1. Introduction

Metabolic syndrome is a combination of symptoms,

including abdominal obesity, atherogenic dyslipidemia,

hypertension, insulin resistance characterized by hyperglycemia,

proinflammatory state and prothrombotic state [National Cholesterol

Education Programs Adult Treatment Panel III report (ATP III)]

(1). The comorbidities associated

with the metabolic syndrome include cardiovascular disease, type 2

diabetes and other diseases including polycystic ovary syndrome,

fatty liver, asthma, cholesterol gallstones, sleep disturbances and

several cancers (1-3).

Abdominal obesity is characterized by a waist

circumference of >102 cm in men and >88 cm in women (1). Obesity is often caused by excessive

food intake and a lack of physical activity, resulting in an energy

imbalance, where energy intake is greater than energy expenditure,

leading to an elevated body mass index (BMI >30

kg/m2) and increased body fat mass (4,5).

It has been linked to increased proinflammatory states due to

chronic adipose tissue inflammation, leading to the development of

insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes (6). Atherogenic dyslipidemia is

manifested by increased plasma triglyceride levels, a high

concentration of plasma low-density lipoprotein (LDL)-cholesterol

(LDL-C) and low level of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol

(HDL-C), increasing the risk of cardiovascular disease (1). Hypertension is caused by a high

blood pressure where systolic blood pressure of is >130 mm Hg

and diastolic >85 mm Hg (1).

Insulin resistance occurs when fasting blood glucose level is ≥110

mg/dl (1). The World Health

Organization criteria for metabolic syndrome is the presence of

insulin resistance accompanied with any two of the other symptoms

of metabolic syndrome including increased waist/hip ratio and

increased urinary albumin excretion rate (7).

Currently, there are several pharmacological drugs

available for obesity treatment, including orlistat (Xenical) and

sibutramine; however, these drugs have several undesirable side

effects including mood changes, and gastrointestinal or

cardiovascular complications (8).

Plant-derived natural compounds have been revealed to demonstrate

positive effects on obesity, diabetes, renal and cardiovascular

disease (9). Thus, natural

products from plants have been suggested as a better alternative

for treating obesity and cardiometabolic syndrome (10).

α-mangostin is a xanthone by chemical structure

(Fig. 1), and one of the

significant phytochemical constituents in the tropical fruit

Garcinia mangostana (11-13). It has also been found in other

Garcinia (G.) species, including G. dulcis

(14), G. staudtii

(15) G. merguensis

(16) and G. cowa

(17), and in the perennial

tropical trees Cratoxylum cochinchinense (18), Cratoxylum arborescens

(19), Cratoxylum formosum

(20) and Pentadesma

butyracea (21). In G.

mangostana, α-mangostin is mainly found in the fruit pericarp

(12,22) which has been traditionally used to

treat several health conditions, including abdominal pain,

diarrhea, dysentery, wound infections, suppuration, and chronic

ulcers (23).

Previous reports have demonstrated that α-mangostin

exerts numerous health-promoting effects including anti-obesity

(24), antidiabetic (25), antioxidant (26), anti-inflammatory (27), antiallergic (28), anticancer (29), neuroprotective (30), hepatoprotective (31), cardioprotective (32), antimicrobial (33) and antifungal (34) properties. Although previous

reviews have summarized the health properties of α-mangostin

(30,35-40), limited information is available on

its molecular mechanisms in cardiometabolic disease. Hence, the

present review aimed to elucidate the potential molecular effects

of α-mangostin on metabolic syndrome parameters, observed in

biological models of cardiometabolic syndrome and other related

models.

2. Anti-obesity effects of α-mangostin

The anti-obesity effects of α-mangostin and

α-mangostin-rich materials have been extensively studied. Various

doses of purified α-mangostin compound have been revealed to reduce

body weight in animal models (mice and rats) even when treated with

G. mangostana fruit pericarp/rind/peel or flesh (12,41-46).

Kim et al (25) suggested that the treatment of high

fat-fed C57BL/6 mice with 50 mg/kg of α-mangostin per day reduced,

their body weight, cholesterol levels, serum triglycerides, and

increased adiponectin levels, also noting that the treatment

reduced epididymal adipose tissue size and reduced the crown like

structures in adipocytes. Choi et al (24) also stated that an α-mangostin dose

of 50 mg/kg per day in C57BL/6 mice reduced body weight, total

cholesterol (TC), LDL-C and free fatty acids in mice fed a high-fat

diet. Furthermore, they found that α-mangostin increased the

expression of hepatic peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ

(PPARγ), sirtuin (SIRT) 1, AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and

retinoid-X-receptor alpha, suggesting that the anti-obesity and

hepatoprotective effects of α-mangostin are mediated via the

SIRT1-AMPK and PPARγ pathways in mice with obesity induced by a

high fat diet. Li et al (42) treated aged mice with an

α-mangostin dose of 25 and 50 mg/kg per day and observed a

reduction in body weight, epididymal and inguinal white adipose

tissue, serum concentrations of triglycerides, LDL-C and TC. The

treatment increased phosphorylated (p-) protein kinase B (p-AKT)

expression in epididymal white adipose tissue (42).

The hallmark of dyslipidemia in obesity includes

increased triglycerides and free fatty acids, low HDL-C or slightly

increased LDL-C (47). John et

al (12) demonstrated that

the administration of an α-mangostin dose of 168 mg/kg per day from

G. mangostana rind to rats on a high fat/carbohydrate diet

decreased their body weight gain and visceral fat accumulation

accompanied by reduced adipocyte size and plasma triglycerides. In

a monosodium glutamate, high-calorie diet-induced male Wistar rat

model, Abuzaid et al (41)

noted that the administration of 200 and 500 mg/kg G.

mangostana extract per day, equivalent to a dose of 60 and 150

mg/kg α-mangostin per day, respectively, caused a reduction in body

weight gain, which was associated with a reduction in fatty acid

synthase activity in adipose tissue and serum. In the study by

Mohamed et al (46), the

treatment of Balb/c mice with high-fat non-alcoholic fatty liver

disease (NAFLD) and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) with 50

mg/kg α-mangostin per day also reduced body weight gain and free

fatty acid levels.

Chae et al (45) examined the effect of the 50 and

200 mg/kg dose of G. mangostana extract per day, equivalent

to a dose of ~12.5 mg/kg and 50 mg/kg α-mangostin per day,

respectively, in C57BL/6 mice fed a high-fat diet. The treatment

decreased body weight and visceral fat (epididymal, inguinal and

mesenteric), although not retroperitoneal fat. The treatment also

improved lipid metabolism by reducing triglycerides, LDL-C, TC at

both concentrations. Protein expression analysis revealed that

α-mangostin activated the AMPK and SIRT-1 pathways, aiding in body

weight reduction. In the 200 mg/kg per day group, the PPARγ levels

decreased, suggesting a reduction of lipogenesis in adipocyte

differentiation and an increase in carnitine palmitoyl transferase

1a (CPT1a), which in turn promotes fatty oxidation (45). In the study by Tsai et al

(43) rats fed a high fat-diet

were treated with 25 mg/day of mangosteen pericarp extract for 11

weeks. A decrease in body weight gain, plasma free fatty acids and

hepatic triglyceride accumulation was observed. In another study,

Sprague-Dawley rats fed a high-fat diet were treated with dried

G. mangostana flesh doses of 200, 400, 600 mg/kg per day and

exhibited a reduced body weight, food intake, plasma cholesterol

and TC levels (44). However, in

that study, the amount of α-mangostin was not quantified (44).

In vitro studies using α-mangostin have

demonstrated similar conclusions as in vivo studies. The

treatment of breast cancer cell lines with α-mangostin (1-4

µM) led to the inhibition of fatty acid synthase (FAS)

expression and activity (29). In

another study, 3T3-L1 pre-adipocytes treated with α-mangostin

exhibited a concentration-dependent reduction in intracellular fat

accumulation up to 44.4% relative to methylisobutylxanthine,

dexamethasone, insulin (MDI)-treated control cells at a 50

µM concentration. PPARγ expression and pre-adipocyte

differentiation were suppressed by α-mangostin (48). Additionally, the use of

α-mangostin resulted in leptin production increase (48) and exerted potent inhibitory

effects against pancreatic lipase (49).

The treatment with G. mangostana pericarp,

rich in α-mangostin, demonstrated similar effects across studies.

John et al (12), Li et

al (42) and Chae et

al (45) observed reduced

white adipose tissue deposition, TC, free fatty acids,

triglyceride, and visceral fat accumulation. Li et al

(42) and Chae et al

(45) additionally observed

reduced LDL-C with pericarp treatment. The treatment has also been

previously reported to increase hepatic AMPK and SIRT1 (24) and reduce PPARγ expression

(45). AMPK activity maintains

cellular energy storage by activating catabolic pathways that

generate ATP, primarily by increasing oxidative metabolism and

mitochondrial biogenesis, while 'switching off' anabolic pathways

that utilize ATP (50).

In principle, the reduction of body weight by

α-mangostin is associated with a decrease in adipose tissue size

and accumulation, decreased fatty acid synthase activity, decreased

intracellular fat accumulation, increased adiponectin expression,

increased fatty acid oxidation via an increased CPT1a expression,

the increased activation of the SIRT1-AMPK, and reduced PPARγ

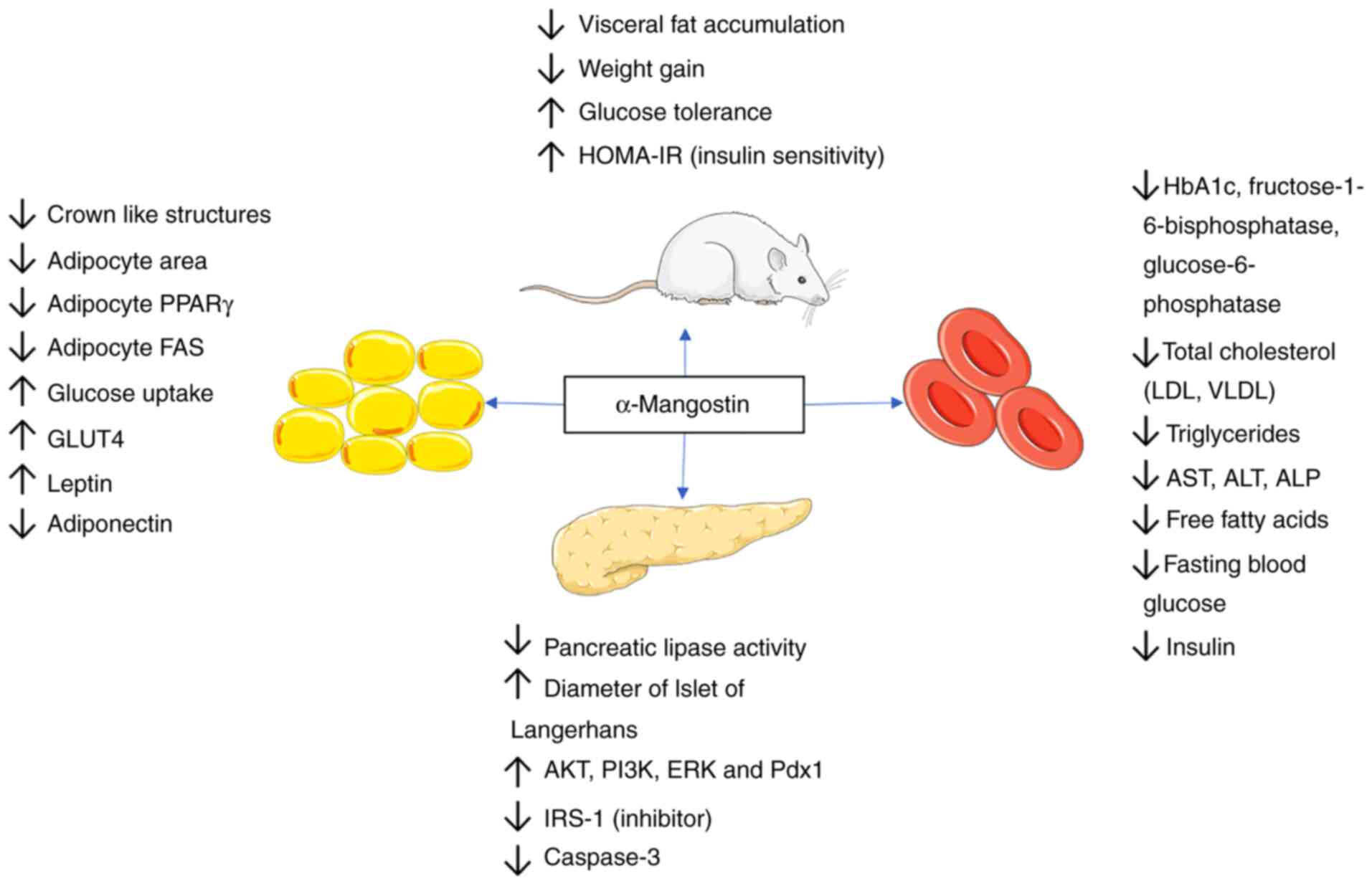

pathways (Fig. 2 and Table I). This may suggest that the main

methods of action in obesity reduction by α-mangostin occur through

fatty acid metabolism and adipose tissue biology as the major depot

for fatty acids, requiring further elucidation.

