

name | function | (Refs.) |

|---|

| ABCG2 | ABCG2, ATP binding

cassette subfamily G member 2 (Junior blood group) | ABC transporters,

cellular defense mechanism of xenobiotics removal | (197) |

| ALDH1A1 | ALDH1A1, aldehyde

dehydrogenase 1 family member A1 | Metabolism of

alcohol and retinol, stemness of cancer cells | (177,198) |

| BCL2 | BCL2, BCL2

apoptosis regulator | Inhibition of

apoptosis | (199) |

| BIRC5 | baculoviral IAP

repeat containing 5, survivin | Inhibition of

apoptosis | (173) |

| BMP4 | BMP4, bone

morphogenetic protein 4 | Ligand of the TGF-β

superfamily of proteins, regulation of heart and teeth development

and adipogenesis | (200) |

| CCND2 | Cyclin D2 | Cell cycle

inhibition | (37) |

| CD24 | CD24 | Modulation of

growth and differentiation of B cells, neutrophils and neuroblasts;

association with stemness state of cancer stem cells | (201) |

| CDH2 | CDH2,

N-cadherin | Cell adhesion

molecule; development of nervous system and formation of bone and

cartilage; EMT in cancer development | (190) |

| CDK1 | CDK1,

cyclin-dependent kinase 1 | Essential kinase

for G1/S and G2/M phase transitions; cell cycle control | (202) |

| FGF3/4 | FGF3/4, fibroblast

growth factor 3/4 | Mitogenic and cell

survival activities | (200) |

| FOXM1 | FOXM1, Forkhead box

M1 | Transcription

factor; cell proliferation | (181,203) |

| GLI1 | GLI1, GLI family

zinc finger 1 | Positive feedback

of SHH signaling | (28) |

| HDAC1 | HDAC1, histone

deacetylase 1 | Key role in

regulation of gene expression, modulates p53, activates GLIs

forming positive loop | (75) |

| HHIP | HHIP, hedgehog

interacting protein | Decoy for N-SHH

ligand; negative regulator of SHH | (51) |

| JAG1 | JAG1, jagged

canonical Notch ligand 1 | Notch ligand and

Wnt signaling pathway; hematopoiesis | (204) |

| MMP7 | MMP7, matrix

metalloproteinase 7 | Cancer invasion and

angiogenesis by the proteolytic cleavage of ECM and basement

membrane proteins; activated by GLI2 | (175) |

| MYCN | MYCN

proto-oncogene, bHLH transcription factor | Cell proliferation,

neoplastic transformation | (205) |

| NANOG | NANOG, Nanog

homeobox | Transcription

factor involved in embryonic stem (ES) cell proliferation, renewal,

and pluripotency | (17) |

|

PAX6/7/9 | PAX6/7/9, paired

box 6, 7, 9 | Fetal development

of organs: Eye (PAX6), skeletal muscle (PAX7), tooth (PAX9) | (206,207) |

| PTCH1 | PTCH1, patched

1 | Negative regulator

of SHH pathway | (41,97) |

| SNAI1 | SNAI1, snail family

transcriptional repressor 1 | Transcriptional

repressor which downregulates the expression of ectodermal genes

within the mesoderm; EMT in cancer development | (205) |

| SOX2 | SOX2, SRY-box

transcription factor 2 | Transcription

factors involved in the regulation of embryonic development and in

the determination of cell fate | (208) |

| VEGFA | VEGFA, vascular

endothelial growth factor A | Angiogenesis;

induction of proliferation and migration of vascular endothelial

cells | (209) |

GLI-activated genes (Table II) are associated with various

pathways in the cell, which determine the cell's fate and play an

important role in tumorigenesis. As previously mentioned, certain

cellular pathways are regulated by miRNA molecules, which

indirectly act on the SHH pathway through the regulation of the

SHH gene expression. Furthermore, GLIs activate the

expression of genes involved in cellular signaling. However, it has

also been observed that different pathways may upregulate

components of the SHH pathway, and these interactions are

schematically presented in Fig.

2. The hypoxia-induced HIF1A pathway triggers SHH,

SMO and GLI expression, thus influencing cell

stemness and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in

cholangiocarcinoma (99). On the

contrary, GLI1 is necessary for hypoxia-modulated EMT and

invasiveness of MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells (100). It was observed in a previous

study that the KRAS proto-oncogene of the MAPK/ERK pathway

increases GLI1 transcriptional activity and the expression of SHH

pathway target genes in gastric cancer (101). The epidermal growth factor

(EGF) pathway is associated with SHH in a complex way: The

simultaneous activation of the SHH/GLI and EGF pathway

synergistically induced oncogenic transformation of human

keratinocytes, an effect that was dependent on the activation of

MAPK/ERK signaling (21). The

influence of AKT protein on PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling leads to

nuclear translocation, and elevated activity and stability of GLI1

(Fig. 1B) in melanoma (102) and OC cells (103). Moreover, certain studies have

revealed that the main tumor suppressor protein, p53, plays a role

in the inhibition of transcriptional activity, nuclear

translocation, protein stability and the disruption of the DNA

binding ability of GLI1 (63).

The induction of the expression of SNAIL,

proto-oncogene Int-1 homolog and secreted frizzled-related protein

1 by GLIs indicates the impact of SHH on the Wnt/β-catenin pathway

(104). Different analyses of

hair follicle morphogenesis and development have revealed a key

regulation of the NF-κB pathway upon Wnt and SHH signaling

(105). Research on

gastrointestinal stromal tumors has indicated an association

between SHH and PI3K and mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways

(106). The activation of the

c-MYC pathway induces the upregulation of GLI1, while both

10058-F4 and GANT61, c-MYC and GLI1 inhibitors respectively, have

been found to increase apoptosis and reduce the viability of the

Burkitt lymphoma cells (107).

Research on drug-resistant BCC cells has revealed a novel

activation of GLI1 expression triggered by transcription

factor serum response factor together with its co-activator,

megakaryoblastic leukemia 1 (108).

The differential activation of the SHH pathway has

been observed in systemic sclerosis. The enzyme HHAT, which

catalyzes the attachment of palmitate onto the SHH molecule, is

regulated in a TGF-β-dependent manner and, in turn, stimulates

TGF-β-induced long-range hedgehog signaling to promote fibroblast

activation and tissue fibrosis (109). Last but not least, research on

PC3 and DU145 PC cell lines has demonstrated that the tumor

necrosis factor α-triggered mammalian target of rapamycin

(TNFα/mTOR) pathway is connected with GLI activation by S6K1

(Fig. 1B) (110). The list of the complex

associations between SHH and other pathways involved in

tumorigenesis is still growing, suggesting the pivotal role of GLI

modulation in cancer development (21).

