Introduction

Stroke, a prevalent cerebrovascular disease, is

characterized by high incidence, recurrence, morbidity and

mortality rates, ranking as the second leading cause of disability

and death globally (1). It

primarily encompasses two major categories: Ischemic stroke and

hemorrhagic stroke, with ischemic stroke being more prevalent,

accounting for ~60-80% of all stroke cases (2). Ischemic stroke, also known as

cerebral infarction, is a clinical syndrome that arises from

cerebral ischemia and hypoxia due to stenosis or occlusion of

cerebral vessels, leading to tissue damage or necrosis and

subsequent rapid onset of corresponding neurological deficits. In

the pursuit of therapeutic strategies, it has gradually become

apparent that non-neuronal cells within the central nervous system

(CNS), particularly astrocytes, play a pivotal role in the

pathophysiological processes of ischemic stroke.

As one of the most abundant and versatile cell types

in the CNS, astrocytes not only provide essential nutritional

support, structural scaffolding, and physical protection to

neurons, but also contribute to the formation of the blood-brain

barrier (BBB), regulate potassium ion concentration in the neuronal

extracellular environment, and maintain the stability of the

neuronal milieu. Furthermore, astrocytes play critical roles in

neurotransmitter metabolism, immune responses, pathological

processes and tissue repair, underscoring their indispensable

function in safeguarding the health and functionality of the

nervous system (3). Metabolic

reprogramming refers to the mechanism by which cells alter their

metabolic patterns to facilitate growth, proliferation and

adaptation to environmental changes in response to energy and

biosynthetic demands. As a crucial strategy for cells to cope with

external environmental alterations, metabolic reprogramming

encompasses, but is not limited to, the regulation of multiple

metabolic pathways such as glycolysis, oxidative phosphorylation,

fatty acid metabolism and amino acid metabolism (4). During ischemic stroke, astrocytes

swiftly respond by initiating a series of intricate metabolic

reprogramming processes to adapt to the extreme ischemic and

hypoxic conditions. However, the specific roles and underlying

mechanisms of astrocytes in ischemic stroke remain to be further

systematically investigated.

Therefore, the current understanding of the roles

and mechanisms of astrocyte metabolic reprogramming in ischemic

stroke have been summarized, delving into their molecular

mechanisms, functional alterations and interactions with other cell

types. By consolidating existing literature, it is aimed to uncover

the central role of astrocyte metabolic reprogramming in the

pathophysiological processes of ischemic stroke, thereby providing

a theoretical basis for the development of novel therapeutic

strategies.

The physiological function of astrocyte

The CNS is composed of a large number of

non-neuronal cells called glia, with astrocytes being the primary

type of glial cells that are ubiquitous throughout the entire CNS

and interact with a variety of cells.

Formation and maintenance of the BBB

The BBB, situated between the blood and brain

tissues, serves as a highly selective permeable interface that

safeguards the brain from harmful substances. It is primarily

composed of brain microvascular endothelial cells, astrocytes,

pericytes and the basal lamina, playing a crucial role in

maintaining normal CNS function and internal environmental

homeostasis (5). Structurally,

the BBB can be divided into three layers: The inner layer,

consisting of brain microvascular endothelial cells held together

by tight and adherens junctions, serves as the core component that

restricts the passage of blood-borne substances into the brain. The

middle layer is composed of the basal lamina formed by the

extracellular matrix and pericytes embedded within it. The outer

layer comprises astrocyte foot processes adhering to the

microvascular basal lamina (6).

Astrocytes, with their unique morphology and

functions, play a pivotal role in the formation and maintenance of

BBB integrity, being essential cells that contribute to the

physiological homeostasis of the CNS (7). Once the BBB is formed, mature

astrocytes regulate and maintain the barrier. These cells extend

numerous processes from their cell bodies, which tightly envelop

cerebral capillaries, providing support and separation for neuronal

cells. This intimate contact not only reinforces the structural

stability of the cerebral capillary walls but also participates in

the formation of the basal lamina through the secretion of matrix

proteins by the astrocytes, further enhancing the barrier function

of the BBB (8). Additionally,

astrocytes are crucial for water and potassium homeostasis in the

CNS, as they control the exchange of water and certain solutes

through abundant expression of aquaporin-4 (9).

Ion transport and neuromodulation

Astrocytes are the primary cell type responsible for

regulating brain homeostasis, encompassing the maintenance of ionic

homeostasis and neuronal regulation. Potassium and sodium ions are

crucial for neuronal electrical activity, and the stability of

their concentration is essential for maintaining the normal

function of neurons. Potassium ions predominantly reside within

cells, whereas a large inward electrochemical gradient of sodium

ions serves to generate action potentials. Upon neuronal

excitation, a significant concentration of potassium ions is

released into the extracellular space, leading to a local increase

in potassium ion concentration. Astrocytes, through the expression

of inward rectifier potassium channels such as Kir4.1, can rapidly

uptake these excess potassium ions and distribute them to adjacent

astrocytes via gap junctions, thereby maintaining a stable

potassium ion concentration around neurons. This spatial buffering

of potassium ions helps prevent neuronal hyper-excitation and

damage (10,11). Sodium ions play a pivotal role in

regulating the intracellular pH of astrocytes. While the activation

of the sodium-potassium ATPase in response to elevated

extracellular potassium levels may decrease intracellular sodium

ions, the co-transport of neurotransmitters such as glutamate with

sodium ions leads to an increase in sodium ions within astrocytes,

thereby modulating downstream metabolic pathways (12).

Astrocytes also play a vital role in neuromodulation

within the CNS. They are capable of sensing and responding to

neurotransmitters and other signaling molecules released by

neurons, and influence neuronal excitability and synaptic

plasticity through the release of their own neuroactive substances

(13). Furthermore, astrocytes

form intricate network structures through gap junctions among

themselves and with neurons, enabling them to synchronize their

activities and transmit information. This signal transduction and

neuromodulation function contribute to maintaining the homeostasis

and adaptability of the nervous system (14).

Nutrition and support

Neurotrophic factors are proteins that play a

crucial role in the development, survival and apoptosis of neurons.

Under normal physiological conditions, astrocytes can release

various neurotrophic factors, such as brain-derived neurotrophic

factor and nerve growth factor. These neurotrophic factors are

essential for the growth, development, survival and functional

maintenance of neurons. They facilitate the growth of neuronal

axons and dendrites, enhance synaptic connections between neurons,

and thereby increase the complexity and functionality of neural

networks.

Relationship between astrocyte and ischemic

stroke

In response to the damage of CNS, neurodegenerative

diseases, or other infectious diseases, the genes, morphology, and

functions of astrocytes undergo rapid changes, and these reactions

are collectively referred to as astrocyte reactivity (15). In recent years, with the

intensifying exploration into the intricate functional diversity of

astrocytes, researchers have uncovered their ability to

differentiate into distinct functional phenotypes under various

pathological conditions, notably the A1 and A2 subtypes. After the

onset of stroke, astrocytes are activated and release

pro-inflammatory or anti-inflammatory factors, leading to a complex

neuroinflammatory cascade reaction, which has a dual effect on

neuroinflammation after ischemic stroke (16). These subtypes exhibit profoundly

different mechanisms of action during the pathological process of

ischemic stroke, significantly impacting disease progression,

outcome and neural repair.

Through genetic profiling of reactive astrocytes in

mouse models of ischemic stroke and neuroinflammation, Zamanian

et al (17) demonstrated

that reactive astrocytes can be induced by different types of

insults to adopt either an A1 or A2 phenotype. Specifically,

ischemic injury triggers the emergence of so-called trophic A2

astrocytes, whereas inflammatory insults induce the more neurotoxic

A1 astrocytes (17). Liddelow

et al (18) further

elucidated that ischemia and neuroinflammation can prompt M1

microglia to secrete cytokines, which in turn induce astrocytes to

transform into the neurotoxic A1 phenotype. These A1 astrocytes

typically display reduced normal functions and significantly

upregulate numerous genes previously shown to be detrimental to

synapses. Additionally, A1 astrocytes may secrete neurotoxins,

contributing to the death of neurons and oligodendrocytes (18). By contrast, A2 astrocytes appear

to upregulate neurotrophic factors or anti-inflammatory genes that

promote neuronal survival and growth, and support repair functions,

such as TGF-β, which can promote synaptogenesis and exhibit

neuroprotective effects against cerebral ischemic injury (19). To ascertain the relative roles of

A1/A2 astrocytes in CNS diseases, intervention with the critical

intracellular and extracellular signaling pathways that drive the

polarization of astrocytes into either beneficial or detrimental

phenotypes is necessary. Research strongly indicates that the

Stat3-mediated signaling pathway may be crucial for A2 astrocytes

to proliferate and support neuronal regeneration in acute injury

models, while the NF-κB signaling pathway may underlie the

induction of A1 astrocytes (20,21). While the simplistic A1/A2

dichotomy does not fully capture the broad spectrum of astrocyte

phenotypes, it provides a valuable framework for understanding

astrocyte reactivity in various CNS diseases.

Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) is a type of

intermediate filament protein specifically expressed in astrocytes

within the central and peripheral nervous systems. It plays a

crucial role in maintaining the morphology, structure and function

of astrocytes, while also participating in their reactive and

proliferative processes. In the event of ischemic stroke, oxygen

levels in the brain tissue decrease, leading to damage to

surrounding cellular tissues. Consequently, astrocytes become

activated and release GFAP, which subsequently enters the

bloodstream through the compromised BBB. In patients with acute

ischemic stroke, serum GFAP levels exhibit a moderate positive

correlation with the degree of neurological deficit and brain

injury as assessed by the National Institutes of Health Stroke

Scale (NIHSS) score. Elevated serum GFAP levels are associated with

higher NIHSS scores, indicating more severe neurological deficits

(22). Furthermore, high serum

GFAP levels serve as a marker for poor neurological prognosis in

patients with ischemic stroke, enabling the prediction of

neurological outcomes one-year post-stroke (23). The overview of astrocyte related

to ischemic stroke is demonstrated in Table I (16,17,24-33).

| Table IOverview of astrocyte related to

ischemic stroke. |

Table I

Overview of astrocyte related to

ischemic stroke.

| First author/s

year | Object of

study | Cohort

description | Sample type | Outcome

characteristics | Microbiota analysis

approach | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Zamanian et

al, 2012 | Mice from the

transgenic mouse line | Transient ischemia

was induced by occluding the MCAO | Brain tissues | Reactive astrocyte

phenotype strongly depended on the type of inducing injury | Affymetrix GeneChip

arrays | (17) |

| Song et al,

2020 | SD rats | Rats subjected to

MCAO/R | Brain tissues | Increase the

glutamate disposal by astrocytes and protecte neurons from

excitotoxicity in response to I/R insults | Decrease the

oxidative stress mediated by SDH | (24) |

| Shi et al,

2021 | MEGF10-flox founder

mice | The surgery of

MCAO | Brain tissues | Reactive

microgliosis and astrogliosis hinder brain repair by engulfing

synapses | Immunostaining,

fluorescence in situ hybridization, western blotting,

quantitative PCR, Golgi-Cox staining | (25) |

| Williamson et

al, 2021 | C57BL/6 mice | Photothrombotic

infarcts were created in forelimb motor cortex | Vasculature | Reactive astrocytes

are crucial for vascular repair and remodeling after ischemic

stroke in mice | In vivo

two-photon imaging | (26) |

| Ma et al,

2022 | C57BL/6 mice | tMCAO model | Brain tissues | Significant

differences in the expression of genes and metabolic pathways in

the astrocytes at 12 and 24 h after ischemic stroke | Single-cell

sequencing | (27) |

| Denecke et

al, 2022 | Cell | Rat astrocytes were

cultured in rat astrocyte basal medium containing growth serum | Cells | When subjected to

hypoxia, and nutrient starvation, astrocytes within the penumbral

region generated in the microdevice exhibited long-lasting,

significantly altered signaling capacity | polystyrene-based

microfluidic device | (28) |

| Wang et al,

2023 | C57BL/6 mice | reversible right

MCAO surgery | Brain tissues | Astrocyte-derived

KLF4 has a critical role in regulating the activation of A1/A2

reactive astrocytes following AIS | Immunofluorescent

staining, antibodies, RNA extraction, reverse-transcription,

western blot analysis and quantitative PCR | (16) |

| Lochhead et

al, 2023 | SD rats | MCAO surgery | Brain tissues | Astrocyte

activation may contribute to or be in response to neurodegeneration

following MCAO | Confocal microscopy

strategy, TTC Staining, Laser Doppler Blood Flow,

immunofluorescence staining | (29) |

| Zhou et al,

2024 | C57BL/6J mice | Transient focal

cerebral ischemia was induced by right MCAO | Brain tissues | Astrocytic LRP1

regulated the transfer of healthy mitochondria from astrocytes into

neurons and protected against brain ischemia-reperfusion

injury | Extracellular

mitochondria collection | (30) |

| Scott et al,

2024 | C57/Bl6J mice | Stroke-injured or

uninjured controls | Cells | The acquisition of

different astrocytic states after stroke that are influenced by

time and proximity to the stroke lesion site | tDISCO alongside

two high-throughput platforms for spatial (Visium) and single-cell

transcriptomics (10X Chromium) | (31) |

| Wang et al,

2024 | C57BL/6J mice | The barrel cortex

ischemic stroke | Brain tissues | A2 astrocytes and

A1 astrocytes are enriched in the acute and chronic phases of

ischemic stroke respectively | Flow cytometry,

Total RNA extraction, RNA-Seq, quantitative PCR, Vibrissae-Evoked

Forelimb-Placing Test, Immunofluorescence | (32) |

| Bormann et

al, 2024 | Wistar rats and

mice | Cerebral ischemia

was induced by intraluminal occlusion of the MCAO | Brain tissues | Astrocytes belong

to one of the most transcriptionally perturbed populations and

exhibit infarct and subtype specific molecular features. | Single nucleus RNA

sequencing, immunofluorescence | (33) |

The role of astrocyte in ischemic

stroke

A close connection between astrocytes and the

pathogenesis of CNS diseases has been recently suggested (34). Alzheimer's disease (AD) is the

most prevalent progressive neurodegenerative disorder,

characterized clinically by comprehensive dementia manifestations

such as memory impairment, aphasia, apraxia and agnosia. It

constitutes the primary cause of dementia in the elderly. In AD,

astrocytes undergo sustained activation and release significant

levels of inflammatory cytokines and neurotoxic substances. This

process triggers or exacerbates the hyperphosphorylation pathology

of tau protein and amyloid-β protein, thereby facilitating the

formation of amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, as well

as contributing to neuronal death and the decline of cognitive

function (35-37). Furthermore, the distinct

pathological phenotypes they develop may exert crucial influences

on the progression of AD (38).

Parkinson's disease (PD), the second most common neurodegenerative

disorder, is primarily characterized by heterogeneous classic motor

features associated with Lewy bodies and the loss of dopaminergic

neurons in the substantia nigra. Additionally, it exhibits

clinically significant non-motor features. Research has

demonstrated that patients with PD exhibit abnormal proliferation

and increased senescence of astrocytes in the brain, which

participate in inflammatory responses within the substantia nigra,

thereby promoting disease progression (39-41). Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a

neurological autoimmune disorder primarily characterized by

inflammatory demyelination in the white matter of the CNS,

ultimately leading to progressive physical disability in patients.

Astrocytes play a pivotal role in MS by modulating immune responses

and inflammatory reactions, thereby influencing the severity and

progression rate of the disease (42-44). Furthermore, ischemic stroke, as

another prevalent disorder of the CNS, is also intimately

associated with abnormal functions of astrocytes.

Dual roles of glial scar formation

In the pathological process of ischemic stroke,

astrocytes exhibit diverse roles in the CNS, with a notable

response being the formation of glial scars. During the acute phase

of the disease, this process aids in sealing the injury site,

remodeling tissues, and controlling local immune responses.

However, during the recovery phase, it may restrict the recovery of

neurological function.

At the onset of the disease, damaged cells produce

and release cytokines, triggering reactive proliferation of

astrocytes that migrate towards the injury area to form glial scars

(45). The formation of glial

scars helps limit the spread of inflammatory reactions, reduces

further tissue damage, and provides a physical barrier around the

injured area to prevent the infiltration of harmful substances,

thus maintaining CNS homeostasis and creating conditions for

subsequent repair processes. However, during neural recovery,

excessive formation and persistence of glial scars become physical

barriers that hinder neuronal synaptic reconnection. Glial scars

are primarily composed of proliferated astrocytes and the

extracellular matrix proteins they secrete, forming a dense barrier

that severely impedes neuronal regeneration and axonal extension.

Additionally, glial scars may further inhibit the neural repair

process by releasing inhibitory factors, leading to limited

restoration of neurological function (46).

Mediation of inflammatory response and

oxidative stress

Astrocytes actively participate in the regulation of

inflammatory responses and oxidative stress in ischemic stroke.

Inflammatory response, while being one of the primary causes of CNS

injury, can exacerbate brain tissue damage when excessive.

Following ischemic stroke, astrocytes are activated into reactive

astrocytes, releasing a surge of inflammatory factors and inducing

the production of neurotoxic mediators. This inflammatory response

leads to the disruption of the BBB and the upregulation of cellular

adhesion molecules, increasing the permeability of the BBB and

allowing immune cells to infiltrate into brain tissues. This fact

further triggers inflammatory reactions such as cerebral edema,

ultimately resulting in neuronal cell death (47). Concurrently, astrocytes can also

release anti-inflammatory neuroprotective factors, attracting

immune cells, clearing necrotic tissues, and promoting tissue

repair, thereby inhibiting inflammation (48).

During ischemic stroke, the severe inflammatory

response caused by ischemia and hypoxia in brain tissue induces the

production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and other oxidative

products in large concentrations, resulting in the accumulation of

numerous free radicals in the body. This, in turn, damages cell

structures and human tissues, triggering an oxidative stress

response. As the primary glial cell type in the CNS, astrocytes

rapidly respond to this stress state by upregulating the expression

and activity of antioxidant enzymes to combat excessive ROS

accumulation and mitigate damage to neurons and their own cells.

Glutathione (GSH) is a crucial antioxidant and free radical

scavenger that participates in redox reactions in the body. It

binds to peroxides and free radicals, reducing ROS toxicity and

serving as a key factor in preventing the aggravation of ischemic

injury in brain tissue. Studies have shown that astrocytes are rich

in GSH and enzymes related to GSH metabolism. By enhancing the

synthesis and release of antioxidants such as GSH and storing

nitric oxide in the cytoplasm, astrocytes can reduce oxidative

stress toxicity, alleviate oxidative stress damage to neurons, and

thereby promote neuronal survival (49-51).

Antagonizing neurotoxicity and promoting

neurological recovery

Glutamate is the primary excitatory neurotransmitter

in the CNS, responsible for virtually all excitatory synaptic

activities in the brain. This crucial amino acid circulates

extensively between neurons and astrocytes, known as the

glutamate-glutamine cycle. Extracellular glutamate is taken up by

nearby astrocytes, converted into glutamine, which then migrates to

the extracellular environment, enters presynaptic neurons, and is

reconverted into glutamate (52). In the early stage of ischemic

stroke, the brain tissue suffers from ischemia and hypoxia, leading

to reduced ATP production, gradual energy depletion, and impaired

ion pump function, which results in presynaptic calcium overload.

The subsequent accumulation of glutamate in the synapses activates

post-synaptic glutamate receptors, causing post-synaptic calcium

overload, initiating profound neurotoxicity, and ultimately

triggering neuronal death (53).

Astrocytes can effectively remove glutamate from the synaptic cleft

by expressing high-affinity glutamate transporters, maintaining its

homeostatic levels and preventing excessive neuronal excitation and

damage (54). Synaptic

regeneration after neural injury is a crucial process that enhances

neural plasticity, and astrocytes contribute to this process in

multiple ways. The close morphological relationship between

astrocytic membranes and pre- and post-synaptic neurons, along with

the widespread expression of neurotransmitter receptors in

astrocytes, forms the astrocytic tripartite synapse. This structure

prevents the diffusion of neurotransmitters from the synapse and

serves as an important structural unit in the nervous system

(55). Besides, astrocytes

facilitate the release of various growth factors and neurotrophins.

These factors are vital during ischemia for neuronal survival and

growth, angiogenesis, synaptic regeneration, and the restoration of

other neurological functions (56).

