MicroRNAs (miRNAs/miRs) are short non-coding RNAs,

which serve a role in cell differentiation, homeostasis and

organism development. miRNAs consist of ~22 nucleotides, and can

induce silencing of some genes by directing argonaute (AGO)

proteins to target mRNA at the 3′ untranslated region (UTR)

(1,2). As single-stranded short nucleic

acids, miRNAs act as guides to RNA or DNA complementary sequences

that are intended to be silenced (3). The translational repression and

further elimination of target mRNAs occur through the miRNA-induced

silencing complex (miRISC), which is formed of the miRNA, AGO

proteins and other associated proteins such as Dicer (2).

At present, it has been reported that most of the

human protein-coding genes (>60%) contain miRNA target sites

(4), and the miRNA repository

miRBase (https://www.mirbase.org) records 2,654

mature miRNAs and 1,917 precursor miRNAs (pre-miRNAs) in humans

(5).

As a hallmark of cancer and other common diseases,

the upregulated and downregulated expression of miRNAs serves a

crucial role in disease development and progression. The

upregulation of miRNAs associated with cancer promotes cancer by

targeting tumor suppressor genes (6). For example, miR-21 is often

upregulated in various cancer types, including breast, lung and

colorectal cancer (CRC). miR-21 upregulation leads to the

suppression of tumor suppressor genes such as PTEN and programmed

cell death protein 4, promoting cell proliferation and survival

(7). In a similar manner,

miR-155 is frequently upregulated in hematological malignancies,

including lymphoma and leukemias. This miRNA targets multiple genes

involved in apoptosis and cell differentiation, contributing to

tumorigenesis (8).

The upregulation of miRNAs such as tumor suppressor

miRNAs inhibits cancer via targeting of oncogenes. For instance,

miR-34a is downregulated in numerous cancer types, including

pancreatic and prostate cancer. miR-34a downregulation leads to the

upregulation of oncogenes such as MYC and BCL2, facilitating tumor

growth and resistance to apoptosis (8). Similarly, the miR-200 family of

miRNAs is often downregulated in cancer types such as ovarian and

breast cancer. The loss of miR-200 expression is associated with

epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), a process that enhances

cancer cell invasion and metastasis (9).

Cancer mortality is a threat to health worldwide.

Approaches for early detection of cancer using different diagnostic

procedures and cancer treatments are needed globally. A

cancer-specific screening technique that is sensitive enough to

identify early malignancy would be ideal. This should be specific

to the cancer type and location, appropriate for the size of the

tumor, affordable, user-friendly, and safe. Currently, there are

numerous methods for identifying and measuring certain miRNAs,

including miRNA arrays, in situ hybridization and

immuneprecipitation to examine miRNA localization and specific

miRNA activity, and total miRNA measurement (10). The accuracy, cost, effectiveness

and ease of tracking miRNA dynamics vary among these methods.

Furthermore, all of these approaches have some advantages and

disadvantages for miRNA quantification in biochemical and medical

research (11,12).

The CRISPR/CRISPR-associated sequence (Cas) system

is a programmable platform, a modern world genome editing system,

which has garnered trust for the management of cancer detection and

treatment (13,14). The innovative approach of cancer

detection using the CRISPR/Cas system is more cost effective

compared with other currently known procedures (15). CRISPR/Cas systems are now a

frequently used genome editing method in molecular biology labs

worldwide because of their quick cycle, low cost, high efficiency,

good repeatability and simple design (16,17). This system consists of a set of

CRISPR-associated (Cas) genes that encode Cas proteins with

endonuclease activity as well as CRISPR repeat-spacer arrays, which

can be further translated into CRISPR RNA (crRNA) and

trans-activating crRNA (18,19).

CRISPR/CRISPR-associated sequence 13 (Cas13) is a

powerful and versatile genome-editing tool, targeting and cleaving

single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) rather than DNA, and is a class 2 type

VI CRISPR/Cas system (20).

Cas13 belongs to the class 2 type VI CRISPR/Cas system and consists

of different subtypes, including Cas13a, Cas13b, Cas13c and Cas13d.

Among all these subtypes, Cas13a (also referred to as C2c2) is the

most studied in terms of its structure and RNA editing approach

(21). The CRISPR/Cas13 system

can be effectively used for viral detection, splicing regulation,

transcript tagging and RNA knockdown (22-24).

The advancements in miRNA detection with the help of

the CRISPR/Cas13 system have shown some promising results. Some of

the key updates include direct and accurate miRNA detection,

development of amplification-free biosensors and lateral flow

assays (25-27). However, several knowledge gaps

remain, which need to be discussed further. The current methods of

miRNA detection show high sensitivity; however, the achievement of

absolute specificity in complex biological samples remains a

challenging task (11). Further

research is required to minimize false positives and improve the

robustness of these assays. The development of cost-effective and

scalable miRNA detection procedures, which are suitable for

widespread clinical use, is still a hurdle. Thus, innovations that

reduce the costs and simplify the detection processes are crucial.

Furthermore, there is still much to learn regarding the diverse

roles of miRNAs in various diseases, particularly cancer.

Therefore, comprehensive studies are needed to fully understand

their mechanisms and potential as therapeutic targets.

In the present review, current updates regarding the

biogenesis, structural and functional aspects, and dysregulation in

different cancer types of miRNAs are discussed. In addition, the

significance of altered miRNA expression in tumors is discussed.

Furthermore, the functional aspects of CRISPR/Cas13 as a

next-generation tool in different forms for the detection of miRNAs

in different cancer types are elaborated. An overview of current

methods using CRISPR/Cas13-based biosensor systems is provided,

emphasizing how these methods have made it possible to miniaturize

electrochemical transducers and enhance their sensitivity,

specificity and suitability for miRNA diagnosis. Furthermore,

challenges and prospects of the use of CRISPR/Cas13 as a miRNA

detection tool are discussed.

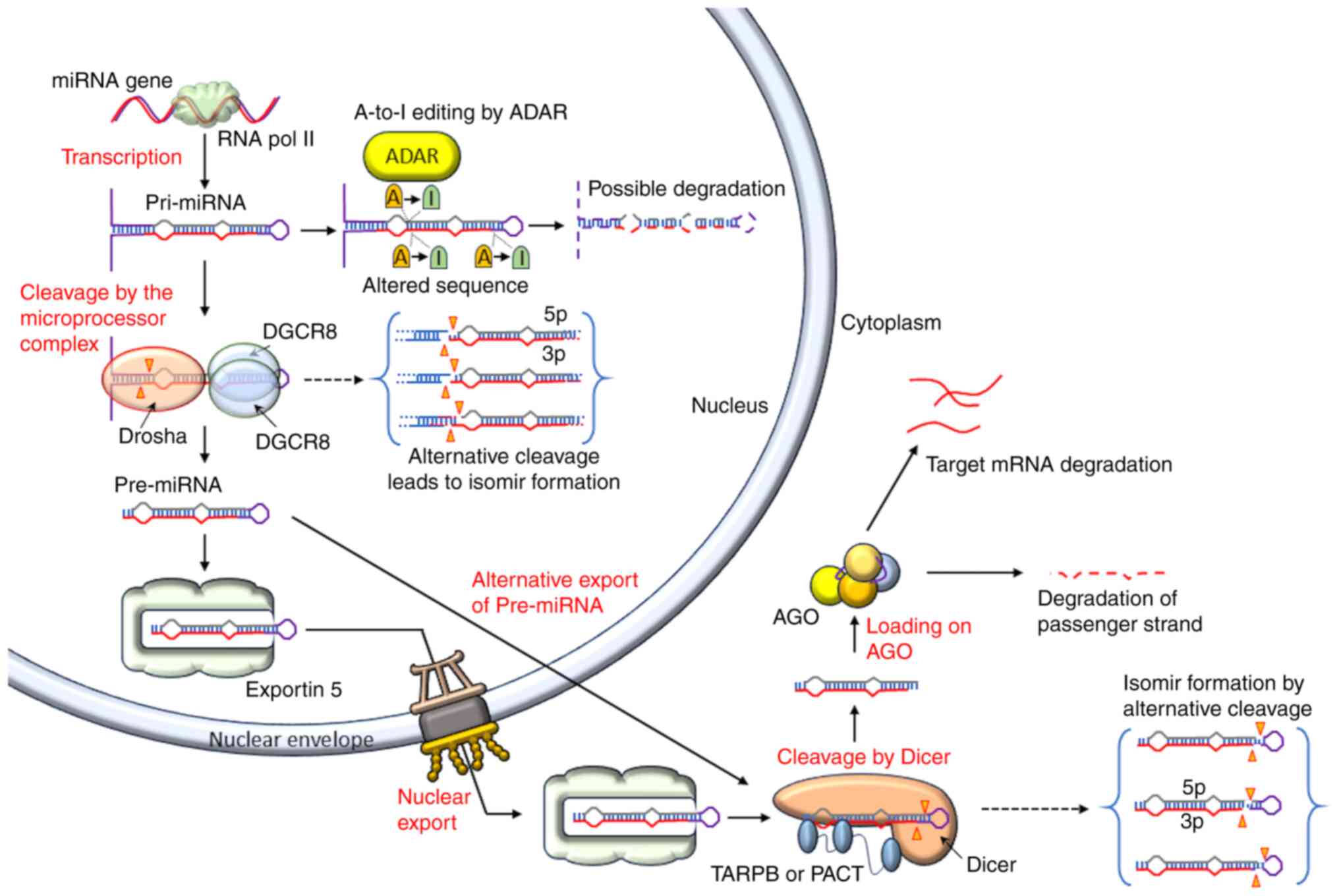

miRNA biogenesis is a multi-step process that occurs

under tight temporal and spatial control by different proteins. The

RNA polymerase II primarily transcribes them as primary miRNAs

(pri-miRNAs), which are then converted into pre-miRNAs, which are

later converted into mature miRNA duplexes (28,29) (Fig. 1). The 5p and 3p strands of the

mature miRNA are derived from the 5′ arm of the pre-miRNA. The

A-to-I editing of pri-miRNAs is performed by adenosine deaminase

proteins, which may impact subsequent biogenesis and the sequence

of the mature miRNA, or mediates pri-miRNA destruction (30).

The microprocessor complex, which includes the

DiGeorge syndrome critical region 8 (DGCR8) protein (31,32) and the RNase III enzyme Drosha

(33), excises the pri-miRNA

hairpin in the nucleus (Fig. 1).