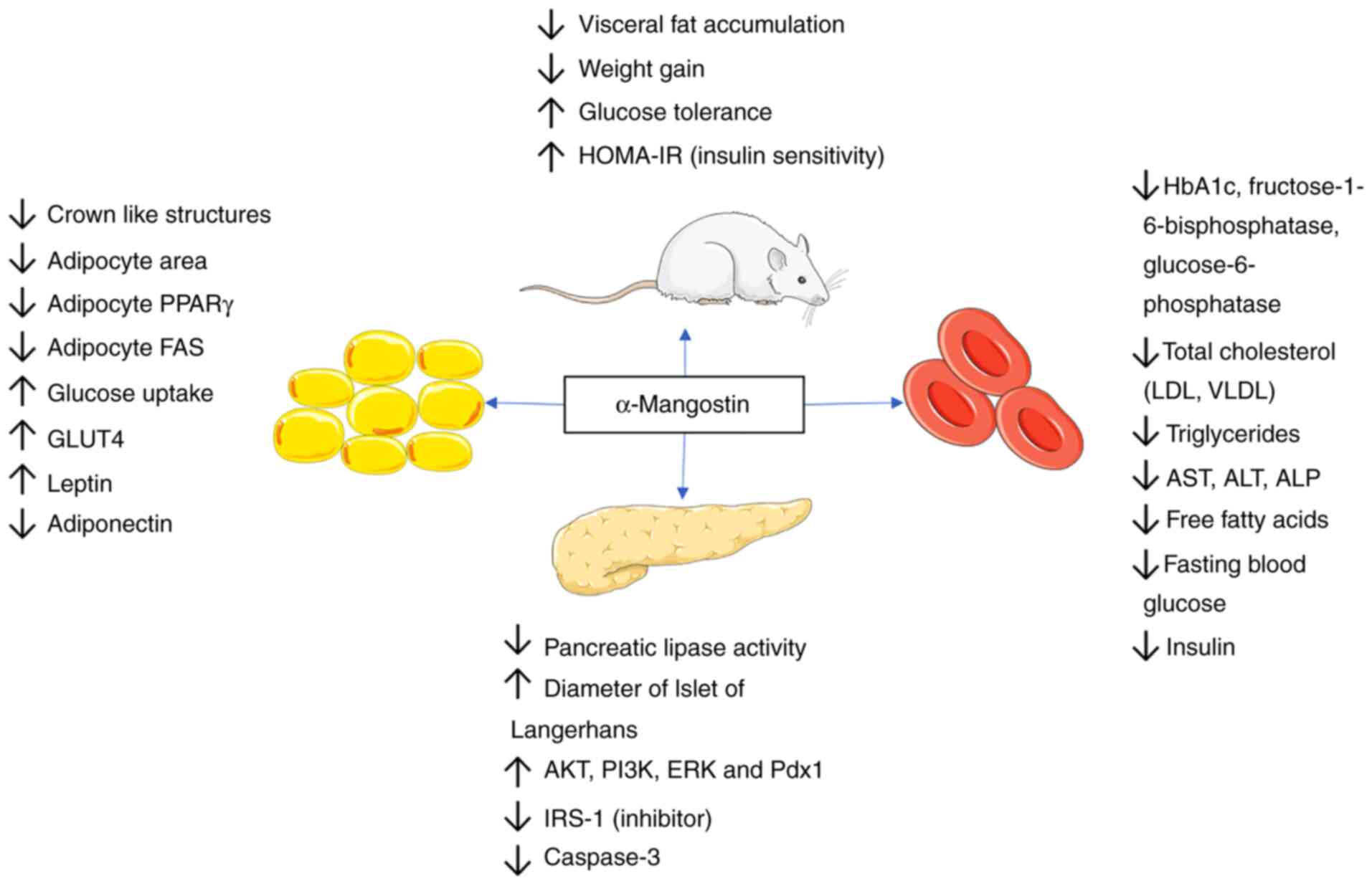

| Figure 2Anti-obesity and antidiabetic effects

of α-mangostin. The anti-obesity effects of α-mangostin are

mediated via the modulation of adipose tissue biology, reduction in

visceral fat accumulation and inhibition of fatty acid synthase.

Its antidiabetic effects are mediated through an improvement in

insulin sensitivity and glucose tolerance, increased pancreatic

lipase activity, increased glucose transporter activity, the

increased stimulation of insulin receptor and the increased

phosphorylation of the PI3K, AKT and ERK signaling cascades. PPARγ,

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ; GLUT4, glucose

transporter 4; HOMA-IR, homeostatic model assessment for insulin

resistance; Pdx1, pancreatic and duodenal homeobox 1; LDL,

low-density lipoprotein; VLDL, very low-density lipoprotein; AST,

aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; ALP,

alkaline phosphatase. |

| Table IAnti-obesity effects of

a-mangostin. |

Table I

Anti-obesity effects of

a-mangostin.

| Authors | Source of

α-mangostin | Model: in

vitro/in vivo | Dosage and duration

of treatment | Mechanisms of

action of anti-obesity effects | (Refs.) |

|---|

| John et

al | G.

mangostana rind | Wistar rats (High

carbohydrate, high fat) | 168 mg/kg per day 8

weeks | • ↓Weight

gain

• ↓Visceral fat accumulation

• ↓Adipocyte area

• ↓Plasma triglyceride

• ↓FFA | (12) |

| Taher et

al | G.

malaccencis | 3T3-L1

preadipocytes | 10, 25, and 50

µM of α-mangostin 2 days | • ↓Intracellular

fat accumulation

• ↓PPARγ expression | (48) |

| Chae et

al | G.

mangostana | In vitro pancreatic

lipase assay model | IC50=5.0

µM | • ↓Pancreatic

lipase activity | (49) |

| Abuzaid et

al | G.

mangostana pericarp | Wistar rats | 200 mg/kg body

weight per day 500 mg/kg body weight per day (~60 mg/kg per day and

150 mg/kg α-mangostin per day) 9 weeks | • ↓Body

weight

• ↓Fatty acid synthase (adipose tissue/serum) | (41) |

| Chang et

al | Mangosteen

concentrate drink | Sprague-Dawley

rats | 13 mg/day 6

weeks | • ↓Fasting plasma

triglyceride

• ↓Total cholesterol

• ↓Hepatic CAT | (107) |

| Tsai et

al | Mangosteen pericarp

extract | Sprague-Dawley

rats; rat primary hepatocytes | 25 mg/day-rat 11

weeks 10-30 µM-rat hepatocytes 24 h | • ↓Plasma

FFA

• ↓Weight gain | (43) |

| Muhamad Adyab et

al | G.

mangostana flesh | Sprague-Dawley

rats | 200-600 mg/kg

(α-mangostin concentration not detailed) 7 weeks | • ↓Weight

gain

• ↓Plasma LDL-C

• ↓Total cholesterol | (44) |

| Chae et

al | G.

mangostana peel | Male C57BL/6

mice | 50 and 200 mg/kg

per day (~12.5 and 50 mg/kg of α-mangostin per day) 45 days | • ↓Weight

gain

• ↓AST and ALT

• ↓LDL cholesterol

• ↓Total cholesterol

• ↓Triglyceride

• ↓FFA, ↓glucose

• ↓Visceral fat accumulation

• ↓PPARγ

• ↑Hepatic SIRT1 and AMPK | (45) |

| Mohamed et

al | G.

mangostana extract | Balb/c mice | Group III-50 mg/kg

of α-mangostin per day 16 weeks | • ↓Weight

gain

• ↓FFA | (46) |

| Kim et

al | Purified

α-mangostin | C57BL/6 mice

RAW264.7 macrophages Mesenteric adipose tissue culture | 50 mg/kg per day 12

weeks 25 µM/ml | • ↓Body

weight

• ↓Cholesterol

• ↓Serum triglyceride

• ↑Adiponectin

• ↓Serum ALT

• ↓Crown-like structures (adipocytes)

• ↓Epididymal adipose tissue size | (25) |

| Li et

al | Purified

α-mangostin | MCF-7, estrogen

receptor-positive cells, MDA-MB-231, estrogen receptor-negative

cells | 1, 2, 3, 4

µM 24 h | • ↓FAS

expression

• ↓Intracellular FAS activity | (29) |

| Li et

al | Purified

α-mangostin | Mouse derived

RAW264.7 macrophage 3T3-L1 preadipocytes Male C57BL/6J | 10 mg/kg per day

(inflammation mice) 5 days 25 and 50 mg/kg per day 8 weeks (aged

mice) | • ↓Weight, indexes

eWAT and iWAT

• ↑Insulin sensitivity (HOMA-IR), p-AKT level

• ↓Total cholesterol, triglyceride, LDL-cholesterol

• ↑HDL-C | (42) |

| Choi et

al | Purified

α-mangostin | Male CB57L/6

mice | 50 mg/kg per day 6

weeks | • ↓Weight

gain

• ↓FFA

• ↓Total cholesterol

• ↓LDL-C

• ↑Hepatic PPARγ,

SIRT1, AMPK and RXRα | (24) |

3. Antidiabetic effects of α-mangostin

Diabetes is characterized by insulin resistance and

hyperglycemia, and is associated with hyperlipidemia. The main

hallmarks of diabetes include insulin resistance and pancreatic

β-cell dysfunctions (51). In

animal studies, treating high fat-fed mice with a dose of 50 mg/kg

α-mangostin per day has been reported to improve glucose tolerance,

increase insulin sensitivity as evaluated by the homeostatic model

assessment for insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), increase adiponectin

levels and increase the phosphorylation levels of insulin receptor

substrate 1 (IRS-1) and AKT in both liver and adipose tissues

(25). This indicates that

α-mangostin affects insulin signaling in both tissues.

By using rat pancreatic INS-1 cells, Lee et

al (52) revealed that the

use of α-mangostin at a concentration between 1-10 µM

increased insulin secretion in a concentration-dependent manner in

cells grown under high glucose conditions (16.7 mM glucose) without

inducing cytotoxicity, which was maintained for 48 h. Additionally,

it was further demonstrated that high glucose levels reduced the

phosphorylated or active insulin receptor (p-IR), phosphoinositide

3-kinases (PI3K), p-AKT, protein kinase R-like endoplasmic

reticulum kinase and pancreatic and duodenal homeobox 1 (Pdx1)

protein levels, but increased the expression of IRS-1

phosphorylated at Ser 1101 (p-IRS-1Ser1101) in INS-1 cells

(52).

Reduced p-IR levels indicate a response to the

increased serine phosphorylation of IRS-1 proteins (53). The phosphorylation of IRS proteins

on serine residues negatively regulates IRS signaling (54,55). IRS-1 acting downstream of pIR,

recruits p85, a regulatory subunit of PI3K, and activates the

PI3K/AKT pathway (56). This

pathway activates PDK kinases, which phosphorylate AKT and permit

its translocation to the nucleus, activating genes involved in

glucose intake and blocking FOXO genes, inducing gluconeogenesis

(57). High glucose levels

essentially shut down insulin signaling by altering IR

phosphorylation. This shutdown mechanism is attributed to the

increased proteasome degradation of IRS proteins, the failure to

recruit p85 to IRS proteins, thereby not activating the PI3K/AKT

signaling pathway (54).

Treatment with a 5 µM concentration of

α-mangostin, has been reported to protect against these effects, by

reducing the inhibitory pIRS-1Ser1101, and restoring IR signaling

as evidenced by increased PI3K, AKT and Pdx1 proteins (52). The loss of Pdx1 has been revealed

to be associated with a decrease in b cell mass. It should be noted

that hyperinsulinemia lowers the expression of IRS1 family of

proteins in both cultured cells and mouse tissues, which has been

linked to insulin resistance in animal models. The mechanism has

been largely attributed to increased degradation (by

ubiquitination) and decreased synthesis of IRS proteins (54,55).

Streptozotocin (STZ) is commonly used to induce type

1 diabetes in animal models, which induces oxidative stress in

pancreatic β-cells, resulting in the increased activation of p38

MAPKs, JNK proteins and cleaved caspase-3 protease which causes

hyperglycemia, the increased generation of reactive oxygen species

(ROS), osmotic stress, proinflammatory cytokine secretion and

apoptosis (52,58). However, co-treatment with

α-mangostin (5 µM) has been found to reduce caspase-3

protease levels, reduce the apoptosis of the cells, and increase

p-PI3K-AKT levels, demonstrating the protective effect of this

compound in the presence of STZ (52). The antiapoptotic properties of

α-mangostin could be attributed to its anti-oxidant properties, as

described in a following section. The effects of α-mangostin in

reducing pro-apoptotic proteins levels, particularly caspase-3

levels have been also observed in a previous study in human

umbilical vein endothelial cultured cells (59), where α-mangostin led to an

increase in Bcl-2, an antiapoptotic protein, and a reduction in

Bax, a pro-apoptotic protein, in a concentration-dependent manner

(59).

Hyperglycemia also induces ROS generation via a

series of complex processes involving diacylglycerol, protein

kinase C and NADPH-oxidase (60).

ROS production eventually leads to tissue damage, which decreases

insulin production as pancreatic β-cells are damaged over time,

leading to hyperglycemia. These effects are attenuated by

α-mangostin, which protects the pancreatic β-cells from damage and

restores damaged pancreatic cells to allow for optimal insulin

release (59,61,62).

In another in vivo study, histological

samples of mice with STZ-induced diabetes treated with α-mangostin

exhibited a restored diameter of islets of Langerhans (61), thereby improving insulin

secretion. Jariyapongskul et al (63), who studied the effects of

α-mangostin on hyperglycemia induced ocular hypoperfusion retinal

leakage in rats, revealed that α-mangostin treatment significantly

improved ocular flow and reduced leakage in rats, by reducing

malondialdehyde (MDA) levels and lipid peroxidation in the retina.