Transformation into neurons

Astrocytes are the most widely distributed cells in

the CNS, and they can rapidly activate and proliferate under

pathological conditions, making them the ideal target cell type for

induction into neuronal cells (57). Reactive astrocytes can transform

into neurons under specific circumstances (58). Although neural stem cells (NSCs)

are the primary source of endogenous neural repair, their migratory

capacity is limited. When the site of injury is far from the region

where NSCs reside, reactive astrocytes can be activated through

neurogenic programs, acquiring certain stem cell properties, and

then re-differentiating into neurons to promote local neuronal

regeneration. In addition, astrocytes also aid in the migration of

differentiated NSCs (59,60).

Astrocyte metabolic reprogramming in

ischemic stroke

In recent years, with the deepening of research into

neurological diseases, the metabolic flexibility and functional

diversity of astrocytes have garnered increasing attention, and

notable advancements have been made in the study of metabolic

reprogramming of astrocytes. Research has revealed that mutations

in the intellectual disability-associated gene SNX27 can induce

metabolic reprogramming of astrocytes, subsequently impairing

cognitive functions. Specifically, SNX27 mutations lead to a

decreased ability of astrocytes to uptake glucose via GLUT1,

resulting in reduced lactate production and a transition from

homeostatic astrocytes to reactive astrocytes. This transformation

impacts the energy supply to neighboring neurons (61). Additionally, astrocytes possess

the capacity to modulate the pathogenicity of glioblastoma by

reprogramming the immune characteristics of the tumor

microenvironment and supporting the non-oncogenic metabolic

dependence of glioblastoma on cholesterol (62).

Astrocytes form functional networks through gap

junctions, enabling intercellular communication with other cells

via various mechanisms, playing a crucial role in maintaining

homeostasis within the CNS (63). The unique cellular structure and

quantitative characteristics of astrocytes confer upon them a high

degree of metabolic plasticity, allowing them to adjust their

metabolic pathways in response to environmental changes and

physiological demands. They not only harness glucose for energy

production through glycolysis and aerobic oxidative phosphorylation

but also acquire energy and synthesize essential biomolecules

through fatty acid and amino acid metabolism pathways (64). However, during ischemic stroke,

local cerebral blood flow is reduced or interrupted due to cerebral

vascular occlusion, leading to insufficient oxygen supply and a

precipitous decline in energy supply. In this emergent situation,

astrocytes promptly respond by initiating metabolic reprogramming

to adapt to the energy crisis.

Astrocyte glucose metabolism in ischemic

stroke

Glucose serves as the primary energy source for the

brain, and its metabolism directly impacts brain function,

particularly the interplay between astrocytes and neurons (65). Under normal physiological

conditions, astrocytes efficiently uptake glucose via glucose

transporter proteins. Once inside the cell, glucose is initially

phosphorylated to glucose-6-phosphate (G6P), marking the crucial

initiating step in glucose metabolism. G6P then bifurcates into two

primary metabolic routes: glycolysis and the pentose phosphate

pathway (PPP). Glycolysis, one of the major branches of glucose

metabolism, involves the gradual degradation of G6P into pyruvate,

generating small amounts of ATP and NADH along the way. In aerobic

conditions, the majority of pyruvate enters mitochondria where it

undergoes complete oxidation to carbon dioxide and water through

the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, releasing substantial energy

for ATP synthesis. This process is known as aerobic oxidative

phosphorylation (66).

Furthermore, astrocytes also retain the capacity to convert a

portion of pyruvate into lactate, which can be released

extracellularly to regulate pH balance and contribute to energy

supply. The PPP, as a shunt from glycolysis, diverges at G6P and is

catalyzed by G6P dehydrogenase, yielding NADPH and 5-phosphoribose,

among other products. NADPH, an essential cytosolic reductive

equivalent, effectively scavenges ROS, thereby safeguarding cells

from oxidative stress damage. Consequently, PPP activity is often

regarded as an important indicator of cellular antioxidant defense.

Notably, under hypoxic conditions, astrocytes upregulate glucose

flux towards the PPP to provide additional NADPH for GSH synthesis,

thereby protecting neurons from oxidative insult (67). During ischemic stroke, localized

hypoxia in brain tissue ensues due to reduced blood flow,

concurrently diminishing glucose and oxygen supply. In response to

this emergency, astrocytes reprogram their glucose metabolic

pathways by enhancing glucose uptake, accelerating glycolysis, and

increasing lactate release. These concerted changes collectively

enhance the tolerance of astrocytes to ischemic and hypoxic

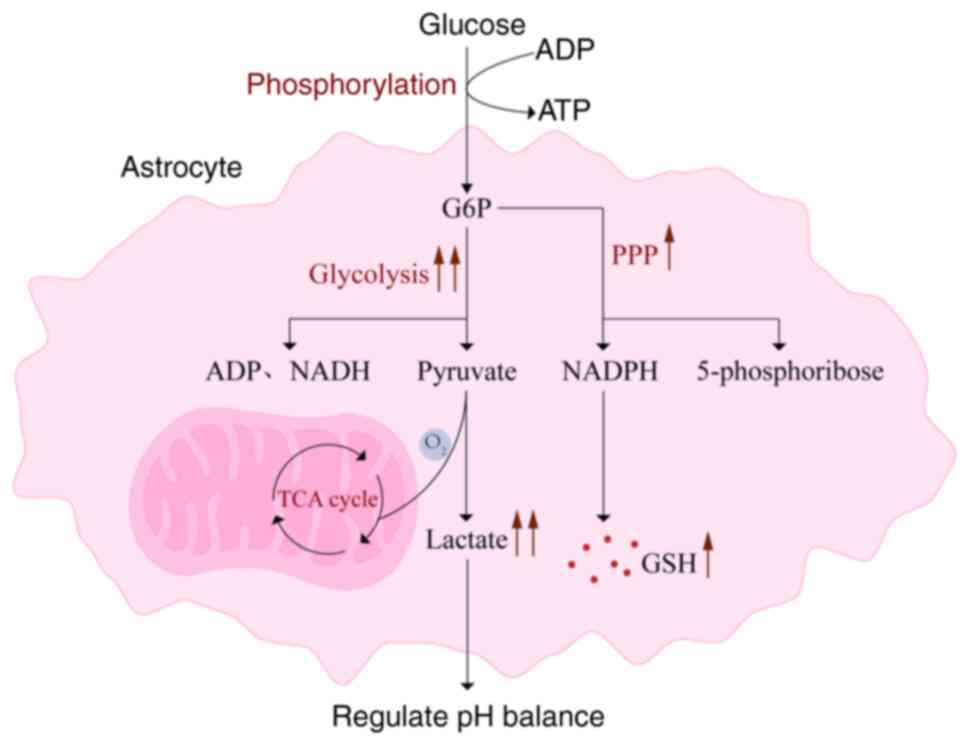

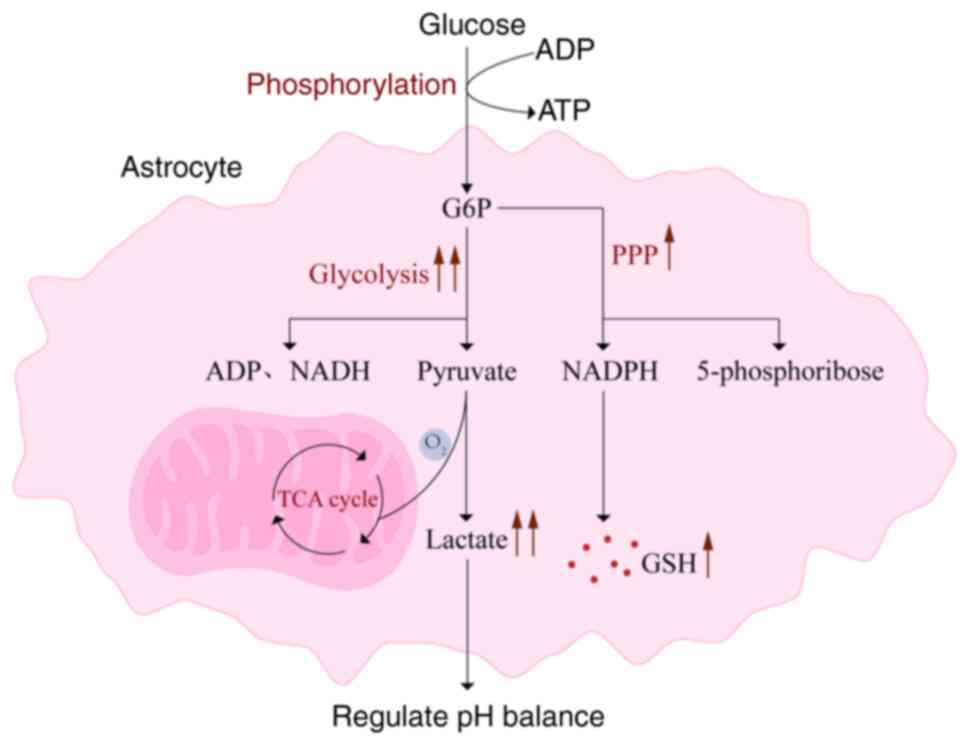

environments (68) (Fig. 1).

| Figure 1Astrocyte glucose metabolism in

ischemic stroke. Under normal physiological conditions, astrocytes

efficiently uptake glucose via glucose transporter proteins. Upon

entering the cell, glucose is initially phosphorylated to G6P.