5. Non-canonical, GLI-independent activation

of SHH signaling

Previous studies have revealed that the SHH

canonical SHH/PTCH1/SMO/GLI pathway may trigger different cellular

mechanisms without activating GLI transcription factors (20,111). This activity was divided into

two modules: Module 1 included those not demanding SMO protein, and

module 2 those activated by SMO but not requiring GLIs (20,111). However, it should be noted that

other studies merged 'non-canonical SHH activation' with 'GLI

activation' via other (not SHH/PTCH1/SMO) cellular pathways

(63), interactions that were

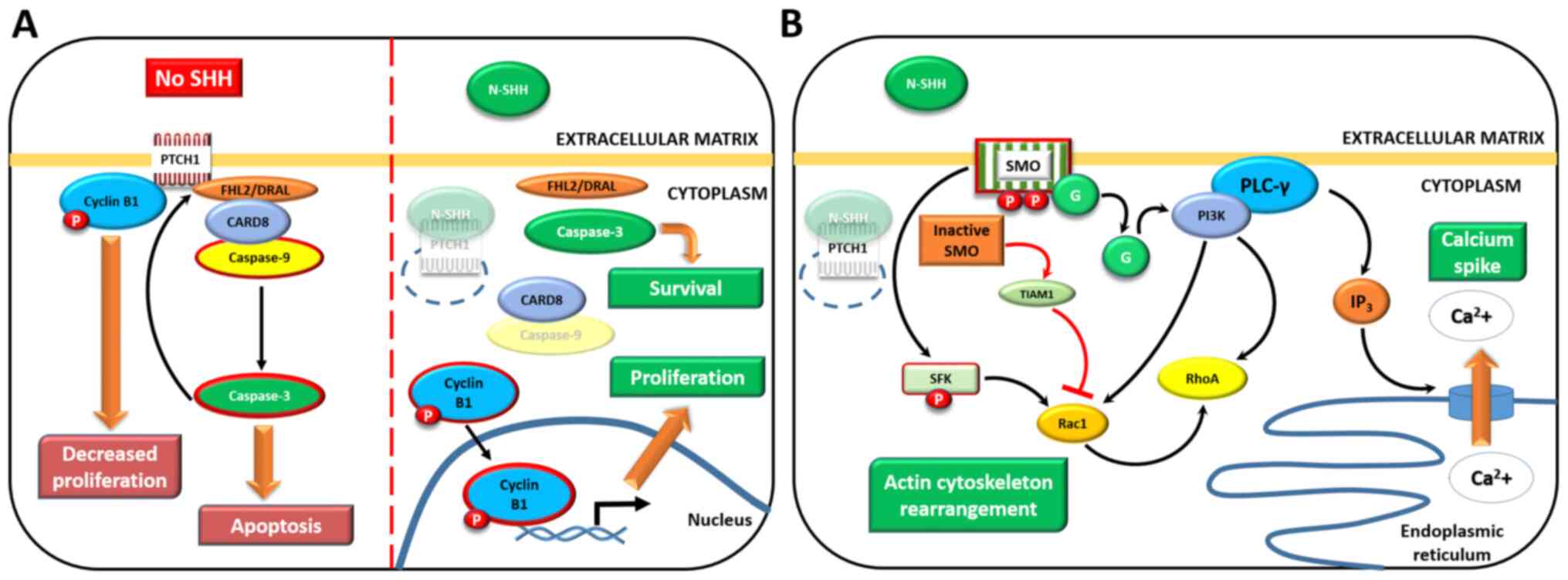

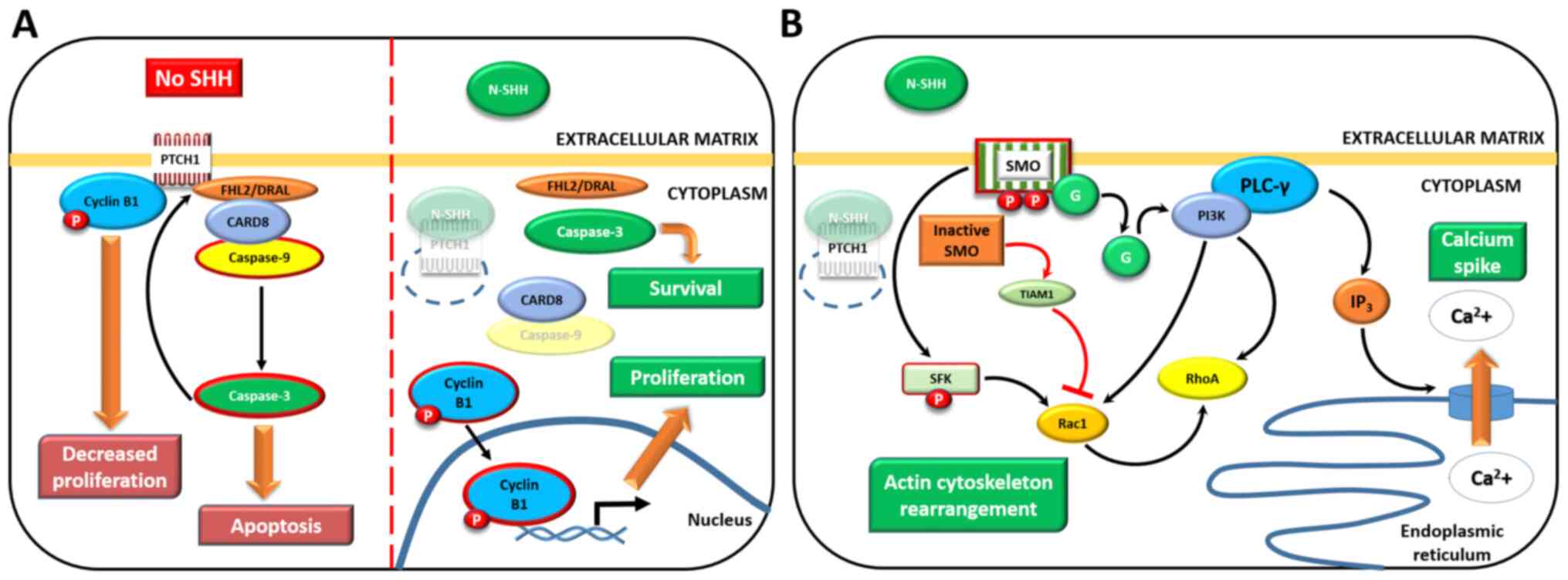

discussed in the previous section. Both modules are presented in

Fig. 3. According to module 1,

in the absence of the SHH ligand (Fig. 3A), phosphorylated cyclin B1

[active mitosis promoting factor (MPF)] is bound to PTCH1 during

G2/M cell cycle transition, thus decreasing the cellular

proliferation rate, as observed in 293T cells (112). On the contrary, PTCH1-mutant or

SHH-stimulated BCC cells (with wild-type p PTCH1) were

characterized by MPF nuclear translocation and an increased

proliferation rate (Fig. 3A,

right panel) (113). The impact

of PTCH1 activation on apoptosis relies on caspase-3 activity

(Fig. 3A, left panel). In the

absence of SHH, it cleaves C-terminal PTCH1 domain

(Asp1392), thus releasing caspase recruitment domain

family member 8 (CARD8) protein, and the adaptor protein four and a

half LIM domains 2/DRAL (111).