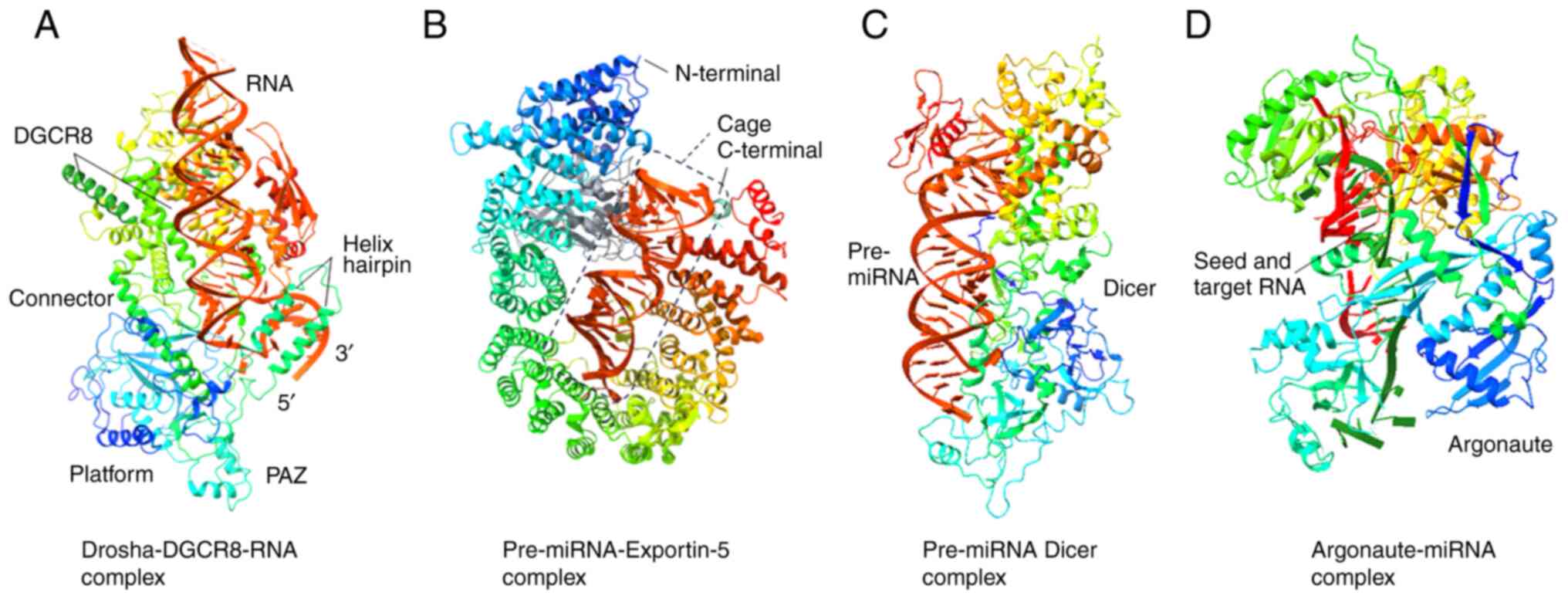

For its action, two DGCR8 proteins bind the stem and make a proper

cleavage (34,35), while Drosha detects the junction

between double-stranded RNA and ssRNA at the pri-miRNA hairpin base

[Fig. 2A; obtained from Protein

Data Bank (PDB; https://www.rcsb.org) with PDB ID

6LXD and modified with Chimera X (https://www.cgl.ucsf.edu/chimerax/; version 1.8)]. The

alternative cleavage by Drosha results in the creation of isomirs

(36,37). Pre-miRNAs are hairpin-shaped RNAs

composed of ~70 nucleotides (38,39). The hairpin end has a 3′ hydroxyl,

a 5′ phosphate and a 2-nucleotide overhang at the 3′ end (40).

After identifying the overhang, exportin-5 (XPO-5; a

transport protein) transports the pre-miRNA into the cytoplasm

(41) (Figs. 1 and 2B). In a human cell line, exportin-5

(XPO-5) deletion led to decreased transportation of pre-miRNA but

did not completely stop its nuclear export, indicating the

existence of some other pre-miRNA nuclear export pathways (42). In the cytoplasm, Dicer (RNase III

enzyme) (43,44) recognizes the 5′ phosphate, 3′

overhang and loop structure (45,46), and binds the pre-miRNA (Fig. 1). Dicer acts as a 'molecular

ruler' that produces a mature miRNA duplex with a 2-nucleotide 3′

overhang (40) after cleaving

pre-miRNAs at a species-specific length (Fig. 2C). It is also possible for Dicer

to produce isomirs through alternative cleavage (37).

In vertebrates, Dicer cleavage is regulated by

protein activator of the interferon-induced protein kinase and

transactivating response-RNA-binding protein. The cleavage of

pre-miRNA by Dicer leads to the formation of two RNA strands (guide

and passenger strands). The mature miRNA 'guide' strand is loaded

into AGO protein, while the 'passenger' strand is eliminated

(47,48) (Fig. 1). The strand with the less

securely coupled 5′ end (49) is

preferentially loaded on the AGO protein (Fig. 2D).

After being transcribed into pri-miRNA transcripts,

miRNAs go through a multi-step biogenesis process that transforms

them into pre-miRNAs and mature miRNAs. The expression patterns of

miRNAs are tissue-specific (50)

and transcriptionally regulated (51). miRNAs can originate from long

non-coding RNAs or introns, and are mostly transcribed by RNA

polymerase II (52,53). Pri-miRNAs can be clusters of

frequently linked miRNAs or a single mature miRNA (54). Based on how similar their seed

sequences are, miRNAs are categorized into different families

(55). The seed region of

miRNAs, which consists of nucleotides 2-8 (counting from the 5′

end), is mostly responsible for targeting mRNAs (56).

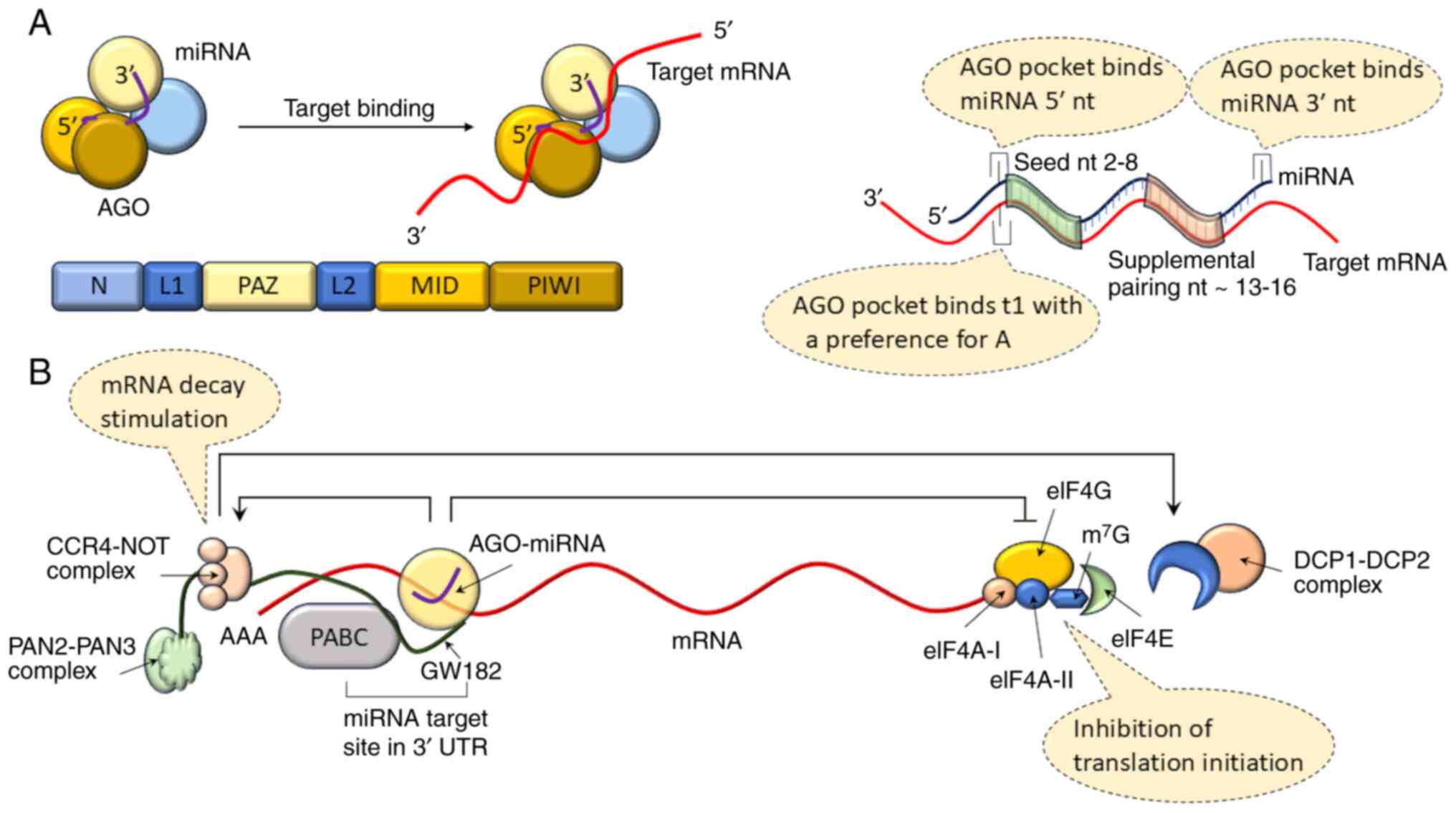

Mature miRNAs act inside a single polypeptide chain

AGO protein, with four distinctive domains (Fig. 3A). The four domains are the

N-terminal (N), P-element induced wimpy testes (PIWI)-AGO-Zwille

(PAZ), PIWI and MID domains. A linker domain (L1) is present

between the N and PAZ domains, while the L2 domain is present

between the PAZ and MID domains. The MID and PIWI domains make up

the second lobe of AGO, while the N and PAZ domains make up the

first (57,58). The PAZ domain binds the 3′

nucleotides of the miRNA (59,60), whereas the MID and PIWI domains

retain the 5′ end of the miRNA (Fig.

3A). It has been reported that four AGO proteins (AGO1-4) are

encoded by the mammalian genome. AGO2 is the most abundant and

unique among the AGO proteins, with target cleaving activity when

completely complementary to the guide strand of the miRNA (61,62). Numerous human miRNAs bind to all

AGO proteins, although some are selectively packaged into AGO

proteins (63,64). Typically found in the 3′ UTR of

mRNAs, miRNA target sites exhibit high complementarity to the seed

region, the primary requirement for the prediction of target sites

(65,66).