Subsequently, G6P diverges into two primary metabolic pathways:

glycolysis and the pentose phosphate pathway. In glycolysis, G6P is

gradually degraded into pyruvate. Under aerobic conditions, the

majority of pyruvate enters the mitochondria and undergoes complete

oxidation to carbon dioxide and water through the TCA cycle,

releasing substantial energy for ATP synthesis. Meanwhile, a

portion of pyruvate is converted into lactate, which is released

extracellularly. In the PPP, G6P is catalyzed by G6PDH to yield

NADPH and 5-phosphoribose, among other products. During ischemic

stroke, astrocytes reprogram their glucose metabolic pathways by

enhancing glucose uptake, accelerating glycolysis, and increasing

lactate release. G6P, glucose-6-phosphate; TCA, tricarboxylic acid;

G6PDH, G6P dehydrogenase; PPP, pentose phosphate pathway. |

Astrocytes enhance their glucose uptake capacity by

upregulating the expression of glucose transporter proteins, with

GLUT1, a 45 kDa subtype, being primarily responsible for basal

glucose transport in astrocytes (69). GLUT1 is a transmembrane protein

widely distributed in vascular endothelial cells of the BBB and

various brain tissue cells. It exhibits high specificity and

affinity, enabling rapid transfer of glucose from the bloodstream

into cells, providing essential energy sources (70). During ischemia, astrocytes

increase the quantity and activity of GLUT1 to ensure enhanced

glucose influx into the cells, meeting the urgent metabolic demands

(71). By enhancing glucose

uptake efficiency, astrocytes sustain a certain level of energy,

enabling them to continue supporting neuronal function and

regulating the intracranial environment. Under hypoxic conditions

resulting from ischemic stroke, the aerobic oxidative

phosphorylation pathway is severely inhibited, leading to a drastic

reduction in ATP production. In response to this energetic crisis,

most eukaryotic cells reprogram their primary metabolic route,

shifting from mitochondrial respiration to glycolysis, in order to

sustain ATP levels. This hypoxia-induced metabolic reprogramming is

crucial for meeting cellular energy demands during acute hypoxic

stress (72). Glycolysis, a

glucose metabolic pathway that operates even under anaerobic or

hypoxic conditions, albeit generating fewer ATP molecules compared

with aerobic oxidative phosphorylation, operates at a faster rate

and is independent of oxygen. By enhancing the proportion of

aerobic glycolysis, astrocytes can rapidly generate sufficient ATP

to maintain fundamental cellular functions, which is pivotal in

preserving cellular stability and preventing further damage.

However, this process also leads to a corresponding elevation in

lactate levels, which promotes the formation of Kla protein,

significantly exacerbating brain injury in ischemic stroke

(73). Excessive accumulation of

lactate also causes a significant decrease in cellular pH, exposing

brain tissue to acidosis-induced damage (74). To alleviate this crisis,

astrocytes not only adapt to their own metabolic changes but also

release lactate into the extracellular space through the lactate

shuttle mechanism. This lactate is then taken up by neurons,

serving as an alternative energy source under hypoxic conditions.

Through gluconeogenesis, it can be reconverted into glucose or

enter the TCA cycle for oxidative phosphorylation to generate ATP,

thereby effectively protecting neurons from further damage. This

process is known as the astrocyte-neuron lactate shuttle (75). Not only does this process provide

crucial energy support for neurons, but it also promotes the

recycling of glucose and lactate within the brain, enhancing

overall metabolic efficiency.

Astrocyte fatty acid metabolism in

ischemic stroke

As the preferred energy substrate for the brain,

when glucose supply decreases, fatty acid oxidation and the

resulting ketone bodies (KBs) become the primary alternative energy

sources, assisting in maintaining the stability of neuronal

synaptic function and structure (76). Astrocytes serve as the primary

site of fatty acid oxidation in the brain (77). Fatty acids first enter astrocytes

through specific transporters and are then stored as lipid droplets

(LDs) in the endoplasmic reticulum. When needed, these LDs are

converted into fatty acyl-CoA and transported to mitochondria to

participate in β-oxidation, ultimately generating acetyl-CoA, which

enters the TCA cycle and other pathways to produce energy.

Furthermore, fatty acids are transported to support myelin

formation or regeneration. Additionally, astrocytes are the primary

source of KBs production in the brain (78).

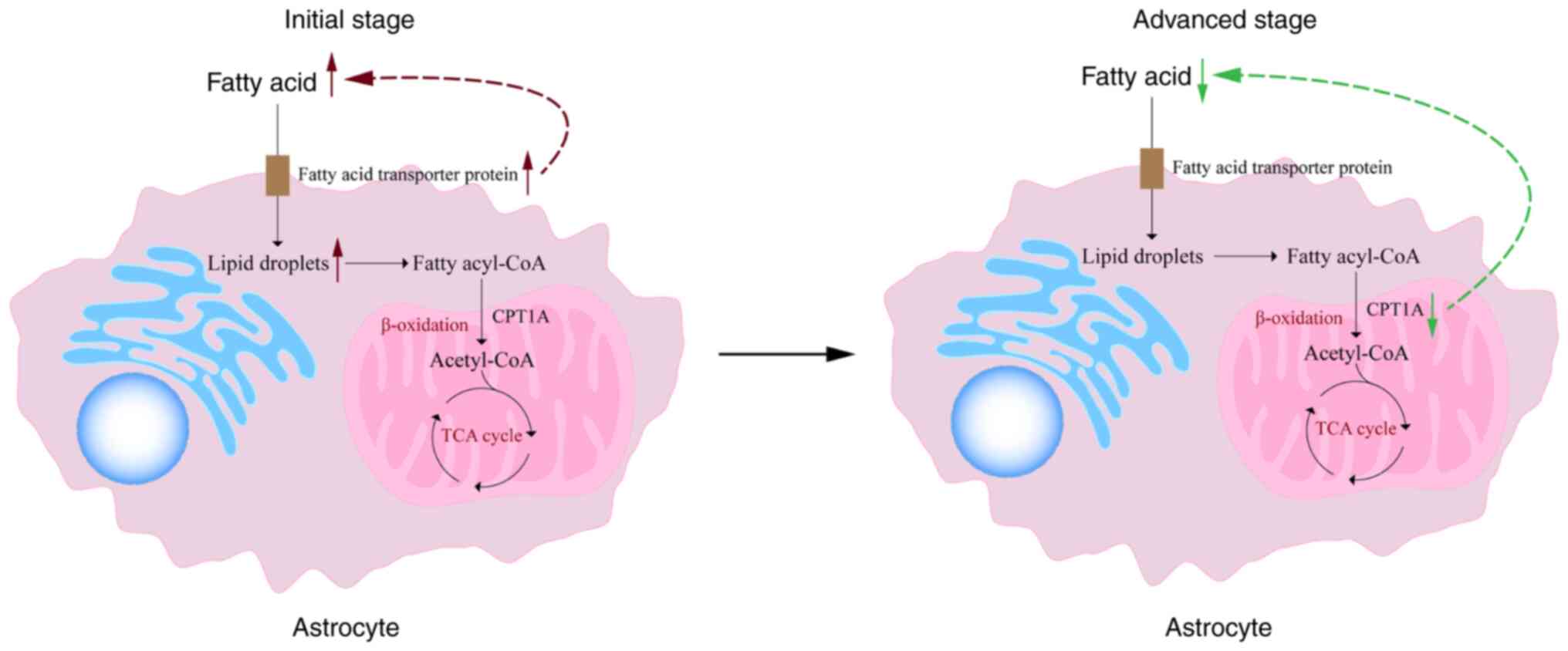

Under normal physiological conditions, fatty acid

oxidation constitutes a pivotal pathway for astrocytes to derive

energy. However, during ischemic stroke, the brain tissue rapidly

becomes ischemic and hypoxic, necessitating a steep rise in

neuronal energy demands. In response to this energy crisis,

astrocytes swiftly engage their distinctive metabolic adaptation

mechanisms. They upregulate the expression of fatty acid

transporter proteins, such as fatty acid-binding proteins, to

augment their capacity for fatty acid uptake and concurrently

activate lipid synthesis pathways to augment intracellular fatty

acid storage. While this process may be somewhat hindered by the

deficient energy supply, astrocytes persist in maintaining their

metabolic functions (79).

Nevertheless, excessive expression of fatty acid transporter

proteins in ischemic stroke is not uniformly beneficial. In certain

scenarios, it may lead to lipid droplet accumulation within

astrocytes, further impeding normal cellular physiology. LDs,

fundamental components of astrocytic lipid metabolism, modulate

fatty acid storage and hydrolysis in eukaryotes (80). Their primary purpose is to