This action activates caspase-9, which in turn speeds up the

formation of this complex by promoting the activation of caspase-3,

leading to caspase-9-dependent apoptosis (114,115). When PTCH1 is inactivated by

SHH-binding, CARD dissociates to protein components without

caspase-9 activation. This leads to a decreased apoptotic ratio

(Fig. 3A, right panel), as

observed in 293T cells and in a chicken embryo model (115).

| Figure 3GLI-independent, non-canonical

activation of the SHH pathway. (A) Type 1: SMO-independent

mechanism (left panel, in the absence of the SHH ligand; right

panel, SHH is bound to PTCH1). (B) Type 2: SMO downstream effectors

that do not require GLIs; in the presence of SHH only (with the

exception of SMO-TIAM1 activity, red arrows). Activated proteins

are surrounded by red borders, degraded proteins are partially

transparent and thick brown arrows point at activated mechanisms

(in cropped rectangles). See main text for details. Adapted from a

previous study (112). SHH,

Sonic Hedgehog; GLI, GLI family zinc finger; SMO, smoothened,

frizzled class receptor; PTCH1, patched 1; TIAM1, TIAM Rac1

associated GEF 1. |

Another model of non-canonical SHH activation

involves the SMO protein and its downstream effectors, except GLIs

(Fig. 3B). Phosphorylated SMO

(please see Fig. 1B) uses

Gi proteins to activate PI3K kinase, followed by

Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1 (Rac1) and Ras

homologous (Rho) protein activation. Furthermore, Rac1 may be

triggered by SMO by phosphorylated SFK kinase. As part of the

feedback SMO-Rho pathway, inactive, dephosphorylated SMO inhibits

Rac1 through the TIAM Rac1 associated GEF 1 protein (Fig. 3B, red arrows) (111,116). Such pathways give a

considerably faster cellular response than GLI activation, and

result in the rebuilding of the Rho-dependent actin cytoskeleton;

stress fiber formation and tubulogenesis, as observed in

endotheliocytes, result in tumor-dependent angiogenesis (117). SHH-SMO-regulated Rho-dependent

actin cytoskeleton rear-rangement resulting in fibroblast migration

(118) has been found to be

critical to dendrite spine formation in hippocampal and cerebellar

neurons (116). The regulation

of calcium ions significantly affects the proliferation,

differentiation, apoptosis and migration of neuronal and neuronal

precursor cells (111).

SHH-SMO-G protein activation of phospholipase C-γ has been shown to

result in the production of PI3K secondary messenger in Rohon-Beard

embryonic neurons, which opened calcium channels in SER membrane,

thus leading to concentration-dependent Ca2+ transport

from SER to cytosol ('calcium spike'; Fig. 3B) (119). Of note, the latter actions of

the SHH-SMO non-canonical pathway on nervous tissue play a

similarly important role to that of GLI canonical activation during

CNS formation (20,111,116,119).