The strongest canonical (seed matching) target sites

are those that complement miRNA nucleotides 2-8 and have an adenine

opposite miRNA nucleotide 1 (referred to as 't1A'), followed by

those complementing nucleotides 2-8 without a t1A and those

complementing nucleotides 2-7 with t1A (67). A binding site in AGO (68,69) recognizes t1A instead of the miRNA

guide strand (Fig. 3A). Target

sites that complement miRNA nucleotides 2-7 or 3-8 are still

considered canonical, although they have a weaker affinity

(65). According to structural

and single-molecule investigations, the MID and PIWI domains

pre-organize the initial nucleotides 2-6 of the seed in helical

conformation (59,70). This two-step mechanism is

considered to be responsible for target identification (71).

The biological role of non-canonical sites has been

contested because small RNA and miRNA transfection data showed no

discernible suppression from these locations (65). Through translational suppression

and mRNA decay, the 3′ UTR binding with AGO-miRNA results in gene

silencing (72) (Fig. 3B). Furthermore,

glycine-tryptophan 182 (GW182; 182 kDa), a member of the

glycine-tryptophan protein family, is recruited by AGO for RNA

silencing (73).

By attracting the poly(A)-nuclease deadenylation

complex subunit 2 (PAN2)-PAN3 and carbon catabolite repressor

protein 4 (CCR4)-NOT complexes (74,75), the interaction between

polyadenylate binding protein and GW182 promotes the deadenylation

of mRNA. Because deadenylation encourages decapping by the

mRNA-decapping enzyme subunit 1 (DCP1)-DCP2 complex (76), 5′-3′ exoribonuclease 1 can

quickly degrade the mRNA (77)

(Fig. 3B). Through the

recruitment of the likely ATP-dependent RNA helicase DEAD-box

helicase 6, GW182-mediated recruitment of CCR4-NOT also results in

translation suppression (78).

Eukaryotic initiation factor 4A-I (eIF4A-I) and

eIF4A-II interference also inhibits translation initiation

(79,80). Although the exact method of

interference in initiation factors is not fully understood yet,

most studies suggest that miRISC causes them to separate from

target mRNAs (81,82), which prevents scanning by the

ribosome and the formation of the eIF4F translation initiation

unit. Translation inhibition requires the Trp-binding pockets in

AGO that mediate binding with GW182, according to a study conducted

in human and Drosophila melanogaster cells (83,84).

Complete understanding of miRISC-mediated

translation inhibition remains lacking, and it has been

hypothesized that the two methods of miRISC-mediated gene silencing

are related (2). Ribosome

profiling tests have shown that mRNA degradation typically accounts

for 66-90% of silencing (72,85). The observation that translation

inhibition can be restored while mRNA degradation is permanent

raises the possibility that regulated pauses, or blocks, in the

metabolic cascade leading to mRNA degradation could allow

translation suppression without mRNA decay (86). Furthermore, multiple miRNAs can

regulate the same gene (87),

and it has also been reported that hundreds of genes can be muted

by a single miRNA (88).

Furthermore, individual miRNAs or miRNA clusters can

control whole cellular pathways (89). Cooperative suppression can be

caused by nearby target site binding with miRNA on a target mRNA

(90,91), which may help justify the

functioning of non-canonical sites relying on the occupancy of

nearby canonical sites. The development of multivalent protein

interactions between GW182 and AGO proteins help to explain

cooperativity (84).

Furthermore, miRNAs can either inhibit or regulate protein

expression (92), protecting

against variations (or 'noise') in gene expression levels (93).

Human cancers exhibit dysregulated miRNA expression.

Cancer development through chromosome abnormalities,

transcriptional regulation alterations, epigenetic modifications

and flaws in the miRNA biogenesis machinery are some of the

underlying mechanisms (94,95). miRNA expression is regulated at

different stages of cellular activities as subsequently

described.

Changes in genomic miRNA copy numbers and gene

positions (amplification, deletion or translocation) are frequently

related to the cause of abnormal miRNA expression in malignant

cells (96). The loss of the

miR-15a/16-1 cluster gene at chromosome 13q14, which is commonly

seen in individuals with B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia, is

the earliest example of a change in miRNA gene placement (97). In addition, the 5q33 region that

contains miR-143 and miR-145 is frequently deleted in lung cancer,

which lowers the expression levels of both miRNAs (96). On the other hand, B-cell lymphoma

(98) and lung cancer (99) exhibit amplification of the

miR-17-92 cluster gene, and T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia

(100) exhibits translocation

of this cluster gene, resulting in upregulation of these miRNAs in

these cancer types.

High-resolution array-based comparative genomic

hybridization has been used to confirm the high frequency of

genomic changes in miRNA loci in 227 human cancer samples of

ovarian cancer, breast cancer and melanoma (101). Numerous miRNA genes are found

in genomic areas linked to cancer, according to additional

genome-wide studies (102,103). These areas on chromosomes may

be fragile sites, common breakpoint regions or minimal regions of

amplification, which may include oncogenes, or minimal regions of

loss of heterozygosity, which may carry tumor suppressor genes

(102). Considering all the

observations, the findings suggest that the amplification or

deletion of specific genomic regions containing miRNA genes may be

the cause of abnormal miRNA expression in malignant cells.

Since a number of transcription factors tightly

regulate miRNA production, dysregulation of some important

transcription factors, including p53 and c-Myc, may be linked to

aberrant miRNA expression in cancer (104,105). By binding to E-box regions in

the miR-17-92 promoter, c-Myc is commonly increased through

transcriptional activation, in a number of malignancies to control

cell proliferation and death, and promotes the transcription of the

oncogenic miR-17-92 cluster (106). In keeping with its carcinogenic

function, c-Myc also inhibits the transcriptional activity of

tumor-suppressive miRNAs, including the let-7, miR-26, miR-29 and

mir-15a families (107).

In hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), c-Myc and the

tumor suppressor miR-122 are reciprocally regulated. By attaching

itself to its promoter, c-Myc inhibits the synthesis of miR-122

and, by targeting the transcription factor Dp2 and the

transcription factor E2F transcription factor 1 (E2f1), indirectly

stops c-Myc transcription. Therefore, the disruption of this

feedback loop between miR-122 and c-Myc is necessary for the

development of HCC (108). HCC

is brought on by direct binding of c-Myc to the promoters of the

miR-148a-5p and miR-363-3p genes, which inhibits their synthesis

and encourages the G1 to S phase transition.

miR-148a-5p, on the other hand, directly targets and suppresses the

production of c-Myc, while miR-363-3p destabilizes c-Myc by

targeting ubiquitin-specific protease (106,109). One of the most frequently

altered genes in human cancer is TP53, which encodes the tumor

suppressor p53. Another manner in which transcriptional factors

control miRNA expression to exert a tumor suppressive function is

the p53-miR-34 regulatory axis (110). A complex p53 network that

controls cell-cycle progression and apoptosis is formed by the

p53-regulated expression of several genes, including miRNA genes.

Similar to p53-mediated phenotypes, the miR-34 family, comprising

miR-34a, miR-34b and miR-34c, causes cell-cycle arrest, cell

senescence and apoptosis in cancer (111), suggesting that p53 and miR-34

are involved in the same regulatory mechanism.

Additional research has revealed that p53 regulates

the expression of several miRNAs, including miR-605 (112), miR-1246 (113) and miR-107 (114), to carry out its role.

Additional transcriptional factors have been identified to control

miRNA production in addition to the two most well researched

transcriptional factors, c-Myc and p53. For instance, miR-223 is

inhibited in a variety of cancer types, including HCC and acute

myeloid leukemia (AML), and it is predominantly expressed in the

hematopoietic system, which serves important roles in the formation

of myeloid lineages (115).

As aforementioned, several enzymes and regulatory

proteins, including Drosha, Dicer, DGCR8, AGO and XPO-5,

intricately regulate miRNA biogenesis, enabling proper maturation

of miRNA from pri-miRNA precursors. Therefore, aberrant expression

of miRNAs may result from mutations or aberrant expression of any

protein in the miRNA biogenesis pathway. Two important RNase III

endonucleases in miRNA maturation, Drosha and Dicer, oversee the

creation of pre-miRNA and the miRNA duplex (116,117). According to previous studies,

both enzymes are dysregulated in some cancer types such as breast

and bladder cancer (118,119).

A portion of miRNAs are controlled during the

Drosha-processing stage, and this control affects miRNA expression

in cancer and during embryonic development (120). It has been reported that 15% of

534 Wilms tumors had single-nucleotide substitution/deletion

mutations in DGCR8 and Drosha, which resulted in reduced expression

of mature Let-7a and the miR-200 family (121). In terms of Dicer dysregulation,

it has been noted that CRC cells with impaired Dicer acquire a

higher propensity for tumor initiation and metastasis (122). Furthermore, patients with

ovarian cancer with higher Dicer and Drosha mRNA levels have a

higher median survival rate (123). On the other hand, patients with

lower Dicer expression have a considerably lower survival rate

(124,125).

Reduced let-7 expression and poor postoperative

survival have been linked to lower Dicer mRNA levels in patients

with lung cancer (126). As

with Dicer and Drosha, cancer also leads to deregulation of AGO.

For instance, kidney tumors caused by Wilms disease frequently

exhibit loss of the human eukaryotic initiation factor 2C1/human

argonaute gene (127). Human

AGO proteins are crucial in regulating cell-dependent gene

expression. AGO2 expression levels, for example, are considerably

higher in basic gastric cancer and the lymph node metastases

(128), but AGO2 expression is

lower in melanoma, which corresponds to a lower RNA interference

efficiency, compared with in primary melanocytes (129).

A fraction of human cancers with microsatellite

instability have inactivating mutations in the XPO-5 gene. The

insertion of an 'A' in exon 32 in CRC cells (HCT-15 and DLD-1

cells), results in an early termination codon, which causes a

frameshift mutation and the creation of a shortened protein. This

shortened XPO-5 is no longer able to export pre-miRNAs. As a

result, there is less miRNA processing since pre-miRNAs are

confined to the nucleus. The restoration of XPO-5 activities

possesses tumor-suppressor properties and restores the defective

export of pre-miRNAs (130). It

has also been noted that ERK phosphorylates XPO-5, preventing XPO-5

from moving pre-miRNAs from the nucleus to the cytoplasm in HCC

(131).