Hyperglycemic tissues have been shown to exhibit increased levels

of MDA and advanced glycation end-products (AGEs). MDA is an end

product of lipid peroxidation prevalent in hyperglycemia due to

increased free radicals (63).

AGEs are involved in the pathogenesis of diabetes-related

complications, including cardiomyopathy, retinopathy and

nephropathy (64). At a 25

µM concentration, α-mangostin was found to reduce the

production of AGEs (65). In

another study, the treatment of mice with STZ-induced diabetes with

α-mangostin resulted in decreased glycated hemoglobin levels and

reduced key gluconeogenic enzymes fructose-1-6-bisphosphatase and

glucose-6-phosphatase lowering glucose production (66).

A pilot study previously investigated the effects of

mangosteen supplement (400 mg, once per day) in obese female

patients with insulin resistance (67). In that study, Watanabe et

al (67) revealed that the

treatment significantly improved insulin sensitivity (HOMA-IR)

along with a reduction in insulin levels, improved HDL-C and

lowered high-sensitivity C-reactive protein levels.

In general, treatment with α-mangostin or a diet

rich in α-mangostin in various obese and diabetic rat models, In

vitro studies and human studies has revealed that the compound

can improve the markers of diabetes by lowering fasting blood

glucose concentration, lowering insulinemia, increasing glucose

tolerance and increasing insulin sensitivity, as measured by

HOMA-IR, and increasing glucose uptake. The treatment with

α-mangostin promotes glucose uptake by increasing the expression of

glucose transporters in tissues, including glucose transporter

(GLUT)4 in adipose tissues, adipocytes, cardiac tissues, and

skeletal muscles and GLUT2 in hepatic tissues (25,68). Furthermore, α-mangostin may

stimulate insulin release in the pancreatic, liver and adipose

tissues by activating IRs and increasing the phosphorylation of

PI3K, AKT and ERK signaling cascades (25,52). These observations could explain

the increased glucose uptake and plasma glucose level reduction in

cells or animals treated with α-mangostin. A summary of the

mechanism of α-mangostin is presented in Fig. 2 and Table II.

| Table IIAntidiabetic effects of

a-mangostin. |

Table II

Antidiabetic effects of

a-mangostin.

| Authors | Source of

α-mangostin | Model In

vitro/in vivo | Dosage and

duration | Mechanisms of

action of anti-diabetic effects | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Kim et

al | Purified

α-mangostin | C57BL/6 mice

RAW264.7 macrophages Mesenteric adiposetissue culture | 50 mg/kg per day 12

weeks 25 µM/ml 24 h | • ↑Gucose

tolerance

• ↑HOMA-IR (insulin sensitivity)

• ↑p-AKT

• ↑p-IRS-1

• ↑GLUT4 (adipose)

• ↑GLUT2 (liver) | (25) |

| Taher et

al | G.

malaccencis | 3T3-L1

preadipocytes | 10, 25 and 50

µM of α-mangostin 2 days | • ↑Glucose uptake

(1, 25 µM only)

• ↑GLUT4 (adipocyte)

• ↑Leptin | (48) |

| Jiang et

al | Purified

α-mangostin | C57BL/KsJ diabetic

(db/db) mice Primary aortic endothelial cells | 10 mg/kg/d, i.p.;

mice 12 weeks 15 µM α-mangostin; cell culture 24 and 48

h | • ↓Fasting blood

glucose

• ↓Insulin

• ↓Ceramide and aSMase signaling and accumulation | (79) |

| John et

al | G.

mangostana rind | Wistar rats | 168 mg/kg per day 8

weeks | • ↑Glucose

tolerance | (12) |

| Lazarus et

al | α-mangostin

compound | Wistar rats | 100, 200 mg/kg per

day 8 weeks | • ↑Insulin

sensitivity (HOMA-IR)

• ↑GLUT4 (skeletal muscle) expression

• ↓STZ-induced weight loss | (108) |

| Ratwita et

al | α-mangostin

compound | Wistar rats

adipocytes (WAT) | 5, 10, 20 mg/kg day

21 days 3.125 mM; 6.25 and 25 mM (cell culture)/48 h | • ↑Glucose

tolerance

• ↑GLUT4 (adipocytes)

• ↑GLUT4 (cardiac) | (68) |

| Luo and Lei | α-mangostin | Human umbilical

vein endothelial cells | 5, 10, and 15

µM of α-mangostin Effects noted at 15 µM 24 h | • ↓Glucose induced

cell apoptosis

• ↓Pro-apoptotic proteins

• ↑Anti-apoptotic proteins | (59) |

| Soetikno et

al | α-mangostin | Male Wistar

rats | 100 and 200 mg/kg,

8 weeks | • ↑Insulin

sensitivity

• ↓Lipid profiles (LDH)

• ↓Fasting blood glucose | (98) |

| Jariyapongskul

et al | Purified, extracted

α-mangostin | Male Sprague-Dawley

rats | 200 mg/kg 8

weeks | • ↑Insulin

sensitivity

• ↓Fasting blood glucose

• ↓Blood cholesterol and triglycerides

• ↓TNF-α

• Re-establishes ocular blood flow and reduces retinal blood

leakage | (63) |

| Husen et

al | α-mangostin | Male BALB/C

mice | 2, 4 and 8 mg/kg

per day 14 days | • ↓Fasting blood

glucose

• ↓Blood cholesterol

• ↑Diameter of Islet of Langerhans | (61) |

| Lee et

al | α-mangostin

extracted and purified | Rat insulinoma,

INS-1 cells (store and secrete insulin) | 1, 2.5 and 5

µM 1 h | • ↑Insulin

secretion after glucose stimulation

• ↑Active insulin receptor

• ↑AKT, PI3K, ERK and Pdx1

• ↓IRS-1 (inhibitor)

• ↑Protection of INS-1 cells in presence of damaging

chemicals

• ↓Pro-apoptotic caspase 3 | (52) |

| Kumar et

al | α-mangostin

compound |

Streptozotozin-induced diabetes in Wistar

rat | 25, 50 and 100

mg/kg 56 days Toxicity test up to 1,250 mg/kg; 48 h | • ↓Blood

glucose

• ↓Glycated hemoglobin, fructose-1-6-bisphosphatase,

glucose-6-phosphatase

• ↓Total cholesterol (LDL, VLDL)

• ↓Triglycerides

• ↓AST, ALT, ALP

• ↓Structural renal and hepatic damage

• ↓IL-6, CRP, TNF-α concentrations | (66) |

| Usman et

al | α-mangostin | Male Sprague-Dawley

rats | Determined

IC50 | • ↑Potential to

lengthen α-mangostin release

• ↓Hyperglycemia | (158) |

| Watanabe et

al | G.

mangostana extract | Obese female

patients with insulin resistance | 400 mg/day

26-week | • ↓Insulin

levels

• ↓HOMA-IR

• ↓HsCRP

• ↑HDL-C | (67) |

4. Anti-steatotic and hepatoprotective

effects of α-mangostin

The use of α-mangostin and products rich in

α-mangostin from G. mangostana peel have been extensively

studied in both cell culture and rodent models of hepatic diseases.

G. mangostana peel has been revealed to decrease hepatic fat

vacuole accumulation (12) and

reduce hepatic triglyceride accumulation (43). The infusion of G.

mangostana peel decreases hepatic structural damage induced by

hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) (69). The ability of G. mangostana

peel to improve liver morphology has also been reported by Hassan

et al (70), John et

al (12), Yan et al

(71), and Fu et al

(72) in various hepatic disease

models.

The improvement in hepatic structure has been

associated with improved liver function tests indicated by reduced

levels of aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine

aminotransferase (ALT) (70,72,73). The reduction in liver fibrosis has

also been observed following treatment with G. mangostana

peel (12,73). Mangosteen peel extract (doses of

250 and 500 mg/kg per day) administration in a

thioacetamide-induced hepatoxicity rat model, prevented the

development of liver changes, decreased fibrosis through reduced

expression of α smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) and transforming growth

factor β1 (TGF-β1) genes (73).

Acute and chronic liver injury activate TGF-β1 from the

extracellular matrix, activating hepatic stellate cells to

transdifferentiate into myofibroblasts expressing a large amount of

α-SMA (74). Additionally,

treatment with G. mangostana peel also increases hepatic

PPARγ, AMPK and SIRT1 activation, which are linked to its

anti-obesity effect (45).

In an acute acetaminophen-induced liver injury study

by Yan et al (71),

α-mangostin from G. mangostana peel presented with

hepatoprotective benefits by increasing antioxidant markers,

glutathione (GSH) and MDA, and reducing inflammatory cytokines,

including tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) and interleukin (IL)-1β.

α-mangostin also inhibited the expression of autophagy-related

microtubule-associated protein light chain 3 (LC3) and

Bcl-2/adenovirus E1B protein-interacting protein 3. Western blot

analysis further indicated that α-mangostin partially hindered the

activation of apoptotic signaling pathways by increasing Bcl-2

expression, concurrently reducing Bax and cleaved caspase 3

proteins. α-mangostin also increased the expression of p62,

phosphorylated mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), phosphorylated

AKT and reduced LC3 II/LC3 I ratio in autophagy signaling pathways

in mouse liver. This indicates that the effect of α-mangostin on

this model may be related to alteration in the AKT/mTOR pathway

(71).

NAFLD is caused by multiple factors, including

hepatic oxidative stress, lipotoxicity, and mitochondrial

dysfunction. Obesity is among the risk factors for NAFLD alongside

type 2 diabetes mellitus and hyperlipidemia. In NAFLD and NASH

models of high fat diet-induced liver disease, treatment with an

α-mangostin concentration of 50 mg/kg per day was shown to reduce

the liver weight coefficient, AST and ALT levels, reduce hepatic

fibrosis and reduce plasma cholesterol, triglyceride and LDL-C

cholesterol levels. The treatment also improved hepatic structure

and function, and increased glycogen storage, as shown by PAS

staining (46). Additionally,

α-mangostin reduced the levels of caspase-3, a marker of apoptosis,

increased autophagy process and reduced CD68-positive macrophages,

and reduced sequestosome-1 (SQSTM1)/p62, LC3 and α-SMA expression

levels (46).

The accretion of lipids in non-adipose tissues,

including the liver, promotes free fatty acid accumulation in the

hepatocytes and increases apoptosis through production of ROS,

lysosomal pathway and death receptor mediated pathway (75). In high-fat diet models, the

significant increase in SQSTM1/P62 and LC3 expression in the obese

group signifies marked autophagy suppression (46,76), possibly suggesting that a lack of

lysosomal activity may affect autophagic processes and may cause

SQSTM1/P62 and LC3 accumulation (77). Yang et al (76) revealed that hepatic autophagy was

suppressed in dietary and genetic obesity models, due to the

decreased expression of key autophagy molecules such as Atg7.

Hepatic autophagy activation has been reported to promote fatty

acid β-oxidation; thus, autophagy suppression has been suggested to

reduce fatty acid α-oxidation in both in vivo and in

vitro models (78). The

reduced expression of SQSTM1/P62 and LC3 in α-mangostin groups may

occur due to the upregulation of autophagy by inducing

pre-autophagosomal structure expression levels and reducing

SQSTM1/p62 and LC3 within hepatocytes (46,47). This is coupled with the

downregulation of the apoptosis process by improved cellular

antioxidant and antioxidant enzymatic capacity and reduced lipid

peroxidation, due to reduced oxidative stress (43).

The treatment of rats with 25 mg/kg body weight

mangosteen extract a day has been reported to increase hepatic

antioxidant enzyme activities and reduce ROS in rat liver tissue

(43). Treated rats and mice have

demonstrated reduced plasma free fatty acid and hepatic

thiobarbituric acid reactive substances levels, while antioxidant

enzymes and the activities of NADH-cytochrome c reductase, and

succinate-cytochrome c reductase (SCCR) were increased (43,79). In vitro research also

demonstrated showed that α-mangostin also increased membrane

potential, cellular oxygen rate, decreased total ROS and

mitochondrial ROS levels, and reduced calcium and cytochrome c

release from the mitochondria, which reduced caspase-9 and -3

activities linked to the apoptotic processes (43).

There are numerous reports on the hepatoprotective

effects of α-mangostin as an individual compound. Kim et al

(25) reported the reduction of

hepatic lipid droplet, tissue weight, hepatic triglyceride in obese

mice treated with α-mangostin. They further reported that the

changes were associated with reduced expression of sterol

regulatory element-binding transcription factor 1, sterol

regulatory element-binding transcription factor (SREBP)-2,

SREBP-1c, lipoprotein lipase (LPL) and stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1

(SCD1) (25). Li et al

(42) also examined the effects

of α-mangostin on aged mice and noted that the treatment reduced

liver injury, AST and ALT levels, and reduced the expression of

microRNA (miRNA/miR)-155 from epididymal white adipose tissue and

macrophage/monocyte-like (RAW264.7) cells and bone marrow-derived

macrophages. miRNA-155 is a crucial mediator in liver steatosis and

fibrosis and its expression is increased during inflammatory

responses in macrophages (42).

α-mangostin also reduced hepatic steatosis by reducing hepatic

triglyceride and fat accumulation and reducing AST and ALT

(24).

Following the administration of α-mangostin at a

dose of 5 mg/kg per day in a thioacetamide induced hepatic fibrosis

rat model, it was noted that the expression of TGF-β1, α-SMA,

tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases 1 (TIMP-1) was downregulated

(31). In another study by

Rahmaniah et al (80),

α-mangostin was observed to decrease the ratio of pSmad/Smad and

pAKT/AKT in TGF-β-induced liver fibrosis model using human hepatic

stellate (LX-2) cells. They also noted that this treatment reduced

the expression of antigen Ki-67, collagen type I alpha 1 chain

(COL1A1), TIMP-1, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1, α-SMA and

phosphorylated Smad3 (p-Smad3) (80).