6. SHH signaling in cancer cells and its

implications for the tumor microenvironment

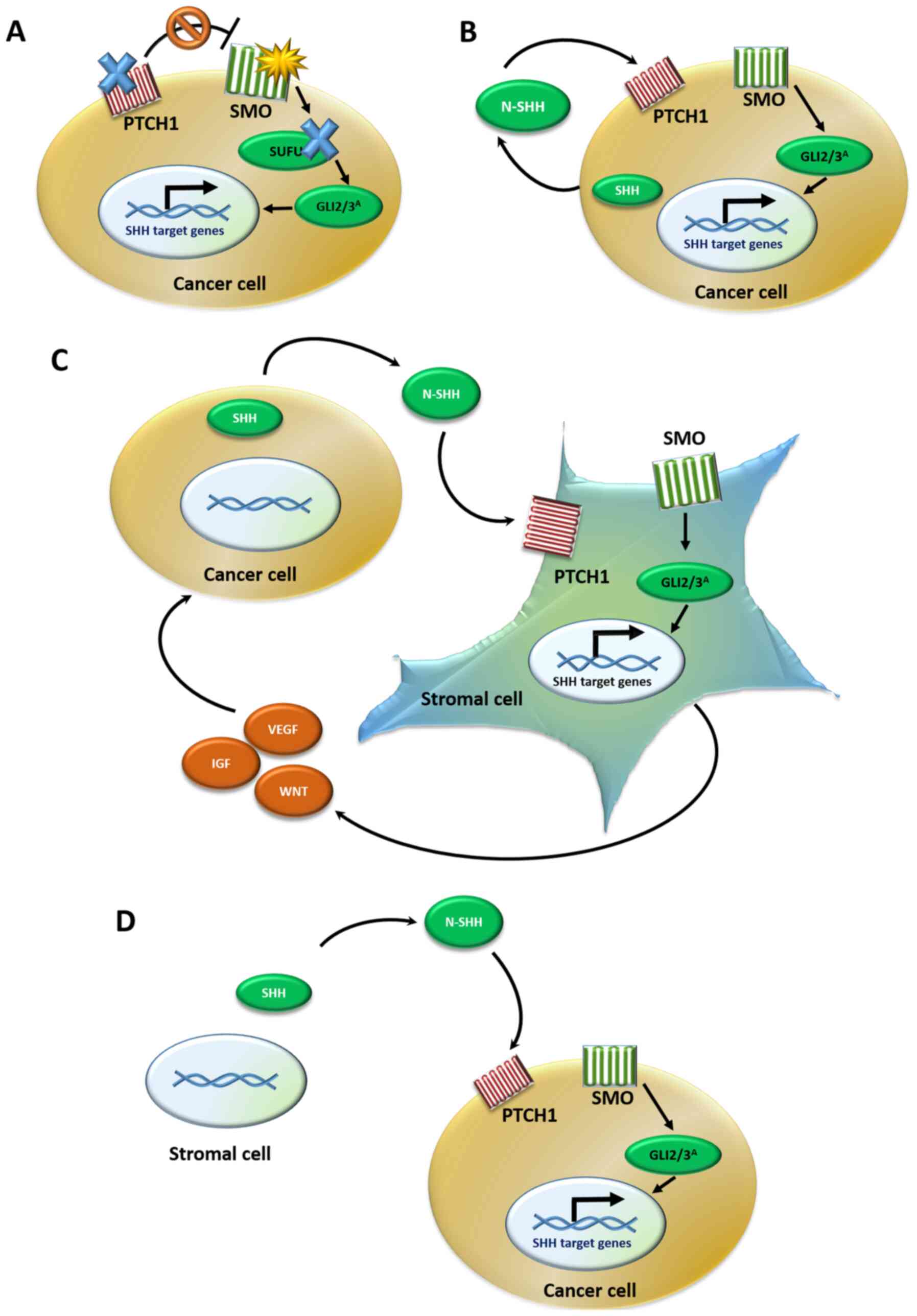

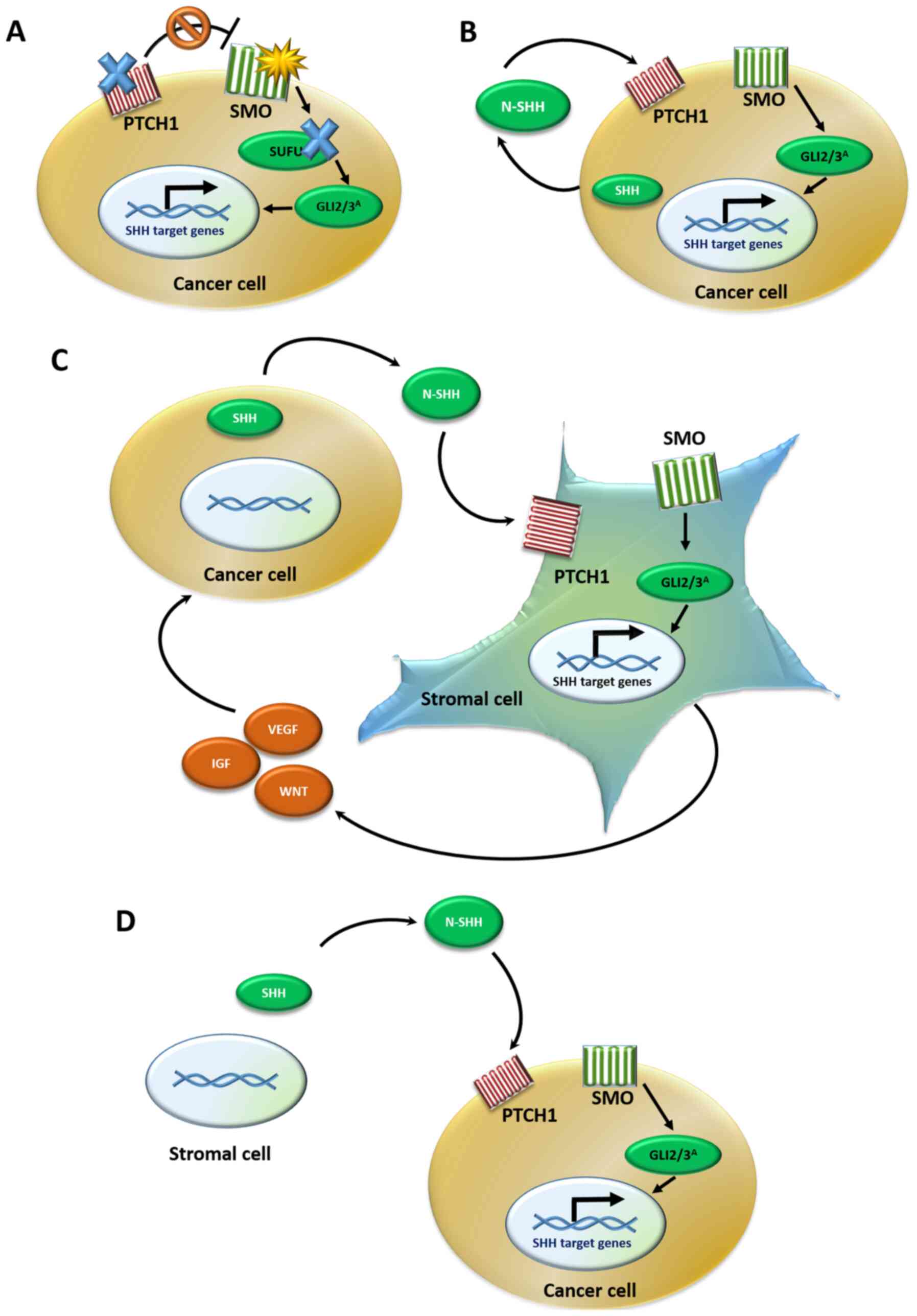

The different modes of SHH pathway activity in

various neoplasms can be divided into three types, which are shown

in Fig. 4. Type I (Fig. 4A) is caused by activating

mutations in the SMO gene and inactivating mutations in the

PTCH1 or SUFU genes in tumor cells. This leads to the

uncontrolled stimulation of GLI transcription factors and,

ultimately, SHH pathway target genes. Consequently, the cells

acquire the ability to increase the rate of proliferation,

intensify angiogenesis and suppress apoptosis (120). Type I SHH signaling activation

has mainly been observed in BCCs, either in sporadic cases or

hereditary disorders, such as Gorlin-Goltz syndrome (15). A study that included 42 BCC tumor

samples, revealed PTCH1 gene inactivation in 67% cases,

increased SMO gene expression in 10% cases and a SUFU

gene mutation in 5% cases (121). Furthermore, non-epithelial

tumors, such as medulloblastoma and rhabdomyosarcoma, are another

type of neoplasm that may be associated with type I SHH pathway

dysregulation (15). Since this

type of regulation is ligand-independent, targeted SHH therapy

should affect downstream pathway effectors such as GLI

transcription factors (120).

| Figure 4Models of the SHH signaling pathway

in cancer. (A) Type I: Ligand-independent activation occurs due to

either PTCH1 or SUFU inactivating mutations (blue X)

or SMO activating mutations (yellow star), which lead to the

constitutive activation of GLI effectors, even in the absence of

the N-SHH ligand. (B) Type II: Ligand-dependent autocrine

activation. Cancer cells both synthesize and bind to the SHH

ligand, resulting in a positive auto-loop activation of the SHH

pathway. (C) Type III: Ligand-dependent paracrine activation.

Cancer cells secrete the SHH ligand, which is bound by the stromal

cells leading to SHH pathway activation in the stroma. The stroma

reacts by secreting back various cancer-stimulating signals, such

as growth factors to the tumor tissue. (D) Type IIIb: Reverse

paracrine activation. Cancer cells receive SHH ligand secreted from

the stroma, leading to SHH signaling activation in the tumor cells

and upregulation of survival signals. SHH, Sonic hedgehog; PTCH1,

patched 1; SUFU, SUFU negative regulator of hedgehog signaling;

SMO, smoothened, frizzled class receptor; GLI, GLI family zinc

finger. |

In type II SHH signaling activation (Fig. 4B), the SHH (or IHH) ligand is

exposed on the cancer cell surface and may act on the adjacent

cancer cells in either an autocrine or juxtacrine manner.

Consequently, the SHH pathway becomes reactivated in target tumor

cells, and the final effects are the same as those in type I, since

they result in cancer development and progression (120). Type II SHH signaling activation

in cancer is characterized by the overexpression of SHH components

at the mRNA level in cancer cells (but not in stromal cells), as

found in four hepatoma cell lines, using the reverse transcription

PCR method. Moreover, the immunoreactivity of SHH, PTCH1 and GLI2

proteins was significantly elevated in human hepatocellular

carcinoma samples derived from 57 patients, compared to

non-cancerous liver tissues (122).

Paracrine, ligand-dependent signaling between tumor

and surrounding stromal cells is involved in type III

cancer-related SHH alterations (Fig.

4C). The SHH protein can be secreted in excess by cancer cells

into the tumor stroma, which leads to the activation of SHH

signaling in stromal cells. In response, stromal cells release

various SHH signaling target proteins to their microenvironment,

which stimulate tumor growth and progression. Furthermore, a

reverse paracrine type III mechanism has been observed, in which

the PTCH1 receptor on cancer cells binds to the SHH ligand, that is

synthesized by stromal cells, which also increases cancer cell

viability (15,120). This type of regulation

(Fig. 4D) was observed in a

pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma mouse model (123) and human pancreatic and

metastatic cancer specimens (123). The expression of SHH and

IHH was elevated in tumor cells; however, stromal

GLI1 mRNA levels were found to be 13-150-fold higher than

those in cancer cells, suggesting a paracrine SHH signaling

activation in stromal cells (123). In addition, the association

between SHH and GLI1 mRNA levels has been found in

stromal cells, but not in tumor cells derived from 22 samples of

primary human tumor colorectal adenocarcinoma xenografts (124).

With regards to types II and III SHH pathway

activity in tumor tissues, therapy including both anti-SHH ligand

molecules, such as an anti-SHH antibody, and SMO and GLI protein

inhibitors, may be effective (120). As described above with regards

to the activation of GLIs, the existence of both canonical and

non-canonical SHH pathways should always be considered in studies

on potential SHH pathway-targeted treatments. For certain types of

neoplasms, combination therapy, such as treatment with an SHH

signaling inhibitor and an inhibitor of another signaling pathway,

may be effective. For example, an ongoing clinical phase II trial

is evaluating the combination of sonidegib (SMO inhibitor) with

buparlisib (PI3K inhibitor) in patients with locally advanced or

metastatic BCC (18).

Among the stromal cells of the tumor

microenvironment involved in the type III mechanism of SHH

signaling in cancer tissue, cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs)

appear to play an important role (125). CAFs resemble myofibroblasts in

terms of morphology and molecular features. They can originate from

different cell types, such as resident fibroblasts, mesenchymal

stem cells or epithelial cells, resulting in a significant CAF

heterogeneity. The signals for CAFs activation may be derived both

from factors secreted by cancer cells, such as TGF-β1 and IL-6, as

well as physical properties of the tumor micro-environment,

including hypoxia and ECM stiffness (126). There have been reports on SHH

pathway paracrine stimulation in CAFs, either by tumor cells

(17) or cancer stem cells

(CSCs) (127). Subsequently,

CAFs are stimulated to secrete molecules that promote

VEGF-dependent tumor angiogenesis and self-renewal in CSCs

(17,127). The association between SHH

signaling and CAFs was observed in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

(128) and mammary gland tumors

(127).