A well-known characteristic of cancer is epigenetic

modification, which includes the disruption of histone

modification, aberrant DNA hypermethylation of tumor suppressor

genes and widespread genomic DNA hypomethylation. Similar to

protein coding genes, miRNAs are considered to be subjected to

epigenetic modifications (132,133). For example, it has been

reported that acute myeloid leukemia 1/eight twenty one, the most

prevalent AML-associated fusion protein, epigenetically suppresses

miR-223 expression via CpG methylation (134). A study reported that the

expression levels of 17 out of 313 human miRNAs were more than

three times higher in T24 bladder cancer cells after concomitant

treatment with DNA methylation and histone acetylation inhibitors

(134).

The downregulation of the proto-oncogene BCL6

coincides with markedly increased expression of miR-127, which is

embedded in a CpG island and not expressed in cancer cells

(135). These findings suggest

that miRNAs may function as tumor suppressors and can be activated

through DNA demethylation and histone deacetylase inhibition. In

addition, it has been reported that miR-148a and the miR-34b/c

cluster are susceptible to hypermethylation-associated silencing in

cancer cells (136).

Furthermore, in vivo metastasis formation was suppressed,

tumor growth was decreased and cancer cell motility was inhibited

when these miRNAs were restored (137). Similarly, DNA hypermethylation

has been linked to lower expression levels of miR-9-1, miR-124a and

miR-145-5p in colon, lung and breast cancer, respectively (138,139). This suggests that the abnormal

histone acetylation and DNA methylation of miRNA genes could be

useful indicators for the diagnosis and prognosis of cancer. These

findings emphasize the significance of epigenetic control in miRNA

production during carcinogenesis.

The biological characteristics of tumor development

include continued proliferative signaling, evasion of growth

suppressors, replicative immortality, initiation of invasion and

metastasis, induction of angiogenesis, and prevention of cell death

(140). Dysregulated miRNAs may

impact one or more of these cancer hallmarks for tumor initiation

and development. In different situations, miRNAs act as tumor

suppressors or oncogenes, depending on the genes they target.

Dysregulated miRNAs affect tumorigenesis in different manners as

described subsequently.

The primary cause of tumorigenesis is aberrant cell

proliferation, which is the most significant characteristic of

cancer. Certain miRNAs functionally incorporate into several cell

proliferation pathways, and the dysregulation of these miRNAs

directs the cancer cells to continue proliferative signaling to

avoid growth suppressors. miRNAs serve a role in controlling the

expression of E2F proteins (cell proliferation regulators).

E2F1-deficient animals develop a wide range of malignancies, and

this member of the E2F family is characterized as a tumor

suppressor and stimulates target gene transcription during the

G1 to S transition (141). miR-17-92, once activated by

c-Myc, suppresses the translation of E2F1 (106). E2F1 protein levels may not

increase markedly in response to c-Myc activation if the miR-17-92

cluster acts as a brake on this putative positive feedback loop,

given that c-Myc also directly stimulates E2F1 production (142). Furthermore, the miR-17-92

cluster has been demonstrated to regulate E2F2 and E2F3 translation

(143). Additionally, the

expression of the miR-17-92 cluster might be triggered by the E2F

transcription factors (144).

Therefore, under normal conditions, the feedback loop between E2F

and the miR-17-92 cluster provides a means of preserving regular

cell-cycle progression. However, miR-17-92 upregulation, which is

common in several cancer types such as colorectal cancer and

gastric cancer, disrupts the feedback loop that encourages cell

proliferation (145).

Different cyclins, Cdks and their inhibitors,

extensively regulated by miRNAs, are essential for cell-cycle

progression. The G1/S transition inhibition of

Drosophila germline stem cells with Dicer-1 deletion suggests that

miRNAs are required for germline stem cells to pass through the

normal G1/S checkpoint (146). Additionally, Dacapo, a member

of the p21/p27 family of Cdk inhibitors, is upregulated in

Dicer-deficient germline stem cells, suggesting that miRNAs

negatively control this protein to encourage cell-cycle progression

(147). In glioblastoma cells,

miR-221/222 has been found to directly target the Cdk inhibitor

p27Kip1 (148), a finding that

has been subsequently validated in original tumor samples and other

cancer cell lines (149,150).

While its inhibition causes G1 cell-cycle arrest in

malignant cells, ectopic expression of miR-221/222 enhances cell

proliferation. Furthermore, several human malignancies have been

reported to be associated with increased expression levels of

miR-221/222, suggesting that regulation of p27Kip1 by miR-221/222

is a valid carcinogenic pathway (151).

To meet the demands of food and oxygen during tumor

growth and metastasis, the highly coordinated process of

angiogenesis produces new blood vessels from pre-existing ones

(152). Because the oxygen

concentration of tumor tissues is lower than that of the

surrounding normal tissues, hypoxia serves a critical role in the

tumor microenvironment by facilitating the proliferation and

maintenance of cancer cells. In response to hypoxia, a crucial

transcription factor, hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF), affects the

expression of several genes, including miRNAs (153). As a key angiogenic factor, VEGF

instructs endothelial cells to form new vessels when it binds to

its receptors (154).

Therefore, angiogenesis is likely to be impacted by miRNAs that

target the VEGF or HIF signaling pathways.

Hypoxia causes endothelial cells to produce miR-424,

which targets cullin 2, a ubiquitin ligase scaffold protein, to

stimulate angiogenesis. By stabilizing HIF-1α, this step enables

stabilized HIF-1α to transcriptionally trigger the expression of

VEGF (160). miR-21 is another

miRNA that promotes angiogenesis. To activate the downstream

Akt/ERK signaling pathways and increase HIF-1α and VEGF expression,

it targets PTEN (161). By

inhibiting VEGF and/or HIF-1α, on the other hand, miR-20b and

miR-519c negatively control angiogenesis (162,163). The downregulation of miR-107

increases tumor angiogenesis under hypoxic conditions because it

not only regulates HIF-1α but also inhibits the production of

HIF-1β (114).

The biology of metastasis is an intricate,

multi-step and dynamic process. The loss of cell adhesion due to

E-cadherin suppression and the activation of genes linked to

invasion and motility are the hallmarks of the EMT, which is

regarded as an initial and crucial stage of metastasis (164). Numerous miRNAs alter the

expression of genes, including MMPs and their inhibitors, that

control extracellular matrix (ECM) turnover and breakdown (165). Proliferation, migration,

differentiation and apoptosis are among the cell phenotypic

alterations that are influenced by ECM turnover or remodeling

(166). Zinc-dependent

endopeptidases, known as important MMPs such as MMP-1, -2, -3, -7

and -9, are crucial for cell migration, adhesion, dispersion,

differentiation and ECM modeling (167). They can cause cell surface

receptors to cleave ECM proteins such as type IV collagen,

interestitial collagen, elastin and casein for degradation

(168). Exogenous miR-143

expression in osteosarcoma cells leads to downregulated MMP-13

protein levels and reduced cell invasion (169). In clinical samples, MMP-13 was

found in cases with lung metastases and low miR-143 expression,

while it was not found in patients without metastases and with high

miR-143 expression (170).

It has been revealed that miR-206 decreased the

amount of the cell division cycle 42, MMP-2 and MMP-9 proteins in

human breast cancer (171). Due

to the control of actin cytoskeleton remodeling, including

filopodia formation, this protein level regulation inhibited

MDA-MB-231 cell invasion and migration (171). Furthermore, downregulation of

miR-340 has been associated with aggressive activity in several

breast cancer cell lines (172). Because it directly targets

c-Met, the stimulation of miR-340 expression suppresses the

motility and invasion of breast tumor cells, thereby modulating the

production of MMP-2 and MMP-9 (172).

Numerous signaling pathways, including the TGF-β

pathway, are considered to govern EMT. These pathways converge on

important transcription factors, including Zinc finger

E-box-binding homeobox (ZEB), SNAIL and TWIST (173). TGF-β-regulated miRNAs

participate in TGF-β signaling to trigger EMT and promote

metastasis in advanced cancer. miR-155 is implicated in this

regulation, is transcriptionally activated by TGF-β/SMAD4 signaling

and is upregulated in several malignancies such as colorectal and

breast cancer (174).

Furthermore, miR-155 stimulates EMT by targeting RhoA GTPase, an

essential modulator of cellular polarity and the formation and

maintenance of tight junctions. Additionally, miR-155 suppression

prevents TGF-β-induced EMT, tight junction disruption, cell

migration and invasion (174).

In contrast to miR-155, TGF-β inhibits miR-200 and miR-203, and it

has been demonstrated that the miR-200 family influences EMT by

suppressing the expression of the transcriptional repressors (ZEB1

and ZEB2) of E-cadherin (175).

ZEB1 and ZEB2, in turn, also suppress the miR-200 transcript,

creating a double-negative feedback loop between the miR-200 family

and ZEB1/ZEB2 (176).

An important characteristic of tumor growth is

evasion of apoptosis, which is considered to be controlled by

miRNAs (177,178). Different strategies are

developed by tumor cells to prevent or delay apoptosis. The most

prevalent of these is the loss of p53 tumor suppressor activity

(179). Other strategies to

avoid apoptosis include the suppression of proapoptotic proteins,

upregulation of anti-apoptotic regulators and blocking the death

pathways (180). miRNAs either

inhibit or activate the components involved in anti-apoptosis

mechanisms. It has been demonstrated that numerous p53-regulated

miRNAs contribute to p53 functions; some of these miRNAs can

feedback-modify p53 activity (181). For example, in multiple

myeloma, p53 transcriptionally activates three miRNAs (miR-192,

miR-194 and miR-215) to bind directly with the mRNA of mouse double

minute 2 homolog (Mdm2) and prevent p53 from being destroyed, thus

inhibiting Mdm2 expression (182). The development of multiple

myeloma is influenced by the downregulation of these miRNAs, which

are positive regulators of p53 (183).

Another negative feedback regulation takes place

between p53 and miR-122 by targeting cyclin G1 (184) and cytoplasmic polyadenylation

element-binding protein (185).

The creation of a chemotherapy and miRNA-based therapeutic

combination for HCC is made possible by the stimulation of p53

activity by miR-122, which also increases cell sensitivity to

doxorubicin (186). In

addition, cancer cells are resistant to death due to other

dysregulated p53-regulated miRNAs. For example, the miR-17-92

cluster represents a novel target for p53-mediated transcriptional

repression during hypoxia. While its upregulation prevents

apoptosis, its downregulation makes cells more vulnerable to

hypoxia-induced apoptosis. Consequently, tumor cells that express

more miR-17-92 may be able to evade the apoptosis caused by hypoxia

(187). All these

aforementioned findings demonstrate that, in healthy circumstances,

p53 and miRNAs regulate a network that intricately determines cell

destiny. However, dysregulation of p53 or its target miRNAs may

allow cancer cells to evade cell death.