In another study, the levels of the hepatic enzymes,

fatty acid transporter and β-hydroxy β-methylglutaryl-CoA (HMG-CoA)

synthase, were significantly suppressed in apolipoprotein E

(Apoe)-deficient mice treated with α-mangostin. However, HMG-CoA

reductase levels increased, and this may be attributed to

compensatory mechanisms triggered by the decrease in HMG-CoA

synthase. Histologically, the treatment also reduced hepatic lipid

accumulation and fibrosis and could be linked to the reduction of

TC due to HMG-CoA synthase inhibition and a reduction of fatty acid

transporter gene expression (81).

In a STZ diabetic mouse model, α-mangostin treatment

(doses of 25, 50 and 100 mg/kg per day) increased plasma insulin

levels, increased superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT) and

GSH and reduced TC, triglycerides, LDL-C, very low-density

lipoprotein cholesterol (VLDL-C), AST, ALT, alkaline phosphatase

(ALP) and lipid peroxidation. The treatment also improved hepatic

damage induced by streptozotocin (66).

Another study reported that α-mangostin (10 and 20

µM) inhibited acetaldehyde-induced hepatic stellate (LX-2)

cell proliferation through the downregulation of Ki-67; and

activation through the reduced expression of α-SMA (82). The treatment also reduced the

hepatic stellate cell (HSC) migration markers: Matrix

metallopeptidase (MMP)-2 and -9 as well as expression and

concentration of TGF-β1. The phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and the

expression levels of the fibrogenic markers, COL1A1, TIMP-1 and

TIMP-3, were also reduced. In addition, α-mangostin upregulated the

expression of the antioxidant defenses manganese superoxide

dismutase and glutathione peroxidase (GPx), and reduced

intracellular ROS levels (82).

Overall, α-mangostin reduced acetaldehyde-induced HSC proliferation

and activation via the TGF-β and ERK 1/2 pathways (82).

A sophisticated transcriptomic study conducted by

Chae et al (83), revealed

several novel pathways in lipid and cholesterol metabolism when

HepG2 and Huh7 cells were treated with α-mangostin (10 and 20

µM) for 24 h. The compound decreased the expression levels

of several cholesterol biosynthetic genes, including SQLE, HMGCR,

LSS and DHCR7, and controlled the specific cholesterol

trafficking-associated genes, ABCA1, SOAT1 and PCSK9. α-mangostin

also reduced SREBP2 expression, indicating that SREBP2 is an

essential transcriptional factor in lipid or cholesterol

metabolism, as observed by the decreased amount of SREBP2-SCAP

complex. When exogenous cholesterol was added, α-mangostin reduced

SREBP2 expression and the synthesis of PCSK9 which could increase

cholesterol uptake in cells and provide a feasible explanation of

the cholesterol-reducing properties of α-mangostin (83). Overall, α-mangostin treatment in

HepG2 cells, controlled cholesterol homeostasis through a reduction

in the expression of SREBP2 and its downstream target genes in

cholesterol synthesis (SQLE and IDI1) and cholesterol trafficking

(ABCA1 and PCSK9) (83).

α-mangostin also downregulated the expression levels of FADS1,

FADS2 and ACAT2 involved in the lipid metabolic pathway.

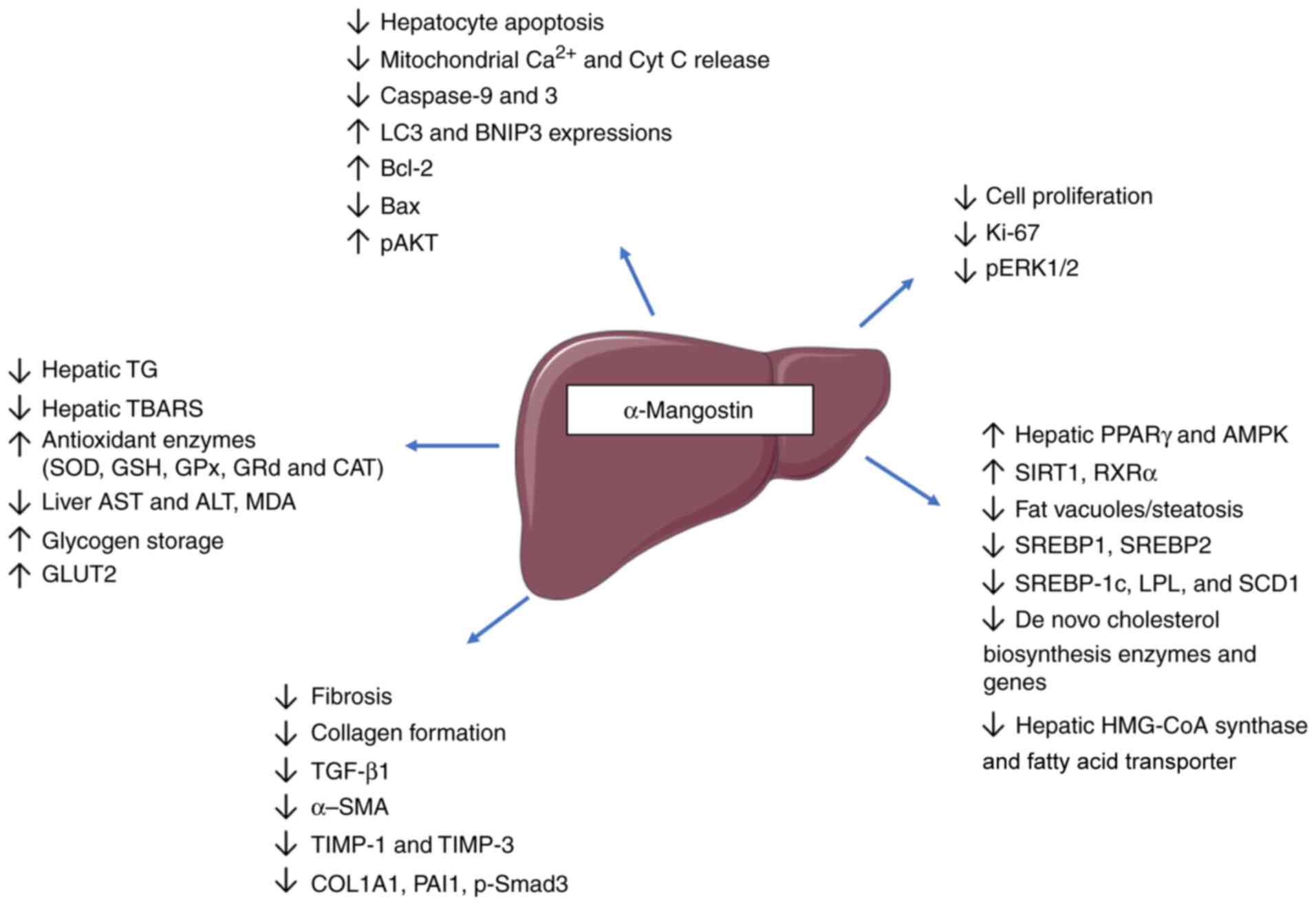

Overall, the molecular effects of α-mangostin in

hepatic tissue are multifaceted and complex, reflecting the key

functions of the liver in metabolism. The improvement in hepatic

structure is associated with decreased collagen deposition and

fibrosis observed by several researchers associated with the

modulation of genes or proteins involved in fibrosis, including

TGF-β1, smad3, TIMP-3, TIMP-1, PAI1, COL1A1, miRNA-155-5p and

α-SMA. α-mangostin also prevents the apoptosis of hepatic tissues,

as demonstrated by the decrease in cleaved caspase-3 and 9-activity

levels in liver cells, regulating hepatic lipid and carbohydrate

homeostasis, reducing fat vacuoles or steatosis, improving liver

function, and preventing hepatic inflammation and oxidative stress,

as well as upregulating hepatic autophagy. The molecular mechanisms

of α-mangostin in hepatoprotective effects are summarized in

Fig. 3 and Table III.

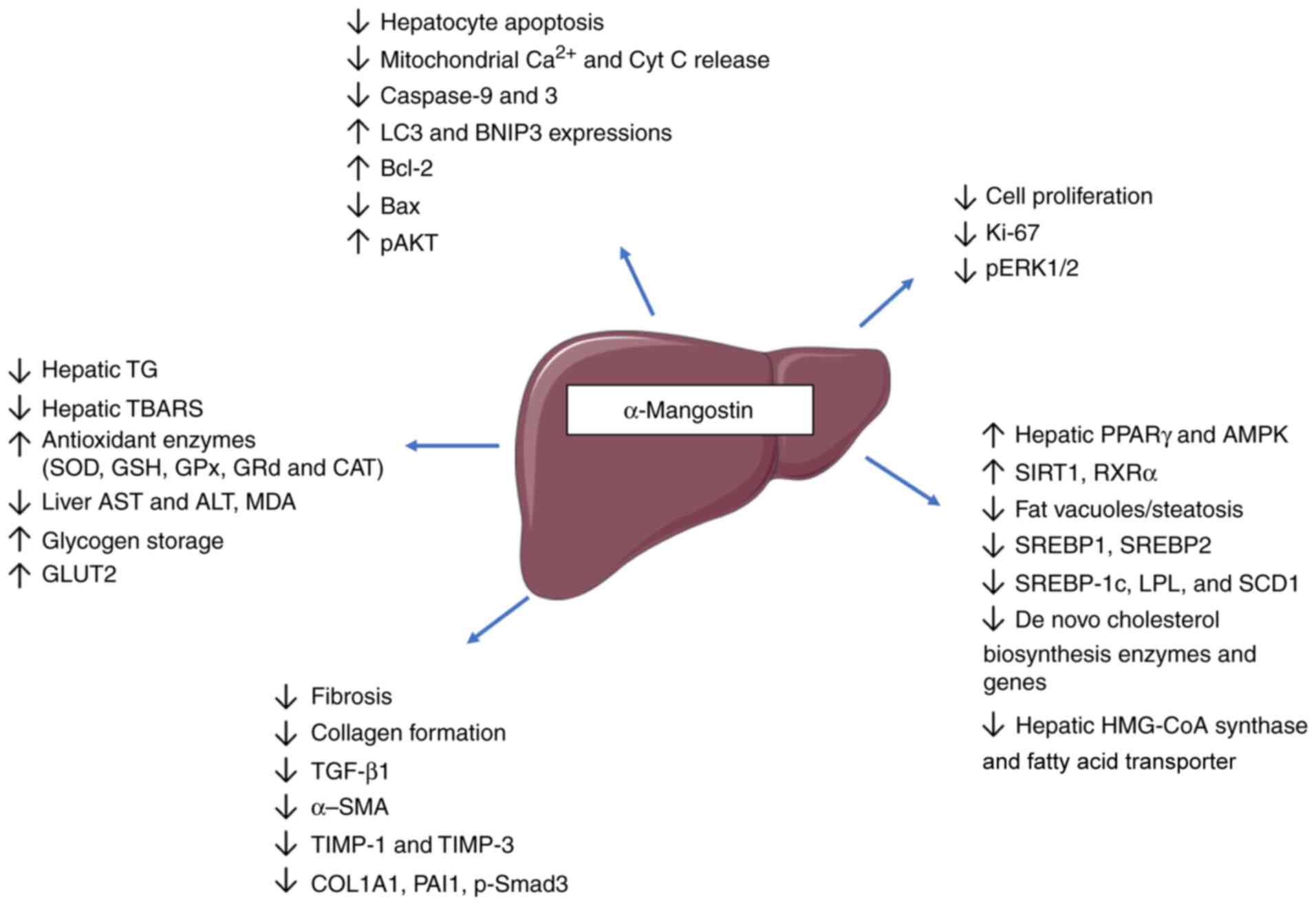

| Figure 3Anti-steatotic and hepatoprotective

effects of α-mangostin. The improvement in hepatic structure and

function by α-mangostin is mediated through decreased collagen

deposition and fibrosis, affecting related genes/proteins (TGF-β1,

Smad3, TIMP-3, TIMP-1, PAI1, COL1A1, miRNA-155-5p and α-SMA).