provide fuel for fatty acid oxidation, offering an alternative

energy-generating route for astrocytes and other tissues during

energy source depletion, ensuring an adequate fatty acid reserve

for cell survival and neuronal metabolism (81). At the onset of ischemia and

hypoxia, astrocytes intensify fatty acid oxidation and breakdown to

generate more ATP, crucial for maintaining cellular survival and

fulfilling neuronal energy demands, thereby conferring

neuroprotection. Consequently, metabolites associated with fatty

acid catabolism may elevate initially (82). Yet, over time, mitochondrial

dysfunction and impairment of oxidative phosphorylation may hinder

effective fatty acid entry into mitochondria, suppressing fatty

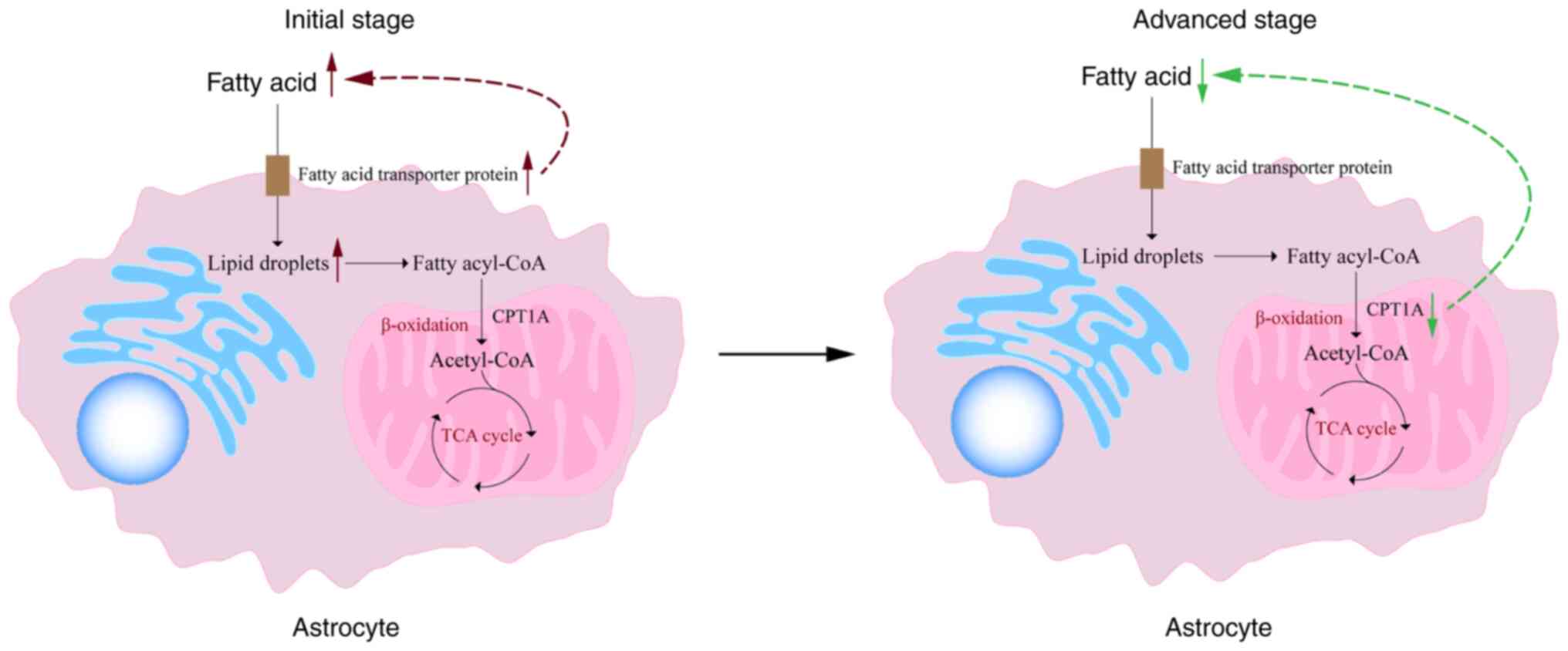

acid oxidation (83) (Fig. 2). Additionally, reduced activity

of vital enzymes such as carnitine palmitoyl-transferase 1A

(CPT1A), a crucial regulator for long-chain fatty acid entry into

mitochondria for oxidation, further decelerates fatty acid

oxidation rates. The decreased CPT1A activity directly contributes

to reduced fatty acid oxidation, instigating fatty acid metabolic

disturbances and exacerbating the energy supply crisis (84).

| Figure 2Astrocyte fatty acid metabolism in

ischemic stroke. Fatty acids initially enter astrocytes through

specific transporter proteins and are subsequently stored as LDs in

the endoplasmic reticulum. These LDs are converted into fatty

acyl-CoA when needed and transported to mitochondria to participate

in β-oxidation, ultimately generating acetyl-CoA, which enters the

TCA cycle and other pathways to produce energy. However, following

ischemic stroke, astrocytes upregulate the expression of fatty acid

transporter proteins, leading to the accumulation of LDs within

astrocytes. Over time, mitochondrial dysfunction and impairment of

the oxidative phosphorylation pathway may prevent fatty acids from

effectively entering mitochondria, thereby inhibiting the

progression of fatty acid oxidation. LDs, lipid droplets; TCA,

tricarboxylic acid; CPT1A, carnitine palmitoyl-transferase 1A. |

Astrocyte amino acid metabolism in

ischemic stroke

In parallel with energy metabolic pathways, amino

acid metabolism within astrocytes plays a pivotal role in

regulating brain function. As fundamental constituents of proteins,

amino acids not only participate in protein synthesis and

degradation but also modulate neuronal excitability, synaptic

plasticity, and the synthesis and release of neurotransmitters

through their transport and metabolic processes.

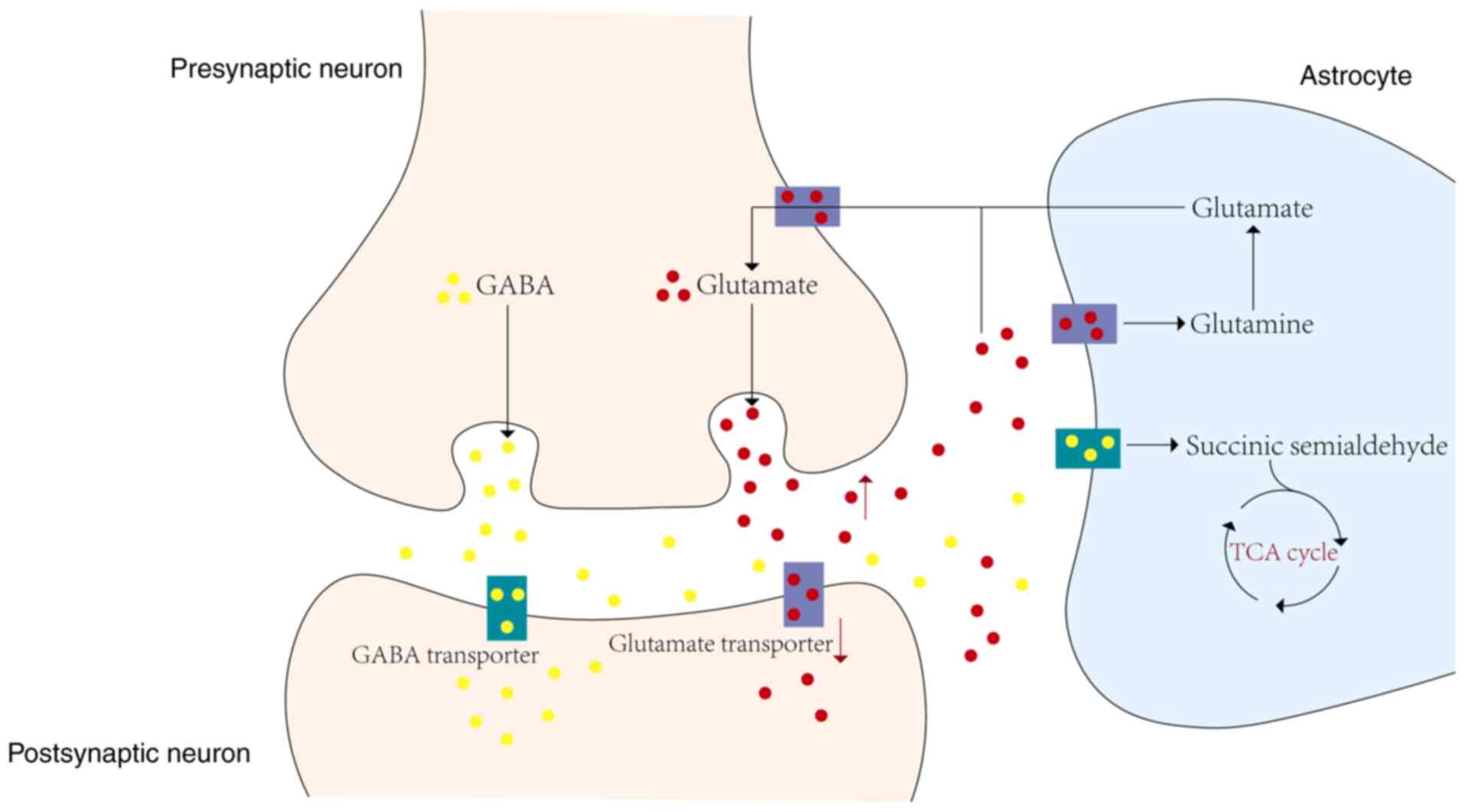

Glutamate serves as the primary excitatory

neurotransmitter in the CNS, with neurons and astrocytes being the

primary players in its metabolism. The exchange of glutamate,

γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), and glutamine between these two cell

types, known as the glutamate/GABA-glutamine cycle, is crucial for

maintaining CNS homeostasis (85). During cerebral ischemia and

hypoxia, neuronal damage leads to the release of excess glutamate

into the synaptic cleft, where it acts as an excitatory

neurotransmitter binding to post-synaptic receptors. Under these

conditions, the expression of excitatory glutamate transporters

such as GLT-1 and GLAST-1 is significantly downregulated, resulting

in reduced clearance of glutamate from the synaptic cleft (86). The subsequent accumulation of

glutamate excessively stimulates post-synaptic neurons, leading to

excitotoxicity. A portion of the unbound glutamate is sequestered

by astrocytes through high-affinity glutamate transporters and

converted to glutamine within the cells, thereby reducing

extracellular glutamate concentrations and protecting neurons from

excitotoxic damage to a certain extent. In some instances, this

unbound glutamate may also be retrogradely transported back to

neurons via glutamate transporters, participating in new rounds of

neurotransmission (87).

Additionally, astrocytes have been shown to release small amounts

of glutamate to surrounding neurons, contributing to the

synchronization of action potential firing and regulating neural

excitability transmission (88).