Some miRNAs that serve a role in cell death may

target proapoptotic factors (Bax, Bim and Puma) and anti-apoptotic

regulators (Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL). In chronic lymphocytic leukemia,

miR-15a and miR-16-1 are downregulated, and their expression is

inversely associated with that of Bcl-2 (97). Additional research revealed that

these two miRNAs caused apoptosis and suppressed Bcl-2 expression

(188). Other miRNAs, including

miR-204 (189), miR-148a

(113) and miR-365 (190), also control Bcl-2 expression.

miR-491-5p effectively causes ovarian cancer cells to undergo

apoptosis by causing Bim accumulation and directly suppressing

Bcl-xL expression (191).

The role of some miRNAs and their relationship with

tumor occurrence, development, metastasis and survival is shown in

Table I.

Different approaches are currently available for

the identification and quantification of miRNAs, which have the

capacity to measure either total miRNAs or specific miRNAs, and

their localization within cells. For the quantification of total

miRNA, these methods have been devised based on hybridization,

amplification, sequencing and enzyme-based approaches (10). The hybridization-based methods

include northern blotting, microarrays and bead array-based

profiling. The amplification-based methods of miRNA quantification

include reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR), rolling

circle amplification (RCA) and next-generation sequencing. The

enzyme-based methods of miRNA detection include invader assays,

luciferase-based assays, assay using miRNA in vivo activity

reporters and the molecular beacon imaging method. All these

detection and quantification assays vary in efficiency, cost,

accuracy and monitoring convenience (10). The currently used miRNA detection

approaches using different detections tools, and their strengths

and limitations are summarized in Table II.

CRISPR/Cas systems have been widely used for

biotechnological and clinical research following the identification

of RNA-programmable nucleases from the prokaryotic adaptive immune

system (192,193). Among different types of

CRISPR/Cas systems, the type VI system exclusively targets ssRNA

(194,195). In this system, different

subtypes have been identified as type VIA (having Cas13a)-VID

(having Cas13d), Cas13X and Cas13Y (196,197), among which Cas13a is the best

known so far. Innovative diagnostic methods for the identification

of certain miRNAs have been developed using this platform.

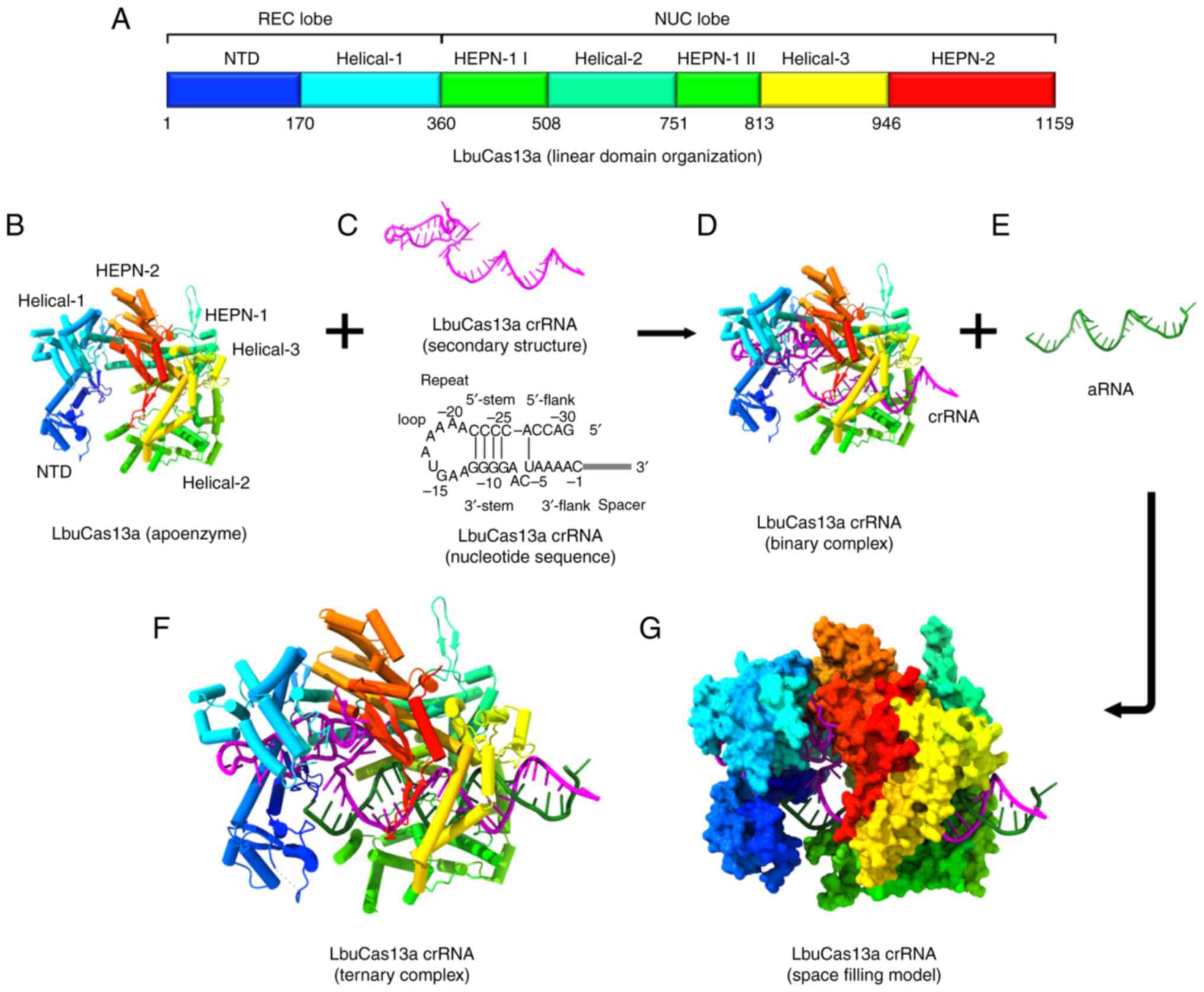

The V-shaped structure of the helix-1 domain is

formed by seven α-helices. The crRNA binding channel is formed by

the positively charged surface of the helix-1 domain facing the NTD

domain (204). The two

conserved higher eukaryotic and prokaryotic nucleotide-binding

(HEPN) domains (HEPN-1 and HEPN-2), a linker that joins the two

HEPN domains, and a helix-2 domain are all found in the NUC lobe

(202). The helix-1 and HEPN

domains are responsible for the two enzymatic functions of Cas13a.

The helix-2 domain further sub-divides the HEPN-1 domain into two

subdomains. Three α-helices make up the HEPN 1-II subdomain,

whereas four α-helices and a brief β-hairpin make up the HEPN-1 I

subdomain (Fig. 4B). Seven

α-helices plus a double-stranded β-sheet directly make up the HEPN2

domain structure (202).

Between the two HEPN-1 subdomains lies the helix-2 domain, which is

made up of eight bean-shaped α-helices (204). The Cas13a/crRNA complex targets

the matching RNA under the direction of crRNA, triggering the

protection of prokaryotes against RNA viruses (205,206) (Fig. 4F and G).

The structure of the crRNA is composed of a spacer

sequence [guide RNA (gRNA)] that mediates target recognition by

RNA-RNA hybridization and a repeat stem-loop region (referred to as

the 5′-handle) that prevents this region from being cleaved during

the cleavage of the target RNA by Cas13a (207) (Fig. 4C). The stem-loop is composed of

two single-stranded bases at the base, a nine-base loop,

neighboring motifs at both ends and a stem made up of five base

pairings. The repeat region of crRNA can twist slightly to generate

a helical shape in addition to a stem-loop secondary structure

(202). This structure is

primarily sustained by the creation of strong hydrogen bonds

between the HEPN2 domain and the backbone of the crRNA (204). It is possible to cause the

Cas13a protein to recognize the stem-loop structure of the crRNA in

a sequence-specific way by altering stem nucleotides, which is

necessary for its nuclease cleavage activity (204) (Fig. 4D).

Within the crRNA guide region, one to four

nucleotides oversee the 5′-end being attached to the void created

by the HEPN-1 and helix-2 domains, making a U-turn. The linker and

the groove created by the HEPN-2 domain bind the final three or

four nucleotides (16). To

identify the target RNA, the Cas13 protein buries a spacer of eight

or nine nucleotides at the 5′-end, while the middle region and

3′-end are exposed to the peripheral solvent (204). To determine the ideal gRNA,

researchers have created a computational model, and identified that

the properties of crRNA and the environment of the target RNA are

important constraints on the cleavage effectiveness of Cas protein

by assessing the activities of 24,460 gRNAs and looking for

mismatches between gRNAs and the target sequence (208).

Cas13 action does not require crRNA maturation; in

fact, pre-crRNA can detect target RNAs (also referred to as

activator RNA; Fig. 4E)

(209). The ribonucleoprotein

complex (RNP) undergoes a conformational change when crRNA binds to

a target RNA (Fig. 4F). A

catalytic site is formed in part by the close interaction of two

HEPN domains (201). The

binding of crRNA is anticipated to result in the cleavage of the

target RNA as well as other ssRNAs surrounding the RNP complex,

possibly including host RNA, because of the distance between the

catalytic site and the crRNA-RNA duplex. This activity of the

CRISPR/Cas13 system, known as collateral damage or collateral

cleavage, refers to the off-target cleavage of endogenous RNA

(205,210).

According to one study, sequence-specific

activation of non-specific RNA cleavage may help to protect the

nearby cells by causing cell dormancy or death, or it may improve

the prevention of phage replication by removing all RNA from a cell

in bulk (195). This ability

has been widely used in RNA knockout strategies, disease treatment,

interference with viral infection, screening of loss of function

mutants, molecular detection of biological agents and CRISPR-based

antimicrobials (211-213). Therefore, the CRISPR/Cas13

system can simultaneously cleave target RNA and non-target RNA

(206,214). Furthermore, in Cas13, the

mutation of arginine in the HEPN domain, which is responsible for

RNA cleavage, results in the formation of catalytically inactive

Cas13, known as dead Cas13 (dCas13). This form of Cas13 has been

used to increase the application of Cas13 in RNA research. Through

the binding of fluorescent proteins or enzymes, mutant dCas13

persistently attaches to target RNA and offers a platform for

detecting transcripts in living cells (20,215).

miRNA expression profiling is technically difficult

as mature miRNAs are small in size, highly similar and not too

abundant in bodily fluids (216). Different platforms have been

engineered that link CRISPR-based methods for miRNA detection with

the advantages of enzyme-assisted signal amplification and

enzyme-free amplification biosensing technologies (217). Electrochemical detection using

biosensors is a novel low-cost and sensitive diagnostic strategy

for the identification of nucleic acids. This approach offers

excellent sensitivity, accuracy and fewer diagnostic constraints as

this strategy is inexpensive, relying on effective sensors and a

straightforward, miniature readout (218).