α-mangostin also prevents the apoptosis of hepatic tissues,

regulates hepatic lipid and carbohydrate homeostasis via AMPK,

PPARγ, SIRT1 and RXRα, reduces steatosis, improves liver function,

prevents inflammation and oxidative stress and upregulates hepatic

autophagy. TIMP, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases; PAI1,

plasminogen activator inhibitor-1; COL1A1, collagen type I alpha 1

chain; α-SMA, α-smooth muscle actin; TG, triglyceride; TBARS,

thiobarbituric acid reactive substances; SOD, superoxide dismutase;

GSH, glutathione; GPx, glutathione peroxidase; GRd, glutathione

reductase; CAT, catalase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT,

alanine aminotransferase; MDA, malondialdehyde; GLUT, glucose

transporter; PPARγ, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ;

SIRT1, sirtuin 1; RXRα, retinoid-X-receptor α; SREBP, sterol

regulatory element-binding transcription factor; LPL, lipoprotein

lipase; SCD1, stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1; HMG-CoA, β-hydroxy

β-methylglutaryl-CoA. |

| Table IIIAnti-steatotic and hepatoprotective

effects of a-mangostin. |

Table III

Anti-steatotic and hepatoprotective

effects of a-mangostin.

| Authors | Source of

α-mangostin | Model

in-vitro/in vivo | Dosage and

duration | Mechanisms of

action of hepatoprotective effects | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Tsai et

al | Mangosteen pericarp

extract | Sprague-Dawley; Rat

primary hepatocytes | 25 mg/day; rat 11

weeks 10-30 µM; rat hepatocytes 24 h | • ↓Hepatic

TG

• ↓Hepatic TBARS

• ↑Antioxidant enzymes (SOD, GSH, GPx, GRd and

CAT)

• ↑NCCR and SCCR activities in liver tissue Cell

study

• ↑OCR

• ↓tROS and mitoROS

• ↓Mitochondrial Ca2+

and cytochrome c release

• ↓Caspase-9 and -3 | (43) |

| Chae et

al | G.

mangostana peel | Male C57BL/6

mice | 200 mg/kg per day

45 days | • ↑Hepatic

PPARγ, AMPK, SIRT1 | (45) |

| John et

al | G.

mangostana rind | Wistar rats | 168 mg/kg per day 8

weeks | • ↓Hepatic

fat vacuoles and inflammatory cells

• ↓Collagen formation | (12) |

| Mohamed et

al | G.

mangostana extract | Balb/c mice | Group III, 50 mg/kg

of α-mangostin per day for 16 weeks Group IV, 50 mg/kg of

α-mangostin per day for the last 2 weeks | • ↓Liver

weight coefficient

• ↓Liver AST and ALT

• ↓Plasma cholesterol, triglycerides and LDL-C,

↑HDL-C

• ↑Hepatic structure and function

• ↓Hepatic fibrosis

• ↑Glycogen storage

• ↑Autophagy process

• ↓Hepatocyte apoptosis (caspase 3)

• ↓CD68-positive macrophages

• ↓p62 expression

• ↓LC3 expression

• ↓α-SMA expression | (46) |

| Muhamad Adyab et

al | G.

mangostana flesh | Sprague Dawley

rats | 200-600 mg/kg (α

mangostin concentration not detailed) 7 weeks | • ↓Hepatic

lipid accumulation | (44) |

| Rusman et

al | G.

mangostana peel infusion | Wistar rats | 0.25-2% 1

month | • ↓Hepatic

structural damage induced by H2O2 | (69) |

| Fu et

al | G.

mangostana fruit rind |

lipopolysaccharide/d-galactosamine

(LPS/D-GalN)-induced acuteliver failure mice model | 12.5, 25 mg/kg 7

days | • ↑Liver

morphology

• ↓Hepatic MDA, ALT and AST | (72) |

| Abood et

al | G.

mangostana peel | Sprague-Dawley

rats | 250 mg/kg per day

and 500 mg/kg per day 8 weeks | • ↓Liver

index

• ↓Hepatocyte proliferation (PCNA staining)

• ↓Hepatic fibrosis

• ↓α-SMA, TGF-β1

• ↓Serum bilirubin

• ↓Total protein, albumin and liver enzymes (ALP, ALT and

AST) | (73) |

| Hassan et

al | G.

mangostana fruit rind | Wistar rats | 500 mg/kg per day

for 30 days after irradiation | • ↑Liver

function test

• ↑Liver morphology | (70) |

| Yan et

al | Purified

α-mangostin | ICR mice exposed to

acetaminophen, acute liver injury model | 100 and 200 mg/kg 7

days | • ↑Liver

morphology

• ↓Expression of LC3, BNIP3

• ↑expression Bcl-2

• ↓Bax and cleaved caspase 3

• ↑p-mTOR, ↑ p-AKT

• ↓LC3 II/LC3 I ratio in autophagy signaling pathways in

mouse liver

• ↓Degradation of p62/SQSTM1 protein | (71) |

| Rodniem et

al | Purified

α-mangostin |

Thioacetamide-induced hepatic fibrosis rat

model | 5 mg/kg (twice a

week) 8 weeks | • ↓TGF-β1,

α-SMA, TIMP-1 | (31) |

| Rahmaniah et

al | Purified

α-mangostin | Human hepatic

stellate cells, LX-2 | (5 or 10 µM)

24 h | • ↓TGF-β

concentration

• ↓Ki-67 and p-Akt expression

• ↓Expression of COL1A1, TIMP1, PAI1, α-SMA

• ↓p-Smad3 as fibrogenic markers | (80) |

| Lestari et

al | Purified

α-mangostin | Acetaldehyde

induced human hepatic stellate cells (HSC), LX-2 | (10 µM) 24

h | •

↓proliferation and migration of HSC

• ↓Ki-67

• ↓pERK1/2

• ↓TGF-β

• ↓COL1A1

• ↓TIMP1 and TIMP3

• ↑Expression MnSOD and GPx

• ↓α-SMA

• ↓ROS | (82) |

| Kim et

al | Purified

α-mangostin | C57BL/6 mice

RAW264.7 macrophages Mesenteric adipose tissue culture | 50 mg/kg per day 12

weeks 25 µM/ml 24 h | • ↓Lipid

droplets

• ↓Liver tissue weight

• ↓Liver triglyceride

• ↓SREBP1, SREBP2

• ↓Expression of hepatic SREBP-1c, LPL and SCD1

• ↑Liver functions (AST and ALT) | (25) |

| Li et

al | Purified

α-mangostin | Mouse derived

RAW264.7 macrophage 3T3-L1 preadipocytes Male C57BL/6J | 25 and 50 mg/kg per

day 8 weeks (old mice) | •

↓MicroRNA-155-5p from macrophages, eWAT and serum

• ↓AST, ALT

• ↑p-AKT

• ↓Liver injury | (42) |

| Choi et

al | Purified

α-mangostin | Male CB57L/6

mice | 50 mg/kg per day 6

weeks | • ↓Hepatic

TG

• ↓Hepatic fat accumulation

• ↓Serum AST and ALT | (24) |

| Chae et

al | Purified

α-mangostin from G. mangostana | HepG2 cell lines

Hur7 cells | 0.8, 1, 10, 20

µM 24 h | • ↓FDFT1,

SQLE, LSS, CYP51A1, MSMO1, HSD17B7 and DHCR7 (de novo

cholesterol biosynthesis)

• ↓PCSK9, SQLE, HMGCR and LSS (enzyme-encoding metabolic

genes)

• ↓DHCR7, FDFT1, FDPS, HMGCR, IDI1, PCSK9, SQLE and SREBP2

(cholesterol biosynthesis)

• ↓SCAP-SREBP2 complexes formation in endoplasmic reticulum

and Golgi

• ↑Cholesterol and LDL-C uptake

• ↓FADS1, FADS2 and ACAT2 expression | (83) |

| Shibata et

al | G.

mangostana extract rich in α-mangostin | Male

Apoe−/− mice | 0, 0.3, 0.4% of

α-mangostin 17 weeks | • ↓Body

weight

• ↓Hepatic HMG-CoA synthase and fatty acid

transporter

• ↓Hepatic steatosis

• ↑Serum lipoprotein lipase | (81) |

| Ibrahim et

al | α-mangostin

(Cratoxylum arborescens) | ICR female and male

mice Human Normal hepatic cells (WRL-68) | 100, 500 and 1,000

mg/kg body weight IC50, 65 mg/ml | • No

toxicity | (19) |

5. Cardioprotective and anti-atherogenic

effects of α-mangostin

Garcinia mangostana pericarp extract has been

previously suggested to counteract the effects of

NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester in a hypertensive rat model

(84). The administration of

G. mangostana extract at a concentration of 200 mg/kg per

day partially attenuated the effects of the drug by reducing

hypertension, arterial wall thickness, and cardiovascular

remodeling. The treatment also attenuated oxidative stress activity

induced by the drug by decreasing plasma MDA, increasing plasma

nitric oxide (NO) metabolites and reducing

p47phoxNADPH oxidase subunit and inducible

nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) protein expression in aortic tissues

(84). The addition of G.

mangostana rind in powder to the diet of obese rats (daily

intake equivalent to α-mangostin concentration of 168 mg/kg per

day) resulted in improved cardiovascular structures by reducing

fibrosis and collagen deposition. Cardiac structure improvement was

accompanied by a reduction in cardiac stiffness, as measured by

Langendorff's isolated heart contraction assessment. The treatment

also improved aortic endothelial tissue activity, while lowering

blood pressure (12).

Pre-treatment with α-mangostin (200 mg/kg per body

weight per day) for 8 days in Wistar rats significantly reduced

cardiac TNF-α and cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 expression induced by

Isoproterenol (ISO). α-mangostin also reduced lysosomal hydrolases

in both serum and cardiac tissues, preserved myocardial membrane

integrity through restoring membrane-bound phosphatases function,

and reduced ISO-induced oxidative stress and cellular damage

(32). In another study,

pre-treatment with α-mangostin (200 mg/kg/day) for 8 days in Wistar

rats decreased the functional abnormalities and mitochondrial

function disturbance induced by ISO (72). Treatment with α-mangostin improved

cardiac endothelial NOS (eNOS) expression and NO concentration. The

administration of α-mangostin also increased cardiac mitochondrial

cytochrome c, c1, b and aa3 levels, and improved NADH

dehydrogenase and cytochrome c oxidase activity. The reduction of

lipid peroxides in the treatment group was associated with enhanced

antioxidant enzyme activity. The findings have suggested that

α-mangostin may present with cardioprotective effects in myocardial

cells by upregulating oxidative mitochondrial enzymes (85).

In an Apoe-deficient mouse model, α-mangostin

(0.3 and 0.4%) reduced TC, triglycerides (0.4%) and VLDL-C

(81). The treatment also reduced

the risk of atherosclerosis by decreasing the deposition of

cholesterol in the aortic arch, aortic hiatus and renal artery

bifurcation area, and improved hepatic lipid droplets. The level of

lipoprotein lipase enzyme was significantly increased in the

0.4%-concentration group; however, no changes were observed in the

serum level of the proatherogenic indicator, soluble lectin-like

oxidized LDL receptor-1. Macrophages analysis revealed that the

expression of Cd163 gene (M2 macrophage marker) was

increased, whereas CD68 levels (pan-macrophage marker) and Nos1 (M1

macrophage marker) were not significantly altered. The M2

macrophage populations were more frequent in atherosclerotic

lesions exposed with 0.4% treatment. Inflammatory cytokine levels

(IFN-γ, TNF-α and IL-1β) exhibited a decreasing trend, while the

IL-13 (M2 polarizing cytokine) was increased (81). The accumulation of M1 is a

hallmark for atherosclerosis progression, however, the M2 type is

predominant in atherosclerosis recession. Plausibly, α-mangostin

has been suggested to induce the microenvironment for M2

polarization observed in the treatment group and subsequently

reduce the development of atherosclerotic lesions (81).

A previous study using human umbilical vein

endothelial cells (HUVECs) grown in a high glucose environment

treated with α-mangostin has revealed the treatment decreased high

glucose-induced ROS formation and high glucose-induced apoptosis.

Further analysis then revealed that α-mangostin reduced apoptosis

through the suppression of JNK and p38-MAPK pathway via the

inhibition of JNK and p38-MAPK phosphorylation (86). Another study using HUVECs grown in

high glucose (60 mM) significantly reduced cellular viability and

increased reactive oxygen species and cellular senescence through

the reduction of senescence-associated β-galactosidase activity

(87). A high glucose environment

also elevated p53, acetyl-p53 and p21 protein levels and IL-6

secretions; however, it reduced SIRT1 and total AMPK protein

levels. Of note, α-mangostin (1.25 µM) reversed the toxic

effects of high glucose in HUVECs by reducing apoptosis, ROS, IL-6

secretion, p53 expression while increasing SIRT1 expression. These

results demonstrated that in high-glucose conditions, α-mangostin

has demonstrated beneficial effects in endothelial cells,

suggesting protective effects on the vasculature, and

anti-senescence effects, most likely due to its antioxidant

activity through the SIRT1 pathway. Thus, α-mangostin may act as a

natural agent to protect against high glucose-induced vascular

damage in diabetic patients (87).

In another study, the use of α-mangostin to treat

CoCl2-induced hypoxic injury in H9C2 cardiomyocytes

demonstrated increased cell viability in the treatment group, with

the concentration of 0.06 mM being the most effective concentration

(88). Additionally, the

treatment also reduced ROS and MDA, while increasing SOD levels.

α-mangostin treatment reduced the number of apoptotic cells treated

with CoCl2. RT-qPCR analysis further revealed that the

treatment also increased expression of Bcl-2, while reducing gene

expression of Bax, caspase-3 and-9, involved in apoptosis. This

finding was in accordance with the reduction of protein levels of

Bax, caspase-3 and caspase-9, and revealed that α-mangostin exerted

cardioprotective effects by reducing apoptotic genes and oxidative

stress (88).

Hyperglycemia affects the vascular system, leading

to vascular complications, which are the leading causes of

mortality among individuals with diabetes. The damage to the

endothelial stems from an aberrant accumulation of ceramide

(59), occurs when NO production

is impaired (79). NO is a

natural molecule produced by endothelial cells that controls the

vascular tone in a paracrine manner (89). Hyperglycemia activates the acid

sphingomyelinase (aSMase)/ceramide pathway. The activation of this

pathway leads to ROS generation, inhibiting NO production in

endothelial cells (90) and

affecting the vascular tone. Ceramide accumulation and its

metabolites exert damaging effects on insulin sensitivity,

pancreatic β-cell function, vascular reactivity and mitochondrial

metabolism (91).