Other cells of the tumor microenvironment that can

be indirectly affected by the SHH pathway are tumor-associated

macrophages (TAMs) (125).

Although the role of TAMs in tumor development is still not

well-described, certain studies have suggested that the cellular

PTCH1/SMO/SUFU/GLI1-3 cascade not only elevates TAM infiltration

within the tumor stroma, but also promotes the acquisition of the

anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype responsible for tumor tissue

avoidance of immune destruction (129). The proposed mechanism

responsible for recruiting TAMs to the neoplastic niche includes

SHH-ligand-driven CAFs, which secrete molecules, such as

granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, C-C motif

chemokine ligand (CCL)2, CCL5 and C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 12.

Consequently, the number of cells with immunosuppressive

properties, including M2 phenotype-TAMs, myeloid-derived suppressor

cells and regulatory T cells, increase, which leads to a reduction

in immune effector cell infiltration (17). The significant role of TAMs in

the tumorigenesis of BCC (130)

and the subgroup of medulloblastomas with upregulated SHH signaling

has been reported (131). The

association between TAMs and SHH pathways, as well as their impact

on cancer-related immunosuppression, may lead to the discovery of

novel cancer immunotherapeutic strategies (131).

7. Sonic Hedgehog signaling in cancers of

the urinary tract

Kidney cancer

Kidney cancers, otherwise known as renal cell

cancers (RCCs), are a group of histologically different tumors

(132), which rank 14th in

incidence among other neoplasms worldwide (8). Clear cell RCC (ccRCC) is the most

common subtype (6) and is

associated with unfavorable outcomes (133). ccRCC development is strongly

associated with the inactivation of the von Hippel-Lindau tumor

suppressor (VHL) gene, which can be hereditary (VHL

syndrome) or occurs spontaneously during life (10,134-136). Other alterations in genes such

as PBRM1 or mTOR have been identified; however, no

specific prognostic or predictive molecular markers of RCC can be

recommended for clinical use (6,10). RCC therapy includes surgical and

pharmacological treatment in the advanced stages of the disease,

including tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) with sunitinib, the

first such drugs to be introduced, and mTOR kinase inhibitors

(everolimus) and several others, introduced into clinical treatment

over the past decade (6,137).

The first report regarding the expression of SHH

pathway components in ccRCC was published in 2009 (138). Dormoy et al (138) found that the SHH signaling

genes were expressed at the mRNA level in various RCC cell lines,

independently of VHL gene status. In that study the

overexpression of SMO and GLI1 mRNAs was also

revealed by RT-qPCR in RCC tumor tissues, compared with

corresponding normal kidney samples in the group of 8 patients.

Furthermore, incubation with cyclopamine (SMO inhibitor) decreased

ccRCC cell proliferation and increased apoptosis, as well as

induced the regression of ccRCC tumors in nude mice (138).

Further studies conducted on human RCC samples have

demonstrated the association between SHH signaling and cancer

progression. A study on 140 ccRCC specimens derived from patients

with non-metastatic disease revealed a significantly elevated DHH,

SHH, PTCH1 and GLI3 protein immunoreactivity in samples assessed as

G3 or G4 in Fuhrman's grading system [grades 3 and 4 in

International Society of Urologic Pathologists (ISUP) grading

(139)] than in those with

grade G1 or G2 (ISUP grades 1 and 2) (140). An elevated immunoreactivity of

the GLI2 transcription factor was found to be associated with a

poor prognosis in a group of 39 patients with metastatic ccRCC

treated with sunitinib (141).

In addition, in vitro experiments revealed a decrease in the

GLI2 protein level by western blot analysis in ACHN cells treated

with sunitinib, but not in sunitinib-resistant ACHN cells.

Therefore, these results suggested that GLI2 protein may be

involved in the mechanism of drug resistance associated with TKI

inhibitors in RCC (141).

Behnsawy et al (142)

demonstrated an association between the activity of SHH signaling

and EMT, an important step of cancer progression, in RCC cell

lines. The recombinant SHH ligand (r-SHH) not only significantly

increased proliferation in RenCa and ACHN cells, but also reduced

the mRNA level of E-cadherin, the epithelial marker of EMT,

suggesting a stimulating role of the SHH pathway in EMT (142).

Since several studies have reported a SHH

gene upregulation in RCC (140,142,143), the present review focused on

the occurrence of the upstream protein and miRNA regulators of SHH

expression in RCC. Shang et al (144) analyzed the mRNA expression

rates of the ZIC2 gene in 533 ccRCC and 72 normal kidney

samples (TCGA database), and found that the overexpression of

ZIC2 mRNA was associated with age, TNM, histological grade

and a shorter overall survival; thus, this gene can therefore be

used as an independent prognostic factor in ccRCC. Jia et al

(145) also analyzed TCGA data

from 525 patients with ccRCC focusing on SHH-associated FOX family

genes, and it was found that FOXA2 mRNA overexpression was

associated with poor outcomes.

As previously mentioned, RCC initiation is strongly

associated with the VHL gene status, which is inactivated in

a broad range of ccRCC cases. The gene encoding VHL protein, which

acts as an E3 ubiquitin ligase, is the enzyme responsible for

hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF1α and HIF2α) degradation under

normoxic conditions (136).

Therefore, Zhou et al (146) investigated the expression of

SHH pathway genes in normoxia and hypoxia, as well as the

association between the SHH signaling components and HIF2α. The

mRNA expression of all SHH signaling genes was significantly

elevated in RCC cell lines that were cultured under hypoxia,

compared with normoxic control RCC cells. Of note, the

re-activation of the SHH pathway under hypoxic conditions was

independent of VHL expression, with the dual inhibition of

HIF2α and GLI1 activity. Furthermore, the treatment with sh-HIF2a

and GLI1 inhibitor GANT61 significantly sensitized RCC cells to

ionic radiation. These results demonstrated that the SHH pathway

together with HIF2α protein may be involved in the molecular

mechanisms of RCC radioresistance. In addition, the SMO inhibitor,

cyclopamine, was not found to reduce the observed overexpression of

GLI1 under hypoxic conditions, which suggested that

GLI1 expression in RCC cells does not depend on upstream SHH

signaling components, but could be induced by different molecular

signaling (non-canonical activation) (146). Further evidence provided by

Zhou et al (147)

confirmed this conclusion and demonstrated an involvement of the

PI3K/AKT cascade on the main effectors of the SHH pathway in RCC

cells. PI3K/AKT signaling stimulation or inhibition induced or

decreased the expression of GLI1 and GLI2,

respectively. It was also demonstrated in vitro and in

vivo that the combination of GANT61 with the AKT specific

inhibitor, perifosine, was associated with a significantly enhanced

therapeutic potential, compared with that of the use of each

substance alone (147).

The efficacy of several other SHH inhibitors on

kidney cancer treatment has been under investigation over the past

few years. Erismodegib, a SMO antagonist, was previously shown to

inhibit the survival of the human 786-O RCC line, either alone or,

more effectively, in combination with sunitinib and everolimus

(148). This antitumor effect

was also observed in sunitinib-resistant RCC cells (786-O SuR

cells), revealing a novel research direction for RCC therapy. It

was also observed that erismodegib combined with sunitinib or

everolimus decreased the tumor volume and increased the survival of

nude mice with 786-O SuR cell-derived tumor xenografts, confirming

previously described results. However, unlike erismodegib, GANT61

had no inhibitory effect on RCC cells (148), indicating that SMO is a more

promising selective RCC therapy target than GLI transcription

factors.