RCA is a common isothermal enzymatic DNA

replication technique for creating DNA, RNA and protein sensors

(219,220). In an RCA reaction, a short DNA

or RNA strand is amplified to produce a long, single-stranded DNA

(ssDNA) or RNA using a circular DNA template by a specialized

isothermal strand displacement DNA or RNA polymerases (219,220). The RCA process results in a

concatemer that has >109 tandem DNA repeats that are

complementary to the circular DNA or RNA template (221). This visual detection platform

utilizing a CRISPR/Cas13 system, known as the visual Cas (vCas)

system, has been used for the specific and sensitive detection of

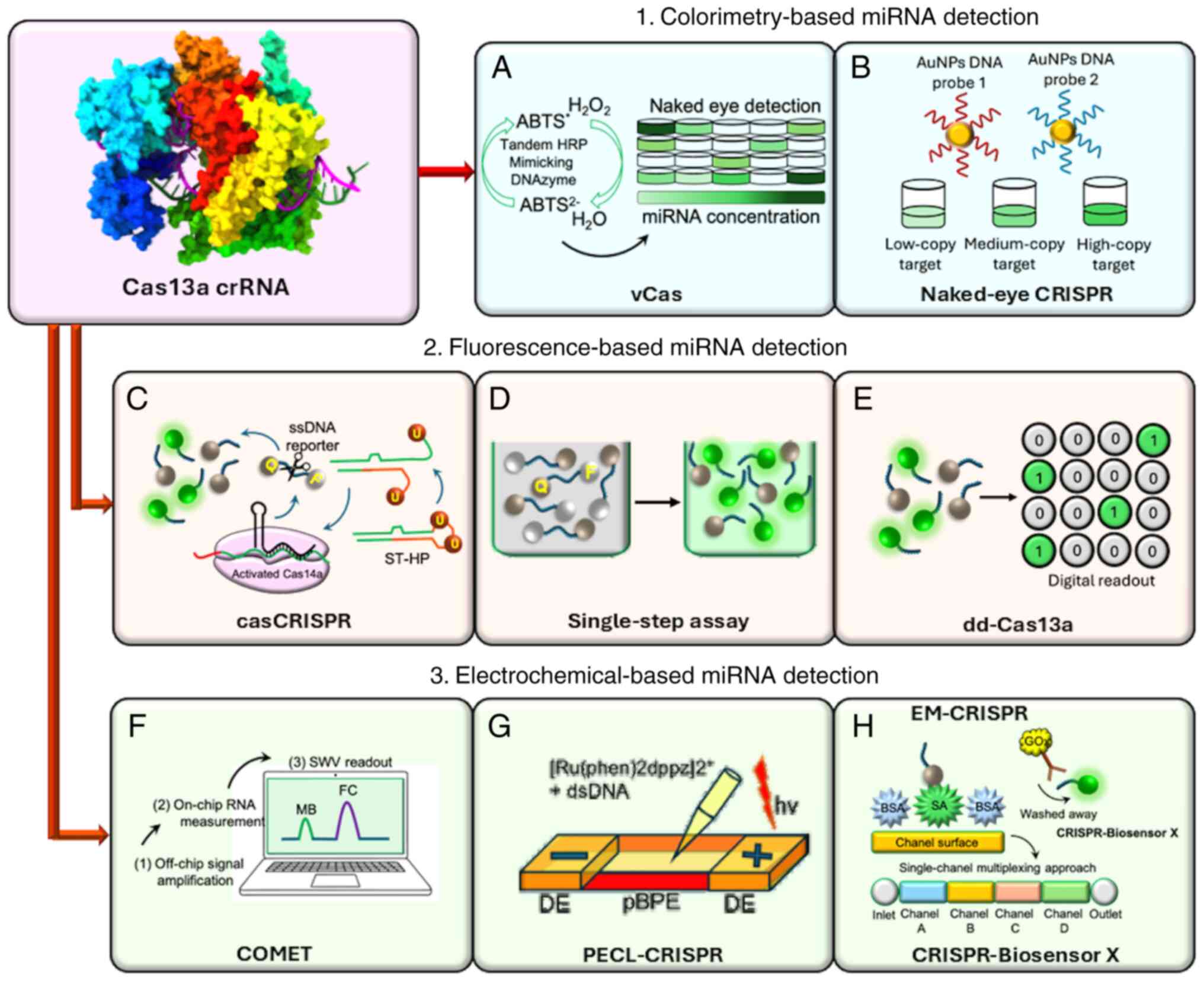

miRNA (222) (Fig. 5A).

Theoretically, when Cas13a/crRNA recognizes the

target miRNA, it collaterally cleaves the pre-primer that contains

uracil ribonucleotide (rU). DNA polymerase-mediated RCA can be

started using the leftover 5′-DNA fragment of the pre-primer.

Following its 3′-end, a T4 polynucleotide kinase restores the

aforementioned process to produce a lengthy G-rich repeat sequence

that can form a tandem G-quadruplex to function as a DNAzyme that

mimics HRP and T4 polynucleotide kinase catalyzes the oxidation of

the 2,2′-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonic acid)

diammonium salt (223)

(Fig. 5A). Consequently, within

10 min, the colorless mixture turns green, allowing the target

miRNA to be observed (223).

The results using this approach show that vCas can be used to

evaluate miRNAs in serum and cell extracts (222), and can offer a limit of

detection (LOD) of 1 fM for miR-10b, a type of miRNA highly

expressed in breast cancer cells (224,225). However, compared with one-step

Cas13a detection platforms, the LOD of this approach is four orders

of magnitude lower (222).

Colorimetric assays typically examine the color

shift within the test solution. Without the need for complex

equipment, miRNA detection can be performed quickly and easily with

the use of a colorimeter or the human eye (226). Once Cas12a/crRNA, Cas13a/crRNA

or Cas14/crRNA identify their target DNA or RNA, they exhibit a

transition to the active state, where their collateral cleavage

activity cleaves the ssRNA or ssDNA substrates (227,228). With the aid of CRISPR/Cas

recognition for miRNA sensing, researchers have created a DNA

probes and gold nanoparticles (AuNPs)-based platform.

Cas12a/crRNA's programmable recognition of DNA and Cas13a/crRNA's

programmable recognition of RNA initiates ssRNA or trans-ssDNA

cleavage of their corresponding complementary target (229). For the intended AuNPs-DNA probe

pair, target-induced trans-ssDNA or -ssRNA cleavage results in a

change in aggregation behavior, which allows direct visual

observation in an hour of various samples, including miRNAs

(229). For naked-eye gene

detection platforms, a universal linker ssRNA or ssDNA acts as a

trans-cleavage substrate for the CRISPR/Cas13a or CRISPR/Cas12a

systems. Furthermore, two universal AuNPs DNA probes have been

created to hybridize with either ssRNA or linker ssDNA (229).

Since trans-cleavage is not triggered in the

absence of a target (such as miRNA sequences), the linker ssDNA or

ssRNA stays intact during the reaction. An aggregated state is

created by hybridization-induced cross-linking of the AuNPs-DNA

probe pair (229). After the

trigger of trans-cleavage activity, the linker nucleotides are

broken down once the CRISPR/Cas systems identify their target

nucleotides. By identifying cross-linked and scattered AuNPs-DNA

probes (229), visual detection

can be approximated (Fig. 5B).

The sensitivity of miRNA detection is as low as 500 fM, which is on

par with or better than that of techniques based on dual-labeled

fluorescent ssRNA reporters (229). When comparing 1.0 nM target

miRNA-17 with miRNA-10b, miRNA-21 and miRNA-155 by colorimetry at

the same concentration, this approach demonstrated a strong level

of specificity (229).

Furthermore, family miRNA members with highly related sequences,

such as miRNA-17, miRNA-20a, miRNA-20b and miRNA-106a, can be

distinguished by single- or double-nucleotide variations at a

concentration of 1.0 nM using CRISPR/Cas-based colorimetric assays

(229).

A specific and sensitive biosensor, known as

casCRISPR has been developed for quick and precise miRNA detection,

even in cell extracts and serum samples, without the need for a

target amplification procedure such as PCR or recombinase

polymerase amplification (RPA) (230). By using this method, the

trans-cleavage activity of Cas13a/crRNA is triggered following

miRNA recognition. Such trans-ribonuclease activity has been

investigated using a hairpin-structured DNA oligonucleotide (stem

loop-hairpin or 'locked trigger') with an unpaired rU in the loop.

Accordingly, the phosphodiester bond adjacent to the rU of the

Cas14a/single guide RNA (sgRNA) 'locked-trigger' is broken

(Fig. 5C). Through strand

displacement, the latter causes the 'locked-trigger' to change from

a stable structure to a 5′-toehold duplex structure that can start

the interaction with Cas14a/sgRNA (230). The quencher, black hole

quencher 1 (BHQ1) and fluorophore [6-carboxyfluorescein (6-FAM)]

present on the ssDNA reporter are efficiently separated once the

'locked-trigger' is cleaved, resulting in Cas14a-based

trans-cleavage and the production of fluorescence signals (230) (Fig. 5C). In casCRISPR, the

trans-cleavage activity of Cas13a and Cas14a enables the detection

of miR-17 with a LOD of 1.33 fM, even by a difference of one

nucleotide (single base specificity), which is ~1,000 times lower

than that of direct Cas13a-based miRNA detection (199). As a promising tool for miRNA

diagnostics, casCRISPR may offer greater miRNA detection

specificity without amplification of the target as required for

RT-qPCR because of the Cas13a/crRNA high-fidelity recognition

capacity (230). Researchers

have engineered casCRISPR v2, a second version, by adding Cas13a

and Cas12a coupled with casCRISPR, and have compared this with

ordinary casCRISPR (version 1). This platform exhibited an advanced

performance, because Cas12a also functions as a ssDNA-activated

DNase (230,231). The fluorescence intensity

curves showed that casCRISPR v1 could detect miR-17 at as low as

6.25 fM, whereas casCRISPR v2 could detect miR-17 at as low as 100

fM. However, Cas13a-Cas14a (casCRISPR v1) could reach a lower

detection limit and a greater signal to background ratio than

Cas13a-Cas12a, which may be explained by the fact that Cas14a has

an improved cleavage efficiency compared with Cas12a when ssDNA is

utilized as the activator (230).