Concurrently, GABA, synthesized by neurons, is released as an

inhibitory neurotransmitter to dampen post-synaptic neuronal

excitability. Imbalances between excitatory and inhibitory

neurotransmitter signaling contribute to the onset of

excitotoxicity. After release, GABA can also be taken up by

astrocytes, where it is converted to succinic semialdehyde by GABA

transaminase and enters the TCA cycle for energy metabolism

(89). Moreover, astrocytes can

synthesize and release GABA into the extracellular space,

fine-tuning local neural networks (90). However, extensive uptake of

glutamate and GABA by astrocytes depletes the corresponding

neurotransmitter pools in neurons. To counteract this, astrocytes

convert ingested glutamate into glutamine and shuttle it back to

neurons via the glutamine-glutamate cycle for reuse, which is

essential for replenishing glutamate and GABA at neuronal terminals

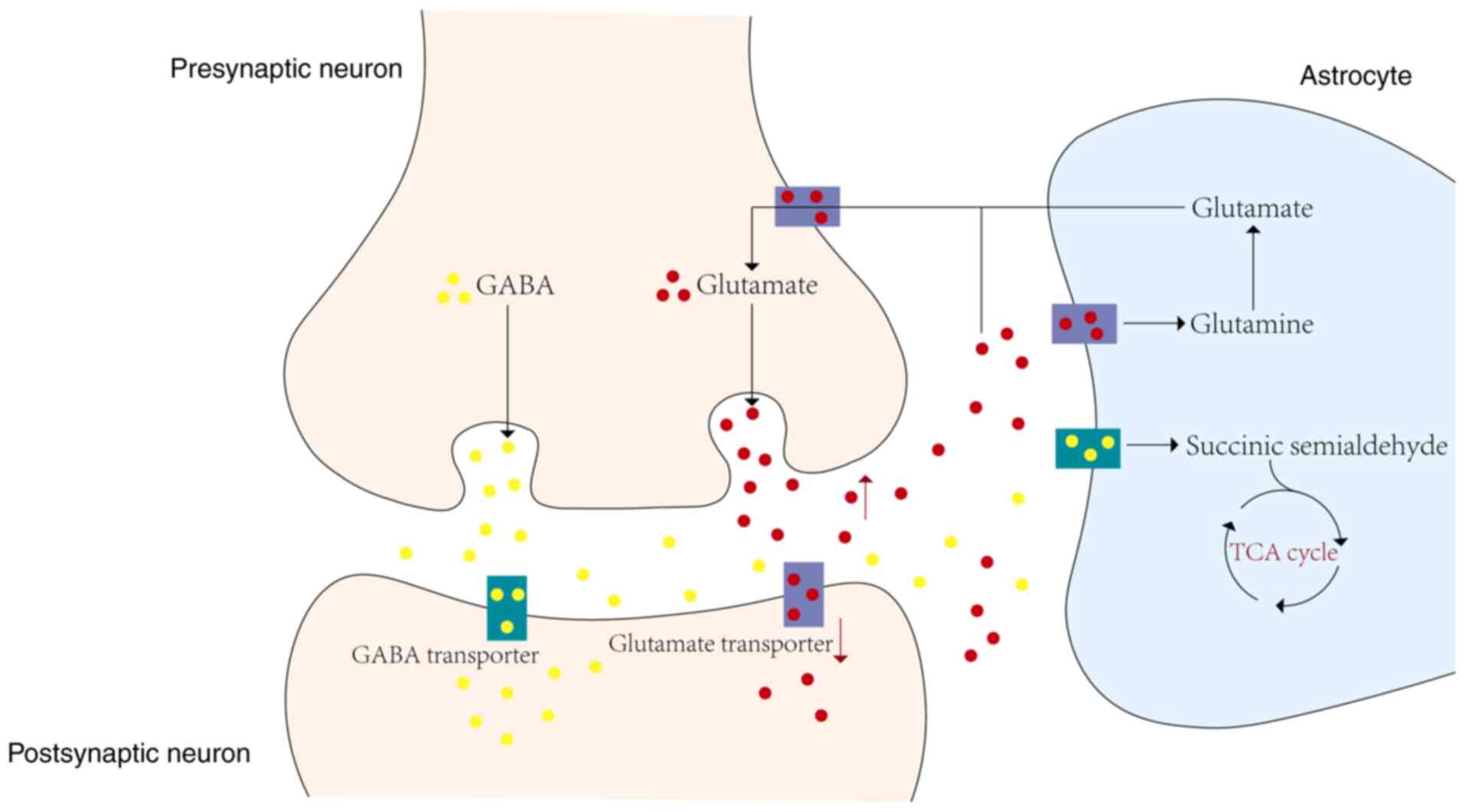

(91) (Fig. 3).

| Figure 3Astrocyte amino acid metabolism in

ischemic stroke. When the brain is in a state of ischemia and

hypoxia, a substantial level of glutamate is released into the

synaptic cleft, resulting in a significant downregulation of

excitatory glutamate transporters expression. This leads to a

reduction in the efficiency of glutamate clearance from the

synaptic cleft. Among the glutamate released, some that is not

bound by post-synaptic neurons is received by astrocytes via

high-affinity glutamate transporters and converted into glutamine

within the cells. In certain circumstances, this unbound glutamate

may also be directly retrogradely transported back to neurons via

glutamate transporters, participating in a new round of

neurotransmission. Simultaneously, GABA, synthesized by neurons, is

released as an inhibitory neurotransmitter to inhibit the

excitability of post-synaptic neurons. The imbalance between the

release of excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitter signals leads

to the occurrence of excitotoxicity. Released GABA can also be

taken up by astrocytes and converted into succinate semialdehyde

via GABA transaminase within the astrocytes, entering the TCA cycle

for energy metabolism. However, the extensive uptake of glutamate

and GABA by astrocytes depletes the corresponding neurotransmitter

pools in neurons. To counteract this, astrocytes convert the

received glutamate into glutamine and transport it back to neurons

through the glutamine-glutamate cycle for reuse, which is crucial

for replenishing glutamate and GABA at neuronal terminals. GABA,

γ-aminobutyric acid; TCA, tricarboxylic acid. |

In the pathological process of ischemic stroke,

metabolic reprogramming of astrocytes plays a pivotal role. From

the basal metabolism, glucose metabolism, fatty acid metabolism, to

amino acid metabolism of astrocytes, all aspects exhibit adaptive

changes to ischemic and hypoxic environments. Such metabolic

reprogramming not only enhances the survival capacity of astrocytes

but also provides robust support for neuronal and brain tissue

repair by modulating various aspects including antioxidation,

energy supply, inflammatory response and neuroprotection.

Consequently, a profound understanding of the mechanisms underlying

metabolic reprogramming of astrocytes in ischemic stroke holds

significant importance for the development of novel therapeutic

strategies.

Regulatory factors of astrocyte metabolic

reprogramming in ischemic stroke

Hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs) constitute pivotal

transcription factors that are responsive to intracellular oxygen

concentration fluctuations. Under hypoxic conditions, HIFs exert

transcriptional regulatory activity, governing the expression of an

array of metabolism-related genes, thereby facilitating cellular

and systemic adaptation to hypoxic environments. They also emerge

as crucial regulators in metabolic reprogramming of astrocytes. By

modulating the expression of an extensive network of target genes,

HIFs orchestrate reprogramming of astrocyte pathways associated

with glucose metabolism, fatty acid metabolism and amino acid

metabolism, markedly enhancing astrocytic resilience against

ischemic and hypoxic insults. In ischemic stroke, the ensuing

inflammatory response and cellular damage induced by ischemia and

hypoxia activate various signaling cascades. Numerous of these

pathways are intricately linked to the reactivity of astrocytes,

with the Jak-STAT3 signaling pathway playing a pivotal role in

coordinating the proliferation of reactive astrocytes by modulating

the production of cytokines and chemokines. This pathway serves as

a central regulatory hub for numerous molecular and functional

alterations in reactive astrocytes (92). A previous study revealed a marked

upregulation of the transcription factor STAT3 in reactive

astrocytes following ischemic stroke (93). STAT3 has been demonstrated to

control phenotypic changes and metabolic reprogramming of

astrocytes during the inflammatory phase of ischemic stroke,

upregulating lactate-directed glycolysis while impeding

mitochondrial function, thus serving as a key modulator of

astrocyte phenotype, metabolic shift and associated neurotoxicity.

Moreover, in reactive astrocytes, elevated expression of activated

pSTAT3 correlates with larger infarct sizes and reduced synaptic

densities in the peri-infarct zone (94). Beyond cell proliferation, STAT3

also regulates GFAP expression in reactive astrocytes, as the GFAP

promoter harbors STAT3 consensus binding sites essential for GFAP

induction. Consequently, the STAT3 signaling pathway emerges as a

promising pharmacological target for modifying reactive astrocytes

in the context of ischemic stroke (95).

Glycophagy, as a selective autophagy process for

glycogen, is emerging as a pivotal metabolic pathway for the

delivery of glycolytic fuel substrates, playing a crucial role in

maintaining cellular metabolic homeostasis in peripheral tissues

(96). It regulates cellular

redox homeostasis, glutamine utilization, fatty acid oxidation in

skeletal muscle, and lipid droplet formation in adipocytes

(97,98). Guo et al (99) discovered during reperfusion in

ischemic stroke patients and mice that dysfunction in glycophagy in

astrocytes is induced by the downregulation of GABA A

receptor-associated protein-like 1, with the activation of the

PI3K-Akt pathway also involved. Following ischemic stroke, as key

enzymes in glycolysis in astrocytes are inhibited, glucose sourced

from glycophagy enters the PPP more significantly than it does

glycolysis and the TCA cycle. Restoring glycophagy in astrocytes

can not only enhance their resistance to ischemic and hypoxic

environments but also aid in the survival of nearby neurons when

the entire brain is under energy stress (99).

Therapeutic approaches targeting astrocyte

metabolic reprogramming in ischemic stroke

Currently, the frontline treatments for ischemic

stroke encompass intravenous administration of recombinant tissue

plasminogen activator (rt-PA) and mechanical thrombectomy (100). Nevertheless, due to their

narrow therapeutic windows, the options for treating ischemic

stroke remain limited. As such, the pursuit of novel candidate

drugs for ischemic stroke management poses an urgent challenge. In

the context of ischemic stroke, astrocytes undergo significant

metabolic reprogramming, transitioning from a quiescent state to a

reactive state. Thus, the therapeutic strategies targeting

metabolic reprogramming of astrocytes in ischemic stroke focus on

modulating their metabolic pathways and functional states, with the

aim of inhibiting excessive astrocyte activation or regulating the

ratio of A1/A2 phenotypes, thereby maximizing neuroprotective

effects while minimizing neurotoxicity, ultimately facilitating

repair and regeneration following brain injury.

In the early stages of ischemic stroke, due to blood

flow interruption, brain tissue experiences hypoxia, prompting

astrocytes to shift towards anaerobic glycolysis for rapid ATP

production. However, this metabolic pathway is prone to lactate

accumulation, leading to acidosis. Following ischemic reperfusion,

astrocyte glycogen mobilization augments the production of NADPH

and GSH via the PPP, resulting in a reduction in ROS levels. This,

in turn, triggers the inhibition of the NF-κB signaling pathway and

the activation of the STAT3 signaling pathway, ultimately leading

to the suppression of A1 astrocytes and the enhancement of A2

astrocytes (101). HIF-1

enhances the intrinsic tolerance of brain tissue to ischemia by

augmenting glucose uptake in astrocytes, facilitating glycogen

synthesis, and initiating a metabolic shift towards glycolytic

energy production (68).

Similarly, AMPK exerts a specific influence on glycolysis during

ischemic preconditioning in brain tissue (102). These pathways present promising

therapeutic targets for addressing reperfusion injury in ischemic

stroke. Under ischemic and hypoxic stimuli, astrocytes release free

fatty acids from LDs into mitochondria, causing mitochondrial

damage, reducing metabolic support from astrocytes, and thereby

exacerbating neuronal injury (103). Cao et al (104) revealed that n-3 polyunsaturated

fatty acids can decrease the cerebral infarction volume and improve

neurological function in mice with transient middle cerebral artery

occlusion. Additionally, it reduced the polarization of A1

astrocytes induced by ischemic stroke both in vivo and in

vitro (104). In addition,

the interaction between glutamate and astrocytes jointly influences

the pathological process of ischemic stroke. In ischemic stroke,

glutamate, acting as a neurotransmitter, experiences an abnormal

elevation in its levels, exerting neurotoxic effects on neurons.