In a previous study by the authors (143), the expression of SHH pathway

components in 37 ccRCC tissue samples, a significant correlation

was identified among the expression of almost all SHH signaling

genes at the mRNA level. Although the mRNA level of SHH,

SMO and GLI1 was increased in ccRCC samples, compared

to the morphologically unaltered kidney tissues, no association was

observed between the expression rates of genes and the pathological

features of patients. However, at the protein level, western blot

analysis of SHH revealed a significant increase of full-length SHH

and a decrease of the C-SHH domain in ccRCC tissues (143). This novel observation may

suggest an involvement of the SHH ligand in ccRCC development, and

indicate changes in the post-translational modification of this

protein during tumor progression.

Bladder cancer

According to the GLOBOCAN database, there were

549,393 new cases of bladder cancer in 2018, which renders this

type of cancer as the 11th most common type of cancer worldwide

(149). Approximately 90% of

bladder carcinomas are derived from the transitional epithelium

(1). Several studies have proven

the significance of nicotine and industrial gases in the

pathogenesis of this type of cancer (150,151). The disease risk assessment is

performed using clinical patient examination, medical imaging and

microscopic examination of the resected tumor tissues. The bladder

cancer guidelines recommend the tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) system

as an appropriate classification system for tumor staging. The

treatment of bladder cancer includes transurethral resection of the

bladder tumor for initial bladder neoplasms; however, for more

advanced tumors, radical cystectomy with lymphadenectomy and

additional radio- or chemotherapy are required (1). Genetic and epigenetic alterations

of bladder cancer cells, which may be useful prognostic factors or

targets for personalized therapy, are under investigation. The

molecular profile of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC)

differs significantly from muscle invasive bladder cancer (MIBC).

In addition, genetic alterations characteristic of low-grade NMIBC,

such as fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 (FGFR3) or

RAS mutations, can be distinguished among NMIBCs.

FGFR1, FGFR3, PNEN, CCND1 or MDM2

proto-oncogene genes have been identified as potential therapeutic

targets, whereas TSC complex subunit 1 or

phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit

alpha (PIK3CA) mutations may be predictive targets for mTOR

or PIK3CA/mTOR inhibitors, respectively (1,152).

In 2012, He et al (153) performed immunohistochemistry

(IHC) on 118 human bladder cancer samples. The expression of

proteins encoded by the SHH, PTCH1 and GLI1

genes was significantly elevated in tumor tissues, compared to 30

adjacent normal bladder tissues. The increased immunore-activity of

SHH pathway proteins was observed in samples derived from patients

with a high pathological stage, the presence of venous invasion and

lymph node metastasis. Patients with a positive SHH,

PTCH1 and GLI1 expression also exhibited poorer

disease-free survival rates, according to Kaplan-Meier analysis

(153). Further studies

suggested the prognostic value of the SHH pathway protein level in

bladder cancer. Nedjadi et al (154) revealed that a high SHH protein

immunoreactivity in urothelial bladder cancer tissues was

associated with the presence of lymph node metastasis; however, no

association was identified between SHH expression and other

clinicopathological parameters or patient survival. SHH

overexpression can be associated with the upregulation of MEIS2 (an

upstream SHH gene regulator) in bladder cancer lymph node

metastasis, as observed by Xie et al (155) in a clinical study on 104

patients with bladder cancer.

The significant role of SHH pathway proteins was

observed in the EMT of bladder cancer cells. An HTB-9 transitional

bladder cancer cell line, with acquired mesenchymal features due to

TGFβ1 stimulation (T-HTB-9), exhibited an overexpression of the

SHH and GLI2 genes at the mRNA and protein levels.

Furthermore, following incubation with cyclopamine, and GDC-0449,

SMO and GLI1-3 inhibitors, a decrease in the migration, invasion

and clonogenicity of T-HTB-9 cells was observed (156). This evidence suggested that

inhibitors of the SHH pathway may effectively decrease bladder

cancer invasive potential and may thus prove to be useful to

bladder cancer treatment. Islam et al (156) examined 22 specimens derived

from human bladder cancer. An elevated immunoreactivity of SHH,

GLI2, Ki-67 proliferation marker and N-cadherin (mesenchymal cell

marker), and a decrease in E-cadherin (epithelial cell marker),

were observed in high-grade tumors compared with low-grade tumors,

further confirming the participation of SHH signaling proteins in

the EMT of human bladder cancer cells (156). Another analysis concerning the

association between EMT and the SHH pathway was performed on

muscle-invasive T24 and 5637 bladder cancer and non-muscle-invasive

KK47 cell lines. The incubation of the cells with recombinant SHH

protein decreased the expression of E-cadherin and enhanced that of

N-cadherin and vimentin in all three cell lines. Cyclopamine was

found to inhibit cell proliferation and invasiveness; however, the

effect was more pronounced in T24 and 5637 cell lines. In

vivo studies on nude mice with induced bladder cancer revealed

a significant inhibition of muscle-invasive-derived tumor

development, which indicated the potential benefits of using SHH

pathway-targeted therapy in advanced stages of bladder cancers

(157). Of note, Kim et

al (158) found that the

CpG hypermethylation-induced decrease in SHH gene expression

in bladder cancer cells led to an increase in tumor invasiveness.

The lack of SHH ligand decreased the activity of SHH signaling in

stromal cells, inhibiting the expression of bone morphogenetic

proteins and ultimately stimulating bladder cancer progression

(158). Furthermore, the

pharmacological inhibition of DNA methylation inhibited the

initiation of invasive urothelial carcinoma at the premalignant

stage of progression, through the increase in SHH expression in

cancer cells (158). These

findings were not consistent with previously presented results;

thus, further research on the cell-to-cell interactions between

bladder cancer and stromal cells in bladder tumors would improve

the understanding of the molecular basis of the role of the SHH

pathway in bladder cancer (158).

8. SHH pathway in gynecological cancers

Cancers of the female reproductive tract include

OC, CC and fallopian tube, uterine, vaginal and vulvar cancers, as

well as gestational trophoblastic neoplasms, according to the AJCC

Cancer Staging Manual, 8th Edition (159). The involvement of the SHH

pathway in the latter has barely been studied since its discovery

(160). Ho et al

(160) focused on the

expression of Kif7 motor protein and GLI1-3 transcription factors,

and reported a strong downregulation of the GLI1-3 genes at

the mRNA level in 4 choriocarcinomas, as well as 50 hydatidiform

moles, compared with 19 normal placentas. Although it was proven in

that study that the overexpression of Kif7 in the

choriocarcinoma cell lines, JAR and JEG-3, suppressed cell

migration, the role of SHH in the development of gestational

trophoblastic neoplasms remains unclear (160). Furthermore, only one study

focused on SHH expression in vulvar squamous cell carcinoma (VSCC);

Yap et al (161)

performed semi-quantitative IHC of tissue specimens from 91 VSCC

cases for SHH, PTCH1 and GLI1 proteins. Although an increased

immunoreactivity of one or more of the assessed proteins was

reported, only the decreased expression of PTCH1 was

associated with an increased risk of developing a local disease

recurrence (161).