A novel approach known as dd-Cas13a increases the

concentration of local molecules for an effective reaction or

detection (234). Researchers

have adopted a droplet microfluidic technology to increase the

local concentration of the RNA reporter and target sequence for the

Cas13a system in cell-sized volumes (235,236). Thousands of picolitre-sized

droplet reactors are filled with an oil-emulsified combination of

target RNAs and Cas13a. Such droplets can be illuminated by the

cumulative fluorescence signal from the collateral cleavage of a

single RNA target-activated Cas13a (235,236) (Fig. 5E). Under these circumstances, a

single-target RNA can cause the cleavage of >100 quenched

fluorescent RNA reporters following recognition by a crRNA,

producing a fluorescence-positive droplet. Therefore, dd-Cas13a

eliminates the necessity for reverse transcription and

amplification, and enables absolute digital quantification of

single unlabeled RNA molecules (235,236). The utility of the dd-Cas13

assay was assessed by measuring miRNA-17 expression in several cell

lines, such as human glioma cells, normal human breast cells and

adenocarcinoma cells, and 100% results that corresponded with

RT-qPCR data were obtained (235).

The CRISPR/Cas13a platform and a CHDC can be

integrated on an electrochemical biosensor, known as COMET. This

approach consists of a two-stage signal amplification system for

high-sensitivity estimation of six RNAs related to non-small cell

lung cancer (NSCLC), including miR-17, miR-19b, thyroid

transcription factor-1 RNA, miR-155, EGFR mRNA and miR-210. All

components are carefully combined to enable dual signal

amplification for the CRISPR/Cas13a platform and catalyzed hairpin

DNA circuit (Cas-CHDC)-powered RNA detection (237).

To achieve quick RNA detection on a small

point-of-care (POC) testing device, scientists have incorporated

chip-based Cas-CHDC amplification into an electrochemical

biosensing technology (237)

(Fig. 5F). The COMET chip could

differentiate between miR-20a and miR-20b (two-base mismatches) and

between miR-17 and miR-106a (1-base mismatch) (237). Furthermore, a 1:1,000 M mixture

of miR-17 with miR-155 and thyroid transcription factor-1 mRNA has

been used to assess the capacity of the COMET chip to identify

lower expression target RNAs in special samples such as benign lung

disease and NSCLC samples (237).

Because non-target RNAs are highly expressed in the

circulation of patients, scientists have identified that the COMET

chip could detect miR-17 at zeptomolar (10−21 M)

concentrations and as low as 0.1% of background RNA mixture. This

is crucial for future clinical use, and the chip and reagents can

be purchased for as little as USD 0.27 per test (237).

Based on the ECL approach and employing the

trans-cleavage activity of CRISPR/Cas13a, scientists have

engineered a sophisticated platform known as PECL-CRISPR, which

mediates the exponential amplification of the ultrasensitive

detection of miRNAs that differ even by a single-base (232).

Quantitative miRNA detection is made possible by

the ECL signal on a bipolar electrode (BPE), which directly

reflects the oxidation reaction of the ruthenium (II) polypyridyl

complex [Ru(phen)2dppz]2+ and DNA at the BPE anode, and

is directly related to the miRNA concentration (232) (Fig. 5G). By identifying miR-17 from

various human cancer cells, the application of PECL-CRISPR has been

examined, proving that the platform has great potential for miRNA

diagnosis (232).

By logically designing the crRNA, the platform

exhibits the ability to differentiate between highly homologous

members of the miR-17 and let-7 families by introducing a mismatch

at the precise location of the crRNA, independent of the single

distinct base locations at the 5′ or 3′ end of the target (233). The LOD of this platform for

miR-17 was 1.0×10−15 M, which is approximately three

orders of magnitude lower than that of the direct detection of

miR-17 (LOD, 1.0×10−12 M) using LbuCas13a (233).

For on-site detection of miRNAs, a

CRISPR/Cas13-based biosensor has been created as a user-friendly

and cheaper electrochemical microfluidic platform

(EM-CRISPR/Cas13a), which substitutes a Cas13a-driven signal

amplification for synthetic nucleic acid amplification steps

(238). In this assay, a

streptavidin is applied to the chip inlet to functionalize the

immobilized surface area of the biosensor for the

CRISPR/Cas13a-powered miRNA detection. All unbound biomolecules are

eliminated by vacuuming the channel inlet (238). To activate Cas13a and perform

the collateral cleavage of the reporter RNA (reRNA), the samples

(biotin and 6-FAM-tagged reRNA), and the other sample (containing

the target miRNA and the Cas13a effector with its target-specific

crRNA) are mixed separately (238) (Fig. 5H).

An enzymatic readout of the assay is made possible

by the addition of anti-fluorescein antibodies bonded with glucose

oxidase (GOx), which bind only to the uncleaved reRNAs (Fig. 5H). Since GOx catalyzes its

substrate to produce H2O2, which is

amperometrically measured in the electrochemical cell, a glucose

solution is used in this assay for the readout (238). Without performing nucleic acid

amplification, researchers have used this new combination to detect

the miRNA levels of the putative brain tumor markers miR-19b and

miR-20a in serum samples. With a setup time of <4 h and a

readout time of 9 min, the EM-CRISPR/Cas13a biosensor achieved a

detection limit of 10 pM with a measuring volume of <0.6 liters.

Additionally, this biosensor platform was able to identify miR-19b

in serum samples of children with brain cancer, proving that this

electrochemical CRISPR-powered system is a low-cost, readily

scalable and target amplification-free molecular approach for

miRNA-based diagnostics (238).

The development of diagnostic tools and techniques

for multiplexing approaches is based on analyzing the abundance of

a number of specific components in individual samples from a

patient. However, the variety of Cas protein types and the

potential for cross-reactions between distinct Cas13a proteins may

restrict the use of Cas13a (239).

This might be resolved using a multichannel

microfluidic chip technique.

Researchers have developed various multiform

versions of electrochemical microfluidic biosensors by segmenting

the channels into subsections, using the same principle as the

EM-CRISPR/Cas13a system (Fig.

5H). This resulted in four unique chip designs for the

simultaneous quantification of a maximum of eight miRNAs using the

innovative system called CRISPR-Biosensor X. Without altering the

sensor or measurement configuration, this system can work on a

single clinical sample with a single effector protein (239).

Because of their high sensitivity, selectivity and

low instrument costs, electrochemical biosensors are emerging as a

potent detection technique platform (240). Using the CRISPR/Cas13a platform

in conjunction with the catalytic hairpin assembly (CHA) process,

an ultrasensitive electrochemical biosensing platform has been

designed for miRNA-21 detection (241). CHA is a high-efficiency,

isothermal, enzyme-free amplification technique that may be used in

a variety of analytical formats, such as electrophoretic (242), colorimetric (243), fluorescence (231), surface plasmon resonance

(244) and electrochemical

approaches (245).

This electrochemical biosensor exhibited a strong

biosensing activity from 10 fM to 1.0 nM with an LOD of 2.6 fM

using the CRISPR/Cas13a-mediated cascade signal amplification

approach (241). The use of the

biosensing platform for miRNA-21 detection was assessed. A clinical

sample (human serum; diluted ten times), was used to test the

analytical reliability before being tested for various

concentrations of miRNA-21 (10 fM to 1.0 nM). The electrochemical

recoveries were ~98.2%, demonstrating that the CRISPR/CHDC assay

can be used to identify miRNA-21 in biological materials (241).

The off-target consequences of the CRISPR/Cas13a

system are minimal. One to two mismatches in the core of a gRNA

diminish or eliminate its activity, enabling a mismatch control for

each targeting gRNA (20,246).

In this context, the specific high-sensitivity enzymatic reporter

unlocking (SHERLOCK) detection system, employs the CRISPR/Cas13a

system as a quick DNA or RNA detection technique with aM

(10−18 M) sensitivity and single-base mismatch

specificity (247). This

approach uses isothermal RPA, transcription and detection by Cas13

platforms (247). The signal

can be recorded on a colorimetric lateral-flow strip or can be

observed by fluorescence signal readout to facilitate the rapid

identification of most types of suitable Cas13 RNA target. SHERLOCK

enables single base-pair mismatch specificity, quick (setup time,

<15 min) and accurate nucleic acid detection at concentrations

as low as ~2 aM (248).

The use of innovative methods for miRNA detection

is revealing novel information regarding the processing and

function of miRNAs, as well as providing a basic understanding of

how important miRNA factors and substrates function. There are next

steps to follow for most of the experimental procedures that have

been described. For instance, structural investigations of miRNA

biogenesis factors have only evaluated a small number of miRNAs.

Since the biogenesis efficiency of endogenous miRNAs varies

greatly, it will be instructive for both microprocessor and Dicer

substrates to include a variety of miRNAs in future investigations.

This could provide information regarding microprocessor cofactors

that serve a role in the synthesis of clustered and/or inefficient

miRNAs.

Direct viewing of dynamic miRNA processing and

regulatory complexes is made possible only by single-molecule

imaging. In vivo experiments have largely focused on AGO and

not enough research has been performed on other miRNA biogenesis

factors. In vitro investigations of microprocessors have

been lacking. The subcellular environments of microprocessors and

Dicers are functionally significant and require additional

investigation in the future.

Furthermore, the implications of miRNA biology,

such as whether organismal phenotypes are actually mediated by the

regulation of specific miRNA targets, must not be overlooked. Most

of the research on miRNA-target biology is still correlative, and

just because numerous derepressed targets are found when a miRNA is

lost, this does not always suggest that they all serve a functional

role in miRNA phenotypes.

CRISPR mutagenesis has demonstrated the potent

phenotypic influence of target mRNAs and validated the growing

number of target-directed miRNA degradation target sites that

regulate miRNA abundance. To completely comprehend the role of

miRNA in development and disease, it is necessary to establish

clear links between target site-mediated gene regulation and in

vivo phenotypes.