Conversely, astrocytes are responsible for modulating the uptake

and metabolism of glutamate, thereby mitigating its deleterious

impact on neurons. However, to date, no literature has confirmed

the existence of drugs that target this mechanism to affect

astrocyte phenotype changes during ischemic stroke.

As a crucial therapeutic target in ischemic stroke,

promoting the differentiation of astrocytes towards the A2

phenotype may offer novel neuroprotective strategies with profound

therapeutic implications. Research has demonstrated that the

overexpression of the chemokine-like signaling protein

prokineticin-2 and its small molecule agonist IS20 in primary

astrocytes or in the brains of mice in vivo can induce the

A2 astrocyte phenotype. This leads to the upregulation of key

protective genes and A2 reactive markers, while simultaneously

reducing inflammatory cytokines (105). The TGF-β secreted by M2

macrophages potentially elicits the differentiation of astrocytes

towards the A2 phenotype through the activation of the PI3K/Akt

signaling cascade (106).

Furthermore, cytokines such as IL-4, IL-10 and IL-1β can induce the

differentiation of astrocytes towards the A2 phenotype in

vitro, further elucidating their protective and repair

functions under inflammatory responses (107,108). In summary, therapeutic

approaches aimed at restoring tissue damage and metabolic balance

in the brain through the modulation of astrocyte metabolic

reprogramming have emerged as promising targets for the treatment

of ischemic stroke. However, this area remains relatively

under-explored, and there is a pressing need for future research

endeavors to delve deeper into this domain. The relevant

therapeutic approaches targeting astrocyte metabolic reprogramming

in ischemic stroke are demonstrated in Table II (16,73,104,109-116).

| Table IITherapeutic approaches targeting

astrocyte metabolic reprogramming in ischemic stroke. |

Table II

Therapeutic approaches targeting

astrocyte metabolic reprogramming in ischemic stroke.

| First author/s,

year | Strategy | Regulation on

astrocytes polarization and metabolism | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Liu et al,

2020 | Cottonseed oil | Reduce A1 phenotype

neurotoxic astrocyte activation by inhibiting TLR4/NF-κB pathway,

which may affect glucose metabolism | (109) |

| Zhang et al,

2024 | AD16 | Reduce A1

polarization of astrocytes by downregulating NF-κB and JAK2/STAT3

pathways, which may affect glucose metabolism | (110) |

| Zou et al,

2024 | Scutellarin | Inhibit the

activation of astrocytes to A1 type by inhibiting the activation of

NF-κB pathway, which may affect glucose metabolism | (111) |

| Zhou et al,

2022 | Tetrahedral

framework nucleic acid | Facilitate the

astrocytic polarization from the proinflammatory A1 phenotype to

the neuroprotective A2 phenotype by downregulating the TLRs/NF-κB

pathway, which may affect glucose metabolism | (112) |

| Liu et al,

2024 | Genistein-3′-sodium

sulfonate | Enhance astrocyte

polarization to A2 phenotype by inactivating TLR4/NF-κB pathway,

which may affect glucose metabolism | (113) |

| Chen et al,

2024 | Edaravone

Dexborneol | Suppress activation

of neurotoxic A1 astrocytes by inhibiting NF-κB pathway, which may

affect glucose metabolism | (114) |

| Wang et al,

2023 | Kruppel-like

transcription factor-4 | Inhibit the

activation of A1 astrocyte and promote A2 astrocyte polarization by

modulating expressions of NF-κB pathway, which may affect glucose

metabolism | (16) |

| Li et al,

2024 | Buyang Huanwu

Decoction | Suppress astrocytes

A1 polarization and promote astrocyte A2 polarization by increasing

expression of phosphorylated AMPK and inhibiting NF-κB pathway,

which may affect glucose metabolism | (115) |

| Xia et al,

2024 | Gypenosides | Inhibit astrocytes'

polarization into the A1 type, by inhibiting STAT-3/HIF1-α and

TLR-4/NF-κB/HIF1-α pathways, which may affect glucose

metabolism | (116) |

| Xiong et al,

2024 | Oxamate | Inhibit the

activation of A1 astrocyte by inhibiting the production of lactate,

blocking the shuttle of lactate to neurons, and inhibiting the

formation of Kla protein, which may affect glucose metabolism | (73) |

| Cao et al,

2021 | N-3 polyunsaturated

fatty acids | Reduce the A1

astrocyte polarization both in vivo and in vitro by

attenuating mitochondrial oxidative stress and increasing the

mitophagy of astrocytes, which may affect fatty acid

metabolism | (104) |

Conclusions and perspectives

In conclusion, ischemic stroke, a prevalent and

devastating condition, poses significant challenges in terms of

disability and mortality globally. The current pharmacological

treatment, intravenous thrombolysis with rt-PA, while effective,

has notable limitations, necessitating the exploration of novel

therapeutic approaches. Astrocytes, as crucial and versatile cells

in the CNS, play multifaceted roles in supporting neuronal

function, maintaining the BBB, and regulating ion concentrations.

Importantly, recent research has highlighted the involvement of

astrocytes in neurotransmitter metabolism, immune response and

tissue repair, with their metabolic characteristics influencing the

progression and outcome of ischemic stroke. This understanding

underscores the potential of targeting astrocyte metabolic

reprogramming as a therapeutic strategy for ischemic stroke. By

summarizing the current knowledge on astrocyte metabolic

reprogramming mechanisms, regulatory factors and pathways, as well

as strategies to promote polarization balance, the present review

provides insights into the promising potential of astrocyte

immunometabolism-targeted therapies.

However, there is still a long way to go in the

study of metabolic reprogramming of astrocytes in ischemic stroke.

Given the intricate involvement of multiple molecular and signaling

pathways, the specific molecular mechanisms and regulatory networks

underlying astrocyte metabolic reprogramming in ischemic stroke

have yet to be fully elucidated. Therefore, future studies should

delve deeper into the precise molecular mechanisms of astrocyte

metabolic reprogramming, particularly its dynamic evolution across

different stages of ischemic stroke, the interplay and regulatory

relationships among various metabolic pathways, and the intricate

molecular mechanisms of its complex interactions with neurons. A

profound understanding of the molecular mechanisms and regulatory

networks of astrocyte metabolic reprogramming holds significant

clinical implications for developing novel therapeutic strategies

for ischemic stroke and identifying potential drug targets.

Currently, research on astrocytes in ischemic stroke primarily

focuses on cellular levels and animal models, and the applicability

and translatability of these findings in humans remain to be

validated. Future endeavors should concentrate on drug targets

capable of modulating astrocyte metabolic pathways and functional

states, emphasizing human-level exploration and validation. This

includes investigating astrocyte function and metabolic changes

using clinical samples, conducting relevant clinical trials, and

leveraging structural biology, medicinal chemistry and pharmacology

to design and optimize targeted therapies against these identified

targets. Ultimately, these efforts aim to assess the efficacy and

safety of astrocyte-targeted therapies.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

LW and TYM conceived and designed the study. WXC

wrote the first draft of the manuscript. RH, RM and YXX

participated in editing of specific paragraphs and figures. TYM

supervised the study and critically revised the manuscript. All

authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript. Data

authentication is not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant no. 8237142870).

References

|

1

|

Saini V, Guada L and Yavagal DR: Global

epidemiology of stroke and access to acute ischemic stroke

interventions. Neurology. 97(20 Suppl 2): S6–S16. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

GBD 2019 Stroke Collaborators: Global,

regional, and national burden of stroke and its risk factors,

1990-2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease

Study 2019. Lancet Neurol. 20:795–820. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Han RT, Kim RD, Molofsky AV and Liddelow

SA: Astrocyte-immune cell interactions in physiology and pathology.

Immunity. 54:211–224. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Chiellini G: Metabolic reprogramming in

health and disease. Int J Mol Sci. 21:27682020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Candelario-Jalil E, Dijkhuizen RM and

Magnus T: Neuroinflammation, stroke, blood-brain barrier

dysfunction, and imaging modalities. Stroke. 53:1473–1486. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Wu D, Chen Q, Chen X, Han F, Chen Z and

Wang Y: The blood-brain barrier: Structure, regulation, and drug

delivery. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 8:2172023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Verkhratsky A and Nedergaard M: Physiology

of astroglia. Physiol Rev. 98:239–389. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Lacoste B, Prat A, Freitas-Andrade M and

Gu C: The blood-brain barrier: Composition, properties, and roles

in brain health. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. a0414222024.Epub

ahead of print. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Vandebroek A and Yasui M: Regulation of

AQP4 in the central nervous system. Int J Mol Sci. 21:16032020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Hertz L and Chen Y: Importance of

astrocytes for potassium ion (K+) homeostasis in brain

and glial effects of K+ and its transporters on

learning. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 71:484–505. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Seifert G, Henneberger C and Steinhäuser

C: Diversity of astrocyte potassium channels: An update. Brain Res

Bull. 136:26–36. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Felix L, Delekate A, Petzold GC and Rose

CR: Sodium fluctuations in astroglia and their potential impact on

astrocyte function. Front Physiol. 11:8712020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Allen NJ and Eroglu C: Cell biology of

astrocyte-synapse interactions. Neuron. 96:697–708. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Oliveira JF and Araque A: Astrocyte

regulation of neural circuit activity and network states. Glia.

70:1455–1466. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Hara M, Kobayakawa K, Ohkawa Y, Kumamaru

H, Yokota K, Saito T, Kijima K, Yoshizaki S, Harimaya K, Nakashima

Y and Okada S: Interaction of reactive astrocytes with type I

collagen induces astrocytic scar formation through the

integrin-N-cadherin pathway after spinal cord injury. Nat Med.