OC

OC ranks 8th in incidence and mortality among

cancers affecting women (18th and 14th in both sexes, respectively)

worldwide, with almost 300,000 cases and 185,000 deaths in 2018,

according to the GLOBOCAN data (8). Epithelial OC accounts for >90%

of all ovarian malignancies and is classified into five

histological subtypes: Serous, mucinous, endometrioid,

undifferentiated and clear cell subtypes (162), while OC advancement is based on

the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO)

staging. Molecular patterns of SHH upstream regulators in OC have

only been analyzed by a few studies.

One of the first studies on SHH pathway components

in OC was conducted by Levanat et al in 2004 (163). Although an upregulation of

GL1 mRNA expression was not observed in a group of 11

ovarian fibromas and 15 ovarian dermoids, higher mRNA levels of

SMO and SHH were observed. A frequent mutation of the

PTCH1 gene was also identified in the majority of ovarian

fibromas, but it was not found to be associated with the expression

level of this gene (163).

Marchini et al (164)

observed the overexpression of ZIC2 in the malignant form of

epithelial OC (n=193), compared to low-malignant potential OCs

(n=39). In OC cell lines, ZIC2 overexpression was found to

increase the growth rate and foci formation of NIH3T3 cells and

stimulate anchorage-independent colony formation (164). The data on FOXA2

expression in OC are inconclusive: Salem et al (165) found that its lower mRNA levels

promoted OC tumorigenesis, while Peng et al (166) reported high FOXA2 levels in

OCs. Loss of heterozygosity of the PTCH1 gene was a frequent

observation in OC (167,168),

suggesting that the mechanism of SHH pathway activation in OC is

type I. Moreover, the studies regarding somatic mutations in SHH

signaling components counted 14% frequency in a MyPathway study

(169).

Further studies identified the association between

SHH signaling and OC progression; Liao et al (170) observed the overexpression of

SHH and patched proteins (assessed by IHC in 80 patients with OC)

and GLI1 mRNA (quantified by qPCR in 37 OCs) in tumor

specimens, whereas no changes were observed in ovarian tissue. In

addition, the observed molecular alterations were associated with

the poorer outcome of OC patients. Liao et al (170) also performed a GLI1 ectopic

expression experiment on SKOV3 and OVCAR3 OC cell lines and

reported the upregulation of tumorigenesis-related genes (i.e.,

BCL2, VEGF and genes encoding vimentin and

E-cadherin). The incubation of SKOV3, OVCAR3 and OVCA433 cells with

KAAD-cyclopamine, an inhibitor of SMO protein, suppressed cancer

cell viability, induced apoptosis, and decreased the expression of

the aforementioned cancer-related genes (170). However, contrasting results

were obtained by Yang et al (171), who did not report higher levels

of SHH pathway components nor the target genes in 34 OC tumor

samples. Based on the SHH, PTCH1, GLI1,

HHIP, SMO and SUFU mRNA semi-quantification

results (assessed by PCR and qPCR for GLI1), as well as

patched 1, GLI1 and HHIP proteins (assessed by IHC), the results of

that study suggested infrequent involvement of the SHH pathway in

OC development (171). In a

study by Schmid et al (172), inconclusive results of the

expression of SHH signaling and target genes in OC were obtained.

In a group of 16 FIGO stage III serous tumors, various expression

levels of SHH genes (GLI1/2, PTCH1, SHH and

SMO; assessed by qPCR) were observed, while IHH and

PTCH2 genes were upregulated in the majority of cases

(172).

More recent data have confirmed, however, the

impact of the SHH pathway in the progression of OC; Ozretić et

al (97) analyzed SHH

pathway genes in 23 OCs, including 16 carcinomas (CA) and 7

atypical proliferative (borderline) tumors. However, higher mRNA

levels of GLI1 and SUFU were observed in OCs, and

SUFU levels were found to decrease with increasing FIGO

stages. Moreover, a strong positive correlation was observed

between the SMO and GLI1 mRNA levels. In the primary

culture of tumor cells obtained from a high-grade ovarian tumor

sample (FIGO IIIC), cyclopamine exerted an inhibitory effect on

cell proliferation, but only in the first 24 h, whereas GANT61

decreased the proliferation rates of both primary and SKOV-3 cell

lines after 72 h (97).

Furthermore, GANT61, unlike cyclopamine, led to the downregulation

of GLI2 transcription factor in the cells at the molecular level,

rendering it a more effective SHH signaling inhibitor in OC

treatment (97).

Recent studies have highlighted the importance of

GLI-regulated anti-apoptotic protein survivin (BIRC5) (97,173,174) and matrix metalloproteinase

(MMP)-7 (175) as putative

markers for OC progression. Zhang et al (175) reported a high immunoreactivity

of MMP-7 and GLI2 in tumor tissues from 95 OC patients, and the

high expression of MMP-7 protein was found to be associated with

poor patient outcomes. The association between the SHH pathway and

MMP-7 expression was proven by demonstrating that ectopic

stimulation of SHH in an SK-OV-3 OC cell line increased

MMP-7 expression (175).

BIRC5 is an anti-apoptotic protein that acts as a

negative regulatory protein that prevents apoptotic cell death; the

gene is highly expressed during fetal development and in cancer

tissues (176). Trnski et

al (173) and Vlčková et

al (174) analyzed the

association between BIRC5 gene activation and the SHH

pathway. The first team worked on A549 and the other experimented

on SKOV-3 OC cell lines. Based on BIRC5 promoter inactivation by

GANT61 rather than cyclopamine, Vlčková et al (174) proved that BIRC5 was regulated

by the GLI2 transcription factor. Trnski et al (173) further revealed, by the addition

of the GLI1 activator, that GLI3 was not associated with survivin

expression.

Recently, the associations between the SHH pathway

and CSC have been studied in high-grade serous OC (HGSOC) (177). Sneha et al (177) analyzed the effects of SHH

pathway inhibitors on cell viability and spheroid formation through

primary cultures of tumor cells from HGSOC and in nine OC cell

lines. The treatment of cells with SHH inhibitors reduced the

formation of spheroids with the higher efficacy of GANT61, compared

with LDE225 (sonidegib) and salinomycin. In a xenograft model, the

formation of tumors with an OVCAR3 origin was inhibited by GANT61

treatment. It was also found that the stemness marker, ALDH1A1, was

at least partially dependent on the SHH pathway (177). The association between ALDH1A1

and the SHH pathway through the inhibition of GLIs was also

observed in bladder (178) and

breast (179) cancer. In

conclusion, data have demonstrated that the SHH pathway plays an

important role in OC development with GLI1/2 downstream effectors

as the key points.

CC

The worldwide incidence and mortality numbers of CC

in 2018 were approximately 590,000 and 311,000, respectively, with

CC ranking fourth in both categories among other malignancies

(8). Although it is known that

the pathogenesis and progression of CC are associated with human

papillomavirus (HPV) infection, the involvement of the SHH pathway

has also been described. The study by Rojo-León et al

focused on the impact of HPV E6/E7 oncogenes on the SHH pathway in

transgenic mice that carry eight GLI1-binding sites bound to the

firefly luciferase gene (180).

An increased GLI1 expression was observed in the cervix and

skin either after exogenous estradiol or E6/E7 oncogene activation

(180). Chen et al

(181), using a microarray

assay, found an increased expression of GLI1, SMO,

SHH, PTCH1 and FOXM1 (GLI target gene) in 70

tumor CCs, compared to 10 normal cervical tissues; the expression

patterns of those genes were associated with either the clinical or

pathological progression of CC.