In a previous study, diabetic mice treated with

α-mangostin (10 mg/kg) for 12 weeks presented with limited aSMase

activity and ceramide deposition in the aortas and partially

improved vascular dysfunction (79). The endothelial vascular

dysfunction was also improved through eNOS/NO pathway as

α-mangostin increased the expression of phosphorylated eNOS in

diabetic mouse aortas. In isolated aortas, α-mangostin was also

reported to prevent the activation of aSMase/ceramide pathway

induced by high glucose. Following a testing of the compound in

high glucose environment endothelial cell culture, α-mangostin

reversed the upregulation of aSMase/ceramide pathway. That study

suggested that α-mangostin may improve endothelial dysfunction, by

affecting the aSMase/ceramide pathway (79). α-mangostin could exert this effect

as it has been revealed to be a competitive inhibitor of the aSMase

enzyme (92). The restoration of

the vascular function resulted from increased NO generation and

eNOS phosphorylation. α-mangostin has also been proposed to reduce

endothelial vasoconstrictor, endothelin-1 (ET-1) (63). ET-1 is overexpressed due to

hyperglycemia-induced oxidative stress and the generation of free

radicals, and enhances vascular resistance (93,94).

In a previous study using a rat model of

doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity, treatment with α-mangostin (100

and 200 mg/kg) was suggested to improve electrocardiograph

recordings, heart/body weight ratio and histological structures,

increase systolic blood pressure, decrease MDA levels, improved the

GSH level and normalize creatine kinase-MB (CK-MB) levels and

lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) compared to doxorubicin-treated (DOX)

rats (95). CK-MB detection in

serum is a sensitive indicator in the early stages of cardiac

damage, whereas LDH levels will increase when further cardiac

damage occurs (96,97). As previously demonstrated,

α-mangostin (100 mg/kg) reduced the ratio of Bax/Bcl-2 as compared

to DOX in heart tissues. It also decreased apoptotic protein

caspase-9 and-3 levels, and myocardial IL-1β and TNF-α expression

levels (95). Similarly, Soetikno

et al (98) revealed that

treatment with α-mangostin (100 and 200 mg) decreased CK-MB, LDH,

blood pressure and cardiac proinflammatory cytokine levels (TNFα,

MCP-1, IL-6 and IL-1β), by inhibiting the infiltration of cardiac

tissue with immune cells, and decreasing cardiac hypertrophy and

fibrosis in rats with STZ-induced diabetes.

In a prospective cohort study, patients with

high-risk Framingham Score treated with 2,520 mg of G.

mangostana extract daily for 90 days, exhibited reduced MDA

levels and increased SOD levels, as compared to the placebo group

(99). The excessive formation of

ROS can trigger the production of MDA, as a result of lipid

peroxidation, endogenous antioxidants combined with exogenous

antioxidant compounds could counteract MDA formation. The

anti-atherogenic effects observed in that study could most possibly

be attributed to the antioxidant properties of xanthones from G.

mangostana, resulting in the inhibition of LDL oxidization and

MDA formation (99).

In an animal model fed a high-cholesterol diet, the

administration of 400 and 800 mg/kg ethanolic extract of mangosteen

pericarp, rich in α- and γ-mangostin, significantly counteracted

the effects of the high-cholesterol diet by reducing

H2O2 plasma concentration, increasing CAT

activity and inhibited the formation of foam cells in the aorta

(100). The reduction of plasma

H2O2 could possibly be attributed to the

increased conversion of this compound into oxygen and water.

However, it could also be potentiated by the antioxidant activities

of phytocompounds in the pericarp extract (100). Another study using an animal

model similar to the aforementioned one demonstrated that daily

treatment with a 400 and 800 mg/kg body weight dose of ethanolic

extract of mangosteen pericarp, reduced NF-κB and iNOS levels,

while maintaining eNOS activity in treated rats (101).

Furthermore, Wistar rats fed a high-fat diet and

treated with 200, 400 and 800 mg/kg body weight of ethanolic

extract for 8 weeks exhibited a decreased thickness of aortic

perivascular adipose tissue and reduced thickening of tunica

intima-media compared to control high fat group (102). Smooth muscle vascular cell

adhesion protein 1 expression was significantly decreased in

treated rats, according to the evaluation by double-staining

immunofluorescence. Additionally, HDL-C levels were increased and

LDL-C levels were reduced in treated rats, along with the reduction

of TG and TC, particularly in the 400 and 800 mg/kg groups

(102).

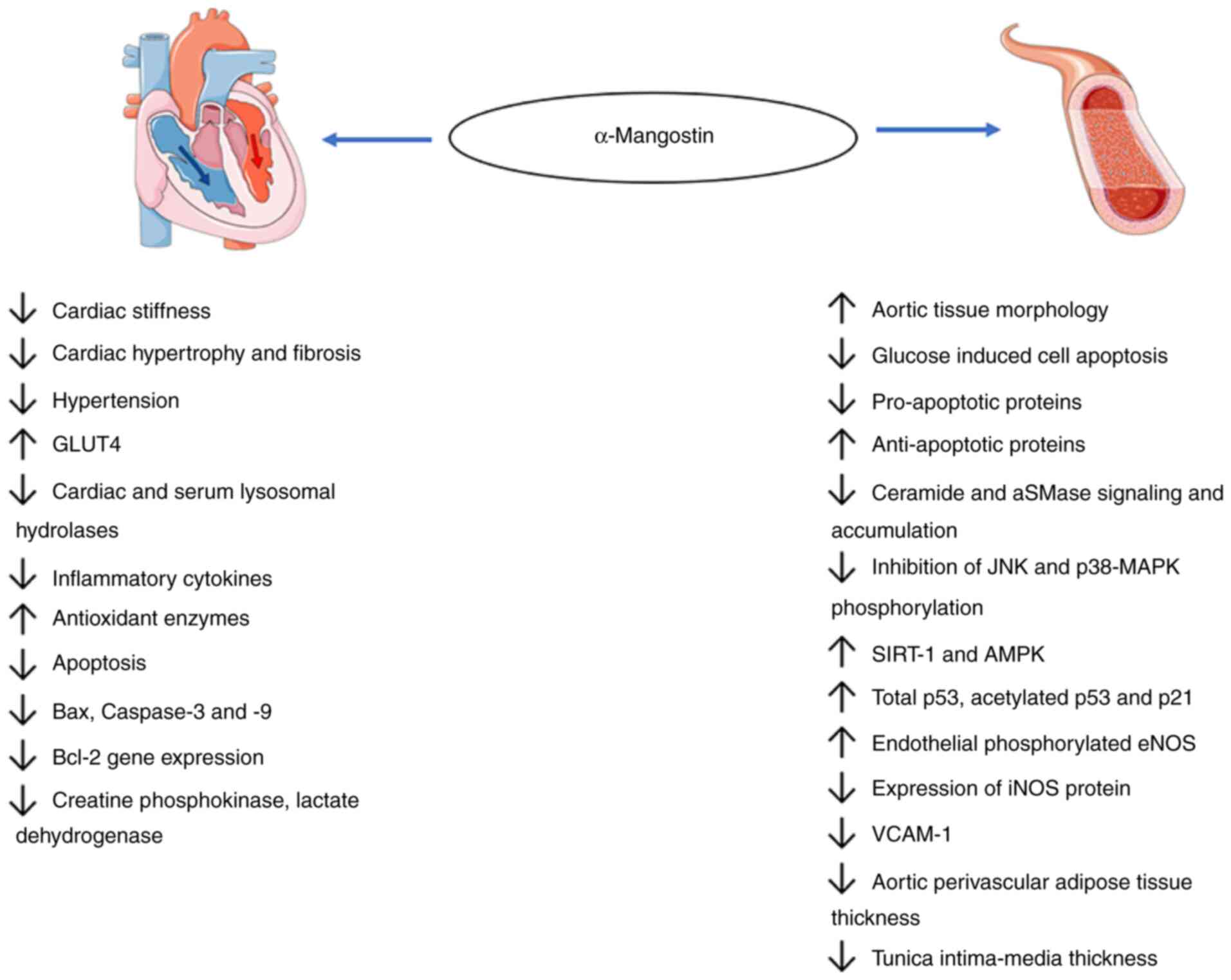

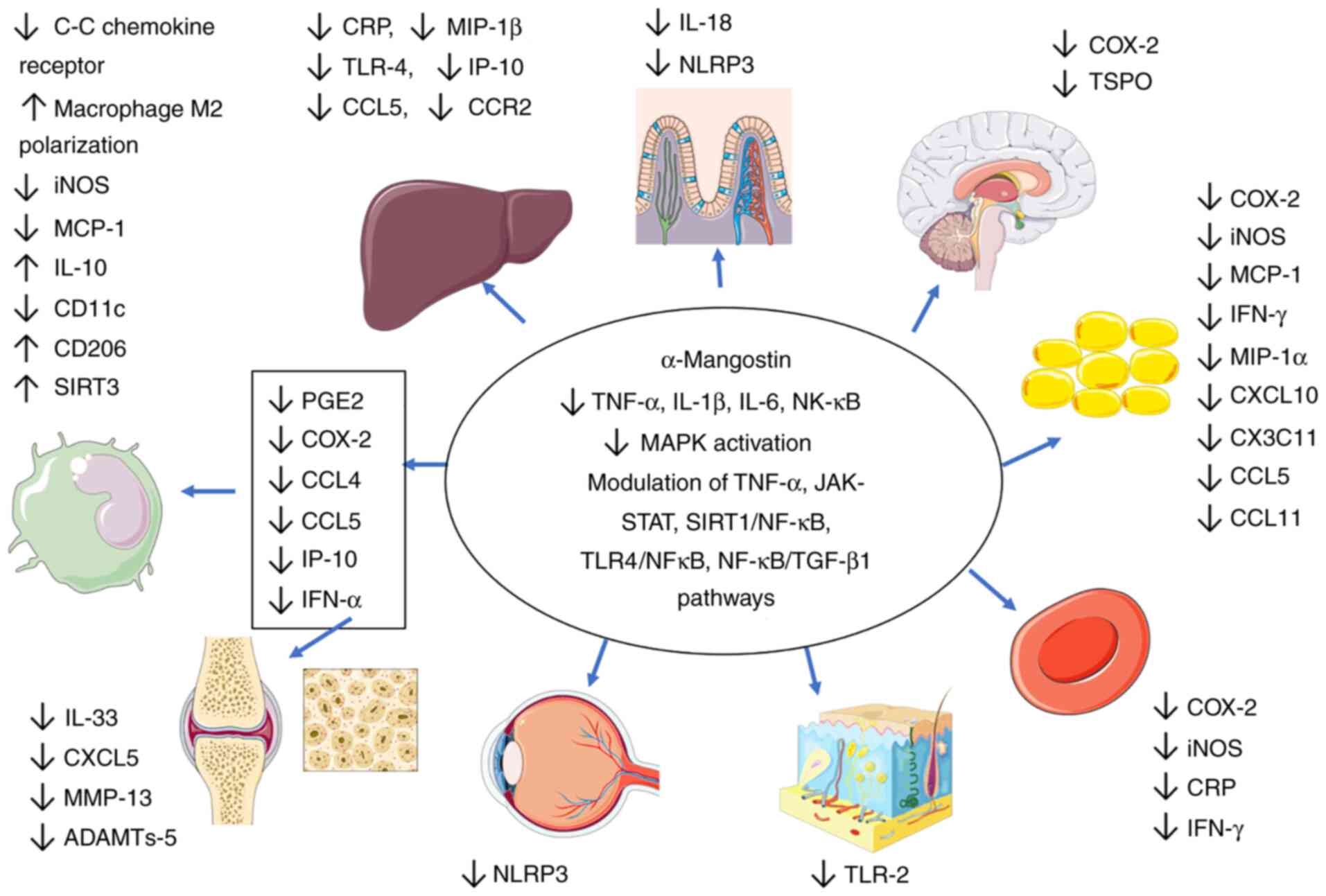

In summary, α-mangostin exhibits cardioprotective

activities through various mechanisms, including: i) Blood

pressure, arterial wall thickness and cardiovascular remodeling

reduction; ii) improvement of cardiovascular structures by reducing

fibrosis and collagen deposition and cardiac stiffness; iii)

reduction of lysosomal hydrolases in both serum and cardiac

tissues; iv) preservation of myocardial membrane integrity by

restoring membrane-bound phosphatases function; v) restoration of

mitochondrial functions; vi) reduction of atherosclerosis risk by

increasing M2 macrophage populations in atherosclerotic lesions;

vii) reduction of cardiac and endothelial cell apoptosis through

pathways including suppression of JNK and p38-MAPK pathway; viii)

reduction of endothelial cell senescence through activation of

SIRT1; ix) reduction of aortic aSMase and ceramide deposition; x)

improvement of cardiac and aortic eNOS expression and NO

concentration and reduction of iNOS and NFκB expressions while

maintaining eNOS expression; xi) reduction of CK-MB and lactate

dehydrogenase; xii) reduction of aortic perivascular adipose tissue

and tunica intima-media thickening; and xiii) reduction of

inflammation and oxidative stress. The molecular mechanisms of the

cardioprotective and anti-atherogenic effects of α-mangostin are

summarized in Fig. 4 and Table IV.