Prior to the full clinical use of CRISPR/Cas13

technologies, a few issues need to be resolved, including: i) As

the fidelity of the CRISPR/Cas13 platform is directly linked to the

tolerance of RNA mismatches, a wider range of mismatch tolerance by

Cas13 effectors may encourage off-target activity (22); ii) it may be challenging to meet

the specific protospacer flanking sequence requirement for Cas13

effectors; iii) RNA recognition of small RNA target sequences

(<22 nt) because of the requirement that crRNAs be long enough

for binding (205); and iv) RNA

segments derived from effective ssRNA cleavage mediated by Cas13

may be toxic in eukaryotic cells (206,249).

miRNAs serve a role in the regulation of gene

expression. It is now well documented that dysregulated miRNA

expression is a fundamental cause of different diseases. including

cancer. The dysregulation of miRNA expression can occur via the

amplification or deletion of their genes, aberrant transcriptional

control, dysregulated epigenetic modifications and flaws in their

biogenesis machinery. Aberrant miRNA expression leads a cell to

achieve the ability to maintain the proliferative signals, avoid

growth suppressors, initiate invasion and metastasis, trigger

angiogenesis, and withstand cell death, and all these changes lead

to the transformation to cancerous cells. The exploration of

programmable RNA-targeting regulators makes it easier to detect

endogenous RNA and track various mRNA species in real time within

cells. It is important to develop methods that could identify and

target miRNA sequences in a broad manner, especially those with low

expression levels. CRISPR/Cas13-based miRNA detection strategies

have proven to be a versatile platform, as this approach of

miRNA-detection is beneficial in all aspects compared with other

currently used methods, which are expensive, and require special

expertise and instruments. CRISPR/Cas13-based miRNA detection

systems hold promise for the future with the potential to

revolutionize diagnostic and personalized medicine.

CRISPR/Cas13-based miRNA detection with high sensitivity and

specificity can enable early and accurate detection of diseases

such as cancer, even when miRNA levels are low. Future developments

may allow for precise differentiation between miRNA isoforms. This

can provide insights into disease mechanisms and guide targeted

therapies. CRISPR/Cas13-based assays can be designed for rapid, POC

diagnostics, eliminating the need for complex laboratory setups.

Overall, the future of CRISPR/Cas13-based miRNA detection is

bright. With continued research and development, this technology

has the potential to transform the field of diagnostics, enabling

early disease detection, personalized medicine and potentially even

miRNA-based therapies.

Not applicable.

AAA and AAK conceived the study. AAA, AMA and AAK

wrote the original draft. AAA, AMA, AA, BFA, AHR and AAK reviewed

and edited the manuscript. Data authentication is not applicable.

All authors have read and approved the final version of the

manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

The researchers would like to thank the Deanship of

Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at Qassim University for

financial support (QU-APC-2025).

The present study was supported by the Deanship of Graduate

Studies and Scientific Research at Qassim University

(QU-APC-2025).

|

1

|

Shenoy A and Blelloch RH: Regulation of

microRNA function in somatic stem cell proliferation and

differentiation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 15:565–576. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Jonas S and Izaurralde E: Towards a

molecular understanding of microRNA-mediated gene silencing. Nat

Rev Genet. 16:421–433. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Swarts DC, Makarova K, Wang Y, Nakanishi

K, Ketting RF, Koonin EV, Patel DJ and Van Der Oost J: The

evolutionary journey of argonaute proteins. Nat Struct Mol Biol.

21:743–753. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Friedman RC, Farh KK, Burge CB and Bartel

DP: Most mammalian mRNAs are conserved targets of microRNAs. Genome

Res. 19:92–105. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

5

|

Kozomara A and Griffiths-Jones S: miRBase:

Annotating high confidence microRNAs using deep sequencing data.

Nucleic Acids Res. 42:D68–D73. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

6

|

Otmani K, Rouas R and Lewalle P: OncomiRs

as noncoding RNAs having functions in cancer: Their role in immune

suppression and clinical implications. Front Immunol.

13:9139512022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Ali Syeda Z, Langden SSS, Munkhzul C, Lee

M and Song SJ: Regulatory mechanism of MicroRNA expression in

cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 21:17232020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Otmani K and Lewalle P: Tumor suppressor

miRNA in cancer cells and the tumor microenvironment: Mechanism of

deregulation and clinical implications. Front Oncol. 11:7087652021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Yousefnia S and Negahdary M: Role of

miRNAs in cancer: Oncogenic and tumor suppressor miRNAs, Their

regulation and therapeutic applications. Interdisciplinary Cancer

Research. Springer; Cham: pp. 1–27. 2024

|

|

10

|

Siddika T and Heinemann IU: Bringing

MicroRNAs to light: Methods for MicroRNA quantification and

visualization in live cells. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 8:6195832021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Mockly S and Seitz H: Inconsistencies and

limitations of current MicroRNA target identification methods.

Methods Mol Biol. 1970:291–314. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Koshiol J, Wang E, Zhao Y, Marincola F and

Landi MT: Strengths and limitations of laboratory procedures for

microRNA detection. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 19:907–911.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Allemailem KS, Alsahli MA, Almatroudi A,

Alrumaihi F, Alkhaleefah FK, Rahmani AH and Khan AA: Current

updates of CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing and targeting within

tumor cells: An innovative strategy of cancer management. Cancer

Commun (Lond). 42:1257–1287. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Allemailem KS, Almatroudi A, Alrumaihi F,

Alradhi AE, Theyab A, Algahtani M, Alhawas MO, Dobie G, Moawad AA,

Rahmani AH and Khan AA: Current updates of CRISPR/Cas system and

anti-CRISPR proteins: Innovative applications to improve the genome

editing strategies. Int J Nanomedicine. 19:10185–10212. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Liu Y, Chen Y, Dang L, Liu Y, Huang S, Wu

S, Ma P, Jiang H, Li Y, Pan Y, et al: EasyCatch, a convenient,

sensitive and specific CRISPR detection system for cancer gene

mutations. Mol Cancer. 20:1572021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Huang Z, Fang J, Zhou M, Gong Z and Xiang

T: CRISPR-Cas13: A new technology for the rapid detection of

pathogenic microorganisms. Front Microbiol. 13:10113992022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Allemailem KS, Alsahli MA, Almatroudi A,

Alrumaihi F, Al Abdulmonem W, Moawad AA, Alwanian WM, Almansour NM,

Rahmani AH and Khan AA: Innovative strategies of reprogramming

immune system cells by targeting CRISPR/Cas9-based genome-editing

tools: A new era of cancer management. Int J Nanomedicine.

18:5531–5559. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Koonin EV and Makarova KS: CRISPR-Cas: An

adaptive immunity system in prokaryotes. F1000 Biol Rep. 1:952009.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Allemailem KS, Almatroudi A, Rahmani AH,

Alrumaihi F, Alradhi AE, Alsubaiyel AM, Algahtani M, Almousa RM,

Mahzari A, Sindi AA, et al: Recent updates of the CRISPR/Cas9

genome editing system: Novel approaches to regulate its

spatiotemporal control by genetic and physicochemical strategies.

Int J Nanomedicine. 19:5335–5363. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Abudayyeh OO, Gootenberg JS,

Essletzbichler P, Han S, Joung J, Belanto JJ, Verdine V, Cox DB,

Kellner MJ, Regev A, et al: RNA targeting with CRISPR-Cas13.

Nature. 550:280–284. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

O'Connell MR: Molecular mechanisms of RNA

targeting by Cas13-containing type VI CRISPR-Cas systems. J Mol

Biol. 431:66–87. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Ali Z, Mahas A and Mahfouz M: CRISPR/Cas13

as a tool for RNA interference. Trends Plant Sci. 23:374–378. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Yang LZ, Wang Y, Li SQ, Yao RW, Luan PF,

Wu H, Carmichael GG and Chen LL: Dynamic imaging of RNA in living

cells by CRISPR-Cas13 systems. Mol Cell. 76:981–997.e7. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Granados-Riveron JT and Aquino-Jarquin G:

CRISPR-Cas13 precision transcriptome engineering in cancer. Cancer

Res. 78:4107–4113. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Li Y, Wang Q and Wang Y: Direct and

accurate miRNA detection based on CRISPR/Cas13a-triggered

exonuclease-iii-assisted colorimetric assay. J Anal Sci Technol.

15:212024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Kim JJ, Hong JS, Kim H, Choi M, Winter U,

Lee H and Im H: CRISPR/Cas13a-assisted amplification-free miRNA

biosensor via dark-field imaging and magnetic gold nanoparticles.

Sens Diagn. 3:1310–1318. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Wang M, Cai S, Wu Y, Li Q, Wang X, Zhang Y

and Zhou N: A lateral flow assay for miRNA-21 based on

CRISPR/Cas13a and MnO2 nanosheets-mediated recognition

and signal amplification. Anal Bioanal Chem. 416:3401–3413. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Leitão AL and Enguita FJ: A structural

view of miRNA biogenesis and function. Noncoding RNA.

8:102022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Shang R, Lee S, Senavirathne G and Lai EC:

microRNAs in action: Biogenesis, function and regulation. Nat Rev

Genet. 24:816–833. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Nishikura K: A-to-I editing of coding and

non-coding RNAs by ADARs. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 17:83–96. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

31

|

Denli AM, Tops BBJ, Plasterk RHA, Ketting

RF and Hannon GJ: Processing of primary microRNAs by the

Microprocessor complex. Nature. 432:231–235. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Gregory RI, Yan KP, Amuthan G, Chendrimada

T, Doratotaj B, Cooch N and Shiekhattar R: The microprocessor

complex mediates the genesis of microRNAs. Nature. 432:235–240.

2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Lee Y, Ahn C, Han J, Choi H, Kim J, Yim J,

Lee J, Provost P, Rådmark O, Kim S and Kim VN: The nuclear RNase

III Drosha initiates microRNA processing. Nature. 425:415–419.

2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Nguyen TA, Jo MH, Choi YG, Park J, Kwon

SC, Hohng S, Kim VN and Woo JS: Functional anatomy of the human

microprocessor. Cell. 161:1374–1387. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Kwon SC, Nguyen TA, Choi YG, Jo MH, Hohng

S, Kim VN and Woo JS: Structure of human DROSHA. Cell. 164:81–90.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Kim B, Jeong K and Kim VN: Genome-wide

mapping of DROSHA cleavage sites on primary microRNAs and

noncanonical substrates. Mol Cell. 66:258–269.e5. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Neilsen CT, Goodall GJ and Bracken CP:

IsomiRs-the overlooked repertoire in the dynamic microRNAome.

Trends Genet. 28:544–549. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Lau NC, Lim LP, Weinstein EG and Bartel

DP: An abundant class of tiny RNAs with probable regulatory roles

in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 294:858–862. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Lee RC and Ambros V: An extensive class of

small RNAs in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 294:862–864. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Nicholson AW: Ribonuclease III mechanisms

of double-stranded RNA cleavage. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA.

5:31–48. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Okada C, Yamashita E, Lee SJ, Shibata S,

Katahira J, Nakagawa A, Yoneda Y and Tsukihara T: A high-resolution

structure of the pre-microRNA nuclear export machinery. Science.