23:818–828. 2017. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Wang C and Li L: The critical role of KLF4

in regulating the activation of A1/A2 reactive astrocytes following

ischemic stroke. J Neuroinflammation. 20:442023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Zamanian JL, Xu L, Foo LC, Nouri N, Zhou

L, Giffard RG and Barres BA: Genomic analysis of reactive

astrogliosis. J Neurosci. 32:6391–6410. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Liddelow SA, Guttenplan KA, Clarke LE,

Bennett FC, Bohlen CJ, Schirmer L, Bennett ML, Münch AE, Chung WS,

Peterson TC, et al: Neurotoxic reactive astrocytes are induced by

activated microglia. Nature. 541:481–487. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Patel MR and Weaver AM: Astrocyte-derived

small extracellular vesicles promote synapse formation via

fibulin-2-mediated TGF-β signaling. Cell Rep. 34:1088292021.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Anderson MA, Burda JE, Ren Y, Ao Y, O'Shea

TM, Kawaguchi R, Coppola G, Khakh BS, Deming TJ and Sofroniew MV:

Astrocyte scar formation aids central nervous system axon

regeneration. Nature. 532:195–200. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Lian H, Yang L, Cole A, Sun L, Chiang AC,

Fowler SW, Shim DJ, Rodriguez-Rivera J, Taglialatela G, Jankowsky

JL, et al: NFκB-activated astroglial release of complement C3

compromises neuronal morphology and function associated with

Alzheimer's disease. Neuron. 85:101–115. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Amalia L: Glial fibrillary acidic protein

(GFAP): Neuroinflammation biomarker in acute ischemic stroke. J

Inflamm Res. 14:7501–7506. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Liu G and Geng J: Glial fibrillary acidic

protein as a prognostic marker of acute ischemic stroke. Hum Exp

Toxicol. 37:1048–1053. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Song X, Gong Z and Liu K, Kou J, Liu B and

Liu K: Baicalin combats glutamate excitotoxicity via protecting

glutamine synthetase from ROS-induced 20S proteasomal degradation.

Redox Biol. 34:1015592020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Shi X, Luo L, Wang J, Shen H, Li Y,

Mamtilahun M, Liu C, Shi R, Lee JH, Tian H, et al: Stroke

subtype-dependent synapse elimination by reactive gliosis in mice.

Nat Commun. 12:69432021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Williamson MR, Fuertes CJA, Dunn AK, Drew

MR and Jones TA: Reactive astrocytes facilitate vascular repair and

remodeling after stroke. Cell Rep. 35:1090482021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Ma H, Zhou Y, Li Z, Zhu L, Li H, Zhang G,

Wang J, Gong H, Xu D, Hua W, et al: Single-cell RNA-sequencing

analyses revealed heterogeneity and dynamic changes of metabolic

pathways in astrocytes at the acute phase of ischemic stroke. Oxid

Med Cell Longev. 2022:18177212022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Denecke KM, McBain CA, Hermes BG, Teertam

SK, Farooqui M, Virumbrales-Muñoz M, Panackal J, Beebe DJ, Famakin

B and Ayuso JM: Microfluidic model to evaluate astrocyte activation

in penumbral region following ischemic stroke. Cells. 11:23562022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Lochhead JJ, Williams EI, Reddell ES, Dorn

E, Ronaldson PT and Davis TP: High resolution multiplex confocal

imaging of the neurovascular unit in health and experimental

ischemic stroke. Cells. 12:6452023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Zhou J, Zhang L, Peng J, Zhang X, Zhang F,

Wu Y, Huang A, Du F, Liao Y, He Y, et al: Astrocytic LRP1 enables

mitochondria transfer to neurons and mitigates brain ischemic

stroke by suppressing ARF1 lactylation. Cell Metab.

36:2054–2068.e14. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Scott EY, Safarian N, Casasbuenas DL,

Dryden M, Tockovska T, Ali S, Peng J, Daniele E, Nie Xin Lim I,

Bang KWA, et al: Integrating single-cell and spatially resolved

transcriptomic strategies to survey the astrocyte response to

stroke in male mice. Nat Commun. 15:15842024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Wang S, Pan Y, Zhang C, Zhao Y, Wang H, Ma

H, Sun J, Zhang S, Yao J, Xie D and Zhang Y: Transcriptome analysis

reveals dynamic microglial-induced A1 astrocyte reactivity via

C3/C3aR/NF-κB signaling after ischemic stroke. Mol Neurobiol.

61:10246–10270. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Bormann D, Knoflach M, Poreba E, Riedl CJ,

Testa G, Orset C, Levilly A, Cottereau A, Jauk P, Hametner S, et

al: Single-nucleus RNA sequencing reveals glial cell type-specific

responses to ischemic stroke in male rodents. Nat Commun.

15:62322024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Endo F, Kasai A, Soto JS, Yu X, Qu Z,

Hashimoto H, Gradinaru V, Kawaguchi R and Khakh BS: Molecular basis

of astrocyte diversity and morphology across the CNS in health and

disease. Science. 378:eadc90202022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Preman P, Alfonso-Triguero M, Alberdi E,

Verkhratsky A and Arranz AM: Astrocytes in Alzheimer's disease:

Pathological significance and molecular pathways. Cells.

10:5402021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Price BR, Johnson LA and Norris CM:

Reactive astrocytes: The nexus of pathological and clinical

hallmarks of Alzheimer's disease. Ageing Res Rev. 68:1013352021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Cai Z, Wan CQ and Liu Z: Astrocyte and

Alzheimer's disease. J Neurol. 264:2068–2074. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Kim J, Yoo ID, Lim J and Moon JS:

Pathological phenotypes of astrocytes in Alzheimer's disease. Exp

Mol Med. 56:95–99. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Booth HDE, Hirst WD and Wade-Martins R:

The role of astrocyte dysfunction in Parkinson's disease

pathogenesis. Trends Neurosci. 40:358–370. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Wang T, Sun Y and Dettmer U: Astrocytes in

Parkinson's disease: From role to possible intervention. Cells.

12:23362023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Cohen J and Torres C: Astrocyte

senescence: Evidence and significance. Aging Cell. 18:e129372019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Ponath G, Park C and Pitt D: The role of

astrocytes in multiple sclerosis. Front Immunol. 9:2172018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Yi W, Schlüter D and Wang X: Astrocytes in

multiple sclerosis and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis:

Star-shaped cells illuminating the darkness of CNS autoimmunity.

Brain Behav Immun. 80:10–24. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Aharoni R, Eilam R and Arnon R: Astrocytes

in multiple sclerosis-essential constituents with diverse

multifaceted functions. Int J Mol Sci. 22:59042021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Xu S, Lu J, Shao A, Zhang JH and Zhang J:

Glial cells: Role of the immune response in ischemic stroke. Front

Immunol. 11:2942020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Liu Z and Chopp M: Astrocytes, therapeutic

targets for neuroprotection and neurorestoration in ischemic

stroke. Prog Neurobiol. 144:103–120. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

47

|

Alsbrook DL, Di Napoli M, Bhatia K, Biller

J, Andalib S, Hinduja A, Rodrigues R, Rodriguez M, Sabbagh SY,

Selim M, et al: Neuroinflammation in acute ischemic and hemorrhagic

stroke. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 23:407–431. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Lu W, Chen Z and Wen J: Flavonoids and

ischemic stroke-induced neuroinflammation: Focus on the glial

cells. Biomed Pharmacother. 170:1158472024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Shen XY, Gao ZK, Han Y, Yuan M, Guo YS and

Bi X: Activation and role of astrocytes in ischemic stroke. Front

Cell Neurosci. 15:7559552021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Zhu G, Wang X, Chen L, Lenahan C, Fu Z,

Fang Y and Yu W: Crosstalk between the oxidative stress and glia

cells after stroke: From mechanism to therapies. Front Immunol.

13:8524162022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Chen Y, Qin C, Huang J, Tang X, Liu C,

Huang K, Xu J, Guo G, Tong A and Zhou L: The role of astrocytes in

oxidative stress of central nervous system: A mixed blessing. Cell

Prolif. 53:e127812020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Hertz L and Rothman DL: Glucose, lactate,

β-hydroxybutyrate, acetate, GABA, and succinate as substrates for

synthesis of glutamate and GABA in the glutamine-glutamate/GABA

cycle. Adv Neurobiol. 13:9–42. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Wang F, Xie X, Xing X and Sun X:

Excitatory synaptic transmission in ischemic stroke: A new outlet

for classical neuroprotective strategies. Int J Mol Sci.

23:93812022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Andersen JV, Markussen KH, Jakobsen E,

Schousboe A, Waagepetersen HS, Rosenberg PA and Aldana BI:

Glutamate metabolism and recycling at the excitatory synapse in

health and neurodegeneration. Neuropharmacology. 196:1087192021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Perea G, Navarrete M and Araque A:

Tripartite synapses: Astrocytes process and control synaptic

information. Trends Neurosci. 32:421–431. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Patabendige A, Singh A, Jenkins S, Sen J

and Chen R: Astrocyte activation in neurovascular damage and repair

following ischaemic stroke. Int J Mol Sci. 22:42802021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Yu X, Nagai J and Khakh BS: Improved tools

to study astrocytes. Nat Rev Neurosci. 21:121–138. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Mollinari C, Zhao J, Lupacchini L, Garaci

E, Merlo D and Pei G: Transdifferentiation: A new promise for

neurodegenerative diseases. Cell Death Dis. 9:8302018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Popa-Wagner A, Hermann D and Gresita A:

Genetic conversion of proliferative astroglia into neurons after

cerebral ischemia: A new therapeutic tool for the aged brain?

Geroscience. 41:363–368. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Jiang MQ, Yu SP, Wei ZZ, Zhong W, Cao W,

Gu X, Wu A, McCrary MR, Berglund K and Wei L: Conversion of

reactive astrocytes to induced neurons enhances neuronal repair and

functional recovery after ischemic stroke. Front Aging Neurosci.

13:6128562021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Zhang H, Zheng Q, Guo T, Zhang S, Zheng S,

Wang R, Deng Q, Yang G, Zhang S, Tang L, et al: Metabolic

reprogramming in astrocytes results in neuronal dysfunction in

intellectual disability. Mol Psychiatry. 29:1569–1582. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Perelroizen R, Philosof B, Budick-Harmelin

N, Chernobylsky T, Ron A, Katzir R, Shimon D, Tessler A, Adir O,

Gaoni-Yogev A, et al: Astrocyte immunometabolic regulation of the

tumour microenvironment drives glioblastoma pathogenicity. Brain.

145:3288–3307. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Giaume C, Naus CC, Sáez JC and Leybaert L:

Glial connexins and pannexins in the healthy and diseased brain.

Physiol Rev. 101:93–145. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Zhang YM, Qi YB, Gao YN, Chen WG, Zhou T,

Zang Y and Li J: Astrocyte metabolism and signaling pathways in the

CNS. Front Neurosci. 17:12174512023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Falkowska A, Gutowska I, Goschorska M,