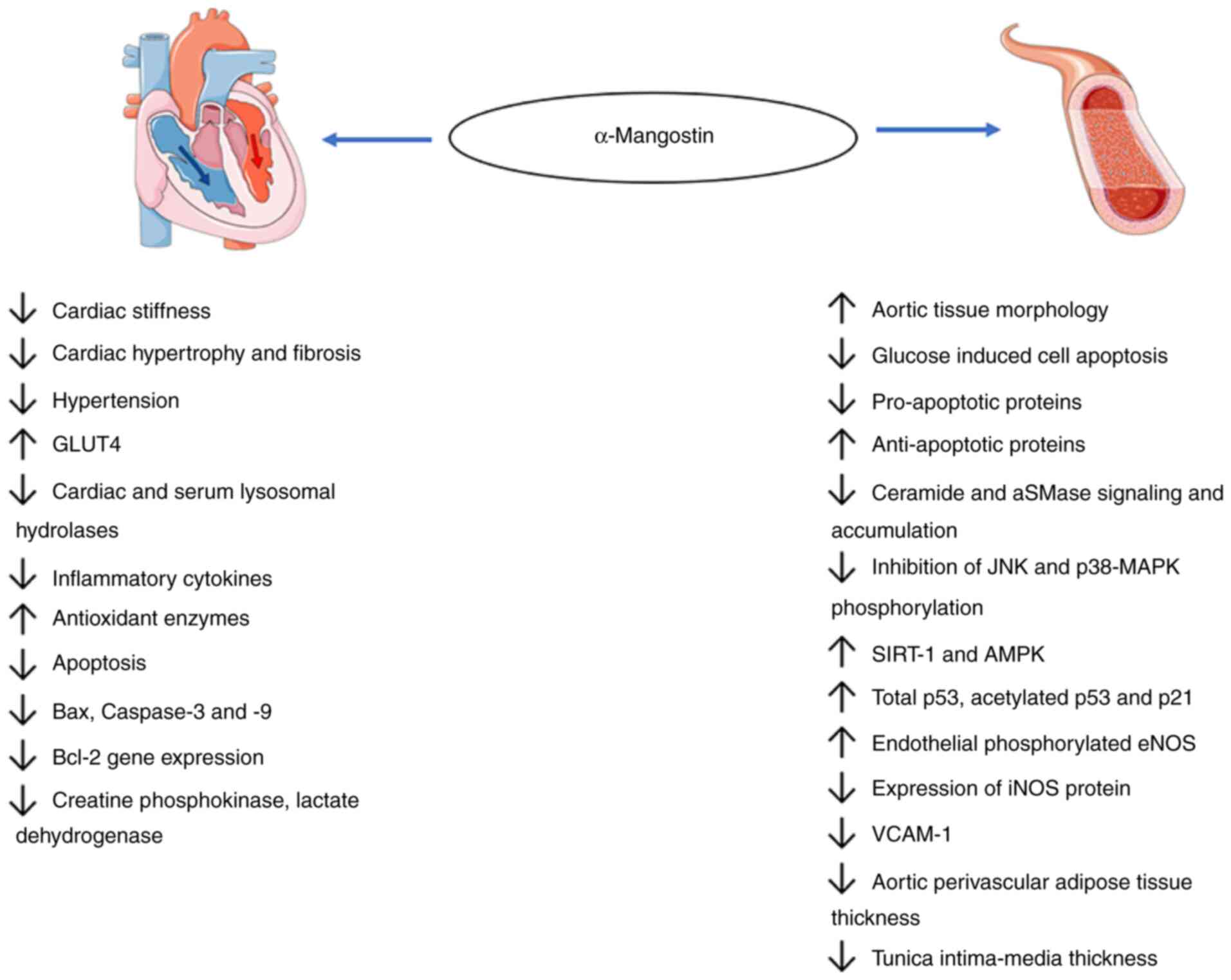

| Figure 4Cardioprotective and anti-atherogenic

effects of α-mangostin. α-mangostin protects the heart and blood

vessels against several stressors, including reactive oxygen

species, drug-induced stressors, lipids, aSMase activity,

hyperglycemia and various potentially harmful signaling pathways.

It lowers the levels of inflammatory cytokines and proapoptotic

proteins, such as Bax and caspase-3 and-9, leading to tissue death,

lactate accumulation and aSMase/ceramide signaling. α-mangostin

increases the levels of anti-apoptotic proteins (p53) and

antioxidant enzymes. It restores the heart and blood vessel

morphology by reducing creatine kinase-MB and lactate

dehydrogenase, reducing aortic perivascular adipose tissue

deposition and reducing VCAM-1 expression, tunica intima-media

thickening. aSMase, acid sphingomyelinase; VCAM-1, vascular cell

adhesion molecule 1; GLUT, glucose transporter; SIRT1, sirtuin

1. |

| Table IVCardioprotective and anti-atherogenic

effects of a-mangostin. |

Table IV

Cardioprotective and anti-atherogenic

effects of a-mangostin.

| Authors | Source of

α-mangostin | Model

in-vitro/in-vivo | Dosage and

duration | Mechanism of action

on cardioprotective effects | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Sampath and

Vijayaragavan | Purified

α-mangostin | Isoproterenol

induced-myocardial necrosis Wistar rats | 200 mg/kg/body

weight 8 days | • ↓TNF-α and

COX-2

• ↓Activities of membrane-bound phosphatases

• ↓Cardiac and serum lysosomal hydrolases | (32) |

| Sampath and

Kannan | Purified

α-mangostin | Isoproterenol

induced-myocardial necrosis; Wistar rats | 200 mg/kg/body

weight (pre-treatment) 8 days | • ↑Cytochrome

c, c1, aa3 and b levels

• ↑NADH dehydrogenase and cytochrome c oxidase

activities

• ↑Antioxidant enzymes (GSH, GPx, GST, SOD, CAT)

• ↓Lipid peroxides

• ↑Cardiac eNOS | (85) |

| Jittiporn et

al | α-mangostin

extracted from G. mangostana peel | Human umbilical

vein endothelial cells | 10-100 nM 72 h | • ↓ROS, ↓

apoptosis

• ↓Inhibition of JNK and p38-MAPK phosphorylation | (86) |

| Fang et

al | Purified

α-mangostin | CoCl2-induced

apoptotic damage H9C2 cardiomyoblasts | 0.012, 0.06, 0.3,

0.6 or 1.2 mM 24 h | • ↓ROS,

MDA

• ↑SOD

• ↓Apoptosis

• ↓Bax, caspase-9 and caspase-3 gene expression and

protein

• ↓Bcl-2 gene expression | (88) |

| Tousian et

al | Purified

α-mangostin | Human umbilical

vein endothelial cells | 1.25 µM

(non-toxic xconcentration) 6 days | • ↑Total p53,

acetylated p53 and p21

• ↓SA-β-GAL

• ↑SIRT-1 and AMPK | (87) |

| Jiang et

al | Purified

α-mangostin | Primary aortic

endothelial cells C57BL/KsJ; diabetic (db/db) mice | 10 mg/kg/day, i.p.;

mice 12 weeks 15 µM α-mangostin; cell culture 24 and 48

h | • ↓Serum aSMase and

ceramide

• ↓Aortic aSMase and ceramide

• ↑Endothelial cell NO production

• ↑Endothelial phosphorylated eNOS | (79) |

| Eisvand et

al | Purified

α-mangostin | Doxorubicin-induced

cardiotoxicity rat model Heart cells MC7 cells | 50, 100, 200 mg/kg

per day 19 days | • ↓MDA, caspase-3

and -9

• ↓Inflammatory markers

• ↑Heart weight

• ↓Creatine phosphokinase, lactate dehydrogenase

• ↓IL-1β and TNF-α | (95) |

| Soetikno et

al | Purified

α-mangostin | Wistar rat | 100, 200 mg/kg per

day 8 weeks | • ↓CK-MB,

LDH

• ↓Prevent weight loss in diabetic rats

• ↓Blood pressure

• ↓AST and ALT

• ↓Total cholesterol and triglyceride

• ↓Cardiac pro-inflammatory levels (TNFα, MCP-1, IL-6,

IL-1β)

• ↓Cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis | (98) |

| Shibata et

al | G.

mangostana extract rich in α-mangostin | Male

Apoe−/− mice | 0%, 0.3%, 0.4% of

α-mangostin; 17 weeks | • ↑Aortic tissue

morphology

• ↓Total cholesterol (VLDL)

• ↓Triglyceride

• ↑Serum lipoprotein lipase

• ↑CD163

• ↑IL-13

• ↑M2 polarization

• ↓IFN-γ, TNF-α and IL-1β | (81) |

| John et

al | G.

mangostana rind rich in α-mangostin | Wistar rats (high

carbohydrate, high fat) | 168 mg/kg per day 8

weeks | • ↓Systolic blood

pressure

• ↓Cardiac stiffness

• ↓Cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis

• ↑Endothelial tissue activity | (12) |

| Boonprom et

al | G.

mangostana pericarp extract | Sprague-Dawley rats

(L-Name induced hypertension) | 200 mg/kg per day

(extract) concentration (extract) concentration of α-mangostin; not

detailed; 5 weeks | • ↓Hypertension and

cardiovascular remodeling

• ↓Oxidative stress (MDA) and inflammation (TNF-α)

• ↓Expression of p47phoxNADPH oxidase

subunit

• ↓Expression of iNOS protein in aortic tissues

• ↓Arterial wall thickness

• ↑Plasma NO metabolites | (84) |

| Ismail et

al | G. mangstana

Pericarp extract | Patients with

high-risk Framingham C score | 2,520 mg/day

(extract) oncentration of α-mangostin; not detailed; 90 days | • ↑Plasma

SOD

• ↓Plasma MDA

• ↓Atherosclerosis risk | (99) |

| Adiputro et

al | G.

mangostana Ethanolic pericarp extract | Wistar rats

(High-chole-sterol diet) | 200, 400, 800 mg/kg

per day (containing 0.064% α-mangostin and 6.144% of γ-mangostin)

(Treatment duration not stated) | • ↓Plasma

H2O2

• ↑Plasma CAT

• ↓Foam cells | (100) |

| Wihastuti et

al | G.

mangostana Ethanolic pericarp extract | Wistar rats

(High-chole-sterol diet) | 200, 400, 800 mg/kg

per day 3 months | • ↓NF-κB

• ↓iNOS

• Maintain eNOS | (101) |

| Wihastuti et

al | G.