The majority of studies describing the role of the

SHH pathway in CC have been performed using CC cell lines. Vishnoi

et al (182) reported a

connection between E6/E7 oncoproteins and SHH activation by

analyzing HPV-16 positive SiHa CC cells. In SiHa cells, the SHH

components, GLI, SMO and PTCH1, were found to

be overexpressed, while their reduced expression was observed

following either the addition of cyclopamine or siRNA-mediated E6

gene silencing (182). Wang

et al (183)

demonstrated that, in a hypoxic environment, the GLI1 mRNA

level in HeLa cells was increased and was accompanied by an

enhanced invasion ability, whereas GLI1 silencing reversed

these effects, compromising the invasiveness of HeLa cells.

Furthermore, Wang et al (183) observed that the ectopic

increase of mir-129-5p resulted in the lower mRNA and protein

levels of ZIC2, SHH, GLI1 and GLI2, together with SHH target genes

CXCL1, VEGF and ANG2, as well as the inhibition of tumor formation

in a mouse xenograft model. These results indicated that mir-129-5p

may be a promising target for CC treatment (184). In combination, the available

evidence suggested that the SHH pathway is involved in CC

progression.

9. SHH pathway in cancers of the male

reproductive system

The testis, penis and prostate may be affected by

neoplastic transformation, leading to cancers of the male

reproductive system, according to AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 8th

Edition (159). Although DHH is

involved in the differentiation of peritubular myoid cells and

consequent formation of the testis cord (185), while the SHH is involved in

penile development (186),

there are no data available on the SHH pathway during testicular or

penile tumorigenesis, at least to the best of our knowledge.

PC

Prostate gland tumors rank 2nd in the worldwide

cancer incidence among males (4th among all cancers in both sexes)

with almost 1.3 million new cases, and 5th in worldwide cancer

mortality in males (8th among all cancers in both sexes) with

~359,000 deaths in 2018 (8). The

majority of PCs are associated with defective DNA damage repair

molecules, while androgen receptor (AR) signaling also plays an

important role in PC pathogenesis, particularly in metastasized

cases (187). During fetal

life, the AR and SHH pathways play a crucial role in the

development of the prostate gland (188,189). Le et al (188) reported that, during prostate

development, growth and regeneration, both pathways are

indispensable; the AR signaling pathway is superior since, in the

murine in vivo model, the expression of AR was essential for

urogenital mesenchymal and epithelial cell differentiation, even if

the cells overexpressed GLI1.

Yamamichi et al (190) reported that in PC epithelial

cells (LNCap) and prostate fibroblast cell lines, normal (NPF) and

PC-associated (CPF), dihydrotestosterone (DHT) enhanced cell

proliferation in all cell types while the inhibition of SHH

signaling by cyclopamine decreased this rate in CPF cells only. The

activation of both androgen and SHH signaling enhanced EMT,

accelerating PC development, while cyclopamine blocked cancer

progression. In addition, DHT (but not SHH) induced the expression

of osteonectin, and a high GLI1 expression and stromal

osteonectin expression (as found by IHC) in tumor tissues from 25

patients with PC, were associated with PSA recurrence (190).

A recent study by Zhang et al (191) analyzed the AR and SHH pathways

in PC clinical cases. In a large group of 443 patients with primary

PC and 96 with benign prostatic hyperplasia, the increased

immunoreactivity of SHH protein was observed in more aggressive

tumors (Gleason score of >7), which was much higher in

AR-positive than in AR-negative cancer. Furthermore, SHH was

overexpressed in high-grade PC and positively correlated with the

expression of both GRP78 (the molecule involved in endoplasmic

reticulum stress response) and AR; this suggested that the

assessment of SHH protein could be beneficial as a prognostic

factor in PC, since SHH overexpression in all patients with PC with

AR+ tumors was associated with a shorter

disease-specific survival (191). Describing the expression

pattern of SHH pathway components in PC, Tzelepi et al

(192) analyzed SHH, SMO, PTCH,

GLI1, VEGF, CD31 and ki67 protein levels using western blot

analysis, IHC and tissue microarrays in large groups consisting of

141 hormone-naive primary PC and 53 castrate-resistant bone marrow

metastases, compared to 119 prostate non-neoplastic peripheral

zone. First, they observed the crosstalk between prostate cells in

healthy tissues; SHH and PTCH1 were primarily expressed in

epithelial and stromal cells, respectively, while SMO and GLI1 were

expressed in both epithelial and stromal cells. This observation

suggested paracrine signaling between epithelial (donor) and

stromal (acceptor) cells, followed by SHH pathway activation in all

cells (192). The expression

pattern was continued in primary PCs with higher SHH and SMO

protein levels in PC epithelial cells than those in the

non-neoplastic peripheral prostate zone. Of note, in PC metastases,

a higher PTCH1 expression was observed in epithelial cells compared

with that in stromal cells, while the expression of SHH and

GLI1 did not differ between the two (192). These results suggested an

alteration in the mechanisms of SHH signaling in PC and its

metastases, as well as its involvement in PC development.

In combination, the available data demonstrate that

the SHH pathway plays an important role in PC development,

indicating that SHH pathway-targeting drugs should be introduced

into PC treatment. Indeed, two phase I and one phase II clinical

trials that used LDE225, vismodegib or itraconazole (SMO

inhibitors) have been performed (193-195). Although decreased levels of

GLI1 were recorded in tumor tissues from patients treated with

vismodegib or LDE255, there was no apparent effect on clinical

activity. In addition, vismodegib caused side-effects, such as

fatigue or nausea, and LDE255 increased the prostate-specific

antigen (PSA) serum level (193,194). Treatment with itraconazole, an

FDA-approved antifungal drug, demonstrated that a high dose (600

mg) may be beneficial for progress-free survival. However, such a

dose has been found to cause hypokalemia (195,196). In summary, drugs targeting the

SHH pathway should be further evaluated as an additional modality

of PC treatment, given that more studies associated with the

interactions between stromal and PC cells in relation to the AR and

SHH signaling pathways are being carried out.

10. Conclusions and future perspectives

The SHH signaling pathway was identified 40 years

ago, and since then, the understanding of the functions of and

cellular associations between its components has been considerably

increased. Although the SHH-PTCH-SMO-GLI cellular cascade has been

widely discussed in several studies, the aim of the present review

was to also describe the upstream genetic regulation of the SHH

ligand expression. Of note, the activation of SHH biosynthesis

relies on proteins with transcription factor properties that are

involved in fetal development, tissue renewal and remodeling in the

adult body. Indirectly, SHH is regulated by miRNAs, which also

interact with other cellular pathways. GLIs are the main downstream

effectors of SHH signaling and their transcriptional activity

depends mainly on their release from the SUFU-KIF7 complex

triggered by the SMO receptor. Since the upregulation of the SHH

pathway, particularly GLIs, is associated with the progression of

several types of cancer, specific drugs inhibiting this signaling

have been developed. Most of them target the SMO receptor; however,

due to frequent SMO/PTCH1 mutations that may lead to drug

resistance, GLIs can be also activated through other cellular

pathways.

In the present review, the focus was placed on

analyzing the SHH pathway components in the kidney, urinary

bladder, OC, CC and PC. In all these cancers, including sex

hormone-dependent ovarian and prostate tumors, deregulations of SHH

pathway components were observed by several authors. Furthermore,

the interaction between viral proteins and SHH signaling molecules

has been noted in cervical types of cancer, mostly originating from

HPV infection. The alterations of the SHH pathway components in

these cancers have often been found to be associated with either

the clinical or pathological status of patients. Despite these

findings, the SHH components have not yet been considered as