mangostana Ethanolic pericarp extract | Wistar rats

(High-chole-sterol diet) | 200, 400, 800 mg/kg

per day 2 months | • ↓Aortic

perivascular adipose tissue thickness

• ↓Tunica intima-media thickness

• ↓VCAM-1 expression | (102) |

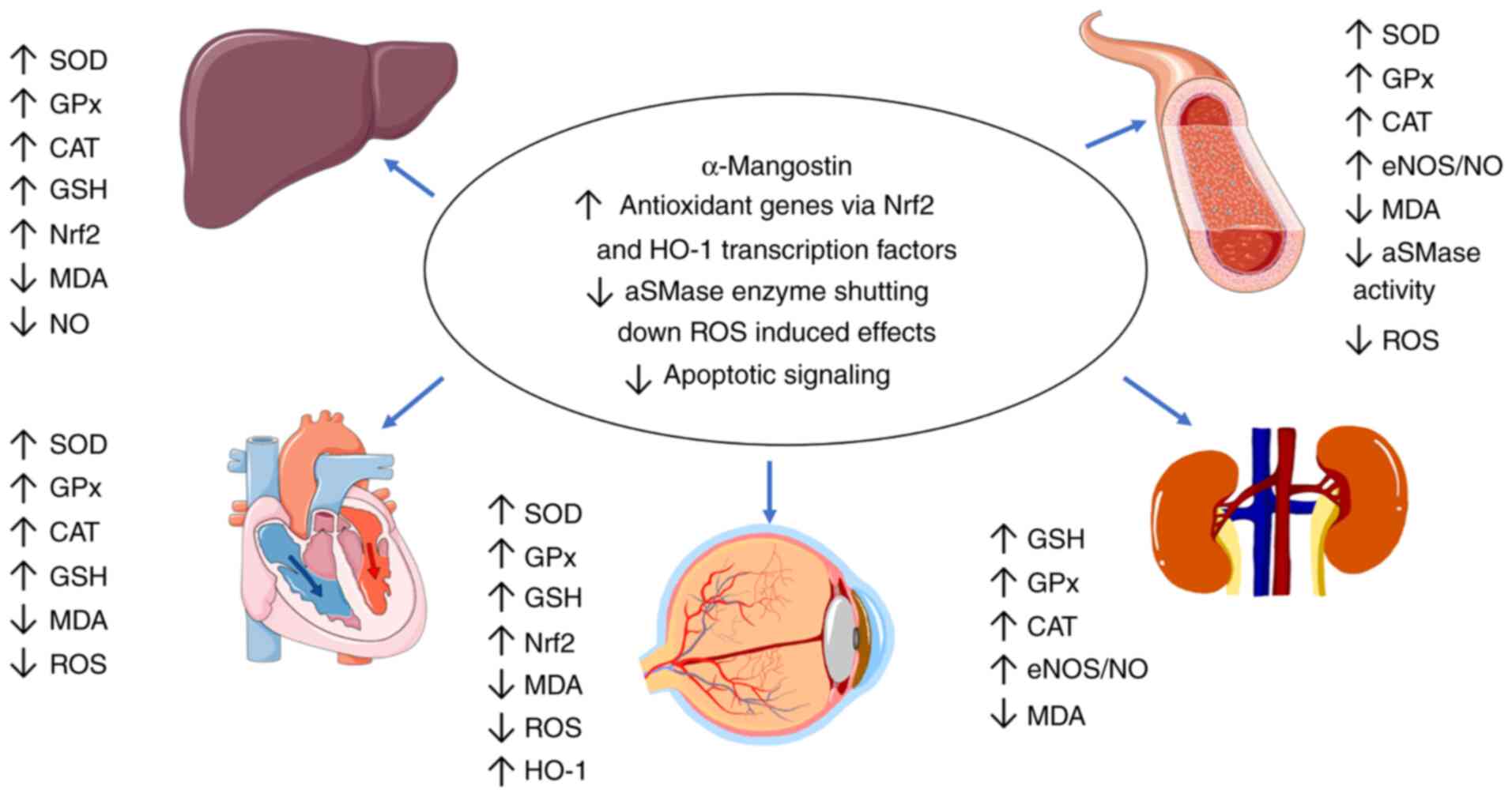

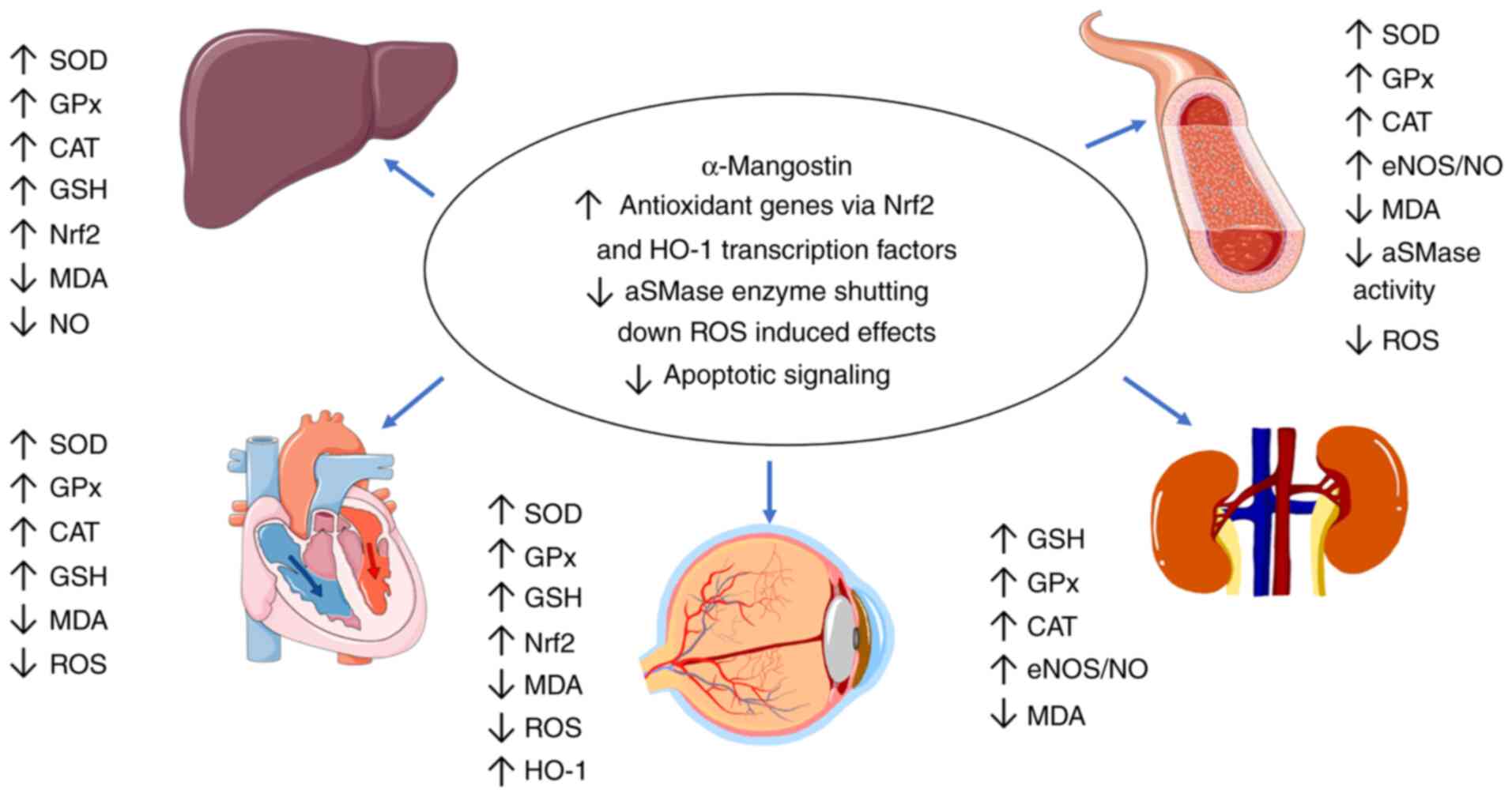

6. Antioxidant effects of α-mangostin

Antioxidants are of physiological importance as

they reduce ROS generation, and are linked to tissue damage, aging

and chronic inflammation (103).

The human body has an antioxidant system involving SOD, GPx and

CAT. These enzymes function together with SOD, converting the

superoxide anion (O2-) to H2O2,

which GPx and CAT convert in turn to water. Another antioxidant

protein is GSH, that reduces ROS accumulation (104). According to a previous study,

α-mangostin was reported to exert protective effects against

oxidative stress by modulating the production of SOD, GPx, GSH and

CAT, via the nuclear factor-erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2)

transcription factor which targets genes involved in antioxidant,

detoxification, metabolism and inflammatory pathways (104).

Fang et al (105) used a mouse light damage model to

induce retinal death via the production of

H2O2. H2O2 produces

oxidative stress, acting as ROS and activates caspase 3, leading to

apoptotic reactions. Treatment with α-mangostin (30 mg/kg)

increased Nrf2 translocation to the nucleus following light

exposure to, inducing the expression of antioxidant genes, reducing

cleaved caspase-3 expression and retinal damage. The interaction of

α-mangostin with Nrf2 is a common mechanism, inducing antioxidant

expression, leading to resistance to oxidant stress. In the same

mouse experiment, treatment with α-mangostin restored the levels of

SOD, GPx and GSH. In the same study, retinal pigment epithelia 19

(ARPE-19) cells exposed to H2O2 were used to

induce cytotoxicity. Pre-treatment with α-mangostin led to a

reduced apoptosis in a dose-dependent manner (4-12 µM), with

an apoptotic rate of 5.85% observed at 12 µM. α-mangostin

reduced ROS production, as observed by DCF fluorescence in flow

cytometry. A similar effect was observed in cultured cells in terms

of restoring levels of SOD, GPx, GSH, and increasing heme oxygenase

1 (HO-1) expression, revealing the robustness of this molecule

(105).

In a previous study by Fu et al (72) in a mouse model of

lipopolysaccharide (LPS)/d-galactosamine (D-GalN)-induced acute

liver failure, α-mangostin also interacted with Nrf2. In that

study, treatment with α-mangostin resulted in an increased

expression of Nrf2, heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1) hepatic GSH, SOD and

CAT with a reduction in hepatic MDA levels (72). This suggests that α-mangostin

either positively interacts with Nrf2 or negatively with Kelch-like

ECH-associated protein 1 (KEAP1). KEAP1 is a negative regulator of

Nrf2, as it ubiquitinates Nrf2, targeting it for degradation

(106). Further research has

revealed that α-mangostin stimulation induces the dissociation of

KEAP1 from Nrf2 in the cytosol and in vivo, supporting the

notion that α-mangostin could dissociate Nrf2 from KEAP1,

permitting Nrf2 protein accumulation and nuclear translocation

(105).

α-mangostin also has anti-oxidant activity by

inhibiting the aSMase enzyme (79). A high-fat/carbohydrate diet

decreases SOD and GPx levels, favors the accumulation of

glucose-induced ROS, and results in increased levels of the

pro-inflammatory markers, TNF-α and IL-6 (44,79). Increased ROS generation aggravates

the system by activating the aSMase/ceramide pathway, leading to

ceramide-induced cell death. By using primary endothelial cells and

a db/db diabetic mice, Jiang et al (79) revealed that α-mangostin reversed

the high glucose-induced ROS production and aSMase/ceramide pathway

activation by inhibiting the aSMase enzyme, as α-mangostin is a

competitive inhibitor of the aSMase enzyme according to another

study (92). This results in an

upregulation of eNOS/NO pathway in aortas from diabetic mice,

reducing ROS levels and restoring their structure and function

(79). Muhamad Adyab et al

(44), using an obese rat model,

demonstrated that rats fed a high-fat/carbohydrate diet

supplemented with a 200-600 mg/kg dose of mangosteen flesh extract

improved SOD and GPx levels (44).

α-mangostin can counteract the effects of

lactate-induced ROS production via MDA generation, and liver damage

due to ionizing radiation and thioacetamide. In a previous study by

Chang et al (107), rats

subjected to high rates of exhaustive exercise accumulated high

levels of lactate in both liver and muscle tissues, which was

rapidly cleared in rats given α-mangostin. Levels of MDA also

diminished in both tissues (5-fold in liver and 10-fold in muscle)

and levels of CAT and GPx increased in both tissues. Thioacetamide-

and radiation-induced liver damage, as measured by ALT, AST and ALP

liver biomarkers, has been also reported to be reversed in

α-mangostin-treated mice (70,73). Hassan et al (70) previously exposed rats to ionizing

radiation, in order to mimic the situations in which the liver is

damaged due to radiotherapy treatment or accidental exposure.

Radiation caused alterations in liver protein homeostasis and

increased plasma liver markers like ALT, AST and ALP, indicating

liver damage. SOD and CAT levels were significantly reduced after

radiation; however, their levels were restored by treatment with

α-mangostin at the 500 mg/kg equivalent dose per day. MDA and NO

levels in the radiated liver doubled compared to the control;

however, this was reduced to normal levels by α-mangostin

treatment.

Abood et al (73) examined the effects of in

thioacetamide-induced liver cirrhosis in rats. Thioacetamide

increased liver markers, AST, ALP and ALT, increased MDA levels,

and reduced SOD and CAT enzymes, while α-mangostin (250 and 500

mg/kg), significantly reduced the effects of thioacetamide

treatment and conserved the liver, heart and kidney from

thioacetamide damage. In a previously reported experiment by

Lazarus et al (108), SOD

levels increased significantly in the heart with an α-mangostin

dose of 100 mg/kg. However, a significant improvement was observed

with 200 mg/kg treatment in the kidneys. GSH also increased in both

tissues, and α-mangostin reversed MDA levels in the liver, kidneys,

and heart tissues. Further study is still required, in order to

finalize the ideal concentration at which beneficial effects are

seen.

Harliansyah et al (109) also reported on the potential

tissue-specific potency of α-mangostin. By using HepG2 and WRL-68

cells, it was observed that when they were exposed to ROS

stimulating chemicals, α-mangostin reduced ROS levels in both cell

lines at comparable levels in a concentration-dependent manner

(5-1,000 µg/ml). However, when assessing MDA levels,

α-mangostin led to a more significant MDA reduction in the HepG2

cancer line, possibly due to the increased oxidative stress in

comparison with the WRL-68 cell line. Notably, when compared to

WRL-68, a normal human hepatic cell line, HepG2 cell line presented

with a more notable reduction of MDA (109). It is possible that HepG2

presented with more reduced MDA because of the effects of both ROS

that stabilizes Nrf2, and oncogenic signaling via KRAS and BRAF

that has been revealed to induce Nrf2 stabilization (110), leading to enhanced production of

antioxidant proteins. They also analyzed protein carbonyl levels,

evaluating the amount of ROS oxidized protein, and observed that

α-mangostin-treated cells demonstrated decreased ROS levels. The

effect was more intense in the WRL-68 cell line, indicating that

this cell line was more responsive, highlighting the potential

anticancer properties of α-mangostin.

Mitochondria are essential organelles involved in

energetic homeostasis and the production of reactive oxygen

species. In a previous study, treatment of proximal tubule Lilly

laboratory culture porcine kidney (LLC-PK1) cells with

Cis-dichlorodiammineplatinum II (CDDP)-induced damage with

α-mangostin (4 µM) demonstrated that the compound preserved

mitochondrial function and mass (111). α-mangostin inhibited the

CDDP-induced decrease in cell respiratory states, in the maximum

capacity of the electron transfer system and the respiration

associated with oxidative phosphorylation protein, preventing

changes in mitochondrial bioenergetics alterations. It also

prevented mitochondrial mass reduction and fragmentation through

the preservation of the mitofusin 2 fusion marker, reducing

induction of autophagy by CDDP (111), and revealing that α-mangostin

can modulate the ROS production at the organelle level.

In another study, in a model of sodium

iodate-induced ROS-dependent toxicity using ARPE-19 cells,

α-mangostin (3.75, 7.5 and 15 µM) prevented cell death,

although not at the 20 µM dose. α-mangostin also prevented

mitochondrial damage as revealed by JC-1 staining, reduced

intracellular ROS levels and the extracellular

H2O2 concentration, increased CAT and GSH

levels, and decreased SOD levels (112). This treatment also prevented

cell apoptosis through the regulation of apoptosis-related

proteins. α-mangostin treatment protected ARPE cells against sodium

iodate-induced oxidative damage by reducing SIRT-3 expression,

mediated by the PI3K/AKT/PGC-1α signaling pathway. Treatment with

α-mangostin in this mouse model revealed that it could prevent

retinal degradation and apoptosis induced by sodium iodate

(112). The proposed mechanism

was that α-mangostin modulated the SIRT-3 pathway (113). SIRT-3, a member of the sirtuin

family, is a mitochondrial enzyme that modulates deacetylation and

acetylation of mitochondrial enzymes and is known to prevent ROS

and the development of cancerous cells or apoptosis (114). As previously explained,

α-mangostin treatment reduced caspase-3 protease levels, reduced

cell apoptosis, and increased p-PI3K-AKT levels, demonstrating the

protective effects of this compound in the presence of STZ

(52,58) and high glucose (59).

In summary, the antioxidant effects of α-mangostin

are exerted primarily through the stabilization of cytoplasmic

Nrf2, the increase in heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1) expression, the

modulation of the aSMase/ceramide pathway, kinase signaling